The Mediterranean Paradox: Knowledge, Attitudes, and the Barriers to Practical Adherence of Sustainable Dietary Behavior Among Future Educators—A Case Study of Teacher Education Students at the University of Split

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Research Methodology

Research Instrument

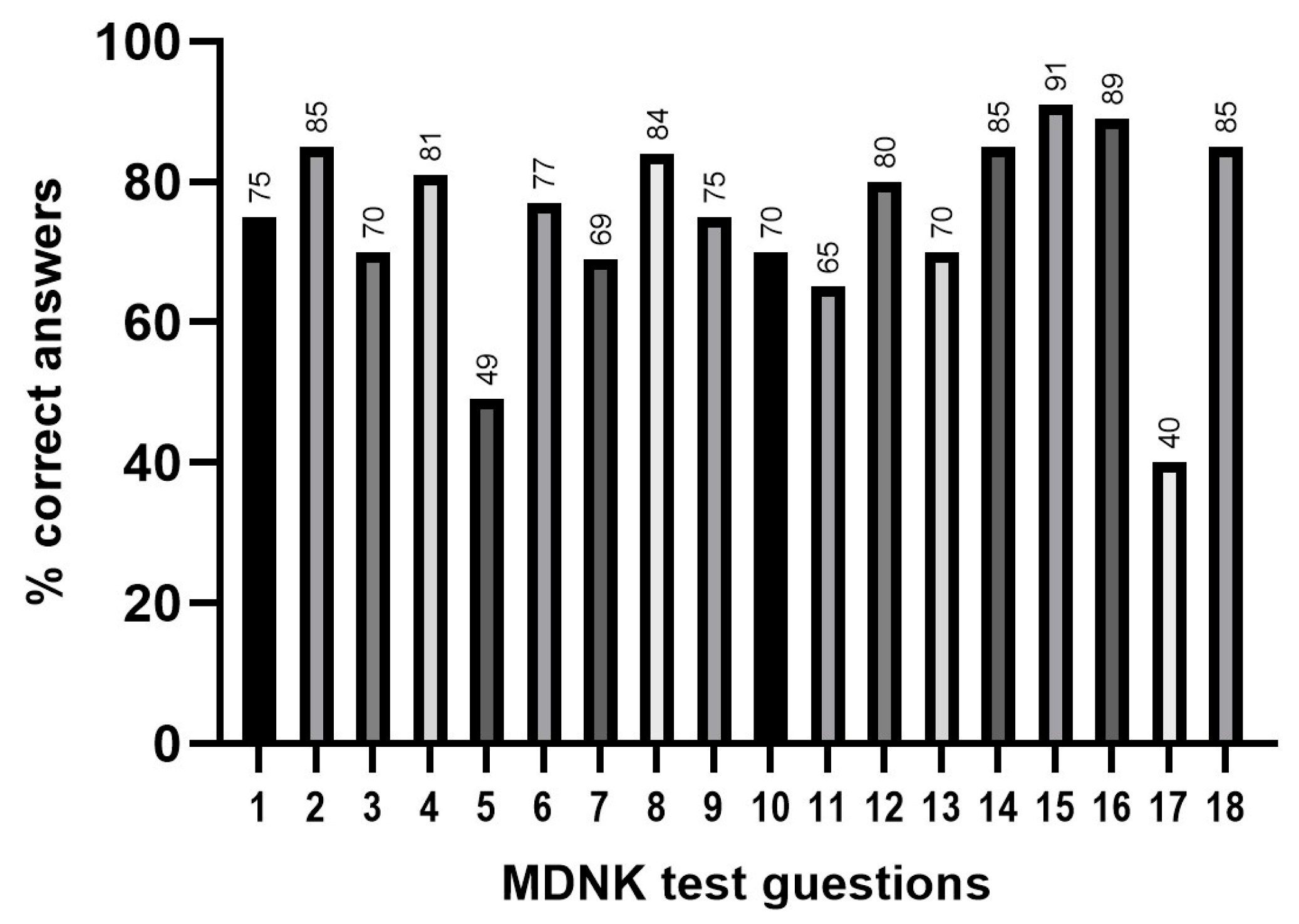

- Knowledge of the Mediterranean Diet (MDNK Test): This sub-section consisted of 18 questions designed to assess students’ knowledge of the Mediterranean Diet. The questions covered topics such as the standard and healthy types of fats, the most used oils, the recommended frequency of fish consumption, and the basic food groups at the base of the Mediterranean pyramid. Representative items included identifying olive oil as the primary source of fat and determining the correct frequency of fish consumption (e.g., ‘How many times per week is fish consumption recommended in the Mediterranean diet?’). Additionally, participants were asked to recognize which foods should be consumed at every main meal to evaluate their understanding of the pyramid’s foundation. The total knowledge score was calculated as the sum of correct responses, ranging from 0 to 18. Responses were marked as either true or false, with each correct answer receiving one point [28].

- Attitudes towards the Mediterranean Diet: This sub-section assessed students’ attitudes regarding the benefits and usefulness of the Mediterranean Diet. The statements were designed based on a review of relevant scientific literature on the Mediterranean dietary pattern, its health effects, sustainability, and its potential for application in everyday life. The students’ level of agreement with 10 statements was measured using a 5-point Likert scale, where 1 = strongly disagree, 2 = disagree, 3 = neutral, 4 = agree, and 5 = strongly agree.

