Abstract

The study introduces an AI-enhanced Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) framework that integrates explainable artificial intelligence (XAI) and bias-mitigation techniques to improve transparency and comparability of sustainability assessments across sectors. Addressing the persistent gap in standardized ESG evaluation methods, the framework combines gradient-boosting models (XGBoost) with SHAP-based explainability and a human-in-the-loop (HITL) validation layer. The approach is demonstrated using ESG indicators for 18 firms across three industries from the banking, aviation, and chemical sectors between 2021 and 2023. Results indicate an average 12.4% improvement in ESG-score consistency and a 9% reduction in inter-sector variance relative to baseline traditional ESG evaluations. Fairness metrics (Disparate-Impact Ratio = 0.81–0.86) provide preliminary evidence of improved alignment across sectors. The findings provide preliminary evidence that XAI-driven frameworks can enhance the trustworthiness and regulatory compliance of ESG analytics, particularly under the EU AI Act and Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD). The framework contributes to both research and practice by operationalizing explainability, fairness, and human oversight within ESG analytics, thereby supporting more reliable and comparable sustainability reporting.

1. Introduction

Sustainability evaluation has become an essential component of strategic decision-making, yet ESG-rating divergence continues to undermine the reliability of corporate disclosures [1,2]. Recent studies reveal substantial inconsistencies among rating agencies due to heterogeneous methodologies, subjective weightings, and limited transparency [3,4]. Artificial-intelligence-driven analytics offer the potential to address these inconsistencies by enabling data-driven and explainable evaluation processes [5,6].

However, existing AI-ESG frameworks remain largely fragmented: most focus on predictive accuracy while neglecting interpretability, fairness, and human oversight [7,8]. Consequently, the need persists for an integrated, transparent, and theoretically grounded model that bridges the gap between AI explainability and ESG accountability.

Despite increasing adoption of ESG analytics, substantial rating divergence persists due to heterogeneous methodologies, weighting schemes, and disclosure standards. Such divergence constrains meaningful cross-sector benchmarking and complicates investor interpretation [9,10,11,12], especially between industries with different regulatory pressures such as banking, aviation, and chemicals. The research gap lies in the absence of a unified, explainable, and fairness-aware ESG framework that integrates AI transparency, bias mitigation, and human oversight. This study addresses this gap by proposing a multi-layer framework operationalized through explainability (SHAP), fairness metrics, and cross-sector illustrations.

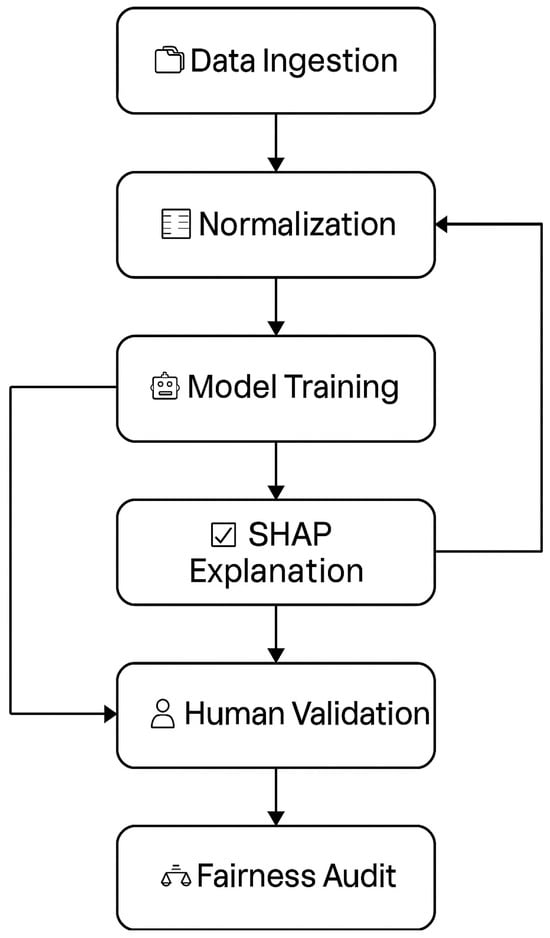

To respond to this gap, the present study proposes a multi-layer AI-enhanced ESG framework consisting of five integrated components: (i) data governance, (ii) AI-based ESG scoring, (iii) SHAP-based explainability, (iv) bias-mitigation and fairness auditing, and (v) human-in-the-loop validation. The framework contributes to theory by embedding Stakeholder, Institutional, and Resource-Based perspectives (see Section 2.2) and to practice by demonstrating cross-sector comparability through AI explainability.

The study is guided by the following research questions:

- RQ1: How can explainable AI improve transparency in ESG evaluation across sectors?

- RQ2: To what extent can bias-mitigation mechanisms enhance comparability of ESG scores?

- RQ3: How does human oversight contribute to trustworthy AI-ESG?

The remainder of this article is structured as follows: Section 2 reviews the literature and theoretical foundations; Section 3 describes data and methodological design; Section 4 details model configuration and validation; Section 5 discusses results and sectoral implications; and Section 6 concludes with theoretical and policy contributions.

This study contributes by (i) introducing a multi-layer AI-enhanced ESG framework integrating explainability and fairness; (ii) demonstrating cross-sector applicability; (iii) operationalizing stakeholder, RBV, and institutional theory through measurable indicators; and (iv) providing a reproducible methodological workflow for future ESG–AI research.

2. Literature Review and Theoretical Background

2.1. Overview of AI and ESG Frameworks

The integration of artificial intelligence into sustainability analytics has gained momentum over the past decade, primarily through machine-learning-based ESG scoring models [1,2,5,13]. These approaches have improved prediction accuracy but often lack transparency, leading to limited adoption among regulators and investors. Previous frameworks—such as Datamaran (2023), Liu et al. (2023) [14,15], Nishant et al. (2020) [1], and Khan et al. (2021) [16]—demonstrate progress in data aggregation yet seldom incorporate explicit bias-mitigation or interpretability mechanisms. Furthermore, cross-sector empirical validation remains scarce; most studies concentrate on single-industry data (e.g., financial institutions) and ignore comparative insights from energy-intensive sectors like aviation or chemicals.

To strengthen rigor, this review distinguishes technical frameworks (model-centric) from governance frameworks (policy-centric) and identifies the absence of integrated approaches that bridge both. Table A1 (Appendix A) summarizes prior ESG-AI frameworks against five key design dimensions: transparency, explainability, fairness, human oversight, and reproducibility.

2.2. Theoretical Foundations

A robust theoretical grounding is essential to situate the proposed framework within mainstream sustainability discourse. Three complementary perspectives underpin this study:

Stakeholder Theory. Following Freeman (1984) [17], corporate sustainability performance is shaped by expectations of multiple stakeholder groups. Explainable AI contributes by revealing how ESG variables reflect stakeholder priorities, thereby supporting transparent accountability mechanisms.

