A Framework for Mitigating Greenwashing in Sustainability Reporting

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Conceptualizing Greenwashing

2.2. Enhancing Reliability in Sustainability Reporting

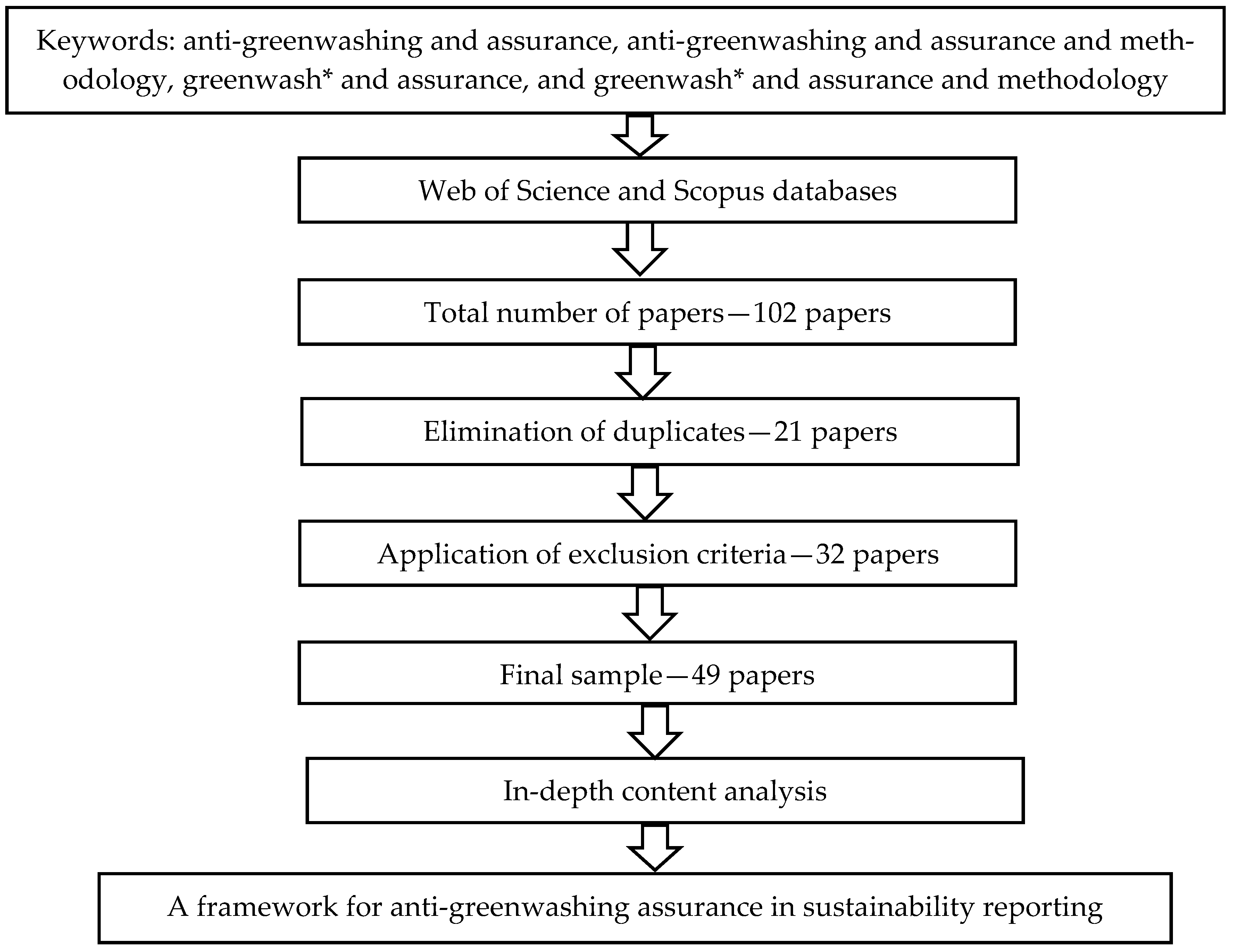

3. Research Methodology

4. Results

- Enhancing substantive action: companies that obtain sustainability assurance tend to increase their substantive green actions. This is observable through higher levels of environmental investment and greater output of green innovations following the assurance engagement [27]. The inhibitory effect of assurance is significantly more pronounced in non-state-owned enterprises [26].

- Reducing symbolic expression: the presence of assurance is linked to a measurable reduction in purely symbolic environmental expressions, vague slogans, and other forms of green talk in corporate reports [27].

- Improving sustainability performance: the assurance process governs greenwashing by serving as a catalyst for improving a company’s overall sustainability performance. This improved performance acts as a mediating factor, directly reducing the gap between claims and actions [26].

