1. Introduction

The global energy landscape is undergoing substantial transformation, driven by the need to mitigate climate change and ensure energy security. This urgency is reflected in Sustainable Development Goal 7, which calls for “universal access to affordable, reliable, sustainable and modern energy” by 2030 [

1]. Achieving this has proven to be a challenge, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa, which accounts for 75% of the world’s energy access deficit [

2]. This research focuses on a case study of South Africa, a country that also faces the energy challenges that are prevalent across sub-Saharan Africa.

South Africa’s electricity challenges mainly include persistent grid instability, high electricity costs, and high carbon emissions [

3,

4]. Since 2008, scheduled power cuts have been implemented to mitigate the energy access deficit. In 2024, the frequency of power cuts declined, with the national electricity supplier projecting decreased power cuts going forward [

5]. However, the costs remain high. South African electricity tariffs increased by 190% from 2014 to 2024, far exceeding the inflation rate of 5.2% over the same period [

6]. In addition, the national electricity supply remains highly carbon-intensive due to its continued reliance on coal-fired power generation [

4].

Institutions such as schools are affected by these challenges. Rapidly increasing tariffs place a financial burden on schools, diverting limited resources from core educational purposes [

7]. Furthermore, power outages disrupt academic activities and hinder effective school functioning. The low- to non-fee-paying schools are disproportionately affected by this, as they primarily rely on government funding, which typically increases at a slower rate than electricity tariffs [

8]. While renewable energy sources such as photovoltaic (PV) solar are available, the associated installation costs remain a major constraint for already resource-limited schools.

Beyond schools, households across South Africa are also affected by high electricity costs and an unreliable supply, although the impacts vary across income groups. High-energy-consuming households often face significantly higher tariffs. For example, high-income households in the Stellenbosch municipality pay nearly three times more per kilowatt-hour (kWh) than the lowest consumers [

9]. This results in households, especially those with high income, resorting to photovoltaic battery energy storage systems (PV/BESS) [

10]. However, limited storage capacity often results in unused excess energy [

8], reducing the gains that come with PV/BESS. Low-income households, on the other hand, are already faced with financial constraints, and they remain exposed and solely reliant on the expensive and unreliable public power supply. Despite differences in income, all residential areas need more sustainable solutions to combat these energy challenges.

In addition to renewable energy, various demand-side and efficiency-based strategies have been explored to reduce electricity costs in buildings. One such solution is controlling electric water heaters based on predicted demand instead of simply maintaining a constant temperature [

11]. Hughes and Larmour [

12] analyse other methods, encouraging retrofits in existing residential areas to meet water heating requirements using solar water heaters and heat pumps. Hughes and Larmour [

12] further proposes government-subsidised scrapping programs to encourage the replacement of inefficient appliances like refrigerators. All of the proposed solutions are costly for the majority, necessitating further research into methods to alleviate the impacts of this energy crisis.

Although these challenges are central to buildings, it is also important to consider the broader emission landscape and how other sectors interact with this energy system. The transport sector remains a major contributor to air pollution, with road transport accounting for approximately 23% of global emissions [

13]. This has driven the global transition from internal combustion engines (ICEs) to electric vehicles (EVs), with EVs accounting for 18% of global car sales in 2023, up from 2% five years prior [

14]. However, in South Africa, charging EVs from a coal-powered grid undermines these environmental benefits [

15]. Pretorius et al. [

16] found that EVs charged on coal-based electricity produce higher

emissions than ICE vehicles, while also adding pressure to an already fragile grid [

13]. In order for South Africa to seamlessly integrate EVs despite its challenges, it is crucial to consider shared sustainable energy solutions.

1.1. Research Questions

Building on the preceding discussion, this research is structured around the following research questions.

- 1.

What range of system configurations allows school-based solar-battery microgrids to achieve energy autonomy while financially sustaining themselves through electricity trading?

- 2.

How do different system design and operational choices influence the technical and financial performance of the school-centred microgrids?

1.2. Scope

This study assesses the feasibility of school-centred PV/BESS energy trading systems under realistic external load scenarios. The analysis prioritises exploration of the design space and examination of system-level trade-off between total investment cost and net cash flow within a local energy-trading framework. Households and electric motorbikes are used as external entities to determine whether the school and systems can support additional loads of comparable magnitude.

1.3. Contribution

This study introduces an optimisation framework in which schools act as energy producers, supplying households and electric motorbikes within a local trading market. It evaluates PV/BESS sizing using Non-Dominated Sorting Genetic Algorithm II (NSGA-II) and explicitly incorporating reliability constraints that are largely absent from existing P2P trading studies. In addition, the inclusion of electric motorbikes adds flexible-demand participants that can engage in energy trading independent of the grid. By using empirically derived consumption profiles from South African schools, households and electric motorbikes, this study further fills a critical geographic and contextual gap in quantifying trading prices, resource requirements, and payback periods for a school-centred energy trading model.

3. Methodology

This section describes the modelling and optimisation framework used to evaluate the feasibility of a school-centred PV/BESS and its ability to trade energy with external entities. The approach combines half-hourly energy flow simulation with exploratory sampling and multi-objective optimisation to assess how different system configurations influence financial returns and supply reliability. At the core of the framework is an evaluation function that simulates three years of PV power generation, battery behaviour, energy distribution, revenues, savings, and reliability for the school and external entities.

3.1. Data

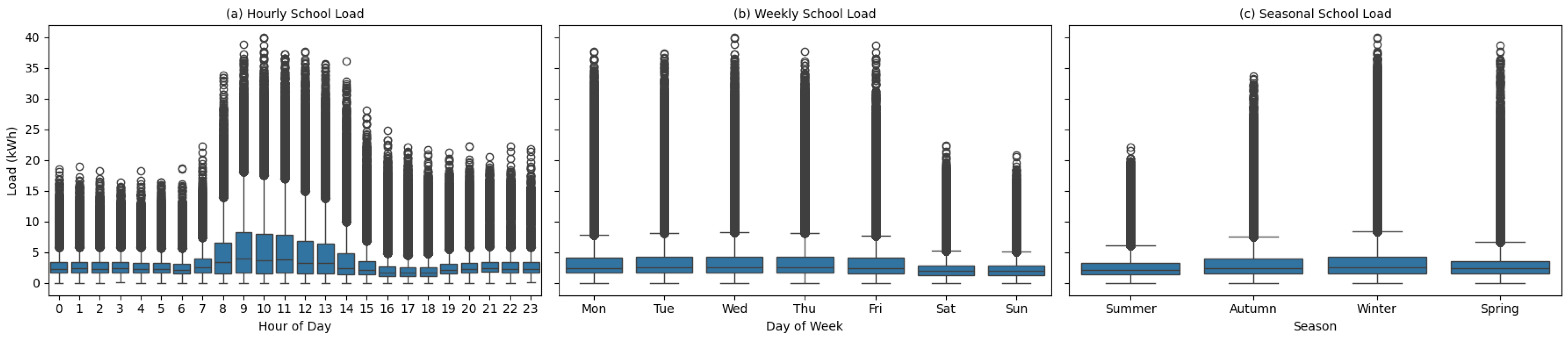

This study made use of four datasets: solar irradiance, schools, electric motorbikes and household energy demand. The school demand dataset, sourced from Samuels et al. [

