Carbon Farming in Türkiye: Challenges, Opportunities and Implementation Mechanism

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Review and Synthesis of Carbon Farming Approaches, Mechanisms and Adoption Factors

2.1. Agricultural GHG Emissions and Carbon Farming in Türkiye

2.2. Carbon Farming as a Business Model

2.3. Carbon Farming Payment Models

- Action-Based Payments: In this model, farmers are compensated for adopting specific agricultural practices or technologies that are assumed to contribute to emission reduction. The Agri-Environment-Climate Payments (Pillar 2) under the European Union’s Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) are a prominent example. The main advantage of this mechanism stems from its low administrative and monitoring requirements, making it easier to implement. However, because payments are linked to actions rather than verified outcomes, the actual GHG reduction achieved may remain uncertain [17].

- Result-Based Payments: Result-based schemes reward farmers based on measurable and verified carbon sequestration outcomes. This approach is considered more performance-oriented and flexible, yet it depends heavily on complex and costly MRV systems. Additionally, the fluctuation of carbon prices can expose farmers to significant financial risk, particularly in volatile market conditions [32].

- Hybrid Payments: Hybrid models combine both action-based and result-based elements. Farmers receive upfront payments to cover initial implementation costs, while additional rewards are linked to verified emission reductions. This approach helps mitigate economic risk for farmers while ensuring measurable environmental benefits and stronger accountability [33,34].

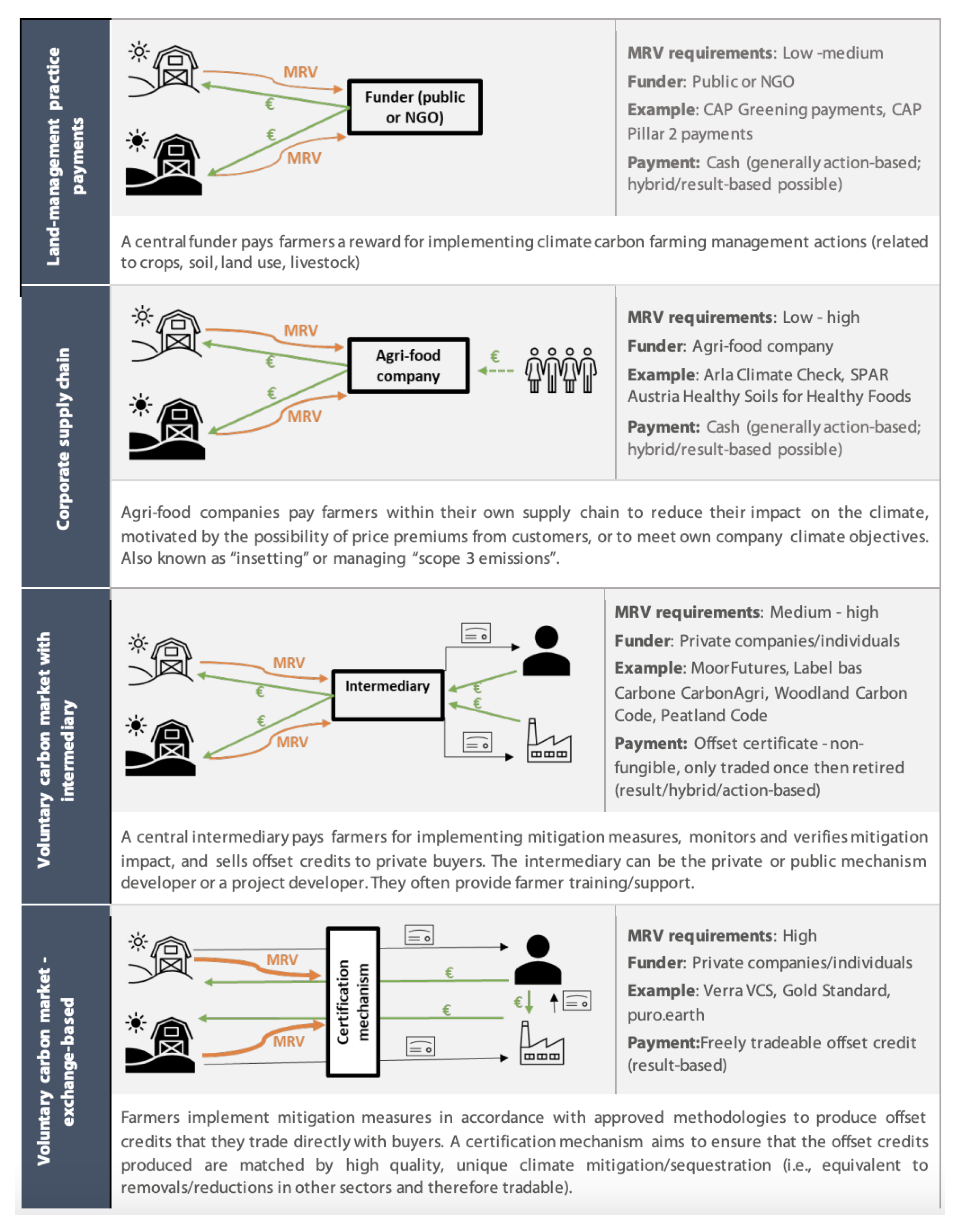

2.4. Carbon Farming Mechanisms and Models

- Land-Management Practice Payments: Publicly supported programs, such as the European Union’s CAP, incentivize farmers to adopt sustainable land management practices. This model offers low administrative costs and low financial risk, making it accessible for many farmers. However, as it generally follows an action-based payment structure, the actual GHG reduction outcomes may remain uncertain, and the system’s sustainability depends largely on public funding [17].

