From Linear to Circular: Barriers to Sustainable Transition in the Saudi Banking Sector

Abstract

1. Introduction

- RQ1.

- To what extent do customer engagement barriers hinder the implementation of the circular economy in Saudi banks?

- RQ2.

- How do process-related barriers affect the integration of the circular economy?

- RQ3.

- How do dynamic capability barriers influence banks’ ability to adopt circular economy initiatives?

2. Literature Review

2.1. Banking and Circular Economy Integration: A Resource-Based and Stakeholder-Driven

2.2. Barriers to Circular Economy Adoption in the Banking Sector

2.3. Circular Economy Barriers in Banks

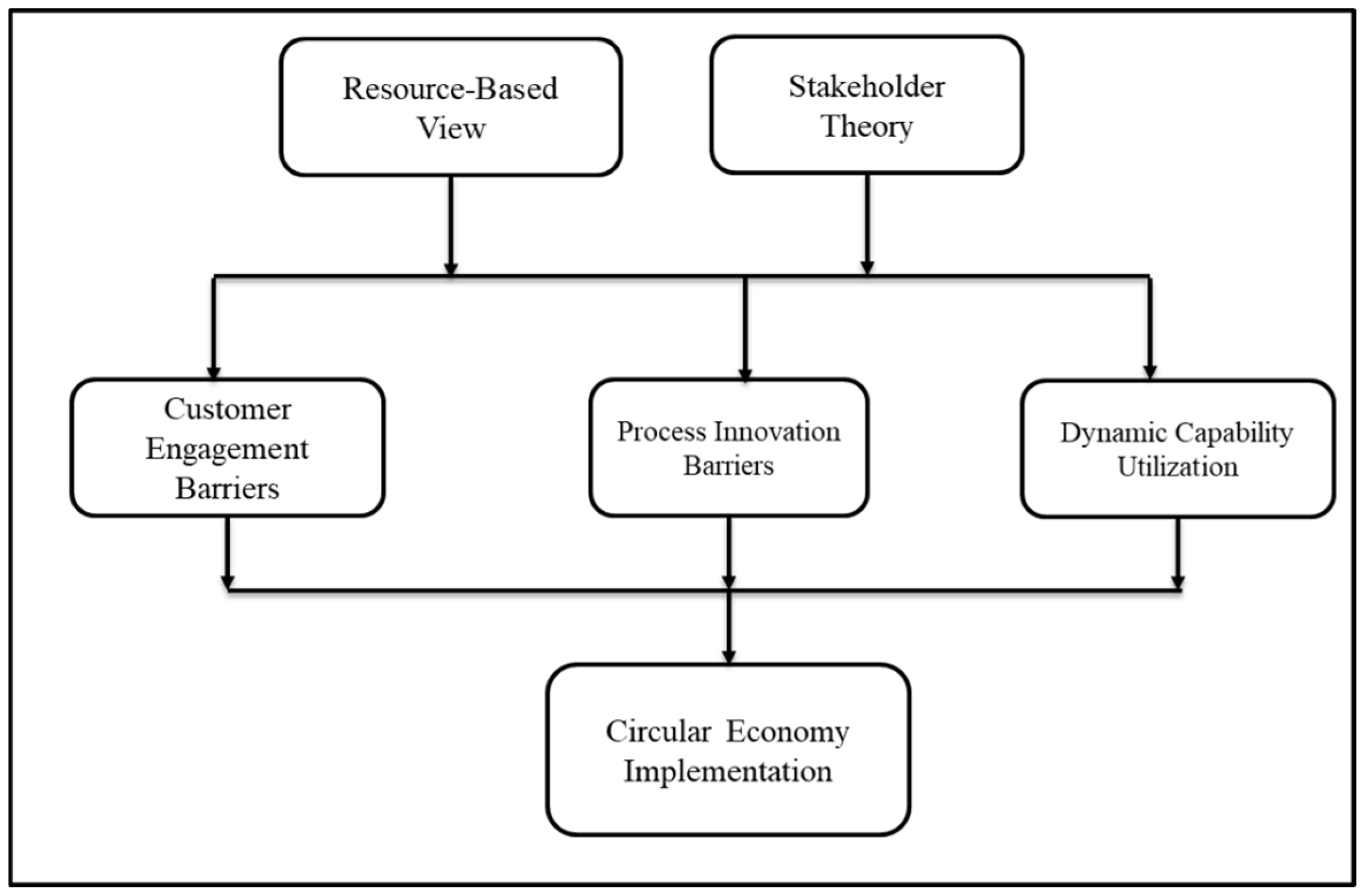

3. Theoretical Framework

3.1. Hypothesis Development

3.1.1. Customer Engagement Barriers to Circular Economy Implementation

3.1.2. Process Improvement Barriers to Circular Economy Implementation

3.1.3. Dynamic Capability Utilization Barriers to Circular Economy Implementation

4. Methodology

4.1. Research Design and Sampling

4.2. Data Analysis

5. Analysis and Discussion of the Results

5.1. Profile of the Respondents

5.2. Barriers to the Circular Economy

5.3. Discussion of the Results

6. Conclusions

6.1. Practical Implications

6.2. Policy and Managerial Recommendations

7. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Questionnaire | |||||||

| Identify the Barriers to Customer Engagement (CE), Process Innovation (PI), Dynamic Capability (DC) Utilization, and Circular Economy Adoption in the Banking Sector | |||||||

| (Put a Tick Mark (✓) wherever applicable) | |||||||

| Please click in the following box if you agree to the above conditions? ☐ Yes ☐ No | |||||||

| By clicking Yes, you consent that you are willing to answer the questions in this survey. | |||||||

| 1. Organization Information | |||||||

| 1.1 Organization Type: ☐ Government Sector ☐ Semi-Government Sector ☐ Public Sector ☐ Private Sector | |||||||

