1. Introduction

Global freshwater scarcity continues to intensify, particularly across arid and semi-arid regions where rainfall is limited and groundwater reserves are highly saline. Conventional desalination systems, although technologically mature, remain heavily dependent on fossil fuels and centralized infrastructure, making them environmentally unsustainable and economically burdensome for remote communities. Recent studies have therefore emphasized the need for decentralized, low-cost, and renewable-water production technologies capable of operating under harsh climatic conditions [

1,

2]. Among these technologies, solar stills (SSs) remain attractive due to their simplicity, minimal maintenance requirements, and ability to operate solely on solar energy [

3,

4].

While the passive single-slope solar still (SSSS) is the most widely used configuration, its major limitation is low productivity, typically ranging between 2 and 5 L/m

2·day under typical weather conditions [

5]. This has driven extensive research toward enhancing heat and mass transfer processes through novel passive and active modification techniques. Recent advancements include geometric redesigns double slope, stepped, pyramid, tubular, hemispherical, and conical stills, which have shown meaningful productivity gains due to improved evaporation–condensation dynamics [

3,

6]. For instance, El-Maghlany et al. [

6] experimentally compared three designs and observed daily yields of 5.80 L/m

2·day for conical stills, outperforming conventional single-slope systems.

Another major research direction involves the incorporation of conductive structures such as tubes, parabolic fins, and metallic inserts to intensify heat absorption and distribution. Kaviti et al. [

1] reported that coupling copper tubes and parabolic fins increased annual distillate yield by nearly 58% compared with a baseline still. Similarly, stepped stills enhanced with magnetic rings or micro-charcoal loading exhibited over 100% productivity improvement due to increased convective and radiative heat transfer [

2]. These modifications demonstrate that relatively simple structural changes can significantly improve thermodynamic performance without major increases in system complexity.

In parallel, advanced materials have emerged as a transformative pathway for elevating still efficiency. Nanofluids (e.g., CuO, Al

2O

3, TiO

2) enhance solar absorption and thermal conductivity, resulting in higher evaporation rates. Zanganeh et al. and Sahota et al. reported productivity improvements between 20 and 32% using selective nanocoatings and nanoparticle-enhanced working fluids [

5]. Tubular solar stills modified with

γ-Al

2O

3 nanocoatings demonstrated up to 60% thermal efficiency and significantly lower cost per liter (0.10 USD/L), highlighting the economic feasibility of nanotechnology-based enhancements [

7].

Complementary efforts have focused on thermal energy storage using phase change materials (PCMs) to extend night-time productivity. Studies have shown performance gains between 50 and 233% when using paraffin wax, metal-oxide nano-PCM composites, gravel, pebble stones, or hybrid PCM-wick systems [

8]. Hybridization with thermoelectric modules (TEMs) has also shown promise in increasing evaporation (heating mode) or enhancing condensation (cooling mode), with reported productivity enhancements exceeding 200–600% in optimized configurations [

5]. While these enhancements provide valuable technical insights, many introduce additional energy inputs, high material costs, or fabrication complexity that can hinder real-world deployment in low-income regions.

Table 1 summarizes a selection of recent studies (2021–2025) that illustrate the range and efficacy of enhancement techniques applied to solar stills. The table includes various still configurations, such as tubular, pyramid, spherical, and stepped designs, as well as experimental investigations and review articles. Each entry highlights the specific modification employed and the corresponding improvement in productivity or thermal efficiency.

As summarized in

Table 1, numerous studies have attempted to enhance solar still performance using fins, magnets, tubular designs, thermal storage materials, hybridization with collectors, and other strategies. These modifications have indeed led to significant improvements in productivity under certain controlled experimental conditions and constant water properties, in addition to a significant increase in cost. However, most of these studies focus on modified configurations rather than evaluating the baseline performance of a conventional single-slope solar still under extreme climatic conditions. In particular, there is a scarcity of works that combine detailed transient heat-mass transfer modeling with experimental data for a conventional still in an environment characterized by high ambient temperatures and intense solar radiation conditions typical of southern Iraq. Thus, there is a clear need to provide a rigorous validation of a conventional still’s performance under such harsh conditions, to define a reliable baseline before deploying more complex modifications. The present study aims to fill this gap by conducting such a combined experimental–theoretical investigation.

Despite significant progress in enhancing solar still productivity through geometric, material, and hybrid modifications, most prior studies have been performed on modified or hybrid systems operating under moderate climatic conditions, and most of them were experimental without mathematical analysis. Many enhancement strategies involve additional material costs, complex fabrication, or require controlled experimental environments, all of which limit scalability and reduce the feasibility of deployment in resource-constrained or remote regions. This creates a critical knowledge gap: the natural performance potential of conventional solar stills under genuinely extreme climates remains insufficiently documented, despite being the conditions where such systems are most urgently needed.

