Regional Disparities in Artificial Intelligence Development and Green Economic Efficiency Performance Under Its Embedding: Empirical Evidence from China

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Evaluation System

3.1. Evaluation System for the Level of Development of the Entire AI Chain

3.2. Evaluation System for AI-Embedded Regional Economic Green Development Efficiency

4. Methodology

4.1. Entropy Weight TOPSIS

- (1)

- To determine the weights of the indicators, the entropy weighting method, with the following steps, is used:

- ➀

- Let represent the set of evaluation objects, denote the set of evaluation indicators, and indicate the raw data of the evaluation indicator in the evaluation object

- ➁

- Since the original indicator data contain zero values, the Min-Max scaling method is applied for intervalization to prevent distortion of entropy weights and avoid computational issues in subsequent steps. This process is implemented using the SPSSAU tool (https://spssau.com/index.html, accessed on 6 January 2026), which scales the data into the conventional [0, 1] range. The transformation formula for positive indicators is as follows. The intervalization effectively eliminates the influence of measurement units while preserving the distributional characteristics and relative relationships of the original data.

- ➂

- Calculate the percentage of characteristics of the province under the indicator, denoted as

- ➃

- Calculate information entropy

- ➄

- Determine the weight of the evaluation index

- (2)

- Multicriteria evaluation using the TOPSIS method. The steps are as follows:

- ➀

- Let represent the set of evaluation objects, denote the set of evaluation indicators, and denote the raw data of the evaluation indicator in the evaluation object .

- ➁

- The reverse indicators are transformed into positive indicators, and for simplicity, is still used in the following steps instead of

- ➂

- Construct vector normalization matrix by dividing each column element by the corresponding column parameter:

The resulting normalization matrix is as follows:- ➃

- Determine the positive and negative ideal solutions corresponding to each evaluation index and represent the maximum and minimum values of column , respectively, in normalization matrix , as follows:

The positive ideal solution is as follows:The negative ideal solution is as follows:- ➄

- Calculate the Euclidean distance from each province to the positive and negative ideal solutions:

where represents the weight of the evaluation index and the weight of each index is determined by the entropy weighting method.- ➅

- Calculate the proximity of the combined results of each province to the positive ideal solution:

where ; the closer is to 1, the better the performance of the evaluated entity; and the ranking is determined by the degree of proximity.

4.2. BCC Model of DEA (DEA-BCC)

5. Data

6. Empirical Results

6.1. Empirical Analysis

6.2. Robustness Checks

7. Conclusions

7.1. Findings

7.2. Policy Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Veselov, G.; Tselykh, A.; Sharma, A.; Huang, R. Applications of artificial intelligence in evolution of smart cities and societies. Informatica 2021, 45, 603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thamik, H.; Wu, J. The impact of artificial intelligence on sustainable development in electronic markets. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, M.; Dall’erba, S.; Ye, M. Spatial and temporal evolution of the chinese artificial intelligence innovation network. Sustainability 2022, 14, 5448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battaglini, F. Will the European green deal enhance Europe’s security towards Russia? A political economy perspective. Energy Econ. 2024, 134, 107551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Lyu, Y.; Li, Y.; Geng, Y. Digital economy: An innovation driving factor for low-carbon development. Eviron. Impact Assess. Rev. 2022, 96, 106821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, I.; Jeon, G.; Piccialli, F. From artificial intelligence to explainable artificial intelligence in industry 4.0: A survey on what, how, and where. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2022, 18, 5031–5042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Sandoval, L.; Crystal-Ornelas, R.; Mousavi, S.M.; Wang, J.; Lin, C.; Cristea, N.; Tong, D.; Carande, W.H.; Ma, X.; et al. A review of earth artificial intelligence. Comput. Geosci. 2022, 159, 105034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, L.; Yang, Z.; Irfan, M.; Ding, C.J.; Hu, M.; Hu, J. Toward low-carbon sustainable development: Exploring the impact of digital economy development and industrial restructuring. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2024, 33, 2159–2172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Yu, Z.; Hu, S. Digital economy, human capital accumulation, and corporate green total factor productivity: Based on strategic emerging industries. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2025, 103, 104152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Yuan, P.; Dong, X. How does the digital economy affect green total factor productivity?—Based on the urban cluster perspective. Econ. Chang. Restruct. 2025, 58, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Kanaujia, A.; Singh, V.K.; Vinuesa, R. Artificial intelligence for sustainable development goals: Bibliometric patterns and concept evolution trajectories. Sustain. Dev. 2024, 32, 724–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, T.; Li, J.; Shi, X.; Li, X.; Chen, Y. Is artificial intelligence associated with carbon emissions reduction? Case of China. Resour. Policy 2023, 85, 103892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdalla, A.N.; Nazir, M.S.; Tao, H.; Cao, S.; Ji, R.; Jiang, M.; Yao, L. Integration of energy storage system and renewable energy sources based on artificial intelligence: An overview. J. Energy Storage 2021, 40, 102811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilar, J.; Garces-Jimenez, A.; R-Moreno, M.D.; García, R. A systematic literature review on the use of artificial intelligence in energy self-management in smart buildings. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 151, 111530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cepeliauskaite, G.; Keppner, B.; Simkute, Z.; Stasiskiene, Z.; Leuser, L.; Kalnina, I.; Kotovica, N.; Andiņš, J.; Muiste, M. Smart-mobility services for climate mitigation in urban areas: Case studies of baltic countries and Germany. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yigitcanlar, T.; Mehmood, R.; Corchado, J.M. Green artificial intelligence: Towards an efficient, sustainable and equitable technology for smart cities and futures. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyriakarakos, G. Artificial Intelligence and the Energy Transition. Sustainability 2025, 17, 1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Yang, Z.; Lo, D. Efficient and Green Large Language Models for Software Engineering: Literature Review, Vision, and the Road Ahead. ACM Trans. Softw. Eng. Methodol. 2025, 34, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dauvergne, P. The globalization of artificial intelligence: Consequences for the politics of environmentalism. Globalizations 2021, 18, 285–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J. A configurational analysis of innovation environment and industrial green total factor productivity. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2025, 68, 3385–3410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Z.; Chen, Y.; Tang, Z.; Yang, J. Environmental governance’s effect on green total factor productivity in the Yangtze River Economic Belt, China. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2025, 27, 17557–17583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rammer, C.; Fernández, G.P.; Czarnitzki, D. Artificial intelligence and industrial innovation: Evidence from German firm-level data. Res. Policy 2022, 51, 104555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Almeida, P.G.R.; dos Santos, C.D.; Farias, J.S. Artificial intelligence regulation: A framework for governance. Ethics Inf. Technol. 2021, 23, 505–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babina, T.; Fedyk, A.; He, A.; Hodson, J. Artificial intelligence firm growth product innovation. J. Financ. Econ. 2024, 151, 103745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crompton, H.; Burke, D. Artificial intelligence in higher education: The state of the field. Int. J. Educ. Technol. High. Educ. 2023, 20, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alahakoon, D.; Nawaratne, R.; Xu, Y.; Dem Silva, D.; Sivarajah, U.; Gupta, B. Self-building artificial intelligence and machine learning to empower big data analytics in smart cities. Inf. Syst. Front. 2023, 25, 221–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, S.C.; Wu, A.W.; Yu, H.C.; Wu, H.C.; Kuo, Y.P.; Chen, P.X. Public perception of artificial intelligence and its connections to the sustainable development goals. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Rasoulinezhad, E. Role of natural resources utilization efficiency in achieving green economic recovery: Evidence from BRICS countries. Resour. Policy 2023, 80, 103164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, F.; Hu, M.; Gao, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhu, J.; Pan, Y. How does digital economy affect carbon emissions? Evidence from global 60 countries. Sci. Total Eviron. 2022, 852, 158401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaya, T.; Kahraman, C. Multicriteria decision making in energy planning using a modified fuzzy TOPSIS methodology. Expert Syst. Appl. 2011, 38, 6577–6585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banker, R.D.; Charnes, A.; Cooper, W.W. Some models for estimating technical and scale inefficiencies in data envelopment analysis. Manag. Sci. 1984, 30, 1078–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1st Order Dimension | 2nd Order Dimension | Meaning of Indicators | Data Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| AI Industry Capability Level | Enterprise Capability Level | Number of AI-listed firms (Unit: one) | PPData database |

