Circular Economy in Rammed Earth Construction: A Life-Cycle Case Study on Demolition and Reuse Strategies of an Experimental Building in Pasłęk, Poland

Abstract

1. Introduction

Motivation

2. Literature Review

2.1. Embodied Carbon and Material-Related Emissions in Construction

- the type and amount of stabilizer used;

- the distance over which raw materials and products are transported;

- the production method and degree of processing.

2.2. Demolition, Waste Streams, and Circular Reuse Strategies

2.3. Research Gap and Methodological Limitations

3. Materials and Methods

- Manual demolition is assumed to generate no direct fossil-fuel-related emissions from demolition machinery; minor indirect emissions are acknowledged but considered negligible within the scope of this screening-level assessment.

- For mechanical demolition, an emission factor based on the ÖKOBAUDAT database for rammed earth walls with a density of 2000 kg/m3 was assumed to be 0.7134 kgCO2e/m3 in the C1 module. The product description in the ÖKOBAUDAT database states “During the disposal phase, manual dismantling is taken into account in Module C1 for plasters, mortar and construction boards made of clay, and a mechanical dismantling for staple walls and clay masonry.”

- The processes of grinding and granulation were considered part of the life-cycle of the new product (Modules A1–A3) and excluded from the system boundaries of the analyzed Modules C1–C2.

- Transport of the material is carried out using a 20-ton self-unloading vehicle. Combustion was assumed at 35 L/100 km for an unloaded vehicle and 45 L/100 km for a loaded vehicle, based on empirical data of users website forum www.wagaciezka.com.

- The emission factor for diesel fuel is 2.68 kgCO2/L, according to the guidelines [47] (categories 1.A.3.b.i–iv).

- The volumetric density of the walls was assumed based on ÖKOBAUDAT data—2000 kg/m3.

- The total volume of earth material to be demolished is 72.15 m3, of which, after accounting for 10% material losses, 64.93 m3 remains, equivalent to about 129.9 tons.

- For the transportation of the material, the number of trips of a 20-ton vehicle was estimated at 7.

- The excavation rehabilitation work is carried out by a backhoe-pusher with a bucket capacity of 0.15 m3. The total operating time of the machine was estimated at 16.5 h, with an assumed fuel consumption of 6 L/h and emissions of 2.68 kgCO2/L [47] (categories 1.A.3.b.i–iv).

- How do different demolition strategies (manual versus mechanical) influence greenhouse gas emissions associated with the end-of-life stage of rammed earth and related earth-based construction systems?

- How does the assumed transport distance for recovered earth materials affect the carbon footprint of end-of-life scenarios?

- Which end-of-life scenarios for earth-based materials offer the lowest embodied carbon emissions while supporting circular economy principles and material reuse?

3.1. Description of the Research Subject

3.1.1. Design Concept of Experimental Building in Pasłęk in Poland

3.1.2. Building Technologies and Materials Used in Experimental Building

4. Results and Discussion of Analysis of Experimental Building Constructed in Rammed Earth Technologies in Pasłęk in Poland in the Case of Development of Scenarios for the Reuse of Materials After Demolition

4.1. Identification of Materials Used in Construction of the Experimental Building in Pasłęk

4.2. Scenarios for Reuse and Demolition

4.2.1. Scenarios for Reinforced Concrete and Concrete Components

- crushed and reused as aggregate for new concrete production (recycled aggregate concrete);

- used as aggregate in earthworks for embankment or subgrade stabilization;

- used as additive in rammed earth construction for structural stabilization;

- used as filler or base layer in new construction (e.g., road foundations);

- crushed and reused for production of rubble concrete brick;

- crushed and used in gabion structures.

- reused as concrete blocks after careful demolition and mortar removal;

- crushed and used in gabion structures;

- crushed and reused as aggregate for new concrete production (recycled aggregate concrete).

- collected and recycled as scrap metal in steel mills;

- reused after mechanical straightening (if undamaged and permitted by standards);

- downcycled into low-grade steel products (e.g., fencing, mesh, small hardware).

4.2.2. Scenarios for Earth Components

- if allowed by local regulations and the material is environmentally neutral, it may be returned to the ground, for example, to backfill the excavation left after building removal;

- if not suitable for reuse in construction, it can be used as fill material or sub-base in road construction and earth embankments.

- because no additives were added to the mixture, it is possible to reuse the material after crushing and wetting and to form new elements;

- blocks can be defragmented and mixed with the compost and used as a soil.