4.1. Regulatory Deterrents for Greenwashing Elimination

4.2. Stakeholder Influence on Greenwashing Prevention

4.3. Third-Party Verification and Assurance Quality-Related Issues for Greenwashing Mitigation

4.4. Corporate Governance Mechanisms for Greenwashing Mitigation

4.5. Technology Impact on Greenwashing Mitigation

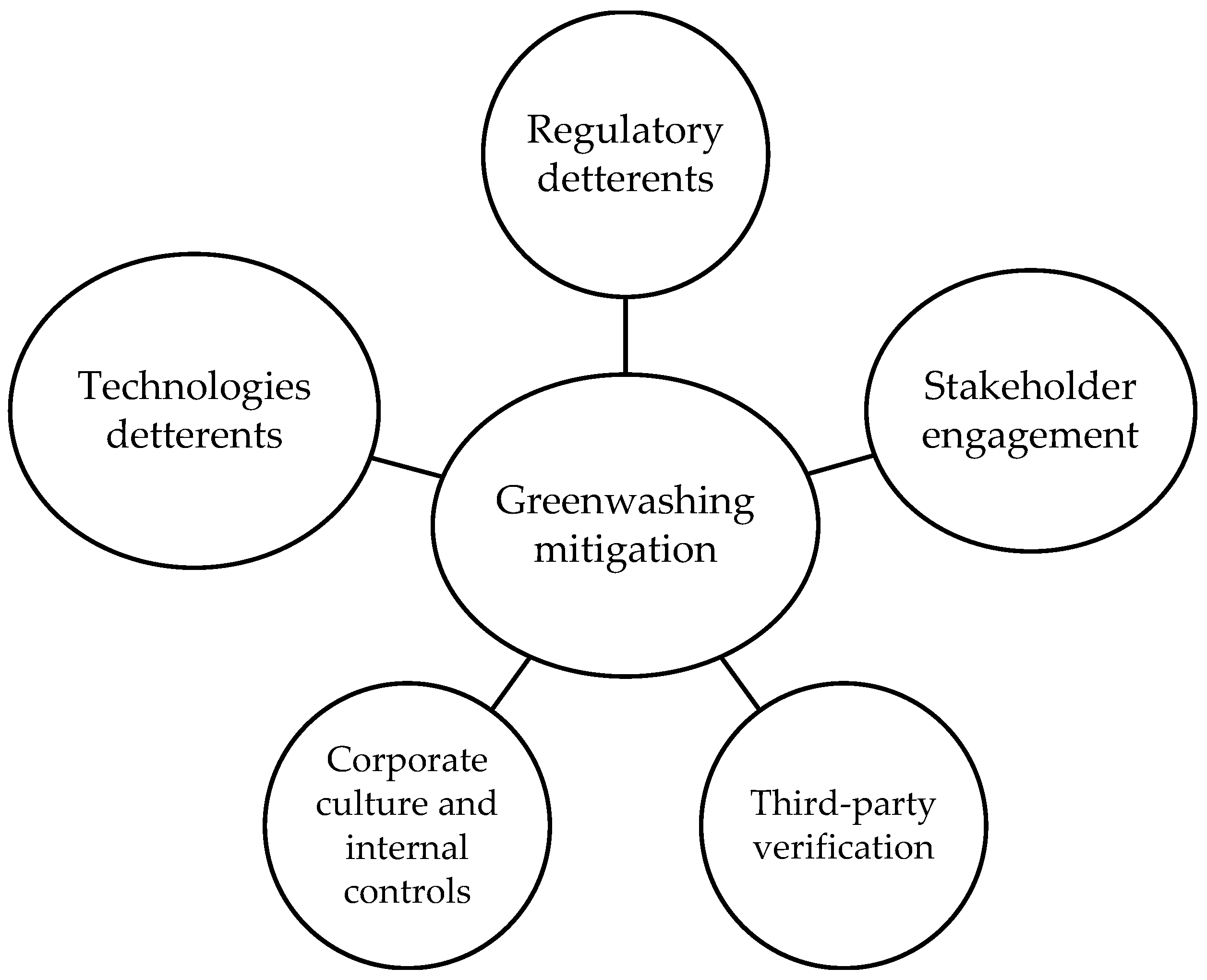

4.6. A Framework for Anti-Greenwashing Assurance in Sustainability Reporting

- 1.

