1. Introduction

Recommender systems (RS) are widely recognised as essential tools for optimising supply chain operations, enabling dynamic matching between purchasers and procurement demands to improve overall responsiveness [

1]. Under disruptive scenarios such as logistics delays or material shortages, alternative solutions can be rapidly identified, thereby mitigating operational risks [

2]. However, conventional recommendation approaches heavily rely on historical interaction data. When new products or purchasers with limited records are encountered, the effectiveness of recommendations is often compromised—a phenomenon known as the cold-start problem [

3].

Some works explore the integration of side information into RS to solve the cold-start problem. Side information can be easily obtained in real-world scenarios, including text [

4], user/item attributes [

5], images [

6], and context data [

7]. Among various forms of side information, knowledge graphs (KGs) are network structures composed of nodes and edges that contain rich relational and semantic data. KGs have been successfully applied in various domains, including search engines [

8], question answering [

9], and word embeddings [

10].

The application of KGs in recommendation systems has been extensively studied in recent years. KG-based recommendation systems primarily utilise semantic and relational information to capture fine-grained relationships between users and items, enabling personalised recommendations. MKR [

11] is a multi-task feature learning approach that integrates KG embedding (KGE) into recommendation systems. RippleNet [

12] employs preference propagation along KG links to uncover users’ hierarchical interests and enrich their embeddings. KGCN [

13] combines neighbourhood and biased information to represent entities within the KG. KGAT [

14] addresses user preference recommendations by focusing on similar users and items. The method expands paths between users and items by considering path propagation across various relationships within the KG. DKEN [

15] models the semantics of the entity and relationship in the KG using deep learning and KGE techniques. KGIN [

16] employs multiple potential intents to model user–item relationships and uses relationship path-aware aggregation to highlight the dependence of relationships in long-term interactions.

KG-based methods are widely used to help supply chain management [

17,

18,

19,

20]. The structured relationship mapping between entities in KGs can also alleviate the cold-start problem in supply chain recommendation. The buyer attributes, production dynamics, and logistics status information can be integrated into the semantically related knowledge map. The structural information and semantic information of the knowledge map enrich the feature representation of buyers and products with insufficient historical interactive data, so as to realise personalised and accurate recommendations. This method can achieve dynamic and efficient matching between suppliers and purchasing demands to improve the responsiveness and flexibility of the entire supply chain. In disruptive scenarios such as logistics delays, material shortages, or geopolitical events, effective recommendations enable rapid identification of alternative suppliers or materials, thereby reducing operational risks.

In this paper, we propose a recommendation system that simultaneously extracts purchaser and product features utilising semantic and relational information from the KG called KnoChain. Inspired by RippleNet [

12], KnoChain expands the purchasers’ feature by applying the outward propagation technique, utilising higher-order structural information from the KG. The product’s feature is enhanced by aggregating adjacent entity information inward from the KG using common graph convolution methods. KnoChain aims to simultaneously extract purchaser and product features by mining multi-hop relationships and higher-order semantic information between entities. The model is applied to click through rate (CTR) prediction experiments on movie, book, and music datasets. The experimental results demonstrate that the proposed model achieves average AUC gains of 9.36%, 5.91%, and 8.81%, as well as average ACC gains of 8.56%, 6.27%, and 8.67% across the movie, book, and music datasets, compared to several advanced approaches. Experimental results demonstrate the effectiveness of the dual-path framework, where purchaser behaviours are propagated to capture implicit preferences, while product characteristics are aggregated to improve representation learning.

The main contributions of this paper are summarised as follows:

We propose a novel bidirectional feature expansion framework that learns purchaser and product features in supply chain recommendation. Utilising the semantic and connective information of KG, the sparsity and cold-start problems can be alleviated.

We simultaneously design an outward propagation mechanism to expand user representations and an inward aggregation mechanism to enrich item representations, enabling a more holistic capture of supply chain entity relationships.

We validate the superiority of the proposed method over several state-of-the-art baselines through comprehensive experiments on three benchmark datasets, with detailed analysis on hyper-parameter sensitivity and component effectiveness.

To provide a clearer roadmap for this study, we explicitly state the core research questions (RQs) that guide our work. These RQs articulate how KG information can be leveraged to jointly enrich purchaser preferences and product features, how the proposed bidirectional feature expansion framework operates, and how its design choices affect recommendation performance—especially under data sparsity and cold-start conditions. Each RQ is addressed through the model design (

Section 3), empirical evaluation (

Section 4), discussion (

Section 5), and analysis of practical implications (

Section 6).

