Aligning Supply and Demand: The Evolution of Community Public Sports Facilities in Shanghai, China

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- Spatio-temporal evolution characteristics. During the 15-year urban expansion cycle, has the supply center of Shanghai’s sports facilities effectively responded to the changes in the population center? Is there a significant spatio-temporal lag?

- (2)

- Measurement of supply–demand matching. How has the degree of supply–demand matching in different administrative districts evolved? Are there persistent “supply depressions”?

- (3)

- Identification of driving mechanisms. Which key factors dominate the spatial allocation of facilities? Is there an enhanced interaction effect among these factors?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

- (1)

- Representativeness. Shanghai is currently in a critical period of transformation from “incremental expansion” to “stock renewal”. The characteristics of supply–demand mismatch during this stage have early-warning significance for other emerging megacities that are about to enter the mature stage.

- (2)

- Data Availability. As a pioneer city in digital governance in China, Shanghai has relatively complete historical statistical data and geographic information records, enabling a longitudinal panel analysis spanning 15 years (2010–2024), which is relatively rare in urban studies in developing countries.

- (3)

- Spatial Heterogeneity. Shanghai encompasses a complete gradient from high-density central urban areas to rapidly urbanizing suburbs and then to rural areas. Such rich internal differences allow us to simulate the supply–demand relationships at different development stages within a single city.

2.2. Theoretical Framework and Research Hypotheses

2.2.1. Mechanism of Supply–Demand Equilibrium and Spatial Mismatch

- (1)

- Population decentralization. Driven by the high cost of living in central urban areas, the population migrates rapidly to the suburbs [18].

- (2)

- Fixity of facilities. As heavy-asset investments, sport facilities involve long cycles from planning and site selection to completion and are constrained by path dependency in central urban areas [19].

2.2.2. Research Hypotheses

- (1)

- What is the spatio-temporal evolution trajectory of supply and demand?

- (2)

- How can the degree of this mismatch be quantified?

- (3)

- Which socio-economic factors drive this mismatch?

2.3. Research Data

- (1)

- Longitudinal stability of data. From 2010 to 2024, Shanghai witnessed frequent adjustments to grassroots administrative divisions (such as the merger of Zhabei District and Jing’an District, and the transformation of multiple towns into sub-districts), resulting in severe spatial mismatch and fragmentation problems in street-level statistical data. In contrast, the boundaries of the 16 municipal districts are relatively stable, making them the only feasible scale for long-term panel analysis.

- (2)

- Subjectivity of policy implementation. In China’s urban governance system, district-level governments are the core responsible entities for implementing planning and guaranteeing the financing of public sport facilities. Analyzing the supply–demand match at the district level allows for a more direct evaluation of the public service supply performance of each district government.