| 2. Self-Information | |||||||

| 2.1 Age in Years________________ | |||||||

| 2.2 Gender ☐ Male ☐ Female | |||||||

| 2.3 Marital Status ☐ Single ☐ Married ☐ Separated ☐ Divorced | |||||||

| 2.4 Level of education ☐ High School ☐ Diploma ☐ Bachelors ☐ Masters ☐ PhD ☐Others (Please Specify) __ | |||||||

| 2.5 How many years have you been working in your current organization ☐0 to 1 Yr. ☐1 to 3 Yrs. ☐3 to 5 Yrs ☐ More than 5 Yrs. | |||||||

| 3. Barriers | |||||||

| This section identifies the barriers. Please tick (√) as | |||||||

| Barriers | Strongly Disagree (1) | Strongly Agree (5) | |||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |||

| CE1 | Customer engagement initiatives in the financial sector are frequently met with resistance from customers | ||||||

| CE2 | Limited access to customer data and analytics hampers our ability to personalize services effectively | ||||||

| CE3 | Our organization faces challenges in identifying and adapting to emerging market opportunities | ||||||

| CE4 | Regulatory constraints create challenges in implementing innovative customer engagement strategies | ||||||

| CE5 | Insufficient training and skill development programs for employees impact our ability to enhance customer engagement | ||||||

| CE6 | Employees often resist changes related to process innovation | ||||||

| CE7 | Organizational culture does not encourage or support a culture of innovation | ||||||

| CE8 | Decision-making processes are slow and delay being agile in adapting to change | ||||||

| DC1 | Lack of effective communication channels makes it difficult to reach and engage with customers | ||||||

| DC2 | Resistance from customers is a barrier to adopting new customer engagement technologies and methods | ||||||

| DC3 | Lack of access to cutting-edge technologies limits our ability to innovate processes | ||||||

| DC4 | Employees lack the necessary skills and training to utilize dynamic capabilities effectively | ||||||

