Sustainable Mixed-Traffic Micro-Modeling in Intelligent Connected Environments: Construction and Simulation Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

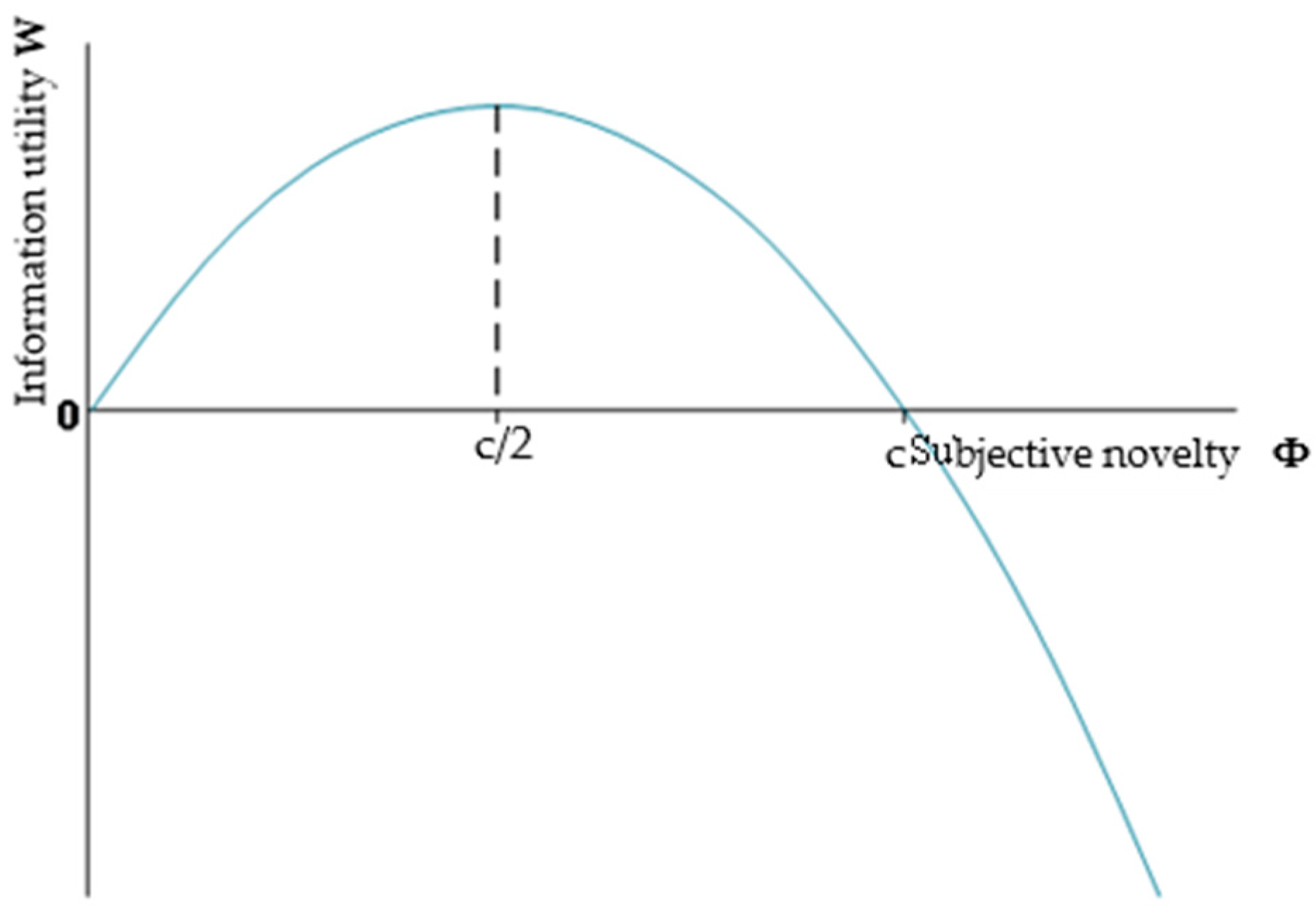

- An improved IDM car-following model integrating fear degree and reaction time is proposed. Building upon the traditional IDM, a “fear degree” parameter reflecting drivers’ psychological response to connected and automated vehicles is introduced and quantified using the Wundt psychological curve. Additionally, the reaction times of human-driven vehicles and connected and automated vehicles under different car-following modes (HDC, ACC, CACC) are differentiated, making microscopic car-following behavior more aligned with actual driving psychology and vehicle characteristics.

- (2)

- A multi-lane lane-changing rule system categorized by vehicle type is constructed. To address the fundamental differences in lane-changing decision logic between connected and automated vehicles and human-driven vehicles, this paper modifies the classical two-lane cellular automata model (TCAM) by categorizing vehicle types. It clarifies distinctions in lane-changing motivation judgment, safety condition assessment, and lane-changing probability settings, and further extends the framework to three-lane scenarios, systematically depicting the cooperative and competitive lane-changing behaviors of vehicles in mixed traffic flow.

- (3)

- Multi-dimensional simulation and comprehensive evaluation of mixed traffic flow characteristics are conducted. Using the Matlab platform, simulation environments for single-lane, double-lane, and three-lane scenarios are constructed. The impact of connected and automated vehicle penetration rates on traffic flow efficiency, safety, and stability is comprehensively analyzed based on multiple indicators such as fundamental diagrams, lane-changing frequency, congestion degree, and speed fluctuations, providing a quantitative basis for formulating traffic control strategies in connected and automated environments.

