1. Introduction

Official customs statistics put China’s cross-border e-commerce (CBEC) trade at RMB 2.38 trillion in 2023, a 15.6% year-on-year increase [

1]. This growth adds pressure on logistics systems that already account for a large share of economic activity and involve substantial resource use. Industry reports estimate that cross-border activities accounted for around RMB 2.56 trillion in 2022, or roughly 20–30% of national logistics expenditure [

2]. At this scale, cross-border logistics can entail high transport and packaging intensity, especially where operational mitigation practices remain limited [

3,

4]. Logistics performance is therefore a core determinant of CBED and a key driver of fulfilment frictions and operational intensity as the sector scales. Prior work on cross-border flows has underscored that logistics solutions, risk exposure, and fulfilment reliability play a decisive role in shaping platform competitiveness [

5,

6]. Yet China’s cross-border e-commerce still faces structural bottlenecks in logistics, regulation, and digital infrastructure, and these constraints can undermine service quality and delay shifts toward more resource-efficient fulfilment configurations, particularly through operational frictions and underutilised capacity [

7,

8,

9].

Recent studies suggest that advanced data analytics and automation increasingly influence how logistics networks support CBEC, with implications for operational efficiency and resource use. Empirical and review studies suggest that AI-related applications are shifting toward predictive and optimisation functions, improving planning accuracy, service reliability, and cost efficiency [

10,

11,

12]. In cross-border settings, AI-enabled demand sensing, inventory repositioning, and dynamic routing help platforms respond to live order flows and network conditions, shortening cycle times and reducing empty miles, which can lower operational frictions and improve capacity utilisation at the margin [

13,

14,

15]. At the same time, work on digitalisation and supply chain sustainability warns that such technologies can have “double-edged” effects on operational efficiency and resource use, depending on how they are deployed and governed [

13,

16,

17]. When layered on an already efficient logistics backbone, these capabilities can support higher conversion, fewer returns, and more resilient cross-border market positions. Any sustainability implications are framed in operational terms, emphasising lower frictions and better utilisation within fulfilment operations.

China’s regions differ in their capacity to leverage data-driven logistics tools, with implications for competitiveness and the scope for more resource-efficient fulfilment. Eastern coastal provinces typically combine dense digital infrastructure, mature transport networks, and wider adoption of warehouse and transport management systems, whereas many central and western provinces still face connectivity gaps, skills shortages, and fragmented data architectures [

18,

19]. These differences suggest that the same underlying logistics efficiency may yield different CBED outcomes once AI capabilities are considered and may shape the scope for more resource-efficient fulfilment as CBEC scales. However, existing empirical work provides limited province-level evidence on how logistics efficiency and AI development interact in shaping CBED and seldom compares regions that differ in digital maturity and logistics upgrading [

20,

21]. Prior studies often adopt firm-/platform-level designs that are well-suited to analysing adoption choices and operational outcomes, whereas comparable province-level evidence remains thinner in the CBEC setting. A provincial lens is nonetheless informative because it captures ecosystem-wide foundations—digital infrastructure, interoperability, public investment, and institutional coordination—that condition how AI capability translates into cross-border fulfilment performance across regions. Existing work on CBEC and logistics therefore leaves the following three issues underexplored: the joint role of logistics efficiency and AI capability in shaping CBED, the multidimensional nature of AI development beyond single indicators, and the role of regional digital maturity as a boundary condition for these relationships.

