1. Introduction

In recent years, as urbanisation accelerates, a new form of global urbanisation called “megacity regions” has emerged, characterised by interconnected cities experiencing land use and cover change (LUCC) beyond traditional administrative boundaries [

1,

2]. Despite many countries acknowledging the competitive advantages of megacity regions in the global urban system, these regions often face spatial governance challenges due to institutional fragmentation [

3]. Given that land serves as a fundamental carrier of human activities and urban development, through formal integration policies coordinating regional LUCC is regarded as an effective approach to governing the spatial structure of megacity regions [

4]. Building on this, existing studies have emphasised the pivotal role of formal integration policies in shaping megacity region spatial structures by coordinating regional LUCC [

5,

6]. Specifically, the formal integration policies would involve establishing clear guidelines and procedures when integrating data and models related to LUCC into decision-making processes, aiming to promote spatial structures of the megacity region that are coordinated and integrated [

1,

2]. However, despite the growing recognition of megacity regions as spaces of cross-boundary urbanisation, promoting land development in border-adjacent areas is recognised as a core objective of metropolitan spatial integration, and the driving forces of LUCC across administrative boundaries remain underexplored, particularly before the implementation of top-down formal regional integration policies. Measuring the evolutionary phase preceding formal integration is essential for accurately understanding the bottom-up mechanisms and actual growth trajectories of megacity regions, which help support more efficient resource allocation and enhance the effectiveness of policy interventions [

3].

The expansion of a built-up area (BUA) represents the most typical LUCC form in megacity regions [

1,

2]. LUCC research aims to explore changes in the Earth’s surface caused by natural processes and human activities. It is an important agenda item in the 2030 United Nations Sustainable Development Goals [

7,

8]. Since the rise of megacities in the 1960s–1970s, LUCC studies have increasingly focused on urban areas, where the rapid expansion of built-up land presents significant sustainability challenges [

9]. LUCC research provides a quantitative approach and comprehensive global datasets for tracing the development of urban spatial evolution [

10,

11]. This approach is particularly advantageous for analysing the spatial evolution and integration processes within megacity regions, especially in contexts where formal regional integration frameworks are absent [

4].

In China, formal regional integration policies are implemented in a top-down approach under the supervision of the central government [

3]. The GBA, designated as a megacity region in China, comprising eleven cities [nine mainland cities and two special administrative regions (Hong Kong and Macau)], since 2018 has undergone rapid integration and development. State-led formal integration policies have achieved notable success in promoting cross-border urbanisation and spatial integration in the Guangdong–Hong Kong–Macao Greater Bay Area (GBA) by coordinating LUCC, thereby optimising regional spatial structures and enhancing the coordination of urban functional divisions [

6]. Today, the GBA is recognised as the fourth-largest megacity region globally, following New York, San Francisco, and Tokyo Bay Areas.

The success of spatial coordination of the Greater Bay Area (GBA) was not achieved instantaneously. Prior to the centralised coordination and integration stage, the GBA underwent a fragmentation phase of evolution driven predominantly by local governments and market forces. During this period, municipal governments enjoyed substantial autonomy in economic governance [

12]. The fiscal decentralisation reforms of the 1990s incentivised local authorities to adopt entrepreneurial strategies, accelerating land development and attracting investment through competitive infrastructure expansion. Particularly noteworthy was the land-mark land reform of 1990, which for the first time authorised local governments in mainland China to transfer state-owned urban land through market mechanisms. This significantly boosted demand for urban built-up land, driving rapid built-up area expansion throughout the GBA [

12]. However, this model also intensified spatial and regulatory fragmentation, as municipal governments prioritised local interests over regional coordination [

10,

12,

13]. Furthermore, under the “one country, two systems” framework, the GBA faced additional complexities due to cross-border governance challenges. Given the dynamic adjustments to governance frameworks experienced during its spatial formation, the GBA provides a critical empirical case study for researching how LUCC affects the spatial structure of megacity regions in the absence of state-led integration policy.