- Self-Reported Dietary Habits (MEDAS Test): This sub-section included 14 questions focused on the self-assessment of students’ dietary habits. The MEDAS questionnaire comprises 14 closed-ended questions with predefined criteria for awarding 1 point per affirmative response. The maximum score a participant could achieve was 14, with a higher score indicating a higher level of adherence to the Mediterranean Diet. Scoring criteria were based on the frequency of consuming specific food groups (e.g., olive oil, vegetables, fruits, fish, legumes, nuts). For instance, participants were awarded 1 point if they consumed at least 4 tablespoons of olive oil per day; ≥2 servings of vegetables and ≥3 servings of fruit per day, but also for the restriction of unhealthy food categories (e.g., less than 1 serving of butter, margarine, or cream per day; for consuming < 1 serving of processed meat per day or <1 sugar-sweetened beverage daily). MEDAS scores were subsequently categorized into three distinct levels: low adherence (0–5 points), moderate adherence (6–9 points), and high adherence (10 points or more) [29,30].

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Sample Structure

3.2. Students’ Knowledge About the Mediterranean Diet

Differences in Knowledge of Junior and Senior Students About the Basic Principles of the Mediterranean Diet

3.3. Students’ Attitudes on the Benefits and Usefulness of the Mediterranean Diet

Comparison of Junior and Senior Students’ Attitudes on the Benefits and Usefulness of the Mediterranean Diet

