Comparing Metal Additive Manufacturing with Conventional Manufacturing Technologies: Is Metal Additive Manufacturing More Sustainable?

Abstract

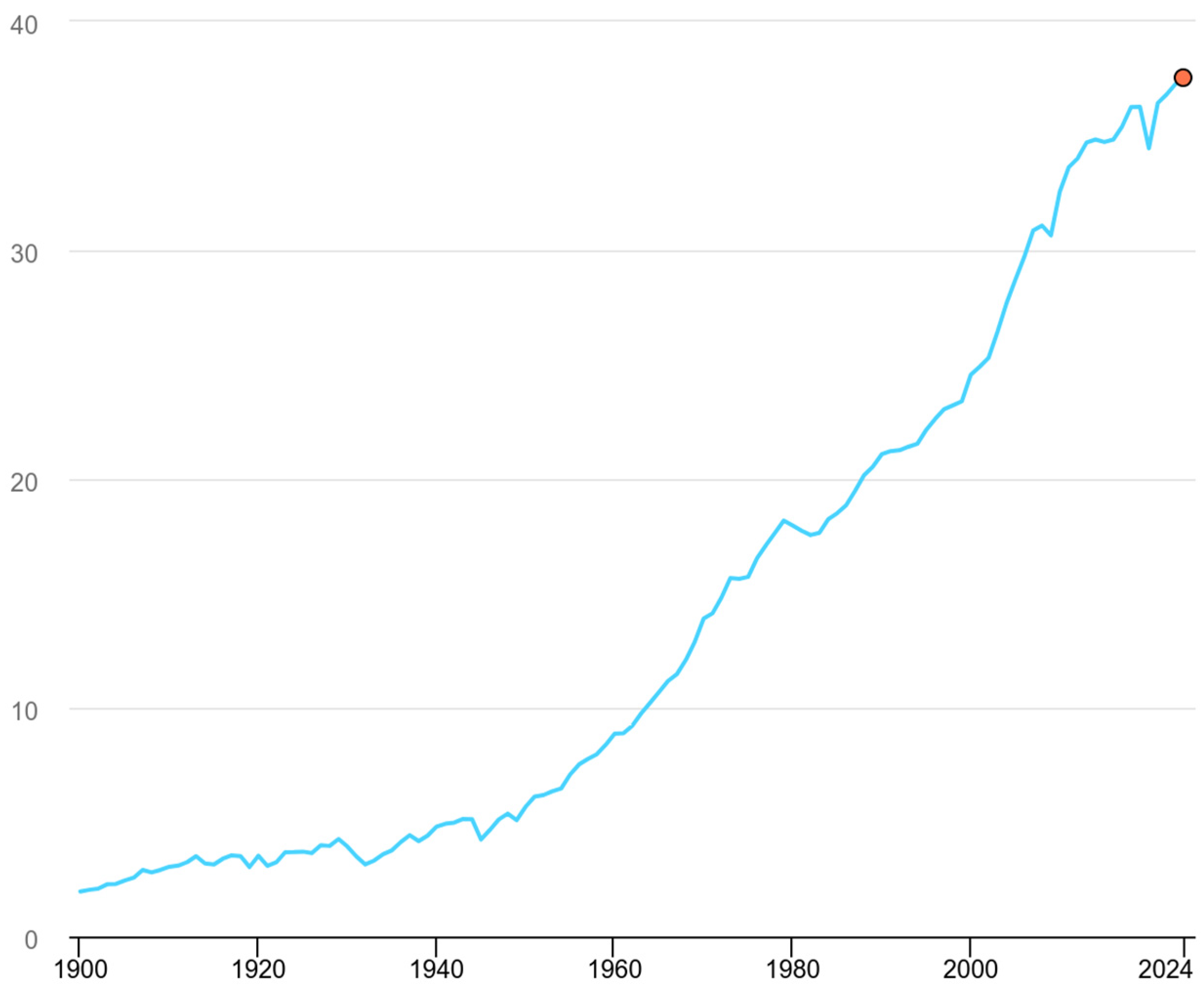

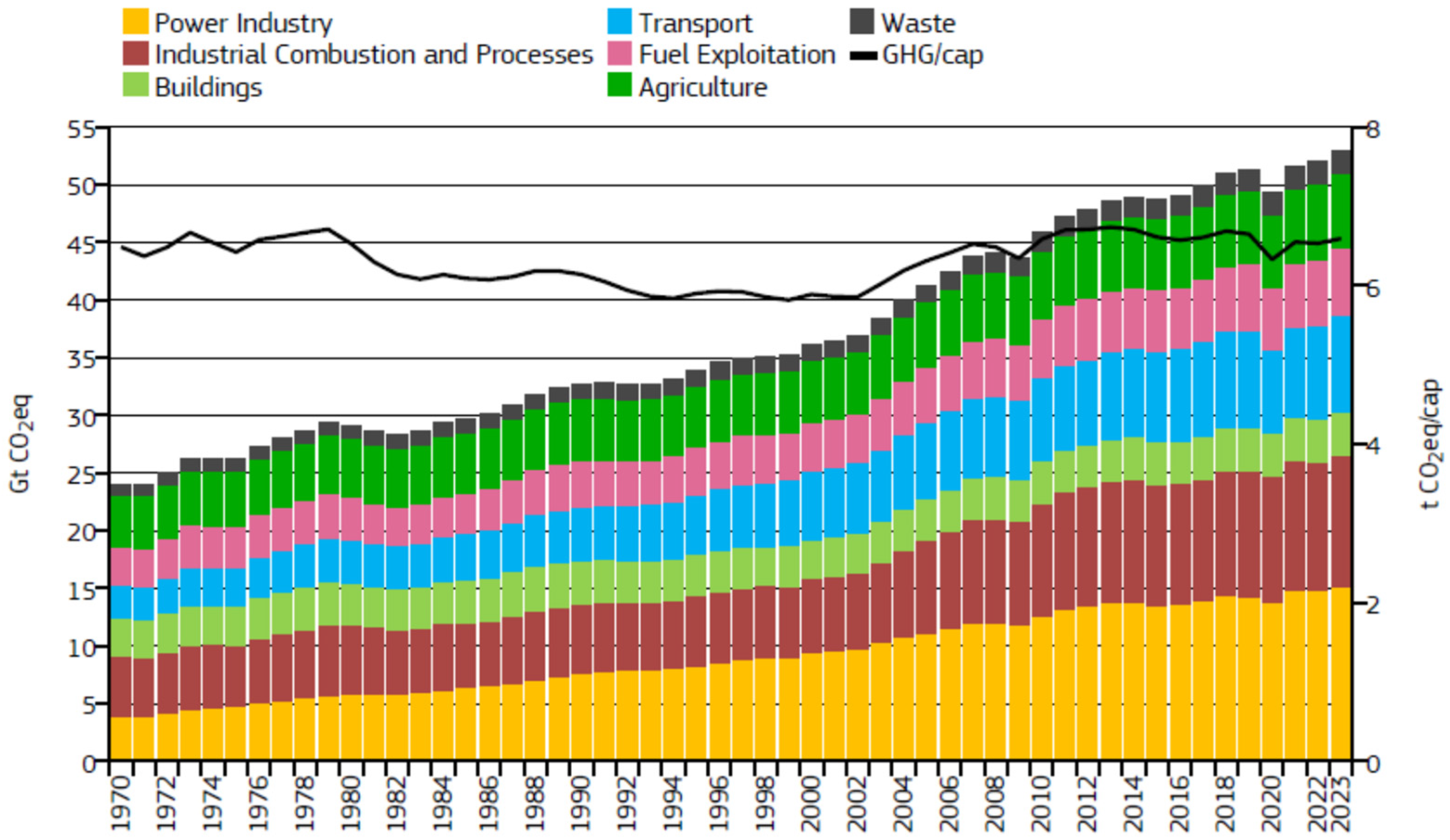

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Exploratory Study

2.2. Review Plan and Protocol

- Objective: To determine whether mAM technologies are more sustainable than conventional manufacturing (CM) methods.

- Definition of conceptual boundaries: The scope of this investigation was limited to metal manufacturing across several