From Pixels to Plates: Exploring AI Stimuli and Digital Engagement in Reducing Food Waste Behavior in Lithuania Among Generation Z and Y

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Hypothesis

2.1. S-O-R (Stimulus–Organism–Response) Theoretical Framework

2.2. AI Stimuli and Intentions to Reduce Food Waste

2.3. Passion and Social Presence

2.4. Passion and Psychological Engagement

2.5. Usability and Social Presence

2.6. Usability and Psychological Engagement

2.7. Perceived Personalization and Social Presence

2.8. Perceived Personalization and Psychological Engagement

2.9. Perceived Interactivity and Social Presence

2.10. Perceived Interactivity and Psychological Engagement

2.11. Mediating Effect of Social Presence

2.12. Mediating Effect of Psychological Engagement

2.13. Self-Efficacy as a Moderator

2.14. Generation Y and Z as a Moderator

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Data Collection

3.2. Measurement

3.3. Data Analysis

Reliability and Validity of the Measurement Instrument

4. Results

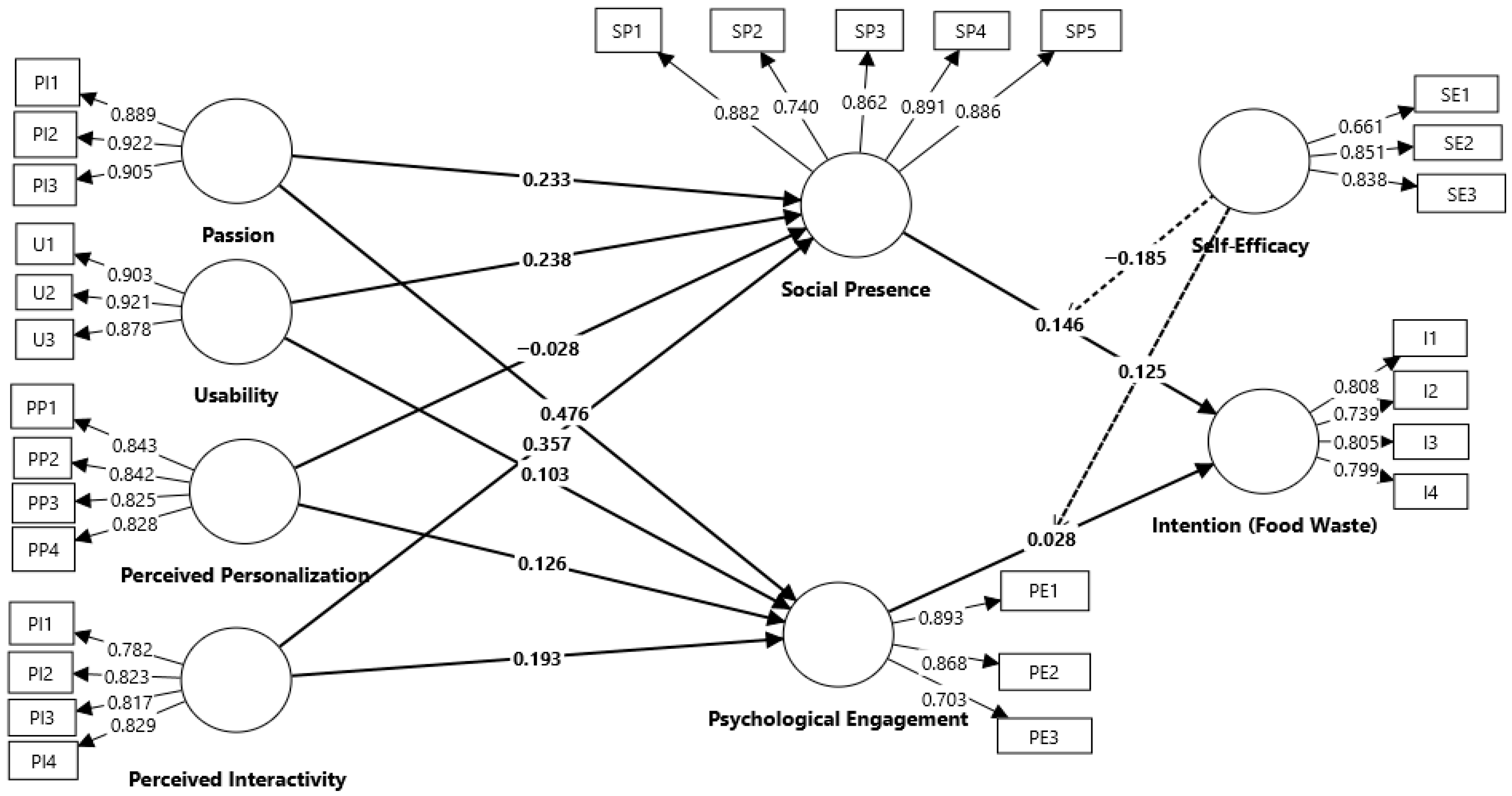

4.1. Structural Model

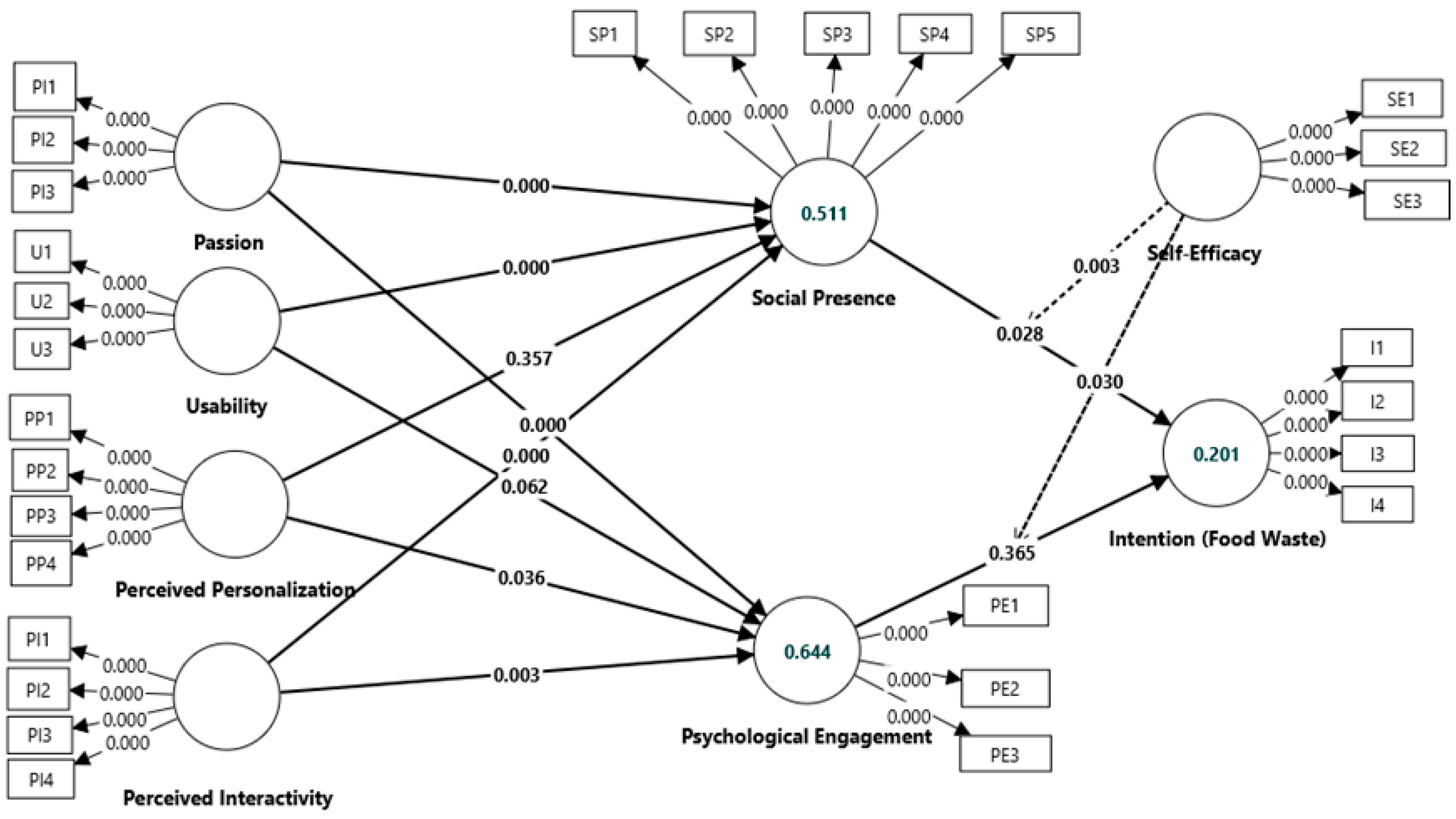

4.2. Multigroup Analysis

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2. Practical and Managerial Implications

5.3. Limitations and Future Research Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhang, Y.; Gupta, V.K.; Karimi, K.; Wang, Y.; Yusoff, M.A.; Vatanparast, H.; Pan, J.; Aghbashlo, M.; Tabatabaei, M.; Rajaei, A. Synergizing blockchain and internet of things for enhancing efficiency and waste reduction in sustainable food management. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2025, 156, 104873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urugo, M.M.; Teka, T.A.; Gemede, H.F.; Mersha, S.; Tessema, A.; Woldemariam, H.W.; Admassu, H. A comprehensive review of current approaches on food waste reduction strategies. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2024, 23, e70011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.P.L. The effects of emotional self-regulation, ethical evaluations and judgments on customer food waste reduction behaviors in restaurants. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2025; ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bravi, L.; Francioni, B.; Murmura, F.; Savelli, E. Factors affecting household food waste among young consumers and actions to prevent it. A comparison among UK, Spain and Italy. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2020, 153, 104586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melnyk, D.; Salem, M.; Ertz, M.; Wagner, R. Being the “Better” student: Intentions to reduce food waste. Discov. Sustain. 2025, 6, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Commission, E. Waste Framework Directive. 2023. Available online: https://environment.ec.europa.eu/topics/waste-and-recycling/waste-framework-directive_en (accessed on 5 July 2023).

- Commission, E. Farm to Fork Strategy. 2023. Available online: https://food.ec.europa.eu/horizontal-topics/farm-fork-strategy_en#F2F-Publications (accessed on 5 May 2020).

- Phonthanukitithaworn, C.; Maitree, N.; Naruetharadhol, P. Eco-innovation policies for food waste management: A European Union-ASEAN comparison. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2024, 10, 100295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartelings, H.; Philippidis, G. A novel macroeconomic modelling assessment of food loss and waste in the EU: An application to the sustainable development goal of halving household food waste. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2024, 45, 567–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eurostata. Food Waste and Food Waste Prevention by NACE Rev. 2 Activity—Tonnes of Fresh Mass. 2025. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/env_wasfw/default/table?lang=en (accessed on 5 May 2025).