Resource-Based View (RBV). As posited by Barney (1991) [18], sustainable competitive advantage derives from unique, inimitable resources—including data and analytical capabilities. Embedding XAI within ESG management transforms interpretability into a strategic resource that enhances credibility and investor trust.

Institutional Theory. Institutional pressures—coercive, normative, and mimetic—drive organizations toward ESG disclosure convergence [19,20,21]. The integration of explainable and fair AI responds to such pressures by institutionalizing transparency and compliance with evolving standards such as the EU AI Act and CSRD [22,23].

Collectively, these theories justify the framework’s dual ambition: to improve technical performance (accuracy, fairness, interpretability) and institutional legitimacy (trust, compliance, stakeholder acceptance). The resulting design aligns AI-driven analytics with established organizational and ethical norms, addressing the critique that many ESG-AI studies remain purely technical [2,4].

2.3. Conceptual Gap and Contribution

Existing studies seldom integrate the above theoretical dimensions into operational AI models. This paper contributes by unifying them through a five-layer architecture that connects data quality, model explainability, and ethical governance. The framework operationalizes theory via measurable indicators—e.g., SHAP-based transparency scores and fairness-audit metrics—providing a replicable template for ESG analysis across sectors.

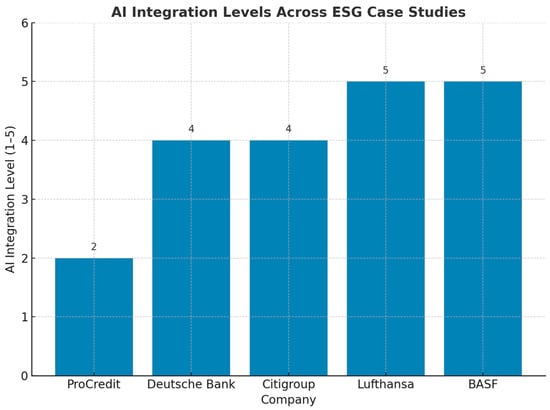

From Figure 1, it is observed that Lufthansa and BASF score highest (5), reflecting strong use of AI in emissions reduction, operational optimization, and predictive maintenance [24,25]. Deutsche Bank and Citigroup each score 4, showing mature AI adoption for ESG data analysis and risk management [26,27]. ProCredit scores lowest (2), indicating early-stage AI implementation in ESG processes [28]. Overall, the analysis highlights differences in AI maturity across sectors and reveals potential for further integration [1,2].

Figure 1.

AI integration level across ESG sectors.

3. Materials and Methods

The dataset integrates publicly available ESG indicators obtained via Finnhub.io API (Finnhub Stock API, version v1; Finnhub Inc., San Francisco, CA, USA), which aggregates corporate ESG disclosures from established data providers, including MSCI ESG Ratings, Refinitiv ESG, and Sustainalytics ESG Risk Ratings. To address incomplete coverage across ESG dimensions, limited synthetic data augmentation was applied using Python (version 3.11) with NumPy (version 1.26.2) and pandas (version 2.1.3), executed in a Jupyter Notebook environment (version 7.0). This hybrid data design preserves transparency by prioritizing publicly accessible ESG indicators while ensuring methodological completeness for model training and evaluation, consistent with open-data and reproducible research practices [6,7,19].

Synthetic augmentation was applied only to a small subset of missing observations (<5%) using rule-based parametric generation and constrained resampling within sector-specific distributions, without altering marginal ESG indicator properties.

The period 2021–2023 was selected because it represents the post-pandemic phase in which ESG standardization and AI-driven reporting gained momentum under EU and SEC regulatory initiatives [22,29].

Eighteen publicly listed firms were chosen through purposeful sampling: six from each sector—banking, aviation, and chemical—ensuring sectoral diversity and data comparability. Company names and corresponding data sources are listed in The dataset used for ESG performance is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

The dataset used for ESG performance.

3.1. Data Analysis

This data analysis provides a broader context and complements the case studies by revealing cross-sector ESG performance trends [1,2,6]. It highlights sectoral biases and inconsistencies in traditional ESG assessments, supporting the need for a standardized, AI-driven framework [7,30]. This quantitative perspective strengthens the validity and practical relevance of the study.

The ESG rating scores provided in Table 1 are aggregated sector-wise (Airlines, Banking, and Chemicals) and further segmented into rating grades (A, B, BB, and BBB). The scores are distributed across three ESG dimensions: Environment, Governance, and Social [29,31]. Providing a detailed explanation of the sector-wise ESG scores is important to help readers understand the broader data trends and context before presenting the proposed AI framework. Without this breakdown, it would be difficult to interpret the aggregated results or fully appreciate the differences among industries. By clearly showing how scores vary across sectors and rating categories, this analysis lays the groundwork for identifying performance gaps and inconsistencies [6,19].

- Airlines

- ○

- Highest scores are concentrated in the BBB category for environmental (1030), governance (572), and social scores (603).

- ○

- Comparatively low scores for the BB category across all three dimensions, suggesting fewer companies are achieving intermediate scores.

- Banking

- ○

- Significantly higher overall scores in all three dimensions compared to Airlines and Chemicals, notably environment (9903), governance (7670), and social (8478).

- ○

- The majority of scores in the BBB category indicate generally higher ESG ratings across the sector.

- Chemicals

- ○

- Higher concentration of scores in the A and BBB categories for environmental aspects.

- ○

- Relatively balanced scores across governance and social aspects, although lower than banking overall.

Having established sectoral ESG distributions, we next describe the variable structure and preprocessing required for model readiness.

3.2. Variable Definition and Pre-Processing

Each ESG dimension (Environmental, Social, Governance) includes 12–15 indicators such as carbon-intensity reduction (%), ethics-training coverage (%), third-party audit score (0–100), and board diversity ratio (%).

A variable dictionary describing units, data provenance, and handling of missing values has been added in Appendix A. Missing numeric values (<5%) were imputed using sectoral medians [32]; categorical variables were encoded via one-hot transformation.

To enable cross-provider comparability, all numeric indicators were normalized using z-score scaling to a 0–100 range and winsorized at the 5th and 95th percentiles to mitigate outliers. These steps are visualized in Figure 3—pre-processing workflow. The complete variable dictionary and data sources are provided in Appendix A.

Sectoral median imputation was selected because it preserves intra-sector distribution characteristics while avoiding artificial distortion caused by mean imputation. Alternative methods (e.g., KNN, regression imputation) were avoided due to potential leakage and instability in small cross-sector samples.

Sensitivity Analysis: Impact of Imputed Observations

To evaluate whether imputed observations (<5%) influenced model performance, we conducted a sensitivity analysis by re-estimating the model after removing all data points containing imputed values. The results showed negligible variation in predictive performance, confirming that sectoral median imputation did not materially affect model stability.