Explicit Research Questions RQ1: How can purchaser preferences and product features be co-enriched from a KG to alleviate data sparsity and cold-start issues in supply chain recommendation? (Answered in:

Section 3—preference propagation and information aggregation modules;

Section 4—cold-start/sparse-case experiments). RQ2: Can a bidirectional feature expansion framework that uses outward propagation for purchasers and inward aggregation for products effectively learn joint representations? What are its core mechanisms? (Answered in:

Section 3.2—framework design and algorithm). RQ3: How does KnoChain perform relative to state-of-the-art baselines across datasets and tasks (e.g., movie/book/music CTR prediction), and how large are the improvements in sparse or cold-start scenarios? (Answered in:

Section 4.4—comparative experiments and results). RQ4: Which model components and hyperparameters (e.g., hop number H, receptive-field depth N, interest-set size M, neighbour sampling K, aggregator choice) most strongly influence performance and robustness? (Answered in:

Section 4.5—parameter analysis and ablation studies). RQ5: To what extent can results obtained on public recommendation datasets transfer to real supply chain deployments, and what are the next steps for constructing supply chain-specific interaction data and KG? (Addressed in:

Section 4.1—concept mapping;

Section 6—limitations and future work).

We will answer these RQs by describing KnoChain’s bidirectional propagation–aggregation architecture (

Section 3), validating its effectiveness through systematic experiments and ablations (

Section 4), discussing key points (

Section 5), and future steps for supply chain-specific deployment (

Section 6).

3. Method

This section will describe the problem formulation and then demonstrate the model’s overall framework, including preference propagation, information aggregation, recommendation module, and learning algorithm.

3.1. Problem Formulation

In supply chain management, the recommendation problem involves matching supply chain actors (procurement managers, plants) with relevant supply chain resources (suppliers, raw materials, logistics services). Let

denote the set of purchasers and

denote the set of products. The purchaser–product interaction matrix is defined as

according to the implicit feedback of purchasers.

= 1 indicates that there is an implicit interaction between purchaser

u and product

v, such as clicking, browsing or purchasing, otherwise

= 0. In addition to the interaction matrix

Y, there is also a KG

G available, which is composed of massive entity-relation-entity triples (

h,

r,

t). Here,

,

and

denote the head, relation, and tail of a knowledge triple, respectively.

and

denote the set of entities and relations in the KG. When the purchaser–product interaction matrix

Y and the KG

G are given, the model aims to learn a prediction function

, which denotes the probability that purchaser

u will interact with product

v and

denotes the model parameters of the function

F. The key notations are summarised in

Table 1.

3.2. Framework of KnoChain

Figure 1 shows KnoChain’s architecture. It models complex, multi-hop relationships in supply chains. The model takes a purchaser

u and a product

v as input and outputs the predicted probability

that

u will buy

v.

For the input purchaser u, his historical interest set expands along the link to form the high-order interest set . The high-order interest set ... is far from the historical interest set h-order. These high-order interest sets are used to interact iteratively with the product embedding to get the response of purchaser u to the product v, which are then combined to form the final H-order purchaser vector representation . Purchasers’ potential interests can be viewed as layered extensions of their historical interests in the knowledge graph, activated by past interactions and progressively propagated along graph links.

For the input product v, firstly, the multi-hop parameter N needs to be set, and the neighbourhood entities set of product v within N hops is regarded as the receptive field . The purchaser-relation score is used as a weight to compute the corresponding neighbourhood representation vector . Finally, the multi-hop neighbour vector representation and entity representation are aggregated to obtain the final N-order product vector representation .

In the end, according to the vector representation of purchaser and product , the predicted probability is calculated.

3.2.1. Preference Propagation

In this section, we will show the process of purchaser feature expansion in detail. It employs outward propagation to refine the purchaser representation from the structural information of the KG. To depict the extended preferences of purchasers over KG, we recursively define the

h-order-related entity set of purchaser

u as follows:

where

is the historical interest sets of purchaser.

Next, we define the

h-order interest set of purchaser

u:

From the above expression, we know that the purchaser’s potential interest is activated by its historical interest and spreads outward layer-by-layer along with the connection of the KG. The high-order interest set may become larger and larger and the purchaser’s interest intensity will gradually weaken as the number of orders h increases. Given this problem, attention should be paid to the following:

In practical operation, the further the distance of the relevant entity from the purchaser’s historical interest is, the more noise may be generated, so the maximum order

H should not be too large. We will discuss the choice of

H in

Section 4.

In KnoChain, to reduce overhead computation, it is unnecessary to use the complete high-order interest set but to sample the neighbour set of a fixed size. We will discuss the choice of size of the high-order interest set

M in each hop in

Section 4.

Next, we will compute the relevance probability. In the relational space

, the similarity between the product

v and the head

is compared in the triple

:

where

and

are the embeddings of relation

and head

, respectively.

After the relevance probability is calculated, the corresponding weights of each tail

in

are weighted and summed to obtain the vector

:

where

is the embedding of the tail;

can be seen as the 1-order response of the purchaser’s click history

concerning product

v.

It should be pointed out here that to repeat the process of preference propagation to obtain the second-order response of purchaser u, v in Equation (3) needs to be replaced by . This process can be iteratively used on the high-order interest set of purchaser u when .

