1. Introduction

With the rapid advancement of urbanization and the increasing prosperity of the socio-economy, human living standards have significantly improved [

1]. However, this development model, which heavily relies on massive resource consumption, has also profoundly impacted regional ecosystems. In this process, land, as the core spatial carrier supporting various human activities, has seen the rationality and sustainability of its utilization patterns become a key factor influencing the quality of development. Driven by population growth and over-exploitation, issues such as deforestation [

2], loss of arable land [

3], land pollution, and ecological degradation [

4] are becoming increasingly severe. These challenges endanger the ecological security of the region and limit the potential for high-quality socio-economic development. Land not only underpins economic activities including agriculture, as well as industry, mining, and urban construction but also sustains cultural heritage and human health [

5].

Socioeconomic activities and land use changes demonstrate a bidirectional coupling relationship [

6]. The evolution of socioeconomic systems drives transformations in land use by reshaping land demand patterns—economic growth and shifts in consumption elevate the need for urban construction land and commercial forestry [

7]; rising urbanization rates lead to rural-to-urban migration, indirectly causing cropland abandonment and the restoration of natural forests in rural regions. Industrial restructuring, such as an expanding service sector, reduces dependence on industrial land while supporting forest conservation through ecotourism development [

8]. Conversely, the optimization or imbalance of land use structures constrains socioeconomic development quality. Expanding forest cover enhances ecosystem service values, providing a foundation for green industries. However, excessive reduction in cropland threatens regional food security and hinders agricultural modernization [

9]. Uncontrolled expansion of construction land may result in inefficient resource use and intensify human-land conflicts [

10]. Therefore, how to scientifically coordinate human-land relationships and optimize land use patterns has become a crucial and urgent task for achieving sustainable development goals.

Against this backdrop, gaining a deep understanding regarding the intrinsic patterns of land use change is particularly important. Land use change is typically manifested across multiple dimensions, including quantity, structure, intensity, and spatial form, illustrating the dynamic interplay relationship among human activities with the natural environment [

11]. As the stages of development evolve, driven by natural conditions and socio-economic factors, the patterns of land use have become increasingly complex and diverse, forming intricate interrelationships. Consequently, systematically revealing the patterns of land use change, predicting future trends, and constructing rational land use allocations have become core tasks in this field of research [

4,

12,

13,

14].

To achieve these objectives, land use change, its prediction, and simulation have long been focal points in international academic research. Numerous scholars have conducted extensive empirical and methodological explorations from different regional perspectives. For instance, some studies have employed multi-temporal land use classification methods, based on Landsat data from 1984 to 2016, to systematically track the expansion processes of 18 Canadian cities and provide multi-scale assessments of land change from pixels to broader census areas [

15]. Other research combined long-term aerial imagery with field surveys, applying semi-automatic classification and principal component analysis to identify land cover changes, and further processed and analyzed the data using GIS layers and principal component analysis [

16]. In a study of the Guder watershed, researchers used remote sensing and GIS, as well as the Google Earth Engine platform, to forecast land use scenarios for the years 2039 and 2057 using Random Forest and Neural Network models [

17]. Further studies, based on CA-Markov models and Landsat imagery, conducted in-depth analyses of land use configurations and anthropogenic drivers in rapidly changing areas: one study constructed a predictive model for land use/cover in downtown Mamuju to forecast its 2034 land use scenario [

18]; another study, through Landsat-based analysis, identified cropland expansion, unauthorized settlements, deforestation, charcoal production, and livestock grazing as the primary drivers of local land use change [

19].

Research within the Chinese context has likewise seen substantial advancements, employing a diverse suite of models to simulate, and forecast land use dynamics. Early efforts, such as one focusing on the Baihe River Basin, applied the model of CA-Markov to simulate its 2020 land use pattern based on historical data from 1996 to 2008 [

20]. Other work employed remote sensing techniques to evaluate land use dynamics in China’s arid northwest from 1990 to 2020, quantifying distribution patterns and predicting future scenarios to inform regional strategies [

21]. The methodological toolkit has since expanded significantly. For instance, a study developed a coupled ANN-CA-Markov model for multi-period land use simulation in Dongguan City, projecting future patterns for 2025, 2030, and 2035 to offer actionable planning suggestions [

22]. Furthermore, the PLUS model was utilized to forecast Harbin’s urban land use for 2029, offering essential guidance for the city’s future planning [

