1. Introduction

For a long time, climate governance has focused mainly on the production side. Many studies argue that the greenhouse effect driven by carbon emissions is primarily caused by production activities. This has often led to the neglect and underestimation of the ecological impacts of consumption-based carbon emissions [

1]. In fact, global warming is closely linked to consumers’ consumption activities [

2]. The United Nations Environment Programme’s Emissions Gap Report 2023 [

3] indicates that emissions attributable to household consumption contribute roughly two-thirds of total global carbon emissions. In contrast to production-oriented emissions, consumption-based carbon emissions are largely driven by the decisions and daily practices of vast numbers of households and individuals. They are typically small at the individual level, widely dispersed, and highly heterogeneous. Moreover, as living standards and consumption levels rise, these emissions continue to grow [

4]. Shifting consumption behaviors toward low-carbon patterns has the potential to cut emissions by approximately 40–70% over the coming three decades [

5]. These points suggest that a low-carbon transition in household consumption will be a major new source of momentum for the broader green transformation of the economy and society. The resolution adopted at the Third Plenary Session of the 20th CPC Central Committee underscored the need to strengthen incentive mechanisms that encourage green consumption. The 2025 Government Work Report [

6] further emphasized the need to “foster the development of environmentally sustainable, low-carbon patterns of production and everyday living” At present, China’s green consumption market is taking shape, but it still faces challenges such as the “easy to know, hard to do” gap among consumers and the problem that green products are “well received in principle but weak in actual sales.” How to turn green consumption from a socially promoted idea into a widely internalized and self-driven practice and how to build a multi-dimensional, coordinated, and incentive-compatible institutional system to drive a green and low-carbon transition across society have become core issues for advancing urban sustainability.

With the rising wave of a new round of scientific and technological innovation and industrial upgrading, the digital economy supported by next-generation network infrastructure, big data, artificial intelligence and platform-based business models has increasingly become the core driving force for China’s high-quality economic development [

7]. Even if the digital economy continues to release consumption dividends, it also creates and strengthens low-carbon dividends, providing a new technical foundation for the transformation to green consumption and sustainable urban development [

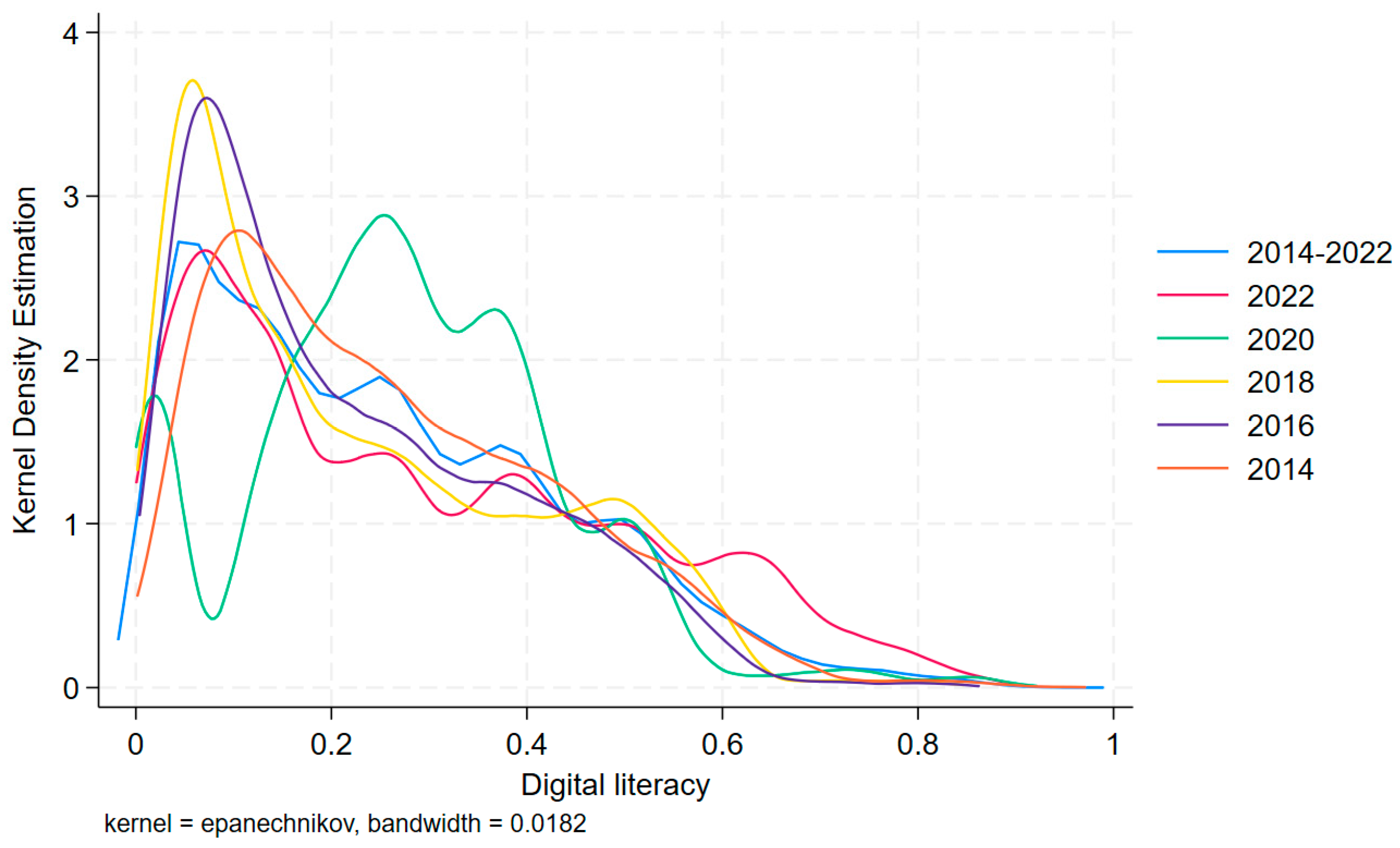

8]. By June 2025, the number of Internet users in China has increased to about 1.123 billion, and the national Internet penetration rate has reached about 80%. This shows that the digital economy is increasingly closely linked to the daily life of residents and the operation of urban governance. In this case, digital literacy has evolved into a series of basic abilities that enable individuals to acquire, understand, evaluate and generate information in a digital environment. It is increasingly regarded as the micro-foundation of consumer preferences, behavior patterns and environmental awareness [