- Corporate Supply Chains: Private companies in the food and agriculture sectors increasingly integrate carbon farming into their supply chains. For example, Arla Foods conducts annual Climate Check audits covering over 200 parameters (e.g., feed, energy, manure management), calculates farm-level carbon emissions, and rewards farmers through its FarmAhead™ Sustainability Incentive program based on performance scores. This mechanism channels private sector finance into carbon farming but also poses risks such as limited transparency and high MRV costs [35,36].

- Voluntary Carbon Markets: Voluntary carbon markets allow farmers to implement specific carbon reduction or sequestration projects that generate tradable carbon credits. These markets have the potential to mobilize private sector investment in carbon farming, although participation is often limited by price volatility, high verification costs, and access barriers for small-scale farmers [37,38]. Voluntary carbon markets generally operate through two main structures: (i) intermediary-based models, where brokers or institutions connect farmers with buyers, and (ii) direct exchange-based systems, where farmers trade verified carbon credits directly with purchasers. Intermediary mechanisms may help reduce economic uncertainty by facilitating credit transactions, but can also increase management costs and limit transparency in project-level financial flows [39]. Direct exchange models, such as those certified by Verra VCS, Gold Standard, or puro.earth, typically require more rigorous MRV systems, yet provide greater traceability and potentially more flexible trading opportunities.

2.5. Soil-Based Practices

2.6. Land Use & Agroforestry

2.7. Livestock and Manure Management

- Direct reduction of enteric CH4 emissions through feed additives and improved feed efficiency;

- Reduction of N2O emissions via improved manure storage, treatment, and anaerobic digestion for biomethane production;

- Animal and feed management strategies aimed at enhancing productivity;

- Improvement of reproductive performance to increase efficiency and reduce emissions per unit of output.

2.8. Irrigation Related Practices: Carbon-Water Nexus

2.9. Barriers and Enablers of Carbon Farming Adoption

3. Policy and MRV Implications for Carbon Farming in Türkiye

3.1. Adaptability and Policy Context

- In the Mediterranean and Black Sea regions, agroforestry and biochar applications fit well with perennial crop systems and high biomass availability.

- In Central Anatolia and Marmara, conservation tillage and cover cropping are better suited due to widespread cereal cultivation and existing subsidy schemes.

- In Eastern Anatolia, rotational grazing holds the greatest potential for sustainable livestock management.

- Provide financial incentives, training and extension services for farmers;

- Integrate carbon farming into existing agricultural subsidy schemes;

- Establish transparent and reliable carbon credit certification systems.

3.2. Secondary Legislation (Drafts Under Development in Türkiye)

- Draft Regulation on Carbon Credit and Offsetting;

- Draft Regulation on the Turkish Emissions Trading System (ETS).

- Develop a practical policy guide to support the integration of carbon farming into legal and institutional structure.

- Prepare an implementation roadmap, outlining preparatory and operational steps.

- Establish a comprehensive MRV system to monitor carbon farming activities.

- Formulate a national strategy and long-term action plan for carbon farming implementation.

- Promote private-sector participation through public–private partnerships for carbon credit trading, financial instruments, and technology development.

- Facilitate integration of agricultural stakeholders into carbon markets and strengthen technical and investment capacities.

- Enhance institutional capacity and provide training for staff within relevant ministries and local agricultural agencies.