2.4. Supply–Demand Spatial Matching Measurement Method

2.4.1. Geographic Concentration Index

2.4.2. Inconsistency Index

2.4.3. Facility–Population Growth Elasticity

2.4.4. Spatial Gravity Center Method

2.5. Impact Factor Evaluation Method

2.5.1. Indicator System

2.5.2. Geodetector

2.5.3. Two-Way Fixed Effects Panel Regression Model

3. Result Analysis

3.1. Spatial Matching Characteristics Analysis

3.1.1. Geographic Concentration Index Analysis

3.1.2. Inconsistency Analysis

3.1.3. Growth Elasticity Analysis

3.1.4. Spatial Gravity Center Evolution

3.2. Influencing Factors

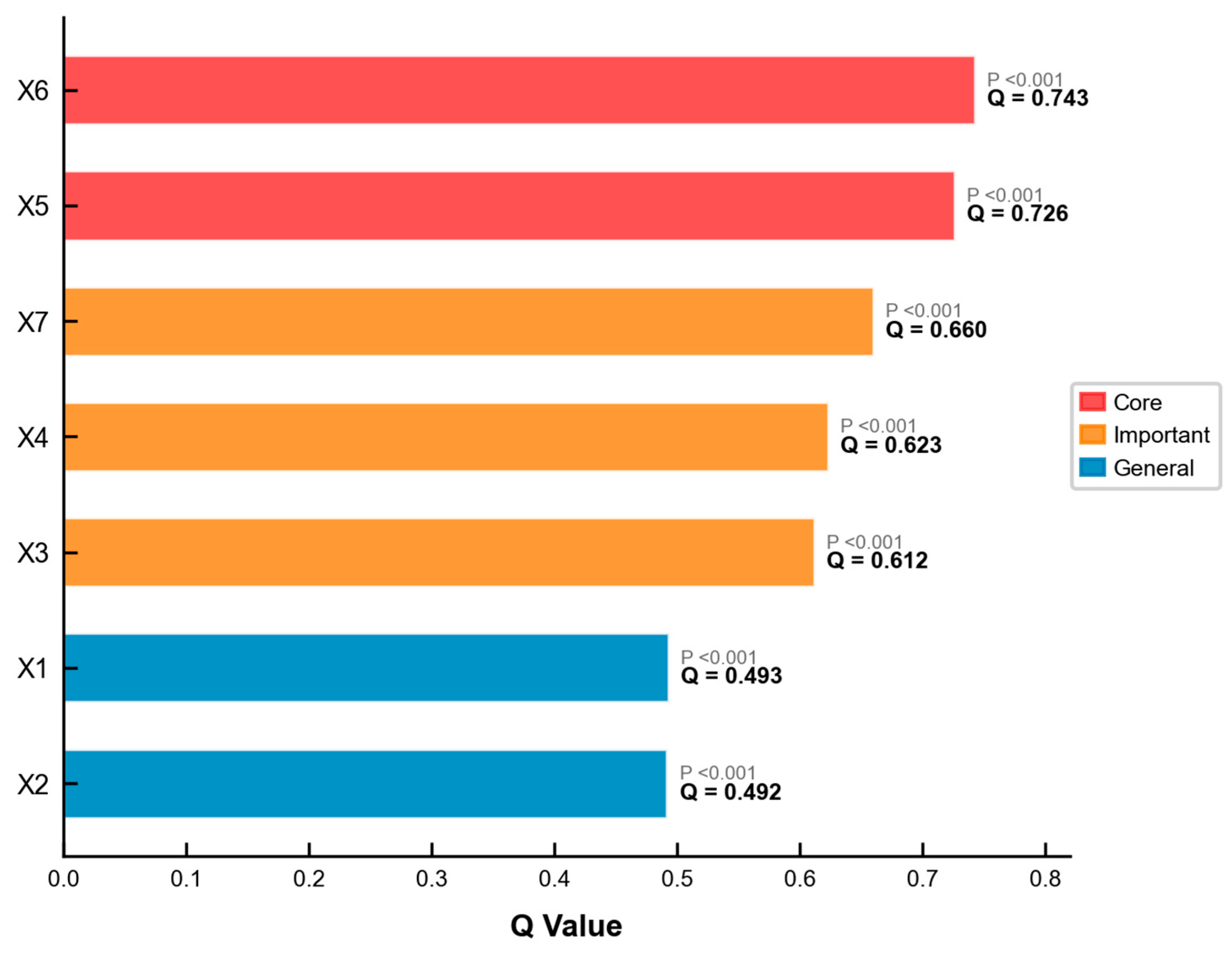

3.2.1. Single Factor Detection Analysis

- (1)

- Analysis of core influencing factors

- (2)

- Analysis of important influencing factors

- (3)