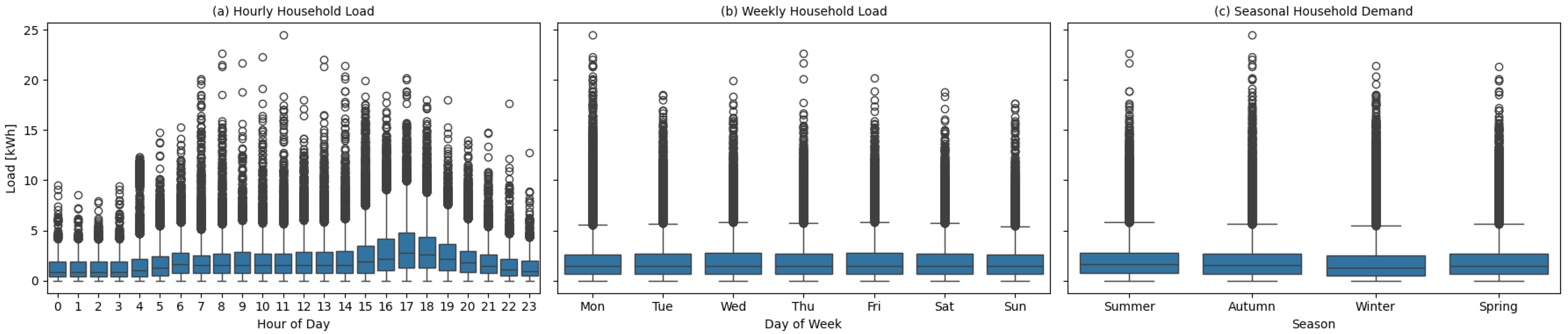

25], provides half-hourly electricity consumption data for 53 schools in the Western Cape; the data were collected through smart meters over a one-year period. Household electricity demand was obtained from Eskom et al. [

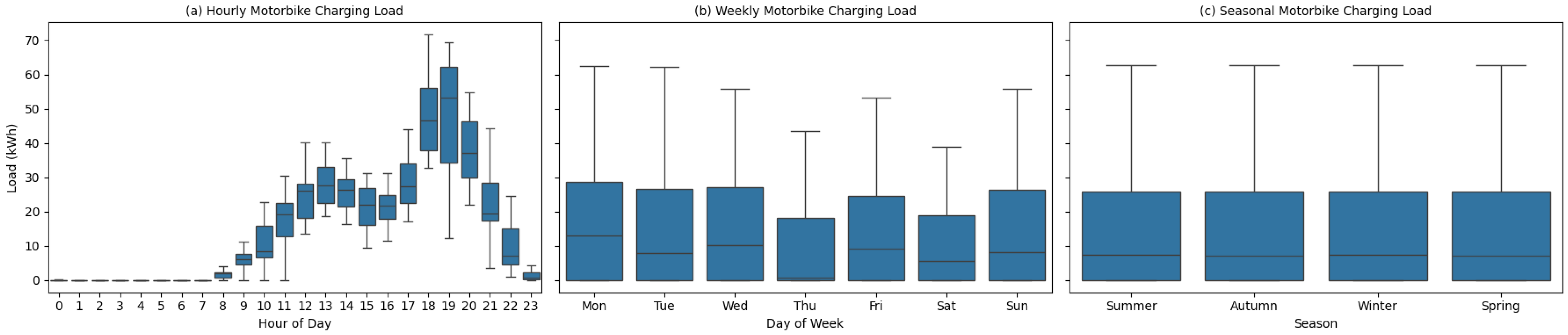

26], which contains half-hourly consumption records for South African households across various regions from 1994 to 2014. Fourteen households with complete measurements for the year 2014 were selected for this study. One-minute electric motorbike load data from Stratford and Booysen [

27] were aggregated to a half-hourly resolution to align with the other datasets. Finally, irradiance data was generated with System Advisory Model (SAM) [

28], which simulated three years of global horizontal irradiance (GHI) for the Stellenbosch region.

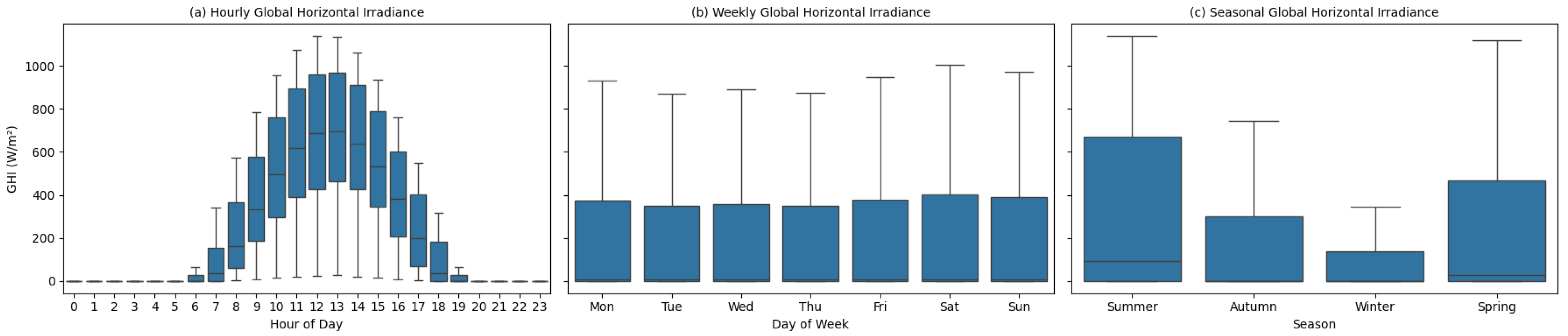

Figure 1,

Figure 2,

Figure 3 and

Figure 4 show boxplots for distributions of irradiance, schools, households, and electric motorbikes.

3.2. Modelling Procedures

3.2.1. Solar Generation

The solar panels modelled in this study each have a cost of R1 500 each, a rated output of 0.455 kW per panel, an efficiency of 20.6%, and a surface area of 2.21 m

2. Their performance is assumed to degrade linearly to 80% over 25 years, corresponding to an annual degradation rate of 0.8%. Using GHI data and the panel specifications, the solar energy generated at each timestep is calculated using Equation (

1).

In this set of equations, = 0.5 h, represents the theoretical power output under the given irradiance, and is the rated output of installed panels. is irradiance in kW/ every 30 min, A is the panel area in , is the panel efficiency, N is the number of panels, = 0.455 kW, and y is the simulation year.

3.2.2. Battery Energy Storage System

The Battery Energy Storage System (BESS) is based on Lithium Iron Phosphate

battery modules with the following specifications: a total capacity of 5 kWh, a usable capacity of 4 kWh, and a cost of R14 000 per module. The charge and discharge efficiencies,

and

, are both 0.95, with a charge rate of 0.7 C and a discharge rate of 0.9 C. Each battery module degrades to 75% after 4000 cycles or 10 years, assuming operating temperatures between −20 °C and 45 °C. To model its behaviour over time, the State of Charge (SOC) at any timestep is defined by Equation (

2).

where

,

,

and N denote the charging power, the discharging power, the initial capacity of a single battery module, and the number of modules in the system, respectively. The SOC at t = 0 is assumed to be 100%, after which it is constrained between 20% and 95% to extend the battery’s lifespan [

29]. At each charging and discharging event, partial cycles are accumulated as shown in Equation (

3). Charging events are limited by the effective usable capacity of the battery defined by Equation (

4).

and

refer to the capacity at time t and the initial capacity, respectively.

3.3. Performance Measures

The performance of the optimisation framework is evaluated using three core performance metrics used during optimisation and a set of complementary performance metrics. The core performance metrics are total investment costs, net cash flow, and school supply reliability. Total investment represents the upfront capital expenditure for system deployment. Net cash flow represents the sum of revenues from electricity trading and savings resulting from elimination of grid electricity purchase. School supply reliability is imposed as a hard constraint to ensure there will be an uninterrupted electricity supply to the school under off-grid operation. The complementary performance indicators are excess energy, break-even period, and external entity supply reliability.