| DC5 | Inadequate knowledge-sharing and transfer processes hinder dynamic capability utilization | ||||||

| DC6 | Limited access to external market insights affects our ability to adapt dynamically | ||||||

| DC7 | Lack of awareness and understanding of CE concepts within the organization is a barrier to the adoption | ||||||

| DC8 | Lack of expertise and skills related to sustainable practices hinders our ability to adapt | ||||||

| DC9 | The limited availability of sustainable technologies in the market is a barrier to circular economy adoption | ||||||

| DC10 | Lack of Incentives from the government hinders the implementing circular economy | ||||||

| DC11 | Lack of policy and delay in implementing the circular economy in your organization | ||||||

| PI1 | Slow decision-making processes delay our agility in adapting to change | ||||||

| PI2 | Our organization faces challenges in setting and tracking sustainability goals | ||||||

| PI3 | Our organization faces challenges in setting and tracking sustainability goalsn | ||||||

References

- Geissdoerfer, M.; Morioka, S.; de Carvalho, M.; Evans, S. Circular business models: A review. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 277, 123741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A. From Linear to Circular: A Comprehensive SWOT Analysis of India’s Circular Economy Potential. Int. J. Innov. Sci. Eng. Manag. 2025, 4, 189–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akram, M.U.; Ghazanvi, A.I.; Abubakar, M. Saudi Arabia’s Circular Economy Path to Global Leadership. Int. J. Bus. Manag. 2025, 20, 46–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfantookh, N.; Osman, Y.; Ellaythey, I. Implications of Transition towards Manufacturing on the Environment: Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030 Context. J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2023, 16, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulami, S.; Al Sulami, M.; Nasr, J.; Sharawi, H. Circular Economy Analysis as a Tool to Enhance Sustainability of Supply Chains in Kingdom Saudi Arabia and a Means to Achieve Saudi Vision 2030. Mod. Econ. 2024, 15, 566–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsaud, K.; Assad, F.; Patsavellas, J.; Salonitis, K. A Comparative Analysis of Circular Economy Practices in Saudi Arabia. Sustainability 2025, 17, 3281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geissdoerfer, M.; Morioka, S.N.; de Carvalho, M.M.; Evans, S. Sustainable business models: An integrative framework. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 198, 1615–1629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munonye, W.C.; Munonye, D.I. Banking on circularity: Can financial institutions become the engines of a regenerative economy? Front. Environ. Econ. 2025, 4, 1588384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, B.; Kumar, A.; Sassanelli, C.; Kumar, L. Exploring the role of finance in driving circular economy and sustainable business practices. J. Clean. Prod. 2025, 486, 144480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solangi, Y.A.; Alyamani, R.; Almakhles, D. Evaluating challenges and policy innovations for renewable energy development in a circular economy: A path to environmental resilience in Saudi Arabia. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 335, 121932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu-Bakar, H.; Almutairi, T. Integrating sustainability and circular economy into consumer-brand dynamics: A Saudi Arabia perspective. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhelyazkova, V. The role of banks for the transition to circular economy. In Circular Economy: Economy-Recent Advances, New Perspectives, and Applications; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2020; pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almulhim, A.I.; Al-Saidi, M. Circular economy and the resource nexus: Realignment and progress towards sustainable development in Saudi Arabia. Environ. Dev. 2023, 46, 100851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellen MacArthur Foundation. Towards the Circular Economy: Economic and Business Rationale for an Accelerated Transition; Ellen MacArthur Foundation: Cowes, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Haukkala, T. The EU Circular Economy Action Plan: Key Assumptions and Strategic Risks. LIEPP Policy Brief 2025, 8, hal-05087218. [Google Scholar]

