Dynamic Analysis of the Mooring System Installation Process for Floating Offshore Wind Turbines

Abstract

1. Introduction

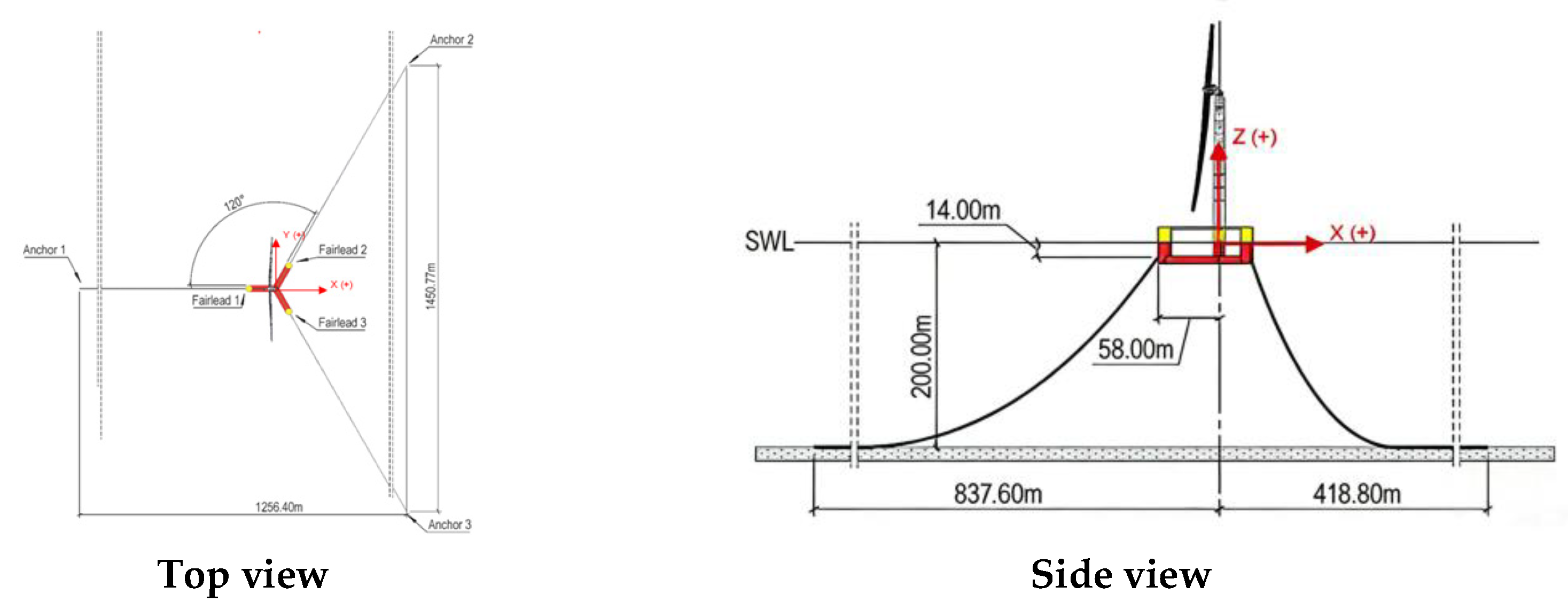

2. Mathematical and Numerical Models

2.1. Methodology Overview

2.2. Aerodynamic Load Theory

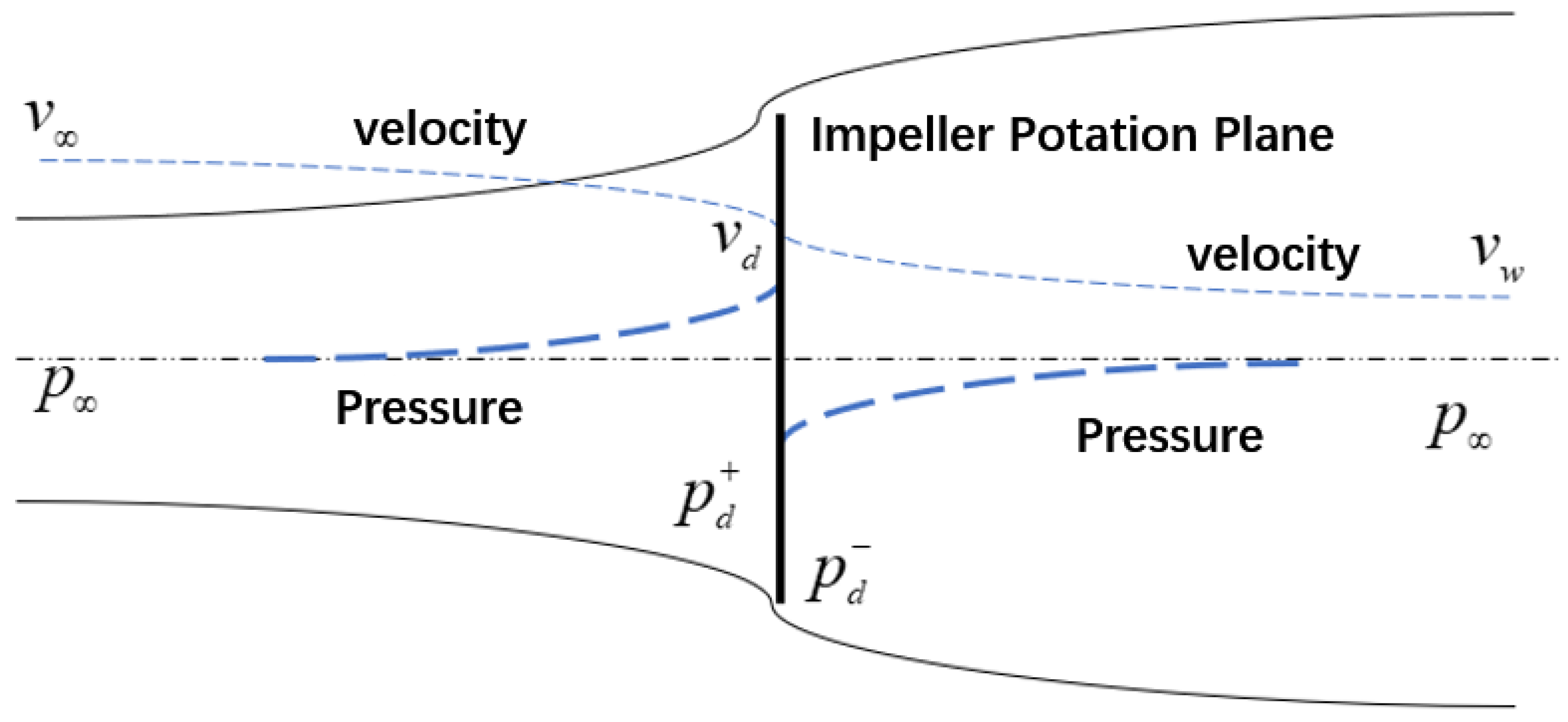

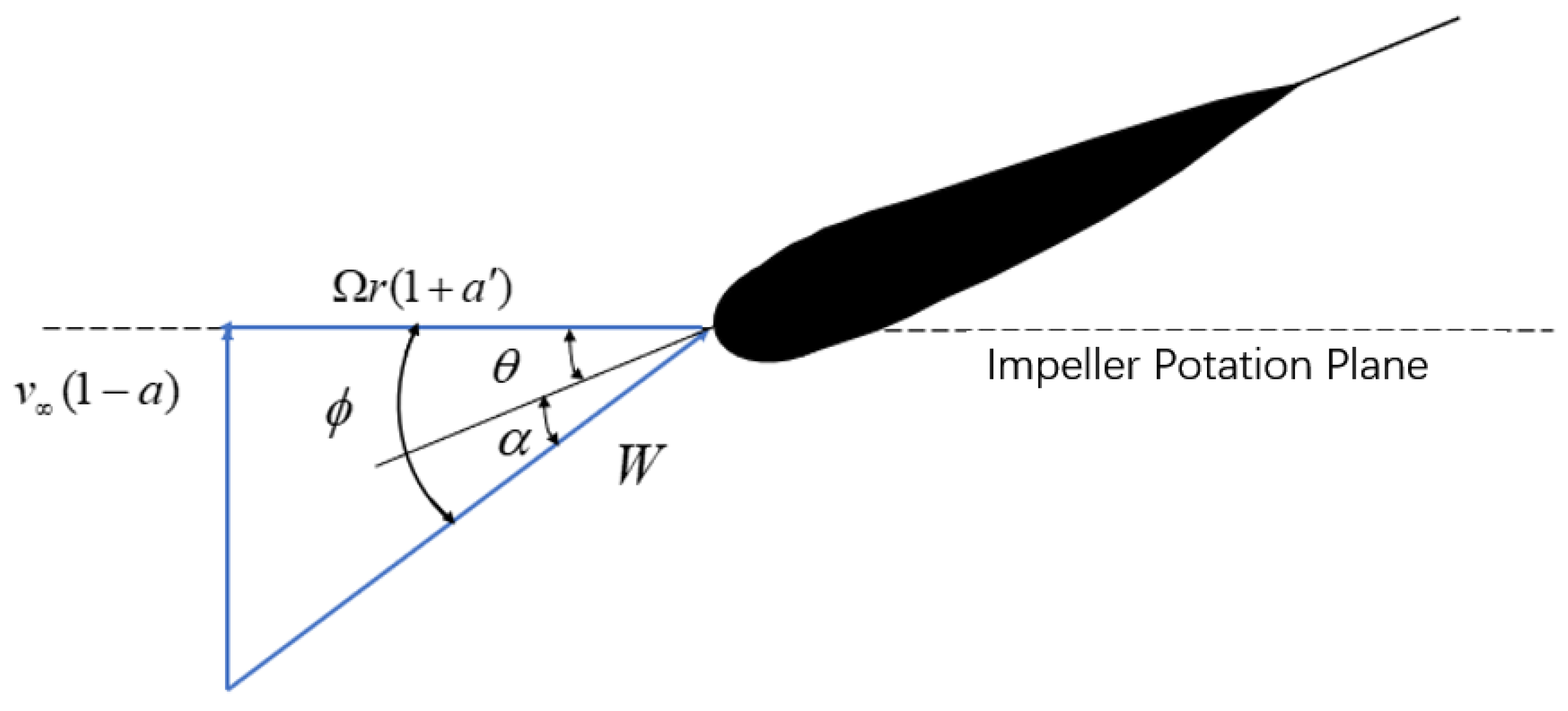

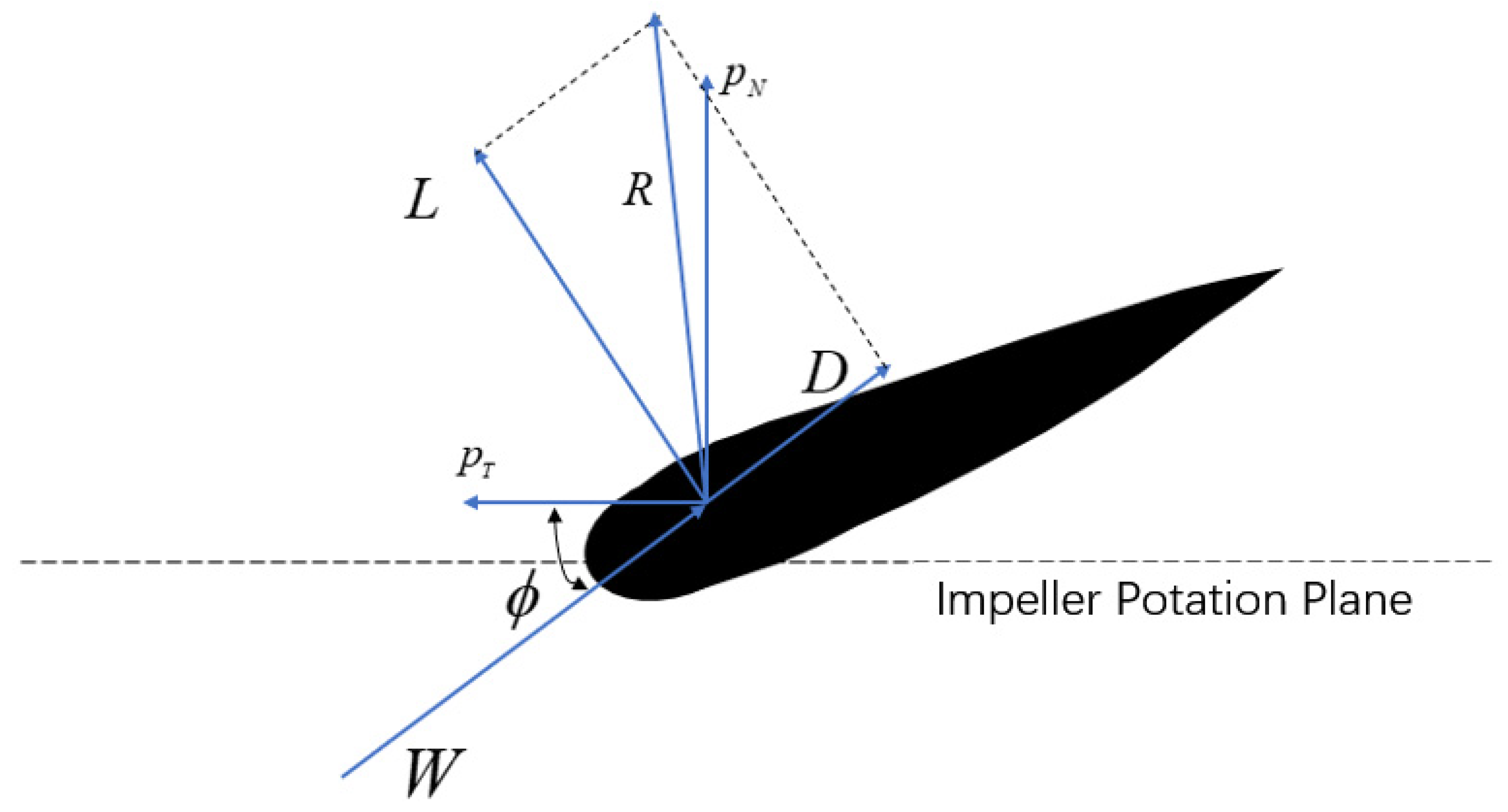

2.2.1. Blade Element Momentum Theory

2.2.2. Tip Stall Correction Model

2.3. Current and Wind Loads

2.4. Wave Force

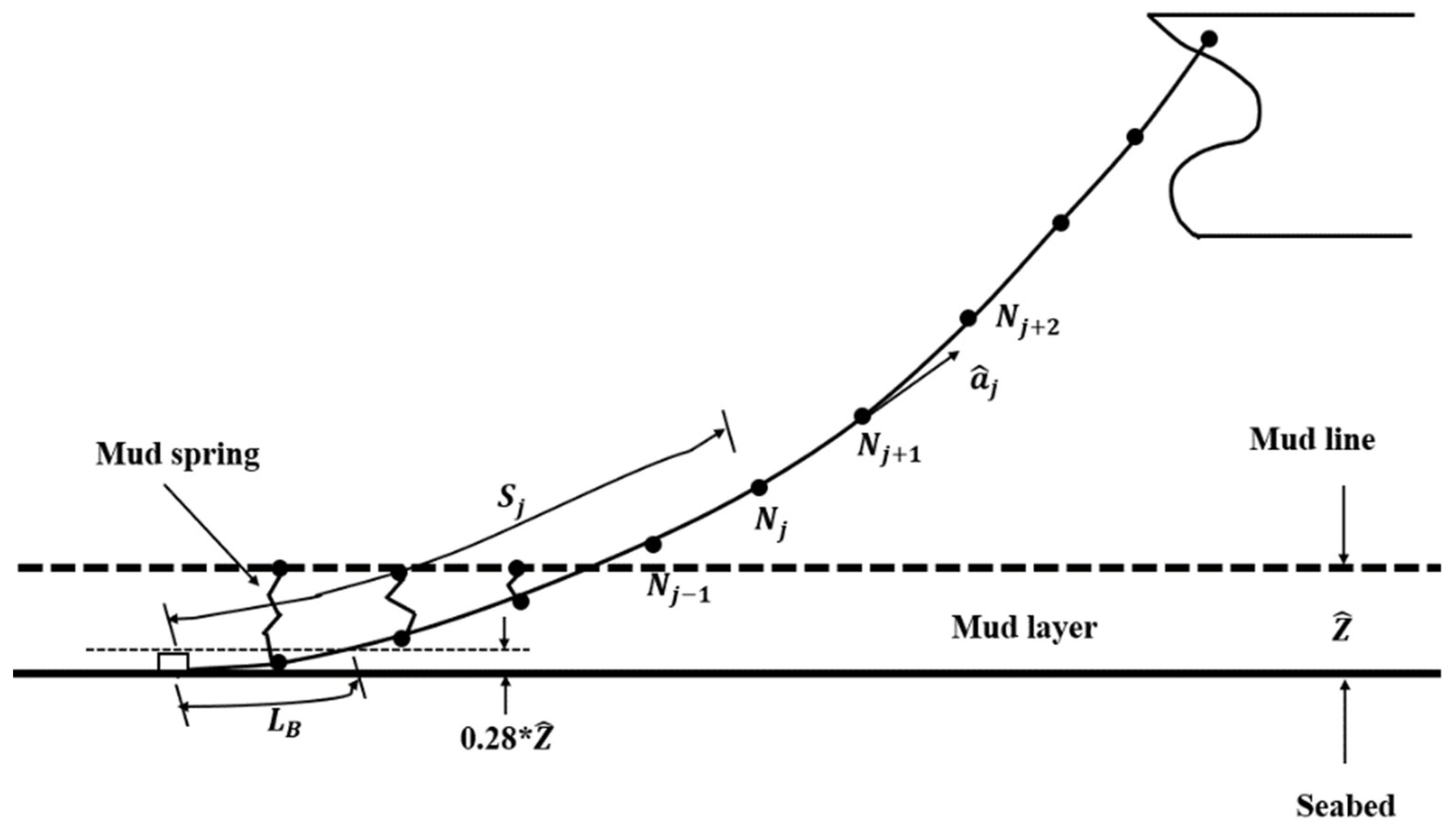

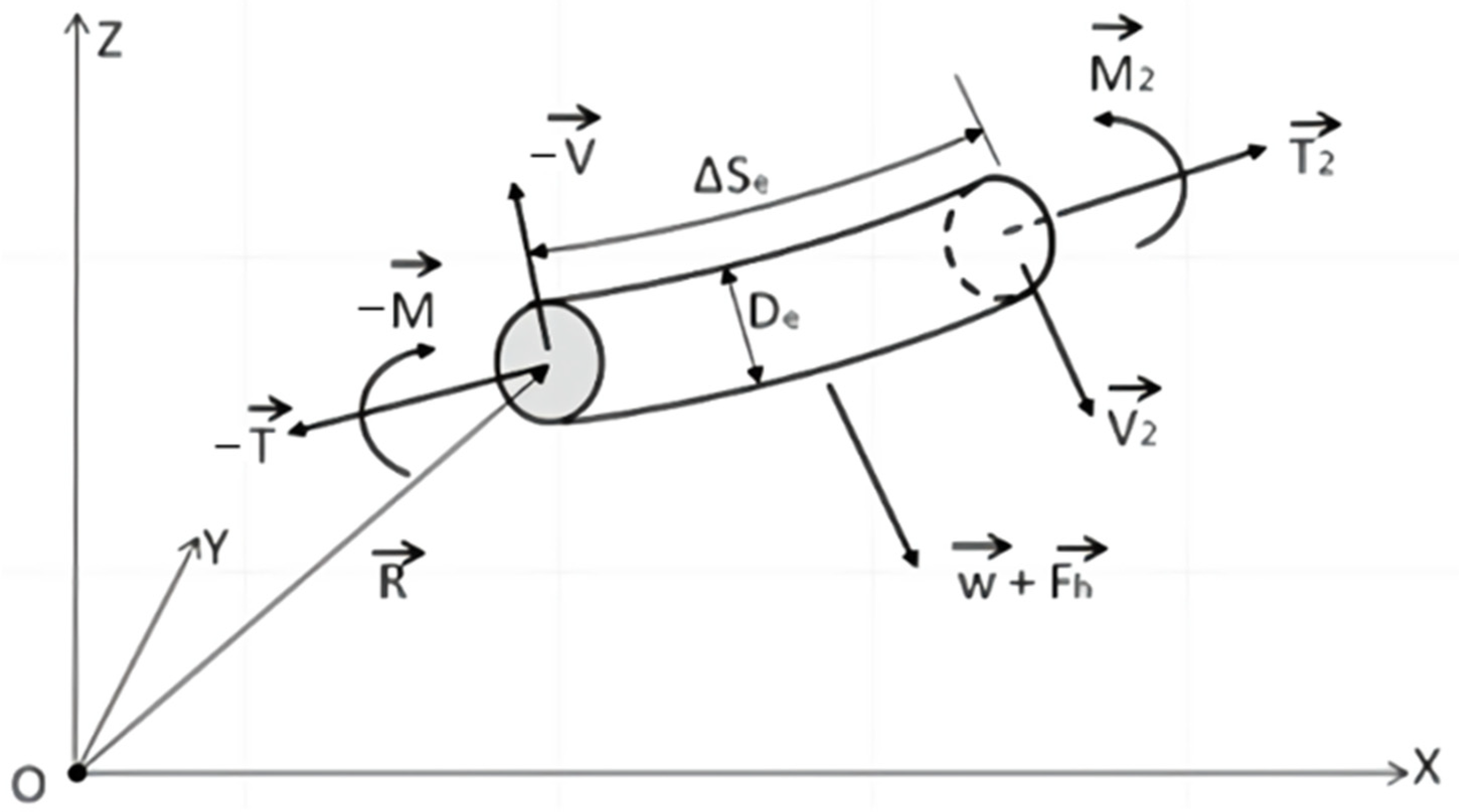

2.5. Mooring Force

2.6. Frequency-Domain Analysis

2.7. Time-Domain Model

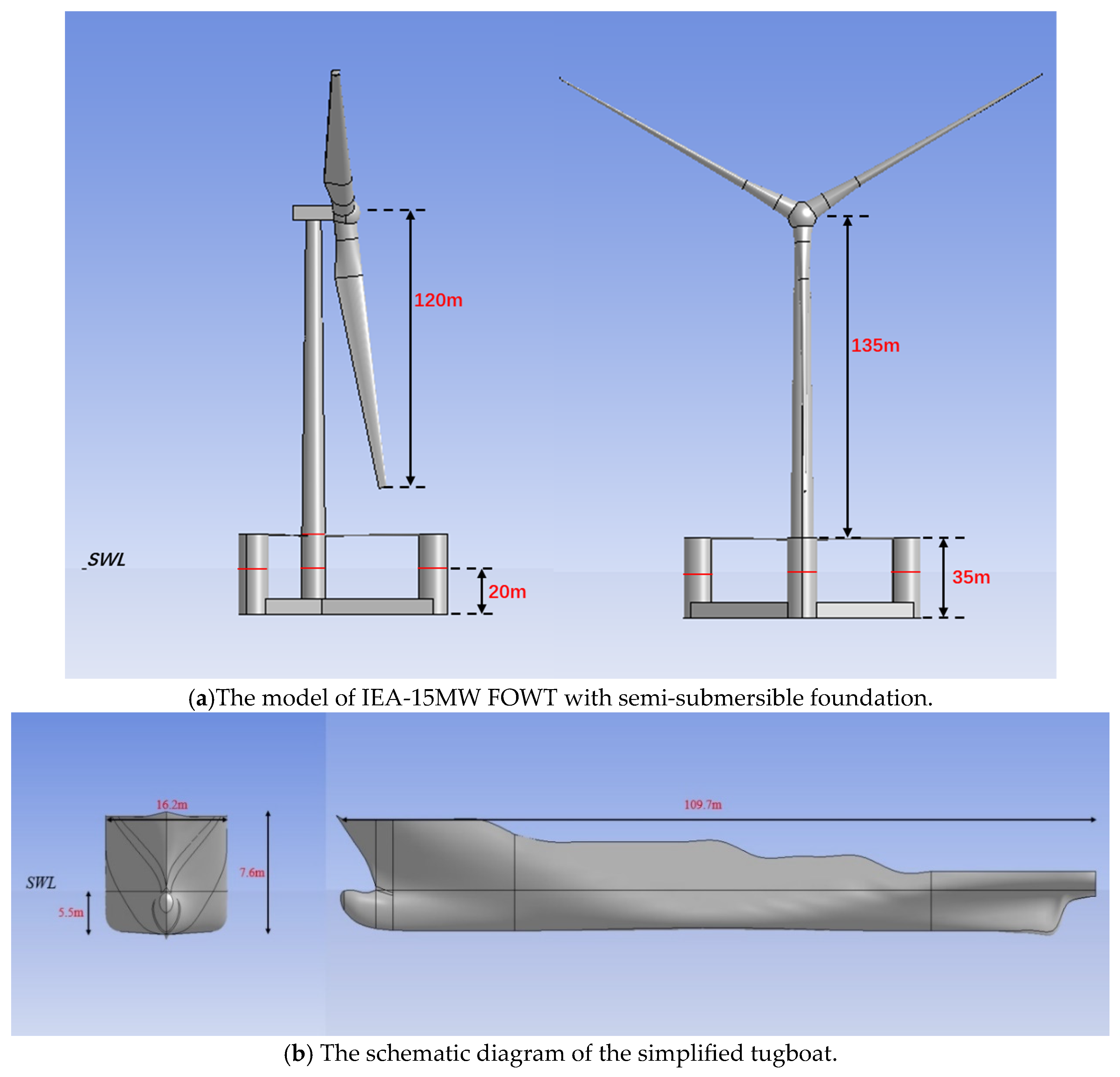

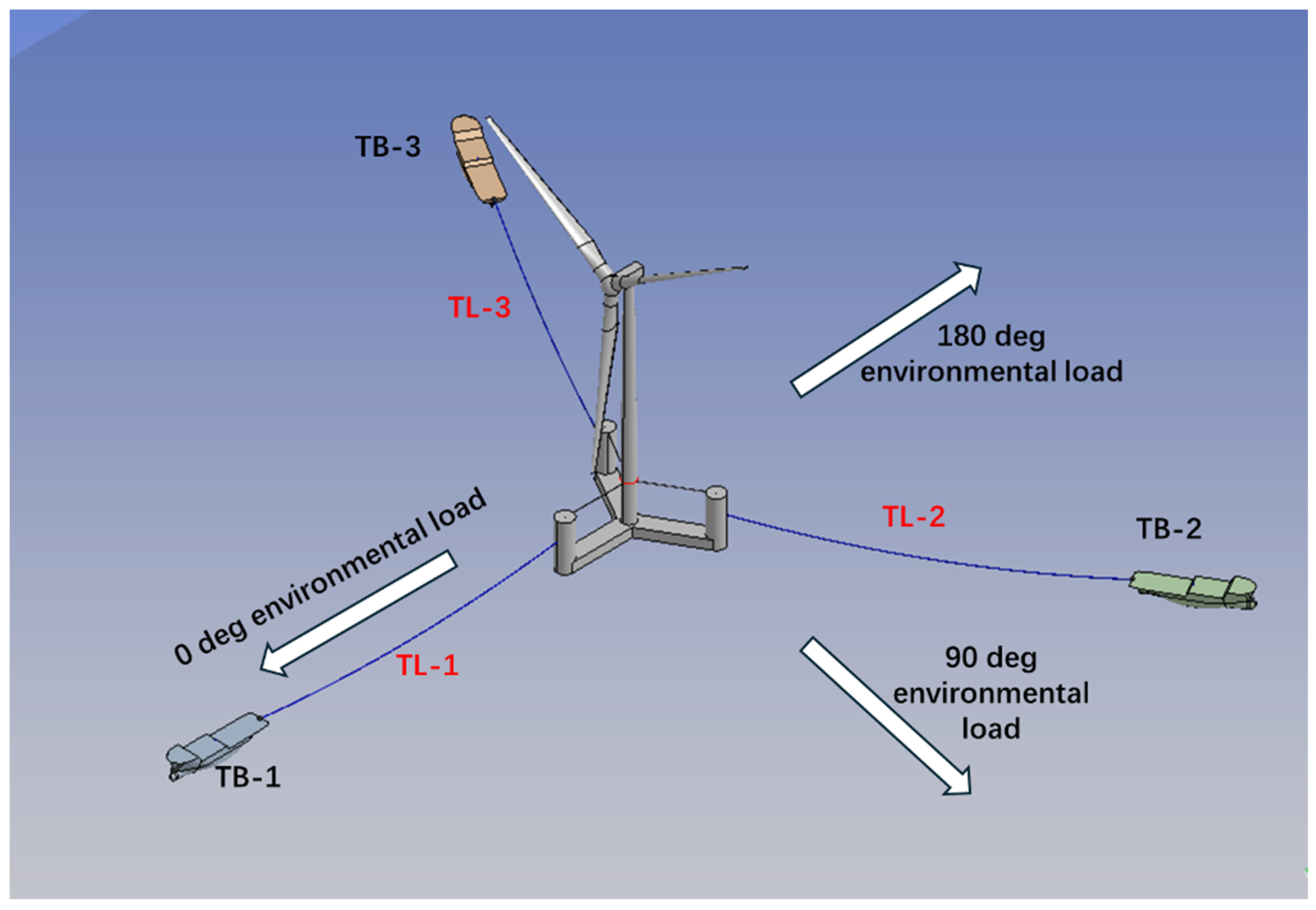

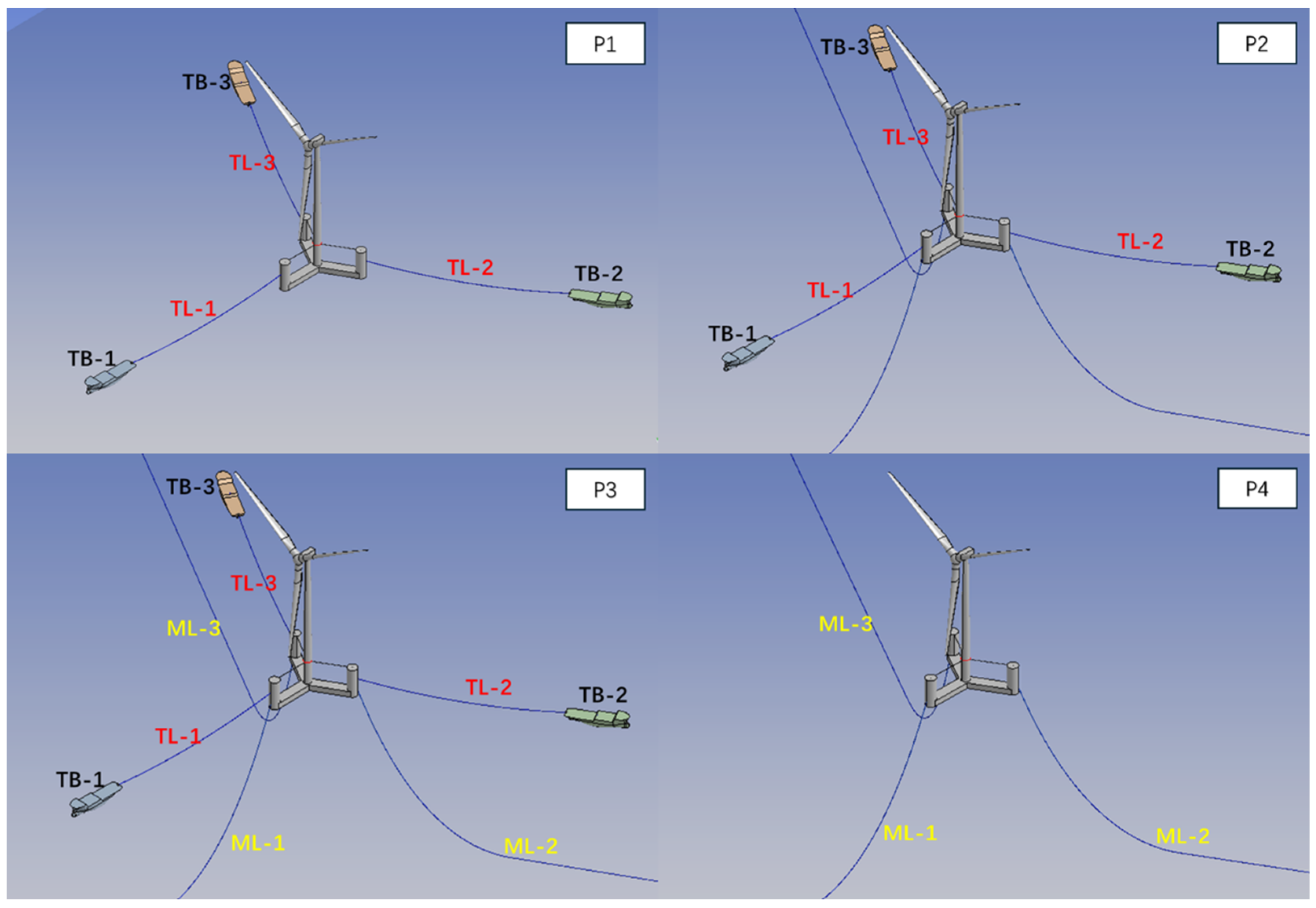

3. Description of the Systems

4. Results

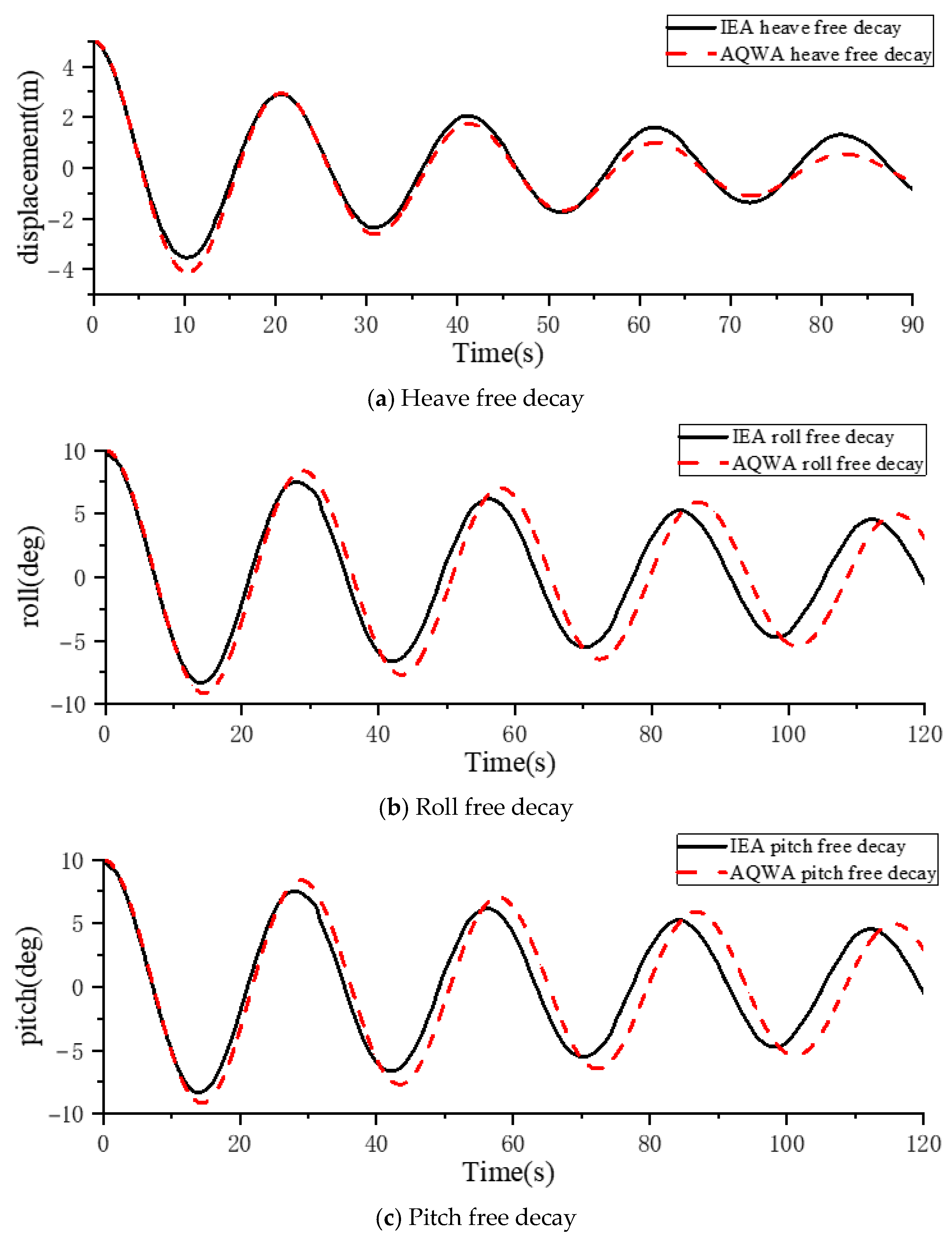

4.1. Verification of Model Damping Correction

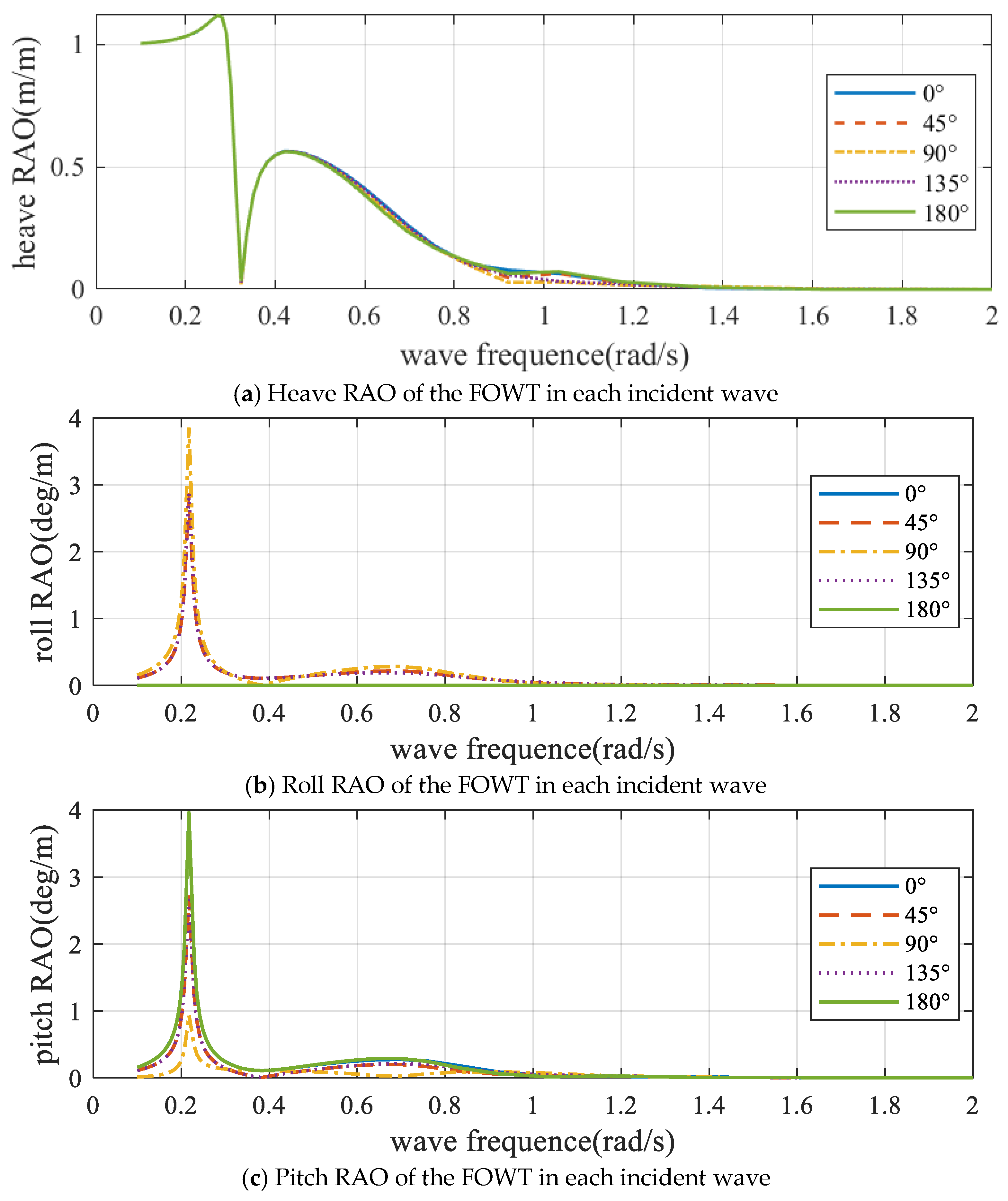

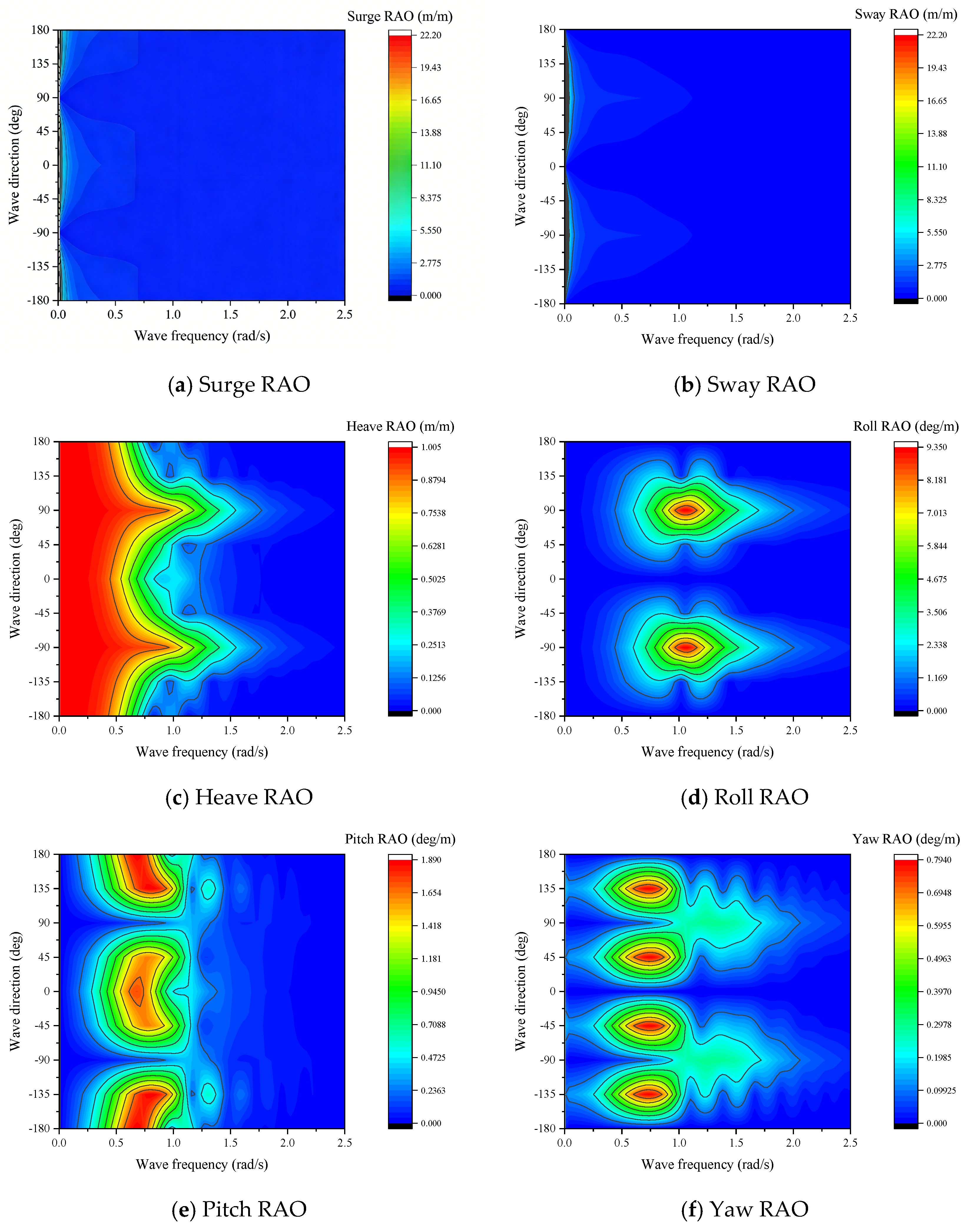

4.2. Frequency-Domain RAOs

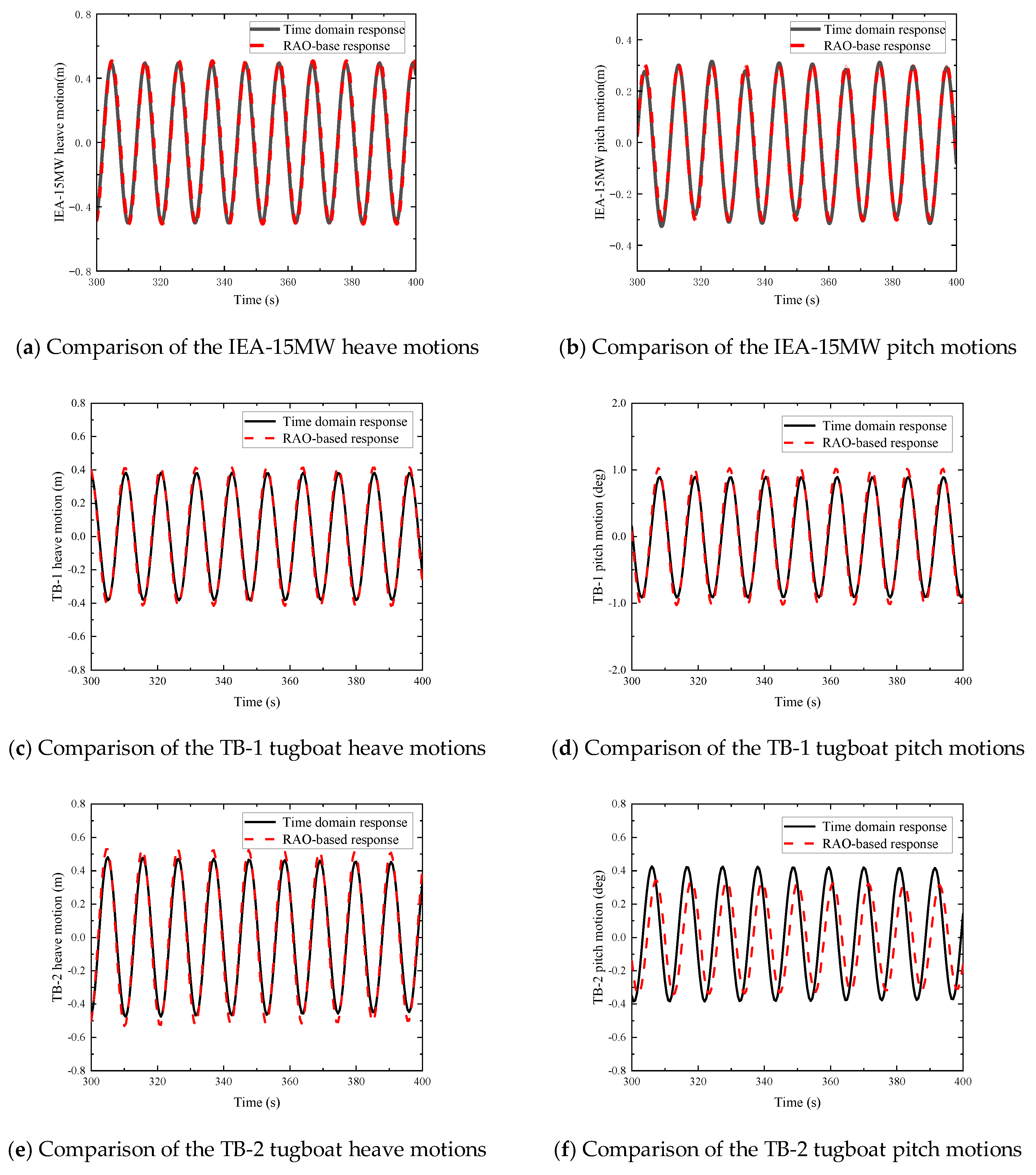

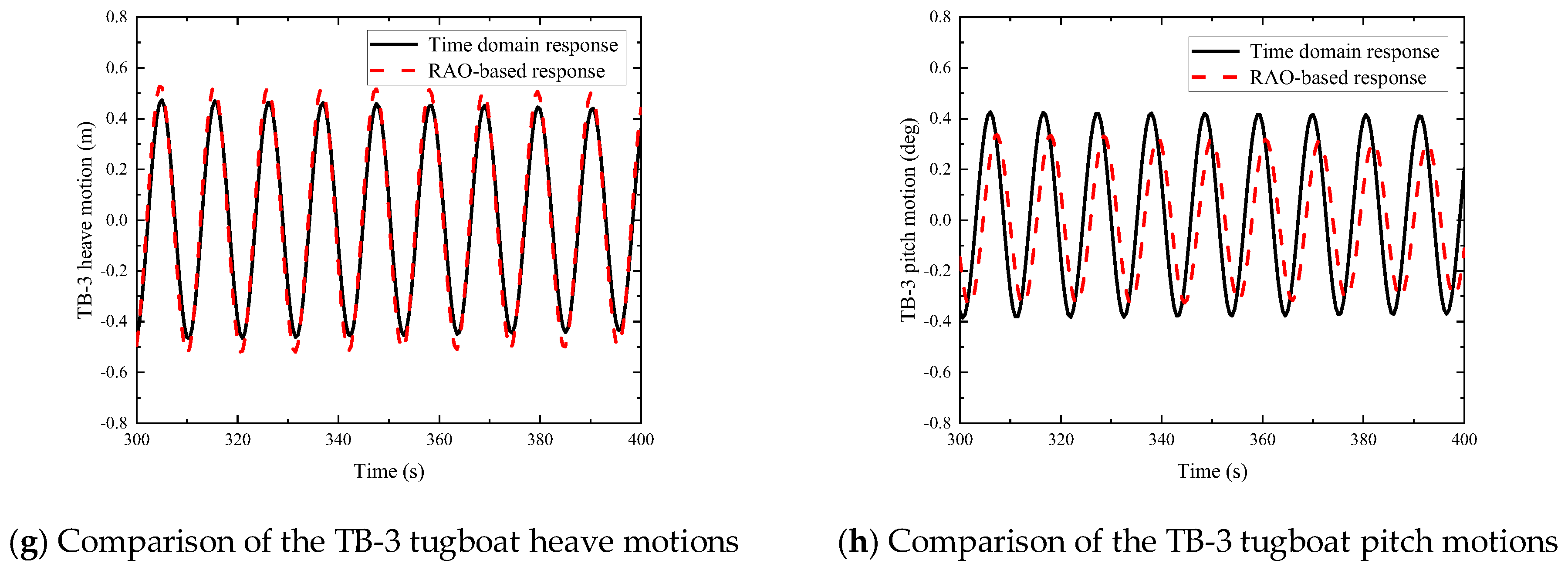

4.3. Time-Domain Verification

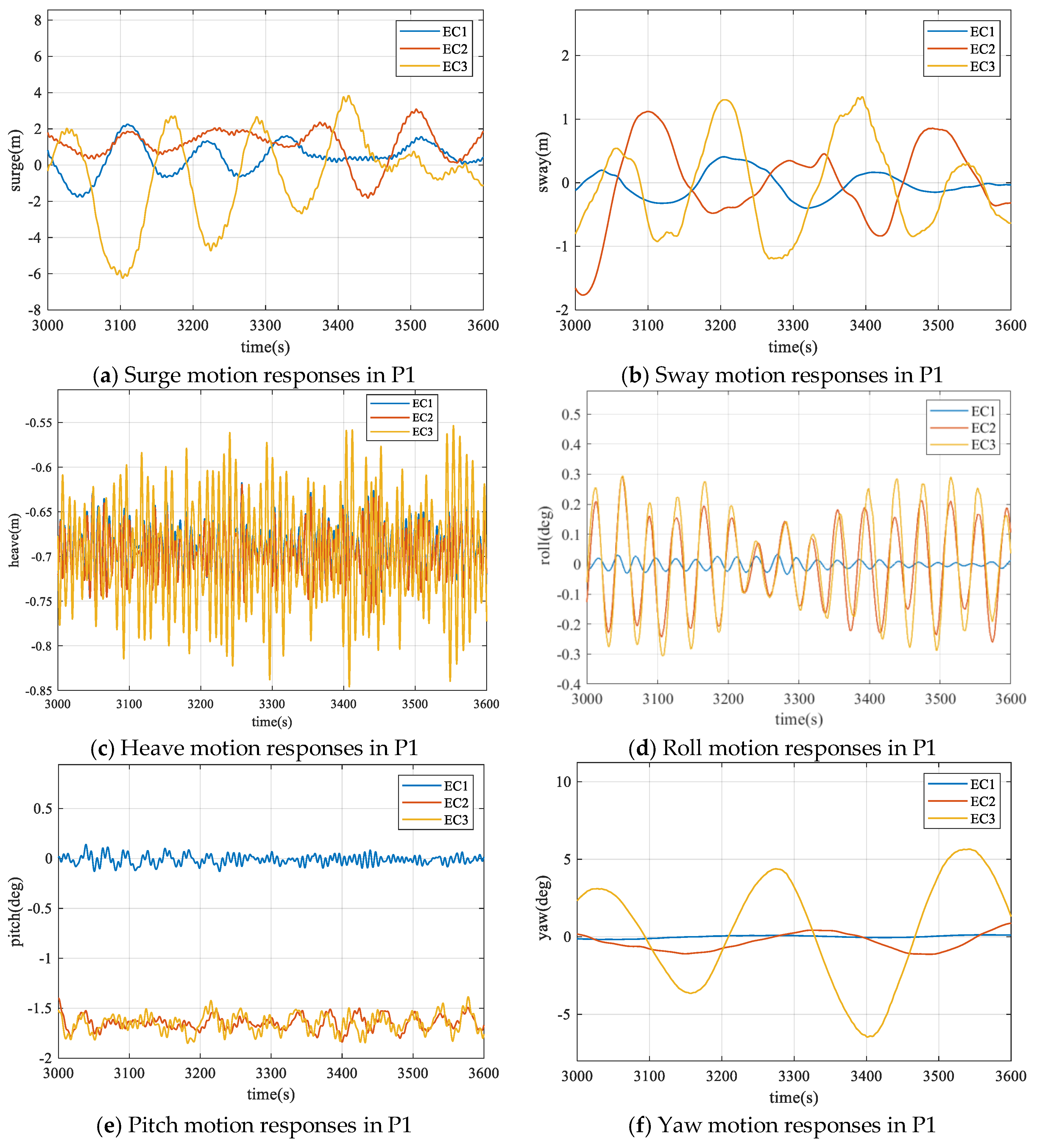

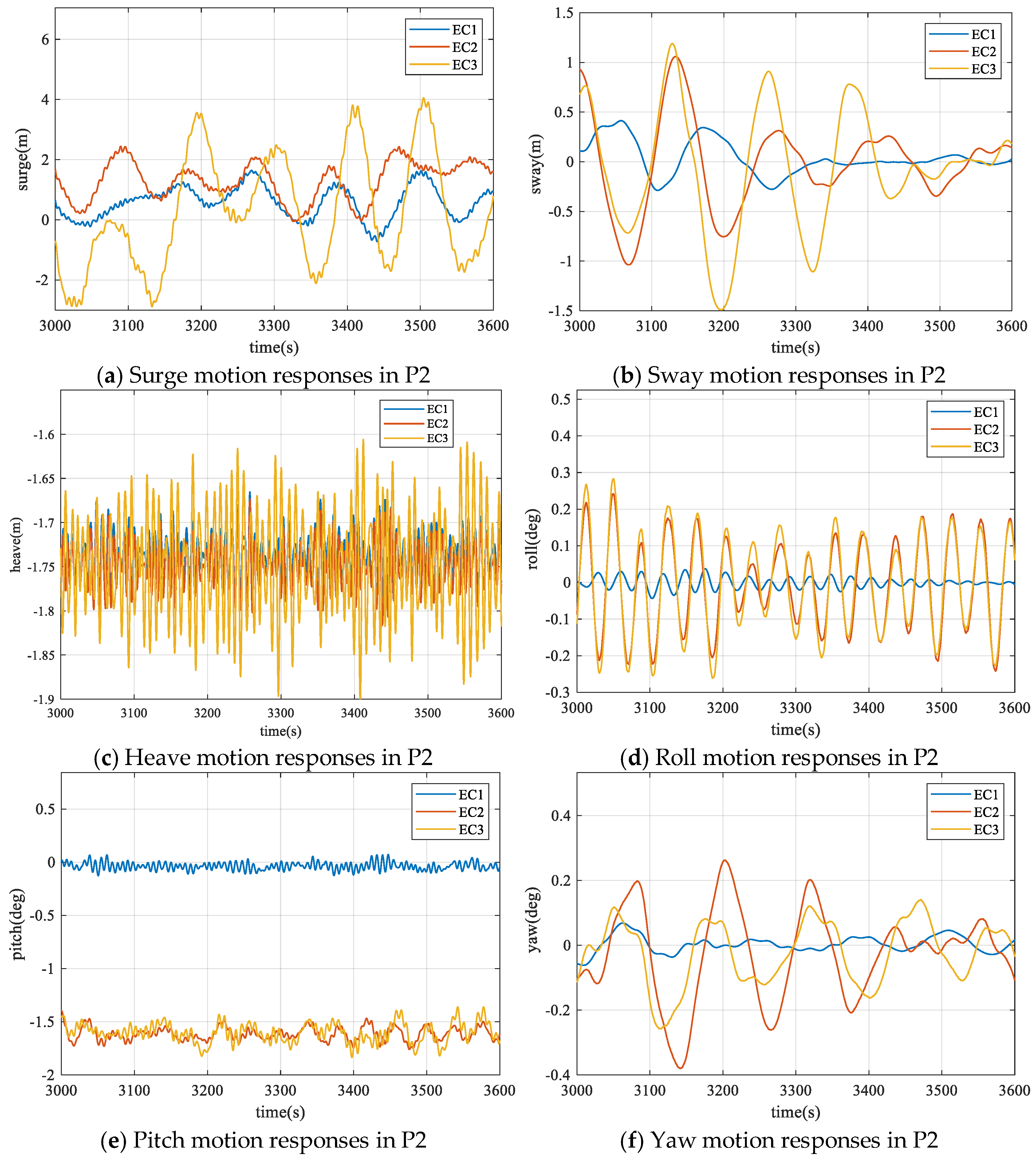

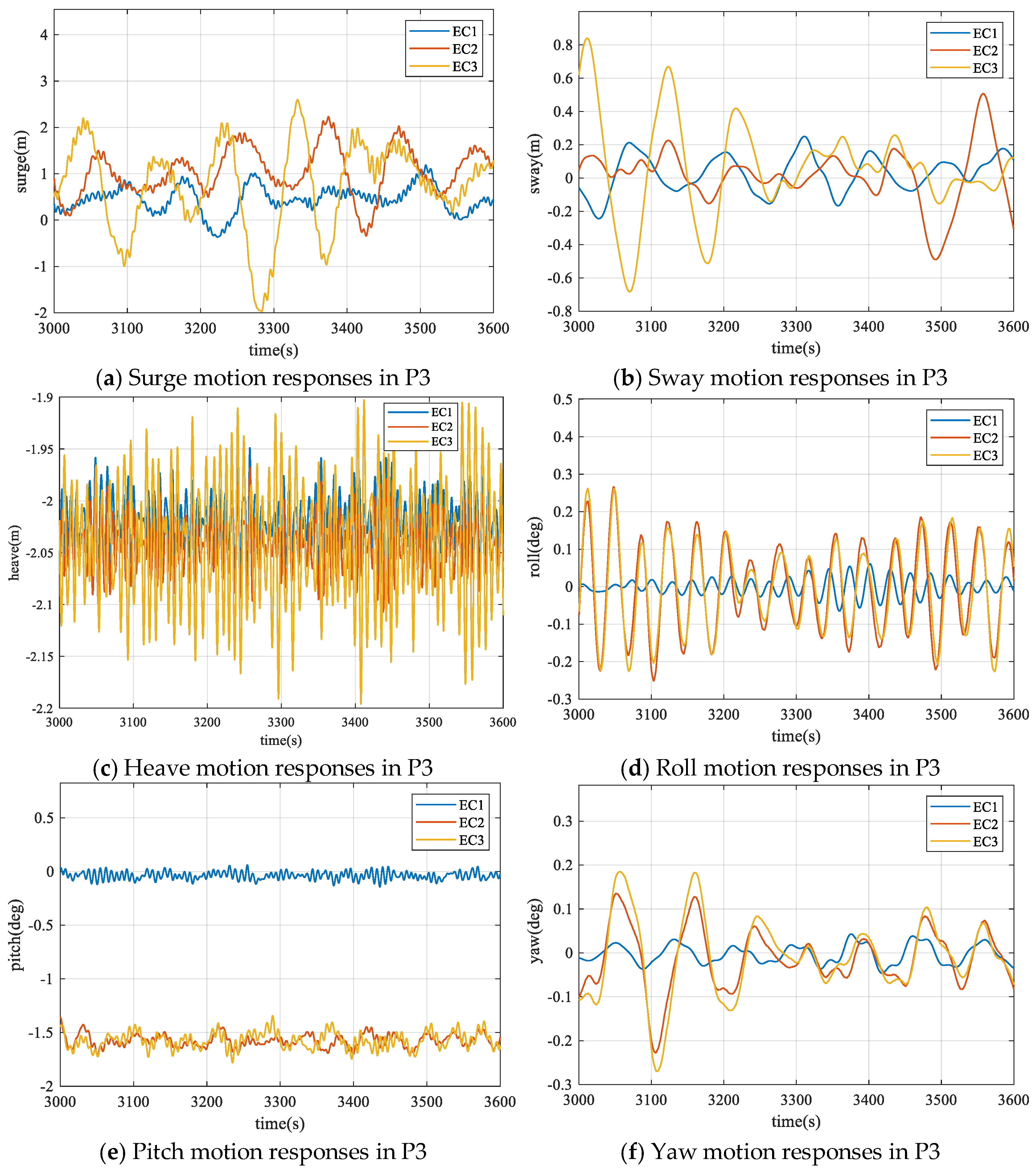

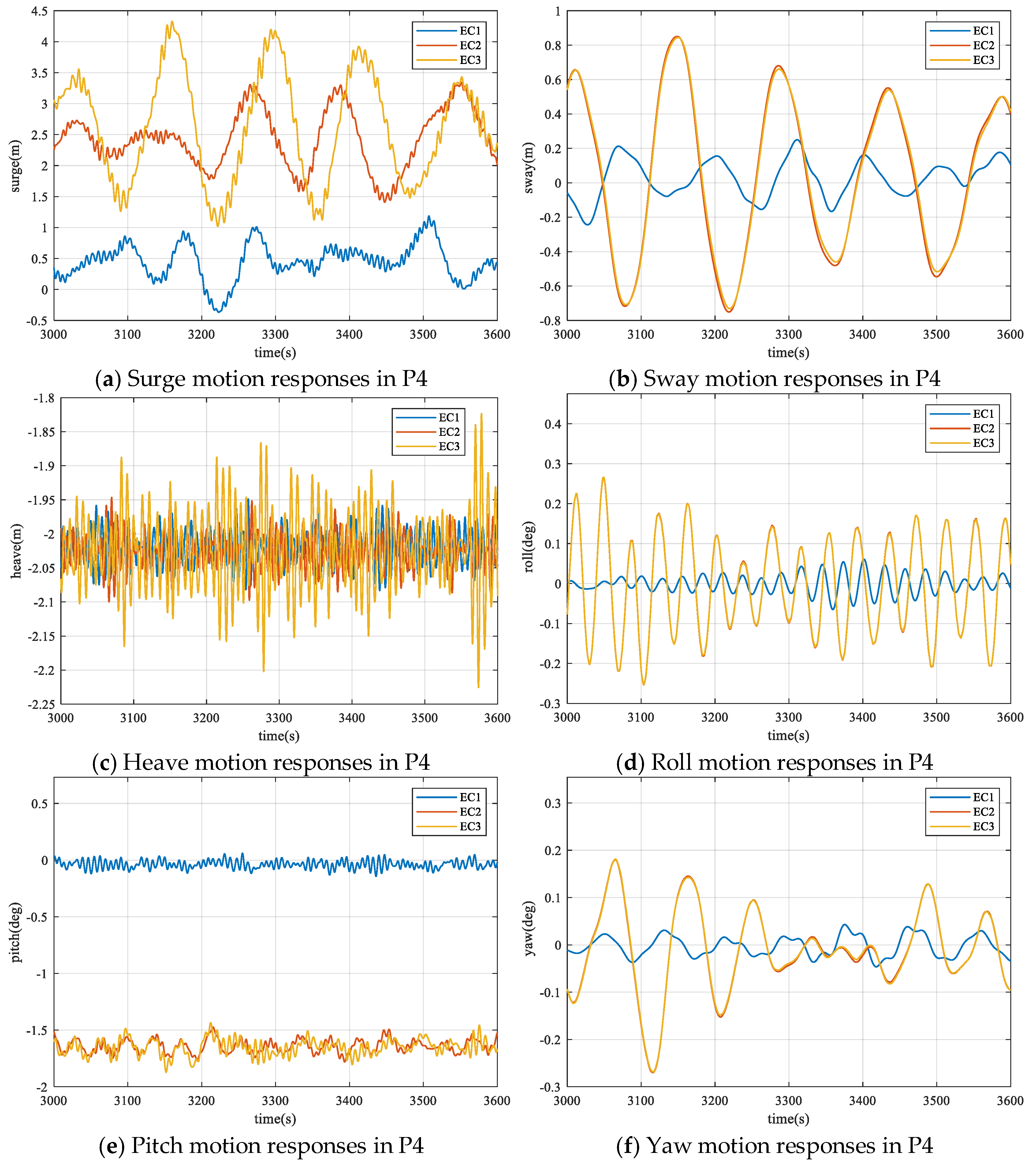

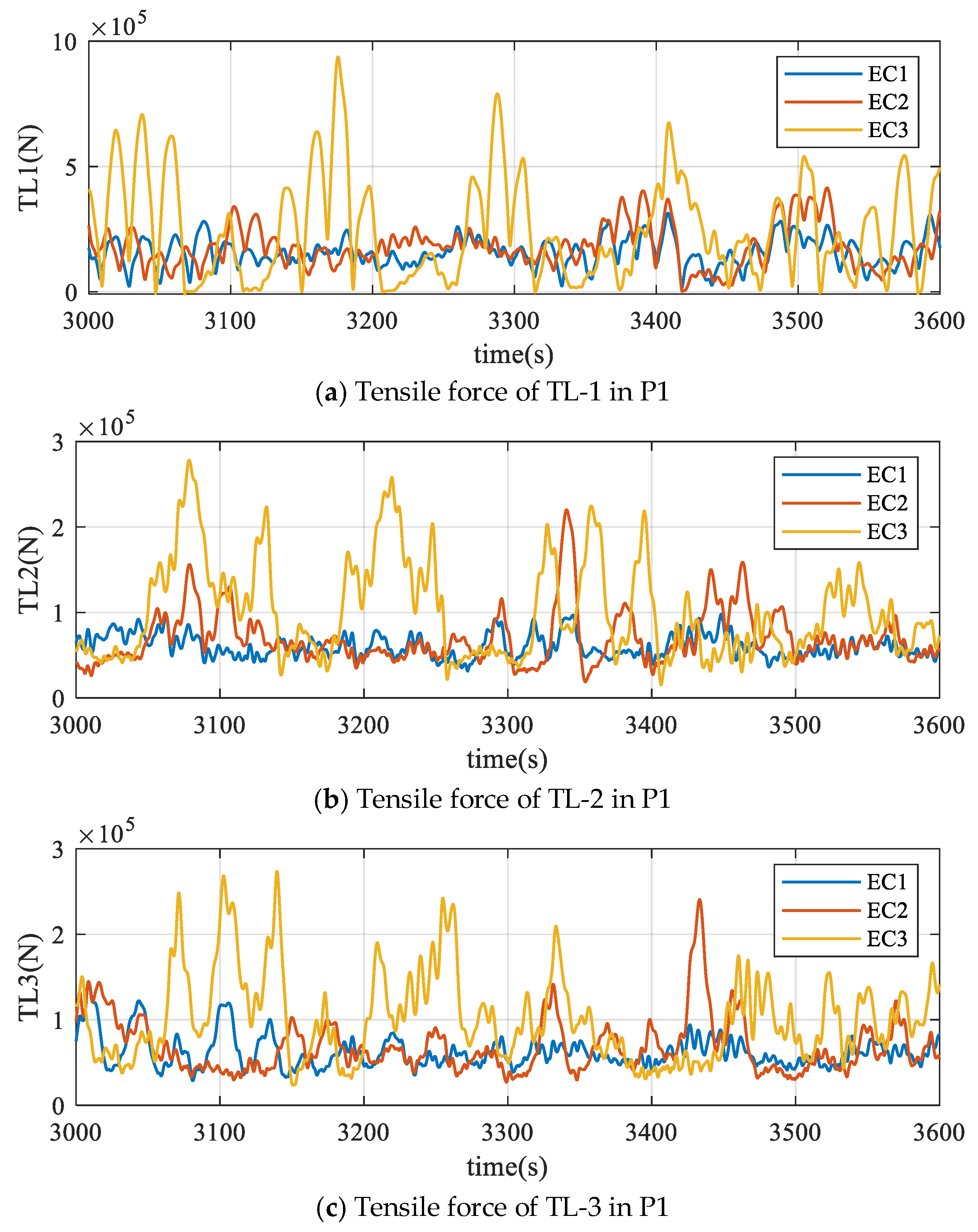

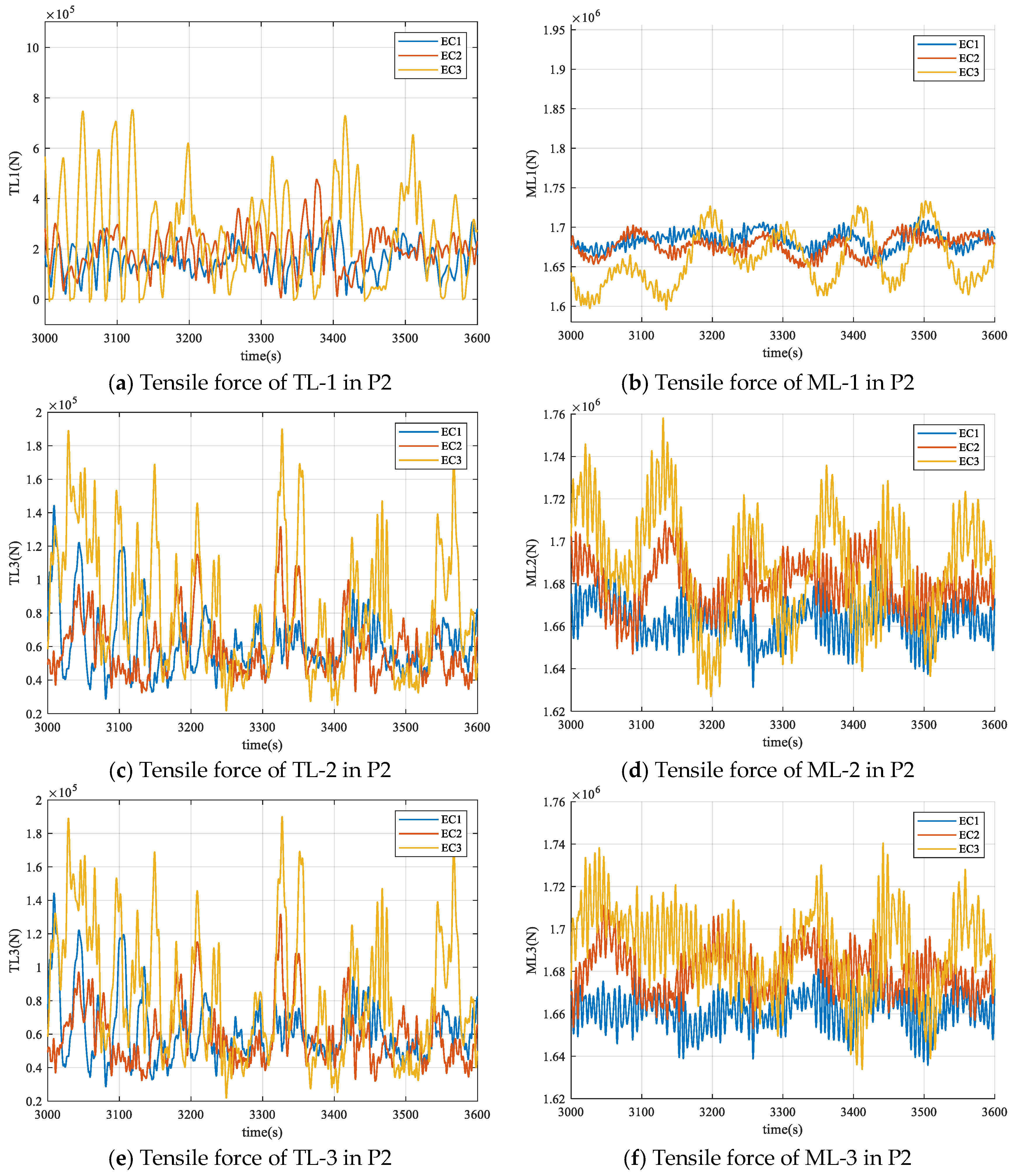