- Regulatory and legal enforcement. Regulations establish the essential baseline for accountability, creating coercive pressure that forces companies to internalize externalities and comply with sustainability expectations. Regulatory frameworks, often grounded in the government’s legitimate power and coercive authority, are binding on companies and serve as potent deterrents to greenwashing. Regulatory sanctions and penalties, when substantial and compelling, serve as deterrents that transform corporate behavior and market outcomes. Regulatory bodies must balance the need for strict enforcement with the risk of unintended consequences, such as greenhushing. Regulators often operationalize interventions by aligning greenwashing cases with existing laws, transforming the vaguely defined concept into something actionable. To ensure anti-greenwashing practices, mandatory assurance systems should be created. Policymakers must expedite the establishment of a mandatory assurance system for sustainability reports and propose reasonable assurance regulations. Mandatory disclosure should be based on a standardized metric to allow for comparison and external verification, making the signal credible.

- 2.

- Stakeholder engagement. Stakeholder engagement leverages market pressures and external scrutiny to enforce compliance. Stakeholder engagement acts as a critical deterrent by leveraging competitive and reputational pressures. Investors, media, and NGOs serve as watchdogs, inspecting corporate conduct and demanding accountability. Standardization makes sustainability reports more user-friendly, thereby amplifying stakeholder participation and scrutiny, and directly linking standardization efforts to market enforcement. Policymakers should leverage stakeholder engagement to curb greenwashing. Encouraging shareholders and stakeholders to demand evidence for environmental claims and advocate for stricter regulations strengthens accountability.

- 3.

- Assurance and standardization. Standardization and third-party verification (assurance) provide a common language and independent oversight, enabling regulators and stakeholders to effectively scrutinize corporate claims. Standardization promotes uniformity in metrics and reporting formats, which reduces the likelihood of greenwashing by making symbolic compliance more challenging. Mandatory assurance is designed to enhance credibility and reduce greenwashing by ensuring disclosures are more accurate. Assurance, through its supervisory and information-transmission functions, reduces opportunities for greenwashing driven by information asymmetry and regulatory deficiencies. Moreover, assurance providers must employ more rigorous verification procedures and maintain professional skepticism, especially for companies with poor environmental performance. Assurance must encourage substantial actions and discourage symbolic expressions. Assurance procedures should adopt new approaches, such as mandatory linguistic reviews to detect manipulative language patterns. Verify the gap between self-reported ex-ante intentions and ex-post environmental controversies and sanctions.

- 4.

- Corporate culture and internal controls. The mitigation of greenwashing relies significantly on developing internal corporate systems, including the formation of an ethical, continuous-learning corporate culture with robust internal controls and governance structures. These international mechanisms are required since greenwashing often arises from pressures and incentives deeply embedded within the company. An internal accountability mechanism is necessary to foster scrutiny that increases the likelihood and cost of exposure, countering the assumption that greenwashing pays. The need to reform corporate governance structures, establish environmental committees with veto power over greenwashing risks, and link the quality of sustainability reports to executive long-term incentives should be expressed.

- 5.

- Technology deterrents. Technology provides the means for objective data collection and real-time verification. Tools such as blockchain, AI, and IoT/sensors improve supply chain transparency and product lifecycle tracking. Blockchain ensures that environmental records are accurately recorded and not double-counted. AI tools can support regulators by providing relevant data, increasing the volume of reports, and enhancing the quality of disclosures. Emerging technologies provide powerful new tools to enhance the rigor of sustainability assurance and combat increasingly sophisticated forms of greenwashing. By moving beyond traditional document reviews and interviews, technology can enable more direct and continuous verification of corporate claims. Combining regulation with technology can yield powerful deterrents. Additionally, technology can establish a dynamic monitoring system that enables governments and financial institutions to monitor company sustainability data in real time and act quickly when irregularities are found. Moreover, the possibility of using artificial intelligence and machine learning techniques to detect greenwashing presence at the reporting level should be explored. For greenwashing detection, blockchains are necessary to store data, ensuring that data is digitally authenticated and instantly accessible to investors and regulators, and that full-process tracking of environmental actions and their financial impacts is enabled.