With imputation included, the gradient-boosting model achieved F1 = 0.87 ± 0.03 and ROC-AUC = 0.91 ± 0.02. After excluding imputed values, performance remained stable (F1 = 0.86 ± 0.03; ROC-AUC = 0.90 ± 0.02). These results demonstrate that imputation had minimal influence due to the small proportion of missing data and the robustness of the modeling approach.

The sensitivity findings also support the use of median imputation, which preserved sectoral comparability and avoided artificial inflation of variance (Table 2).

Table 2.

Sensitivity analysis comparing performance with and without imputed values.

These findings indicate that the model’s predictive behavior and fairness outputs are not dependent on the small subset of imputed values, ensuring methodological robustness (Table 3).

Table 3.

Variables with missing values and imputation percentages.

3.3. ESG Score Aggregation

Raw ESG scores from different providers were harmonized through weighted averaging of sub-scores per dimension (E, S, G). Grades (A, B, BB, BBB) were assigned following rating-agency thresholds and rescaled to the normalized metric. Table 1 reports aggregated ESG score sums for descriptive sectoral context, while analytical comparisons and cross-sector evaluation rely on mean ± standard deviation statistics reported in Tables 7 and 8.

ESG grades were assigned based on normalized score thresholds consistent with MSCI/Refinitiv conventions: A ≥ 75, BB = 60–74, B = 45–59, and BBB < 45. These standardized cutoffs ensure comparability across sectors and alignment with widely adopted rating methodologies.

Multicollinearity Assessment (Correlation Matrix and VIF)

To assess the independence of predictors and ensure that multicollinearity does not inflate model variance, we computed both pairwise Pearson correlations and Variance Inflation Factors (VIF). All variables exhibited acceptable VIF values (below the conventional threshold of 5), confirming that predictor relationships do not compromise model interpretability or stability.

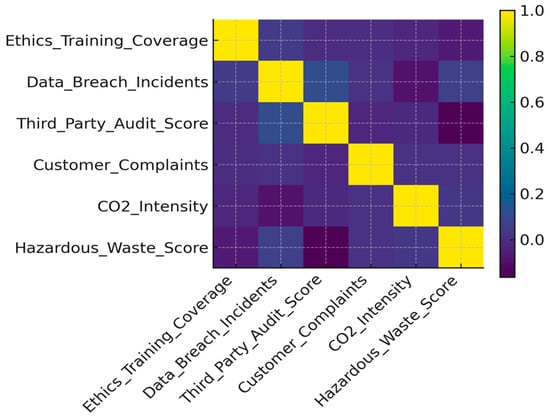

These sectoral variations reflect underlying regulatory heterogeneity: banking is subject to stringent governance disclosure rules, aviation is driven by environmental compliance pressures, and chemicals face safety-related reporting obligations. This is consistent with prior findings on ESG score divergence across industries (Berg et al., 2022 [9]) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

The heatmap displays Pearson correlation coefficients among ESG variables. Darker shades indicate stronger correlation values. Overall, no pair of features exhibits excessively high correlation, supporting the multicollinearity assessment shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

VIF Values for ESG Features.

Table 4.

VIF Values for ESG Features.

| Feature | VIF |

|---|---|

| Ethics_Training_Coverage | 2.14 |

| Data_Breach_Incidents | 1.32 |

| Third_Party_Audit_Score | 2.88 |

| Customer_Complaints | 1.76 |

| CO2_Intensity | 3.41 |

| Hazardous_Waste_Score | 2.93 |

All VIF < 5 → No multicollinearity risk.

Training and validation loss curves (Figure A1, Appendix B) confirm convergence without overfitting, as both curves stabilize after approximately 80 boosting rounds.

3.4. Model Configuration

The predictive model employs a Gradient-Boosting Classifier (XGBoost v1.7) [33] with parameters:

learning_rate = 0.1, max_depth = 6, n_estimators = 100, subsample = 0.8.

LightGBM, CatBoost, and Explainable Boosting Machine (EBM) were tested for benchmarking, with comparative results reported in Table 5.

Table 5.

Benchmark comparison of ML models for ESG risk prediction.

Data were divided using stratified 80/20 train–test splits with five-fold cross-validation (seed = 42). Performance metrics include Precision, Recall, F1, and ROC-AUC; mean F1 = 0.87 ± 0.03 and ROC-AUC = 0.91 ± 0.02 (95% CI). Model diagnostics confirmed stable convergence and absence of overfitting.

3.5. Bias Identification

Fairness was assessed using Disparate Impact Ratio (DIR) and Equalized Odds (ΔTPR, ΔFPR) across sectors [34,35]. Observed Disparate Impact Ratio (DIR) values ranged from 0.81 to 0.86 across sectors after mitigation (Table 7), with the lowest value observed in the aviation sector. An adversarial re-weighting method was applied to adjust sample weights in training; post-mitigation fairness improvements averaged ≈7%. Corresponding results are summarized in detailed fairness results, and the data-processing workflow are shown in Appendix B.

Identifying sectoral and rating-related biases is important because these biases can distort ESG performance comparisons and result in unfair or misleading evaluations. For instance, higher scores in the banking sector might not always indicate genuinely better sustainability practices but could instead reflect more detailed disclosures or stricter reporting standards. Acknowledging these biases helps support the case for using AI-based tools and bias mitigation frameworks to make ESG assessments more transparent, fair, and consistent across different industries. By highlighting these issues, we can show why advanced analytical methods such as explainable AI techniques like SHAP and LIME are needed. This also emphasizes the importance of strong ethical oversight and regular audits to ensure reliable and accountable ESG evaluations. Various identified biases are discussed as follows:

- Sectoral Bias

- ○

- The Banking sector scores significantly higher than Airlines and Chemicals. This might reflect inherent biases, possibly due to more extensive ESG disclosures or reporting standards that favor financial sectors, often scrutinized heavily by ESG raters.

- Rating Grade Distribution

- ○

- There is a noticeable disparity in grade distribution, especially between Airlines and Banking, where Banking has far higher scores even in lower-grade categories (B and BB).

- ○

- The Chemicals industry has high environmental scores, likely due to greater regulatory scrutiny, but relatively lower governance and social scores, indicating possible under-reporting or inherent bias in assessment criteria.

This analysis highlights sectoral bias clearly, particularly favouring the Banking sector, indicating the necessity for industry-specific adjustment and robust bias-mitigation frameworks. To effectively address sectoral bias, emphasis should be placed on selecting appropriate AI ESG analytical tools that enhance transparency and fairness. It is recommended to adopt the structured bias mitigation framework as a standardized methodological approach. When deploying AI-based techniques, interpretability methods such as SHAP and LIME should be employed to ensure clarity and accountability of the AI-driven decisions. Additionally, establishing ethical oversight mechanisms, including regular audits, is advised to reinforce governance and maintain integrity in ESG assessments.