- can be collected and used one more time as a soil.

4.2.3. Scenarios for Wood Elements

- wood unsuitable for structural reuse can be repurposed in garden architecture, such as pergolas, planters, fencing, or tool sheds;

- clean, untreated wood may be processed into particleboard or plywood, or used in glulam production;

- small off-cuts may serve as material for craftwork, decorative details, or custom furniture parts;

- low-grade or damaged dry wood without chemical treatments can be used as biomass fuel (e.g., firewood, wood chips);

- fine wood waste (e.g., sawdust, shavings), if free from contaminants, can be composted or applied as a carbon-rich soil amendment.

- disassembled structural components should be tested for strength by non-destructive methods. In the case of positive results allowing their reuse as structural components, they should be labeled and properly stored to preserve their parameters;

- if deemed unsuitable for reuse as structural elements, they can be cut into smaller pieces and used as interior finishes (floor, walls, celling) or for furniture.

- after carefully dismantling, they can be used as partition walls or greenhouses, or for building external walls in a warmer climate.

- after carefully dismantling, they can be cleaned and used one more time.

- repurposed for the construction of sheds, storage units, or fences in technical or agricultural contexts;

- if unsuitable for reuse due to damage or degradation, they can be used as fuel in biomass systems—provided no toxic preservatives are present;

- wood covered with bitumen or tar paper can be incinerated in specialized waste facilities or cement plants equipped with flue gas treatment and permits for co-incineration of bituminous waste;

- impregnated wood containing biocides or heavy metals must be handled as hazardous waste and disposed of in compliance with environmental regulations.

4.2.4. Scenarios for Glass Elements

- in case of damage and breakage, the glass can be used as raw material for foam glass production;

- after crushing, it can be used as glass grit for finishing applications (with mortar or plaster), for producing different elements, or for use in gabions;

- larger intact glass sheets can be cut and reused for non-structural glazing applications, such as interior partitions, greenhouse panels, or furniture inserts (e.g., tabletops, cabinet doors);

- finely ground waste glass (glass powder) can be used as a partial substitute for cement in concrete or mortar, reducing CO2 emissions and enhancing durability [50];

- in landscaping, crushed glass can be used as an aggregate for permeable surfaces, decorative mulch, or filler in drainage layers;

- recycled glass can also be used in the production of glassphalt—an asphalt mix that includes crushed glass, improving reflectivity and grip [51];

- clean container and flat glass waste can be used as a raw material in glass wool insulation, replacing virgin inputs such as sand and soda ash; increasing cullet content by 10% can reduce energy consumption in glass melting by up to 3% and significantly lower process-related CO2 emissions [52].

4.2.5. Scenarios for Stone Components

- if the mineral wool is dry, clean, and mechanically intact, it can be reused in non-load-bearing thermal insulation applications such as garden structures or sheds;

- contaminated or damaged material should be disposed of in accordance with construction waste regulations, as reuse can pose a health hazard (due to the release of fibers or mold);

- in some cases, mineral wool waste can be mechanically compacted and reused as filler in non-critical thermal or acoustic layers;

- if they are not suitable for reuse, they can be sent to mineral wool recycling plants, where they are melted down and processed into new insulation products or used as a substitute for aggregate in lightweight concrete.

- can be recovered, cleaned, and reused in landscaping, decorative gravel beds, or permeable surface layers;

- may be integrated into drainage systems or used as fill for gabion baskets or retaining structures;

- smaller or partially broken pebbles may be reused as bedding material under pavements or foundations.

- intact elements may be carefully removed and reused in flooring, steps, thresholds, or wall cladding in new buildings;

- damaged or broken stone can be cut into smaller tiles or used as crushed aggregate in construction or landscaping;

- esthetically unique fragments may be reused in mosaic finishes, garden paving, or as decorative facing stone.

4.2.6. Scenarios for Metal Elements

- steel elements such as posts, chains, gutters, or pipes can be directly reused in construction if they are not corroded or deformed—especially in secondary structures, formwork, or technical installations;

- flat metal sheets (e.g., zinc-titanium flashings, parapets, chimney caps) can be cut and reused as cladding, flashings, or protective panels on facades, roofs, or interiors;

- zinc-titanium air ducts can be flattened and reshaped for use in custom metalwork, furniture design, or artistic and architectural applications;

- if reuse is not possible, all metal components should be sorted by material type (e.g., steel, zinc, aluminum) and sent for recycling—significantly reducing the environmental impact compared to the original extraction and processing;

- recycled metals can re-enter the construction cycle in the form of rebar, sheet metal panels, hardware or structural frames, supporting a closed-loop economy in the construction sector.