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lee, M.T.; Raschke, R.L.; Krishen, A.S. Signaling green! firm ESG signals in an interconnected environment that promote brand valuation. J. Bus. Res. 2023, 138, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capelle-Blancard, G.; Petit, A. Every little helps? ESG news & stock market reaction. J. Bus. Ethics 2019, 157, 543–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galbreath, J. ESG in focus: The Australian evidence. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 118, 529–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flammer, C.; Bansal, P. Does long-term orientation create value? Evidence from a regression discontinuity. Strateg. Manag. J. 2016, 38, 1827–1847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, A.C.; Rezaee, Z. Business sustainability performance and cost of equity capital. J. Corp. Financ. 2015, 34, 128–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miralles-Quiros, M.M.; Miralles-Quiros, J.L.; Redondo-Hernandez, J. ESG Performance and Shareholder Value Creation in the Banking Industry: International Differences. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montgomery, A.W.; Lyon, T.P.; Barg, J. No End in Sight? A Greenwash Review and Research Agenda. Organ. Environ. 2023, 37, 221–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deschryver, P.; de Mariz, F. What Future for the Green Bond Market? How Can Policymakers, Companies, and Investors Unlock the Potential of the Green Bond Market? J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2020, 13, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prakash, A.; Potoski, M. Voluntary environmental programs: A comparative perspective. J. Pol. Anal. Manag. 2012, 31, 123–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siew, R.Y.J. A review of corporate sustainability reporting tools (SRTs). J. Environ. Manag. 2015, 164, 180–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Büyükőzkan, G.; Karabulut, Y. Sustainability performance evaluation: Literature review and future directions. J. Environ. Manag. 2018, 217, 253–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bromley, P.; Powell, W.W. From smoke and mirrors to walking the talk: Decoupling in the contemporary world. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2012, 6, 483–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marquis, C.; Toffel, M.W.; Bird, Y. Scrutiny, norms and selective disclosure: A global study of greenwashing. Organ. Sci. 2016, 27, 483–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Halderen, M.; Bhatt, M.; Berens, G.A.J.M.; Brown, T.J.; Van Riel, C.B.M. Managing impressions in the face of rising stakeholder pressures: Examining oil companies’ shifting stances in the climate change debate. J. Bus. Ethics 2016, 133, 567–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geetha, S.; Biju, A.V.N. Is green FinTech reshaping the finance sphere? Unravelling through a systematic literature review. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 31, 1790–1810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carè, R.; Weber, O. How much finance is in climate finance? A bibliometric review, critiques, and future research directions. Res. Int. Bus. Financ. 2023, 64, 101886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matakanye, R.M.; van der Poll, H.M.; Muchara, B. Do Companies in Different Industries Respond Differently to Stakeholders’ Pressures When Prioritising Environmental, Social and Governance Sustainability Performance? Sustainability 2021, 13, 12022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EFRAG. Digitisation of the European Sustainability Reporting Standard (ESRS). 2022. Available online: https://www.xbrleurope.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/20220613-EFRAG-ESRS-XBRL-Europe-Presentation.pdf (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- Boiral, O.; Heras-Saizarbitoria, I. Sustainability reporting assurance: Creating stakeholder accountability through hyperreality? J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 243, 118596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braga, J.P.; Semmler, W.; Grass, D. De-risking of green investments through a green bond market–Empirics and a dynamic model. J. Econ. Dyn. Control 2021, 131, 104201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uyar, A.; Pizzi, S.; Caputo, F.; Kuzey, C.; Karaman, A.S. Do shareholders reward or punishrisky firms due to CSR reporting and assurance? Manag. Decis. Econ. 2020, 43, 1596–1620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassani, B.K.; Bahini, Y. Relationships between ESG Disclosure and Economic Growth: A Critical Review. J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2022, 15, 538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haji, A.A.; Coram, P.; Troshani, I. Consequences of CSR reporting regulations worldwide: A review and research agenda. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2023, 36, 177–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Free, C.; Jones, S.; Tremblay, M.-S. Greenwashing and sustainability assurance: A review and call for future research. J. Account. Lit. 2024, 47, 739–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asif, M.; Searcy, C. Beyond the green façade: Building a framework to deter ESG greenwashing. Qual. Quant. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bu, M.; Liu, X.; Zhang, B.; Hazaea, S.A.; Fan, R.; Wang, Z. Governance of Corporate Greenwashing through ESG Assurance. Systems 2024, 12, 365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, C.; Shan, Y.G.; Yang, F.; Zhang, Y. The effect of CSR assurance on subsequent corporate greenwashing: Suggestion acquisition or opinion shopping? Br. Account. Rev. 2025, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sneideriene, A.; Legenzova, R. Greenwashing prevention in environmental, social, and governance (ESG) disclosures: A bibliometric analysis. Res. Int. Bus. Financ. 