3.4. Students’ Self-Assessment of Dietary Habits (MEDAS Test)

3.4.1. Comparison of Self-Assessment of Dietary Habits (MEDAS Test) in Junior and Senior Students

3.4.2. Comparison of Adherence to the Mediterranean Diet (MEDAS) According to the Employment Status of Students

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Whitmee, S.; Haines, A.; Beyrer, C.; Boltz, F.; Capon, A.G.; de Souza Dias, B.F.; Ezeh, A.; Frumkin, H.; Gong, P.; Head, P.; et al. Safeguarding human health in the Anthropocene epoch: Report of The Rockefeller Foundation-Lancet Commission on planetary health. Lancet 2015, 386, 1973–2028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirzabaev, A.; Olsson, L.; Kerr, R.B.; Pradhan, P.; Ferre, M.G.R.; Lotze-Campen, H. Climate Change and Food Systems. In Science and Innovations for Food Systems Transformation; von Braun, J.A.K., Fresco, L.O., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkins, J. Nutrition Education in the Anthropocene: Toward Public and Planetary Health. J. Agric. Food Syst. Community Dev. 2020, 9, 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willett, W.; Rockström, J.; Loken, B.; Springmann, M.; Lang, T.; Vermeulen, S.; Garnett, T.; Tilman, D.; DeClerck, F.; Wood, A.; et al. Food in the Anthropocene: The EAT–Lancet Commission on healthy diets from sustainable food systems. Lancet 2019, 393, 447–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; He, P.; Shan, Y.; Li, Y.; Hang, Y.; Shao, S.; Ruzzenenti, F.; Hubacek, K. Reducing climate change impacts from the global food system through diet shifts. Nat. Clim. Change 2024, 14, 943–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Global Health Observatory (GHO) Data: Overweight and Obesity; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Kanellopoulou, A.; Giannakopoulou, S.P.; Notara, V.; Antonogeorgos, G.; Rojas-Gil, A.P.; Kornilaki, E.N.; Konstantinou, E.; Lagiou, A.; Panagiotakos, D.B. The association between adherence to the Mediterranean diet and childhood obesity; the role of family structure: Results from an epidemiological study in 1728 Greek students. J. Nutr. Health 2021, 27, 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sofi, F.; Cesari, F.; Abbate, R.; Gensini, G.F.; Casini, A. Adherence to Mediterranean diet and health status: Meta-analysis. BMJ 2008, 337, a1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Alessandro, A.; De Pergola, G. The Mediterranean Diet: Its definition and evaluation of a priori dietary indexes in primary cardiovascular prevention. Int. J. Food. Sci. Nutr. 2018, 69, 647–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrone, P.; D’Angelo, S. Gut Microbiota Modulation Through Mediterranean Diet Foods: Implications for Human Health. Nutrients 2025, 17, 948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiani, A.K.; Medori, M.C.; Bonetti, G.; Aquilanti, B.; Velluti, V.; Matera, G.; Iaconelli, A.; Stuppia, L.; Connelly, S.T.; Herbst, K.L.; et al. Modern vision of the Mediterranean diet. J. Prev. Med. Hyg. 2022, 63, e36–e43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roglic, G. WHO Global report on diabetes: A summary. Int. J. Noncommunicable Dis. 2016, 1, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capel, S.L.R.; Allan, B.F.; Favela, A.; Clem, C.S.; Ooi, S.K.; Virrueta Herrera, S.; Wilson, L.J.; Strickland, L.R. Education in the Anthropocene: Assessing planetary health science standards in the USA. Proc. Biol. Sci. 2023, 290, 20230975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN. Resolution Adopted by the General Assembly on 25 September 2015; General Assembly Resolution 70/1; UN: New York, NY, USA, 2015; p. 35. [Google Scholar]

- Bonaccio, M.; Iacoviello, L.; Donati, M.B.; de Gaetano, G. The tenth anniversary as a UNESCO world cultural heritage: An unmissable opportunity to get back to the cultural roots of the Mediterranean diet. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2022, 76, 179–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrone, P.; Landriani, L.; Patalano, R.; Meccariello, R.; D’Angelo, S. The Mediterranean Diet as a Model of Sustainability: Evidence-Based Insights into Health, Environment, and Culture. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 1658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dernini, S.; Berry, E.M.; Serra-Majem, L.; La Vecchia, C.; Capone, R.; Medina, F.X.; Aranceta-Bartrina, J.; Belahsen, R.; Burlingame, B.; Calabrese, G.; et al. Med Diet 4.0: The Mediterranean diet with four sustainable benefits. Public Health Nutr. 2017, 20, 1322–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macdiarmid, J.I. Is a healthy diet an environmentally sustainable diet? Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2013, 72, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilman, D.; Clark, M. Global diets link environmental sustainability and human health. Nature 2014, 515, 518–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bucciarelli, V.; Moscucci, F.; Cocchi, C.; Nodari, S.; Sciomer, S.; Gallina, S.; Mattioli, A.V. Climate change versus Mediterranean diet: A hazardous struggle for the women’s heart. Am. Heart J. Plus 2024, 45, 100431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tepper, S.; Kissinger, M.; Avital, K.; Shahar, D.R. The Environmental Footprint Associated With the Mediterranean Diet, EAT-Lancet Diet, and the Sustainable Healthy Diet Index: A Population-Based Study. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 870883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godos, J.; Scazzina, F.; Paternò Castello, C.; Giampieri, F.; Quiles, J.L.; Briones Urbano, M.; Battino, M.; Galvano, F.; Iacoviello, L.; de Gaetano, G.; et al. Underrated aspects of a true Mediterranean diet: Understanding traditional features for worldwide application of a “Planeterranean” diet. J. Transl. Med. 2024, 22, 294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, P.; Araújo, R.; Lopes, F.; Ray, S. Nutrition and Food Literacy: Framing the Challenges to Health Communication. Nutrients 2023, 15, 4708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Micheloni, G.; Cocchi, C.; Sinigaglia, G.; Coppi, F.; Zanini, G.; Moscucci, F.; Sciomer, S.; Nasi, M.; Desideri, G.; Gallina, S.; et al. Sustainability of the Mediterranean Diet: A Nutritional and Environmental Imperative. J. Sustain. Res. 2025, 7, e250036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Gil, J.F.; Victoria-Montesinos, D.; García-Hermoso, A. Is higher adherence to the mediterranean diet associated with greater academic performance in children and adolescents? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Nutr. 2024, 43, 1702–1709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brulotte, R.L.; Di Giovine, M.A. (Eds.) Edible Identities: Food as Cultural Heritage; Routledge: London, UK, 2014; p. 252. [Google Scholar]