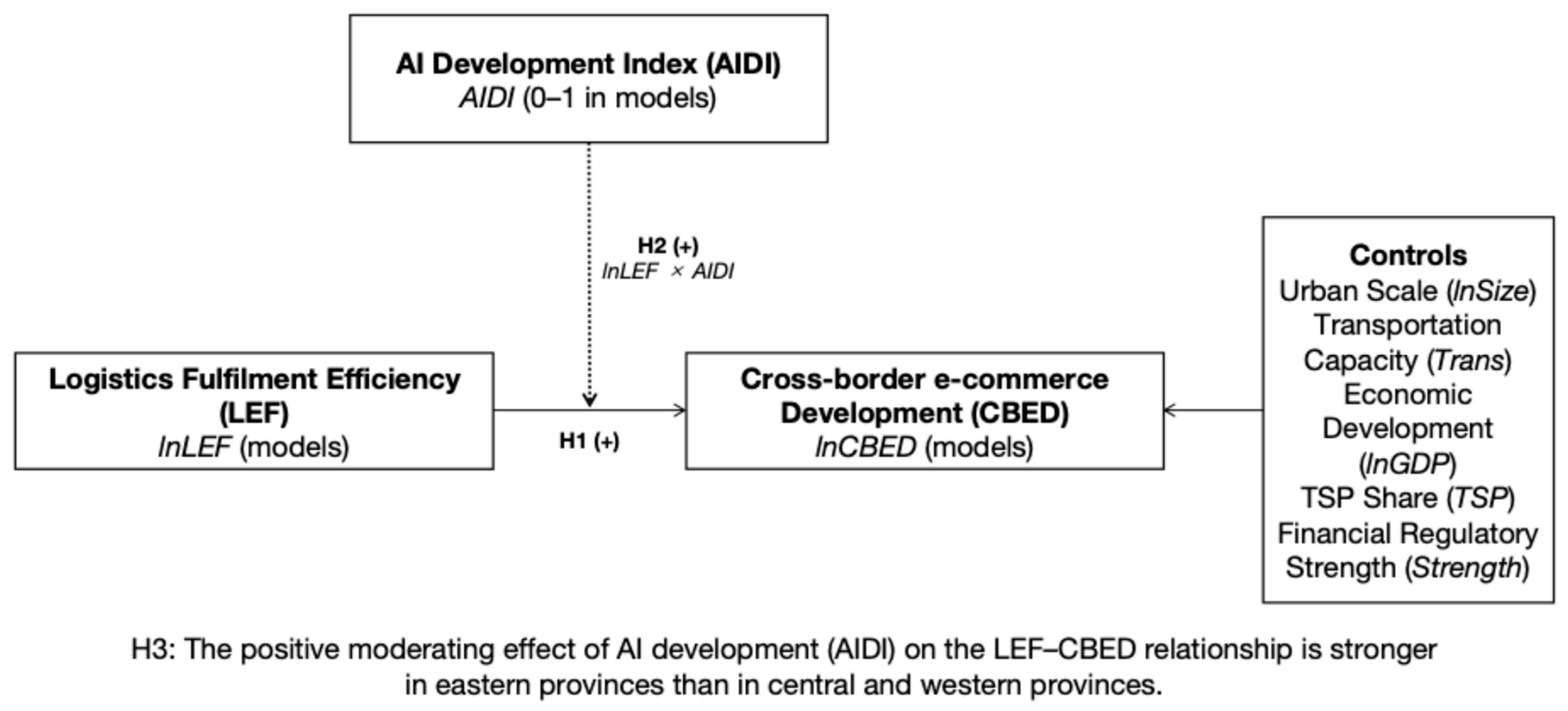

Building on these observations, this study asks how logistics fulfilment efficiency (LEF) and AI development jointly shape CBED at the provincial level. It first examines whether provinces with higher logistics efficiency exhibit stronger cross-border e-commerce development. It then tests whether AI development strengthens the association between logistics efficiency and CBED. Finally, it explores whether this AI–logistics complementarity varies across regions with different levels of digital maturity—namely eastern, central, and western China.

To answer these questions, we compile a provincial panel for thirty-one provinces over 2017–2023. LEF is measured as logistics fulfilment efficiency using Super-SBM DEA, and AIDI is constructed across innovation, application, infrastructure, and market pillars. We estimate dynamic panel models to test the LEF effect, the AIDI interaction, and regional heterogeneity. Conceptually, LEF captures a core fulfilment capability, while AIDI captures a higher-order AI-specific digital capability—spanning innovation, application, infrastructure, and market readiness—linked to sensing, prediction, and operational reconfiguration beyond baseline digital connectivity, consistent with resource-based and dynamic capability views [

22,

23,

24,

25].