industrial sectors, including general industry, automotive, aerospace, space, and dentistry. The study sought to derive its conclusions from empirical data; that is, information obtained through experimentation and measurement.

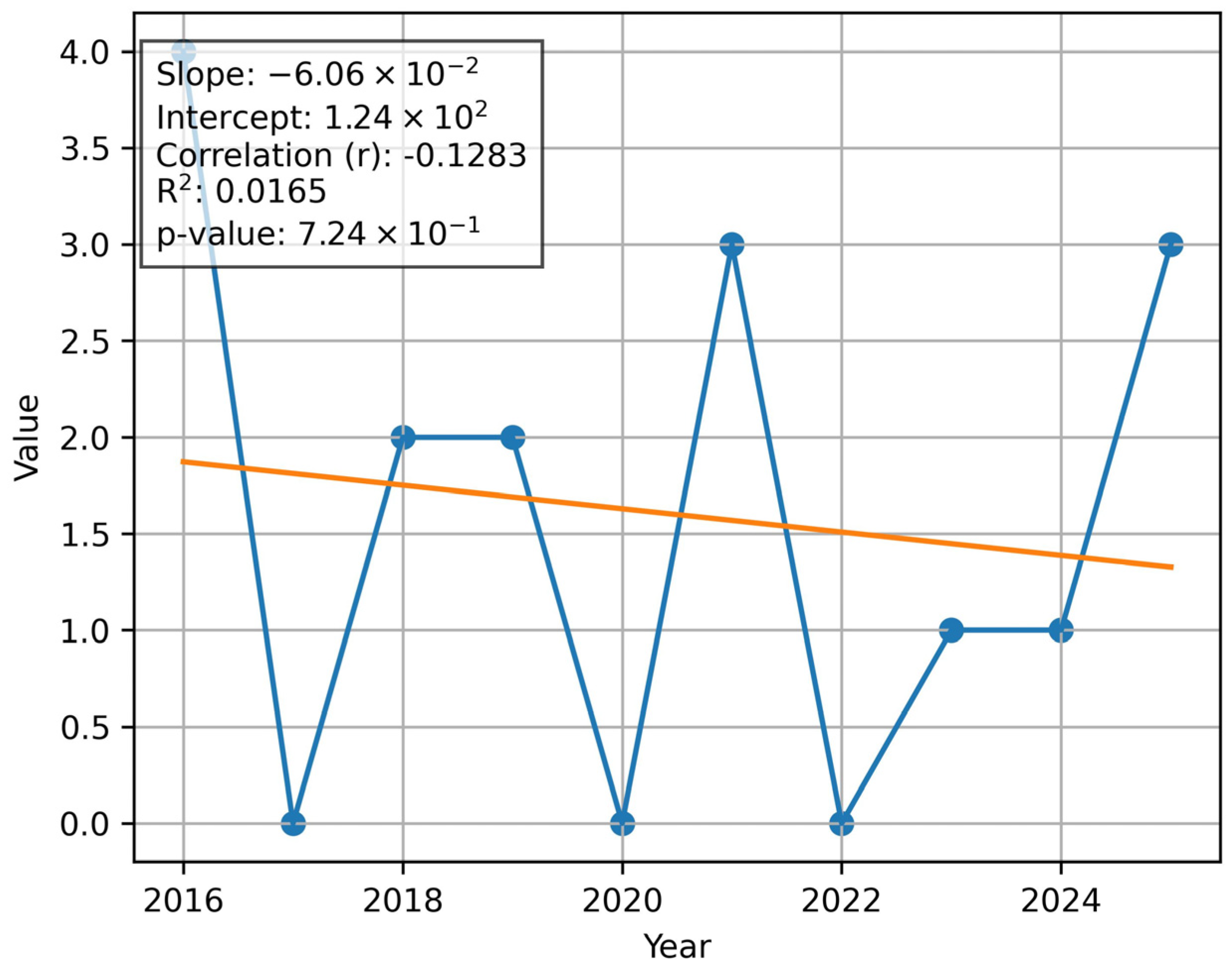

- Search strategy: The literature search was conducted using two academic databases: Scopus and the Web of Science (WoS). The review focused primarily on papers published in peer-reviewed journals, most of which are ranked in Q1 according to the Journal Citation Reports (JCR) or the SCImago Journal Rank (SJR).

