Digital Servitization Business Model Innovation Practices for Corporate Decarbonization in Manufacturing Enterprises: A Qualitative Meta-Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. BMI and the Strategic Imperative for CD

2.2. BMI in DS (DSBMI)

2.3. Synthesizing the Framework: Low-Carbon Business Models, CD Pathways, and the Role of DSBMI

3. Research Methods

3.1. Qualitative Meta-Analysis Approach

3.2. Data Sources and Collection

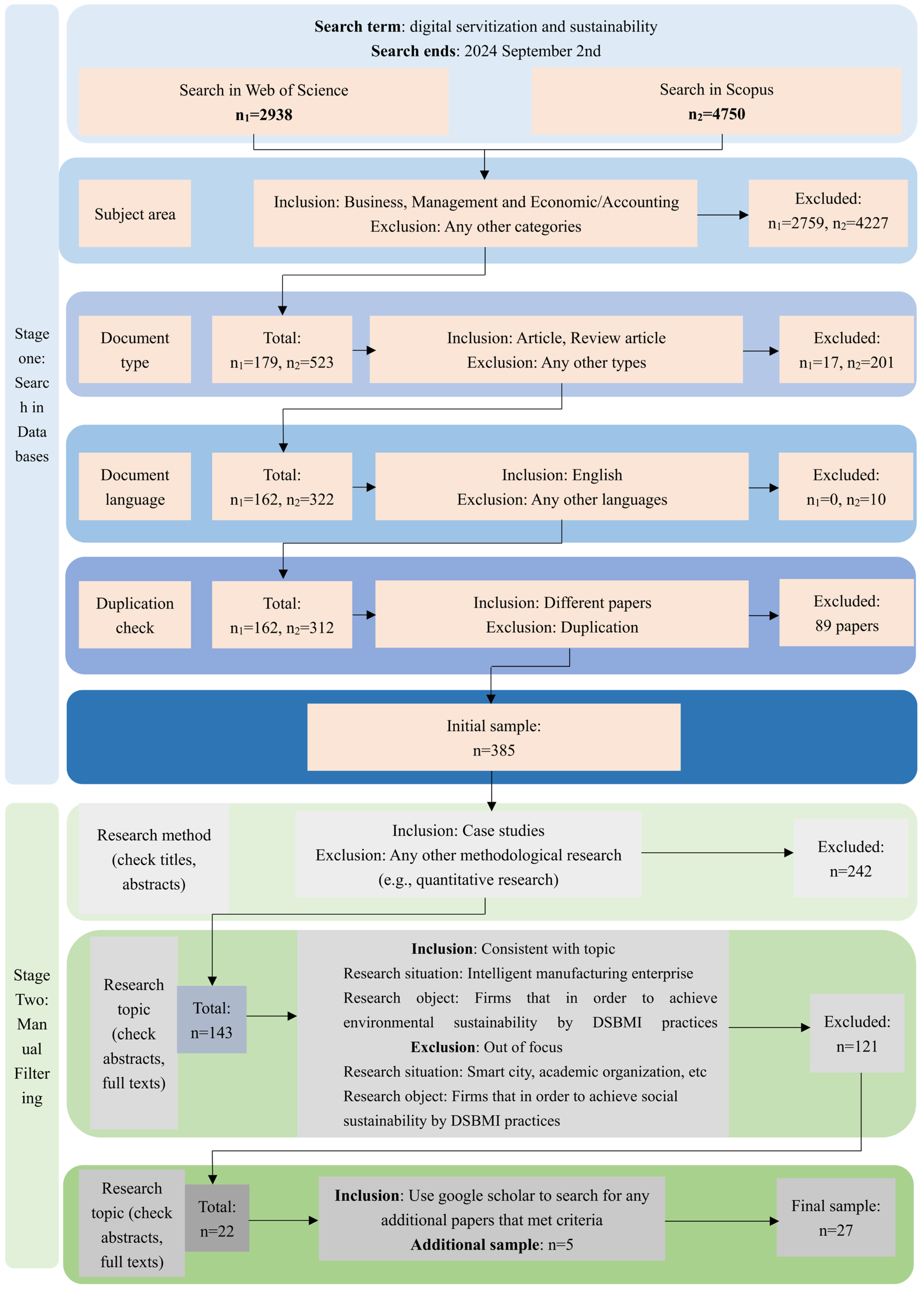

3.2.1. Stage One: Search in Databases

3.2.2. Stage Two: Manual Filtering Samples

3.3. Data Analysis

3.3.1. Stage Three: Within-Case Analysis of Samples

3.3.2. Stage Four: Cross-Case Analysis of Samples

4. Findings

4.1. Efficiency DSBMI Practices

4.1.1. Adding Digital Technology into Physical Products to Facilitate the Development of Digital Business Models

4.1.2. The Incorporation of Application Software into Enterprises to Enhance Agile Interaction

4.1.3. The Construction of Digital Platforms to Facilitate Efficient Collaboration Within Ecosystems

4.2. Novelty DSBMI Practices

4.2.1. Personalized Customization Services That Leverage Digital Technology

4.2.2. Services That Are Informed by AI Learning Capabilities

4.2.3. Solution Provider Practices

4.3. Convergent DSBMI Practices

4.3.1. The Establishment of Interconnectivity Between Front- and Back-End Company Operations Through the Use of Smart Connected Products