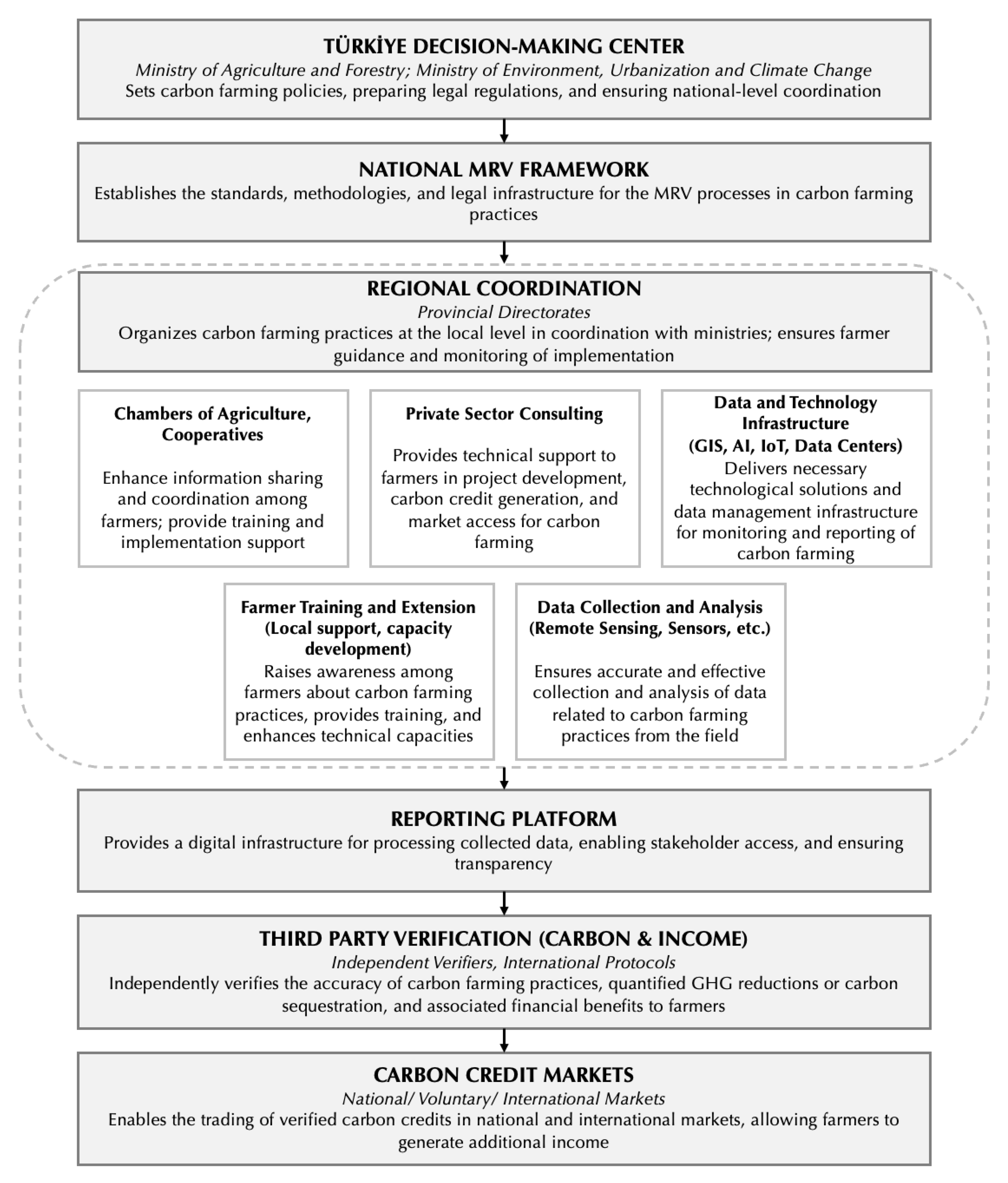

3.3. MRV Framework Proposal for Carbon Farming in Türkiye: Core Components and Implementation Pathway

- Measuring–Monitoring: The carbon storage and GHG mitigation potential of agricultural activities must be systematically measured. Key components include soil carbon, biomass, fertilizer use, and enteric fermentation. Continuous monitoring should be conducted through remote sensing, GIS sensors, and AI applications. To complement digital monitoring, farmer-based declaration systems should be supported by local verification mechanisms, ensuring the reliability of field-level data.

- Reporting: Data collected from the field must be reported regularly and in compliance with national and international standards. The national reporting framework should align with IPCC methodologies and international mechanisms such as the European Green Deal. Moreover, it should be integrated with Türkiye’s agricultural production planning and farmer registration systems to ensure coherence and data interoperability.

- Verification: All field-level measurements and reports must be verified by independent institutions to guarantee accuracy and transparency. Verification should be carried out by nationally and internationally accredited bodies, prioritizing traceability, data reliability, and transparency throughout the process.

- Regional Approach and Pilot Applications: Given Türkiye’s diverse climatic and soil conditions, customized MRV protocols must be developed for different agro-ecological regions. Pilot projects should initially be implemented in Aegean, Central Anatolia, and Southeastern Anatolia, representing distinct climatic zones. These pilots will serve as testing grounds for regional applicability, helping to refine methodologies and generate data for the eventual development of a national MRV system.

- Digital Infrastructure and Technology Integration: A strong digital infrastructure is important for the efficient operation of Türkiye’s MRV system. Utilizing AI-powered analytical tools, remote sensing, and data integration platforms will ensure accurate and timely measurement of carbon stock changes. Mobile applications and online reporting tools should facilitate farmer participation and improve transparency across all stages of the data management process.

- Institutional Cooperation and Capacity Building: Effective MRV implementation requires institutional coordination among the Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry, the Ministry of Environment, Urbanization and Climate Change, TurkStat, and academic institutions. Collaboration with NGOs, cooperatives, and farmer organizations will strengthen data accuracy and enhance field-level implementation. Training programs and extension services are necessary to increase farmers’ technical knowledge and active participation in MRV processes.