When h = H, the responses of different orders are as follows:

. These responses are added up to the embedding of purchaser

u:

3.2.2. Information Aggregation

This section will introduce the product feature expansion process in detail. It uses inward aggregation to refine the product representation from their multi-hop neighbours. First of all, the process of product expansion in a single layer is introduced, where the entities set directly connected to v is represented by , and the relationship between entities and is represented by .

shows the importance of relation

r to purchaser

u:

To make better use of the neighbourhood information of product

v, we linearly combine all neighbourhood entities of product

v, and

e is the neighbourhood entity:

is the normalised purchaser-relation score.

Because we need to aggregate neighbourhoods with bias based on these purchaser-specific scores, purchaser-relation scores act as an attentional mechanism when calculating the neighbourhood representation of an entity.

In a practical recommendation, we only need to select a neighbour set of a fixed size for each entity. In

Section 4, we will discuss the size of parameter

K.

After the neighbourhood representation is calculated, we aggregate it with the entity representation v and form 1-order vector representation of the product. In the process of aggregation, there are three types of aggregators:

Sum Aggregator

Firstly, the two representation vectors are added together, and then a nonlinear transformation is performed:

W and

b are the transformation weight and bias, respectively;

is the nonlinear function ReLU.

Concat Aggregator [41]

Firstly, the two representation vectors are concatenated, then a nonlinear transformation is carried out:

Neighbour Aggregator [42]

Outputs the neighbourhood representation of entity

v directly:

Since the feature representation of an product is generated by aggregating its neighbours, aggregation is a crucial part of the model, and we will evaluate the three aggregators in the experiment.

In the previous module, the 1-order entity representation is derived from aggregating the entity itself and its neighbours. To mine the features of products from multiple dimensions, we need to extend the above process from one layer to multiple layers. The process works like this: First, the entity itself can obtain the 1-order entity feature representation by aggregating with its neighbour entities. Then, we repeat the process. The 1-order representation is propagated and aggregated to obtain the 2-order representation. The above steps are repeated for N times to get an N-order representation of an entity . As a result, the N-order representation of entity v is obtained by aggregating its own features with those of its N-hop neighbours.

3.2.3. Recommendation Module

Through the purchaser feature expansion module and product feature expansion module described above, we get the expanded purchaser feature representation and product feature representation. Two terms are inputted into the prediction function to calculate the probability that purchaser

u clicks on product

v;

is the sigmoid function:

3.2.4. Learning Algorithm

Equation (

13) illustrates the loss function:

In the above equation, the first term is the cross-entropy loss between the ground truth of the implicit relation matrix

Y and the predicted value of KnoChain. The second term calculates the squared loss between the ground truth of

and the reconstructed indicator matrix

in the KG. The last is the regularisation term.

and

are the balancing parameters. Among them,

V and

E are the embedding matrices of items and all entity items, respectively. The learning algorithm of KnoChain is presented in Algorithm 1.

| Algorithm 1: KnoChain algorithm |

Input: Interaction matrix Y; knowledge graph G; Output: Prediction function ; 1: Initial all parameters; 2: Calculate the interest sets for each purchaser u; Calculate the receptive field Z for each product v; 3: For number of training iteration do For do For do ; ; ; For do For do ; ; ; ; ; 4: Calculate predicted probability ; Update parameters by gradient descent; |

To make the computation more efficient in each training iteration, we employ the stochastic gradient descent (SGD) algorithm when iteratively optimising the loss function. The gradients of the loss L concerning the model parameter are then calculated, and all parameters are updated based on the back-propagation of a small batch of samples. In the experimental section of the next chapter, we will discuss the selection of hyper-parameters.