The study contributes to research on digital commerce and logistics fulfilment in three ways. It reframes provincial logistics efficiency as a fulfilment capability underpinning CBED. It introduces a province-level AIDI and embeds it in a dynamic panel setting to quantify how digital capability conditions the CBED–logistics link. It also documents regional heterogeneity in this complementarity across eastern, central, and western China, highlighting the digital divide as a boundary condition and supporting differentiated digital–logistics policy design [

26].

For platforms and policymakers, the arguments imply practical priorities. For cross-border platforms and logistics providers, AI-integrated forecasting and routing are most effective where logistics fundamentals and digital infrastructure are already in place; under such conditions, similar physical logistics efficiency can support different CBED trajectories depending on AI readiness [

11,

27]. For less-developed provinces, strengthening data interoperability, connectivity, and human capital is a prerequisite for realising the operational gains of AI-enabled logistics in supporting CBED and improving fulfilment efficiency, with lower operational frictions when digital and logistics capabilities are strengthened in tandem [

13,

28,

29]. From a policy perspective, the provincial lens shows how AI and logistics capabilities jointly shape electronic commerce development under pronounced regional heterogeneity and provides a basis for region-tailored investment roadmaps primarily linked to SDG 9 (Industry, Innovation, and Infrastructure), with indirect relevance to SDG 12 (Responsible Consumption and Production) and SDG 13 (Climate Action) through more efficient resource use within fulfilment operations, reflected in reduced operational frictions and improved utilisation [

30,

31,

32].

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Data Sources and Sample

The analysis uses a balanced panel for 31 mainland Chinese provinces (excluding Hong Kong, Macao, and Taiwan) over 2017–2023, yielding 217 province–year observations. Provinces are grouped into eastern (11), central (8), and western (12) regions following the National Bureau of Statistics classification, allowing AI–logistics fulfilment relationships to be compared across development zones.

All variables are taken from official and widely used statistical sources. Cross-border e-commerce development (CBED) is measured using customs-recorded cross-border e-commerce (CBEC) import and export values from the China Customs Statistics Yearbook. Logistics inputs and outputs for the efficiency measures come from the China Logistics Yearbook and official yearbooks. Indicators for the Artificial Intelligence Development Index (AIDI) are drawn from the China Statistical Yearbook on Science and Technology, China National Intellectual Property Administration (CNIPA) patent statistics, Web of Science and CNKI records, and the China Electronic Information Industry Statistical Yearbook. The five control variables—urban scale (Size), transportation capacity (Trans), economic development (lnGDP), transportation, storage and postal services (TSP), and financial regulatory strength (Strength)—are constructed from the China Statistical Yearbook, the China Transport Statistical Yearbook, provincial yearbooks, and financial supervision reports.

We then apply a conservative data-cleaning procedure across all indicators and province–year entries. Missing values are limited and confined to a small number of province–year entries. Linear interpolation is applied only when adjacent observations support a smooth year-to-year pattern; it is used to preserve sample continuity rather than to reconstruct discontinuous shocks. Where the pattern suggests a structural shift, we avoid trend-based interpolation and instead use within-province time-series mean imputation for that indicator; series with clear discontinuities are left unimputed to prevent introducing artificial jumps. All monetary variables are deflated to 2017 constant prices using provincial consumer price indices and then logged. The dataset contains no individual-level information and does not raise ethical concerns. All raw inputs draw on customs and statistical yearbooks and cannot be redistributed in raw form. Upon reasonable request, the corresponding author can provide replication code and derived indices, subject to source and licencing constraints.