| Human Capacity | Number of AI Core Human Capital (Unit: one) | PPData database | |

| AI Innovation Capacity Level | Patent Capacity | Number of digital economy-related invention patents granted in the current year (Unit: one) | PPData database |

| Occupation Capacity | Number of Recruitments for 10 types of new occupations in AI (Unit: one) | China Statistical Yearbook | |

| AI Education Capability Level | Subject Capability Level | Number of AI majors in colleges and universities (Unit: one) | China Statistical Yearbook on Science and Technology |

| Knowledge Capability | Number of international papers on AI published by colleges and universities (Unit: one) | China Statistical Yearbook on Science and Technology | |

| AI Environment Capability Level | City Capability Level | Number of smart cities (Unit: one) | PPData database |

| Digital Energy Level | Digital Economy Development Index (Unit: points) | PPData database |

| 1st Order Dimension | 2nd Order Dimension | Meaning of Indicators | Data Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Input dimension | Human input | Number of persons employed in urban non-private units by industry (end of year) (Unit: 10,000 persons) | China Statistical Yearbook |

| Hardware input | Growth of the actual capital available for investment in fixed assets of the whole society over the previous year (Unit: %) | China Statistical Yearbook | |

| Energy input | Total coal consumption (Unit: 10,000 tonnes) | China Energy Statistics Yearbook | |

| Technology Input | Number of AI Technology Input Relationships in Provinces (Unit: one) | PPData database | |

| Capital input | Financing amount of AI enterprises in provinces and municipalities (Unit: 100 million RMB) | PPData database | |

| Scientific research input | Total funding for national AI projects in provincial universities (Unit: million yuan) | China Statistical Yearbook on Science and Technology | |

| Output dimension | Industrial adjustment | The proportion of the province’s tertiary sector (Unit: %) | China Statistical Yearbook |

| Exhaust emissions | Emission of major pollutants in exhaust gas: Sulphur dioxide (Unit: 10,000 tonnes) | China Energy Statistics Yearbook | |

| Waste water emission | Emission of major pollutants in waste water: Chemical Oxygen Demand (Unit: 10,000 tonnes) | China Energy Statistics Yearbook |

| Indicator | Entropy Value | Information Utility Value | Weight Coefficient |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of the AI-listed Firms (Unit: one) | 0.7414 | 0.2586 | 19.33% |

| AI Core Human Capital (Unit: one) | 0.7482 | 0.2518 | 18.82% |

| Number of digital economy-related invention patents granted in the current year (Unit: one) | 0.7674 | 0.2326 | 17.39% |

| Number of recruitments for 10 types of new occupations in AI (Unit: one) | 0.7424 | 0.2576 | 19.25% |

| Number of AI majors in colleges and universities (Unit: one) | 0.9394 | 0.0606 | 4.53% |

| Number of international papers on AI published by colleges and universities (Unit: one) | 0.8432 | 0.1568 | 11.72% |

| Number of smart cities (Unit: one) | 0.9509 | 0.0491 | 3.67% |

| Digital Economy Development Index (Unit: points) | 0.9292 | 0.0708 | 5.29% |

| Ranking | Entropy Weight ([0, 1]) | Subjective and Objective Weighting ([1, 2]) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Beijing | Guangdong |

