Crafting Your Employability: How Job Crafting Relates to Sustainable Employability Under the Self-Determination Theory and Role Theory

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Background and Hypotheses Development

2.1. Job Crafting and Sustainable Employability

2.2. Job Crafting and Self-Determination

2.3. Self-Determination and Sustainable Employability

2.4. The Mediating Role of Self-Determination

2.5. The Moderating Role of Role Ambiguity

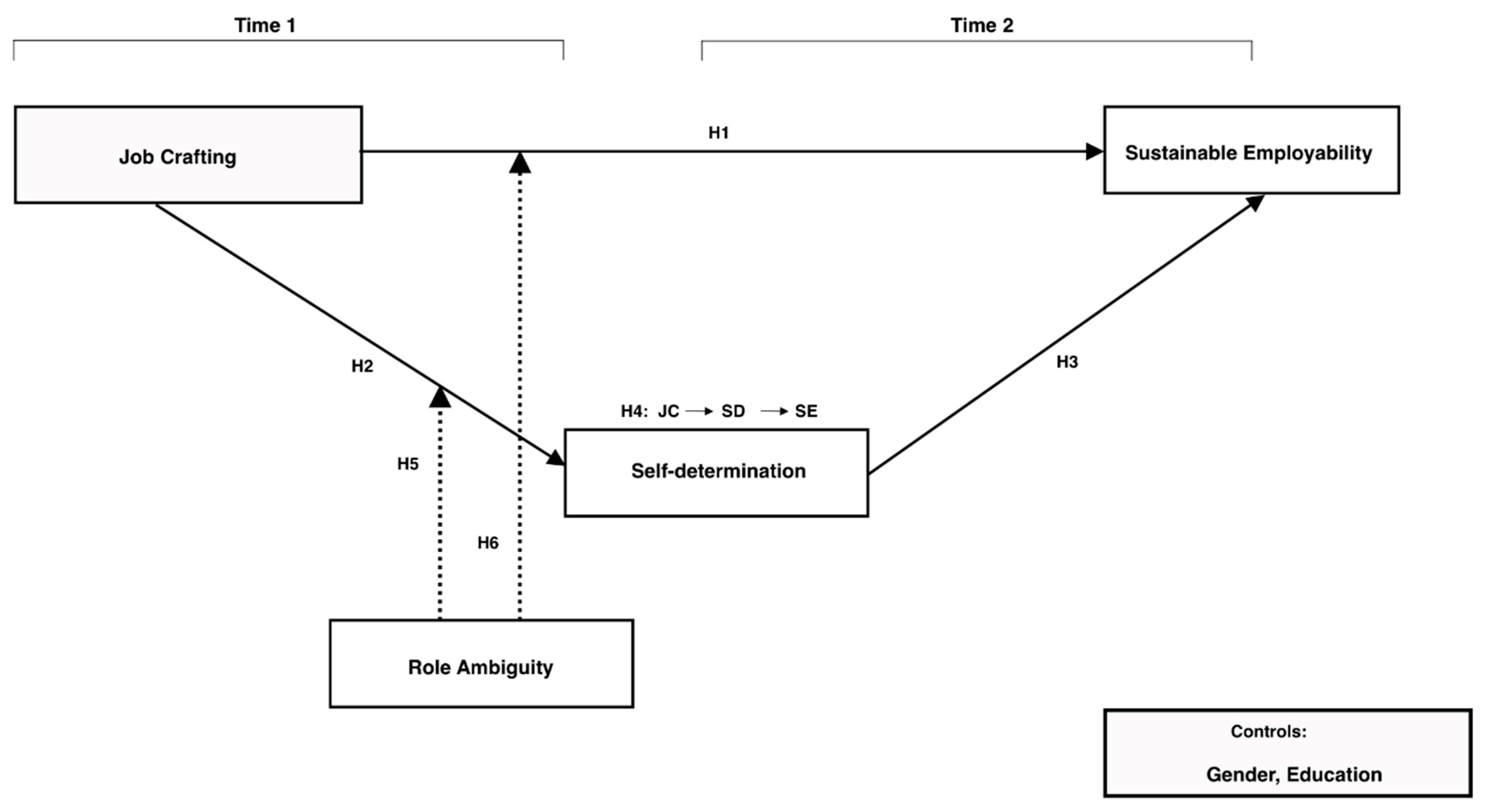

2.6. Conceptual Model

3. Method and Study Design

3.1. Sampling and Data Collection Procedures

3.2. Survey Instruments

3.2.1. Job Crafting

3.2.2. Self-Determination

3.2.3. Role Ambiguity

3.2.4. Sustainable Employability

3.3. Common Method Bias and Robustness Checks

3.4. Data Analysis

4. Analysis and Results

4.1. Measurement Model Evaluation

4.2. Structural Model and Hypothesis Testing (Direct Effects and Mediation)

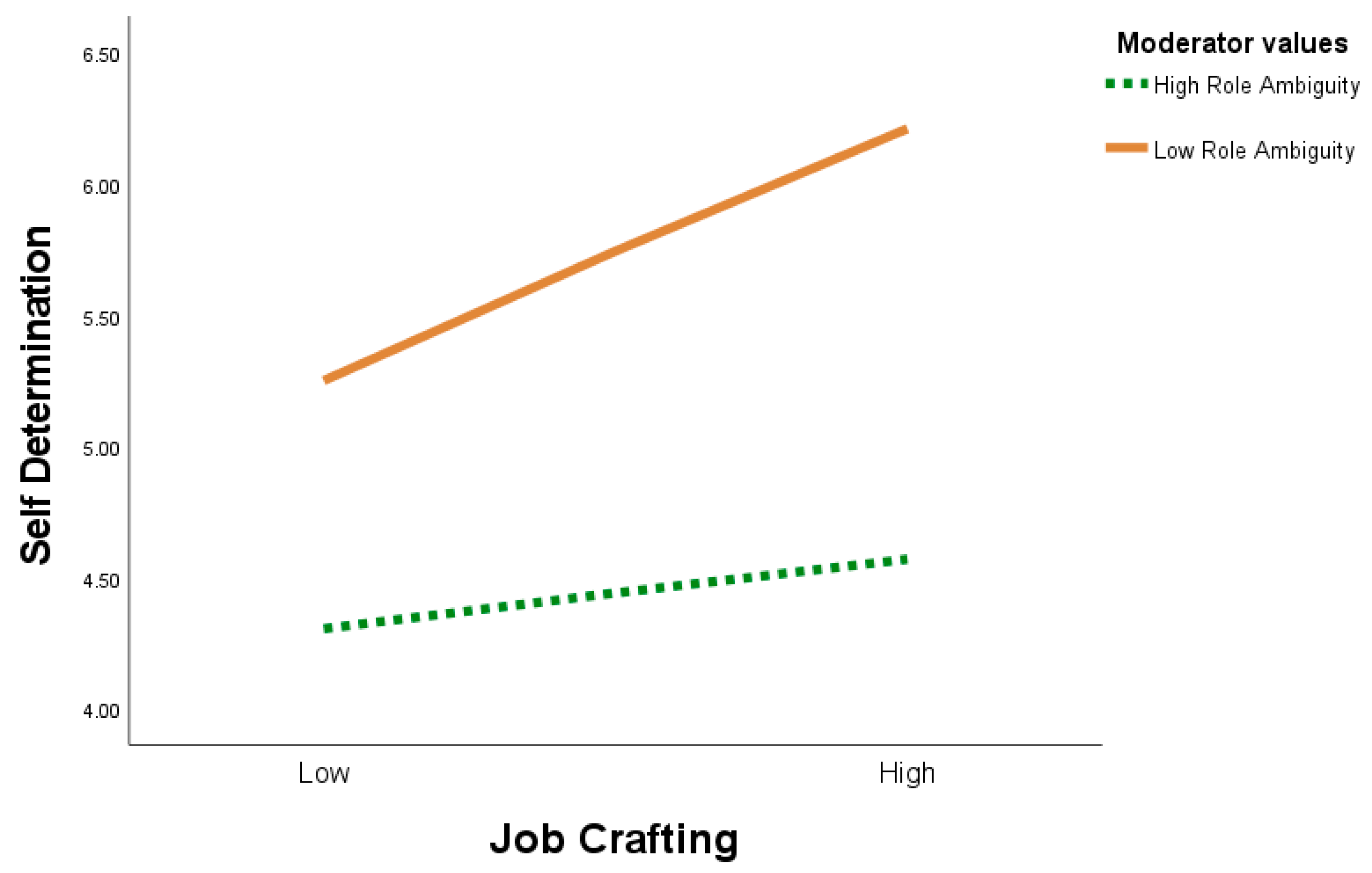

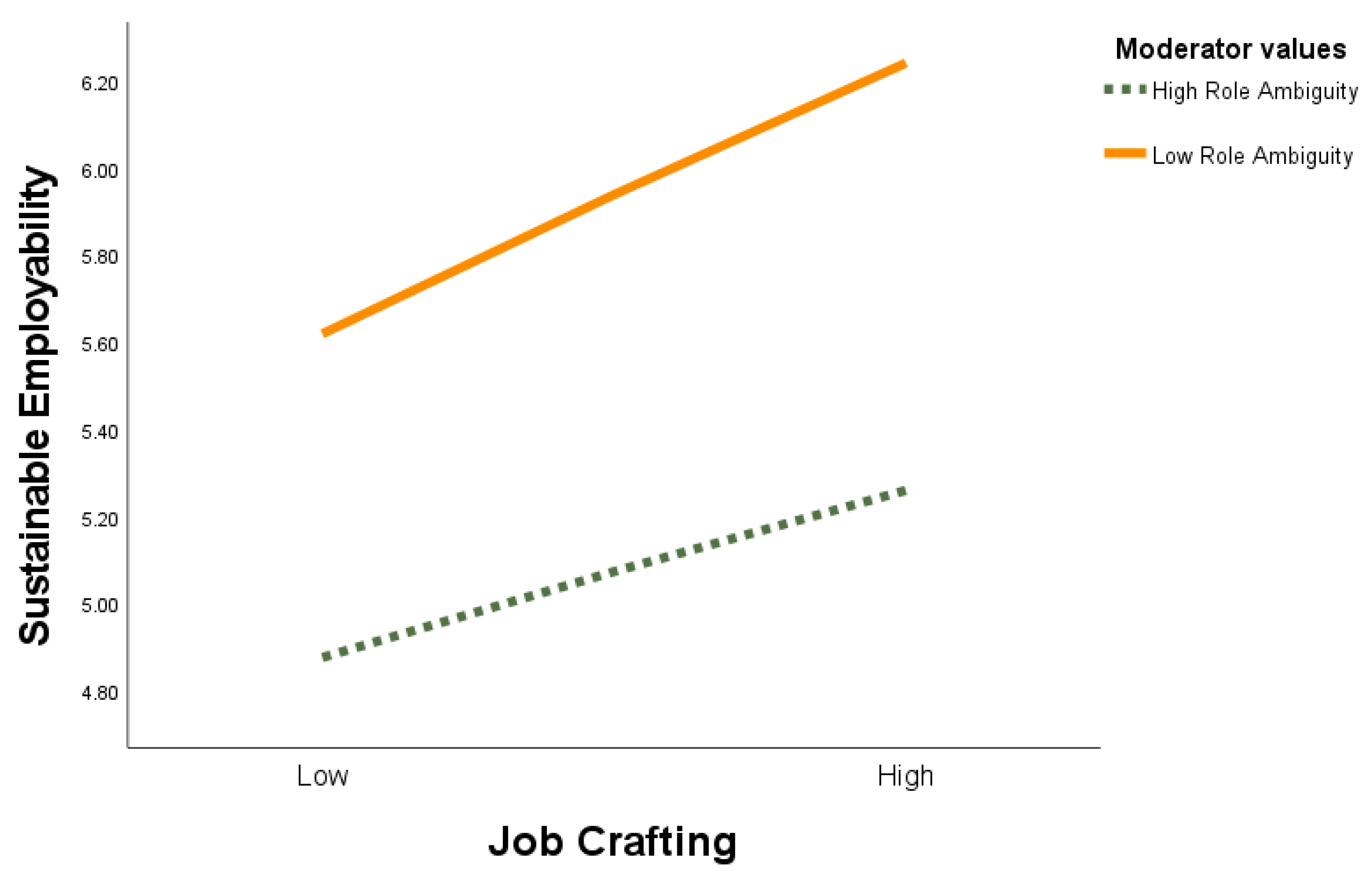

4.3. Moderation and Conditional Process Analysis (Role Ambiguity)

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

6.1. Theoretical Contributions

6.2. Practical Implications

6.3. Limitations and Directions for Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hazelzet, E.; Houkes, I.; Bosma, H.; de Rijk, A. Using Intervention Mapping to Develop ‘Healthy HR’ Aimed at Improving Sustainable Employability of Low-Educated Employees. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heijkants, C.H.; de Wind, A.; van Hooff, M.L.M.; Geurts, S.A.E.; Boot, C.R.L. Effectiveness of Team and Organisational Level Workplace Interventions Aimed at Improving Sustainable Employability of Aged Care Staff: A Systematic Review. J. Occup. Rehabil. 