Assessing the Supply and Demand for Cultural Ecosystem Services in Urban Green Space Based on Actual Service Utility to Support Sustainable Urban Development

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

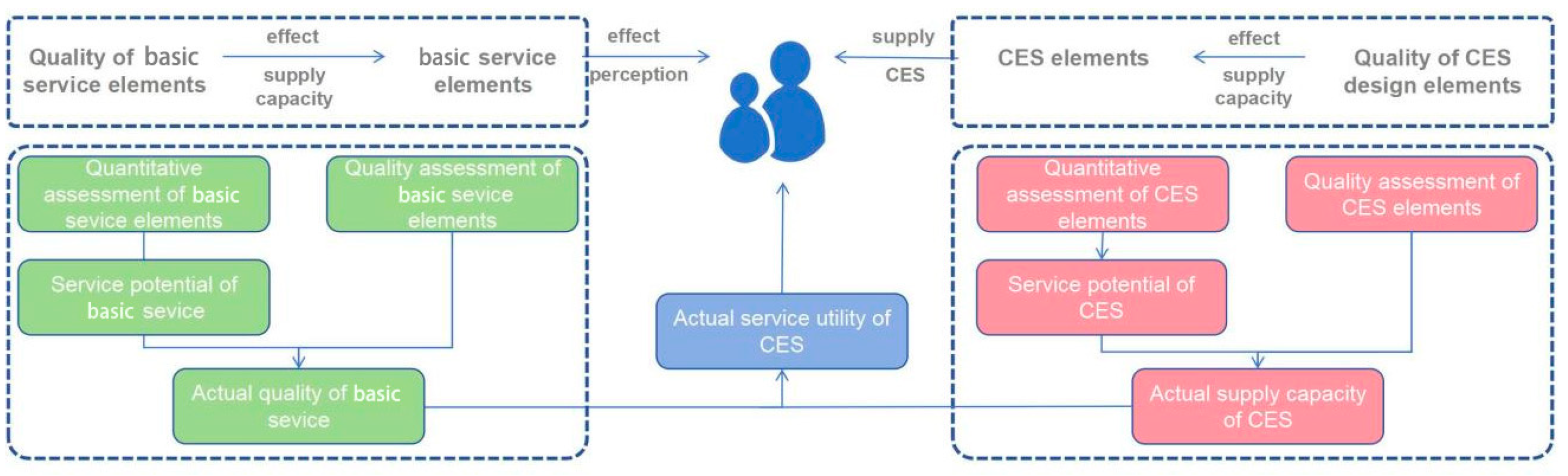

2.1. Constructing the Assessment Framework

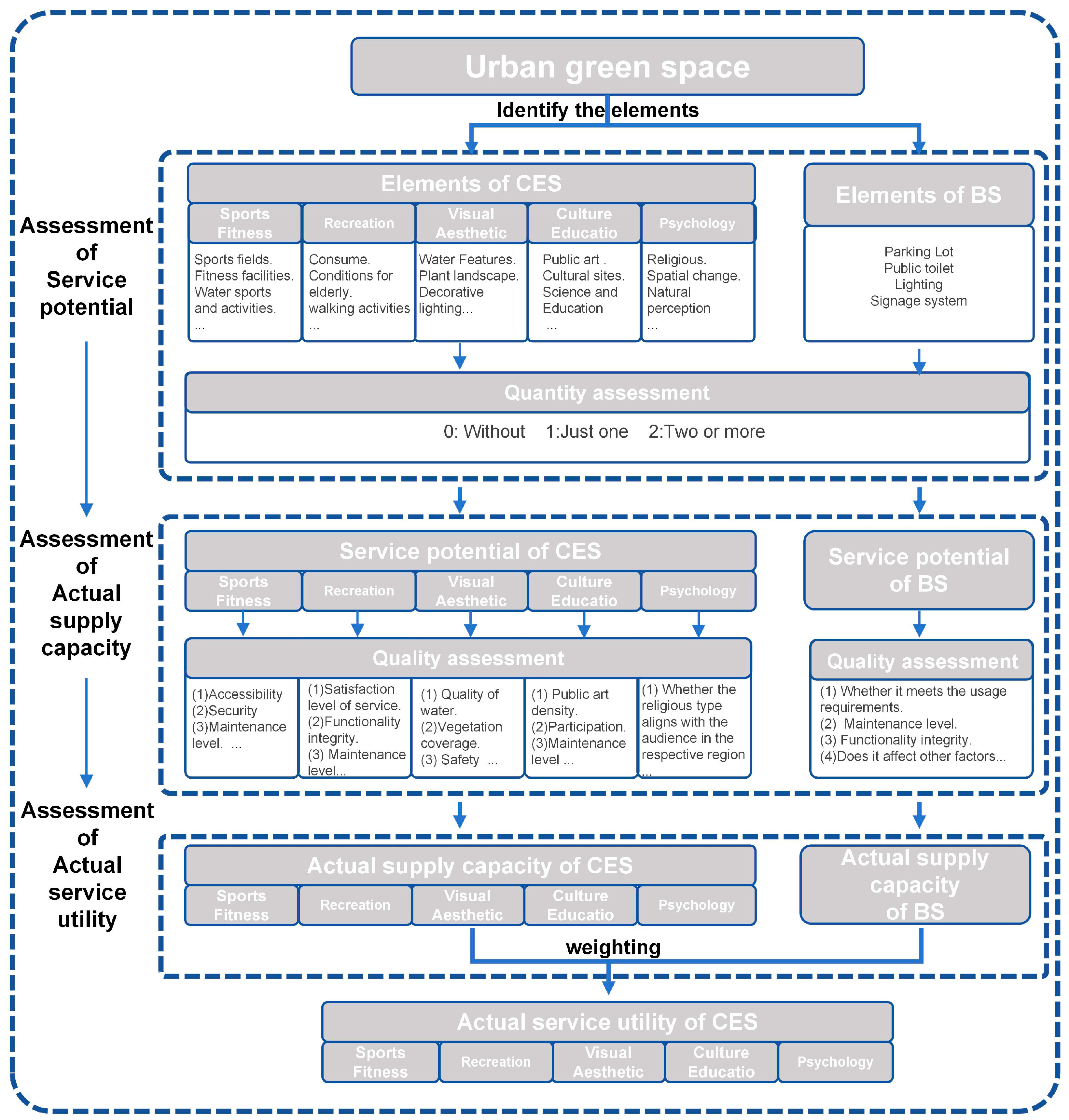

2.2. Indicator Selection and System Construction

2.3. Assessing and Calculating the Actual Service Utility of Green Space CES

- Supply potential: This indicates the upper limit of CES supply in green spaces. It is derived based on the quantity of CES elements present in the green spaces. The result represents whether the CES supply quantity in green spaces is sufficient.

- Actual supply capacity: This represents the actual CES supply capacity. It is obtained by conducting a quality assessment and weighting each CES supply element on the basis of the supply potential.

- Actual service utility: This represents the actual CES supply efficiency that green spaces can provide to people. It is obtained by weighting the actual supply capacity of CES and the actual supply capacity of the basic services.