9]. This study defines digital literacy as a multi-dimensional capability system covering six dimensions: acquisition of digital devices, online communication and sharing, use of digital scenarios, cognition of digital formats, acquisition of digital information and mobile payment. Its indicators include the use of the Internet and smart devices, the frequency of online social interaction and online consumption, and the subjective evaluation of respondents on the importance of digital tools in work, learning and daily life. Stronger digital literacy enables residents to use digital tools and information platforms more efficiently, thus alleviating the long-standing information asymmetry in the green product and service market. Moreover, greater transparency of environmental information, coupled with online public supervision, can promote residents to internalize green social norms and strengthen low-carbon values [

10].

Nevertheless, digital literacy does not affect the consumption carbon emissions of families in isolation. On the contrary, it is embedded in a specific regional socio-economic and policy environment. Uneven regional development will affect the coverage of digital infrastructure, the availability of green technologies, and the ability of households to pay. Access to clean energy directly restricts the decarbonization potential of household energy use. In addition, the strictness and design of local environmental policies will change the costs and benefits of behavioral change by changing incentives and constraints. These macro-level structural conditions can interact with digital literacy and jointly determine the way and effect of HCE. Thus, the analysis of the relationship between digital literacy and HCE should clearly take into account the differences caused by different external environments and constraints. In this study, digital literacy is defined as the core ability of residents to understand and apply digital technology. It aims to clarify how digital literacy can systematically affect HCE and urban emission reduction by enhancing environmental awareness and reshaping the consumption structure [

11]. This is of important practical significance and policy guidance for improving urban governance capabilities and strengthening the policy framework to support green consumption.

Digital literacy is not a one-way tool to reduce carbon emissions related to consumption. On the contrary, it is like a typical double-edged sword, with both “green promotion effect” and “high carbon induction effect” [

12]. High digital literacy improves the efficiency of information acquisition and the convenience of consumption. This may stimulate new consumer demand and expand digital consumption scenarios, thus increasing household energy use and carbon emissions. High digital literacy may enhance personal environmental awareness and willingness to buy green products. It can also promote the improvement in energy efficiency and the transition to low-carbon behavior [

13,

14]. This double impact means that the relationship between digital literacy and HCE is unlikely to be a simple linear relationship; on the contrary, it may present more complex and obviously nonlinear dynamic changes [

15]. Against this background, how does digital literacy affect the overall level of carbon emissions related to household consumption? What is the mechanism that drives this relationship? Answering these questions is crucial for building an urban low-carbon governance system based on digital capabilities and promoting the inclusive green transformation of cities. These problems still need to be studied systematically. Under the guidance of China’s dual-carbon goal, this study starts from the micro-level family perspective, focuses on the mechanism by which digital literacy affects family carbon emissions, and explores whether this relationship follows the inverted U-shaped model of increasing first and then decreasing. This study aims to find a feasible path for family energy conservation and emission reduction, while ensuring the continuous improvement in living standards. This provides new ideas for promoting the dual-carbon strategy and an empirical basis for the design of China’s energy conservation and emission reduction policy.

2. Literature Review and Hypothesis

As the key ability of individuals to obtain, understand and use information in the digital environment, digital literacy has an obvious nonlinear impact on family consumption related to carbon emissions [

16]. The relationship between digital literacy and consumption-based HCE is not linear, but shows an inverted U-shaped curve trend, that is, it rises at first and then begins to decline. This model can be explained from the perspective of the technological rebound effect. The theory points out that lower costs and greater convenience can stimulate the expansion of consumption in the early stages of technology or capacity improvement. This, in turn, increases energy use and carbon emissions. When digital literacy reaches a higher level, efficiency improvement and consumption structure optimization become more important, which in turn helps to curb carbon emissions. This process reflects how digital literacy shapes household consumption behavior and energy use patterns in different ways at different stages of development [

17]. In the initial stage of the development of digital literacy, the improvement in family digital capabilities is mainly achieved by broadening consumption channels and reducing barriers to transactions and use [

18]. Through algorithmic recommendation, e-commerce services and on-demand distribution, digital platforms can significantly increase the consumption demand of families in energy-intensive fields, such as electronic products, online entertainment and smart home devices [

19,

20]. In this process, although energy efficiency per unit of digital activity may be improved, the expansion of consumption and the stratification of energy use scenarios may lead to a small increase in HCE [

21]. Therefore, at this stage, digital literacy is mainly manifested as a form of “consumption empowerment”. It prompts families to shift from traditional consumption patterns to more digital, more frequent and more diversified consumption patterns, and the corresponding carbon emissions will also increase [

22].

However, once digital literacy reaches a key level, its development path will undergo a fundamental change. Families with high digital literacy no longer focus on expanding consumption scenarios, but have entered a green empowerment stage, which is characterized by deeper understanding and behavioral change. First of all, families can use technologies such as energy management systems and intelligent control devices more effectively to optimize their energy use structure. This enables dynamic monitoring and more accurate regulation of energy use. Secondly, high digital literacy enhances consumers’ ability to understand environmental issues and improves the efficiency of information acquisition. Therefore, they are more inclined to choose low-carbon products and services, participate in sharing economic activities, and reduce unnecessary digital consumption behavior. In addition, individuals with stronger digital literacy can use tools such as carbon footprint monitoring and green certification systems to guide emission reduction behavior in a more systematic and evidence-based manner. Therefore, once digital literacy reaches a high level, the impact of its increased emissions will gradually weaken, and eventually show a diminishing marginal effect [

23,

24]. This inverted U-shaped model highlights the dual role of digital literacy in the process of low-carbon transformation of the family. In the early stage, it played a role in promoting consumption expansion and rising energy demand. In the later stage, it has become a catalyst for improving energy efficiency and promoting more environmentally friendly consumption. Based on these, the following hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 1: Digital literacy and household consumption carbon emissions are non-linearly related in an “inverted U-shaped” manner.

