Research on Influencing Factors of Carbon Emissions in the Regional Construction Industry: A Case Study of Jiangxi Province

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Research on CE Accounting in the Construction Industry

2.2. Research on Influencing Factors of CE in the Construction Industry

2.3. Research on CE Forecasting in the Construction Industry

3. Research Methods and Data Sources

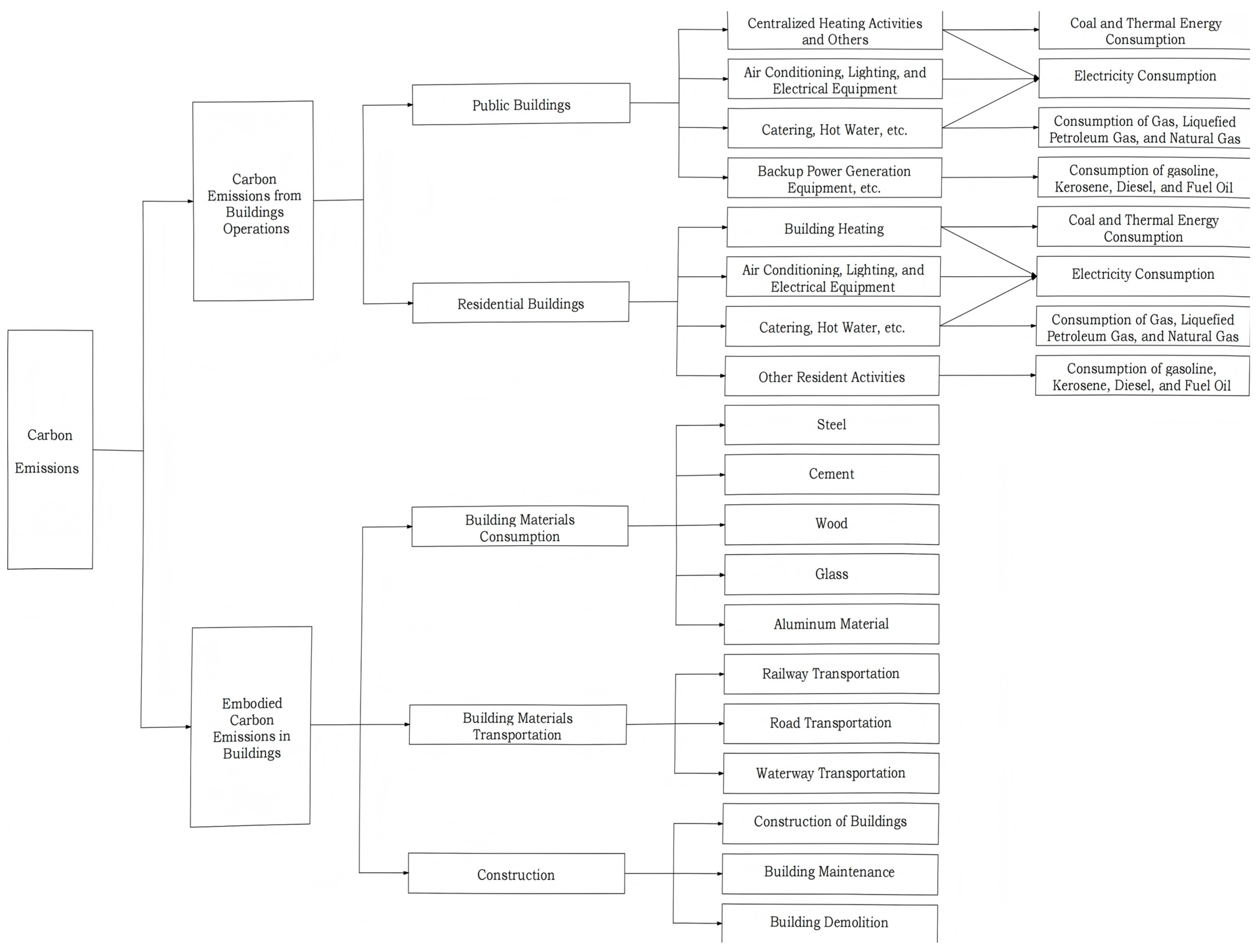

3.1. Calculation Model of the LCCE and the Selection of CEF

3.1.1. Calculation Model of the LCCE

3.1.2. CEF for the LCCE

3.2. Grey Relation Analysis

3.3. A CE Regression Model Based on the STIRPAT Model

3.4. Sources of Data

3.5. Innovativeness and Strengths of the Methodological Framework