23]. Further analyses of three cities which are along the ancient Shu Road at Jianmen Pass, based on the MCE-CA-Markov model, not only delineates the trajectory of land use development between 2012 and 2022, but also forecasts the scenario for 2027 to optimize resource allocation [

24]. Additionally, research employing the FLUS model and grey relational analysis predicted and interpreted land use change trends for 2030 in Poyang Lake wetland, while also using the grey relational model to analyze the underlying driving factors [

25]. The GM(1,1) model is extensively utilized in land use prediction. It enables diversified forecasts for multiple regions based on measured data from various time series. Examples include the prediction of land use status in Luzhou District of Shanxi Province for 2020 [

26], the forecast of land cover area in the black soil region of Northeast China for 2025 [

27], the projection of land ecological security status in Shenzhen from 2020 to 2025 [

28], and the simulation of land use/cover change (LUCC) in the Pearl River Delta region [

29]. The results of these predictions not only elucidate the changing trends in regional land use quantity and the evolution of ecological security but also offer scientific references for the protection of regional land ecosystems, comprehensive management, and the formulation of related policies.

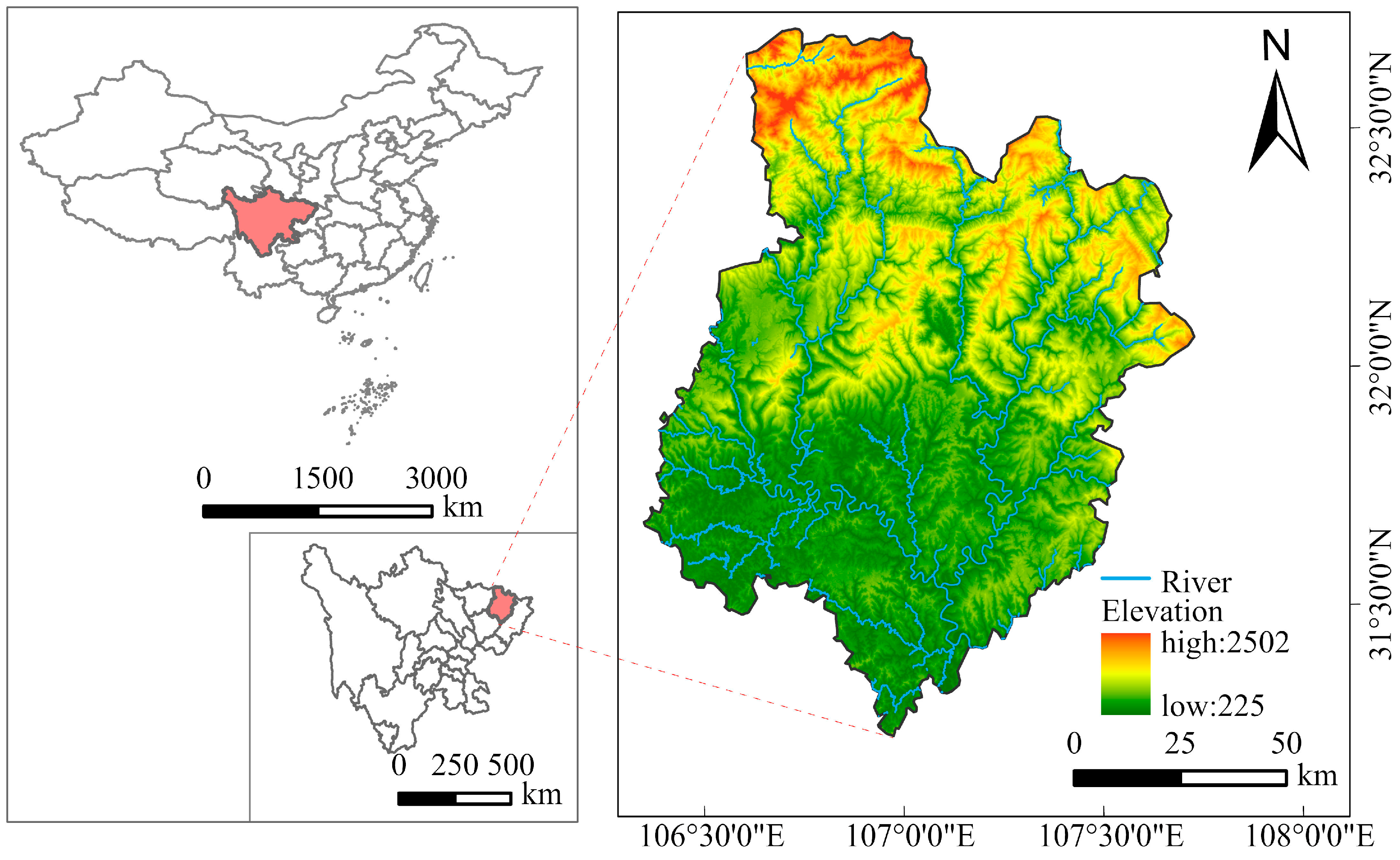

Although domestic and international land use research has established a relatively mature methodological framework and accumulated a wealth of regional case studies, systematic research on land use change remains relatively scarce for prefecture-level cities in Western China with unique geographical and ecological characteristics, such as Bazhong City. The interactive relationship between land use and socio-economic development in these areas has not yet been fully elucidated. The land use data in Bazhong City lacks granularity but shows stable changes in indicators. The GM(1,1) model, designed for small sample sizes and sparse information systems, does not rely on assumptions about data distribution. This model effectively captures gradual trends, provides simple modeling, and ensures precise short-term forecasting. Hence, it is the preferred approach for making forecasts in Bazhong City.