Thus, this paper aims to provide a comprehensive understanding of the drivers of LUCC across boundaries within megacity regions, prior to the implementation of formal integration policies, by addressing two pivotal questions: (1) What are the spatial and temporal characteristics of LUCC in the GBA during the pre-integration period from 1990 to 2018? (2) What are the driving factors behind LUCC in the GBA during this period, and how did they influence these changes?

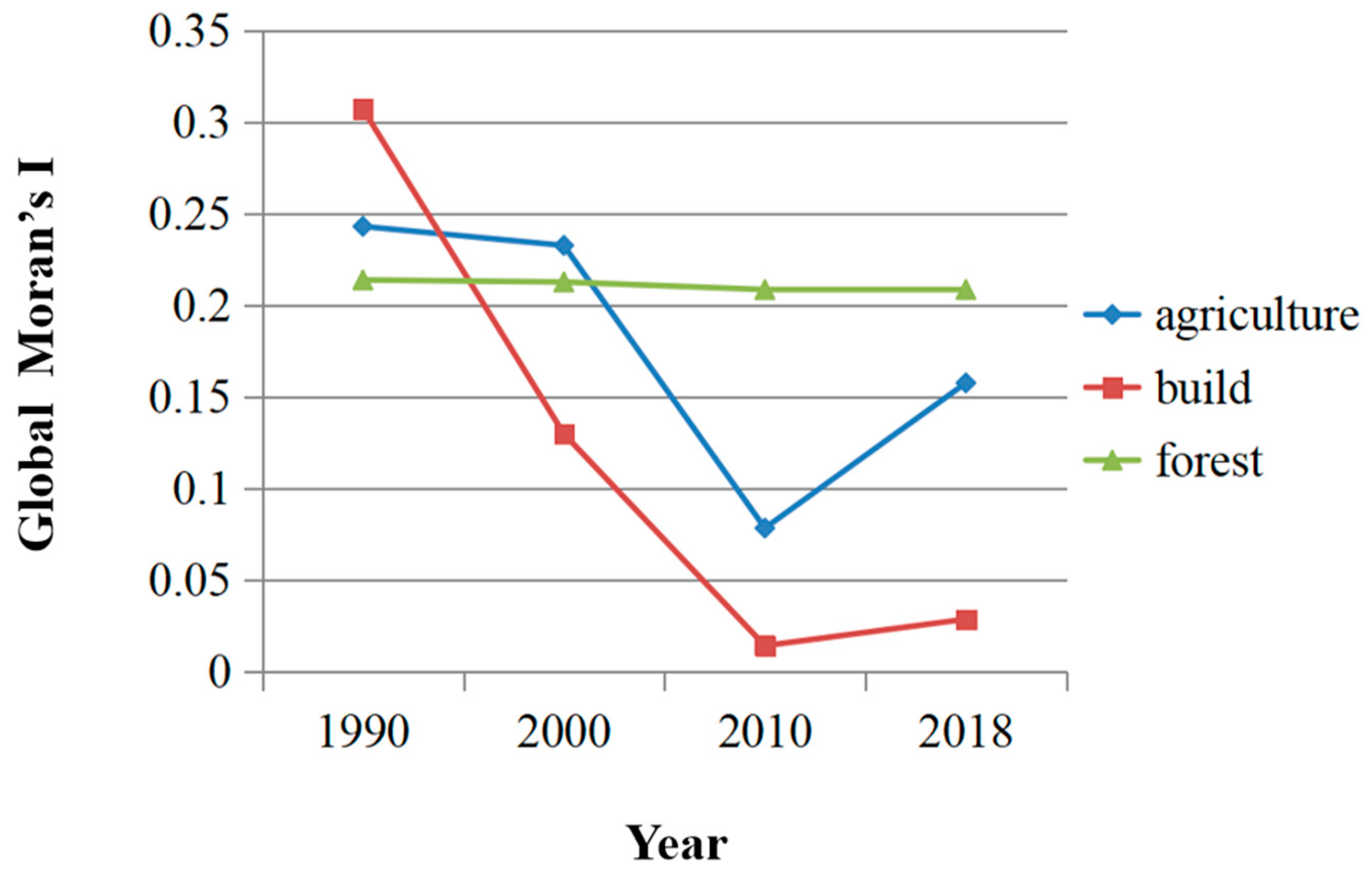