3.2. Variable Measurement

3.2.1. Dependent Variable: Cross-Border E-Commerce Development (CBED)

Cross-border e-commerce development (CBED) is measured as the natural logarithm of the sum of provincial CBEC import and export values recorded in customs statistics (lnCBED). All underlying monetary series are deflated to 2017 constant prices using provincial consumer price indices. For descriptive summaries, CBED is reported as a normalised index for presentation, while the regression models use lnCBED. This specification follows recent work that treats customs-recorded CBEC transaction values as a systematic proxy for China’s cross-border e-commerce activity. Detailed definitions, data sources, and processing steps for the CBED indicator are summarised in

Appendix A.1 (

Table A1).

3.2.2. Independent Variable: Logistics Fulfilment Efficiency (LEF)

Logistics fulfilment performance rests on multiple inputs—capital, labour, and energy. To capture this multi-input, multi-output structure, we use a data envelopment analysis (DEA) super-efficiency slacks-based measure (Super-SBM) model under variable returns to scale (VRS). This specification benchmarks provinces with different economic sizes and network densities against a best-practice frontier and yields a full ranking of decision-making units. The model structure is compatible with undesirable outputs in principle; however, in this study, LEF is constructed as a fulfilment-efficiency measure using harmonised logistics inputs and desirable service outputs and is interpreted as an operational efficiency indicator rather than a direct environmental-performance metric [

45,

46]. Undesirable outputs are not incorporated because province-level proxies that can be consistently measured and credibly attributed to fulfilment activities are not available in a harmonised form over the full 2017–2023 period.

The input set includes investment in transportation, storage, and postal services, employment in logistics-related sectors and energy consumption. Energy consumption is included as part of the operational input bundle for fulfilment activities; accordingly, LEF should be interpreted as a composite fulfilment-efficiency measure under a harmonised input–output specification. The main desirable output is freight turnover (ton-kilometres), capturing the volume of transport services. Although some logistics DEA studies incorporate undesirable outputs (e.g., environmental-externality proxies), our implementation prioritises comparability and coverage across provinces and years. Accordingly, the Super-SBM set-up is applied using consistently available logistics inputs and service outputs, and sustainability is interpreted later in operational terms—lower frictions and better utilisation [

16,

17]. Super-SBM inputs/outputs underpinning the fulfilment-efficiency measure (LEF) are defined in

Section 3 and listed in

Appendix A.2 (

Table A2).

Appendix A.2 clarifies that LEF is linearly rescaled to the 0–1 interval for descriptive reporting, whereas regressions use lnLEF computed from the raw Super-SBM efficiency scores (not truncated).

Provincial Super-SBM fulfilment-efficiency scores are computed annually. LEF is transformed as lnLEF = ln(max(LEF,ε)), where ε = 0.001 is used to avoid undefined values when Super-SBM scores are close to zero. This treatment ensures numerical stability and preserves cross-provincial variation for the log-linear dynamic panel specifications in

Section 3.3.

3.2.3. Moderating Variable: Artificial Intelligence Development Index (AIDI)

Provincial AI maturity is measured by an Artificial Intelligence Development Index (AIDI) spanning the following four dimensions: innovation, digital infrastructure, application, and market environment [

9,

47]. The innovation pillar aggregates AI-related patents granted by the China National Intellectual Property Administration (CNIPA) and AI-focused academic publications in Web of Science and CNKI, capturing the codified AI knowledge base. The digital infrastructure pillar uses indicators on 5G base-station density, broadband penetration, and data-centre capacity from official statistical yearbooks, proxying the connectivity and computing backbone for large-scale AI deployment.

The application pillar uses proxies for firm-level AI adoption, such as counts of AI-oriented software and information-service enterprises and deployments of intelligent systems in logistics and manufacturing [

27,

28]. The market-environment pillar combines operating revenue or value added in AI-related industries with counts of AI-oriented firms from the China AI Development Report and provincial yearbooks, reflecting the local AI business ecosystem.

