Numerical Investigation of Evolution of Reservoir Characteristics and Geochemical Reactions of Compressed Air Energy Storage in Aquifers

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Model Setup

2.1. Background

2.2. Numerical Method

2.3. Reservoir Batch Model

- The overlying and underlying strata in the study area were assumed to be impermeable, while large-volume grids were employed for the lateral boundaries to simulate open boundaries.

- The TOUGHREACT simulator was primarily used to investigate Darcy-scale or pore-scale fluid migration and chemical reactions, while neglecting non-Darcy flow effects and microbial processes involved in CAESA.

- It was difficult to characterize the reservoir in detail due to the physical parameters of the St. Peter Sandstone formation in the Pittsfield field. Inter-stratal physical parameters (e.g., permeability and porosity) were derived from site-specific data. However, within a single stratum, we assumed it to be a homogeneous anisotropic stratum, and the mineral parameters within the stratum were assumed to be consistent.

- The oxidation reaction of pyrite and its products were hypothesized to be complete reactions, and possible incomplete reactions and their products were ignored.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Evolution of Aquifer Reservoir Characteristics

3.1.1. Effects of Different Air Injection Rates

3.1.2. Effects of Different Air Injection Temperatures

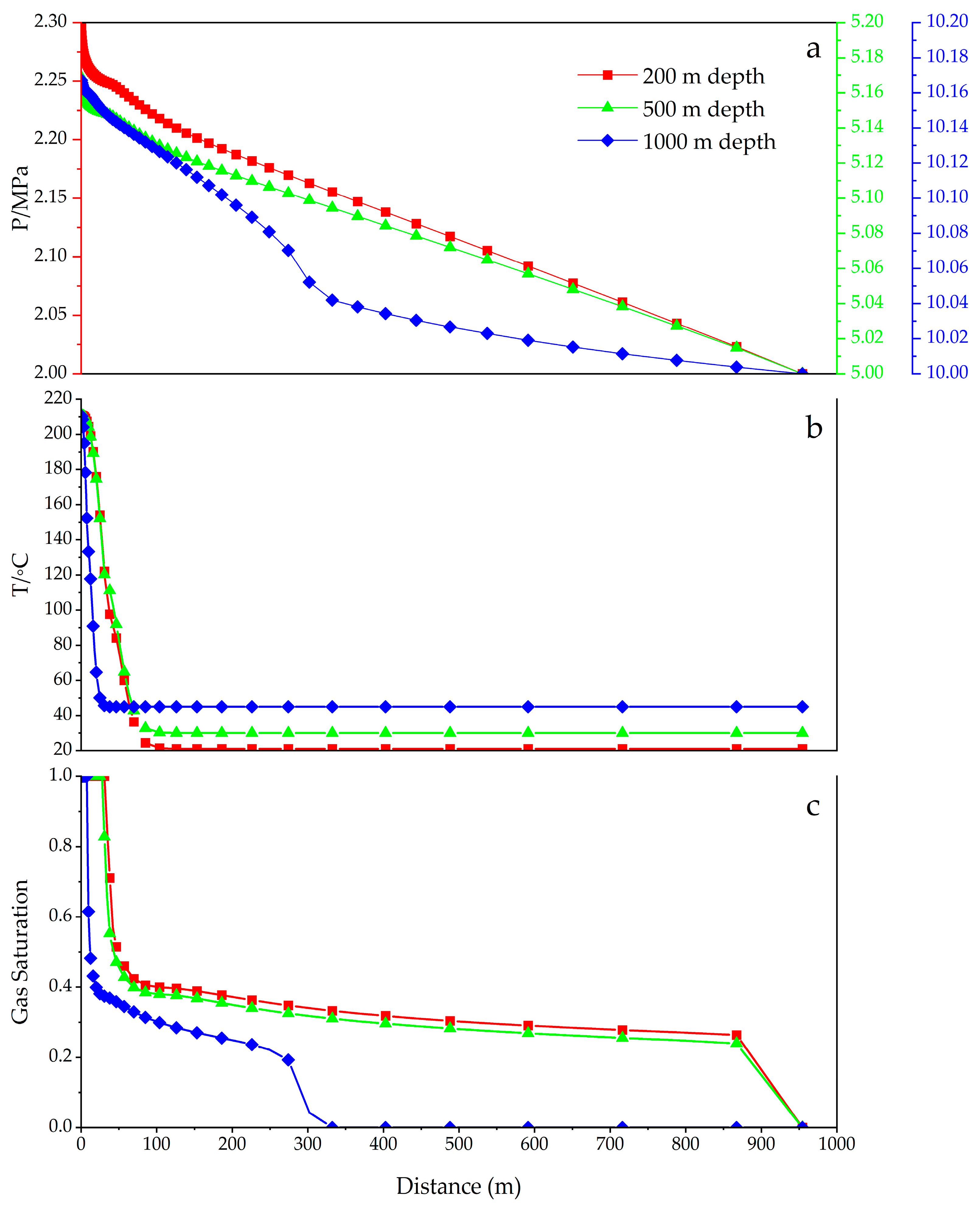

3.1.3. Effects of Initial Temperature and Pressure at Different Formation Depths

3.1.4. Influence of Different CAESA Cycles

3.2. Evolution of Geochemical Reactions

3.2.1. Dissolution of Oxygen in Injected Air

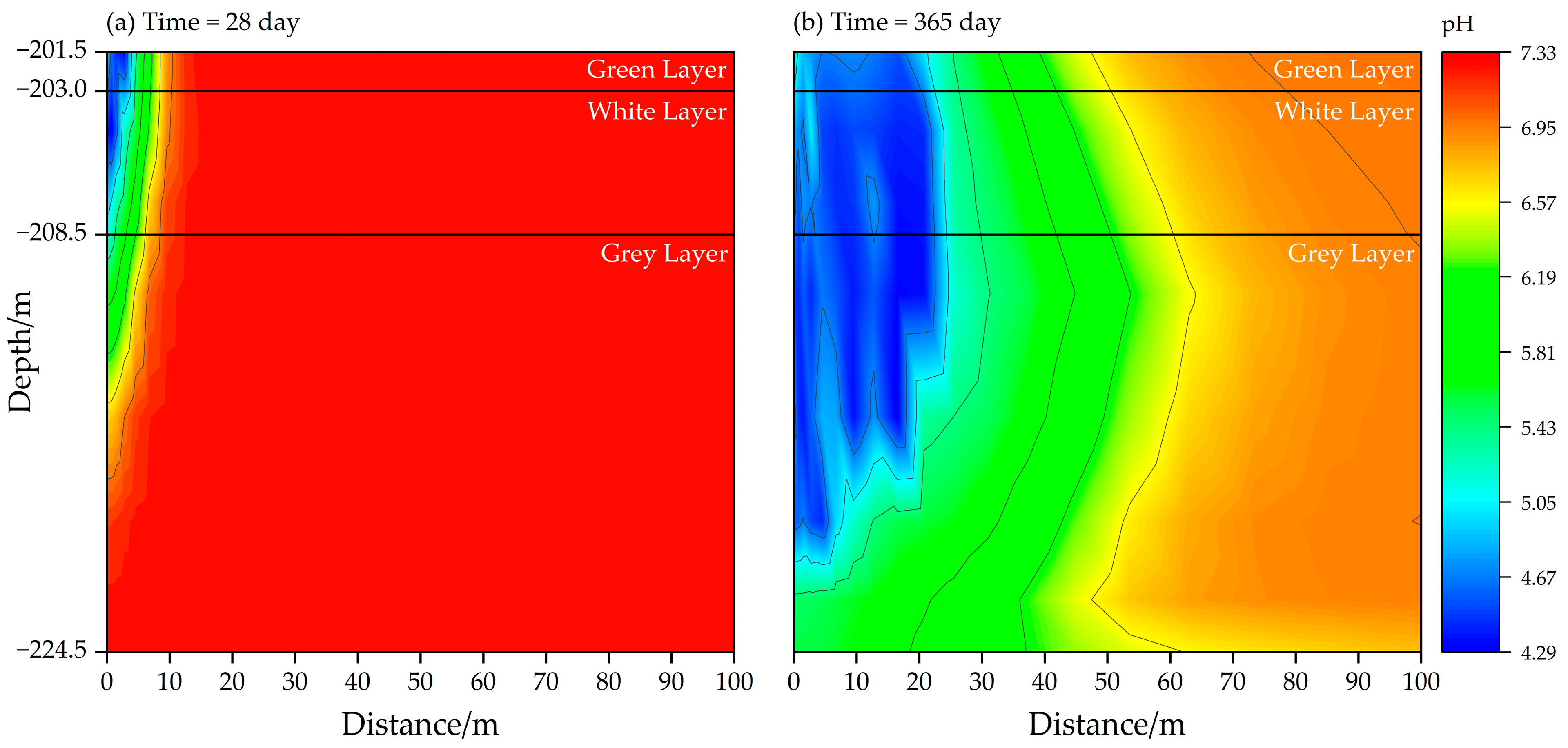

3.2.2. pH of Solution

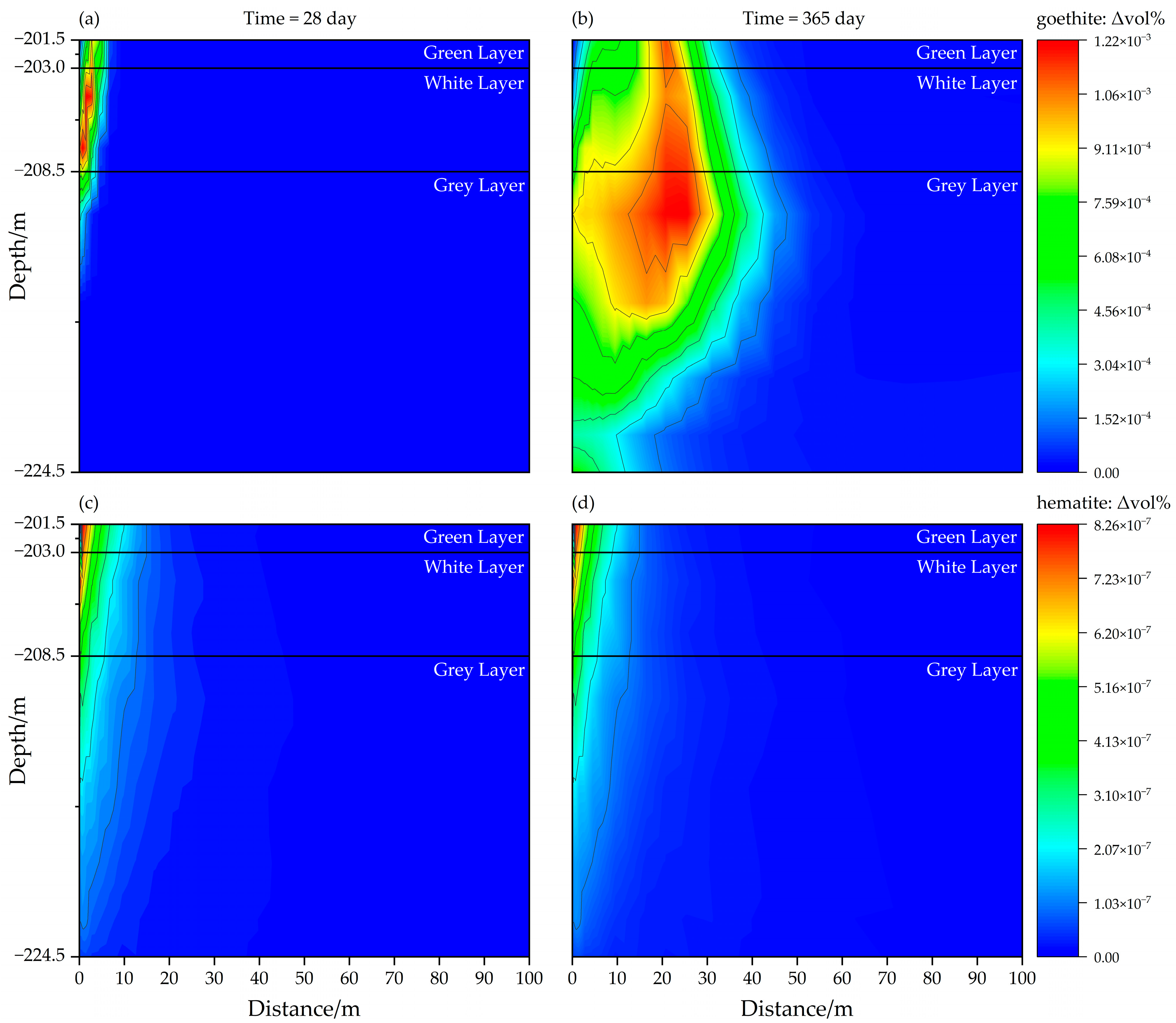

3.2.3. Mineral Dissolution or Precipitation

3.2.4. Oxygen Depletion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ameel, B.; T’Joen, C.; De Kerpel, K.; De Jaeger, P.; Huisseune, H.; Van Belleghem, M.; De Paepe, M. Thermodynamic analysis of energy storage with a liquid air Rankine cycle. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2013, 52, 130–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Zhang, X.; Liu, J.; Tan, C. Compressed Air Energy Storage. In Energy Storage-Technologies and Applications; Zobaa, A.F., Ed.; INTECH d.o.o.: Zagreb, Croatia, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razmi, A.R.; Hanifi, A.R.; Shahbakhti, M. Design, thermodynamic, and economic analyses of a green hydrogen storage concept based on solid oxide electrolyzer/fuel cells and heliostat solar field. Renew. Energy 2023, 215, 118996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komba, N.A.; Haisong, C.; Liwoko, B.B.; Mwakipunda, G.C. A comprehensive review on compressed air energy storage in geological formation: Experiments, simulations, and