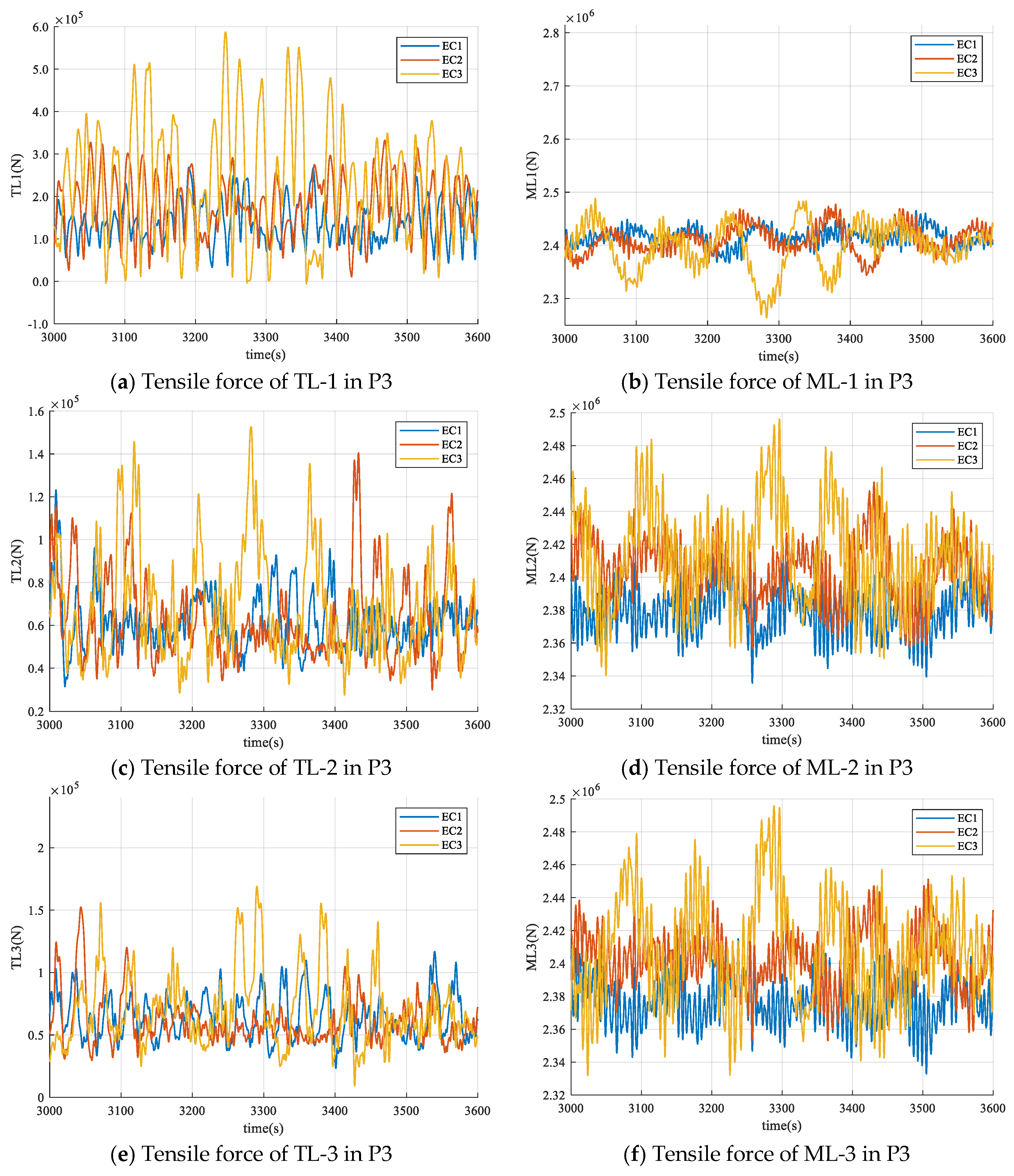

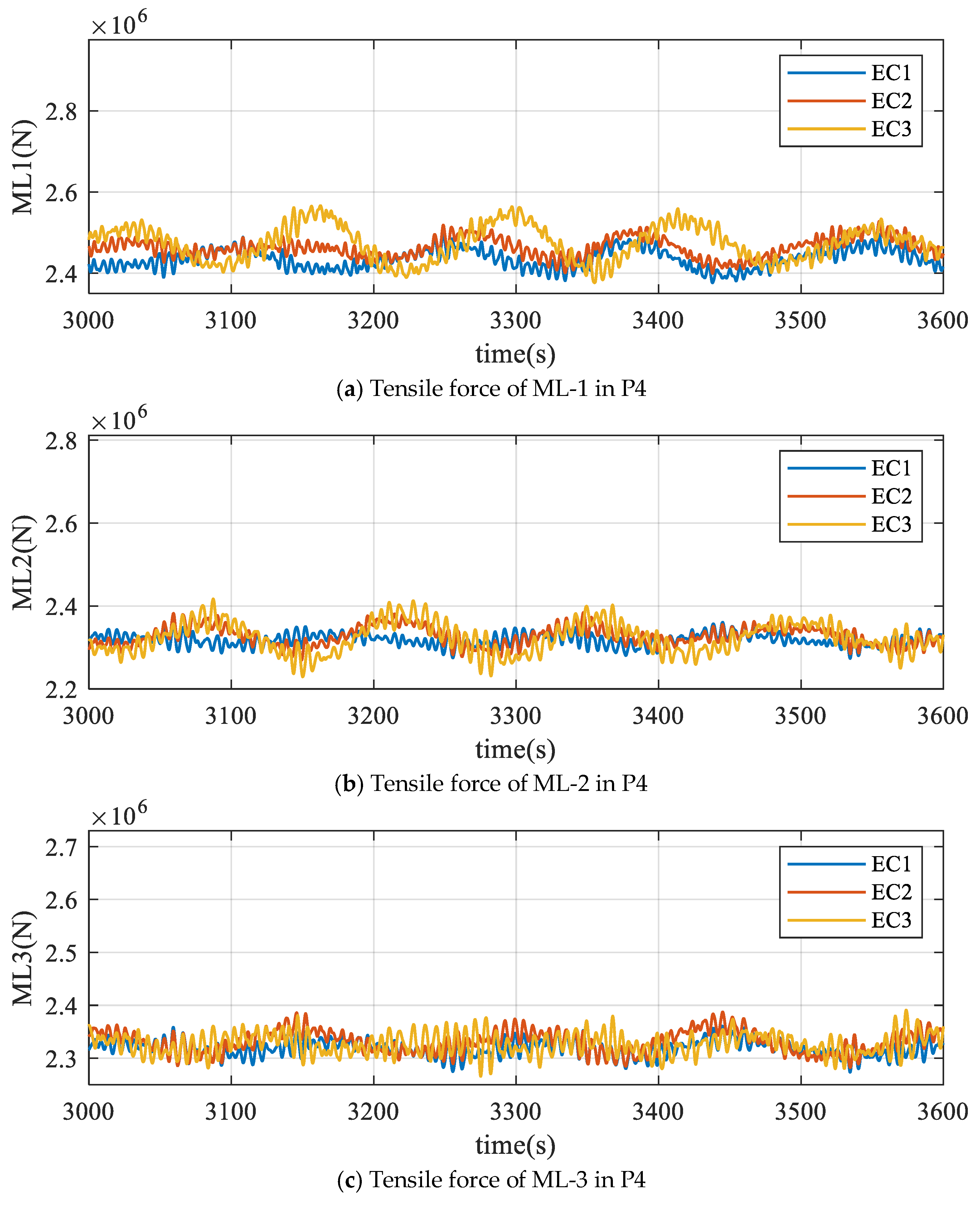

4.4. Coupled Analysis in Time Domain

5. Concluding Remarks

- This study introduced an innovative coupled simulation methodology by integrating the aerodynamic–hydrodynamic–elastic-mooring module FAST into the AQWA-based temporary positioning simulations. Through the F2A method, this approach enabled a fully coupled assessment of the platform’s motion responses and cable tension safety under multi-dynamic coupling, providing a numerical foundation for optimizing the design of temporary positioning and mooring installation schemes for FOWTs.

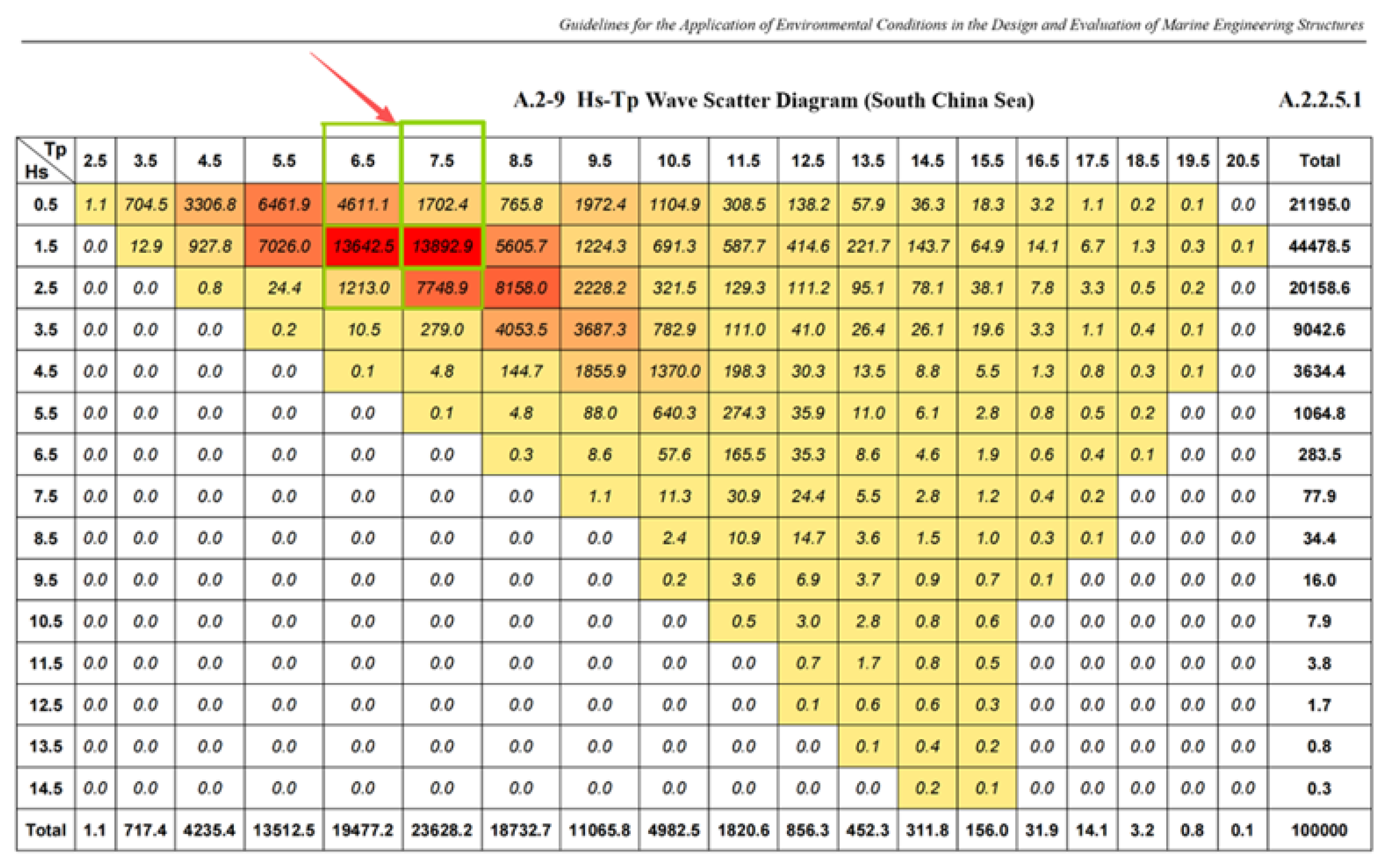

- Based on the wave scatter diagram of the South China Sea, simulations of the wind turbine’s temporary positioning were conducted under real marine environmental conditions with high occurrence probabilities. Compared with 1.5 m waves, 2.5 m waves induce significantly larger surge, sway, heave, and yaw responses of the FOWT. Roll and pitch responses are mainly affected by wind loads, which substantially shift the oscillation equilibrium position of the FOWT.

- A time-domain analysis of cable tension confirms that Stage P1 presents critical challenges. The upstream towing line (TL-1) experiences high tension with severe fluctuations. The restraining effect of towing cables on the