2023, 33, 37–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Duijnhoven, A.; de Vries, J.D.; Hulst, H.E.; van der Doef, M.P. An Organizational-Level Workplace Intervention to Improve Medical Doctors’ Sustainable Employability: Study Protocol for a Participatory Action Research Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2024, 21, 1561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arokiasamy, A.R.A.; Tan, R.S.-E.; Deng, P.; Krishnasamy, H.N.; Liu, M.; Wu, G.; Wider, W. A Bibliometric Deep-Dive: Uncovering Key Trends, Emerging Innovations, and Future Pathways in Sustainable Employability Research from 2014 to 2024. Discov. Sustain. 2024, 5, 450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, J.M.; Dutton, J.E.; Wrzesniewski, A. Job Crafting and Meaningful Work. In Purpose and Meaning in the Workplace; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2013; pp. 81–104. ISBN 978-1-4338-1314-6. [Google Scholar]

- Junça-Silva, A.; Silva, S.; Caetano, A. Job Crafting, Meaningful Work and Performance: A Moderated Mediation Approach of Presenteeism. SN Bus. Econ. 2022, 2, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oldham, G.R.; Fried, Y. Job Design Research and Theory: Past, Present and Future. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2016, 136, 20–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irfan, S.M.; Qadeer, F.; Sarfraz, M.; Abdullah, M.I. Relational Triggers of Job Crafting and Sustainable Employability: Examining a Moderated Mediation Model. Curr. Psychol. 