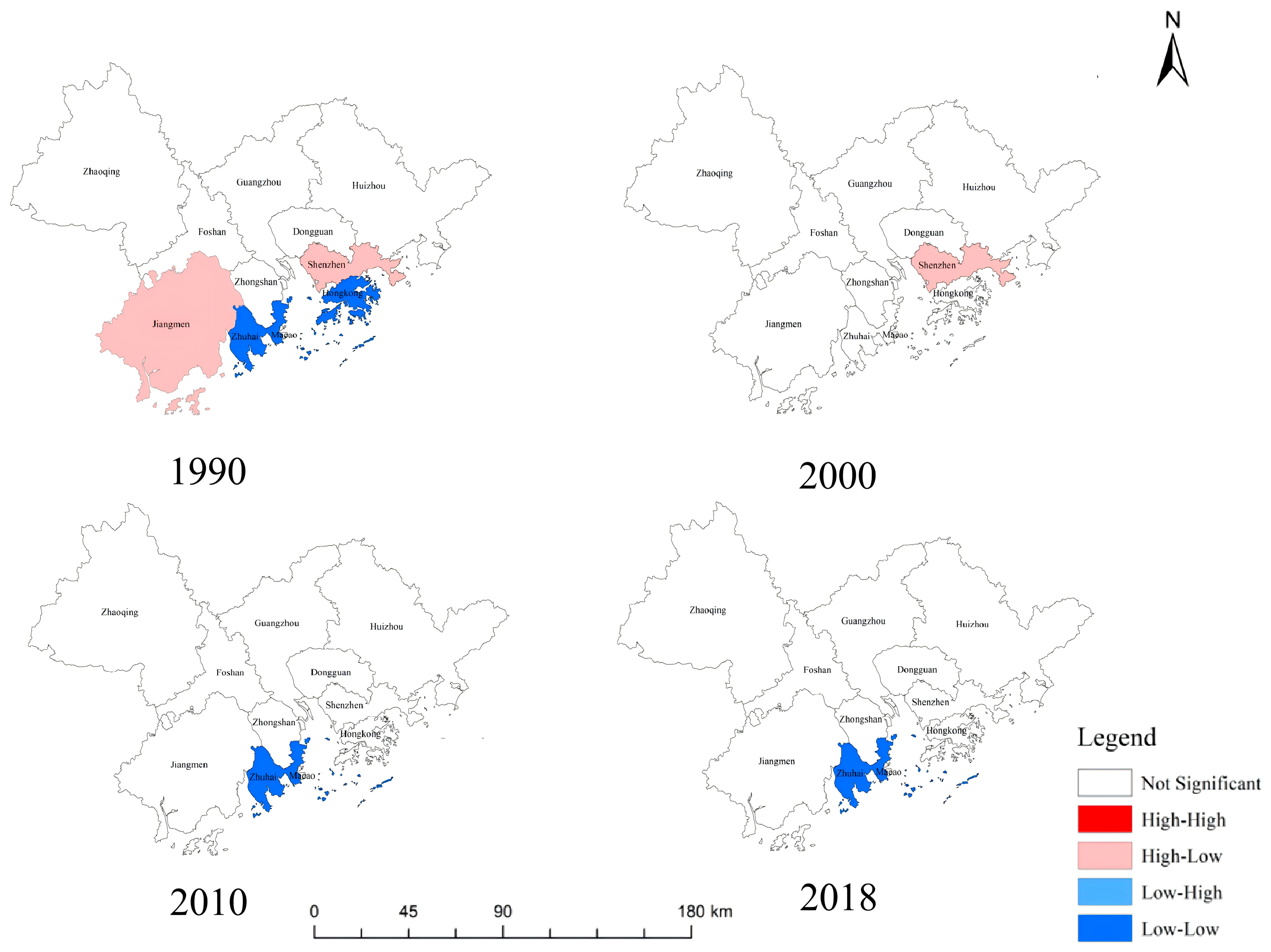

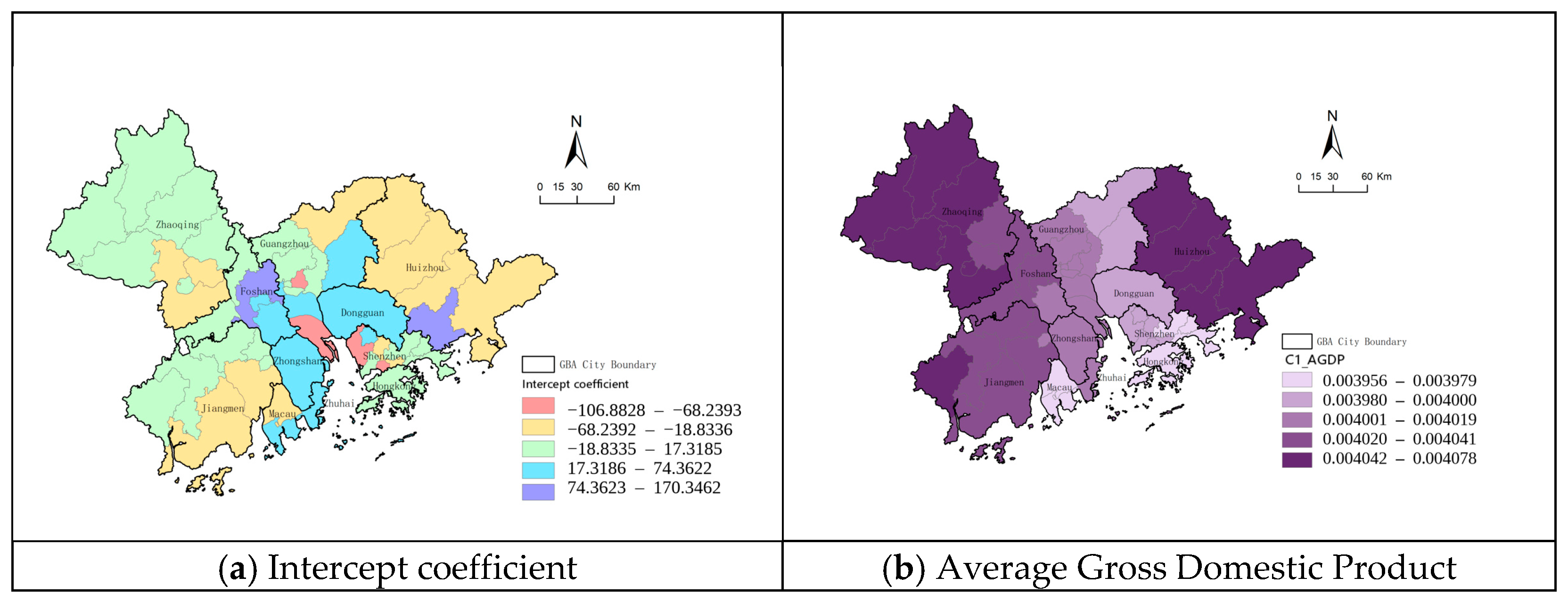

To answer these questions, this study concentrates on the expansion of a BUA, a primary and most conspicuous form of LUCC in the GBA. This study initially applies Mo-ran’s Index, based on multiple big data sources, to explore the spatial–temporal distribution characteristics of LUCC in the GBA before the implementation of formal integration policies. Subsequently, the Geographically Weighted Regression (GWR) model is used to identify key factors driving BUA expansion and their influence in terms of extent and direction, which varies across different areas in the GBA. This study provides a rare empirical perspective on the formation of megacity regions’ spatial structures, which are shaped by LUCC in the absence of state-led formal integration frameworks. It offers valuable insights not only for understanding megacity regions globally but also imparts critical experience from China’s Greater Bay Area for managing cross-border and cross-administrative urban expansion worldwide.