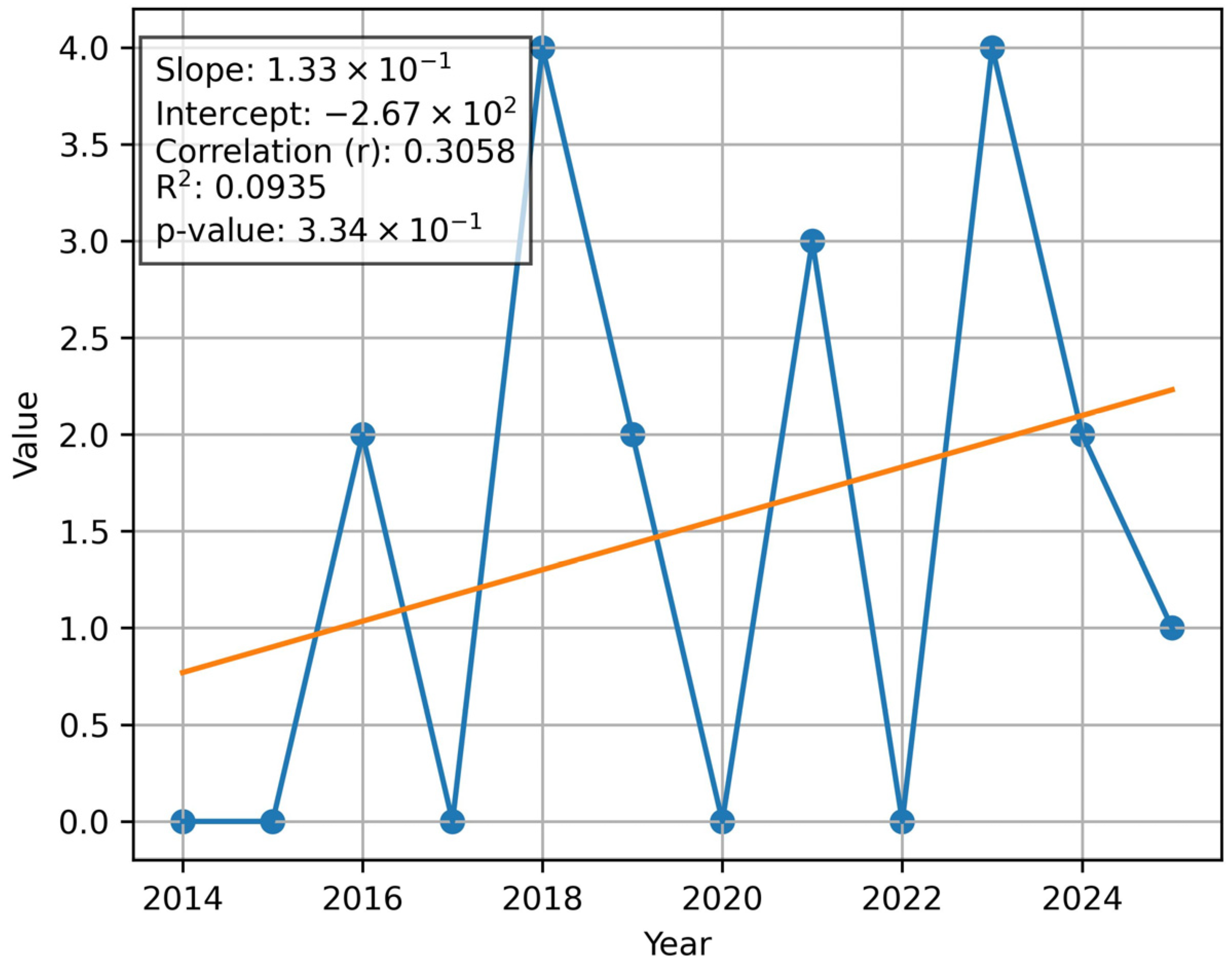

- Inclusion criteria: Peer-reviewed articles and conference papers, published between 2014 and July 2025, written in English, focused on metal manufacturing sectors (general industry, automotive, aerospace, space, dentistry), and containing empirical data.

- Exclusion criteria: Books and book chapters, papers on plastics and construction industries. Books and book chapters were excluded, not because they lack value, but because the objective of a scientific article is to present the latest and most rigorous empirical evidence, which is predominantly found in peer-reviewed journals and conference papers and therefore considered the highest standard of source material.

2.3. Question Formulation

2.4. Locating Studies

- Group A (sustainability): LCA, LCC, life cycle assessment, life cycle costing, social impact indicators.

- Group B (mAM): rapid prototyping, metal additive manufacturing, metal 3D printing.

- Group C (CM): conventional manufacturing, subtractive manufacturing, traditional manufacturing.

2.5. Search Query for Reproducibility

- The search was conducted on the Scopus and Web of Science (WoS) databases. The final, search query, utilizing Boolean operators, was performed in three steps to make sure it was accurate and captured all the necessary information from the databases.

- 1. Step: Initial search (Group A):The search tool in each database was used to extract all articles discussing the three dimensions of sustainability (“LCA” OR “LCC” OR “life cycle assessment” OR “life cycle costing” OR “social impact indicators”).

- 2. Step: Next refine (Group B):Then, the database filter tool was used to reduce the resulting articles, keeping only those that also matched the other two groups (AND “rapid prototyping” OR “metal additive manufacturing” OR “metal 3D printing”).

- 3. Step: Final refine (Group C):AND (“conventional manufacturing” OR “subtractive manufacturing” OR “traditional manufacturing”).

2.6. Selection and Evaluation

- Duplicate removal: 38 duplicate records were eliminated.

- Application of the predefined exclusion criteria resulted in the removal of 51 papers.

- Identification of false positives: Abstracts were reviewed to exclude papers not relevant to the research focus, resulting in the elimination of 121 papers.

- Identification of doubtful articles: Introductions and conclusions were read to identify papers of uncertain relevance; 33 papers were excluded.

