Emotional Well-Being and Environmental Sensitivity: The Case of ELF-MF Exposure

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area and Spatial Context

2.2. Participants and Sampling

2.3. Survey and Exposure Measurement

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Overview

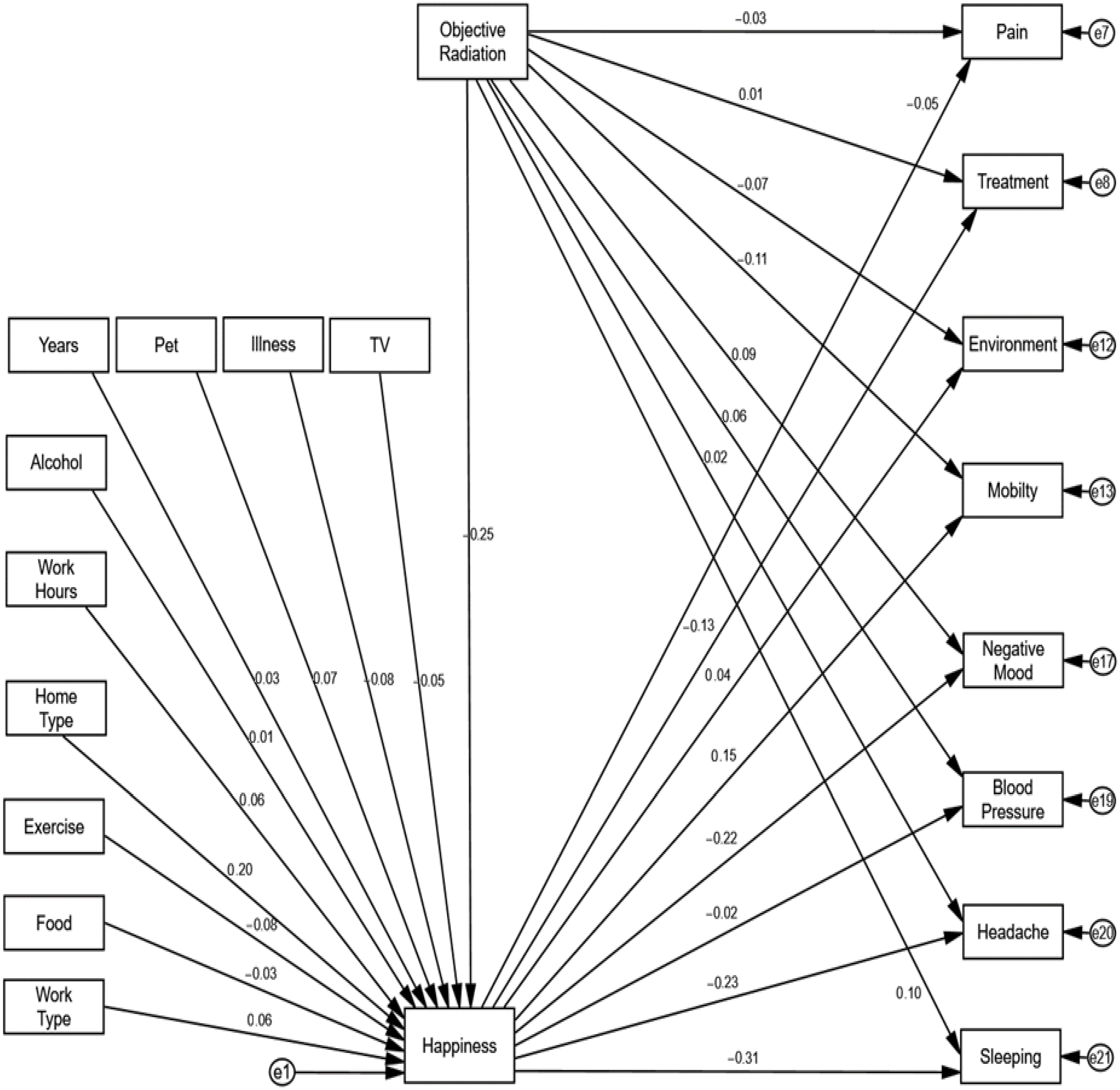

3.2. SEM Model Outcomes

3.3. Key Findings from SEM

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

- Our findings advocate for a dual strategy in environmental health policy: combining technical mitigation with community resilience-building. While reducing ELF-MF exposure through urban planning remains the primary goal, this study demonstrates that enhancing psychological well-being can serve as a vital secondary buffer against environmental stressors. Public health initiatives in proximity to power infrastructure should therefore integrate stress-reduction programs and community support systems. Future research should further explore these psychobiological pathways using longitudinal designs and biomarkers to better inform sustainable urban living standards. Environmental risk mitigation: Technical and regulatory efforts should continue to minimize ELF-MF exposure in residential areas. This includes careful urban planning (siting new high-voltage lines away from homes and schools), improvements in transmission line design and insulation to reduce emitted magnetic fields, and routine monitoring of field levels in neighborhoods near power infrastructure. These measures directly address the source of exposure and help prevent high-risk scenarios. For example, enforcing buffer zones around new power lines or investing in underground cabling where feasible could substantially reduce community ELF-MF levels.

- Promoting psychological resilience: At the same time, our results underscore the value of community-level initiatives to bolster mental and emotional well-being as a complement to exposure reduction. Public health programs in affected areas could incorporate stress-reduction workshops, mental health services, and social activities aimed at improving quality of life. Community organizations and local governments might facilitate support networks or group activities that