6. Discussion

There have been significant changes in land use and cover in the GBA from 1990 to 2018. Guangzhou, Shenzhen, Foshan, and Dongguan experienced the most remarkable urban expansion from 1990 to 2018, with average annual growth rates of 44.23 km2, 22.64 km2, 40.96 km2, and 35.37 km2, respectively. Meanwhile, Hong Kong and Macau experienced the slightest change in the same framework, with an average annual expansion of 3.44 and 0.21 km2, respectively. Notably, LUCC in the GBA exhibited a distinctive cross-border, spatially networked expansion pattern even before the formal regional integration policies were introduced, extending BUA growth beyond core cities into decentralised urban nodes. Specifically, two prominent cross-border urban cores and one cross-administrative core emerged: one connecting Shenzhen and Hong Kong, and another linking Zhuhai and Macau. Moreover, an extensive cross-administrative connection developed between Guangzhou and Foshan.

The emergence of these three cores can be better understood by tracing their historical and institutional foundations. The Shenzhen–Hong Kong core reflects the long-standing integration between export-processing manufacturing in Shenzhen and finance, logistics, and producer services in Hong Kong, reinforced by intensive cross-border commuting and successive waves of land development along major transport corridors such as highways, ports and, more recently, metro lines [

53]. The Zhuhai–Macao core has been driven by Macao’s tourism and gaming industries, the strategic development of the western bank of the Pearl River estuary, and port and infrastructure projects that facilitate the cross-border movement of visitors and workers [

18]. The Guangzhou–Foshan core builds on decades of manufacturing specialisation in both cities, the gradual blurring of administrative boundaries, and the construction of an integrated transport network (metro lines and intercity rail) that has encouraged contiguous urban expansion [

20,

36]. Together, these processes have left a clear imprint on LUCC patterns in the form of cross-boundary BUA clusters, which are further reflected in the spatial configuration of the GWR coefficients.

On the other hand, although there is a clear trend towards integrated development, our study indicates that GBA urban expansion exhibits significant spatial imbalance issues. The local Moran’s index result reveals the existence of a high–low agglomeration phenomenon in land use and cover within the GBA. It is evident that the challenges related to urban spatial expansion in the GBA mainly stem from an uncoordinated scale of urban space and the uneven spatial development among urban clusters. For example, certain adjacent cities such as Zhuhai and Zhongshan exhibited limited spatially interconnected urban expansion despite their geographical proximity. Meanwhile, peripheral cities such as Jiangmen and Zhaoqing exhibited minimal to no spatial integration with other GBA cities, reflecting broader regional disparities and fragmented urban networks.

In addition, historically, western countries occupied Hong Kong and Macau, which led to an advanced technology, economy and well-established land market in these regions prior to the 1990s. However, for mainland cities, China’s critical land reform was initiated in 1990, which first allowed market-based urban land transfers in mainland cities. Economic growth and population increase generated a demand for additional land, while substantial investments in real estate and infrastructure facilitated the expansion of urban construction. However, following 1990, natural resource limitations significantly curtailed further growth of BUA in both Hong Kong and Macau. Macau’s geographical constraints, which are surrounded by water with a total area of less than 40 square kilometres, leave minimal room for expansion. In contrast, Hong Kong’s hilly terrain allows only 15% of the overall area to be developed as flat land. Furthermore, approximately 85% of its territory is unsuited for either urban construction or agricultural purposes. Additionally, stringent polices regulating land use/cover exacerbate this issue [

54]. Consequently, Hong Kong experiences the lowest average growth rate of BUA.