4. Construction of CE Influencing Factor Model

4.1. Identification of Influencing Factors

4.1.1. Population Factors

4.1.2. Economic Factors

4.1.3. Technical Factors

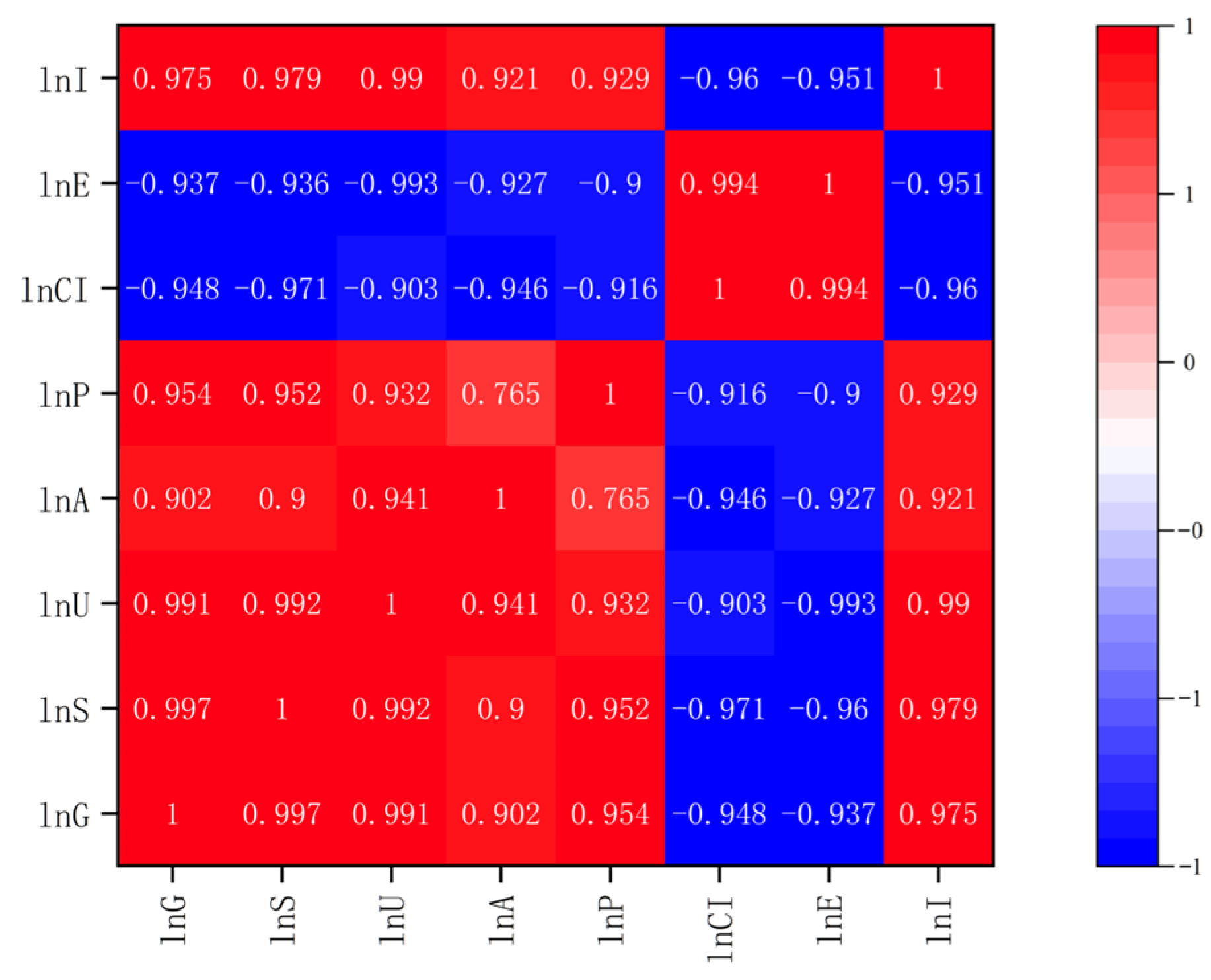

4.2. Grey Relation Analysis

4.3. Robustness Test

4.3.1. Sensitivity Analysis

4.3.2. Cross-Validation

4.4. Indicator Selection and Model Construction

5. CE Calculation Results and Regression Analysis of STIRPAT Model

5.1. Calculation of LCCE

5.1.1. Calculation of CE from Building Operation

5.1.2. Calculation of Embodied CE in Construction

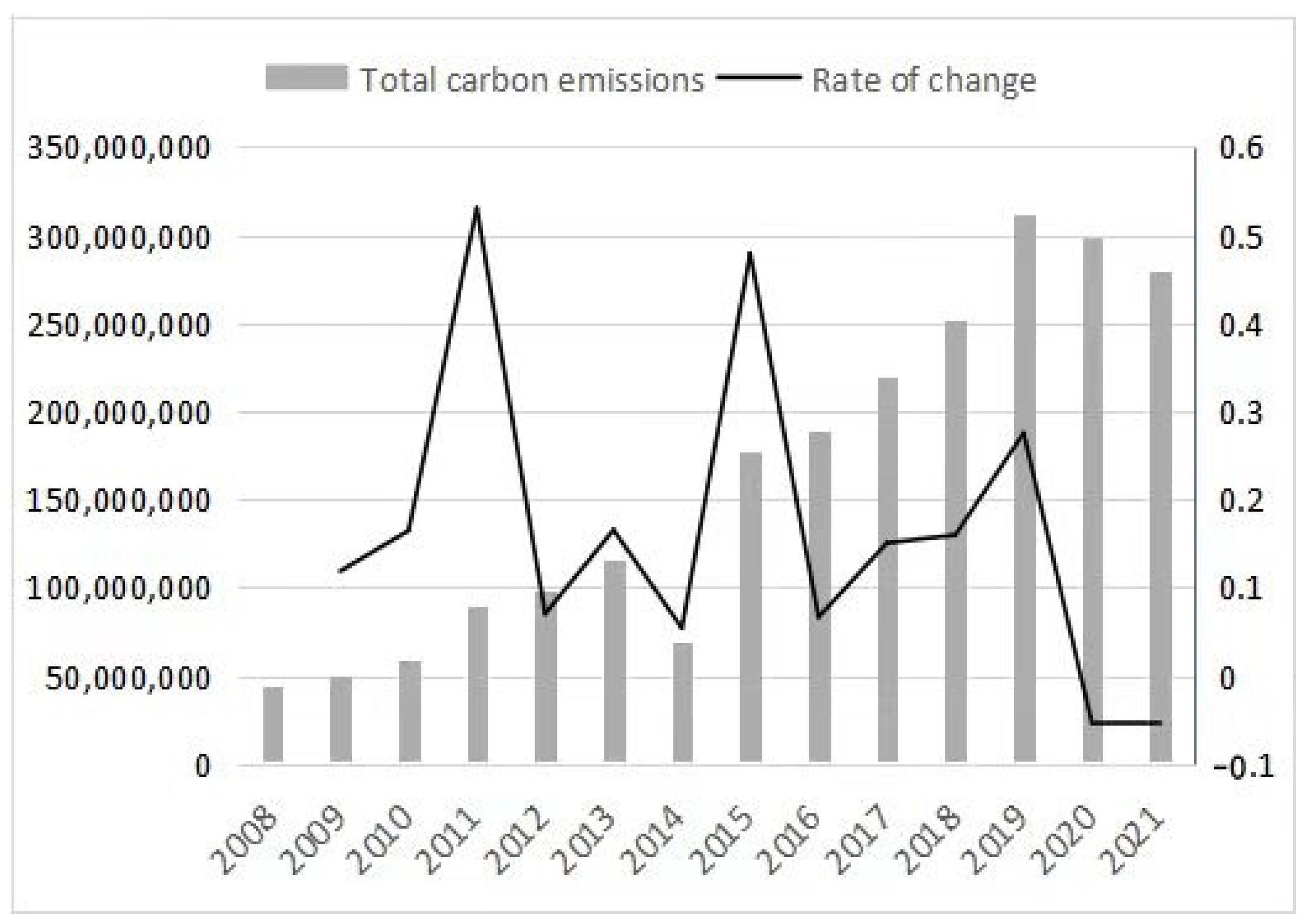

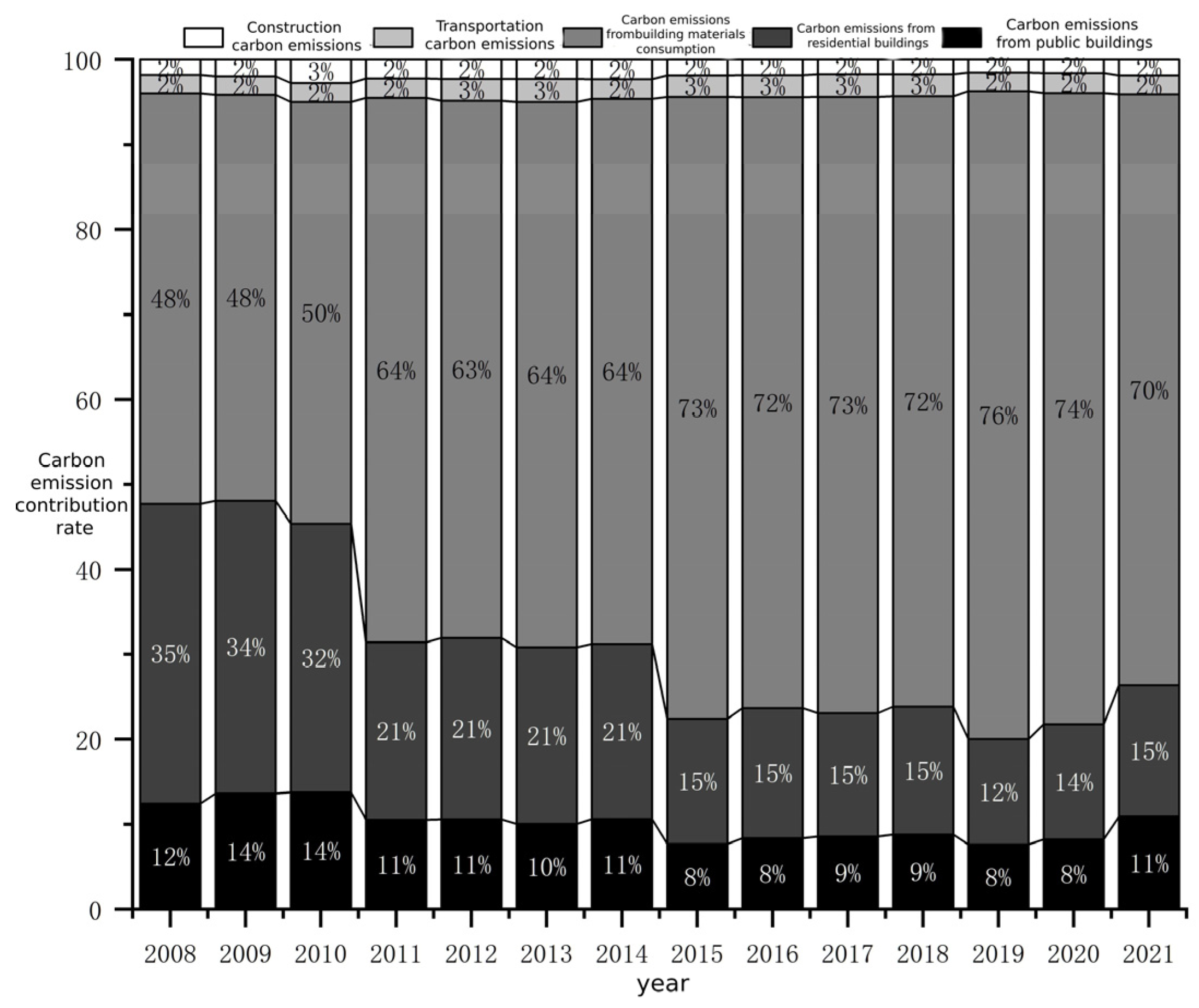

5.2. Jiangxi Province Construction Industry CE Estimation Results

5.3. Multiple Linear Regression Analysis