2024, 43, 9773–9792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Qi, Z.; Zhu, J. Influence of Employee Job Crafting in Chinese Manufacturing Enterprises on Safety Innovation Performance: A Moderated Mediation Model. Chin. Manag. Stud. 2024, 19, 1243–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Javaid, M.; Liao, S.; Choi, M.; Kim, H.E. How and When Humble Leadership Influences Employee Adaptive Performance? The Roles of Self-Determination and Employee Attributions. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2024, 45, 377–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turek, D.; Klein, H.J.; Wojtczuk-Turek, A. Overcoming Organizational Constraints: The Role of Organizational Commitment and Job Crafting in Relation to Employee Performance. Eur. Manag. J. 2024, 42, 944–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, H.-Y.; Chen, C.-Y. Do Job Crafting and Leisure Crafting Enhance Job Embeddedness: A Moderated Mediation Model. J. Hosp. Tour. Insights 2024, 8, 1030–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkish, I.; Iyiola, K.; Alzubi, A.B.; Aljuhmani, H.Y. Does Digitization Lead to Sustainable Economic Behavior? Investigating the Roles of Employee Well-Being and Learning Orientation. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al’Ararah, K.; Çağlar, D.; Aljuhmani, H.Y. Mitigating Job Burnout in Jordanian Public Healthcare: The Interplay between Ethical Leadership, Organizational Climate, and Role Overload. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kubicek, B.; Paškvan, M.; Bunner, J. The Bright and Dark Sides of Job Autonomy. In Job Demands in a Changing World of Work: Impact on Workers’ Health and Performance and Implications for Research and Practice; Korunka, C., Kubicek, B., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 45–63. ISBN 978-3-319-54678-0. [Google Scholar]

