1. Introduction

In order to ensure environmental and sustainability principles, environmentally friendly green materials are increasingly used in the construction sector. Most often, materials of natural origin, waste, composites, or fibre reinforced materials are used [

1,

2,

3]. In building acoustics, in order to ensure acoustic comfort, as environmentally friendly green materials, organic, plant-based fibrous materials are often used [

4]. Recently, the acoustic properties of hemp fibre, hemp fibre composites, and hemp fibre-reinforced materials have been frequently studied as a sustainable alternative to conventional acoustic materials [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11].

The principles of the European Green Deal (EGD) and other European initiatives promote the reduction in greenhouse gas emissions, circular economy practices, efficient management of natural resources, and transition from fossil fuels to renewable energy sources. The cultivation of hemp for fibre contributes to the implementation of the objectives of the European Green Deal: hemp for fibre absorbs large amounts of carbon dioxide and is characterized by rapid biomass growth. The cultivation of hemp plants can absorb about 10 tons of CO

2 from the atmosphere during one growing season, while improving air quality, maintaining thermal balance, and having a positive impact on the environment [

12]. Hemp fibres are a sustainable alternative to conventional materials used in textiles, construction, and agriculture. Hemp plants are characterized by rapid biomass growth [

13]. Also, growing hemp plants reduces the amount of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere [

14,

15]. Hemp plants are characterized by high resistance to various pests, so insecticides and other measures for pest prevention are not used when growing them. Another positive aspect is that hemp plants can be grown in the same place all year round, since they do not deplete the soil and are not demanding on soil fertility [

16].

Based on the latest data, the cultivation of hemp in the European Union has increased significantly—from 20,540 hectares in 2015 to 33,020 hectares in 2022. The production of hemp increased from 97,130 tons to 179,020 tons. France is the largest producer—60% of EU production, Germany—17% and the Netherlands—5% [

17]. Although hemp fibre and straw are well studied worldwide, scientists emphasize the need for separate research for each region where hemp straw is grown, since the properties of hemp straw vary greatly due to the influence of environmental conditions in various growing areas [

18]. The main factors determining the differences are climate, soil structure, and precipitation. Hemp plants grown in different areas may differ in the length, thickness, and strength of their fibres.

From an acoustic perspective, hemp fibre is classified as a porous sound-absorbing material. The principle of operation of such materials is based on the fact that a sound wave, propagating through the material, enters a porous structure and, due to the friction of air molecules in the pore walls, the sound energy is dissipated and converted into thermal energy. As for the sound absorption of fibrous materials, it is known that sound absorption increases with decreasing fibre thickness, since their number and interaction with the propagating wave increase in volume. The sound absorption of fibrous materials increases when testing thicker fibre samples, and as the fibre is densified, its static airflow resistivity increases and sound absorption shifts to the lower frequency range.

Density of the porous material: This is the total mass of the material per unit volume [

19]. Studies show that increasing density usually improves sound absorption in the mid- and high-frequency ranges, but has little effect on low-frequency absorption. For example, the sound absorption of bamboo and hemp fibre boards is higher [

20,

21] when their density is higher, while the sound absorption properties of fibre glass change minimally in the same case [

22]. If the fibre density is too high, the sound wave penetration in the material becomes low, and the sound wave reflection occurs, which leads to a deterioration in sound absorption properties.

The thickness of the material has a significant effect on sound absorption, especially at lower frequencies. Studies show that sound absorption is proportional to the thickness of the material, and thicker materials are more effective at absorbing sound at low frequencies. Increasing the thickness of natural fibres shifts the absorption peak to lower frequencies and increases the overall absorption due to the longer sound wave scattering process and the interaction between air molecules and the material. Optimal sound absorption occurs when the thickness is approximately one-tenth of the sound wavelength [

23].

Another important aspect when considering the acoustic properties of hemp fibres is fibrous material porosity—the porosity of the fibres and the pores formed between intersecting or superimposed fibres. Porosity in materials allows sound waves to enter and disperse through air friction and the edges of pores in the material. Higher porosity leads to higher sound absorption of the material [

19].

Another important parameter is the fibre thickness of fibrous materials. Reducing the fibre diameter in materials increases their density, which affects the sound absorption coefficient. This is because the number of fibres of smaller thickness in the same volume increases, and at the same time, the number of obstacles in the path of the propagating sound wave increases. For this reason, the interaction between the sound wave and the material increases, and the sound absorption properties improve due to viscosity and friction. The fibre thickness of hemp fibre is predominantly from 17 to 23 μm, but this largely depends on the type of fibre and production technology [

16].

The airflow resistivity of the fibrous material is a very important parameter reflecting the sound absorption in fibrous materials. Higher airflow resistivity increases the dissipation of sound wave energy, since it increases friction in the material, thus the sound wave propagating through the material loses part of its amplitude. The airflow resistivity depends on the fibre diameter and the density of the material. It should be noted that the airflow resistivity remains constant with changing the thickness of the material under study, if the density is constant. The airflow resistivity of uncompressed hemp fibre ranges from 27.2 to 37.3 KPa·s/m

2 [

24].

The aim of the research is to investigate the acoustic properties of different types of hemp fibre and to determine their efficiency dependence on the fibre’s structure, density, thickness, and other physical parameters. This work complements our previous study [

25] by focusing on the different acoustic properties of the same fibres, highlighting new aspects not previously discussed.

2. Materials and Methods

In order to determine the acoustic parameters of a material, sound transmission loss in the material and sound absorption are studied. Sound absorption is the property of a material to convert sound energy into another form of energy. It is determined by the sound absorption coefficient α. Different materials reflect and absorb sound waves differently. Sound absorption depends on the thickness, density, and porosity of the test sample. A non-acoustic property of materials that has a significant impact on the acoustic parameters of the test materials, knowing which it is possible to predict the effectiveness of these parameters, is airflow resistivity, which mainly depends on the integrity of the material.

The aim of the research is to investigate the acoustic and non-acoustic properties of different types of hemp fibre and to determine the dependence of their efficiency on the fibre structure, density, thickness, and other physical parameters. By obtaining this information through experimental studies, it becomes possible to select acoustically efficient types of hemp fibre and use them in sound attenuating constructions.

This section presents experimental and theoretical research methodologies. Five different types of hemp fibre samples were tested: bleached (BHF), cottonized (CHF), boiled cottonized (BCHF), well-stripped decorticated (DWSHF), and short, not combed decorticated fibres (DSNCHF). The tested hemp fibres are presented in

Figure 1.

Microstructural analysis of various hemp fibres was performed using a Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM) to determine their morphological properties. A Scanning Electron Microscope, “FlexSEM1000 (Hitachi High-Tech Corporation, Minato-ku, Tokyo, Japan)” with an accelerating voltage of 15.0 kV, was used for the experiments. The magnification ranged from ×55 to ×1490.