2.3.1. Service Potential

2.3.2. Actual Supply Capacity

2.3.3. Actual Service Utility

2.4. Assessing CES Supply and Demand in Urban Green Spaces

2.4.1. Calculating CES Supply and Demand Based on Actual Service Utility

2.4.2. Calculating CES Supply and Demand Based on a Single Index

2.5. Impact of the Evaluation Framework on the Results

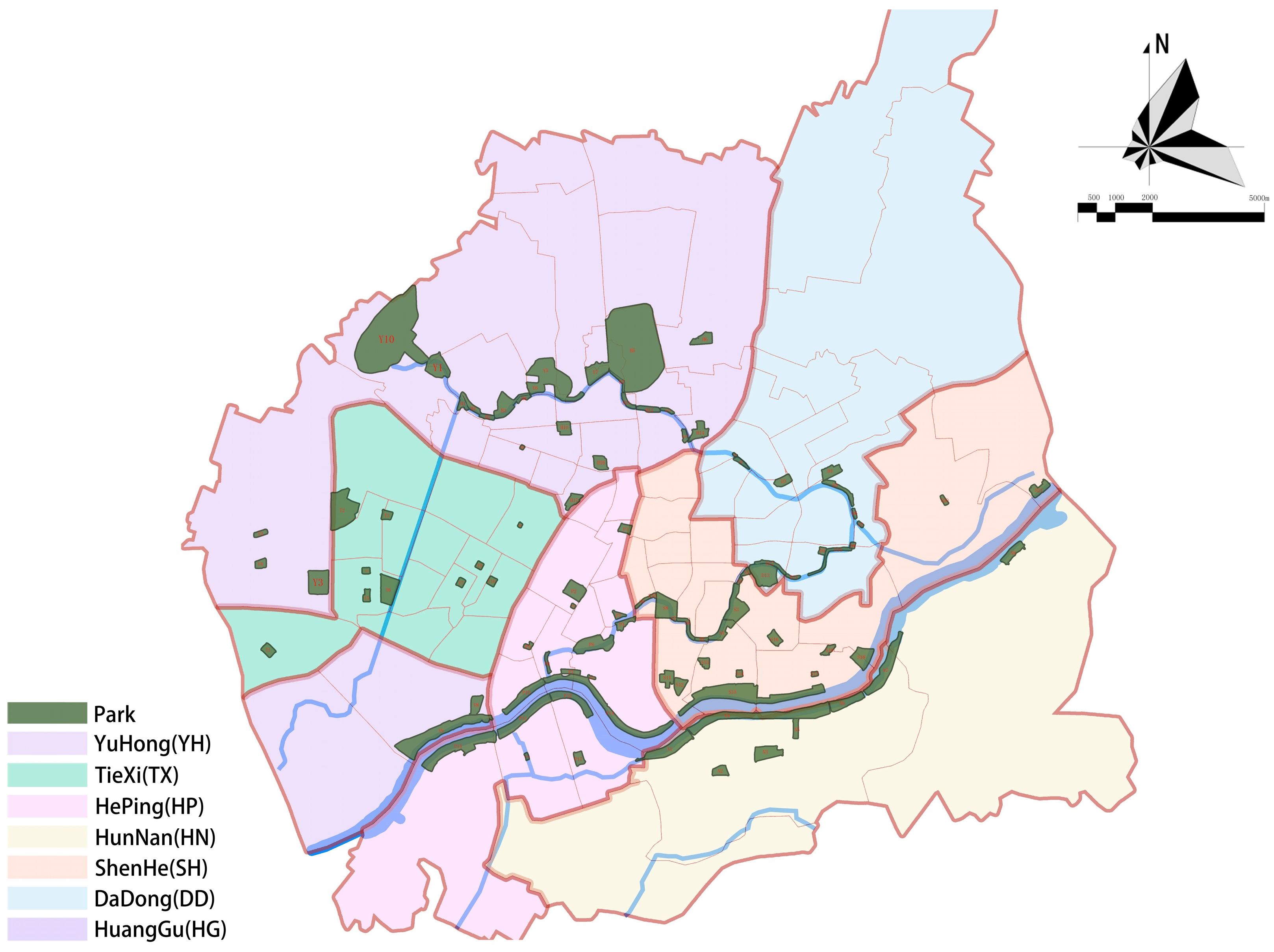

2.6. Selection of Sample Sites

2.7. Data Collection and Treatment

3. Results

3.1. Actual Service Utility of Different Park Types

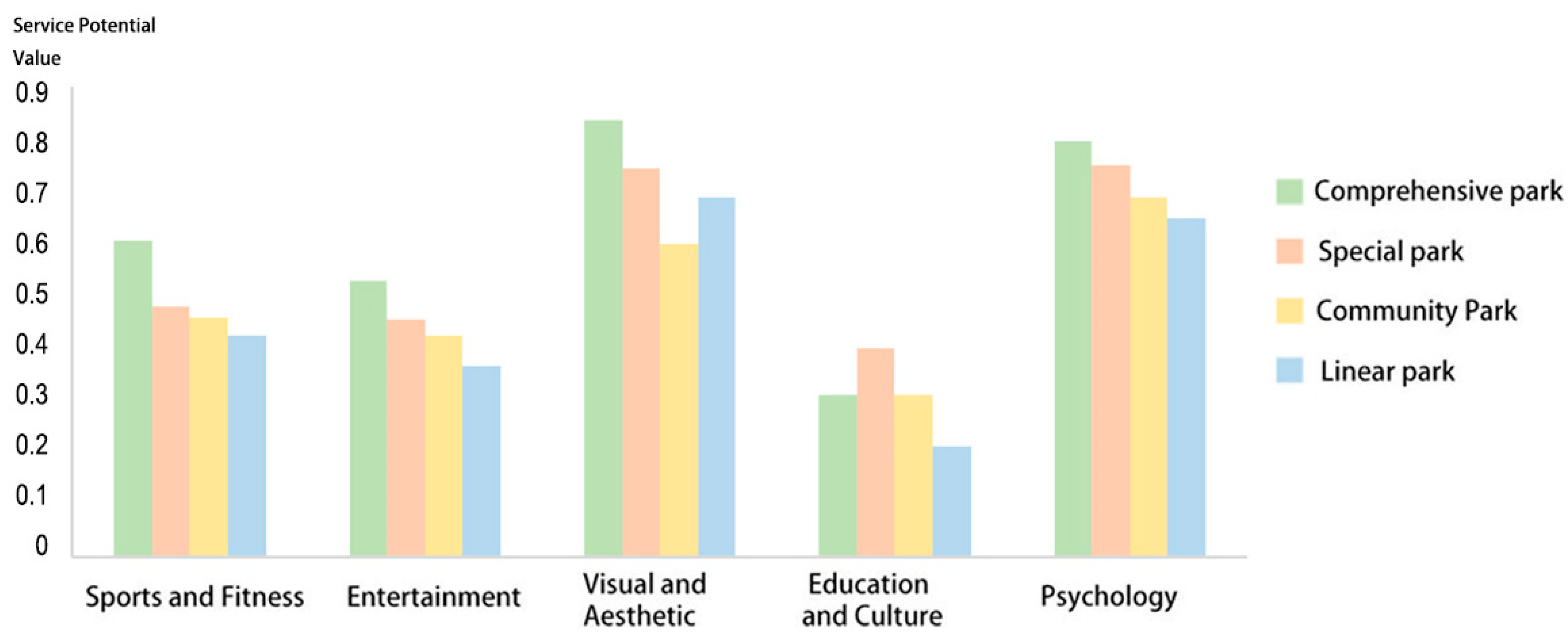

3.1.1. Results of Supply Potential

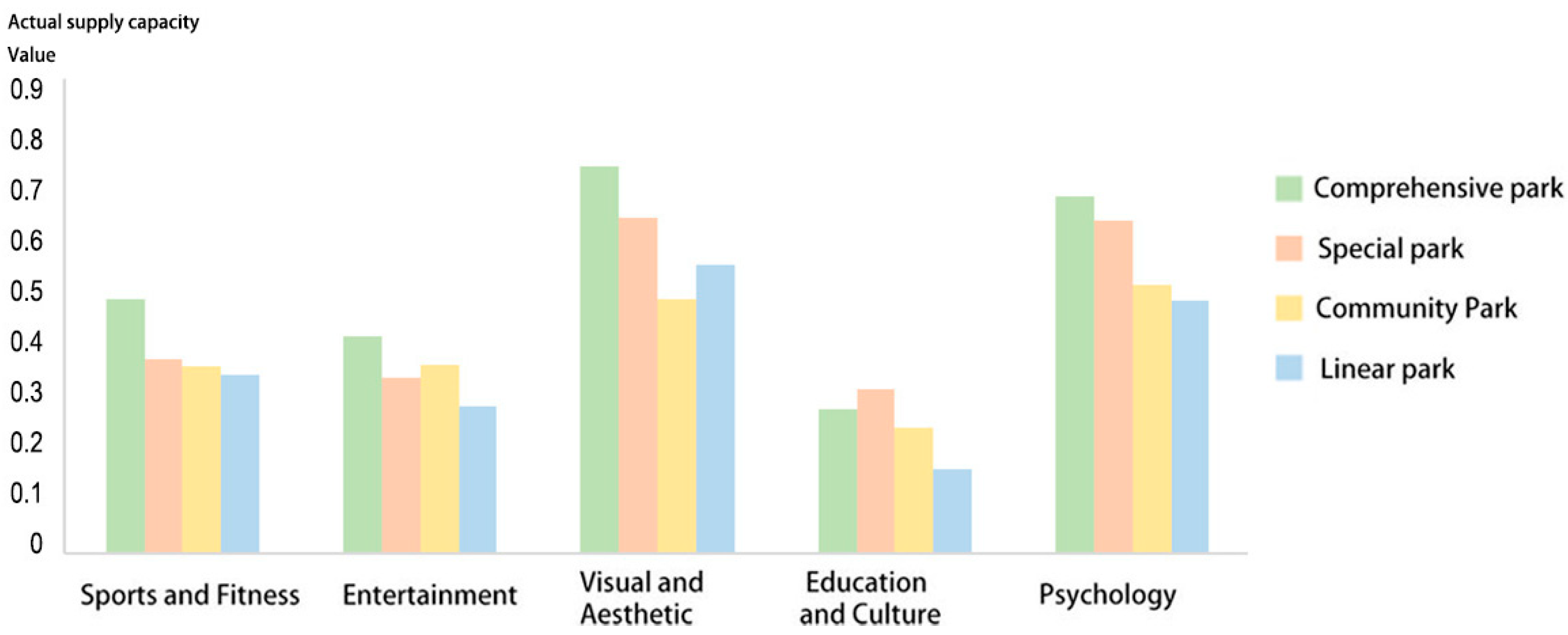

3.1.2. Results of Actual Supply Capacity

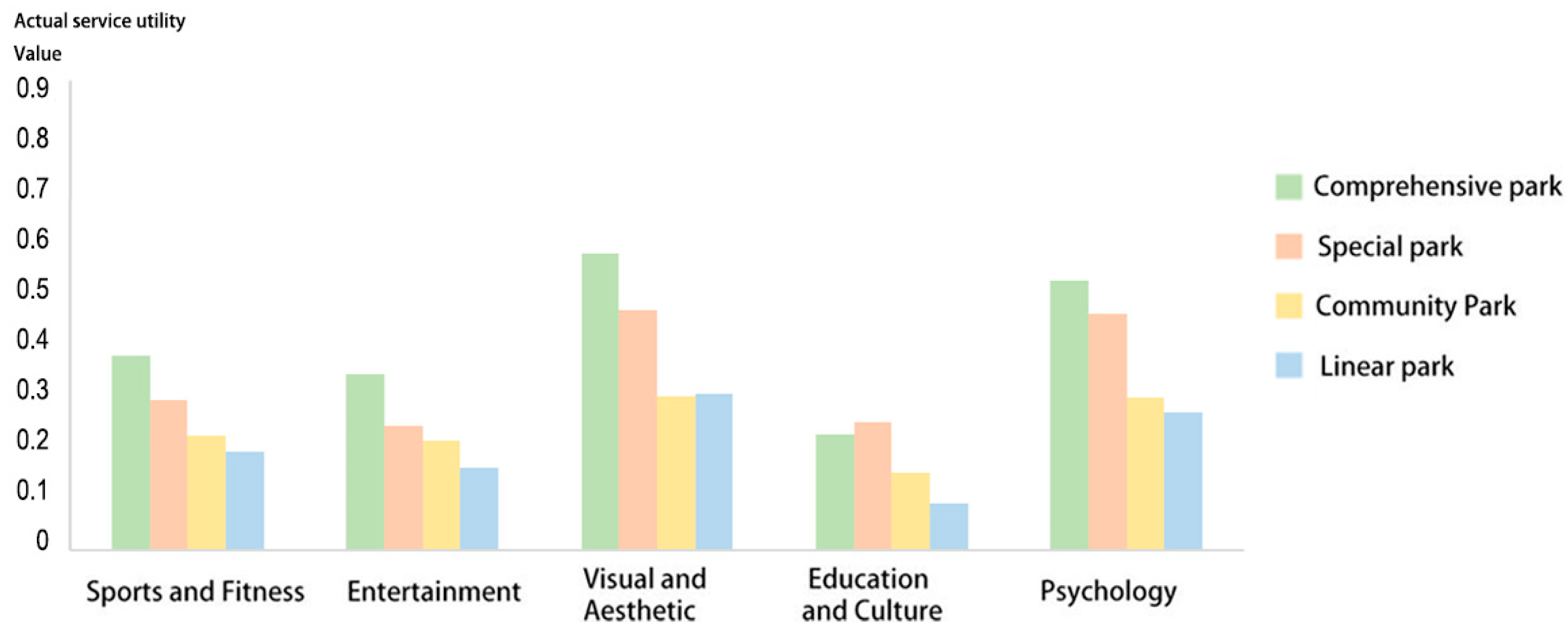

3.1.3. Results of Actual Service Utility

3.2. CES’s Supply and Demand in Shenyang

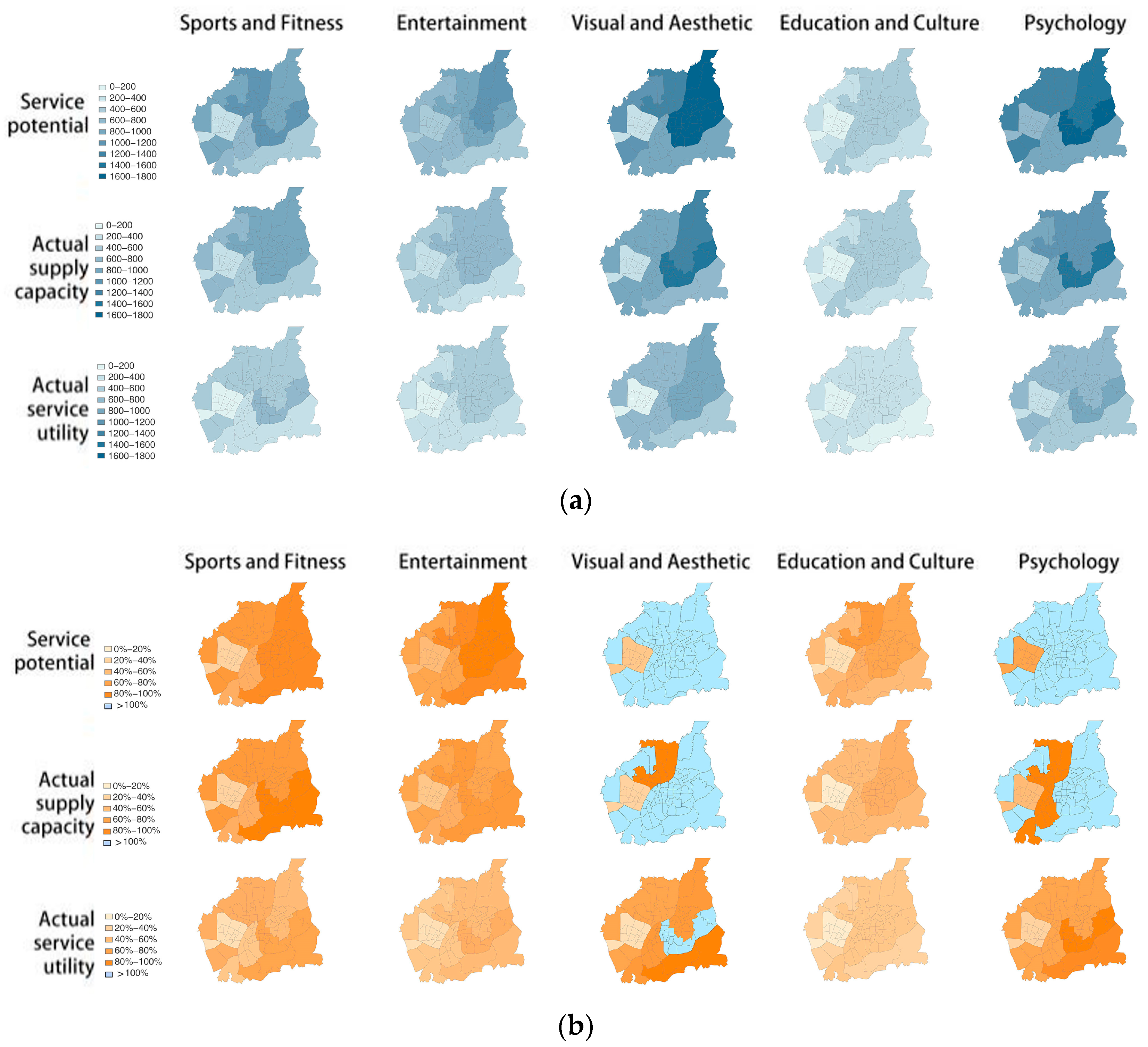

3.2.1. Assessment Based on a Single Index

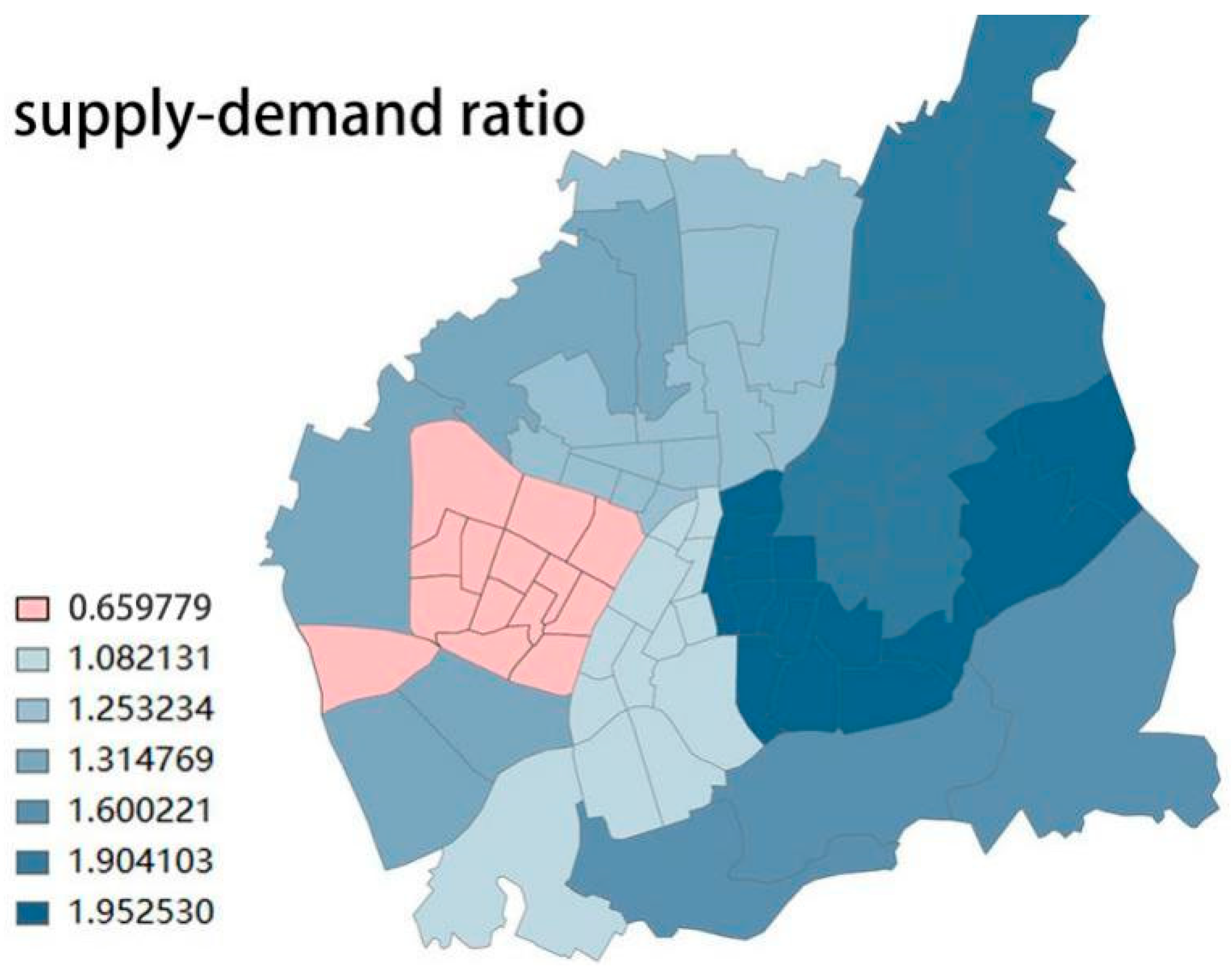

3.2.2. Assessment Based on the Actual Service Utility Evaluation Framework

3.3. Impact of the Framework on the Evaluation Results

3.3.1. CES Supply Capacity Assessment

3.3.2. CES Supply and Demand Assessment

4. Discussion

4.1. Actual CES Service Utility Evaluation Results in Different Park Types

4.2. Urban Green Space: Supply and Demand Results

4.3. Actual Service Utility Evaluation Framework for CES

4.4. Advantages and Limitations of the Framework