| 2 | Guangdong | Beijing |

| 3 | Jiangsu | Jiangsu |

| 4 | Shanghai | Zhejiang |

| 5 | Zhejiang | Shandong |

| 6 | Shandong | Shanghai |

| 7 | Hubei | Henan |

| 8 | Sichuan | Hubei |

| 9 | Shaanxi | Sichuan |

| 10 | Anhui | Anhui |

| 11 | Henan | Chongqing |

| 12 | Fujian | Shannxi |

| 13 | Hunan | Liaoning |

| 14 | Chongqing | Hebei |

| 15 | Liaoning | Hunan |

| 16 | Tianjin | Fujian |

| 17 | Hebei | Tianjin |

| 18 | Jiangxi | Jiangxi |

| 19 | Heilongjiang | Jilin |

| 20 | Jilin | Shanxi |

| 21 | Shanxi | Guangxi |

| 22 | Hainan | Heilongjiang |

| 23 | Guangxi | Guizhou |

| 24 | Guizhou | Yunnan |

| 25 | Yunnan | Hainan |

| 26 | Gansu | Gansu |

| 27 | Inner Mongolia | Inner Mongolia |

| 28 | Xinjiang | Xinjiang |

| 29 | Qinghai | Qinghai |

| 30 | Ningxia | Ningxia |

| 31 | Tibet | Tibet |

| Ranking | BCC Score | BCC Ranking | SBM Score | SBM Ranking | CCR Score | CCR Ranking |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beijing | 1.000 | 1 | 1.000 | 1 | 1.000 | 1 |

| Tianjin | 1.000 | 2 | 1.000 | 2 | 1.000 | 2 |

| Shanghai | 1.000 | 3 | 1.000 | 3 | 1.000 | 3 |

| Hainan | 1.000 | 4 | 1.000 | 4 | 1.000 | 4 |

| Yunnan | 1.000 | 5 | 1.000 | 5 | 1.000 | 5 |

| Tibet | 1.000 | 6 | 1.000 | 6 | 1.000 | 6 |

| Qinghai | 1.000 | 7 | 1.000 | 7 | 1.000 | 7 |

| Guizhou | 0.953 | 8 | 0.170 | 12 | 0.953 | 8 |

| Jilin | 0.949 | 9 | 0.155 | 13 | 0.949 | 9 |

| Gansu | 0.948 | 10 | 0.252 | 10 | 0.948 | 10 |

| Liaoning | 0.922 | 11 | 0.264 | 9 | 0.922 | 11 |

| Hebei | 0.912 | 12 | 0.091 | 22 | 0.912 | 12 |

| Ningxia | 0.905 | 13 | 0.345 | 8 | 0.904 | 14 |

| Guangxi | 0.904 | 14 | 0.111 | 17 | 0.904 | 13 |

| Heilongjiang | 0.885 | 15 | 0.100 | 19 | 0.885 | 15 |

| Hubei | 0.861 | 16 | 0.127 | 15 | 0.861 | 16 |

| Henan | 0.860 | 17 | 0.064 | 30 | 0.860 | 17 |

| Chongqing | 0.857 | 18 | 0.127 | 16 | 0.857 | 18 |

| Sichuan | 0.853 | 19 | 0.107 | 18 | 0.853 | 19 |

| Xinjiang | 0.833 | 20 | 0.150 | 14 | 0.833 | 20 |

| Shandong | 0.829 | 21 | 0.089 | 23 | 0.829 | 21 |

| Jiangxi | 0.827 | 22 | 0.097 | 20 | 0.827 | 22 |

| Shaanxi | 0.811 | 23 | 0.084 | 24 | 0.811 | 23 |

| Zhejiang | 0.799 | 24 | 0.095 | 21 | 0.799 | 24 |

| Anhui | 0.787 | 25 | 0.065 | 29 | 0.787 | 25 |

| Inner Mongolia | 0.781 | 26 | 0.172 | 11 | 0.781 | 26 |

| Fujian | 0.780 | 27 | 0.073 | 27 | 0.780 | 27 |

| Guangdong | 0.776 | 28 | 0.080 | 25 | 0.776 | 28 |

| Hunan | 0.764 | 29 | 0.070 | 28 | 0.764 | 29 |

| Shanxi | 0.763 | 30 | 0.076 | 26 | 0.763 | 30 |

| Jiangsu | 0.677 | 31 | 0.051 | 31 | 0.677 | 31 |

| Province | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | Level | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Relative Proximity C | Ranking | Relative Proximity C | Ranking | Relative Proximity C | Ranking | ||