When evaluating the airflow resistivity, sound absorption, and sound transmission loss of hemp fibre, samples with densities of 50, 100, 150, 200, and 250 kg/m3 were tested.

The hemp fibre was placed in 3D-printed moulds (

Figure 2). The mold diameter was 29.9 mm, and the wall thickness was 1.5 mm. Samples placed in 20, 40, and 60 mm long moulds were tested. A 20 mm thick and different density sample was used to determine the airflow resistivity, since airflow resistivity does not depend on the thickness of the material under test. Sound absorption is theoretically assessed by testing 20 mm thick fibre samples and later comparing the results with previous studies, which were conducted to determine the sound absorption of hemp fibres using an interferometer according to the ISO 10534-2:2023 standard [

26]. The results of the experimental study of sound absorption were presented in a previous study [

25] and are now used as data allowing comparison of the theoretical study data with the experimental data. The preparation for the sound absorption measurements of hemp fibre corresponded to the sound transmission loss tests performed with an interferometer. A more detailed description of the research methodology is given in [

25]

Each sample of hemp fibre of different density and type was tested by placing the fibre in a mould designed for this purpose. The required amount of fibre, knowing the volume of the mould, was weighed and placed in the mould, thus selecting the required fibre density. The hemp fibre was placed into the moulds by hand, gradually placing the fibre, evenly distributing the material throughout the mould volume, to avoid density irregularities. In order to match the mould dimensions, the fibre was easily pressed by hand to the height of the mould, without using additional pressing devices. The mass and density error of the hemp fibre samples did not exceed ±1%. The degree of compression was controlled by the geometric dimensions of the mould. The samples were kept, and measurements were made under standard laboratory conditions at a temperature of 23 ± 2 °C and a relative humidity of 50 ± 5%. In order to achieve accuracy of results, 3 measurements were performed for each measured fibre, each time placing the fibre in the mould anew and repeating the measurement. The

Section 3 presents the average of the results with the standard deviation.

2.1. Methodology to Determine Static Airflow Resistivity of Hemp Fibre

In order to predict the sound absorption properties of hemp fibre, the airflow resistivity of the test materials is determined. Static airflow resistivity determines the sound absorption of the material. It depends on the regularity of the fibre shape. Particles of a regular-shaped material lie close to each other, which reduces porosity and increases airflow resistance. Knowing the airflow resistivity of the material, numerical models and theoretical calculations can be used to predict the sound absorption and acoustic resistance of the fibre used. The airflow resistivity test is carried out according to the ISO 9053-1:2019 “Acoustics. Determination of airflow resistivity. Part 1. Static airflow method” [

27]. This method is based on the difference in air pressure between the open surfaces of the test sample created by unidirectional air movement. A stand used to determine the airflow resistivity is presented in

Figure 3.

Pressure is generated in the system using a compressor. The air in the stand moves through a long tube, which allows for an almost laminar airflow. The airflow velocity is determined using a Testo 452 airflow velocity metre (Testo SE & Co, Titisee-Neustadt, Germany). To measure the pressure difference, a Retrotec DM32 (Retrotec Inc., Everson, WA, USA) differential pressure gauge is used, the accuracy of which reaches 0.1 Pa. In order not to affect the accuracy of determining the resulting pressure difference, the airflow velocity generated in the stand reaches 0.01 m/s. When determining the airflow resistivity of the tested fibres, the airflow velocity (

v) and the air pressure difference (∆

P) are measured first according to ISO 9053-1:2019. Knowing the difference in air pressure, the airflow resistivity (

R) is calculated. The specific airflow resistivity (

Rs) is found by multiplying the airflow resistivity (

R) by the cross-sectional area of the test sample. The static airflow resistivity (

σ) of the test sample is expressed as the ratio of the specific airflow resistivity (

Rs) to the thickness of the sample (

d) [

27].

The static airflow resistivity of the tested hemp fibres is used as input data for theoretical sound absorption calculations based on the Delany, Bazley, and Miki model.

2.2. Theoretical Methodology for Sound Absorption of Hemp Fibre Based on Delany, Bazley, and Miki Model

In order to predict the sound absorption properties of hemp fibre at various frequencies, and especially at higher frequencies than those obtained by interferometer testing, a theoretical study is being conducted based on the theoretical calculations of Delany-Bazley and Miki [

28], which indicate that knowing the static airflow resistivity of the material, it is possible to predict the sound absorption of the hemp fibre under study.

Specific airflow resistance (

Rs) of the material is calculated using the following formula [

28]:

where

ρ0 is the air density (kg/m

3),

c0 is the speed of sound in air (m/s),

f is the frequency (Hz), and

σ is the airflow resistivity (Pa·s/m

2).

Next, the complex wavenumber (

k) in the material is calculated [

28]:

where

ω is the angular frequency (rad/s).

The acoustic impedance (

Zs) of the material at the boundary in a multilayer system is calculated using the improved Miki model, which operates more accurately over a wide frequency spectrum. Sound propagation is described by [

28]:

where

Zs is the surface impedance (Pa·s/m),

Zc is the characteristic impedance (Pa·s/m),

k is the complex wavenumber (rad/m), and

d is the material thickness (m).

The reflection coefficient (

R) of the material is calculated based on the relationship between the reflection coefficient and the acoustic impedance of the material [

28]:

Knowing the reflection coefficient (

R), the theoretical sound absorption coefficient (α) is calculated [

28]:

To determine the overall accuracy level of the prediction model, the calculated results are compared with the measurements obtained by the interferometer. The accuracy is calculated according to the following formula:

where

experimentalf—sound absorption coefficient obtained by the measurements;

predictedf—sound absorption coefficient obtained by the prediction model; and

n—number of results.

Sound absorption of the following types of hemp fibres was predicted: bleached (BHF), cottonized (CHF), boiled cottonized (BCHF), well-stripped decorticated (DWSHF), and short, not combed fibres decorated (DSNCHF). The density of the fibre samples tested ranged from 50 kg/m3 to 250 kg/m3 with an interval of 50 kg/m3, and the thickness was 20 mm. The sound absorption was calculated in the frequency range from 160 Hz to 20,000 Hz.

The average of the sound absorption results of 3 measurements determined by experimental studies is presented in graphs in the 1/3 octave frequency band from 160 to 5000 Hz.