- Baldassano, S.; Alioto, A.; Amato, A.; Rossi, C.; Messina, G.; Bruno, M.R.; Stallone, R.; Proia, P. Fighting the Consequences of the COVID-19 Pandemic: Mindfulness, Exercise, and Nutrition Practices to Reduce Eating Disorders and Promote Sustainability. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bottcher, M.R.; Marincic, P.Z.; Nahay, K.L.; Baerlocher, B.E.; Willis, A.W.; Park, J.; Gaillard, P.; Greene, M.W. Nutrition knowledge and Mediterranean diet adherence in the southeast United States: Validation of a field-based survey instrument. Appetite 2017, 111, 166–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Conesa, M.-T.; Philippou, E.; Pafilas, C.; Massaro, M.; Quarta, S.; Andrade, V.; Jorge, R.; Chervenkov, M.; Ivanova, T.; Dimitrova, D.; et al. Exploring the Validity of the 14-Item Mediterranean Diet Adherence Screener (MEDAS): A Cross-National Study in Seven European Countries around the Mediterranean Region. Nutrients 2020, 12, 2960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-González, M.A.; García-Arellano, A.; Toledo, E.; Salas-Salvadó, J.; Buil-Cosiales, P.; Corella, D.; Covas, M.I.; Schröder, H.; Arós, F.; Gómez-Gracia, E.; et al. A 14-Item Mediterranean Diet Assessment Tool and Obesity Indexes among High-Risk Subjects: The PREDIMED Trial. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, 43134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franchini, C.; Biasini, B.; Sogari, G.; Wongprawmas, R.; Andreani, G.; Dolgopolova, I.; Gómez, M.I.; Roosen, J.; Menozzi, D.; Mora, C.; et al. Adherence to the Mediterranean Diet and its association with sustainable dietary behaviors, sociodemographic factors, and lifestyle: A cross-sectional study in US University students. Nutr. J. 2024, 23, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karam, J.; Bibiloni, M.D.M.; Serhan, M.; Tur, J.A. Adherence to Mediterranean Diet among Lebanese University Students. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomás-Gallego, G.; Dalmau-Torres, J.M.; Jiménez-Boraita, R.; Ortuño-Sierra, J.; Gargallo-Ibort, E. Adherence to the Mediterranean Diet in Spanish University Students: Association with Lifestyle Habits, Mental and Emotional Well-Being. Nutrients 2025, 17, 698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonopoulou, M.; Mantzorou, M.; Serdari, A.; Bonotis, K.; Vasios, G.; Pavlidou, E.; Trifonos, C.; Vadikolias, K.; Petridis, D.; Giaginis, C. Evaluating Mediterranean diet adherence in university student populations: Does this dietary pattern affect students’ academic performance and mental health? Int. J. Health Plann. Manag. 2020, 35, 5–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO/EURO:2021-4007-43766-61591; Plant-Based Diets and Their Impact on Health, Sustainability and the Environment: A Review of the Evidence: WHO European Office for the Prevention and Control of Noncommunicable Diseases. World Health Organization, Regional Office for Europe Copenhagen: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2021; p. 11.