| Beijing | 0.676 | 2 | 0.669 | 2 | 0.832 | 1 | High |

| Guangdong | 0.780 | 1 | 0.792 | 1 | 0.777 | 2 | High |

| Jiangsu | 0.635 | 3 | 0.653 | 3 | 0.375 | 3 | High |

| Shanghai | 0.417 | 5 | 0.396 | 5 | 0.366 | 4 | High |

| Zhejiang | 0.437 | 4 | 0.443 | 4 | 0.319 | 5 | High |

| Shandong | 0.386 | 6 | 0.380 | 6 | 0.196 | 6 | Low |

| Hubei | 0.252 | 8 | 0.232 | 8 | 0.171 | 7 | Low |

| Sichuan | 0.272 | 7 | 0.259 | 7 | 0.165 | 8 | Low |

| Shaanxi | 0.244 | 9 | 0.232 | 9 | 0.149 | 9 | Low |

| Anhui | 0.146 | 15 | 0.147 | 14 | 0.146 | 10 | Low |

| Henan | 0.166 | 13 | 0.161 | 13 | 0.130 | 11 | Low |

| Fujian | 0.207 | 10 | 0.186 | 10 | 0.119 | 12 | Low |

| Hunan | 0.167 | 12 | 0.174 | 12 | 0.112 | 13 | Low |

| Chongqing | 0.129 | 17 | 0.120 | 17 | 0.112 | 14 | Low |

| Liaoning | 0.180 | 11 | 0.177 | 11 | 0.109 | 15 | Low |

| Tianjin | 0.149 | 14 | 0.141 | 15 | 0.104 | 16 | Low |

| Hebei | 0.104 | 18 | 0.103 | 18 | 0.090 | 17 | Low |

| Jiangxi | 0.070 | 23 | 0.077 | 22 | 0.071 | 18 | Low |

| Heilongjiang | 0.144 | 16 | 0.132 | 16 | 0.071 | 19 | Low |

| Jilin | 0.100 | 19 | 0.096 | 19 | 0.065 | 20 | Low |

| Shanxi | 0.077 | 22 | 0.072 | 23 | 0.061 | 21 | Low |

| Hainan | 0.029 | 28 | 0.045 | 28 | 0.057 | 22 | Low |

| Guangxi | 0.084 | 21 | 0.083 | 20 | 0.057 | 23 | Low |

| Guizhou | 0.060 | 25 | 0.067 | 24 | 0.054 | 24 | Low |

| Yunnan | 0.088 | 20 | 0.080 | 21 | 0.052 | 25 | Low |

| Gansu | 0.051 | 27 | 0.050 | 27 | 0.042 | 26 | Low |

| Inner Mongolia | 0.061 | 24 | 0.063 | 25 | 0.040 | 27 | Low |

| Xinjiang | 0.056 | 26 | 0.056 | 26 | 0.032 | 28 | Low |

| Qinghai | 0.012 | 30 | 0.011 | 30 | 0.025 | 29 | Low |

| Ningxia | 0.022 | 29 | 0.022 | 29 | 0.021 | 30 | Low |

| Tibet | 0.003 | 31 | 0.004 | 31 | 0.005 | 31 | Low |

| Province | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | Level | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OE(θ) | Ranking | OE(θ) | Ranking | OE(θ) | Ranking | ||