4.2.7. Scenarios for Ceramic Components

- if undamaged, tiles can be carefully removed and reused in similar wall applications or decorative wall cladding;

- chipped or broken tiles can be crushed and reused in trencadís mosaics or as decorative infill in landscape paving;

- fragments may also be used as a backfill or drainage layer in non-structural applications.

- intact tiles may be cleaned and reused in new floors or wall finishes, especially in utility spaces or outdoor paving;

- damaged tiles can be crushed and used as aggregate in concrete or as ceramic gravel in garden paths and sub-base layers;

- fine ceramic waste may be used as a partial replacement for natural aggregate in mortars or as thermal mass filler in low-tech construction.

4.2.8. Scenarios for Other Materials and Units Identified in the Building

- expanded polystyrene (EPS) waste is significantly more difficult to recycle into its original form than many other plastics. Due to its low density, high volume, and challenges in collection and processing, a large proportion of EPS ends up in landfills.

- crushed and mixed with cement and sand to produce lightweight insulating material or infill for non-structural elements; such a mix can be used in the production of insulating mortars or lightweight concrete, including aerated concrete blocks [53];

- re-melting and granulation after cleaning, allowing for the production of new EPS-based products;

- bitumen membranes can be mechanically separated from wood or other substrates; this process is easier when the membrane is heated;

- recovered bitumen membranes can be sent for energy recovery in cement plants or asphalt recycling in the road industry.

- often damaged during deconstruction, but, if intact, may be reused as a moisture barrier in low-demand technical applications;

- otherwise, treated as construction plastic waste and sent to appropriate recycling or energy recovery streams.

- if removed without tearing, can be reused in temporary protective layers (e.g., during construction);

- if damaged, qualifies as mixed plastic waste—recycling may be limited depending on local infrastructure.

- if undamaged and not penetrated by roots, can be reused as a drainage layer separator in green roofs or large planters;

- if compromised, considered non-recyclable plastic waste, and must be directed to energy recovery or landfill, depending on contamination level and local policy.

4.3. Scenarios and Results of End-of-Life Analysis of Earth Technologies According to LCA

- The exterior walls, which consist of a 40 cm thick rammed earth bearing layer and an interior layer of adobe bricks (clay and straw), which were left exposed or covered with clay plaster.

- The partition walls were made of dried pressed earth blocks, produced from the same mixture as the rammed earth layer. The partition walls are 14 and 29 cm thick and are left unfinished—with no additional surface finish.

5. Conclusions and Perspective on Future Challenges

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| LCA | Life-Cycle Assessment |

| FA | Fly Ash |

| CCR | Calcium Carbide Residue |

| URE | Unstabilized Rammed Earth |

| SRE | Stabilized Rammed Earth |

| UCS | Unconfined Compressive Strength |

| CDW | Construction and Demolition Waste |

| EPS | Expanded Polystyrene |

| GWP | Global Warming Potential |

| LCC | Life-Cycle Cost |

| EPD | Environmental Product Declaration |

References

- European Environment Agency. Construction and Demolition Waste: Challenges and Opportunities in a Circular Economy; European Environment Agency: København, Denmark, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Environment Programme. Building Materials and the Climate: Constructing a New Future; United Nations Environment Programme: Nairobi, Kenya, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- World Green Building Council. Bringing Embodied Carbon Upfront: Coordinated Action for the Building and Construction Sector to Tackle Embodied Carbon; World Green Building Council: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Eberhardt, L.C.M.; Birgisdottir, H.; Birkved, M. Potential of Circular Economy in Sustainable Buildings. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2019, 471, 092051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caldwell, M. Is Timber the Most Sustainable Building Material? Buro Happold. 2021. Available online: https://www.burohappold.com/articles/is-timber-the-most-sustainable-building-material/ (accessed on 19 July 2025).

- Kyllmann, C. What Are the Best Materials for Sustainable Construction and Renovation? Clean Energy Wire. 2024. Available online: https://www.cleanenergywire.org/factsheets/what-are-best-materials-sustainable-construction-and-renovation (accessed on 19 July 2025).