Savings are evaluated using a time-of-use (TOU) tariff structure applied to schools and revenue using renewable energy export TOU applied to traded electricity, both obtained from Stellenbosch Municipality [

9]. The tariff defines peak, standard, and off-peak periods that vary by season and day of the week, with distinct rates for high-demand (winter) and low-demand (summer) periods. Prices are based on the municipal tariff schedule because it represents a regulatory-permissible benchmark for electricity transactions within the study context. The renewable export tariffs are priced below the equivalent grid purchase tariff, ensuring economic benefits for the participating entities while maintaining the competitive advantage that comes with P2P trading. Electricity tariffs were assumed to increase by 10% annually, with adjustments applied each July. Net cash flow was subsequently discounted to present value to account for inflation. The mathematical formulations of the savings, investment costs and reliability are given in Equations (

5)–(

7).

In Equation (

5), E(t) denotes the electrical energy supplied at times step t, F denotes fixed monthly charges, and C denotes the applicable unit cost depending on TOU. Equation (

6) defines the total investment cost as the sum of PV module acquisition, battery acquisition cost (bat), inverter cost (invtr), electrical wiring system cost (elec), and mounting system cost (mech). The wiring and mounting system cost are modelled as functions of the number of installed PV panels consisting of a fixed base cost and a component proportional to PV capacity, reflecting mounting structures, wiring, and installation labour requirements. Equation (

7) computes school supply reliability as the ratio of met electrical energy demand to total electrical energy demand, averaged across the three simulated years.

3.4. Evaluate Function

The evaluate function shown in Algorithm 1 simulates the operation of the school-centered PV/BESS over a three-year period at half-hourly resolution. Demand is assumed to be constant for all three entities, while GHI changes each year are all simulated for a non-leap year. For a given system configuration, it simulates solar power generation, battery degradation, energy dispatch, financial performance, and supply reliability for both the school and external entities. The same evaluation function is used for both sampling and optimisation. For sampling, the inputs are the number of panels, number of battery modules, demand factor, and operating hours, while for optimisation, the number of battery modules and number of panels are considered.

| Algorithm 1 Evaluate function for a given PV/BESS configuration |

Require: Number of panels, Number of battery modules, demand profiles, GHI data - 1:

Initialise cumulative revenue, savings, solar generated, demand, unmet demand - 2:

for year to 3 do - 3:

for each timestep t do - 4:

Compute , , - 5:

if < then - 6:

Discharge battery to meet school demand - 7:

Discharge battery to meet external demand - 8:

else - 9:

Charge battery with available solar - 10:

Supply school using solar - 11:

Supply external demand using remaining solar and/or battery - 12:

end if - 13:

Update reliability, revenue, savings, unmet demand, and battery cycles - 14:

end for - 15:

end for return Average revenue, average savings, average net cash flow, investment cost, payback period, school reliability, external reliability, average solar generated, average excess energy generated

|

3.5. Exploratory Sampling Using Latin Hypercube Sampling

Latin Hypercube Sampling (LHS) was used to explore the full design space and quantify the relationship between system design variables and performance indicators prior to optimisation. LHS ensures a uniform sampling of the multidimensional input space. Four decision variables were sampled: the number of solar panels, the number of battery modules, the school operating hours, and a demand factor representing improvements in energy efficiency. The sampled ranges were as follows:

Number of solar panels: 40 700.

Number of battery modules: .

Operating hours per day on school days: ∈{6, 8, 11, 24}.

Demand reduction factor: .

Each sampled configuration was evaluated using Algorithm 1. The resulting dataset formed the basis of the correlation analysis presented in

Section 4.1, which was used to identify the most influential design variables and inform the optimisation formulation.

3.6. Multi-Objective Optimisation Using NSGA-II

The system design problem involves competing objectives, as increasing system size improves net cash flow and reliability but also raises investment costs. To capture these trade-offs, the problem was formulated as a multi-objective optimisation problem, where a set of pareto-optimal solutions are generated. This was solved using Non-Dominated Sorting Genetic Algorithm II (NSGA-II), a widely used evolutionary algorithm known for its computational efficiency and suitability with a small number of objectives [

30,

31]. NSGA-II was selected due to its ability to maintain solution diversity while converging towards a set of optimal solutions.

The optimisation was implemented in Python version 3.12.6 using the pymoo library within the same software environment. A population size of 30 and 30 offspring per generation were used. Sensitivity tests were conducted by increasing both the population size and number of offspring to 100; however, no material changes were observed in the resulting pareto front. The smaller population was, therefore, used to retain computational efficiency. Integer random sampling ensured feasible combinations of solar panels and battery modules within the defined bounds. Each candidate solution was evaluated using Algorithm 1. The optimisation problem is defined as follows. Let

.

denote the total investment cost.

denote the average net cash flow.

denote the school supply reliability in year y ∈ {1,2,3}.

Following optimisation, the pareto-optimal solutions were ranked using the Technique for Order of Preference by Similarity to Ideal Solution (TOPSIS). TOPSIS is one of the most widely used MCDM methods [

32], and is favoured for its simplicity, practicality, and computational efficiency [

32,

33]. TOPSIS ranks alternatives based on their closeness to the positive ideal solution, which maximises benefits and minimises costs, and their distance from the negative ideal (anti-ideal) solution [

32]. For this study, TOPSIS was used as follows:

Let i = 1, 2, …, 900 index the set of pareto-optimal configurations generated by NSGA-II for a given scenario. Each configuration i is characterised by multiple performance metrics and inputs, the two objectives central to this problem are investment cost

and the average

. The decision matrix is therefore defined as follows:

The two were then normalised and weighted as shown in Equation (11). A slightly higher weight was assigned to investment cost to reflect budget sensitivity in school-based installations.

where

and

. The positive ideal solution represents the configuration with the lowest-weighted and normalised investment cost and the highest-weighted and normalised average net cash flow, while the negative (anti-ideal) solution represents the opposite extreme. These are defined by Equations (

12) and (

13)

The Euclidean distances of each configuration from the positive and negative ideal solutions are computed as

and

.

The relative closeness,

of each configuration to the ideal solution is then calculated by Equation (

16), after which the configurations are ranked in descending order of

. The configuration with the highest

is selected as the most balanced solution for the given scenario.

3.7. Scenario Analysis

The optimisation was performed under six scenarios:

- 1.

School sells to households.

- 2.

School sells to electric motorbikes.

- 3.

School sells to both households and electric motorbikes.

- 4.

School sells to households with a battery each.

- 5.

School sells to electric motorbikes with an extra battery in addition to the one they have.

- 6.

School sells to households and electric motorbikes with a battery.

The best scenario was then selected and applied to 53 schools in the Western Cape, and the results are compared.

4. Results and Discussion

This section presents the results derived from the simulation described in the Methodology. The analysis begins by examining how system inputs shape financial and energy supply reliability outcomes. It then evaluates the performance of energy trading between one school and external entities; 14 households and 125 electric motorbikes, both individually and jointly. Additional scenarios incorporating battery storage for external entities are also assessed. Building on these findings, this section identifies the most balanced system configuration using the TOPSIS method for each scenario. Finally, the solution is assessed for scalability by applying optimisation across 53 schools with varying annual electricity consumption.