- Financial and Policy Incentives: Ensuring the sustainability of MRV systems demands strong financial support mechanisms. Programs such as Rural Development Investments Support Program, Instrument for Pre-Accession Assistance in Rural Development (IPARD), and new production-based incentive models should provide rewards for farmers adopting carbon farming practices. Integrating MRV outputs with carbon markets will enable farmers to generate additional income from verified emission reductions. The credibility of carbon credit trading requires rigorous monitoring and verification. Impact investment can also serve as a key financial driver. Such investments prioritize not only financial returns but also environmental and social benefits, making carbon farming and MRV systems particularly attractive for sustainable finance portfolios.

- Türkiye’s Carbon Farming MRV Mechanism: At present, Türkiye lacks a comprehensive national MRV infrastructure dedicated to carbon farming. This gap remains a key constraint to scaling up carbon farming and ensuring reliable data for carbon markets. Developing a standardized national MRV framework should therefore be a top priority. This framework must establish clear MRV protocols, supported by technology-based data collection and analysis tools. In addition, financial incentives and capacity-building programs should be developed to increase farmer participation. Addressing the high cost and complexity of current MRV procedures in voluntary markets [107] will require transparent governance and fair data management principles to build trust among farmers [89]. Considering Türkiye’s regional variability, flexible MRV approaches should be implemented progressively, starting with regional pilot projects and expanding toward a national system aligned with international standards [2].

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Climate Change 2021—The Physical Science Basis: Working Group I Contribution to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2021; p. 2391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Climate Change and Land: An IPCC Special Report on Climate Change, Desertification, Land Degradation, Sustainable Land Management, Food Security, and Greenhouse Gas Fluxes in Terrestrial Ecosystems; Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Kamyab, H.; SaberiKamarposhti, M.; Hashim, H.; Yusuf, M. Carbon dynamics in agricultural greenhouse gas emissions and removals: A comprehensive review. Carbon Lett. 2024, 34, 265–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). Paris Agreement. 2015. Available online: https://unfccc.int/process-and-meetings/the-paris-agreement (accessed on 7 December 2025).

- Lal, R. Soil organic matter and water retention. Agron. J. 2020, 112, 3265–3277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laban, P.; Metternicht, G.; Davies, J. Soil Biodiversity and Soil Organic Carbon: Keeping Drylands Alive; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, 2018; Volume 10. [Google Scholar]

- Karaş, E. Sustainable Soil and Water Management in Arid Climates in the Mediterranean Climate Zone; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Republic of Türkiye. GHG inventories, Mitigation. In National Inventory Report (NIR) 2022; National Inventory Report; Turkish Statistical Institute: Ankara, Türkiye, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Republic of Türkiye; Ministry of Environment, Urbanization and Climate Change. First Biennial Transparency Report of Türkiye. 2024. Available online: https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/resource/T%C3%BCrkiye_1BTR.pdf (accessed on 7 December 2025).

- Lal, R. Regenerative agriculture for food and climate. J. Soil Water Conserv. 2020, 75, 123A–124A. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Republic of Türkiye. GHG inventories. In National Inventory Document (NID) 2025; National Inventory Document; Turkish Statistical Institute: Ankara, Türkiye, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Lal, R. Soil carbon sequestration to mitigate climate change. Geoderma 2004, 123, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, P.; Soussana, J.F.; Angers, D.; Schipper, L.; Chenu, C.; Rasse, D.P.; Batjes, N.H.; Van Egmond, F.; McNeill, S.; Kuhnert, M.; et al. How to measure, report and verify soil carbon change to realize the potential of soil carbon sequestration for atmospheric greenhouse gas removal. Glob. Change Biol. 2020, 26, 219–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Queensland Government. Carbon Farming in Australia. Available online: https://www.qld.gov.au/environment/climate/climate-change/land-restoration-fund/carbon-farming/australia (accessed on 7 December 2025).

- European Commission. Carbon Removals and Carbon Farming; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- United States Department of Agriculture (USDA). Climate-Smart Agriculture: Soil Health & Carbon Farming; United States Department of Agriculture (USDA): Washington, DC, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- COWI; Ecologic Institute; IEEP. Technical Guidance Handbook—Setting up and Implementing Result-Based Carbon Farming Mechanisms in the EU; Report to the European Commission, DG Climate Action, Under Contract No. CLIMA/c.3/ETU/2018/007; COWI: Lyngby, Denmark, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Andrés, P.; Delgado, A.; Doblas-Miranda, E.; Berk, B. Carbon farming, crop yield and biodiversity in mediterranean europe: The dose makes the poison? Plant Soil 2025, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thierfelder, C.; Mhlanga, B. Short-term yield gains or long-term sustainability?—A synthesis of Conservation Agriculture long-term experiments in Southern Africa. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2022, 326, 107812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPCC. Agriculture, Forestry and Other Land Uses (AFOLU). In Climate Change 2022: Mitigation of Climate Change. Contribution of Working Group III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Chapter 7 (WGIII AR6); Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Soil Organic Carbon the Hidden Potential. FAO Soils Portal Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. 2017. Available online: https://www.fao.org/soils-portal/soil-management/soil-carbon-sequestration/en/ (accessed on 7 December 2025).