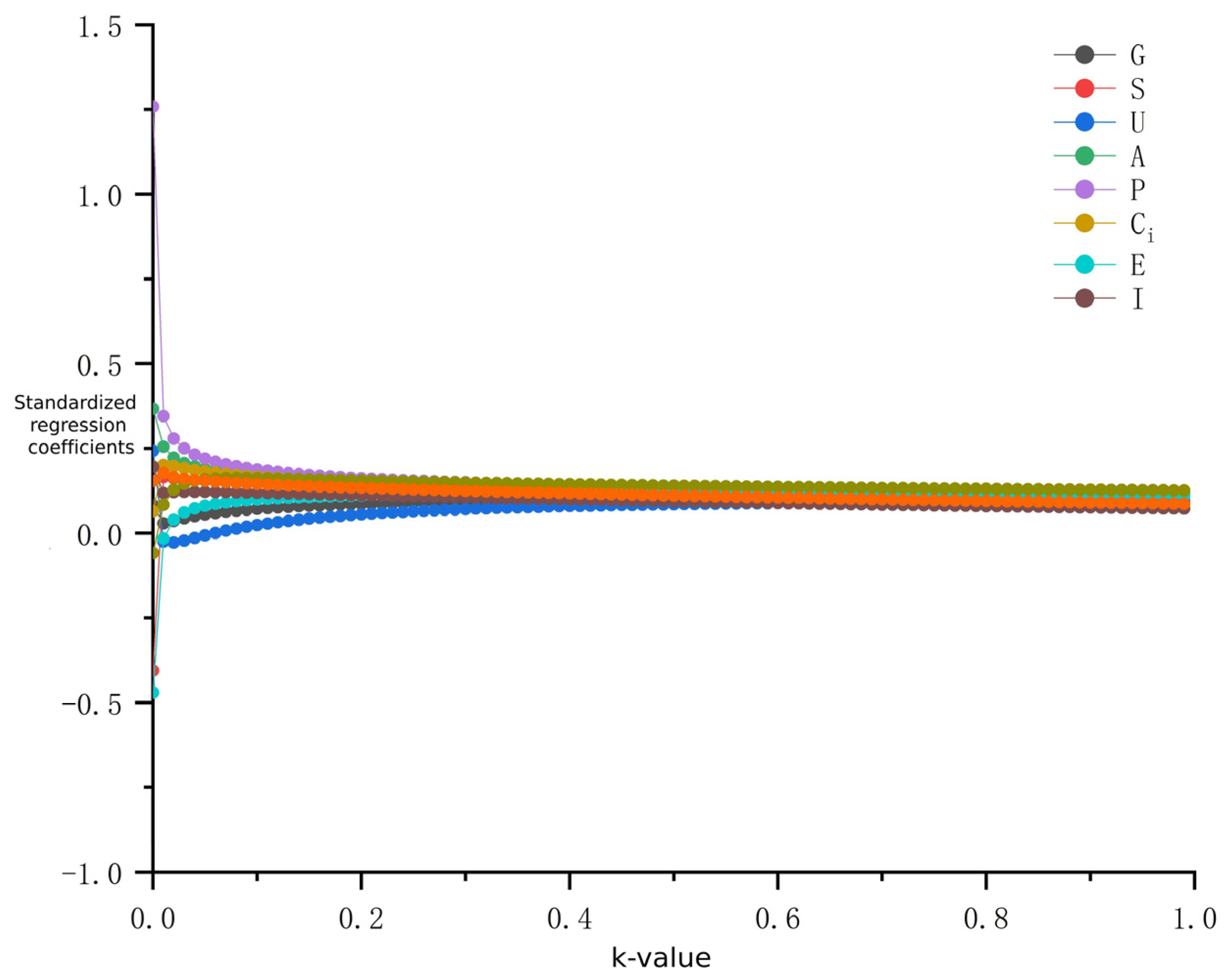

5.4. STIRPAT Model Ridge Regression Fitting

5.5. Analysis of Influencing Factors of CE in Residential Buildings in Jiangxi Province

6. Conclusions and Outlook

6.1. Conclusions

6.2. Discussion

6.2.1. Analysis of Commonalities in CE in Jiangxi Province

6.2.2. Analysis of Uniqueness in CE in Jiangxi Province

6.3. Recommendations

6.4. Limitations and Future Outlook

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- China Meteorological Administration. China Climate Bulletin. 2024. Available online: https://www.cma.gov.cn/zfxxgk/gknr/qxbg/202503/t20250302_6886935.html (accessed on 17 November 2025).

- China Building Energy Conservation Association, Committee of Building Energy Consumption and Carbon Emission Data. Research Report on Carbon Emissions in Urban and Rural Construction Sector, 2024th ed.; China Building Energy Conservation Association, Committee of Building Energy Consumption and Carbon Emission Data: Chongqing, China, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- China Building Energy Conservation Association. Research Report on Building Energy Consumption in China, 2020. Build. Energy Conserv. 2021, 49, 1–6. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=-xbefZa1CdvBZGyzSm3ZK6Shc1D630Pw3Do0GCDp38j1bTOk0gOhOY4fI9VKUR92FxXpjlPbkoBZ_dIeQanvmZ5lsNUy79JRNd-PQGNOe2Ia-8shYrFi7YWc95CVULdao2--HKiF-klOh3NFY1wFlj0mJrrzFvARaBBr7iJ41GY=&uniplatform=NZKPT (accessed on 17 November 2025).