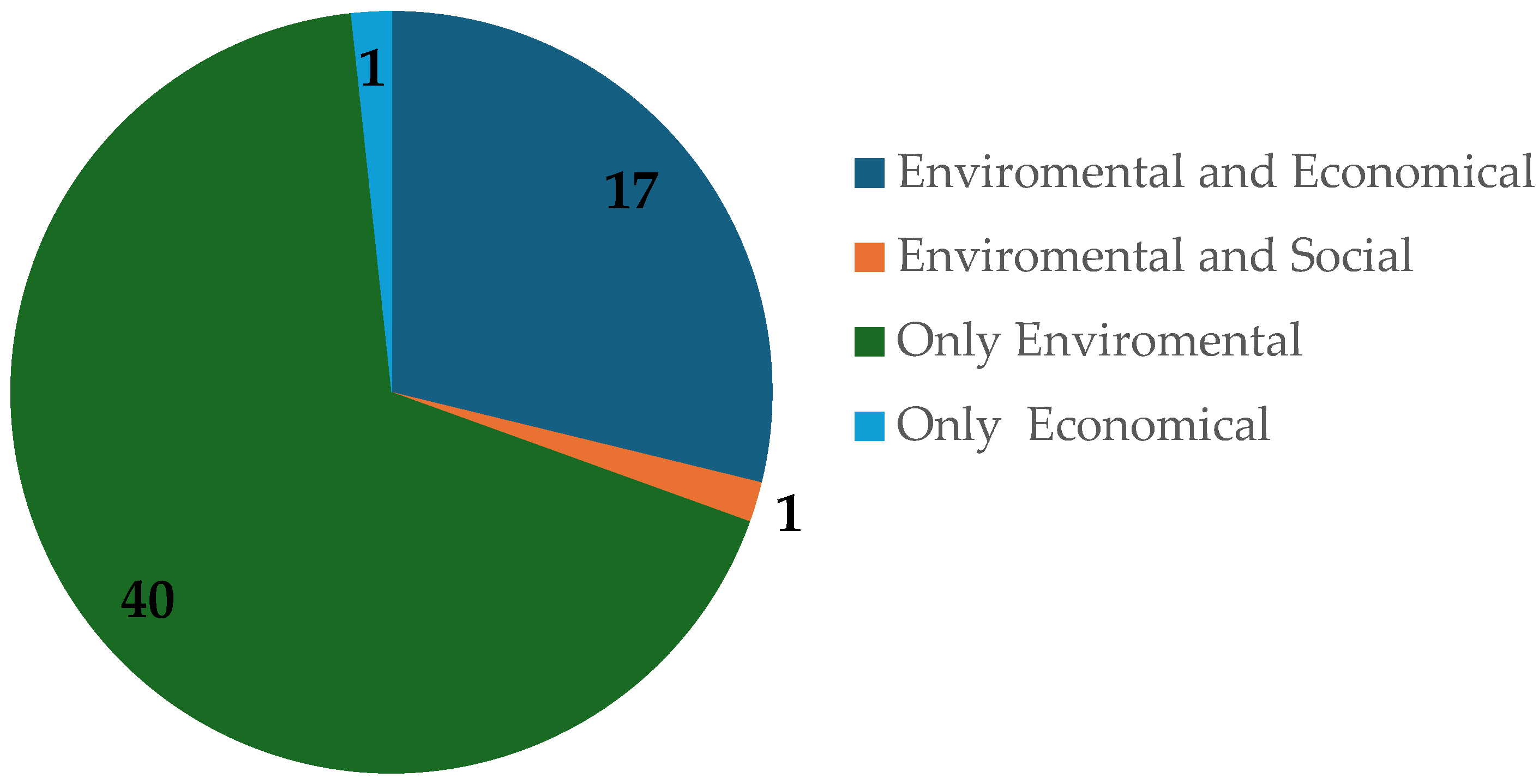

3. Results

3.1. Environmental Sustainability Results

3.2. Economical Sustainability Results

3.3. Social Sustainability Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Environmental Sustainability Discussion

4.2. Economical Sustainability Discussion

4.3. Social Sustainability Discussion

4.4. Limitations

5. Conclusions

6. Recommendations

- Prioritize economic cost reduction: Research must focus on improving cost-efficiency. This requires reducing the high initial capital investment in mAM machinery and the steep cost of metal powders. Costs can be lowered through improved deposition rates, optimized build orientation, increased energy efficiency, and greater material recyclability.

- Integrate LCC and LCA: Future studies must integrate life cycle costing (LCC) alongside life cycle assessment (LCA). Since economic viability is the main barrier to industrial adoption, demonstrating cost-effectiveness is essential before environmental or social benefits can support implementation. Broader use of LCC is needed.

- Adopt cradle-to-grave standardization: A cradle-to-grave system boundary should be adopted whenever possible, as it is the only way to capture the critical long-term benefits resulting from weight reduction and use-phase efficiency.

- Advance social impact quantification: Future research must establish frameworks like the UNEP/SETAC guidelines to develop clearer, quantitative S-LCA indicators. The immediate priority is to quantify risks related to worker health and safety (powder and VOC exposure).

- Define clear targets for sustainable mAM adoption: Industry and researchers should collaborate to define measurable performance standards, such as minimum weight-saving targets or maximum viable batch sizes, to clarify the conditions under which mAM is guaranteed to surpass CM.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AM-SC | Additive manufacturing-assisted sand casting |

| AM | Additive manufacturing |

| ASTM | American Society for Testing and Materials |

| BJ-BJT | Binder jetting |

| BMD | Bound metal deposition |

| BPE | Bound powder extrusion |

| CM | Conventional manufacturing |

| CNC | Computer numerical control |

| CSAM | Cold spray additive manufacturing |

| DED | Directed energy deposition |

| DMLS | Direct metal laser sintering |

| EBM | Electron beam melting |

| EDM | Electrical discharge machining |

| FDM | Fused deposition modeling |

| HDMR | Hybrid deposition micro rolling |

| HIP | Hot isostatic pressing |

| HMP | Hybrid machining processes |

| ISO | International Organization for Standardization |

| LBM | Laser beam melting |

| LCA | Life cycle assessment |

| LCC | Life cycle cost |

| L-PBF | Laser powder bed fusion |

| mAM | Metal additive manufacturing |

| MIM | Metal injection molding |

| MM | Multi-axis milling |

| PA-WAAM | Plasma arc–wire arc AM |

| RQ | Research question |

| SLM | Selective laser melting |

| SLR | Systematic literature review |

| S-LCA | Social life cycle assessment |

| SR | Stress relief |

| PBF | Powder bed fusion |

| TO | Topological optimization |

| VOCs | Volatile organic compounds |

| WAAM | Wire arc additive manufacturing |

| WoS | Web of Science |

References

- Global Energy Review 2025. Available online: https://www.iea.org/data-and-statistics/charts/global-co2-emissions-from-energy-combustion-and-industrial-processes-and-their-annual-change-1900-2023 (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Emissions of All World Countries 2024. Available online: https://edgar.jrc.ec.europa.eu/booklet/GHG_emissions_of_all_world_countries_booklet_2024report.pdf (accessed on 10 November 2024).

