1. Introduction

Post-industrial heritage is a global phenomenon analysed across multiple dimensions—historical and cultural [

1], social and tourism-related [

2], and economic [

3]. It encompasses not only the material remains of past industrial activity but also the associated values and meanings that shape contemporary approaches to urban development and the identity of local communities [

4,

5,

6]. Areas formerly occupied by industry, particularly heavy or extractive industry—such as the Rust Belt (formerly Steel Belt) in the United States [

7], the Ruhr Area (Ruhrgebiet) in Germany [

8], or Nord–Pas-de-Calais in France [

9]—are recognised as regions with some of the highest potential environmental and public health burdens. In the United States, federal actions under the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act [

10] led to the creation of the so-called Superfund sites—arguably the world’s best-known system for identifying and remediating historical industrial contamination [

10,

11]. This programme has generated extensive insights into the impacts of toxic industrial residues, linking public health protection with spatial management and long-term sustainability policy [

12].

In Europe, particularly in regions that experienced intensive industrialisation—such as the Ruhrgebiet or Nord-Pas-de-Calais—environmental concerns have focused primarily on harmful substances, such as heavy metals, that may have contaminated soil and groundwater [

13]. Examples include the Zollverein coal mine and coking plant complex, inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List in 2001 [

14], and the Nord-Pas-de-Calais Mining Basin, added in 2012 [

15]. In central and eastern Europe, this issue is only beginning to gain wider recognition. One example is the former Gdańsk Shipyard, a representative post-industrial heritage complex with potentially toxic material legacy, protected under the national heritage register and included on the UNESCO Tentative List [

16]. Revitalisation efforts in such post-industrial regions often operate at the landscape scale, with less attention given to the contamination embedded in the fabric of protected buildings [

13], even though many industrial structures possess established cultural values and legal protection.

While integrated approaches to the demolition of post-industrial structures and the management of construction waste contaminated with hazardous substances are increasingly discussed—especially in relation to circular economy and carbon-footprint reduction [

16,

17,

18]—historical contamination within the building fabric of cultural heritage assets slated for preservation remains largely unexplored. Industrial heritage conservation typically prioritises architectural form and aesthetic aspects, while potentially toxic residues of industrial processes—within structures and their immediate surroundings—are rarely treated as structured inputs to conservation planning. This represents a research gap that requires integrating historical, conservation, and environmental-science tools. The absence of a coherent methodology limits the implementation of SDG 11 (“Sustainable Cities and Communities”) and SDG 12 (“Responsible Consumption and Production”), particularly in contexts where degraded brownfields remain underused rather than being safely rehabilitated and reintegrated into social, economic, and cultural systems.

As emphasised during the UNESCO Hangzhou Congress (2013), culture lies at the heart of sustainable development, shaping shared pasts and futures and supporting long-term social and economic development [

19,

20]. The UN 2030 Agenda recognised culture—through heritage and creativity—as a driver supporting the Sustainable Development Goals. In 2015, the UNESCO World Heritage Convention adopted a policy to integrate sustainable development perspectives into its procedures, supporting states, and communities in harnessing potential while safeguarding outstanding universal value [

21].

At the same time, interest in the issue of the so-called hazardous heritage is growing. Substances now recognised as highly dangerous were historically used across industrial facilities and heritage objects and may persist as “silent hazards” that affect both human health and conservation practice. A major recent example is asbestos. Between 2020 and 2022, the Belgian ETWIE Centre and FARO, together with OVAM, documented more than 3500 cases of asbestos-containing heritage items, including items located in actively functioning cultural sites [

22,

23]. This demonstrates that hazards are often hidden and require the combined use of historical research, functional analysis, and specialised chemical testing—while also illustrating how hazardous-heritage challenges intersect with sustainability goals.

In 2021, TICCIH established an expert group dedicated to the industrial heritage of potentially hazardous character [

24]. However, the most widely recognised systemic approaches in Europe have so far focused mainly on museum and collections contexts. This article proposes extending that approach to architecture and urban–industrial heritage, addressing toxic risks embedded at the scale of entire post-industrial buildings and complexes.

Despite growing interest in industrial heritage and environmental risks, there remains a lack of tools to enable an integrated approach to assessing contamination within the architectural fabric of historic buildings. Current research procedures provide robust documentation, yet they rarely incorporate systematic toxicological screening and contamination mapping as inputs to conservation decision-making. Furthermore, CMP does not include structured procedures for identifying, spatially locating, and assessing historical industrial contamination embedded within historic materials. As a result, conservation decision-making systems often operate without transparent hazard classifications, context-sensitive decision thresholds, or decision-support tools. This article proposes an interdisciplinary methodological framework and illustrates its applicability to complex urban–industrial contexts.

2. Theoretical Background

In the past, many substances now recognised as hazardous to human health—currently banned or strictly regulated—were widely used in industry and construction as markers of technological progress. This includes heavy metals, organic compounds (e.g., PCBs and PAHs), mineral and inorganic fibres (e.g., asbestos), and, in some contexts, radioactive materials. These substances were incorporated into preservatives, building materials, and technical equipment and may still remain in heritage fabric as coatings, fillers, wall and structural layers, or operational residues.

Heritage sites containing such hazards constitute what is increasingly described as hazardous (dangerous) heritage, i.e., heritage that poses real physical risks to users, visitors, and conservation staff, rather than interpretative or memory-related challenges associated with “difficult heritage” [

22,

24]. A related concept is legacy pollutants—contaminants left behind by historical industrial activity. Although commonly discussed in relation to soil, groundwater, or air, legacy pollutants may also persist in building materials and migrate into adjacent environments via damaged insulation, paints, sealants, or asbestos-containing components [

10,

12,

16].

Built heritage is vulnerable to long-term exposure to pollutants that accumulate on surfaces and within porous materials, contributing to degradation alongside humidity fluctuations, biological infestation, and insufficient maintenance [

25,

26,

27,

28]. In industrial heritage, this relationship is often dual: sites may be both recipients of external pollution and potential sources of emissions released from preserved installations, materials, and deposits.

Research on hazardous heritage in urban–industrial contexts therefore requires an interdisciplinary perspective combining chemical and toxicological identification with historical and technological reconstruction, industrial archaeology (to locate contamination hotspots), conservation research (to interpret material stratigraphy and vulnerability), and spatial analysis (e.g., GIS). This aligns with the broader trend toward integrated heritage science promoted by Europa Nostra [

29], ICCROM [

30], and TICCIH [

31,

32].