field applications. J. Energy Storage 2025, 114, 115795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, T.; Zhang, B.; Chen, W.; Li, J.; Yang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Xue, X. Study on the applicability of a horizontal well in compressed air energy storage in aquifer. Energy 2025, 329, 136778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghahosseini, A.; Breyer, C. Assessment of geological resource potential for compressed air energy storage in global electricity supply. Energy Convers. Manag. 2018, 169, 161–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Czapla, J.P.; Clennell, M.B.; Lu, C. Understanding the influence of aquifer properties on the performance of compressed air energy storage in aquifers: A numerical simulation study. J. Energy Storage 2024, 99, 113202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Q.; Wang, Q.; Tan, X.; Fang, G.; Meng, J. A review of compressed-air energy storage. J. Renew. Sustain. Energy 2019, 11, 042702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oldenburg, C.M.; Pan, L. Porous Media Compressed-Air Energy Storage (PM-CAES): Theory and Simulation of the Coupled Wellbore-Reservoir System. Transp. Porous Media 2013, 97, 201–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Song, R.; Liu, J.; Yang, C. Evaluation on H2, N2, He & CH4 diffusivity in rock and leakage rate by diffusion in underground gas storage. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 100, 234–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budt, M.; Wolf, D.; Span, R.; Yan, J. A review on compressed air energy storage: Basic principles, past milestones and recent developments. Appl. Energy 2016, 170, 250–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, C.; Zhang, K.; Li, C. Subsurface system design and feasibility analysis of compressed air energy storage in aquifers. Tongji Daxue Xuebao/J. Tongji Univ. 2016, 44, 1107–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Li, Y.; Liu, Y.; Cao, X. Compressed air energy storage in aquifers: Basic principles, considerable factors, and improvement approaches. Rev. Chem. Eng. 2019, 37, 561–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Yang, C.; Liu, J.; Hou, Z.; Xie, Y.; Shi, X. An overview of underground energy storage in porous media and development in China. Gas Sci. Eng. 2023, 117, 205079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, C.; Li, C.; Zhang, K.; Cai, Z.; Ma, T.; Maggi, F.; Gan, Y.; El-Zein, A.; Pan, Z.; Shen, L. The promise and challenges of utility-scale compressed air energy storage in aquifers. Appl. Energy 2021, 286, 116513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, R.D.; Doherty, T.J.; Kannberg, L. Summary of Selected Compressed Air Energy Storage Studies; Department of Energy Office of Scientific and Technical Information: Springfield, IL, USA, 1985.