2. Construction of Single-Lane Mixed Traffic Flow Model in Intelligent Connected Environment

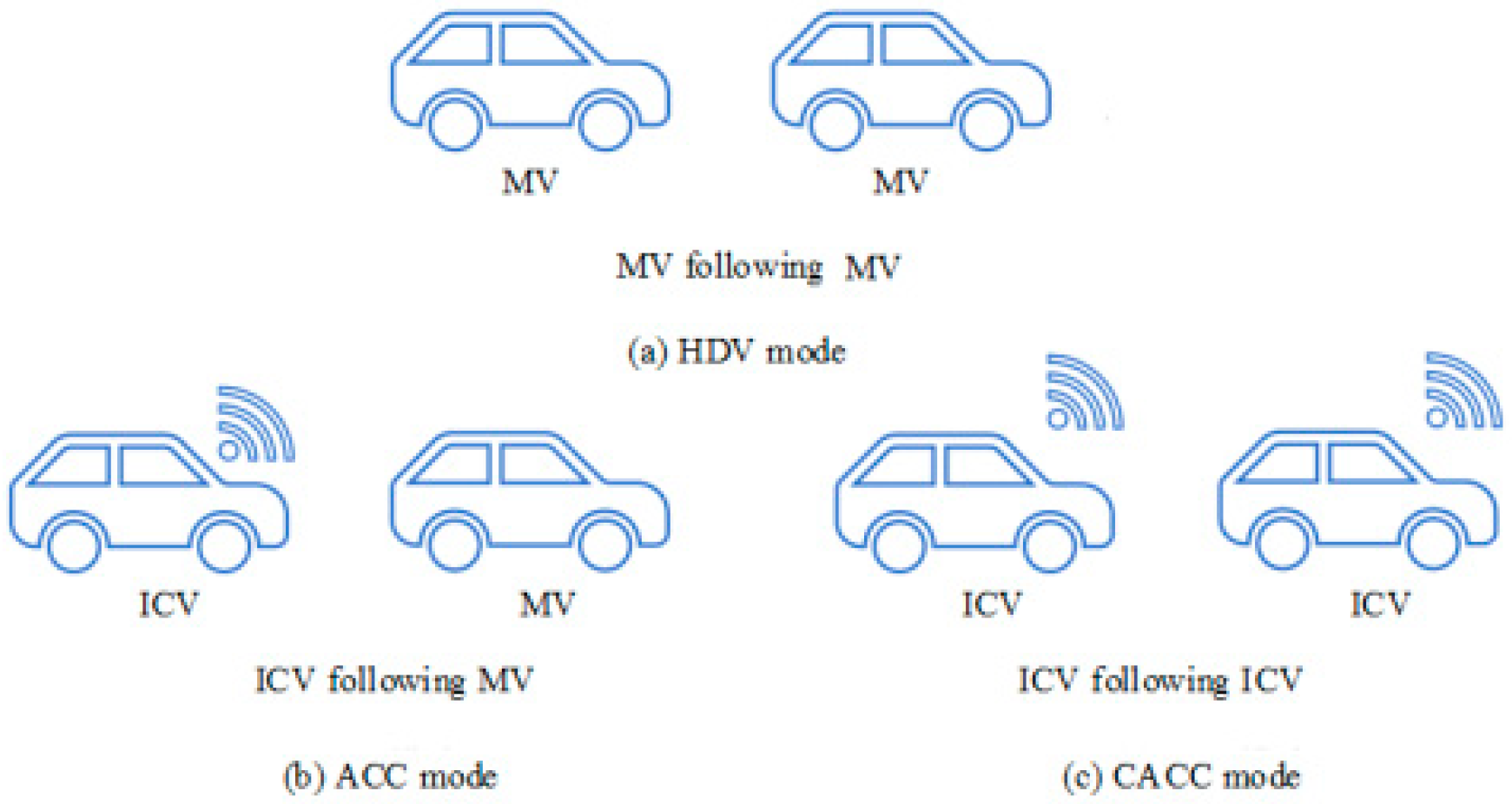

2.1. Analysis of Car-Following Mode

2.2. Establishment of IDM Based on Fear Level and Reaction Time

- (1)

- HDC mode

- (2)