- Barney, J. Firm Resources and Sustained Competitive Advantage. J. Manag. 1991, 17, 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, K.; Prakash, A. Developing a framework for assessing sustainable banking performance of the Indian banking sector. Soc. Responsib. J. 2019, 15, 689–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahajan, R.; Lim, W.M.; Sareen, M.; Kumar, S.; Panwar, R. Stakeholder theory. J. Bus. Res. 2023, 166, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellen MacArthur Foundation. Financing the Circular Economy; Ellen MacArthur Foundation: Cowes, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Taera, E.G.; Lakner, Z. Sustainable Finance: Bridging Circular Economy Goals and Financial Inclusion in Developing Economies. World 2025, 6, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pillai, M.; Bennasr, H.; Ben Hassen, T.; Al-Yafei, W.B. Exploring the Circular Economy in International Business: Current Trends and Future Directions—A Systematic Literature Review. Sustainability 2025, 17, 9532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saudi Green Initiative (SGI). About the Saudi Green Initiative and National Programs for Waste Management and Circular Economy; Saudi Green Initiative: Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Islam, M.T.; Ali, A. Sustainable green energy transition in Saudi Arabia: Characterizing policy framework, interrelations and future research directions. Next Energy 2024, 5, 100161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, B.d.S.M.; de Carvalho, F.L.; de Camargo Fiorini, P. Circular economy and financial aspects: A systematic review of the literature. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geissdoerfer, M.; Wisdom, K.; Julian, K. Conceptualizing Circular Ecosystems: An Analysis of 45 Definitions. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2025, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Chen, P. Sustainable Finance Meets FinTech: Amplifying Green Credit’s Benefits for Banks. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, S.; Mitra, A.; Aggarwal, S. Impact of Environmental, Social, and Governance Parameters on Financial Performance of Firms: A Cross-Country Analysis. J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2025, 18, 666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, J.; Tan, F.J.; Ramakrishna, S. Transitioning to a circular economy: A systematic review of its drivers and barriers. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govindan, K.; Hasanagic, M. A systematic review on drivers, barriers, and practices towards circular economy: A supply chain perspective. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2018, 56, 278–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galvão, G.D.A.; De Nadae, J.; Clemente, D.H.; Chinen, G.; De Carvalho, M.M. Circular economy: Overview of barriers. Procedia Cirp. 2018, 73, 79–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piila, N.; Sarja, M.; Onkila, T.; Mäkelä, M. Organisational drivers and challenges in circular economy implementation: An issue life cycle approach. Organ. Environ. 2025, 35, 523–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.A.R.; Shah, A.S.A.; Yu, Z.; Tanveer, M. A systematic literature review on circular economy practices: Challenges, opportunities and future trends. J. Entrep. Emerg. Econ. 2022, 14, 754–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlJaber, A.; Martinez-Vazquez, P.; Baniotopoulos, C. Barriers and Enablers to the Adoption of Circular Economy Concept in the Building Sector: A Systematic Literature Review. Buildings 2023, 13, 2778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patwa, N.; Sivarajah, U.; Seetharaman, A.; Sarkar, S.; Maiti, K.; Hingorani, K. Towards a circular economy: An emerging economies context. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 122, 725–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizos, V.; Behrens, A.; Van der Gaast, W.; Hofman, E.; Ioannou, A.; Kafyeke, T.; Flamos, A.; Rinaldi, R.; Papadelis, S.; Hirschnitz-Garbers, M.; et al. Implementation of Circular Economy Business Models by Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises (SMEs): Barriers and Enablers. Sustainability 2016, 8, 1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, V.H.; Hoang, T.H.; Nguyen, T.A.T.; Võ, X.H.; Nguyen, T.Q.A. Innovation Towards Circular Economy-A Theoretical Perspective. VNU J. Sci. Policy Manag. Stud. 2023, 39, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Hashmi, N.I.; Makhmudov, S.; Ghardallou, W.; Alam, M.M. Does financial sector development mitigate power sector-based carbon dioxide emissions to establish environmental sustainability in BRICS? J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 394, 127527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mhatre, P.; Panchal, R.; Singh, A.; Bibyan, S. A systematic literature review on the circular economy initiatives in the European Union. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2021, 26, 187–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duran, I.A.; Saqib, N. Load Capacity Factor and Environmental Quality: Unveiling the Role of Economic Growth, Green Innovations, and Environmental Policies in G20 Economies. Int. J. Energy Econ. Policy 2024, 14, 287–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringle, C.M.; Wende, S.; Becker, J.-M. SmartPLS 4; SmartPLS GmbH: Boenningstedt, Germany, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Carlos, R.L.; de Souza, E.B.; Mattos, C.A. Enhancing circular economy practices through the adoption of digital technologies. Bus. Strategy Dev. 2024, 7, e330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.; Ahsan, N.; Alam, S.S.; Kokash, H.A. Advancing Circular Economy Implementation in Malaysian SMEs: The Role of Financial Resources, Operational Alignment, and Absorptive Capacity. Circ. Econ. Sust. 2025, 5, 2843–2871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.A.R.; Umar, M.; Asadov, A.; Tanveer, M.; Yu, Z. Technological Revolution and Circular Economy Practices: A Mechanism of Green Economy. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, L. A Qualitative Analysis of Corporate Social Responsibility in Saudi Arabia’s Service Sector-Practices and Company Performance. Sustainability 2023, 15, 9284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Description | References | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Customer Engagement | Lack of awareness | Customers may be unaware of the benefits of circular economic practices or how to participate. | [2,31,32] |