- Fadiya, O.O.; Georgakis, P.; Chinyio, E. Quantitative Analysis of the Sources of Construction Waste. J. Constr. Eng. 2014, 2014, 651060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christoforou, E.; Kylili, A.; Fokaides, P.A.; Ioannou, I. Cradle to site Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) of adobe bricks. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 112, 443–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ÖKOBAUDAT. Process Data Set: Rammed Earth Wall; 2000 kg/m3. 2023. Available online: https://oekobaudat.de/OEKOBAU.DAT/datasetdetail/process.xhtml?uuid=4b42a944-ff7e-4540-a46b-c21074255143&version=20.24.070&stock=OBD_2024_I&lang=en (accessed on 19 July 2025).

- Ávila, F.; Puertas, E.; Gallego, R. Characterization of the mechanical and physical properties of stabilized rammed earth: A review. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 325, 126693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrigoni, A.; Beckett, C.; Ciancio, D.; Dotelli, G. Life cycle analysis of environmental impact vs. durability of stabilised rammed earth. Constr. Build. Mater. 2017, 142, 128–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, G.; Ñañez, R.; Zavaleta, D.; Burgos, V.; Kim, S.; Ruiz, G.; Pando, M.A.; Aguilar, R.; Nakamatsu, J. Eco-friendly additive construction: Analysis of the printability of earthen-based matrices stabilized with potato starch gel and sisal fibers. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 347, 128556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramezannia, A.; Gocer, O.; Bashirzadeh Tabrizi, T. The life cycle assessment of stabilized rammed earth reinforced with natural fibers in the context of Australia. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 416, 135034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cristelo, N.; Glendinning, S.; Miranda, T.; Oliveira, D.; Silva, R. Soil stabilisation using alkaline activation of fly ash for self compacting rammed earth construction. Constr. Build. Mater. 2012, 36, 727–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langmaack, H.; Scheibstock, P.; Schmuck, S.; Kraubitz, T. Climate and Employment Impacts of Sustainable Building Materials in the Context of Development Cooperation; Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ): Bonn, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Ajabi Naeini, A.; Siddiqua, S.; Cherian, C. A novel stabilized rammed earth using pulp mill fly ash as alternative low carbon cementing material. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 300, 124003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Indumathi, M.; Nakkeeran, G.; Roy, D.; Gupta, S.K.; Alaneme, G.U. Innovative approaches to sustainable construction: A detailed study of rice husk ash as an eco-friendly substitute in cement production. Discov. Appl. Sci. 2024, 6, 597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maskell, D.; Heath, A.; Walker, P. Comparing the environmental impact of stabilisers for unfired earth construction. Key Eng. Mater. 2014, 600, 132–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ÖKOBAUDAT. Process Data Set: Adobe; 1200 kg/m3. 2023. Available online: https://oekobaudat.de/OEKOBAU.DAT/datasetdetail/process.xhtml?uuid=4c009f04-44e1-42e3-a32e-4929294debab&version=20.24.070 (accessed on 19 July 2025).

- ÖKOBAUDAT. Process Data Set: Sand-Lime Brick. 2021. Available online: https://oekobaudat.de/OEKOBAU.DAT/datasetdetail/process.xhtml?uuid=cc0d7baa-755a-4a4a-baf3-4fe53d68a041&version=00.02.000&stock=OBD_2024_I&lang=en (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- FoCA FoCA—Free of Carbon Architecture Materials Database. 2024. Available online: https://foca.plgbc.org.pl/app/materials (accessed on 19 July 2025).

- Shashi, A.; Centobelli, P.; Cerchione, R.; Ertz, M.; Oropallo, E. What we learn is what we earn form sustainable and circular construction. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 382, 135183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geissdoerfer, M.; Savaget, P.; Bocken, N.M.P.; Hultink, E.J. The Circular Economy—A new sustainability paradigm? J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 143, 757–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pomponi, F. Alice Moncaster Circular economy for the built environment: A research framework. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 143, 710–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krajewska, A.; Siewczyńska, M. Circular Economy in the Construction Sector in Materials, Processes, and Case Studies: Research Review. Sustainability 2025, 17, 7029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kibert, C.J. Sustainable Construction: Green Building Design and Delivery; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Hebel, D.; Wisniewska, M.H.; Heisel, F. Building from Waste: Recovered Materials in Architecture and Construction; Birkhäuser: Berlin, Germany, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Sönmez, N.; Kalfa, S.M. Investigation of Construction and Demolition Wastes in the European Union Member States According to their Directives 1. Contemp. J. Econ. Financ. 2023, 2, 7–26. [Google Scholar]