4.1. Correlation Analysis of System Inputs and Performance Indicators

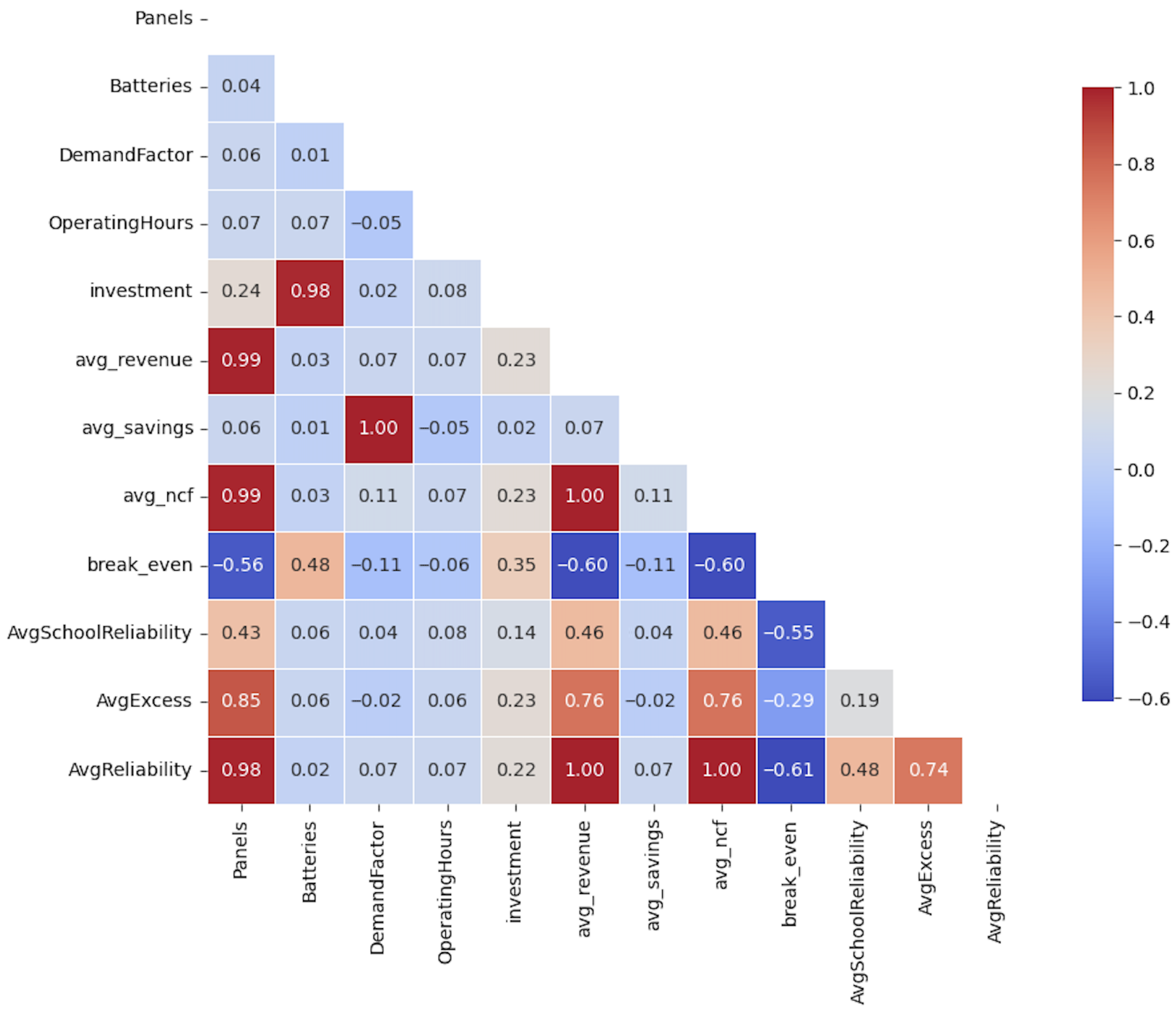

Factors that can influence the costs, revenue, and eventually break-even for this system, as discussed in the Methodology, are varying number of panels, number of battery modules, operating hours for the school energy system, and improving the efficiency of the system. In the model, the efficiency of the system is improved by introducing a demand factor to the demand per timestep. A range of inputs are generated using LHS and the outputs are presented in

Figure 5. The correlations are discussed below.

4.1.1. Number of Panels

The number of panels shows a strong positive correlation with supply reliability, revenue, and average net cash flow, as well as a moderate negative correlation with break-even years. Increasing the number of panels increases daytime energy generation, which improves supply reliability and increases revenue.

4.1.2. Number of Battery Modules

Battery capacity is strongly correlated with investment costs and moderately correlated with break-even years. Given that each battery module costs R14 000 compared to R1 500 per solar panel, batteries are expected to have the strongest impact on overall system cost. However, battery storage remains necessary to achieve 100% reliability for the school. Since the school primarily operates during daylight hours, when solar power is available, extensive storage capacity is not required. This suggests that configurations in which residential areas and electric motorbikes have dedicated storage should be considered, as their peak demand periods indicate a greater benefit from increased storage capacity.

4.1.3. Demand Factor

The demand factor shows a strong correlation with savings but little association with other performance metrics. As expected, reducing the school’s energy demand lowers electricity expenditure, even under grid-connected operation. However, because savings have a limited influence on net cash flow, the demand factor has an insignificant effect on the break-even period. Consequently, efficiency improvements at the school should only be pursued where they incur no additional costs, such as through behavioural interventions.

4.1.4. Operating Hours

Operating hours show no significant correlation with the performance metrics, indicating that variations in school operating time have minimal influence on overall system performance. Although reduced operating hours would be expected to lower energy consumption, most of the hours removed occur outside normal school hours, when energy demand is already low. Consequently, varying operating hours is not recommended as an effective intervention.

4.1.5. Other Correlations

Other moderate-to-strong correlations were observed between the performance metrics. A strong correlation exists between reliability and excess energy, as achieving higher reliability typically requires larger system sizes, which in turn lead to increased excess energy, particularly when storage capacity is limited. In addition, break-even period shows a strong correlation with average revenue and net cash flow, indicating that savings contribute only a small share of the overall net cash flow.

Given that variations in demand factor and operating hours have a limited influence on system performance indicators, the optimisation focuses solely on the number of solar panels and battery modules as the primary decision variables.