enhance residents’ sense of happiness and cohesion. Even interventions not directly related to ELF-MFs—such as community exercise classes, hobby groups, or neighborhood beautification projects—can foster a more positive day-to-day experience for residents. By improving general happiness and life satisfaction, these efforts may reduce the degree to which an environmental hazard translates into perceived illness.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Survey Variables (With Response Scales and Summary Statistics)

| Variable Name | Question | Units | Min | Max | Average |

| Alcohol consumption | What are your weekly drinking habits? | 1–5 | 1 | 4 | 1.6 |

| Exercise | What is your level of physical activity? | 1–5 | 1 | 5 | 4.2 |

| Food | What is your type of diet? | 1–5 | 1 | 5 | 3.0 |

| Home type | What is your type of residence? | 1–2 | 1 | 2 | 1.2 |

| Illnesses | Do you suffer from any chronic diseases? | 1–2 | 1 | 2 | 1.2 |

| Pets | Do you have a pet at home such as a dog or a cat? | 1–2 | 1 | 2 | 1.3 |

| TV | How many hours do you watch TV a day? | 1–5 | 1 | 5 | 2.4 |

| Work hours | How many hours do you work a day? | 1–5 | 1 | 5 | 3.1 |

| Work type | What is your field of employment in which you work? | 1–5 | 1 | 5 | 4.4 |

| Years | How many years do you live in the current address? | 1–5 | 2 | 5 | 4.0 |

| ELF-MF, mG (OR) | What is the measured radiation intensity? | 1–5 | 0.30 | 36.40 | 4.5 |

| Happiness | What is your level of happiness/satisfaction? | 1–5 | 0 | 5 | 2.4 |

| Blood pressure | Do you suffer from high blood pressure? | 1–2 | 1 | 2 | 1.1 |

| Environment | How healthy is your physical environment? | 1–5 | 1 | 4 | 2.9 |

| Headache | Do you suffer from headaches? | 1–5 | 1 | 12 | 2.2 |

| Mobility | How far can you move from place to another? | 1–5 | 1 | 5 | 3.3 |

| Negative Mood | How often do you have negative emotions such as bad mood, despair, anxiety or depression? | 1–5 | 1 | 5 | 2.5 |

| Pain | To what extent physical pain prevents you from doing what you need to do? | 1–5 | 1 | 5 | 2.7 |

| Sleeping | How satisfied are you with your sleep? | 1–5 | 1 | 5 | 2.9 |

| Treatment | How much medical care needs you have in your daily life? | 1–5 | 0 | 5 | 2.7 |