- Okie, S. Worth it: Building Demolition and Reuse. TRELLIS. 2024. Available online: https://trellis.net/article/worth-it-building-demolition-and-reuse/ (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Rojat, F.; Hamard, E.; Fabbri, A.; Carnus, B.; McGregor, F. Towards an easy decision tool to assess soil suitability for earth building. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 257, 119544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrigoni, A.; Beckett, C.T.S.; Ciancio, D.; Pelosato, R.; Dotelli, G.; Grillet, A.C. Rammed Earth incorporating Recycled Concrete Aggregate: A sustainable, resistant and breathable construction solution. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2018, 137, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, M.; Faria, P.; Gago, A.S. Conservation of Defensive Military Structures Built with Rammed Earth. Buildings 2024, 14, 238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hattori, K. Recycling of Expanded Polystyrene Using Natural Solvents. In Recycling Materials Based on Environmentally Friendly Techniques; Achilias, D.S., Ed.; IntechOpen: Rijeka, Croatia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Mollehuara, M.A.; Cuadrado, A.R.; Vidal, V.L.; Camargo, S.D. Systematic review: Analysis of the use of D-limonene to Reduce the Environmental Impact of Discarded Expanded Polystyrene (EPS). IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2022, 1048, 012003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warsaw University of Technology; Olifierowicz, J.; Samobrod, A.; Truchan, K. Opis Patentowy, Preparat Wodochronny i Sposób Otrzymywania Preparatu Wodochronnego; Warsaw University of Technology: Warszawa, Poland, 2006; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Kozek, B.; Januszewski, M. Sustainable Production and Consumption: Design for Disassembly as a Circular Economy Tool; Foresight Brief 031; United Nations Environment Programme: Nairobi, Kenya, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Guerrierio, A.; Busio, F.; Saidani, M.; Boje, C.; Mack, N. Combining Building Information Model and Life Cycle Assessment for Defining Circular Economy Strategies. Sustainability 2024, 16, 4561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idir, R.; Djerbi, A.; Tazi, N. Optimising the Circular Economy for Construction and Demolition Waste Managment in Europe: Best Practices, Innovations and Regulatory Avenues. Sustainabilty 2025, 17, 3586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 14040:2006; Environmental Management—Life Cycle Assessment—Principles and Framework. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2006.

- ISO 14044:2006; Environmental Management—Life Cycle Assessment—Requirements and Guidelines. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2006.

- EN 15978:2011; Sustainability of Construction Works—Assessment of Environmental Performance of Buildings—Calculation Method. European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 2011.

- Górski, J.; Nowak, A.; Kołłątaj, M. Resilience of Raw-Earth Technology in the Climate of Middle Europe Based on Analysis of Experimental Building in Pasłęk in Poland. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Górski, J.; Klimowicz, J.; Nowak, A. Application of Pro-Ecological Building Technologies in Contemporary Architecture. In Proceedings of the XV International Conference on Durability of Building Materials and Components (DBMC 2020), Barcelona, Catalonia, 20–23 October 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Kelm, T.; Długosz-Nowicka, D. Budownictwo z Surowej Ziemi. Idea i Realizacja; Oficyna Wydawnicza Politechniki Warszawskiej: Warszawa, Poland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Kelm, T.; Górski, J.; Kołłątaj, M.; Gawrońska, P. Budownictwo z surowej ziemi: Ekologia i nowoczesny standard: Prezentacja realizacji budynku doświadczalnego, zlokalizowanego w Parku Ekologicznym w Pasłęku. Aparatura Badawcza i Dydaktyczna 2010, 15, 31–38. [Google Scholar]

- Niezabitowska, E. Metody i Techniki Badawcze w Architekturze; Wydawnictwo Politechniki Śląskiej: Gliwice, Poland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- EMEP; European Environment Agency. EMEP/EEA Air Pollutant Emission Inventory Guidebook 2019: Technical Guidance to Prepare National Emission Inventories; EEA Technical Report; European Environment Agency: København, Denmark, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Abuel-Naga, H. Unfired Bricks from Wastes: A Review of Satviliser Technologies, Performance Metrics and Circular Economy Pathways. Buildings 2025, 15, 1861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araujo Morselli, L.B.G.; Silveira Quadro, M.; Andreazza, R. Sustainable stabilized compressed earth blocks from construction and demolition waste. Sci. Pap. 2025, 30, e20240112. [Google Scholar]