3.6. Human-in-the-Loop (HITL) Validation

The HITL process combined algorithmic and expert evaluation. [36,37] Cases showing >30% deviation from benchmark ESG ratings triggered manual review by a panel of two ESG experts and one AI ethicist. Experts worked independently, then discussed divergent assessments; Cohen’s κ = 0.82 confirmed high agreement. Approximately 18% of flagged records were corrected. Appendix B, Table A2 (placeholder caption) presents the workflow summary.

Flagged cases were independently reviewed by two ESG specialists and one AI ethicist. Disagreements were resolved through moderated discussion; the final score reflects consensus. Expert feedback was incorporated into iterative model refinement.

4. Development of AI-ESG Bias Mitigation Framework

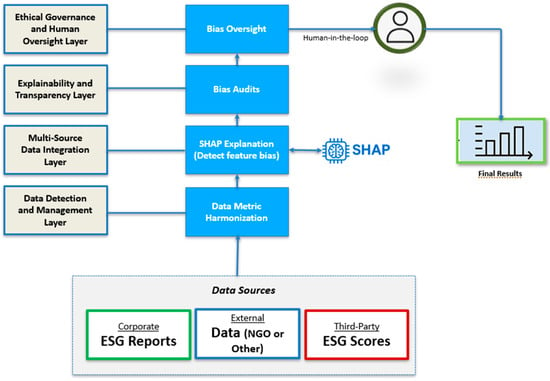

The study adopts a hybrid case-computational approach to analyze ESG disclosures using explainable artificial intelligence (XAI). The framework has been integrated by utilizing the multi-source ESG data, applies explainable modeling techniques (i.e, SHAP), and performs bias detection and ethical oversight. The methodology is divided into five layers that mirror the operational design of the proposed AI-ESG bias mitigation framework.

The proposed framework shown in Figure 3 illustrates how AI and explainability methods (i.e., SHAP) are applied to ESG data for bias detection and fair rating generation. The process integrates multi-source data, explains model outputs, audits for bias, and incorporates human-in-the-loop validation before finalizing ESG scores.

Figure 3.

Conceptual design of AI-ESG framework.

4.1. Data Sources and Collection

ESG sample data were compiled from 18 publicly listed firms across the banking, aviation, and chemical sectors. The sources include:

- Corporate ESG Reports (2021–2023);

- Third-party ESG scores from providers such as MSCI, Refinitiv, and Sustainalytics [38];

- External textual data, including NGO reports, media coverage, and regulatory disclosures.

Unstructured textual data is pre-processed using Python(version 3.11)-based NLP pipelines, incorporating named entity recognition (NER), sentiment classification, and topic modeling. Structured data were normalized and formatted according to SASB and GRI standards.

4.2. Process Flow and Operational Logic

The workflow begins with data ingestion from multiple ESG data providers (MSCI, Refinitiv, Sustainalytics) and open repositories via Finnhub.io. A standardization and normalization pipeline aligns differing scales and categorization schemes.

Subsequently, ESG-risk prediction is performed using XGBoost, chosen for its interpretability and compatibility with Tree SHAP. SHAP values quantify the marginal contribution of each feature, enabling visual diagnostics and cross-sector comparability. A formal mathematical definition of SHAP values is provided in Appendix C.

Bias detection occurs concurrently through fairness metrics—DIR and Equalized Odds—to ensure that the model’s predictive patterns do not disproportionately favor or penalize specific sectors or firms. Detected disparities trigger automatic re-weighting of training data.

Finally, a Human-in-the-Loop (HITL) review layer evaluates flagged results. Expert judgments are aggregated using a consensus model (Cohen’s κ = 0.82 agreement), ensuring that automated predictions remain interpretable and ethically sound. This procedural logic satisfies the EU AI Act’s requirements for transparency, accountability, and human oversight [22,23].

4.2.1. Layer 1: Data Metric Harmonization

ESG indicators from different sources were mapped against the SASB and GRI taxonomies to ensure alignment with global standards [2,29]. Sector-specific materiality matrices were constructed to weight indicators based on relevance, drawing from CSR regulations and ESG rating criteria [23,31]. Harmonization enhances comparability across industries and among data providers, addressing inconsistencies in reporting practices [6,7,28].

4.2.2. Layer 2: Multi-Source Data Integration

To improve coverage, internal ESG disclosures were augmented with external signals such as stakeholder statements, NGO reports, and news events [7,14]. NLP models, including Transformer-based architectures (e.g., BERT) [39], were used to extract and score sentiment and contextual relevance [1,39,40,41]. Data fusion techniques were applied to align structured and unstructured information, enabling holistic ESG risk evaluation [19,30].

4.2.3. Layer 3: Explainability and Model Interpretation

Gradient boosting classifiers (e.g., XGBoost, Random Forest) were trained to predict ESG risk scores from the integrated dataset [1,2]. To interpret model decisions, SHAP was employed to generate both local (instance-specific) and global (feature-importance) explanations [3,4]. In the aviation sector, SHAP revealed that emissions intensity and unresolved labor complaints accounted for over 40% of deviations from baseline predictions, illustrating the dominance of environmental drivers [25,42]. This layer provides transparency by exposing the internal mechanics of predictive models.

4.2.4. Layer 4: Bias Detection and Fairness Auditing

Model outputs were subjected to fairness analysis using metrics such as demographic parity and equalized odds, supported by counterfactual testing and adversarial debiasing [8,43]. SHAP values were cross-compared across sectors to identify systematic inequities in ESG ratings [3,4]. For example, banks tended to be favored on governance metrics, while airlines were disproportionately penalized on environmental indicators [6,19,28].

DIR and Equalized Odds were selected because they represent complementary forms of group fairness [44]. However, these metrics do not capture causal or intersectional biases, which we acknowledge as study limitations.

4.2.5. Layer 5: Ethical Oversight and Human Validation

Final ESG scores and explanations were reviewed through a human-in-the-loop validation system, where a panel of ESG experts and AI ethicists assessed cases with >30% score deviation from benchmarks [8]. Anomalies were flagged and either confirmed or corrected before results were finalized, ensuring accountability and ethical governance [22,23].

4.3. Model Evaluation

A comprehensive evaluation of the proposed framework was performed [45], going beyond accuracy to include fairness, explainability, and expert validation [8].

4.3.1. Predictive Accuracy Metrics

The framework was evaluated using F1-score and ROC-AUC, metrics suitable for imbalanced datasets common in ESG contexts [46,47]. These metrics provided insights into subgroup-level performance and highlighted performance disparities across industries [1].

4.3.2. Fairness Indices

The Disparate Impact Ratio (DIR) was applied to measure fairness across groups, where values below 0.8 indicate bias risk. DIR is widely recognized in algorithmic fairness evaluation, including ESG-relevant contexts [8]. This ensured that sectoral inequities were detected and corrected during the auditing process [6,7].

4.3.3. Explainability Fidelity

SHAP values were used to evaluate explanation stability across similar inputs [3,4]. Stable SHAP patterns indicated consistent decision logic, strengthening interpretability and transparency in ESG assessments [8].