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MEA | Millennium Ecosystem Assessment |

| SDGs | Sustainable Development Goals |

| CES | Cultural ecosystem services |

| ESVS | Ecosystem Services Valuation System |

| RECITAL | Urban green space quality assessment tool |

| POST | Public open space quality assessment tool |

| CPAT | Community park assessment tool |

| NEST | Natural environment scoring tool |

| NGST | Neighbourhood green space tool |

| YH | Yuhong District |

| HG | Huanggu District |

| DD | Dadong District |

| TX | Tiexi District |

| HP | Heping District |

| SH | Shenhe District |

| HN | Hunnan District |

Appendix A

| Service Type | Evaluation Criteria | Case |

|---|---|---|

| Entertainment | Area of recreational land | [36] |

| Recreational land area per unit | [37] | |

| Accessibility of the entertainment area | [38] | |

| Area of fishable waters, length of walking and cycling paths for tourists | [35] | |

| Number, type, and quality of entertainment facilities | [39] | |

| Per capita green space area | [40] | |

| Abundance of amusement facilities | [14] | |

| Number of recreational activities | ||

| Parent–child experience | ||

| Parking facilities, convenience of parking | ||

| Guidance facilities | ||

| Location of entrances and exits | ||

| Topography and landforms | [42] | |

| Resource distribution | ||

| Service facilities | ||

| Place function | ||

