Revisiting the Waste Kuznets Curve: A Spatial Panel Analysis of Household Waste Fractions Across Polish Sub-Regions

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Related Literature

- reducing the total amount of waste generated by changing consumption patterns;

- increasing resource recovery and closed-loop recycling.

3. Method

- Y—fractions of total waste (paper and cardboard (PC), glass (GL), bulky waste (BW), biowaste (BI));

- ER—earnings level;

- RT, TR, UR—control variables: share of population of retirement age, tourists per 1000 inhabitants, and urbanisation rate (%);

- W—spatial weight matrices based on contiguity (Wc) and distance (Wd);

- µi, τt—individual (county-specific) and time effects,

- εit—idiosyncratic error term,

- β, ρ, θ, λ—parameters.

4. Empirical Results

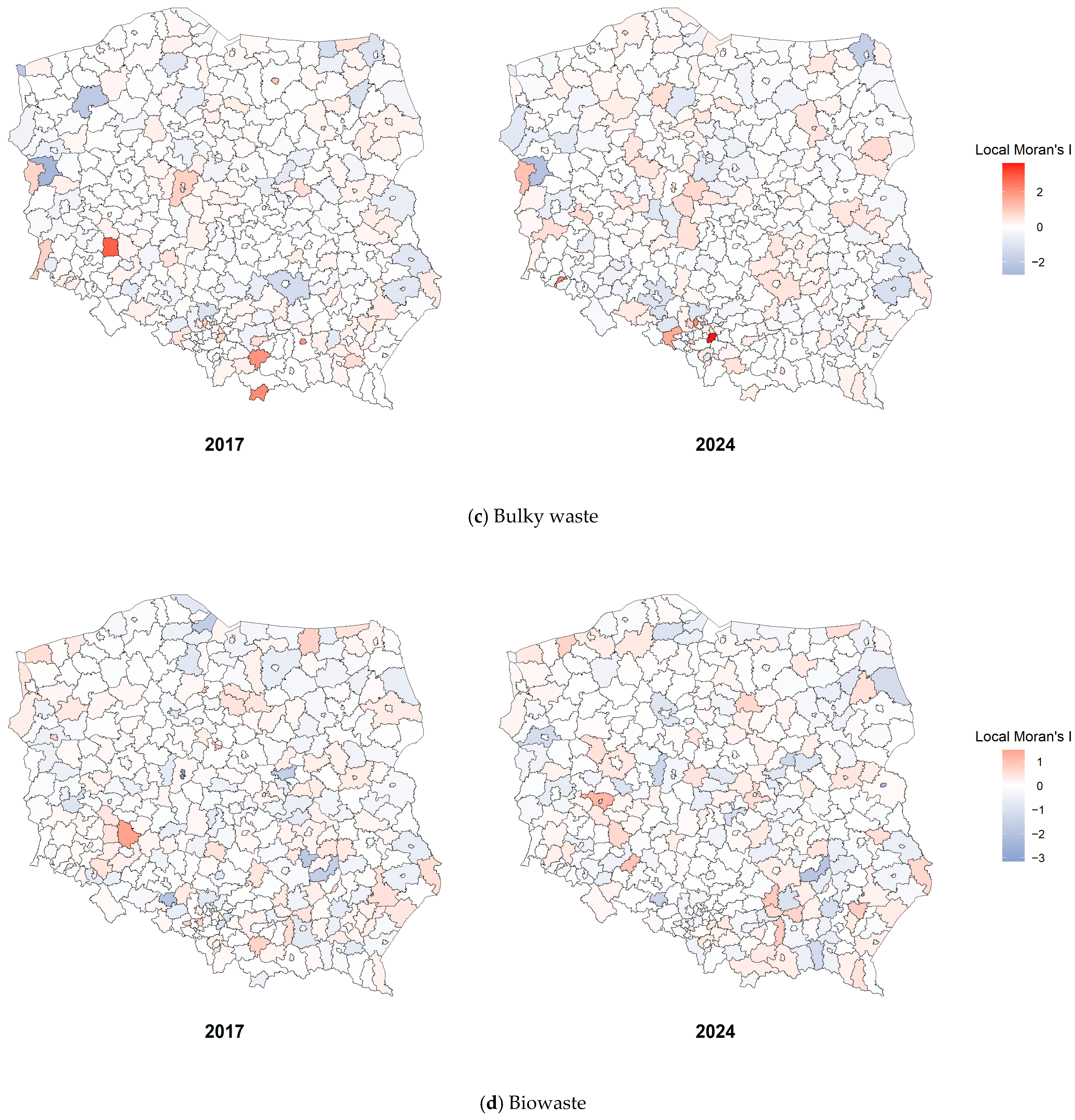

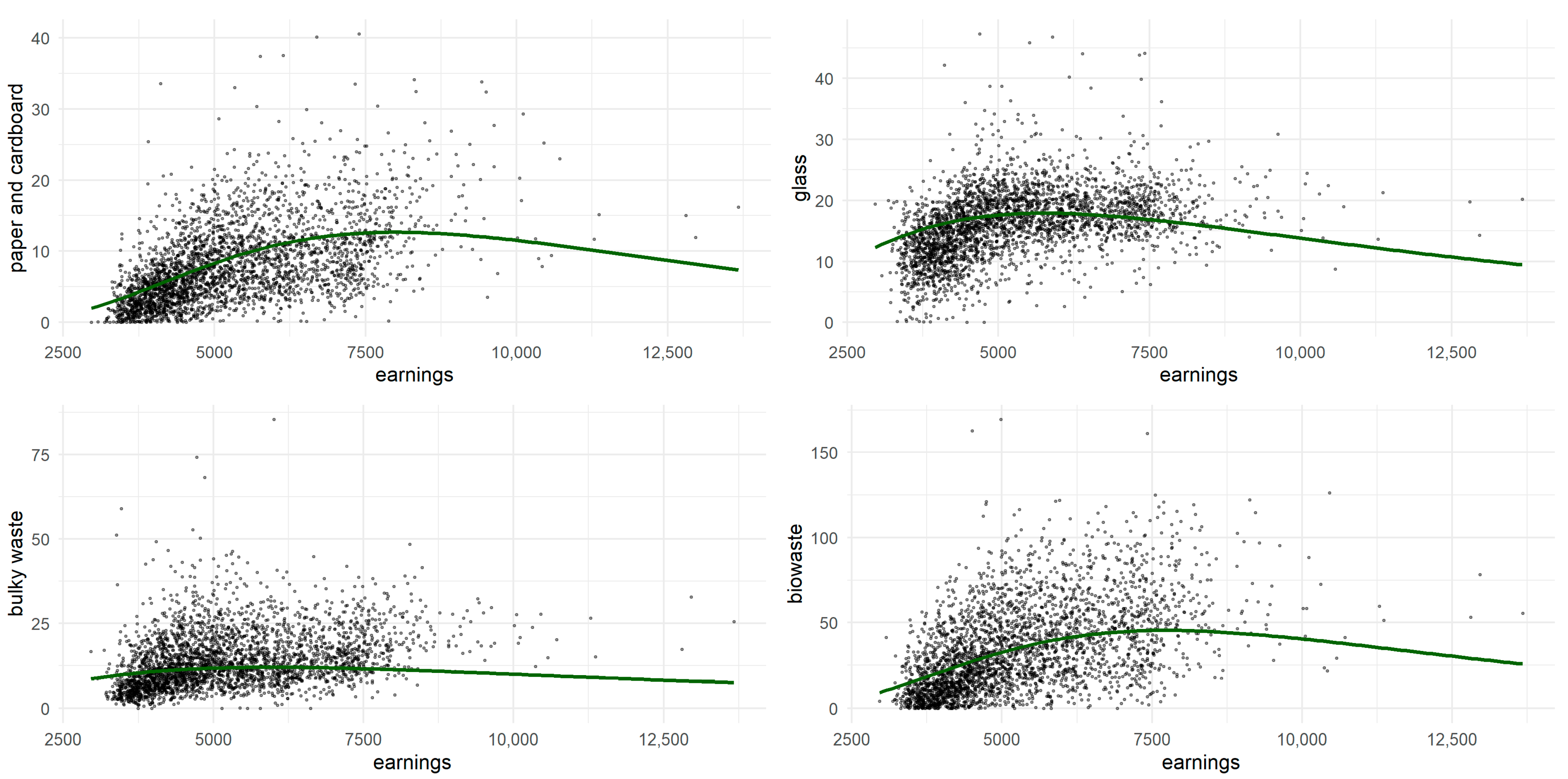

4.1. Spatial Distribution of Waste Fractions

4.2. Spatial Panel Models of Waste Fractions

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kaza, S.; Yao, L.; Bhada-Tata, P.; Van Woerden, F. What a Waste 2.0: A Global Snapshot of Solid Waste Management to 2050; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ari, I.; Sentürk, H. The relationship between GDP and methane emissions from solid waste: A panel data analysis for the G7. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2020, 23, 282–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arbulú, L.J.; Rey-Maquieira, J. Tourism and solid waste generation in Europe: A panel data assessment of the environmental Kuznets curve. Waste Manag. 2015, 46, 628–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, A.; Yu, L.; Yang, Q. Characteristics and Forecasting of Municipal Solid Waste Generation in China. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- İçen, H.; Çil, N. Investigating municipal waste Kuznets curve for 22 OECD countries. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2023, 195, 1506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voukkali, I.; Papamichael, I.; Loizia, P.; Zorpas, A.A. Urbanization and solid waste production: Prospects and challenges. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2024, 31, 17678–17689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Kim, J.; Chong, W.K. Causes of municipal solid waste and greenhouse gas emissions from the waste sector in the United States. Waste Manag. 2016, 56, 593–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magazzino, C.; Mele, M.; Schneider, N. The relationship between municipal solid waste and greenhouse gas emissions: Evidence from Switzerland. Waste Manag. 2020, 113, 508–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gui, X.D.; Li, H.M. Empirical study of environmental Kuznets curve. China Popul. Resour. Environ. 2010, 5, 5–8. [Google Scholar]

- Farhani, S.; Mrizak, S.; Chaibi, A.; Rault, C. The environmental Kuznets curve and sustainability: A panel data analysis. Energy Policy 2014, 71, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ercolano, S.; Gaeta, L.; Ghinoi, S.; Silvestri, F. Kuznets curve in municipal solid waste production: An empirical analysis based on municipal-level panel data from Lombardy (Italy). Ecol. Indic. 2018, 93, 397–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trujillo-Lora, J.C.; Carrillo, B.B.; Charris Vizcaíno, C.A.; Iglesias-Pinedo, W.J. The environmental Kuznets curve (EKC): An analysis of landfilled solid waste in Colombia. Rev. Fac. Cienc. Econ. 2013, 21, 7–16. [Google Scholar]

- Gui, S.; Zhao, L.; Zhang, Z. Does municipal solid waste generation in China support the environmental Kuznets curve? New evidence from spatial linkage analysis. Waste Manag. 2019, 84, 310–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madden, B.J.; Florin, N.; Mohr, S.; Giurco, D. Using the waste Kuznets curve to explore regional variation in the decoupling of waste generation and socioeconomic indicators. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 149, 674–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gnonlonfin, A.; Kocoglu, Y.; Péridy, N. Municipal solid waste and development: Environmental Kuznets curve evidence for Mediterranean countries. Reg. Dev. 2017, 45, 113–130. [Google Scholar]

- Ichinose, D.; Yamamoto, M.; Yoshida, Y. Reexamining the Waste–Income Relationship; GRIPS Discuss. Pap., 10-31; National Graduate Institute for Policy Studies: Tokyo, Japan, 2011; pp. 10–31. [Google Scholar]