- Freeman, R.E. Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Brundtland, G.H. Our Common Future-Call for action. Environ. Conserv. 1987, 14, 291–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkington, J.; Rowlands, I.H. Cannibals with forks: The triple bottom line of 21st century business. Altern. J. 1999, 25, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilhelm, M.; Wissenbach, K.; Gasser, A. Shaped Body Especially Prototype or Replacement Part Production. German Patent DE19649865C1, 12 February 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Wilhelm, M.; Wissenbach, K.; Gasser, A. Selective Laser Sintering at Melting Temperature. U.S. Patent 6,215,093, 10 April 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Jeantette, F.P.; David, M.K.; Joseph, A.R.; Lee, P.S. Method and System for Producing Complex-Shape Objects. U.S. Patent 6,046,426, 4 April 2000. [Google Scholar]

- ISO/ASTM 52900; Additive Manufacturing—General Principles—Fundamentals and Vocabulary. International Organization for Standardization/ASTM International: Geneva, Switzerland; West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2021.

- Snyder, H. Literature review as a research methodology: An overview and guidelines. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 104, 333–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seuring, S.; Müller, M. From a literature review to a conceptual framework for sustainable supply chain management. J. Clean. Prod. 2008, 16, 1699–1710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tranfield, D.; Denyer, D.; Smart, P. Towards a methodology for developing evidence-informed management knowledge by means of systematic review. Br. J. Manag. 2003, 14, 207–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Moher, D. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, N.; Enemuoh, E.U. Energy modeling and eco impact evaluation in direct metal laser sintering hybrid milling. Heliyon 2020, 6, e03168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hettesheimer, T.; Hirzel, S.; Ross, H.B. Energy savings through additive manufacturing: An analysis of selective laser sintering for automotive and aircraft components. Energy Effic. 2018, 11, 1227–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ott, K.; Pascher, H.; Sihn, W. Improving sustainability and cost efficiency for spare part allocation strategies by utilisation of additive manufacturing technologies. In Sustainable Manufacturing for Global Circular Economy, Proceedings of the 16th Global Conference on Sustainable Manufacturing (GCSM 2018), Lexington, KY, USA, 2–4 October 2018; Seliger, G., Jawahir, I.S., Badurdeen, F., Kohl, H., Eds.; Elsevier B.V.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; pp. 123–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, I.; Matos, F.; Jacinto, C.; Salman, H.; Cardeal, G.; Carvalho, H.; Peças, P. Framework for life cycle sustainability assessment of additive manufacturing. Sustainability 2020, 12, 929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrizubieta, J.I.; Ukar, O.; Ostolaza, M.; Mugica, A. Study of the environmental implications of using metal powder in additive manufacturing and its handling. Metals 2020, 10, 261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colorado, H.A.; Velásquez, E.I.G.; Monteiro, S.N. Sustainability of additive manufacturing: The circular economy of materials and environmental perspectives. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2020, 9, 8221–8234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Favi, C.; Murgese, L.; Villazzi, N.; Gallozzi, S.; Mandolini, M.; Marconi, M. Integrating life cycle engineering into design for additive manufacturing: A review. J. Manuf. Syst. 2025, 82, 599–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, S.; Despeisse, M. Additive manufacturing and sustainability: An exploratory study of the advantages and challenges. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 137, 1573–1587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, C.; Wolff, S.; Wang, S. Eco-friendly additive manufacturing of metals: Energy efficiency and life cycle analysis. J. Manuf. Syst. 2021, 60, 459–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegab, H.; Khanna, N.; Monib, N.; Salem, A. Design for sustainable additive manufacturing: A review. Sustain. Mater. Technol. 2023, 35, e00576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.H.; Liu, P.; Mokasdar, A.; Hou, L. Additive manufacturing and its societal impact: A literature review. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2013, 67, 1191–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellens, K.; Baumers, M.; Gutowski, T.G.; Flanagan, W.; Lifset, R.; Duflou, J.R. Environmental Dimensions of Additive Manufacturing Mapping Application Domains and Their Environmental Implications. J. Ind. Ecol. 2017, 21, S49–S68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokare, S.; Oliveira, J.P.; Godina, R. Life cycle assessment of additive manufacturing processes: A review. J. Manuf. Syst. 2023, 68, 536–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokare, S.; Godina, R.; Oliveira, J.P. Life Cycle Inventory of Additive Manufacturing Processes: A Review. In Springer Proceedings in Business and Economics; de Oliveira Matias, J.C., Oliveira Pimentel, C.M., Gonçalves dos Reis, J.C., Costa Martins das Dores, J.M., Santos, G., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 77–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, H.; Carmona-Aparicio, G.; Lei, I.; Despeisse, M. Energy and material efficiency strategies enabled by metal additive manufacturing—A review for the aeronautic and aerospace sectors. Energy Rep. 2022, 8, 298–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moura, B.; Monteiro, H. Current development of the metal additive manufacturing sustainability—A systematic review. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2025, 112, 107778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niaki, M.K.; Nonino, F.; Palombi, G.; Torabi, S.A. Economic sustainability of additive manufacturing Contextual factors driving its performance in rapid prototyping. J. Manuf. Technol. Manag. 2019, 30, 353–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilz, T.L.; Nunes, B.; Corrêa Maceno, M.M.; Cleto, M.G.; Seleme, R. Systematic analysis of comparative studies between additive and conventional manufacturing focusing on the environmental performance of logistics operations. Gest. Prod. 2020, 27, e5289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pusateri, V.; Hauschild, M.Z.; Kara, S.; Goulas, C.; Olsen, S.I. Quantitative sustainability assessment of metal additive manufacturing: A systematic review. CIRP J. Manuf. Sci. Technol. 2024, 49, 95–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raoufi, K.; Sutherland, J.W.; Zhao, F.; Clarens, A.F.; Rickli, J.L.; Fan, Z.; Haapala, K.R. Current state and emerging trends in advanced manufacturing: Process technologies. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2024, 135, 4089–4118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saade, M.R.M.; Yahia, A.; Amor, B. How has LCA been applied to 3D printing? A systematic literature review and recommendations for future studies. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 244, 118803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, J.; Ng, W.L.; An, J.; Yeong, W.Y.; Chua, C.K.; Sing, S.L. Achieving sustainability by additive manufacturing: A state-of-the-art review and perspectives. Virtual Phys. Prototyp. 2024, 19, e2438899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Výtisk, J.; Kočí, V.; Honus, S.; Vrtek, M. Current options in the life cycle assessment of additive manufacturing products. Open Eng. 2020, 9, 674–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wurst, J.; Mozgova, I.; Lachmayer, R. Sustainability Assessment of Products Manufactured by the Laser Powder Bed Fusion (LPBF) Process. In Procedia CIRP; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022; pp. 243–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadegari, M.J.; Martucci, A.; Biamino, S.; Ugues, D.; Montanaro, L.; Fino, P.; Lombardi, M. Aluminum Laser Additive Manufacturing: A Review on Challenges and Opportunities Through the Lens of Sustainability. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 2221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mami, F.; Revéret, J.-P.; Fallaha, S.; Margni, M. Evaluating Eco-Efficiency of 3D Printing in the Aeronautic Industry. J. Ind. Ecol. 2017, 21, S37–S48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekker, A.C.M.; Verlinden, J.C. Life cycle assessment of wire + arc additive manufacturing compared to green sand casting and CNC milling in stainless steel. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 177, 438–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Jiang, Q.; Cong, W.; Li, T.; Zhang, H.-C. Comparative study for environmental performances of traditional manufacturing and directed energy deposition processes. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2018, 15, 2273–2282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raoufi, K.; Haapala, K.R.; Etheridge, T.; Manoharan, S.; Paul, B.K. Cost and environmental impact assessment of stainless steel microscale chemical reactor components using conventional and additive manufacturing processes. J. Manuf. Syst. 2022, 62, 202–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santiago-Herrera, M.; Igos, E.; Alegre, J.M.; Martel-Martín, S.; Barros, R. Ex-ante life cycle assessment of directed energy deposition based additive manufacturing: A comparative gearbox production case study. Sustain. Mater. Technol. 2024, 39, e00819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verdi, D.; Joju, J.; Larsen, A.; Chia, G.Y.; Tay, G.; Yang, S.S. Environmental Performance Analysis of Hybrid Manufacturing of Closed Impellers. In Materials Today: Proceedings; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022; pp. 289–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cappucci, G.M.; Pini, M.; Neri, P.; Marassi, M.; Bassoli, E.; Ferrari, A.M. Environmental sustainability of orthopedic devices produced with powder bed fusion. J. Ind. Ecol. 2020, 24, 681–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laghi, V.; Savino, E.; Gasparini, G. Reduction of the environmental impact of complex-shaped steel joints through topology optimization and large-scale metal 3D printing. Results Eng. 2025, 27, 105610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokare, S.; Oliveira, J.P.; Godina, R. A LCA and LCC analysis of pure subtractive manufacturing, wire arc additive manufacturing, and selective laser melting approaches. J. Manuf. Process. 2023, 101, 67–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mecheter, A.; Tarlochan, F.; Kucukvar, M. A Review of Conventional versus Additive Manufacturing for Metals: Life-Cycle Environmental and Economic Analysis. Sustainability 2023, 15, 12299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamps, T.; Lutter-Guenther, M.; Seidel, C.; Gutowski, T.; Reinhart, G. Cost- and energy-efficient manufacture of gears by laser beam melting. CIRP J. Manuf. Sci. Technol. 2018, 21, 47–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyamekye, P.; Unt, A.; Salminen, A.; Piili, H. Integration of Simulation Driven DfAM and LCC Analysis for Decision Making in L-PBF. Metals 2020, 10, 1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopal, M.; Lemu, H.G.; Gutema, E.M. Sustainable Additive Manufacturing and Environmental Implications: Literature Review. Sustainability 2023, 15, 504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNEP/SETAC. Guidelines for Social Life Cycle Assessment of Products and Organisations, 3rd ed.; United Nations Environment Programme: Paris, France, 2020; Available online: https://www.lifecycleinitiative.org (accessed on 6 December 2025).