temporary positioning of the wind turbine is considerably less effective than that of mooring chains, even in their untensioned state. Under severe sea conditions, the installation of mooring chains should be completed as soon as possible to avoid keeping the wind turbine at Stage P1.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Global Wind Energy Council (GWEC). Global Wind Report 2022. 2022. Available online: https://klimaatweb.nl/wp-content/uploads/po-assets/747206.pdf (accessed on 19 March 2024).

- Global Wind Energy Council (GWEC). Global Wind Report 2023. 2023. Available online: https://gwec.net/globalwindreport2023/ (accessed on 19 March 2024).

- Díaz, H.; Soares, C.G. Review of the current status, technology and future trends of offshore wind farms. Ocean Eng. 2020, 209, 107381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roddier, D.; Cermelli, C.; Aubault, A.; Peiffer, A. Summary and conclusions of the full life-cycle of the WindFloat FOWT prototype project. In International Conference on Offshore Mechanics and Arctic Engineering, Proceedings of the ASME 2017 36th International Conference on Ocean, Offshore and Arctic Engineering, Trondheim, Norway, 25–30 June 2017; American Society of Mechanical Engineers: New York, NY, USA, 2017; p. V009T12A048. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, K.-T.; Luo, Y.; Kwan, C.-T.T.; Wu, Y. Mooring System Engineering for Offshore Structures; Gulf Professional Publishing: Houston, TX, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Villa-Caro, R.; Carral, J.C.; Fraguela, J.Á.; López, M.; Carral, L. A review of ship mooring systems. Brodogr. Int. J. Nav. Archit. Ocean Eng. Res. Dev. 2018, 69, 123–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, J.; Ringwood, J.V. Mathematical modelling of mooring systems for wave energy converters—A review. Energies 2017, 10, 666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brommundt, M.; Krause, L.; Merz, K.; Muskulus, M. Mooring system optimization for floating wind turbines using frequency domain analysis. Energy Procedia 2012, 24, 289–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masciola, M.; Robertson, A.; Jonkman, J.; Coulling, A.; Goupee, A. Assessment of the importance of mooring dynamics on the global response of the DeepCwind floating semisubmersible offshore wind turbine. In Proceedings of the 23rd International Offshore and Polar Engineering Conference, Anchorage, AK, USA, 30 June–4 July 2013; ISOPE: Mountain View, CA, USA, 2013; p. ISOPE-I-13-129. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Y. Analysis on a New Type of Fully Submerged Floating Foundation and the Installation Technology of the Whole Wind Turbine System. Master’s Thesis, Tianjin