- ACC mode

2.3. Establishment of IDM Following Rules Based on Fear Level and Reaction Time

3. Construction of Dual-Lane Mixed Traffic Flow Model in Intelligent Connected Environment

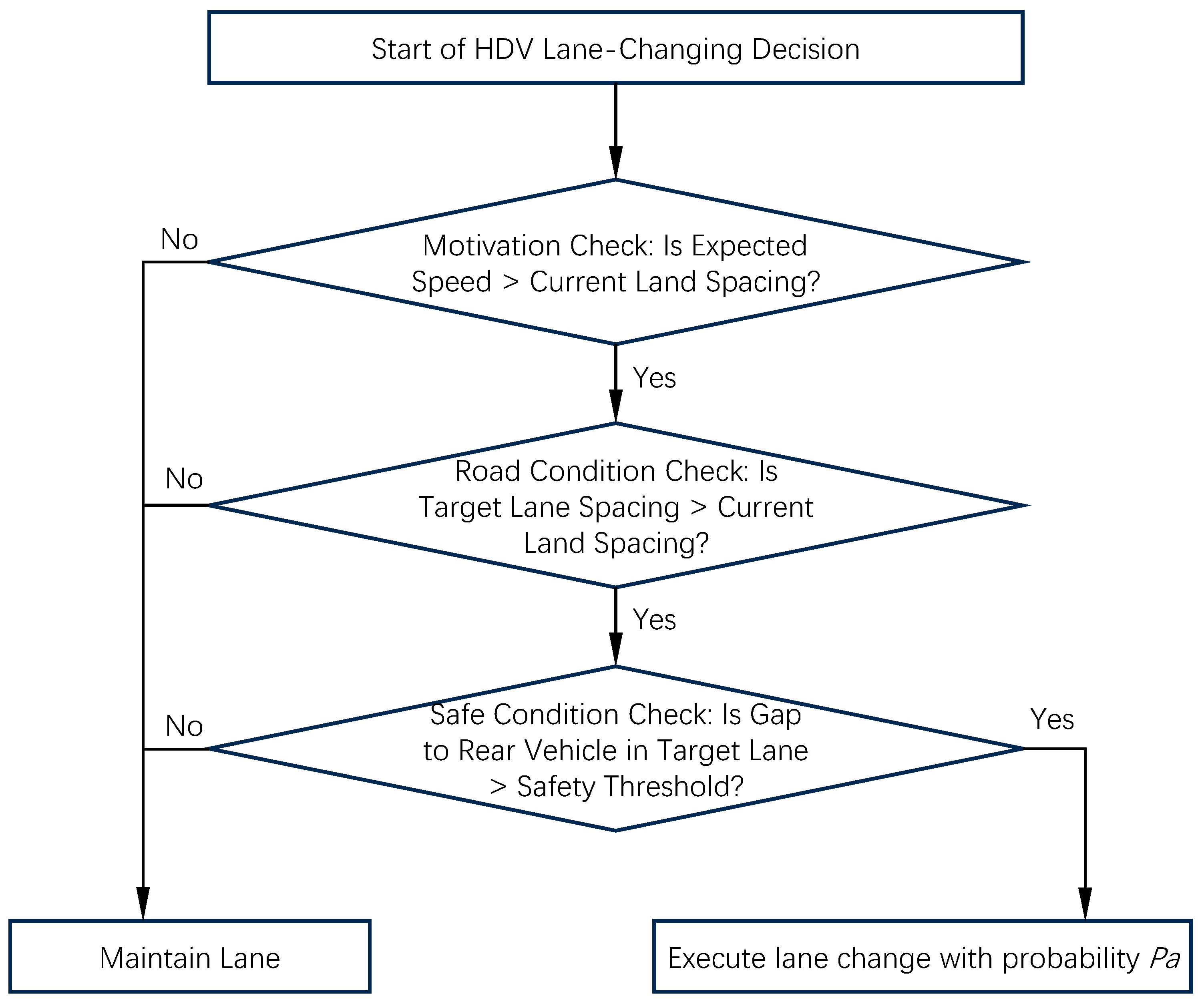

3.1. Rules for Changing Lanes for HDVs

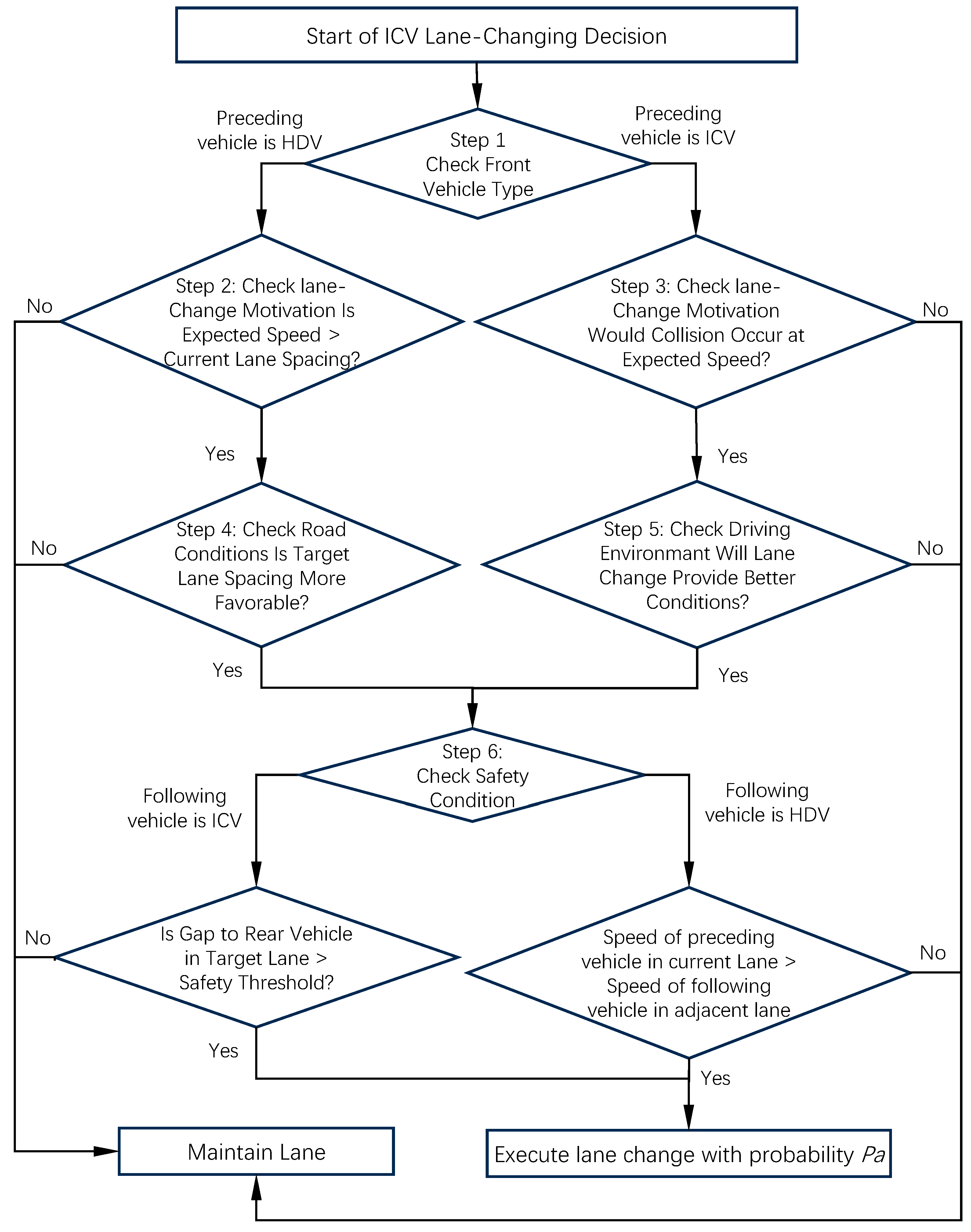

3.2. Intelligent Connected Vehicle Lane-Changing Rules

- (1)

- By analyzing the following mode in the intelligent connected environment, it can be concluded that when both the preceding and following vehicles are ICV, the driving behavior change information of the preceding vehicle can be transmitted to the following vehicle through vehicle-to-vehicle communication. Therefore, when in CACC following mode, the following vehicle can travel at a higher speed and maintain a smaller distance from the preceding vehicle. In this case, even if the distance between the preceding and following vehicles is less than the expected speed of the target vehicle, the target vehicle will not have the intention to change lanes. Therefore, when the target vehicle is an intelligent connected vehicle, the conditions for the generation of lane-changing intention need to be discussed on a case-by-case basis.

- (2)

- When the type of vehicle behind the adjacent lane is the same as that of the target vehicle, which is an intelligent networked vehicle, the vehicle behind the adjacent lane can obtain real-time status information of the target vehicle through vehicle-to-vehicle communication and quickly make changes based on the target vehicle’s status. In this case, when the target vehicle changes lanes, it only needs to meet the requirements of having a speed greater than the vehicle behind the adjacent lane and a longitudinal distance greater than 0 from the vehicle behind the adjacent lane.

4. Construction of Three-Lane Mixed Traffic Flow Model in Intelligent Connected Environment

4.1. Left Lane Change Model

4.2. Middle-Lane Lane Change Model

- (1)

- The target vehicle is an HDV

- (2)

- The target vehicle is an intelligent connected vehicle.

4.3. Right Lane Change Model

5. Simulation Analysis of Mixed Traffic Flow Characteristics in an Intelligent Connected Environment

5.1. Simulation Parameter Settings

- (1)

- The discrete spatiotemporal characteristics of this model (time step τ = 1 s, spatial resolution 0.5 m) ensure high computational efficiency while maintaining the accuracy of microscopic behaviors.

- (2)

- During model iteration, the state of each cell is updated independently. The state transition rules are deterministic, and the updates of speed and position are based on physical formulas without iterative solving processes, resulting in stable computational efficiency.

- (3)

- The core rules of the model (car-following and lane-changing) involve local interactions. The algorithmic complexity increases linearly with the number of vehicles, meaning computational complexity grows as the network scale expands.