All indicators are coded so that higher values reflect more advanced AI development and are min–max normalised to [0, 1]. Pillar scores are the mean of the normalised indicators within each dimension and entropy-based weights are applied across pillars; AIDI is the weighted sum of the four pillars (0–1). For descriptive tables, AIDI is rescaled to 1–9, while regressions use the original 0–1 index. Alternative indices with equal weights or principal components yield similar results [

12,

48], indicating that the findings are not sensitive to the weighting scheme. Construction steps are documented in

Appendix A.3, and the principal-component-based alternative index (AIDI_alt) is reported in

Appendix A.4 (

Table A3).

3.2.4. Control Variables

To isolate the effects of logistics fulfilment efficiency and AI development, the models include the following five provincial controls: urban scale (Size), transportation capacity (Trans), economic development (lnGDP), the share of transportation, storage, and postal services (TSPs), and financial regulatory strength (Strength). Size is the natural logarithm of the urban population, capturing agglomeration forces that typically boost logistics demand and e-commerce activity, while Trans is an index combining road density and freight turnover per capita as a proxy for network capacity. lnGDP is the natural logarithm of provincial GDP per capita in 2017 prices, and TSP is the share of transportation, storage, and postal services in provincial value added, indicating the maturity and relative importance of logistics-related services. Strength is a composite index based on provincial financial supervision and regulation indicators and summarises the local institutional framework for digital- and logistics-related innovation [

25].

In the regressions, Size and lnGDP enter in logarithmic form and Trans, TSP, and Strength as indices; descriptive statistics for all variables are reported in Table 1. Additional digital-economy indicators such as internet penetration and human-capital measures were examined but were highly collinear with components of AIDI and unevenly available across provinces. Because AIDI already captures much of the digital infrastructure and skills environment, these variables are excluded, and any residual omitted-variable bias is acknowledged as a limitation in

Section 5.4.

3.3. Model Specification

To test the hypotheses while accounting for dynamic persistence, endogeneity, and unobserved provincial heterogeneity, we estimate dynamic panel models using the two-step System GMM estimator [

49,

50,

51], which is suited to panels with a short time dimension and a lagged dependent variable.

The baseline specification without the AI–logistics interaction is:

where

indexes provinces and

indexes years;

denotes cross-border e-commerce development,

is the logistics fulfilment-efficiency measure,

is the vector of control variables (Size, Trans, lnGDP, TSP, and Strength), and

and

are province and year fixed effects.

To incorporate AI development, we extend the model by adding

and its interaction with

:

The interaction term () captures AI–fulfilment complementarity; shows how AI development changes the marginal effect of fulfilment efficiency on CBED.

In the System GMM specifications,

is treated as predetermined and instrumented using deeper lags, while

is treated as endogenous given potential simultaneity between fulfilment upgrading and CBED. In Equation (2),

and the interaction term (

) are also treated as endogenous to preserve consistency of the moderation test. The remaining controls enter as weakly exogenous (or predetermined where appropriate), and year dummies are treated as strictly exogenous. To limit instrument proliferation with a small number of groups (N = 31), we use collapsed instrument sets and restrict the GMM-style lag window to lags

t − 2 and

t − 3, balancing relevance and parsimony in a short panel [

51]. We report two-step estimates with Windmeijer [

52] finite-sample corrections and evaluate model adequacy using AR(1)/AR(2) tests and the Hansen J-test. The estimates are therefore interpreted as dynamic associations identified by internal instruments and potential feedback between CBED and AI development cannot be fully excluded. While difference-in-Hansen subset tests can be informative, instrument validity is assessed here through the Hansen test together with conservative instrument construction.