Appendix B. Descriptive Statistics of Key Study Variables

| Variable Name | Coding | Mean | SD |

| Alcohol drinking | 1: Not at all, 2: Occasionally, 3: 1–3 times a week, 4: Once a day, 5: More than twice. | 1.59 | 0.64 |

| Exercise | 1: Every day, 2: 2–5 times a week, 3: Once a week, 4: 1–3 times a month, 5: Not at all | 4.17 | 1.10 |

| Food | 1: Vegetarian, 2: Poultry or fish, 3: Combination of poultry, fish, and red meat, 4: Red meat 1–2 times a week, 5: Red meat every day | 2.97 | 0.85 |

| Home type | 1: Detached house, 2: Apartment in the building | 1.19 | 0.40 |

| Illnesses | 1: Yes, 2: No | 1.20 | 0.40 |

| Pets | 1: No, 2: Yes | 1.31 | 0.46 |

| TV | 1: 0, 2: 1–2, 3: 2–4, 4: 5–6, 5: More than 6 | 2.43 | 0.87 |

| Work hours | 1: More than 12 h, 2: 9–12 h, 3: 7–9 h, 4: Less than 6 h, 5: Does not work | 3.08 | 0.97 |

| Work type | 1: Agriculture or fishing, 2: Heavy industry or manufacturing, 3: High-tech industry, 4: Construction and contracting work, 5: Services | 4.39 | 1.00 |

| Years | 1: Up to 2 years, 2: 3–6 years, 3: 7–11 years, 4: 12–16 years, 5: 16 years or more | 4.03 | 0.96 |

| ELF-MF, mG (OR) | 1: Less than 1 mG, 2: Between 1–2 mG, 3: Between 2–4 mG, 4: Between 4–10 mG, 5: More than 10 mG | 4.53 | 7.57 |

| Happiness | 1: Very happy, 2: Quite satisfied, 3: Sometimes do not know how I feel, 4: Sometimes unhappy, 5: Usually unhappy | 3.56 | 1.23 |

| Blood pressure | 1: Yes, 2: No | 1.15 | 0.36 |

| Environment | 1: Not at all, 2: A little, 3: Moderately, 4: Quite a lot, 5: Very much | 2.93 | 0.74 |

| Headache | 1: Not at all, 2: Occasionally, 3: 1–3 times a month, 4: 1–3 times a week, 5: Every day | 2.19 | 1.23 |

| Mobility | 1: Very bad, 2: Quite bad, 3: Neither good nor bad, 4: Good, 5: Very good | 3.34 | 0.93 |

| Negative Mood | 1: Not at all, 2: A little, 3: Occasionally, 4: Most of the time, 5: Always | 2.55 | 1.22 |

| Pain | 1: Not at all, 2: A little, 3: Moderately, 4: A lot, 5: Very much | 2.72 | 1.01 |

| Sleeping | 1: Very dissatisfied, 2: Dissatisfied, 3: Somewhat satisfied, 4: Satisfied, 5: Very satisfied | 2.30 | 0.95 |

| Treatment | 1: Not at all, 2: A little, 3: Moderately, 4: Quite a lot, 5: Very much | 2.68 | 1.10 |

| Number of valid observation | 427 | ||

Appendix C. Measurement Equipment Used in the Study

- A.

- Aaronia NF-5035 Spectrum Analyzer

- Features:

- Frequency range: 1 Hz–1 MHz

- Integrated 3D magnetic-field measurement coil

- Typical level range: 1 nT to 2 mT

- Filter bandwidth: 0.3 Hz (min)–10 MHz (max)

- Typical precision (base unit): ±3%

- Analog input range: 200 nV (min)–200 mV (max)

- FFT resolution: 1024 points

- Vector power measurement (I/Q) and True RMS: Yes

- Weight: 430 g

- Tripod connection: 1/4”