- Islam, G.M.S.; Rahman, M.H.; Kazi, N. Waste glass powder as partial replacement of cement for sustainable concrete practice. Int. J. Sustain. Built Environ. 2017, 6, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tobi, G.A.; Abidemi, O.R.; Felix, O.M. The use of Crushed Waste Glass as a Partial Replacement of Fine Aggregates in Asphalt Concrete Mixtures (Glassphalt). J. Eng. Res. Rep. 2021, 21, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zier, M.; Stenzel, P.; Kotzur, L.; Stolten, D. A review of decarbonization options for the glass industry. Energy Convers. Manag. X 2021, 10, 100083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szczygielska, A.; Prejzner, H.; Geryło, R. Possibilities of recycling expanded polystyrene waste and problems related with this issue. IZOLACJE 2014, 19, 52–56. [Google Scholar]

- Nunes, A.; Palmeri, J.; Love, S. Deconstruction vs. Demolition: An Evaluation of Carbon and Energy Impacts from Deconstructed Homes in the City of Portland; DEQ Materials Management: Portland, OR, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- BC Materials. General Guide: Building Sustainably with Léém; Léém: Bruxelles, Belgium, 2023. [Google Scholar]

| Technology | Embodied Carbon (kgCO2e/m3) | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Adobe bricks (on-site) | 2.72 | [8] |

| Adobe bricks (industrial) | 19.91 | [8] |

| Adobe bricks | 95.00 | [15] |

| Adobe bricks (industrial) | 98.10 | [19] |

| Unstabilized Rammed Earth | 9.96 | [9] |

| Unstabilized Rammed Earth | 3.00 | [10] |

| Unstabilized Rammed Earth | 9.00 | [10] |

| Rammed Earth + 2.5% cement | 42.00 | [10] |

| Rammed Earth + 5% cement | 86.00 | [10] |

| Rammed Earth + 7.5–8% cement | 131.00 | [10] |

| Rammed Earth + 10% cement | 179.00 | [10] |

| Stabilized Rammed Earth with Portland cement | 131.00 | [18] |

| Stabilized Rammed Earth with hydraulic lime | 94.00 | [18] |

| Rammed Earth with natural additives | 10.00 | [18] |

| Rammed Earth with natural additives | 30.00 | [18] |

| Sand-lime bricks | 226.80 | [20] |

| Concrete bricks | 229.00 | [15] |

| Fired clay bricks | 312.00 | [21] |

| Fired clay bricks | 560.00 | [15] |

| No. | Material Group | Building Unit | Specification |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | Cement and concrete | ||

| A.1 | Reinforcement concrete | Foundation | B20, A-OStOS rods Ø12, horizontal rods Ø6 |

| Ring beam | nd | ||

| Ramp | nd | ||

| External stairs | nd | ||

| A.2 | Concrete blocks | Plinth wall | |

| A.3 | Mortar | Plinth wall | |

| A.4 | Cement screed | Slab on the grade | 6 cm, 10 cm |

| A.5 | Light concrete | Slab on the grade | 15 cm |

| B | Earth | ||

| B.1 | Rammed earth | External walls (one and three layers) | 40 cm sand, loam, clay, earth and Portland cement mix |

| B.2 | Pressed earth blocks | Partition walls | nd if stabilized |

| B.3 | Clay and straw blocks | Internal layer of three-layered wall | 12 cm, clay and straw mix |

| B.4 | Earth substrate | Green roof | |

| B.5 | Earth plaster | Interior plater | Clay, straw, sand |

| C | Wood | ||

| C.1 | Structural timber | Rafters | 14 × 28 cm spacing 90 cm |

| C.2 | Purlin | 14 × 28 cm | |

| C.3 | Wall plates | 14 × 14 cm | |

| C.4 | Timber frame | nd | |

| C.5 | Lintels | nd | |

| C.6 | Timber cladding | Internal and external finishing | Planed boards, matt varnish |