For regional heterogeneity, Equation (2) is estimated separately for eastern, central, and western subsamples, and Wald tests assess whether

differs across regions. For clarity, each hypothesis corresponds to a specific estimand in the empirical models. H1 is tested using the coefficient on lnLEF in Equation (1). H2 is tested using the interaction coefficient lnLEF × AIDI in Equation (2), and the implied marginal effect of lnLEF is evaluated at representative AIDI values. H3 is assessed by comparing the interaction estimates across eastern, central, and western subsamples using pairwise Wald tests. For regional heterogeneity, Equation (2) is estimated separately for eastern, central, and western subsamples, and Wald tests assess whether

differs across regions. Robustness checks include difference GMM, alternative DEA specifications for LEF, different AIDI constructions (entropy-weighted, equal-weighted, and principal-component based), variations in lag and instrument structure, and fixed-effects models with Driscoll–Kraay standard errors. The corresponding robustness outputs are reported in

Appendix A.4,

Appendix A.5 and

Appendix A.6 [

34,

48,

53].

5. Discussion and Implications

5.1. Purpose and Integrated Summary of Findings

This study examines how provincial logistics fulfilment efficiency (LEF) and artificial intelligence development (AIDI) relate to cross-border e-commerce development (CBED) in China, and whether these relationships vary across regions. Using a balanced panel of thirty-one provinces (2017–2023), we estimate two-step System GMM models with LEF, AIDI, CBED, and standard controls, and repeat the analysis for eastern, central, and western subsamples. We focus on complementarity—whether AIDI changes the marginal return of LEF for CBED and what this implies for region-calibrated development paths.

The estimates align with H1–H3 in three respects. First, logistics fulfilment efficiency (LEF) is consistently associated with higher CBED after accounting for persistence and structural differences in provincial economic conditions. Substantively, LEF captures fulfilment capability: better warehousing, connectivity, and clearance capacity reduce operational frictions in cross-border fulfilment. LEF is interpreted as a fulfilment-efficiency capability (LEF) and discussed through operational channels (e.g., frictions and utilisation).

Second, higher AI development is associated with a stronger—rather than substitutive—relationship between logistics fulfilment efficiency (LEF) and CBED in the dynamic estimates. The link between LEF and CBED becomes more pronounced as AI maturity rises, which is consistent with provinces with deeper AI ecosystems being more capable of scaling cross-border activity from a given fulfilment base. Operationally, AI-enabled forecasting, routing, and inventory decisions are often linked to higher throughput and lower coordination waste in platform fulfilment settings. This pattern is consistent with AI–fulfilment complementarity: higher AIDI is associated with a larger marginal association between LEF and CBED, potentially reflecting lower coordination frictions and improved utilisation within fulfilment operations.

Third, the strength of this synergy differs across space. The interaction is most pronounced in the eastern region and remains positive but smaller in central and western provinces, consistent with gaps in platform ecosystems, digital infrastructure, interoperability, and skills. The divide is also about coupling capacity: where foundations are mature, AI is embedded in routine decisions and LEF improvements translate into larger CBED gains. Where foundational digital conditions and skills lag, comparable physical upgrades may deliver slower payoffs and smaller CBED responses to comparable fulfilment upgrades. These findings motivate the region-calibrated implications that follow.

5.2. Theoretical Contributions

This study shows that AIDI acts as a higher-order capability that raises the return to LEF, rather than a stand-alone input. In the resource-based and dynamic capability tradition, advantage comes from integrating and reconfiguring operational assets as conditions change [

22,

23]. The stable, positive interaction between lnLEF and AIDI (lnLEF × AIDI) reported in

Section 4 supports the following logic: provinces with stronger AI ecosystems obtain larger CBED gains from a comparable improvement in fulfilment efficiency (LEF). This mechanism sharpens the contribution to platform-oriented research. The key issue is capability matching: how AIDI aligns with the fulfilment environment to shape differentiated CBED paths across provinces [

10,

36,

55].