As the core human capital of the digital age, digital literacy not only directly affects the consumption behavior of families, but also indirectly promotes the transformation to low-carbon consumption through a variety of intermediary channels, including perceived environmental pressure, social trust and income level [

25,

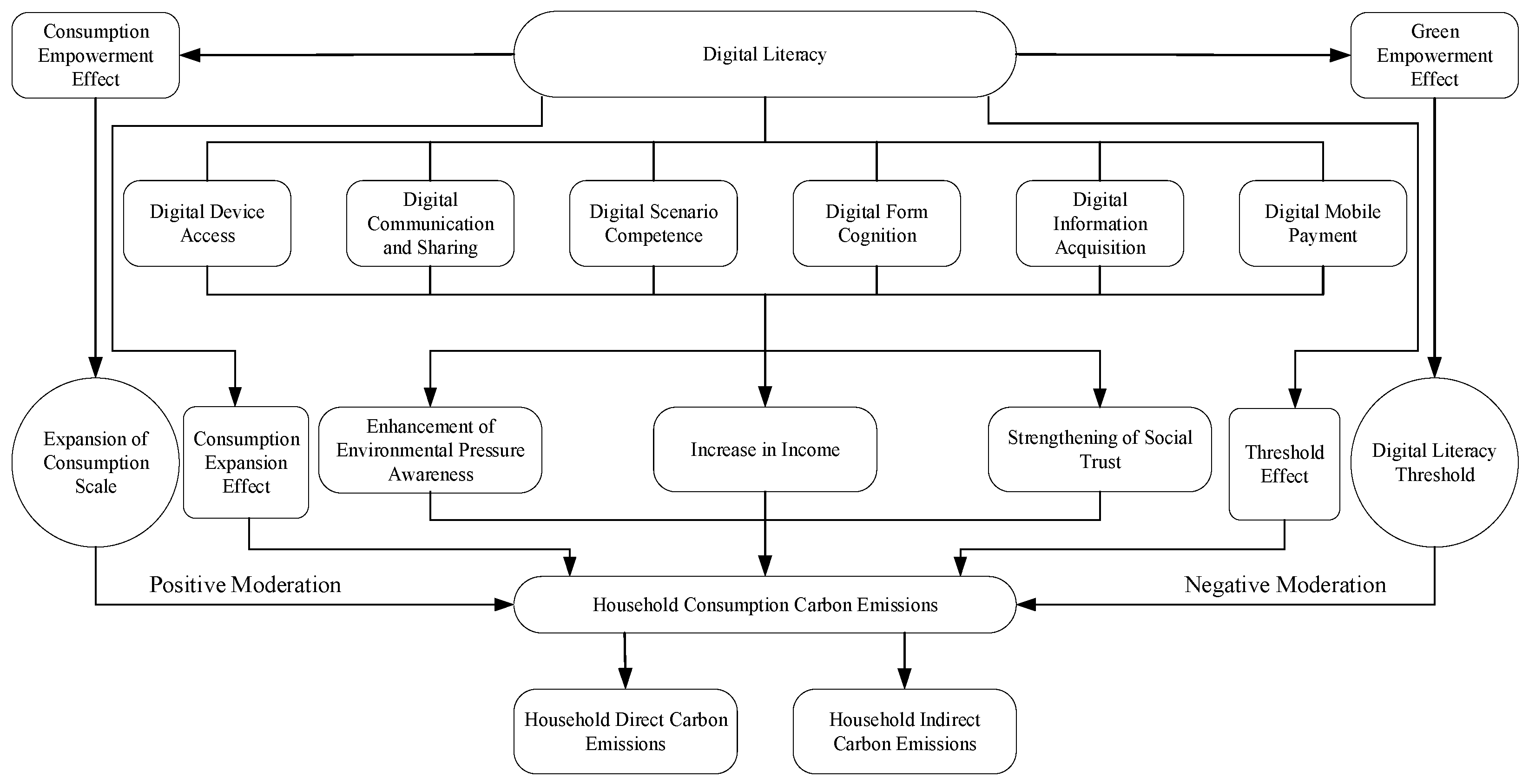

26]. As shown in

Figure 1, digital literacy can enhance residents’ perception of environmental pressure, thus providing intrinsic motivation for low-carbon consumption. Residents with high digital literacy can make more effective use of the Internet, social media and online scientific communication platforms. Therefore, they can obtain and understand complex information about environmental issues such as climate change, carbon footprint and resource shortage. This process is consistent with the risk perception theory [

27], which believes that subjective risk awareness is the key driver of behavior. Digital literacy enhances families’ perception of the possibility and severity of the environmental consequences of consumption, thus increasing their willingness to mitigate these risks. Therefore, through the mechanism described in the “Planned Behavior Theory”, a stronger sense of risk and environmental responsibility can be translated into practical action [

28]. Individuals have become more positive about low-carbon consumption. They also feel that there is a broader consensus on environmental protection. In addition, since they have the relevant information and skills, they are more confident that they can take effective action. These factors together promote the formation of a strong willingness to actively participate in low-carbon consumption. This encourages families to take the initiative to adjust the consumption structure. They reduce the use of high-carbon products and services and increase the choice of green, recycled and low-carbon goods. As a result, the consumption model has changed from expanding quantity to improving quality.