2.3. Methodology for Determining the Sound Transmission Loss in Hemp Fibre Using an Interferometer

In order to analyze the ability of hemp fibres of different types, thicknesses, and densities to reduce sound transmission, i.e., to determine sound insulation, the determination of sound transmission loss in the material is performed using an interferometer. Sound transmission loss in the material essentially depends on the density and static airflow resistivity of the test sample. The higher the density and airflow resistivity of the material, the lower the sound transmission in the material, which means increasing sound insulation. The experimental research method is called the four-microphone method: two microphones are installed in front of the test object, and the other two microphones are behind the test sample. Experimental measurements are performed based on the ASTM E2611-17 standard “Standard test method for normal incidence determination of porous material acoustical properties based on the transfer matrix method” [

29]. A four-microphone and single-load system is illustrated in

Figure 4.

The equipment used during the experiments consisted of the following: AED AcoustiTube (30 mm diameter) (Gesellschaft für Akustikforschung Dresden, Dresden, Germany); Microphones (free-field, ¼ inch diameter, with 3 or 4 used simultaneously)—Microtech Gefell Type M370 (Microtech Gefell, Gefell, Germany); Sound card—Sinus Apollo Lite (Sinus Messtechnik, Leipzig, Germany); Sound source (integrated into the tube); Software—AED AcoustiStudio (Gesellschaft für Akustikforschung Dresden, Dresden, Germany); Audio amplifier—Atlas Sound PA 601 (Atlas Sound L.P., Ennis, TX, USA); and additional equipment including an Acoustic Calibrator—Larson Davis CAL 200 (PCB Piezotronics, Inc. (Larson Davis division), Depew, NY, USA).

The entire testing procedure and the formulas used to obtain the sound transmission loss results are described in the ASTM E2611-17 standard: “Standard Test Method for Normal Incidence Determination of Porous Material Acoustical Properties Based on the Transfer Matrix Method” [

29].

The sound transmission loss (TL) is calculated using the following formula:

where

τ is the sound transmission coefficient.

The

Section 3 presents the average of the results. During the experimental sound transmission loss tests, all five types of fibres were examined. Their densities ranged from 50 kg/m

3 to 250 kg/m

3 with a step of 50 kg/m

3, and the thickness of each fibre sample was 20 mm, 40 mm, and 60 mm. The sound transmission loss was analyzed in the frequency range from 160 to 5000 Hz.

3. Results

3.1. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) Results

The results of the SEM study are presented in

Figure 5. SEM images of BHF show a smooth and clean surface with neatly arranged fibre filaments. Fibre bleaching effectively removes non-cellulosic components such as lignin and cellulose, resulting in a purer structure. The fibres are straight, without surface impurities. The fibre thickness of the bleached fibre ranges from 6.57 µm to 53.7 µm. In the SEM images of DWSHF fibre, we see that the thickness of the filaments of this fibre is significantly greater than that of BHF, from 21.9 µm to 235 µm. It is noticeable that the filaments are stuck together, and the surface is rough. A similar trend is seen when studying DSNCHF—here, the thickness of the filaments varies from 6.11 µm to 212 µm. Most of the filaments are also stuck together, many impurities are visible, and the surface is rough. The SEM results of CHF and BCHF are similar to BHF—the surface of the fibres is smooth, without roughness, and with a small amount of impurities. The thickness of the filaments in the case of CHF ranges from 7.34 µm to 60.9 µm, and in the case of BCHF, from 7.01 µm to 128 µm. The SEM images show very clean, well-separated fibres. Cooking helps to remove even more impurities, so the fibres become smoother, and the surface roughness decreases. Cottonization of fibres significantly reduces the diameter of the fibre filament. Cottonized fibres become more distinct.

When studying different types of hemp fibres using SEM, their morphological properties and thickness were determined. It was observed that depending on the fibre processing method, surface roughness, unevenness, and the amount of impurities become apparent, which affect the porosity of the fibre. It was noted that boiled and cottonized fibres have a smoother surface structure and a smaller diameter. All these properties increase the surface area interacting with sound waves, which improves the sound absorption of the fibres. In addition, a smaller diameter and a smoother surface allow the fibres to better isolate sound when they are compressed—the fibres fit more tightly to each other, their airflow resistance increases, which improves the insulating properties.

3.2. Hemp Fibre Static Airflow Resistivity Results

During the static air resistivity study, the following hemp types were examined: bleached (BHF), cottonized (CHF), boiled cottonized (BCHF), well-stripped decorticated fibre (DWSHF), and short, not combed decorticated fibre (DSNCHF). In order to assess the dependence of the airflow resistivity of individual fibres on the density of the fibres under study, it was changed from 50 kg/m

3 to 250 kg/m

3 in the interval of 50 kg/m

3. When conducting a static airflow resistivity study, the airflow resistance depends on the fibre diameter and material density, but the resistance remains constant with changing the thickness of the material under study, if the density is constant [

31]. The results obtained during the experimental study are presented below (

Table 1).

It was found that in all cases, static airflow resistivity increases with increasing fibre density. It can be stated that the increase in resistance is exponential. The highest airflow resistivity was determined for the BCHF sample (both 50 kg/m3 and higher density), where it ranged from 62.0 to 539.2 kPa∙s/m2. This is because the fibres of this type of hemp fibre have a smaller diameter, so they lie close to each other, which reduces porosity and increases airflow resistance.

It was found that the airflow resistivity of BHFs and CHFs is essentially similar and varies from 23.5 to 283.5 kPa∙s/m2 and from 17.3 to 253.3 kPa∙s/m2, respectively, with increasing density. DSNCHF and DWSHF have a significantly thicker fibre diameter; therefore, the airflow resistivity of these samples decreases, but with increasing density, the airflow resistivity also increases, and the results range from 6.5 to 95.2 kPa∙s/m2 and from 11.3 to 179.7 kPa∙s/m2, respectively.

3.3. Results of the Theoretical Analysis of Hemp Fibre Sound Absorption

In order to predict the sound absorption properties of hemp fibre at various frequencies, and especially at higher frequencies than those obtained by impedance testing, a theoretical study was conducted. The theoretical study was conducted based on the theoretical calculations proposed by Delany, Bazley, and Miki. The airflow resistivity of hemp fibres of different densities and types, determined during experimental studies, was used as the main input parameter for predicting the sound absorption properties of hemp fibre.

During the theoretical study, the sound absorption of the BHF, BCHF, CHF, DSNCHF, and DWSHF was predicted. The fibre density of the tested samples varied from 50 kg/m

3 to 250 kg/m

3, and the thickness reached 20 mm. Sound absorption was analyzed in the frequency range from 160 to 20,000 Hz. In order to compare the results of the theoretical study with the results of measurements, the sound absorption results obtained by the interferometer are also included in the result graphs. The results of the experimental study of sound absorption were previously presented in the study [

18]. The results of the theoretical study of the BHF are presented in

Figure 6.