- Eičaitė, O.; Baležentis, T. Disentangling the sources and scale of food waste in households: A diary-based analysis in Lithuania. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2024, 46, 195–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salem, M.; Wagner, R. Food waste under pressure: Self-identity, attitudes, overbuying behavior, and consumers’ perceived time pressure. J. Foodserv. Bus. Res. 2025, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazal-e-Hasan, S.M.; Gary, M.; Hormoz, A.; Muhammad, A.; Omar, F.; Amrollahi, A. How tourists’ negative and positive emotions motivate their intentions to reduce food waste. J. Sustain. Tour. 2024, 32, 2039–2059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, S.V.; Young, C.W.; Unsworth, K.L.; Robinson, C. Bringing habits and emotions into food waste behaviour. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2017, 125, 107–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attiq, S.; Chau, K.Y. Sustainability of Household Food Waste Reduction: A Fresh Insight on Youth’s Emotional and Cognitive Behaviors. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 7013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asyari, A.; Susanto, P.; Hoque, M.E.; Widianita, R.; Alam, M.K.; Mamun, A.A. Food waste behavioral intention in Islamic universities: The role of religiosity and pro-social behavior. Int. J. Ethics Syst. 2024; ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsuwaidi, M.; Eid, R.; Agag, G. Tackling the complexity of guests’ food waste reduction behaviour in the hospitality industry. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2022, 42, 100963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obuobi, B.; Zhang, Y.; Adu-Gyamfi, G.; Nketiah, E. Households’ food waste behavior prediction from a moral perspective: A case of China. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2024, 26, 10085–10104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefan, V.; van Herpen, E.; Tudoran, A.A.; Lähteenmäki, L. Avoiding food waste by Romanian consumers: The importance of planning and shopping routines. Food Qual. Prefer. 2013, 28, 375–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.-F. Integrating the extended theory of planned behavior model and the food-related routines to explain food waste behavior. Br. Food J. 2023, 125, 645–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellison, B.; Fan, L.; Wilson, N.L.W. Is it more convenient to waste? Trade-offs between grocery shopping and waste behaviors. Agric. Econ. 2022, 53, 75–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grasso, A.C.; Olthof, M.R.; Boevé, A.J.; van Dooren, C.; Lähteenmäki, L.; Brouwer, I.A. Socio-Demographic Predictors of Food Waste Behavior in Denmark and Spain. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydin, A.E.; Yildirim, P. Understanding food waste behavior: The role of morals, habits and knowledge. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 280, 124250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashton, M.; Hakan, S.; Viachaslau, F.; Gunay, S. Gender dynamics and sustainable practices: Exploring food waste management among female chefs in the hospitality industry. J. Sustain. Tour. 2024, 33, 1658–1683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, D. Beyond the Throwaway Society: Ordinary Domestic Practice and a Sociological Approach to Household Food Waste. Sociology 2012, 46, 41–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Revilla, B.P.; Salet, W. The social meaning and function of household food rituals in preventing food waste. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 198, 320–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elimelech, E.; Mintz, K.K.; Katz-Gerro, T.; Segal-Klein, H.; Hussein, L.; Ayalon, O. Between perceptions and practices: The religious and cultural aspects of food wastage in households. Appetite 2023, 180, 106374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uymaz, P.; Osman, U.A.; Akgül, Y. Assessing the Behavioral Intention of Individuals to Use an AI Doctor at the Primary, Secondary, and Tertiary Care Levels. Int. J. Hum.–Comput. Interact. 2024, 40, 5229–5246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Ong, W.C.; Wong, M.K.F.; Ng, E.Y.K.; Koh, T.; Chandramouli, C.; Ng, C.T.; Hummel, Y.; Huang, F.; Lam, C.S.P.; et al. Applying the UTAUT2 framework to patients’ attitudes toward healthcare task shifting with artificial intelligence. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2024, 24, 455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, N.; Paço, A. AI and emotions: Enhancing green intentions through personalized recommendations—A mediated moderation analysis. AI Soc. 2024, 40, 2821–2838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, J.; Qiu, X.; Wang, Y. The Impact of AI-Personalized Recommendations on Clicking Intentions: Evidence from Chinese E-Commerce. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2025, 20, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polyportis, A.; Pahos, N. Understanding students’ adoption of the ChatGPT chatbot in higher education: The role of anthropomorphism, trust, design novelty and institutional policy. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2025, 44, 315–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, X.; Yuan, Z.; Qu, S. Factors Influencing University Students’ Behavioural Intention to Use Generative Artificial Intelligence for Educational Purposes Based on a Revised UTAUT2 Model. J. Comput. Assist. Learn. 2025, 41, e13105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allahyari, M.S.; Berjan, S.; El Bilali, H.; Ben Hassen, T.; Marzban, S. Assessing the use of ChatGPT among agri-food researchers: A global perspective. J. Agric. Food Res. 2025, 19, 101616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Megha, C.T.; Almeida, S.M. Blossoming Fields: Harnessing Artificial Intelligence for Smart Agritourism. In Cases on AI-Driven Solutions to Environmental Challenges; Tariq, M.U., Sergio, R.P., Eds.; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2025; pp. 213–240. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, B.; Kaunert, C. Revolutionizing Responsible Consumption and Production of Food in Hospitality Industry: Machine Learning and Deep Learning Approach Towards Zero Food Waste. In Sustainable Waste Management in the Tourism and Hospitality Sectors; Sucheran, R., Ed.; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2025; pp. 445–474. [Google Scholar]

- Dakhia, Z.; Russo, M.; Merenda, M. AI-Enabled IoT for Food Computing: Challenges, Opportunities, and Future Directions. Sensors 2025, 25, 2147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Onyeaka, H.; Tamasiga, P.; Nwauzoma, U.M.; Miri, T.; Juliet, U.C.; Nwaiwu, O.; Akinsemolu, A.A. Using Artificial Intelligence to Tackle Food Waste and Enhance the Circular Economy: Maximising Resource Efficiency and Minimising Environmental Impact: A Review. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasool, N.; Bhat, J.I. Artificial Intelligence in Restaurant. In Artificial Intelligence in the Food Industry; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2025; pp. 171–205. [Google Scholar]

- Aijaz, A. Revolutionizing Bakeries with Artificial Intelligence: A Sweet Blend of Innovation. In Artificial Intelligence in the Food Industry; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2025; pp. 153–170. [Google Scholar]