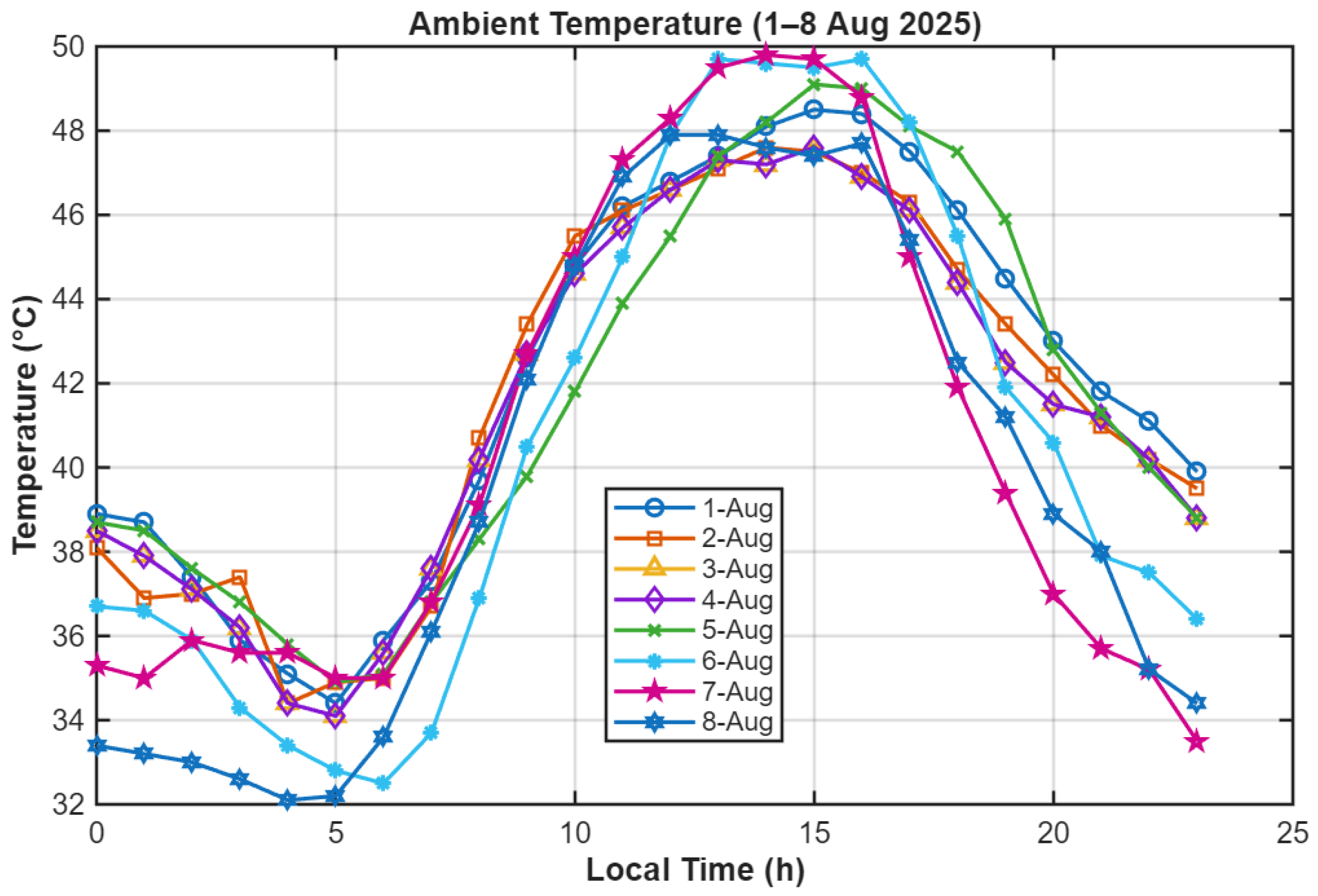

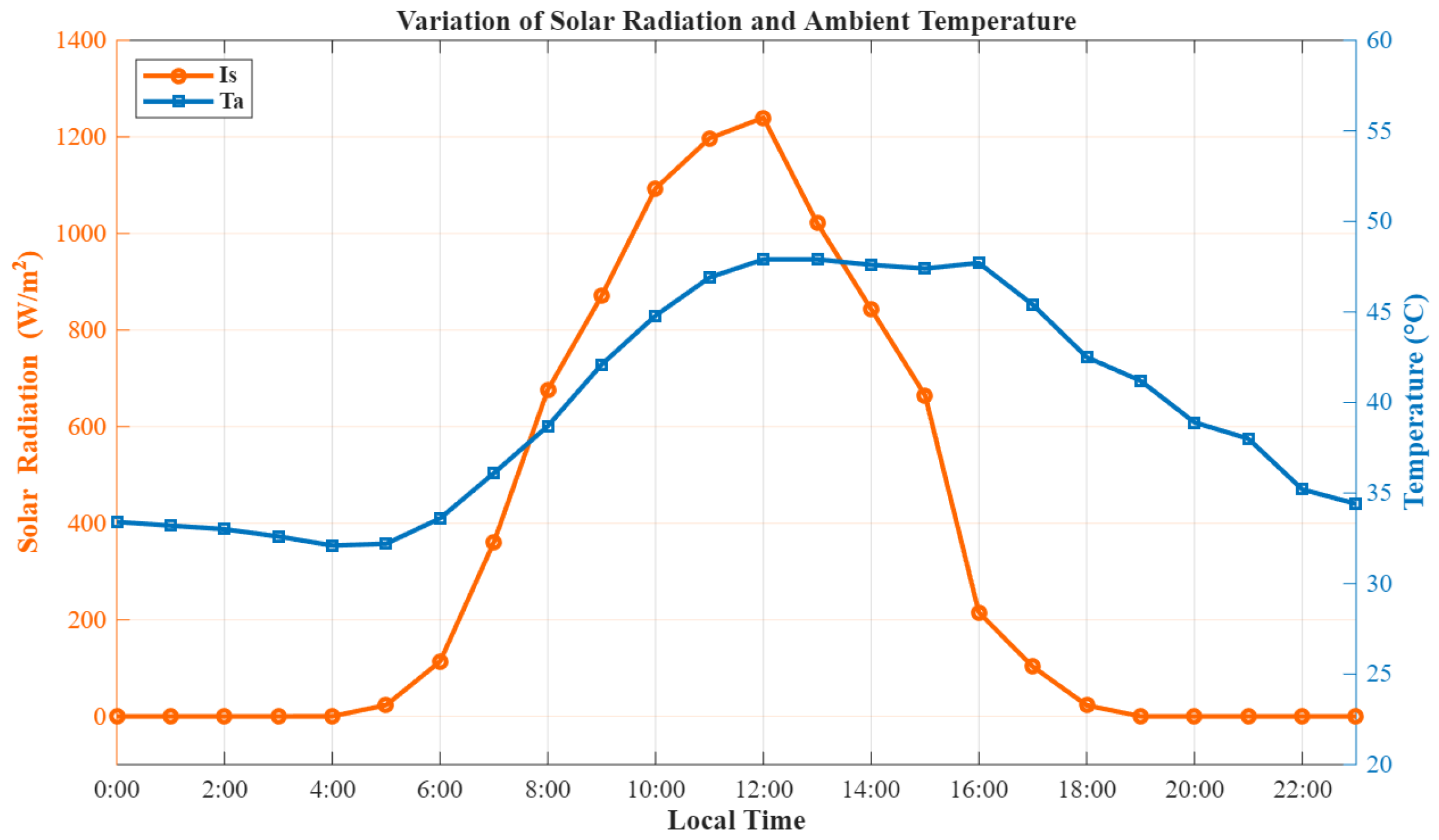

Addressing this problem statement is particularly relevant for regions like southern Iraq, where ambient temperatures routinely exceed 45 °C, solar radiation is intense, and water sources such as the Shatt al-Arab River exhibit variable salinity, with increased salinity in summer due to low river water levels and drought. Evaluating solar stills under these environmental stresses is essential for establishing realistic performance expectations and for identifying cost-effective design improvements suitable for harsh climates.