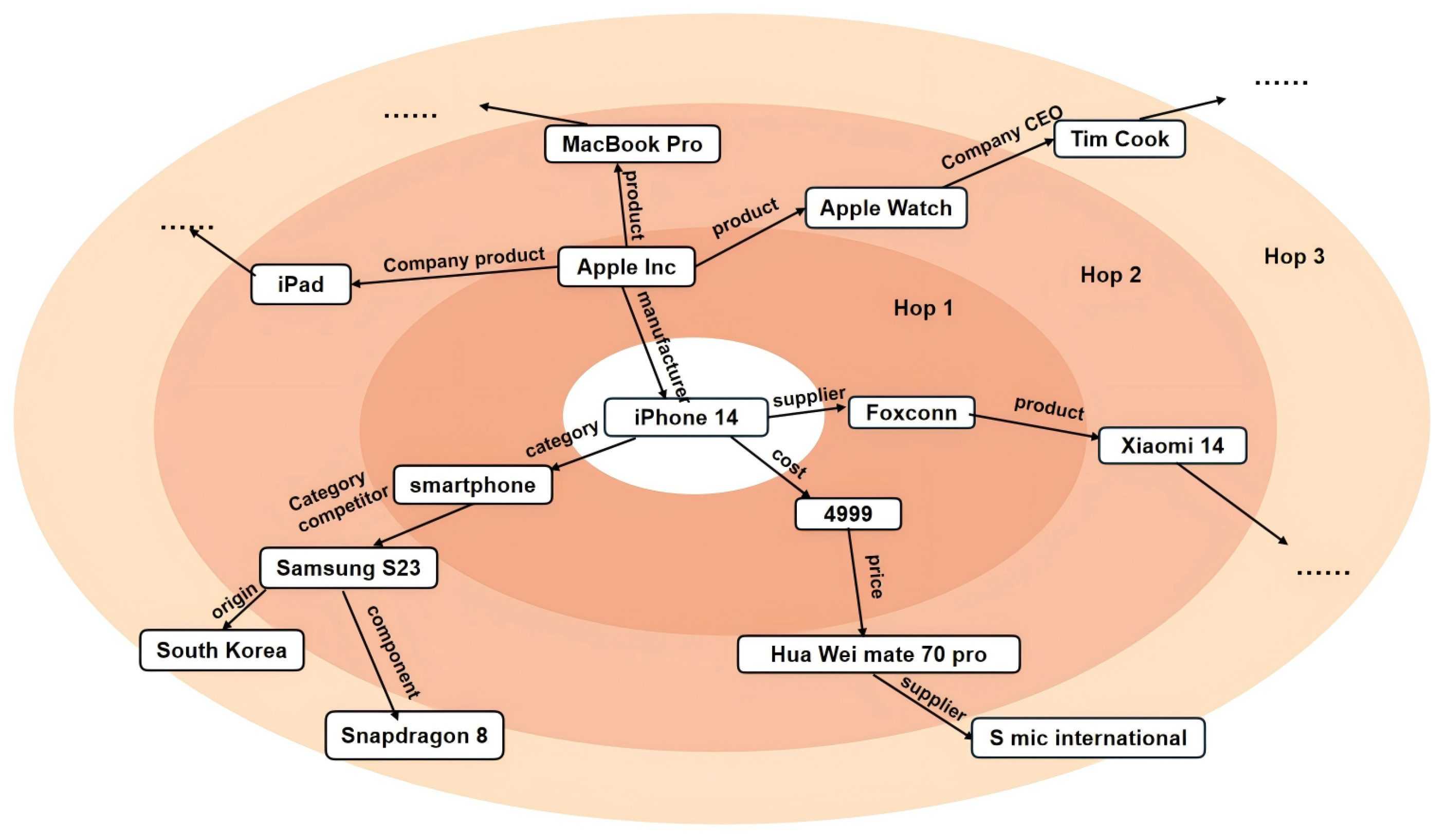

3.3. Explainability

Figure 2 aims to reveal why a purchaser might be interested in another product after multi-hop in KG, which helps improve the understanding of the proposed model. KnoChain explores purchasers’ interests based on the KG of the product; it provides a new view of recommendation by tracking the paths from a purchaser’s history to a product with high relevance probability (Equation (

3)). For example, a purchaser’s interest in product ”iPhone 14” might be explained by the path ”purchaser

iPhone 14

4999

Huaweimate70pro”, the product ”Huaweimate70pro” is highly probable to be relevant to ”iPhone 14” and ”4999” in the purchaser’s one-hop and two-hop sets. KnoChain discovers relevant paths automatically, not manually as with other methods. We provide a visualised example in

Figure 2 to demonstrate KnoChain’s explainability.

4. Experiments

4.1. Datasets

We evaluate the proposed model on three standard common datasets—MovieLens-1M (

http://grouplens.org/datasets/movielens/1m/ accessed on 23 December 2025), Book-Crossing (

http://ocelma.net/MusicRecommendationDataset/lastfm-1K.html accessed on 23 December 2025), and Last.fm (

https://gitcode.com/open-source-toolkit/7a493 accessed on 23 December 2025)-to demonstrate its effectiveness. Although the dataset does not come directly from the supply chain, the model can directly adapt to the supply chain scenarios. The essence of the cold-start problem in the supply chain is that the newly launched products and new purchasers lack historical interactive data and cannot be effectively recommended. This is consistent with the cold-start problem faced by film, books, and music in recommending new films and new users. If a specific supply chain dataset, such as a manufacturing procurement database, is used in the future, the model can directly adapt to the knowledge graph structure of ”purchaser-product attributes-product”, achieving targeted cold-start mitigation. The product attributes can be manufacturer, product category, material, and so on. Taking the datasets used in this paper as examples, the correspondence of key concepts is intuitively displayed in

Table 2. The basic statistics for the three datasets are shown in

Table 3. Basic statistics for the three datasets are shown in

Table 3; dataset preprocessing and KG linking follow standard procedures as in KB4Rec [

40]. The primary reason we use widely adopted public benchmarks (MovieLens, Book-Crossing, Last.fm) is to evaluate our method in a fair, comparable, and reproducible setting against state-of-the-art baselines. We acknowledge that the abstract concept mapping in

Table 2 does not fully capture the complexity of real-world supply chains, such as supplier reliability, multi-level BOM dependencies, variable lead times, capacity constraints, and disruption events. To make this limitation explicit, we note that the experiments reported here focus on the general cold-start and sparsity aspects of recommendation models rather than a comprehensive validation of every operational facet of supply chain systems. As future work, we plan to collect real procurement and supplier data through industry collaboration to construct domain-specific supply chain datasets and knowledge graphs, and to develop a reproducible simulation framework for controlled ablation and robustness studies. We will then re-evaluate KnoChain and the baselines on these real or simulated supply chain datasets, report both standard recommendation metrics and supply chain-specific KPIs (e.g., on-time fill rate, stockout frequency, average fulfilment time, and successful supplier-switch rate), and include ablation analyses isolating the effects of supplier reliability, lead times, and BOM edges.

