Spatiotemporal Differentiation Characteristics and Meteorological Driving Mechanisms of Soil Moisture in Soil–Rock Combination Controlled by Microtopography in Hilly and Gully Regions

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Overview of the Research Area

2.2. Soil Thickness Survey and Monitoring Sample Plot Layout

2.2.1. Investigation of Soil Thickness

2.2.2. Moisture Monitoring Plot Layout

Neutron Probe Monitoring

HOBO Data Logger

2.3. Meteorological Data Collection

2.4. Research Methods

2.4.1. Soil Profile Moisture Calculation

2.4.2. Spearman’s Rank Correlation Coefficient

3. Results

3.1. Soil Thickness and Soil-Rock Combination Characteristics

3.1.1. Spatial Differentiation Characteristics of Soil Thickness in Different Microtopography

3.1.2. Classification and Characteristics of Typical Soil-Rock Combinations

3.2. Spatiotemporal Distribution Patterns of Soil Moisture Under Different Soil-Rock Combinations

3.2.1. Vertical Distribution Structure of Soil Moisture

3.2.2. Seasonal Dynamics of Soil Moisture

3.3. Temporal Dynamic Characteristics of Soil Moisture in the S30 Combination

3.3.1. Analysis of Meteorological Elements Evolution

3.3.2. Daily-Scale Dynamic Characteristics of Soil Moisture in the S30 Combination

3.3.3. Precipitation Events and Their Impact on the Vertical Distribution of Soil Moisture

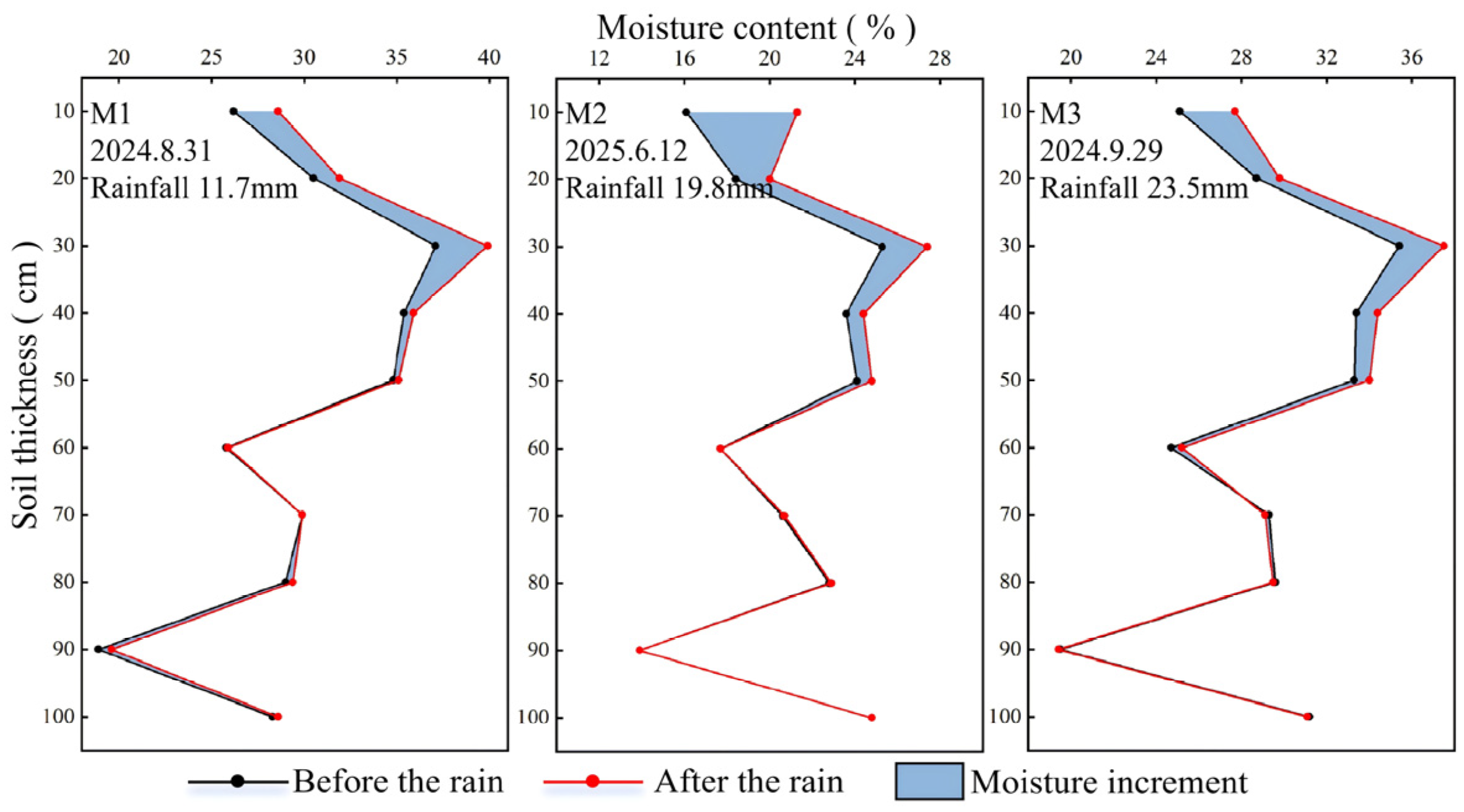

Light Rain Events

Moderate Rain Events

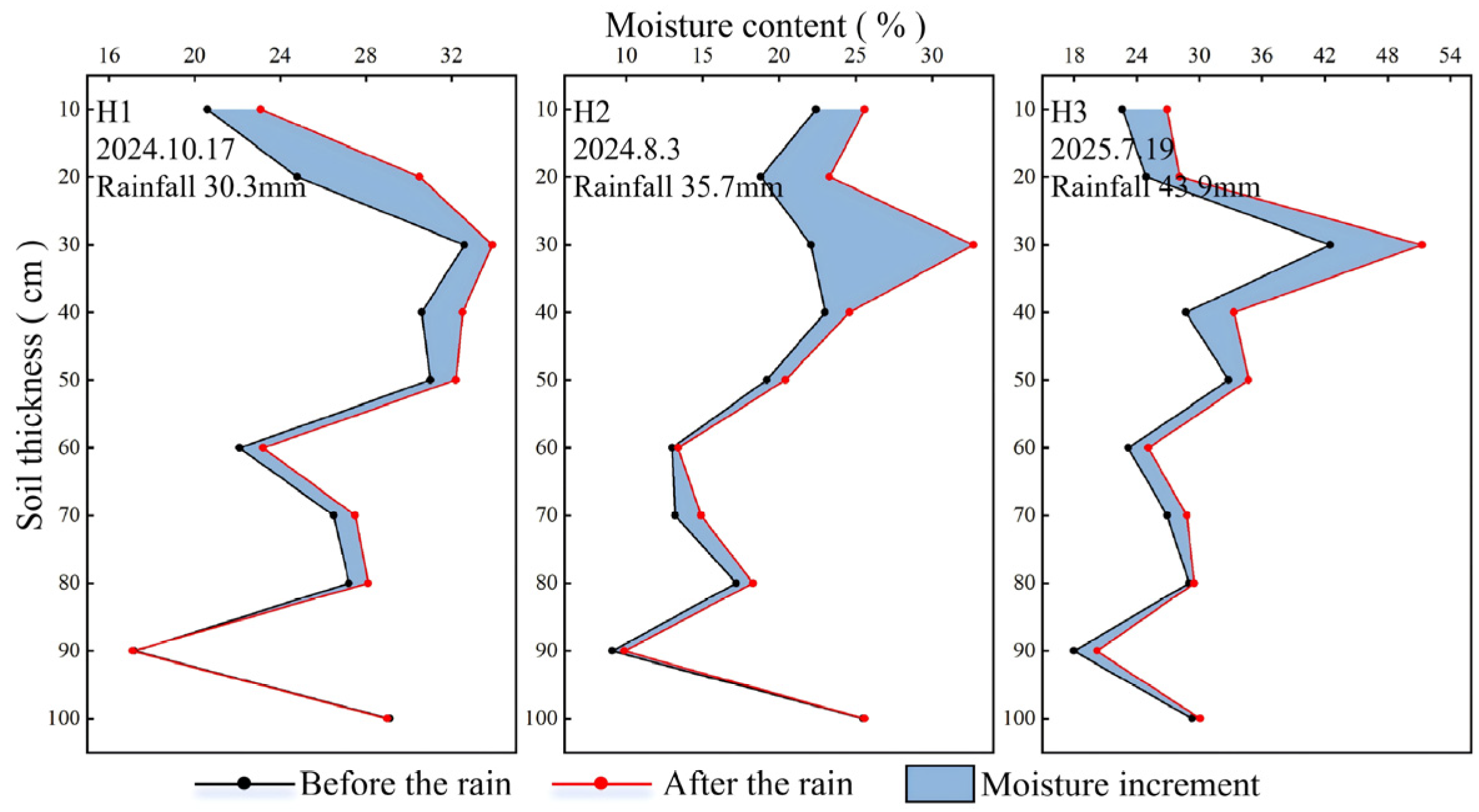

Heavy Rain Events

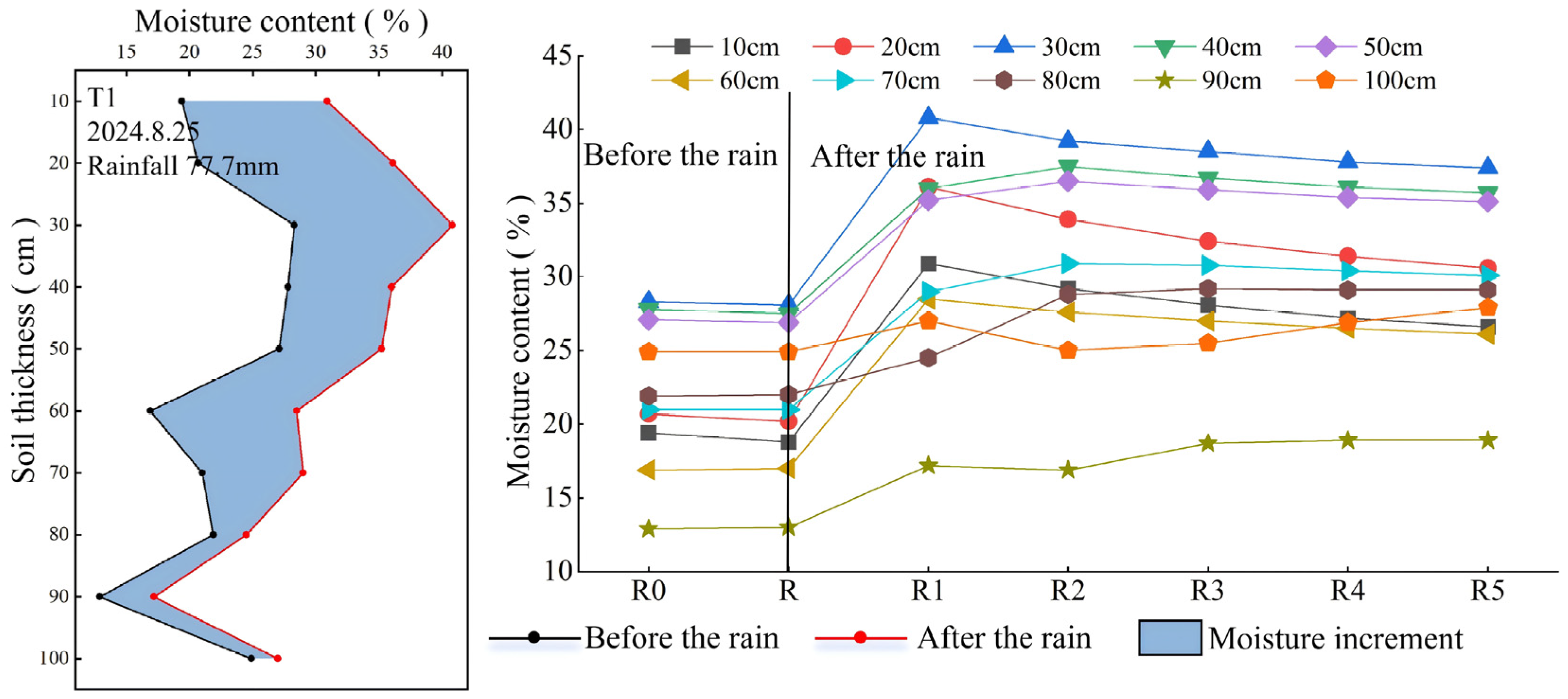

Rainstorm Events

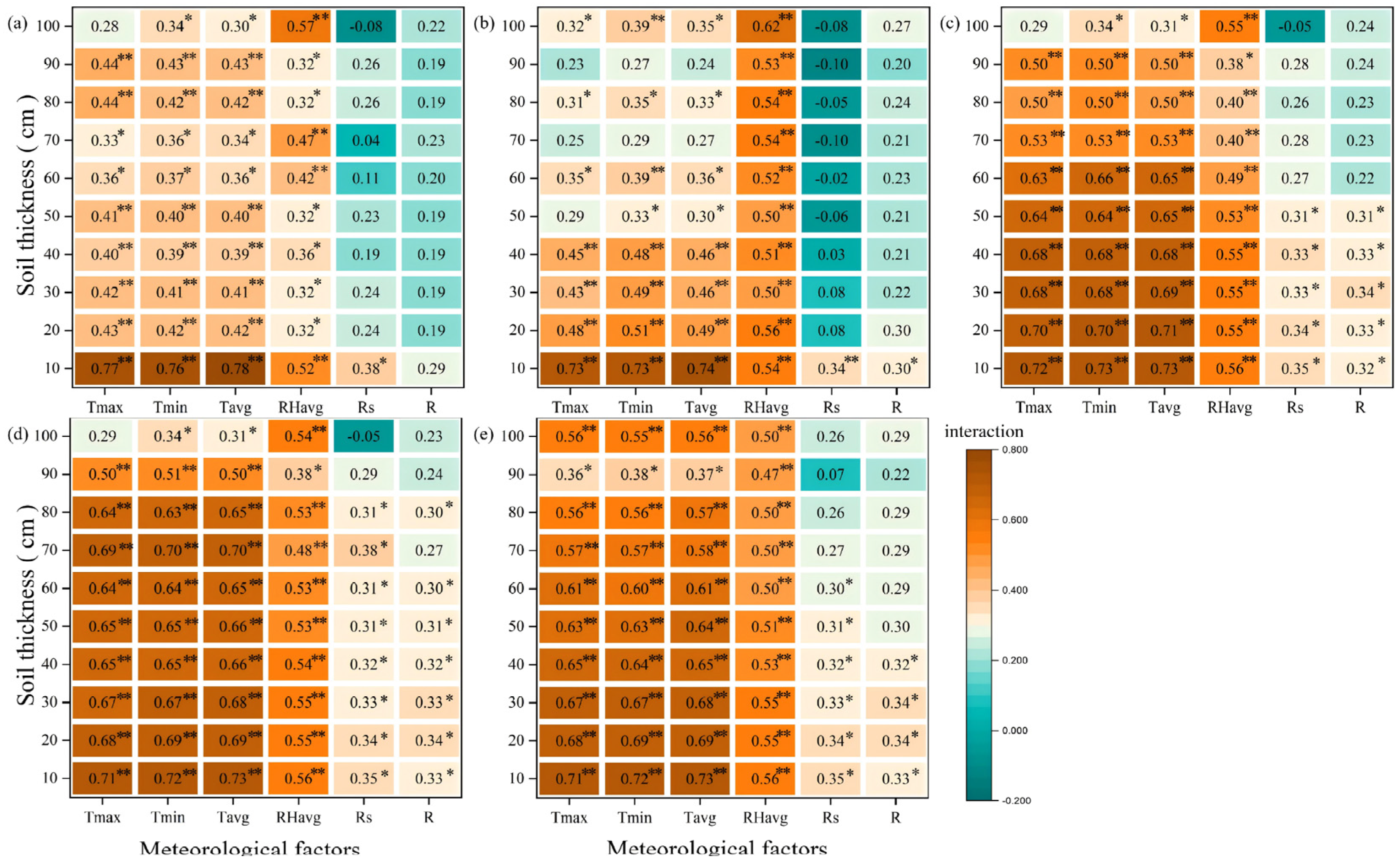

3.4. Influence of Meteorological Factors on Soil Moisture

4. Discussion

4.1. Mechanisms of Microtopography in Controlling Soil Thickness and Soil-Rock Combinations

4.2. Regulatory Role of Soil-Rock Combinations on Spatiotemporal Differentiation of Soil Moisture

4.3. Hierarchical Response of Soil Moisture to Precipitation Driving and the Role of the Soil-Rock Interface