Based on the results of the theoretical study of BHF, we see that with increasing fibre density, sound absorption increases in the low-frequency range (from 50 Hz to 500 Hz), but decreases in the medium (from 630 to 2000 Hz) and high-frequency range (from 2500 to 5000 Hz). The same trends are observed when analyzing the data obtained from experimental measurements. The data of the theoretical study show that the peaks of sound absorption are achieved when studying fibres with a density of 50 and 100 kg/m3, where at frequencies of 3150 Hz and 4000 Hz the sound absorption coefficient reaches 0.98 and 0.92. During experimental studies, peaks were determined at the same frequencies. Comparing the results obtained from the theoretical study and the sound absorption values determined by experimental measurements, we see that the measured steam absorption in the medium and high frequency range, when testing samples with densities ranging from 150 to 250 kg/m3, is better than predicted. For example, theoretically at 2500 Hz, the absorption of a fibre with a density of 200 kg/m3 reaches 0.64, while the value determined by experimental tests is 0.85, which is 24.7% less. Above 5000 Hz, the sound absorption is theoretically good and ranges from 0.70 to 0.99. Based on the results obtained, it was determined that the most accurate results obtained during the theoretical study, when compared with the experimental ones, are determined when testing denser fibres, since there is less discrepancy in the low frequency range. The average discrepancy over the entire frequency range (160–5000 Hz) ranged from 14.3 to 39.5%. This discrepancy is because the model does not consider the mass, porosity, and curvature of the material, so the accuracy of the theoretical model at lower frequencies is poorer.

Figure 7 presents the results of the theoretical study of the sound absorption of BCHF and their comparison with the experimentally determined results. We see that, as with the BHF, the sound absorption trends of BCHF are similar—with increasing fibre density, sound absorption increases in the low frequency range (from 50 Hz to 500 Hz), but decreases in the medium (from 630 to 2000 Hz) and high frequency ranges (from 2500 to 5000 Hz). Increased density increases the resistance to airflow; therefore, due to greater surface friction, sound absorption properties improve. The results are similar because these fibres are essentially similar in structure and fibre diameter. The theoretical study data show that the peak of sound absorption is achieved when studying BCHF with a density of 50 kg/m

3, where, at a frequency of 3150 Hz, the sound absorption coefficient reaches 0.95. During experimental studies, the highest sound absorption was determined at the same frequencies. It is observed that the experimentally determined vapour absorption in the medium and high frequency range, when testing samples with densities ranging from 100 to 250 kg/m

3, is better than predicted. The most accurate results obtained during the theoretical study, when compared with the experimental ones, are determined when testing denser fibres, since there is less discrepancy in the low frequency range. The average discrepancy of the BCHF theoretical study results in the entire frequency band (160–5000 Hz) ranged from 13.6 to 35.0%. This discrepancy is due to the fact that when using the Delany, Bazley, and Miki theoretical model, there is only one input parameter—the airflow resistivity of the fibre.

Analyzing the results of the theoretical study of CHF (

Figure 8), we see that the sound absorption trends remain similar—sound absorption increases with increasing density, and at the same time, airflow resistivity. The determined sound absorption of CHF, as well as BHF, BCHF, is similar in the entire frequency band due to the structural properties of the fibre. The sound absorption peak is achieved when testing CHF with a density of 50 and 100 kg/m

3, where at 3150 Hz and 4000 Hz, the sound absorption coefficient reaches 0.89 and 0.94. During experimental studies, sound absorption peaks were determined in the same frequency ranges, and the experimentally determined steam absorption in the medium and high frequency range, when testing samples with a density of 100 to 250 kg/m

3, is better than predicted in the theoretical study. The average discrepancy between the results of the CHF theoretical study and the experimentally determined results, in the entire frequency band (160–5000 Hz), ranges from 17.2% (when studying the sound absorption of a 250 kg/m

3 fibre) to 40.4% (when studying the sound absorption of a 50 kg/m

3 fibre). This discrepancy occurs because non-acoustic parameters of the fibre, such as the mass of the material, porosity, and fibre curvature, are not considered. From the obtained results, we can also see that the Delany, Bazley, and Miki theoretical model is more suitable for predicting denser fibres.

Figure 9 presents the results of the theoretical study of the sound absorption of DSNCHF and its comparison with the experimentally determined results. It is worth noting that the airflow resistivity of this fibre, as well as the DWSHF, is significantly lower than that of the previously studied fibres, since the fibres of this type of fibre are thicker and, as a result, the porosity of the material increases. We see that during the theoretical study, the sound absorption peaks are reached at frequencies of 3150, 4000, and 5000 Hz. The highest sound absorption in the entire frequency band is predicted when studying a fibre with a density of 150 kg/m

3, while a DSNCHF with a density of 50 kg/m

3 does not have good sound absorption properties and reaches up to 0.50 at a frequency of 5000 Hz, and at low frequencies, the sound absorption is insignificant in all cases. The sound absorption of low and medium frequencies decreases, since the DSNCHF has a larger fibre diameter, and at the same time, a higher porosity and air permeability of the material. Comparing the results of the theoretical study with the experimentally determined ones, we see that when studying the fibre with a density of 50, 100, and 150 kg/m

3, the predicted sound absorption results are higher than those determined by measurements, but peaks are observed at the same frequencies. The average discrepancy between the theoretical study results of DSNCHF in the entire frequency band (160–5000 Hz) ranged from 22.5 to 60.4%.

When evaluating the results of the theoretical study of sound absorption of DWSHF (

Figure 10), we see that they are very similar to the previously described DSNCHF results, since the structure of the fibres is very similar. We see that during the theoretical study, sound absorption peaks are reached at frequencies of 3150, 4000, and 5000 Hz, depending on the tested density. The highest sound absorption in the entire frequency band is predicted when testing a fibre with a density of 100 and 150 kg/m

3. At low frequencies, sound absorption is not significant in all cases. Sound absorption at low frequencies and medium frequencies decreases, since DWSHF, like DSNCHF, is characterized by a larger fibre diameter, and at the same time, a higher porosity and air permeability of the material. Comparing the results of the theoretical study with the experimentally determined ones, we see that when studying the fibre with a density of 50, 100, and 150 kg/m

3, the predicted sound absorption results are higher than those determined by measurements, but the peaks are observed at the same frequencies. The average discrepancy between the theoretical study results and the DWSHF in the entire frequency band (160–5000 Hz) ranged from 21.1 to 52.1%.

The experimental theoretical study determined the sound absorption coefficient of hemp fibre, which mainly depends on the fibre and type under consideration. Such dependence can be explained by the resistance of airflow and the scattering of sound waves when the wave passes through the fibre. At lower density, there is also a lot of fibre and fibre porosity. Higher fibre porosity allows sound waves to penetrate deeper into the fibrous material, which can result in increased viscosity and heat loss. These phenomena are always observed when examining the sound absorption of lower-density fibres in the medium and high frequency range, and especially less processed coarser fibres (DSNCHF and DWSHF).