- EMC/EMI pre-compliance testing

- Environmental safety studies

- Occupational health assessments

- Core Technical Specifications

| Parameter | Specification | Units | Notes |

| Frequency Range | 1 Hz–1 MHz | Hz/MHz | Expandable up to 20 MHz or 30 MHz |

| Typical Accuracy | ±3% | % | High precision for compliance checks |

| H-Field Measurement | 1 pT–500 μT | pT/μT | Detects extremely weak magnetic fields |

| E-Field Measurement | 0.1 V/m–5000 V/m | V/m | Suitable for multiple standards |

| Analog Input Range | 200 nV–200 mV | nV/mV | Via DDC AC-in port (−150 dBm/Hz) |

| Filter Bandwidth (RBW) | 0.3 Hz–10 MHz | Hz/MHz | User-selectable resolution bandwidth |

| FFT Resolution | 1024 points | — | For detailed spectral analysis |

| Weight | 420 g | g | Lightweight and portable |

- Key Features and Advantages

- Integrated 3D Isotropic Magnetic Sensor: Ensures accurate, direction-independent measurements, eliminating positioning errors.

- Real-Time Spectrum Analysis: High-performance DSP with FFT/DFT for instant spectrum display.

- Advanced Measurement Capabilities: Includes Vector Power (I/Q) and True RMS detection for complex signals.

- Software & Interface: PC Analyzer Software CDM 2.06.00 for remote control and analysis; USB 2.0 connectivity; high-resolution LCD display.

- Application in Research

- B.

- Tenmars TM-192D Field Meter

- Features:

- Frequency range: 30 Hz–2000 Hz

- Triple-axis measurement of low-frequency electromagnetic fields

- Three-channel sensors for quick and easy measurement

- Built-in USB communication for data logging (capacity: 500 or 9999 datasets)

- Magnetic field units: Tesla (T) or Gauss (G)

- Functions: Data Hold (HOLD), Maximum Hold (MAX), Minimum Hold (MIN)

- Auto: or manual range selection

- Overload: indication and low-battery detector

- Auto: power-off for safety

- Specifications:

- Display: 4-digit, triple LCD

- Measuring range: 20, 200, 2000 mG; 2, 20, 200 μT

- Resolution: 0.01, 0.1, 1 mG or 0.001, 0.01, 0.1 μT

- Frequency response: 30 Hz–2000 Hz

- Sensor: Triple-axis (X, Y, Z)

- Accuracy:

- ○

- ±(3.0% + 30 dgt) at 50/60 Hz

- ○

- ±(2.5% + 5 dgt) at 50/60 Hz

- ○

- ±(5.0% + 5 dgt) at 30/2000 Hz

- Sample rate: 2.5 times/s

- Overload indication: “OL” displayed

- Power supply: 9 V battery (NEDA 1604, IEC 6F22, JIS 006P)

- Battery life: Approx. 100 h

- Instrument: SPECTRAN® NF-5035 Handheld EMC Spectrum Analyzer

- Manufacturer: Aaronia AG, Euscheid, Germany|Series: SPECTRAN NF Handheld Analyzers

Appendix D

| Predictor | B | S.E. | Wald | p | OR | 95 CI for OR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LL | |||||||

| Headaches | ELF-MF Exposure | 1.74 | 0.26 | 43.38 | <0.001 | 5.69 | 3.39 |

| Happiness | −0.44 | 0.27 | 2.61 | 0.106 | 0.64 | 0.38 | |

| Stress Level | ELF-MF Exposure | 2 | 0.28 | 51.23 | <0.001 | 7.39 | 4.28 |

| Sleep Satisfaction | ELF-MF Exposure | −1.29 | 0.25 | 25.93 | <0.001 | 0.28 | 0.17 |

| Happiness | 0.59 | 0.25 | 5.6 | 0.018 | 1.81 | 1.11 | |

| Mobility | ELF-MF Exposure | −1.22 | 0.32 | 14.17 | <0.001 | 0.29 | 0.15 |

| Health Satisfaction | ELF-MF Exposure | −3.03 | 0.31 | 92.37 | <0.001 | 0.05 | 0.03 |

| Perceived Health Impact | ELF-MF Exposure | 1.52 | 0.27 | 32.72 | <0.001 | 4.56 | 2.68 |