A persistent dilemma concerns the relationship between authenticity and public safety. While conservation doctrine emphasises preserving historic fabric and its material coherence [

33], many authentic layers may contain hazardous components (e.g., asbestos, PCBs, lead, and pesticides). In industrial heritage, traces of use of superimposed finishes and “patina” are also treated as value-bearing evidence, raising the practical question of when risk mitigation can be compatible with minimal intervention and when selective removal becomes unavoidable.

Finally, conservation and repair processes themselves can generate exposure as follows: hazardous substances may be present within binders, paints, and preservatives, or released during cleaning, abrasion, or dismantling. Documented risks for conservators and technicians underline the need for improved identification and risk management procedures [

34,

35,

36,

37]. Consequently, hazardous heritage requires conservation approaches that integrate value assessment with health and environmental protection—an agenda consistent with SDG targets related to public health and sustainable cities and production (e.g., 3.9, 11, and 12.4).

Recent professional debates increasingly emphasise hazardous materials in heritage (e.g., asbestos and biocides) and the need to link hazard identification with conservation decision-making [

38,

39]. In this sense, hazardous heritage is not only a conservation challenge but also a public health and environmental governance issue requiring cross-disciplinary collaboration.

3. Review of Current Research Practices

The conservation of architectural heritage is a multi-stage process that requires careful preparation, a clearly defined methodology, and appropriate supervision. The foundation of this process is a thorough understanding of the building—its history, formal characteristics, construction, materials, and state of preservation. Proper planning and execution of conservation works rely on the consistent application of an established procedure, most often carried out according to the structure of a CMP [

40,

41,

42,

43], [

26] (pp. 247–269), [

27] (pp. 198–209), which includes the following stages:

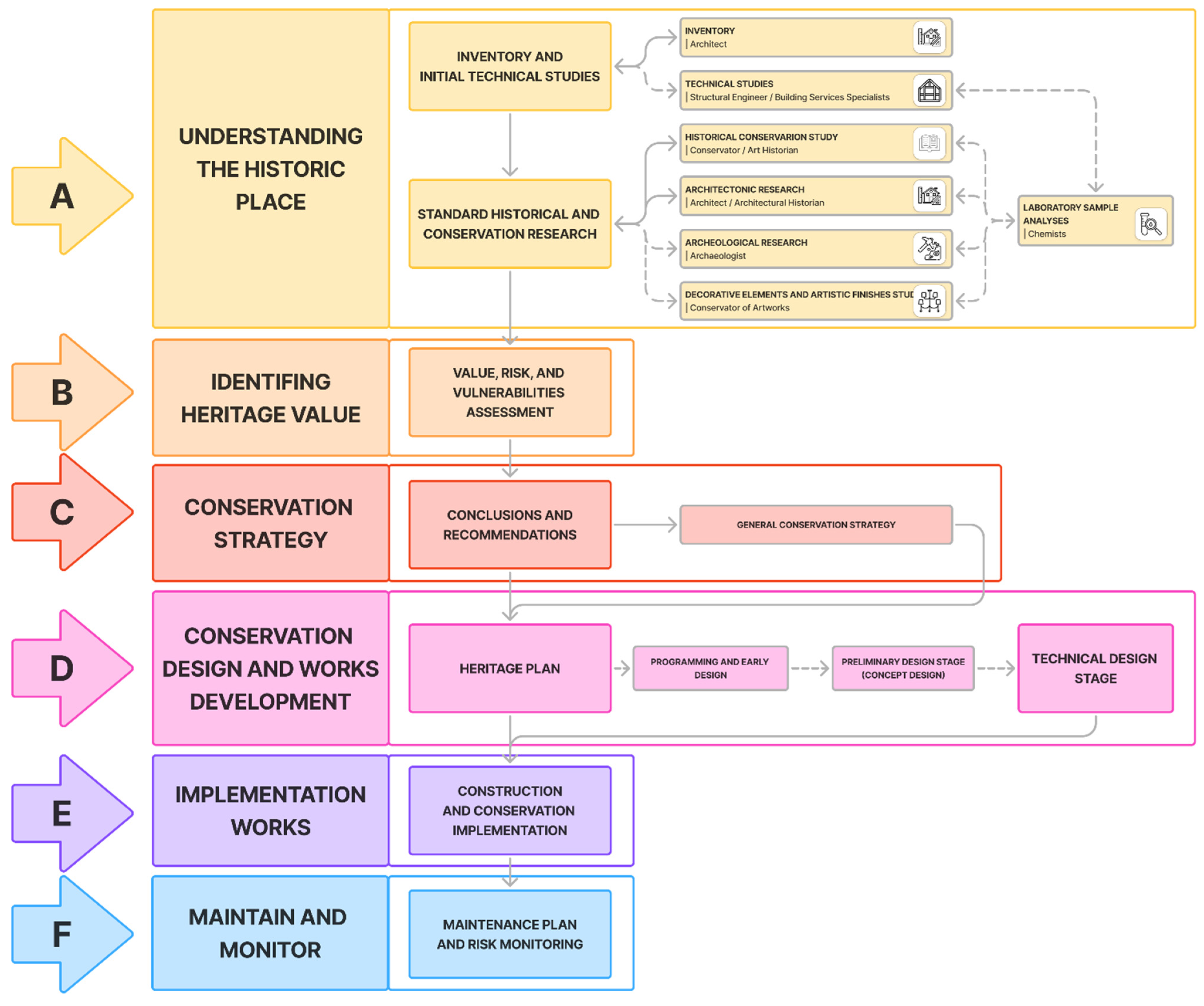

Stage A—Understanding the historic place;

Stage B—Identifying heritage value;

Stage C—Conservation strategy;

Stage D—Conservation design and works development;

Stage E—Implementation works;

Stage F—Maintenance and monitoring.

Contemporary research practices in architectural conservation—including post-industrial heritage—rely on interdisciplinary investigations aimed at producing a comprehensive knowledge base before design decisions are made. Within the CMP logic, the “understanding” stage combines architectural documentation and technical assessments (inventory, condition mapping, identification of materials, and degradation mechanisms), supplemented—where needed—by structural diagnostics, MEP analyses, and safety/stability evaluations undertaken by specialised experts. In parallel, historical and architectural research reconstructs the site’s evolution, typology, and cultural context and supports the identification of authentic layers. Depending on the object, these studies may be expanded to include archaeological research (stratigraphy, subsurface investigations) and analyses of decorative layers. Laboratory testing supports the verification of material technologies and composition, often with the aim of confirming authenticity and explaining deterioration processes.