4.2. Exploring Optimal Energy-Trading Scenarios for One School Case Study

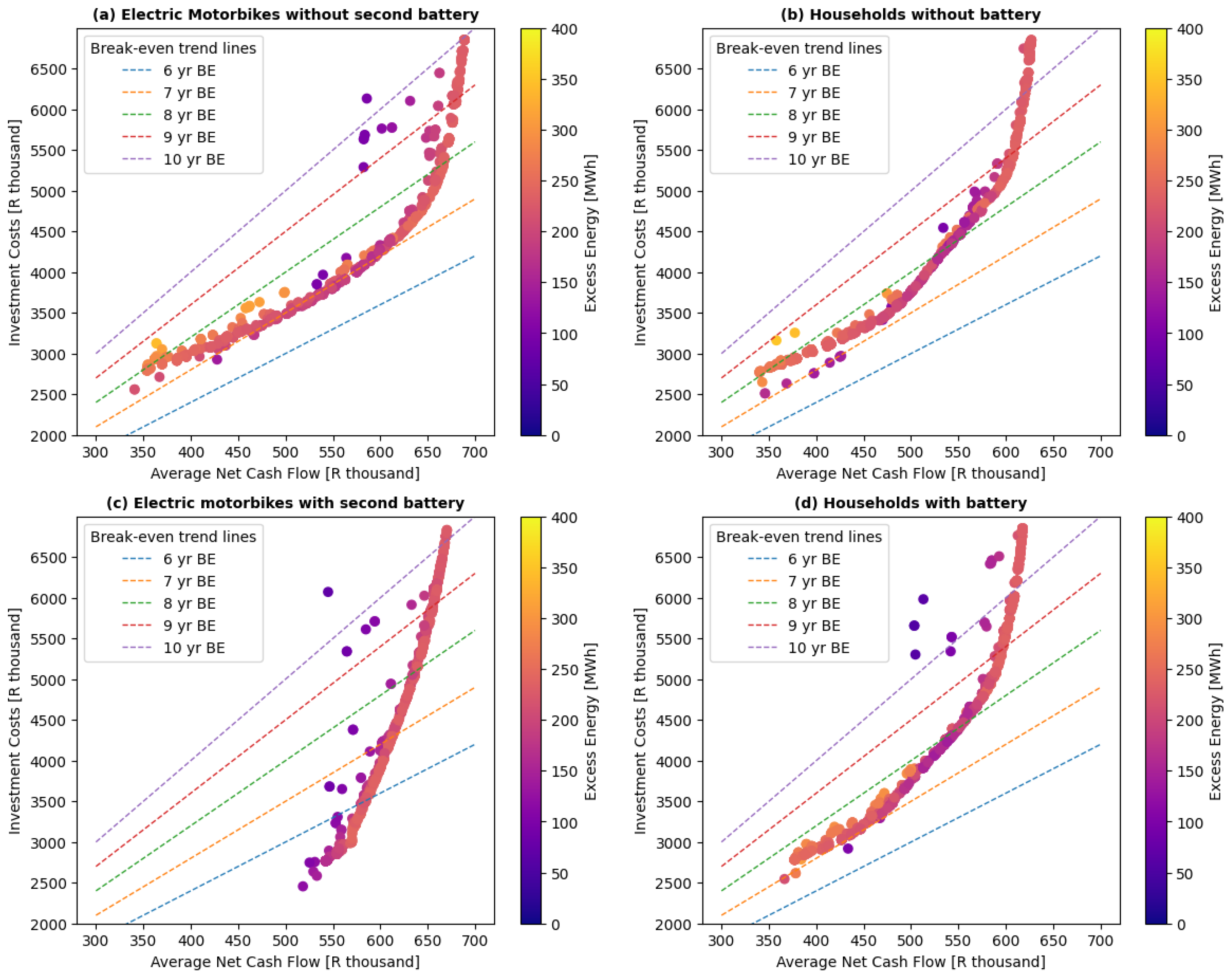

Figure 6 presents optimisation results for energy trading with households and electric motorbikes, both with and without additional external battery storage. Each point in the scatter plots represents a unique combination of solar panels and school-side battery modules generated by the NSGA-II optimisation described in the previous section. The x-axis shows the average net cash flow for three years (in thousand Rands), while the y-axis shows the corresponding total investment costs for that configuration. Each configuration is coloured according to the average excess energy produced over the three year period in MWh, using a colourmap where darker shades indicate lower excess energy and lighter shades indicate high excess energy. The dashed lines represent the break-even trend lines.

Figure 6a,b show performance when energy trading with electric motorbikes and battery without providing a battery to the external entity, while (c) and (d) show equivalent comparisons when the electric motorbikes have an extra battery and each household has a battery.

Figure 7 shows similar results but for energy trading with both entities, (a) without battery and (b) with battery. When comparing electric motorbikes and households without external storage, there are apparent (although not significant) differences in performance. For both entities, net cash flow increases with investment costs, but electric motorbikes consistently achieve higher returns, reaching net cash flow values close to R700 000, whereas households converge around R650 000. This difference can be attributed to the electric motorbike daily energy profile in

Figure 4, which exhibits peaks during the day and in the evening, creating more opportunities to absorb solar generation. In contrast, households peak in the evening, reducing their ability to utilise the excess daytime solar generated. Despite these differences, both scenarios yield similar payback periods, mostly between 7 and 8 years, reflecting the comparable annual consumption levels. The excess energy generated is also not significantly different.

Introducing a battery of the same capacity for the school to the external entities alters the system’s performance most notably in electric motorbikes. This is because there are 125 electric motorbikes, while there are only 14 households, each with the same capacity of 5 kWh. With an additional battery, the electric motorbikes configurations achieve higher net cash flows, starting from R500 000 for investment costs, where the non-battery scenario reaches only R350 000. The payback periods for electric motorbikes with an extra battery start at less than 6 years compared to 7 years without an extra battery. In contrast, households exhibit only marginal improvements with the addition of a battery. The net cash flow shows only a difference of less than R50 000 and the payback period differing by less than a year for the same investment costs. Across all scenarios, there is substantial excess energy, often exceeding 150 MWh, especially when there is no extra storage. This surplus indicates potential for more revenue through sale of excess energy.