The study also extends smart logistics and digital supply chain research by shifting “AI-enabled logistics” from firm-level KPI outcomes to a provincial ecosystem mechanism that matters for CBEC scale-up. Much of the literature evaluates AI through firm-level outcomes such as cost, service levels, or resilience [

10,

56]. By combining a DEA-based fulfilment-efficiency measure (LEF) with a composite AI development index in a dynamic System GMM framework, this study connects upstream fulfilment capability to downstream CBED growth at the provincial level. Fulfilment performance is shaped by a coupled system—public infrastructure, 3PL capacity, regulatory interfaces, and platform orchestration [

8,

14]. In this framing, AI contributes by improving coordination—forecasting, routing, inventory planning, and exception handling—so that existing physical networks are used with lower frictions and higher utilisation. This aligns with Industry 4.0 arguments that digital tools raise logistics productivity, conditional on the physical layer [

11,

57].

Finally, the regional heterogeneity documented in

Section 4 advances the digital divide literature by highlighting capability matching as a distinct source of spatial divergence, beyond average gaps in income or infrastructure. Prior work on China emphasises uneven innovation capacity, digital foundations, and institutional conditions across regions [

19,

21,

58]. The present findings add that provinces differ in the strength of AI–fulfilment complementarity itself: some regions can embed AI into routine fulfilment decisions and convert logistics improvements into stronger CBED responses, while others see weaker payoffs from similar physical upgrading because interoperability, skills, and ecosystem readiness lag. This “capability-mismatched” pattern offers a tighter interpretation of H3 than a level-only explanation. It also matters for the Sustainability-oriented repositioning of the paper, because smart logistics gains are closely tied to reducing operational inefficiencies (e.g., idle capacity, avoidable detours, and fragmented planning). Regions with weaker operationalisation may face a spatial divide in aligning CBED expansion with lower-waste fulfilment trajectories [

9,

17].

5.3. Implications for Sustainability, Policy, and Practice

The implications align primarily with SDG 9, with indirect relevance to SDG 12 and SDG 13. In this study, higher LEF reflects fewer frictions in warehousing, transport connectivity, and clearance capacity, and is therefore consistent with more reliable fulfilment for cross-border transactions. LEF is discussed through operational efficiency channels, reflecting lower operational waste and better utilisation potential in fulfilment. AIDI matters because it strengthens the LEF–CBED link, consistent with planning and coordination functions—forecasting, routing, inventory allocation, and exception handling—that can reduce avoidable delays and redundant movements. The regional results further indicate unequal coupling capacity: provinces with stronger digital foundations and ecosystem readiness appear better able to embed data-driven tools into routine fulfilment decisions. Accordingly, the sustainability-relevant message concerns enabling conditions for more efficient resource use in fulfilment, framed through operational efficiency channels; LEF is interpreted as fulfilment efficiency rather than environmental performance.

For platforms, merchants, and solution providers, the evidence points to sequenced investments rather than uniform deployment. In higher-AIDI provinces, platforms may prioritise integration-intensive fulfilment solutions (e.g., demand planning, routing, inventory positioning, and exception management), because the interaction pattern indicates stronger returns to LEF where digital capability is deeper. In lower-AIDI provinces, the first-order constraint is often basic readiness—data quality, interface standards, interoperability across actors, and targeted training—before more complex modules can be expected to yield comparable payoffs. For third-party logistics providers and vendors, the AIDI–LEF profile can guide rollout choices: end-to-end solutions are more feasible where integration capacity is present, whereas modular tools that work under partial interoperability may be more appropriate where systems remain fragmented. Across contexts, the managerial implication is to treat fulfilment capability and digital capability as complements and to calibrate implementation to local coupling capacity.

For governments, the policy implication is to invest in complements—data governance, interoperability, and human capital—while coordinating across provinces. In the eastern region, where coupling capacity is stronger, policymakers can pilot measures with diffusion potential: common data standards, supervised sharing mechanisms, and regulatory sandboxes for AI-assisted customs risk screening and clearance coordination. These efforts support SDG 9 and have indirect relevance to SDG 12 and SDG 13 through operational efficiency channels. In central and western regions, priorities may lie in expanding digital infrastructure, building interoperable data platforms, and developing applied analytics skills so that physical upgrades are not pursued in isolation. The results caution against an “assets-without-data” path: capacity expansion without interoperability and skills may yield slower CBED gains and more limited operational efficiency improvements.