Based on the sound absorption results obtained during the experimental and theoretical study, it is found that as the density of the fibres increases, the airflow resistance also increases, which increases the sound absorption at low frequencies. This happens because increasing the fibre density also increases friction losses, but at the same time, the absorption efficiency at higher frequencies decreases.

According to the SEM studies, we see that thinner, more processed fibres have a smoother surface and a lower amount of impurities, which affects the greater integrity of the material. Such fibres include BCHF and CHF. Due to the greater integrity of these fibres, the interaction of the sound wave with the surface increases, which also increases the sound absorption properties of the fibres, compared to coarser fibres (DSNCHF and DWSHF).

The discrepancies between theoretical and experimental results arise because the DBM model only considers airflow resistance and thickness, while real fibres exhibit additional scattering mechanisms related to porosity, fibre bending, and mass distribution.

3.4. Results of the Hemp Fibre Sound Transmission Loss

In order to determine the insulating properties of hemp fibres of different types, thicknesses, and densities, sound transmission through the material was measured using an interferometer.

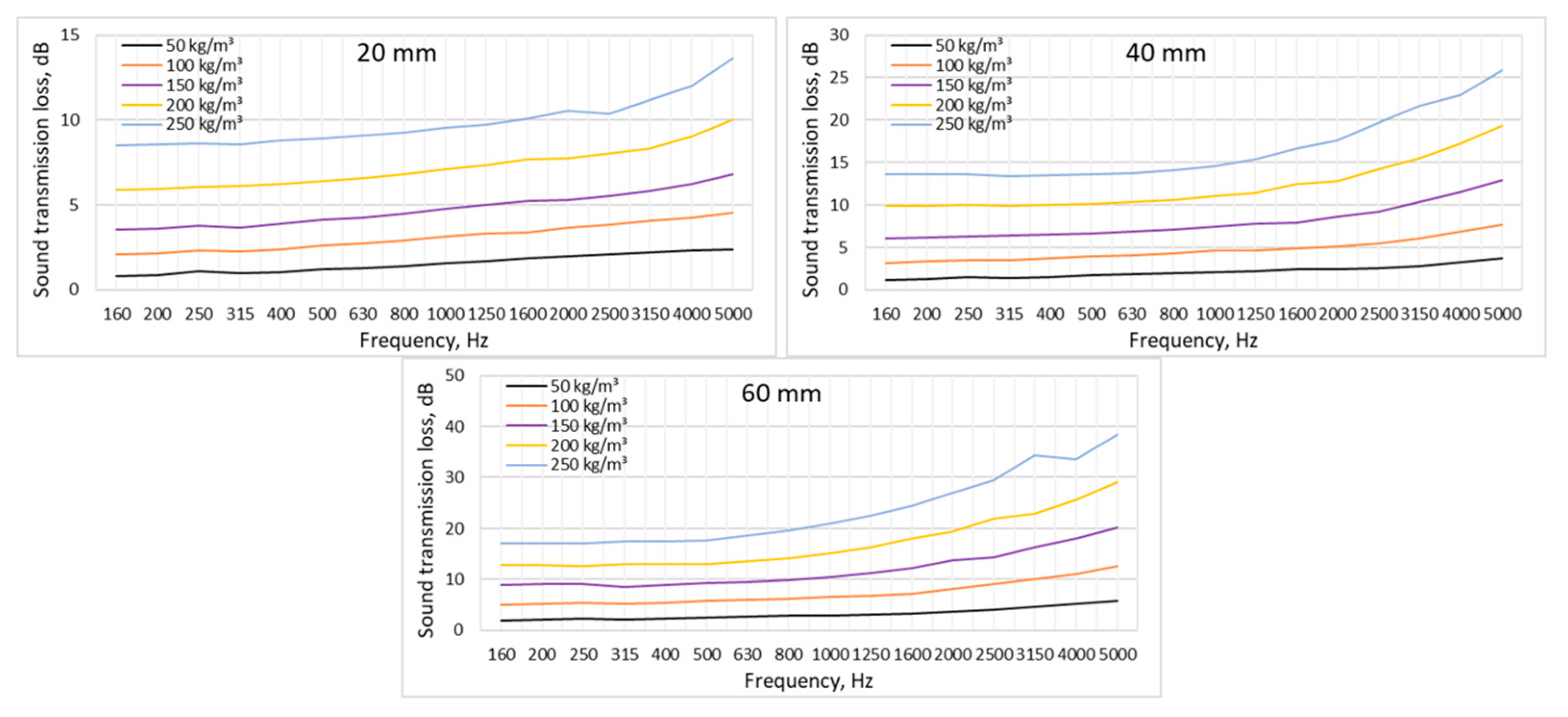

Analyzing the graphs in

Figure 11, we see that the maximum sound transmission loss of BHF in 20, 40, and 60 mm thick fibre is recorded at a density of 250 kg/m

3. The sound transmission loss (DTL) of BHF 20 mm in the entire frequency band (from 160 to 5000 Hz) varies from 16.25 dB to 25.28 dB for a fibre with a density of 250 kg/m

3.

The sound transmission loss (DTL) of BHF 40 mm in the entire frequency band varies from 21.04 dB to 43.40 dB for a fibre with a density of 250 kg/m3, and the sound transmission loss of BHF 60 mm in the entire frequency band varies from 23.78 dB to 58.63 dB for the same fibre density.

From the evaluation of the BCHF sound transmission loss results presented in

Figure 12, we see that the maximum sound transmission loss is recorded at a density of 250 kg/m

3. In the frequency band from 160 to 5000 Hz for a 20 mm thick BCHF, the sound transmission loss ranges from 21.9 to 36.24 dB. The maximum sound transmission loss is determined in the 5000 Hz band. When studying BCHF 40 mm, it was determined that the transmission sound transmission loss of a 250 kg/m

3 density fibre ranges from 27.09 to 51.88 dB, the maximum value is recorded at a frequency of 2500 Hz, and then, as the frequency increases, the sound transmission loss decreases until the threshold drops to 32.22 dB at 3150 Hz. At a frequency of 5000 Hz, the value reaches 44.07 dB. In contrast to the 250 kg/m3 density fibre, the sound transmission loss of the 200 kg/m

3 density fibre increases consistently and reaches from 22.8 to 51.28 dB in the entire analyzed frequency spectrum, without such a significant drop at the 2500 Hz limit. When evaluating the sound transmission loss results of BCHF 60 mm, an analogous situation is observed. The sound transmission loss of the 250 kg/m

3 density fibre in the entire frequency spectrum reaches from 31.74 to 57.47, the peak is reached at 2500 Hz, and a drop is observed again. The sound transmission loss of the 200 kg/m

3 density fibre increases consistently up to 2500 Hz, where a drop is also observed, but at 5000 the sound transmission loss value of 59.67 dB is reached. In the entire analyzed frequency spectrum, the sound transmission loss of a fibre with a density of 200 kg/m

3 ranges from 25.78 to 59.67 dB.