2025, 74, 102720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legenzova, R.; Raudonienė, D. Early evidence on auditor’s intentions and readiness to provide mandatory sustainability reporting assurance services in the European Union: A study of regulatory effect in Lithuania. J. Gov. Reg. 2025, 14, 139–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundarasen, S.; Zyznarska-Dworczak, B.; Goel, S. Sustainability reporting and greenwashing: A bibliometrics assessment in G7 and non-G7 nations. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2024, 11, 2320812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frendy, F.; Oshika, T.; Koike, M. Environmental greenwashing in Japan: The roles of corporate governance and assurance. Meditari Account. Res. 2024, 32, 266–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazaea, S.A.; Zhu, J.; Khatib, S.F.A.; Bazhair, A.H.; Elamer, A.A. Sustainability assurance practices: A systematic review and future research agenda. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 4843–4864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Velte, P. Determinants of the selection of sustainability assurance providers and consequences for firm value: A review of empirical research. Meditari Account. Res. 2025, 33, 443–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spaniol, M.J.; Danilova-Jensen, E.; Nielsen, M.; Rosdahl, C.G.; Schmidt, C.J. Defining Greenwashing: A Concept Analysis. Sustainability 2024, 16, 9055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koch, T.; Denner, N. What is greenwashing—A scoping review of greenwashing definitions and development of the Need-for-Balance Model. J. Sustain. Bus. 2025, 10, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinheiro, A.B.; dos Santos, G.C. Hero or villain? The role of the board of directors in combating greenwashing. J. Manag. Gov. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poiriazi, E.; Zournatzidou, G.; Konteos, G. Do Board Characteristics Matter with Greenwashing? An Investigation in the Financial Sector with the Integration of Entropy Weight and TOPSIS Multicriteria Decision-Making Methods. Risks 2025, 13, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Li, J.; Cheng, L.T.W.; Cao, J. The role of independent directors in mitigating corporate greenwashing: Evidence from board voting in China. Eur. J. Fin. 2025, 31, 1405–1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamil, N.N.; Wahyuni, E.T. Greenwashing and board effectiveness: Moderating role of CSR committee from Malaysia evidence. Edelweiss Appl. Sci. Technol. 2025, 9, 1508–1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgandi, T. Liability for Greenwashing in Company Sustainability Reports: A Novel Application of the English Tort Law Doctrine of Assumption of Responsibility. AJIL Unbound 2024, 118, 274–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballan, B.; Czarnezki, J.J. Disclosure, Greenwashing, and the Future of ESG Litigation. Wash. Lee L. Rev. 2024, 81, 545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillan, S.L.; Koch, A.; Starks, L.T. Firms and social responsibility: A review of ESG and CSR research in corporate finance. J. Corp. Financ. 2021, 66, 101889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, G.; Hu, X.; Chen, X.; Xiao, J. Sustainability Uncertainty and Supply Chain Financing: A Perspective Based on Divergent ESG Evaluations in China. Systems 2025, 13, 850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, E.P.; Luu, B.V.; Chen, C.H. Greenwashing in environmental, social and governance disclosures. Res. Int. Bus. Financ. 2020, 52, 101192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowen, F.E.; Aragon-Correa, J.A. Greenwashing in corporate environmentalism research and practice: The importance of what we say and do. Org. Environ. 2014, 27, 107–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, X. How the market values greenwashing? Evidence from China. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 128, 547–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cremasco, C.; Boni, L. Is the European Union (EU) Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR) effective in shaping sustainability objectives? An analysis of investment funds’ behaviour. J. Sustain. Financ. Invest. 2022, 14, 1018–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sult, A.; Wobst, J.; Lueg, R. The role of training in implementing corporate sustainability: A systematic literature review. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2024, 31, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyon, T.P.; Maxwell, J.W. Greenwash: Corporate environmental disclosure under threat of audit. J. Econ. Manag. Strat. 2011, 20, 3–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyon, T.P.; Lu, Y.; Shi, X.; Yin, Q. How do shareholders respond to Green Company Awards in China? Ecol. Econ. 2013, 94, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crichton, R.; Shrivastava, P.; Walker, T.; Farhidi, F.; Renwick, D.; Ellegate, N. Going green in the Norwegian fossil fuel sector? The case of sustainability culture at Equinor. Germ. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2024, 38, 140–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez Gutierrez-Torrenova, M. Sustainability. The End of Finance as It Was. Estud. Econ. Apl. 2021, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeow, K.E.; Ng, S.-H. The impact of green bonds on corporate environmental and financial performance. Manag. Financ. 2021, 47, 1486–1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernini, F.; Giuliani, M.; La Rosa, F. Measuring greenwashing: A systematic methodological literature review. Bus. Ethics Environ. Response 2023, 33, 649–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatti, L.; Pizzetti, M.; Seele, P. Green lies and their effect on intention to invest. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 17, 228–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walters, R. Varieties of gender wash: Towards a framework for critiquing corporate social responsibility in feminist IPE. Rev. Int. Polit. Econ. 2022, 29, 1577–1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torelli, R. Sustainability, responsibility and ethics: Different concepts for a single path. Soc. Respon. J. 2021, 17, 719–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorfleitner, G.; Utz, S. Green, green, it’s green they say: A conceptual framework for measuring greenwashing on firm level. Rev. Manag. Sci. 2023, 18, 3463–3486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, E. Rethinking Greenwashing: Corporate Discourse, Unethical Practice, and the Unmet Potential of Ethical Consumerism. Sociol. Perspect. 