- Tsolakidis, D.; Gymnopoulos, L.P.; Dimitropoulos, K. Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning Technologies for Personalized Nutrition: A Review. Informatics 2024, 11, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, Q.M.; Kanavikar, D.B.; Clark, J.; Donnelly, P.J. Exploring the potential of AI-driven food waste management strategies used in the hospitality industry for application in household settings. Front. Artif. Intell. 2025, 7, 1429477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Li, M.; Li, S.; Chen, K. Understanding Consumers’ Food Waste Reduction Behavior-A Study Based on Extended Norm Activation Theory. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 4187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pandey, S.; Budhathoki, M.; Perez-Cueto, F.J.A.; Thomsen, M. Factors influencing consumers’ food waste reduction behaviour at university canteens. Food Qual. Prefer. 2023, 111, 104991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, L. The effects of self-efficacy and collective efficacy on customer food waste reduction intention: The mediating role of ethical judgment. J. Hosp. Tour. Insights 2022, 5, 752–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filimonau, V.; Matute, J.; Kubal-Czerwińska, M.; Mika, M. How to encourage food waste reduction in kitchen brigades: The underlying role of ‘green’ transformational leadership and employees’ self-efficacy. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2024, 59, 139–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nautiyal, S.; Lal, C. Navigating organic consumption in emerging markets: A comparative study of consumer preferences and market realities in India. Br. Food J. 2025; ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savin, P.S.; Rusu, G.; Prelipcean, M.; Barbu, L.N. Cognitive Shifts: Exploring the Impact of AI on Generation Z and Millennials. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Business Excellence, Bucharest, Romania, 21–23 March 2024; pp. 21–23. [Google Scholar]

- Arachchi, H.A.D.M.; Samarasinghe, G.D. Impact of embedded AI mobile smart speech recognition on consumer attitudes towards AI and purchase intention across Generations X and Y. Eur. J. Manag. Stud. 2024, 29, 3–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alimbayeva, D. Machine Learning Algorithms in UX Design: Enhancing User Experience in Digital Products. ResearchGate 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, L.; Li, G.; Tsai, F.; Gao, C.; Zhu, M.; Qu, X. The impact of artificial intelligence stimuli on customer engagement and value co-creation: The moderating role of customer ability readiness. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2023, 17, 317–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.S.; Minseong, K.; Baek, T.H. Enhancing User Experience with a Generative AI Chatbot. Int. J. Hum.–Comput. Interact. 2025, 41, 651–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Cheung, A.C.K.; Chai, C.S.; Liu, J. Development and validation of the perceived interactivity of learner-AI interaction scale. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2025, 30, 4607–4638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.; Aziz, N.A. Impact of AI on Customer Experience in Video Streaming Services: A Focus on Personalization and Trust. Int. J. Hum.–Comput. Interact. 2024, 41, 7726–7745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doan, M.H.; Drossel, A.-L.; Sassen, R. Sustainable food consumption behaviors of generations Y and Z: A comparison study. Clean. Responsible Consum. 2025, 17, 100272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultan, P.; Wong, H.Y.; Azam, M.S. How perceived communication source and food value stimulate purchase intention of organic food: An examination of the stimulus-organism-response (SOR) model. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 312, 127807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacoby, J. Stimulus-organism-response reconsidered: An evolutionary step in modeling (consumer) behavior. J. Consum. Psychol. 2002, 12, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrabian, A.; Russell, J.A. An approach to Environmental Psychology; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Asante, I.O.; Fang, J.; Darko, D.F. Consumers’ Role in The Survival of E-Commerce in Sub-Saharan Africa: Consequences of E-Service Quality on Engagement Formation. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE 10th Annual Information Technology, Electronics and Mobile Communication Conference (IEMCON), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 19 October 2019; IEEE: New York, NY, USA; pp. 763–770. [Google Scholar]

- Premathilake, G.W.; Li, H.; Li, C.; Liu, Y.; Han, S. Understanding the effect of anthropomorphic features of humanoid social robots on user satisfaction: A stimulus-organism-response approach. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2025, 125, 768–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, P.; Liu, S. The impact of artificial intelligence technology stimuli on sustainable consumption behavior: Evidence from Ant Forest users in China. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Zhao, Z.; Li, L.; Li, Y.; Zhu, M.; Jiao, Y. The relationship between AI stimuli and customer stickiness, and the roles of social presence and customer traits. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2024, 18, 38–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Ren, L.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, D.; Li, L. The impact of artificial intelligence technology stimuli on smart customer experience and the moderating effect of technology readiness. Int. J. Emerg. Mark. 2022, 17, 1123–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jun, K.; Yoon, B. Consumer perspectives on restaurant sustainability: An S-O-R Model approach to affective and cognitive states. J. Foodserv. Bus. Res. 2024, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musiolik, T.H.; Rodriguez, R.V.; Kannan, H. AI impacts in Digital Consumer Behavior; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Kolomaznik, M.; Petrik, V.; Slama, M.; Jurik, V. The role of socio-emotional attributes in enhancing human-AI collaboration. Front. Psychol. 2024, 15, 1369957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Choi, S.M. Antecedents of green purchase behavior: An examination of collectivism, environmental concern, and PCE. Adv. Consum. Res. 2005, 32, 592. [Google Scholar]

- Fakhfakh, A.; Noureldin, A.; Khalifa, T.; Afify, G.; Sumarmi, S.; Al-Hariri, B. AI Stimuli and Responsible Consumer Choices: Understanding the Pathways to Sustainability. J. Int. Crisis Risk Commun. Res. (JICRCR) 2024, 7, 408–423. [Google Scholar]