- Analysis of general influencing factors

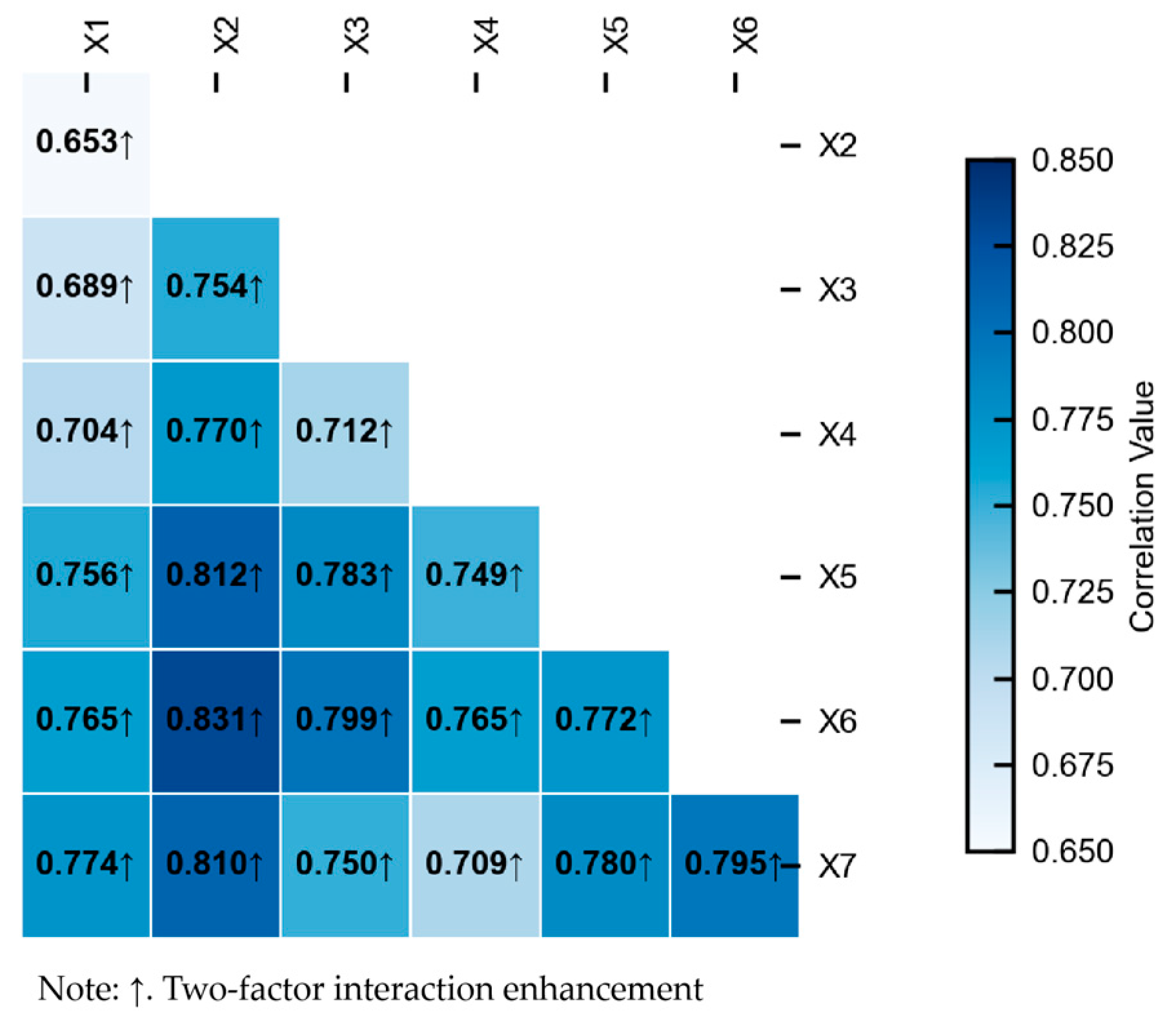

3.2.2. Bivariate Factor Interaction Detection Analysis

3.2.3. Driving Mechanism Analysis Based on Panel Regression

- (1)

- Corrective effect of economic input

- (2)

- Crowding-out effect of land rent

- (3)

- Pressure effect of population activity

- (4)

- Auxiliary role of transportation and construction

4. Discussion

4.1. Mechanisms: Institutional Inertia and Rent Gap Dynamics

- (1)

- Fiscal fragmentation caused by administrative divisions. Different from the single-center urban model, the supply of public goods in Shanghai is highly dependent on the fiscal capacity of each district-level government. Although the population growth in the central districts has stagnated, they maintain a high level of facility services relying on mature financial foundations and stock space renewal, while suburban governments, bearing huge population inflow pressure, still mainly allocate financial resources to infrastructure construction, resulting in a significant “time-lag effect” in the construction of soft public services.