Secondly, the theory of social capital believes that trust, norms and social networks are key resources to support cooperation and collective action. Social trust can reduce transaction costs and uncertainty, and increase the possibility of team members taking consistent behavior [

29]. Digital literacy can enhance social trust and help build a social network and market environment that supports low-carbon consumption, thus reducing the cost of transformation [

30]. However, low-carbon consumption often faces challenges related to “green premium” and concerns about authenticity [

31]. In this case, digital literacy serves as a “bridge of trust”. Family members can use digital skills to verify the authenticity of corporate environmental statements and identify “green bleaching” behaviors, so as to channel trust to companies that truly adopt sustainable practices. On the other hand, by participating in online communities and social media groups, individuals can share their low-carbon consumption experiences and recommend reliable brands to like-minded people, thus generating positive peer effects and community supervision. This platform-based social trust reduces the cost of information search and decision-making risks for families when choosing low-carbon products. It also creates a social atmosphere that makes low-carbon consumption an ideal choice. Therefore, low-carbon transformation has become a more sustainable and easier form of collective action [

32].

Finally, the theory of human capital points out that human capital formed through the accumulation of education, skills and knowledge is a key determinant of personal productivity, employment opportunities and income [

33]. As the economy becomes more digital, digital skills have become an important part of modern human capital. Digital literacy is able to enhance the competitiveness of individuals in the labor market and broaden their career paths, thus increasing household disposable income [

34]. In addition, according to Maslow’s hierarchy of needs and its expansion in consumption research, with the improvement in income levels, consumer needs tend to shift from basic survival needs to development-oriented and enjoyment-oriented needs [

35]. Consumers will then pay more attention to product quality, safety and long-term value. Therefore, on the one hand, revenue growth can alleviate the budget constraints caused by the “green premium” associated with low-carbon products. It enables families to undertake upfront investment in green commodities such as energy-saving appliances, new energy equipment and organic food [

36,

37]. On the other hand, it encourages consumer demand to shift from meeting basic needs to pursuing higher quality and more sustainable lifestyles, which further strengthens the preference for low-carbon, healthy and environmentally friendly products. Although income growth itself may increase emissions by expanding overall consumption, the combination of digital literacy and green awareness makes it more likely for high-income families to follow the benign path of “income growth-green consumption-emission reduction”. This helps to reconcile the relationship between economic improvement and low-carbon transformation. Based on these, the following assumptions are put forward:

Hypothesis 2 :Digital literacy indirectly affects households’ carbon emissions by enhancing residents’ understanding of environmental pressure, social trust, income level, etc.

The impact of digital literacy on HCE is not uniform. It has significant differences in different aspects such as urban–rural gap, human capital, income level, gender and age. Drawing on digital divide theory, the urban–rural structure produces pronounced disparities in digital infrastructure provision, skills development and training opportunities, and the breadth of real-world application contexts between cities and rural areas [

38,

39]. In urban areas, extensive network coverage and high device penetration rate provide a solid foundation for digital literacy. The impact of digital consumption is mainly reflected in structural optimization and energy efficiency management, and its marginal impact on carbon emission growth has been weakened [

40,

41]. In contrast, in rural areas, initiatives such as the “digital village” strategy have rapidly increased the Internet penetration rate [

42]. Enhancements in residents’ digital literacy facilitate the adoption of emerging consumption modes, including e-commerce and on-demand delivery and logistics services. However, due to the weak green infrastructure, the limited promotion of energy-saving technology, and the relative lag of low-carbon awareness, the improvement in digital skills has not effectively brought about the improvement in energy efficiency. On the contrary, the expansion of consumption scenarios and the increase in energy demand have led to a rapid rise in carbon emissions, thus delaying the moment when emissions began to decline. Therefore, in rural areas, digital literacy in the “compensatory digitalization” stage has a stronger role in promoting the growth of carbon emissions. In addition, the theory of human capital points out that the accumulation of education, skills and knowledge shapes an individual’s cognitive ability and behavior [

43].

Secondly, high human capital groups usually have stronger information processing capabilities and higher environmental awareness. Therefore, the improvement in digital literacy not only broadens the consumption scenario, but also quickly contributes to the formation of green consumption behaviors [

44], such as the use of energy management tools or the choice of low-carbon products. In this way, their carbon emission growth is relatively small, and emission reduction measures can be implemented earlier. In contrast, the improvement in digital skills of low human capital groups mainly enhances the accessibility and convenience of consumption [

45]. However, due to cognitive limitations and insufficient application of technology, it is difficult for these groups to effectively use digital tools to optimize energy efficiency. Therefore, they are more likely to fall into the cycle of “digital convenience-high-carbon consumption”, resulting in a more obvious linear growth trend in carbon emissions.

Third, the theory of income stratification points out that the uneven distribution of economic resources will lead to systematic differences in consumption capacity and structure [

46]. High-income families have strong purchasing power and diversified consumption options. They benefit from higher digital literacy, which makes it easier for them to access high-carbon services such as smart homes and luxury travel. However, once a certain threshold is reached, they can obtain more resources to support green transformation [

47], such as investing in energy-saving equipment and carbon footprint tracking, so as to establish a benign path of “expansion first and optimization”. Low-income families are bound by budgetary restrictions, and their consumption is mainly concentrated on basic needs. The improvement in digital literacy is mainly used to improve convenience and cost-effective consumption, which makes it difficult for them to support more in-depth green transformation. Therefore, their carbon growth inertia is stronger, and the potential for emission reduction adjustment is more limited.