- Bôto, J.M.; Rocha, A.; Miguéis, V.; Meireles, M.; Neto, B. Sustainability Dimensions of the Mediterranean Diet: A Systematic Review of the Indicators Used and Its Results. Adv. Nutr. 2022, 13, 2015–2038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vallverdú-Queralt, A.; de Alvarenga, J.F.; Estruch, R.; Lamuela-Raventos, R.M. Bioactive compounds present in the Mediterranean sofrito. Food Chem. 2013, 141, 3365–3372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfaro-González, S.; Garrido-Miguel, M.; Fernández-Rodríguez, R.; Mesas, A.E.; Bravo-Esteban, E.; López-Muñoz, P.; Rodríguez-Gutiérrez, E.; Martínez-Vizcaíno, V. Higher adherence to the Mediterranean Diet is associated with better academic achievement in Spanish university students: A multicenter cross-sectional study. Nutr. Res. 2024, 126, 193–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yurtdaş Depboylu, G.; Şimşek, B. The interplay between sleep quality, hedonic hunger, and adherence to the Mediterranean diet among early adolescents. Appetite 2025, 206, 107845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dakanalis, A.; Papadimitriou, K.; Alexatou, O.; Deligiannidou, G.E.; Pappa, M.; Papadopoulou, S.K.; Louka, A.; Paschodimas, G.; Mentzelou, M.; Giaginis, C. Mediterranean Diet Compliance Is Related with Lower Prevalence of Perceived Stress and Poor Sleep Quality in University Students: A Cross-Sectional Study in Greece. Nutrients 2025, 17, 2174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Leary, M.; Mooney, E.; McCloat, A. The Relationship Between Nutrition Knowledge and Dietary Intake of University Students: A Scoping Review. Dietetics 2025, 4, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saulle, R.; Del Prete, G.; Stelmach-Mardas, M.; De Giusti, M.; La Torre, G. A breaking down of the Mediterranean diet in the land where it was discovered. A cross sectional survey among the young generation of adolescents in the heart of Cilento, Southern Italy. Ann. Ig. 2016, 28, 349–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ünal, G.; Özenoğlu, A. Association of Mediterranean diet with sleep quality, depression, anxiety, stress, and body mass index in university students: A cross-sectional study. Nutr. Health 2025, 31, 659–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theodoridis, X.; Grammatikopoulou, M.G.; Gkiouras, K.; Papadopoulou, S.E.; Agorastou, T.; Gkika, I.; Maraki, M.I.; Dardavessis, T.; Chourdakis, M. Food insecurity and Mediterranean diet adherence among Greek university students. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2018, 28, 477–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petroka, K.; Dinu, M.; Hoover, C.; Casini, A.; Sofi, F. Short-term Exposure to a Mediterranean Environment Influences Attitudes and Dietary Profile in U.S. College Students: The MEDiterranean Diet in AMEricans (A-MED-AME) Pilot Study. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 2016, 35, 621–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sáez-Almendros, S.; Obrador, B.; Bach-Faig, A.; Serra-Majem, L. Environmental footprints of Mediterranean versus Western dietary patterns: Beyond the health benefits of the Mediterranean diet. Environ. Health 2013, 12, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Demographic Data | Characteristics | Frequency (N) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | F | 97 | 97 |

| M | 3 | 3 | |

| Age | 18–20 | 29 | 29 |

| 21–23 | 50 | 50 | |

| 24–26 | 18 | 18 | |

| 27 and more | 3 | 3 | |

| Year of the study | 1 | 17 | 17 |

| 2 | 25 | 25 | |

| 3 | 24 | 24 | |

| 4 | 17 | 17 | |

| 5 | 17 | 17 | |

| The employment status | not working while studying | 55 | 55 |

| occasionally employed | 30 | 30 | |

| permanent employed | 15 | 15 |

| Number of values | 100 |

| Minimum | 10.00 |

| Maximum | 18.00 |

| Range | 8.000 |

| Mean (AS) | 13.39 |

| Std. Deviation (SD) | 1.632 |

| Std. Error of Mean (SEM) | 0.1632 |

| Statistic | Juniors | Seniors |

|---|---|---|

| Sum of ranks | 311.5 | 354.5 |

| Median score of correct answers (%) | 76.00 | 77.50 |

| number of items (n) | 18 | 18 |

| Mann–Whitney U | 140.5 | |

| p value | 0.5046 | |

| Difference: Actual | 1.500 | |

| Difference: Hodges-Lehmann | 3.000 | |

| Rank-biserial correlation (r) | 0.13 | |

| 95.29% CI of difference | −5.000 to 11.00 | |

| Question | Correct Answers, (%) (1st–3rd Year) | Correct Answers, (%) (4th–5th Year) | p-Value Fisher’s Exact Test | OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q1 | 76.0 | 74.0 | 0.8704 | 1.113 |