From the graphs presented in

Figure 13, we see that, in principle, the trend of the results, comparing the results of the CHF with the previously described results, is the same. The higher the fibre density, the higher the sound transmission loss (DTL) in the entire frequency band. The maximum sound transmission loss in samples with a thickness of 20, 40, and 60 mm is always recorded at a density of 250 kg/m

3, and in the frequency band from 160 to 5000 Hz, it reaches from 15.5 to 23.6 dB, from 20.13 to 40.60 dB, and from 23.65 to 54.14 dB, respectively. The maximum sound transmission loss values in all cases are determined in the high frequency spectrum from 2000 to 5000 Hz.

Based on the results presented in

Figure 14, it is clear that DSNCHF does not have good insulating properties. The maximum sound transmission loss in 20, 40, and 60 mm thick fibres is always recorded at a density of 250 kg/m

3, and in the frequency band from 160 to 5000 Hz, it reaches from 6.79 to 10.31 dB, from 10.03 to 18.57 dB, and from 11.71 to 25.11 dB, respectively. The maximum sound transmission loss values are determined in all cases in the high-frequency spectrum at 5000 Hz. The higher the density of the DSNCHF, the higher the sound transmission loss (DTL) in the entire frequency band.

The results of the sound transmission loss of DWSHF 20 mm in the material (

Figure 15) show that the trend remains the same as in the previously described results, and the highest sound transmission loss values are determined in the 250 kg/m

3 density fibre, where they range from 8.50 to 13.64 dB in the entire frequency spectrum (160–5000 Hz). For 40 mm thick DWSHF, in the frequency band from 160 to 5000 Hz, the sound transmission loss reaches from 13.68 to 25.82 dB.

When evaluating the sound transmission loss results of DWSHF 60 mm, an analogous situation is observed. The sound transmission loss of 250 kg/m3 density fibre in the entire frequency spectrum reaches from 17.09 to 38.42, and the peak is reached at 5000 Hz. The highest sound transmission loss values are determined in the high frequency spectrum from 2000 to 5000 Hz.

Considering the obtained results, it can be stated that the increase in sound transmission losses is determined by the mass and airflow resistance. In all cases, increasing the thickness and density of the hemp fibre sample leads to sound attenuation, especially in the high-frequency range. This is due to the formation of a longer sound wave propagation path and greater resistance to particle movement. Smaller-diameter BCHFs and CHFs at high density have much higher sound attenuation than larger-diameter and -porosity DSNCHFs and DWSHFs.

4. Discussion

When studying different types of hemp fibres using a Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM), the morphological properties of the fibres and the thickness of the fibres were determined. We can see that, depending on the method of processing the fibre, the roughness, unevenness, and the number of impurities on the fibre surface appear, which affect the porosity of the fibre. It was observed that boiled and cottonized fibres have a smoother surface structure and a smaller diameter. All these properties increase the surface area interacting with the sound wave, which improves the sound absorption of the fibres. And the smaller diameter of the fibres and their smoother surface allow for greater sound insulation properties when the fibre is compacted, since the fibres lie closer to each other and their airflow resistivity increases, which increases insulation. The morphological properties of hemp fibres ensure greater interaction between sound waves and the fibre material, which results in better acoustic performance. Similar studies have been conducted by other scientists, such as [

8] found that the random surface and internal pores of hemp fibre waste improve sound absorption, especially in the high frequency range. Ref. [

32] demonstrated how the secondary formation of the hemp fibre cell wall forms a layered structure that can improve acoustic attenuation. Study describes the formation of several different layers in the secondary cell wall of hemp phloem fibres, including thicker secondary wall layers and additional layers such as the tertiary (gelatinous) wall. The multi-layered architecture of the cell wall changes the mechanical and structural properties of the fibres, which can affect energy dissipation and attenuation mechanisms in acoustic domains [

32]. Ref. [

8] also emphasized that the good acoustic properties of hemp fibre are influenced by the porosity and surface roughness of the hemp fibre. The uneven surface (gaps, cracks, and surface roughness) and internal pore structure from the waste hemp fibre increase the surface area and create interconnected pores that improve acoustic energy dissipation and contribute to good sound absorption. The morphological acoustic properties of hemp fibres, depending on the type of processing, have a significant impact on the acoustic properties of the fibre. The larger surface area and internal porosity ensure better dissipation of sound wave energy, thus improving the sound absorption of hemp fibre. The smaller fibre thickness and its smoother surface directly affect the airflow resistivity, which increases sound insulation properties.

The static airflow resistivity of hemp fibres of different densities determined in this work can be described as average. There is a direct relationship between the static airflow resistivity of the fibre and sound absorption. As the static airflow resistivity increases, sound absorption begins to decrease, but the insulating properties of hemp fibres increase. Sound absorption efficiency is directly proportional to airflow resistance. Ref. [

16] confirms that the airflow resistivity values of natural fibre composites strongly affect insulation. It is also observed that the smaller fibre thickness and its smoother surface directly affect airflow resistivity, which increases sound insulation properties.

The airflow resistivity values determined for different hemp fibres in this work ranged from 6.5 to 23.5 kPa∙s/m2 for fibres with a density of 50 kg/m3, from 19.3 to 153.2 kPa∙s/m2 for fibres with a density of 100 kg/m3, from 38.8 to 176.5 kPa∙s/m2 for fibres with a density of 150 kg/m3, from 70.7 to 374.2 kPa∙s/m2 for fibres with a density of 200 kg/m3, and from 95.2 to 539.2 kPa∙s/m2 for fibres with a density of 250 kg/m3. The highest airflow resistivity was determined for the most processed fibre types, BCHF, CHF, and BHF, respectively. This can be explained by looking at the SEM results. We see that boiled and cottonized fibres have lower roughness, smaller diameter, unevenness, and the number of impurities on the fibre, which affects the porosity of the fibre and greater homogeneity of the material when compacted, which increases airflow resistivity. Less processed DSNCHF and DWSHF, with a larger diameter of the fibre, a larger roughness, and the number of impurities, have lower airflow resistivity, because the thicker fibres do not compress when compacted, leaving a larger air gap between them, increasing porosity.