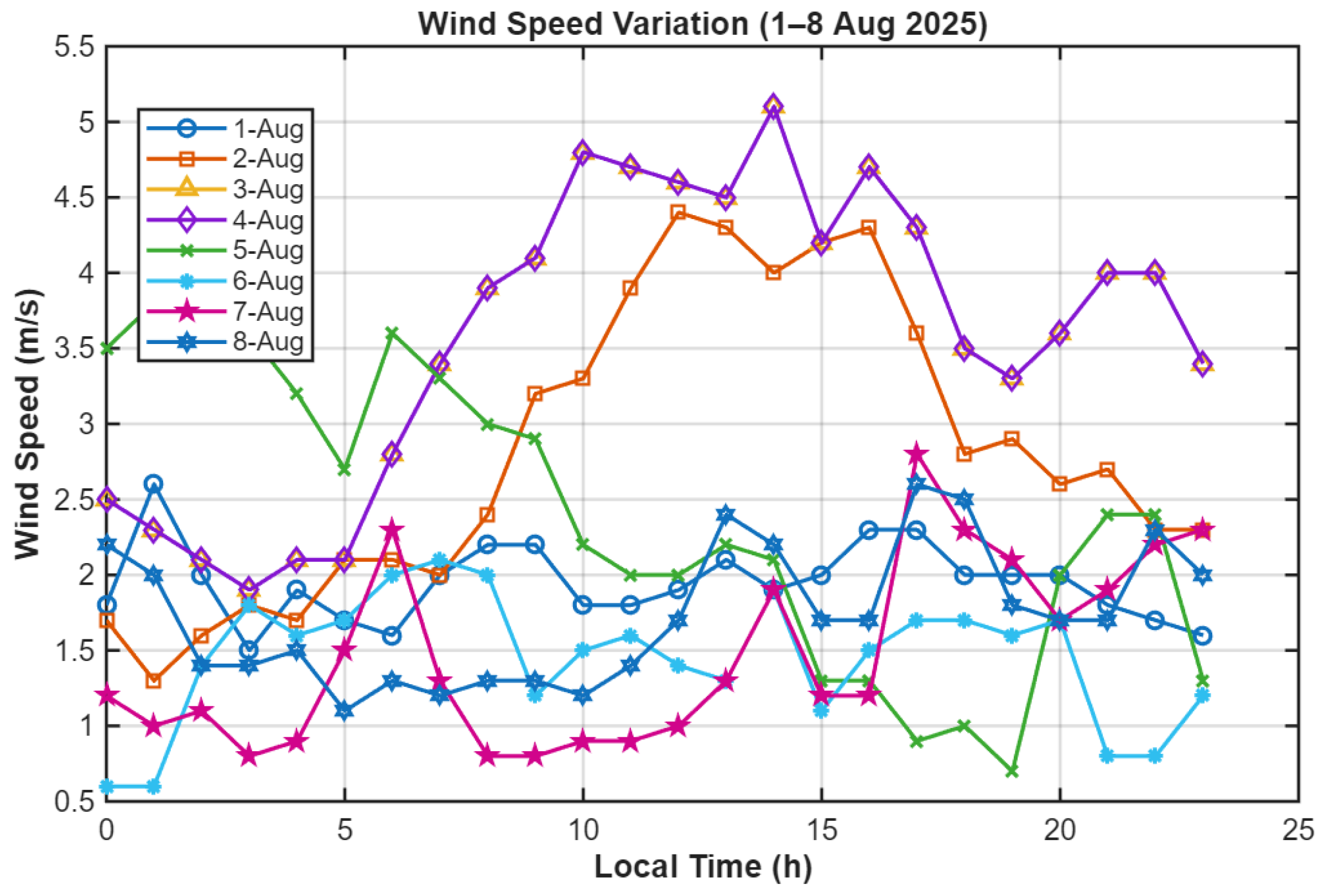

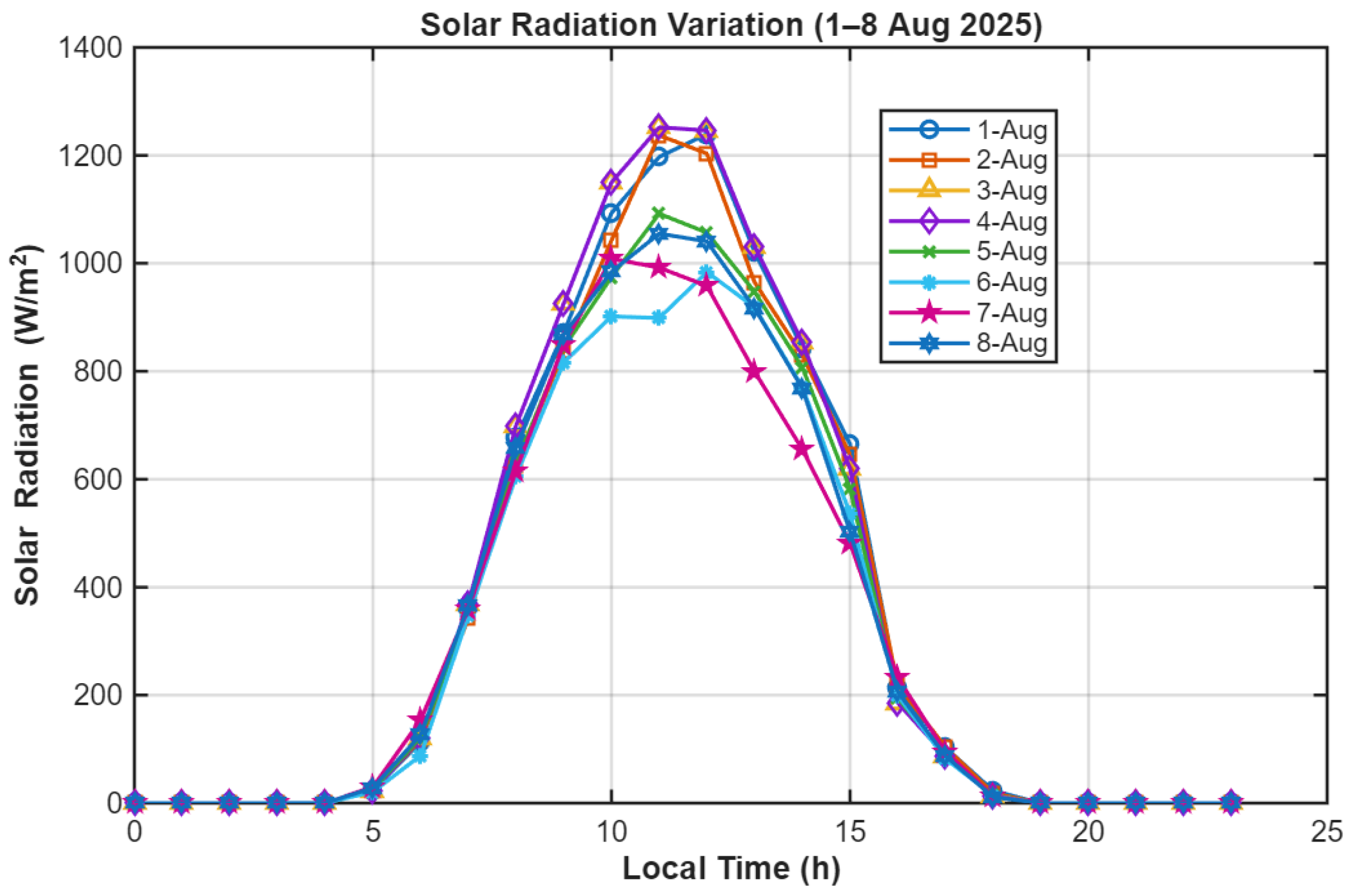

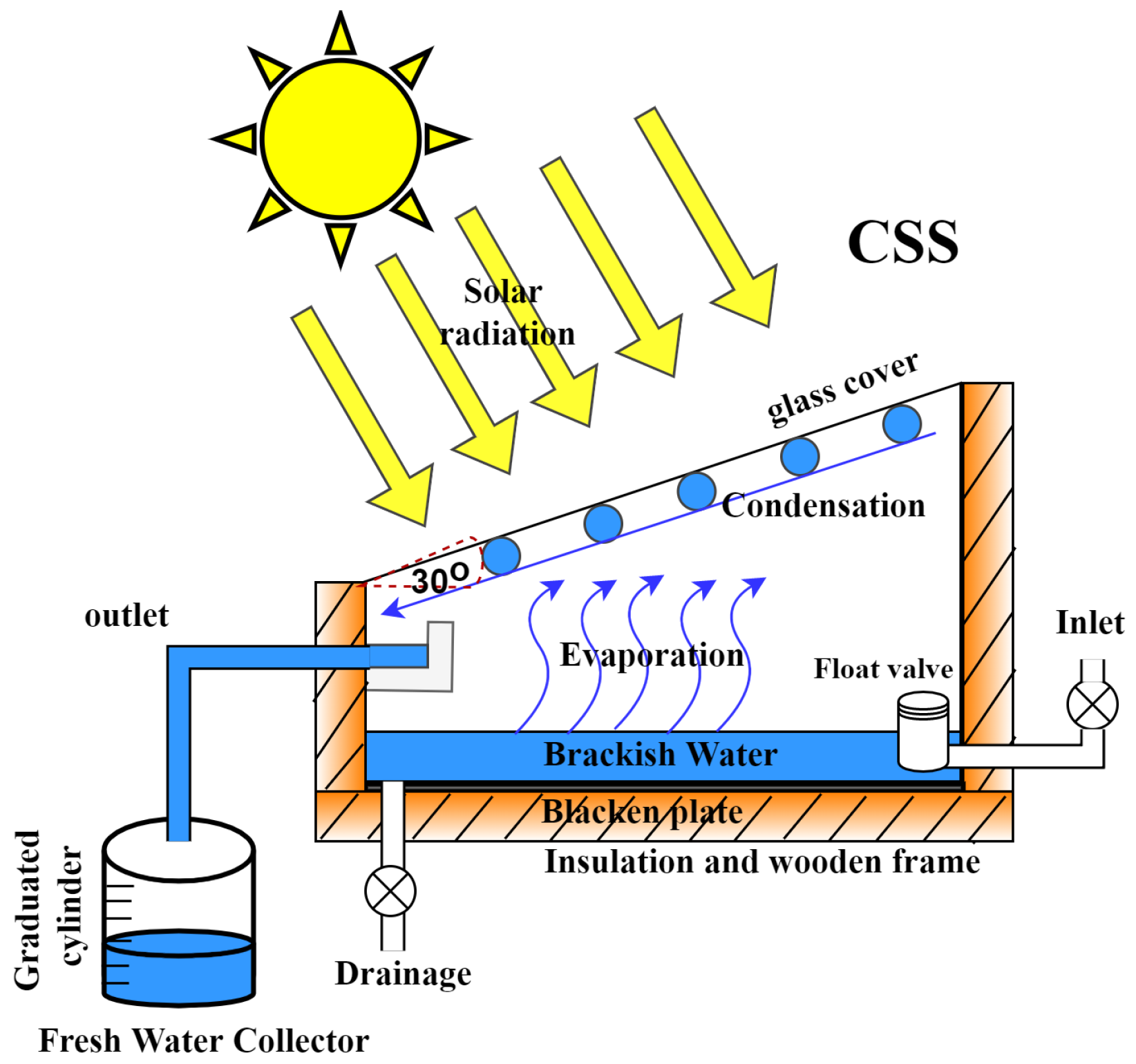

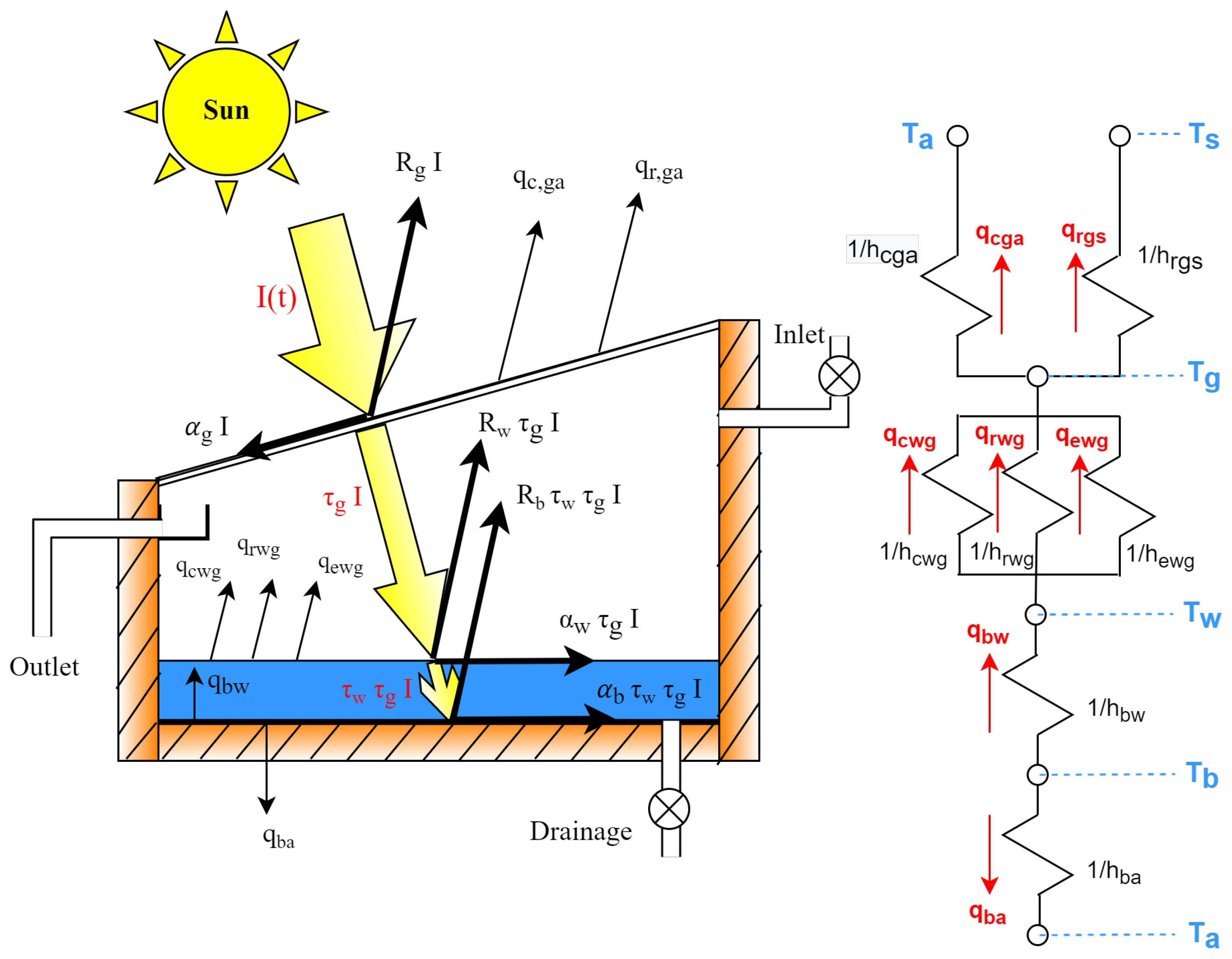

In this context, the present work conducts a combined experimental and theoretical investigation of a conventional single-slope solar still operating under the harsh summer climate of Basrah, Iraq. The still was fed with brackish water from the Shatt al-Arab River to emulate field-relevant salinity conditions. A transient heat and mass transfer model was developed to predict temperature distributions and hourly freshwater productivity. A key novelty of this study lies in the incorporation of temperature and salinity dependent correlations for specific heat capacity, density, and latent heat of vaporization. Unlike previous models that assume constant thermophysical properties (e.g., , , ), the present approach accounts for dynamic variations in fluid properties driven by extreme ambient heating and brine concentration.

This methodological advancement significantly improves the predictive accuracy of evaporation–condensation modeling under extreme conditions, where temperatures often exceed 45 °C and salinity can vary widely. The results not only provide insight into the natural performance capabilities of traditional solar still designs but also address a critical research gap by combining rigorous experimental validation with advanced variable-property theoretical modeling. The ultimate aim is to establish a reliable baseline for future optimization and guide the development of cost-effective enhancement strategies suitable for deployment in similarly harsh environments.

Despite significant progress, a persistent gap remains in validating solar-still performance under actual field conditions using real-time meteorological data, particularly in regions experiencing extreme temperatures such as southern Iraq. As many published studies use averaged climatic data or assume constant environmental boundary conditions, which can mask the real diurnal variability of solar radiation, ambient temperature, and humidity factors that strongly affect evaporation–condensation dynamics in field-deployed solar stills [

22,

23]. As highlighted in recent reviews and by the present study’s motivation, authentic experimental evaluation combined with transient modeling is essential for understanding system performance under the extreme weather patterns characteristic of Middle Eastern climates [

4,

6].

Given this context, the present study experimentally investigates a conventional single-slope basin solar still installed in Basrah, Iraq, integrating hourly real-time weather data from an on-site CURCONSA FT0300 meteorological station. A temperature- and salinity-dependent transient model is developed and validated using field measurements, with the following objectives:

Develop and validate a temperature- and salinity-dependent transient heat mass transfer model for a conventional single-slope solar still;

Quantify the influence of solar radiation, ambient temperature, water depth, and wind speed on evaporative productivity;

Compared the measured productivity against recent literature to identify practical pathways for improvement.

The findings presented herein contribute a realistic and scientifically robust performance baseline for solar stills operating under extreme climatic conditions and highlight the importance of variable property modeling and localized real-time data for accurate system prediction and future design optimization.

This study also aligns with broader global sustainability objectives as framed by the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). In particular, it contributes to SDG 6 (Clean Water and Sanitation) by demonstrating a decentralized, low energy option for freshwater production in arid regions, to SDG 7 (Affordable and Clean Energy) by relying exclusively on solar energy as a renewable thermal source; and to SDG 13 (Climate Action) by offering a desalination approach that does not depend on fossil fuel-based power. In this way, the proposed solar still concept addresses interconnected water energy climate challenges in a manner that is both environmentally and socially sustainable.