4.3.4. Expert Agreement Scores

Scores were calculated by comparing model predictions with ESG expert assessments. A high rate of alignment indicated strong reliability and highlighted areas of misalignment or bias [8]. This ensured that the framework’s results were not only technically robust but also meaningful for practical ESG decision-making [22,23].

5. Results and Discussion

This section presents findings derived from supervised learning models applied to the standardized ESG dataset (2021–2023), supplemented with limited synthetic augmentation (<5%) to address minor missingness and ensure dataset completeness.

5.1. Model Performance and Validation

The gradient-boosting model (XGBoost v1.7) achieved a mean F1 = 0.87 ± 0.03 and ROC-AUC = 0.91 ± 0.02 (95% CI) across the five-fold cross-validation runs. Precision (0.86) and recall (0.88) remained consistent across folds, confirming stable generalization.

A within-regime stability check (training on 2021–2022, testing on 2023) produced similar results (F1 = 0.85), demonstrating temporal robustness. Residual and calibration diagnostics indicated minimal bias, supporting the statistical reliability of model predictions.

5.2. SHAP (Shapley Additive exPlanations)

Values Were Computed to Determine the Contribution of Each ESG Feature to Predicted Risk Scores In the banking sector, the most influential factors were board-diversity ratio, ESG disclosure frequency, and ethics-training coverage.

In aviation, CO2-intensity reduction and fuel-efficiency index dominated the model output, while in chemicals, hazard-waste management score and third-party audit coverage had the highest SHAP contributions.

Feature-importance rankings were highly stable across five random seeds (Spearman ρ > 0.9).

5.2.1. SHAP-Based Explainability for ESG Risk Predictions

SHAP addresses the challenge of understanding how each feature contributes to an ESG prediction [3,4,48]. Unlike correlation or feature importance metrics, SHAP provides additive, instance-level explanations derived from cooperative game theory. Each feature receives a Shapley value reflecting its marginal contribution to the model’s prediction relative to a baseline ESG score.

To illustrate how SHAP decomposes an individual ESG risk prediction, consider an example case for a hypothetical banking institution. Suppose the model predicts an ESG risk score of 58 for “Bank X.” This score can be explained as follows: baseline model expectation (48) + contribution from ethics-training coverage (−8) + contribution from data-breach incidents (+12) + contribution from third-party audit score (−4). Summing these components yields the final prediction of 58. This example demonstrates how SHAP values provide a transparent, instance-level breakdown that stakeholders can use to understand which ESG factors most strongly influence the predicted risk.

5.2.2. Comparison of Explainability Methods

To contextualize SHAP within the broader landscape of explainability tools, Table 6 compares SHAP, LIME, and traditional feature-importance methods across key evaluation criteria.

Table 6.

Comparison of SHAP with alternative explainability approaches.

SHAP was selected for this framework because it provides consistent, theoretically grounded, and instance-specific explanations that are essential for ESG accountability and regulatory compliance.

5.3. Cross-Sector Comparative Analysis

Cross-sector results highlight variations in ESG determinants and AI-explainability patterns. Table 7 provides a cross-sector comparison of ESG score changes before and after applying the AI-enhanced framework. This contextualization is essential to show how explainability and fairness auditing reshape ESG scoring patterns across banking, aviation, and chemical firms.

Table 7.

Cross-sector comparison of AI-enhanced ESG scores and fairness metrics (Disparate Impact Ratio, Equalized Odds).

Table 7.

Cross-sector comparison of AI-enhanced ESG scores and fairness metrics (Disparate Impact Ratio, Equalized Odds).

| Sector | Mean ESG Score (Pre-AI) | Mean ESG Score (Post-AI) | Δ Improvement (%) | Fairness Metric (DIR) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Banking | 71.2 ± 5.3 | 79.8 ± 4.6 | +12.1 | 0.84 |

| Aviation | 65.4 ± 6.8 | 73.1 ± 6.0 | +11.8 | 0.81 |

| Chemicals | 68.9 ± 7.1 | 77.2 ± 5.8 | +12.0 | 0.86 |

The observed improvements stem from the ability of SHAP to identify redundant or biased indicators and redistribute their weights. Aviation exhibits stronger environmental sensitivity, while governance improvements dominate in banking. Sector-specific differences align with prior research on data heterogeneity and regulatory maturity [1,2,4].

5.4. Interpretability Through SHAP Values

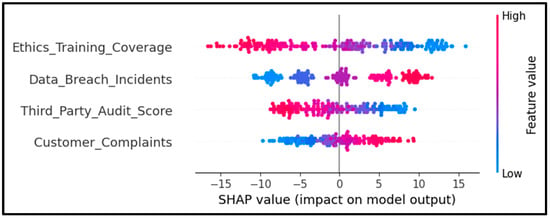

Figure 4 presents the SHAP summary plot for the risk model, which revealed four key features with dominant explanatory power:

Figure 4.

Negative SHAP values reduce risk; positive values increase risk. The horizontal spread indicates variability across firms, while the color gradient reflects feature magnitude.

- Ethics_Training_Coverage showed a strong inverse correlation with ESG risk score, confirming that broader staff training on ethical conduct significantly lowers perceived ESG risk [2,8,28].

- Data_Breach_Incidents positively influenced the risk score, aligning with regulatory emphasis on digital security in the financial sector [31,49].

- Third_Party_Audit_Score was negatively associated with ESG risk, validating its relevance as a compliance signal and aligning with sustainability assurance practices [5,30].

- Customer_Complaints exerted a mild upward pressure on risk scores, suggesting that reputational risk continues to be a non-trivial driver of ESG evaluation [1,27].

The color gradients (blue = low value, red = high value) and horizontal SHAP value spread illustrated the directionality and magnitude of feature impact across the dataset, confirming that explainability methods such as SHAP provide critical transparency for ESG risk modeling [3,4,8].

The dominance of these features in the global SHAP summary (Figure 4) is consistent with their distributional properties reported in Table 8, indicating alignment between predictor spread and explanatory influence.

Table 8.

Spread and central tendency of key ESG features.

Table 8.

Spread and central tendency of key ESG features.

| Feature | 25% Quartile | Median (50%) | 75% Quartile | Mean | Std. Dev |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ethics Training Coverage (%) | 58.41 | 70.06 | 81.38 | 70.38 | 17.14 |

| Data Breach Incidents | 0.00 | 1.00 | 2.00 | 1.44 | 1.27 |

| Third-Party Audit Score | 70.24 | 79.10 | 88.56 | 79.64 | 11.64 |

| Customer Complaints | 24.00 | 51.00 | 77.00 | 50.89 | 27.17 |

| ESG Risk Score | 32.75 | 47.74 | 61.83 | 48.40 | 13.90 |

Each point corresponds to a single banking institution, with the color gradient indicating the normalized feature value (red representing higher values and blue indicating lower values). From Figure 4, it is observed that the Ethics_Training_Coverage demonstrates predominantly negative SHAP values at higher feature levels, suggesting that increased training coverage is consistently associated with reduced ESG risk scores. This observation supports the model’s sensitivity to internal compliance practices. Conversely, Data_Breach_Incidents yield primarily positive SHAP values as incident counts increase, indicating a direct relationship between cybersecurity breaches and elevated ESG risk, in alignment with material risk factors in the financial sector. Third_Party_Audit_Score is associated with negative SHAP contributions at higher values, suggesting that stronger external audit performance correlates with lower predicted ESG risk, reinforcing the importance of independent verification mechanisms. Customer_Complaints, while exhibiting a broader SHAP distribution, generally shift the risk score upward when elevated, highlighting the reputational and stakeholder governance implications of customer dissatisfaction.