- Kohli, M.K.; Priyadarshi, P. Attaining Sustainable Employment within Organizations: Uncovering the Impact of Job Crafting amid Contextual and Individual Influences. South Asian J. Bus. Stud. 2024, 14, 206–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irfan, D.S.; Qadeer, F. Employers’ Investments in Job Crafting for Sustainable Employability in Pandemic Situation Due to COVID-19: A Lens of Job Demands-Resources Theory. J. Bus. Econ. 2020, 12, 124–140. [Google Scholar]

- Awwad, R.I.; Aljuhmani, H.Y.; Hamdan, S. Examining the Relationships Between Frontline Bank Employees’ Job Demands and Job Satisfaction: A Mediated Moderation Model. Sage Open 2022, 12, 21582440221079880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkhweildi, M.; Vetbuje, B.; Alzubi, A.B.; Aljuhmani, H.Y. Leading with Green Ethics: How Environmentally Specific Ethical Leadership Enhances Employee Job Performance Through Communication and Engagement. Sustainability 2025, 17, 7923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Self-Determination Theory and the Facilitation of Intrinsic Motivation, Social Development, and Well-Being. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olafsen, A.H.; Marescaux, B.P.C.; Kujanpää, M. Crafting for Autonomy, Competence, and Relatedness: A Self-determination Theory Model of Need Crafting at Work. Appl. Psychol. 2025, 74, e12570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M. Psychological Needs and the Facilitation of Integrative Processes. J. Personal. 1995, 63, 397–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Self-Determination Theory: Basic Psychological Needs in Motivation, Development, and Wellness; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2017; p. 756. ISBN 978-1-4625-2876-9. [Google Scholar]

- Biddle, B.J. Recent Developments in Role Theory. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 1986, 12, 67–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowling, N.A.; Khazon, S.; Alarcon, G.M.; Blackmore, C.E.; Bragg, C.B.; Hoepf, M.R.; Barelka, A.; Kennedy, K.; Wang, Q.; Li, H. Building Better Measures of Role Ambiguity and Role Conflict: The Validation of New Role Stressor Scales. Work Stress 2017, 31, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzo, J.R.; House, R.J.; Lirtzman, S.I. Role Conflict and Ambiguity in Complex Organizations. Adm. Sci. Q. 1970, 15, 150–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillet, N.; Fouquereau, E.; Lafrenière, M.-A.K.; Huyghebaert, T. Examining the Roles of Work Autonomous and Controlled Motivations on Satisfaction and Anxiety as a Function of Role Ambiguity. J. Psychol. 2016, 150, 644–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yokouchi, N. Moderating Effects of Self-Construal on the Associations of Workload and Role Ambiguity with Psychological Distress: A Cross-Sectional and Prospective Study in a Japanese Workplace. J. Workplace Behav. Health 2025, 40, 369–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, J.W. Job Autonomy, Role Ambiguity, and Procedural Justice: A Multi-Conditional Process Model of Change-Oriented Organizational Citizenship Behavior in Public Organizations. Rev. Public Pers. Adm. 2025, 45, 145–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudolph, C.W.; Katz, I.M.; Lavigne, K.N.; Zacher, H. Job Crafting: A Meta-Analysis of Relationships with Individual Differences, Job Characteristics, and Work Outcomes. J. Vocat. Behav. 2017, 102, 112–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wrzesniewski, A.; Dutton, J.E. Crafting a Job: Revisioning Employees as Active Crafters of Their Work. AMR 2001, 26, 179–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tims, M.; Bakker, A.B.; Derks, D. The Impact of Job Crafting on Job Demands, Job Resources, and Well-Being. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2013, 18, 230–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tims, M.; Bakker, A.B. Job Crafting: Towards a New Model of Individual Job Redesign: Original Research. SA J. Ind. Psychol. 2010, 36, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baik, S.J.; Song, H.-D.; Hong, A.J. Craft Your Job and Get Engaged: Sustainable Change-Oriented Behavior at Work. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akkermans, J.; Tims, M. Crafting Your Career: How Career Competencies Relate to Career Success via Job Crafting. Appl. Psychol. 2017, 66, 168–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E. Job Demands–Resources Theory: Taking Stock and Looking Forward. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2017, 22, 273–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vanbelle, E.; Broeck, A.V.D.; Witte, H.D. Job Crafting: Autonomy and Workload as Antecedents and the Willingness to Continue Working until Retirement Age as a Positive Outcome. Psihol. Resur. Um. 2017, 15, 25–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, T.-K.; Wang, C.-H.; Tian, M.; Lin, M.; Liu, W.-H. How to Prevent Stress in the Workplace by Emotional Regulation? The Relationship Between Compulsory Citizen Behavior, Job Engagement, and Job Performance. Sage Open 2022, 12, 21582440221105483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Beehr, T.A. Job Crafting Mediates How Empowering Leadership and Employees’ Core Self-Evaluations Predict Favourable and Unfavourable Outcomes. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2020, 29, 126–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagné, M.; Parker, S.K.; Griffin, M.A.; Dunlop, P.D.; Knight, C.; Klonek, F.E.; Parent-Rocheleau, X. Understanding and Shaping the Future of Work with Self-Determination Theory. Nat. Rev. Psychol. 2022, 1, 378–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coetzee, M.; Engelbrecht, L. How Employability Attributes Mediate the Link Between Knowledge Workers’ Career Adaptation Concerns and Their Self-Perceived Employability. Psychol. Rep. 2020, 123, 1005–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Harten, J.; Knies, E.; Leisink, P. Employer’s Investments in Hospital Workers’ Employability and Employment Opportunities. Pers. Rev. 2016, 45, 84–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, D.B.; Bhatt, V.; Mathur, S.; Badge, J.; Sharma, A. Role of ELT and Life Skills in Developing Employability Skills through Integrating Self Determination and Experiential Learning. Austrian J. Stat. 2024, 53, 53–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekiguchi, T.; Li, J.; Hosomi, M. Predicting Job Crafting From the Socially Embedded Perspective: The Interactive Effect of Job Autonomy, Social Skill, and Employee Status. J. Appl. Behav. Sci. 2017, 53, 470–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilic, E.; Kitapci, H. Cognitive Job Crafting: An Intervening Mechanism between Intrinsic Motivation and Affective Well-Being. Manag. Res. Rev. 2022, 46, 1043–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoeber, J.; Damian, L.E. Perfectionism in Employees: Work Engagement, Workaholism, and Burnout. In Perfectionism, Health, and Well-Being; Sirois, F.M., Molnar, D.S., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 265–283. ISBN 978-3-319-18582-8. [Google Scholar]