4.2. Baselines

RippleNet [

12] (KG propagation): RippleNet propagates user interests along KG paths to expand purchaser representations. We include it because it exemplifies outward multi-hop interest propagation, a key component of KnoChain and is a widely used KG-based state-of-the-art method for cold-start/interest expansion. KGCN [

13] (KG neighbourhood aggregation): KGCN aggregates multi-hop neighbour information to build entity embeddings. It represents the inward aggregation family (product-centric neighbourhood aggregation), complementary to RippleNet user-centric propagation. Including KGCN lets us compare how different directions of KG information flow affect performance. DKN [

39] (KG + text attention): DKN integrates KG information with text (word/entity embeddings + attention). We include DKN to represent methods that fuse KG structural information with auxiliary textual features; though less suitable for short item names in our datasets, it is an important representative of KG + content approaches. CKE [

6] (KG for embedding augmentation): CKE uses KG structural information to augment item embeddings (and benefits from auxiliary modalities). It represents approaches that treat KG as external descriptor information appended to standard embedding models. PER [

43] (meta-path features): PER constructs meta-path-based features from the KG. Meta-path methods are common in heterogeneous information networks and are useful baselines for capturing higher-order semantic connections. LibFM [

44], Wide and Deep [

45] (feature + factorisation/DNN hybrids): These non-KG baselines combine explicit feature engineering with factorisation or DNNs and are a strong general purpose recommender. They serve to show that KG-aware approaches outperform both classic factorisation and DNN hybrid models when KG structure is exploited.

4.3. Experiment Setup

We convert the explicit feedback of these three datasets into implicit feedback. For Movielens-1M, if the purchaser’s rating of the product is greater than 4, the product is marked as 1. For book-crossing and last.Fm, the product’s label is set to 1. To ensure the equality of positive and negative samples, a negative sampling strategy is adopted to extract some products that purchasers do not interact with and mark them as 0. Microsoft Satori (

https://www.dbpedia.org/resources/ accessed on 23 December 2025) is employed to build the KG for each dataset.

The hyperparameters are set as follows: d denotes the dimension of embedding for purchasers, products, and the KG. H means the hop number. It is also the number of layers that purchasers’ interests propagate on KG. N means the depth of the receptive field. That is, the order of the aggregate entity neighbours. M denotes the size of the interest sets in each order. K represents the size of sampled neighbours of the entity. indicates the learning rate. represents the weight of KGE. represents the weight of the regulariser.

Data splits and metrics: For all datasets, we use the same 6:2:2 train:validation:test split and convert explicit feedback to implicit labels. Evaluation metrics are Accuracy (ACC) and AUC, and negative sampling is applied to balance positives/negatives uniformly across methods.

Tuning methodology: For KnoChain and all baselines, we tuned hyperparameters on the validation set using grid search (or guided grid search) within standard ranges. The same tuning protocol and ranges were applied to each method to ensure fairness. We used early stopping based on validation AUC to avoid overfitting.

Reported final settings:

Table 4 lists the final hyperparameter settings used for each dataset (embedding dimension

d, hops

H, interest set size

M, sampled neighbour size

K, receptive depth

N, learning rate

, KGE weight

, regulariser weight

). These are the values selected via validation and used for test reporting.

Typical search ranges: e.g., , , , , , , .

4.4. Analysis of Experimental Results

The experimental results are presented in

Table 5 and

Figure 3. DKN is more suitable for news recommendations with long titles, while the names of movies, books, and music are short and vague, so the datasets are not suitable for this model. For PER, it is difficult to design the optimal meta-path in reality. CKE had only usable structural knowledge. It performs even better with auxiliary information such as images and text. LibFM and Wide&Deep showed satisfactory performance, indicating that they were able to apply the knowledge information contained in KG to their model algorithms. RippleNet and KGCN both use the multi-hop neighbourhood structure information of entities in the KG. RippleNet focuses on using this information to spread purchasers’ interest and expand the vector representation of purchasers, ignoring the feature extraction of products. KGCN focuses on using this information to aggregate products’ neighbourhood information and expand the vector representation of products, ignoring the feature extraction of purchasers. KnoChain uses the high-order semantic and structural information of the KG to mine purchasers’ interests and extracts products’ features, thus enriching the vector representations of purchasers and products at the same time.