- Zhou, N.; Khanna, N.; Feng, W.; Ke, J.; Levine, M. Scenarios of energy efficiency and CO2 emissions reduction potential in the buildings sector in China to year 2050. Nat. Energy 2018, 3, 978–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xian, Y.; Wang, H.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, Y.; Zhong, Y. Driving factors and reduction paths dynamic simulation optimization of carbon dioxide emissions in China’s construction industry under the perspective of dual carbon targets. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2025, 112, 107789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- China Building Energy Conservation Association, Committee of Building Energy Consumption and Carbon Emission Data. Research Report on China’s Building Energy Consumption and Carbon Emissions, 2022; China Building Energy Conservation Association, Committee of Building Energy Consumption and Carbon Emission Data: Chongqing, China, 2022; Available online: http://www.aaachina.org/nd.jsp?id=273 (accessed on 17 November 2025).

- Liu, Y.; Hu, W.; Xing, Y. A Study on the Factors Affecting Carbon Emissions of Public Service Buildings in China—Based on Two Carbon Emission Calculation Methods. Value Eng. 2023, 42, 135–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, M.; Yan, R.; Cai, W. An extended STIRPAT model-based methodology for evaluating the driving forces affecting carbon emissions in existing public building sector: Evidence from China in 2000–2015. Nat. Hazards 2017, 89, 741–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Li, X. The Impact of Environmental Regulation and Urbanization on Carbon Emissions—An Empirical Study Based on the STIRPAT Model and the EKC Hypothesis. J. Jingchu Univ. Technol. 2019, 34, 26–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Gao, W.; Su, Y.; Wang, T.; Wang, J. How can C&D waste recycling do a carbon emission contribution for construction industry in Japan city? Energy Build 2023, 298, 113538. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, H.; Wang, Q.; Zhu, L.; Zhang, Y. Prediction and Analysis of Building Carbon Emissions Based on the LEAP Model and LMDI Decomposition. J. Beijing Univ. Civ. Eng. Archit. 2023, 39, 80–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajasekharan, K.A.; Porchelvan, P. AN ANALYSIS OF LOW CARBON ENERGY ASSESSORS (LCEA) IN PUBLIC BUILDINGS. J. Eng. Res. 2022, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPCC. 2006 IPCC Guidelines for National Greenhouse Gas Inventories; IGES: Hayama, Japan, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, J.W.; Zhao, R.Q.; Huang, X.J.; Chen, Z.G. Research on China’s carbon emission accounting and its factor decomposition from 1995 to 2005. J. Nat. Resour. 2010, 25, 1284–1295. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z.; Liu, R. Carbon Emission Accounting in Construction Industry Based on Input-Output Analysis. J. Tsinghua Univ. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2013, 53, 53–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agyekum, K.; Sackey, K.N.Y.S.; Addoh, F.E.; Pittri, H.; Sosu, J.; Danso, F.O. Key Competencies of Built Environment Professionals for Achieving Net-Zero Carbon Emissions in the Ghanaian Construction Industry. Buildings 2025, 15, 1750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weigert, M.; Melnyk, O.; Winkler, L.; Raab, J. Carbon Emissions of Construction Processes on Urban Construction Sites. Sustainability 2022, 14, 12947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanafani, K.; Magnes, J.; Lindhard, S.M.; Balouktsi, M. Carbon Emissions during the Building Construction Phase: A Comprehensive Case Study of Construction Sites in Denmark. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onat, N.C.; Kucukvar, M.; Tatari, O. Scope-based carbon footprint analysis of U.S. residential and commercial buildings: An input–output hybrid life cycle assessment approach. Build. Environ. 2014, 72, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Yuan, X.; Wang, X. Analysis of influencing factors of carbon emission intensity in China’s construction industry. Environ. Eng. 2018, 36, 178–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roh, S.; Tae, S.; Kim, R. Developing a Green Building Index (GBI) Certification System to Effectively Reduce Carbon Emissions in South Korea’s Building Industry. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, X.; Wang, Z.; Gao, F. Research on Energy Consumption and Greenhouse Gas Emissions in the Life Cycle of Buildings with Different Structures. Hous. Ind. 2012, 51–54. Available online: https://qikan.cqvip.com/Qikan/Article/Detail?id=42160381 (accessed on 17 November 2025).

- Hu, W.; Guo, S. Empirical evidence on the decomposition of carbon emissions in the use stage of residential buildings in China. J. Tongji Univ. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2012, 40, 960–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, B.; Li, W.; Zhang, R.; Li, G. Analysis of the impact of carbon emission in China’s construction industry. Sci. Technol. Manag. Res. 2018, 38, 238–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labaran, Y.H.; Musa, A.A.; Mathur, V.S.; Saini, G. Exploring the carbon footprint of Nigeria’s construction sector: A quantitative insight. In Environment, Development and Sustainability; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2024; pp. 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Joseph, V.R.; Mustaffa, N.K.; Rani, I.A.; Isa, C.M. Key influence factors of carbon emissions in Malaysian construction operations. Proc. Inst. Civ. Eng. Eng. Sustain. 2024, 178, 77–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, D.; Tao, S.; Wang, R.; Shen, H.; Huang, Y.; Shen, G.; Wang, B.; Li, W.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, H.; et al. TTemporal and spatial trends of residential energy consumption and air pollutant emissions in China. Appl. Energy 2013, 106, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, S.; Feng, G.; Cui, H.; Zhang, L.; Li, Q. Prediction and analysis of carbon emission characteristics and emission reduction potential in the construction industry. J. Shenyang Jianzhu Univ. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2023, 39, 139–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Qi, S. Research on Direct Carbon Emission Accounting and Prediction in Fujian Province. Value Eng. 2017, 36, 77–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oladoyin Abidemi AkintolaCA1, Ayodeji Emmanuel Oke2. Evaluating net-zero carbon emission benefits in Nigeria’s construction industry. Energy Build. 2025, 349, 116509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustaffa, N.K.; Abdul Kudus, S.; Abdul Aziz, M.F.H.; Anak Joseph, V.R. Strategies and way forward of low carbon construction in Malaysia. Build. Res. Inf. 2022, 50, 628–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, J.; Jiang, X. Our country Research on carbon emission prediction in the construction industry. J. Ocean. Univ. China (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2012, 53–57. Available online: https://qikan.cqvip.com/Qikan/Article/Detail?id=41361528 (accessed on 17 November 2025).