- Vansteenkiste, M.; Ryan, R.M.; Soenens, B. Basic Psychological Need Theory: Advancements, Critical Themes, and Future Directions. Motiv. Emot. 2020, 44, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parenrengi, S.; Jamaluddin; Aisyah, S.; Mahande, R.D.; Setialaksana, W. Unlocking Employability: The Power of Autonomy, Competence and Relatedness in Work-Based Learning Engagement and Motivation. High. Educ. Ski. Work-Based Learn. 2025, 15, 775–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuzawa, Y.; Yaeda, J. The Process of Cultivating Autonomous Working Motivation in Supported Employment Program Users in Psychiatry. J. Psychosoc. Rehabil. Ment. Health 2024, 11, 55–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niessen, C.; Lang, J.W.B. Cognitive Control Strategies and Adaptive Performance in a Complex Work Task. J. Appl. Psychol. 2021, 106, 1586–1599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahn, R.L.; Wolfe, D.M.; Quinn, R.P.; Snoek, J.D.; Rosenthal, R.A. Organizational Stress: Studies in Role Conflict and Ambiguity; John Wiley: Oxford, UK, 1964; p. 470. [Google Scholar]

- Cordes, C.L.; Dougherty, T.W. A Review and an Integration of Research on Job Burnout. AMR Acad. Manag. Rev. 1993, 18, 621–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilotta, I.; Cheng, S.; Davenport, M.K.; King, E. Using the Job Demands-Resources Model to Understand and Address Employee Well-Being during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Ind. Organ. Psychol. 2021, 14, 267–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, G.X.; Petrou, P.; Bakker, A.B.; Born, M.P. Can Job Stressors Activate Amoral Manipulation? A Weekly Diary Study. J. Bus. Ethics 2023, 185, 467–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swieai, W.; Alzubi, A.B.; Aljuhmani, H.Y.; Topal, H. Unpacking the Role of Proactive Personality in Enhancing Safety Behavior: A Moderated Mediation Model in Turkish Healthcare Organizations. J. Health Organ. Manag. 2025, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, C.M.; Pham, B.T.; Chau, D.T.L. Unpacking the Unintended Consequences of Socially Responsible Human Resource Management: A Role Stress Perspective. Int. J. Organ. Anal. 2024, 33, 1633–1645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dierdorff, E.C.; Jensen, J.M. Crafting in Context: Exploring When Job Crafting Is Dysfunctional for Performance Effectiveness. J. Appl. Psychol. 2018, 103, 463–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, T.-Y.; Chung, P.F.; Liao, H.-Y.; Hu, P.-Y.; Yeh, Y.-J. Role Ambiguity and Economic Hardship as the Moderators of the Relation between Abusive Supervision and Job Burnout: An Application of Uncertainty Management Theory. J. Gen. Psychol. 2019, 146, 365–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mwakyusa, J.R.P.; Mcharo, E.W. Role Ambiguity and Role Conflict Effects on Employees’ Emotional Exhaustion in Healthcare Services in Tanzania. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2024, 11, 2326237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Clercq, D.; Pereira, R. A Lack of Clarity, a Lack of OCB: The Detrimental Effects of Role Ambiguity, Through Procedural Injustice, and the Mitigating Roles of Relational Resources. J. Afr. Bus. 2025, 26, 284–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rihal, J.; Alzubi, A.; Aljuhmani, H.Y.; Berberoğlu, A. From Ethics to Ecology: How Ethical Leadership Drives Environmental Performance through Green Organizational Identity and Culture. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0336608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ageli, R.; Alzubi, A.B.; Aljuhmani, H.Y.; Iyiola, K. How and When Entrepreneurial Leadership Drives Sustainable Bank Performance: Unpacking the Roles of Employee Creativity and Innovation-Oriented Climate. Sustainability 2025, 17, 9259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dillman, D.A.; Smyth, J.D.; Christian, L.M. Internet, Mail, and Mixed-Mode Surveys: The Tailored Design Method, 3rd ed.; John Wiley & Sons Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2008; ISBN 978-0-471-69868-5. [Google Scholar]