Theoretical studies of the sound absorption of hemp fibres have shown that hemp fibre samples have high sound absorption coefficients (up to 0.99), especially in the high and medium frequency range. This is due to the fibrous nature of hemp and its porosity, which allows for the dissipation of acoustic energy. The theoretical absorption peaks in the frequency range from 160 to 5000 Hz were observed at 3150 and 4000 Hz, where they ranged from 0.94 to 0.99. The results were in agreement with the experimental sound absorption values, but the theoretical absorption peak shifted slightly at higher frequencies. For example, the BHF and DWSHF peaks were measured at 3150 Hz, and the theoretical peak was at 4000 Hz. The DSNCHF peaks were measured at 2500 Hz, and the theoretical peaks were at 3150 and 4000 Hz. It is also noticeable that in theoretical studies of boiled and cottonized fibres, sound absorption peaks were determined when testing fibres with a lower density of 50 kg/m

3, while the peaks determined by measurements were when testing fibres with a density of 100 kg/m

3. In general, when evaluating the types of hemp fibres studied, similar results were presented in [

16], where it was found that the sound absorption coefficients of combed hemp fibres increase with increasing bulk density and thickness, reaching 0.99 at some frequencies. The highest absorption was measured for hemp materials at 2000 Hz, with a sound absorption coefficient of 0.99 [

31], and it described how optimal thickness and density can improve the sound absorption properties of hemp fibre composites, showing that higher thickness and bulk density of hemp fibre composites correlate with better acoustic energy dissipation and higher sound absorption coefficients.

Table 2 presents the summarized results of theoretical research and measurements of sound absorption in a frequency range from 160 to 5000 Hz.

When assessing the suitability of the Delany, Bazley, and Miki theoretical model for assessing the sound absorption of hemp fibres, it can be concluded that it can generally predict the main sound absorption trends and peaks, especially when evaluating lower-density fibres, while overall model accuracy increases and model reliability decreases for higher-density fibres. When evaluating the results of the theoretical study of all hemp fibres, it was found that the average discrepancy over the entire frequency range (160–5000 Hz) ranged from 14.3 to 60.4%. The largest discrepancy was found when comparing the sound absorption results in the low and high frequency ranges, especially when studying higher-density boiled and cottonized fibres, which were characterized by significantly higher airflow resistivity. Calculations were performed to verify the DBM model validity range (0.01 < f/σ < 1.0) for each fibre type and density. It was found that the DBM model validity range, when evaluating sound absorption in the frequency range from 160 Hz to 5000 Hz, is fully satisfied only when studying 50 kg/m

3 CHF (except 160 Hz), 50 kg/m

3 DSNCHF, and 100 kg/m

3 DSNCHF (except 160 Hz) and 50 kg/m

3 DWSHF. All other fibres, due to too high airflow resistivity, did not satisfy the DBM model validity range (0.01 < f/σ < 1.0) or did not satisfy it in the entire evaluated frequency range. The airflow resistivity values satisfying the DBM model validity range (0.01 < f/σ < 1.0) in the frequency range from 160 to 5000 Hz are presented in

Table 3. According to the table, in order to use the DBM model to predict the sound absorption of hemp fibre over the entire frequency range of 160—5000 Hz, airflow resistivity (σ) values must be between 5.00 and 16.0 kPa·s/m

2.

It is also worth noting that the discrepancy may be due to the fact that the BDM model does not consider the mass, porosity, and curvature of the material, so the accuracy of the theoretical model at lower frequencies is poorer. This overall model accuracy is affected by the fact that the main input parameter is only the airflow resistivity and the thickness of the sample. In general, it can be said that the Delany, Bazley, and Miki theoretical model, although suitable for studying fibrous and porous materials, was not suitable in this case due to the high density of the fibres studied and their high airflow resistivity. For more reliable results, models that estimate the tortuosity, porosity, and viscosity of the material, for example, the Johnson–Champoux–Allard (JCA) model, could be used [

33,

34,

35].

The results of experimental measurements performed with an impedance tube show that various types of hemp fibres can effectively attenuate sound, especially at higher material densities and thicknesses.

Table 4 presents the summarized highest achieved results of sound transmission loss measurements in the frequency range from 160 to 5000 Hz.

Boiled and cottonized fibres, which have a smoother surface structure and smaller diameters, are most suitable for sound attenuation. The smaller fibre diameter and smoother surface allow for greater sound insulation properties when the fibre is compacted, as the fibres lie closer to each other and their airflow resistivity increases, which increases insulation. In all cases, when studying hemp fibres of different types, different densities, and different sample thicknesses, a direct dependence on the density and thickness of the fibre sample was found. Increasing the density and thickness of the fibre samples increases the sound transmission loss in the entire frequency range, and especially in the medium and high frequency range from 1600 to 5000 Hz. Sound transmission loss increases with increasing material thickness and mass, since the interaction between the material and the sound wave increases, and more energy is converted into heat. The highest sound transmission loss values were determined when testing boiled and cottonized fibres (CHF, BCHF, and BHF), as they were characterized by higher air resistance compared to DSNCHF and DWSHF. BCHF sound transmission loss at 5000 Hz can reach up to 59.67 dB, using a 60 mm sample of 200 kg/m3 density fibre. Less technologically processed fibres DSNCHF and DWSHF, which have low air resistance, did not exhibit high sound transmission loss either when the sample thickness was increased to 60 mm or when the fibre density was increased to 250 kg/m3. The values reached up to 38.42 dB.

Although hemp fibres insulate sound best in the high frequency range, at 2000–3150 Hz, when testing higher-density fibres of 200–250 kg/m

3, a sudden, unpredictable drop in sound transmission loss is observed, which is especially evident when testing BCHF and CHF, which showed the highest values. For example, when testing a CHF 60 mm and 250 kg/m

3 sample, the sound transmission loss at 2500 Hz reached 48.07 dB and at 3150 Hz it dropped to 39.55 dB, and when testing a BCHF 40 mm and 250 kg/m

3 sample, the sound transmission loss at 2500 Hz reached 51.88 dB and at 3150 Hz it dropped to 32.22 dB. The method of forming the hemp fibre sample could have influenced the transmission loss drop at the frequencies under consideration. Manually filling the higher-density fibre into the mould intended for measurements could have resulted in an uneven fibre distribution and a layered structure with different acoustic impedance. Such layering creates conditions for internal resonant phenomena in the sample volume, which can lead to a reduction in sound transmission losses in a certain frequency range. In layered acoustic systems, mass–air–mass resonances can produce distinct minima in transmission loss at certain frequencies, even under normal-incidence conditions. The results of mass–air–mass resonances have been described and confirmed in [

36,

37,

38]. Also, this transmission loss at frequencies 2500 Hz and 3150 Hz can be explained by the resonant phenomena caused by the sample edge constraint in the sample. This problem was described in [

39] when studying the sound transmission loss of melamine foam in an impedance tube. Although the sound transmission loss of a porous material should increase gradually with increasing frequency, a resonant minimum was found at 1800 Hz. It was emphasized that as the flow resistance and bulk density of the material increase, the resonances shift to higher frequencies. For this reason, the sound transmission loss of high-density hemp fibres in the high-frequency ranges can suddenly decrease, although the general trend remains increasing [

39].