- Dutta, K.; Pookulangara, S.; Wen, H.; Josiam, B.M.; Parsa, H.G. Hedonic and utilitarian motivations and the role of trust in using food delivery apps: An investigation from a developing economy. J. Foodserv. Bus. Res. 2025, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffin, M.; Babin, B.J.; Modianos, D. Shopping values of Russian consumers: The impact of habituation in a developing economy. J. Retail. 2000, 76, 33–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Wang, X.; Lu, J.; Liu, L.; Feng, Y. The impact of emotional expression by artificial intelligence recommendation chatbots on perceived humanness and social interactivity. Decis. Support Syst. 2024, 187, 114347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attiq, S.; Afzal, H.; Shah, H.J. Predictors of smartphone’s gaming addiction among Generation Z consumers: An empirical investigation from Pakistan. Pak. J. Commer. Soc. Sci. (PJCSS) 2023, 17, 700–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, N.; Lee, H.-K. AI recommendation service acceptance: Assessing the effects of perceived empathy and need for cognition. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2021, 16, 1912–1928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bove, L.L. Empathy for service: Benefits, unintended consequences, and future research agenda. J. Serv. Mark. 2019, 33, 31–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- C Braga, B.; Nguyen, P.H.; Aberman, N.-L.; Doyle, F.; Folson, G.; Hoang, N.; Huynh, P.; Koch, B.; McCloskey, P.; Tran, L. Exploring an artificial intelligence–based, gamified phone app prototype to track and improve food choices of adolescent girls in Vietnam: Acceptability, usability, and likeability study. JMIR Form. Res. 2022, 6, e35197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Lin, Y.; Tang, X.; Deng, S. Fostering netizens to engage in rumour-refuting messages of government social media: A view of persuasion theory. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2024, 43, 2071–2095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, N.; Hamari, J. Does gamification affect brand engagement and equity? A study in online brand communities. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 109, 449–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bul, K.; Holliday, N.; Bhuiyan, M.R.A.; Clark, C.; Allen, J.; Wark, P. Usability and preliminary efficacy of an AI-driven platform supporting dietary management in diabetes: A mixed-method study. JMIR Hum Factors 2022, 10, e43959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaiser, B.; Stelzl, T.; Finglas, P.; Gedrich, K. The Assessment of a Personalized Nutrition Tool (eNutri) in Germany: Pilot Study on Usability Metrics and Users’ Experiences. JMIR Form. Res. 2022, 6, e34497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manser Payne, E.H.; Dahl, A.J.; Peltier, J. Digital servitization value co-creation framework for AI services: A research agenda for digital transformation in financial service ecosystems. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2021, 15, 200–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akdim, K.; Casaló, L.V. Perceived value of AI-based recommendations service: The case of voice assistants. Serv. Bus. 2023, 17, 81–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwivedi, Y.K.; Hughes, L.; Wang, Y.; Alalwan, A.A.; Ahn, S.J.; Balakrishnan, J.; Barta, S.; Belk, R.; Buhalis, D.; Dutot, V. Metaverse marketing: How the metaverse will shape the future of consumer research and practice. Psychol. Mark. 2023, 40, 750–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chattaraman, V.; Kwon, W.-S.; Gilbert, J.E.; Ross, K. Should AI-Based, conversational digital assistants employ social-or task-oriented interaction style? A task-competency and reciprocity perspective for older adults. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2019, 90, 315–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Doorn, J.; Mende, M.; Noble, S.M.; Hulland, J.; Ostrom, A.L.; Grewal, D.; Petersen, J.A. Domo arigato Mr. Roboto: Emergence of automated social presence in organizational frontlines and customers’ service experiences. J. Serv. Res. 2017, 20, 43–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, Y. Intimate exchanges: Using computers to elicit self-disclosure from consumers. J. Consum. Res. 2000, 26, 323–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, D.; Suthar, N. Ethical and legal challenges of AI in marketing: An exploration of solutions. J. Inf. Commun. Ethics Soc. 2024, 22, 124–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, G.D.; Jiang, J.; Freeman, P.A.; Lacanienta, A.; Jamal, T. Leisure as immediate conscious experience: Foundations, evaluation, and extension of the theory of structured experiences. J. Leis. Res. 2020, 51, 581–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teepapal, T. AI-driven personalization: Unraveling consumer perceptions in social media engagement. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2025, 165, 108549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, L.; Antonucci, G.; Venditti, M. Unveiling user responses to AI-powered personalised recommendations: A qualitative study of consumer engagement dynamics on Douyin. Qual. Mark. Res. Int. J. 2025, 28, 234–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrington, N.; Gayle, C.; Hensien, E.; Ko, G.; Lin, M.; Palnati, S.; Gerling, G. Developing a multimodal entertainment tool with intuitive navigation, hands-free control, and avatar features, to increase user interactivity. In Proceedings of the 2022 Systems and Information Engineering Design Symposium (SIEDS), Charlottesville, VA, USA, 28–29 April 2022; pp. 304–309. [Google Scholar]

- Oh, H.J.; Kim, J.; Chang, J.J.; Park, N.; Lee, S. Social benefits of living in the metaverse: The relationships among social presence, supportive interaction, social self-efficacy, and feelings of loneliness. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2023, 139, 107498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Jiang, M.; Li, W.; Mou, J. How does the anthropomorphism of AI chatbots facilitate users’ reuse intention in online health consultation services? The moderating role of disease severity. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2024, 203, 123407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, M.; Yoo, J. Effects of perceived interactivity of augmented reality on consumer responses: A mental imagery perspective. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 52, 101912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pramod, D.; Patil, K.P. Unlocking metaverse flow experience using theory of interactivity and user gratification theory. In Proceedings of the International Working Conference on Transfer and Diffusion of IT, Nagpur, India, 15–16 December 2023; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, Y.; Zhao, L. Emotional design for pro-environmental life: Visual appeal and user interactivity influence sustainable consumption intention with moderating effect of positive emotion. Heliyon 2024, 10, e38521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeves, B.; Nass, C. The media equation: How people treat computers, television, and new media like real people. Cambridge 1996, 10, 19–36. [Google Scholar]