- Jaligot, R.; Chenal, J. Decoupling municipal solid waste generation and economic growth in the canton of Vaud, Switzerland. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2018, 130, 260–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C. Spatial inequality in municipal solid waste disposal across regions in developing countries. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2010, 7, 447–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Nie, Y. Municipal solid waste characteristics and management in China. J. Air Waste Manag. Assoc. 2001, 51, 250–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, E.C.Y.; Chen, Y.T. Policy or income to affect the generation of medical wastes: An application of the environmental Kuznets curve using Taiwan as an example. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 188, 489–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rom, P.; Guillotreau, P. Mismanaged plastic waste and the environmental Kuznets curve: A quantile regression analysis. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2024, 202, 116320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, S.; Bobeică, M.; Beciu, S.; Arghiroiu, G.A. Is there a food waste Kuznets curve? Evidence from China, Romania, and Switzerland. Environ. Prot. Res. 2023, 3, 233–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Jia, R.; Xu, J.; Wei, Y.; Li, Q.; Yao, Y.; Zhu, X.; Xu, A.; Zhang, J. Research on environmental Kuznets curve of construction waste generation based on China’s provincial data. Sustainability 2024, 16, 5610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Zhang, X.; Wu, Q. Testing the existence of the waste Kuznets curve hypothesis in 45 emerging economies: Evidence from an e-waste panel data survey. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 373, 123812. [Google Scholar]

- Boubellouta, B.; Kusch-Brandt, S. Determinants of e-waste composition in the EU28+2 countries: A panel quantile regression evidence of the STIRPAT model. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 19, 10493–10510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossman, G.M.; Krueger, A.B. Environmental Impacts of a North American Free Trade Agreement; NBER Work. Pap.; NBER: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1991; 3914p. [Google Scholar]