4.3.2. Convergence of Operations Across Organizational Boundaries via Digital Platforms

5. Discussion

5.1. The Promoting and Driving Roles Between Efficiency and Novelty DSBMI

5.2. The Foundational Support and Guiding Roles Towards Convergent DSBMI

5.3. The Gap-Filling and Quality-Enhancing Roles of Convergent DSBMI

5.4. Defining DSBMI for CD

6. Conclusions

6.1. Theoretical Contributions

6.2. Managerial Implications

6.3. Limitations and Avenues for Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aiello, F.; Cozzucoli, P.C.; Mannarino, L.; Pupo, V. Bayesian insights on digitalization and environmental sustainability practices. Towards the twin transition in the EU. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2024, 34, 417–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, S.; Yu, Y.; Zhang, N. The Effect of Digital Green Strategic Orientation On Digital Green Innovation Performance: From the Perspective of Digital Green Business Model Innovation. Sage Open 2024, 14, 21582440241261130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, M.-T.; Zhai, P.-M. Achieving Paris agreement temperature goals requires carbon neutrality by middle century with far-reaching transitions in the whole society. Adv. Clim. Change Res. 2021, 12, 281–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bataille, C.; Åhman, M.; Neuhoff, K.; Nilsson, L.J.; Fischedick, M.; Lechtenböhmer, S.; Solano-Rodriquez, B.; Denis-Ryan, A.; Stiebert, S.; Waisman, H.; et al. A review of technology and policy deep decarbonization pathway options for making energy-intensive industry production consistent with the Paris agreement. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 187, 960–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Towards an Ambitious Industrial Carbon Management for the EU; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Foxon, T.J. A coevolutionary framework for analysing a transition to a sustainable low-carbon economy. Ecol. Econ. 2011, 70, 2258–2267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sairanen, M.; Aarikka-Stenroos, L. Low-carbon business models: Review and typology. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2024, 123, 222–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakovirta, M.; Kovanen, K.; Martikainen, S.; Manninen, J.; Harlin, A. Corporate net zero strategy—Opportunities in start-up driven climate innovation. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2023, 32, 3139–3150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okereke, C.; Russel, D. Regulatory pressure and competitive dynamics: Carbon management strategies of UK energy-intensive companies. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2010, 52, 100–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, S.J.; Lewis, N.S.; Shaner, M.; Aggarwal, S.; Arent, D.; Azevedo, I.L.; Benson, S.M.; Bradley, T.; Brouwer, J.; Chiang, Y.M.; et al. Net-zero emissions energy systems. Science 2018, 360, eaas9793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghisellini, P.; Cialani, C.; Ulgiati, S. A review on circular economy: The expected transition to a balanced interplay of environmental and economic systems. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 114, 11–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.; Ming, X.; Liao, X.; Bao, Y.; Chen, Z.; Song, W. Sustainable value creation through customization for smart PSS models: A multi-industry case study. J. Manuf. Technol. Manag. 2024, 35, 29–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heirati, N.; Thornton, S.C.; Leischnig, A.; Henneberg, S.C. Capability configurations for successful advanced servitization. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2024, ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baines, T.; Ziaee Bigdeli, A.; Bustinza, O.F.; Shi, V.G.; Baldwin, J.; Ridgway, K. Servitization: Revisiting the state-of-the-art and research priorities. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2017, 37, 256–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, L.; Sun, W.; Parida, V. Consolidating digital servitization research: A systematic review, integrative framework, and future research directions. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2023, 191, 122478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Niu, N.; Song, X.; Zhang, B. Decoding the influence of servitization on green transformation in manufacturing firms: The moderating effect of artificial intelligence. Energy Econ. 2024, 139, 107875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akter, S.; Babu, M.M.; Hani, U.; Sultana, S.; Bandara, R.; Grant, D. Unleashing the power of artificial intelligence for climate action in industrial markets. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2024, 117, 92–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, G.; Merrill, R.K.; Schillebeeckx, S.J. Digital sustainability and entrepreneurship: How digital innovations are helping tackle climate change and sustainable development. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2021, 45, 999–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eggert, C.-G.; Winkler, C.; Volkmann, A.; Schumann, J.H.; Wünderlich, N.V. Understanding intra- and interorganizational paradoxes inhibiting data access in digital servitization. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2022, 105, 404–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohtamäki, M.; Parida, V.; Oghazi, P.; Gebauer, H.; Baines, T. Digital servitization business models in ecosystems: A theory of the firm. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 104, 380–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paschou, T.; Rapaccini, M.; Adrodegari, F.; Saccani, N. Digital servitization in manufacturing: A systematic literature review and research agenda. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2020, 89, 278–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D.J. Business Models, Business Strategy and Innovation. Long Range Plan. 2010, 43, 172–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohtamäki, M.; Leminen, S.; Parida, V. Conceptualizing digital business models (DBM): Framing the interplay between digitalization and business models. Technovation 2024, 133, 103013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karttunen, E.; Pynnönen, M.; Treves, L.; Hallikas, J. Capabilities for the internet of things enabled product-service system business models. Technol. Anal. Strateg. Manag. 2023, 35, 1618–1634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroeder, A.; Naik, P.; Ziaee Bigdeli, A.; Baines, T. Digitally enabled advanced services: A socio-technical perspective on the role of the internet of things (IoT). Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2020, 40, 1243–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paiola, M.; Schiavone, F.; Khvatova, T.; Grandinetti, R. Prior knowledge, industry 4.0 and digital servitization. An inductive framework. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2021, 171, 120963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, B.; Chen, W. Business model ambidexterity and technological innovation performance: Evidence from China. Technol. Anal. Strateg. Manag. 