University, Tianjin, China, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Antonutti, R.; Peyrard, C.; Incecik, A.; Ingram, D.; Johanning, L. Dynamic mooring simulation with Code_Aster with application to a floating wind turbine. Ocean Eng. 2018, 151, 366–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, K.; Gao, Z.; Moan, T. Effect of hydrodynamic load modelling on the response of floating wind turbines and its mooring system in small water depths. In Proceedings of the EERA DeepWind’2018, 15th Deep Sea Offshore Wind R&D Conference, Trondheim, Norway, 17–19 January 2018; Journal of Physics: Conference Series; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2018; p. 012006. [Google Scholar]

- Pham, H.-D.; Cartraud, P.; Schoefs, F.; Soulard, T.; Berhault, C. Dynamic modeling of nylon mooring lines for a floating wind turbine. Appl. Ocean Res. 2019, 87, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qingquan, L.; Nianxin, R.; Daocheng, Z. Dynamic Analysis of the Removal Process of A Semi-submersible Wind Turbine Platform. Nat. Sci. Hainan Univ. 2020, 38, 277–282. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, K.; Larsen, K.; Shao, Y.; Zhang, M.; Gao, Z.; Moan, T. Design and comparative analysis of alternative mooring systems for floating wind turbines in shallow water with emphasis on ultimate limit state design. Ocean Eng. 2021, 219, 