4.4. Vertical Differentiation Driven by Meteorological Factors and the Modulating Effects of Soil-Rock Combinations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wohlfart, C.; Kuenzer, C.; Chen, C.; Liu, G. Social-ecological challenges in the Yellow River basin (China): A review. Environ. Earth Sci. 2016, 75, 1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Huang, J.; Liu, X.; Guan, X.; Wei, Y.; Ding, L.; Han, D. The evolution of ecological security and its drivers in the Yellow River Basin. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 47501–47515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Z.; Wu, Z.; Yao, W.; Noori, M.; Yang, C.; Xiao, P.; Deng, L. Pisha sandstone: Causes, processes and erosion options for its control and prospects. Int. Soil Water Conserv. Res. 2019, 7, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, W.; Zhang, X. Effect of Pisha sandstone on water infiltration of different soils on the Chinese Loess Plateau. J. Arid Land 2016, 8, 331–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Yan, F.; Wang, Y. Vegetation growth status and topographic effects in the pisha sandstone area of China. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 2759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penna, D.; Borga, M.; Norbiato, D.; Dalla Fontana, G. Hillslope scale soil moisture variability in a steep alpine terrain. J. Hydrol. 2009, 364, 311–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulebak, J.R.; Tallaksen, L.M.; Erichsen, B. Estimation of areal soil moisture by use of terrain data. Geogr. Ann. Ser. A Phys. Geogr. 2000, 82, 89–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, K.; Chai, J.; Qin, Y.; Li, X.; Zhou, H. Collapse inhibition mechanism analysis and durability properties of cement-stabilized Pisha sandstone. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 2022, 81, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, R.; Yu, Y.; Liu, D.; Wang, J.; Gao, Z.; Liu, J.; Rodrigo-Comino, J. Vegetation pattern and topography determine erosion characteristics in a semi-arid sandstone hillslope-gully system. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 2024, 75, e13498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, X.S.; Zheng, B.; Mao, T.Q.; Hu, R.L. Investigation of the effect of soil matrix on flow characteristics for soil and rock mixture. Géotech. Lett. 2016, 6, 226–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Peng, X.; Dai, Q.; Li, C.; Xu, S.; Liu, T. Storage infiltration of rock-soil interface soil on rock surface flow in the rocky desertification area. Geoderma 2023, 435, 116512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wang, S.; Peng, T.; Zhao, G.; Dai, B. Hydrological characteristics and available water storage of typical karst soil in SW China under different soil-rock structures. Geoderma 2023, 438, 116633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Hui, Y.; Zhou, C.; Li, X.; Rong, Y. Soil-water characteristic surface model of soil-rock mixture. J. Mt. Sci. 2023, 20, 2756–2768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Deng, Z.; Chen, L.; Huang, Y.; Peng, X. Quantifying the influence of soil-rock interfaces on water infiltration rate in karst landscapes. Geoderma 2025, 460, 117432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Xiao, P.; Yao, W.; Liu, G.; Sun, W. Analysis of complex erosion models and their implication in the transport of Pisha sandstone sediments. Catena 2021, 207, 105636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Z.; Li, Z.; Cai, C.; Shi, Z.; Xu, Q.; Wang, X. Soil thickness effect on hydrological and erosion characteristics under sloping lands: A hydropedological perspective. Geoderma 2011, 167, 41–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- dos Santos, K.F.; Barbosa, F.T.; Bertol, I.; de Souza Werner, R.; Wolschick, N.H.; Mota, J.M. Study of soil physical properties and water infiltration rates in different types of land use. Semin. Ciênc. Agrár. 