The research provides significant information on the acoustic properties of hemp fibres, also confirming their suitability as a sustainable material alternative for sound insulation and sound absorption. The hemp fibre types investigated in this study are a significant alternative to other sustainable materials such as sunflower, sugarcane bagasse, bamboo, grass, kenaf, and others, whose acoustic characteristics have been described at [

2,

3]. The fibres studied in our article were characterized by similar or better sound absorption in the mid- and high-frequency ranges, and the presented transmission loss values for different thicknesses, densities, and types of hemp fibres allow us to view hemp fibre not only as a sound-absorbing, but also as a sound-insulating material. Lower-density hemp fibres, depending on the situation and need, can be used for sound absorption in rooms or auditoriums, to improve room acoustics, as well as for installing partitions between rooms, instead of conventional materials such as stone or mineral wool. Given the high sound absorption and sound loss of denser fibres, these fibres can be used as a filler in closed perforated structures for sound reduction, such as sonic crystals or louvred noise barriers. Depending on the need, design features, and the sound emitted by the source, fibres with a density of 100–150 kg/m

3 should be used to absorb higher frequency sounds, and fibres with a density of 200–250 kg/m

3 should be used for lower frequencies. In all cases, thicker hemp fibre material of 40 and 60 mm thickness with a density of 200–250 kg/m

3 should be used for sound insulation. It is emphasized that the highest transmission loss is observed in more technologically processed boiled and cottonized fibres.

Although the investigated hemp fibre has good acoustic properties, future studies should evaluate parameters such as water and moisture resistance, weathering resistance, fire resistance, and biotic resistance, which are characteristic of conventional materials such as mineral or glass wool. To improve water and weathering resistance, treatments like alkali treatment, thermal modification, improved adhesives, silane treatment, or hot water extraction are performed. Chemical impregnants with phosphates, borates, and ionic liquids can be used to improve fire resistance. The biotic resistance of hemp fibres can be improved by using salicylic acid or natural monoterpene phenols [

2,

40,

41]. Depending on the materials and methods used to improve the resistance of hemp fibres, their acoustic properties may change, so the results presented in our work could be used for their comparison in future studies. Also, in order to further examine and emphasize the sustainability aspect, special attention should be focused on the life cycle assessment of the fibres studied in our work, where both hemp cultivation and different types of hemp fibre production technology would be examined. For this purpose, the information provided in the article [

42], which presents an LCA of mycelium-based composite acoustic insulation panels, could be used.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. The sound transmission loss and sound absorption measurements were performed using an interferometer under normal wave incidence conditions, which describe an idealized sound propagation; therefore, the obtained sound absorption and sound transmission loss results may differ from those that would be determined under diffuse sound field conditions under real conditions. Also, the acoustic properties of the studied fibres may change due to environmental factors, such as temperature and humidity, under real conditions. The study also does not assess the ageing processes of the studied fibre types, which may change the acoustic properties of the material due to biological effects or mechanical wear. It is also worth noting that the Delany–Bazley–Miki (DBM) model does not estimate the porosity, tortuosity, and other parameters of the material, which increases the discrepancies between theoretical and experimental results, indicating the need to apply more advanced porous material models, such as Johnson–Champoux–Allard, in the future.

5. Conclusions

In this study, the acoustic and physical properties of different types of hemp fibre were investigated. Using a theoretical study, based on the DBM theoretical model, the sound absorption of different types of hemp fibres was determined, and experimental studies determined the sound transmission reduction and static airflow resistivity of the fibres. The morphological properties of different fibres were also examined using SEM. During the experimental and theoretical studies, it was found that when the appropriate thickness and density are selected, hemp fibres have high efficiency in absorbing and insulating sound.

The highest sound absorption coefficients, 0.98–0.99, were determined for BHF, CHF, DSNCHF, and DWSHF. BHFs and CHFs absorb sound most effectively at a frequency of about 3150 Hz, when their density reaches about 100 kg/m3, which indicates high absorption in the medium and high frequency range. BCHF also has a high sound absorption of 0.95–0.96; the highest absorption peak is observed at a frequency of 3150 Hz. DSNCHF is distinguished by the fact that the highest sound absorption, α 0.99, is determined at a slightly lower frequency of 2500 Hz and at a higher density (200 kg/m3).. DWSHF reaches a maximum absorption coefficient, 0.99, at 3150 Hz, and theoretical results show high absorption also at about 4000 Hz. To summarize, it can be stated that all the hemp fibres studied absorb sound most effectively in the medium and high frequency range (about 2500–5000 Hz), and the highest absorption efficiency is achieved by BHF, CHF, DSNCHF, and DWSHF, depending on their density and structural properties.

Sound transmission loss results show that the highest values are achieved for fibres of greater thickness and density. The highest sound transmission loss is demonstrated by BCHFs, BHFs, and CHFs, whose 60 mm thick samples achieve up to 59 dB sound attenuation at 5000 Hz. BCHF stands out in particular, which, at a thickness of 60 mm and a density of 200 kg/m3, reaches the highest value—up to 59.67 dB. BHFs and CHFs also exhibit consistently increasing sound transmission loss with increasing thickness. Meanwhile, DSNCHFs and DWSHFs exhibit lower sound transmission loss even at a thickness of 60 mm; their values are noticeably lower up to 25–38 dB.

Of the fibre types studied, BCHF and CHF hemp fibres stood out with better acoustic properties, especially insulating ones, since the smoother surface structure of the fibres and the smaller diameter improve sound insulation. Experimental results showed that increasing the density of hemp fibres improves sound absorption in the low frequency range, but decreases in the medium and high frequency ranges. In addition, static airflow resistivity is a key parameter determining sound absorption properties—higher-density fibers generally exhibit better sound absorption. The study also confirmed that the theoretical model of Delany, Bazley, and Miki is suitable only for predicting sound absorption at low-density fibre. The accuracy of the model decreases with increasing fibre density, which requires more complex models that take into account additional parameters such as porosity and tortuosity.

The selection of hemp fibre types for practical applications should be based on the desired acoustic properties, as each fibre type has unique sound absorption and transmission loss characteristics. The results of this study confirm that natural hemp fibre can be a sustainable and environmentally friendly alternative to conventional sound-absorbing or insulating materials, which meet environmental goals and the requirements of the European Green Deal.

Future studies are planned to examine the effectiveness of hemp fibre in sound barriers.