The synthesis of these investigations results in a Value, Risk, and Vulnerabilities Assessment, which defines the significance of the monument, identifies its values and constraints, and determines conservation priorities and the permissible extent of interventions. This step provides a bridge to the conservation strategy, which translates key findings into recommendations and guidelines. Only then does conservation design and works development begin, including the heritage plan and subsequent design stages (concept, preliminary, and technical design). Based on this research design process, conservation and construction works are implemented, including preservation, stabilisation, and repair, accompanied by on-site verification and post-completion inspection and monitoring. The current research practice in heritage conservation is illustrated in

Figure 1.

Critical Synthesis of Current Research Limitations

In conclusion, contemporary research practice in heritage protection provides robust knowledge on historical, architectural, structural, and material aspects, forming the standard basis for CMP-driven decision-making. However, current CMPs still lack formalised mechanisms to (i) identify and spatially map industrial contaminants embedded in historic materials; (ii) relate contamination characteristics to heritage values, authenticity markers, and material stratigraphy; (iii) define risk categories relevant to conservation works and future use; and (iv) translate contamination-related risks into intervention planning and long-term management strategies.

At the same time, modern standards for cultural heritage management—both at the level of UNESCO, ICOMOS, and ICCROM and in EU urban policy agendas—increasingly emphasise sustainability-oriented conservation. In this context, SDG 11.4 (heritage protection), SDG 12.4 (sound management of chemicals and waste), and SDG 3.9 (reducing exposure to hazardous substances).

This methodological imbalance is particularly problematic for urban–industrial sites, where technological residues may constitute both an operational risk (for workers and users) and a conservation dilemma (for authenticity and integrity). Consequently, conservation decisions may become either overly precautionary—leading to avoidable loss of historic fabric—or insufficiently protective, transferring risks into the implementation and operational phases. These limitations justify the need for an integrated framework that combines historical and conservation research with environmental, chemical, and toxicological investigation, providing a transparent basis for risk-informed, value-sensitive planning—an approach developed in the following sections.

4. Research Problem and Objectives

4.1. Research Problem

Since the early 1990s, post-industrial heritage has attracted growing public interest, as evidenced by numerous projects that adaptively reuse such sites and integrate them into broader urban revitalisation strategies. Scholars consistently emphasise that adaptive reuse is an effective tool for combining the protection of endangered heritage resources with the objectives of sustainable development [

44,

45].

However, in post-industrial sites, this process faces the following fundamental research gap: the lack of systematic methods for identifying and assessing historical industrial contaminants preserved within the building fabric and environmental layers. Undetected pollutants—such as heavy metals, PAHs, PCBs, tar products, residues of oils, paints, and technological processes—may pose risks to human health, influence conservation decisions, and contribute to the degradation of heritage materials.

As a result, conservators and designers often operate under conditions of uncertainty, which hinders effective site management and may lead to misguided design choices. Frequently, unforeseen chemical or environmental hazards necessitate interventions beyond the scope of heritage conservation principles and, in extreme cases, may require remediation measures or even partial or complete demolition. This phenomenon creates a conflict between the following two key principles of contemporary conservation:

the protection of authenticity, understood as the preservation of original material, historical structures, technologies, and layers;

the protection of integrity, referring to the preservation of the overall character, spatial logic, and readability of multilayered fabric.

In contaminated structures, the conservation principle of minimal intervention and maximum preservation can conflict with the need to remove layers produced by industrial activity, which, although “historic”, are toxic to humans and damaging to materials. This raises the following dilemma: which layers should be preserved as historical evidence, and which should be removed for safety reasons?

Existing research initiatives, including the Belgian Hazardous Heritage project, have focused primarily on museum collections and movable artefacts. What is still lacking is an approach oriented toward architectural and urban industrial heritage, especially degraded complexes with prolonged and intensive production histories.

A prominent example of such a complex and insufficiently recognised site is the Gdańsk Shipyard—a designated monument of history of exceptional cultural significance, whose fabric may contain decades of accumulated industrial residues. The presence of such substances—not only in walls and coatings but also in dust deposits and soil layers—confronts conservators with the challenge of reconciling user safety with the preservation of the site’s authenticity.

4.2. Research Objectives

This research aims to develop an integrated interdisciplinary methodology for identifying and assessing historical industrial contaminants in post-industrial heritage sites, with particular attention to multilayered structures, original technologies, and historic materials. This methodology is intended to support decision-making processes that reconcile the protection of authenticity and integrity with the need to ensure human and environmental safety.

The empirical research will focus on selected buildings of the former Gdańsk Shipyard, representing diverse technological processes and different histories of use. This will enable the verification of correlations between types of industrial activities and the nature and distribution of contaminants, as well as testing the model under varied conditions.

The specific objectives include

identifying relationships between historical industrial activity and the presence of contaminants within the heritage fabric;

integrating historical, architectural, and chemical–toxicological analyses into a single coherent research model;

assessing the impact of contaminants on human health and on material degradation processes;

determining how contamination influences conservation decisions concerning the protection of authenticity and integrity;

developing recommendations for sustainable intervention strategies in post-industrial heritage sites;

testing the methodology on a complex example of urban–industrial heritage and evaluating its potential for adaptation to other contexts.

In the longer term, the methodology may serve as a foundation for recommendations in conservation practice, heritage protection policies, and sustainable urban development planning.

4.3. Strategic Relevance and SDG Linkages

The research addresses a key challenge in contemporary heritage management: how to reconcile the preservation of authentic fabric—its layers, technologies, and structures—with the need to remove or neutralise harmful deposits and contaminants resulting from intensive industrial activity. In post-industrial sites, this conflict is particularly pronounced, as “historic” layers are not always “safe” layers.

The proposed approach therefore responds to the following strategic challenge faced by contemporary conservation: how to develop intervention strategies that remain consistent with the principle of minimal intervention while also being environmentally and health responsible.

For this reason, the research has direct relevance for strengthening urban resilience and for implementing the idea of sustainable heritage conservation, understood as a balance between

the protection of authentic material and the integrity of the site;

safeguarding public health and the environment;

the economic and social efficiency of adaptation processes.