- (2)

- Crowding-out effect of the rent gap. Regression analysis shows that housing prices have a complex impact on facility supply. Against the background of high land commercialization, sport facilities, as low-yield public goods, are often at a disadvantage in competition with commercial or residential land, especially in sub-center areas, where land prices are soaring. This market-driven spatial exclusion is a common challenge faced by global high-density cities in the process of renewal.

4.2. Paradigm Shift: From “Static Blueprint” to “Dynamic Adaptation”

- (1)

- Reserving flexible zoning. In suburbs with obvious population inflow trends, planning departments should not only focus on the current permanent population but should predict based on the growth rate of historical panel data (Growth Elasticity) and reserve “White Sites” in advance for future public facility construction to prevent land from being completely locked by high-density housing.

- (2)

- Composite utilization of stock space. In the central urban area, in view of the depletion of new land, we should learn from the experience of Tokyo, New York, and use vertical zoning or time-sharing strategies to embed sports facilities on the roofs or idle spaces of schools and commercial complexes to cope with the high-density “man-land conflict”.

4.3. Governance Implications: Data-Driven Precision Allocation

4.4. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Giles-Corti, B.; Vernez-Moudon, A.; Reis, R.; Turrell, G.; Dannenberg, A.L.; Badland, H.; Foster, S.; Lowe, M.; Sallis, J.F.; Stevenson, M.; et al. City planning and population health: A global challenge. Lancet 2016, 388, 2912–2924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sallis, J.F.; Bull, F.; Burdett, R.; Frank, L.D.; Griffiths, P.; Giles-Corti, B.; Stevenson, M. Use of science to guide city planning policy and practice: How to achieve healthy and sustainable future cities. Lancet 2016, 388, 2936–2947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieuwenhuijsen, M.J. Urban and transport planning pathways to carbon neutral, liveable and healthy cities; A review of the current evidence. Environ. Int. 2020, 140, 105661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, L.; Liu, Y.; Liu, X. Measuring spatial disparity in accessibility with a multi-mode method based on park green spaces classification in Wuhan, China. Appl. Geogr. 2018, 94, 251–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigolon, A. A complex landscape of inequity in access to urban parks: A literature review. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2016, 153, 160–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, W.; Wang, F. Measures of spatial accessibility to health care in a GIS environment: Synthesis and a case study in the Chicago region. Environ. Plann. B Plann. Des. 2003, 30, 865–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Xie, Y.; Sun, S.; Hu, L. Evaluation of Park Accessibility Based on Improved Gaussian Two-Step Floating Catchment Area Method: A Case Study of Xi’an City. Buildings 2022, 12, 871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iraegui, E.; Augusto, G.; Cabral, P. Assessing Equity in the Accessibility to Urban Green Spaces According to Different Functional Levels. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2020, 9, 308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rzeszutek, M.; Bogacki, M.; Bździuch, P.; Szulecka, A. Improvement assessment of the OSPM model performance by considering the secondary road dust emissions. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2019, 68, 137–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campani, G. Indigenous Education in Brazil—The Case of the Bare People in Nova Esperança: Transition to Work and Sustainability. Soc. Sci. 2024, 13, 481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Chen, R.; Wang, Y. Tendency of land reclamation in coastal areas of Shanghai from 1998 to 2015. Land Use Policy 2020, 91, 104370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Li, J.; Cheng, J. Spatial Disparity of Sports Infrastructure Development and Urbanization Determinants in China: Evidence from the Sixth National Sports Venues Census. Appl. Spat. Anal. 2024, 17, 573–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortés, Y.; Iturra, V. Market versus public provision of local goods: An analysis of amenity capitalization within the Metropolitan Region of Santiago de Chile. Cities 2019, 89, 92–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, L.; Li, Y.; Yan, Y.; Wang, B. Measuring urban sprawl and exploring the role planning plays: A Shanghai case study. Land Use Policy 2017, 67, 426–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Liu, W.; Lu, D. Challenges and the way forward in China’s new-type urbanization. Land Use Policy 2016, 55, 334–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Xia, M.; Yang, S.; Zhu, J. Promotion Incentive, Population Mobility and Public Service Expenditure. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, G.C.S.; Yi, F. Urbanization of capital or capitalization on Urban Land? Land Development and Local Public Finance in Urbanizing China. Urban Geogr. 2011, 32, 50–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aina, Y.A.; Wafer, A.; Ahmed, F.; Alshuwaikhat, H.M. Top-down sustainable urban development? Urban governance transformation in Saudi Arabia. Cities 2019, 90, 272–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Wang, Z.; Li, Z.; Tang, Z. An assessment of urban park access in Shanghai—Implications for the social equity in urban China. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2017, 157, 383–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Yao, J.; Sila-Nowicka, K.; Song, C. Geographic concentration of industries in Jiangsu, China: A spatial point pattern analysis using micro-geographic data. Ann. Reg. Sci. 2021, 66, 439–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, Y.; Tan, K.H. Inconsistency indices in pairwise comparisons: An improvement of the Consistency Index. Ann. Oper. Res. 2023, 326, 809–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, H.; Abade, E.; Maia, F.; Costa, J.A.; Marcelino, R. Acute and chronic effects of elastic band resistance training on athletes’ physical performance: A systematic review. Sport Sci. Health 2025, 21, 69–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, X.; Wang, J.; Zhong, Z. Spatial evolution characteristics and influencing factors of sports brand resources in Chinese urban agglomerations. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 22138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hei, Y.; Sui, Y.; Gao, W.; Zhao, M.; Hu, M.; Gao, M. Geodetector-Based Analysis of Spatiotemporal Distribution Characteristics and Influencing Mechanisms for Rural Homestays in Beijing. Land 2025, 14, 997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, D. Explore Associations between Subjective Well-Being and Eco-Logical Footprints with Fixed Effects Panel Regressions. Land 2021, 10, 931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redivo, E.; Viroli, C.; Farcomeni, A. Quantile-distribution functions and their use for classification, with application to naïve Bayes classifiers. Stat. Comput. 2023, 33, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X. Analysis of Two Influential Factors: Interaction and Mediation Modeling. In Quantitative Epidemiology; Emerging Topics in Statistics and Biostatistics; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 235–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Data Type | Data Source | URL |

|---|---|---|

| Community Public Sports Facilities | Official Website of Shanghai Sports Bureau | http://www.shggty.com.cn/facilityMap.html (accessed on 16 November 2025) |

| Permanent Residents | Shanghai Statistical Yearbook | https://tjj.sh.gov.cn/tjnj/index.html (accessed on 16 November 2025) |

| Land Area of Shanghai Districts | Shanghai Statistical Communique on National Economic and Social Development | https://tjj.sh.gov.cn/tjgb/index.html (accessed on 16 November 2025) |

| Location of Shanghai District Government Offices | ||

| Shanghai Basic Geographic Data | Amap | https://lbs.amap.com/tools/picker (accessed on 16 November 2025) |

| Variable Type | Variable Name | Variable Meaning |

|---|---|---|

| Dependent Variable | Spatial Matching Degree Coefficient (Y) | Matching degree coefficient between the community public sports facility system and the population system |

| Independent Variables | Topographic Conditions (X1) | Average elevation data of each district |

| Location Characteristics (X2) | Euclidean distance between the spatial position of each district government and the spatial position of each district’s Central Business District | |

| Economic Development Level (X3) | Gross Domestic Product (GDP) of each district divided by the total construction land area of each district | |