- Shafik, N.; Bandyopadhyay, S. Economic Growth and Environmental Quality: Time Series and Cross-Country Evidence; World Dev. Rep. 1992 Background Pap; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Holtz-Eakin, D.; Selden, T.M. Stoking the Fires? CO2 Emissions and Economic Growth; NBER Work. Pap.; NBER: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1992; 4248p. [Google Scholar]

- Chavas, J.P. On impatience, economic growth and the EKC: A dynamic analysis of resource management. Environ. Resour. Econ. 2004, 28, 123–152. [Google Scholar]

- Andreoni, J.; Levinson, A. The simple analytics of the environmental Kuznets curve. J. Public Econ. 2001, 80, 269–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brock, W.A.; Taylor, S.M. The Green Solow Model; NBER Work. Pap.; NBER: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2004; p. 10557. [Google Scholar]

- Sinha, A.; Schneider, N.; Song, M.; Shahzad, U. The determinants of solid waste generation in the OECD: Evidence from cross-elasticity changes in a common correlated effects framework. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2022, 182, 106322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzanti, M.; Zoboli, R. Municipal waste Kuznets curves: Evidence on socio-economic drivers and policy effectiveness from the EU. Environ. Resour. Econ. 2009, 44, 203–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mele, M.; Magazzino, C.; Schneider, N.; Gurrieri, A.R.; Golpira, H. Innovation, income, and waste disposal operations in Korea: Evidence from spectral Granger causality and artificial neural networks. Econ. Polit. 2022, 39, 1–33. [Google Scholar]

- Halpern, A.L. The Economics of Sustainable Development; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Sjostrom, M.; Ostblom, G. Decoupling waste generation from economic growth—A CGE analysis of the Swedish case. Ecol. Econ. 2010, 69, 1545–1552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coase, R.H. The problem of social cost. J. Law Econ. 1960, 3, 1–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzanti, M. Is waste generation de-linking from economic growth? Empirical evidence for Europe. Appl. Econ. Lett. 2008, 15, 287–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liddle, B. Population, affluence, and environmental impact across development: Evidence from panel cointegration modeling. Environ. Model. Softw. 2013, 40, 255–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, N. Endogeneity and other problems in curvilinear income–waste response function estimations. Stoch. Environ. Res. Risk Assess. 2024, 38, 357–382. [Google Scholar]

- Gardiner, R.; Hájek, P. Municipal waste generation, R&D intensity, and economic growth nexus: A case of EU regions. Waste Manag. 2020, 114, 124–135. [Google Scholar]

- Halkos, G.; Petrou, K.N. The relationship between MSW and education: WKC evidence from 25 OECD countries. Waste Manag. 2020, 114, 240–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, Y.; Jia, L.X.; Hou, Y.; Wu, X. The impact of economic growth and tiered medical policy on medical waste generation: An empirical analysis based on the environmental Kuznets curve model. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10, 873921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konat, G.; Dürrü, Z.; Han, A. Investigation of waste Kuznets curve hypothesis in selected OECD member EU countries: Panel data analysis. Akad. Yaklaşımlar Derg. 2024, 15, 1028–1049. [Google Scholar]

- Cavalheiro, E.A.; Machado, R.H.; Castro, A.S.; Falck, L.R. Urban solid waste generation and GDP per capita: A global analysis through the lens of the environmental Kuznets curve. Contrib. Cienc. Soc. 2024, 17, e5574. [Google Scholar]

- Soukiazis, E.; Proença, S. Exploring the driving forces of waste generation in Portuguese municipalities. Environ. Dev. Econ. 2020, 26, 340–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusch, S.; Hills, C.D. The link between e-waste and GDP: New insights from pan-European data. Resources 2017, 6, 15. [Google Scholar]

- Boubellouta, B.; Kusch-Brandt, S. Relationship between economic growth and mis-managed e-waste: Panel data evidence from 27 EU countries analyzed under the Kuznets curve hypothesis. Waste Manag. 2021, 120, 85–97. [Google Scholar]

- Shahbaz, M.; Sinha, A. Environmental Kuznets curve for CO2 emissions: A literature survey. J. Econ. Stud. 2019, 46, 106–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinda, S. Environmental Kuznets curve hypothesis: A survey. Ecol. Econ. 2004, 49, 431–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Wang, W.; Lu, S.; Wang, Y.F.; Ren, Z. Analysis of the relationship between economic growth and industrial pollution in Zaozhuang, China—Based on the hypothesis of the environmental Kuznets curve. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2016, 23, 16349–16358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, J.; Ericsson, N.R.; Hendry, D.F. General-to-specific modeling: An overview and selected bibliography. Int. Finance Discuss. Pap. 2005, 10, 838. [Google Scholar]