- Anspach, R.L.; Gill, H.S.; Dhokia, V.; Lupton, R.C. High tibial osteotomy and additive manufacture can significantly reduce the climate impact of surgically treating knee osteoarthritis. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2025, 30, 1651–1665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Böckin, D.; Tillman, A.-M. Environmental assessment of additive manufacturing in the automotive industry. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 226, 977–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeBoer, B.; Nguyen, N.; Diba, F.; Hosseini, A. Additive, subtractive, and formative manufacturing of metal components: A life cycle assessment comparison. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2021, 115, 413–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Lorenzo, R.; Ingarao, G.; Lupo, D.; Palmeri, D.; Fratini, L. A methodological framework to model cumulative energy demand and production costs for additive and conventional manufacturing approaches. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2024, 63, 3117–3141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, M.; Pragana, J.P.M.; Ferreira, B.; Ribeiro, I.; Silva, C.M.A. Economic and Environmental Potential of Wire-Arc Additive Manufacturing. Sustainability 2022, 14, 5197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, B.; Brandao, F.; Borille, A.; Goncalves, A.; Leite, M.; Ribeiro, I. Assessment of the technical, environmental and economic trade-offs in the early stage of metal additive manufacturing adoption. Prog. Addit. Manuf. 2025, 10, 10371–10393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredriksson, C. Sustainability of Metal Powder Additive Manufacturing. In Sustainable Manufacturing for Global Circular Economy; Seliger, G., Jawahir, I., Badurdeen, F., Kohl, H., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; pp. 139–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, A.; Ferreira, B.; Leite, M.; Ribeiro, I. Environmental and Economic Sustainability Impacts of Metal Additive Manufacturing: A Study in the Industrial Machinery and Aeronautical Sectors. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2023, 42, 292–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gotlih, J.; Brezocnik, M.; Pal, S.; Drstvensek, I.; Karner, T.; Brajlih, T. A Holistic Approach to Cooling System Selection and Injection Molding Process Optimization Based on Non-Dominated Sorting. Polymers 2022, 14, 4842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouveia, J.R.; Pinto, S.M.; Campos, S.; Matos, J.R.; Sobral, J.; Esteves, S.; Oliveira, L. Life Cycle Assessment and Cost Analysis of Additive Manufacturing Repair Processes in the Mold Industry. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouveia, J.R.; Pinto, S.M.; Campos, S.; Matos, J.R.; Costa, C.; Dutra, T.A.; Oliveira, L. Life Cycle Assessment of a Circularity Case Study Using Additive Manufacturing. Sustainability 2022, 14, 9557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, R.; Riddle, M.; Graziano, D.; Warren, J.; Das, S.; Nimbalkar, S.; Masanet, E. Energy and emissions saving potential of additive manufacturing: The case of lightweight aircraft components. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 135, 1559–1570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, R.; Riddle, M.E.; Graziano, D.; Das, S.; Nimbalkar, S.; Cresko, J.; Masanet, E. Environmental and Economic Implications of Distributed Additive Manufacturing: The Case of Injection Mold Tooling. J. Ind. Ecol. 2017, 21, S130–S143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingarao, G.; Priarone, P.C.; Deng, Y.; Paraskevas, D. Environmental modelling of aluminium based components manufacturing routes: Additive manufacturing versus machining versus forming. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 176, 261–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayawardane, H.; Davies, I.J.; Gamage, J.R.; John, M.; Biswas, W.K. Investigating the ‘techno-eco-efficiency’ performance of pump impellers: Metal 3D printing vs. CNC machining. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2022, 121, 6811–6836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokare, S.; Oliveira, J.P.; Santos, T.G.; Godina, R. Environmental and economic assessment of a steel wall fabricated by wire-based directed energy deposition. Addit. Manuf. 2023, 61, 103316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokare, S.; Shen, J.; Fonseca, P.P.; Lopes, J.G.; Machado, C.M.; Santos, T.G.; Godina, R. Wire arc additive manufacturing of a high-strength low-alloy steel part: Environmental impacts, costs, and mechanical properties. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2024, 134, 453–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, D.; Palanisamy, S.; Krishnan, K.; Alam, M.M. Life Cycle Assessment of Cold Spray Additive Manufacturing and Conventional Machining of Aluminum Alloy Flange. Metals 2023, 13, 1684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, V.T.; Paris, H. A life cycle assessment-based approach for evaluating the influence of total build height and batch size on the environmental performance of electron beam melting. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2018, 98, 275–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, V.T.; Paris, H.; Mandil, G. Environmental impact assessment of an innovative strategy based on an additive and subtractive manufacturing combination. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 164, 508–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, J.; De Kleine, R.; Kim, H.C.; Luckey, G.; Forsmark, J.; Lee, E.C.; Cooper, D.R. Assessing the sustainability of laser powder bed fusion and traditional manufacturing processes using a parametric environmental impact model. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2023, 198, 107138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zhao, G.; Zhang, H.; Huang, C.; Hou, F.; Wang, G.; Zhang, H. The carbon emission comparison between hybrid manufacturing and conventional processes based on bionic computing of industrial metabolism. Energy Rep. 2022, 8, 420–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lostado-Lorza, R.; Corral-Bobadilla, M.; Sabando-Fraile, C.; Somovilla-Gómez, F. Enhancing thermal conductivity of sinterized bronze (Cu89/Sn11) by 3D printing and thermal post-treatment: Energy efficiency and environmental sustainability. Energy 2024, 299, 131435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyons, R.; Newell, A.; Ghadimi, P.; Papakostas, N. Environmental impacts of conventional and additive manufacturing for the production of Ti-6Al-4V knee implant: A life cycle approach. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2021, 112, 787–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maheshwari, P.; Khanna, N.; Hegab, H.; Singh, G.; Sarıkaya, M. Comparative environmental impact assessment of additive-subtractive manufacturing processes for Inconel 625: A life cycle analysis. Sustain. Mater. Technol. 