1. Introduction

In the age of digitalization, the internet has positioned itself as a central element in contemporary daily life. A study by Siteefy [

1] projects approximately 1.1 billion websites worldwide in 2024; however, only 18% of these are active. Despite the undeniable benefits that digital services offer for personal and professional spheres, the significant environmental impact of the internet is often overlooked [

2]. The primary contributing factors include high energy consumption, the generation of data waste, and the CO

2 emissions resulting from the operation and utilization of digital infrastructures [

2] (p. 2). Estimates from the early 2010s indicate that the internet is responsible for approximately 2% of global CO

2 emissions [

3]. More recently this estimation has been updated to almost 4% [

4] when including the hardware dimension, thereby rendering its environmental footprint comparable to that of the aviation industry [

5].

A critical determinant of the internet’s energy consumption is the existence of data centers, which require considerable energy for uninterrupted power supply, air conditioning, and cooling [

6]. Masanet et al. [

7] estimate that data centers globally consume around 200 terawatt hours (TWh) annually, which constitutes nearly one percent of global energy consumption as of 2020. Projections indicate a further increase in the coming years driven by the sustained growth in data traffic and data volumes [

8]. Furthermore, based on their worst-case scenario analysis, Andrae and Edler [

8] forecast that information and communication technology (ICT) could comprise up to 51% of global electricity consumption by 2030, potentially generating up to 23% of global greenhouse gas emissions.

Specifically, the growing data volume associated with contemporary websites constitutes a significant factor in energy consumption. This can be attributed to the escalating complexity and media-richness of modern websites [

2] (p. 28), [

9]. The average data size of a website (approximately 2655 kilobytes in October 2024) has increased significantly over the last five years.

Considering an average value of 1.8 kWh per gigabyte (GB) of data consumed, as established by Andrae and Edler [

8], the energy consumption per visit to a typical website is calculated at 0.004779 kWh, translating to emissions of approximately 1.8 g of CO

2 per visit. Together with Siteefy [

1]’s estimate of 198 million active websites worldwide, this results in annual CO

2 emissions of over 43 billion kilograms for all websites worldwide.

The domain of sustainable web design currently lacks clearly defined guidelines and standards for web designers and developers to effectively implement sustainable practices [

10].

Frick [

11] (p. 55) posits that the fundamental principles of sustainable web design are to optimize the efficiency of all web applications while simultaneously mitigating their carbon footprint, thereby reducing their environmental impact. The foundational principles for sustainable web design include:

More sustainable components and green hosting

Findability, content strategy, and search engine optimization

Design and user experience

Web performance optimization (WPO)

User experience (UX) and apposite design are integral to sustainable web design. Meticulously planned UX design can institute clear structural frameworks and efficient user guidance, which may enhance user satisfaction and reduce the environmental impact of websites [

12]. The subsequent discussion delineates how UX design can be effectively aligned with the sustainability of websites.

According to Hain [

12], unambiguous navigation and simple interaction design are pivotal in minimizing a website’s energy consumption. Easy information retrieval and access correspond to a reduction in the volume of data transfers. This leads to a decrease in electricity consumption at both the client (user) and server level, given that the user ideally attains the target destination with a minimal number of clicks, thereby limiting the elements or pages loadedRef. [

12], Ref. [

13] (p. 30).

Greenwood [

13] (pp. 29–31) contends that robust information architecture (IA) and UX design facilitate the avoidance of superfluous page views. He posits that convoluted and inefficient structures precipitate extended loading times and poor user experiences. Caching measures constitute a mechanism that can aid in the reduction in energy consumption. Users should not encounter unnecessary intermediate steps, such as gateway pages, as these complicate the navigation towards the requisite information.

Greenwood [

13] (p. 32) further recommends the reduction in content to ensure more sustainable user guidance. This underscores the relevance of consistent content review and adjustment, a process Frick [

11] (pp. 114–116) refers to as a content audit. This allows for the identification and optimization of obsolete and redundant content, which in turn ensures an efficient and sustainable information architecture.

Greenwood [

13] (p. 33) argues that both the user journey and exit behavior (bounce) merit systematic analysis. They enable the determination of whether users rapidly locate the requisite information, resulting in a desirable exit, or if the bounce is attributable to frustration induced by unstructured guidance or protracted loading times.

The preceding discussion has demonstrated that sustainable web design confers not only ecological but also strategic advantages for organizations. These advantages empower them to reinforce their environmentally conscious initiatives and digital presence. This section consolidates the positive effects of sustainable web design as previously described within the context of digital marketing.

The aforementioned measures imply that sustainable UX design reduces a website’s environmental impact while simultaneously contributing to the attainment of organizational objectives. An appealing user experience characterized by intuitive user journeys and rapid loading times can not only ameliorate CO

2 emissions but also yield higher conversion rates and customer satisfaction [

13] (p. 71). Beyer [

2] (p. 20) concurs, further noting that strategies to optimize digital sustainability frequently correlate with an enhanced user experience, and Kovacevic [

14] asserts that sustainable web design facilitates positive brand positioning for companies.

Kovacevic [

14] explains that users exhibit a growing preference for organizations that transparently disclose the sustainability efforts associated with their digital activities. She further explains that a sustainable website utilizing green hosting can reinforce brand identity and foster customer trust. Forster [

15] affirms this notion, emphasizing that consumers demonstrate a progressively positive disposition toward companies with sustainability ambitions. Therefore, Forster [

15] suggests that the prominence of environmentally friendly initiatives in digital marketing can resonate with a broader audience and solidify customer loyalty.

Beyer [

2] (pp. 21–23) notes that seals, certifications, and labels constitute an increasingly recognized vehicle for communicating the sustainable attributes of websites. He adds that a deficiency of uniform standards for these endorsements currently persists. While credible and transparent providers exist, troublesome methodologies are also present. This discrepancy is particularly evident when seals are conferred in exchange for monetary compensation rather than being predicated upon demonstrable efforts towards CO

2 emissions reduction.