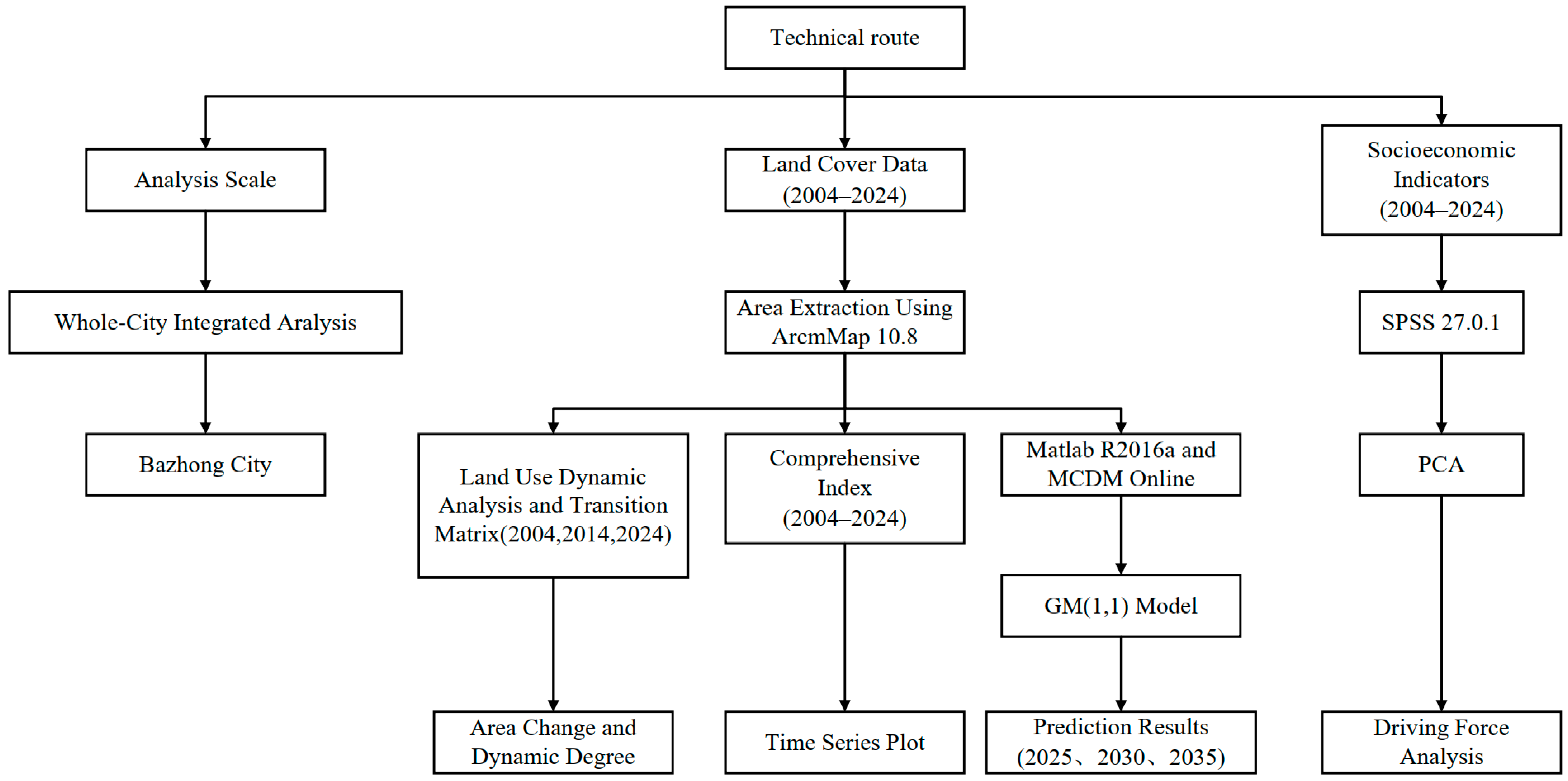

To gain a comprehensive understanding of land use evolution patterns and their linkages with socioeconomic development in Bazhong City, this study examines the period from 2004 to 2024. It quantifies the characteristics of land use changes during this time, identifies the key socioeconomic drivers behind these changes, and forecasts future trajectories of major land use types using the GM(1,1) grey model in conjunction with local spatial planning objectives. This provides a scientific basis for coordinating regional land resource allocation, enhancing ecological protection, and fostering sustainable urban socioeconomic development. The innovations of this study are primarily evident in the following aspects: First, the utilization of 30 m resolution annual land cover data addresses the gap in long-term, high-resolution land use research for cities situated in the mountainous regions of western China. Second, the implementation of principal component analysis elucidates the evolutionary patterns of the driving system, thereby providing empirical evidence for comprehending the human-environment relationship in these western mountainous cities. Third, the application of the GM(1,1) model to forecast future land use trends serves as a valuable reference for decision-making regarding the optimization of regional land resource allocation and the balancing of ecological protection with agricultural production.

4. Discussion

4.1. Domestic and International Comparative Analysis

This study reveals a distinct “three increases and three decreases” pattern in land use changes in Bazhong City from 2004 to 2024, characterized by sustained expansion of forest, water body, and impervious surface, alongside consistent reduction in cropland, shrub, and grassland. This trend aligns with findings previously reported in the same study area [

31].

The land use change pattern in Bazhong City, characterized by a reduction in cropland and an expansion of forest, exhibits similarities with ecologically vulnerable regions in western China, including Guizhou and Gansu. This pattern across these areas is primarily driven by both ecological conservation policies, such as the Grain for Green Program, and ongoing urbanization. During the transformation process, forests in these cities fall primarily into two categories: ecological forests, which focus on environmental conservation, and economic forests, which focus on producing commercial goods. Bazhong City’s forest expansion is characterized by a high proportion of economic forests; Gansu Province’s expansion is primarily driven by natural factors, with Longnan City placing greater emphasis on ecological forest restoration [

12,

47]; Guizhou Province’s expansion of construction land is more pronounced [

60].