| Tourism carrying capacity | [43] | |

| Unique natural resources (whales, dolphins, pinnipeds, and otters in public and private reserves) | ||

| Length of stay | [41] | |

| Consumption level | ||

| Spiritual | Viewing range of natural landscapes | [39] |

| Opportunity to enjoy tranquility | ||

| Degree of visibility of green vegetation | ||

| Diversity of vegetation types | ||

| Sense of safety | ||

| Sense of free space | ||

| Inspiration for music and art, belief in God | ||

| Presence of trash, waste, animal droppings, overall view and scenery, presence of vegetation and trees, presence of water bodies, facility design, openness | ||

| Scenic attractiveness | [14] | |

| Scenic interest | ||

| Scenic appeal | ||

| Scenic guidance, whether the landscape can accurately guide | ||

| Greenery coverage | ||

| Number and variety of green plants | ||

| Form of mountains and rivers | [42] | |

| Vegetation landscape | ||

| Natural mechanisms | ||

| Architectural style | ||

| Photo capture points can be uploaded to panoramic views | ||

| Popular Science Education Services | Scientific knowledge from thematic activities, acquisition of scientific knowledge | [43] |

| Entertainment of thematic activities | ||

| Participability of thematic activities | ||

| Species observation | ||

| Sports Services | Fitness facilities, number of fitness facilities meets demand | [14] |