2016, 28, 583–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Xiao, Z.; Dong, M.C.; Gu, J. The fit between firms’ open innovation and business model for new product development speed: A contingent perspective. Technovation 2019, 86–87, 75–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Q.; Zhang, S.; Yu, H.; Cao, G. Exploring the Factors Influencing Business Model Innovation Using Grounded Theory: The Case of a Chinese High-End Equipment Manufacturer. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Q.; Gedajlovic, E.; Zhang, H. Unpacking Organizational Ambidexterity: Dimensions, Contingencies, and Synergistic Effects. Organ. Sci. 2009, 20, 781–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneckenberg, D.; Velamuri, V.K.; Comberg, C.; Spieth, P. Business model innovation and decision making: Uncovering mechanisms for coping with uncertainty. RD Manag. 2017, 47, 404–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hock-Doepgen, M.; Clauss, T.; Kraus, S.; Cheng, C.F. Knowledge management capabilities and organizational risk-taking for business model innovation in SMEs. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 130, 683–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sund, K.J.; Bogers, M.L.A.M.; Sahramaa, M. Managing business model exploration in incumbent firms: A case study of innovation labs in European banks. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 128, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Ichikohji, T. A review and analysis of the business model innovation literature. Heliyon 2023, 9, e17895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdelkafi, N.; Makhotin, S.; Posselt, T. Business model innovations for electric mobility—What can be learned from existing business model patterns? Int. J. Innov. Manag. 2013, 17, 1340003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ammar, O.; Ouakouak, M.L. The business model as a configuration of value: Toward a unified conception. J. Bus. Manag. Sci. 2015, 3, 78–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clauss, T. Measuring business model innovation: Conceptualization, scale development, and proof of performance. RD Manag. 2017, 47, 385–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, L.L.; Rindova, V.P.; Greenbaum, B.E. Unlocking the Hidden Value of Concepts: A Cognitive Approach to Business Model Innovation. Strateg. Entrep. J. 2015, 9, 99–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGrath, R.G. Business Models: A Discovery Driven Approach. Long Range Plan. 2010, 43, 247–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, B.; Yang, W.; Zhang, S.; Yan, S.; Xiang, Y. Linking the top management team transactive memory system, strategic flexibility and digital business model innovation: A dynamic capabilities perspective. Technol. Anal. Strateg. Manag. 2025, 37, 1621–1633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPCC. Climate change 2022: Impacts, adaptation, and vulnerability. In Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Pörtner, H.O., Roberts, D.C., Tignor, M., Poloczanska, E.S., Mintenbeck, K., Alegría, A., Craig, M., Langsdorf, S., Löschke, S., Möller, V., et al., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinkse, J.; Demirel, P.; Marino, A. Unlocking innovation for net zero: Constraints, enablers, and firm-level transition strategies. Ind. Innov. 2024, 31, 16–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Vaio, A.; Zaffar, A.; Chhabra, M.; Balsalobre-Lorente, D. Carbon accounting and integrated reporting for net-zero business models towards sustainable development: A systematic literature review. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2024, 33, 7216–7240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hertwich, E.G.; Wood, R. The growing importance of scope 3 greenhouse gas emissions from industry. Environ. Res. Lett. 2018, 13, 104013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D.J. Explicating dynamic capabilities: The nature and microfoundations of (sustainable) enterprise performance. Strateg. Manag. J. 2007, 28, 1319–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sjödin, D.; Parida, V.; Palmié, M.; Wincent, J. How AI capabilities enable business model innovation: Scaling AI through co-evolutionary processes and feedback loops. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 134, 574–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sklyar, A.; Kowalkowski, C.; Tronvoll, B.; Sörhammar, D. Organizing for digital servitization: A service ecosystem perspective. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 104, 450–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tronvoll, B.; Sklyar, A.; Sörhammar, D.; Kowalkowski, C. Transformational shifts through digital servitization. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2020, 89, 293–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sjödin, D.; Kamalaldin, A.; Parida, V.; Islam, N. Procurement 4.0: How Industrial Customers Transform Procurement Processes to Capitalize on Digital Servitization. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2023, 70, 4175–4190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapaccini, M.; Saccani, N.; Kowalkowski, C.; Paiola, M.; Adrodegari, F. Navigating disruptive crises through service-led growth: The impact of COVID-19 on Italian manufacturing firms. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2020, 88, 225–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamalaldin, A.; Sjödin, D.; Hullova, D.; Parida, V. Configuring ecosystem strategies for digitally enabled process innovation: A framework for equipment suppliers in the process industries. Technovation 2021, 105, 102250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sjödin, D.; Parida, V.; Kohtamäki, M.; Wincent, J. An agile co-creation process for digital servitization: A micro-service innovation approach. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 112, 478–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, A.G.; Mendes, G.H.S.; Ayala, N.F.; Ghezzi, A. Servitization and Industry 4.0 convergence in the digital transformation of product firms: A business model innovation perspective. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2019, 141, 341–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weking, J.; Stöcker, M.; Kowalkiewicz, M.; Böhm, M.; Krcmar, H. Leveraging industry 4.0—A business model pattern framework. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2020, 225, 107588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sjödin, D.; Parida, V.; Visnjic, I. How Can Large Manufacturers Digitalize Their Business Models? A Framework for Orchestrating Industrial Ecosystems. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2022, 64, 49–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Struyf, B.; Galvão, G.; Matthyssens, P.; Bocquet, R. The process of ecosystem orchestration: A meta-synthesis. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 133, 120–132. [Google Scholar]