| Beijing | 1.000 | 1 | 1.000 | 1 | 1.000 | 1 | High |

| Tianjin | 1.000 | 2 | 1.000 | 2 | 1.000 | 2 | High |

| Shanghai | 1.000 | 3 | 1.000 | 3 | 1.000 | 3 | High |

| Hainan | 1.000 | 4 | 1.000 | 4 | 1.000 | 4 | High |

| Yunnan | 0.955 | 9 | 0.959 | 10 | 1.000 | 5 | High |

| Tibet | 1.000 | 5 | 1.000 | 5 | 1.000 | 6 | High |

| Qinghai | 1.000 | 6 | 1.000 | 6 | 1.000 | 7 | High |

| Guizhou | 0.852 | 17 | 0.878 | 17 | 0.953 | 8 | High |

| Jilin | 1.000 | 7 | 0.945 | 12 | 0.949 | 9 | High |

| Gansu | 1.000 | 8 | 1.000 | 7 | 0.948 | 10 | High |

| Liaoning | 0.816 | 21 | 0.869 | 19 | 0.922 | 11 | High |

| Hebei | 0.867 | 16 | 0.924 | 15 | 0.912 | 12 | High |

| Ningxia | 0.919 | 12 | 0.987 | 9 | 0.905 | 13 | High |

| Guangxi | 0.882 | 14 | 0.940 | 13 | 0.904 | 14 | High |

| Heilongjiang | 0.827 | 19 | 0.862 | 20 | 0.885 | 15 | Low |

| Hubei | 0.693 | 29 | 0.988 | 8 | 0.861 | 16 | Low |

| Henan | 0.832 | 18 | 0.874 | 18 | 0.860 | 17 | Low |

| Chongqing | 0.876 | 15 | 0.857 | 21 | 0.857 | 18 | Low |

| Sichuan | 0.787 | 22 | 0.833 | 23 | 0.853 | 19 | Low |

| Xinjiang | 0.922 | 10 | 0.950 | 11 | 0.833 | 20 | Low |

| Shandong | 0.768 | 24 | 0.817 | 24 | 0.829 | 21 | Low |

| Jiangxi | 0.827 | 20 | 0.843 | 22 | 0.827 | 22 | Low |

| Shaanxi | 0.657 | 30 | 0.745 | 29 | 0.811 | 23 | Low |

| Zhejiang | 0.734 | 26 | 0.768 | 27 | 0.799 | 24 | Low |

| Anhui | 0.783 | 23 | 0.814 | 25 | 0.787 | 25 | Low |

| Inner Mongolia | 0.921 | 11 | 0.936 | 14 | 0.781 | 26 | Low |

| Fujian | 0.733 | 27 | 0.787 | 26 | 0.780 | 27 | Low |

| Guangdong | 0.720 | 28 | 0.758 | 28 | 0.776 | 28 | Low |

| Hunan | 0.767 | 25 | 0.735 | 30 | 0.764 | 29 | Low |

| Shanxi | 0.886 | 13 | 0.904 | 16 | 0.763 | 30 | Low |

| Jiangsu | 0.577 | 31 | 0.591 | 31 | 0.677 | 31 | Low |

| Province | Return to Scale | Type |

|---|---|---|

| Beijing | 1.000 | Fixed returns to scale |

| Tianjin | 1.000 | Fixed returns to scale |

| Hebei | 0.911 | Increasing returns to scale |

| Shanxi | 0.804 | Increasing returns to scale |

| Inner Mongolia | 0.788 | Increasing returns to scale |

| Liaoning | 1.004 | Decreasing returns to scale |

| Jilin | 0.975 | Increasing returns to scale |

| Heilongjiang | 0.949 | Increasing returns to scale |

| Shanghai | 1.000 | Fixed returns to scale |

| Jiangsu | 0.963 | Increasing returns to scale |

| Zhejiang | 0.980 | Increasing returns to scale |

| Anhui | 0.860 | Increasing returns to scale |

| Fujian | 0.814 | Increasing returns to scale |

| Jiangxi | 0.848 | Increasing returns to scale |

| Shandong | 0.950 | Increasing returns to scale |

| Henan | 0.893 | Increasing returns to scale |

| Hubei | 1.006 | Decreasing returns to scale |

| Hunan | 0.851 | Increasing returns to scale |

| Guangdong | 0.974 | Increasing returns to scale |

| Guangxi | 0.939 | Increasing returns to scale |

| Hainan | 1.000 | Fixed returns to scale |

| Chongqing | 0.894 | Increasing returns to scale |

| Sichuan | 0.931 | Increasing returns to scale |

| Guizhou | 0.937 | Increasing returns to scale |

| Yunnan | 1.000 | Fixed return to scale |

| Tibet | 1.000 | Fixed return to scale |

| Shaanxi | 0.916 | Increasing returns to scale |

| Gansu | 0.948 | Increasing returns to scale |

| Qinghai | 1.000 | Fixed returns to scale |

| Ningxia | 0.905 | Increasing returns to scale |

| Xinjiang | 0.843 | Increasing returns to scale |

| Model | Item | Non-Standardized Coefficients | Standardized Coefficient β | t | p | 95% CI | Collinearity Diagnosis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | Standard Error | VIF | Tolerance | ||||||

| Layer 1 | β0 | 0.278 ** | 0.097 | - | 2.874 | 0.008 | 0.079~0.476 | - | - |

| X1i | −0.000 ** | 0 | −0.825 | −5.110 | 0 | −0.000~−0.000 | 2.017 | 0.496 | |

| X2i | 0.014 ** | 0.002 | 1.200 | 7.040 | 0 | 0.010~0.018 | 2.245 | 0.445 | |

| X3i | 0.449 | 0.273 | 0.216 | 1.646 | 0.111 | −0.111~1.009 | 1.329 | 0.753 | |

| F Test | F (3,27) = 16.781, p = 0.000 | ||||||||

| R2 | R2 = 0.651, adjusted R2 = 0.612 | ||||||||

| ∆Information | ∆R2 = 0.651, ∆F (3,27) = 16.781, p = 0.000 | ||||||||

| Layered 2 | β0 | 0.199 * | 0.086 | - | 2.321 | 0.028 | 0.023~0.375 | - | - |

| X1i | −0.000 ** | 0 | −0.548 | −3.410 | 0.002 | −0.000~−0.000 | 2.750 | 0.364 | |

| X2i | 0.015 ** | 0.002 | 1.305 | 8.771 | 0 | 0.012~0.019 | 2.352 | 0.425 | |

| X3i | 0.347 | 0.235 | 0.167 | 1.478 | 0.151 | −0.136~0.829 | 1.352 | 0.740 | |

| X4i | −0.233 ** | 0.070 | −0.502 | −3.331 | 0.003 | −0.377~−0.089 | 2.409 | 0.415 | |