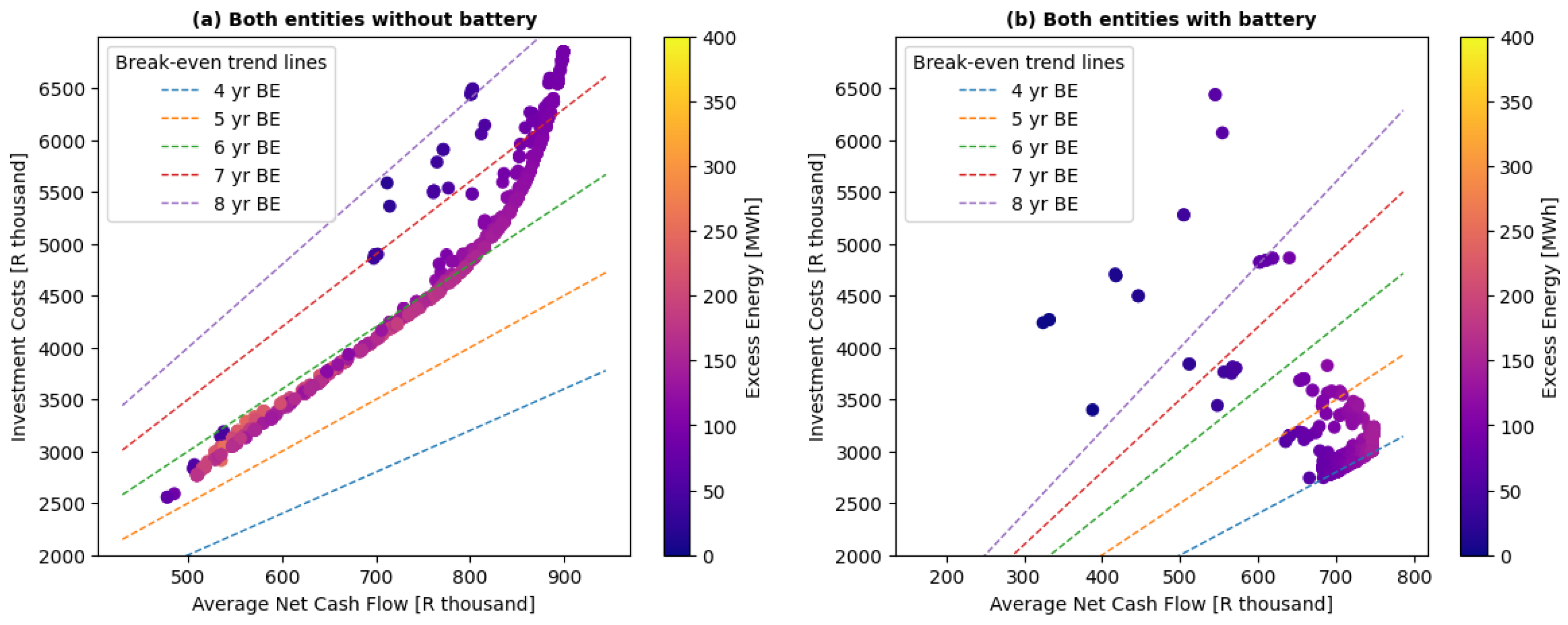

Figure 7 shows optimisation results for energy trading with both households and electric motorbikes. When both entities participate, the model identifies higher-performing configurations across the investment range, with net cash flow starting from R500 000 to as high as R900 000 compared to the highest net cash flow of R700 000 with single entities. Payback periods are also significantly reduced. Without a battery, most solutions have a payback period of less than 6 years compared to less than 5 years when the entities have a battery. The excess energy generated is also noticeably low—less than 150 MWh for most solutions. This might, in fact, be the most favourable scenario for the schools.

Table 1 summarises the best-performing configurations selected from each scenario using the TOPSIS method, which ranks the solutions based on investment cost and net cash flow. For each scenario, the table reports the number of panels and batteries, total investment costs, average annual revenue, net cash flow, payback period, external entity supply reliability, and average excess energy.

The results show that the best financial performance comes from scenarios where the school trades with electric motorbikes or both entities, especially when battery modules are added. These cases achieve the highest net cash flows and the lowest payback period, driven by their ability to absorb the excess energy that is generated. However, the additional energy storage required in these scenarios would be purchased and maintained by the external entities, not the school. For this reason, a more conservative recommendation for the school is energy trading with both entities without external batteries, which still offers a short payback period of just over 5 years while relying on infrastructure that the school controls. Furthermore, energy trading with households may require further investment in infrastructure for a system that is not constrained by the grid. This makes energy trading with electric motorbikes without an extra battery technically more viable to implement.

4.3. Is the Proposed Solution a One-Size-Fits-All? Performance Across 53 Schools in Western Cape

The preceding analysis focused on a single case study school, but the validation of feasibility of the proposed PV/BESS trading system depends on how it performs across different schools. To evaluate this, the optimisation framework was applied to 53 schools in the Western Cape, each with distinct average annual energy consumption, as summarised by [

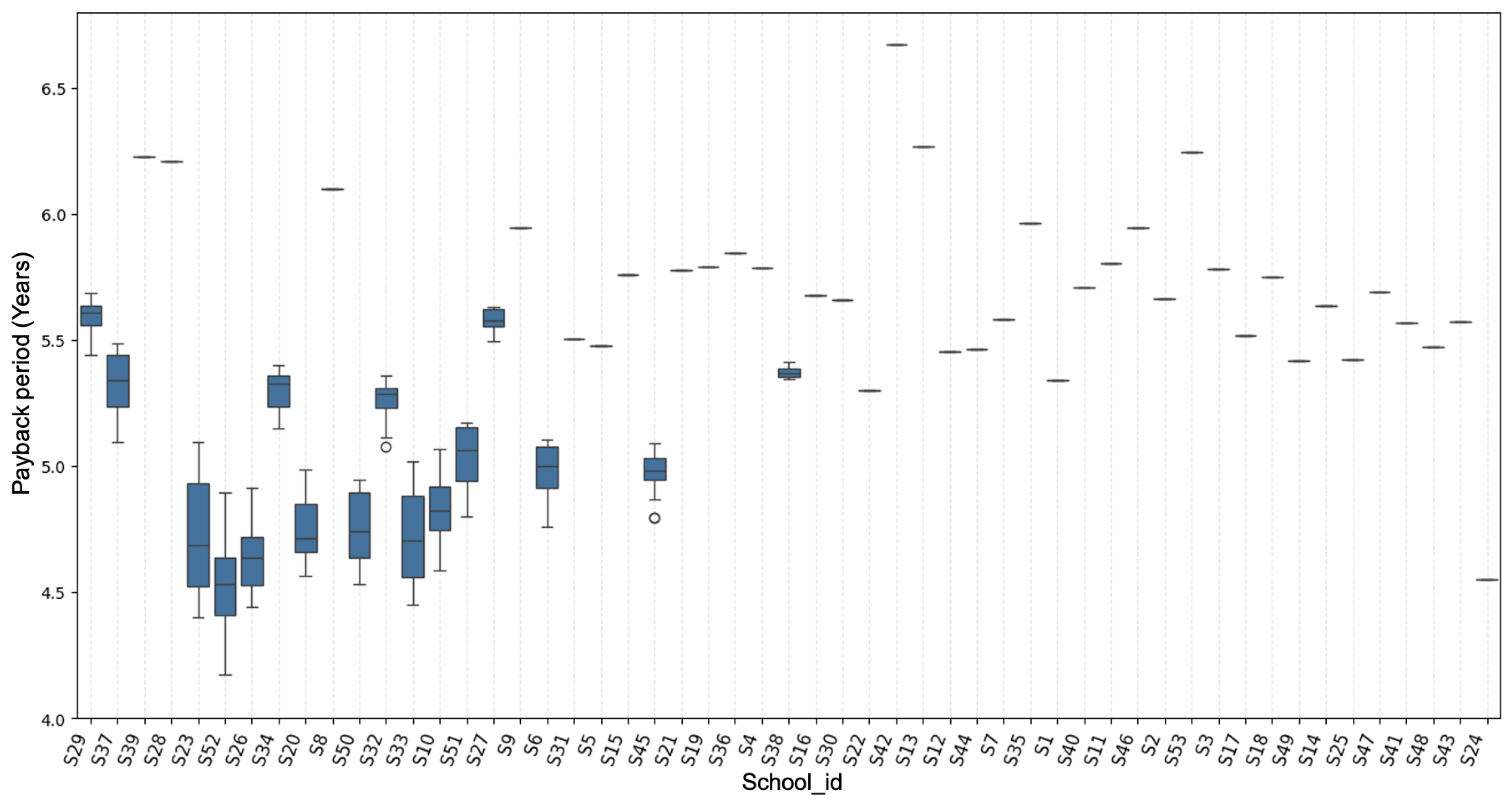

7]. The scenario discussed is when the schools sell to both external entities. This subsection compares the distribution of best solutions, the performance of each school’s best configuration, and the resource requirements associated with achieving optimal results.

Figure 8 summarises the payback periods of the top 30 out of 900 solutions generated for each school. The boxplots reveal that while some schools cluster tightly around a single payback period, others exhibit a much broader spread. Schools with wider boxplots tend to achieve shorter median payback periods, whereas those with narrow boxplots generally display longer payback periods. A narrow boxplot indicates a constrained optimisation landscape in which only a limited set of configurations can satisfy the reliability requirement. Although schools with high annual energy consumption most frequently exhibit this restricted behaviour, several low-consumption schools show similar patterns, suggesting that factors beyond annual demand may play a role too.