| Greenways | ||

| Facility safety | ||

| Horseback riding, cycling, off-road | ||

| Social Relationship Services | Rain shelters | |

| Benches, pavilions, bathrooms | ||

| Facilitates social activities | ||

| Cultural Perception Services (Religious Beliefs, Cultural Heritage, Spirituality, History, Sense of Place) | Historical events | [42] |

| Local traditions | ||

| Cultural relics | ||

| Interpretation system | ||

| Archeological sites | [43] | |

| Ancestral land | ||

| Sculptures | [44] | |

| Architecture |

| Type of Service | Elements | Quantity Assessment Indicators | Quality Assessment Indicators | Methods |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sports and Fitness | Activity fields (playgrounds, soccer fields, basketball courts, table tennis courts, etc.) | 0: without 1: just one 2: Two or more | (1) Whether it meets the design specification standards (2) Facility accessibility (field of view accessibility, barrier-free) (3) Facility space independence (4) Facility safety (whether it meets safety specifications and standards) (5) The degree of maintenance of the facility (whether there are negative factors such as damage, lack of function, and graffiti) (6) Facility participation (facility opening hours, free of charge) (7) Whether the facilities are complete | Field investigation (according to different facilities compared with relevant norms) |

| Sports and fitness facilities (street fitness equipment) | 0: without 1: just one 2: Two or more | |||

| Facilities for running and hiking | 0: without 1: have | |||

| Water sports and activities | 0: without 1: just one 2: Two or more | |||

| Children’s play facilities | 0: without 1: just one 2: Two or more | |||

| Leisure and entertainment | Catering, restaurants, Concession stand | 0: without 1: just one 2: Two or more | (1) Whether the service carrying capacity can meet the public demand in the green space (2) Satisfaction degree of service quality | Field investigation and Questionnaire survey |

| Stage | 0: without 1: have | (1) Whether the stage volume can meet the needs of the public in the green space (2) Whether the stage has spatial independence (3) Stage maintenance (whether there are negative factors such as damage, function loss, security risks, graffiti Posting) (4) whether the stage is in harmony with the surrounding landscape | Field investigation and Target group visit | |

| Activity places for the elderly (chess and card, Tai Chi) | 0: without 1: just one 2: Two or more | (1) Whether the facilities are perfect (2) The maintenance of the facilities (whether there are negative factors such as damage, function loss, security risks, graffiti Posting) | Field investigation and Target group visit | |

| Walking conditions | 0: without 1: have | (1) The independence of the walking route (to avoid the mixing of people and vehicles) (2) Multi-level and multi-path walking routes (3) Continuity of walking flow lines (loop, barrier-free) | Satellite map, Field investigation | |

| Potential multifunctional space | 0: without 1: just one 2: Two or more | The degree of fit between the potential multi-functional space and the specific activity | Field investigation | |

| Service center | 0: without 1: have | (1) Whether the operation hours, duration and functions of the service center meet the needs (2) Service quality of service center (can be obtained through questionnaire survey) | Field investigation and Questionnaire survey | |

| Visual and aesthetic | Water Features | 0: without 1: just one 2: Two or more | (1) Water feature quality (clear, odor-free) (2) Whether the surrounding environment is in harmony with the water landscape (landscape style, volume) (3) Water feature service duration (artificial water feature (fountain, drop, etc.): opening time and duration, natural water feature: dry season, frost period) accounts for 50% of the annual business hours | Field investigation, Related research |

| Topographic landscape | 0: without 1: have | (1) Whether the micro-terrain landscape conforms to the rule of formal beauty (2) The maintenance level of microtopographic landscape (whether the pavement is damaged, whether the grass is in good condition, etc.) | Field investigation, Human viewing Angle framing, Satellite plan | |

| Plant landscape | 0: without 1: have | (1) Whether the vegetation coverage is greater than 70% (2) Vegetation continuity (plant landscape design and form are coherent, not abrupt) (3) Vegetation skyline (the connection and relief level with the vista and urban skyline) (4) Plant collocation (visual balance, line of sight guidance, matching form in line with formal beauty rule) (5) plant diversity (6) Plant color (seasonal appearance, rich and complementary colors) (7) Plant maintenance (plant pruning, Whether the plant has problems such as poor growth, disease, etc.) | Field investigation, Human viewing Angle framing, Satellite plan | |

| Public art (sculpture, landscape architecture) | 0: without 1: just one 2: Two or more | (1) Whether it conforms to the audience’s aesthetic tendencies (2) the level of public art expression (location (whether it is used for a spot scene or a space line of sight); Whether the ratio between volume and viewing distance is reasonable) (3) Maintenance degree (whether there are negative factors such as damage and graffiti) | Field investigation and Questionnaire survey | |

| Decorative lighting | 0: without 1: have | (1) Decorative lighting opening time (days) (2) Maintenance level of decorative lighting (whether there are negative factors such as damage and lack of functionality) (3) Whether it is harmonious with the surrounding environment (whether there are exposed wires affecting the surrounding landscape effect, whether the lighting facilities are slightly abrupt with the surrounding scenery during the day) (4) safety (whether it can be contacted, whether there are leakage problems, etc.) | Field investigation, and Target population visit | |

| views | 0: without 1: just one 2: Two or more | (1) Accessibility of viewing spots (distance, accessibility) (2) Scenic spot quality (whether it conforms to the beauty in form rule) (3) Whether the scenery changes (with the season, weather and other factors) | Field investigation and Related research | |

| Culture, Science and Education | Public art (sculpture, landscape architecture) | 0: without 1: just one 2: Two or more | (1) Density of public art (2) View of public art appreciation (volume and viewing distance) (3) Maintenance degree (whether there are negative factors such as damage and graffiti) | Satellite map, Field investigation, Questionnaire survey |

| Cultural sites (cultural sites, historical sites, etc.) | 0: without 1: just one 2: Two or more | (1) The degree of preservation of the site (2) the repair level of the site (3) Whether there is site landscape design (4) Participation (whether it is possible to get up close and open for free) | Field investigation, Questionnaire survey | |

| Historical events | 0: without 1: have | (1) The degree of fame of the historical event (whether the public is familiar with it or has a little understanding of it) (2) completeness of the event (whether the event is missing information, such as some characters, sometimes unknowable, etc.) (3) the authenticity of the event (whether there are historical records) | Field investigation (relevant investigation of the uncertain historical content involved, to determine its authenticity) | |

| Science and education content (animal and plant education, history education, culture education) | 0: without 1: have | (1) Whether the content of science and education is comprehensive (whether some fields have not been covered) (2) The degree of participation in science and education services (whether relevant science and education activities have been organized) (3) Participation of science and education content (whether it is free and open, and whether it can be contacted at close range) | Field investigation and Target group visit | |

| spiritual and psychology | Religious cultural content | 0: without 1: have | (1) Whether the religious type is consistent with the regional audience where the green space is located (2) There is no religious conflict when multiple religions coexist in the green space (3) whether there is interference with non-religious believers | Field investigation and Questionnaire survey |

| Sense of Security | 0: without 1: just one 2: Two or more | (1) Whether closed-circuit monitoring is installed (2) Whether there are security personnel (3) Whether there are blind spots in sight (4) Whether there is functional lighting at night | Field investigation and Questionnaire survey | |

| Spatial change (volume, landscape elements, etc.) | 0: without 1: just one 2: Two or more | (1) Whether the spatial changes are obvious (2) Whether the spatial characteristics are clear | Satellite map, Field investigation | |

| Natural perception (Underwoods, waterfront, grassland, etc.) | 0: without 1: just one 2: Two or more | (1) Whether the perceptual elements are prominent (the proportion of the same type of elements (visual elements and non-visual elements) is more than 70%) (2) Quality of perceived elements (landscape quality, element quality) | Field investigation | |

| Social places | 0: without 1: have | (1) Level of maintenance (whether the facilities in the venue are adequate, no Is there damage, lack of function, whether there are negative factors such as graffiti? | Field investigation | |

| Green space infrastructure | Lighting | 0: without 1: have | (1) Whether the functional lighting distribution is reasonable (night activity requirements) (2) Whether the brightness of functional lighting meets the standards (3) Whether functional lighting affects other landscape elements (4) Whether the functional lighting facilities are harmonious with the surrounding landscape | Field investigation, (according to the nature of different sites and different specifications of lighting facilities query lighting specifications) |