The project supports the implementation of the following key Sustainable Development Goals: SDG 3—Good Health and Well-being, SDG 11—Sustainable Cities and Communities, and SDG 12—Responsible Consumption and Production.

The methodology developed through this research can contribute to the creation of responsible, informed, and long-term conservation strategies for post-industrial sites—places that function simultaneously as carriers of cultural value and as potential sources of risk.

5. Proposed Interdisciplinary Methodological Framework

The article proposes a methodological framework that bridges the research procedures traditionally applied within the CMP structure with the specific challenges and needs of post-industrial heritage sites. In the context of historic industrial areas—where the heritage fabric can simultaneously constitute a carrier of multilayered history and a potential source of chemical hazards—conventional conservation tools prove insufficient.

The proposed methodology aims to develop an integrated, interdisciplinary research approach that enables the identification, analysis, and assessment of risks resulting from historical contamination in industrial heritage sites. This method serves both as a tool for diagnosing the problem and as a basis for formulating a model of sustainable conservation that reconciles the protection of authenticity and integrity with the need to ensure human and environmental safety.

5.1. Research Approach and Framework Development (Materials and Methods)

The proposed hazard-aware framework was developed by using the CMP as a procedural baseline and then systematically extending it to address the specific conditions of contaminated post-industrial heritage. Although CMP documents are locally adapted, they share the following common stage-based logic: evidence is progressively built through historical research, on-site surveys, and targeted diagnostics, and then translated into value assessment, conservation strategy, and design development. A key limitation of this baseline is that CMP workflows do not include structured procedures for screening, verifying, and spatially documenting hazardous substances embedded in historic fabric, nor for translating contamination constraints into risk categories and intervention planning.

Accordingly, framework development followed three linked steps:

Identification of interdisciplinary components: the literature and practice in industrial and hazardous heritage were reviewed to define the minimum evidence streams required to treat contamination as both a health risk and a conservation constraint. This resulted in the following three core components: (i) historical and archival reconstruction of technologies, functions, and likely contamination sources; (ii) architectural and conservation research defining material stratigraphy, authenticity markers, and vulnerability; and (iii) laboratory analyses confirming contaminant type and condition.

Analytical expansion of CMP: the CMP stages were analysed as a decision architecture and supplemented with hazard-oriented tasks and outputs (hazard localisation, exposure scenarios during works and future use, risk categorisation, and links to heritage value reasoning), while remaining compatible with conservation principles such as minimal intervention.

Case-informed calibration: the former Gdańsk Shipyard—within the ongoing Dangerous Heritage project—provides the empirical setting for operationalising and calibrating Stages A–C, testing whether interdisciplinary findings can be consistently translated into value–risk categories and intervention pathways across different functions, materials, and historical phases.

Across these steps, GIS-based mapping and CIDOC CRM–based semantic modelling serve as cross-cutting integration tools, ensuring traceable links between historical functions, material layers, laboratory-confirmed contaminants, and conservation planning outputs. At the current conceptual stage, GIS is presented as an integration layer; the specific platform and software version will be specified upon implementation during the empirical phase. The framework is conceptually developed and structurally validated; full empirical implementation is underway and will support further refinement, including the later accommodation of quantitative thresholds where evidence and context-specific regulations allow.

5.2. Rationale and Novelty of the Approach

In light of the identified research gaps, it becomes necessary to develop a method that integrates historical, architectural, conservation, and chemical–toxicological data into a single, coherent diagnostic system. Although current CMP-oriented procedures are advanced in terms of historical and material investigation, they rarely provide formalised steps for identifying, mapping, and assessing industrial contamination embedded in the heritage fabric, nor for translating contamination-related constraints into conservation strategy and intervention planning.

The proposed approach introduces an innovation to conservation practice and research on post-industrial heritage through the three-pillar interdisciplinary integration of data, comprising

Historical and source-based analyses, enabling reconstruction of technological processes, identification of functional zones and localisation of technological stations, their transformations, and potential sources of contamination;

Conservation, architectural, and stratigraphic studies, examining structures, materials, historical layers, and industrial deposits, correlated with subsequent phases of use;

Chemical and toxicological laboratory analyses, identifying contaminants and characterising their impacts on heritage materials and human health.

What is added to the CMP logic is not only the inclusion of chemical evidence, but a structured linkage between contamination evidence and conservation reasoning. The framework formalises (i) contamination screening and spatial mapping as a CMP input, (ii) hazard characterisation and exposure scenarios (during works and future use), (iii) value–risk integration through heritage value weighting and material vulnerability assessment, and (iv) explicit intervention pathways and management actions within the conservation strategy.

A key methodological principle is the use of context-sensitive decision thresholds, rather than universal numerical limits. Thresholds are derived from contaminant type and behaviour, exposure scenario, material vulnerability, and the heritage significance of the affected layer. This allows the same laboratory result to be interpreted differently depending on whether it concerns a critical authenticity marker, a contributory layer, or a non-significant later addition, and whether exposure occurs during invasive works or in long-term use.

The novelty of the proposed method lies in integrating these domains within a uniform documentation system based on (i) GIS-based mapping, localising contaminants in relation to functions and historical development phases; and (ii) CIDOC CRM ontological modelling, representing relationships among materials, technological processes, conservation activities, and the condition of heritage fabric.

As a result, the framework generates decision-support outputs that are traceable and auditable, including (i) a contamination-informed knowledge base (mapped hotspots and material-layer attribution), (ii) value–risk categories and a value–risk matrix, (iii) intervention pathways (e.g., retain with monitoring, stabilise/encapsulate, isolate with controlled access, and selective removal when necessary), and (iv) implementation and monitoring requirements (safe-work protocols, documentation rules, and long-term management measures).

From Problem Identification to Decision-Making Logic

The proposed framework addresses the identified gaps by introducing a structured sequence of analytical and decision-making steps (Stages A–C) that explicitly links contamination identification, heritage value assessment, and risk evaluation. Specifically, Stage A produces a contamination-informed knowledge base; Stage B integrates heritage value assessment with hazard characterisation; and Stage C translates these findings into conservation and risk management strategies. The framework introduces context-sensitive decision thresholds (rather than fixed numerical limits) derived from contaminant type, exposure scenario, material vulnerability, and heritage value. At this stage, it does not prescribe universal numerical thresholds; instead, it establishes a structured decision logic that can accommodate quantitative limits once they become available through empirical testing and context-specific regulatory requirements. The aim of this study is not to resolve all toxicological questions but to provide a structured method through which such questions can be systematically addressed within conservation practice, and—where evidence allows—translated into decision categories, intervention pathways, and monitoring requirements.