| Perceived inconvenience | Customers may view circular economic practices as inconvenient or time-consuming. | [31,33,34] | |

| Limited access to information | Customers may not easily access information about circular economy products and services. | [31,34,38] | |

| Resistance to change | Customers may need to change consumption habits or adopt new behaviors, which can be met with resistance. | [31,32,33] | |

| Cost consideration | Circular economic products and services may be perceived as more expensive, which can deter customers. | [2,31,34] | |

| Process Innovation | Regulatory constraints | Current regulations may not incentivize or support innovation in circular economic practices. | [33,34,38] |

| Lack of technological infrastructure | Insufficient technology in financial institutions can limit support for circular economic processes. | [21,39] | |

| Investment risks | Financial institutions may view investments in circular economic innovations as too risky. | [32,40] | |

| Limited collaboration | Collaboration between stakeholders may be insufficient, hindering innovation. | [31,39] | |

| Uncertain market demand | Uncertainty about consumer demand for circular economy products and services can deter innovative efforts. | [32,34] | |

| Dynamic Capability Utilization | Organizational culture | The existing organizational culture may not support the development and utilization of the dynamic capabilities required for a circular economy. | [31,39] |

| Lack of skill development | Employees may lack the necessary skills to implement circular economic practices effectively. | [31,37] | |

| Inflexible organizational structure | Rigid organizational structures may hinder the agility necessary for effective dynamic capability utilization. | [5,34,37] | |

| Resistance to change | Internal resistance to change can hinder the development and use of dynamic capabilities. | [2,33] | |

| Resource constraints | Limited resources may restrict financial institutions’ ability to develop and deploy dynamic capabilities effectively. | [2,33] |

| Respondent Profile | Frequency (n = 418) | Percentage % |

|---|---|---|

| Organization Type | ||

| Public/Government Sector | 37 | 8.9 |

| Private Sector | 373 | 89.2 |

| Semi-Government Sector | 8 | 1.9 |

| Age | ||

| 20–25 | 74 | 17.7 |

| 26–35 | 217 | 51.9 |

| 36–45 | 85 | 20.3 |

| 46–56 | 35 | 8.4 |

| More than 56 | 7 | 1.7 |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 195 | 46.7 |