- Mazzanti, M.; Zoboli, R. Delinking and environmental Kuznets curves for waste indicators in Europe. Environ. Sci. 2005, 2, 409–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Struk, M.; Soukopová, J. Age structure and municipal waste generation and recycling—New challenge for the circular economy. In Proceedings of the Cyprus International Conference on Sustainable Solid Waste Management, Nicosia, Cyprus, 23–25 June 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Rybova, K. Do sociodemographic characteristics in waste management matter? Case study of recyclable generation in the Czech Republic. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-C. Effects of urbanization on municipal solid waste composition. Waste Manag. 2018, 79, 828–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, M.; Zhou, C.; Wang, C.; Jackson, R.B.; Kempes, C.P. Worldwide scaling of waste generation in urban systems. Nat. Cities 2024, 1, 126–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Fariña, E.; Díaz-Hernández, J.J.; Padrón-Fumero, N. The contribution of tourism to municipal solid waste generation: A mixed demand–supply approach on the island of Tenerife. Waste Manag. 2020, 102, 587–597. [Google Scholar]

- Arbulú, I.; Rey-Maquieira, J.; Sastre, F. The impact of tourism and seasonality on different types of municipal solid waste (MSW) generation: The case of Ibiza. Heliyon 2024, 10, e5574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mundlak, Y. On the pooling of time series and cross-sectional data. Econometrica 1978, 56, 69–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Household Waste Practices: New Empirical Evidence and Policy Implications for Sustainable Behaviour; OECD Environment Working Papers, No. 249; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2024; Available online: https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/household-waste-practices_9e5e512c-en.html (accessed on 20 December 2025).

- Florczak, A.; Jabłonowski, J. Consumption over the Life Cycle in Poland; NBP Work. Pap.; Narodowy Bank Polski: Warsaw, Poland, 2016; No. 252. [Google Scholar]

| Authors (Year) | Regional Units | Waste Category | Conclusions | Analysis Methods |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gnonlonfin et al. (2017) [15] | Mediterranean countries | Municipal solid waste | EKC holds mainly for developed countries with very high turning points; for most Mediterranean countries, EKC does not imply short-term MSW reduction | Panel data with controls and missing-data imputation |

| Ercolano et al. (2018) [11] | Lombardy, Italy | Municipal solid waste | Partial WKC support; few municipalities reached a turning point, and many had not yet decoupled | Municipal-level panel regressions |

| Jaligot, Chenal (2018) [17] | The canton of Vaud, Switzerland | Municipal waste | Tax point value (income) (+), tax point value (income2) (−) | Panel regressions |

| Gui et al. (2019) [13] | Chinese cities | Municipal solid waste | No inverted-U; spatial linkage analysis showed MSW did not follow EKC and instead indicated an ongoing positive association with income in many cities | Spatial linkage analysis |

| Madden et al. (2019) [14] | New South Wales, Australia | Municipal waste | Many rural municipalities conformed to WKC; tipping-point ratios varied regionally, indicating relative decoupling in places | Geographically and temporally weighted regression (GTWR) |

| Ari, Sentürk (2020) [2] | G7 countries | CH4 Emissions | Cubic model: GDP (−), GDP2 (+), GDP3 (−), urbanisation (+) | Panel ARDL |

| Halkos, Petrou (2020) [42] | 25 OECD countries. | Municipal solid waste | An inverted U-shape relationship is observed. Interdependence between waste, economic growth and education level. | Panel unit root tests |

| Gardiner, Hajek (2020) [41] | Old and new EU countries | Municipal waste | Old EU countries: GDP (+), R&D intensity (+), heating energy (+), employment rate (+), gross fixed capital (+) New EU countries: GDP (+), R&D intensity (+), heating energy (+), employment rate (−), gross fixed capital (−) | Panel cointegration and causality |

| Boubellouta, Kusch-Brandt (2022) [25] | EU28+2 countries | Disaggregated e-waste categories | Confirmed inverted-U across nearly all quantiles and pooled OLS for all categories, indicating EKC for e-waste categories | STIRPAT + panel quantile regression and pooled OLS |

| Ma et al. (2022) [43] | Eight Chinese cities | Medical waste | Found N-shaped relation and policy (tiered medical reform) altered waste dynamics | EKC models with policy controls and panel data |

| Rom, Guillotreau (2024) [21] | 136 field observation data points located in 67 rivers and 14 countries | Plastic waste | The relationship between economic growth and MPW is not monolithic. In the lower quantiles, up to the 40th percentile, economic growth does not manifest the traditional EKC trajectory. In higher quantiles of plastic waste, the classical EKC relationship begins to take shape. | Quantile regression |