To establish a direct problem-to-solution connection, interdisciplinary findings are translated into a precise decision pathway. Historical and archival reconstruction identifies potential sources and spatial logic of contamination; conservation and architectural studies define material stratigraphy, authenticity markers, and vulnerability; and laboratory analyses confirm contaminant presence and characteristics. These datasets are integrated through GIS-based mapping and CIDOC CRM-based semantic modelling to produce a structured decision layer combining (i) hazard characterisation, (ii) exposure scenarios (during works and future use), and (iii) heritage value and authenticity weighting.

Risk evaluation and decision thresholds are operationalised through a transparent classification logic. First, contaminants and affected materials are assigned to hazard categories (e.g., based on toxicity profile, persistence, and potential for release), while exposure is assessed under defined scenarios for both implementation works and post-adaptation use. Second, heritage significance is weighted by the role of the affected element in expressing authenticity and integrity (e.g., critical/high/contributory value). These components are then combined into an integrated value–risk matrix, which establishes decision thresholds that trigger corresponding intervention pathways—from preservation with monitoring, through stabilisation/encapsulation (lock-in) and isolation with controlled access, to selective removal only when necessary. In this way, the framework provides planning logic and decision-support outputs that inform intervention selection, implementation protocols, documentation requirements, and long-term management. The following section operationalises this logic by presenting the complete stage-based structure of the framework (A–F) and detailing the objectives, tasks, and outputs of each stage.

5.3. New Methodological Framework

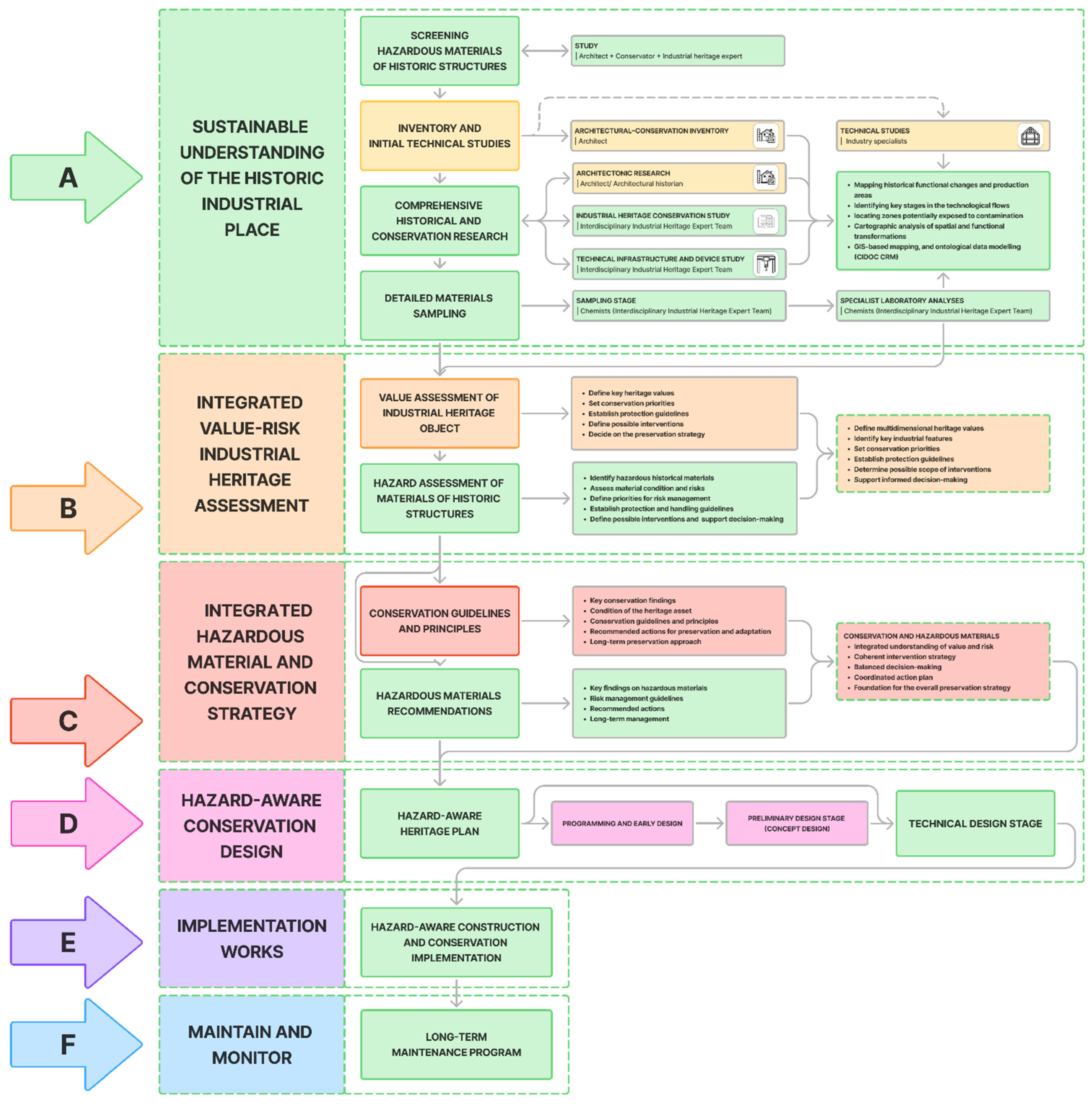

The proposed framework consists of the following six sequential stages:

Stage A—Sustainable understanding of the historic industrial place;

Stage B—Integrated value–risk industrial heritage assessment;

Stage C—Integrated hazardous material and conservation strategy;

Stage D—Hazard-aware conservation design;

Stage E—Implementation works;

Stage F—Maintain and monitor.

The overall structure of the proposed hazard-aware interdisciplinary methodological framework for industrial heritage conservation is illustrated in

Figure 2.

The innovative aspect of this approach lies in an expanded, interdisciplinary initiating phase aimed at achieving a comprehensive, sustainable understanding of an industrial heritage site, taking into account risks arising from historical contamination, industrial technologies, and functional transformations. The first and overarching stage (A)—Sustainable Understanding of the Historic Industrial Place—is a multi-step diagnostic process that integrates historical, architectural–conservation, and chemical investigations into a coherent analytical system. It combines traditional research procedures with GIS tools and ontological data modelling, forming the basis for subsequent value and risk assessment.