2018, 39, 87–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Xu, M.; Wang, Z. Study on reforestation with seabuckthorn in the Pisha Sandstone area. J. Hydro-Environ. Res. 2009, 3, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedrazas, M.A.; Hahm, W.J.; Huang, M.H.; Dralle, D.; Nelson, M.D.; Breunig, R.E.; Rempe, D.M. The relationship between topography, bedrock weathering, and water storage across a sequence of ridges and valleys. J. Geophys. Res. Earth Surf. 2021, 126, e2020JF005848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonfatti, B.R.; Hartemink, A.E.; Vanwalleghem, T.; Minasny, B.; Giasson, E. A mechanistic model to predict soil thickness in a valley area of Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil. Geoderma 2018, 309, 17–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patton, N.R.; Lohse, K.A.; Godsey, S.E.; Crosby, B.T.; Seyfried, M.S. Predicting soil thickness on soil mantled hillslopes. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 3329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Ding, G.; Wang, H.; Li, S.; Dai, Z. Study on the dynamic development law of fissure in expansive soil under different soil thickness. Arch. Civ. Eng. 2023, 69, 519–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, J. Impacts of rock-soil interface on soil infiltration and spatio-temporal water distribution during ecosystem succession in karst areas. Catena 2025, 260, 109474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohrt, J.; Ries, F.; Sauter, M.; Lange, J. Significance of preferential flow at the rock soil interface in a semi-arid karst environment. Catena 2014, 123, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Qin, F.; Sheng, Y.; Li, L.; Dong, X.; Zhang, S.; Shen, C. Soil quality evaluation and limiting factor analysis in different microtopographies of hilly and gully region based on minimum data set. Catena 2025, 254, 108973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starks, P.J.; Heathman, G.C.; Jackson, T.J.; Cosh, M.H. Temporal stability of soil moisture profile. J. Hydrol. 