- Moukanni, N.; Brewer, K.M.; Gaudin, A.C.; O’Geen, A.T. Optimizing carbon sequestration through cover cropping in Mediterranean agroecosystems: Synthesis of mechanisms and implications for management. Front. Agron. 2022, 4, 844166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Büyük, G.; Akça, E.; Kume, T.; Nagano, T. Biomass effect on soil organic carbon in semi-arid continental conditions in central Turkey. Pol. J. Environ. Stud. 2020, 29, 3525–3533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cicek, H.; Kim, I.; Blanco-Moreno, J.M.; Urrutia Larrachea, I.; Cheikh M’hamed, H.; Gultekin, I.; Ouabbou, H.; El Abidine, A.Z.; Schoeber, M.; El Gharras, O.; et al. Strategic Tillage in the Mediterranean: No Universal Gains, Only Contextual Outcomes. Environments 2025, 12, 422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çomaklı, E.; Özgül, M.; Aydın, H. Assessment of Soil Carbon Stock in Different Land Use Types of Eastern Türkiye. SilvaWorld 2025, 4, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerber, P.; Hristov, A.; Henderson, B.; Makkar, H.; Oh, J.; Lee, C.; Meinen, R.; Montes, F.; Ott, T.; Firkins, J.; et al. Technical options for the mitigation of direct methane and nitrous oxide emissions from livestock: A review. Animal 2013, 7, 220–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Günal, H.; Kılıç, M.; Çelik, İ.; Budak, M. The Development and Opportunities of Carbon Markets in Turkey: Current Status and Future Outlook. In Proceedings of the ISPEC 17th International Conference on Agriculture, Animal Sciences and Rural Development, Kırşehir, Türkiye, 25–27 April 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Serengil, Y. Adopting carbon farming certification framework: Lessons from the EU’s initiative and potential for Türkiye. Turk. J. For. 2025, 26, 190–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbato, C.T.; Strong, A.L. Farmer perspectives on carbon markets incentivizing agricultural soil carbon sequestration. npj Clim. Action 2023, 2, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parmaksiz, O.; Cinar, G. Technology acceptance among farmers: Examples of agricultural unmanned aerial vehicles. Agronomy 2023, 13, 2077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandra, A. The water-carbon nexus: Is it worthwhile to generate carbon credits based on agricultural water management? Environ. Res. Lett. 2024, 19, 091004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartkowski, B.; Droste, N.; Ließ, M.; Sidemo-Holm, W.; Weller, U.; Brady, M.V. Implementing result-based agri-environmental payments by means of modelling. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1908.08219. [Google Scholar]

- Raina, N.; Zavalloni, M.; Viaggi, D. Incentive mechanisms of carbon farming contracts: A systematic mapping study. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 352, 120126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, H.; Frelih-Larsen, A.; Lóránt, A.; Duin, L.; Andersen, S.P.; Costa, G.; Bradley, H. Carbon Farming: Making Agriculture Fit for 2030; European Parliament: Strasbourg, France, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Arla Foods. FarmAhead™/Sustainability Incentive Model and Climate Check Program. 2023. Available online: https://www.arla.com/sustainability/the-farms/arlas-sustainability-incentive-model-qa/ (accessed on 7 December 2025).

- Institute for European Environmental Policy (IEEP). Arla Foods’ Sustainability Incentive Model. Available online: https://ieep.eu/ (accessed on 11 November 2025).