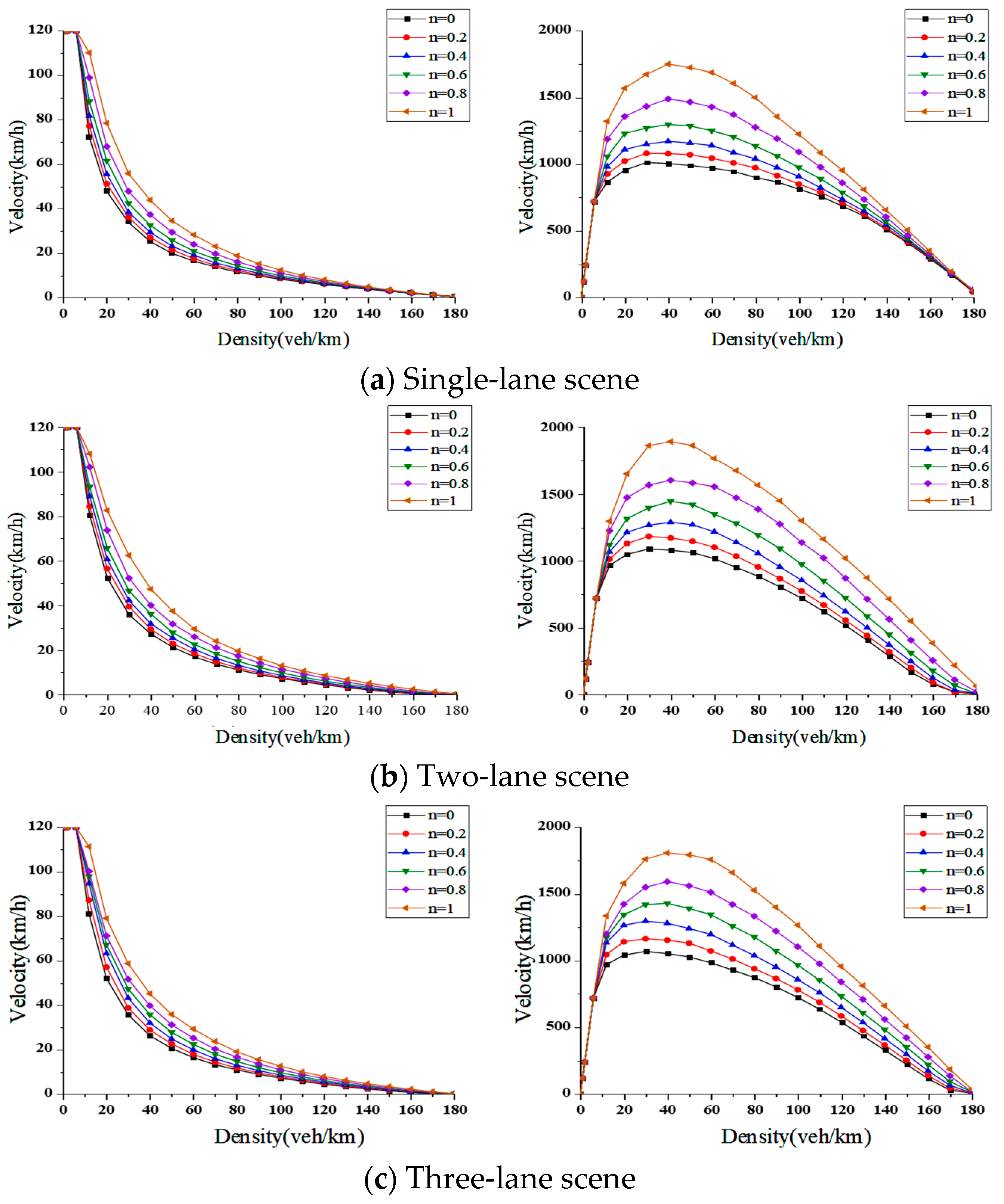

5.2. Basic Diagram Analysis

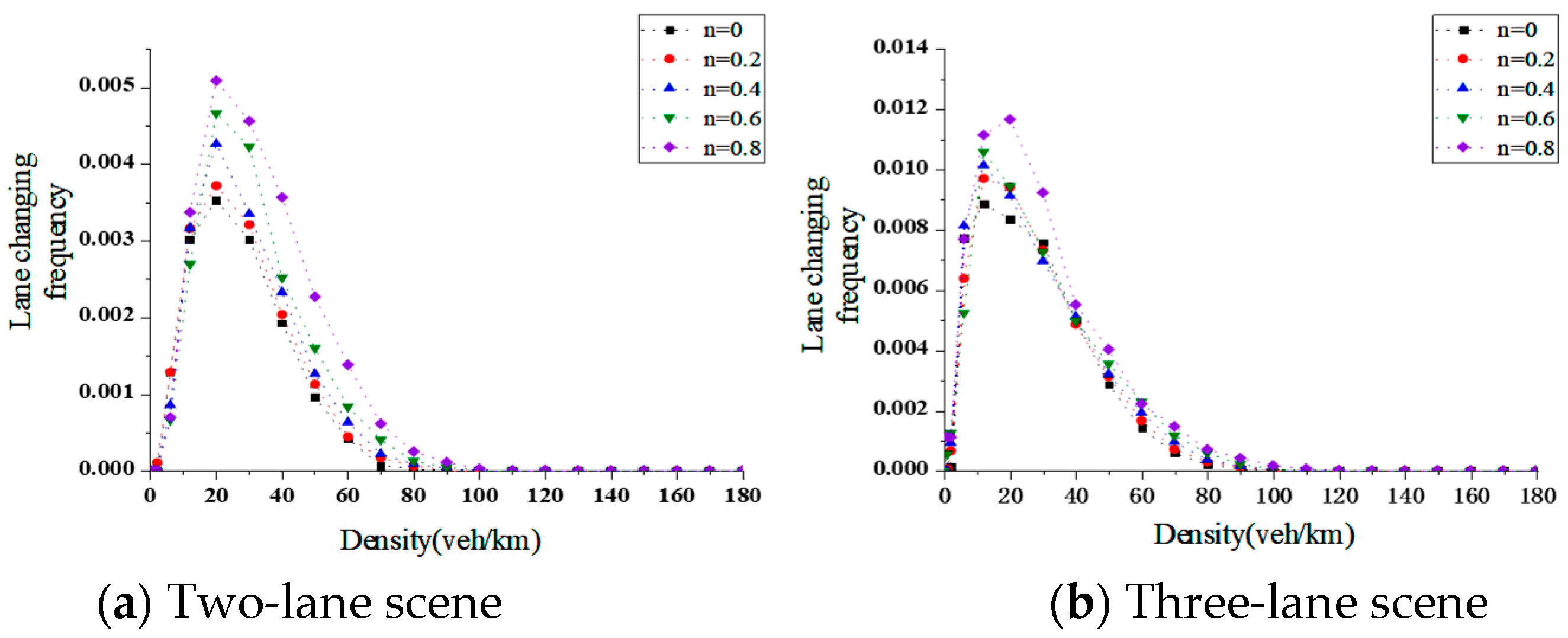

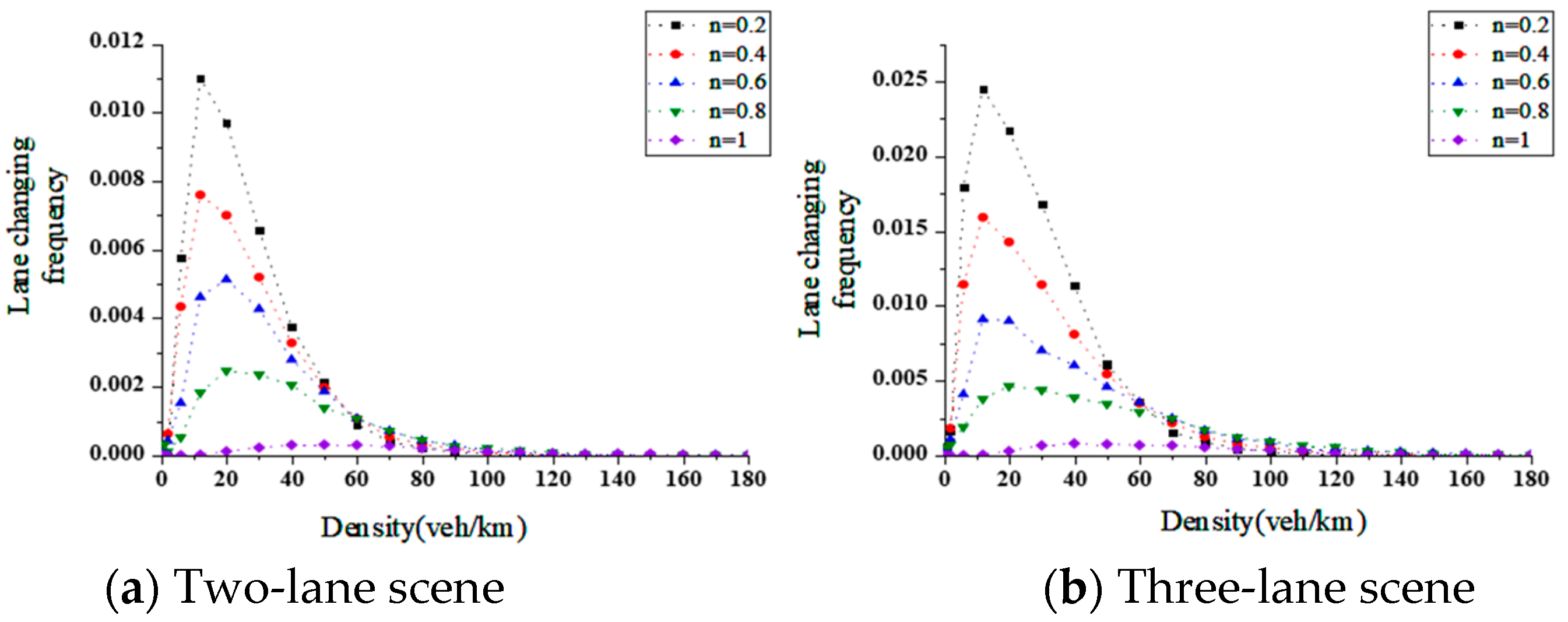

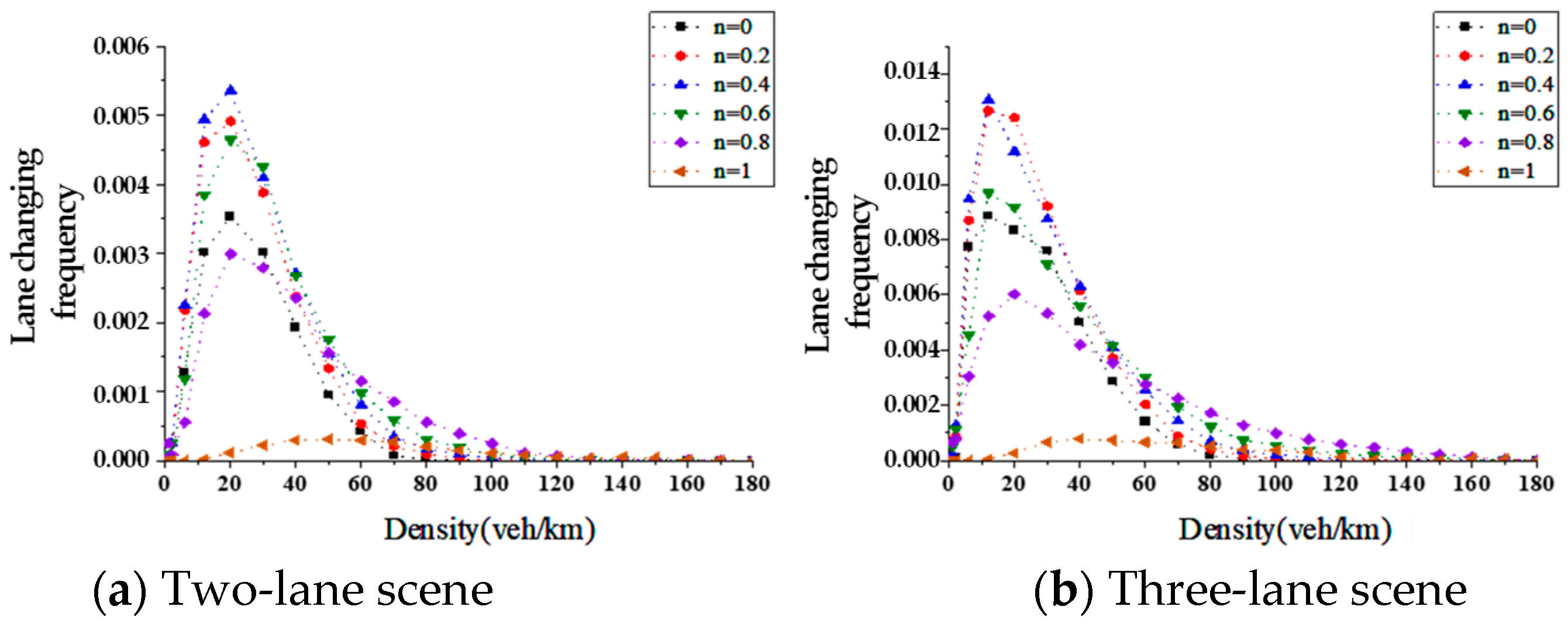

5.3. Analysis of Lane-Changing Frequency

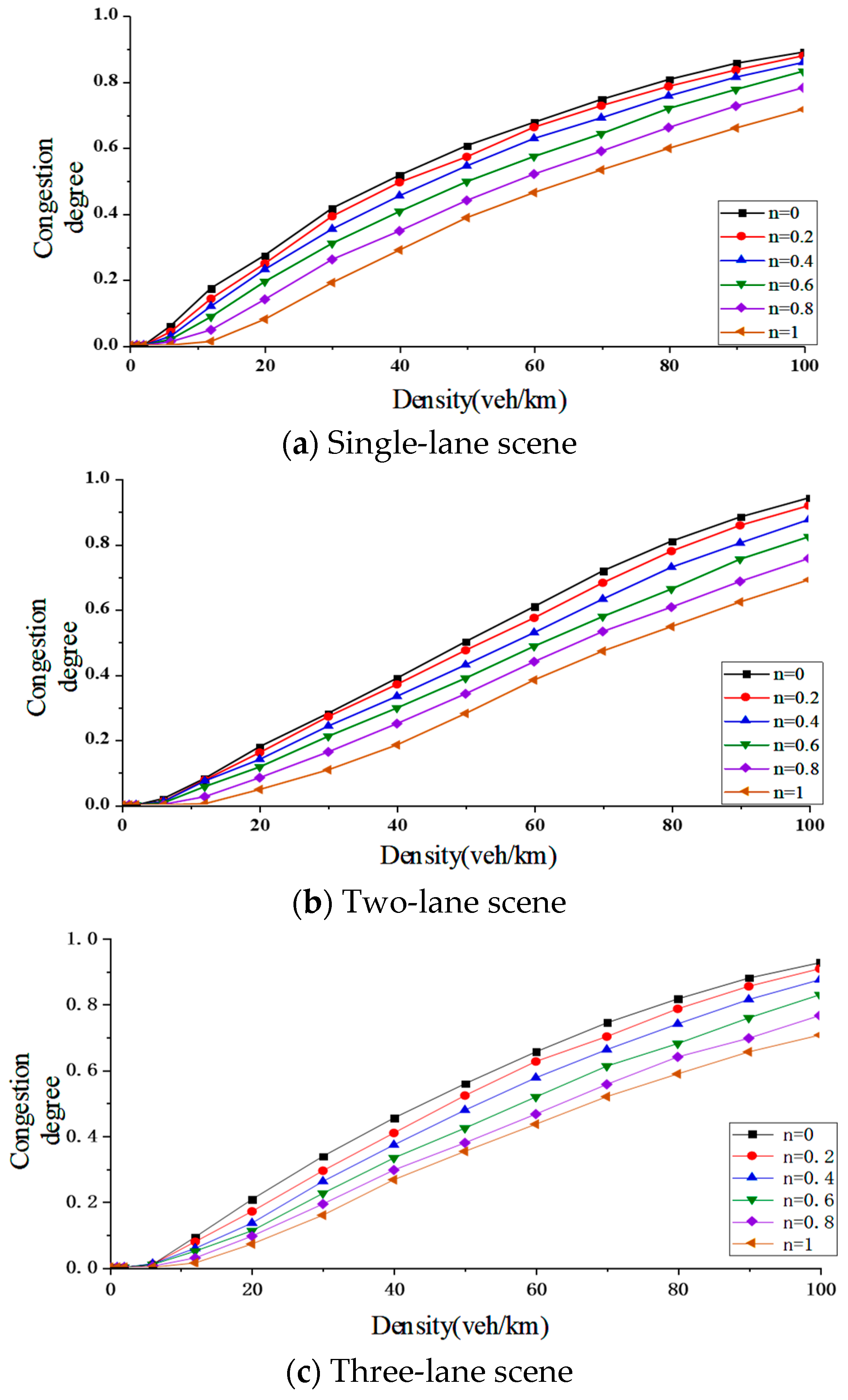

5.4. Crowding Analysis

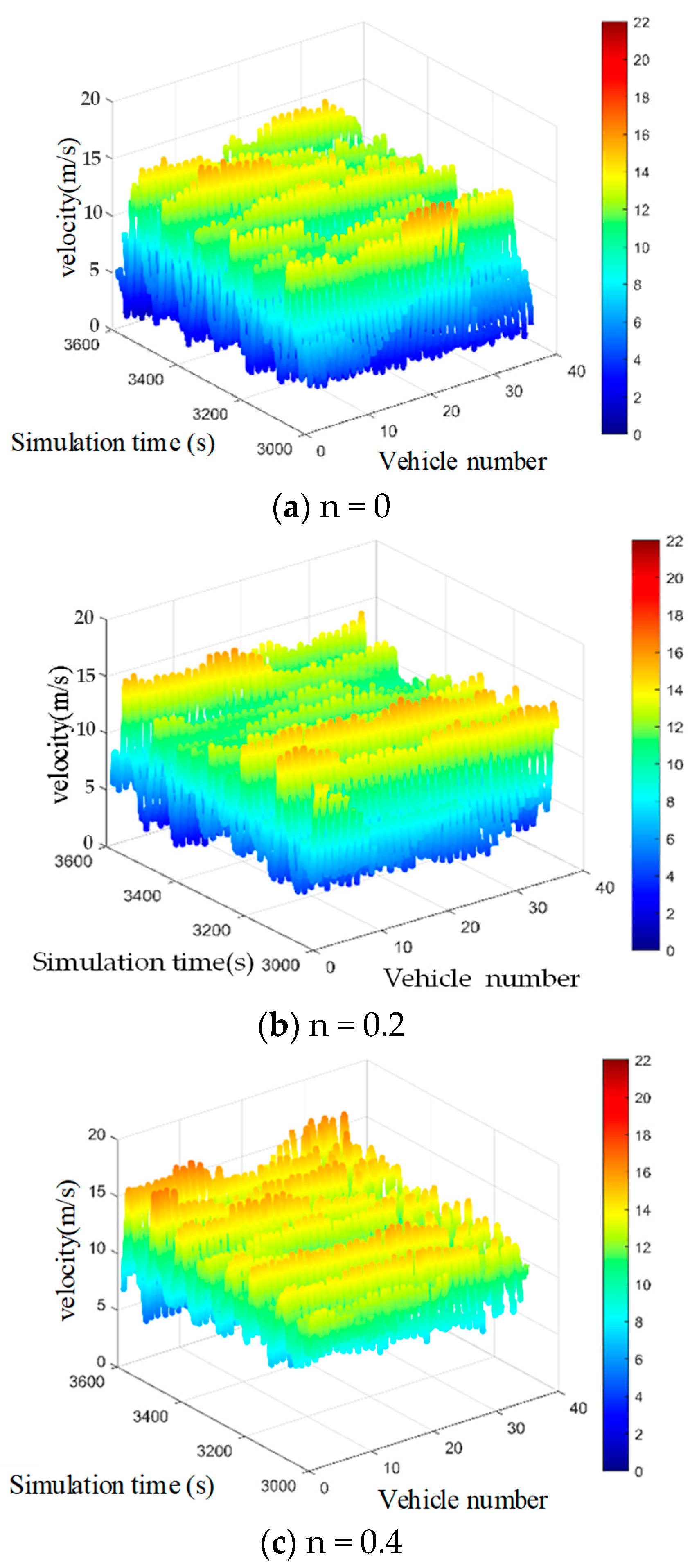

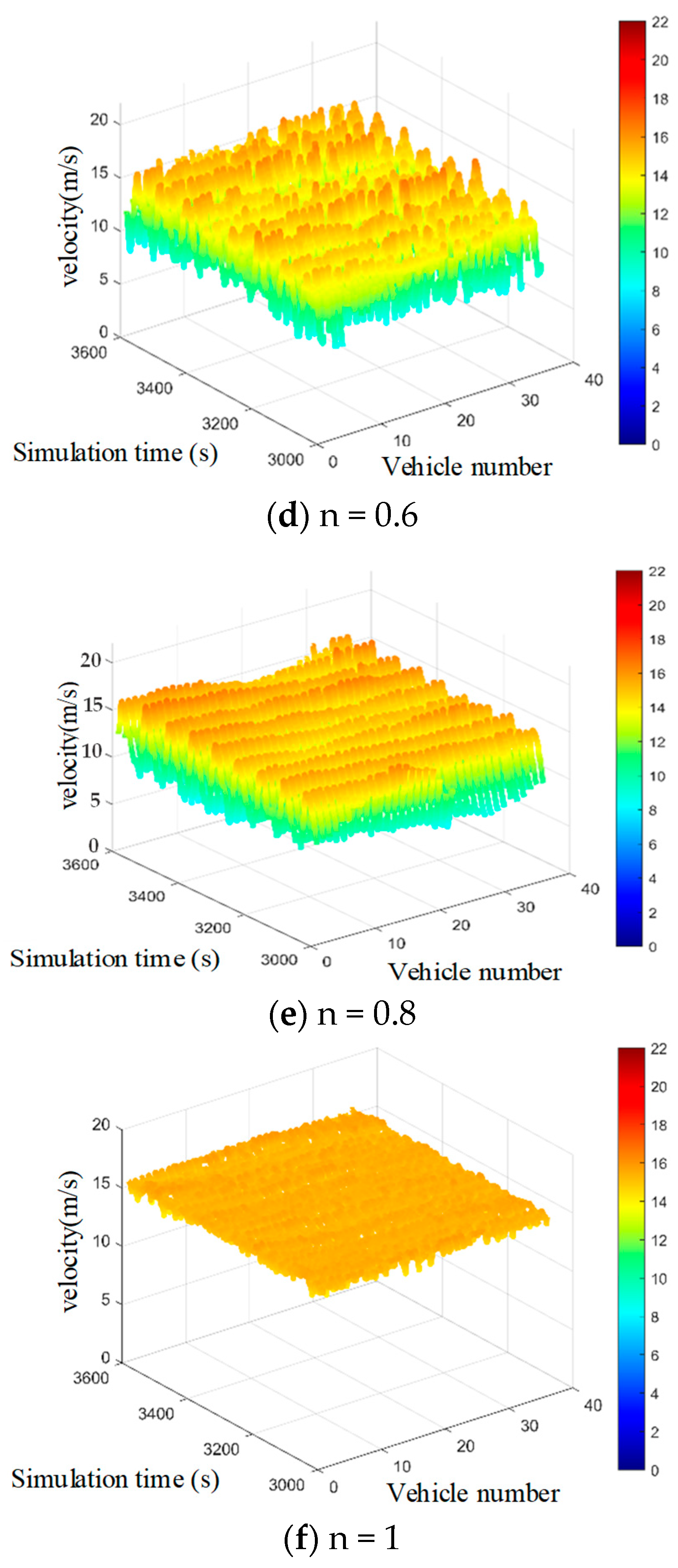

5.5. Analysis of Speed Fluctuations in Following State

6. Research Summary

- (1)

- Research on the Mixed Traffic Flow Model of Single-Lane in Intelligent Connected Vehicle Environment. This article analyzes the car-following patterns in mixed traffic flow, using vehicle pairs under different car-following patterns as modeling objects. The IDM is selected as the car-following model for mixed traffic flow and improved. On the basis of the IDM, this article considers the different accuracy of obtaining preceding vehicle information for different following modes and adopts different safe headway intervals; on the other hand, considering the different reaction times under different car-following modes and the impact of driver psychological effects on driving behavior, an IDM based on fear level and reaction time was constructed, and a single-lane mixed traffic flow model was constructed based on the cellular automaton model. By setting different random slowing probabilities, the driving characteristics of the two types of vehicles were further distinguished.

- (2)

- Research on Multi-Lane Mixed Traffic Flow Model in Intelligent Connected Environment. This article fully considers the differences in lane-changing intentions, conditions, and choices between ICVs and HDVs, and it improves the classic TCAM by classifying vehicle types to construct a mixed traffic flow lane-changing model. Specifically, based on the car-following model, differentiated lane-changing rules are formulated for the two types of vehicles. At the same time, the established two-lane lane-changing rules are introduced into the three-lane model, and a three-lane lane-changing model is constructed for different vehicle types. Different lane-changing probabilities are set according to the different types of changing vehicles in the two-lane and three-lane lane-changing models.

- (3)