This can lead to perceived digital greenwashing, which represents the application of the greenwashing concept specifically to the digital products and services created or utilized by an entity [

16]. Frick [

16] offers seals as an example of potential digital greenwashing.

To elicit insights on specific elements of sustainable web design, a Scopus search utilizing the terms “sustainable/sustainability/green”, “web/UX”, and “design” has been conducted. It resulted in several studies that focus on specific websites and their current status of sustainability [

17] and how it can be improved [

18]. In the context of this study, however, only those studies are of interest where specific measures of sustainable web design are considered independent of specific applications.

Of particular interest is the review study by Wimalasena and Arambepola [

19], who in their article identify 23 studies on the topic of sustainable web design. They in particular divide the sustainability practices into three phases, i.e., design, development, and deployment. In the design phase, they identify eco-friendly UI and UX design, efficient resource usage, and page load optimization [

20] as aspects discussed in the literature. The latter two aspects can indirectly be made measurable by page loading times. The first aspect, while focused primarily on pattern libraries, can be extended to the realization of a minimalistic vs. a sophisticated site design [

18].

In the development phase, they identify more eco-efficient practices and tools [

21], while in the deployment phase, the aspect of green, i.e., energy-efficient, hosting is considered aside from resource optimization in general.

As the review of the existing literature further yielded several studies from the domain of sustainable web design, which discuss additional aspects, these studies and aspects are summarized in the synopsis in

Table 1.

While fast loading times, color schemes, and the design can be evaluated by website visitors directly, green hosting or the use of more energy-efficient practices and tools are difficult to evaluate for front-end users. Thus, if the company is interested in utilizing their sustainability efforts in a marketing context, these efforts need to be advertised either through the use of seals, certificates, and labels or, alternatively, by providing website visitors with a special information page about these endeavors [

39]. These digital communication tools then act like virtual nudges of consumers towards more sustainable website alternatives [

40].

Mat Nawi et al. [

41] consider the current state of adoption of green information and communication technologies in general by employing a business-centric perspective. This study, in contrast, adopts an approach comparable to Shafiee et al. [

42], which is consumer-centric and focuses on specifics of sustainable web design.

The aspects chosen for this study are strongly aligned with the study by Kiourtis et al. [

23]. They combine aspects directly visible to the website visitor, i.e., the design structure of the website and fast loading times, with aspects not directly inherently visible but communicated via the use of tools like seals for green hosting and overall sustainability performance or additional information pages that communicate digital sustainability endeavors by the company in detail. The last aspect can be understood like an umbrella term summarizing the multitude of not directly visible aspects of green web design. In detail, the following five aspects are considered in the context of the following study:

Website design: Minimalistic vs. non-minimalistic;

Loading times: Fast vs. slow;

Green hosting: Communicated to the visitor;

Sustainability seals;

Information pages on sustainability endeavors.

Discrete choice experiments (DCEs) are a robust tool for eliciting participants’ preference structures [

43]. While other approaches, in particular those resulting from the TAM, focus on the intention to use or buy products, discrete choice experiments are suitable tools to be used in situations where the utility of a good or service results from the utility of a set of characteristics or attributes thereof [

44]. Thus, compared to fixed models like the UTAUT2, choice experiments are more flexible in their use and regarding their applications.

DCEs are based on three theoretical foundations. Random utility maximization [

45] posits that consumer preferences are not deterministic but determined by a random variable. The hedonic theory, or, in detail, the consumption theory by Lancaster [

44], posits that the utility of a product results from the utility generated by its characteristics or attributes. Finally, microeconomic consumer choice theory posits that consumer value assignments and preferences can be deduced from their choices.

To elicit the status quo of the use of choice experiments in the context of web design, a Scopus search utilizing the terms “web/UX”, “design”, and “choice experiment” has been realized. While multiple studies have been conducted measuring the perception of web design features, relatively few studies have employed discrete choice experiments.

Among those, the study by Huertes-Garcia et al. [

46] provides a cross-cultural study about the perception of website content and quality. Comparatively, the present study similarly considers website content and quality perception but focuses on the specific context of sustainable design options rather than cultural differences.

Figl et al. [

47] recently provided initial insights into the relevance of prototypicality, i.e., the degree to which a website meets user expectations. While this study does not investigate prototypicality, it partially pursues a comparable objective, i.e., identifying the specific characteristics of sustainable web design that shape the perception of sustainability. The present study therefore examines a specialized application of the concept investigated by Figl et al. [

47].

Finally, the study by Galletta et al. [

38] is the one closest to the current study. In

Section 2, the reduction in loading times is identified as one option of sustainable web design, or rather, the reasons for faster loading times result from sustainable design options. Thus, Galletta et al. [

38] serves as a conceptual precursor to the current work, examining loading times in a general context rather than specifically within the domain of sustainable web design.

Otherwise, currently no study has resulted that considers discrete choice experiments in the context of sustainable web or UX design and thus, provides comprehensive insights into consumers’ perceived utility and preferences for respective elements.

Consequently, by considering the five aspects of sustainable web design deduced from the literature above in the context of a discrete choice experiment, this study provides valuable insights on the perception by consumers.

Since this study systematically analyzes how sustainable web design affects user perception and investigates the potential of communication strategies employed to convey sustainability efforts and foster awareness, the central research question is:

“How do sustainable web design practices influence the effectiveness and perception of websites, and what implications does this have for digital marketing communication?”

Following from the exploratory nature of this study, the formulation of research hypotheses has been avoided. Instead, for the qualitative expert interviews, sub-research questions are formulated. The quantitative analysis of the DCE data follows in directly answering the central research question.

In summary, this study contributes to the literature in three principal ways. It considers the topic of green and sustainable web design from a consumer-centric perspective, trying to elicit the relevance of multiple aspects of sustainable web design in their decision-making, i.e., choices. It realizes this objective by utilization of a discrete choice experiment.