108377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallak, T.; Soares, C.G.; Sainz, O.; Hernández, S.; Arévalo, A. Time domain analysis of the WIND-bos SPAR in regular waves. In Trends in Renewable Energies Offshore; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2022; pp. 559–566. [Google Scholar]

- Hallak, T.S.; Guedes Soares, C.; Sainz, O.; Hernández, S.; Arévalo, A. Hydrodynamic analysis of the WIND-bos spar floating offshore wind turbine. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2022, 10, 1824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, R.-Y.; Chuang, T.-C.; Zhao, C.; Johanning, L. Dynamic response of an offshore floating wind turbine at accidental limit states—Mooring failure event. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, R. Research on Time-domain Coupling Dynamic Response of Single Point Mooring System Installation. Master’s Thesis, Harbin Engineering University, Harbin, China, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Qiao, D.; Li, H.; Liang, H.; Wang, B.; Zhang, W.; Ou, J. Evaluation of the positioning capability of a novel concept design of dynamic positioning-assisted mooring systems for floating offshore wind turbines. Ocean Eng. 2024, 299, 117286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, C.; Viscelli, A.; Dagher, H.; Goupee, A.; Gaertner, E.; Abbas, N.; Hall, M.; Barter, G. Definition of the UMaine VolturnUS-S Reference Platform Developed for the IEA Wind 15-Megawatt Offshore Reference Wind Turbine; National Renewable Energy Lab. (NREL): Golden, CO, USA; University of Maine: Orono, ME, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- CCS. Guidelines for Towage at Sea; CCS: Beijing, China, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Iijma, K.; Wang, X.; Sielski, R.; Rizzuto, E.; Ogawa, Y.; de Hauteclocque, G.; Fang, C.-C.; Fonseca, N.; Johannessen, T.B.; Mumm, H. Measurements and theoretical methods. Uncertainties in load estimations shall be highlighted. The committee is encouraged to cooperate with the corresponding ITTC committee. In Proceedings of the 20th International Ship and Offshore Structures Congress (ISSC 2018), Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 9–14 September 2018; IOS Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; Volume 3, p. 13. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, J.; Chen, S.; Zhang, B. Analysis of Ship Surf-Riding/Broaching Motion Considering the Influence of Wave Drift Force. In Advances in Machinery, Materials Science and Engineering Application X; IOS Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2024; pp. 460–466. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y. Discussion on the selection of main tugboat for towing drilling equipment. China Offshore Oil Gas 1995, 7, 20–26. [Google Scholar]