- Short, J. The Social Psychology of Telecommunications; Jhon Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Lim, J.S.; Hwang, Y.; Kim, S.; Biocca, F.A. How social media engagement leads to sports channel loyalty: Mediating roles of social presence and channel commitment. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2015, 46, 158–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adam, M.; Wessel, M.; Benlian, A. AI-based chatbots in customer service and their effects on user compliance. Electron. Mark. 2021, 31, 427–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.; Lee, S.; Kim, D.-Y. Exploring hotel guests’ perceptions of using robot assistants. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2021, 37, 100781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Xin, X.; Zheng, C. The effect of behaviorally anthropomorphic service robots on customers’ variety-seeking behavior: An analytical examination of social presence and decision-making context. Front. Robot. AI 2025, 12, 1503622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, M.; Joshi, S.; Luthra, S.; Kumar, A. Impact of digital assistant attributes on millennials’ purchasing intentions: A multi-group analysis using PLS-SEM, artificial neural network and fsQCA. Inf. Syst. Front. 2024, 26, 943–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, D.S.; Seo, S.; Harrington, R.J.; Martin, D. When virtual others are with me: Exploring the influence of social presence in virtual reality wine tourism experiences. Int. J. Wine Bus. Res. 2024, 36, 548–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramey, H.L.; Rose-Krasnor, L.; Busseri, M.A.; Gadbois, S.; Bowker, A.; Findlay, L. Measuring psychological engagement in youth activity involvement. J. Adolesc. 2015, 45, 237–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsaur, S.-H.; Yen, H.-H. Leisure crafting and pro-environmental behavior: The potential mediating role of engagement. Leis. Sci. 2023, 47, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asante, I.O.; Jiang, Y.; Hossin, A.M.; Luo, X. Optimization of consumer engagement with artificial intelligence elements on electronic commerce platforms. J. Electron. Commer. Res. 2023, 24, 7–28. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A. Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Adv. Behav. Res. Ther. 1978, 1, 139–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H. Media use, environmental beliefs, self-efficacy, and pro-environmental behavior. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 2206–2212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Pandher, J.S.; Prakash, G. Consumer confusion and decision postponement in the online tourism domain: The moderating role of self-efficacy. J. Hosp. Tour. Insights 2023, 6, 1092–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Xu, S.; Ren, Y.; Wang, J. Psychological Changes in Green Food Consumption in the Digital Context: Exploring the Role of Green Online Interactions from a Comprehensive Perspective. Foods 2024, 13, 3001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, P.-S.; Chin, C.-H.; Yi, J.; Wong, W.P.M. Green consumption behaviour among generation Z college students in China: The moderating role of government support. Young Consum. 2024, 25, 507–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, S.; Mohta, A.; Shunmugasundaram, V. Adoption of digital payment FinTech service by Gen Y and Gen Z users: Evidence from India. Digit. Policy Regul. Gov. 2024, 26, 95–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahyuningsih; Nasution, H.; Yeni, Y.H.; Roostika, R. A comparative study of generations X, Y, Z in food purchasing behavior: The relationships among customer value, satisfaction, and Ewom. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2022, 9, 2105585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karunasena, G.G.; Ananda, J.; Pearson, D. Generational differences in food management skills and their impact on food waste in households. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2021, 175, 105890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lissitsa, S. Generations X, Y, Z: The effects of personal and positional inequalities on critical thinking digital skills. Online Inf. Rev. 2025, 49, 35–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, C.-H.; Wong, W.P.M.; Cham, T.-H.; Thong, J.Z.; Ling, J.P.-W. Exploring the usage intention of AI-powered devices in smart homes among millennials and zillennials: The moderating role of trust. Young Consum. 2024, 25, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aktas, E.; Sahin, H.; Topaloglu, Z.; Oledinma, A.; Huda, A.K.S.; Irani, Z.; Sharif, A.M.; Wout, T.V.; Kamrava, M. A consumer behavioural approach to food waste. J. Enterp. Inf. Manag. 2018, 31, 658–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholderer, J.; Brunsø, K.; Bredahl, L.; Grunert, K.G. Cross-cultural validity of the food-related lifestyles instrument (FRL) within Western Europe. Appetite 2004, 42, 197–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stancu, V.; Haugaard, P.; Lähteenmäki, L. Determinants of consumer food waste behaviour: Two routes to food waste. Appetite 2016, 96, 7–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldus, B.J.; Voorhees, C.; Calantone, R. Online brand community engagement: Scale development and validation. J. Bus. Res. 2015, 68, 978–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, S.K.; Singh, G.; Hope, M.; Icon, B.N.R.I.; Harrigan, P. The rise of smart consumers: Role of smart servicescape and smart consumer experience co-creation. In The Role of Smart Technologies in Decision Making; Routledge: London, UK, 2022; pp. 114–147. [Google Scholar]