| Female | 223 | 53.3 |

| Marital Status | ||

| Single | 198 | 47.4 |

| Married | 192 | 45.9 |

| Divorced | 22 | 5.3 |

| Separated | 6 | 1.4 |

| Education Qualification | ||

| High School | 8 | 1.9 |

| Diploma | 8 | 1.9 |

| Bachelor’s Degree | 277 | 66.3 |

| Master’s Degree | 111 | 26.6 |

| PhD | 14 | 3.3 |

| Work Experience (Current Organization) | ||

| 0–1 | 75 | 17.9 |

| 2–4 | 16 | 3.8 |

| More than 4 Years | 327 | 78.2 |

| Code | Statement | Mean | Rank | Std. Deviation | t | Factor Loadings | Factor Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CE1 | Customer engagement initiatives in the financial sector are frequently met with resistance from customers | 3.56 | 1 | 1.137 | 64.016 | 0.843 | Accepted |

| CE4 | Regulatory constraints create challenges in implementing innovative customer engagement strategies | 3.54 | 2 | 1.117 | 63.574 | 0.875 | Accepted |

| CE5 | Insufficient training and skill development programs for employees impact our ability to enhance customer engagement | 3.52 | 3 | 1.136 | 60.764 | 0.869 | Accepted |

| CE2 | Limited access to customer data and analytics hampers our ability to personalize services effectively | 3.51 | 4 | 1.128 | 64.739 | 0.844 | Accepted |

| DC1 | The lack of effective communication channels makes it difficult to reach and engage with customers | 3.50 | 5 | 1.22 | 63.323 | 0.844 | Accepted |

| DC5 | Inadequate knowledge-sharing and transfer processes hinder dynamic capability utilization | 3.49 | 6 | 1.157 | 58.739 | 0.903 | Accepted |

| PI1 | Slow decision-making processes delay our agility in adapting to change | 3.48 | 7 | 1.132 | 55.565 | 0.846 | Accepted |

| DC8 | Lack of expertise and skills related to sustainable practices hinders our ability to adapt | 3.47 | 8 | 1.202 | 60.41 | 0.860 | Accepted |

| CE6 | Employees often resist changes related to process innovation | 3.46 | 9 | 1.203 | 62.827 | 0.872 | Accepted |

| DC2 | Resistance from customers is a barrier to adopting new customer engagement technologies and methods | 3.46 | 10 | 1.169 | 59.246 | 0.872 | Accepted |

| DC6 | Limited access to external market insights affects our ability to adapt dynamically | 3.46 | 11 | 1.205 | 55.377 | 0.886 | Accepted |

| DC9 | The limited availability of sustainable technologies in the market is a barrier to circular economy adoption | 3.45 | 12 | 1.158 | 58.742 | 0.904 | Accepted |

| DC10 | The lack of Incentives from the government hinders the implementation of a circular economy | 3.45 | 13 | 1.144 | 60.542 | 0.887 | Accepted |

| PI2 | Our organization faces challenges in identifying and adapting to emerging market opportunities | 3.44 | 14 | 1.186 | 59.278 | 0.843 | Accepted |

| DC7 | Lack of awareness and understanding of circular economy concepts within the organization is a barrier to the adoption | 3.44 | 15 | 1.186 | 57.065 | 0.904 | Accepted |

| DC11 | Lack of policy delay in implementing the circular economy in your organization | 3.44 | 16 | 1.122 | 61.665 | 0.637 | Deleted |

| DC3 | Lack of access to cutting-edge technologies limits our ability to innovate processes | 3.43 | 17 | 1.184 | 58.642 | 0.821 | Accepted |

| DC4 | Employees lack the necessary skills and training to utilize dynamic capabilities effectively | 3.43 | 18 | 1.227 | 59.211 | 0.903 | Accepted |

| CE3 | Our organization struggles to keep pace with evolving customer preferences and behaviours | 3.42 | 19 | 1.15 | 59.022 | 0.861 | Accepted |

| CE8 | Decision-making processes are slow and delay being agile in adapting to change | 3.39 | 20 | 1.148 | 60.93 | 0.602 | Deleted |

| PI3 | Our organization faces challenges in setting and tracking sustainability goals | 3.35 | 21 | 1.236 | 61.707 | 0.865 | Accepted |

| CE7 | Organizational culture does not encourage or support a culture of innovation | 3.32 | 22 | 1.223 | 62.721 | 0.821 | Accepted |