| F Test | F (4,26) = 20.065, p = 0.000 | ||||||||

| R2 | R2 = 0.755, adjusted R2 = 0.718 | ||||||||

| ∆Information | ∆R2 = 0.104, ∆F (1,26) = 11.095, p = 0.003 | ||||||||

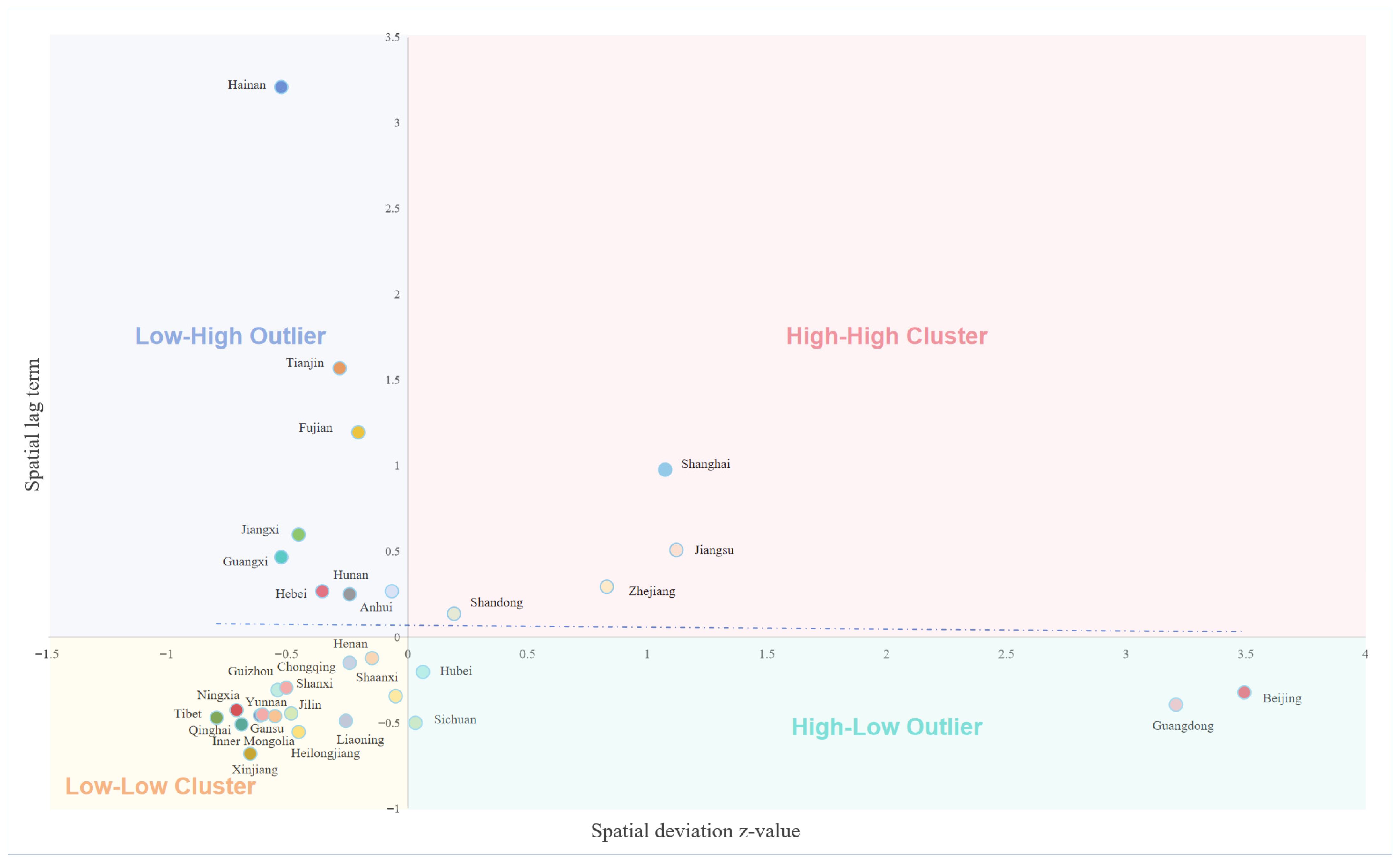

| Province | Local Moran’s I | Expected I | Std. Dev. | Z-Score | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beijing | −1.086 | −0.033 | 1.772 | −0.357 | 0.18 |