| Mann et al. (2023) [22] | 1510 Chinese, Romanian and Swiss households | Food waste | The concept of EKC can be applied to the problem of food waste. Romanian and Chinese consumers declare more food waste than those in Switzerland, and the differences between the countries can be explained by differences in attitudes and behaviour. | Logit model |

| Konat et al. (2024) [44] | Top ten countries with the highest urban solid waste generation among the OECD member EU countries | Urban solid waste | The negative relationship between per capita urban solid waste generation and per capita real income is invalid. Control variables such as the Human Development Index, population density, and the unemployment rate significantly affect per capita urban solid waste generation. | Panel regression model |

| Wang et al. (2024) [23] | 31 Chinese provinces, municipalities, and autonomous regions | Construction waste | The findings reveal an N-shaped curve pattern for construction waste per capita. The factors influencing construction waste generation are the added value of the secondary industry, labour productivity in the construction industry, GDP per capita, urbanisation rate, year-end resident population, and the technical equipment rate of construction enterprises. | Panel data |

| Xu et al. (2025) [24] | 45 emerging economies | e-waste | The relationship between economic growth and e-waste imports exhibits an inverted U-shaped curve. Most emerging economies remain in a low-income non-decoupling state, with only a few countries achieving high-income absolute decoupling. | Panel data |

| Gnonlonfin et al. (2017) [15] | Mediterranean countries | Municipal solid waste | EKC holds mainly for developed countries with very high turning points; for most Mediterranean countries, EKC does not imply short-term MSW reduction | Panel data with controls and missing-data imputation |

| Ercolano et al. (2018) [11] | Lombardy, Italy | Municipal solid waste | Partial WKC support; few municipalities reached a turning point, and many had not yet decoupled | Municipal-level panel regressions |

| Jaligot, Chenal (2018) [17] | The canton of Vaud, Switzerland | Municipal waste | Tax point value (income) (+), tax point value (income2) (−) | Panel regressions |

| Gui et al. (2019) [13] | Chinese cities | Municipal solid waste | No inverted-U; spatial linkage analysis showed MSW did not follow EKC and instead indicated an ongoing positive association with income in many cities | Spatial linkage analysis |

| Madden et al. (2019) [14] | New South Wales, Australia | Municipal waste | Many rural municipalities conformed to WKC; tipping-point ratios varied regionally, indicating relative decoupling in places | Geographically and temporally weighted regression (GTWR) |

| Ari, Sentürk (2020) [2] | G7 countries | CH4 Emissions | Cubic model: GDP (−), GDP2 (+), GDP3 (−), urbanisation (+) | Panel ARDL |

| Year | County Type | Waste Fraction | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Paper and Cardboard | Glass | Bulky Waste | Biowaste | ||

| 2017 | Urban | 6.1 | 9.9 | 12.7 | 27.1 |

| Rural | 3.4 | 11.2 | 8.4 | 15.5 | |

| 2024 | Urban | 17.2 | 16.9 | 23.1 | 60 |

| Rural | 9.7 | 19 | 16.8 | 49.1 | |

| (1) FE | (2) RE(M) | (3) FE | (4) RE(M) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ln_PC | ln_PC | ln_PC | ln_PC | |