- Brenner, B. Transformative Sustainable Business Models in the Light of the Digital Imperative—A Global Business Economics Perspective. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocken, N.M.P.; Short, S.W.; Rana, P.; Evans, S. A literature and practice review to develop sustainable business model archetypes. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 65, 42–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geissdoerfer, M.; Vladimirova, D.; Evans, S. Sustainable business model innovation: A review. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 198, 401–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Material Economics. Industrial Transformation 2050—Pathways to Net-Zero Emissions from EU Heavy Industry; University of Cambridge Institute for Sustainability Leadership (CISL): Cambridge, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Bocken, N.M.P.; de Pauw, I.; Bakker, C.; van der Grinten, B. Product design and business model strategies for a circular economy. J. Ind. Prod. Eng. 2016, 33, 308–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Business Models for the Circular Economy: Opportunities and Challenges for Policy; OECD: Paris, France, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, F.; Islam, N.; Chen, L. The role of technology-enabled business model innovation in achieving carbon neutrality. Technovation 2025, 147, 103305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naims, H. Economic aspirations connected to innovations in carbon capture and utilization value chains. J. Ind. Ecol. 2020, 24, 1126–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellen MacArthur Foundation. Completing the Picture—How the Circular Economy Tackles Climate Change; Ellen MacArthur Foundation: Cowes, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Lüdeke-Freund, F.; Gold, S.; Bocken, N.M.P. A review and typology of circular economy business model patterns. J. Ind. Ecol. 2019, 23, 36–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timulak, L. Meta-analysis of qualitative studies: A tool for reviewing qualitative research findings in psychotherapy. Psychother. Res. 2009, 19, 591–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoon, C. Meta-synthesis of qualitative case studies: An approach to theory building. Organ. Res. Methods 2013, 16, 522–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habersang, S.; Küberling-Jost, J.; Reihlen, M.; Seckler, C. A process perspective on organizational failure: A qualitative meta-analysis. J. Manag. Stud. 2019, 56, 19–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, J.; Coreynen, W.; Matthyssens, P.; Shen, L. Platform-based servitization and business model adaptation by established manufacturers. Technovation 2022, 118, 102222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, L.; Shi, Q.; Parida, V.; Jovanovic, M. Ecosystem orchestration practices for industrial firms: A qualitative meta-analysis, framework development and research agenda. J. Bus. Res. 2024, 173, 114463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohtamäki, M.; Rabetino, R.; Parida, V.; Sjödin, D.; Henneberg, S. Managing digital servitization toward smart solutions: Framing the connections between technologies, business models, and ecosystems. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2022, 105, 253–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Favoretto, C.; Mendes, G.H.S.; Oliveira, M.G.; Cauchick-Miguel, P.A.; Coreynen, W. From servitization to digital servitization: How digitalization transforms companies’ transition towards services. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2022, 102, 104–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Bommel, H.W.M. A conceptual framework for analyzing sustainability strategies in industrial supply networks from an innovation perspective. J. Clean. Prod. 2011, 19, 895–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engert, S.; Rauter, R.; Baumgartner, R.J. Exploring the integration of corporate sustainability into strategic management: A literature review. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 112, 2833–2850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guandalini, I. Sustainability through digital transformation: A systematic literature review for research guidance. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 148, 456–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Huang, Y.; Sun, H.; Zhi, B. Achieving sustainability in sharing-based product service system: A contingency perspective. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 332, 129997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piccarozzi, M.; Silvestri, C.; Aquilani, B.; Silvestri, L. Is this a new story of the ‘Two Giants’? A systematic literature review of the relationship between industry 4.0, sustainability and its pillars. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2022, 177, 121511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velte, P. Which institutional investors drive corporate sustainability? A systematic literature review. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2023, 32, 42–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adjei-Bamfo, P.; Djajadikerta, H.G.; Jie, F.; Brown, K.; Kiani Mavi, R. Public procurement for innovation through supplier firms’ sustainability lens: A systematic review and research agenda. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2023, 32, 387–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parmentola, A.; Petrillo, A.; Tutore, I.; De Felice, F. Is blockchain able to enhance environmental sustainability? A systematic review and research agenda from the perspective of Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Bus. Strategy Environ. 