Fourth, the gender dimension of heterogeneity can be explained by the theory of social roles, which emphasizes how gender roles affect individual consumption choices and preferences for using numbers [

48]. Women are often responsible for daily shopping, child education and home management, which makes them more likely to use digital tools such as e-commerce and social networks to simplify the consumption process. With the improvement in digital literacy, their frequent and diversified consumption behavior has exacerbated the increase in carbon emissions. In contrast, men are more inclined to pay attention to energy efficiency tools and low-carbon technologies at an early stage. Therefore, the impact of digital literacy on the growth of male HCE is relatively weak, and the emission reduction adjustment has occurred earlier. Finally, age group differences are consistent with the life cycle theory, which shows that there will be significant differences in personal consumption needs, family responsibilities and technology adoption at different stages of life [

49]. As the main decision-makers of family consumption, the level of digital literacy of middle-aged people has improved, which affects high-carbon areas such as family energy use, transportation and children’s education. Therefore, their carbon emission growth effect is the most significant, and the emission reduction point has not yet stabilized. They may be in the behavioral locking stage of “high digital capacity–high carbon consumption”. Although young people have also shown a significant increase in carbon emissions, they have begun to partially mitigate them through low-carbon methods such as the sharing economy and online second-hand trading. In contrast, minors and the elderly have less direct impact on digital skills. Their consumption patterns are more influenced by family members or traditional habits, which leads to a relatively small direct impact on household consumption carbon emissions [

50]. The effect of digital literacy on consumption-based HCE is markedly heterogeneous across dimensions such as the urban–rural divide, human capital endowments, income, gender, and age. This reflects the fundamental structural differences in consumption behavior, technology use and environmental response between different groups in the process of digitalization. The following assumptions are put forward:

Hypothesis 3: The impact of digital literacy on HCE varies in many aspects, including factors such as urban–rural disparities, human capital, income levels, gender and age.

Against the backdrop of the deep embedding of digital technologies in everyday household life, the mechanisms through which digital literacy affects HCE cannot be adequately captured by traditional linear models [

51]. A substantial body of prior research treats digital literacy as an exogenous determinant and implicitly presumes a unidirectional linear association between digital literacy and carbon emissions, thus ignoring the systematic complexity and multi-dimensional coupling mechanism that shape family consumption behavior. From the perspective of complex system theory, HCE are generated by the nonlinear interaction between multiple factors, including digital literacy, environmental awareness, institutional environment and infrastructure conditions [

52]. In particular, as digital technology increasingly affects consumption decision-making, the impact of digital literacy on HCE is not independent; on the contrary, it is systematically constrained by many factors such as environmental responsibility, access to clean energy, the strictness of environmental regulations, and the quality of digital infrastructure.

This influence reflects a structural dependence, which is characterized by the model of “conditional combination-behavior path-carbon emission result”. We must abandon the traditional linear model and adopt an analytical framework that can capture multi-dimensional coupling and asymmetric causality. Specifically, there are complex coupling mechanisms between digital literacy, environmental awareness, policy tools and infrastructure, which together shape the path of household consumption carbon emissions. Its influence mechanism can be explained from two levels. First of all, from the perspective of cognitive behavior, digital literacy enables families to obtain low-carbon information and identify green products, but its effect is largely affected by the regulatory factor of environmental responsibility. When the sense of environmental responsibility is high, digital literacy can effectively guide low-carbon consumption behavior, such as using intelligent platforms to compare energy efficiency or choose products with low carbon footprint. In contrast, when the sense of environmental responsibility is low, digital literacy may strengthen the preference for high-carbon consumption [

53], such as frequently recommending the purchase of high-energy consumption or non-necessities through algorithms, thus increasing the carbon footprint. On the contrary, from the perspective of institutional opportunities, the severity of supervision and the breadth of digital infrastructure together constitute important external limiting factors. In an environment with developed digital infrastructure and strict environmental regulation, digital literacy can effectively encourage families to manage their carbon accounts and obtain emission reduction incentives. However, if there is not enough institutional support, even if the family has a high digital literacy, it may be difficult to turn it into meaningful emission reduction actions [

54]. Therefore, the impact of digital literacy on consumption-based HCE shows a multi-dimensional, nonlinear and interdependent coupling effect. The effect will vary significantly depending on the differences in external conditions and internal cognitive configuration. We put forward the following assumptions:

Hypothesis 4: The impact of digital literacy on consumption-based HCE cannot be fully reflected through linear models; on the contrary, it is determined by the interaction between multiple determinants of interaction.

Previous studies explored the relationship between digitalization, carbon emissions and sustainable development-oriented transformation from perspectives such as the expansion of the digital economy, the popularization of information technology and the evolution of green consumption models. These studies have established a relatively mature analytical framework and theoretical foundation. However, a large number of studies on digital technology and carbon emissions mostly adopt macro or medium-level research methods, which makes it difficult to observe individual differences in digital capabilities and determine how these differences are transformed into differences in carbon emissions based on consumption. In general, the existing literature has the following main limitations. First of all, many studies adopt a macro perspective, focusing on the expansion of the digital economy or the widespread popularization of digital technology; therefore, their evaluation of carbon emission results usually focuses on emissions in production links or overall emissions. In contrast, there are still limited studies on the use of micro-level household data to directly capture individual and family-level consumption behaviors and the carbon emissions they contain. This positioning method limits our understanding of the actual reaction of families in consumption decision-making. It also often ignores the significant differences in digital literacy and digital ability of different individuals. Therefore, in the digital environment, it is difficult to reveal the micro-level sources of differences in family consumption-related carbon emissions. Secondly, some studies based on the spread of digital technology and the increase in the convenience of consumption believe that higher digital literacy will significantly expand household consumption, thus increasing energy use and carbon emissions. Liu et al. (2024) used data at the family level to find that digital literacy usually increases carbon emissions related to household consumption by expanding consumption channels and strengthening online consumption behavior [

15]. However, this research idea often ignores the fact that digital literacy is a dynamic human capital, and its operation mechanism may undergo structural changes at different stages of development. With a relatively low level of digital literacy, the rebound effect caused by consumer empowerment and technology may dominate, leading to an increase in HCE. At a higher level, efficiency improvement, stronger environmental awareness and optimization of consumption structure become more significant, and the direction of the impact on emissions may be reversed. Third, many studies regard digital literacy as an isolated factor and focus on its “average effect”. This makes it difficult to identify the asymmetric causal path generated under different combinations of conditions. Therefore, the conclusion is often only a binary expression, that is, digital literacy either increases emissions or reduces emissions, and cannot reveal the various mechanisms generated by carbon emissions related to household consumption under different conditions.