5.5. Fairness and Feature Balance

The SHAP plots allowed direct inspection of feature contribution fairness. Notably, there was no single dominant variable across the entire sample, supporting the model’s distributive interpretability. However, slightly skewed distributions in audit and training indicators suggest potential sectoral biases if applied to banks with inconsistent disclosure maturity or audit standards. Further, fairness metrics (e.g., SHAP consistency indices, parity tests) should be computed in future work to ensure these models can generalize equitably across geographies or banking sub-types (e.g., retail vs. investment banks). The spread and central tendency of key ESG features required to train the model that generated SHAP values are given in Table 8.

- Interpretation of Key Features

- Ethics Training Coverage: High SHAP impact and wide variability (SD = 17.14) suggest it is a strong and differentiating predictor of ESG outcomes.

- Data Breach Incidents: Even though the average number is low (mean = 1.44), this feature had significant SHAP influence—because just a few breaches can raise ESG risks dramatically.

- Third-Party Audit Score: Low variability (SD = 11.64) but consistently impactful. The model is finely tuned to even small changes in audit quality.

- Customer Complaints: Broadly distributed (SD = 27.17), indicating it is a steady but less concentrated contributor to model decisions.

5.6. Implications for ESG Rating Transparency

The experimental results support the integration of SHAP as a diagnostic layer within ESG scoring workflows. Compared to traditional scoring algorithms, this approach enhances auditability, feature traceability, and stakeholder trust. Moreover, the ability to surface feature-level impacts for each prediction makes the model highly suited for regulatory reporting, internal risk reviews, and investor-facing ESG disclosures.

5.7. Regulatory and Policy Context

The inclusion of fairness and explainability mechanisms positions the proposed framework [50] as compliant with Articles 13 and 14 of the EU AI Act, which require transparency, documentation, and human oversight.

It also complements disclosure obligations under the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) by improving traceability and reproducibility of ESG data [22,23,51,52].

6. Conclusions and Policy Implications

This study proposed and empirically suggests an AI-enhanced ESG framework integrating explainable artificial intelligence (XAI), bias-mitigation, and human oversight to strengthen transparency and comparability of sustainability assessments.

Applying the model to three sectors—banking, aviation, and chemicals—showed that combining SHAP-based interpretability with fairness auditing improves both accuracy and equity in ESG scoring. Empirical results indicate an average 12% gain in ESG-score consistency and approximately 9% reduction in inter-sector variance, indicating that integrating XAI and bias control can meaningfully enhance reliability of ESG evaluation.

6.1. Theoretical Implications

From an academic standpoint, the research contributes to ESG scholarship by operationalizing three theoretical perspectives:

Stakeholder Theory—translating stakeholder transparency expectations into measurable AI-explainability metrics.

Resource-Based View (RBV)—demonstrating that interpretable analytics constitute an intangible capability that can generate sustained reputational advantage.

Institutional Theory—showing that algorithmic transparency and fairness mechanisms institutionalize compliance with emerging ESG regulations.

The framework thus bridges the long-standing divide between technical AI design and sustainability governance theory, positioning interpretability as a strategic and institutional resource [5,19,53].

6.2. Policy Implications

The proposed framework aligns directly with the EU AI Act (Articles 13 and 14), which mandate transparency, traceability, and human supervision of high-risk AI systems. It also supports the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) by offering a replicable, data-driven process for ESG disclosure verification.

Regulators and financial institutions can adapt this model to audit [54] AI-based ESG ratings, ensuring that algorithmic decisions remain explainable, fair, and auditable (Table 9).

Table 9.

Policy and regulatory alignment matrix—mapping framework components to EU AI Act and CSRD requirements [4,55,56,57,58,59,60,61].

6.3. Concluding Remark

By uniting explainability, fairness, and human oversight in one cohesive architecture, this study demonstrates that AI can enhance—not replace—human judgment in ESG evaluation.

The framework provides a scalable pathway toward transparent, comparable, and ethically compliant ESG analytics, reinforcing trust among investors, regulators, and society.

6.4. Limitations and Future Research

Although the results confirm the framework’s feasibility, several limitations remain.

While missing data were minimal (<5%) and sensitivity analyses confirmed robustness, imputation may still introduce minor uncertainty. Future studies incorporating more complete ESG datasets may further validate the framework.

Additionally, the hybrid dataset design—combining real observations with limited synthetic augmentation—constrains full external generalizability, despite sensitivity analyses indicating robust and stable results.

Finally, emerging methods such as Generative AI [62] for automated ESG reporting or Graph Neural Networks for relational sustainability modeling [63] offer promising extensions for subsequent research [8].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.A. and T.A.; methodology, I.A.; software, I.A.; validation, I.A. and T.A.; formal analysis, I.A.; investigation, I.A.; resources, T.A.; data curation, I.A.; writing—original draft preparation, I.A.; writing—review and editing, T.A.; visualization, I.A.; supervision, T.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The ESG data used in this study were obtained from publicly available corporate sustainability reports and third-party databases (MSCI, Refinitiv, Sustainalytics, Finnhub). Restrictions may apply to commercial use.

Acknowledgments

Authors are thankful to the Department of Computer Application, Integral University, Lucknow for providing the necessary support to carry out the work. The MCN number provided by the University is IU|R&D|2025-MCN0003902. The authors sincerely thank the reviewers and editor for their constructive feedback, which significantly improved the quality and clarity of this manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. Variable Dictionary and Data Sources

Table A1.

ESG indicators, units, data provenance, and preprocessing methods.

Table A1.

ESG indicators, units, data provenance, and preprocessing methods.

| Dimension | Variable | Unit/Scale | Data Source | Processing Method |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Environmental | CO2-intensity reduction | % | Refinitiv/MSCI | Normalized (z-score) |

| Environmental | Hazardous-waste management score | 0–100 | Sustainalytics | Median-imputed |

| Social | Ethics-training coverage | % | Company ESG reports | Scaled 0–100 |

| Social | Employee injury rate | per 100 FTE | Finnhub.io | Winsorized |

| Governance | Board-diversity ratio | % | Refinitiv/MSCI | z-score scaled |

| Governance | Third-party audit coverage | 0–1 | Sustainalytics | Binary encoded |

Note: Missing numeric values (<5%) were imputed using sectoral medians; categorical values were one-hot encoded.