The process begins with screening hazardous materials of historic structures, based on an analysis of the building’s construction period, the industrial technologies used at the time, historical production layouts, and the characteristics of the building materials. This allows the identification of initial categories of potential contaminants and the areas where their occurrence is most likely. This is followed by inventory and initial technical studies, including documentation of the structure, materials, damage, and condition, using 3D scanning, photogrammetry, and traditional methods. When needed, these are complemented by diagnostics of the structural system, installations, or physicochemical properties of materials. The result is a complete picture of the building’s physical substance, forming the basis for interpreting its industrial history and subsequent hazard mapping. The next component is comprehensive historical and conservation research, which—given the nature of industrial heritage—requires reconstructing former production processes and related spatial transformations. This includes analysing the chronology and development phases of the site, identifying historical functions of individual buildings, reconstructing technological production lines, documenting surviving industrial infrastructure, and determining its links to potential sources of contamination. These studies draw on archival, iconographic, and cartographic sources as well as technical documentation. Based on these investigations, a detailed materials sampling programme is designed to target locations and layers most likely to contain contamination. Sampling leads to specialist laboratory analyses, including asbestos fibre identification, heavy metal spectrometry, VOC chromatography, and analyses of industrial residues such as PCBs, PAHs, and tar derivatives. The results allow for accurate identification of hazardous substances and an assessment of their scale and distribution. All collected data are then integrated into a unified documentation system using GIS and ontological modelling (CIDOC CRM). This enables the mapping of functional changes, localisation of hazard zones, reconstruction of technological flows, and the building of relationships between spatial structure, production history, and chemical test results. The outcome is a multilayered, spatially and semantically coherent understanding of the site, which serves as the foundation for the subsequent methodological stages.

The second stage of the methodology, (B) integrated value–risk industrial heritage assessment, aims to link the following two complementary perspectives: the assessment of industrial heritage values and the analysis of risks arising from historical contamination embedded in its fabric. This stage is a key moment when two knowledge domains intersect as follows: understanding the significance of the heritage site and diagnosing material, structural, and environmental risks. In parallel, a value assessment of the industrial heritage object is carried out. This analysis covers the identification of hazardous substances, the evaluation of their extent, distribution and degree of degradation, and the assessment of their impact on human safety and the durability of heritage materials. Particular emphasis is placed on identifying toxic, corrosive, or biologically active substances that may cause structural degradation or force interventions that conflict with established conservation principles. Priorities for handling these materials are also assessed—from the need to secure, stabilise, or encapsulate, to procedures for controlled removal—always in relation to their impact on the preservation of the object’s authenticity and integrity. This stage also includes an analysis of available protective measures and safe working methods for implementation teams. As a result, the integrated value–risk assessment combines heritage value protection with the evaluation of chemical and technical hazards. Bringing these two perspectives together enables the formulation of coherent conservation priorities that simultaneously safeguard key cultural values and minimise risks to people and to the heritage fabric. This stage lays the foundation for the next step in the methodology—the development of an integrated strategy for conservation and hazardous-material management.

The third stage (C) of the proposed methodology is the integrated hazardous material and conservation strategy, which represents the point at which heritage value assessments are linked to the diagnosis of chemical, technological, and material risks. This stage aims to develop a coherent conservation strategy that balances the protection of authentic fabric and the integrity of the site with the need to ensure human and environmental safety. The strategy comprises the following two interconnected modules: conservation guidelines and principles and hazardous materials recommendations. Only their combination yields a complete, interdisciplinary plan for managing heritage sites contaminated with historical industrial residues. The first module (conservation guidelines and principles) focuses on the heritage resources requiring protection. It includes an assessment of the building’s condition—structural stability, material durability, and the degree of degradation. On this basis, conservation principles and guidelines are formulated, oriented toward preserving the industrial character of the site, its spatial and technological logic. Particular emphasis is placed on preserving original material layers (where safe), maintaining the legibility of historical technical solutions and protecting essential spatial and functional relationships. This module also includes recommendations for conservation and adaptation—defining the actions needed to maintain the heritage fabric in good condition and identifying priority interventions necessary for long-term preservation. A long-term conservation strategy is also developed, specifying the framework for phasing, use, and continued monitoring.

The second module (hazardous materials recommendations) focuses on the hazardous substances identified during diagnostic and laboratory analyses. Based on the types and distribution of contaminants, guidelines for risk management are developed, including principles of stabilisation, encapsulation, monitoring, or—where necessary—controlled removal. These guidelines also cover safe access procedures, safe work protocols, and documentation requirements during conservation and construction activities. Recommendations are also formulated for handling sensitive or easily damaged materials, including

securing or stabilising brittle, friable, or deteriorated materials;

safe removal where required for health reasons;

lock-in or encapsulation, which is consistent with the principle of minimal intervention;

ensuring compliance with relevant regulations and specialist protocols.

This module also develops a long-term hazardous material management strategy, including monitoring areas where contaminants may persist, controlling access to such zones, and documenting changes in the materials and their surroundings.

Stage C forms the foundation for the subsequent phases: (D) hazard-aware conservation design, (E) implementation works, and (F) maintain and monitor. These successive phases of the proposed methodology involve translating the results of the integrated value–risk assessment (Stages A–C) into concrete design actions (D), addressing both heritage values and material hazards; their execution in accordance with the principle of minimal intervention and with continuous control of the impact of undertaken works on the historic fabric and its authenticity (E); and ensuring long-term maintenance, monitoring, and risk management, which allows for the preservation of both the heritage substance and the implemented contamination management solutions (F).

Together, these phases constitute the practical implementation of the developed protection strategy, carried out in an informed, controlled manner and fully aligned with the principles of sustainable conservation, as illustrated in

Figure 2.

5.4. Summary of the Proposed Methodological Framework

The proposed methodology constitutes an integrated model for protecting post-industrial heritage, combining the analysis of cultural values with the assessment of risks arising from historical contamination. Structured in six stages (A–F), it begins with an interdisciplinary diagnosis of the site, encompassing historical, conservation, technical, and laboratory studies, integrated through the use of GIS tools and ontological data modelling (CIDOC CRM). This makes it possible to obtain a multilayered understanding of the site, presented as a matrix linking historical functions, contaminant types and locations, and the corresponding conservation interventions. This serves as the basis for a further integrated assessment of values and risks and for the development of a coherent strategy to protect the heritage fabric, including the management of hazardous materials. The model enables the reconciliation of authenticity and integrity with the need to ensure human and environmental safety, offering a holistic and sustainable approach to the conservation of post-industrial sites. Geographic Information Systems (GISs) and ontological modelling play a central role in this process by integrating spatial, historical, and environmental data, enabling the mapping of contamination hotspots, the assessment of risks by building type, and the visualisation of pollutants within the architectural stratigraphy.