The analysis is terminated in 2018, a year that both witnessed the GBA’s formal endorsement and marked a structural policy breakpoint. In that year, the Ministry of Natural Resources introduced the national territorial–space control regime and the “three control lines” (ecological conservation redline, permanent basic farmland, and the urban development boundary), substantially tightening market- and locally led expansion and conversion of construction land. Accordingly, 1990–2018 can be delineated as a “market/land-concession–driven phase,” with the post-2018 period entering a “policy-constrained phase,” while the possibility of transitional bias and lagged effects is acknowledged. More broadly, this breakpoint signals a shift in the megacity-region context from a singular emphasis on urban growth to a triple-constraint paradigm—balancing growth, ecological sustainability, and food security.

The results of this research indicate that socio-economic factors, such as population, GDP, and real-estate investment, as well as natural factors, including road density and water area, have significant impacts on the growth of the BUA in various regions in the GBA over the period from 1990 to 2018. The signs of their coefficients are generally consistent with our expectations, which align with the findings of other related studies. At a broader regional scale, however, pronounced spatial heterogeneity emerges due to differences in development stage, path-dependent historical trajectories, and environmental regulation and planning regimes.

Numerous studies highlight the importance of population and GDP in urban expansion [

26]. Population growth and economic development are the internal drivers of urban development. The positive influence of population on BUA expansion is attributed to the heightened demand for urban land resulting from an increase in urban population. The analysis of the spatial distribution of GWR model coefficients reveals that both population and economic factors positively contribute to changes in the BUA. However, the degree of impact varies across different regions. Specifically, central cities in Guangdong, such as Hong Kong and Macao, experience a lesser impact compared to suburban areas. This discrepancy arises because Hong Kong and Macao are at different stages of urbanisation relative to mainland cities [

55]. According to the three-stage theory of urbanisation development [

11], a large number of infrastructure and supporting service facilities are required due to economic growth and population increases, particularly within the secondary and tertiary industries during the early phases of urbanisation. Consequently, this need promotes an increase in per capita BUA. Hong Kong and Macao have transitioned into later stages of urbanisation earlier than other cities within the GBA, which have undergone initial through medium-term stages since 1990. This is characterised by accelerated developmental phases in their respective processes of urbanisation. As a result, these nine cities maintain a higher rate of expansion regarding BUA compared to Hong Kong and Macao.

According to previous studies, land management and pricing have a significant impact on the expansion of urban land for construction in developing countries such as China [

56]. This is mainly attributed to the substantial real-estate investment that contributes to an increase in BUA, such as the corresponding infrastructure [

12,

27,

43]. However, this study finds that spatial differences regarding the influence of real estate investment on changes in BUA within the GBA. In cities in the early stages of urban development, characterised by low urbanisation rates and relatively low land prices, real estate investment has a significantly increasing effect on the growth of the BUA. For instance, in 2018, the average land price was RMB 7000 per square meter in Zhaoqing, RMB 9000 in Jiangmen, and RMB 13,000 in Foshan. Conversely, the areas with high urbanisation rates and elevated land prices have experienced restrained expansion of per capita BUA due to rising costs related to both increased property values and real-estate investments. These include Hong Kong at RMB 140,000 per square meter, Shenzhen at RMB 60,000, Macao at RMB 80,000, and Guangzhou at RMB 40,000. This phenomenon aligns with the principle of diminishing returns on land use. From a developer’s perspective, higher land costs diminish profit margins for real estate developments, preferring higher density development strategies instead of investing in large areas of land. Consequently, this indicates that real-estate market development within the GBA is unevenly distributed, with more significant investments and faster expansions occurring in regions where both urbanisation levels and land prices are comparatively lower.

Both water area and transport factors significantly affect the changes in BUA, particularly regarding natural factors. Previous studies have found that marine rivers provide abundant natural resources for urban development, thereby promoting BUA expansion. However, these bodies of water may also pose a flood risk that negatively affects such expansions. The result of the GWR model reveals that the impact on the BUA varies between −0.02 and 0.7. Although there is spatial variation in the correlation between watershed area and BUA within the GBA, most coastal cities show a positive correlation. This finding is consistent with the study by Hui and Li [

2], which highlights how the advantageous location of the Bay Area and its economic relationship with maritime environments promote land expansion in coastal regions. Given the limited availability of land for outward growth, Shenzhen’s proximity to the sea has led to an urban spatial expansion characterised by a tendency to spread towards marine areas. In addition, reclamation has emerged as a significant method for acquiring land in Hong Kong and Macao, where sea areas constitute 31.80% and 78.07% of total expansion areas in well-developed regions, respectively. These figures show considerably higher than those observed in other cities seeking to supply additional BUA, which creates a conflict between urban development and marine conservation.