2022, 31, 194–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opferkuch, K.; Caeiro, S.; Salomone, R.; Ramos, T.B. Circular economy in corporate sustainability reporting: A review of organisational approaches. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2021, 30, 4015–4036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negri, M.; Cagno, E.; Colicchia, C.; Sarkis, J. Integrating sustainability and resilience in the supply chain: A systematic literature review and a research agenda. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2021, 30, 2858–2886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermelingmeier, V.; von Wirth, T. The nexus of business sustainability and organizational learning: A systematic literature review to identify key learning principles for business transformation. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2021, 30, 1839–1851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartolacci, F.; Caputo, A.; Soverchia, M. Sustainability and financial performance of small and medium sized enterprises: A bibliometric and systematic literature review. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2020, 29, 1297–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez Jaramillo, J.; Zartha Sossa, J.W.; Orozco Mendoza, G.L. Barriers to sustainability for small and medium enterprises in the framework of sustainable development—Literature review. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2019, 28, 512–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buzzao, G.; Rizzi, F. On the conceptualization and measurement of dynamic capabilities for sustainability: Building theory through a systematic literature review. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2021, 30, 135–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laubengaier, D.A.; Cagliano, R.; Canterino, F. It takes two to tango: Analyzing the relationship between technological and administrative process innovations in industry 4.0. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2022, 180, 121675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, R. Extended responsibility through servitization in PSS: An exploratory study of used-clothing sector. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. Int. J. 2016, 20, 453–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spring, M.; Araujo, L. Product biographies in servitization and the circular economy. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2017, 60, 126–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grubic, T.; Jennions, I. Remote monitoring technology and servitised strategies—Factors characterising the organisational application. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2018, 56, 2133–2149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cedeño, J.M.V.; Papinniemi, J.; Hannola, L.; Donoghue, I. Developing smart services by internet of things in manufacturing business. LogForum 2018, 14, 59–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holtström, J.; Bjellerup, C.; Eriksson, J. Business model development for sustainable apparel consumption: The case of Houdini Sportswear. J. Strategy Manag. 2019, 12, 481–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frishammar, J.; Parida, V. Circular Business Model Transformation: A Roadmap for Incumbent Firms. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2019, 61, 5–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Evans, S. Product-service system business model archetypes and sustainability. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 220, 1156–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabbour, C.J.C.; Fiorini, P.D.C.; Wong, C.W.Y.; Jugend, D.; Jabbour, A.B.L.D.S.; Seles, B.M.R.P.; Pinheiro, M.A.P.; da Silva, H.M.R. First-mover firms in the transition towards the sharing economy in metallic natural resource-intensive industries: Implications for the circular economy and emerging industry 4.0 technologies. Resour. Policy 2020, 66, 101596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marić, J. Exploring 3D printing technology in the context of product-service innovation: Case study of a business venture in south of France. Int. J. Bus. Environ. 2020, 11, 222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Visnjic, I.; Parida, V.; Zhang, Z. On the road to digital servitization—The (dis)continuous interplay between business model and digital technology. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2021, 41, 694–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haftor, D.M.; Climent, R.C. CO2 reduction through digital transformation in long-haul transportation: Institutional entrepreneurship to unlock product-service system innovation. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2021, 94, 115–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paiola, M.; Schiavone, F.; Grandinetti, R.; Chen, J. Digital servitization and sustainability through networking: Some evidences from IoT-based business models. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 132, 507–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reim, W.; Sjödin, D.; Parida, V. Circular business model implementation: A capability development case study from the manufacturing industry. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2021, 30, 2745–2757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, K.; Zhang, Y.; Chan, F.T.S.; Zhang, C.; Lv, J.; Liu, Q.; Leng, J.; Fu, H. A cyber-physical production monitoring service system for energy-aware collaborative production monitoring in a smart shop floor. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 297, 126599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fani, V.; Pirola, F.; Pezzotta, G.; Bandinelli, R.; Bindi, B. Design product service systems by using hybrid simulation: A case study in the fashion industry. In 26th Summer School “Francesco Turco”—Industrial Systems Engineering; Bergamo, Italy, 8–10 September 2021, Associazione Italiana dei Docenti di Impianti Industriali: Bergamo, Italy, 2021; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Moro, S.R.; Cauchick-Miguel, P.A. Analysis of a Bike-Sharing System from a Business Model Perspective. Braz. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2022, 19, e20221400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomson, L.; Kamalaldin, A.; Sjödin, D.; Parida, V. A maturity framework for autonomous solutions in manufacturing firms: The interplay of technology, ecosystem, and business model. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2022, 18, 125–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sjödin, D.; Parida, V.; Kohtamäki, M. Artificial intelligence enabling circular business model innovation in digital servitization: Conceptualizing dynamic capabilities, AI capacities, business models and effects. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2023, 197, 122903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laur, I.; Berntzen, L. Opposing forces of business model innovation in the renewable energy sector: Alternative patterns and strategies. Int. J. Entrep. Innov. 2023, 0, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.; Pi, Y. Digital technologies and product-service systems: A synergistic approach for manufacturing firms under a circular economy. J. Digit. Econ. 2023, 2, 37–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asi, A.D.T.; Floris, M.; Argiolas, G. Digital servitization bridging relational asymmetry. TQM J. 2024, 36, 2657–2675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rong, K.; Luo, Y. Toward born sharing: The sharing economy evolution enabled by the digital ecosystems. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2023, 196, 122776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miehé, L.; Palmié, M.; Oghazi, P. Connection successfully established: How complementors use connectivity technologies to join existing ecosystems—Four archetype strategies from the mobility sector. Technovation 2023, 122, 102660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattos, C.A.; Novais Filho, M.J. Mechanisms to develop a business model through the Internet of Things: A multiple case study in manufacturing companies. Technol. Anal. Strateg. Manag. 2024, 36, 2890–2906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcayaga, A.; Hansen, E.G. Smart circular economy as a service business model: An activity system framework and research agenda. RD Manag. 2024, 55, 508–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turienzo, J.; Blanco, A.; F. Lampón, J.; Del Pilar Muñoz-Dueñas, M. Logistics business model evolution: Digital platforms and connected and autonomous vehicles as disruptors. Rev. Manag. Sci. 2024, 18, 2483–2506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gioia, D.A.; Corley, K.G.; Hamilton, A.L. Seeking qualitative rigor in inductive research: Notes on the Gioia methodology. Organ. Res. Methods 2013, 16, 15–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osterwalder, A.; Pigneur, Y. Business Model Generation: A Handbook for Visionaries, Game Changers, and Challengers; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Richardson, J. The business model: An integrative framework for strategy execution. Strateg. Change 2008, 17, 133–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldassarre, B.; Calabretta, G.; Bocken, N.M.P.; Jaskiewicz, T. Bridging sustainable business model innovation and user-driven innovation: A process for sustainable value proposition design. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 147, 175–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viciunaite, V.; Alfnes, F. Informing sustainable business models with a consumer preference perspective. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 242, 118417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Zhang, J. Business Model Innovation Paths of Manufacturing Oriented towards Green Development in Digital Economy. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 16454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Xie, W.; Wang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Huang, D. Antecedent Configurations and Performance of Business Models of Intelligent Manufacturing Enterprises. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2023, 193, 122550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, P.; Wang, Z.; Chen, C.H. Smart product-service systems: Anovel transdisciplinary sociotechnical paradigm. In Transdisciplinary Engineering for Complex Socio-Technical Systems; Hiekata, K., Moser, B.R., Inoue, M., Stjepandić, J., Wognum, N., Eds.; IOS Press BV: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; pp. 234–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| No. | Paper | Research Question | Industry/Firms | Examples of CD Content |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Pal (2016) [89] | How do firms extend their responsibilities through servitization in used-clothing PSS? | The textile-fashion industry/7 cases |