| Happiness | −0.95 | 0.25 | 14.68 | <0.001 | 0.39 | 0.24 |

Appendix E

| Variable | Study Sample | Or Akiva Population |

|---|---|---|

| Gender—Male | 187 (43.8%) | 9815 (49.3%) |

| Gender—Female | 240 (56.2%) | 10,087 (50.7%) |

| Age Group (years)—18–24 | 45 (10.5%) | 1722 * (12.6%) |

| Age Group (years)—25–34 | 92 (21.5%) | 2158 * (15.7%) |

| Age Group (years)—35–49 | 134 (31.4%) | 3863 * (28.2%) |

| Age Group (years)—50–69 | 128 (30.0%) | 4147 * (30.3%) |

| Age Group (years)—70+ | 28 (6.6%) | 1923 * (14.0%) |

| Birthplace—Israel | 298 (69.8%) | - |

| Birthplace—Former USSR | 78 (18.3%) | - |

| Birthplace—Western Europe | 28 (6.6%) | - |

| Birthplace—North America | 14 (3.3%) | - |

| Birthplace—Other | 9 (2.1%) | - |

| Home Type—Single-family house | 156 (36.5%) | - |

| Home Type—Apartment in building | 271 (63.5%) | - |

| Education (Years)—0–10 years | 83 (19.4%) | - |

| Education (Years)—11–12 years | 152 (35.6%) | - |

| Education (Years)—13–14 years | 118 (27.6%) | - |

| Education (Years)—15–18 years | 58 (13.6%) | - |

| Education (Years)—18+ years | 16 (3.7%) | - |

| Occupation Type—Agriculture/Fishing | 12 (2.8%) | - |

| Occupation Type—Heavy Industry/Manufacturing | 68 (15.9%) | - |

| Occupation Type—High-Tech | 45 (10.5%) | - |

| Occupation Type—Construction/Contracting | 124 (29.0%) | - |

| Occupation Type—Services | 178 (41.7%) | - |

| Study Sample (N = 427) | ||

| Or Akiva Population (2021) |

References

- Eskandani, R.; Zibaii, M.I. Unveiling the biological effects of radio-frequency and extremely low-frequency electromagnetic fields on the central nervous system performance. BioImpacts 2023, 14, 30064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokpınar, A.; Altuntaş, E.; Değermenci, M.; Yılmaz, H.; Baş, O. The impact of electromagnetic fields on human health: A review. Middle Black Sea J. Health Sci. 2024, 10, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klimek, A.; Rogalska, J. Extremely low-frequency magnetic field as a stress factor—Really detrimental? Insight into literature from the last decade. Brain Sci. 2021, 11, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pall, M.L. Electromagnetic fields act via activation of voltage-gated calcium channels to produce beneficial or adverse effects. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2013, 17, 958–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yakymenko, I.; Tsybulin, O.; Sidorik, E.; Henshel, D.; Kyrylenko, O.; Kyrylenko, S. Oxidative mechanisms of biological activity of low-intensity radiofrequency radiation. Electromagn. Biol. Med. 2016, 35, 186–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Touitou, Y.; Selmaoui, B. The effects of extremely low-frequency magnetic fields on melatonin and cortisol, two marker rhythms of the human circadian system. Dialogues Clin. Neurosci. 2012, 14, 381–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Megha, K.B.; Arathi, A.; Shikha, S.; Alka, R.; Ramya, P.; Mohanan, P.V. Significance of melatonin in the regulation of circadian rhythms and disease management. Mol. Neurobiol. 2024, 61, 5541–5571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalisch, R.; Baker, D.G.; Basten, U.; Boks, M.P.; Bonanno, G.A.; Brummelman, E.; Chmitorz, A.; Fernàndez, G.; Fiebach, C.J.; Galatzer-Levy, I.; et al. The resilience framework as a strategy to combat stress-related disorders. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2017, 1, 784–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pressman, S.D.; Jenkins, B.N.; Moskowitz, J.T. Positive affect and health: What do we know and where should we go? Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2019, 70, 627–650. [Google Scholar]