- Gefen, D.; Straub, D. Managing user trust in B2C e-services. e-Service 2003, 2, 7–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, J.; Zhao, Z.; Wen, C.; Wang, R. Design and performance attributes driving mobile travel application engagement. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2017, 37, 269–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speier, C.; Frese, M. Generalized self-efficacy as a mediator and moderator between control and complexity at work and personal initiative: A longitudinal field study in East Germany. In Organizational Citizenship Behavior and Contextual Performance; Psychology Press: Hove, UK, 2014; pp. 171–192. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Risher, J.J.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M. When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2019, 31, 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F., Jr. Successful strategies for teaching multivariate statistics. In Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on ICOTS-7, Salvador, Brazil, 2 July 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Yi, Y. On the evaluation of structural equation models. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1988, 16, 74–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarstedt, M.; Hopkins, L.; Kuppelwieser, V.G. Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM): An emerging tool in business research. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2014, 26, 106–121. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, Y.; Hu, J.; Chen, M.; Tang, S. Motives and antecedents affecting green purchase intention: Implications for green economic recovery. Econ. Anal. Policy 2023, 77, 523–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, W.-T.; Ng, E.; Wang, C.-M.; Hsu, M.-L. Normative beliefs, attitudes, and social norms: People reduce waste as an index of social relationships when spending leisure time. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venessa, K.; Aripradono, H.W. Usage of gamification and mobile application to reduce food loss and waste: A case study of Indonesia. J. Inf. Syst. Inform. 2023, 5, 102–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, X.; Silpasuwanchai, C.; Cahill, J. Human-engaged computing: The future of human–computer interaction. CCF Trans. Pervasive Comput. Interact. 2019, 1, 47–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Category | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 238 | 76% |

| Female | 76 | 24% |

| Other | 2 | 1% |

| Age | ||

| 16–27 | 119 | 38% |

| 28–43 | 196 | 62% |

| Education | ||

| Basic primary education | 9 | 3% |

| Secondary education | 49 | 16% |

| Higher secondary education and special education | 22 | 7% |

| College education | 15 | 5% |

| Higher education (non-university level) | 58 | 18% |

| Higher education (university level) | 162 | 51% |

| Monthly Income | ||

| No income | 17 | 5% |

| Less than EUR 350 | 14 | 4% |

| EUR 351–450 | 9 | 3% |

| EUR 451–550 | 14 | 4% |

| EUR 551–750 | 13 | 4% |

| EUR 751–950 | 37 | 12% |

| EUR 951–1500 | 101 | 32% |

| EUR 1501–2000 | 70 | 22% |

| EUR 2001–2500 | 24 | 8% |

| EUR 2501–3000 | 8 | 3% |

| EUR 3001–4000 | 5 | 2% |

| EUR 4001 and above | 3 | 1% |

| Variables | Items | Factor Loading | Cronbach’s Alpha | Composite Reliability | Average Variance Extracted |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Passion | 0.890 | 0.932 | 0.820 | ||

| PI1 | 0.899 | ||||

| PI2 | 0.922 | ||||

| PI3 | 0.905 | ||||

| Usability | 0.884 | 0.928 | 0.811 | ||

| U1 | 0.903 | ||||

| U2 | 0.921 | ||||

| U3 | 0.878 | ||||

| Perceived Personalization | 0.855 | 0.902 | 0.696 | ||

| PP1 | 0.843 | ||||

| PP2 | 0.842 | ||||

| PP3 | 0.825 | ||||

| PP4 | 0.828 | ||||

| Perceived Interactivity | 0.829 | 0.886 | 0.661 | ||

| PI1 | 0.782 | ||||

| PI2 | 0.823 | ||||

| PI3 | 0.817 | ||||

| PI4 | 0.829 | ||||

| Social Presence | 0.906 | 0.931 | 0.730 | ||

| SP1 | 0.882 | ||||

| SP2 | 0.740 | ||||

| SP3 | 0.862 | ||||

| SP4 | 0.891 | ||||

| SP5 | 0.886 | ||||

| Psychological Engagement | 0.767 | 0.864 | 0.682 | ||

| PE1 | 0.893 | ||||

| PE2 | 0.868 | ||||

| PE3 | 0.703 | ||||

| Self-Efficacy | |||||

| SE1 | 0.661 | ||||

| SE2 | 0.851 | ||||

| SE3 | 0.838 | ||||

| Intentions to Reduce Food Waste | 0.800 | 0.868 | 0.622 | ||

| I1 | 0.808 | ||||

| I2 | 0.739 | ||||

| I3 | 0.805 | ||||

| I4 | 0.799 |

| I | P | PI | PP | PE | SE | SP | U | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intentions to Reduce Food Waste | 0.788 | |||||||

| Passion | 0.239 | 0.906 | ||||||

| Perceived Interactivity | 0.376 | 0.658 | 0.813 | |||||

| Perceived Personalization | 0.332 | 0.658 | 0.781 | 0.834 | ||||

| Psychological Engagement | 0.209 | 0.758 | 0.677 | 0.664 | 0.826 | |||

| Self-Efficacy | 0.396 | 0.303 | 0.348 | 0.400 | 0.361 | 0.788 | ||

| Social Presence | 0.219 | 0.617 | 0.654 | 0.576 | 0.637 | 0.243 | 0.854 | |

| Usability | 0.204 | 0.703 | 0.696 | 0.721 | 0.663 | 0.311 | 0.630 | 0.901 |

| HTMT | ||||||||

| Passion | 0.267 | |||||||

| Perceived Interactivity | 0.456 | 0.763 | ||||||

| Perceived Personalization | 0.402 | 0.751 | 0.832 | |||||

| Psychological Engagement | 0.295 | 0.806 | 0.825 | 0.790 | ||||

| Self-Efficacy | 0.528 | 0.384 | 0.451 | 0.512 | 0.489 | |||

| Social Presence | 0.244 | 0.687 | 0.750 | 0.652 | 0.772 | 0.312 | ||

| Usability | 0.229 | 0.787 | 0.811 | 0.825 | 0.781 | 0.394 | 0.700 |

| Hypothesis | Relationship | Beta | T-Value | p-Value | Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | Passion → Social Presence | 0.233 | 3.365 | 0.001 | Accepted |

| H2 | Passion → Psychological Engagement | 0.476 | 7.463 | 0.000 | Accepted |

| H3 | Usability → Social Presence | 0.238 | 3.354 | 0.001 | Accepted |

| H4 | Usability → Psychological Engagement | 0.103 | 1.541 | 0.123 | Rejected |

| H5 | Perceived Personalization → Social Presence | −0.028 | 0.365 | 0.715 | Rejected |