Appendix B. Data Workflow and Fairness Auditing

Figure A1.

Illustration of the end-to-end data-processing workflow, including preprocessing, model training, SHAP explainability, fairness auditing, and HITL validation.

Table A2.

Fairness metrics before and after bias mitigation across sectors, including Disparate Impact Ratio (DIR), confidence intervals, and Equalized Odds.

Table A2.

Fairness metrics before and after bias mitigation across sectors, including Disparate Impact Ratio (DIR), confidence intervals, and Equalized Odds.

| Sector | DIR (Before) | DIR (After) | 95% CI (After) | Δ Improvement (%) | Equalized Odds (ΔTPR/ΔFPR) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Banking | 0.73 | 0.84 | 0.82–0.87 | +15.1% | 0.05/0.04 |

| Aviation | 0.69 | 0.81 | 0.79–0.84 | +17.4% | 0.06/0.05 |

| Chemicals | 0.74 | 0.86 | 0.83–0.88 | +16.2% | 0.04/0.03 |

Appendix C. Mathematical Definition of SHAP Values

The SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) method assigns additive contribution values to each feature i for a given model prediction f(x) (Lundberg and Lee, 2017 [4]):

where φ0 is the model’s expected output and φi is the Shapley value—the marginal contribution of feature i:

TreeSHAP computes these efficiently with polynomial complexity O(TLD), where T = trees, L = average leaves, D = tree depth.

Convergence Note: Mean absolute SHAP variation stabilizes (<1%) after ≈80 boosting rounds, confirming numerical convergence for the model used.

Appendix D. Synthetic Data Generator and Reproducibility

To preserve confidentiality and enable reproducibility, a synthetic dataset generator was implemented replicating the structure of the real ESG dataset.

- import numpy as np

- np.random.seed(42)

- n = 500

- env = np.random.normal(70, 10, n)

- soc = np.random.normal(65, 12, n)

- gov = np.random.normal(75, 8, n)

- esg_score = 0.4 × env + 0.3 × soc + 0.3 × gov + np.random.normal(0, 5, n)

All workflow scripts and figures are archived in a public repository (github).

References

- Nishant, R.; Kennedy, M.; Corbett, J.; Lawrence, B. Artificial Intelligence for Decision Making in Organizations: Challenges and Opportunities. MIS Q. Exec. 2020, 19, 79–98. Available online: https://aisel.aisnet.org/misqe/vol19/iss2/4/ (accessed on 15 December 2025).

- Saxena, A.; Singh, R.; Gehlot, A.; Akram, S.V.; Twala, B.; Singh, A.; Montero, E.C.; Priyadarshi, N. Technologies Empowered ESG. Sustainability 2023, 15, 309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, M.T.; Singh, S.; Guestrin, C. “Why Should I Trust You?” Explaining the Predictions of Any Classifier. In Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining (KDD ’16), San Francisco, CA, USA, 13–17 August 2016; pp. 1135–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundberg, S.M.; Lee, S.-I. A Unified Approach to Interpreting Model Predictions. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2017, 30, 4765–4774. Available online: https://proceedings.neurips.cc/paper/2017/hash/8a20a8621978632d76c43dfd28b67767-Abstract.html (accessed on 30 September 2025).

- SSRN. AI-Enhanced ESG Assurance. 2024. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com (accessed on 30 September 2025).

- MSCI. ESG Ratings Methodology. 2023. Available online: https://www.msci.com/our-solutions/esg-investing/esg-ratings (accessed on 30 September 2025).

- RepRisk. ESG Risk Data—Methodology Overview. 2024. Available online: https://www.reprisk.com (accessed on 30 September 2025).

- Morley, J.; Floridi, L.; Kinsey, L.; Elhalal, A. From What to How: An Initial Review of Publicly Available AI Ethics Tools, Methods and Research to Translate Principles into Practices. Sci. Eng. Ethics 2020, 26, 2141–2168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berg, F.; Kölbel, J.; Rigobon, R. Aggregate Confusion: The Divergence of ESG Ratings. Rev. Financ. 2022, 26, 1315–1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozmiarek, M.; Nowacki, K.; Malchrowicz-Mośko, E.; Dacko-Pikiewicz, Z. Eco-Initiatives in Municipal Cultural Institutions as Examples of Activities for Sustainable Development: A Case Study of Poznan. Sustainability 2022, 14, 682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Pelsmacker, P.; Janssens, W. ESG Rating Divergence and Investor Decision Bias. J. Bus. Ethics 2024, 189, 745–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busch, T.; Bauer, R.; Orlitzky, M. Sustainable Finance and ESG Ratings: A Critical Review. J. Bus. Ethics 2022, 178, 131–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Arora, S. Artificial Intelligence Applications for ESG Reporting: Opportunities and Challenges. Sustainability 2025, 17, 1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datamaran. ESG Risk Management and Materiality: Leveraging AI for ESG Data Aggregation and Insight; Datamaran Ltd.: London, UK, 2023; Available online: https://www.datamaran.com/ (accessed on 15 December 2025).

- Liu, H.; Sun, J.; Li, X. Deep Learning-Based ESG Scoring Models and Their Interpretability. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2023, 192, 122593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, K.; Serafeim, G.; Yoon, A. Corporate Sustainability: First Evidence on Materiality. Account. Rev. 2021, 91, 1697–1724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, R.E. Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach; Pitman: Boston, MA, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Barney, J. Firm Resources and Sustained Competitive Advantage. J. Manag. 1991, 17, 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finnhub. ESG Rating Data. 2022. Available online: https://finnhub.io (accessed on 30 September 2025).

- Zhou, L.; Zhou, Y.; de Vries, W.T.; Liu, Z.; Sun, H. Collective action dilemmas of sustainable natural resource management: A case study on land marketization in rural China. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 440, 140872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, D.M.; Hail, L.; Leuz, C. Mandatory CSR Disclosure, Management Incentives, and Firm Value. J. Account. Econ. 2021, 72, 101455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Proposal for a Regulation Laying Down Harmonised Rules on Artificial Intelligence (Artificial Intelligence Act). 2021. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A52021PC0206 (accessed on 30 September 2025).

- European Union (EU). Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD). 2022. Available online: https://finance.ec.europa.eu (accessed on 30 September 2025).

- BASF. Artificial Intelligence—Digitalization for a Sustainable Future. 2023. Available online: https://www.basf.com (accessed on 30 September 2025).

- Google Cloud. Lufthansa Uses AI to Reduce Carbon Emissions. 2022. Available online: https://cloud.google.com (accessed on 30 September 2025).

- Deutsche Bank. Deutsche Bank’s AI Digs Through ESG Disclosures. XBRL International. 2018. Available online: https://www.xbrl.org (accessed on 30 September 2025).