2006, 324, 400–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subin, Z.M.; Koven, C.D.; Riley, W.J.; Torn, M.S.; Lawrence, D.M.; Swenson, S.C. Effects of soil moisture on the responses of soil temperatures to climate change in cold regions. J. Clim. 2013, 26, 3139–3158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zar, J.H. Significance testing of the Spearman rank correlation coefficient. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1972, 67, 578–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Headrick, T.C. A note on the relationship between the Pearson product-moment and the Spearman rank-based coefficients of correlation. Open J. Stat. 2016, 6, 1025–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eltner, A.; Maas, H.G.; Faust, D. Soil micro-topography change detection at hillslopes in fragile Mediterranean landscapes. Geoderma 2018, 313, 217–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; He, Y.; Huang, K.; Li, P.; Li, S.; Yan, L.; Tang, B. Spatio-Temporal Characteristics of the Morphological Development of Gully Erosion on the Chinese Loess Plateau. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 2710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, C.G. Drainage systems developed by sapping on Earth and Mars. Geology 1982, 10, 147–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bracken, L.J.; Croke, J. The concept of hydrological connectivity and its contribution to understanding runoff-dominated geomorphic systems. Hydrol. Process. 2007, 21, 1749–1763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saco, P.M.; Moreno-de las Heras, M. Ecogeomorphic coevolution of semiarid hillslopes: Emergence of banded and striped vegetation patterns through interaction of biotic and abiotic processes. Water Resour. Res. 2013, 49, 115–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merrill, S.D.; Smith, S.J.; Power, J.F. Effect of disturbed soil thickness on soil water use and movement under perennial grass. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 1985, 49, 196–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rempe, D.M.; Dietrich, W.E. Direct observations of rock moisture, a hidden component of the hydrologic cycle. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, 2664–2669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Feng, S.; Wang, J.; Chen, M.; Wang, K.; Liu, C.; Shangguan, Z. Assessing the change in soil water deficit characteristics from grassland to forestland on the Loess Plateau. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 167, 112616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopp, L.; McDonnell, J.J. Connectivity at the hillslope scale: Identifying interactions between storm size, bedrock permeability, slope angle and soil depth. J. Hydrol. 2009, 376, 378–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidon, P. Towards a better understanding of riparian zone water table response to precipitation: Surface water infiltration, hillslope contribution or pressure wave processes? Hydrol. Process. 2012, 26, 3207–3215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Z.; Guo, L.; Lin, H.; Wang, Y.; Yu, Y.; Chu, G.; Zhang, J. Soil moisture response to rainfall on the Chinese Loess Plateau after a long-term vegetation rehabilitation. Hydrol. Process. 2018, 32, 1738–1754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Q.; Zhao, W.; Qiu, Y.; Zhao, M.; Zhong, L. Spatial heterogeneity of soil moisture and the scale variability of its influencing factors: A case study in the Loess Plateau of China. Water 2013, 5, 1226–1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Macrotopographic | Count | Mean (cm) | SD (cm) | CV | Min (cm) | Max (cm) | Median (cm) | Skewness | Kurtosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scarp | 59 | 40 b | 9 | 0.23 | 24 | 57 | 39 | 0.09 | −1.18 |