The proposed methodology has been designed to be scalable, modular, and transferable. It can be applied to various types of industrial heritage, regardless of site scale, location, the nature of historical production processes, or the types of contaminants present. The integration of GIS and ontological tools enables implementation for individual buildings, extensive urban–industrial complexes, and comparative studies. The methodology further supports long-term monitoring and management, particularly in the context of adaptive reuse and strategic planning. As a result, the proposed model constitutes a comprehensive tool that can complement and enhance CMP structures, providing an interdisciplinary foundation for conservation, design, and planning decisions relating to industrial heritage.

5.5. Illustrative Pilot Example: From Evidence to Intervention Pathway

To demonstrate how the framework operates in practice, an illustrative pilot example is provided below. The example shows how evidence generated in Stage A feeds the integrated value–risk assessment (Stage B) and is translated into intervention pathways and management actions within the integrated strategy (Stage C).

As a pilot demonstration of the decision pathway (Stages A–C), preliminary sampling was conducted in a representative late-19th-century production building within the former shipyard area (Object P1, anonymised). The structure historically hosted multiple workshop functions (e.g., woodworking, ropework, and marking), indicating repeated exposure to coatings, lubricants, preservatives, and process-related residues. In line with the framework logic, sampling focused on plaster layers located 30–100 cm above floor level, where long-term deposition and secondary migration of contaminants may occur.

5.5.1. Stage A—Sustainable Understanding of the Historic Industrial Place: Evidence Generation

Historical function screening and architectural–conservation surveys were used to define potential contamination pathways and to select five sampling locations representing different internal zones and operational histories. Laboratory analyses of the plaster samples indicated that concentrations of selected elements (excluding Al and Fe, typical for historic mineral matrices) ranged from 0.1 mg/kg to several hundred mg/kg. Al and Fe reached higher values consistent with historic building materials (up to hundreds of g/kg). Mercury (Hg) was detected at the level of hundreds of μg/kg, with the possibility of locally elevated concentrations (up to a few mg/kg) interpreted as potential secondary contamination linked to successive technological activities and maintenance practices.

5.5.2. Stage B—Integrated Value–Risk Assessment: Classification and Weighting

The sampled plaster layer located 30–100 cm above floor level was classified as contributory heritage fabric (heritage value weighting: contributory), i.e., relevant to the industrial character and material stratigraphy but not a critical authenticity marker. Its vulnerability was assessed in relation to friability and dust generation during works, as well as potential exposure after adaptation. Hazard characterisation and exposure scenarios were combined into qualitative risk categories (low/medium/high) for the following two contexts: (i) restoration/construction works and (ii) post-adaptation use. Rather than prescribing universal numerical thresholds, the pilot applies a transparent classification logic that can later incorporate quantitative limits derived from empirical studies and applicable standards. In this pilot, the contributory value weighting shifts the default response from removal to stabilisation and controlled retention, consistent with minimal intervention principles while addressing worker and user safety.

5.5.3. Stage C—Integrated Strategy: Intervention Pathway and Controls

Based on the combined evidence (hazard class × exposure scenario × heritage value weighting), Object P1 was assigned to an intervention pathway prioritising minimal intervention and retention of historic material wherever feasible, supported by targeted risk controls. Given the contributory value of the sampled plaster, the preferred pathway prioritises retention with stabilisation and exposure control, with selective removal considered only for friable or critically contaminated local zones where encapsulation cannot ensure safety. Recommended actions include (i) stabilisation and encapsulation/lock-in of contaminated plaster layers where they are stable and heritage-relevant; (ii) controlled access and safe-work protocols during interventions to limit dust exposure; and (iii) selective removal only when necessary, limited to friable or critically contaminated local areas where stabilisation cannot ensure safety (

Table 1).

All pilot outputs (sampling points, material layers, laboratory results, and intervention decisions) were structured for GIS mapping and CIDOC CRM-based semantic linking to enable traceable decision-making and future scalability across multiple buildings.

This illustrative application demonstrates how the framework operates as a decision-support system rather than as a predictive model.

5.6. Empirical Basis for Methodological Development: Case Study

The empirical verification of the proposed methodology was based on a case study of a historically complex post-industrial area in northern Poland, encompassing maritime infrastructure, production halls, auxiliary buildings, and technical installations. The site, whose development dates back to the late nineteenth century and includes multiple expansion phases throughout the twentieth century, constitutes a highly representative example of European industrial heritage as follows: it is characterised by a multilayered functional evolution, high intensity of technological processes, and a diverse typology of built structures. Despite its historical and cultural significance, previous research has focused primarily on the early phases of development, often relying on fragmentary sources and selective archival analyses [

46,

47,

48,

49]. Although expert studies on heritage nomination and management planning have been published in recent years [

50,

51,

52], comprehensive field investigations—particularly those addressing environmental degradation and the extent of historical contamination—remain lacking. Similarly, inventories of technical heritage—especially industrial machinery, mechanical infrastructure, and technological equipment—remain incomplete, fragmented, or outdated [

48,

49]. Knowledge of technological transformations and functional changes and their impact on the heritage fabric is limited, which significantly hampers the formulation of adequate protection strategies and risk assessments.

The selection of this particular site as the empirical basis for the study stems from its scientific representativeness. The area combines a complex industrial history with a broad spectrum of construction materials and technological processes, resulting in multifaceted conservation and environmental risks. At the same time, it remains insufficiently investigated, with significant gaps in systematic research concerning both its material condition and the long-term impact of historical industrial activities. This context provides an ideal “real-world laboratory” for testing the proposed approach and for validating tools that integrate historical, architectural, technological, and chemical data.

5.6.1. Scope of Research Activities

To address the identified research gaps, the project adopts an empirical approach grounded in multi-scale, interdisciplinary analyses. Fieldwork and laboratory investigations aim to verify the key components of the proposed methodology, particularly stages (A) sustainable understanding of the historic industrial place, (B) integrated value–risk industrial heritage assessment, and elements of stage (C) integrated hazardous materials and conservation strategy.