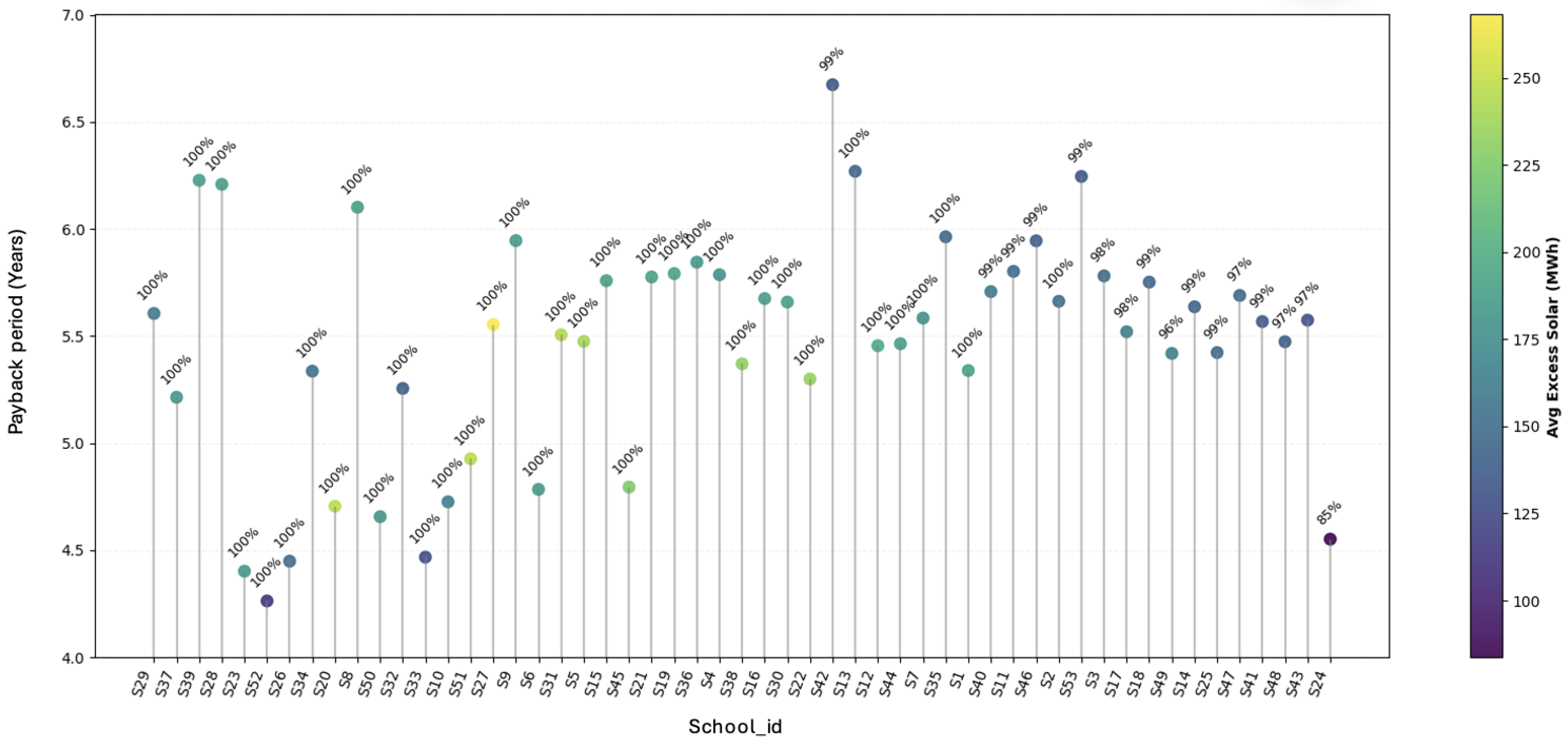

To further understand the variability in performance,

Figure 9 displays the best-performing configuration for each school, annotated with school reliability and coloured by excess solar energy. A clear difference emerges: smaller and mid-sized schools almost always achieve 100% school reliability and mostly show low payback periods, even though they generally generate more excess energy. On the other hand, schools with high annual energy consumption rarely achieve 100% school reliability because their energy needs exceed what capped PV/BESS sizes can sustain. These schools also produce less excess energy, meaning that nearly all their energy is absorbed.

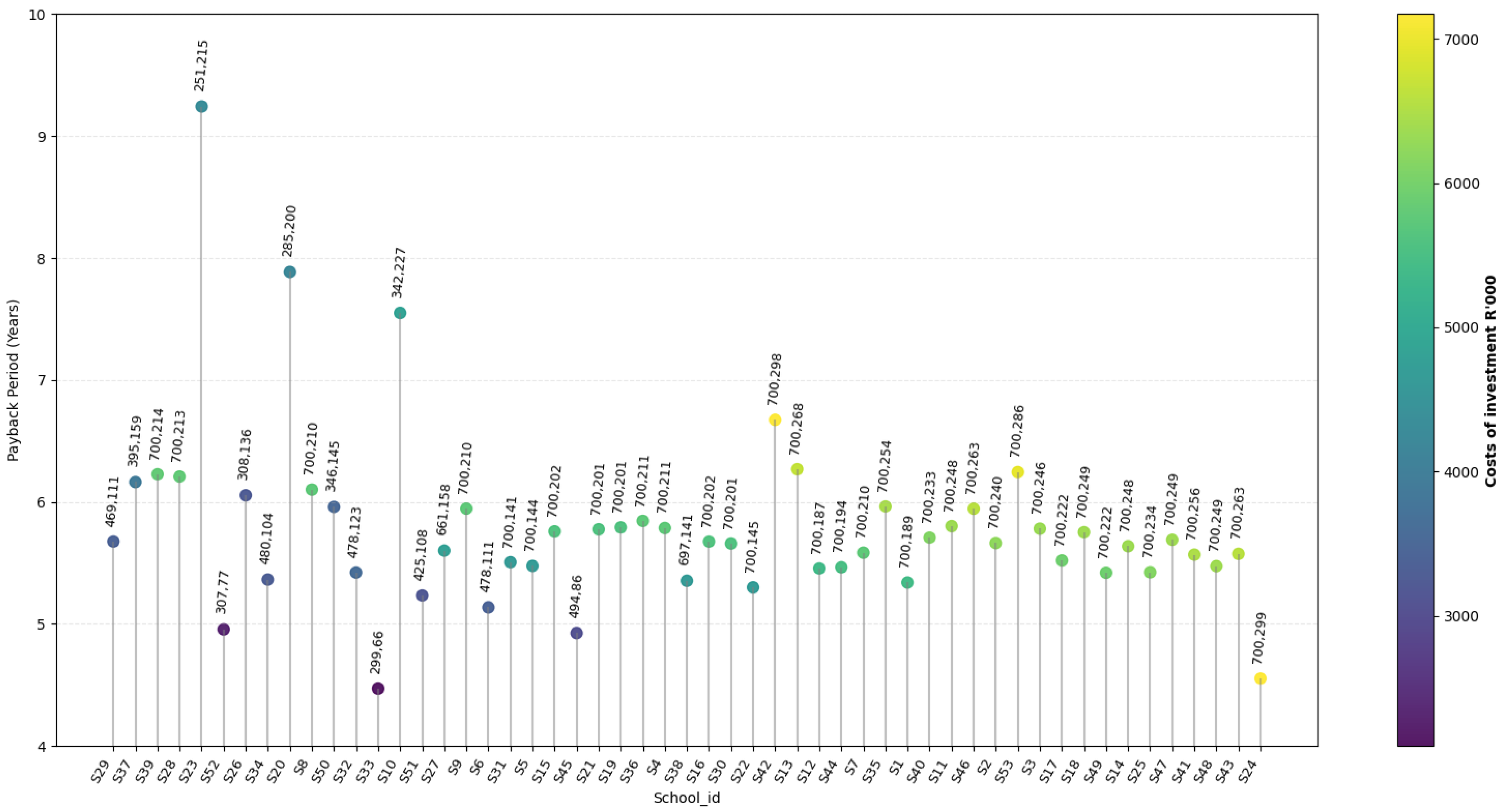

In practice, the deployment of PV systems in schools is often constrained by the available area, which can limit the feasibility of the cost-optimal configurations identified earlier. To account for this limitation, a complementary analysis is conducted using the same set of optimisation results. Rather than selecting cost-optimal solutions, the analysis identifies, for each school, the configuration that achieves the highest attainable school reliability while using the minimum number of PV panels. For most schools, this corresponds to 100% reliability, while 14 schools achieve reliability levels above 95% and one school attains approximately 85% reliability, as seen in

Figure 9. This selection represents an area-constrained operating case and provides a lower bound on system performance when PV expansion is restricted and school reliability is prioritised.