- Diener, E.; Oishi, S.; Tay, L. Advances in subjective well-being research. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2018, 2, 253–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S. The relationship between mental health, resilience, and happiness. Int. J. Indian Psychol. 2019, 7, 537–549. [Google Scholar]

- Hagström, M.; Auranen, J.; Ekman, R. Electromagnetic hypersensitive Finns: Symptoms, perceived sources and treatments—A questionnaire study. Pathophysiology 2013, 20, 117–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Z.; Ahmad, I.; Dar, M.A.; Belete, M.; Abebe, M.K.; Fentaw, G.; Sisay, M.; Taye, Z.M.; Amakelew, S.; Zewdu, G.S. Spatially adaptive modeling of soil erosion susceptibility using geographically weighted regression integrated with remote sensing and GIS techniques. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 42894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. WHOQOL-BREF: Introduction, Administration, Scoring and Generic Version of the Assessment (Field Trial Version); World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Ironson, G.; Banerjee, N.; Fitch, C.; Krause, N. Positive emotional well-being, health behaviors, and inflammation measured by C-reactive protein. Soc. Sci. Med. 2018, 197, 235–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine, G.N.; Cohen, B.E.; Commodore-Mensah, Y.; Fleury, J.; Huffman, J.C.; Khalid, U.; Labarthe, D.R.; Lavretsky, H.; Michos, E.D.; Spatz, E.S.; et al. Psychological health, well-being, and the mind-heart-body connection: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2021, 143, e763–e783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spinhoven, P.; Elzinga, B.M.; Penninx, B.W.J.H.; Giltay, E.J. Temporal relationships between happiness and psychiatric disorders and their symptom severity in a large cohort study. BMC Psychiatry 2021, 21, 356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okamura, H.; Mihara, K.; Tsuda, A.; Morisaki, T.; Tanaka, Y.; Shoji, Y. Subjective happiness is associated with objectively evaluated sleep efficiency and heart rate during sleep. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling, 4th ed.; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Kalaitzaki, A.; Tsouvelas, G.; Koukouli, S. Social capital, social support, and perceived stress in college students. Stress Health 2020, 36, 377–385. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, T.-L.; Chang, S.-C.; Hsieh, H.-F.; Huang, C.-Y.; Chuang, J.-H.; Wang, H.-H. Effects of mindfulness-based stress reduction on sleep quality and mental health for insomnia patients: A meta-analysis. J. Psychosom. Res. 2020, 135, 110144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raz-Steinkrycer, L.S.; Dubnov, J.; Gelberg, S.; Jia, P.; Portnov, B.A. ELF-MF exposure, actual and perceived, and associated health symptoms: A case study of an office building in Tel Aviv-Yafo, Israel. Sustainability 2022, 14, 11065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azizi, E.; Ayoobi, F.; Shamsizadeh, A.; Moghadam-Ahmadi, A.; Shafiei, S.A.; Khoshdel, A.; Mirzaei, M.R. Effect of short-time exposure to local extremely low-frequency magnetic fields on sleepiness in male rats. Basic Clin. Neurosci. 2022, 13, 519–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro, E.A.; Segura, J.; Portolés, M.; Gómez-Perretta, C. The Microwave Syndrome: A preliminary study in Spain. Electromagn. Biol. Med. 2003, 22, 161–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mild, K.H.; Oftedal, G.; Sandström, M.; Wilén, J.; Tynes, T. Comparison of symptoms experienced by users of analogue and digital mobile phones: A Swedish-Norwegian epidemiological study. Arbetslivsrapport 1998, 1998, 23. [Google Scholar]

- Song, C.F.; Tay, P.K.C.; Gwee, X.; Wee, S.L.; Ng, T.P. Happy people live longer because they are healthy people. BMC Geriatr. 2023, 23, 440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pressman, S.D.; Cohen, S. Does positive affect influence health? Psychol. Bull. 2005, 131, 925–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ATSDR. Exposure Dose Guidance for Life Expectancy and Exposure Factor; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services: Washington, DC, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Huss, A.; Roosli, M.; Brink, M. Noise and electromagnetic fields-outcome assessment in environmental epidemiology. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 2010, 213, 105–110. [Google Scholar]