- Research on the Characteristics of Mixed Traffic Flow. Based on the constructed mixed traffic flow car-following and lane-changing models, we established simulation scenarios for mixed traffic flow on single-lane, double-lane, and three-lane straight road segments using Matlab. The characteristics of the mixed traffic flow were analyzed in four aspects: fundamental diagrams, lane-changing frequency, congestion conditions, and stability. From the analysis of the fundamental diagrams, it can be observed that as the proportion of connected and automated vehicles (CAVs) increases, both the average speed and traffic flow volume on the road show a clear upward trend, and the critical density of the road gradually increases. Taking the single-lane scenario as an example, under pure human-driven conditions (n = 0), the average speed was 15 m/s, the peak traffic flow volume reached 1000 veh/h, and the critical density was approximately 18.5 veh/km. When n = 1, the average speed increased to about 25 m/s, the peak traffic flow volume reached 2000 veh/h, and the critical density rose to approximately 22.2 veh/km. The traffic capacity of the pure CAV flow (n = 1) is approximately 1.7 times that of the pure human-driven traffic flow (n = 0). Furthermore, examining the traffic capacity across different CAV proportions in various scenarios, the double-lane scenario showed a traffic capacity increase of about 59% at n = 0.6 compared to n = 0, demonstrating the most significant improvement in road capacity among all scenarios. The results from the lane-changing frequency analysis indicate that as the proportion of CAVs increases, the lane-changing frequency of human-driven vehicles gradually rises, while that of CAVs gradually decreases. The overall lane-changing frequency exhibits a trend of initially increasing and then decreasing, with the three-lane scenario showing higher lane-changing frequencies than the double-lane scenario. For instance, at n = 0.2, the overall lane-changing frequency in the double-lane scenario was 0.003, while in the three-lane scenario it was 0.006. Regarding congestion conditions, an increase in the proportion of CAVs reduces the congestion proportion under the same density. The double-lane scenario demonstrates the best mitigation effect on road congestion at low-to-medium densities (e.g., 50 veh/km), with a congestion degree of 0.51. The stability results show that as the proportion of CAVs increases, the speed difference between leading and following vehicles gradually decreases, and the speed fluctuation amplitude during car-following also diminishes. When the proportion of CAVs reaches a high level, vehicles maintain a stable speed (v ∈ [14, 16]) and remain in a relatively stable state, thereby enhancing the overall stability of the traffic flow.