- Arhim, A.; Alzubi, A.; Iyiola, K.; Banje, F.U. Unpacking the Relationship Between Empowerment Leadership and Electricity Worker’s Unsafe Behavior: A Multi-Moderated Mediation Approach. Sustainability 2024, 16, 10732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humayun, S.; Saleem, S.; Azeem, M.U.; Murtaza, G.; Haq, I.U. Paradigm Shift in Sustained Employability: Relevance of Workaholism, Job Insecurity, Job Crafting, and Presenteeism. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2024, 35, 2705–2741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.-Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common Method Biases in Behavioral Research: A Critical Review of the Literature and Recommended Remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do, H.; Chu, L.X.; Shipton, H. How and When AI-Driven HRM Promotes Employee Resilience and Adaptive Performance: A Self-Determination Theory. J. Bus. Res. 2025, 192, 115279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alarebi, A.; Vetbuje, B.; Alzubi, A.B.; Iyiola, K. Using Family Work Balance to Reduce Unsafe Behavior Among New-Generation Construction Workers from the Turkish Context. Buildings 2026, 16, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brislin, R.W. The Wording and Translation of Research Instruments. In Field Methods in Cross-Cultural Research; Cross-Cultural Research and Methodology Series; Sage Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1986; Volume 8, pp. 137–164. ISBN 978-0-8039-2549-6. [Google Scholar]

- Ayouz, H.; Alzubi, A.; Iyiola, K. Using Benevolent Leadership to Improve Safety Behaviour in the Construction Industry: A Moderated Mediation Model of Safety Knowledge and Safety Training and Education. Int. J. Occup. Saf. Ergon. 2024, 31, 167–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aljuhmani, H.Y.; Emeagwali, O.L.; Ababneh, B. The Relationships between CEOs’ Psychological Attributes, Top Management Team Behavioral Integration and Firm Performance. Int. J. Organ. Theory Behav. 2021, 24, 126–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tims, M.; Bakker, A.B.; Derks, D. Development and Validation of the Job Crafting Scale. J. Vocat. Behav. 2012, 80, 173–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spreitzer, G.M. Psychological Empowerment in the Workplace: Dimensions, Measurement, and Validation. AMJ 1995, 38, 1442–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akkermans, J.; Brenninkmeijer, V.; Huibers, M.; Blonk, R.W.B. Competencies for the Contemporary Career: Development and Preliminary Validation of the Career Competencies Questionnaire. J. Career Dev. 2013, 40, 245–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oude Hengel, K.M.; Blatter, B.M.; Geuskens, G.A.; Koppes, L.L.J.; Bongers, P.M. Factors Associated with the Ability and Willingness to Continue Working until the Age of 65 in Construction Workers. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health 2012, 85, 783–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsafadi, Y.; Aljuhmani, H.Y. The Influence of Entrepreneurial Innovations in Building Competitive Advantage: The Mediating Role of Entrepreneurial Thinking. Kybernetes 2023, 53, 4051–4073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmering, M.J.; Fuller, C.M.; Richardson, H.A.; Ocal, Y.; Atinc, G.M. Marker Variable Choice, Reporting, and Interpretation in the Detection of Common Method Variance: A Review and Demonstration. Organ. Res. Methods 2015, 18, 473–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kefas, H.I.; Nat, M.C.; Iyiola, K. Satisfaction with Human Resource Practices, Job Dedication and Job Performance: The Role of Incentive Gamification. Kybernetes 2024, ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schill, M.; Fosse-Gomez, M.-H. Consumer Climate Change Engagement in Fostering Well-Being and Mitigation Behaviors. J. Bus. Res. 2025, 198, 115490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljuhmani, H.Y.; Ababneh, B.; Emeagwali, L.; Elrehail, H. Strategic Stances and Organizational Performance: Are Strategic Performance Measurement Systems the Missing Link? Asia-Pac. J. Bus. Adm. 2022, 16, 282–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach, 3rd ed.; Methodology in the Social Sciences; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA; London, UK, 2022; ISBN 978-1-4625-4903-0. [Google Scholar]

- Slil, E.; Iyiola, K.; Alzubi, A.; Aljuhmani, H.Y. Impact of Safety Leadership and Employee Morale on Safety Performance: The Moderating Role of Harmonious Safety Passion. Buildings 2025, 15, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.; Iyiola, K.; Alzubi, A.; Aljuhmani, H.Y. Using Safety-Specific Transformational Leadership to Improve Safety Behavior Among Construction Workers: Exploring the Role of Knowledge Sharing and Psychological Safety. Buildings 2025, 15, 3340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F.; Rockwood, N.J. Regression-Based Statistical Mediation and Moderation Analysis in Clinical Research: Observations, Recommendations, and Implementation. Behav. Res. Ther. 2017, 98, 39–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.C.; Gerbing, D.W. Structural Equation Modeling in Practice: A Review and Recommended Two-Step Approach. Psychol. Bull. 1988, 103, 411–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff Criteria for Fit Indexes in Covariance Structure Analysis: Conventional Criteria versus New Alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. A Multidiscip. J. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Yi, Y.; Phillips, L.W. Assessing Construct Validity in Organizational Research. Adm. Sci. Q. 1991, 36, 421–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collier, J. Applied Structural Equation Modeling Using AMOS: Basic to Advanced Techniques, 1st ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2020; ISBN 978-0-367-43526-4. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis, 7th ed.; Pearson: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2009; ISBN 978-0-13-813263-7. [Google Scholar]