| Tianjin | −0.432 | −0.033 | 0.2 | −2.182 | 0.007 |

| Hebei | −0.092 | −0.033 | 0.114 | −0.697 | 0.122 |

| Shanxi | 0.144 | −0.033 | 0.229 | 0.504 | 0.154 |

| Inner Mongolia | 0.272 | −0.033 | 0.164 | 1.869 | 0.015 |

| Liaoning | 0.122 | −0.033 | 0.147 | 0.783 | 0.108 |

| Jilin | 0.209 | −0.033 | 0.276 | 0.734 | 0.116 |

| Heilongjiang | 0.244 | −0.033 | 0.322 | 0.734 | 0.116 |

| Shanghai | 1.016 | −0.033 | 0.756 | 1.464 | 0.036 |

| Jiangsu | 0.551 | −0.033 | 0.512 | 1.293 | 0.049 |

| Zhejiang | 0.236 | −0.033 | 0.359 | 0.795 | 0.107 |

| Anhui | −0.017 | −0.033 | 0.026 | −0.648 | 0.129 |

| Fujian | −0.239 | −0.033 | 0.122 | −2.026 | 0.011 |

| Jiangxi | −0.264 | −0.033 | 0.176 | −1.448 | 0.037 |

| Shandong | 0.026 | −0.033 | 0.091 | 0.414 | 0.17 |

| Henan | 0.018 | −0.033 | 0.059 | 0.327 | 0.186 |

| Hubei | −0.012 | −0.033 | 0.025 | −0.509 | 0.153 |

| Hunan | −0.059 | −0.033 | 0.096 | −0.574 | 0.141 |

| Guangdong | −1.219 | −0.033 | 1.148 | −0.748 | 0.114 |

| Guangxi | −0.239 | −0.033 | 0.255 | −0.964 | 0.084 |

| Hainan | −1.642 | −0.033 | 0.602 | −2.601 | 0.002 |

| Chongqing | 0.035 | −0.033 | 0.117 | 0.305 | 0.19 |

| Sichuan | −0.015 | −0.033 | 0.012 | −1.365 | 0.043 |

| Guizhou | 0.162 | −0.033 | 0.259 | 0.648 | 0.129 |

| Yunnan | 0.247 | −0.033 | 0.267 | 0.904 | 0.092 |

| Tibet | 0.362 | −0.033 | 0.381 | 0.946 | 0.086 |

| Shaanxi | 0.017 | −0.033 | 0.016 | 1.126 | 0.065 |

| Gansu | 0.265 | −0.033 | 0.26 | 1.08 | 0.07 |

| Qinghai | 0.342 | −0.033 | 0.338 | 0.997 | 0.08 |

| Ningxia | 0.294 | −0.033 | 0.424 | 0.724 | 0.117 |

| Xinjiang | 0.433 | −0.033 | 0.32 | 1.335 | 0.045 |

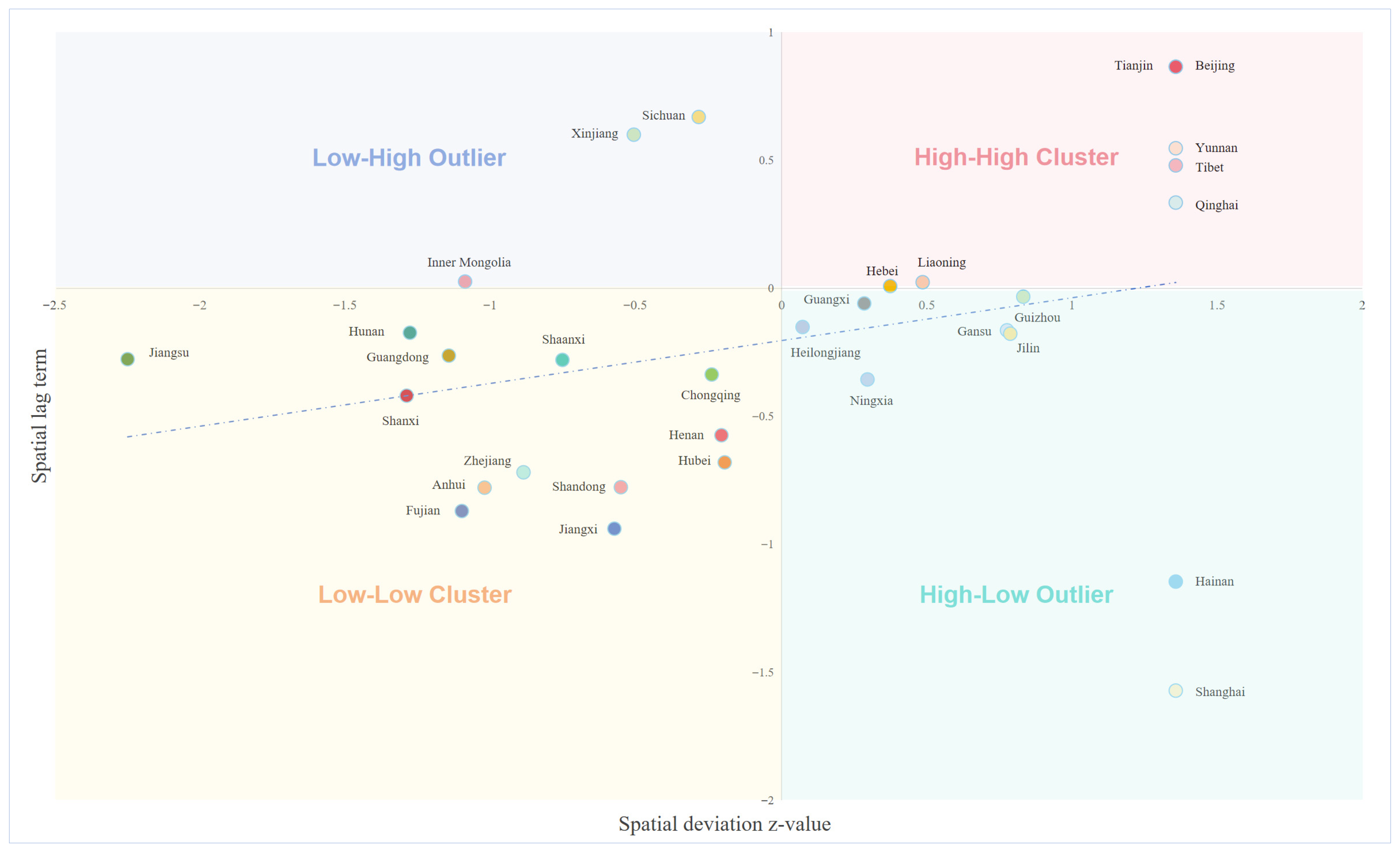

| Province | Local Moran’s I | Expected I | Std. Dev. | Z-Score | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beijing | 1.137 | −0.033 | 0.957 | 1.166 | 0.061 |