- Kushnir, R.; Ullmann, A.; Dayan, A. Compressed Air Flow within Aquifer Reservoirs of CAES Plants. Transp. Porous Media 2010, 81, 219–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, C.; Zhang, K.; Pan, L.; Cai, Z.; Li, C.; Li, Y. Numerical investigation of a joint approach to thermal energy storage and compressed air energy storage in aquifers. Appl. Energy 2017, 203, 948–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Liu, Y.; Hu, B.; Li, Y.; Dong, J. Numerical investigation of a novel approach to coupling compressed air energy storage in aquifers with geothermal energy. Appl. Energy 2020, 279, 115781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Li, Y.; Liu, Y. Numerical study on the impacts of layered heterogeneity on the underground process in compressed air energy storage in aquifers. J. Energy Storage 2022, 46, 103837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wang, H.; Wang, J.; Hu, L.; Wu, X.; Yang, Y.; Gai, P.; Liu, Y.; Li, Y. The underground performance analysis of compressed air energy storage in aquifers through field testing. Appl. Energy 2024, 366, 123329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Guo, C.; Wang, J.; Chen, R.; Liu, Y. Coupled wellbore-aquifer numerical analysis of underground performance of compressed air energy storage in heterogeneous aquifers. J. Energy Storage 2025, 114, 115794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandra, A.P.; Gerson, A.R. The mechanisms of pyrite oxidation and leaching: A fundamental perspective. Surf. Sci. Rep. 2010, 65, 293–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dos Santos, E.C.; de Mendonça Silva, J.C.; Duarte, H.A. Pyrite Oxidation Mechanism by Oxygen in Aqueous Medium. J. Phys. Chem. C 2016, 120, 2760–2768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, M.S.; Larsen, F.; Postma, D. Pyrite Oxidation in Unsaturated Aquifer Sediments. Reaction Stoichiometry and Rate of Oxidation. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2001, 35, 4074–4079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rimstidt, J.D.; Vaughan, D.J. Pyrite oxidation: A state-of-the-art assessment of the reaction mechanism. Geochim. Et Cosmochim. Acta 2003, 67, 873–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardejani, F.D.; Singh, R.N. Two-Dimensional simulation of pyrite oxidation and pollutant transport in backfilled open cut coal mines. In Proceedings of the Symposium: Mine Water 2004-Process, Policy and Progress, Newcastle upon Tyne, UK, 15 September 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Qiu, G.; Luo, Y.; Chen, C.; Lv, Q.; Tan, W.; Liu, F.; Liu, C. Influence factors for the oxidation of pyrite by oxygen and birnessite in aqueous systems. J. Environ. Sci. 2016, 45, 164–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Y.; Short, M.D.; Li, J.; Schumann, R.C.; Smart, R.S.C.; Gerson, A.R.; Qian, G. Control of Acid Generation from Pyrite Oxidation in a Highly Reactive Natural Waste: A Laboratory Case Study. Minerals 2017, 7, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, T.; White, S.P.; Pruess, K.; Brimhall, G.H. Modeling of Pyrite Oxidation in Saturated and Unsaturated Subsurface Flow System. Transp. Porous Media 2000, 39, 25–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sin, I.; De Windt, L.; Banc, C.; Goblet, P.; Dequidt, D. Assessment of the oxygen reactivity in a gas storage facility by multiphase reactive transport modeling of field data for air injection into a sandstone reservoir in the Paris Basin, France [Article]. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 869, 161657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whims, M.J. Compressed-Air Energy Storage: Pittsfield Aquifer Field Test; Test Data: Engineering Analysis and Evaluation; Final Report; Electric Power Research Institute: Detroit, MI, USA, 1990; Available online: https://books.google.com.tw/books?id=aHYHPwAACAAJ (accessed on 8 April 2019).