- Bagheri, H.M.; Khanjani, N.; Ebrahimi, M.H.; Haji, B.; Abdolahfard, M. The effect of chronic exposure to extremely low-frequency electromagnetic fields on sleep quality, stress, depression, and anxiety. Electromagn. Biol. Med. 2019, 38, 96–101. [Google Scholar]

- Slovic, P. Perception of risk. Science 1987, 236, 280–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Pathway | Estimate (β) | 95% CI (Lower, Upper) | p-Value | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ELF-MF Exposure → Happiness | −0.25 | −0.48, −0.02 | 0.039 * | Higher exposure is linked to lower happiness. |

| ELF-MF Exposure → Headache freq | +0.02 | −0.06, +0.10 | 0.62 | No significant direct effect on headaches. |

| ELF-MF Exposure → Sleep problems | +0.10 | +0.02, +0.18 | 0.019 * | Higher exposure leads to more sleep disturbances. |

| ELF-MF Exposure → Mobility issues | −0.11 | −0.22, −0.00 | 0.048 * | Higher exposure leads to worse mobility (negative β indicates more mobility difficulty). |

| ELF-MF Exposure → Negative mood | +0.09 | −0.03, +0.21 | 0.12 | Positive but non-significant effect on mood. |

| Happiness → Headache freq | −0.23 | −0.36, −0.10 | 0.001 ** | Happier individuals report fewer headaches. |

| Happiness → Sleep problems | −0.31 | −0.45, −0.17 | 0.001 ** | Happier individuals have fewer sleep issues. |

| Happiness → Mobility | +0.15 | +0.05, +0.25 | 0.004 ** | Happier individuals have better mobility. |

| Happiness → Negative mood | −0.22 | −0.34, −0.10 | 0.001 ** | Happier individuals report less negative mood. |

| Happiness → Need for treatment | −0.13 | −0.22, −0.04 | 0.008 ** | Happier individuals less often feel they need medical care. |

| Exposure → Happiness → Headaches (indirect) | +0.009 | +0.001, +0.020 | 0.029 * | Indirect effect: exposure increases headaches via reducing happiness. |

| Exposure → Happiness → Sleep (indirect) | +0.010 | +0.001, +0.022 | 0.034 * | Indirect: exposure → worse sleep via lower happiness. |

| Exposure → Happiness → Mobility (indirect) | −0.005 | −0.010, −0.001 | 0.021 * | Indirect: exposure → mobility loss via lower happiness. |

| Exposure → Happiness → Neg. mood (indirect) | +0.009 | +0.001, +0.018 | 0.023 * | Indirect: exposure → worse mood via lower happiness. |

| Exposure → Happiness → Need treatment (indirect) | +0.005 | +0.0004, +0.011 | 0.025 * | Indirect: exposure → higher perceived need for med care via happiness. |

| Path | Estimate | Lower | Upper | p | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Controls | |||||

| Alcohol -> Happiness | 0.012 | −0.085 | 0.109 | 0.793 | None of the controls is confounding. |

| Exercise -> Happiness | −0.084 | −0.172 | 0.016 | 0.098 | |

| Food -> Happiness | −0.027 | −0.121 | 0.062 | 0.550 | |

| Home type -> Happiness | 0.203 | −0.039 | 0.403 | 0.086 | |

| Illness -> Happiness | −0.084 | −0.186 | 0.008 | 0.081 | |

| Pet -> Happiness | 0.071 | −0.023 | 0.156 | 0.134 | |

| TV -> Happiness | −0.049 | −0.135 | 0.040 | 0.292 | |

| Work hours -> Happiness | 0.056 | −0.036 | 0.162 | 0.205 | |

| Work type -> Happiness | 0.056 | −0.044 | 0.153 | 0.280 | |

| Years -> Happiness | 0.028 | −0.066 | 0.127 | 0.575 | |

| Objective Radiation (OR) | |||||

| mG_L_Obj -> Blood pressure | 0.063 | −0.031 | 0.171 | 0.195 | |

| mG_L_Obj -> Environment | −0.075 | −0.154 | 0.016 | 0.103 | |

| mG_L_Obj -> Happiness | −0.249 | −0.475 | −0.016 | 0.039 | OR reduces happiness. |