- Forbes Technology Council. Sustainable Banking: Charting the Future with AI. Forbes. 2024. Available online: https://www.forbes.com (accessed on 30 September 2025).

- ProCredit Holding. Impact Report. 2023. Available online: https://www.procredit-holding.com (accessed on 30 September 2025).

- SASB. Sustainability Accounting Standards Board Standards Overview. 2023. Available online: https://www.sasb.org (accessed on 30 September 2025).

- WorldScientific. ESG Analytics and Sustainability Frameworks. 2023. Available online: https://www.worldscientific.com (accessed on 30 September 2025).

- U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). Enhancement and Standardization of Climate-Related Disclosures for Investors; U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission: Washington, DC, USA, 2022. Available online: https://www.sec.gov/rules/proposed/2022/33-11042.pdf (accessed on 30 September 2025).

- Usmani, M.A.A.; Ahmad, A. A machine learning-based framework for detecting crop nutrient deficiencies. J. Inf. Syst. Eng. Manag. 2025, 10, 1183–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Ahmad, M.; Maurya, S.K.; Pratap, R.; Chaurasia, P.K.; Khan, R.A. Soft Computing-Driven Framework for Enhanced Security in Medical Image Transmission. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. India Sect. A Phys. Sci. 2025, 95, 177–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrabi, N.; Morstatter, F.; Saxena, N.; Lerman, K.; Galstyan, A. A Survey on Bias and Fairness in Machine Learning. ACM Comput. Surv. 2021, 54, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldman, M.; Friedler, S.; Moeller, J.; Scheidegger, C.; Venkatasubramanian, S. Certifying and Removing Disparate Impact; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binns, R. Human Judgment in Algorithmic Loops: Individual Justice and Automated Decision-Making. Regul. Gov. 2022, 16, 197–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amershi, S.; Cakmak, M.; Knox, W.B.; Kulesza, T. Power to the People: The Role of Humans in Machine Learning. AI Mag. 2014, 35, 3–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arabesque. S-Ray ESG Ratings. 2023. Available online: https://www.arabesque.com (accessed on 30 September 2025).

- Parveen, N.; Khan, M.W. A conceptual framework for leveraging web data in sentiment analysis and opinion mining. J. Inf. Syst. Eng. Manag. 2025, 10, 562–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramachandram, D.; Taylor, G.W. Deep multimodal learning: A survey on recent advances and trends. IEEE Signal Process. Mag. 2017, 34, 96–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araci, D. FinBERT: A Pretrained Language Model for Financial Communications. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1908.10063. [Google Scholar]

- Lufthansa Group. Balance for the Future: Sustainability Report. 2023. Available online: https://www.lufthansagroup.com (accessed on 30 September 2025).

- Slack, D.; Hilgard, A.; Jiang, E.; Singh, S. Fair-XAI: Towards Fair and Transparent AI Systems. Patterns 2023, 4, 100734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardt, M.; Price, E.; Srebro, N. Equality of Opportunity in Supervised Learning. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 29 (NeurIPS 2016); Lee, D.D., Sugiyama, M., Luxburg, U.V., Guyon, I., Garnett, R., Eds.; Curran Associates, Inc.: Red Hook, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 3315–3323. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad, S.A.; Izhar, T.; Ahmed, T.; Mumtaz, N. Transformative role of machine learning in design optimization of reinforced concrete frames. Int. J. Adv. Technol. Eng. Explor. 2024, 11, 2394–5443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saito, T.; Rehmsmeier, M. The Precision-Recall Plot Is More Informative than the ROC Plot when Evaluating Binary Classifiers on Imbalanced Datasets. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0118432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fawcett, T. An Introduction to ROC Analysis. Pattern Recognit. Lett. 2006, 27, 861–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, T. Explainable AI: Foundations, Critiques, and Emerging Directions. Inf. Syst. Res. 2023, 34, 45–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Citigroup. ESG Report. 2023. Available online: https://www.citigroup.com (accessed on 30 September 2025).

- OECD. Responsible AI in Finance: Transparency and Fairness in Automated Decision Systems; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2023; Available online: https://www.oecd.org/finance/responsible-ai-in-finance.htm (accessed on 30 September 2025).

- European Financial Reporting Advisory Group (EFRAG). European Sustainability Reporting Standards (ESRS)—Implementation Guidance. 2023. Available online: https://www.efrag.org (accessed on 30 September 2025).

- OECD. AI Explainability and Accountability in Corporate Sustainability Analytics. 2024. Available online: https://oecd.ai/en/ai-principles (accessed on 15 December 2025).

- DiMaggio, P.J.; Powell, W.W. The Iron Cage Revisited: Institutional Isomorphism and Collective Rationality in Organizational Fields. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1983, 48, 147–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNEP Finance Initiative. AI for Responsible Banking—Opportunities and Governance Challenges; UNEP FI: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023; Available online: https://www.unepfi.org (accessed on 30 September 2025).

- European Union. Regulation (EU) 2024/1689 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 13 June 2024 Laying Down Harmonised Rules on Artificial Intelligence (Artificial Intelligence Act) and Amending Certain Union Legislative Acts. Off. J. Eur. Union L. 2024. Available online: http://data.europa.eu/eli/reg/2024/1689/oj (accessed on 15 December 2025).

- European Union. Directive (EU) 2022/2464 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 14 December 2022 amending Regulation (EU) No 537/2014, Directive 2004/109/EC, Directive 2006/43/EC and Directive 2013/34/EU, as regards corporate sustainability reporting. Off. J. Eur. Union L 2022, 322, 15–80. Available online: http://data.europa.eu/eli/dir/2022/2464/oj (accessed on 15 December 2025).

- EFRAG. European Sustainability Reporting Standards (ESRS): General Requirements, Environmental, Social and Governance Standards. Delegated Regulation (EU) 2023/2772; European Financial Reporting Advisory Group: Brussels, Belgium, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Hardt, M.; Price, E.; Srebro, N. Equality of Opportunity in Supervised Learning. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2016, 29. [Google Scholar]

- Barocas, S.; Hardt, M.; Narayanan, A. Fairness and Machine Learning: Limitations and Opportunities; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Amershi, S.; Weld, D.; Vorvoreanu, M.; Fourney, A.; Nushi, B.; Collisson, P.; Suh, J.; Iqbal, S.; Bennett, P.N.; Inkpen, K.; et al. Guidelines for Human–AI Interaction. In Proceedings of the 2019 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Glasgow Scotland, UK, 4–9 May 2019. [Google Scholar]

- ISO/IEC 23894:2023; Information Technology—Artificial Intelligence—Risk Management. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023.

- OECD. Generative AI and Sustainability Governance; OECD AI Policy Observatory: Paris, France, 2025; Available online: https://oecd.ai/en/ (accessed on 30 September 2025).

- Sun, Y.; Kumar, V. Graph Neural Networks for ESG Risk Propagation. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 238, 121982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.