Second, it expands studies like Galletta et al. [

38] by considering multiple aspects of website design at the same time in the context of the utilized discrete choice experiment. By use of a comprehensive model, interactions between different aspects of sustainable web design are thus implicitly considered. Finally, this study utilizes a preliminary round of expert interviews to provide added validation of the attributes used in the discrete choice experiment. Thus, the study combines a theoretical motivation with a practical expert perspective and a consumer perspective. Thus, it combines the best aspects of studies like Galletta et al. [

38] and Hansen et al. [

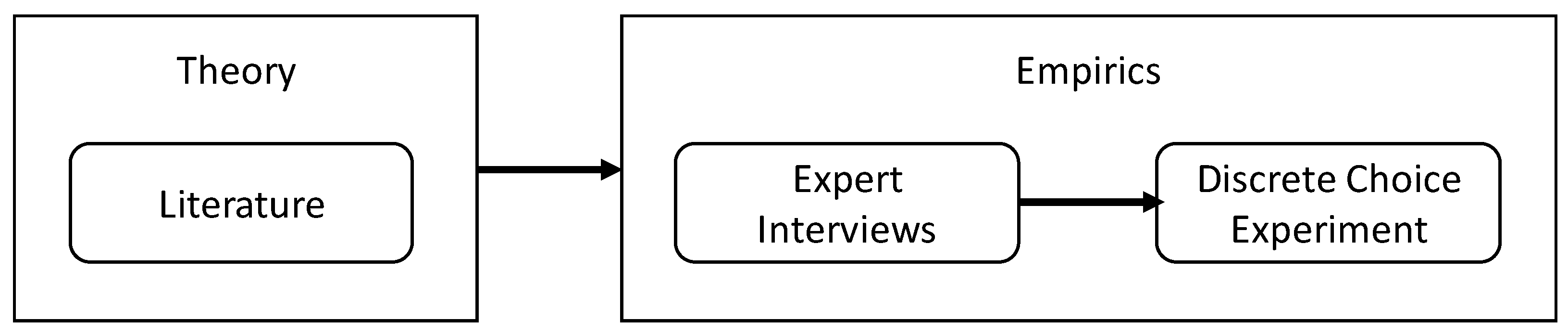

48], even if the qualitative expert interviews primarily act as a precursor to the discrete choice experiment.

To achieve these objectives,

Section 2 introduces the research design and details the two parts of the adopted mixed-method design. The results of both parts of the mixed-method study are presented in

Section 3, and

Section 4 concludes by formulating recommendations for practitioners and discussing limitations of the current study.

3. Results

3.1. Preliminary Expert Interviews

The expert interviews were anonymized and transcribed following standard rules [

55]. After the conclusion of the transcription, following assurances to the interview partners, the original audio files were destroyed, and the analysis was carried out based on the transcripts alone using the software package MaxQDA (version 24.6).

The evaluation as well followed the practices for the deductive analysis of interview materials established by Mayring [

55]. A deductive approach has been adopted since the categories are predefined via the research questions formulated to provide additional validation for the determined research design of the quantitative experimental study.

The interviews were independently evaluated by two coders to assure objectivity of the results, and the presented findings are the consensus solution. Following the initial evaluation, all involved authors have reassessed the results and their sensibility.

The initial interview findings indicate that experts entered the domain of sustainable website design through diverse career paths influenced by their individual values. This diversity ensures the heterogeneity of the experts’ knowledge.

RQ1: How is sustainable web design defined?

Sustainable websites are capable of mitigating environmental impact via energy conservation and CO2 reduction, concurrently enhancing web performance. Another aspect of sustainable web design is seen in the support of a holistically sustainable website life cycle.

The results thus correspond to the theoretical definition used to describe the concept of “sustainable web design.”

RQ2: Which sustainable practices are considered particularly important?

In this context, experts consider minimalist and timeless design to be essential for promoting sustainability and reducing resource requirements. A consensus among all experts regarding sustainable web design practices centers on the optimization of visual elements, especially images and videos. The choice of formats plays a particularly critical role here. According to the experts, images in particular are not yet stored in modern formats, which increases the data load of these elements. Furthermore, color selection of elements and the incorporation of a dark mode option are considered critical factors.

In addition, the results of the interviews suggest that websites can be designed sustainably by optimizing fonts and embedded scripts. Associated with script optimization, the expert interviews suggest that enhanced data protection is likewise deemed an essential practice in sustainable web design.

The experts’ statements also suggest that choosing a low-maintenance CMS has a positive impact on a website’s environmental impact. Sustainability is achieved here through lean website code and the minimization of work processes associated with efficient page display.

Another essential practice of sustainable web design is the establishment of green hosting. This encompasses data centers that utilize servers to provide websites and content to users, operating exclusively on renewable energies.

The interviewed experts identify the scarcity of knowledge concerning web sustainability as a primary challenge. Sustainability aspects continue to play a very minor role within the web design industry and in education. Another challenge arising from this lack of knowledge manifests itself in the actual implementation. The results show that acquiring knowledge about sustainable practices is time-consuming, and implementation and execution also require time. However, these time resources often conflict with the goals of companies. From a company perspective, there is also a discrepancy between the design requirements for websites and sustainable practices, which require a more minimalist approach.

Nevertheless, the forecasts from the final interview section suggest these barriers will diminish over the forthcoming five to ten years. The findings suggest an anticipated rise in web sustainability awareness.

RQ3: Do sustainable web design practices have an impact on user behavior on a website?

Sustainable web design practices positively influence environmental outcomes and concurrently yield enhanced website performance, thereby improving the user experience. The expert interview findings corroborate this, demonstrating that a sustainably optimized website exhibits reduced loading times and a clearer structure, consequently enhancing user experience, dwell time, and conversion rates. In addition, the interview results prove that sustainable web design has a positive effect on search engine optimization, which leads to increased website visibility and user reach. An additional benefit of sustainable web design, from the user perspective, is the minimization of data consumption.