| mG_L_Obj -> Headache | 0.021 | −0.060 | 0.105 | 0.618 | |

| mG_L_Obj -> Mobility | −0.108 | −0.210 | −0.002 | 0.048 | OR reduces mobility. |

| mG_L_Obj -> Negative mood | 0.089 | −0.025 | 0.185 | 0.119 | |

| mG_L_Obj -> Pain | −0.035 | −0.131 | 0.060 | 0.499 | |

| mG_L_Obj -> Sleeping | 0.102 | 0.014 | 0.205 | 0.019 | OR increases frequency of sleep disorders. |

| mG_L_Obj -> Treatment | 0.011 | −0.091 | 0.118 | 0.802 | |

| Happiness (HP) | |||||

| Happiness -> Blood pressure | −0.017 | −0.134 | 0.085 | 0.705 | |

| Happiness -> Environment | 0.039 | −0.069 | 0.131 | 0.455 | |

| Happiness -> Headache | −0.230 | −0.326 | −0.135 | 0.001 | Happiness reduces the risk of headache. |

| Happiness -> Mobility | 0.150 | 0.050 | 0.248 | 0.004 | Happiness increases mobility. |

| Happiness -> Negative mood | −0.216 | −0.315 | −0.120 | 0.001 | Happiness positively affects mood. |

| Happiness -> Pain | −0.053 | −0.148 | 0.035 | 0.266 | |

| Happiness -> Sleeping | −0.309 | −0.402 | −0.220 | 0.001 | Happiness reduces sleep disorders. |

| Happiness -> Treatment | −0.130 | −0.225 | −0.036 | 0.008 | Happiness reduces perceived need for treatment. |

| Mediations | |||||

| OR -> HP -> Blood pressure | 0.000 | −0.001 | 0.002 | 0.552 | |

| OR -> HP -> Environment | −0.001 | −0.005 | 0.001 | 0.264 | |

| OR -> HP -> Headache | 0.009 | 0.001 | 0.021 | 0.029 | Happiness reduces the impact of OR on the risk of headache. |

| OR -> HP -> Mobility | −0.005 | −0.012 | −0.001 | 0.021 | Happiness reduces the impact of OR on mobility. |

| OR -> HP -> Negative mood | 0.009 | 0.002 | 0.019 | 0.023 | Happiness reduces the negative impact of OR on mood. |

| OR -> HP -> Pain | 0.002 | −0.001 | 0.007 | 0.188 | |

| OR -> HP -> Sleeping | 0.010 | 0.001 | 0.020 | 0.034 | Happiness reduces the impact of OR on sleep disorders. |

| OR -> HP -> Treatment | 0.005 | 0.001 | 0.013 | 0.025 | Happiness reduces the impact of OR on the need for treatment. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Raz-Steinkrycer, L.S.; Gelberg, S.; Portnov, B.A. Emotional Well-Being and Environmental Sensitivity: The Case of ELF-MF Exposure. Sustainability 2026, 18, 620. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18020620

Raz-Steinkrycer LS, Gelberg S, Portnov BA. Emotional Well-Being and Environmental Sensitivity: The Case of ELF-MF Exposure. Sustainability. 2026; 18(2):620. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18020620

Chicago/Turabian StyleRaz-Steinkrycer, Liran Shmuel, Stelian Gelberg, and Boris A. Portnov. 2026. "Emotional Well-Being and Environmental Sensitivity: The Case of ELF-MF Exposure" Sustainability 18, no. 2: 620. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18020620

APA StyleRaz-Steinkrycer, L. S., Gelberg, S., & Portnov, B. A. (2026). Emotional Well-Being and Environmental Sensitivity: The Case of ELF-MF Exposure. Sustainability, 18(2), 620. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18020620