The scope of research activities includes

on-site inspections and examination of the heritage fabric, including architectural stratigraphy, preservation state, and structural–material features;

high-resolution spatial documentation using 3D scanning and photogrammetry, enabling precise mapping of deformations, losses, and material layers;

conservation and technical assessments covering the extent of alterations, damage, and the impact of environmental factors on the degradation of building materials;

toxicological and environmental analyses aimed at identifying heavy metals, PAHs, PCBs, biocides, petroleum derivatives, wood preservatives, and residues characteristic of welding, coating, and ship-maintenance processes;

sampling of building materials (brick, concrete, plaster, paints, and timber elements) from areas with the highest likelihood of historical contamination, identified based on technological process analysis;

laboratory analyses conducted according to standards minimising analytical errors, including qualitative and quantitative identification of hazardous substances;

correlation of field data with historical and technological documentation using GIS and ontological modelling (CIDOC CRM) to reconstruct production processes, functional zones, and potential contamination migration pathways.

The empirical phase aims to directly verify the assumptions underlying the proposed method’s stages A–C. The empirical phase validates the framework by testing whether these relationships can be consistently translated into value–risk categories and interpretation pathways across different structures, functions, and material types. Accordingly, the empirical work focuses on the following three validation outputs:

What is the scale, nature, and distribution of historical industrial contaminants that have penetrated the heritage fabric of the former Gdańsk Shipyard, and what potential effects might they have on human health and material durability?

How does the presence of these contaminants influence the planning, extent, and methodology of conservation works, particularly in the context of minimal intervention and the protection of authentic fabric?

Additionally, the research addresses the following three specific questions:

Is there a correlation between the age of a structure, its historical function, and production technology, and how does this influence the type and intensity of accumulated contamination?

How do the type and degree of contamination depend on the characteristics of building materials that may have absorbed them (e.g., brick vs. concrete vs. plaster vs. timber)?

How should knowledge about contamination within the heritage fabric shape conservation decisions—particularly the scope of intervention, work methodology, and safety procedures?

The empirical component of this study forms part of the ongoing research project Dangerous Heritage. Harmful Pollutants and Their Identification in the Substance of an Industrial Monument and its Conservation Protection Model, conducted by an interdisciplinary team at Gdańsk University of Technology. The project integrates expertise in heritage conservation, architectural and material studies, analytical chemistry, and industrial engineering, enabling comprehensive testing of the proposed methodology. Collaboration with external conservators and specialists in shipyard heritage provides additional expert knowledge essential for interpreting technological processes, historical production flows, and contamination pathways in post-industrial structures. The empirical research serves a dual function:

it validates individual components of the proposed methodology;

it calibrates the integrative tools (GIS + CIDOC CRM), which enable the translation of architectural, historical, and chemical data into a unified decision-making model.

As such, the project constitutes a pioneering example of combining architectural history, industrial technology, and analytical chemistry with conservation practice—opening new possibilities for the protection of post-industrial heritage on an international scale.

5.6.2. Rationale for Site Selection and Adaptive Potential

The selected research area combines a well-documented historical evolution, spatial complexity, and typological diversity of built structures, making it particularly suitable for testing the proposed approach. Its multilayered character—encompassing different technological periods, shifting production functions, and varied building materials—allows for detailed mapping of contamination patterns in relation to industrial processes and the chronology of transformations. Such a configuration enables an in-depth understanding of contamination dynamics within heritage structures and supports the verification of tools that integrate historical, spatial, and chemical data.

The findings and tools developed through this case study have a high adaptive potential. The methodology can be applied to other post-industrial heritage sites, especially those facing simultaneous conservation, environmental, and social challenges. The project thus serves as a pilot, advancing contemporary conservation science in the context of sustainable revitalisation and the management of post-industrial landscapes, in alignment with the objectives of the Sustainable Development Goals, particularly SDG 11 and SDG 12.

6. Discussion: Implications, Transferability, and Limitations

The proposed methodology has significance beyond the analysed case. Its modular structure and the integration of spatial, historical, and chemical evidence make it scalable and transferable across other post-industrial heritage contexts, including steelworks, refineries, chemical plants, seaports, railway areas, or power plants—sites that face comparable challenges related to the accumulation of historical contaminants and the need to preserve the heritage fabric.

By combining GIS-based diagnostics, semantic integration (CIDOC CRM), and value–risk reasoning, the framework can support urban policy and spatial planning by making contamination legible as a heritage-relevant constraint rather than an external technical problem. This is particularly important for adaptive reuse, where risk management decisions shape accessibility, permissible functions, and long-term maintenance burdens.

At the same time, transferability depends on the availability of minimally comparable inputs (baseline documentation, sampling access, and contextual industrial histories). Without these, the framework functions primarily as a qualitative decision scaffold and its outputs should be treated as provisional, with uncertainty explicitly documented. In this sense, the framework contributes to SDG 11 and SDG 12 not only by supporting reuse, but by enabling transparent trade-offs between conservation priorities and environmental/health constraints.

Limitations, Uncertainty, and Future Research

At its current stage, the framework is designed to structure conservation decision-making under contamination uncertainty rather than to exhaustively characterise all pollutants across a site. It therefore prioritises decision relevance (where contamination influences interventions, access, and future use) over complete environmental profiling.

A key limitation is reliance on chemical and toxicological analyses. Where laboratory testing is not feasible, the framework can only be implemented partially, effectively reverting to a conventional CMP pathway with reduced hazard sensitivity and higher residual uncertainty. A second limitation concerns local calibration: contaminant behaviour, exposure pathways, and material vulnerability vary with industrial history, technological regimes, and later alterations, meaning that decision categories must be adjusted to site-specific conditions.

The approach also introduces implementation constraints as follows: it requires interdisciplinary coordination and explicit documentation of uncertainty (e.g., sampling coverage, representativeness of layers, and confidence levels in hazard mapping). Without these safeguards, risk may be mischaracterised—leading either to the avoidable loss of historic fabric or to exposure being transferred into construction and operational phases.

Future research will therefore focus on (i) empirical calibration and validation across multiple building types and functions, (ii) developing context-sensitive decision thresholds and confidence metrics, and (iii) producing transferable decision-support outputs (value–risk matrices, intervention pathways, and monitoring protocols) that can be operationalised within conservation planning and procurement workflows.