2019, 62, 728–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghitti, M.; Gianfrate, G.; Palma, L. The agency of greenwashing. J. Manag. Gov. 2023, 28, 905–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oppong-Tawiah, D.; Webster, J. Corporate Sustainability Communication as ‘Fake News’: Firms’ Greenwashing on Twitter. Sustainability 2023, 15, 6683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Li, M.; Xu, S. Unveiling the “Veil” of information disclosure: Sustainability reporting “greenwashing” and “shared value”. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0279904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Font, X.; Walmsley, A.; Cogotti, S.; McCombes, L.; Haeusler, N. Corporate social responsibility: The disclosure-performance gap. Tour. Manag. 2012, 33, 1544–1553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alawattage, C.; Jayathileka, C.; Hitibara, R.; Withanage, S. Moral economy, performative materialism, and political rhetorics of sustainability accounting. Critic. Perspect. Account. 2023, 95, 102507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, M.H.; Ali, H.; Mohamed, E.K.A. Corporate social responsibility disclosure on Twitter: Signalling or greenwashing? Evidence from the UK. Int. J. Finance Econ. 2022, 29, 1745–1761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, M.; Mason, R.D. Communicating a Green Corporate Perspective: Ideological Persuasion in the Corporate Environmental Report. J. Bus. Tech. Commun. 2012, 26, 479–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montero-Navarro, A.; Gonzalez-Torres, T.; Rodriguez-Sanchez, J.-L.; Gallego-Losada, R. A bibliometric analysis of greenwashing research: A closer look at agriculture, food industry and food retail. Brit. Food J. 2021, 123, 547–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Chen, L.; Zhang, Y.; Li, W. Environmental disclosure greenwashing” and corporate value: The premium effect and premium devalue of environmental information. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2023, 31, 2424–2438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, A.; Elamer, A.A.; Fletcher, M.; Sobhan, N. Voluntary assurance of sustainability reporting: Evidence from an emerging economy. Account. Res. J. 2020, 33, 391–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Zhu, H.; Meng, Y. ESG greenwashing and equity mispricing: Evidence from China. Finance Res. Lett. 2023, 58, 104606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bendig, D.; Schaper, T.; Erbar, F. Revealing the truth: The moderating role of internal stakeholders in sustainability communication. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 434, 139969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.K.K. Effective Green Alliances: An analysis of how environmental nongovernmental organizations affect corporate sustainability programs. Corp. Soc. Respons. Environ. Manag. 2019, 26, 227–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernini, F.; La Rosa, F. Research in the greenwashing field: Concepts, theories, and potential impacts on economic and social value. J. Manag. Gov. 2024, 28, 405–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linares-Rodriguez, M.C.; Gambetta, N.; Garcia-Benau, M.A. Climate action information disclosure in Colombian companies: A regional and sectorial analysis. Urban Clim. 2023, 51, 101626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greiner, M.; Kim, J. Corporate political activity and greenwashing: CanCPAclarify which firm communications on social & environmental events are genuine? Corp. Soc. Respons. Environ. Manag. 2021, 28, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Y.; Dai, J.; Vasarhelyi, M.A. Audit 4.0-based ESG assurance: An example of using satellite images on GHG emissions. Int. J. Account. Inf. Syst. 2023, 50, 100625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laskin, A.V.; Mikhailovna Nesova, N. The Language of Optimism in Corporate Sustainability Reports: A Computerized Content Analysis. Bus. Prof. Commun. Q. 2022, 85, 80–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Sarkis, J. Corporate social responsibility governance, outcomes, and financial performance. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 162, 1607–1616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Hsieh, T.-S.; Sarkis, J. CSR Performance and the Readability of CSR Reports: Too Good to be True? Corp. Soc. Respons. Environ. Manag. 2018, 25, 66–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilliland, B.; Burton, C.; Lee, C.; Cherniak-Kennedy, A. Climate-related disclosure for Canadian energy companies—Getting ready for the mandatory regime: Voluntary guidelines, rule proposal, governance implications, and best practices to avoid greenwashing allegations. Albany Law Rev. 2023, 61, 353–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, F.; Ding, C.; Yue, W.; Liu, G. ESG performance and corporate risk-taking: Evidence from China. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2023, 87, 102550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lokuwaduge, C.S.D.S.; De Silva, K.M. ESG Risk Disclosure and the Risk of Green Washing. Australs. Account. Bus. Finance J. 2022, 16, 146–159. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, W.; Chen, W.; Fu, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Huang, G.Q. Unsupervised neural network-enabled spatial-temporal analytics for data authenticity under environmental smart reporting system. Comput. Ind. 2022, 141, 103700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Fu, Y.; Wang, Z.; Liu, X.; Niu, Y.; Li, B.; Huang, G.Q. Consortium blockchain-enabled smart ESG reporting platform with token-based incentives for corporate crowdsensing. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2022, 172, 108456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Villiers, C.; Dimes, R.; Molinari, M. How will AI text generation and processing impact sustainability reporting? Critical analysis, a conceptual framework and avenues for future research. Sustain. Account. Manag. Policy J. 2024, 15, 96–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacces, A.M. Will the EU Taxonomy Regulation Foster Sustainable Corporate Governance? Sustainability 2021, 13, 12316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sensharma, S.; Sinha, M.; Sharma, D. Do Indian Firms Engage in Greenwashing? Evidence from Indian Firms. Australas. Account. Bus. Finance J. 2022, 16, 67–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gull, A.A.; Hussain, N.; Khan, S.A.; Mushtaq, R.; Orij, R. The power of the CEO and environmental decoupling. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2023, 32, 3951–3964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhuiyan, F.; Rana, T.; Baird, K.; Munir, R. Strategic outcome of competitive advantage from corporate sustainability practices: Institutional theory perspective from an emerging economy. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2023, 32, 4217–4243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mateo-Marquez, A.J.; Gonzalez-Gonzalez, J.M.; Zamora-Ramirez, C. An international empirical study of greenwashing and voluntary carbon disclosure. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 363, 132567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Dagestani, A.A. Greenwashing behavior and firm value—From the perspective of board characteristics. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2023, 30, 2330–2343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zharfpeykan, R. Representative account or greenwashing? Voluntary sustainability reports in Australia’s mining/metals and financial services industries. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2021, 30, 2209–2223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Xing, X.; He, Y.; Gu, X. Combating greenwashers in emerging markets: A game-theoretical exploration of firms, customers and government regulations. Transp. Res. E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2020, 140, 101976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teichmann, F.M.J.; Wittmann, C.; Sergi, B.S.S. What are the consequences of corporate greenwashing? A look into the consequences of greenwashing in consumer and financial markets. J. Inf. Commun. Ethics Soc. 2023, 21, 290–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beloskar, V.D.; Haldar, A.; Rao, S.V.D.N. Socially responsible investments: A retrospective review and future research agenda. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2023, 32, 4841–4860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.C.B.; Cruz, J.M.; Shankar, R. Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) Issues in Supply Chain Competition: Should Greenwashing Be Regulated? Decis. Sci. 2018, 49, 1088–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koseoglu, M.A.; Uyar, A.; Kilic, M.; Kuzey, C.; Karaman, A.S. Exploring the connections among CSR performance, reporting, and external assurance: Evidence from the hospitality and tourism industry. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 94, 102819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larcker, D.F.; Tayan, B.; Watts, E.M. Seven myths of ESG. Europ. Financ. Manag. 2022, 28, 869–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nofsinger, J.R.; Varma, A. Keeping Promises? Mutual Funds’ Investment Objectives and Impact of Carbon Risk Disclosures. J. Bus. Ethics 2023, 187, 493–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bager, S.L.; Lambin, E.F. Sustainability strategies by companies in the global coffee sector. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2020, 29, 3555–3570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wichianrak, J.; Khan, T.; Teh, D.; Dellaportas, S. Critical Perspectives of NGOs on Voluntary Corporate Environmental Reporting: Thai Public Listed Companies. Sustainability 2023, 15, 6195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vangeli, A.; Lecka, A.M.; Ega, M.M.; Pfajfar, G. From greenwashing to green B2B marketing: A systematic literature review. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2023, 115, 281–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Syst. Rev. 2021, 10, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Meyst, K.J.L.; Cardinaels, E.; van den Abbeele, A. CSR disclosures in buyer-seller markets: The impact of assurance of CSR disclosures and incentives for CSR investments. Account. Organ. Soc. 2024, 113, 101498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vera-Muñoz, S.C. CSR disclosures in buyer-seller markets: Research design issues, greenwashing and regulatory implications, and directions for future research. Account. Organ. Soc. 2024, 113, 101537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datt, R.; Luo, L.; Segara, R. Voluntary carbon assurance and the cost of equity capital: International evidence. Aust. J. Manag. 2024, 50, 1129–1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrido, D.; Espinola-Arredondo, A.; Munoz-Garcia, F. Can mandatory certification promote greenwashing? A signaling approach. J. Public Econ. Theory 2020, 22, 1801–1851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Shi, Y.; Jia, M. Greenwashing: A systematic literature review. Account. Financ. 2025, 65, 857–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, S.; Tan, S.; Zhou, S. Greenwashing on the Regulatory Agenda: How Regulators Make Greenwashing Governable. SSRN Electron. J. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley, C.M. It’s Not Easy Being Anti-Greenwashing. SSRN Electron. J. 2024, 4784535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Mahjoub, L. Greenwashing practices and ESG reporting: An international review. Int. J. Sociol. Soc. Policy 2025, 45, 173–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Chen, Y. Watchdogs or Enablers? Analyzing the Role of Analysts in ESG Greenwashing in China. Sustainability 2024, 16, 4339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanor, A.; Light, S.E. Greenwashing and the First Amendment. Columbia Law Rev. 2022, 122, 2033–2118. [Google Scholar]