In general, KnoChain performs best among all methods on the three datasets for the CTR (CTR: Click-Through Rate; the prediction task is binary click/no-click, and the model outputs click probabilities) task. KnoChain achieves average ACC (ACC: Accuracy, computed as the proportion of correct predictions) gains of 8.76%, 6.57%, and 8.87% in movie, book, and music recommendation, respectively. And KnoChain achieves average AUC (AUC: Area Under the ROC Curve, a measure of the model’s ranking/discrimination ability between positive and negative samples) gains of 9.46%, 5.91%, and 8.91% in movie, book, and music recommendation, respectively. It illustrates the effectiveness of KnoChain in recommendations.

By observing the performance of the three datasets in the CTR prediction experiment, we can see that the MovieLens-1M performs best, followed by the Last.FM, and finally the Book-Crossing. This may be related to the sparsity of the dataset since the Book-Crossing dataset is the sparsest and therefore performs the worst in the experiment.

4.5. Parameter Analysis

This section analyses the performance of the model when the key superparameters take different values on three datasets.

4.5.1. Size of Sampled Neighbour (K)

We can observe from

Table 6 that if

K is too small, the neighbourhood information is not fully utilised,

K is too large, and it is easy to be misled by the noise. According to the results of the experiment,

K between 4 and 16 is the best.

4.5.2. Depth of Receptive Field (N)

The value of

N was 1∼4. The results are shown in

Table 7. Because a large

N brings considerable noise to the model, we can see that the model will collapse seriously when

N = 3. It is also easy to understand, because when inferring similarity between products, if the distance between them is too far, obviously there is not much correlation. According to the experimental results, the model works best when

N is 1 or 2.

4.5.3. Dimension of Embedding (d)

Table 8 shows the best results in different dimensions for different datasets. For movie datasets, the best results occur when the embedding dimension is large. For book datasets, the best results occur when the embedding dimension is small. For music datasets, performance improves initially as

d increases but degrades again if

d becomes too large. The embedding dimension size may be related to the sparsity of data. To explain the different optimal embedding dimensions reported in

Table 8, we link the choices of

d to dataset characteristic. MovieLens-1M is relatively dense with richer KG neighbourhood information, so a larger embedding dimension (

d = 16) provides the extra capacity needed to capture diverse user/item semantics and improves results. Book-Crossing is much sparser, so large dimensions are more prone to overfitting noisy or insufficient signals and a smaller

d (

d = 4) is more robust. Last.FM is intermediate and benefits from moderate d before performance degrades due to overfitting. Overall, these results suggest selecting

d according to dataset sparsity and KG richness: increase

d when interactions and KG degree are high, reduce

d for sparse datasets.

4.5.4. Size of the High-Order Interest Set in Each Hop (M)

As shown in

Table 9, KnoChain’s performance initially improves with a larger high-order interest set, extracting more information from the KG. However, an excessively large interest set can introduce noise, degrading performance. A size of 16 to 64 is suitable. Increasing M initially improves performance by incorporating more KG context, but beyond 16–64 it introduces noise and degrades accuracy—use moderate interest-set sizes.

4.5.5. Number of Maximum Hops (H)

As we can see from

Table 10, the performance is best when the value of

H is 1 or 2. The reason is that if

H is too small, the entity cannot adequately obtain its neighbourhood information. However, if

H is too large, it will bring more noise, which will lead to poor performance of the model. Short propagation (H = 1/2) is best. Deeper hops quickly dilute the useful signal with noise, so limit hop depth in practical deployments.

Table 4 gives the best value of the hyperparameters.

4.5.6. Debugging the Aggregator

Aggregation is a key process of the model because the feature representation of a product is achieved by aggregating itself with its neighbour information. Due to the different aggregation methods, different results should be presented in CTR prediction. Therefore, in the experiment, we also test the effect of aggregators on the prediction. We tested the three aggregators in the experiment: sum aggregator, concat aggregator, and neighbour aggregator. We can see from

Figure 4 that the sum aggregator performed best, followed by the concat aggregator, and the neighbour aggregator performed worst. The sum aggregator consistently yields the best CTR performance—simple additive fusion balances signal integration and noise control better than concatenation or raw neighbour outputs.

In general, K and M control how much local and multi-hop KG information is exposed to the model: larger can be beneficial when the KG and interaction graph are dense (higher average degree and higher interaction density). There is more useful neighbourhood signal to aggregate, but they introduce noise and overfitting risk on sparse datasets, so we recommend modest values (our experiments indicate 16–64 and K in the low tens as sensible starting points) and scaling them with average node degree. H and N determine how far user interests and product receptive fields propagate: denser data and well-connected KGs can tolerate to capture useful multi-hop relations, whereas very sparse datasets perform best with and to avoid amplifying weak/noisy paths.

5. Discussion

5.1. Model Explainability

Although KnoChain is a deep model, it yields several readily interpretable intermediate signals that support explanations. The relevance probabilities and purchaser-relation scores quantify how much each knowledge-graph triple and relation contributes to the prediction, while the multi-hop responses record how influence propagates from a purchaser’s historical items to the candidate product across hops. These outputs can be used to produce human-readable explanations by ranking top-contributing triples or entities, visualising dominant propagation paths (seed product to intermediate entities to recommended product), and plotting per-hop attention heatmaps. We include an example case in

Figure 2 that lists the 3-order hop triples and the main propagation path for a sample recommendation. The detailed explanation can be found in

Section 3.3. We emphasise that attention weights are proxies for importance rather than causal proofs, and we validate explanations via abundant experiments to increase explanation fidelity.