According to experts, however, the most significant impact on user behavior is not directly evident in the practices themselves, as their effects—such as faster loading times or clearer structures—are not immediately perceived in terms of sustainability. Conversely, the transparent communication and disclosure of these sustainable web design practices exert a more significant influence on user behavior. The analysis shows that successful communication promotes user trust in a company and strengthens their identification with the company. This, in turn, positively influences purchasing decisions. In this context, however, it should be noted that the experts draw a certain distinction. This is evident from the interview results, which show that sustainable web design in conjunction with the aforementioned communication tends to benefit companies or organizations that already have a sustainable orientation. Nevertheless, the experts agree that the implementation of sustainable web design can be a decisive competitive factor in the long term, provided it is integrated into the digital marketing strategy in a credible and transparent manner.

RQ4: What measures support the communication of sustainable web design practices?

Initially, a consensus among experts establishes sustainability labels as the most efficient and prevalent communication measure. An important communication measure that emerges from the results in this context is the visibility of the use of green hosting. According to the experts, transparent communication about the use of renewable energy in the context of the website generates more trust and customer loyalty.

The interview results also demonstrate that the presentation of comparative data on energy consumption or CO2 emissions is an efficient communication strategy for raising awareness of websites’ environmental impact.

Regarding the measures mentioned, the experts once again emphasize the need for credibility and transparency to present an authentic sustainable corporate philosophy and also to counteract any accusations of greenwashing.

3.2. Quantitative Survey

3.2.1. Description of the Sample

Since a convenience sampling approach has been implemented, information about bounce rates is not available. All participant data was collected anonymously. The only meta-information recorded has been the time spent with the survey to assess deviations from the mean processing time.

While a total of 339 participants clicked the survey link and started the survey. Following adjustments for incomplete and invalid observations, the sample has been cleaned for questionnaires where the answering time was too short (mean answering time minus one standard deviation) or too long (mean answering time plus two standard deviations). The final sample consists of 107 participants drawn from the German population. Using Yamane’s formula [

56], this sample size results in a sampling error of 9.67%, putting it below the critical threshold of 10%.

63.6% of the sample are female, 34.6% are male, and 1.9% are diverse. The median age of the sample is 29.48 years, and 71% hold an academic degree. Regarding income, the median monthly net income was €2400.76. 80.4% of respondents reported using the internet several times per day, and 16.8% reported regular or near-daily usage.

In terms of sustainability types, more than half of the respondents (54.2%) can be classified as “oriented.” According to Stieß et al. [

50], this group is characterized by strong environmental behavior and a pronounced focus on environmental protection. Consequently, this group exhibits a limited propensity to adopt further sustainable changes in their attitudes and behavior. The second largest group in the sample is classified as “the open-minded.” In contrast to the “oriented,” a significant discrepancy between environmental awareness and active environmental behavior is observable within this group. The third most common group is “the undecided” with 15%. This group shows average environmental awareness and average environmental behavior. Furthermore, their propensity for behavioral change is less pronounced than that of “the open-minded.” Only 6.5% have a clearly negative attitude toward environmental and sustainability issues.

While this sample might be biased as compared to the average internet user, it targets in particular those users who are particularly open to and perceptive of these types of issues and thus establishes a baseline.