- Fuller, C.M.; Simmering, M.J.; Atinc, G.; Atinc, Y.; Babin, B.J. Common Methods Variance Detection in Business Research. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 3192–3198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, M.; Lomax, R.G. The Effect of Varying Degrees of Nonnormality in Structural Equation Modeling. Struct. Equ. Model. A Multidiscip. J. 2005, 12, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iyiola, K.; Rjoub, H. Using Conflict Management in Improving Owners and Contractors Relationship Quality in the Construction Industry: The Mediation Role of Trust. Sage Open 2020, 10, 2158244019898834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iyiola, K.; Alzubi, A.; Dappa, K. The Influence of Learning Orientation on Entrepreneurial Performance: The Role of Business Model Innovation and Risk-Taking Propensity. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2023, 9, 100133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiken, L.S.; West, S.G. Multiple Regression: Testing and Interpreting Interactions; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 1991; ISBN 978-0-7619-0712-1. [Google Scholar]

- Jaganjac, J.; Nikolić, J.L.; Lazarević, S.; Jaganjac, J.; Nikolić, J.L.; Lazarević, S. The Importance of Green Human Resource Management Practices for Sustainable Organizational Development: Evidence from Serbia and Bosnia and Herzegovina. J. East Eur. Manag. Stud. 2024, 29, 157–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Jiang, H.; Jin, T. Leader-Member Exchange and Organisational Citizenship Behaviour: The Mediating and Moderating Effects of Role Ambiguity. J. Psychol. Afr. 2020, 30, 17–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Heuvel, M.; Demerouti, E.; Peeters, M.C.W. The Job Crafting Intervention: Effects on Job Resources, Self-Efficacy, and Affective Well-Being. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2015, 88, 511–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Demographic Details (n = 989) | Category | Frequency | Proportion (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 524 | 52.98 |

| Female | 465 | 47.02 | |

| Educational level | High school diploma | 201 | 20.32 |

| Bachelor degree | 559 | 56.52 | |

| Master degree | 226 | 22.86 | |

| Doctoral degree | 3 | 0.30 | |

| Marital status | Married | 523 | 52.88 |

| Single | 440 | 44.49 | |

| Prefer not to say | 26 | 2.63 | |

| Professional characteristics | Banking | 99 | 10.01 |

| Retailing/trade | 95 | 9.61 | |

| Public administration | 89 | 8.99 | |

| Manufacturing | 187 | 18.91 | |

| Real estate/construction | 53 | 5.36 | |

| Service | 101 | 10.21 | |

| Transportation/logistics | 69 | 6.98 | |

| Healthcare | 184 | 18.60 | |

| Agriculture | 55 | 5.57 | |

| Others | 57 | 5.76 |

| Variable Items | Loading | α | AVE | CR | Normal Distribution | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kurtosis | Skewness | |||||

| Job crafting (JC) | 0.957 | 0.525 | 0.957 | |||

| JC1 | 0.717 | −0.708 | 0.247 | |||

| JC2 | 0.752 | −0.563 | −0.285 | |||

| JC3 | 0.656 | −0.972 | 0.958 | |||

| JC4 | 0.737 | −0.487 | −0.090 | |||

| JC5 | 0.669 | −0.741 | 0.562 | |||

| JC6 | 0.669 | −0.875 | 0.901 | |||

| JC7 | 0.643 | −1.459 | 1.474 | |||

| JC8 | 0.635 | −0.509 | −0.132 | |||

| JC9 | 0.702 | −0.678 | 0.275 | |||

| JC10 | 0.736 | −1.128 | 1.913 | |||

| JC11 | 0.760 | −0.814 | 0.430 | |||

| JC12 | 0.721 | −1.065 | 1.489 | |||

| JC13 | 0.742 | −0.973 | 0.993 | |||

| JC14 | 0.788 | −0.790 | 0.292 | |||

| JC15 | 0.761 | −0.571 | 0.019 | |||

| JC16 | 0.788 | −0.691 | 0.337 | |||

| JC17 | 0.749 | −0.672 | 0.119 | |||

| JC18 | 0.742 | −0.823 | 0.424 | |||

| JC19 | 0.746 | −0.904 | 0.646 | |||

| JC20 | 0.750 | −0.678 | 0.067 | |||

| Self-determination (SD) | 0.945 | 0.852 | 0.945 | |||

| SD1 | 0.920 | −0.724 | 0.276 | |||

| SD2 | 0.925 | −0.674 | 0.306 | |||

| SD3 | 0.924 | −0.690 | 0.385 | |||

| Role ambiguity (RA) | 0.919 | 0.696 | 0.919 | |||

| RA1 | 0.886 | −0.645 | 0.194 | |||

| RA2 | 0.903 | −0.629 | 0.178 | |||

| RA3 | 0.823 | −0.569 | −0.170 | |||

| RA4 | 0.720 | −0.836 | 0.449 | |||

| RA5 | 0.827 | −0.610 | −0.123 | |||

| Sustainable employability (SE) | 0.961 | 0.715 | 0.962 | |||

| SE1 | 0.806 | −0.566 | −0.454 | |||

| SE2 | 0.827 | −0.554 | −0.561 | |||

| SE3 | 0.864 | −0.713 | 0.293 | |||

| SE4 | 0.894 | −0.524 | −0.157 | |||

| SE5 | 0.816 | −0.306 | −0.527 | |||

| SE6 | 0.849 | −0.646 | 0.208 | |||

| SE7 | 0.846 | −0.544 | −0.374 | |||

| SE8 | 0.809 | −0.245 | −0.544 | |||

| SE9 | 0.872 | −0.444 | −0.565 | |||

| SE10 | 0.866 | −0.545 | −0.189 | |||

| Goodness of fit results: CMIN/DF = 2.229, RMSEA = 0.057, GFI = 0.912, CFI = 0.938, NFI = 0.932, TLI = 0.926 | ||||||