5.2. Discussion About Key Components That Drive Improvements

This subsection summarises the model components that appear to contribute most to the observed performance gains.

Bidirectional expansion (outward propagation and inward aggregation). The bidirectional mechanism combines outward propagation from purchaser seed nodes, which activates multi-hop entities related to a purchaser’s history, with inward aggregation for products, which refines product representations by incorporating purchaser-weighted multi-hop neighbours. These complementary flows extend semantic coverage beyond direct interactions, mitigate sparsity and cold-start effects, and improve purchaser–product matching.

Attention/purchaser-aware weighting. Attention weights () used to score elements in the interest set together with neighbour importance weights () allow the model to emphasise KG facts that are most relevant for a specific purchaser–product pair. Compared with uniform aggregation, these purchaser-aware weights provide stronger personalised signals and are a key driver of accuracy improvements.

Aggregator choice. Experimental results indicate that a simple sum (additive) aggregator often outperforms concatenation or raw neighbour-output aggregators. The sum aggregator appears to preserve complementary signals while avoiding over-parameterisation and noise amplification, yielding more robust practice performance.

Hyperparameter choices as inductive biases. Several hyperparameters function as important inductive biases and materially affect performance:

Interest-set size M and neighbour sample size K: moderate values (e.g., –64) capture useful higher-order context while limiting noise; overly large values introduce many irrelevant signals.

Hop depth H: shallow propagation (–2) is generally most robust; deeper hops tend to dilute effective signals and reduce accuracy.

Embedding dimension d: the optimal d depends on dataset density—denser datasets tolerate larger d, while sparser datasets benefit from smaller d to avoid overfitting.

5.3. Managerial Implications

Here are the specific steps of an example applied in a practical supply chain scenario. Practical steps: (1) gather interaction logs, product catalogs, and supplier metadata and normalise IDs; (2) build a domain KG linking purchasers, parts, suppliers, categories, and logistics nodes; (3) run offline validation and a focused pilot (e.g., alternative-part or supplier discovery) with human-in-the-loop review; (4) deploy via API or procurement UI and monitor KPIs. Expected benefits include faster supplier discovery, reduced stockout risk via automated substitutes, improved inventory turns and lead-time predictability. Track time-to-source, stockout incidents, substitute acceptance rate, and lead-time variance; validate via A/B tests and perturbation checks.

In supply chain management (SCM), RS support operational matching (e.g., matching purchasers to suppliers or SKUs) and rapid decision-making under disruption. Cold start is particularly acute in SCM because new SKUs, new suppliers, or newly formed buyer–supplier relationships frequently appear (for example, when product designs change, a new supplier is onboarded, or a supplier is disqualified), and historical interaction data for these entities are typically sparse. This sparsity is compounded by (a) long product lifecycles with infrequent repeat purchases of specialised items; (b) fragmentation of procurement across multiple buyers and plants; and (c) the high business cost of mistaken recommendations (quality, compliance, lead time). Prior work has shown that recommender models can enable agility and risk mitigation in SCM. KG-based is a promising side-information source to enrich sparse entity representations and reduce cold-start risk. We make this concrete below by mapping common KG constructs to supply chain concepts and by presenting three representative workflows where KnoChain can be applied.

5.4. Design Rationale for the Bidirectional Architecture

Considering the asymmetry between purchasers and products in recommendation, we combine outward propagation (purchaser → KG) with inward aggregation (KG → product). Outward propagation treats a purchaser’s interacted products as seeds and activates multi-hop entities to recover personalised, traceable high-order interests. Inward aggregation treats each product as a receptive field and aggregates neighbourhood entities and relations to enrich product semantics. Compared to alternatives, this hybrid balances expressiveness, interpretability, and noise control: (1) pure propagation (e.g., RippleNet) enriches purchasers but under-utilises product neighbourhood structure; (2) pure aggregation (e.g., KGCN) enriches products but does not explicitly reconstruct purchaser intent; (3) fully symmetric message-passing GNNs can introduce irrelevant multi-hop signals, increase computation, and reduce interpretability. We mitigate noise and complexity by limiting hop depth, sampling fixed-size neighbour/interest sets, and using relation-aware attention weights during aggregation. Empirically, the dual-path design yields consistent gains over single-path baselines, as shown in

Table 5.