2023, 37, e00682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrow, W.R.; Qi, H.; Kim, I.; Mazumder, J.; Skerlos, S.J. Environmental aspects of laser-based and conventional tool and die manufacturing. J. Clean. Prod. 2007, 15, 932–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paris, H.; Mokhtarian, H.; Coatanea, E.; Museau, M.; Ituarte, I.F. Comparative environmental impacts of additive and subtractive manufacturing technologies. CIRP Ann. Manuf. Technol. 2016, 65, 29–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, S.; Li, T.; Wang, X.; Dong, M.; Liu, Z.; Shi, J.; Zhang, H. Toward a Sustainable Impeller Production: Environmental Impact Comparison of Different Impeller Manufacturing Methods. J. Ind. Ecol. 2017, 21, S216–S229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, T.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Yang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Tang, R. Life cycle assessment of selective-laser-melting-produced hydraulic valve body with integrated design and manufacturing optimization: A cradle-to-gate study. Addit. Manuf. 2020, 36, 101530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priarone, P.C.; Catalano, A.R.; Settineri, L. Additive manufacturing for the automotive industry: On the life-cycle environmental implications of material substitution and lightweighting through re-design. Prog. Addit. Manuf. 2023, 8, 1229–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priarone, P.C.; Ingarao, G.; di Lorenzo, R.; Settineri, L. Influence of Material-Related Aspects of Additive and Subtractive Ti-6Al-4V Manufacturing on Energy Demand and Carbon Dioxide Emissions. J. Ind. Ecol. 2017, 21, S191–S202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priarone, P.C.; Lunetto, V.; Atzeni, E.; Salmi, A. Laser Powder Bed Fusion (L-PBF) Additive Manufacturing: On the Correlation between Design Choices and Process Sustainability. In Procedia CIRP, Proceedings of the 6th CIRP Global Web Conference—Envisaging the Future Manufacturing, Design, Technologies and Systems in Innovation Era (CIRPE 2018), Online, 23–25 October 2018; Simeone, A., Priarone, P., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; pp. 85–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramadugu, S.; Ledella, S.R.K.; Gaduturi, J.N.J.; Pinninti, R.R.; Sriram, V.; Saxena, K.K. Environmental life cycle assessment of an automobile component fabricated by additive and conventional manufacturing. Int. J. Interact. Des. Manuf. 2024, 18, 847–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raoufia, K.; Manoharana, S.; Etheridge, T.; Paul, B.K.; Haapala, K.R. MIM. In Procedia CIRP, Proceedings of the 48th SME North American Manufacturing Research Conference, NAMRC 48, Cincinnati, OH, USA, 22–26 June 2020; Fratini, L., Ragai, I., Wang, L., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 311–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reis, R.C.; Kokare, S.; Oliveira, J.P.; Matias, J.C.O.; Godina, R. Life cycle assessment of metal products: A comparison between wire arc additive manufacturing and CNC milling. Adv. Ind. Manuf. Eng. 2023, 6, 100117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, M.; Heinrich, J.; Huensche, I. Carbon Footprint of Additively Manufactured Precious Metals Products. Resources 2024, 13, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segovia-Guerrero, L.; Balades, N.; Gallardo-Galan, J.J.; Gil-Mena, A.J.; Sales, D.L. Additive vs. Subtractive Manufacturing: A Comparative Life Cycle and Cost Analyses of Steel Mill Spare Parts. J. Manuf. Mater. Process. 2025, 9, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, I.H.; Hadjipantelis, N.; Walter, L.; Myers, R.J.; Gardner, L. Environmental life cycle assessment of wire arc additively manufactured steel structural components. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 389, 136071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sword, J.I.; Galloway, A.; Toumpis, A. An environmental impact comparison between wire + arc additive manufacture and forging for the production of a titanium component. Sustain. Mater. Technol. 2023, 36, e00600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Mak, K.; Zhao, Y.F. A framework to reduce product environmental impact through design optimization for additive manufacturing. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 137, 1560–1572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, C.; Duenas, L.; Misra, S.; Chaitanya, V. Specific energy consumption based comparison of distributed additive and conventional manufacturing: From cradle to gate partial life cycle analysis. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 425, 138762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trapani, M.G.; Di Lorenzo, R.; Fratini, L.; Ingarao, G. A flexible decision support tool for the green selection of additive over subtractive manufacturing approaches. J. Clean. Prod. 2025, 519, 146024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vytisk, J.; Honus, S.; Kočí, V.; Pagáč, M.; Hajnyš, J.; Vujanovic, M.; Vrtek, M. Comparative study by life cycle assessment of an air ejector and orifice plate for experimental measuring stand manufactured by conventional manufacturing and additive manufacturing. Sustain. Mater. Technol. 2022, 32, e00431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Peng, T.; Zhu, Y.; Yang, Y.; Tang, R. A comparative life cycle assessment of a selective-laser-melting-produced hydraulic valve body using design for Property. In Procedia CIRP; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 220–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, A.; Garg, R.K.; Sachdeva, A.; Qureshi, M.R.N.M. Comparing environmental sustainability of additive manufacturing and investment casting: Life cycle assessment of Aluminium LM04 (Al-Si5-Cu3). Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2025, 923, 147765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, A.; Garg, R.K.; Sachdeva, A. LCA-based environmental insights on sand casting vs. AM-assisted sand casting of Al-Si5-Cu3: Assessing net-zero potential in foundries. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2025, 942, 148674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Min, W.; Ghibaudo, J.; Zhao, Y.F. Understanding the sustainability potential of part consolidation design supported by additive manufacturing. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 232, 722–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Condition for mAM with Less Environmental Impact | Cases (%) | PBF and PBF Hybrid | DED and DED Hybrid | BJ | MEX and MEX Hybrid |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part Redesign with Topology Optimization | 29% | 22% | 5% | 1% | 1% |