The findings of this study demonstrate that the impacts of transport factors on the changes of the BUA across different areas are significant [

57]. The signs of their coefficients are generally consistent with the expectations based on the related literature. While previous studies show that transportation development is a key driving force for spatial urban expansion, which plays a directional role in shaping spatial urban forms [

18,

58], the results of this study challenge this assumption in the context of highly urbanised regions. This implies that by 2018, the Greater Bay Area’s fundamental core road network had already been established. Under these conditions, further increases in road density tend to support intensification and redevelopment (higher density, vertical expansion, land-use conversion) rather than horizontal expansion. This finding is consistent with historical patterns. This means in highly urbanised areas, a denser road network is generally associated with improved transport efficiency, better accessibility, and more intensive land use, reducing the demand for additional BUA. Therefore, for the Greater Bay Area megacity regions, intra-regional infrastructure connectivity should be encouraged, particularly along transportation corridors and at the peripheries of cities. At the same time, stronger central government coordination is needed to address inefficiencies arising from intercity competition and bargaining over infrastructure projects [

18]. This is particularly relevant for large-scale transportation initiatives that extend beyond administrative boundaries, such as the Hong Kong-Zhuhai-Macao Bridge and the Shenzhen–Zhuhai Corridor, where conflicting local interests often lead to delays, cost overruns, and fragmented regional development.

Overall, from a broader regional perspective, the findings of the GWR coefficient reveal that spatial variations exist in the expansion of floor area across different regions within the Greater Bay Area, driven by distinct factors. This can be explained by differences in development stages, land prices, and local policy frameworks. From 1990 to 2018, core cities such as Guangzhou, Shenzhen, Hong Kong, and Macao entered a phase of mature or late-stage urbanisation, characterised by exceptionally high land prices and stringent planning controls. Within these cities, new population inflows and investment were more readily absorbed through redevelopment and vertical intensification, imposing structural constraints on further outward expansion of building floor area (BFA). By contrast, peripheral and suburban cities such as Jiangmen, Zhaoqing, and Huizhou retain substantial undeveloped land reserves and comparatively lower land prices. In these areas, population growth and property investment more directly translate into extensive BUA expansion. This contrast helps explain why property investment exhibits negative coefficients in some high-cost core cities yet positive coefficients in low-cost peripheral cities, and why identical drivers exert differing impacts on BUA expansion across distinct regions of the Greater Bay Area.

Beyond their implications for spatial structure, the observed LUCC patterns raise important sustainability concerns. The expansion of BUA has fragmented agricultural and forest land across the GBA, with potential consequences for regional food security, biodiversity conservation, and carbon storage. These pressures are compounded along the coast, where land reclamation in cities such as Hong Kong, Macao, and Shenzhen has converted coastal wetlands and mudflats, increasing exposure to flooding and storm surges under conditions of sea-level rise and more frequent extreme weather events. Addressing these risks requires stronger forms of cross-jurisdictional spatial governance. In practical terms, this implies coordinated basic farmland protection and the designation of inter-city ecological corridors, stricter regulation of and ecological compensation for coastal reclamation, and the integration of LUCC indicators into the performance evaluation of GBA regional integration. Embedding such spatial-governance measures into the formal planning framework would help align regional economic ambitions with long-term ecological resilience.