| Signage system | 0: without 1: have | (1) Identify whether the information conveyed by the system is clear and clear (2) Whether the design style of the sign system is coordinated with the green space style (3) Whether the sign system is in harmony with other landscape elements and does not interfere with each other | Field investigation and Questionnaire survey | |

| Parking Lot | 0: without 1: have | (1) Whether the number of parking Spaces in the parking lot can meet the needs of the public in the green space (2) Maintenance level (whether there are negative factors such as pavement damage, lack of functions, and graffiti) (3) Whether the parking lot has a clear and standardized parking space plan (4) Whether the flow line of the parking lot is clear and consistent (5) Whether the parking lot guidance system is clear | Field investigation and Questionnaire survey | |

| Public toilet | 0: No public restrooms 1: There is a public bathroom 2: There are two or more public toilets | (1) Whether the public toilet is clean (no obvious odor, no dirt) (2) The maintenance level of public toilets (whether there is damage, whether there is lack of function, whether there are negative factors such as graffiti posted) (3) Whether the bathroom is free (4) Whether the bathroom is fully functional (whether it includes hand washing pool, mother and baby room and other functions) | Field investigation |

References

- Millennium Ecosystem Assessment. Ecosystems and Human Well-Being: Current State and Trends; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Dickinson, D.C.; Hobbs, R.J. Cultural ecosystem services: Characteristics, challenges and lessons for urban green space research. Ecosyst. Serv. 2017, 25, 179–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Peng, J.; Qiu, S.; Liu, Y.; Dong, J.; Zhang, H. Responses of spatial relationships between ecosystem services and the Sustainable Development Goals to urbanization. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 850, 157868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Filho, W.L.; Barbir, J.; Sima, M.; Kalbus, A.; Nagy, G.J.; Paletta, A.; Villamizar, A.; Martinez, R.; Azeiteiro, U.M.; Pereira, M.J.; et al. Reviewing the role of ecosystems services in the sustainability of the urban environment: A multi-country analysis. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 262, 121338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plieninger, T.; Dijks, S.; Oteros-Rozas, E.; Bieling, C. Assessing, mapping, and quantifying cultural ecosystem services at community level. Land Use Policy 2013, 33, 118–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kremer, P.; Hamstead, Z.; Haase, D.; McPhearson, T.; Frantzeskaki, N.; Andersson, E.; Kabisch, N.; Larondelle, N.; Rall, E.L.; Voigt, A.; et al. Key insights for the future of urban ecosystem services research. Ecol. Soc. 2016, 21, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larson, L.R.; Keith, S.J.; Fernandez, M.; Hallo, J.C.; Shafer, C.S.; Jennings, V. Ecosystem services and urban greenways: What’s the public’s perspective? Ecosyst. Serv. 2016, 22, 111–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Ding, K. Optimization Strategy for Parks and Green Spaces in Shenyang City: Improving the Supply Quality and Accessibility. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 4443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larondelle, N.; Lauf, S. Balancing demand and supply of multiple urban ecosystem services on different spatial scales. Ecosyst. Serv. 2016, 22, 18–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krellenberg, K.; Artmann, M.; Stanley, C.; Hecht, R. What to do in, and what to expect from, urban green spaces—Indicator-based approach to assess cultural ecosystem services. Urban For. Urban Green. 2021, 59, 126986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegetschweiler, K.T.; de Vries, S.; Arnberger, A.; Bell, S.; Brennan, M.; Siter, N.; Olafsson, A.S.; Voigt, A.; Hunziker, M. Linking demand and supply factors in identifying cultural ecosystem services of urban green infrastructures: A review of European studies. Urban For. Urban Green. 2017, 21, 48–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabisch, N.; Kraemer, R. Physical activity patterns in two differently characterised urban parks under conditions of summer heat. Environ. Sci. Policy 2020, 107, 56–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Tao, Z. Research on the Cultural Service Quality of Urban Park Ecosystems. J. Urban Sci. 2022, 2, 58–68. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Nigussie, S.; Liu, L.; Yeshitela, K. Indicator development for assessing recreational ecosystem service capacity of urban green spaces—A participatory approach. Ecol. Indic. 2021, 121, 107026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flowers, E.P.; Timperio, A.; Hesketh, K.D.; Veitch, J. Examining the Features of Parks That Children Visit During Three Stages of Childhood. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Artmann, M.; Chen, X.; Iojă, C.; Hof, A.; Onose, D.; Poniży, L.; Lamovšek, A.Z.; Breuste, J. The role of urban green spaces in care facilities for elderly people across European cities. Urban For. Urban Green. 2017, 27, 203–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, P.-J. Effects of the built and social features of urban greenways on the outdoor activity of older adults. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2020, 204, 103929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, Y.; Li, D.; Wu, C.; Wu, H. Urban park facility use and intensity of seniors’ physical activity—An examination combining accelerometer and GPS tracking. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2021, 205, 103950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knobel, P.; Dadvand, P.; Alonso, L.; Costa, L.; Español, M.; Maneja, R. Development of the urban green space quality assessment tool (RECITAL). Urban For. Urban Green. 2021, 57, 126895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giles-Corti, B.; Broomhall, M.H.; Knuiman, M.; Collins, C.; Douglas, K.; Ng, K.; Lange, A.; Donovan, R.J. Increasing walking. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2005, 28, 169–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gidlow, C.J.; Ellis, N.J.; Bostock, S. Development of the Neighbourhood Green Space Tool (NGST). Landsc. Urban Plan. 2012, 106, 347–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gidlow, C.; van Kempen, E.; Smith, G.; Triguero-Mas, M.; Kruize, H.; Gražulevičienė, R.; Ellis, N.; Hurst, G.; Masterson, D.; Cirach, M.; et al. Development of the natural environment scoring tool (NEST). Urban For. Urban Green. 2018, 29, 322–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, D.J.; Hardwicke, J.; Hill, K.M. Delapré Walk project: Are signposted walking routes an effective intervention to increase engagement in urban parks?—Natural experimental study. Health Place 2023, 83, 103049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lis, A.; Zienowicz, M.; Kukowska, D.; Zalewska, K.; Iwankowski, P.; Shestak, V. How to light up the night? The impact of city park lighting on visitors’ sense of safety and preferences. Urban For. Urban Green. 2023, 89, 128124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weitowitz, D.C.; Panter, C.; Hoskin, R.; Liley, D. Parking provision at nature conservation sites and its implications for visitor use. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2019, 190, 103597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehury, R.K.; Swayne, M.R.E.; Calzo, J.P.; Felner, J.K.; Welsh Carroll, M. Developing evidence for building sanitation justice: A multi methods approach to understanding public restroom quantity, quality, accessibility, and user experiences. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0288525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, G.; Liu, Y.; Hu, J.; Cao, X. The effect of tourist-to-tourist interaction on tourists’ behavior: The mediating effects of positive emotions and memorable tourism experiences. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2023, 55, 161–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaei, N.; Huang, W.-J.; Hung, K. Tourist’s achievement emotions and memorable experience in visiting the Middle East. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2023, 47, 101129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Xie, G.; Lu, C.; Xu, J. Involvement of ecosystem service flows in human wellbeing based on the relationship between supply and demand. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2016, 36, 3096–3102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagstad, K.J.; Johnson, G.W.; Voigt, B.; Villa, F. Spatial dynamics of ecosystem service flows: A comprehensive approach to quantifying actual services. Ecosyst. Serv. 2013, 4, 117–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagstad, K.J.; Villa, F.; Batker, D.; Harrison-Cox, J.; Voigt, B.; Johnson, G.W. From theoretical to actual ecosystem services: Mapping beneficiaries and spatial flows in ecosystem service assessments. Ecol. Soc. 2014, 19, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, J.; Chen, W.; He, X. The latest progress in ecosystem service flow research methods. Chin. J. Appl. Ecol. 2018, 29, 335–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanon, S.; Hein, T.; Douven, W.; Winkler, P. Quantifying ecosystem service trade-offs: The case of an urban floodplain in Vienna, Austria. J. Environ. Manag. 2012, 111, 159–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, S.E.; Handley, J.F.; Ennos, A.R.; Pauleit, S.; Theuray, N.; Lindley, S.J. Characterising the urban environment of UK cities and towns: A template for landscape planning. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2008, 87, 210–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larondelle, N.; Haase, D. Urban ecosystem services assessment along a rural-urban gradient: A cross-analysis of European cities. Ecol. Indic. 2013, 29, 179–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, O.; Tratalos, J.A.; Armsworth, P.R.; Davies, R.G.; Fuller, R.A.; Johnson, P.; Gaston, K.J. Who benefits from access to green space? A case study from Sheffield, UK. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2007, 83, 187–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radford, K.G.; James, P. Changes in the value of ecosystem services along a rural–urban gradient: A case study of Greater Manchester, UK. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2013, 109, 117–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haase, D.; Schwarz, N.; Strohbach, M.; Kroll, F.; Seppelt, R. Synergies, Trade-offs, and Losses of Ecosystem Services in Urban Regions: An Integrated Multiscale Framework Applied to the Leipzig-Halle Region, Germany. Ecol. Soc. 2012, 17, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, P.; Zhang, S.; Gong, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Hou, H. A crowd-sourced valuation of recreational ecosystem services using mobile signal data applied to a restored wetland in China. Ecol. Econ. 2022, 192, 107249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, H.; Yang, P. Study on Rural Rejuvenation Strategy Based on Cultural Ecosystem Services: A Case Study of Longwang Village, Beibei District, Chongqing. Landsc. Archit. Acad. J. 2022, 39, 39–47. [Google Scholar]