Figure 10 shows the results of this analysis with the data points labelled ’number of panels, number of batteries’ and the colour bar corresponding to the costs of investment. The results show that when PV capacity is constrained, achieving high reliability in schools becomes increasingly dependent on battery storage. As a result, payback periods increase relative to the cost optimal solutions discussed earlier, reflecting the higher investment required to compensate for limited solar generation. These results indicate that although high reliability can largely be maintained under area-limited conditions, doing so comes at a higher cost due to increased battery requirements. Consequently, if low investment costs are prioritised, the findings suggest that relaxing the school reliability target to less than 100% may be a more practical design choice than further increasing storage capacity. Nonetheless, when investment cost is not the primary constraint, the results still yield a payback period well below 10 years, with most schools averaging below seven years, indicating that the proposed framework remains economically viable.

Examining the number of panels and batteries required by each school reveals a broad pattern, though not a strict rule, in how resource needs scale across different schools. Many low-to-moderate-demand schools require fewer panels and relatively small battery units, while several higher-demand schools push toward upper limits of both components, especially with the 700-panel limit. However, notable exceptions exist: a few schools with comparatively low annual consumption still require disproportionately large battery and panel investments. These exceptions correspond to the schools that displayed narrow boxplots in

Figure 8, further emphasising that their solution space is highly constrained by their energy needs. This reinforces that resource need is reshaped not only by annual demand but by other structural factors.

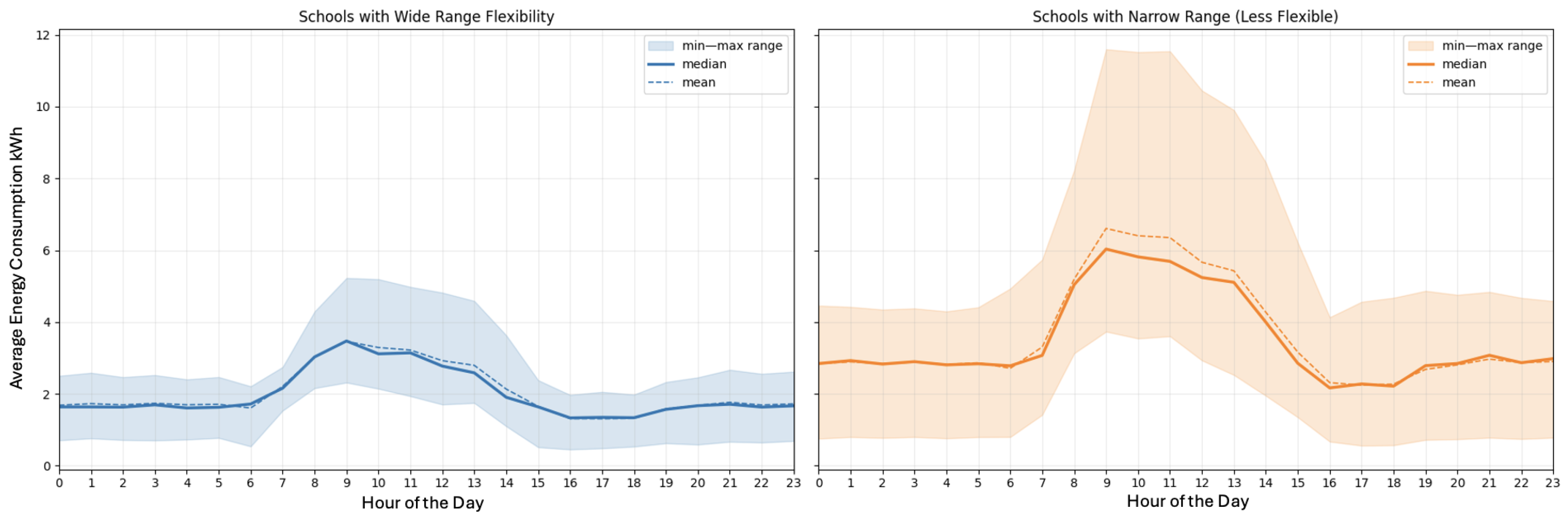

The results reveal another way of categorising the schools into two groups beyond their annual energy consumption. The groups emerge from how tight or loose each school’s feasible solutions are in

Figure 8 and how high the resource requirements are as shown in

Figure 10.

Figure 11 compares the two groups’ hourly load profiles: (a) schools with a wide range of solutions and (b) with a less flexible range of solutions. This comparison revealed a consistent pattern: the schools with flexible ranges have relatively lower daytime demand peaks and their demand begins to decline around 14:00 hrs, returning to close to early morning levels by mid-afternoon. In contrast, schools with narrow solution ranges exhibit a sharp morning increase, sustained elevated loads throughout the day, and only decrease to morning load levels at 15:00 hrs or later. This extended high-demand period places greater pressure on PV/BESS resources, limiting the number of possible configurations that would satisfy the reliability. Together, these observations suggest that the distinction between the schools is driven by their annual energy consumption demands, as well as shape and timing of their demand.

While different schools have different payback periods, the best payback periods are all less than 10 years. This suggests that the proposed solution has great potential for mitigating the impacts of the energy crisis in South African schools. With an in-depth study on grouping schools, the solution can be further optimised for different groups, thus making it more generally applicable. Factors such as school area may limit the number of panels used, so grouping the schools would undoubtedly allow better generalisation of the proposed solution.

5. Conclusions

This study assessed the techno-economic viability of schools acting as energy prosumers via P2P trading with households and electric motorbikes. Results from the NSGA–II optimisation indicate that school-centred energy trading is feasible, with payback periods ranging from 4 to 7 years for larger PV system deployments and from 4 to 9 years for minimum PV configurations within reliability constraints. Trading with electric motorbikes consistently outperformed household scenarios due to motorbike energy consumption patterns being better aligned with the PV solar generation profile. Trading with both households and electric motorbikes yielded the highest financial returns, especially when batteries were added for each entity.

5.1. Limitations

This study is subject to several limitations. First, it relies on static household electricity demand profiles from 2014, as this was the most recent publicly available dataset with the necessary temporal resolution. Secondly, the school data is limited to anonymized schools in the Western Cape, preventing site-specific design considerations such as roof area or existing infrastructure layout. Moreover, the model does not include external low-voltage distribution infrastructure costs for connecting schools to households, as such costs would be highly site-specific. Additionally, the current battery degradation model does not account for temperature effects.

5.2. Future Work

Future work will extend the study using the proposed framework through the use of more detailed site-specific school data. In particular, data collection could be considered so that recommendations made for the framework could be more specific to the school groups. In addition, the framework can be extended to consider alternative trading partners such as nearby businesses or other community loads to further assess the role of schools as local energy hubs. Further refinement of the battery degradation representation may also be considered for long-term deployment analysis.