This paper is organized into six main sections to systematically present the study’s objectives, methodologies, theoretical background, experimental analysis, and final conclusions. In

Section 1 (Introduction), we outline the motivation, background, and significance of the study, along with the key research questions and objectives.

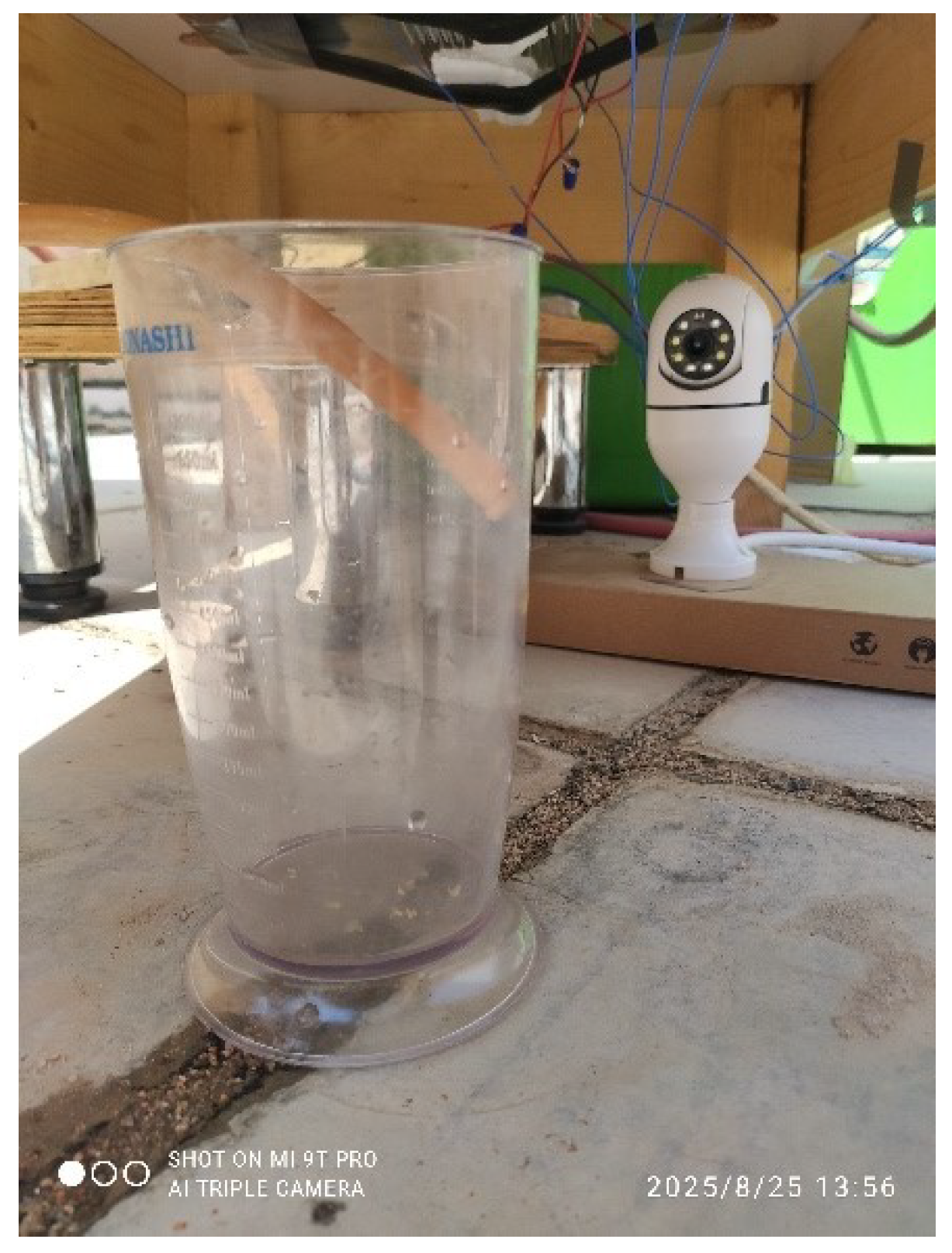

Section 2 (Materials and Methods) describes the experimental setup, instrumentation, procedures, and materials used to conduct the study, ensuring reproducibility and clarity in the research methodology.

Section 3 (Theoretical Analyses) provides the underlying theoretical framework and models used to interpret the physical phenomena involved, offering a deeper understanding of the mechanisms at play.

Section 4 (Uncertainty Analysis of Experimental Measurements) addresses the precision and reliability of the measurements through a detailed uncertainty analysis, which is essential for validating the experimental outcomes.

Section 5 (Results and Discussion) presents and interprets the results obtained from both theoretical and experimental approaches, including comparisons, graphical representations, and in-depth discussion. Finally,

Section 6 (Conclusions) summarizes the main findings, highlights the contributions of the study, and suggests directions for future work.

6. Conclusions and Research Implications

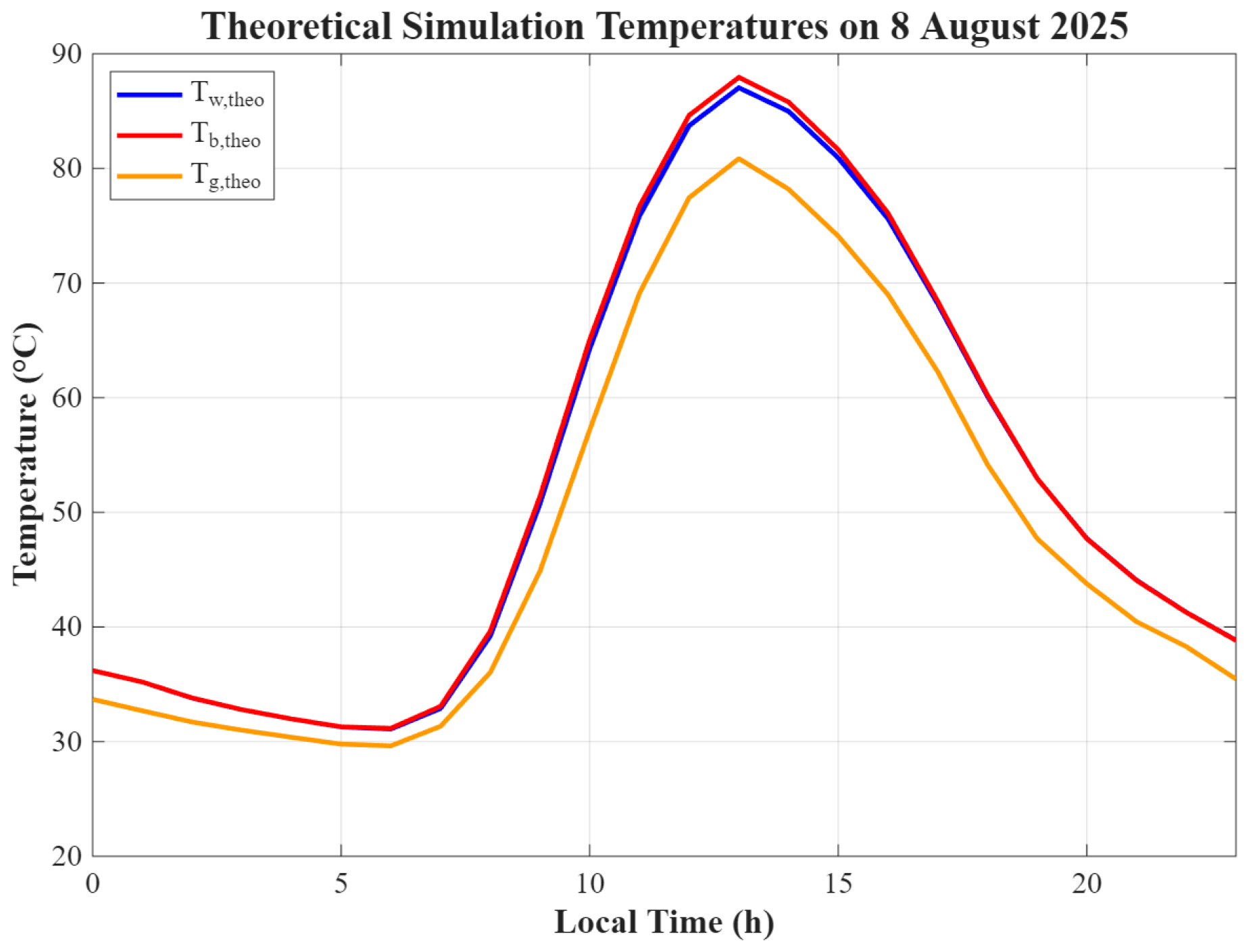

This work presented an integrated experimental and numerical investigation of a conventional single-slope basin solar still operating under the severe summer conditions of Basrah, Iraq. Continuous measurements from an on-site weather station were used to drive and validate a transient heat and mass transfer model that accounts for the dependence of saline water properties (latent heat, density, and specific heat) on both temperature and salinity. Incorporating variable properties rather than assuming constant values resulted in a closer match between simulation and experiment and provides a more realistic description of the physical processes inside the still.