In comparison to more developed regions such as Zhengzhou, Hubei (centered on Wuhan), Guangzhou and Jinan, the main cause of cropland reduction is the expansion of construction land due to urbanization and industrialization [

14,

46,

61,

62]. In contrast, the main cause of cropland reduction in Bazhong is the Grain for Green Program, reflecting differences in developmental stages and policy orientations.

Notable differences exist in comparison to foreign regions. For instance, coastal erosion and rising sea levels have degraded 76.04% of cropland in the coastal areas of Bangladesh [

63]. In the Meshginshahr region of Iran, agricultural expansion and urbanization are the main drivers of land use change, with the conversion of pasture and forest land into cropland being the main development strategy [

64]. These two regions are therefore representative of “passive losses” and “agricultural development dominance”, respectively, contrasting with the land use patterns observed in Bazhong City.

4.2. Summary and Implications

Between 2004 and 2024, forest and cropland in Bazhong City experienced the most significant changes in area. Cropland was primarily converted into forest and impervious surface, while conversions between other land types were relatively minor.

The observed land transformation was driven by multiple factors: From 2004 to 2024, Bazhong City’s population decreased by nearly 400,000, particularly among young rural laborers. This demographic shift resulted in significant natural restoration of remote sloping cropland into forested areas. Consequently, this process led to a reduction in the total area of cropland and an increase in forest coverage. Accelerated urbanization and transportation infra-structure development directly converted peri-urban cropland, while the effective implementation of the Grain for Green Program—resulting in approximately 1400 km

2 of converted land—facilitated the transition of sloped and low-yield cropland into forest. These processes collectively led to progressive diminution of agricultural land and simultaneous expansion of forest area. The reduction in cropland far exceeds the increase in impervious surface, resulting in a fluctuating downward trend in regional land use degree and an overall low level of land development intensity. The modest decline in water body following 2014 primarily resulted from reduced precipitation in certain years attributed to climate change, the encroachment of water body due to urbanization and infrastructure development, and the intensified exploitation of water resources. From 2004 to 2024, forest coverage increased consistently, reaching approximately 65% by the end of 2024. This expansion contributed to the enhancement of ecosystem service values, particularly improving water conservation and soil retention capacity [

65,

66].