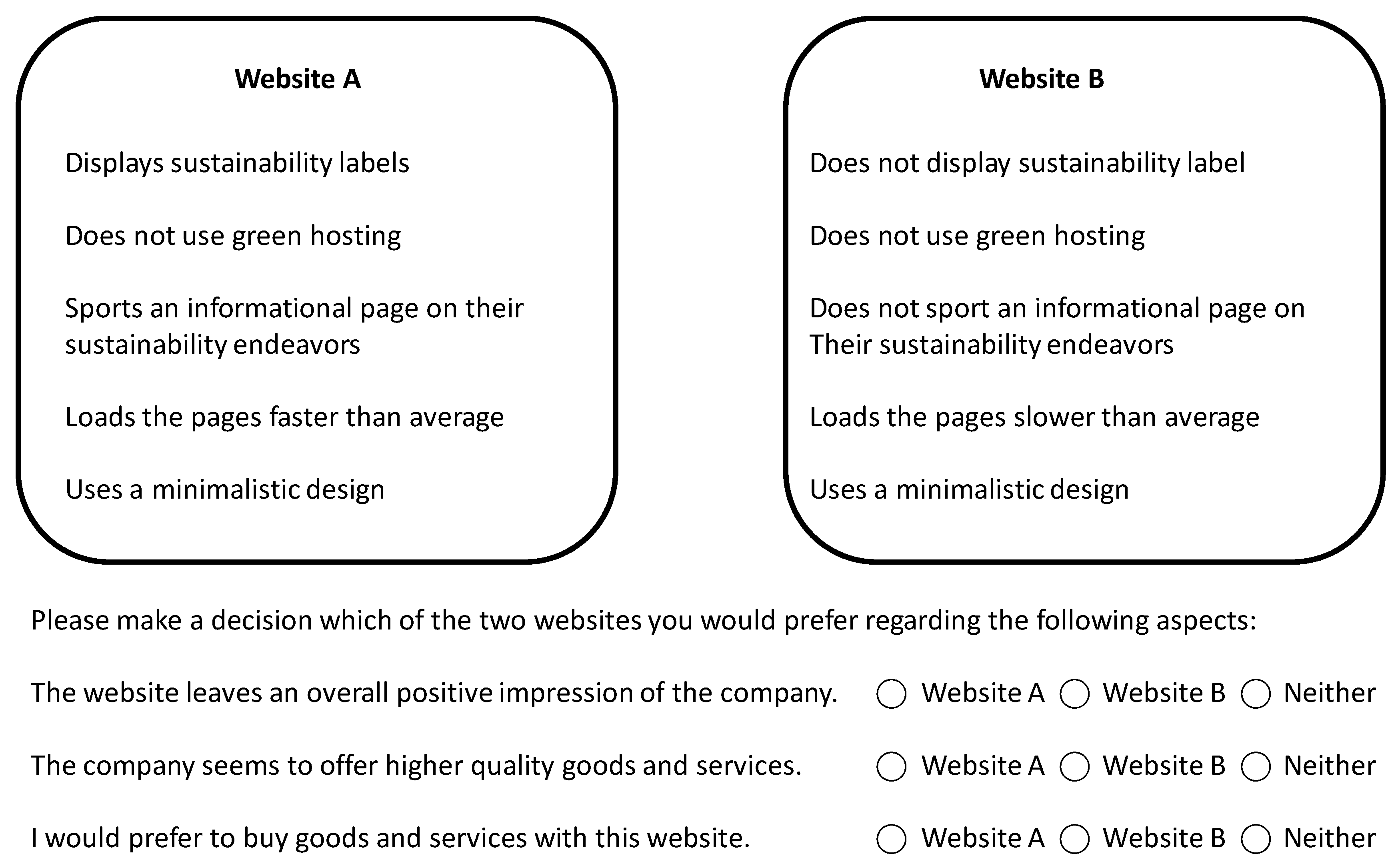

3.2.2. Evaluation of the Discrete Choice Experiment

The present study sought to analyze the influence of the attributes on participants’ stated choices across the three dimensions: company perception, product or service quality, and purchase completion. This evaluation enables a conclusive answer to the central research question of whether the communication of sustainable web design practices influences the perceptions and decisions of website visitors.

To address the three core research questions, separate estimations were conducted. Model I focused on the positive company perception, Model II on the perceived product and service quality, and Model III on the purchase intention generated by the specific website.

While choice cards were randomly selected, the three choices per card were queried in the same order and in relation to the same choice card. To ensure that this did not result in a common method bias, bivariate associations between the choices were assessed using χ2 tests and Cramer’s V as a measure of effect size. Aside from assessing a potential common method bias, this analysis revealed if the three measured choices are related to each other.

Choice 1 and Choice 2: 0.635 ***

Choice 1 and Choice 3: 0.620 ***

Choice 2 and Choice 3: 0.684 ***

The results suggest a strong degree of interrelation among the three outcomes. However, it is not too excessive, allowing to mitigate concern regarding a problematic common method bias. The first choice targeted the brand perception, while the second choice targeted perceived product quality. The third and final choice targeted purchase intention.

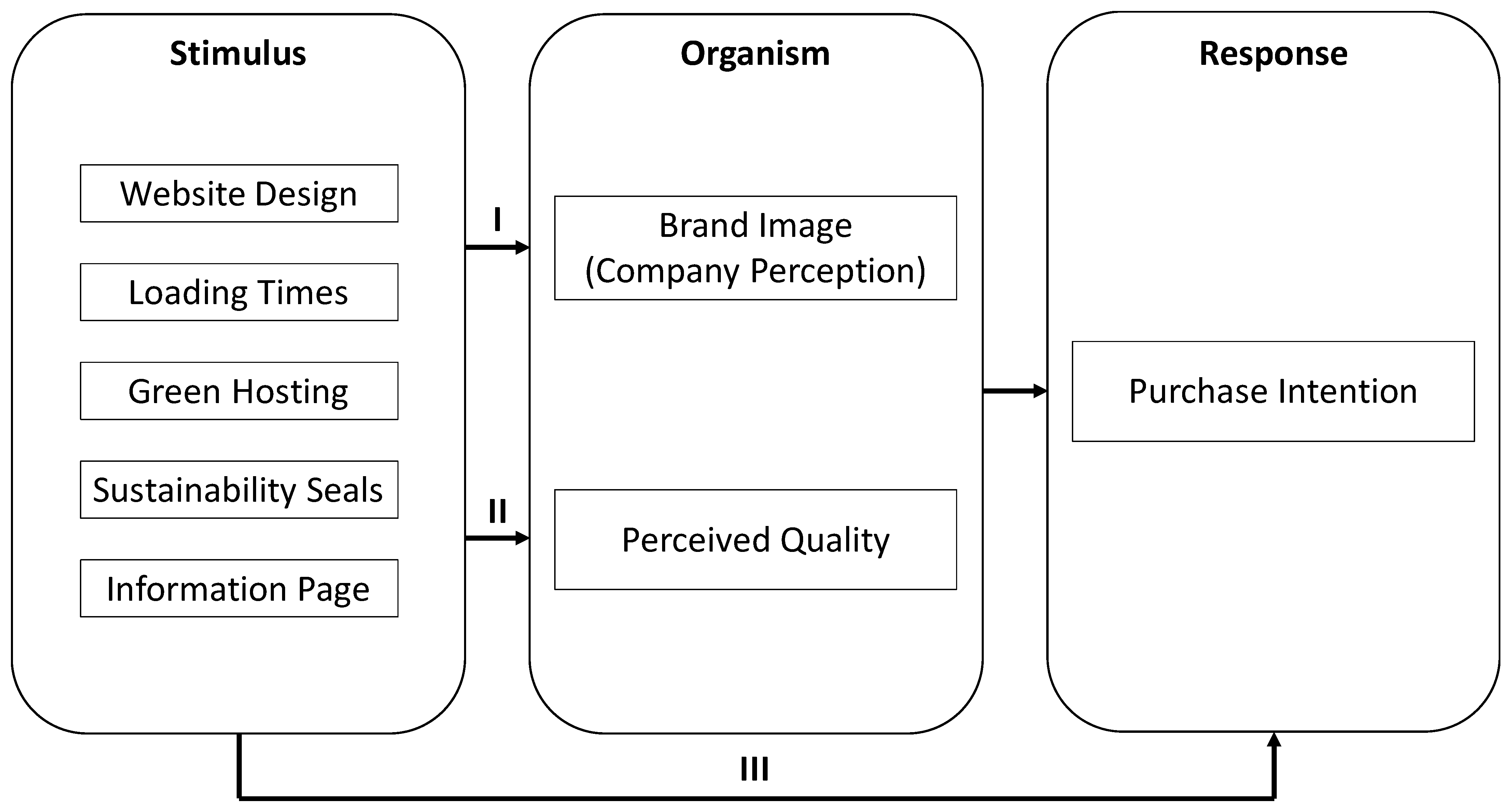

Referring to

Figure 2, the last two estimations provide insights into the unnamed relationship between the organism and the response components of the underlying S-O-R design structure.