| C.7 | Technical wood | Boarding on the flat roof | 2.5 cm |

| Wood boards | Impregnated | ||

| C.8 | Building elements | Wood sills | |

| C.9 | Windows | Wood frame with glazing | |

| C.10 | Interior doors | Wood frame with glazing | |

| C.11 | Entrance doors | Wood frame and wood finish | |

| C.12 | Veranda | Wood frame with glazing | |

| D | Glass | ||

| D.1 | Double glazing | Windows | nd |

| D.2 | Veranda doors | nd | |

| D.3 | Curtain wall on veranda | nd | |

| E | Stone | ||

| E.1 | Pebbles stone | Plinth | |

| E.2 | Cut stone | Floor | |

| Ramp | |||

| E.3 | Mineral wool | Wall insulation | 8 cm |

| Timber frame wall with lintels | 18 cm | ||

| Roof insulation | 22 cm | ||

| F | Metal | ||

| F.1 | Struts | Roof structure in veranda | Steel |

| F.2 | Chains | Down pipes | nd |

| F.3 | Flashing | Roof and external sills | Zinc-titanium plate |

| Gutter and flashing | Coated steel | ||

| F.4 | Ventilation elements | Pipes | Zinc-titanium plate |

| F.5 | Chimney cover | Zinc-titanium plate | |

| F.6 | Angle bar | Green roof | Perforated aluminum |

| G | Ceramic | ||

| G.1 | Tiles | Walls in kitchen and toilet | |

| G.2 | Stoneware in toilet | ||

| G.3 | Brick | Chimney | |

| H | Others | ||

| H.1 | Polystyrene foam | Slab on the grade | 5 cm |

| H.2 | Asphalt saturated felt | Foundation | Glued |

| Green roof | Welded | ||

| H.3 | VCL | Frame structure, roof | |

| H.4 | Wind barrier foil | Frame structure | |

| H.5 | Geomembrane | Green roof | |

| D | Glass | ||

| D.1 | Double glazing | Windows | nd |

| D.2 | Veranda doors | nd | |

| D.3 | Curtain wall | nd | |

| E | Stone | ||

| E.1 | Pebbles stone | Plinth | |

| E.2 | Cut stone | Floor | |

| Ramp | |||

| E.3 | Mineral wool | Wall | 8 cm |

| Frame walls | 18 cm | ||

| Roof | 22 cm | ||

| F | Metal | ||

| F.1 | Struts | Roof structure | Steel |

| F.2 | Chains | Down pipes | nd |

| F.3 | Flashing | Roof and external sills | Zinc-titanium plate |

| Gutter and flashing | Coated steel | ||

| F.4 | Ventilation elements | Pipes | Zinc-titanium plate |

| F.5 | Chimney cover | Zinc-titanium plate | |

| F.6 | Angle bar | Green roof | Perforated aluminum |

| G | Ceramic | ||

| G.1 | Tiles | Walls in kitchen, toilet | |

| G.2 | Stoneware in toilet | ||

| G.3 | Brick | Chimney | |

| H | Others | ||

| H.1 | Polystyrene foam | Slab on the grade | 5 cm |