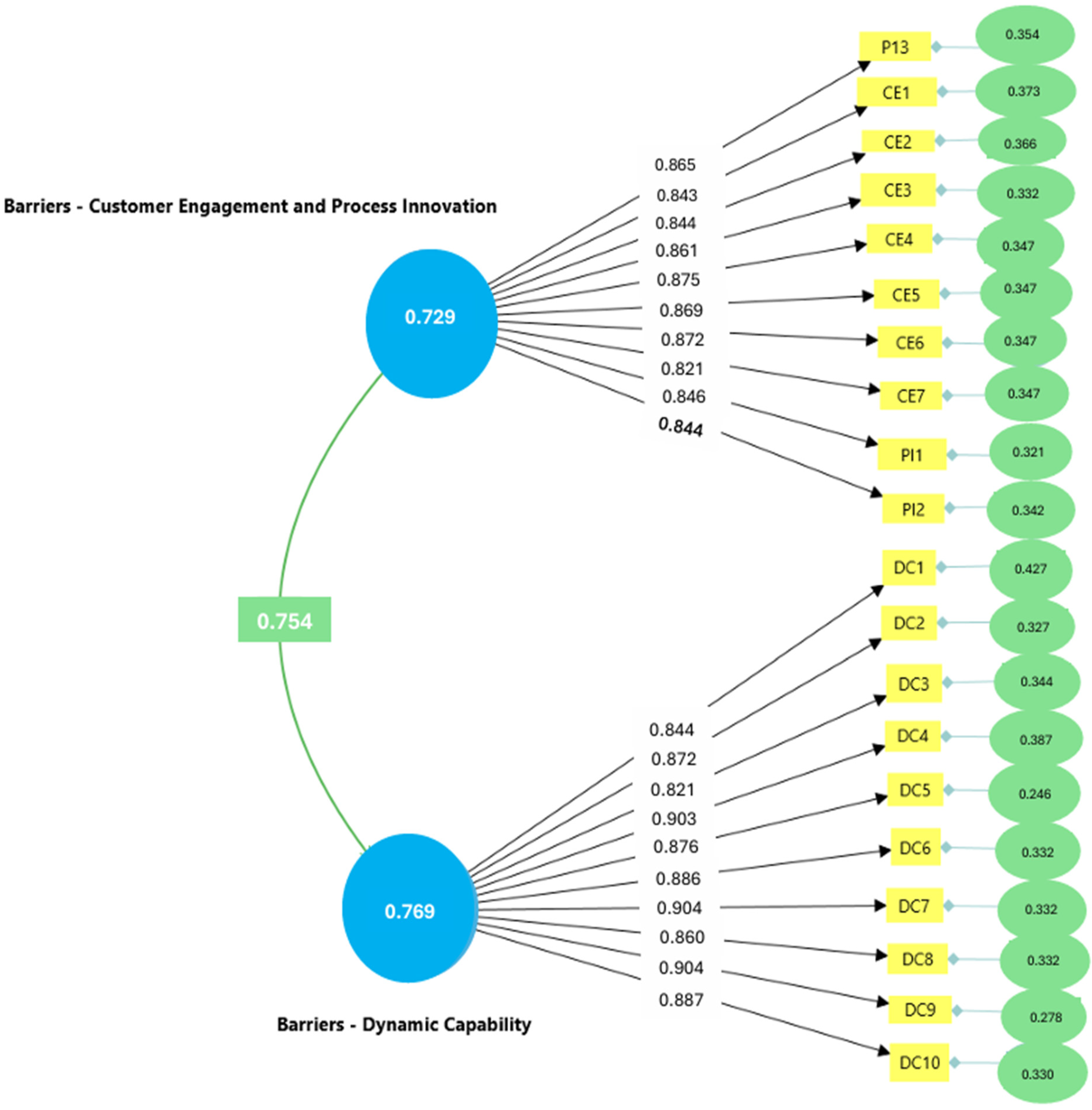

| Dimensions | Cronbach’s Alpha | Composite Reliability | Average Variance Extracted (AVE) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Barriers—Customer Engagement and Process Innovation | 0.964 | 0.964 | 0.729 |

| Barriers—Dynamic Capability | 0.973 | 0.973 | 0.769 |

| Dimensions | Barriers—Customer Engagement and Process Innovation | Barriers— Dynamic Capability |

|---|---|---|

| Barriers—Customer Engagement and Process Innovation | 1 | |

| Barriers—Dynamic Capability | 0.758 | 1 |

| S.No | Identified Barrier | Recommended Policy/Managerial Action |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Customer Resistance and Low Awareness | Launch nationwide green-banking awareness campaigns to educate customers on the benefits of CE. |

| Introduce sustainability-linked products (green loans, CE credit cards). | ||

| Provide digital incentives (discounts or reward points) for customers adopting sustainable banking behavior. | ||

| 2 | Regulatory Constraints and Policy Gaps | Develop national CE financial guidelines in accordance with Vision 2030. |

| Align banking regulations with international frameworks. | ||

| Create a regulatory sandbox for CE-oriented financial innovations. | ||

| 3 | Insufficient Employee Skills and Training | Integrate CE and sustainability modules into staff development programs. |

| Establish CE competency centers within major banks. | ||

| Collaborate with universities for certified green-finance training. | ||

| 4 | Limited Technological Infrastructure | Invest in digital transformation tools (AI, blockchain, analytics) to enable CE tracking and reporting. |

| Adopt green-IT policies for data centers and online services. | ||

| Partner with FinTech firms to develop CE-finance platforms. | ||

| 5 | Weak Process Innovation Culture | Establish innovation hubs to incubate circular-finance ideas. |