- Ethington, E.F.; Olhoeft, F.R.; King, T.V.V. Oxygen Depletion Studies in the Electrical Power Research Institute, Compressed Air Energy Storage Facility; Electrical Power Research Institute: Denver, CO, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Aghababaei, F.; Sedaee, B. Underground compressed air energy storage (CAES) in naturally fractured depleted oil reservoir: Influence of fracture. Geoenergy Sci. Eng. 2025, 244, 213496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Bauer, S. Induced geochemical reactions by compressed air energy storage in a porous formation in the North German Basin. Appl. Geochem. 2019, 102, 171–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bui, H.; Herzog, R.; Jacewicz, D.; Lange, G.; Scarpace, E.; Thomas, H. Compressed-Air Energy Storage: Pittsfield Aquifer Field Test; Electrical Power Research Institute: Detroit, MI, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, T.; Sonnenthal, E.; Spycher, N.; Zheng, L. TOUGHREACT V3.32 Reference Manual: A Parallel Simulation Program for Non-Isothermal Multiphase Geochemical Reactive Transport; Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2017.

- Palandri, J.; Kharaka, Y. A Compilation of Rate Parameters of Water-Mineral Interaction Kinetics for Application to Geochemical Modeling; National Energy Technology Laboratory—United States Department of Energy: Menlo Park, CA, USA, 2004.

- Yang, L.C.; Cai, Z.S.; Li, C.; He, Q.C.; Ma, Y.; Guo, C.B. Numerical investigation of cycle performance in compressed air energy storage in aquifers. Appl. Energy 2020, 269, 115044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, D.; Chu, Z.; Chen, W.; Feng, P.; Zhang, J. Comparison of the characteristics of compressed air energy storage in dome-shaped and horizontal aquifers based on the Pittsfield aquifer field test. Appl. Energy 2023, 348, 121465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, T.; White, S.P.; Prues, K. Pyrite Oxidation in Saturated and Unsaturated Porous Media Flow: A Comparison of Alternative Mathematical Modeling Approaches; Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2008.

- Liao, X.; Chigira, M.; Matsushi, Y.; Wu, X. Investigation of water–rock interactions in Cambrian black shale via a flow-through experiment. Appl. Geochem. 2014, 51, 65–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verron, H.; Sterpenich, J.; Bonnet, J.; Bourdelle, F.; Mosser-Ruck, R.; Lorgeoux, C.; Randi, A.; Michau, N. Experimental Study of Pyrite Oxidation at 100 °C: Implications for Deep Geological Radwaste Repository in Claystone. Minerals 2019, 9, 427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, D.; Regenspurg, S. Geochemical Characterization of the Lower Jurassic Aquifer in Berlin (Germany) for Aquifer Thermal Energy Storage Applications. Energy Procedia 2014, 59, 285–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigham, J.M.; Schwertmann, U.; Traina, S.J.; Winland, R.L.; Wolf, M. Schwertmannite and the chemical modeling of iron in acid sulfate waters. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 1996, 60, 2111–2121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Component | Equation | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Mass/Heat Term | Flux Term | Source and Sink Term | |