| Traffic Conditions (X4) | Average road network density of the traffic network in each district | |

| Construction Intensity (X5) | Construction land area of each district divided by the administrative division area of each district | |

| Resident Activity Intensity (X6) | Number of Points of Interest (POI) in each district divided by the administrative division area of each district | |

| Housing Price (X7) | Average housing price of each district |

| District Type | District Name | Annual Average Growth Rate of Community Sports Facilities (%) | Annual Average Growth Rate of Permanent Residents (%) | Sports Facility–Population Growth Elasticity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Central Urban Districts | Huangpu District | 0.400 | −0.020 | −20.182 |

| Xuhui District | 0.202 | 0.014 | 14.335 | |

| Changning District | 0.091 | 0.008 | 11.121 | |

| Jing’an District | 0.208 | 0.000 | −39.98 | |

| Putuo District | 0.097 | 0.029 | 3.319 | |

| Hongkou District | 0.147 | 0.000 | −46.26 | |

| Yangpu District | 0.162 | 0.012 | 13.431 | |

| Semi-Central Urban District | Pudong New Area | 0.489 | 0.076 | 6.470 |

| Suburban Districts | Minhang District | 0.648 | 0.160 | 4.060 |

| Baoshan District | 0.750 | 0.084 | 8.948 | |

| Jiading District | 0.653 | 0.125 | 5.216 | |

| Jinshan District | 0.769 | 0.028 | 27.040 | |

| Songjiang District | 0.941 | 0.141 | 6.681 | |

| Qingpu District | 1.669 | 0.090 | 18.469 | |

| Fengxian District | 7.986 | 0.072 | 111.13 | |

| Chongming District | 8.236 | 0.003 | 236.33 | |

| Average | Shanghai | 0.413 | 0.046 | 8.954 |

| Independent Variables | Classification Methods | Number of Categories |

|---|---|---|

| Terrain Conditions (X1) | Jenks | 6 |

| Location Characteristics (X2) | Jenks | 5 |

| Economic Development Level (X3) | Quantile | 7 |

| Traffic Conditions (X4) | Jenks | 6 |

| Construction Intensity (X5) | Jenks | 6 |

| Resident Activity Intensity (X6) | Quantile | 7 |

| Housing Price (X7) | Quantile | 7 |

| Variables | Model 1 (OLS) | Model 2 (Individual Fixed) | Model 3 (Two-Way Fixed) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | 2.14 *** | 1.89 *** | 1.56 * |

| X3: Economic Development Level | −0.32 ** | −0.41 *** | −0.45 * |

| X7: Housing Price | 0.18 * | 0.22 ** | 0.28 * |

| X4: Traffic Accessibility | −0.15 ** | −0.12 * | −0.19 |

| X5: Construction Intensity | −0.09 | −0.11 * | −0.14 |

| X6: Residents Activity Intensity | 0.45 *** | 0.38 *** | 0.33 * |

| Controls | No | Yes | Yes |

| Year FE | No | No | Yes |

| District FE | No | Yes | Yes |

| Obs | 64 | 64 | 64 |

| Adj. R-squared | 0.452 | 0.685 | 0.768 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Hui, L.; Ye, P. Aligning Supply and Demand: The Evolution of Community Public Sports Facilities in Shanghai, China. Sustainability 2026, 18, 1209. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18031209

Hui L, Ye P. Aligning Supply and Demand: The Evolution of Community Public Sports Facilities in Shanghai, China. Sustainability. 2026; 18(3):1209. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18031209

Chicago/Turabian StyleHui, Lyu, and Peng Ye. 2026. "Aligning Supply and Demand: The Evolution of Community Public Sports Facilities in Shanghai, China" Sustainability 18, no. 3: 1209. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18031209

APA StyleHui, L., & Ye, P. (2026). Aligning Supply and Demand: The Evolution of Community Public Sports Facilities in Shanghai, China. Sustainability, 18(3), 1209. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18031209