- Trubat, P.; Molins, C.; Gironella, X. Wave hydrodynamic forces over mooring lines on floating offshore wind turbines. Ocean Eng. 2020, 195, 106730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triantafyllou, M.S. Preliminary design of mooring systems. J. Ship Res. 1982, 26, 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benassai, G.; Campanile, A.; Piscopo, V.; Scamardella, A. Optimization of mooring systems for floating offshore wind turbines. Coast. Eng. J. 2015, 57, 1550021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altuzarra, J.; Herrera, A.; Matías, O.; Urbano, J.; Romero, C.; Wang, S.; Guedes Soares, C. Mooring system transport and installation logistics for a floating offshore wind farm in Lannion, France. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2022, 10, 1354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campanile, A.; Piscopo, V.; Scamardella, A. Mooring design and selection for floating offshore wind turbines on intermediate and deep water depths. Ocean Eng. 2018, 148, 349–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tom, N.M. Design and Control of a Floating Wave-Energy Converter Utilizing a Permanent Magnet Linear Generator. Doctoral Dissertation, University of California, Berkeley, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, K.; Xie, G.; Zhou, B. Type selection and hydrodynamic performance analysis of wave energy converters. J. Harbin Eng. Univ. 2021, 42, 8–14. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, M.; Zou, M.; Zhu, L. Frequency-domain response analysis of adjacent multiple floaters with flexible connections. J. Ship Mech. 2018, 22. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, M.; Zou, M.; Zhu, L.; Ouyang, M.; Liang, Q.; Zhao, W. A fully coupled time domain model capturing nonlinear dynamics of float-over deck installation. Ocean Eng. 2024, 293, 116721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Li, B.; Hu, Z.; Deng, J.; Xiao, P.; Chen, M. Research on size optimization of wave energy converters based on a floating wind-wave combined power generation platform. Energies 2022, 15, 8681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Sævik, S.; Leira, B.J. A sensitivity study of vessel hydrodynamic model parameters. In Proceedings of the ASME 2020 39th International Conference on Ocean, Offshore Mechanics and Arctic Engineering, Virtual, 3–7 August 2020; American Society of Mechanical Engineers: New York, NY, USA, 2020; p. V001T01A039. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, N.; Li, Y.; Ou, J. Coupled wind-wave time domain analysis of floating offshore wind turbine based on Computational Fluid Dynamics method. J. Renew. Sustain. Energy 2014, 6, 023106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, T.; Chen, N.-Z. Time-domain fatigue assessment for blade root bolts of floating offshore wind turbine (FOWT). Ocean Eng. 2022, 262, 112201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallak, T.; Kamarlouei, M.; Gaspar, J.; Soares, C.G. Time domain analysis of a conical point-absorber moving around a hinge. In Trends in Maritime Technology and Engineering; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2022; pp. 401–409. [Google Scholar]

- Cummins, W. The impulse response function and ship motions. In Proceedings of the Ymposium on Snip Theory Institut für Schiffbau Deruniversität Hamburg, Hamburg, Germany, 25–27 January 1962. [Google Scholar]

- Ogilvie, T.F. Recent progress toward the understanding and prediction of ship motions. In Proceedings of the Fifth Symposium on Naval Hydrodynamics, Bergen, Norway, 10–12 September 1964; pp. 3–79. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, Y.; Chen, M.; Yuan, Z.; Jiang, X.; Yu, N.; Li, T.; Choo, Y.S. Advancing Floating Offshore Wind Turbine Construction from the Perspective of Wet Towing Using a Tugboat with Autonomous Control. Mar. Struct. 2026, 107, 103973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, T.; Yang, Y.; Yang, T.; Liu, S.; Guo, X.; Wang, H.; Liu, Z.; Chen, W.; Liang, C.; Long, K. Time-domain fatigue damage assessment for wind turbine tower bolts under yaw optimization control at offshore wind farm. Ocean Eng. 2024, 303, 117706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, M.; Chen, C.; Chen, M.; Xiao, P.; Ouyang, M.; Tang, Y.; Zhao, W.; Tian, X. Development of a coupled time-domain model for complexly moored multi-body system with application in catamaran float-over deck installation. Mar. Struct. 2025, 103, 103849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Chen, X.; Huang, G.; Chen, M.; Zhang, K.; Jiang, Y.; Li, T.; Tao, T.; Yang, Y. Dynamic analysis of multi-module floating photovoltaic platforms with composite mooring system by considering tidal variation and platform configuration. Ocean Eng. 2024, 312, 119243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roddier, D.; Cermelli, C.; Weinstein, A. WindFloat: A floating foundation for offshore wind turbines—Part I: Design basis and qualification process. In Proceedings of the ASME 2009 28th International Conference on Ocean, Offshore Mechanics and Arctic Engineering, Honolulu, HI, USA, 31 May–5 June 2009; pp. 845–853. [Google Scholar]

- Aubault, A.; Cermelli, C.; Roddier, D. WindFloat: A floating foundation for offshore wind turbines—Part III: Structural analysis. In Proceedings of the ASME 2009 28th International Conference on Ocean, Offshore Mechanics and Arctic Engineering, Honolulu, HI, USA, 31 May–5 June 2009; pp. 213–220. [Google Scholar]

- Cermelli, C.; Roddier, D.; Aubault, A. WindFloat: A floating foundation for offshore wind turbines—Part II: Hydrodynamics analysis. In Proceedings of the ASME 2009 28th International Conference on Ocean, Offshore Mechanics and Arctic Engineering, Honolulu, HI, USA, 31 May–5 June 2009; pp. 135–143. [Google Scholar]

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Rotor diameter (m) | 240 |

| Hub diameter (m) | 3.97 |

| Hub height (above waterline) (m) | 150 |

| Nacelle mass (t) | 675,175 |

| Tower height (m) | 135 |

| Tower mass (t) | 1483.41 |

| Bottom diameter of tower (m) | 10 |

| Top diameter of tower (m) | 6.5 |

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Distance between offset columns (m) | 102.13 |

| Diameter of column (m) | 12.5 |

| Diameter of cross braces between pontoons (m) | 0.9 |

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Total length (m) | 109.7 |

| Breadth (m) | 16.2 |

| Depth (m) | 7.6 |

| Design draft (m) | 5.5 |

| Square coefficient | 0.611 |

| Maximum towing force (kN) | 4000 |

| Item | FOWT | Tugboat-1 | Tugboat-2 | Tugboat-3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coordinates of center of mass (m) | (0, 0, −14.4) | (−333.65, 0, −3.5) (166.83, −288.96, −3.5) (166.83, 288.96, −3.5) | ||

| Designed displacement (m3) | 20,206 | 5379.97 | 5380.16 | 5379.69 |

| Ixx (kg.m2) | 4.396 × 1010 | 1.67 × 108 | 1.67 × 108 | 1.67 × 108 |

| Iyy (kg.m2) | 4.385 × 1010 | 3.5 × 109 | 3.5 × 109 | 3.5 × 109 |

| Izz (kg.m2) | 2.396 × 109 | 3.53 × 109 | 3.5 × 109 | 3.5 × 109 |

| Item | Value |

|---|---|

| Mass of unit length (kg/m) | 47.89 |

| Equivalent diameter (m) | 0.088 |

| Stiffness of catenary (towing cable) (kN) | 3.13 × 105 |

| Breaking force (kN) | 4.165 × 103 |

| Length of TL-1/2/3 (m) | 240/240/240 |

| Coordinates of WFXLD-1/2/3 (m) | (−58, 0, 1) (29, −50.23/50.23, 1) |

| Coordinates of TB-1/2/3XLD-1 (m) | (−298, 0, 1), (149, −257.8/257.8, 1) |

| Coordinates of TB-1/2/3XLD-2 (m) | (−368, 0, 0) (166.83, −288.96/288.96, 0) |

| Stiffness of cable winch (linear cable) (kN/m) | 1.0 × 104 |

| Freedom | Natural Frequencies (Rad/s) |

|---|---|

| heave | 0.3049 |

| roll | 0.2158 |

| pitch | 0.2173 |

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Mass of unit length (kg/m) | 685 |

| Equivalent diameter (m) | 0.088 |

| Stiffness of mooring cables (catenary) (kN) | 3.27 × 106 |

| Breaking force (kN) | 2.23 × 104 |

| Length of ML-1/2/3 (m) | 850 |

| Coordinates of WFDLK-1/2/3 (m) | (−58.25, 0, −14), (29, −51.07/51.07, −14) |

| Coordinates of MD-1/2/3 (m) | (−837.6, 0, −200), (418.8, −725.4/725.4, −200) |

| Parameter | EC1 | EC2 | EC3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wind velocity (m/s) | 0 | 11.4 | 11.4 |

| Significant wave height (m) | 1.5 | 1.5 | 2.5 |

| Peak-spectra period (s) | 6.5 | 6.5 | 7.5 |

| Current velocity (m/s) | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| The load direction (deg) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| The FOWT with Different Environmental Conditions | EC1 | EC2 | EC3 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stages | Motions | Max | Min | Mean | Max | Min | Mean | Max | Min | Mean |

| P1 | Surge/(m) | 2.257 | −1.759 | 0.336 | 2.856 | −1.815 | 1.087 | 3.837 | −6.240 | −0.668 |

| Sway/(m) | 0.407 | −0.400 | −0.020 | 1.120 | −1.765 | −0.031 | 1.351 | −1.194 | −0.019 | |

| Heave/(m) | −0.618 | −0.755 | −0.691 | −0.620 | −0.763 | −0.696 | −0.559 | −0.846 | −0.696 | |

| Roll/(deg) | 0.032 | −0.034 | −0.001 | 0.291 | −0.242 | −0.008 | 0.294 | −0.305 | −0.004 | |

| Pitch/(deg) | 0.139 | −0.129 | −0.012 | −1.400 | −1.838 | −1.651 | −1.424 | −1.850 | −1.657 | |

| Yaw/(deg) | 0.095 | −0.175 | −0.019 | 0.428 | −1.127 | −0.422 | 4.383 | −6.462 | −0.388 | |

| P2 | Surge/(m) | 1.643 | −0.722 | 0.559 | 2.442 | −0.054 | 1.207 | 3.814 | −2.886 | 0.194 |

| Sway/(m) | 0.413 | −0.288 | 0.039 | 1.059 | −1.037 | −0.029 | 1.189 | −1.489 | −0.086 | |

| Heave/(m) | −1.665 | −1.800 | −1.738 | −1.673 | −1.816 | −1.748 | −1.606 | −1.903 | −1.749 | |

| Roll/(deg) | 0.037 | −0.044 | −0.001 | 0.242 | −0.223 | −0.009 | 0.283 | −0.261 | −0.009 | |

| Pitch/(deg) | 0.073 | −0.127 | −0.038 | −1.397 | −1.760 | −1.617 | −1.390 | −1.835 | −1.607 | |

| Yaw/(deg) | 0.069 | −0.062 | 0.003 | 0.263 | −0.380 | −0.033 | 0.140 | −0.257 | −0.023 | |

| P3 | Surge/(m) | 1.036 | −0.366 | 0.449 | 2.230 | −0.341 | 1.039 | 2.598 | −1.971 | 0.738 |

| Sway/(m) | 0.250 | −0.244 | 0.014 | 0.226 | −0.490 | 0.010 | 0.840 | −0.683 | 0.078 | |

| Heave/(m) | −1.949 | −2.083 | −2.020 | −1.968 | −2.107 | −2.042 | −1.903 | −2.196 | −2.042 | |

| Roll/(deg) | 0.061 | −0.065 | −0.001 | 0.266 | −0.251 | −0.008 | 0.262 | −0.225 | −0.005 | |

| Pitch/(deg) | 0.061 | −0.143 | −0.038 | −1.357 | −1.712 | −1.578 | −1.344 | −1.781 | −1.578 | |

| Yaw/(deg) | 0.043 | −0.046 | −0.002 | 0.135 | −0.227 | −0.013 | 0.185 | −0.270 | −0.009 | |

| P4 | Surge/(m) | 1.036 | −0.366 | 0.449 | 3.307 | 1.409 | 2.356 | 4.328 | 1.022 | 2.630 |

| Sway/(m) | 0.250 | −0.244 | 0.014 | 0.850 | −0.751 | 0.044 | 0.844 | −0.731 | 0.053 | |

| Heave/(m) | −1.949 | −2.083 | −2.020 | −1.947 | −2.100 | −2.025 | −1.866 | −2.202 | −2.025 | |

| Roll/(deg) | 0.061 | −0.065 | −0.001 | 0.264 | −0.253 | −0.007 | 0.266 | −0.253 | −0.007 | |

| Pitch/(deg) | 0.061 | −0.143 | −0.038 | −1.473 | −1.781 | −1.642 | −1.435 | −1.872 | −1.656 | |

| Yaw/(deg) | 0.043 | −0.046 | −0.002 | 0.180 | −0.270 | −0.012 | 0.181 | −0.269 | −0.011 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zhong, Y.; Wang, J.; Chen, Y.; Yu, N.; Chen, M.; Tang, Y. Dynamic Analysis of the Mooring System Installation Process for Floating Offshore Wind Turbines. Sustainability 2026, 18, 1199. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18031199

Zhong Y, Wang J, Chen Y, Yu N, Chen M, Tang Y. Dynamic Analysis of the Mooring System Installation Process for Floating Offshore Wind Turbines. Sustainability. 2026; 18(3):1199. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18031199

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhong, Yao, Jinguang Wang, Yingjie Chen, Ning Yu, Mingsheng Chen, and Yichang Tang. 2026. "Dynamic Analysis of the Mooring System Installation Process for Floating Offshore Wind Turbines" Sustainability 18, no. 3: 1199. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18031199

APA StyleZhong, Y., Wang, J., Chen, Y., Yu, N., Chen, M., & Tang, Y. (2026). Dynamic Analysis of the Mooring System Installation Process for Floating Offshore Wind Turbines. Sustainability, 18(3), 1199. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18031199