| Main | ||||

| ln_ER | 33.07 *** | 34.01 *** | 6.271 * | 11.24 *** |

| (ln_ER)2 | −1.838 *** | −1.892 *** | −0.314 | −0.621 *** |

| RT | 0.0742 ** | 0.0712 ** | −0.133 *** | −0.0604 ** |

| ln_TR | −0.0495 *** | −0.0489 *** | −0.0062 | −0.0115 |

| UR | 0.0234 | 0.0232 | 0.0443 *** | 0.0397 ** |

| cons | −149.1 *** | −148.9 *** | −50.34 *** | |

| Wc | ||||

| ln_ER | −1.038 * | −0.197 * | ||

| RT | 0.267 *** | 0.0924 *** | ||

| ln_TR | −0.0524 | −0.0507 * | ||

| UR | −0.0198 | −0.00762 *** | ||

| ln_PC | 0.716 *** | 0.733 *** | ||

| e.ln_PC | −0.442 *** | −0.464 *** | ||

| sigma_e | 0.540 *** | 0.540 *** | ||

| sigma_u | 0.405 *** | |||

| Average impact | ||||

| Direct | ||||

| ln_ER | 0.8734 * | 0.6493 *** | ||

| RT | −0.1170 *** | −0.0556 * | ||

| ln_TR | −0.0115 | −0.0173 | ||

| UR | 0.0454 *** | 0.0418 ** | ||

| Indirect | ||||

| ln_ER | −1.3111 | 0.9671 * | ||

| RT | 0.5871 *** | 0.1753 * | ||

| ln_TR | −0.1939 * | −0.2154 ** | ||

| UR | 0.0408 | 0.0783 * | ||

| Total | ||||

| ln_ER | −0.4378 | 1.6164 ** | ||

| RT | 0.4702 *** | 0.1197 | ||

| ln_TR | −0.2054 * | −0.2327 ** | ||

| UR | 0.0862 | 0.1201 * | ||

| Hausman test statistic | 63.01 | 52.55 | ||

| (p-value) | (0.000) | (0.000) | ||

| Turning point (ER) | 8082.87 | 8022.97 | ||

| AIC | 5096.098 | 4432.238 | ||

| BIC | 5132.184 | 4504.41 | ||

| N | 3024 | 3024 | 3024 | 3024 |

| (1) FE | (2) RE(M) | (3) FE | (4) RE(M) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ln_GL | ln_GL | ln_GL | ln_GL | |

| Main | ||||

| ln_ER | 14.70 *** | 14.79 *** | −0.666 | 1.555 |

| (ln_ER)2 | −0.849 *** | −0.854 *** | 0.0384 | −0.0861 |

| RT | 0.142 *** | 0.141 *** | 0.00583 | 0.0411 *** |

| ln_TR | −0.0376 *** | −0.0375 *** | −0.00980 | −0.0112 |

| UR | 0.0183 * | 0.0183 * | 0.0209 ** | 0.0210 *** |

| cons | −64.79 *** | −64.98 *** | −6.032 | |

| Wc | ||||

| ln_ER | −0.411 | −0.186 *** | ||

| RT | 0.127 *** | 0.0189 | ||

| ln_TR | −0.0392 * | −0.0256 | ||

| UR | 0.0206 | 0.00317 ** | ||

| ln_GL | 0.702 *** | 0.787 *** | ||

| e.ln_GL | −0.222 | −0.383 *** | ||

| sigma_e | −0.411 | −0.186 *** | ||

| sigma_u | 0.223 *** | |||

| Average impact | ||||

| Direct | ||||

| ln_ER | −0.0464 | 0.0696 | ||

| RT | 0.0175 | 0.0473 *** | ||

| ln_TR | −0.0139 * | −0.0153 * | ||

| UR | 0.0241 *** | 0.0234 *** | ||

| Indirect | ||||

| ln_ER | −1.3632 *** | −0.5407 | ||

| RT | 0.4261 *** | 0.2333 *** | ||

| ln_TR | −0.1501 ** | −0.1566 ** | ||

| UR | 0.1152 * | 0.0898 *** | ||

| Total | ||||

| ln_ER | −1.4096 *** | −0.4711 | ||

| RT | 0.4436 *** | 0.2806 *** | ||

| ln_TR | −0.1641 ** | −0.1719 ** | ||

| UR | 0.1393 * | 0.1132 *** | ||

| Hausman test statistic | 110.82 | 88.39 | ||

| (p-value) | (0.000) | (0.000) | ||

| Turning point (ER) | 5787.48 | 5789.95 | ||

| AIC | 1161.336 | 788.1647 | ||

| BIC | 1197.422 | 860.3368 | ||

| N | 3024 | 3024 | 3024 | 3024 |

| (1) FE | (2) RE(M) | (3) FE | (4) RE(M) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ln_BW | ln_BW | ln_BW | ln_BW | |