| H6 | Perceived Personalization → Psychological Engagement | 0.126 | 1.798 | 0.072 | Rejected |

| H7 | Perceived Interactivity → Social Presence | 0.357 | 4.821 | 0.000 | Accepted |

| H8 | Perceived Interactivity → Psychological Engagement | 0.193 | 2.717 | 0.007 | Accepted |

| H9 | Social presence → Intentions to reduce food waste | 0.146 | 1.914 | 0.056 | Rejected |

| H10 | Psychological Engagement → Intentions to reduce food waste | 0.028 | 0.346 | 0.729 | Rejected |

| H11(a) | Passion → Social Presence → Intentions to reduce food waste | 0.034 | 1.473 | 0.141 | Rejected |

| H11(b) | Usability → Social Presence → Intentions to reduce food waste | 0.035 | 1.796 | 0.072 | Rejected |

| H11(c) | Perceived Personalization → Social Presence → Intentions to reduce food waste | −0.004 | 0.322 | 0.748 | Rejected |

| H11(d) | Perceived Interactivity → Social Presence → Intentions to reduce food waste | 0.052 | 1.744 | 0.081 | Rejected |

| H12(a) | Passion → Psychological Engagement → Intentions to reduce food waste | 0.013 | 0.341 | 0.733 | Rejected |

| H12(b) | Usability → Psychological Engagement → Intentions to reduce food waste | 0.003 | 0.289 | 0.773 | Rejected |

| H12(c) | Perceived Personalization → Psychological Engagement → Intentions to reduce food waste | 0.003 | 0.304 | 0.761 | Rejected |

| H12(d) | Perceived Interactivity → Psychological Engagement → Intentions to reduce food waste. | 0.005 | 0.316 | 0.752 | Rejected |

| H13(a) | Self-Efficacy × Social Presence → Intentions to reduce food waste | −0.185 | 2.800 | 0.005 | Accepted |

| H13(b) | Self-Efficacy × Psychological Engagement → Intentions to reduce food waste | 0.125 | 1.876 | 0.061 | Rejected |

| Hypothesis | Relationship | Gen Y | Gen Z | Diff | PLS MGA Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | Passion → Social Presence | 0.262 | 0.131 | 0.131 | 0.181 |

| H2 | Passion → Psychological Engagement | 0.456 | 0.484 | −0.028 | 0.405 |

| H3 | Usability → Social Presence | 0.302 | 0.113 | 0.189 | 0.113 |

| H4 | Usability → Psychological Engagement | 0.174 | 0.001 | 0.173 | 0.118 |

| H5 | Perceived Personalization → Social Presence | −0.126 | 0.199 | −0.325 | 0.013 |

| H6 | Perceived Personalization → Psychological Engagement | 0.027 | 0.246 | −0.219 | 0.059 |

| H7 | Perceived Interactivity → Social Presence | 0.413 | 0.297 | 0.116 | 0.213 |

| H8 | Perceived Interactivity → Psychological Engagement | 0.261 | 0.131 | 0.130 | 0.178 |

| H9 | Social Presence → Intentions | 0.184 | 0.103 | 0.081 | 0.328 |

| H10 | Psychological Engagement → Intentions | −0.049 | 0.097 | −0.146 | 0.192 |

| H11(a) | Passion → Social Presence → Intentions | 0.048 | 0.014 | 0.034 | 0.200 |

| H11(b) | Usability → Social Presence → Intentions | 0.056 | 0.012 | 0.044 | 0.139 |

| H11(c) | Perceived Personalization → Social Presence → Intentions | −0.023 | 0.021 | −0.044 | 0.136 |

| H11(d) | Perceived Interactivity → Social Presence → Intentions | 0.076 | 0.031 | 0.045 | 0.237 |

| H12(a) | Passion → Psychological Engagement → Intentions | −0.022 | 0.047 | −0.069 | 0.202 |

| H12(b) | Usability → Psychological Engagement → Intentions | −0.009 | 0.000 | −0.009 | 0.344 |

| H12(c) | Perceived Personalization → Psychological Engagement → Intentions | −0.001 | 0.024 | −0.025 | 0.248 |

| H12(d) | Perceived Interactivity → Psychological Engagement → Intentions | −0.013 | 0.013 | −0.026 | 0.224 |

| H13(a) | Self-Efficacy x Social Presence → Intentions | −0.279 | −0.062 | −0.217 | 0.089 |

| H13(b) | Self-Efficacy x Psychological Engagement → Intentions | 0.214 | 0.059 | 0.155 | 0.132 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Mansoor, R.; Rūtelione, A.; Bhutto, M.Y. From Pixels to Plates: Exploring AI Stimuli and Digital Engagement in Reducing Food Waste Behavior in Lithuania Among Generation Z and Y. Sustainability 2026, 18, 495. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010495

Mansoor R, Rūtelione A, Bhutto MY. From Pixels to Plates: Exploring AI Stimuli and Digital Engagement in Reducing Food Waste Behavior in Lithuania Among Generation Z and Y. Sustainability. 2026; 18(1):495. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010495

Chicago/Turabian StyleMansoor, Rafiq, Ausra Rūtelione, and Muhammad Yassen Bhutto. 2026. "From Pixels to Plates: Exploring AI Stimuli and Digital Engagement in Reducing Food Waste Behavior in Lithuania Among Generation Z and Y" Sustainability 18, no. 1: 495. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010495

APA StyleMansoor, R., Rūtelione, A., & Bhutto, M. Y. (2026). From Pixels to Plates: Exploring AI Stimuli and Digital Engagement in Reducing Food Waste Behavior in Lithuania Among Generation Z and Y. Sustainability, 18(1), 495. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010495