|

| 2 | Spring and Araujo (2017) [90] | How does the product life cycle affect its value and opportunities for reuse in the servitization and CE? | Manufacturing industry, automotive industry, IT hardware industry, etc./2 cases |

|

| 3 | Grubic and Jennions (2018) [91] | What are the characteristics of the organizational application of Remote Monitoring Technology (RMT) in the context of a service-oriented strategy? | Manufacturer/4 cases |

|

| 4 | Cedeño et al. (2018) [92] | How can manufacturing companies leverage the IoT from a customer-oriented perspective for developing smart services? |

| |

| 5 | Holtström et al. (2019) [93] | What are the key aspects of developing sustainable clothing consumption business models? | The apparel retailer Houdini Sportswear/1 case |

|

| 6 | Frishammar and Parida (2019) [94] | How does the transformation of circular business models actually occur in existing enterprises? | Manufacturing/8 cases |

|

| 7 | Yang and Evans. (2019) [95] | What is the sustainable value created in different archetypes of PSS business models? | Manufacturing/3 cases |

|

| 8 | Jabbour et al. (2020) [96] | How do manufacturing companies transition from linear manufacturing to the sharing economy? | Manufacturing/2 cases |

|

| 9 | Marić (2020) [97] | How can entrepreneurs develop business strategies to tackle the challenging 3D printing market? | Manufacturing/1 case |

|

| 10 | Chen et al. (2021) [98] | How is the DS business model of traditional product manufacturers changing? | Manufacturing/1 cases |

|

| 11 | Haftor and Climent. (2021) [99] | How can industrial organizations reduce the products that have a negative impact on the natural environment? | Manufacturing/1 cases |

|

| 12 | Paiola et al. (2021) [100] | How DS leads to sustainability? | Packaging machines and retail equipment/4 cases |

|

| 13 | Reim et al. (2021) [101] | What are the capability development and challenges of large manufacturing firms in implementing CBMs? | Manufacturing/3 cases |

|

| 14 | Ding et al. (2021) [102] | How to develop a cyber-physical production monitoring service system? | manufacturing/1 case |

|

| 15 | Fani et al. (2021) [103] | How to use hybrid simulation design for PSS in the fashion industry? | the fashion industry/1 case |

|

| 16 | Moro and Cauchick-Miguel. (2022) [104] | How to analyze the bike sharing system from the perspective of business model? | the bike-sharing industry/1 case |

|

| 17 | Thomson et al. (2022) [105] | How do industrial equipment manufacturers coordinate the development of technology, business models, and ecosystem relationships? | Manufacturing/4 cases |

|

| 18 | Sjödin et al. (2023) [106] | How can dynamic capabilities enable industrial enterprises to commercialize AI circular business model innovation (CBMI) in DS? | Manufacturing, transport solutions, shipping, construction, and mining/5 cases |

|

| 19 | Laur and Berntzen (2023) [107] | Why and how have the business models of the energy industry changed? | Digital utility provider, Information services, Electricity distribution and service, Energy services, Electro installations, Software services, Energy flexibility provider, Energy producer, It and computer-based services, IT services, Measurement equipment and service, Data and IT services, Electricity service and installations, Data and IT services, Electricity production and service/19 cases |

|

| 20 | Wu and Pi. (2023) [108] | How synergistic are the PSS and digital technology in manufacturing firms in a CE? | Manufacturing/3 cases |

|

| 21 | Asi et al. (2024) [109] | How can the DS model bridge the relational asymmetry between providers and customers? | Manufacturing/1 case |

|

| 22 | Chang et al. (2024) [12] | How is the current literature studying smart PSS, and why is customization crucial for it, especially in the field of sustainability? | Civil aviation industry, Automobile industry, Electronics industry, Marine equipment industry, Special equipment industry, Steel industry, Telecom and networking industry/7 cases |

|

| 23 | Rong and Luo (2023) [110] | What is the evolutionary path of the sharing economy? | Sharing economy/19 cases |