In view of these gaps, this study expands and improves the previous research in three aspects. At the theoretical level, we have integrated the insights of risk perception theory, human capital theory and Maslow’s hierarchy of needs theory to build a coherent framework, which shows that the relationship between digital literacy and consumption-based HCE may be nonlinear and may present an inverted U-shaped pattern. This helps to solve the problem of insufficient attention to stage dependence effects in previous studies. Secondly, at the mechanism level, we examined multiple channels through which digital literacy affects carbon emissions related to household consumption—perceived environmental pressure, social trust and income. This transcends the limitations of single-channel interpretation. Finally, at the methodological level, we have introduced a configuration analysis framework to identify the coupling effect of digital literacy with multiple dimensions such as motivation, opportunity and ability. This method reveals the multiple ways and asymmetrical causal patterns behind the carbon emissions related to household consumption. Therefore, it provides more systematic and detailed empirical evidence for understanding the low-carbon transformation of families in the context of accelerated digitalization.

6. Discussion

This study systematically evaluates how digital literacy affects the HCE from the micro level, focusing on the mechanism behind it, nonlinear dynamics and multiple ways of influence. Through such research, it provides a new empirical basis for understanding the transformation of low-HCE of families in an increasingly digital environment. Compared with existing research, our findings expand the relevant literature from several important aspects.

First of all, we found that there is a statistically significant inverted U-type nonlinear relationship between digital literacy and HCE. This result helps to explain the contradictory evidence in the literature about whether digitalization will increase or reduce HCE. On the one hand, existing research believes that the advancement of digital technology and the improvement in digital skills may increase energy consumption and emissions by expanding consumption, strengthening online shopping and increasing the demand for on-demand services. On the other hand, they also emphasize the possibility of achieving emission reductions by improving energy efficiency, enhancing information transparency and guiding green consumption more strongly. Our research results show that these two effects are not mutually exclusive. On the contrary, they play a leading role in different stages of the development of digital literacy. At a lower level, the effect of consumption expansion and technological rebound is more significant. Once digital literacy exceeds a threshold, efficiency improvement, consumption structure upgrading and the internalization of low-carbon behavior will become more and more important, thus reducing HCE related to household consumption. This result addresses a key limitation of previous studies, that is, these studies rely on linear models, making it difficult to capture the long-term and dynamic effects of digitalization.