- Hilton, J. Greenhush and greenwash: A signalling game analysis of strategic environmental disclosure. Environ. Dev. Econ. 2025, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.; Huang, H.; Liu, F.; Sethi, S.; Xing, X.; Zhan, Y. Strategic Blockchain Adoption for Anti-Greenwashing. SSRN Electron. J. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mezzanotte, F.E. Corporate sustainability reporting: Double materiality, impacts, and legal risk. J. Corp. Law Stud. 2023, 23, 633–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregory, R.P. When is greenwashing an easy fix? J. Sustain. Financ. Invest. 2023, 13, 919–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obeng, V.A.; Farooq, M.B.; Miglani, S.; Jalali, F. Sustainability assurance quality and board gender diversity: Moderating role of assurance level and provider type on the extent of assurance procedures. J. Account. Organ. Change 2025, 21, 90–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gourier, E.; Mathurin, H. A Greenwashing Index. SSRN Electron. J. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peixoto, N.O.; de Almeida, N.S. Greenwashing: A systematic review of the literature on forms of identification and their determining factors. Reun.-Rev. Adm. Contab. 2024, 14, 66–80. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrón-Vílchez, V.; Valero-Gil, J.; Suárez-Perales, I. How does greenwashing influence managers’ decision-making? An experimental approach under stakeholder view. Corp. Cos. Respons. Environ. Manag. 2021, 28, 860–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, V. Corporate greenwashing and green management indicators. Environ. Sustain. Ind. 2025, 26, 100599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poll, J. Auditing, supervising and enforcing corporate sustainability due diligence, disclosure and reporting. ERA Forum 2023, 24, 599–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, S.S.; Zambrana Roman, C.E.; Juma, N.A. Voluntary Audits of Nonfinancial Disclosure and Earnings Quality. J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2025, 18, 256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shui, Z.L.; Wang, H.; Xin, C.K.; Xue, R. Unintended societal outcome of investor protection: Independent director liability and greenwashing. J. Account. Lit. 2025, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durmuş Şenyapar, H.N. Unveiling greenwashing strategies: A comprehensive analysis of impacts on consumer trust and environmental sustainability. J. Energ. Syst. 2024, 8, 164–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Tang, L.; Zhao, L. Impact of banks’ ESG disclosure assurance on borrowers’ ESG performance: Evidence from China. Chin. J. Popul. Resour. Environ. 2025, 23, 337–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, H.R.; Musamih, A.; Salah, K.H.; Jayaraman, R.; Omar, M.A.; Arshad, J.; Boscovic, D.M. Smart agriculture assurance: IoT and blockchain for trusted sustainable produce. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2024, 224, 109184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendes, J.A.J.; Oliveira, A.Y.; Santos, L.S.; Gerolamo, M.C.; Zeidler, V.G.Z. A theoretical framework to support green agripreneurship avoiding greenwashing. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2025, 27, 21779–21835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sneideriene, A.; Legenzova, R. Uncovering Greenwashing: Investigating Impression Management Gap in Corporate Reporting. Sustainability 2025, 17, 8342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Sneideriene, A.; Legenzova, R. A Framework for Mitigating Greenwashing in Sustainability Reporting. Sustainability 2026, 18, 524. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010524

Sneideriene A, Legenzova R. A Framework for Mitigating Greenwashing in Sustainability Reporting. Sustainability. 2026; 18(1):524. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010524

Chicago/Turabian StyleSneideriene, Agne, and Renata Legenzova. 2026. "A Framework for Mitigating Greenwashing in Sustainability Reporting" Sustainability 18, no. 1: 524. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010524

APA StyleSneideriene, A., & Legenzova, R. (2026). A Framework for Mitigating Greenwashing in Sustainability Reporting. Sustainability, 18(1), 524. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010524