|

| 24 | Miehé et al. (2023) [111] | How can new complements use connectivity technology to align with the value proposition of existing ecosystems? | Autonomous transportation, digital mobility platforms/4 cases |

|

| 25 | Mattos et al. (2024) [112] | How can organizations develop new business models from the Internet of Things? | Manufacturing/3 cases |

|

| 26 | Alcayaga and Hansen (2024) [113] | What SCS activities have companies adopted to implement maintenance/repair, reuse, remanufacturing, and recycling strategies? | Machine building and heavy-duty vehicles, Components and equipment manufacturing/17 cases |

|

| 27 | Turienzo et al. (2024) [114] | Where, how, and by whom will the creation, capture, and delivery of value perceived by the customer be concentrated? | Telecommunications, oil, logistics, electrical suppliers, repair workshops, road infrastructure, insurance companies, consultancy/69 candidates |

|

| Theoretical Background | Central Themes | 1st Order Concepts (Deductive Codes) | Exemplary Papers |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rational positioning: BMI is an optimal design process for managers to respond to external changes and achieve value creation and capture. |

|

| (Abdelkafi et al., 2013 [35]; Ammar and Ouakouak, 2015 [36]; Clauss, 2017 [37]; Martins et al., 2015 [38]) |

| Evolutionary learning: Business model change arises from external uncertainty, values the role of routine, and emphasizes trial-and-error learning and incremental revision of BMI. |

|

| (Abdelkafi et al., 2013 [35]; Ammar and Ouakouak, 2015 [36]; Clauss, 2017 [37]; Martins et al., 2015 [38]) |

| Cognitive: It starts from within the enterprise, focuses on the role of managers’ mental models or schemas in business model changes, and points out that managers can help achieve BMI by changing their cognitive schemas. |

|

| (Abdelkafi et al., 2013 [35]; Ammar and Ouakouak, 2015 [36]; Clauss, 2017 [37]; Martins et al., 2015 [38]) |

| DSBMI Type | Specific Practices | Representative Literature Evidence |

|---|---|---|

| Efficiency DSBMI | Adding digital technology into physical products to facilitate the development of digital business models | Grubic & Jennions (2018) [91]; Rong & Luo (2023) [110]; Chen et al. (2021) [98]; Reim et al. (2021) [101] |

| The incorporation of application software into enterprises to enhance agile interaction | Cedeño et al. (2018) [92]; Sjödin et al. (2023) [63]; Holtström et al. (2019) [93]; Thomson et al. (2022) [105] | |

| The construction of digital platforms to facilitate efficient collaboration within ecosystems | Sjödin et al. (2023) [63]; Haftor & Climent (2021) [99]; Chen et al. (2021) [98]; Miehé et al. (2023) [111] | |

| Novelty DSBMI | Personalized customization services that leverage digital technology | Chang et al. (2024) [12]; Mattos & Novais Filho (2024) [112]; Paiola et al. (2021) [100]; Ding et al. (2021) [102] |

| Services that are informed by AI learning capabilities | Sjödin et al. (2023) [63]; Haftor & Climent (2021) [99]; Reim et al. (2021) [101] | |

| Solution provider practices | Frishammar & Parida (2019) [94]; Jabbour et al. (2020) [96]; Asi et al. (2024) [109]; Haftor & Climent (2021) [99] | |

| Convergent DSBMI | The establishment of interconnectivity between front- and back-end company operations through the utilization of smart connected products | Chen et al. (2021) [98]; Reim et al. (2021) [101]; Ding et al. (2021) [102]; Holtström et al. (2019) [93] |

| Convergence of operations across organizational boundaries via digital platforms | Sjödin et al. (2023) [63]; Mattos & Novais Filho (2024) [112]; Miehé et al. (2023) [111] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Sun, W.; Shen, L. Digital Servitization Business Model Innovation Practices for Corporate Decarbonization in Manufacturing Enterprises: A Qualitative Meta-Analysis. Sustainability 2026, 18, 742. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18020742

Sun W, Shen L. Digital Servitization Business Model Innovation Practices for Corporate Decarbonization in Manufacturing Enterprises: A Qualitative Meta-Analysis. Sustainability. 2026; 18(2):742. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18020742

Chicago/Turabian StyleSun, Wanqin, and Lei Shen. 2026. "Digital Servitization Business Model Innovation Practices for Corporate Decarbonization in Manufacturing Enterprises: A Qualitative Meta-Analysis" Sustainability 18, no. 2: 742. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18020742

APA StyleSun, W., & Shen, L. (2026). Digital Servitization Business Model Innovation Practices for Corporate Decarbonization in Manufacturing Enterprises: A Qualitative Meta-Analysis. Sustainability, 18(2), 742. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18020742