The concurrent processes of urbanization and forest expansion have revealed conflicting land use dynamics. Prime cropland surrounding urban areas has been encroached upon, while portions of cropland have been converted to forest. Given that Bazhong’s topography is predominantly mountainous, the availability of contiguous cropland is limited. Much of the remaining cropland consists of fragmented, sloped plots with low productivity, further constraining cropland reserve resources, a situation similar to the quality degradation of cropland noted in others research [

67,

68].

In this study, two principal components (PC1 and PC2) were extracted via principal component analysis (PCA). These components can explicitly reveal the driving mechanism of socioeconomic development on the evolution of land use patterns in Bazhong City between 2004 and 2024.

From 2004 to 2010, during the accumulation phase, Bazhong City focused on developing transportation infrastructure and sustaining traditional agriculture. Industrial development centered on small-scale operations and primary processing, while the urbanization rate remained below 30%. During this period, the expansion of land for construction proceeded slowly, maintaining the stability of the overall land use structure.

The period from 2010 to 2018 was a time of robust growth. A pivotal turning point came in 2011, when the Bazhong Economic Development Zone was expanded and relocated, followed by construction. This strategic move spurred a dramatic surge in industrial output value, which jumped from under 100 million yuan to 2.6 billion yuan. The implementation of industrial projects further fueled the restructuring of regional land use configurations, with both industrial and urban construction land witnessing considerable expansion during this period.

The period between 2018 and 2024 was characterized by a surge in growth, marked by a significant shift towards specialization and environmentally—friendly practices in the industrial sector. The completion of the Ba-Shan Expressway, the opening of Enyang Airport and the introduction of high-speed rail services improved transport links. The “One City, Three Districts” urban spatial pattern was formed because of these developments, which led to a significant increase in the urbanization rate to 48%. During this period, the development of urban construction land will shift towards refinement, while the growth of industrial land will decelerate. It is important to note that problems such as unoccupied rural properties and deserted cropland resulting from population migration will further decrease the amount of cropland, indicating the need for urgent action to protect cropland. Subsequent policy implementation will be required to achieve the dual objective of safeguarding the quantity and enhancing the quality of cropland.

According to the forecast results, the area of forested and impervious surface is expected to increase, while the area of cropland, grassland, shrub, and water body is projected to decrease. The amount of cropland maintained is fundamental to sustaining agricultural out-put, ensuring food security, and maintaining social stability. Based on the “Bazhong Territorial Space Master Plan (2021–2035),” the city’s cropland must remain at or above 2520.07 km2 by 2035. Although the projected cropland area for 2035 (3785.76 km2) exceeds the conservation target (2520.07 km2), Bazhong City continues to suffer a net loss of cropland. This trend will reduce the buffering role of regional land reserves, compromise cropland quality and spatial contiguity, and ultimately weaken the region’s grain production capacity, thereby posing a threat to food security. Future strategies should include strict enforcement of the permanent prime cropland protection system to safeguard the minimum quantity requirement. Spatial layout optimization through land consolidation and scientifically delineated urban development boundaries can help revitalize existing land resources. Additionally, implementing high-standard cropland construction and promoting eco-agricultural technologies are crucial to enhancing cropland quality and compensating for quantitative losses.

An increased forested land area helps to reduce soil erosion, enhance water conservation and protect biodiversity. Efforts to consolidate achievements in the Grain for Green Program and strengthen the protection of ecological forests should continue. The reduction in cropland and the outflow of rural populations reinforce each other, which could accelerate the depopulation of rural areas. To reverse this trend, policy measures must improve integrated urban-rural development strategies to encourage population return, facilitate land transfers, and promote large-scale operations, thereby enhancing land use efficiency.