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chen, D.; Srivastava, A.; Ahn, S.; Li, T. Traffic dynamics under speed disturbance in mixed traffic with automated and non-automated vehicles. Transp. Res. C Emerg. Technol. 2020, 113, 293–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Jin, S. Intelligent vehicle car-following model based on cyber–physical system and its simulation under mixed traffic flow. Physica A 2024, 634, 129518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Cheng, G. A car-following model of CAVs integrating state information from multiple leading and single following vehicles. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 33867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, X.; Shi, H.; Zhou, Y.; Li, Z. Hybrid car-following control for CAVs: Integrating linear feedback and deep reinforcement learning to stabilize mixed traffic. Transp. Res. C Emerg. Technol. 2024, 167, 104773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, D.; Zhang, Y. Disturbances and safety analysis of linear adaptive cruise control for cut-in scenarios: A theoretical framework. Transp. Res. C Emerg. Technol. 2024, 168, 104576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, K.; Zheng, F.; Liu, X.; Fan, Z. Cooperative vehicle platoon control considering longitudinal and lane-changing dynamics. Transp. A Transp. Sci. 2024, 20, 325–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Z.; Hu, P.; Li, N.; Chen, X.; Chen, W.; Wang, H.; Xie, N.; Li, Y.; Dong, C. Modelling and simulation of mixed traffic flow with dedicated lanes for connected automated vehicles. Expert Syst. Appl. 2025, 274, 127027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Yang, J.; Yang, X.; Duan, X. Measuring collision risk in mixed traffic flow under the car-following and lane-changing behavior. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 11400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Anis, M.; Lord, D.; Zhang, H.; Zhou, Y.; Ye, X. Beyond 1D and oversimplified kinematics: A generic analytical framework for surrogate safety measures. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2024, 204, 107649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sha, H.; Singh, M.; Haouari, R.; Papazikou, E.; Quddus, M.; Quigley, C.; Chaudhry, A.; Thomas, P.; Weijermars, W.; Morris, A. Network-wide safety impacts of dedicated lanes for connected and autonomous vehicles. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2024, 195, 107424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, K.; Zheng, F.; Liu, X. Enhancing mixed traffic safety assessment: A novel safety metric combined with a comprehensive behavioral modeling framework. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2024, 208, 107766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, H.; Wang, Q.; Wang, Z.; Yao, X. Study on driver behavior pattern in merging area under naturalistic driving conditions. J. Adv. Transp. 2024, 2024, 7766164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Zhang, Y. Driver–automated vehicle interaction in mixed traffic: Types of interaction and drivers’ driving styles. Hum. Factors 2024, 66, 544–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, P.; Ding, H.; Sun, Z.; Chen, H. A game-based hierarchical model for mandatory lane change of autonomous vehicles. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2024, 25, 11256–11268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Jia, N.; Li, Q.; Zhao, Y. Modeling and simulation of mixed traffic flow in maintenance operation zone considering the impact of trucks in an intelligent connected environment. Transp. Res. Rec. 2025, 2679, 683–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, W.; Zhao, X.; Li, H.; Fu, Q. Traffic flow impact of mixed heterogeneous platoons on highways: An approach combining driving simulation and microscopic traffic simulation. Physica A 2024, 643, 129803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrabani, B.; Erdmann, J.; Sgambi, L.; Seyedabrishami, S.; Snelder, M. A multiclass simulation-based dynamic traffic assignment model for mixed traffic flow of connected and autonomous vehicles and human-driven vehicles. Transp. A Transp. Sci. 2025, 21, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, X.; Wan, C.; Li, Z.; Zhang, X.; Cao, C. Modeling and simulation of multi-lane heterogeneous traffic flow in intelligent and Connected Vehicle environment. Transp. Syst. Eng. Inf. 2022, 22, 74–84. [Google Scholar]