- Forest Trends’ Ecosystem Marketplace. State of the Voluntary Carbon Markets 2021: Installment 1: Market in Motion; Forest Trends Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Lema, R.; Bedoya Vargas, L.; Diaz-Gonzales, A.; Lachman, J.; Maes-Anastasi, A.; Kumar, P.; Wong, P.; Amar, S.; Cörvers, R.; Mensing, N. Smallholder Farmers and the Voluntary Carbon Market: A Balancing Act; Technical Report; Fair & Smart Data (FSD); Maastricht University: Maastricht, The Netherlands, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Carbon Market Watch. Analysis of Voluntary Carbon Market Stakeholders and Intermediaries; Carbon Market Watch: Brussels, Belgium, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, S.; Singh, A.B.; Mandal, A.; Thakur, J.K.; Sinha, N.K.; Das, A.; Elanchezhian, R.; Rajput, P.S.; Sharma, G.K. Response of nature-based and organic farming practices on soil chemical, biological properties and crop physiological attributes under soybean in vertisols of central India. Eurasian Soil Sci. 2024, 57, 1244–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.; Beegum, S.; Acharya, B.S.; Panday, D. Soil Carbon Sequestration: A Mechanistic Perspective on Limitations and Future Possibilities. Sustainability 2025, 17, 6015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acar, M.; Celik, I.; Günal, H. Effects of long-term tillage systems on aggregate-associated organic carbon in the eastern Mediterranean region of Turkey. Eurasian J. Soil Sci. 2018, 7, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woolf, D.; Amonette, J.E.; Street-Perrott, F.A.; Lehmann, J.; Joseph, S. Sustainable biochar to mitigate global climate change. Nat. Commun. 2010, 1, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koprivica, M.; Petrović, J.; Simić, M.; Dimitrijević, J.; Ercegović, M.; Trifunović, S. Characterization and Evaluation of Biomass Waste Biochar for Turfgrass Growing Medium Enhancement in a Pot Experiment. Agriculture 2025, 15, 2206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Li, W.; Xue, N.; Xi, R.; Wang, Y.; Fang, L.; Wang, Q.; Liang, X.; Xiao, Y.; Yang, X.; et al. Co-application of biochar and compost enhanced soil carbon sequestration in urban green space. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1707894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kausar, T.; Sun, F.; Li, Y.; Gong, J.; Zhou, S.; Rafiq, M.K.; Tariq, A.; Xiu, Y.; Li, L.; Tie, L.; et al. Biochar as a Nature-Based Solution for Sustainable and Drought-Resilient Grassland Restoration. Land Degrad. Dev. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conant, R.T.; Cerri, C.E.; Osborne, B.B.; Paustian, K. Grassland management impacts on soil carbon stocks: A new synthesis. Ecol. Appl. 2017, 27, 662–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paustian, K.; Lehmann, J.; Ogle, S.; Reay, D.; Robertson, G.P.; Smith, P. Climate-smart soils. Nature 2016, 532, 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramachandran Nair, P.; Mohan Kumar, B.; Nair, V.D. Agroforestry as a strategy for carbon sequestration. J. Plant Nutr. Soil Sci. 2009, 172, 10–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassie, G.W. Agroforestry and farm income diversification: Synergy or trade-off? The case of Ethiopia. Environ. Syst. Res. 2017, 6, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerda, R.; Deheuvels, O.; Calvache, D.; Niehaus, L.; Saenz, Y.; Kent, J.; Vilchez, S.; Villota, A.; Martínez, C.; Somarriba, E. Contribution of cocoa agroforestry systems to family income and domestic consumption: Looking toward intensification. Agrofor. Syst. 2014, 88, 957–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suratman, M.N.; Brandle, J.R. Tree shelterbelts for sustainable agroforestry. In Agroforestry for Carbon and Ecosystem Management; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2024; pp. 97–107. [Google Scholar]

- Udawatta, R.P.; Rankoth, L.M.; Jose, S. Agroforestry and biodiversity. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbow, C.; Van Noordwijk, M.; Luedeling, E.; Neufeldt, H.; Minang, P.A.; Kowero, G. Agroforestry solutions to address food security and climate change challenges in Africa. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2014, 6, 61–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griscom, B.W.; Adams, J.; Ellis, P.W.; Houghton, R.A.; Lomax, G.; Miteva, D.A.; Schlesinger, W.H.; Shoch, D.; Siikamäki, J.V.; Smith, P.; et al. Natural climate solutions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, 11645–11650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Göl, C.; Mevruk, S. Assessing amount of soil organic carbon and some soil properties under different land uses in a semi-arid region of northern Türkiye. Turk. J. For. 2022, 23, 268–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hristov, A.N.; Oh, J.; Lee, C.; Meinen, R.; Montes, F.; Ott, T.; Firkins, J.; Rotz, A.; Dell, C.; Adesogan, A.; et al. Mitigation of Greenhouse Gas Emissions in Livestock Production: A Review of Technical Options for Non-CO2 Emissions; Number 177 in FAO Animal Production and Health Paper; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO): Rome, Italy, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Dağlıoğlu, S.T.; Taşkın, R.; Özteke, N.İ.; Kandemir, Ç.; Taşkın, T. Reducing Strategies for Carbon Footprint of Livestock in Izmir/Turkiye. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2024, 235, 243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papakonstantinou, G.I.; Voulgarakis, N.; Terzidou, G.; Fotos, L.; Giamouri, E.; Papatsiros, V.G. Precision livestock farming technology: Applications and challenges of animal welfare and climate change. Agriculture 2024, 14, 620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berckmans, D. General introduction to precision livestock farming. Anim. Front. 2017, 7, 6–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossi, G.; Goglio, P.; Vitali, A.; Williams, A.G. Livestock and climate change: Impact of livestock on climate and mitigation strategies. Anim. Front. 2019, 9, 69–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosa, L. Adapting agriculture to climate change via sustainable irrigation: Biophysical potentials and feedbacks. Environ. Res. Lett. 2022, 17, 063008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gleick, P.H.; Cooley, H.; Cohen, M.J.; Marikawa, M.; Morrison, J.; Palaniappan, M. The World’s Water 2008–2009: The Biennial Report on Freshwater Resources; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2009; Volume 6. [Google Scholar]