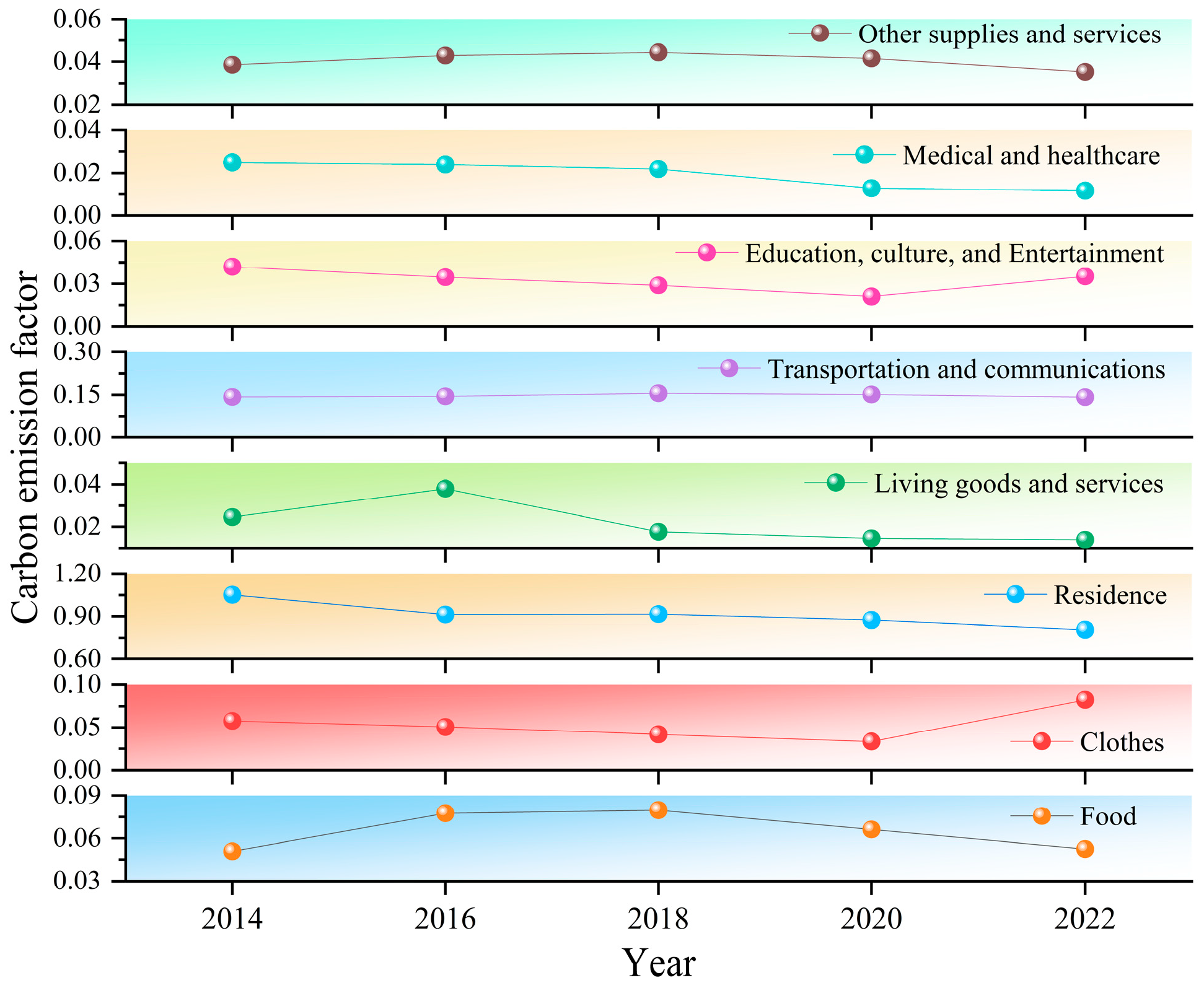

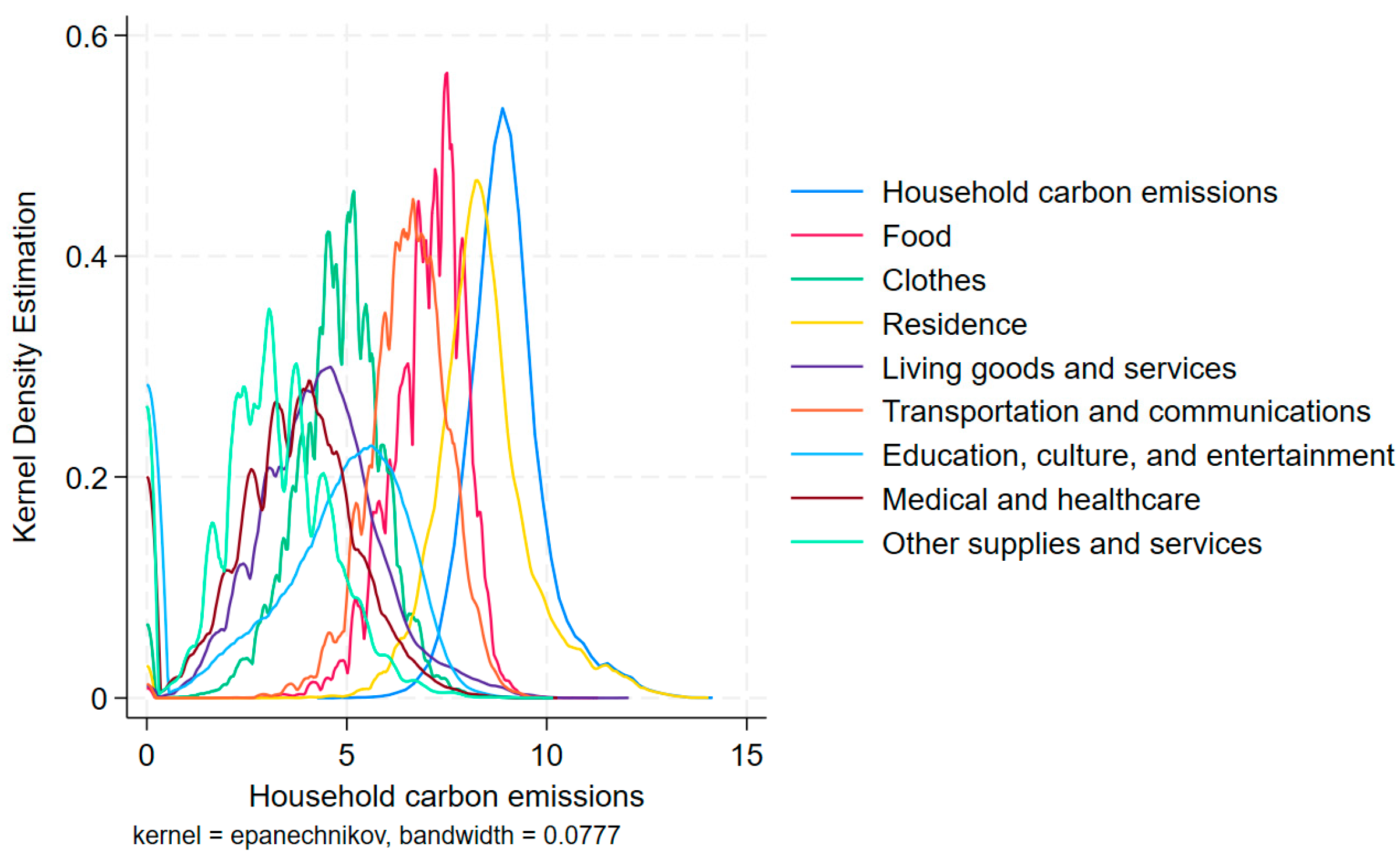

Secondly, from the perspective of consumption structure, the impact of digital literacy is obviously different in different consumption categories. Spending on transportation and communication is most sensitive to changes in digital literacy. With the improvement in digital literacy, this category has shown strong emission reduction potential. This model reflects the role of online substitution, information-driven travel and efficiency improvement in this field. In contrast, the turning point of housing-related emissions appeared the earliest. This shows that household energy use in the housing sector is moving faster from a digitally driven expansion phase to an adjustment phase dominated by energy efficiency improvements and finer energy management. This finding shows that the low-carbon transformation in the field of household consumption is not carried out in various fields at the same time, but in a clear order in different sectors, and its transformation paths are also different.

Third, our research results confirm that digital literacy does not affect the relationship between family carbon emissions and consumption through a single channel. On the contrary, it will function simultaneously through multiple mechanisms, including perceived environmental pressure, social trust and income levels. On the one hand, digital literacy enhances the intrinsic motivation of low-carbon consumption by improving information acquisition and risk awareness. On the other hand, as a form of human capital, it can increase employment opportunities and income, thus enhancing purchasing power, and may exert upward pressure on carbon emissions. The coexistence of these mechanisms further explains why the overall effect of digital literacy is non-linear. This also shows that relying on a single intermediary channel is not enough to fully understand the impact of digital literacy on the environment.