To estimate participants’ preference structures, multinomial logistic regressions were performed for each aspect using the R (version 4.4.2) package Apollo (version 0.3.2) [

57]. The implementation used the BGW (Bunch-Gay-Welsch) algorithm [

58]. The utilized R code can be found in

Appendix A.2. The results of the multinomial logit models I, II, and III are summarized in

Table 3,

Table 4 and

Table 5. The first value shows the determined coefficient. This is followed by the robust standard error in parentheses. The significance levels (

p-values) based on the robust standard errors are indicated by asterisks: *

p < 0.05//**

p < 0.01//***

p < 0.001. It can be noted that the robust standard errors provided by Apollo are clustered standard errors, making their use well suited for small samples.

As all attributes are coded as binary variables, the coefficients facilitate a comparison of the relative strength of their influence. To illustrate them better, the results have been reproduced as a heatmap in

Figure 4. For each of the five attributes, the intensity of the color represents the size of the coefficients per model. As stated before, since all items in the analysis use the same scale, coefficients can directly be compared with each other. Regarding ρ

2 and the probability ratios, the comparison is across models with the color intensity indicating the models, of higher quality.

Model I presents the results concerning the positive perception of a company as a function of the sustainable website attributes examined. The results indicate that the presence of a sustainability seal exerts a significant positive influence on participants’ choices, however, only regarding the website, i.e., the company, or brand perception. It is of particular interest that these seals do not seem to impact the purchase intention of website visitors. The analysis also revealed that fast loading times have the second strongest influence on the respondents’ choice of variant. Green hosting communication also has a significant positive effect on the choice. The presence of an information page on the company’s sustainability efforts has a moderately positive effect on the choice of variant and is nevertheless highly significant. The minimalist design exhibits a positive coefficient, whereby users’ perception of a company is positively influenced. The same holds for faster loading speeds as well.

Model II analyzes the influence of the given attributes on the perceived quality of the products or services of the hypothetical website variants. It reports that a fast loading time has the strongest positive influence on the selection of the variant and is highly significant. In second place is the presence of a sustainability seal, which is also highly significant and positively influences the selection of the participants. The disclosure of sustainability endeavors proves to be the third strongest factor with a highly significant effect on the respondents’ choice. Similar to Model I, disclosure of green hosting also has a significant positive influence. However, this effect is less pronounced than the attributes mentioned above. Furthermore, it was found that the design no longer has a significant influence on the test subjects’ choice. In summary, it can be stated that fast website loading times and the communication of sustainable practices through seals, green hosting labels, and information pages have a positive influence on the perceived quality of the products or services on a website. As in Model I, minimalist design has no effect on the perceived product or service quality.

Model III illustrates the effects of the attributes on the selection of website variants in the context of the respondents’ purchasing decisions. In this model, too, fast loading times and disclosure of sustainability endeavors prove to be the most significant positive factors. They are followed by sustainability seals, which also have a strong positive and significant effect on the respondents’ choice. In contrast, a minimalist design again is insignificant. The analysis of Model III demonstrates that the observable technical factor of rapid loading times and transparent sustainability practices, such as the presence of a sustainability seal or the communication of green hosting, positively influence the purchase decision.

Thus, if the website demonstrates sustainable practices, such as sustainability seals, green hosting, and an information page about the company’s efforts in this area, the company is perceived more positively. These positive perceptions, however, only partially transform into a higher intention to purchase from that website. Since loading speed and the design are critical aspects, they exert positive effects on perception. The conception of the website matters to consumer perceptions and their purchase intentions as well.

McFadden’s ρ

2, often misnamed a pseudo R

2 statistic, is considered a suitable measure for assessing the quality of a choice experiment [

59]. Compared to traditional measures of determination, it has the disadvantage that high values do not necessarily guarantee a good model fit, and low values are not necessarily an indicator for unsuitable models [

59]. Consequently, no established critical thresholds exist; however, values beyond 0.2 are perceived to indicate “extremely good” model fit comparable to R

2 scores beyond 0.7 [

45] (p. 54). Building upon this interpretations the study results indicate a strong Model I and at least mediocre Models II and III.

Additionally,

Table 2 reports for each model the shares of correctly predicted choices vs. total choices. Considering that three choices are possible, i.e., website 1, website 2, or opting out, under random distribution a third of all choices would be predicted correctly. Thus, with ratios larger than 0.5 in five models, these results back up the previous assessment that the estimations are at least of moderate quality, with the results for Model I being superior to those for Models II and III. In summary, the comprehensive model structure consisting of the five implemented attributes can be considered relevant to the three questions asked.

To further assess the robustness of the findings, a mixed logit estimation with 2000 draws was performed for each of the three models. Since mixed logit estimations are considered to be IIA-free, a comparison between the two models enables the determination whether problems with irrelevant alternatives are present in the model. The respective estimations are designated as Models I’, II’, and III’. Even though mixed logit estimations have stronger requirements regarding the number of participants, the approach can still be used as a robustness check for the main study results. Thus, a comparison of these results with the initial estimations indicates that the established choice structures are largely consistent and individual preference heterogeneity introduces only minor variation to the study outcomes. This finding is further supported by the respective standard deviations for individual structures, which are consistently close to zero.

To address potential effects of tertiary covariates, three additional models were estimated, not presented here, incorporating the participants’ gender, age, internet usage, and membership in one of the six previously defined sustainability types. The findings consistently demonstrate only marginal shifts in the coefficients. In Model I, only the dummy variables for Generation Y and the Skeptics and Open-Minded sustainability types were statistically significant. Model II similarly showed a significant impact for Generation Y, with all sustainability type dummies exhibiting significant effects. Finally, in the expanded Model III, only the dummy variables for generations Y and Z were statistically significant. In summary, the core findings demonstrate robustness across the set of control variables. Specifically, Generation Y participants generally exhibit a higher predisposition towards sustainable web design. The effects of the sustainability types appear to reinforce this pre-existing preference for sustainable web design.