- Qin, J.; Duan, W.; Zou, S.; Chen, Y.; Huang, W.; Rosa, L. Global energy use and carbon emissions from irrigated agriculture. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 3084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demir, M.S.; Muratoglu, A.; Kartal, V.; Nas, H. Temporal analysis of agricultural water footprint dynamics in Türkiye: Climate change impacts and adaptation. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 390, 126310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şeren, A.; Yildirim, M.U. Activities on the Efficient Use of Water in Agriculture in Türkiye Under Climate Change. In Agriculture and Water Management Under Climate Change; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; p. 117. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, K.; Zhong, X.; Huang, N.; Lampayan, R.M.; Liu, Y.; Pan, J.; Peng, B.; Hu, X.; Fu, Y. Nitrogen losses and greenhouse gas emissions under different N and water management in a subtropical double-season rice cropping system. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 609, 46–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; Wang, J.; Li, Z.; Wang, S.; Qu, Y. Effects of irrigation regime and nitrogen fertilizer management on CH4, N2O and CO2 emissions from saline–alkaline paddy fields in Northeast China. Sustainability 2018, 10, 475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sapkota, A.; Haghverdi, A.; Avila, C.C.; Ying, S.C. Irrigation and greenhouse gas emissions: A review of field-based studies. Soil Syst. 2020, 4, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gultekin, R.; Kadri, A.; Görgişen, C.; Öztürk, Ö.; Yeter, T.; Alsan, P.B. Effect of deficit irrigation practices on greenhouse gas emissions in drip irrigation. Sci. Hortic. 2023, 310, 111757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, X.; Zhang, Z.; Yuan, F.; Song, C. The impact of global cropland irrigation on soil carbon dynamics. Agric. Water Manag. 2024, 296, 108806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jägermeyr, J.; Gerten, D.; Heinke, J.; Schaphoff, S.; Kummu, M.; Lucht, W. Water savings potentials of irrigation systems: Global simulation of processes and linkages. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2015, 19, 3073–3091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sha, Z.; Bai, Y.; Li, R.; Lan, H.; Zhang, X.; Li, J.; Liu, X.; Chang, S.; Xie, Y. The global carbon sink potential of terrestrial vegetation can be increased substantially by optimal land management. Commun. Earth Environ. 2022, 3, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudson, B.D. Soil organic matter and available water capacity. J. Soil Water Conserv. 1994, 49, 189–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, G.; Smith, P.; Pan, W. The role of soil organic matter in maintaining the productivity and yield stability of cereals in China. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2009, 129, 344–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, H.; Lu, C.; Ciais, P.; Michalak, A.M.; Canadell, J.G.; Saikawa, E.; Huntzinger, D.N.; Gurney, K.R.; Sitch, S.; Zhang, B.; et al. The terrestrial biosphere as a net source of greenhouse gases to the atmosphere. Nature 2016, 531, 225–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hao, Y.; Mao, J.; Bachmann, C.M.; Hoffman, F.M.; Koren, G.; Chen, H.; Tian, H.; Liu, J.; Tao, J.; Tang, J.; et al. Soil moisture controls over carbon sequestration and greenhouse gas emissions: A review. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 2025, 8, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emde, D.; Hannam, K.D.; Most, I.; Nelson, L.M.; Jones, M.D. Soil organic carbon in irrigated agricultural systems: A meta-analysis. Glob. Change Biol. 2021, 27, 3898–3910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buck, H.J.; Palumbo-Compton, A. Soil carbon sequestration as a climate strategy: What do farmers think? Biogeochemistry 2022, 161, 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumbrell, N.P.; Kragt, M.E.; Gibson, F.L. What carbon farming activities are farmers likely to adopt? A best–worst scaling survey. Land Use Policy 2016, 54, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payen, F.T.; Moran, D.; Cahurel, J.Y.; Aitkenhead, M.; Alexander, P.; MacLeod, M. Why do French winegrowers adopt soil organic carbon sequestration practices? Understanding motivations and barriers. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2023, 6, 994364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kragt, M.E.; Dumbrell, N.P.; Blackmore, L. Motivations and barriers for Western Australian broad-acre farmers to adopt carbon farming. Environ. Sci. Policy 2017, 73, 115–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, S.K.; Stein, T.V.; Nair, P.R.; Andreu, M.G. The socioeconomic context of carbon sequestration in agroforestry: A case study from homegardens of Kerala, India. In Carbon Sequestration Potential of Agroforestry Systems: Opportunities and Challenges; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2011; pp. 281–298. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, T.; Bruins, R.J.; Heberling, M.T. Factors influencing farmers’ adoption of best management practices: A review and synthesis. Sustainability 2018, 10, 432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cakirli Akyüz, N.; Theuvsen, L. The impact of behavioral drivers on adoption of sustainable agricultural practices: The case of organic farming in Turkey. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guldal, H.T.; Sanli, H.; Turker, M. The path to smart farming: Profiling farmers’ adoption of technologies in Türkiye. Agric. Econ. 2025, 71, 229–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Günay, T.; Altınok, Ö.C.N. Drivers of Capia Pepper Farmers’ Intentions and Behaviors on Pesticide Use in Turkey: A Structural Equation Model. J. Agric. Sci. 2024, 30, 243–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganiyusufoğlu, A.; Bayramoğlu, Z.; Mirza, E.; Doğan, H.G.; Edirneligil, A.; Candemir, S. From Intentions to Sustainable Actions: Behavioral Drivers of Climate Change Mitigation and Adaptation in Agriculture. Sustain. Dev. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wreford, A.; Ignaciuk, A.; Gruère, G. Overcoming Barriers to the Adoption of Climate-Friendly Practices in Agriculture; Technical Report 101; Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development (OECD): Paris, France, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, P.; Hazra, K.; Mandal, B. Prospects of Carbon Farming and its Role in Food and Environmental Security. Indian J. Fertil. 2024, 20, 728–740. [Google Scholar]