7. Conclusions

This study examines LUCC in the Guangdong–Hong Kong–Macao Greater Bay Area (GBA) from 1990 to 2018, uncovering the spatial integration patterns preceding state-led formal institutional frameworks. The findings highlight two key aspects. First, even before the formal establishment of the GBA as a national strategic framework in 2018, the BUA in the region already exhibited cross-border spatial expansion, transcending administrative boundaries. Two prominent cross-border joint cores have formed (Shenzhen and Hong Kong; Zhuhai and Macau), along with one cross-administrative core (Guangzhou and Foshan). This was primarily driven by market forces and local government initiatives, rather than top-down policy directives. At the same time, the expansion of the BUA was not confined to core cities like Guangzhou and Shenzhen but also extended into decentralised urban nodes along transportation corridors, fostering a polycentric spatial network. This pattern was particularly evident in cities such as Dongguan, Foshan, and Zhuhai, where urbanisation spread across municipal borders, indicating an emerging functional integration of the megacity region even before policy formalisation. Second, despite the emergence of a cross-border urban network, the absence of a formal integration framework led to spatial imbalances and uncoordinated development patterns. Urban construction expansion varied considerably across cities, with rapid growth in mainland cities contrasting starkly with limited expansion in Hong Kong and Macao due to land constraints and governance differences. Moreover, uneven development intensified the fragmentation of agricultural and forest lands, alongside growing environmental pressures from coastal land reclamation. The impact of key driving factors—such as GDP growth, population increase, real estate investment, proximity to water, and road infrastructure development—varied significantly across different parts of the region, further exacerbating these spatial disparities.

The findings of this study have significant implications for regional planning and policymaking at both the national and regional levels. First, in the GBA case study, the observed BUA expansion in the GBA already exhibited a cross-border, spatially networked expansion pattern before formal regional integration policies. Thus, the definition and planning of megacity regions should recognise and leverage existing patterns of spatial and economic integration as indicated by LUCC, rather than solely relying on administrative boundaries. Second, these findings suggest that future land-use planning in the GBA requires coordinated cross-border spatial strategies, emphasising ecological protection, housing and industrial policies, and infrastructure and real estate investment. Ecological strategies should establish joint ecological corridors, protect green belts, and coordinate coastal land-use controls to mitigate fragmentation and reclamation pressures, safeguarding environmental sustainability. Housing and industrial land policies must optimise regional land-use efficiency, promoting cross-city housing initiatives and transport-oriented development to balance population density and alleviate socio-economic inequalities. Finally, infrastructure and real-estate investments demand a unified regional approach, harmonising spatial planning and land policies across jurisdictions to prevent speculative and fragmented development, thereby facilitating interconnected and sustainable regional growth. Overall, the findings motivate an actionable governance checklist: systematic planning of cross-jurisdiction ecological corridors, rigid protection of permanent basic farmland, tighter entry standards and ecological compensation for coastal reclamation, and embedding key LUCC indicators in the GBA integration performance evaluation. These measures support more balanced spatial development under the triple constraint of growth, ecological sustainability, and food security.

This study presents several limitations. The remote sensing data utilised, obtained from the National GIS Centre, reveal discrepancies across different years due to the extended duration of the study period. Additionally, the study deliberately considered 2018—the formal designation year of the GBA—as a critical temporal threshold to isolate the effects of market-driven and local governmental forces from national strategic interventions. However, constraints related to data availability and consistency limited this research period to only 1990–2018. Future research would greatly benefit from extending the analysis beyond 2018 to explicitly incorporate and evaluate the impacts of national strategic planning and regional integration policies enacted thereafter. In terms of spatial land development strategies, while this study investigates the driving forces behind land-use changes, it has limitations for explaining continuous and dynamic LUCC driving factors across different periods. This limitation highlights the necessity for future research to explore these temporal dynamics in greater detail. Building on both the findings of this research and the existing literature, three key directions are proposed for future studies into LUCC in the GBA. First, the further exploration of agglomeration economies’ influence on urban growth is necessary, particularly concerning the relationship between economic clustering and spatial development within the GBA. Second, conducting a cost–benefit analysis of land-use planning could facilitate an evaluation of land-use efficiency in this region. Third, the evaluation of the human–land linkage efficiency is essential for a better understanding of how population growth interacts with land expansion in the GBA.