| Apply agile management to develop sustainable products rapidly. | ||

| Offer intrapreneurship grants for employee-led CE projects. | ||

| 6 | Lack of Government Incentives | Offer tax credits or interest rate reductions for CE investments. |

| Offer preferential lending rates for verified green projects. | ||

| Form public–private partnerships (PPPs) to de-risk CE financing. | ||

| 7 | Limited Collaboration among Stakeholders | Establish multi-stakeholder sustainability councils that link banks, regulators, and academia to foster collaboration and informed decision-making. |

| Develop a national circular-finance database for best practice sharing. | ||

| Encourage cross-sector alliances to co-fund CE initiatives. | ||

| 8 | Cultural Resistance and Innovation Mindset Gaps | Embed CE principles into mission statements and KPIs. |

| Recognize sustainability champions internally. | ||

| Implement change management programs to shift the organizational culture toward innovation and responsibility. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Mukherjee, A.; Pinto, L. From Linear to Circular: Barriers to Sustainable Transition in the Saudi Banking Sector. Sustainability 2026, 18, 673. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18020673

Mukherjee A, Pinto L. From Linear to Circular: Barriers to Sustainable Transition in the Saudi Banking Sector. Sustainability. 2026; 18(2):673. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18020673

Chicago/Turabian StyleMukherjee, Aroop, and Luisa Pinto. 2026. "From Linear to Circular: Barriers to Sustainable Transition in the Saudi Banking Sector" Sustainability 18, no. 2: 673. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18020673

APA StyleMukherjee, A., & Pinto, L. (2026). From Linear to Circular: Barriers to Sustainable Transition in the Saudi Banking Sector. Sustainability, 18(2), 673. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18020673