| (Healthy fats) | (0.5837–2.143) | |||

| Q2 | 79.0 | 97.0 | *** 0.0001 | 0.1163 |

| (Olive oil) | (0.03584–0.3668) | |||

| Q3 | 68.0 | 74.0 | 0.4360 | 0.7466 |

| (Fish frequency) | (0.4088–1.406) | |||

| Q4 | 79.0 | 85.0 | 0.3576 | 0.6639 |

| (Pyramid base) | (0.3151–1.407) | |||

| Q5 | 42.0 | 62.0 | ** 0.0070 | 0.4438 |

| (Legumes frequency) | (0.2545–0.7868) | |||

| Q6 | 76.0 | 79.0 | 0.7351 | 0.8418 |

| (Dairy consumption) | (0.4389–1.597) | |||

| Q7 | 67.0 | 74.0 | 0.3523 | 0.7166 |

| (Eggs frequency) | (0.3920–1.335) | |||

| Q8 | 86.0 | 79.0 | 0.2340 | 1.633 |

| (Drinks) | (0.7566–3.360) | |||

| Q9 | 73.0 | 79.0 | 0.4079 | 0.7187 |

| (Cooking method) | (0.3817–1.391) | |||

| Q10 | 70.0 | 71.0 | 1.0 | 0.9531 |

| (Type of bread) | (0.5321–1.748) | |||

| Q11 | 61.0 | 74.0 | 0.0696 | 0.5495 |

| (Red meat restriction) | (0.3067–1.000) | |||

| Q12 | 82.0 | 76.0 | 0.3856 | 1.439 |

| (Cardiovascular benefits) | (0.7393–2.936) | |||

| Q13 | 68.0 | 74.0 | 0.4360 | 0.7466 |

| (Vine consumption) | (0.4088–1.406) | |||

| Q14 | 86.0 | 82.0 | 0.5634 | 1.348 |

| (Fruit and vegetables) | (0.6367–2.763) | |||

| Q15 | 89.0 | 91.0 | 0.8143 | 0.8002 |

| (Refined sugars) | (0.3348–1.995) | |||

| Q16 | 88.0 | 88.0 | 1.0 | 1.000 |

| (Unsaturated fats) | (0.4341–2.303) | |||

| Q17 | 39.0 | 41.0 | 0.8853 | 0.9200 |

| (Olive oil fatty acids) | (0.5335–1.651) | |||

| Q18 | 86.0 | 82.0 | 0.5634 | 1.348 |

| (Nuts and seeds) | (0.6367–2.763) |

| Item No. | Statement | AS | SD |

|---|---|---|---|

| I1 | The Mediterranean Diet has a positive impact on the health of young people. | 4.40 | 0.60 |

| I2 | Regular consumption of Mediterranean foods can prevent the development of chronic diseases. | 4.25 | 0.67 |

| I3 | The Mediterranean Diet is suitable for people of all ages. | 4.24 | 0.70 |

| I4 | The Mediterranean Diet helps maintain optimal body weight. | 4.20 | 0.60 |

| I5 | Switching to a Mediterranean Diet requires significant lifestyle changes. | 2.95 | 1.21 |

| I6 | Information about the Mediterranean Diet is accessible and easy to understand for students. | 3.55 | 0.96 |

| I7 | The Mediterranean Diet has a positive impact on mental health. | 4.00 | 0.76 |

| I8 | The Mediterranean Diet is easy to implement in student life. | 3.27 | 0.88 |

| I9 | The Mediterranean Diet should be more widely promoted through the education system. | 4.36 | 0.59 |

| I10 | The Mediterranean Diet encourages responsible, sustainable behavior towards the environment. | 4.17 | 0.64 |

| Item No | AS (Juniors) | AS (Seniors) | p-Value t-Test | Cohen’s d |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I1 | 4.38 | 4.38 | 0.978 | 0.0 |