- Ullah, K.M.; Oladosu, G.A.; Crooks, A. Evaluating the incentive for soil organic carbon sequestration from carinata production in the Southeast United States. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 348, 119418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karanja Ng’ang’a, S.; Jalang’o, D.A.; Girvetz, E.H. Adoption of technologies that enhance soil carbon sequestration in East Africa. What influence farmers’ decision? Int. Soil Water Conserv. Res. 2020, 8, 90–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueredo, A. A review of research on farmers’ perspectives and attitudes towards carbon farming as a climate change mitigation strategy. In Urban and Rural Reports; Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences: Uppsala, Sweden, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Van Hoof, S. Climate change mitigation in agriculture: Barriers to the adoption of carbon farming policies in the EU. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kathage, J.; Smit, B.; Janssens, B.; Haagsma, W.; Adrados, J.L. How much is policy driving the adoption of cover crops? Evidence from four EU regions. Land Use Policy 2022, 116, 106016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutherland, L.A.; Marchand, F. On-farm demonstration: Enabling peer-to-peer learning. J. Agric. Educ. Ext. 2021, 27, 573–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry (MoAF). Strategic Plan 2024–2028; Technical Report; Republic of Türkiye, Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry: Ankara, Türkiye, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Marakoğlu, T.; Özbek, O.; Çarman, K. Nohut üretiminde farklı toprak işleme sistemlerinin enerji bilançosu. Tarım Makinaları Bilim. Derg. 2010, 6, 229–235. [Google Scholar]

- Ulanov, V.L. The Need for the Green Economy Factors in Assessing the Development and Growth of Russian Raw Materials Companies. J. Compr. Bus. Adm. Res. 2024, 1, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Republic of Türkiye. Climate Law (Law No. 7552), Official Gazette of the Republic of Türkiye: Ankara, Türkiye, 2025.

- Republic of Türkiye; Ministry of Environment, Urbanization and Climate Change (MoEUCC). Draft TR ETS Regulation Published for Consultation; Ministry of Environment, Urbanization and Climate Change: Ankara, Türkiye, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- International Carbon Action Partnership (ICAP). Turkish Emission Trading System (TR ETS); International Carbon Action Partnership: Berlin, Germany, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Brummitt, C.D.; Mathers, C.A.; Keating, R.A.; O’Leary, K.; Easter, M.; Friedl, M.A.; DuBuisson, M.; Campbell, E.E.; Pape, R.; Peters, S.J.; et al. Solutions and insights for agricultural monitoring, reporting, and verification (MRV) from three consecutive issuances of soil carbon credits. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 369, 122284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perosa, B.; Newton, P.; da Silva, R.F.B. A monitoring, reporting and verification system for low carbon agriculture: A case study from Brazil. Environ. Sci. Policy 2023, 140, 286–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruysschaert, G.; Xu, H.; D’Hose, T. Monitoring, Reporting and Verification (MRV) for carbon farming. In Proceedings of the Belgian Science for Climate Action Conference 2024—Causes and Consequences of Climate Extremes, Brussels, Belgium, 19–20 February 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, C.; Kovacs, J.M. The application of small unmanned aerial systems for precision agriculture: A review. Precis. Agric. 2012, 13, 693–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, L.; La Hoz Theuer, S. Environmental integrity of international carbon market mechanisms under the Paris Agreement. Clim. Policy 2019, 19, 386–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Aydın, A.; Köroğlu, F.; Thomas, E.A.; Salvinelli, C.; Polat, E.P.; Yıldırak, K. Carbon Farming in Türkiye: Challenges, Opportunities and Implementation Mechanism. Sustainability 2026, 18, 891. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18020891

Aydın A, Köroğlu F, Thomas EA, Salvinelli C, Polat EP, Yıldırak K. Carbon Farming in Türkiye: Challenges, Opportunities and Implementation Mechanism. Sustainability. 2026; 18(2):891. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18020891

Chicago/Turabian StyleAydın, Abdüssamet, Fatma Köroğlu, Evan Alexander Thomas, Carlo Salvinelli, Elif Pınar Polat, and Kasırga Yıldırak. 2026. "Carbon Farming in Türkiye: Challenges, Opportunities and Implementation Mechanism" Sustainability 18, no. 2: 891. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18020891

APA StyleAydın, A., Köroğlu, F., Thomas, E. A., Salvinelli, C., Polat, E. P., & Yıldırak, K. (2026). Carbon Farming in Türkiye: Challenges, Opportunities and Implementation Mechanism. Sustainability, 18(2), 891. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18020891