| Water | |||

| Air | |||

| Heat | |||

| Chemical component j | |||

| Mineral | Kinetic Rate Parameters | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neutral Mechanism | Acid Mechanism | Base Mechanism | |||||||

| k25 | Ea | k25 | Ea | n (H+) | k25 | Ea | n (H+) | ||

| Primary minerals | Calcite | Equilibrium mineral | |||||||

| Anhydrite | 6.45 × 10−4 | 14.3 | |||||||

| Quartz | 1.02 × 10−14 | 87.7 | |||||||

| Illite | 1.66 × 10−13 | 35.0 | 1.05 × 10−11 | 23.6 | 0.34 | 3.02 × 10−17 | 58.9 | −0.40 | |

| K-feldspar | 3.89 × 10−13 | 38.0 | 8.71 × 10−11 | 51.7 | 0.50 | 6.31 × 10−22 | 94.1 | −0.82 | |

| Kaolinite | 6.92 × 10−14 | 22.2 | 4.90 × 10−12 | 65.9 | 0.78 | 8.91 × 10−18 | 17.9 | −0.47 | |

| Pyrite | 6.46 × 10−13 | 56.9 | |||||||

| Secondary minerals | Goethite | 1.15 × 10−8 | 86.5 | ||||||

| Hematite | 2.51 × 10−15 | 66.2 | 4.07 × 10−10 | 66.2 | 1.00 | ||||

| Dimension | Case | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| 1D | Case 1-1 Case 1-2 Case 1-3 | Effects of different air injection rates |

| Case 1-1 Case 1-4 Case 1-5 Case 1-6 | Effects of different air injection temperatures | |

| Case 1-1 Case 1-7 Case 1-8 | Effects at different formation depths, which represent aquifers of different scales | |

| 2D | Case 2-1 Case 2-2 Case 2-3 | Influence of different CAESA cycles |

| Case 2-4 Case 2-5 | Analysis of the geochemical reactions |

| Parameter | Value | Parameter | Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Grain density | 2600 kg/m3 | Heat conductivity | 2.16 W/(m·°C) |

| Grain specific heat | 920 J/(kg·°C) | Pore compressibility | 2.10 × 10−9 Pa−1 |

| Relative Permeability | van Genuchten-Mualem model | ||

| λ | 0.457 | Sls | 1.0 |

| Slr | 0.2 | Sgr | 0.1 |

| Capillary pressure | van Genuchten model | ||

| λ | 0.457 | P0 | 1.19 × 103 Pa |

| Slr | 0.15 | Sls | 1.0 |

| Pmax | 1.0 × 106 Pa | ||

| St. Peter Sandstone | Porosity | kx = ky (m2) | kz (m2) |

| Green Layer | 0.17 | 1.81 × 10−13 | 7.60 × 10−14 |

| White Layer | 0.16 | 4.03 × 10−13 | 6.62 × 10−13 |

| Gray Layer | 0.16 | 8.70 × 10−13 | 7.27 × 10−13 |

| Mineral | Formula | Volume Fraction (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Calcite | CaCO3 | 3.0 |

| Anhydrite | CaSO4 | 1.0 |

| Quartz | SiO2 | 33.0 |

| Illite | K0.6–0.85(Al, Mg)2(Si, Al)4O10(OH)2 | 28.0 |

| K-feldspar | KAlSi3O8 | 5.0 |

| Kaolinite | Al2Si2O5(OH)2 | 10.0 |

| Pyrite | FeS2 | 20.0 |

| Species | Equilibrium Concentration (mol/kg·H2O) | Species | Equilibrium Concentration (mol/kg·H2O) |