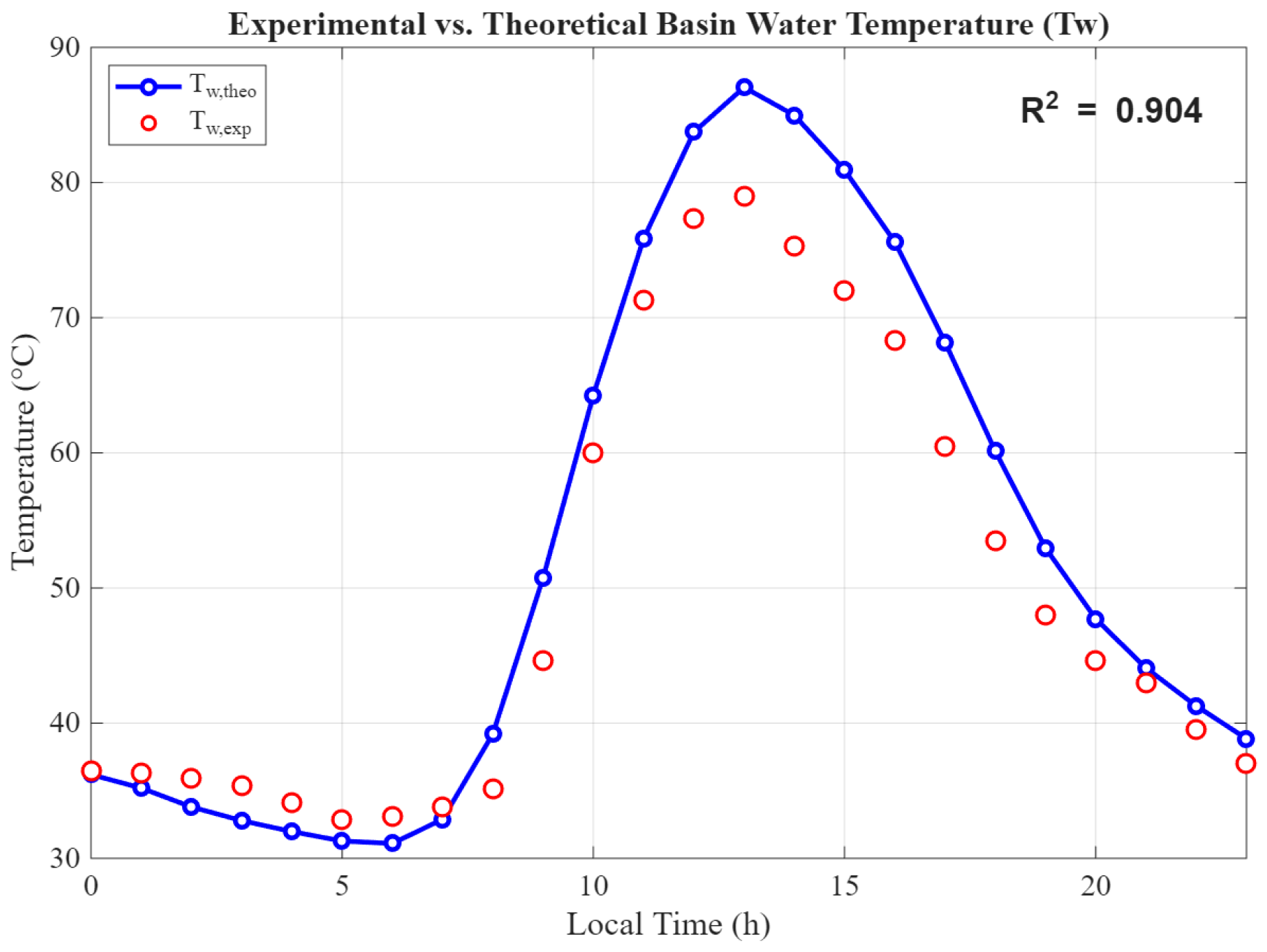

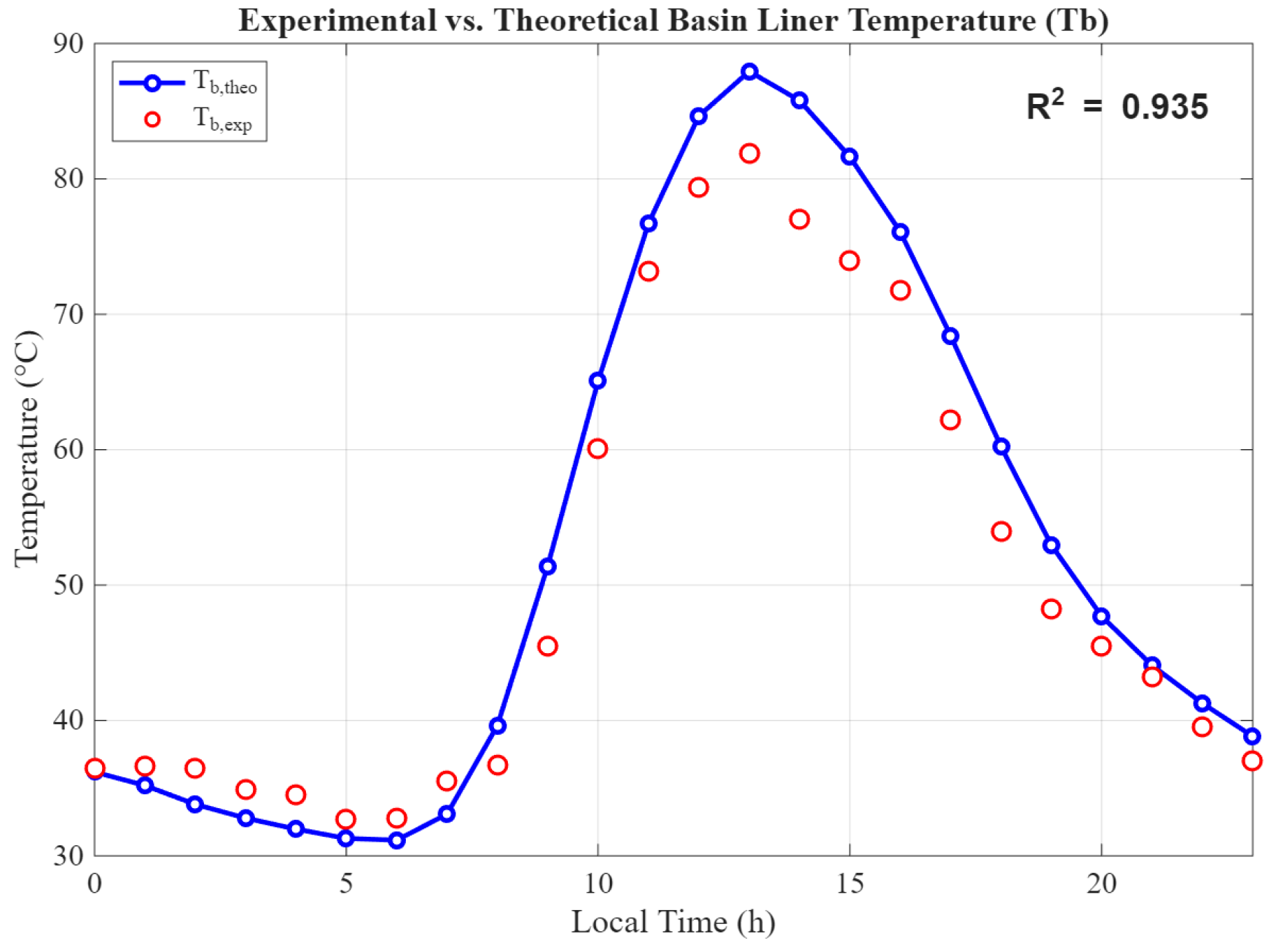

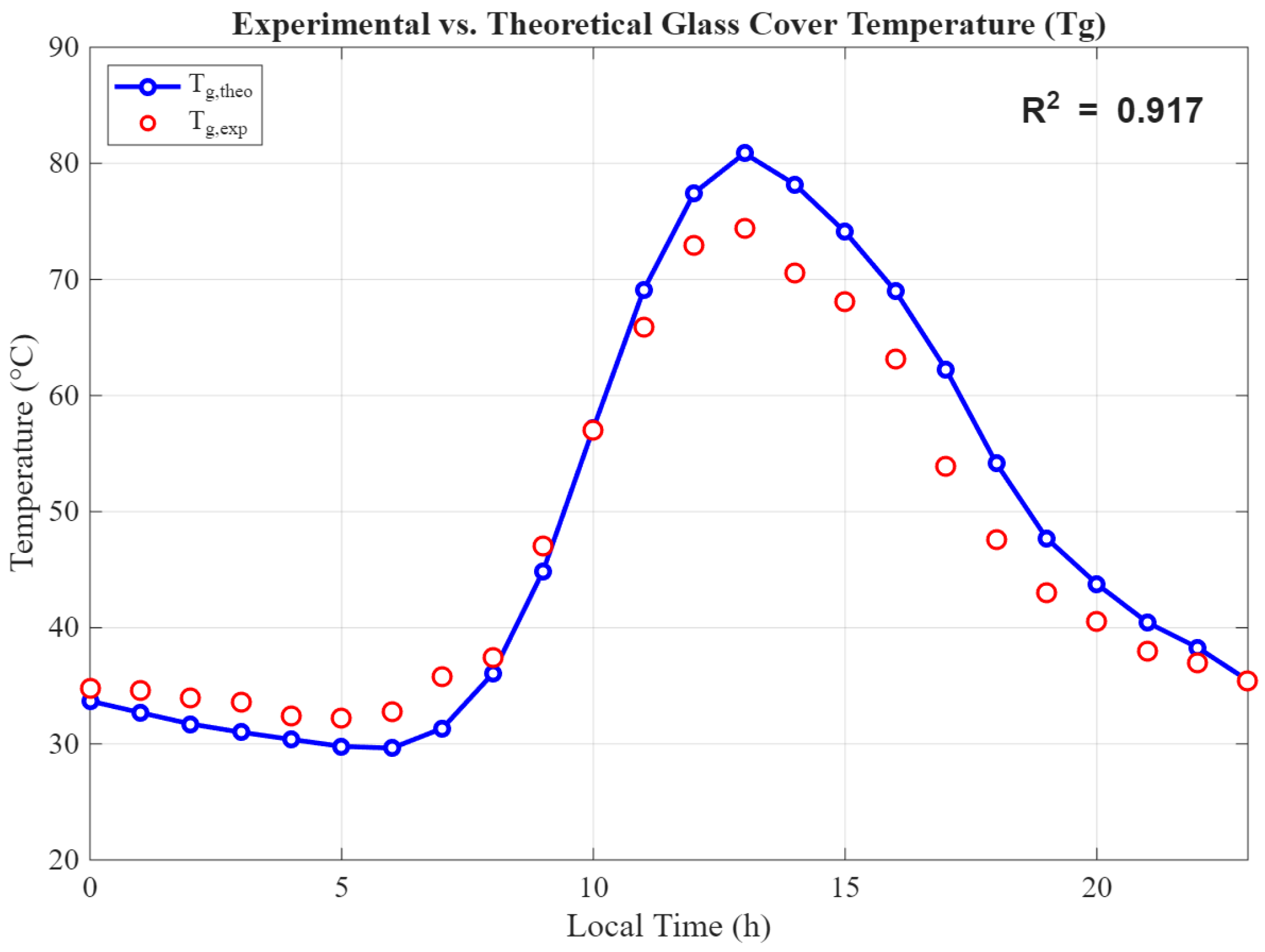

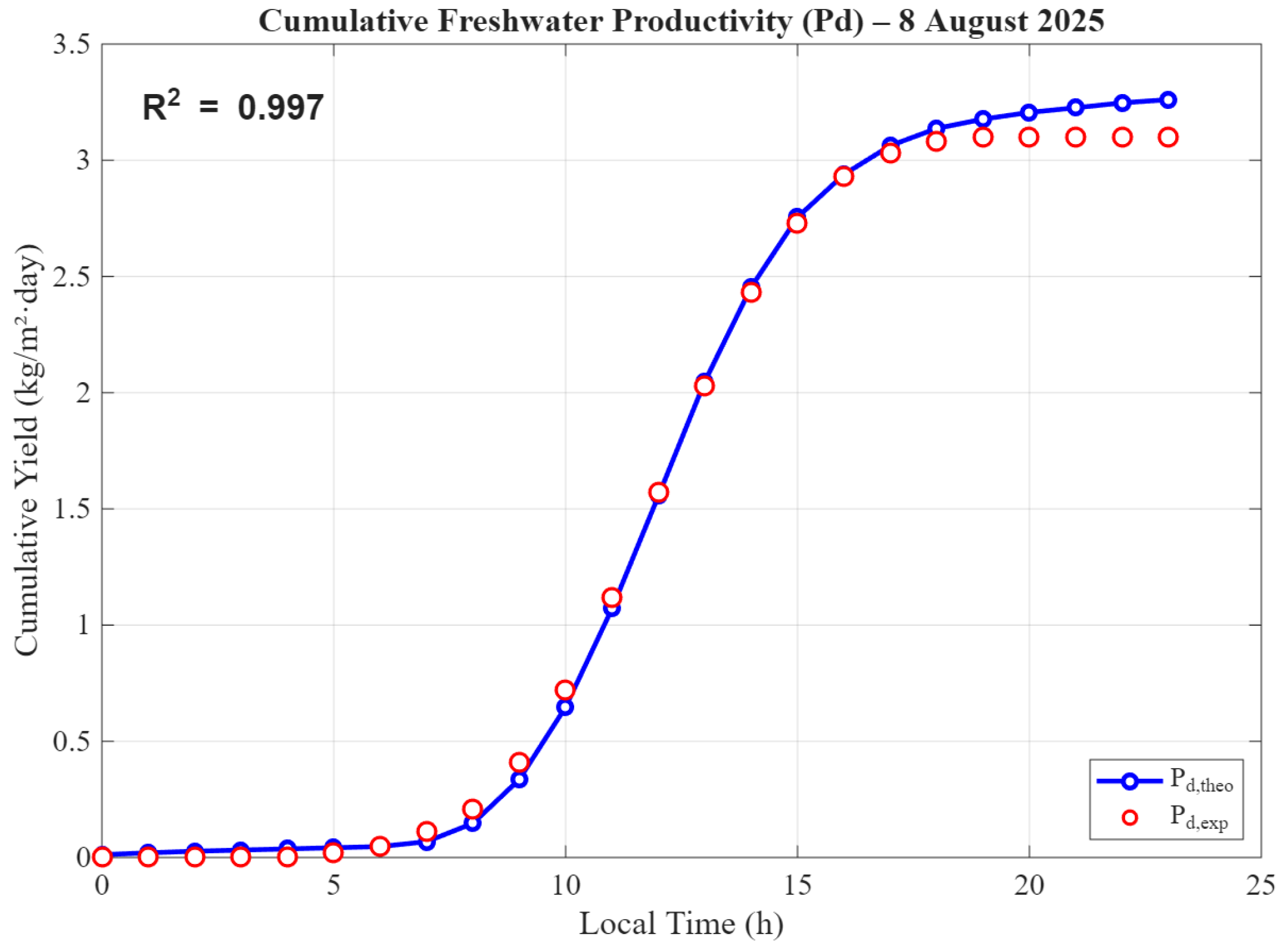

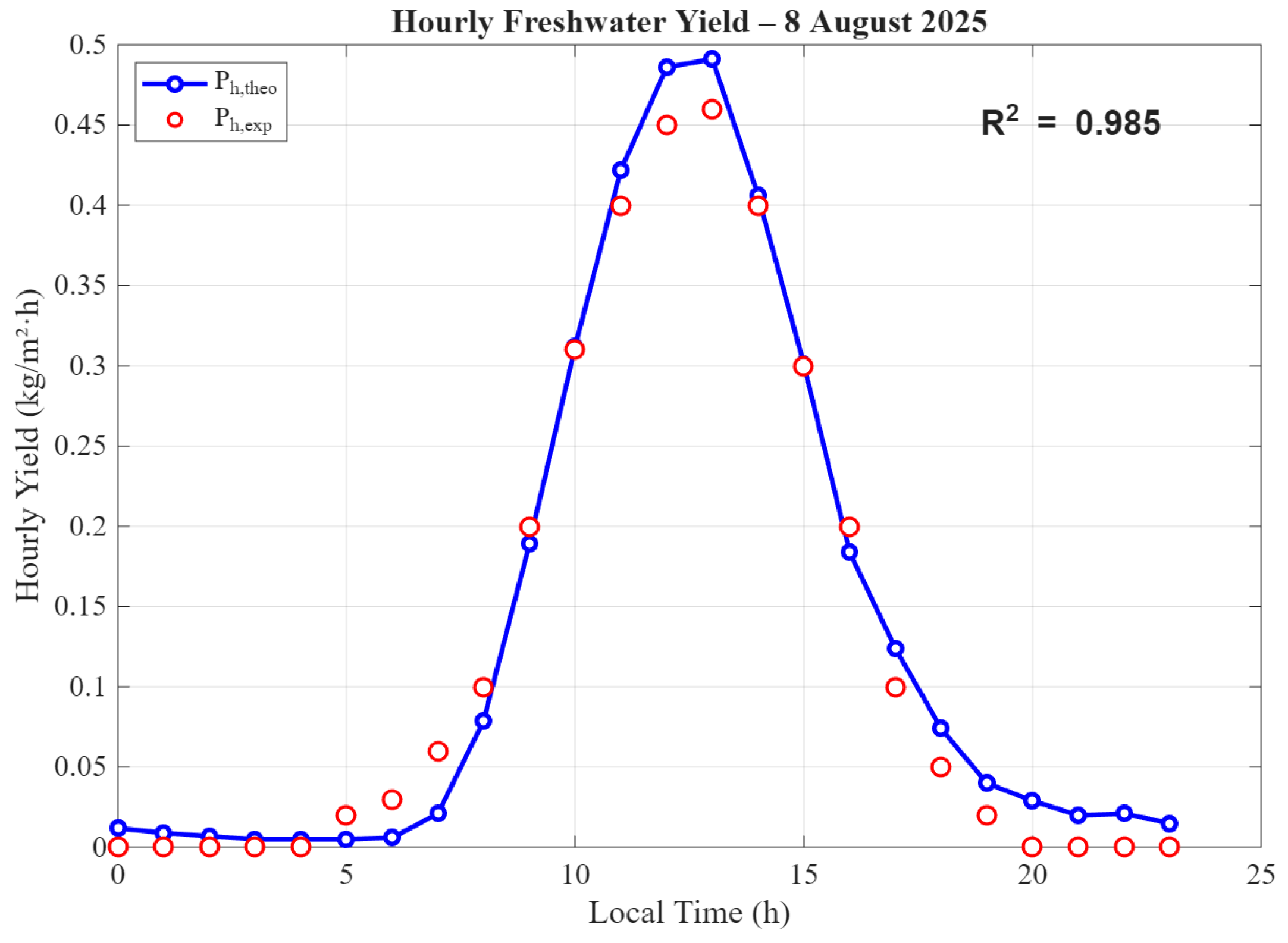

The comparison between model predictions and measurements for basin water, basin liner, and glass-cover temperatures (, , and ) showed coefficients of determination of approximately R2 = 0.90–0.94, with root mean square errors around 4–5 °C. For freshwater production, the model reproduced both cumulative and hourly yields with high accuracy, achieving RMSE values of 0.07 L/m2·day and 0.02 L/m2·h, and and , respectively. When the analysis was restricted to the main operating period of the still, the mean absolute percentage error for cumulative and hourly productivity decreased to single-digit or low double-digit values, indicating that the proposed model captures the dominant behavior of the system during its effective working hours.