| I2 | 4.26 | 4.09 | 0.197 | 0.25 |

| I3 | 4.15 | 4.03 | 0.417 | 0.17 |

| I4 | 4.17 | 4.09 | 0.529 | 0.13 |

| I5 | 2.91 | 3.09 | 0.486 | −0.15 |

| I6 | 3.56 | 3.74 | 0.392 | −0.19 |

| I7 | 3.94 | 4.09 | 0.372 | −0.20 |

| I8 | 3.23 | 2.94 | 0.159 | 0.33 |

| I9 | 4.24 | 4.29 | 0.684 | −0.08 |

| I10 | 4.05 | 4.09 | 0.767 | −0.06 |

| Adherence Category | Number of Students |

|---|---|

| Low adherence (0–5) | 38 |

| Moderate adherence (6–9) | 57 |

| High adherence (10–14) | 5 |

| Years of Study | AS Score | Low Adherence N/% | Moderate Adherence N/% | High Adherence N/% | p-Value Fisher’s Exact Test | Cramér’s V |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Juniors

(1st–3rd year) | 5.93 | 23/34.84 | 38/57.57 | 5/7.57 | 0.2512 | 0.18 |

|

Seniors

(4th–5th year) | 5.79 | 15/44.11 | 19/55.88 | 0/0 |

| Employment Status | Not Working While Studying | Occasionally Employed | Permanent Employed |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of students | 55 | 30 | 15 |

| Minimum | 3.000 | 4.000 | 4.000 |

| Maximum | 10.00 | 9.000 | 9.000 |

| Range | 7.000 | 5.000 | 5.000 |

| Mean | 6.291 | 6.067 | 6.467 |

| Std. Deviation (SD) | 1.882 | 1.413 | 1.642 |

| Std. Error of Mean (SEM) | 0.2538 | 0.2579 | 0.4239 |

| ANOVA | SS | DF | MS | F (DFn, DFd) | p-Value | Eta-Squared η2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment (Between columns) | 1.805 | 2 | 0.9023 | F (2, 97) = 0.3050 | p = 0.7378 | |

| Residual (Within columns) | 286.9 | 97 | 2.958 | 0.006 | ||

| Total | 288.8 | 99 |

| Tukey’s Multiple Comparisons Test | Mean Diff. | 95.00% CI of Diff. | Adjusted p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| not working while studying vs. occasionally employed | 0.2242 | −0.7049 to 1.153 | 0.8341 |

| not working while studying vs. permanently employed | −0.1758 | −1.368 to 1.017 | 0.9345 |

| occasionally employed vs. permanently employed | −0.4000 | −1.695 to 0.8946 | 0.7431 |

| Fisher’s Exact Test | Low Adherence | Moderate Adherence | High Adherence | p-Value | Cramér’s V |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Not working (N = 55) | 22 | 28 | 5 | 0.3391 | |

| Occasionally employed (N = 30) | 11 | 19 | 0 | 0.14 | |

| Permanent employed (N = 15) | 5 | 10 | 0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Restović, I.; Jukić, A.; Kević, N. The Mediterranean Paradox: Knowledge, Attitudes, and the Barriers to Practical Adherence of Sustainable Dietary Behavior Among Future Educators—A Case Study of Teacher Education Students at the University of Split. Sustainability 2026, 18, 831. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18020831

Restović I, Jukić A, Kević N. The Mediterranean Paradox: Knowledge, Attitudes, and the Barriers to Practical Adherence of Sustainable Dietary Behavior Among Future Educators—A Case Study of Teacher Education Students at the University of Split. Sustainability. 2026; 18(2):831. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18020831

Chicago/Turabian StyleRestović, Ivana, Antea Jukić, and Nives Kević. 2026. "The Mediterranean Paradox: Knowledge, Attitudes, and the Barriers to Practical Adherence of Sustainable Dietary Behavior Among Future Educators—A Case Study of Teacher Education Students at the University of Split" Sustainability 18, no. 2: 831. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18020831

APA StyleRestović, I., Jukić, A., & Kević, N. (2026). The Mediterranean Paradox: Knowledge, Attitudes, and the Barriers to Practical Adherence of Sustainable Dietary Behavior Among Future Educators—A Case Study of Teacher Education Students at the University of Split. Sustainability, 18(2), 831. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18020831