- Nahuelhual, L.; Vergara, X.; Kusch, A.; Campos, G.; Droguett, D. Mapping ecosystem services for marine spatial planning: Recreation opportunities in Sub-Antarctic Chile. Mar. Policy 2017, 81, 211–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huai, S.; Chen, F.; Liu, S.; Canters, F.; Van de Voorde, T. Using social media photos and computer vision to assess cultural ecosystem services and landscape features in urban parks. Ecosyst. Serv. 2022, 57, 101475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Zhu, L.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Lu, L. A Sustainable Evaluation Method for a Tourism Public Wayfinding System: A Case Study of Shanghai Disneyland Resort. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, L.; Chen, J.; Xie, Y. Assessment of landscape resource using the scenic beauty estimation method at compound ecological system. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 28, 5892–5899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, J.; Chen, N.; Liu, M.; Chen, W.; He, X. An analysis of the co-benefits of the supply-demand for multiple ecosystem services for guiding sustainable urban development. Ecol. Indic. 2023, 147, 109917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zwierzchowska, I.; Hof, A.; Iojă, I.-C.; Mueller, C.; Poniży, L.; Breuste, J.; Mizgajski, A. Multi-scale assessment of cultural ecosystem services of parks in Central European cities. Urban For. Urban Green. 2018, 30, 84–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, J.; Grohmann, D. Integrating community gardens into urban parks: Lessons in planning, design and partnership from Seattle. Urban For. Urban Green. 2018, 33, 46–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nesbitt, L.; Meitner, M.J.; Girling, C.; Sheppard, S.R.J.; Lu, Y. Who has access to urban vegetation? A spatial analysis of distributional green equity in 10 US cities. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2019, 181, 51–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafer, C.S.; Lee, B.K.; Turner, S. A tale of three greenway trails: User perceptions related to quality of life. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2000, 49, 163–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breyne, J.; Dufrêne, M.; Maréchal, K. How integrating ‘socio-cultural values’ into ecosystem services evaluations can give meaning to value indicators. Ecosyst. Serv. 2021, 49, 101278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottwald, S.; Albert, C.; Fagerholm, N. Combining sense of place theory with the ecosystem services concept: Empirical insights and reflections from a participatory mapping study. Landsc. Ecol. 2021, 37, 633–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haase, D.; Larondelle, N.; Andersson, E.; Artmann, M.; Borgström, S.; Breuste, J.; Gomez-Baggethun, E.; Gren, Å.; Hamstead, Z.; Hansen, R.; et al. A Quantitative Review of Urban Ecosystem Service Assessments: Concepts, Models, and Implementation. Ambio 2014, 43, 413–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaligot, R.; Hasler, S.; Chenal, J. National assessment of cultural ecosystem services: Participatory mapping in Switzerland. Ambio 2019, 48, 1219–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, C.; Chung, W. The impact of park environmental characteristics and visitor perceptions on visitor emotions from a cross-cultural perspective. Urban For. Urban Green. 2024, 102, 128575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Wu, Q.; Lyu, J. Which affects park satisfaction more, environmental features or spatial pattern? Landsc. Ecol. 2025, 40, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, H.; Kellar, I.; Conner, M.; Gidlow, C.; Kelly, B.; Nieuwenhuijsen, M.; McEachan, R. Associations between park features, park satisfaction and park use in a multi-ethnic deprived urban area. Urban For. Urban Green. 2019, 46, 126485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, K.M.A.; Satterfield, T.; Goldstein, J. Rethinking ecosystem services to better address and navigate cultural values. Ecol. Econ. 2012, 74, 8–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haines-Young, R.; Potschin-Young, M. Revision of the Common International Classification for Ecosystem Services (CICES V5.1): A Policy Brief. One Ecosyst. 2018, 3, 27108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bidegain, Í.; López-Santiago, C.A.; González, J.A.; Martínez-Sastre, R.; Ravera, F.; Cerda, C. Social Valuation of Mediterranean Cultural Landscapes: Exploring Landscape Preferences and Ecosystem Services Perceptions through a Visual Approach. Land 2020, 9, 390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghermandi, A. Geolocated social media data counts as a proxy for recreational visits in natural areas: A meta-analysis. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 317, 115325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oviedo, M.; Drescher, M.; Dean, J. Urban greenspace access, uses, and values: A case study of user perceptions in metropolitan ravine parks. Urban For. Urban Green. 2022, 70, 127522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.; Zhu, C.; Lin, L.; Wang, C.; Jin, C.; Cao, J.; Li, T.; Su, C. Assessing the Cultural Ecosystem Services Value of Protected Areas Considering Stakeholders’ Preferences and Trade-Offs-Taking the Xin’an River Landscape Corridor Scenic Area as an Example. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 13968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walden-Schreiner, C.; Leung, Y.-F.; Tateosian, L. Digital footprints: Incorporating crowdsourced geographic information for protected area management. Appl. Geogr. 2018, 90, 44–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkins, E.J.; Howe, P.D.; Smith, J.W. Social media reveal ecoregional variation in how weather influences visitor behavior in U.S. National Park Service units. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 2403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dube, K.; Nhamo, G. Evidence and impact of climate change on South African national parks. Potential implications for tourism in the Kruger National Park. Environ. Dev. 2020, 33, 100485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB19272; Safety for Outdoor Body-Building Equipment—General Requirements (GB 19272-2024). Standardization Administration of China (SAC): Beijing, China, 2024. Available online: https://www.gb-gbt.com/PDF/Chinese.aspx/GB19272-2024 (accessed on 12 December 2025).