The answer to the research question “Does the communication of sustainable web design practices have an impact on the perceptions and decisions of website visitors?” can be summarized as follows based on the results.

The results of the three multinomial logit models show a significant impact of communicating sustainable web design practices on the perceptions and decisions of website visitors. A fast loading time for websites initially proves to be particularly decisive. Although this cannot be disclosed through direct communication measures, it is actively perceived by users when visiting the website and can be achieved through the use of sustainable practices. The results indicate that websites with fast loading times significantly increase the likelihood that users will perceive the company or brand and the quality of the products or services offered more positively. The likelihood of a purchase intention also increases.

Furthermore, the results indicate that communication measures promoting sustainable web design practices in the form of sustainability seals, disclosure of green electricity hosting, and the provision of transparent information about corresponding sustainability efforts also have a positive impact on users. The use and implementation of corresponding measures on websites significantly increase the likelihood of positive perception, quality assessment, and purchase decisions for users.

4. Discussion and Conclusions

4.1. Discussion of Theoretical Insights

Expert and consumer perceptions point in the same direction. The insights gained from the qualitative interviews with industry experts, in essence, coincide with those presented by Hansen et al. [

48]. Thus, the practical foundation of this study is strong enough for the discrete choice experiment.

The findings of the quantitative part of the study, the discrete choice experiment, indicate that aspects, inherently visible to website visitors, like loading speeds and the implemented design, have a positive impact in the same way as communication vehicles like seals, labels, or information pages.

Loading speeds, as already established in previous studies [

25,

31,

33] have an established positive impact on consumer perception. These findings do not surprise since they are in line with continuously decreasing attention spans and the need for instant gratification [

60]. Thus, while it might be conjectured that in times of 5G and fiber optic home connections, fast loading speeds might be a hygiene factor of websites, the findings of this study posit that they indeed still possess the potential to impact consumer perception positively.

Similar to other studies on e-commerce [

28], sustainability labels are useful only to a limited extent, and brand image is the only aspect they significantly impact. Green hosting, comparable to the findings by Preist et al. [

37] and Lacom and Sagot [

24], is positively received by the participants. To make the use of green hosting options known to website visitors, communication tools, or as is currently the situation, labels and seals are required. In light of the reduced effectiveness of eco-labels [

28], it remains an open question whether green hosting will be able to realize its full potential.

The findings also imply that consumers prefer a minimalistic design as compared to sophisticated page designs. Thereby the results coincide with the findings by Kiourtis et al. [

23] and in part Shaban et al. [

26]. They conflict with the study by Hu et al. [

29], who positively report about the use of multimedia integration.

The results for sustainability reporting can be interpreted from a general transparency perspective and from the perspective of communicating sustainability endeavors that are not directly obvious to the website visitor. For transparency in sustainability reporting, Jestratijevic et al. [

61] find mixed results, stressing the long-term commitment to transparency. For sustainability reporting in Korea, Jang [

62] finds positive results for the brand image and the purchase intention. In this case, sustainability reporting works via a strengthened consumer trust. In comparison, Amoako et al. [

63] for Ghana do not find significant effects regarding sustainability communications of universities. Regarding sustainability communications in the context of web design, Kiourtis et al. [

23] in general reports positive effects. These positive effects on brand perception and purchase intention, as in the case of Jang [

62], are seen in the findings of this study as well. Compared to Jestratijevic et al. [

61], they seem to lead to immediate effects without having to be developed over a longer time horizon.

Coefficients indicating the impact of each of the five aspects reveal no clear indication of whether inherently visible aspects of websites or implemented communication tools are more effective measures.

The findings also indicate that while the five chosen attributes can capture a relevant share of the dispersion inherent to consumers’ choices, there remains distinct room for improvement. This translates into the assessment that aspects of sustainable web design are critical marketing instruments, but they are by far not the sole drivers of consumer perceptions of the brand image and their purchase intention.

4.2. Recommendations for Practitioners

The page design and its loading time are directly perceived by the visitors. Where the results for website designs are ambiguous, with some studies reporting positive effects of more sophisticated sites utilizing animations and other types of multimedia, this study found that participants significantly preferred minimalistic websites. However, it needs to be acknowledged that the understanding of what constitutes a minimalistic web page might differ across consumers. Thus, companies need to elicit in particular for their target groups what kind of website design is expected and what are the most critical elements for this specific population.

Faster loading speeds address consumers increasing need for instant gratification and their reduced attention spans. Thus, aside from being a result of reducing the page load of websites, they pose a critical aspect of website operations in either case. For designers and operators of websites, this finding translates into the necessity to utilize efficient website coding and avoid solutions, often AI- or no-code-augmented, that provide fast and easy-to-build website solutions but are mostly not optimized in their resource use. In particular, for operators of websites that are dependent on the provision of large amounts of image or video material, e.g., e-commerce websites, the use of resource-saving image and video formats like WebP and WebM is recommended.

After videos and images, one of the largest impacts on the page loading times results from the execution of scripts, i.e., foremost JavaScript files. Thus, avoiding or reducing the overall execution of scripts can significantly lighten the overall page load.

Especially in the context of e-commerce websites, dynamic content management systems can help in reducing the overall load of the website by eliminating the need to generate and save each page separately. Finally, the use of only a reduced set of standard fonts can reduce the overall page load as well.

Beyond loading time, an important and actively perceived factor for website users, the sustainable web design practices discussed herein are not directly perceptible. Nonetheless, the application of sustainable web design practices intended to mitigate power consumption and CO2 emissions can be actively disclosed to website users.