4.3. Limitations and Future Directions

Building upon previous methodologies, this study has yielded certain findings regarding land use in Bazhong City. However, due to the broad scope of the research, limitations in data availability, and insufficient flexibility in methodological application, the following improvements could be made in future studies on land use dynamics and prediction:

Regarding data selection, a 30 m spatial resolution is insufficient for accurately representing the boundaries and internal variability of small ground features. To enhance classification accuracy, future efforts should focus on integrating diverse data sources and advancing sub-pixel unmixing and deep learning methodologies [

69]. The principal component analysis covered 21 years of data and 11 variables. The stability of the analytical results was somewhat compromised by the relatively small sample size and limited number of variables. Key socioeconomic variables such as employment distribution, land prices and policy intensity were excluded during the selection process due to data unavailability, which could result in deviations in the interpretation of the driving mechanisms. This study concentrates on macro trends, considering cropland, forest, and other areas as uniform entities. Neglecting the functional variations within these areas and the consequent requirement for tailored policies could lead to imprecise policy development. Additionally, the absence of consistent quantitative data on the intensity of policy implementation implies that policy outcomes are deduced from contextual correlations rather than empirical testing based on models, leading to constraints in assessing policy impact. Hence, pertinent policy implementations should incorporate functional classification at the parcel level alongside field validation, improve metrics, and adjust them dynamically to improve policy precision and efficacy. Future efforts will focus on creating a comprehensive, long-term, cross-departmental database that integrates multi-source patio-temporal data [

70]. This will enable a more systematic and stable examination of the complex interactions between driving factors. The main constraint in using data from three particular time points—2004, 2014, and 2024—to judge area alteration and build the land use transfer matrix is the incapability to capture the evolving processes of land use transformation over the two decades. Future endeavors will focus on establishing a sequence of datasets with increased temporal granularity, spanning consecutive years or quarters, to accurately depict the ongoing trajectory of land use alterations.

Regarding methodology, the index of land use degree is simple to calculate, and the results are easy to understand. They are also comparable across different regions and can be used in many situations. This index can quickly quantify the intensity of regional land development and utilization. However, it may obscure significant spatial heterogeneity. Future research will incorporate landscape indices such as the Shannon diversity index and the fragmentation index, as well as slope-based stratified analysis and topographic constraint analysis [

71,

72,

73]. The analysis in this study primarily focuses on correlations rather than causality when examining the socioeconomic drivers and land use change. While principal component analysis revealed associations among key factors, including GDP, urbanization rate and land use change (

Table 2), the research did not validate causal relationships directly through regression analysis or causal inference models. The correlations identified in this study should not be equated with unidirectional causality. It is important to avoid overinterpreting the driving effects of socioeconomic factors on land use change. During principal component analysis, influential factors are often regarded as variables assumed to be independent of land use changes, neglecting the effects of time lags and spatial arrangements. Future research will integrate methods such as spatio-temporal lag models and spatial Durbin models to establish a comprehensive framework for understanding the driving forces of land use, taking into account both spatial and temporal dynamics [

74,

75]. The GM(1,1) grey prediction model is known for its low data requirements, lack of specific statistical distribution assumptions and simple calculation process. It mitigates the randomness of the initial data through cumulative generation. It exhibits notable accuracy and stability when forecasting short-term and minor trends in land use changes. The forecast period from 2025 to 2035 aligns with the core applicability range of the GM(1,1) model, with the forecasting error falling within an acceptable range, surpassing long-term predictions exceeding a decade. The GM(1,1) model demonstrates high predictive accuracy for medium-to-short-term land use change trends between 2025 and 2035. However, it is still limited by the inherent uncertainty of forecasting. Based on the cumulative generation principle of time series data, the model mitigates the impact of random influences, yet it fails to account for potential future shocks, such as policy shifts or extreme climate events. Consequently, the deterministic trajectories it generates do not incorporate uncertainty boundaries, such as confidence intervals. The model assumes continuity of historical trends from 2004 to 2024 and does not consider multiple potential development scenarios, such as enhanced ecological conservation or accelerated urbanization. Therefore, applying the findings of this study to long-term planning beyond 2035 requires caution, given that uncertainty in long-term projections increases significantly. However, this model performs poorly in terms of fitting abrupt land-use transitions driven by policy changes, and it fails to incorporate spatial characteristics such as location and neighborhood effects. This makes it difficult to reflect the spatial heterogeneity of regional land-use changes. Future efforts will focus on incorporating additional predictive models (e.g., CA-Markov, FLUS, PLUS) to enhance the accuracy and temporal scope of land use projections [

76,

77,

78,

79,

80].