Finally, our analysis shows that there is no single sufficient condition for the transformation of household consumption to low-carbon. On the contrary, this transformation is determined by the dynamic interaction between multiple factors, including digital literacy, environmental responsibility, public environmental awareness, digital infrastructure and institutional environment. In different contexts, digital literacy can work together with a stronger sense of environmental responsibility and public attention, so as to cultivate low-carbon consumption values. In addition, when the infrastructure and institutional conditions are supportive, it can also strengthen the family and amplify the emission reduction effect of technology. This finding goes beyond the category of “average effect” that traditional regression analysis focuses on. It highlights the diversity of family decarbonization paths and its dependence on environmental conditions.

7. Conclusions and Policy Implications

7.1. Conclusions

Using CFPS microdata from, this study combines a two-way fixed effect model with robustness testing, mechanism testing, heterogeneity analysis and fsQCA to systematically determine how digital literacy affects HCE. The research results show that:

First, there is a robust inverted U-shaped nonlinear relationship between digital literacy and HCE. At early stages of digital literacy improvement, wider use of digital technologies lowers transaction and information search costs. It also expands online shopping and digital service scenarios, and increases demand for logistics delivery and related services. These changes raise HCE. When digital literacy reaches a higher level, households become better at acquiring and processing information and applying digital tools. They are more able to use these tools for energy-use management, identifying green products, and improving consumption decisions. As a result, the consumption pattern shifts from “scale expansion” to “efficiency improvement,” and HCE decline.

Second, the effect of digital literacy on HCE differs structurally across consumption types. The strongest emission-reducing effect is observed in transportation and communication, followed by healthcare, and both effects become stronger as digital literacy increases. Both basic and development-oriented consumption display an overall inverted U-shaped pattern. However, the turning point appears earliest for housing-related consumption. As digital literacy improves, its effect shifts more quickly from an emission-increasing phase driven by consumption expansion to an emission-reducing phase dominated by energy-efficiency gains and energy-saving management.

Third, there are systematic differences in the effect of digital literacy among different groups. With the improvement in digital literacy, the emissions of rural residents, those with low human capital, low-income families and women have increased more. This may be because digital technology has stimulated more demand for carbon-intensive basic commodities that may be concentrated in these groups. However, the turning point threshold for emission reduction is relatively low for women and rural residents. This shows that once these groups acquire a certain amount of digital capabilities, they can transform digital skills into emission reduction practices at an earlier stage, so as to achieve low-carbon transformation faster.

Fourth, digital literacy affects the HCE through the dual transmission mechanism. On the one hand, digital literacy can improve residents’ perception of environmental pressure and enhance social trust. This prompts families to adopt low-carbon consumption models and energy-saving technologies, thus reducing HCE. Higher digital literacy can also increase the income of residents, which may expand the scale of consumption and accelerate the upgrading of consumption. In particular, it will increase the demand for energy-intensive goods and services, thus increasing the HCE.

Fifth, the low-carbon transformation in household consumption reflects the dynamic interaction between many factors, and multiple paths can coexist. For example, the path of “consensus-driven and digital support”, the path of “capacity compensation and behavioral transformation”, and the path of “infrastructure support and cultural internalization”. Digital literacy can be combined with environmental responsibility and public environmental concerns to promote the value transformation to low-carbon consumption endonously. Under the condition of perfect infrastructure, it can also provide support for families and enhance the effectiveness of technology in emission reduction.

7.2. Policy Implications

This study puts forward the following suggestions. First of all, policy efforts should take the improvement in digital literacy as a key entry point, while avoiding the belief that digitalization will automatically reduce emissions. The impact of digital literacy on HCE is obviously phased and non-linear, which shows that digitalization itself does not necessarily bring emission reduction. With a low level of digital literacy, digital technology is more likely to increase carbon emissions by reducing consumption barriers and expanding consumption. Therefore, policies to promote the popularization of digital skills should also include low-carbon guidance.

Secondly, policymakers should implement targeted policy programs that reflect the differences in emission reduction potentials in different consumption areas. In the process of digitalization, the response to emission reductions in areas such as transportation and communication and housing consumption is more rapid or more significant, indicating that the implementation of policies in these areas is expected to yield higher returns. On the one hand, by expanding intelligent transportation systems, promoting online alternative services, and strengthening information-based travel management, the digital emission reduction potential in the fields of transportation and communication can be further released. On the other hand, in the field of housing, policies should accelerate the popularization of smart home equipment, energy use monitoring and refined energy management systems. This helps families shift from “digital consumption expansion” to “digital energy efficiency management” as soon as possible. In contrast, stronger price signals and clearer institutional constraints are needed for consumption areas with weak or delayed emission reduction responses. This can prevent digital convenience from being transformed into continuous high-carbon consumption habits.

Thirdly, a low-carbon transition in household consumption does not rely on technology or policy alone. It is the result of joint effects from cognition, capability, and institutional conditions. Household mitigation policies should not be limited to subsidizing energy-efficient products or promoting single technologies. Instead, they should coordinate “soft constraints” with “hard conditions.” For example, policymakers can integrate low-carbon information disclosure, public environmental participation, and community-level digital governance into the household mitigation system. This can reduce both the cognitive and the implementation costs of low-carbon behavior.

Fourth, low-carbon transitions in household consumption can follow multiple coexisting pathways. In some regions or groups, the transition relies more on internal drivers such as values and a sense of responsibility. In areas with stronger digital infrastructure and more mature institutions, capability empowerment and technological substitution play a more decisive role. Policies should adopt differentiated strategies by group, region, and scenario to improve the sustainability and inclusiveness of low-carbon transitions at the household level.