The broader implication is that inclusive, efficiency-oriented CBED development is more likely when policies and firm strategies are sequenced and region-calibrated: where foundations are stronger, coordination tools can be embedded more readily and incremental improvements in LEF translate into larger CBED responses; where foundations lag, interoperability and skills remain binding constraints.

5.4. Limitations and Directions for Future Research

Two identification concerns merit caution. Two-step System GMM mitigates heterogeneity and simultaneity concerns but cannot remove all endogeneity. Unobserved policy shocks, changes in provincial regulatory intensity, or platform-side strategy shifts may raise CBED while coinciding with upgrades in LEF or AIDI, and such shocks are only partially absorbed by year effects. In addition, some finer-grained digital-economy and human-capital factors (e.g., skills, platform competition intensity) are not included because of coverage limits and collinearity with AIDI. We also note that future work may complement coefficient-based moderation tests with association-based tools that accommodate mixed-type covariates, especially when key drivers are ordinal, categorical, or potentially nonlinear. One option is to use surrogate-based partial association measures for mixed data to quantify conditional dependence within a unified framework, which may offer a useful robustness or exploratory check alongside interaction regressions [

59]. Future work should strengthen causal leverage through quasi-experimental variation (e.g., staggered CBEC policy pilots, exogenous infrastructure expansions, or discrete changes in customs facilitation) and, where feasible, incorporate a small set of complementary digital indicators using designs that explicitly manage collinearity (e.g., alternative index construction or parsimonious proxies). Diagnostics are reported in

Section 4, but endogeneity cannot be fully ruled out.

A second set of limitations relates to measurement, aggregation, and scope. Province-level panels necessarily average over heterogeneous platforms, merchants, and logistics providers, so the estimates cannot pinpoint which operational routines or contracting arrangements generate higher coupling capacity between AIDI and LEF. Moreover, both LEF and AIDI rely on publicly available statistics: this supports consistent coverage but may introduce measurement error and limits granularity. For instance, AIDI does not isolate optimisation-oriented applications from customer-facing AI, and LEF cannot fully distinguish conventional capacity expansion from digitally coordinated fulfilment improvements. The 2017–2023 window captures an early phase of AI diffusion in logistics, and the models do not explicitly account for cross-province spillovers even though fulfilment networks can span administrative borders. Future research could integrate platform transaction data, logistics tracking records, or customs processing measures to test micro-level mechanisms, refine LEF/AIDI with more specific indicators (e.g., automation intensity, algorithmic routing adoption, and data-sharing coverage), extend the panel beyond 2023, and apply spatial econometric or multi-level designs. Beyond extending the time window, another direction is to allow the effect of AI–fulfilment complementarity to vary over time rather than being constant within a short panel specification. Functional data analysis frameworks can model province-level outcomes as trajectories and enable time-varying relationships, for example, through adaptive function-on-scalar regression approaches [

60].

Finally, external validity and sustainability inferences are bounded. China’s dense platform ecosystems, strong state involvement in infrastructure, and pronounced regional disparities may condition the strength of AIDI–LEF complementarity, so generalisation should be treated as suggestive. Sustainability is discussed through operational channels as follows: LEF does not measure emissions or energy intensity, so decarbonisation outcomes cannot be inferred from the estimates. Future studies can directly link CBED expansion and fulfilment upgrading to environmental indicators (e.g., CO2 intensity, energy use, and packaging waste) where data allow, and test whether higher coupling capacity is associated with measurable environmental outcomes. Cross-country comparisons in other emerging markets and designs that combine econometric evidence with life-cycle assessment or multi-objective optimisation would further clarify when AI–fulfilment complementarity aligns growth in CBED with demonstrable sustainability gains.