- Chan, M.; Masrom, M.A.N.; Yasin, S.S. Selection of Low-Carbon Building Materials in Construction Projects: Construction Professionals’ Perspectives. Buildings 2022, 12, 486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Victoria, M.F.; Perera, S. Parametric embodied carbon prediction model for early stage estimating. Energy Build. 2018, 168, 106–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenninger, S.; Kaymakci, C.; Wiethe, C. Explainable long-term building energy consumption prediction using QLattice. Appl. Energy 2022, 308, 118300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development of the People’s Republic of China. GB/T 51366-2019 Standard for Building Carbon Emission Calculation[S]; China Architecture & Building Press: Beijing, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, S. The Origin and Development of Grey System Theory. J. Nanjing Univ. Aeronaut. Astronaut. 2004, 36, 267–272. Available online: https://d.wanfangdata.com.cn/periodical/njhkht200402027 (accessed on 17 November 2025).

- Liu, S.; Cai, H.; Yang, Y.; Cao, Y. Research progress of grey relational analysis model. Syst. Eng.—Theory Pract. 2013, 33, 2041–2046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietz, T.; Rosa, E.A. Rethinking the environmental impacts of population, Affluence and technology. Hum. Ecol. Rev. 1994, 1, 277–300. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/24706840 (accessed on 17 November 2025).

- Jiangxi Provincial Bureau of Statistics. Jiangxi Statistical Yearbook; China Statistics Press: Beijing, China, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Fixed Asset Investment Statistics; National Bureau of Statistics of the People’s Republic of China. Statistical Yearbook of China’s Construction Industry; China Statistics Press: Beijing, China, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Energy Statistics; National Bureau of Statistics of the People’s Republic of China. China Energy Statistics Yearbook; China Statistics Press: Beijing, China, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, W.; Li, X.; Wang, X.; Chen, M.; Wu, Y. A Building Energy Consumption Decomposition Model Based on Energy Balance Table and Its Application. Heat. Vent. Air Cond. 2017, 47, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, T.; Ma, Y.; Cai, W.; Liu, B.; Mu, L. Will the urbanization process influence the peak of carbon emissions in the building sector? A dynamic scenario simulation. Energy Build. 2021, 232, 110590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, H.; Long, Y.; Wood, R.; Moran, D.; Zhang, Z.; Meng, J.; Guan, D. Ageing society in developed countries challenges carbon mitigation. Nat. Clim. Change 2022, 12, 241–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.; Rao, Z.; Liu, J.; Chen, Y.; Liao, S. Prediction of Energy Demand in Changsha City and Countermeasures Based on the LEAP Model. Resour. Sci. 2017, 39, 482–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H.; Li, Y.; Cao, M. How to Achieve Carbon Reduction and Growth?—An Empirical Study Based on the New Energy Demonstration City Policy. J. Financ. Econ. 2024, 50, 126–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W.; Cheng, Y. Analysis of Influencing Factors of Carbon Emissions in China’s Construction Industry and Prediction of Carbon Peak and Carbon Neutrality. J. Hebei Inst. Environ. Eng. 2024, 34, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Yang, J.; Sheng, P. The Impact of Urbanization on China’s Carbon Emissions and Its Channels of Action. China Popul. Resour. Environ. 2016, 26, 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian, Y.; Su, D.; Shi, S. Carbon Peak Prediction in Fujian Province Based on Combined STIRPAT and CNN-LSTM Models. Environ. Sci. 2025, 46, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Su, B.; Zhou, K.; Yang, S. Decomposition analysis of China’s CO2 emissions (2000–2016) and scenario analysis of its carbon intensity targets in 2020 and 2030. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 668, 432–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, J.; Li, Y.; Cai, W. Simulation of China’s Carbon Peak Paths from a Multi-Scenario Perspective—Based on the RICE-LEAP Model. Resour. Sci. 2021, 43, 639–651. Available online: https://d.wanfangdata.com.cn/periodical/zykx202104002 (accessed on 17 November 2025).

- Shi, Q.; Liang, Q.; Wang, J.; Huo, T.; Gao, J.; You, K.; Cai, W. Dynamic scenario simulations of phased carbon peaking in China’s building sector through 2030–2050. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2023, 35, 724–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, L.; Zhagn, L.; Xi, F.; Wang, J. Influencing factors and scenario forecasting of carbon emissions in Liaoning Province, China. J. Appl. Ecol. 2023, 34, 499–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, Y.-M.; Gao, Y.; Yuan, M.; Liu, W.; Liu, F.-T. Data-driven Analysis on the Spatio-temporal Characteristics and Influencing Factors of Carbon Emissions in Guangdong Province. Environ. Sci. 2025, 46, 1482–1491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Li, C.; Chen, X.; Luo, G.; Li, L.; Li, X.; Yan, Y.; Shao, H. A spatial-explicit dynamic vegetation model that couples carbon, water, and nitrogen processes for arid and semiarid ecosystems. J. Arid Land 2013, 5, 102–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.-H.; Hu, P.-C.; Cheng, P.-F. Carbon Emission Accounting and Peak Carbon Prediction of China’s Construction Industry from a Whole Life Cycle Perspective. Environ. Sci. 2025, 46, 2020–2034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, X.; Wu, X. A Geometric Interpretation of Multicollinearity in Linear Regression. Stat. Decis. 2021, 37, 46–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, N. The Unique Role of Ridge Regression Analysis in Solving Multicollinearity Problems. Stat. Decis. 2004, 3, 14–15. Available online: https://qikan.cqvip.com/Qikan/Article/Detail?id=9356940 (accessed on 16 November 2025).