| Main | ||||

| ln_ER | 11.84 *** | 12.03 *** | 1.133 | 0.993 |

| (ln_ER)2 | −0.681 *** | −0.692 *** | −0.0524 | −0.0529 |

| RT | 0.128 *** | 0.128 *** | 0.0475 ** | 0.0375 ** |

| ln_TR | −0.0316 *** | −0.0315 *** | −0.00391 | −0.00369 |

| UR | 0.0292 *** | 0.0291 *** | 0.0215 ** | 0.0272 *** |

| cons | −53.08 *** | −58.81 *** | −7.783 | |

| Wc | ||||

| ln_ER | −0.314 | −0.204 *** | ||

| RT | −0.00239 | 0.0148 | ||

| ln_TR | −0.0229 | −0.0205 | ||

| UR | 0.0170 | −0.000687 | ||

| ln_BW | 0.830 *** | 0.824 *** | ||

| e.ln_BW | −0.917 *** | −0.885 *** | ||

| sigma_e | 0.301 *** | 0.302 *** | ||

| sigma_u | 0.312 *** | |||

| Average impact | ||||

| Direct | ||||

| ln_ER | 0.2215 | 0.0701 | ||

| RT | 0.0527 *** | 0.0438 *** | ||

| ln_TR | −0.0076 | −0.0070 | ||

| UR | 0.0264 *** | 0.0302 *** | ||

| Indirect | ||||

| ln_ER | −0.6612 | −0.7229 * | ||

| RT | 0.2115 * | 0.2518 *** | ||

| ln_TR | −0.1492 * | −0.1299 * | ||

| UR | 0.1987 ** | 0.1198 *** | ||

| Total | ||||

| ln_ER | −0.4397 | −0.6528 | ||

| RT | 0.2642 ** | 0.2956 *** | ||

| ln_TR | −0.1568 * | −0.1369 * | ||

| UR | 0.2251 ** | 0.1500 *** | ||

| Hausman test statistic | 125.29 | 62.33 | ||

| (p-value) | (0.000) | (0.000) | ||

| Turning point (ER) | 5975.21 | 5979.12 | ||

| AIC | 1769.085 | 1492.326 | ||

| BIC | 1805.171 | 1564.498 | ||

| N | 3024 | 3024 | 3024 | 3024 |

| (1) FE | (2) RE(M) | (3) FE | (4) RE(M) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ln_BI | ln_BI | ln_BI | ln_BI | |

| Main | ||||

| ln_ER | 31.06 *** | 31.28 *** | 13.24 *** | 12.97 *** |

| (ln_ER)2 | −1.734 *** | −1.747 *** | −0.716 *** | −0.727 *** |

| RT | 0.149 *** | 0.149 *** | 0.0218 | 0.0311 |

| ln_TR | −0.0473 *** | −0.0472 *** | −0.0171 | −0.0137 |

| UR | 0.0203 | 0.0203 | 0.0262 * | 0.0308 ** |

| cons | −139.6 *** | −135.6 *** | −56.17 *** | |

| Wc | ||||

| ln_ER | −0.723 | −0.183 | ||

| RT | 0.119 * | 0.0598 * | ||

| ln_TR | −0.0681 * | −0.0625 * | ||

| UR | 0.0223 | −0.00275 | ||

| ln_BI | 0.533 *** | 0.618 *** | ||

| e.ln_BI | −0.270 | −0.418 *** | ||

| sigma_e | 0.484 *** | 0.481 *** | ||

| sigma_u | 0.590 *** | |||

| Average impact | ||||

| Direct | ||||

| ln_ER | 0.9949 ** | 0.5637 *** | ||

| RT | 0.0287 | 0.0365 | ||

| ln_TR | −0.0212 | −0.0186 | ||

| UR | 0.02813 * | 0.0319 ** | ||

| Indirect | ||||

| ln_ER | −0.3804 | 0.4177 | ||

| RT | 0.2729 *** | 0.2010 *** | ||

| ln_TR | −0.1608 ** | −0.1804 ** | ||

| UR | 0.0755 | 0.0414 * | ||

| Total | ||||

| ln_ER | 0.6145 | 0.9814 ** | ||

| RT | 0.3016 *** | 0.2374 *** | ||

| ln_TR | −0.1820 ** | −0.1990 *** | ||

| UR | 0.1037 | 0.0733 * | ||

| Hausman test statistic | 107.40 | 43.84 | ||

| (p-value) | (0.000) | (0.000) | ||

| Turning point (ER) | 7753.23 | 7740.76 | ||

| AIC | 4107.035 | 3770.193 | ||

| BIC | 4143.121 | 3842.365 | ||

| N | 3024 | 3024 | 3024 | 3024 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Kijek, A.; Karman, A. Revisiting the Waste Kuznets Curve: A Spatial Panel Analysis of Household Waste Fractions Across Polish Sub-Regions. Sustainability 2026, 18, 1204. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18031204

Kijek A, Karman A. Revisiting the Waste Kuznets Curve: A Spatial Panel Analysis of Household Waste Fractions Across Polish Sub-Regions. Sustainability. 2026; 18(3):1204. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18031204

Chicago/Turabian StyleKijek, Arkadiusz, and Agnieszka Karman. 2026. "Revisiting the Waste Kuznets Curve: A Spatial Panel Analysis of Household Waste Fractions Across Polish Sub-Regions" Sustainability 18, no. 3: 1204. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18031204

APA StyleKijek, A., & Karman, A. (2026). Revisiting the Waste Kuznets Curve: A Spatial Panel Analysis of Household Waste Fractions Across Polish Sub-Regions. Sustainability, 18(3), 1204. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18031204