|---|---|---|---|

| H+ | 6.36 × 10−8 | SiO2(aq) | 1.21 × 10−4 |

| Ca2+ | 9.04 × 10−2 | HCO3− | 1.93 × 10−4 |

| Mg2+ | 5.93 × 10−6 | SO42− | 6.72 × 10−3 |

| K+ | 4.84 × 10−3 | AlO2− | 2.31 × 10−10 |

| Fe2+ | 4.09 × 10−6 | O2(aq) | 3.48 × 10−71 |

| pH | 7.32 | H2O | 1.0 (default value) |

| Case | Initial Condition | Boundary Condition |

|---|---|---|

| Case 1-1 | P = 2 MPa, T = 21 °C (200 m depth) | Air Injection: T = 20 °C with a fixed specified enthalpy, rate = 1 kg/s |

| Case 1-2 | P = 2 MPa, T = 21 °C | Air Injection: T = 20 °C with a fixed specified enthalpy, rate = 5 kg/s |

| Case 1-3 | P = 2 MPa, T = 21 °C | Air Injection: T = 20 °C with a fixed specified enthalpy, rate = 10 kg/s |

| Case 1-4 | P = 2 MPa, T = 21 °C | Air Injection: T = 40 °C with a fixed specified enthalpy, rate = 1 kg/s |

| Case 1-5 | P = 2 MPa, T = 21 °C | Air Injection: T = 60 °C with a fixed specified enthalpy, rate = 1 kg/s |

| Case 1-6 | P = 2 MPa, T = 21 °C | Air Injection: T = 80 °C with a fixed specified enthalpy, rate = 1 kg/s |

| Case 1-7 | P = 5 MPa, T = 30 °C (500 m depth) | Air Injection: T = 20 °C with a fixed specified enthalpy, rate = 1 kg/s |

| Case 1-8 | P = 10 MPa, T = 45 °C (1000 m depth) | Air Injection: T = 20 °C with a fixed specified enthalpy, rate = 1 kg/s |

| Case 2-1 | Atmosphere pressure: 1.01 × 105 Pa Temperature: 15 °C Hydrostatic gradient: 9.8 kPa/m Geothermal gradient: 30 °C/km | Daily cycle: 0–10 h injection, rate = 5 kg/s 16–18 h withdrawal, rate = −3 kg/s |

| Case 2-2 | Weekly cycle: Weekend: 0–10 h injection per day, rate = 5 kg/s Weekday: 16–18 h withdrawal per day, rate = −3 kg/s | |

| Case 2-3 | Monthly cycle: 0–15 days: 0–10 h injection per day, rate = 5 kg/s 16–18 days: shut-in 19–28 days: 16–18 h withdrawal per day, rate = −3 kg/s | |

| Case 2-4 | Air Injection: T = 20 °C with a fixed specified enthalpy, rate = 5 kg/s | |

| Case 2-5 | Air Injection: T = 20 °C with a fixed specified enthalpy, rate = 5 kg/s, without minerals |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xu, B.; Zhang, K. Numerical Investigation of Evolution of Reservoir Characteristics and Geochemical Reactions of Compressed Air Energy Storage in Aquifers. Sustainability 2026, 18, 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010004

Xu B, Zhang K. Numerical Investigation of Evolution of Reservoir Characteristics and Geochemical Reactions of Compressed Air Energy Storage in Aquifers. Sustainability. 2026; 18(1):4. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010004

Chicago/Turabian StyleXu, Bingbo, and Keni Zhang. 2026. "Numerical Investigation of Evolution of Reservoir Characteristics and Geochemical Reactions of Compressed Air Energy Storage in Aquifers" Sustainability 18, no. 1: 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010004

APA StyleXu, B., & Zhang, K. (2026). Numerical Investigation of Evolution of Reservoir Characteristics and Geochemical Reactions of Compressed Air Energy Storage in Aquifers. Sustainability, 18(1), 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010004