Seals, labels, or certificates are employed to communicate this information. These typically appear in the website footer, signifying, for instance, that the site is climate-neutral, generates reduced CO2 emissions, or is hosted on servers exclusively powered by green electricity. This transmits a message of digital and ecological stewardship. The research findings indicate that the deployment of such seals, labels, or certificates can foster a favorable corporate or brand image, given users’ growing appreciation for organizational sustainability initiatives.

Based on the theoretical and qualitative findings, the utilized seals ought to be grounded in a transparent and holistic sustainability strategy. Organizations that procure seals solely via compensation payments or neglect to pursue additional operational sustainability efforts risk accusations of greenwashing. Since most of the labels regarding sustainable websites are not commonly known to consumers, their utilization needs to be carefully curated so that consumers understand that they represent authentic sustainability endeavors by the company and not just another greenwashing endeavor. One option to avoid the greenwashing trap can be found in providing website visitors with links to external institutions, i.e., ideally governmentally operated, that vouch for the authenticity of the respective seals. Summarizing, seals and labels can only function effectively if they are consistently and transparently communicated to consumers and allow for external validation.

Disclosure of sustainable measures, such as green hosting certificates or comparative data on the website’s carbon footprint, can be augmented by supplementary information pages that detail digital sustainability efforts. This enhances credibility and contributes to user trust and customer loyalty via an increased transparency of company politics. The increased transparency also helps in reducing the risk of perceived digital greenwashing. With the availability of external validation, consumers have the opportunity to fact check all sustainability claims themselves.

In this context, it is evident that the adoption of sustainable web design practices is especially advantageous for companies and brands that already possess a sustainability-oriented digital presence or have implemented sustainability into their business model. The discussed measures appeal to environmentally conscious target groups in particular. Customers who value ethical and ecological behavior are strengthened in their loyalty by the transparent disclosure of sustainable web design practices. Although the influence on other target groups is comparatively lower, the research findings of this study demonstrate that sustainable web design can elevate general user awareness and has the potential to increase the brand image.

4.3. Limitations and Outlook

This study provides important insights into the sustainable design of websites and the corresponding practices. Nevertheless, the chosen research approach exhibits limitations that define the scope for further research in this area.

Firstly, it must be acknowledged that the sample utilized in the quantitative choice experiment lacks sufficient representativeness to extrapolate the findings to the entire population of German internet users. In addition, the sample is characterized by a disproportionately high percentage of individuals with elevated environmental and sustainability awareness. As a result, the respondents show significantly greater openness to sustainable communication practices compared to individuals without a corresponding awareness of environmental and sustainability issues. This may result in an overly optimistic assessment of sustainable web design practices compared to the general population. Consequently, future research in this domain should be larger in scale to procure a more extensive, homogeneous, and representative sample.

This study already controlled for some socio-demographic and socio-economic factors. In the future, studies should focus on this issue more strongly and establish if the findings will also hold beyond the scope of this study, i.e., in light of different cultural backgrounds with alternative internet usage behaviors. With differing cultural backgrounds, participants have different understandings of sustainability and regarding the conservation of energy, i.e., with differently established long-term and indulgence dimensions considering the cultural dimensions by Hofstede. Additionally, seals, which essentially are a reference to authorities, might be perceived differently by cultures with bigger or smaller power distances.

A broad intercultural study might offer an answer to the issue raised by Sarapure and Tarun [

4] that currently no official international guidelines for sustainable web design exist. It can help conceptualize cross-cultural as well as culture-specific guidelines.

Since these aspects are subject to continuous change, the study needs to be repeated on an ongoing basis, and longitudinal data on consumer perceptions and changes thereof needs to be generated and studied.

An additional limitation of the quantitative research approach pertains to the cognitive capacity of participants. For the choice experiment, five website attributes were defined, each of which has two different characteristics. Using an orthogonal design, the choice sets per subject were reduced to eight. It is conceivable, however, that the volume of decisions prompted participants to employ simplified selection strategies, potentially yielding biased or inconsistent decisions. It should also be noted that the choice experiment takes place in a hypothetical context in which respondents have to make decisions. In a real-life situation, there are a number of other influencing factors that affect the evaluation of websites in the context of sustainable web design. These include, for example, the popularity of the company or website and users’ existing emotional attitudes towards them.

In the present study, the hypothetical decision-making situations were highly objectified. Consequently, the choice experiment confronted the participants with an artificial situation. While this aspect reduced the study’s validity, it offers the advantage that the participants’ attention was focused on those attributes of particular interest. However, it remains a relevant open question whether the findings of this study would remain comparable if the DCE were repeated under more realistic conditions.

Additionally, to obtain generalized research findings concerning the communication of sustainable web design practices, industry sectors website typologies (e-commerce shop, blog, service) were not differentiated. Future research could investigate the effect of communication measures on sustainable websites, integrating the specific characteristics of the respective industry or website typology. While some sectors are highly reliant on image and video inputs, e.g., retail or luxury brands, others rely primarily on textual information, e.g., blogs or news sites. Thus, it is recommended to specialize research by focusing on specific product segments and price ranges. For example, the effect of corresponding practices and communication measures on a website for luxury goods could be researched for this specific target group.

It has been argued that discrete choice models are superior to models like the TAM or the UTAUT2. These models, however, have the advantage that they more strongly target aspects fostering the adoption of new technologies. Thus, replicating this study in the methodological context of, e.g., the UTAUT2 model or combining both approaches in an ICLV model would allow to more clearly elicit those determinants driving the adoption of sustainable web design by designers, companies, and internet users.

The energy-intense use of artificial intelligence increasingly gains traction in the domain of web design as well. This leads to the problems of second-stage energy consumption of internet use needs to be incorporated in the CO2 footprint, i.e., energy not primarily used for the visit and the maintenance of the website but for preceding services like website design or the operation of web services like chatbots. If an overall sustainable digital web presence is the primary objective, then these aspects need to be considered in a comprehensive approach. Consequently, research is required on the interplay of additional services generated via AI, their implementation, and their impacts on overall energy consumed.

_Li.png)