| No Specific Conditions Required | 23% | 8% | 10% | 1% | 4% |

| Limited Production Batch Size | 15% | 8% | 5% | 1% | 1% |

| High Material Removal Required in CM | 15% | 10% | 5% | 0% | 0% |

| Use of Renewable/Low-Carbon Energy | 14% | 10% | 1% | 0% | 3% |

| Complex Part Geometry | 13% | 10% | 3% | 0% | 0% |

| Use of Recycled Material | 8% | 8% | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| Extended Part Life/Use Phase Benefits | 5% | 5% | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| Other Conditions | 30% | 17% | 10% | 3% | 0% |

| Boundary Scope | Total Cases (%) | Where mAM < CM | Cases (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cradle to Gate | 45% | 41% | 45% |

| Cradle to Grave | 40% | 39% | 40% |

| Cradle to Gate | 8% | 8% | 8% |

| Gate to Use | 5% | 4% | 5% |

| Others | 2% | 2% | 2% |

| Case Studies | Case Study Application Area | Where mAM < CM | Where mAM ≥ CM | Cradle to Gate | Cradle to Grave | Gate to Gate | Others |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 26% | Industrial parts | 25.00 | 1.19 | 19.05% | 5.95% | 3.57% | 0.00% |

| 20% | Metal parts | 19.05 | 1.19 | 14.29% | 1.19% | 4.76% | 0.00% |

| 18% | Automotive parts | 16.67 | 1.19 | 2.38% | 14.29% | 1.19% | 0.00% |

| 18% | Aeronautical industry parts | 16.67 | 1.19 | 3.57% | 10.71% | 3.57% | 0.00% |

| 7% | Mold parts | 7.14 | 0.00 | 1.19% | 3.57% | 0.00% | 2.38% |

| 5% | Medical parts | 4.76 | 0.00 | 0.00% | 4.76% | 0.00% | 0.00% |

| 4% | Chemical industry part | 2.38 | 1.19 | 3.57% | 0.00% | 0.00% | 0.00% |

| 2% | Others | 1.19 | 1.19 | 2.38% | 0.00% | 0.00% | 0.00% |

| Condition for mAM Being Cheaper than CM | Cases (%) | PBF and PBF Hybrid | DED |

|---|---|---|---|

| No conditions required | 6% | 0% | 6% |

| Part redesign with topology optimization (TO) | 47% | 12% | 35% |

| Limited batch number | 35% | 6% | 29% |

| Batches with more than a given number of parts | 18% | 12% | 6% |

| Other | 41% | 24% | 18% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Villafranca, J.; Veiga, F.; Martin, M.A.; Uralde, V.; Villanueva, P. Comparing Metal Additive Manufacturing with Conventional Manufacturing Technologies: Is Metal Additive Manufacturing More Sustainable? Sustainability 2026, 18, 512. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010512

Villafranca J, Veiga F, Martin MA, Uralde V, Villanueva P. Comparing Metal Additive Manufacturing with Conventional Manufacturing Technologies: Is Metal Additive Manufacturing More Sustainable? Sustainability. 2026; 18(1):512. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010512

Chicago/Turabian StyleVillafranca, Javier, Fernando Veiga, Miguel Angel Martin, Virginia Uralde, and Pedro Villanueva. 2026. "Comparing Metal Additive Manufacturing with Conventional Manufacturing Technologies: Is Metal Additive Manufacturing More Sustainable?" Sustainability 18, no. 1: 512. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010512

APA StyleVillafranca, J., Veiga, F., Martin, M. A., Uralde, V., & Villanueva, P. (2026). Comparing Metal Additive Manufacturing with Conventional Manufacturing Technologies: Is Metal Additive Manufacturing More Sustainable? Sustainability, 18(1), 512. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010512