- Zhang, X.-S.; Nie, D.-W.; Chen, Z.-Z.; Wang, R.-Z.; Su, J. Analysis of the Temporal and Spatial Evolution Characteristics and Influencing Factors of Carbon Emissions in the Construction Industry in Western Regions. Environ. Sci. 2025, 46, 5475–5489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, L. Analysis of the Temporal and Spatial Characteristics and Influencing Factors of Carbon Emission Changes in the Construction Industry in the Yangtze River Delta Region. China Environ. Sci. 2023, 43, 6677–6688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Zheng, Y.; Xu, X.; Liu, X.; Zhang, H.; Ou, J. Fine-scale estimation of building operation carbon emissions: A case study of the Pearl River Delta Urban Agglomeration. Build. Simul. 2025, 18, 957–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Li, F.; Xia, X. Research on the Decoupling of Carbon Emissions from Buildings in Shenzhen and Its Influencing Factors. Constr. Technol. 2018, 2, 52–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, H.; Liu, Z. A Study on the Influencing Factors of Carbon Emissions in China’s Construction Industry Based on the Dynamic Spatial Durbin Panel Model. Ecol. Econ. 2017, 33, 74–80. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, J.; Kuai, L.; An, H. The Impact Mechanism of Digital Economy on Carbon Emissions in the Construction Industry: A Case Study of the Yangtze River Delta Urban Agglomeration. Environ. Sci. 2025, 1–16. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=X7jC3qydZ5_g4RwBkOyhhTZALacPBXWfXaTx6bMWUHmiwHBPSkG4nsiPl1kS13jfl9S5sLrHfHFNDh4KFYpmljMU6MQwkaQZuSOPXkTfleQB9ScF3oMysLkwxqs-WKZqGRgmPlLhUaGMt1gRN01G_TG4PcCea6cEu-4yD51HAA8=&uniplatform=NZKPT (accessed on 16 November 2025).

- Chen, L.; Huang, L.; Hua, J.; Chen, Z.; Wei, L.; Osman, A.I.; Fawzy, S.; Rooney, D.W.; Dong, L.; Yap, P.-S. Green construction for low-carbon cities: A review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2023, 21, 1627–1657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhar, S.; Pathak, M.; Shukla, P.R. Transformation of India’s steel and cement industry in a sustainable 1.5 °C world. Energy Policy 2020, 137, 111104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Energy Type | Unit of Measure | Lower Calorific Value (KJ/Unit of Measure) | CEF (kgCO2/Unit) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Raw coal | kg | 20,908 | 1.91 |

| Gasoline | kg | 43,070 | 2.936 |

| Diesel | kg | 42,652 | 3.107 |

| Natural gas | m3 | 38,931 | 2.164 |

| Liquefied Petroleum Gas | kg | 51,434 | 3.192 |

| Fuel oil | kg | 41,816 | 3.181 |

| Refinery dry gas | kg | 45,998 | 3.011 |

| Other coal washing | kg | 19,969 | 1.832 |

| Coal product | kg | 15,472 | 1.72 |

| Coal gangue | kg | 8363 | 0.779 |

| Coke oven gas | m3 | 17,354 | 0.771 |

| Blast furnace gas | m3 | 3763 | 0.977 |

| Converter gas | m3 | 7945 | 1.446 |

| Category | CEF | Unit |

|---|---|---|

| Steel | 2.05 | tCO2e/t |

| Timber | 0.735 | tCO2e/t |

| Cement | 0.178 | tCO2e/t |

| Glass | 1.13 | tCO2e/t |

| Aluminum material | 20.5 | tCO2e/t |

| Railway | 0.01 | kgCO2e/(t·km) |

| Road | 0.17 | kgCO2e/(t·km) |

| waterway | 0.015 | kgCO2e/(t·km) |

| Classification | Influencing Factors | Measurement Metrics |

|---|---|---|

| Population | Total regional population UR The degree of population aging | P U A |

| Economy | GDP per capita Construction industry gross output value | G S |

| Technology | Unit energy consumption of added value in construction industry Green technology innovation level CEI of the construction industry | E I Ci |

| Factors Affecting | Measurement Indicators | Correlation Degree |

|---|---|---|

| GDP per capita | G | 0.888 |

| Construction industry gross output value | S | 0.885 |

| Urbanization rate | U | 0.821 |

| The degree of population aging | A | 0.813 |

| Total regional population (TP) | P | 0.808 |

| CEI of the construction industry | Ci | 0.793 |

| Energy consumption per added value unit of construction industry (ton of standard coal/ten thousand yuan) | E | 0.791 |

| Green technology innovation level (patent number per 10,000 people) | I | 0.703 |

| Results of Relational Degree (ρ = 0.3) | Results of Relational Degree (ρ = 0.7) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Evaluation Item | Relational Degree | Ranking | Evaluation Item | Relational Degree | Ranking |