| Furrow | 49 | 24 d | 8 | 0.33 | 9 | 38 | 25 | −0.18 | −0.98 |

| Gully | 16 | 13 e | 6 | 0.46 | 4 | 24 | 12 | 0.44 | −0.74 |

| Gently sloped terrace | 66 | 69 a | 8 | 0.12 | 49 | 101 | 68 | 0.54 | 0.22 |

| Undisturbed slope | 65 | 34 c | 9 | 0.26 | 9 | 58 | 36 | −0.69 | 0.35 |

| Collapse | 68 | 37 bc | 7 | 0.19 | 23 | 56 | 36 | 0.21 | −0.87 |

| Soil–Rock Combination | Primary Distribution Geomorphic Units | Main |

|---|---|---|

| 10 cm soil thickness (S10) | Severely eroded gully heads, rill heads, and steep gully slopes. | The soil cover is extremely thin. The soil layer structure is very discontinuous, mostly in sporadic patchy shape, and the underlying bedrock is mainly strongly weathered Jurassic sandstone. The rock–soil interface is clear and irregular, the soil preservation conditions are very poor, and the bedrock is generally exposed, which is a typical erosion ‘source area’. |

| 30 cm soil thickness (S30) | Upper and middle sections of furrows and scarps, which are erosion-dominated areas. | It can form a preliminary but fragile continuous soil layer, which provides basic conditions for vegetation planting. The underlying bedrock is mostly sandstone and sand shale interbedded, moderately weathered, and the weathered gravel transition zone is common at the rock–soil interface. This layer is still disturbed by strong erosion, and the stability of soil layer is poor, which is the key sensitive zone for the transition of erosion process to stability. |

| 50 cm soil thickness (S50) | Lower sections of undisturbed slopes and collapse landforms, representing transitional zones of erosion and deposition. | The soil layer is relatively deep and continuous, and the soil nutrient preservation capacity and water holding capacity are significantly improved. The underlying bedrock is mainly sandy shale, moderately weathered, and the rock–soil interface is relatively flat. It usually corresponds to higher vegetation coverage and biomass, reflecting strong soil accumulation capacity. |

| 70 cm soil thickness (S70) | Lower and middle parts of gentle slopes and certain valley depositional areas. | The soil layer is deep and continuous, and has excellent nutrient and water retention functions. The underlying bedrock is dominated by weakly weathered argillaceous sandstone, and the rock–soil interface is clear and flat. It is the main distribution area of high-quality forest and grass vegetation, representing the obvious soil deposition process. |

| 90 cm soil thickness (S90) | Gently sloping terraces and valley bottoms, which are stable depositional zones. | The soil layer is deep, the structure is complete, and the soil resource endowment is superior. The underlying bedrock is dominated by thick mudstone or complete sandstone, weakly weathered, and the rock–soil interface is clear and flat. It is the core area of soil and water conservation function, and also the concentrated area of human agricultural activities, representing the ‘sink area’ of regional soil conservation. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Liu, L.; Dong, X.; Qin, F.; Sheng, Y. Spatiotemporal Differentiation Characteristics and Meteorological Driving Mechanisms of Soil Moisture in Soil–Rock Combination Controlled by Microtopography in Hilly and Gully Regions. Sustainability 2026, 18, 959. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18020959

Liu L, Dong X, Qin F, Sheng Y. Spatiotemporal Differentiation Characteristics and Meteorological Driving Mechanisms of Soil Moisture in Soil–Rock Combination Controlled by Microtopography in Hilly and Gully Regions. Sustainability. 2026; 18(2):959. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18020959

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Linfu, Xiaoyu Dong, Fucang Qin, and Yan Sheng. 2026. "Spatiotemporal Differentiation Characteristics and Meteorological Driving Mechanisms of Soil Moisture in Soil–Rock Combination Controlled by Microtopography in Hilly and Gully Regions" Sustainability 18, no. 2: 959. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18020959

APA StyleLiu, L., Dong, X., Qin, F., & Sheng, Y. (2026). Spatiotemporal Differentiation Characteristics and Meteorological Driving Mechanisms of Soil Moisture in Soil–Rock Combination Controlled by Microtopography in Hilly and Gully Regions. Sustainability, 18(2), 959. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18020959