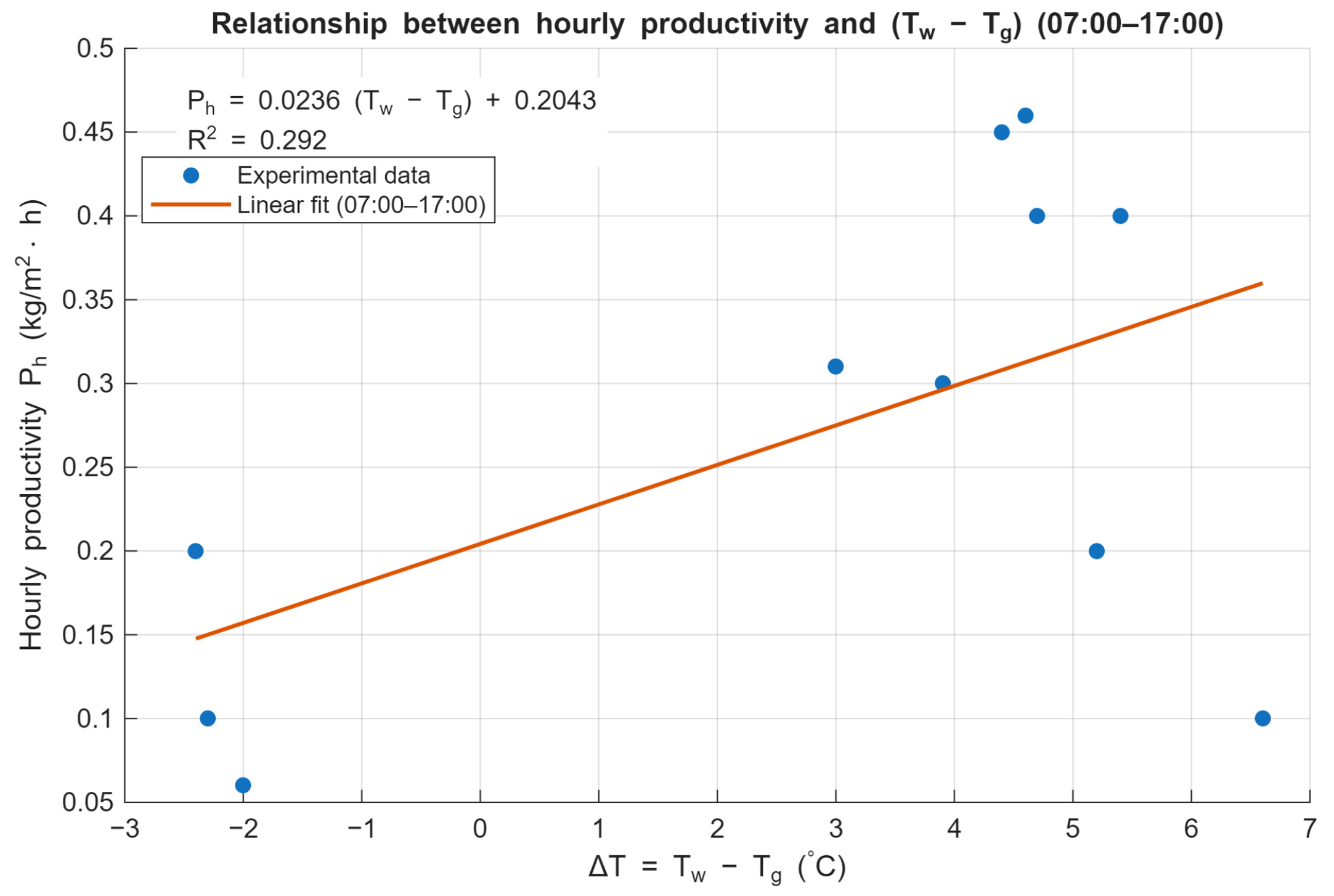

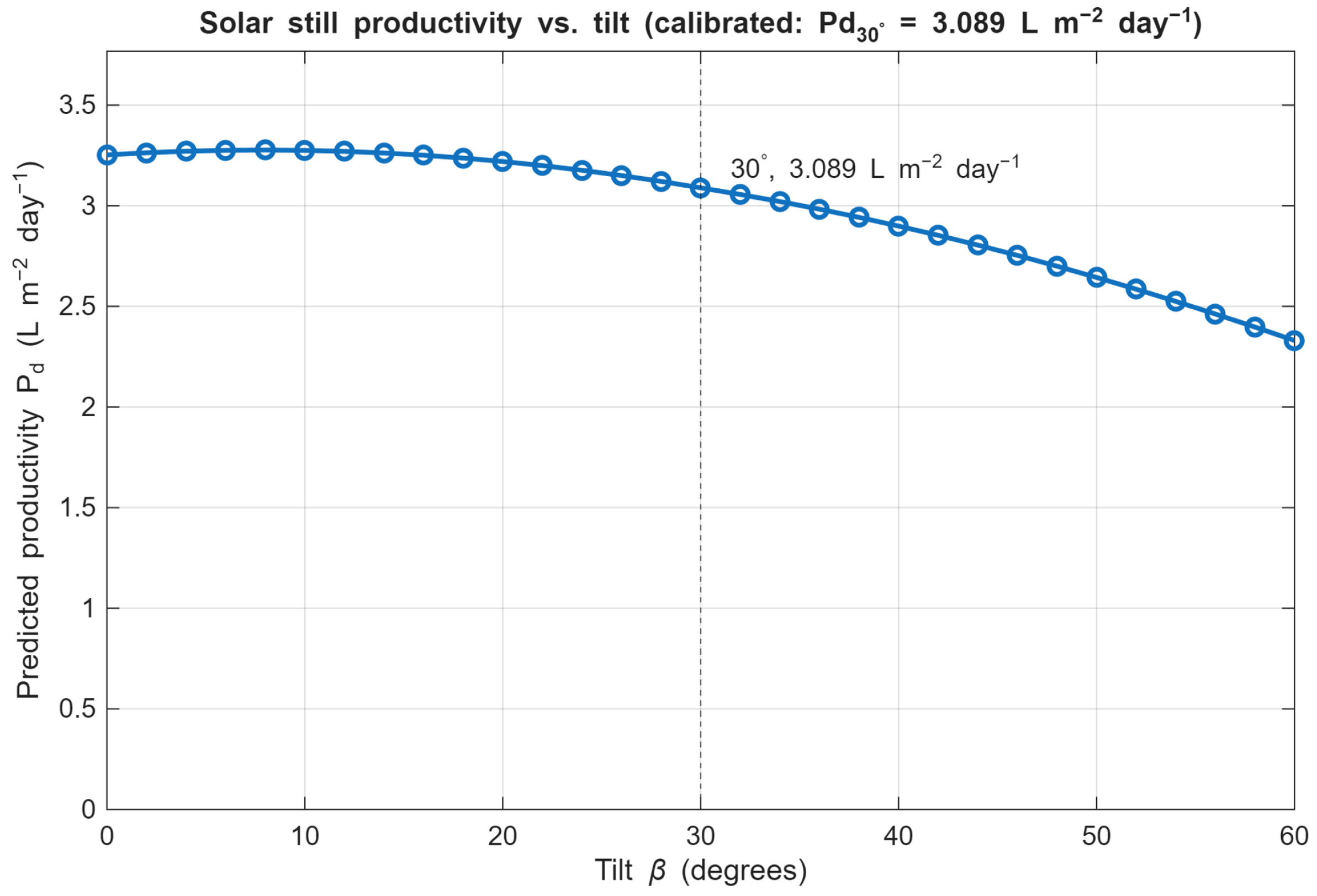

Under the local climatic conditions, the still produced 3.1–3.5 L/m2 of distilled water per day, with a peak hourly yield of about 0.46 L/m2·h. These values are associated with the combination of high solar irradiance (exceeding 1200 W/m2 at midday), elevated ambient temperatures (up to 48 °C), and very low relative humidity (below 25 %), which together promote strong evaporation and condensation. The daily thermal efficiency was found to be 26.90% experimentally and 28.20% from the model, with hourly efficiency peaking near solar noon. A clear linear relationship between distillate yield and the temperature difference confirmed the importance of maintaining a sufficient thermal driving force between the basin water and glass cover. The chosen glass inclination of 30°, close to the latitude of Basrah, was also shown to be suitable for enhancing incident solar radiation and effective condensate collection.