| Assessment Criteria | Score |

|---|---|

| The element does not exist. | 0 |

| The element which exists but does not meet the use quantity or volume. | 0.6 |

| The element which exists and meets the use quantity or volume, respectively. | 1 |

| Types of Parks | Statistical Type | Sports Fitness | Recreation | Visual Aesthetics | Culture and Education | Psychological |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| comprehensive parks | Average | 0.61 | 0.53 | 0.84 | 0.31 | 0.80 |

| SD | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.05 | |

| special Parks | Average | 0.48 | 0.45 | 0.74 | 0.40 | 0.75 |

| SD | 0.08 | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.09 | 0.02 | |

| Community Park | Averages | 0.46 | 0.42 | 0.60 | 0.31 | 0.69 |

| SD | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.07 | 0.02 | |

| Linear Park | Averages | 0.42 | 0.37 | 0.69 | 0.21 | 0.65 |

| SD | 0.06 | 0.04 | 0.06 | 0.02 | 0.04 |

| Types of Parks | Statistical Type | Sports Fitness | Recreation | Visual Aesthetics | Culture and Education | Psychological |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Comprehensive Park | Average | 0.49 | 0.41 | 0.74 | 0.28 | 0.68 |

| SD | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.01 | |

| Special Park | Average | 0.37 | 0.33 | 0.64 | 0.31 | 0.64 |

| SD | 0.06 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.03 | |

| Community Park | Averages | 0.36 | 0.36 | 0.49 | 0.24 | 0.51 |

| SD | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.07 | 0.05 | 0.03 | |

| Linear Park | Averages | 0.34 | 0.28 | 0.55 | 0.16 | 0.48 |

| SD | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.01 | 0.03 |

| Types of Parks | Statistical Type | Sports Fitness | Recreation | Visual Aesthetics | Culture and Education | Psychological |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Comprehensive Park | Average | 0.38 | 0.34 | 0.58 | 0.22 | 0.52 |

| SD | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.02 | |

| Special Park | Average | 0.29 | 0.24 | 0.47 | 0.25 | 0.46 |

| SD | 0.05 | 0.02 | 0.06 | 0.05 | 0.05 | |

| Community Park | Averages | 0.22 | 0.21 | 0.30 | 0.15 | 0.30 |

| SD | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.04 | |

| Linear Park | Averages | 0.19 | 0.16 | 0.30 | 0.09 | 0.27 |

| SD | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.02 |

| DD | HG | HN | HP | SH | TX | YH | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CES Supply (km2) | 21.1 | 17.7 | 11.5 | 13.4 | 26.8 | 8.9 | 16.7 |

| CES Demand (km2) | 11.1 | 14.2 | 7.2 | 12.4 | 13.7 | 13.5 | 12.7 |

| CES Supply–Demand Ratio | 190% | 125% | 160% | 108% | 195% | 66% | 131% |

| Municipal District | Sport | Recreation | Aesthetic | Education and Culture | Psychological | Average Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Service potential (quantity) | DD | 86% | 92% | 151% | 64% | 134% | 105% |

| HP | 73% | 64% | 91% | 52% | 88% | 73% | |

| HG | 82% | 62% | 120% | 35% | 118% | 84% | |

| HN | 52% | 50% | 80% | 41% | 77% | 60% | |

| SH | 80% | 70% | 130% | 46% | 135% | 92% | |

| TX | 30% | 30% | 28% | 11% | 48% | 29% | |

| YH | 72% | 49% | 89% | 34% | 99% | 68% | |

| Actual supply capacity (quality) | DD | 73% | 67% | 123% | 50% | 103% | 83% |

| HP | 57% | 51% | 70% | 36% | 72% | 57% | |

| HG | 68% | 52% | 106% | 32% | 95% | 71% | |

| HN | 38% | 40% | 74% | 35% | 66% | 51% | |

| SH | 65% | 54% | 112% | 40% | 104% | 75% | |

| TX | 20% | 26% | 19% | 6% | 32% | 20% | |

| YH | 57% | 44% | 75% | 30% | 77% | 57% | |

| Actual service utility (basic service) | DD | 48% | 46% | 79% | 35% | 65% | 55% |

| HP | 37% | 34% | 48% | 27% | 49% | 39% | |

| HG | 47% | 33% | 70% | 20% | 62% | 47% | |

| HN | 28% | 28% | 52% | 26% | 45% | 36% | |

| SH | 45% | 37% | 73% | 27% | 68% | 50% | |

| TX | 12% | 13% | 12% | 4% | 16% | 11% | |

| YH | 37% | 28% | 47% | 18% | 47% | 35% |

| Park Type | Potential Assessment | Actual Supply Capacity | Actual Supply Utility | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sport and Fitness | Recreation | Aesthetic | Education and Culture | Psychological | Effect * | Sport and Fitness | Recreation | Aesthetic | Education and Culture | Psychological | Effect * | Sport and Fitness | Recreation | Aesthetic | Education and Culture | Psychological | Effect * | |

| Comprehensive park | 0.61 | 0.53 | 0.84 | 0.31 | 0.8 | 38% | 0.49 | 0.41 | 0.74 | 0.28 | 0.68 | 16% | 0.38 | 0.34 | 0.58 | 0.22 | 0.52 | 21% |

| Special class park | 0.48 | 0.45 | 0.74 | 0.4 | 0.75 | 44% | 0.37 | 0.33 | 0.64 | 0.31 | 0.64 | 20% | 0.29 | 0.24 | 0.47 | 0.25 | 0.46 | 26% |

| Community park | 0.46 | 0.42 | 0.6 | 0.31 | 0.69 | 50% | 0.36 | 0.36 | 0.49 | 0.24 | 0.51 | 21% | 0.22 | 0.21 | 0.3 | 0.15 | 0.3 | 40% |

| Linear park | 0.42 | 0.37 | 0.69 | 0.21 | 0.65 | 53% | 0.34 | 0.28 | 0.55 | 0.16 | 0.48 | 22% | 0.19 | 0.16 | 0.3 | 0.09 | 0.27 | 44% |

| Municipal District | Sport | Recreation | Aesthetic | Education and Culture | Psychological | Average Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Service potential (quantity) | DD | 55% | 51% | 21% | 67% | 30% | 45% |

| HP | 41% | 49% | 27% | 59% | 30% | 41% | |

| HG | 49% | 61% | 25% | 78% | 27% | 48% | |

| HN | 52% | 53% | 26% | 62% | 29% | 44% | |

| SH | 59% | 64% | 33% | 76% | 31% | 53% | |

| TX | 55% | 54% | 58% | 84% | 28% | 56% | |

| YH | 45% | 63% | 32% | 74% | 25% | 48% | |

| Actual supply capacity (quality) | DD | 15% | 27% | 18% | 21% | 23% | 21% |

| HP | 23% | 20% | 23% | 30% | 17% | 22% | |

| HG | 17% | 17% | 12% | 9% | 19% | 16% | |

| HN | 27% | 21% | 7% | 13% | 15% | 16% | |

| SH | 19% | 23% | 14% | 14% | 23% | 19% | |

| TX | 32% | 15% | 32% | 46% | 33% | 30% | |

| YH | 21% | 9% | 15% | 10% | 22% | 17% | |

| Actual service utility (basic service) | DD | 34% | 31% | 36% | 30% | 36% | 34% |

| HP | 35% | 34% | 32% | 26% | 32% | 32% | |

| HG | 31% | 36% | 34% | 37% | 34% | 34% | |

| HN | 27% | 29% | 30% | 28% | 31% | 30% | |

| SH | 31% | 31% | 35% | 33% | 35% | 33% | |

| TX | 40% | 48% | 37% | 31% | 49% | 44% | |

| YH | 36% | 37% | 37% | 39% | 39% | 38% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zhang, Z.; Yao, J.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, W.; Yu, J.; He, X. Assessing the Supply and Demand for Cultural Ecosystem Services in Urban Green Space Based on Actual Service Utility to Support Sustainable Urban Development. Sustainability 2026, 18, 98. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010098

Zhang Z, Yao J, Zhou Y, Chen W, Yu J, He X. Assessing the Supply and Demand for Cultural Ecosystem Services in Urban Green Space Based on Actual Service Utility to Support Sustainable Urban Development. Sustainability. 2026; 18(1):98. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010098

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Zhenkuan, Jing Yao, Yuan Zhou, Wei Chen, Jinghua Yu, and Xingyuan He. 2026. "Assessing the Supply and Demand for Cultural Ecosystem Services in Urban Green Space Based on Actual Service Utility to Support Sustainable Urban Development" Sustainability 18, no. 1: 98. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010098

APA StyleZhang, Z., Yao, J., Zhou, Y., Chen, W., Yu, J., & He, X. (2026). Assessing the Supply and Demand for Cultural Ecosystem Services in Urban Green Space Based on Actual Service Utility to Support Sustainable Urban Development. Sustainability, 18(1), 98. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010098