5.5. Prospects for Practical Application in Supply Chain Workflows

Practical application in supply chain workflows. KnoChain’s dual-path KG usage maps directly to several SCM tasks. Below, we explain three representative workflows and how the model supports them:

Supplier-to-procurement-category matching. Goal: recommend candidate suppliers or source SKUs for a given procurement request, for example, the procurement of surface-mount capacitors. Mapping: purchasers such as procurement managers and plant buyers are modelled as purchaser nodes; SKUs, suppliers, manufacturers, and product categories are modelled as product and entity nodes; relations include supplied-by, belongs-to-category, and manufactured-by. Outward propagation expands a purchaser’s seed nodes—which consist of past-purchased SKUs and preferred suppliers—into multi-hop supplier and category signals; inward aggregation enriches SKU embeddings with supplier, manufacturer, and certification attributes. Result: improved matching for new SKUs or newly assessed suppliers, because the knowledge graph supplies attribute and relational context when little or no transaction data exist.

Identifying substitute products (material substitution). Goal: recommend substitute parts or alternative materials automatically when a primary material becomes unavailable because of disruption or shortage. Mapping: relations including is substitute of, equivalent spec, and alternative material link SKUs, technical specifications, and manufacturers in the knowledge graph. KnoChain’s inward aggregation gathers multi-hop attributes such as spec similarities, shared suppliers, and certification overlap, and uses the aggregated context to rank substitutes and assign confidence scores despite sparse purchase histories.

Recommending logistics service providers. Goal: recommend carriers or third-party logistics providers for a shipment, for example, selecting a cold-chain carrier or choosing express versus standard transit, constrained by contractual terms, transit geography, and commodity characteristics. Mapping: the graph encodes shipments, carriers, transport modes, regions, and contract terms, with relations including handled by, serves region, and contract with. Outward propagation leverages a purchaser’s shipment history to surface carriers, routing options, and regional attributes; inward aggregation incorporates contract metadata, performance indicators, and capacity constraints into carrier representations. This enables recommending carriers for novel routes or low-usage carriers by supplying contextual signals when transactions are sparse.

6. Conclusions and Future Work

In this paper, we propose a bidirectional feature expansion framework. It employs outward propagation to refine the purchaser representation from their interaction history and uses inward aggregation to refine the product representation from their multi-hop neighbours. Therefore, the features of both purchasers and products are extracted in the proposed model simultaneously. This model alleviates the sparsity and cold-start problems in RS and achieves personalised recommendations in supply chain management. Experiments on three datasets demonstrate the competitiveness of our model over several advanced approaches.

Implications. Our proposed knowledge-graph-augmented recommender for purchaser–SKU matching contributes to sustainability by improving demand forecasting and procurement decisions, thereby reducing overstock, waste, and unnecessary transportation; by enabling more informed supplier/SKU substitution that favors lower-impact options; and by increasing supply chain resilience through better use of multi-source contextual knowledge (e.g., product attributes, manufacturer relationships). These effects align with prior findings that data-driven and AI methods can improve supply chain sustainability and resilience when integrated with domain knowledge [

46,

47]. The model’s purchaser-aware attention and explainable KG paths also support trust and acceptability among procurement purchasers, which is critical for adoption of sustainability-oriented recommendations [

48].

Limitations. The primary limitation of this study is the lack of dedicated datasets from real-world supply chain settings. We evaluated our approach on public recommendation datasets that are useful for assessing cold-start capabilities but do not fully capture supply chain contract semantics, operational constraints, or characteristic graph structures. Importantly, the proposed method can be directly extended to practical supply chain scenarios; nonetheless, its performance in operational environments depends on access to domain data, the construction of domain knowledge graphs, and task-specific calibration. Accordingly, we have acknowledged this limitation in the conclusion and recommend that future work prioritises the collection of industry datasets, the development of domain knowledge graphs, and validation on real business cases. The work focuses on leveraging side information from a knowledge graph to support automatic recommendations for newly launched products in the supply chain. Therefore, the second limitation is the challenge of real-world complexity, such as supplier reliability, component interdependence, and delivery cycles. When considering these factors, models trained on movie or book datasets exhibit significant limitations in actual supply chain scenarios.

Future work. We will address these gaps by collecting proprietary supply chain interaction data and domain knowledge graphs, extending KnoChain with temporal and dynamic KG techniques, investigating scalable training and inference strategies, improving robustness to noisy graphs, enhancing explanation fidelity and causal evaluation, and validating the approach through online experiments and business level metrics. Practical deployment faces several nontrivial challenges. First, constructing and continuously maintaining a high-quality domain KG—including entity alignment, relation extraction, data cleaning, and versioning—requires substantial engineering effort and domain expertise. Second, supply chain data are typically fragmented across heterogeneous systems, making identifier alignment and data integration a time-consuming prerequisite. Third, supplier and contract records can be sensitive, so deployments must adopt privacy and compliance safeguards, such as field masking, access control, and federated or other privacy-preserving training. Finally, industrial scale graphs with millions of entities and billions of edges impose memory, sampling, and latency constraints that necessitate scalable solutions, such as neighbour sampling, graph partitioning, Cluster GCN or GraphSAINT style mini-batching, and distributed inference. We recommend staged pilots, automated incremental KG pipelines, scalable GNN engineering, and clear monitoring with KPI thresholds for time to source, stockout incidents, and substitution acceptance.