| Constructs | M | Std. | JC | SD | RA | SE | Education | Gender |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| JC | 5.613 | 0.847 | (0.725) | |||||

| SD | 5.280 | 1.211 | 0.643 ** | (0.923) | ||||

| RA | 5.428 | 1.044 | 0.585 ** | 0.693 ** | (0.834) | |||

| SE | 5.587 | 0.938 | 0.555 ** | 0.613 ** | 0.602 ** | (0.845) | ||

| Education | - | - | 0.073 | 0.078 | 0.046 | 0.036 | - | |

| Gender | - | - | −0.091 | −0.091 | −0.029 | −0.029 | −0.042 | - |

| Predictor | Model 1: Self Determination | Model 2: Sustainable Employability | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Relationships | β | S.E. | t-Value | p-Value | 95% CI | β | S.E. | t-Value | p-Value | 95% CI |

| Constant | 0.121 | 0.147 | 0.820 | ns | [−0.168,0.409] | 0.875 | 0.086 | 10.132 | *** | [0.706,1.045] |

| JC | 0.919 | 0.025 | 35.461 | *** | [0.868,0.970] | 0.558 | 0.019 | 28.079 | *** | [0.518,0.596] |

| SD | 0.299 | 0.014 | 21.589 | *** | [0.273,0.327] | |||||

| R2 | 0.413 | 0.660 | ||||||||

| JC → SD → SE | 0.275 | 0.018 | - | - | [0.242,0.311] | |||||

| Paths | β | S.E. | t-Value | p-Value | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||||

| Model 1: Mediator construct model (Self-determination) | ||||||

| Constant | 5.154 | 0.024 | 213.172 | *** | 5.107 | 5.202 |

| JC → SD | 0.373 | 0.038 | 9.914 | *** | 0.299 | 0.447 |

| RA → SD | 0.586 | 0.031 | 19.160 | 0.526 | 0.646 | |

| JC × RA → SD | 0.181 | 0.020 | 8.967 | *** | 0.141 | 0.220 |

| Education → SD | 0.027 | 0.009 | 0.319 | ns | −0.018 | 0.025 |

| Gender → SD | −0.010 | 0.011 | −0.820 | ns | −0.019 | 0.015 |

| The conditional direct effect of JC on SD at different levels of RA | ||||||

| −1SD (Low) | 0.549 | 0.043 | 12.836 | *** | 0.465 | 0.633 |

| +1SD (High) | 0.151 | 0.045 | 3.388 | *** | 0.064 | 0.239 |

| R2 = 0.527 *** | ||||||

| Model 2: Outcome construct model (Sustainable employability) | ||||||

| Constant | 4.590 | 0.074 | 62.391 | *** | 4.991 | 5.222 |

| JC → SE | 0.295 | 0.023 | 12.910 | *** | 0.254 | 0.377 |

| SD → SE | 0.181 | 0.014 | 12.899 | *** | 0.389 | 0.483 |

| RA → SE | 0.391 | 0.019 | 19.698 | *** | 0.294 | 0.395 |

| JC × RA → SE | 0.062 | 0.012 | 5.071 | *** | 0.094 | 0.187 |

| Education → SE | 0.039 | 0.013 | 1.101 | ns | −0.006 | 0.024 |

| Gender → SE | 0.025 | 0.009 | 0.915 | ns | −0.003 | 0.019 |

| The conditional direct effect of JC on SE at different levels of RA | ||||||

| −1SD (Low) | 0.219 | 0.026 | 13.442 | *** | 0.303 | 0.407 |

| +1SD (High) | 0.450 | 0.026 | 8.278 | *** | 0.167 | 0.271 |

| The conditional indirect effects of JC on SE through SD at the different levels of RA | ||||||

| 0.099 | 0.015 | 0.073 | 0.130 | |||

| 0.027 | 0.010 | 0.167 | 0.271 | |||

| Index of moderated mediation | ||||||

| 0.033 | 0.055 | 0.023 | 0.044 | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Afnek, R.; Khadem, A. Crafting Your Employability: How Job Crafting Relates to Sustainable Employability Under the Self-Determination Theory and Role Theory. Sustainability 2026, 18, 979. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18020979

Afnek R, Khadem A. Crafting Your Employability: How Job Crafting Relates to Sustainable Employability Under the Self-Determination Theory and Role Theory. Sustainability. 2026; 18(2):979. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18020979

Chicago/Turabian StyleAfnek, Ramdan, and Amir Khadem. 2026. "Crafting Your Employability: How Job Crafting Relates to Sustainable Employability Under the Self-Determination Theory and Role Theory" Sustainability 18, no. 2: 979. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18020979

APA StyleAfnek, R., & Khadem, A. (2026). Crafting Your Employability: How Job Crafting Relates to Sustainable Employability Under the Self-Determination Theory and Role Theory. Sustainability, 18(2), 979. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18020979

_Li.png)