| Tianjin | 1.137 | −0.033 | 0.957 | 1.166 | 0.061 |

| Hebei | 0.003 | −0.033 | 0.127 | −0.103 | 0.229 |

| Shanxi | 0.525 | −0.033 | 0.580 | 1.086 | 0.069 |

| Inner Mongolia | −0.027 | −0.033 | 0.275 | 0.133 | 0.224 |

| Liaoning | 0.011 | −0.033 | 0.257 | −0.027 | 0.245 |

| Jilin | −0.136 | −0.033 | 0.410 | −0.369 | 0.178 |

| Heilongjiang | −0.011 | −0.033 | 0.050 | −0.160 | 0.218 |

| Shanghai | −2.064 | −0.033 | 0.919 | −2.112 | 0.009 |

| Jiangsu | 0.605 | −0.033 | 0.854 | 1.024 | 0.076 |

| Zhejiang | 0.620 | −0.033 | 0.311 | 2.186 | 0.007 |

| Anhui | 0.773 | −0.033 | 0.358 | 2.347 | 0.005 |

| Fujian | 0.929 | −0.033 | 0.529 | 1.895 | 0.015 |

| Jiangxi | 0.525 | −0.033 | 0.207 | 2.662 | 0.002 |

| Shandong | 0.417 | −0.033 | 0.234 | 1.898 | 0.014 |

| Henan | 0.116 | −0.033 | 0.075 | 1.631 | 0.026 |

| Hubei | 0.130 | −0.033 | 0.071 | 1.914 | 0.014 |

| Hunan | 0.216 | −0.033 | 0.443 | 0.678 | 0.124 |

| Guangdong | 0.293 | −0.033 | 0.416 | 0.892 | 0.093 |

| Guangxi | −0.016 | −0.033 | 0.124 | −0.200 | 0.210 |

| Hainan | −1.506 | −0.033 | 1.320 | −0.968 | 0.083 |

| Chongqing | 0.079 | −0.033 | 0.089 | 0.946 | 0.086 |

| Sichuan | −0.185 | −0.033 | 0.092 | −1.940 | 0.013 |

| Guizhou | −0.027 | −0.033 | 0.306 | −0.050 | 0.240 |

| Yunnan | 0.718 | −0.033 | 0.581 | 1.323 | 0.046 |

| Tibet | 0.630 | −0.033 | 0.581 | 1.171 | 0.060 |

| Shaanxi | 0.205 | −0.033 | 0.233 | 1.026 | 0.076 |

| Gansu | −0.124 | −0.033 | 0.270 | −0.461 | 0.161 |

| Qinghai | 0.439 | −0.033 | 0.576 | 0.856 | 0.098 |

| Ningxia | −0.102 | −0.033 | 0.157 | −0.616 | 0.134 |

| Xinjiang | −0.296 | −0.033 | 0.223 | −1.306 | 0.048 |

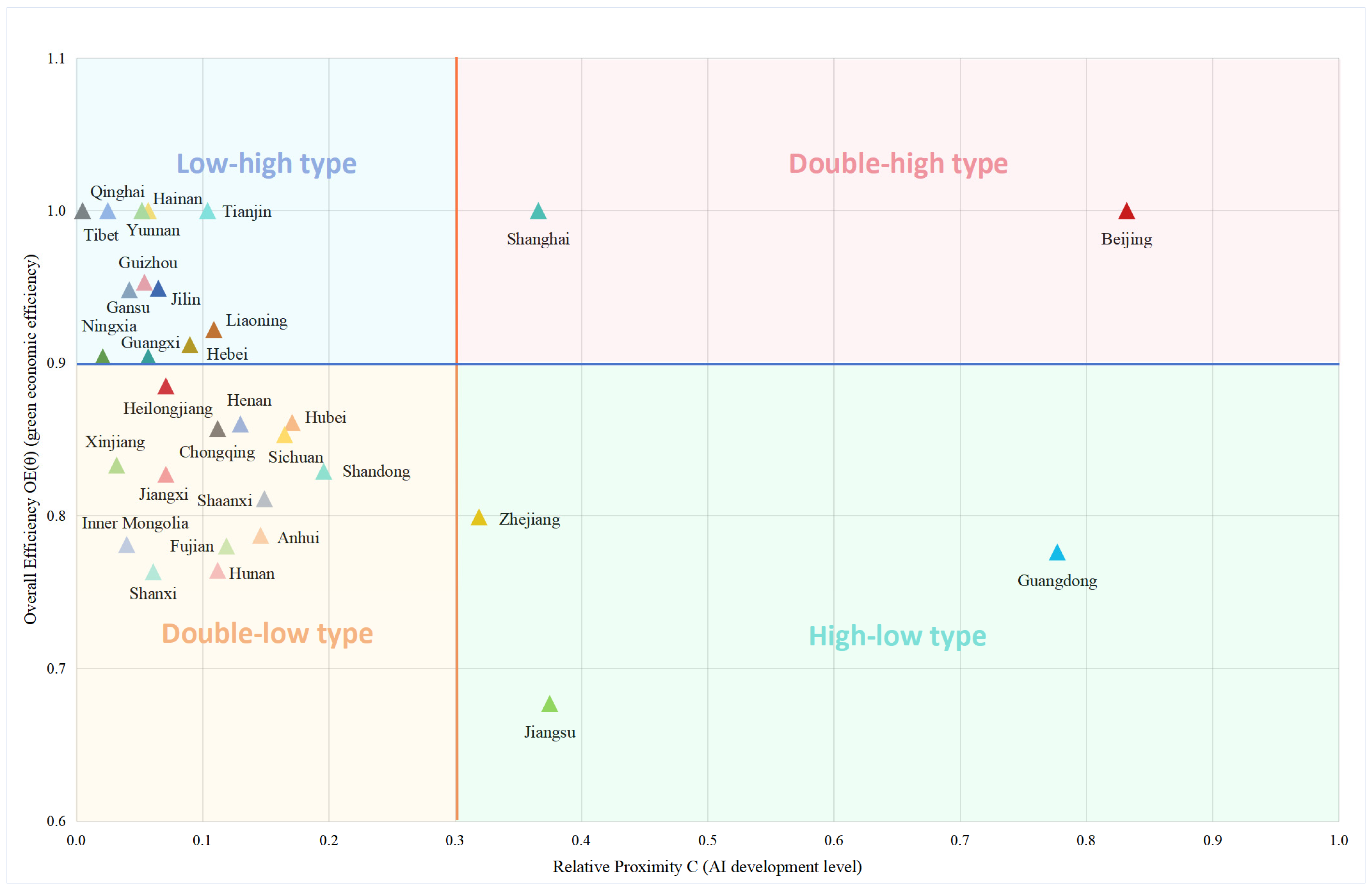

| Type | Driver | Bottleneck | Suggested Policy Lever |

|---|---|---|---|

| Double-High | Technological and policy leadership, strong resource spillover capacity. | Pressure to maintain innovation leadership; effectively radiating benefits to neighboring regions. | Act as growth poles to drive regional collaborative emissions reduction through technology transfer and institutional innovation. |

| High-Low | High concentration of technological resources, capital, and talent. | Low conversion rate of technology into green efficiency; potential diseconomies of scale from resource concentration. | Promote the application of technologies, optimize resource allocation, and facilitate the diffusion of outcomes to adjacent provinces. |

| Low-High | Superior ecological endowments and highly efficient resource utilization models. | Weak AI technical foundation, lacking technology and talent. | Enhance technology introduction and cooperation, optimize green industry models, and establish replicable “eco-plus” development pathways. |

| Double-Low | (Potential) Latecomer advantage and unique local resources. | Dual constraints of geography and industrial structure; comprehensive lack of factor inputs. | Prioritize the influx of talent, technology, and capital, learn from successful experiences, and build a localized green industrial system enabled by AI. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Li, Z.; Huang, Z.; Zhang, S. Regional Disparities in Artificial Intelligence Development and Green Economic Efficiency Performance Under Its Embedding: Empirical Evidence from China. Sustainability 2026, 18, 884. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18020884

Li Z, Huang Z, Zhang S. Regional Disparities in Artificial Intelligence Development and Green Economic Efficiency Performance Under Its Embedding: Empirical Evidence from China. Sustainability. 2026; 18(2):884. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18020884

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Ziyang, Ziqing Huang, and Shiyi Zhang. 2026. "Regional Disparities in Artificial Intelligence Development and Green Economic Efficiency Performance Under Its Embedding: Empirical Evidence from China" Sustainability 18, no. 2: 884. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18020884

APA StyleLi, Z., Huang, Z., & Zhang, S. (2026). Regional Disparities in Artificial Intelligence Development and Green Economic Efficiency Performance Under Its Embedding: Empirical Evidence from China. Sustainability, 18(2), 884. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18020884