- Dai, C.; Zhang, J. Walter curve, information utility, and their applications in economic management. Nankai Econ. Res. 1987, 3, 33–38. [Google Scholar]

- Dai, C.; Liu, G. Information utility and its application in decision-making behavior. Proc. Annu. Conf. Chin. Soc. Inf. Econ. 2007, 2007, 16–18. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X. Construction of Microscopic Traffic Model and Simulation Analysis of Traffic Flow Characteristics Under Human–Machine Hybrid Driving Conditions. Ph.D. Thesis, Hebei University of Technology, Tianjin, China, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, T.; Yao, Z.; Jiang, Y.; Yang, T. Fundamental Diagram Model of Considering Reaction Time in Environment of Intelligent Connected Vehicles. J. Highw. Transp. Technol. 2020, 37, 108–117. [Google Scholar]

- Qin, Y.; Wang, H.; Wang, W.; Wan, Q. Heterogeneous traffic flow fundamental diagram model with mixed CACC and ACC vehicles. China J. Highw. Transp. 2017, 30, 127–136. [Google Scholar]

| Variables | Descriptions | Units |

|---|---|---|

| a | Maximum acceleration | m/s2 |

| an | Acceleration of the n-th vehicle | m/s2 |

| b | Comfortable deceleration | m/s2 |

| c | Preference coefficient for subjective novelty | – |

| Gapn | Gap to the preceding vehicle in the current lane | m |

| Gapn,back | Gap to the following vehicle in the adjacent lane | m |

| Gapn,front | Gap to the preceding vehicle in the adjacent lane | m |

| Gapn,leftback | Gap to the following vehicle in the left lane | m |

| Gapn,leftfront | Gap to the preceding vehicle in the left lane | m |

| Gapn,rightback | Gap to the following vehicle in the right lane | m |

| Gapn,rightfront | Gap to the preceding vehicle in the right lane | m |

| h | Time headway | s |

| L | Vehicle length | m |

| Mn(t) | Lane index of the n-th vehicle at time | – |

| Pa | Probability of changing lanes in the basic lane-changing rule | – |

| Pb | Probability of changing lanes in the ICV/HDV mixed lane-changing rule | – |

| s | Actual spacing between two vehicles | m |

| s0 | Minimum parking distance | m |

| T0 | Safe headway of an HDV following an ICV | s |

| ∆T | Simulation time step | s |

| THDC | Safe headway in HDC mode | s |

| TACC | Safe headway in ACC mode | s |

| TCACC | Safe headway in CACC mode | s |

| v | Vehicle speed | m/s |

| ∆v | Relative speed to the preceding vehicle | m/s |

| Expected acceleration | m/s2 | |

| vf | Free-flow speed | m/s |

| vmax | Maximum allowable speed | m/s |

| vn(t) | Speed of the n-th vehicle at time | m/s |

| vback(t) | Speed of the following vehicle in the adjacent lane | m/s |

| vleftback(t) | Speed of the following vehicle in the left lane | m/s |

| vrightback(t) | Speed of the following vehicle in the right lane | m/s |

| W | Information utility in Wundt’s psychological law | – |

| xn(t) | Position of the n-th vehicle at time | m |

| γ1 | Reaction time of a human-driven vehicle | s |

| γ2 | Recognition time of an ICV following an HDV | s |

| γ3 | Communication delay of an ICV in CACC mode (set to 0) | s |

| θ | Driver’s subjective understanding of ICV performance | – |

| β | Fear parameter of the driver when following an ICV | – |

| Φ | Subjective novelty in Wundt’s psychological law | – |

| IDM Car-Following Model Parameters | Symbol | Value |

|---|---|---|

| Maximum acceleration (m/s2) | a | 1 |

| Comfort deceleration (m/s2) | b | 2 |

| Free flow speed (m/s) | vf | 33.3 |

| Minimum parking distance (m) | S0 | 2 |

| Vehicle length (m) | L | 5 |

| Scene Parameters | Symbol | Value |

|---|---|---|

| Cell length (m) | cell | 0.5 |

| Vehicle length (m) | L | 5 |

| Lane length (m) | La | 1200 |

| Lane speed limit (km/h) | Vmax | 120 |

| Simulation time step (s) | τ | 1 |

| Simulation time (s) | T | 3600 |

| Driver’s level of understanding of connected vehicles | θ | values in [0, 1] |

| Probability of lane change for HDV models | Pa | 0.3 |

| Random slowing probability of HDVs | P1 | 0.2 |

| Probability of lane change in intelligent connected vehicle model | Pb | 0.5 |

| Random slowing probability of ICV | P2 | 0.05 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zhao, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, H.; Lei, X.; Wang, J.; Xiao, M. Sustainable Mixed-Traffic Micro-Modeling in Intelligent Connected Environments: Construction and Simulation Analysis. Sustainability 2026, 18, 960. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18020960

Zhao Y, Zhang X, Zhang H, Lei X, Wang J, Xiao M. Sustainable Mixed-Traffic Micro-Modeling in Intelligent Connected Environments: Construction and Simulation Analysis. Sustainability. 2026; 18(2):960. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18020960

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhao, Yang, Xiaoqiang Zhang, Haoxing Zhang, Xue Lei, Jianjun Wang, and Mei Xiao. 2026. "Sustainable Mixed-Traffic Micro-Modeling in Intelligent Connected Environments: Construction and Simulation Analysis" Sustainability 18, no. 2: 960. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18020960

APA StyleZhao, Y., Zhang, X., Zhang, H., Lei, X., Wang, J., & Xiao, M. (2026). Sustainable Mixed-Traffic Micro-Modeling in Intelligent Connected Environments: Construction and Simulation Analysis. Sustainability, 18(2), 960. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18020960