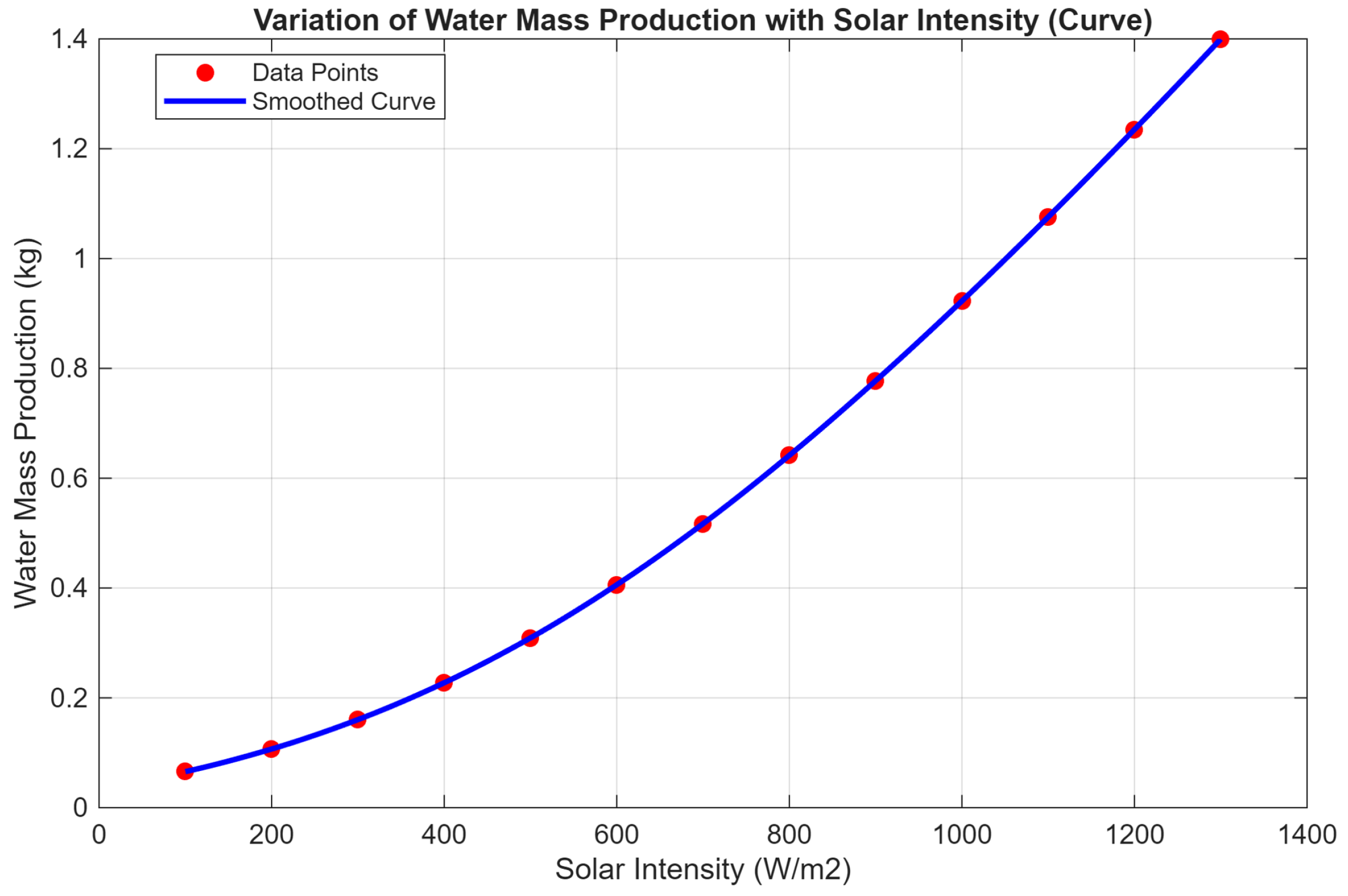

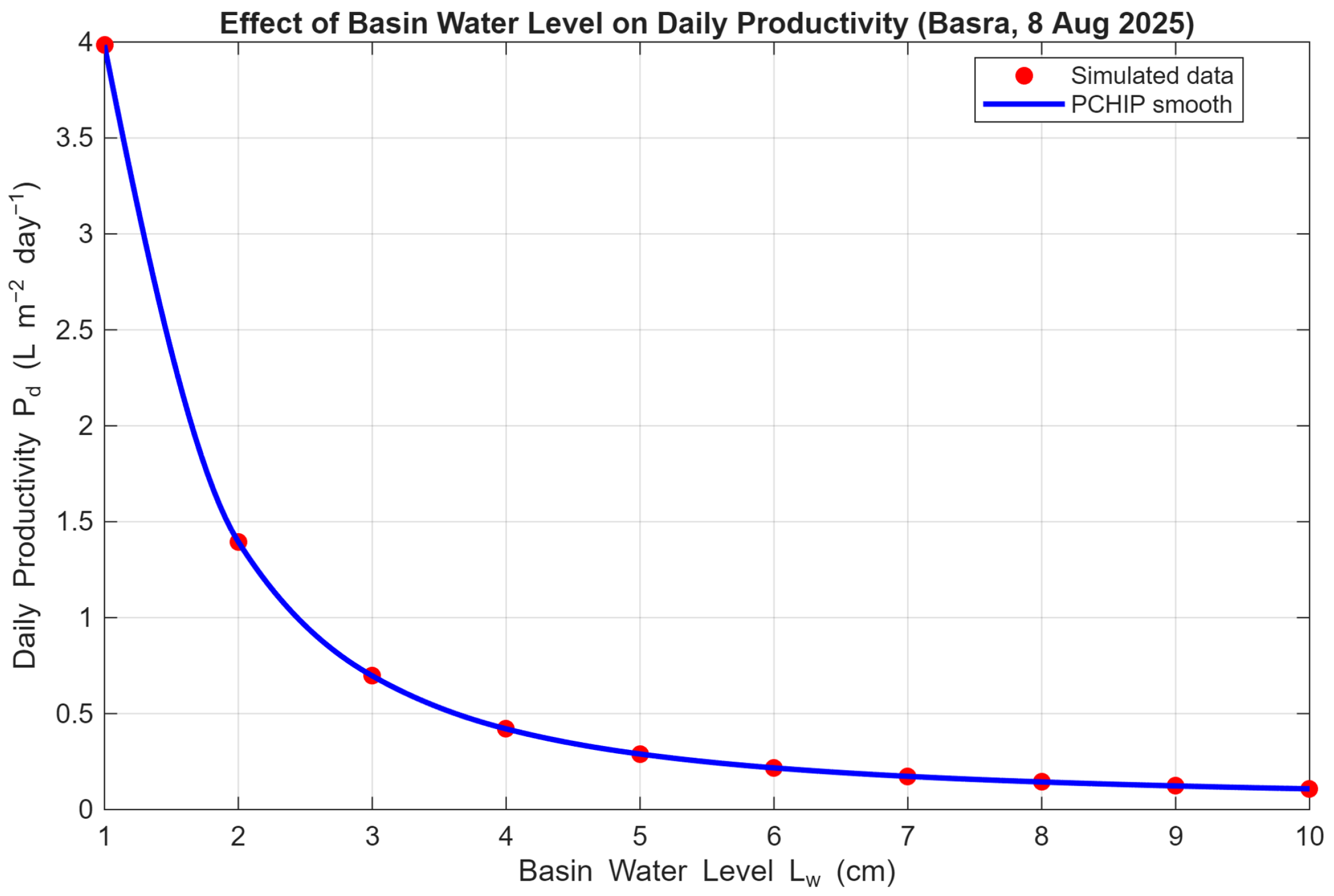

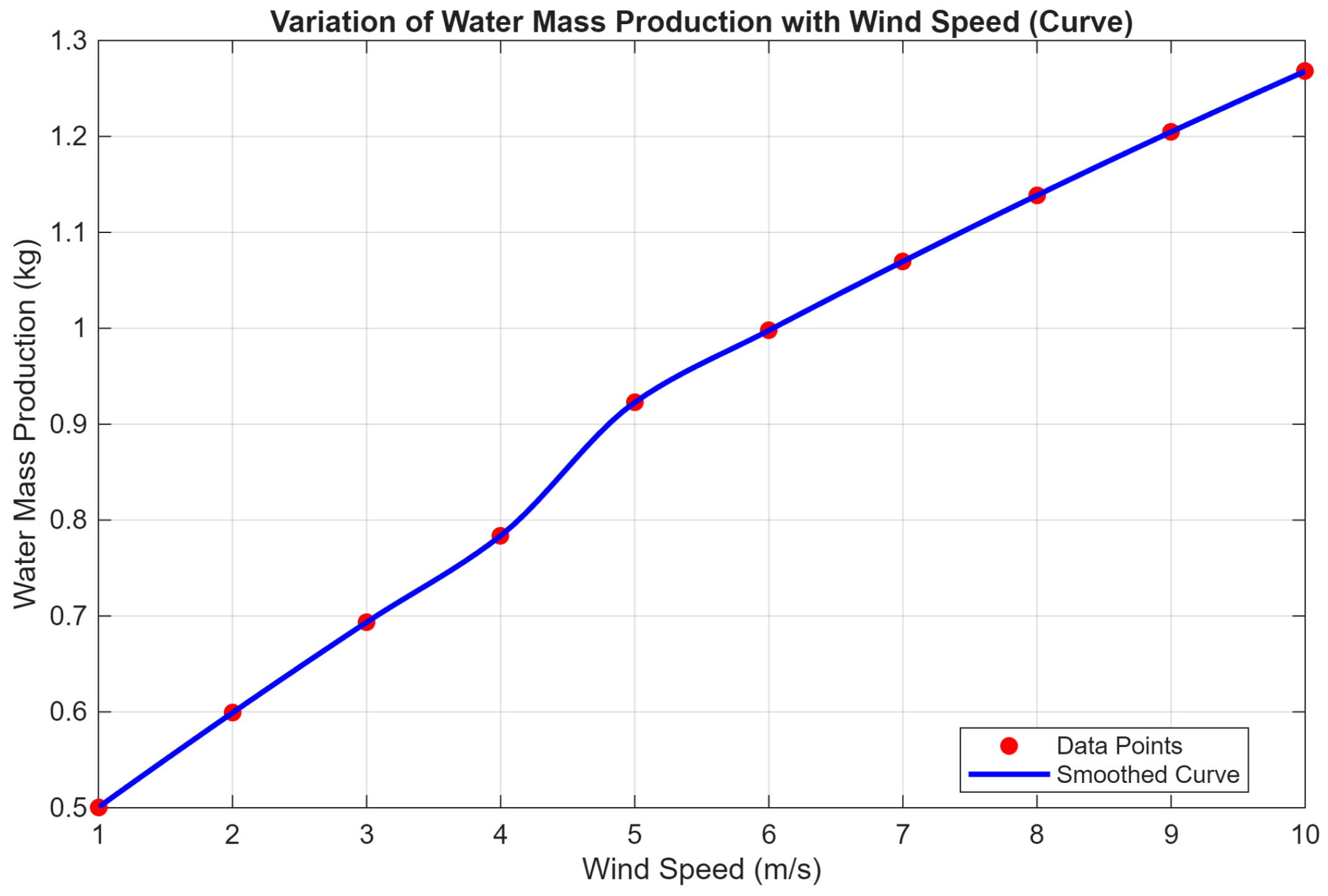

A parametric study demonstrated that solar radiation intensity is the most influential factor governing productivity, followed by basin water depth, glass cover tilt angle, and wind speed. The best performance occurred for shallow water depths (less than 3 cm) and tilt angles close to the local latitude, in line with design recommendations reported in the literature. Overall, the results indicate that simple, conventional basin stills, when properly designed and tuned to local conditions, remain a practical and low-cost option for decentralized freshwater production in hot, arid regions. The validated model can be used as a design and optimization tool for similar climates beyond southern Iraq.

At the same time, the study has several limitations that should be recognized. The experimental campaign was carried out on clear sky days during peak summer, so the influence of cloudy periods, dust events, or other seasons was not examined. Long-term effects, such as salt accumulation, which are important for real deployments, were not assessed over extended operation. In addition, the thermal properties of the insulation and structural elements were treated as constant, whereas they may change with temperature, aging, and moisture content. These simplifications are reasonable for establishing a controlled benchmark but should be relaxed in subsequent work aimed at long-term field performance.

The thermal conductivity of the bottom insulation was assumed constant in the numerical model, based on nominal manufacturer data at 25 °C. However, insulation materials generally exhibit temperature-dependent behavior, and their thermal resistance may decrease at elevated temperatures. While sensitivity analysis suggested a limited impact on total productivity under the present operating conditions, this simplification may introduce modeling error in systems operating at higher base temperatures or using alternative insulation types.

Building on the results obtained, several directions for future research emerge. One promising avenue is the development of hybrid configurations that incorporate phase change materials, nanofluids, or thermoelectric elements to increase energy utilization while retaining the simplicity of the basic basin design. Multi-stage or cascading arrangements that reuse latent heat or recover vapor in successive stages could raise total freshwater output without proportionally enlarging the footprint. Another opportunity lies in adaptive or smart designs, such as seasonally adjustable cover tilt, variable water depth control, or simple tracking mechanisms, to improve performance across different seasons and locations.

Further studies should also address long-term operation using real feedwater, with particular attention to water quality, scaling, and fouling processes, as well as cleaning and maintenance requirements. Finally, to support large-scale dissemination, detailed techno-economic analyses are needed, including life cycle costs, payback period, and sensitivity to local prices and climate. In summary, this study provides a rigorously validated reference case for a conventional solar still under extreme arid conditions and offers a basis for future design, optimization, and deployment of low-cost desalination technologies in water-stressed regions.