| H.2 | Asphalt saturated felt | Foundation | Glued |

| Green roof | Welded | ||

| H.3 | VCL | Frame structure, roof | |

| H.4 | Wind barrier foil | Frame structure | |

| H.5 | Geomembrane | Green roof | |

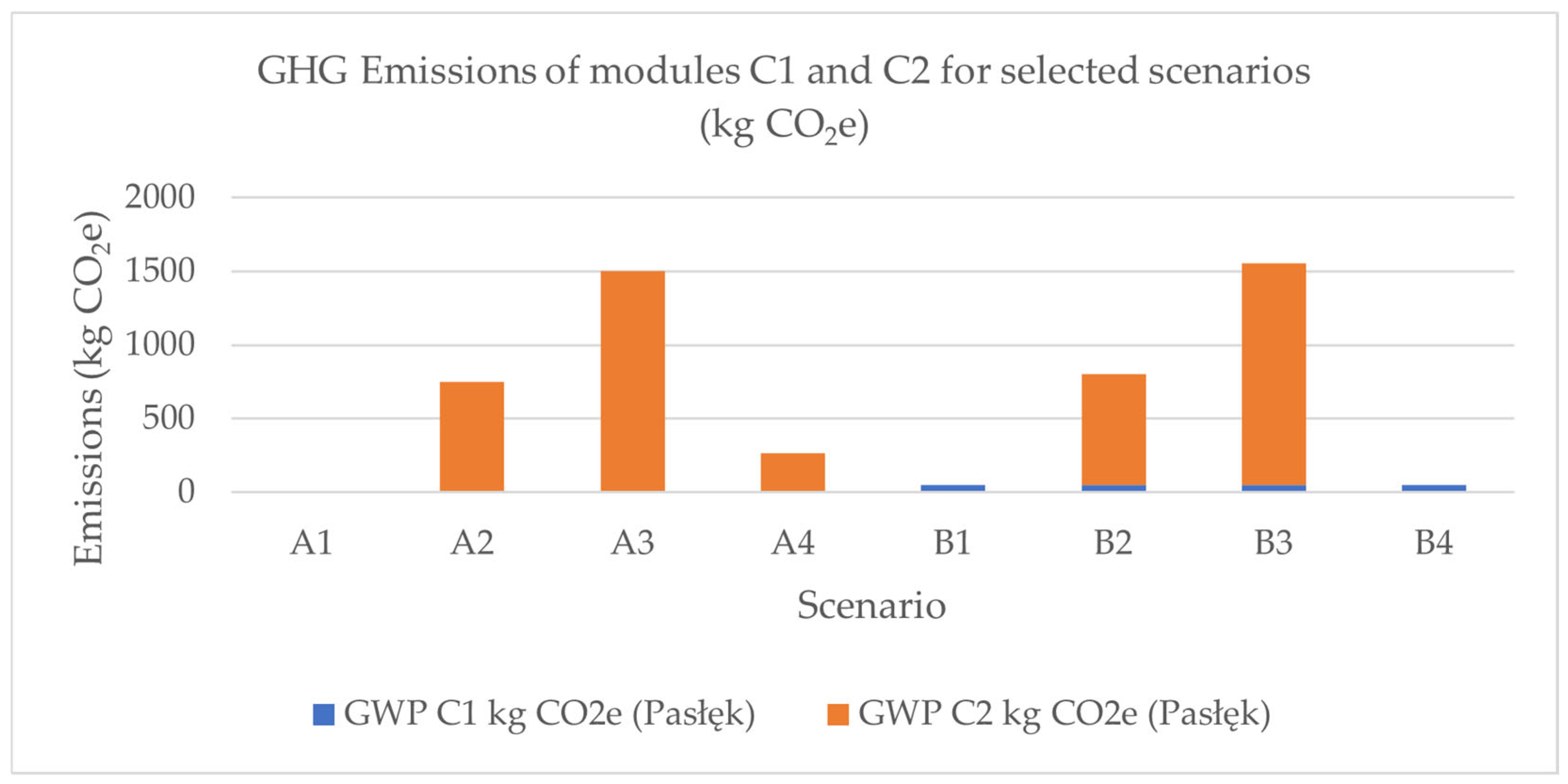

| Scenario | Demolition Method | Waste Management | Transport Distance [km] | GWP C1 (kgCO2e) | GWP C2 (kgCO2e) | GWP C1–C2 (kgCO2e) | GWP C1–C2 (kgCO2e/m3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A1 | Manual | On-site brick reuse (in situ recycling) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| A2 | Manual | Off-site brick reuse | 50 | 0 | 750.40 | 750.40 | 11.56 |

| A3 | Manual | Off-site brick reuse | 100 | 0 | 1500.80 | 1500.80 | 23.11 |

| A4 | Manual | On-site backfilling | 0 | 0 | 265.32 | 265.32 | 3.68 |

| B1 | Mechanical | On-site brick reuse (in situ recycling) | 0 | 51.47 | 0 | 51.47 | 0.71 |

| B2 | Mechanical | Off-site brick reuse | 50 | 51.47 | 750.40 | 801.87 | 12.27 |

| B3 | Mechanical | Off-site brick reuse | 100 | 51.47 | 1500.80 | 1552.27 | 23.83 |

| B4 | Mechanical | On-site backfilling | 0 | 51.47 | 0 | 316.79 | 4.39 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Nowak, A.P.; Pierzchalski, M.; Klimowicz, J. Circular Economy in Rammed Earth Construction: A Life-Cycle Case Study on Demolition and Reuse Strategies of an Experimental Building in Pasłęk, Poland. Sustainability 2026, 18, 790. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18020790

Nowak AP, Pierzchalski M, Klimowicz J. Circular Economy in Rammed Earth Construction: A Life-Cycle Case Study on Demolition and Reuse Strategies of an Experimental Building in Pasłęk, Poland. Sustainability. 2026; 18(2):790. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18020790

Chicago/Turabian StyleNowak, Anna Patrycja, Michał Pierzchalski, and Joanna Klimowicz. 2026. "Circular Economy in Rammed Earth Construction: A Life-Cycle Case Study on Demolition and Reuse Strategies of an Experimental Building in Pasłęk, Poland" Sustainability 18, no. 2: 790. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18020790

APA StyleNowak, A. P., Pierzchalski, M., & Klimowicz, J. (2026). Circular Economy in Rammed Earth Construction: A Life-Cycle Case Study on Demolition and Reuse Strategies of an Experimental Building in Pasłęk, Poland. Sustainability, 18(2), 790. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18020790