| S | 0.861 | 1 | S | 0.932 | 1 |

| G | 0.833 | 2 | G | 0.915 | 2 |

| U | 0.748 | 3 | U | 0.861 | 3 |

| A | 0.737 | 4 | A | 0.854 | 4 |

| P | 0.731 | 5 | P | 0.85 | 5 |

| Ci | 0.71 | 6 | Ci | 0.838 | 6 |

| E | 0.709 | 7 | E | 0.837 | 7 |

| I | 0.628 | 8 | I | 0.751 | 8 |

| G | S | Ci | P | A | I | E | U | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C | Correlation Coefficient | 0.956 ** | 0.949 ** | 0.194 | 0.876 ** | 0.898 ** | 0.827 ** | 0.252 | 0.928 ** |

| Significance (Two-tailed) | <0.01 | <0.01 | 0.507 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | 0.385 | <0.01 | |

| N | 14 | 14 | 14 | 14 | 14 | 14 | 14 | 14 |

| Model | R | R2 | Adjusted R2 | Error of Std Estimation | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.000 | 0.999 | 0.998 | 0.01534 | ||||

| Unstd Coefficient | Std Coefficient | t | Significance | Collinearity Statistics | |||

| B | Std Error | Beta | Tolerance | VIF | |||

| (Constant) | 12.775 | 12.244 | 1.043 | 0.345 | |||

| ln G | 0.141 | 0.145 | 0.091 | 0.971 | 0.376 | 0.004 | 232.182 |

| ln S | 0.953 | 0.139 | 0.991 | 6.854 | 0.001 | 0.002 | 557.146 |

| ln U | 0.782 | 0.831 | 0.042 | 0.270 | 0.798 | 0.002 | 651.519 |

| ln A | 0.052 | 0.150 | 0.011 | 0.346 | 0.744 | 0.035 | 28.359 |

| ln P | 0.449 | 1.581 | 0.005 | 0.284 | 0.788 | 0.106 | 79.476 |

| ln Ci | 0.914 | 0.371 | 0.316 | 2.467 | 0.057 | 0.002 | 437.970 |

| ln E | 0.057 | 0.389 | 0.020 | 0.146 | 0.889 | 0.002 | 483.447 |

| ln I | −0.003 | 0.041 | −0.006 | −0.083 | 0.937 | 0.009 | 116.990 |

| Model | Sum of Squares | Freedom | Mean Square | F | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regression | 6.278 | 8 | 0.785 | 823.152 | <0.001 |

| Residual | 0.001 | 5 | 0.001 | ||

| Total | 6.279 | 13 |

| Dimension | Eigenvalue | Conditional Indicators | Variance Proportion | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | ln G | ln S | ln U | ln A | ln P | ln Ci | ln E | ln I | |||

| 1 | 8.121 | 1.000 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| 2 | 0.555 | 3.826 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| 3 | 0.324 | 5.009 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| 4 | 0.001 | 117.549 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.21 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| 5 | 0.000 | 238.131 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.23 | 0.24 | 0.21 |

| 6 | 8.838 × 10−5 | 303.121 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.49 | 0.44 | 0.10 |

| 7 | 5.380 × 10−6 | 1228.608 | 0.00 | 0.95 | 0.44 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.19 | 0.20 | 0.10 |

| 8 | 1.278 × 10−6 | 2521.020 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.51 | 0.89 | 0.68 | 0.01 | 0.07 | 0.08 | 0.30 |

| 9 | 5.180 × 10−8 | 12,520.439 | 0.99 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.09 | 0.09 | 0.99 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.28 |

| Unstd Coefficient | Std Coefficient | T | Significance | VIF | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | Std Error | Beta | ||||

| (Constant) | −12.78 | 2.737 | - | −4.521 | 0.006 | |

| ln G | 0.307 | 0.033 | 0.197 | 9.195 | 0.000 | 0.334 |

| ln S | 0.296 | 0.018 | 0.203 | 11.047 | 0.000 | 0.269 |

| ln U | 0.526 | 0.051 | 0.174 | 18.137 | 0.000 | 0.125 |

| ln A | 0.181 | 0.18 | 0.105 | 2.671 | 0.044 | 1.314 |

| ln P | 0.576 | 3.287 | 0.175 | 4.794 | 0.005 | 1.314 |

| ln Ci | 0.414 | 0.058 | 0.143 | 7.152 | 0.001 | 0.272 |

| ln E | 0.32 | 0.056 | 0.11 | 5.707 | 0.002 | 0.255 |

| ln I | −0.101 | 0.018 | −0.165 | −5.584 | 0.003 | 0.599 |

| R2 | 0.992 | |||||

| Adjusted R2 | 0.979 | |||||

| F | F(8,5) = 76.527, p = 0.000 | |||||

| Sum of Squares | df | Mean Square | F | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regression | 6.229 | 8 | 0.779 | 76.527 | 0.000 |

| Residual | 0.051 | 5 | 0.010 | ||

| Total | 6.279 | 13 |

| Factors Affecting | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GDP per capita (G) | 0.307 | 11.59% | 3.56% | 13.99% |

| Construction industry gross production value (S) | 0.296 | 18.86% | 3.7% | 17.26% |

| Urbanization rate (U) | 0.526 | 3.09% | 2.86% | 11.70% |

| The degree of population aging (A) | 0.181 | 3.03% | 1.46% | 6.46% |

| Total population in the area (P) | 0.576 | 0.20% | 0.12% | 16.22% |

| CEI of the construction industry (Ci) | 0.414 | 3.07% | 1.27% | 9.72% |

| Energy consumption per unit of added value in the construction industry (E) | 0.32 | 3.64% | 1.16% | 8.92% |

| Green technology innovation water (I) | −0.201 | 26.38% | −5.30% | −13.51% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Guo, X.; Liu, J.; Fu, S.; Gu, J. Research on Influencing Factors of Carbon Emissions in the Regional Construction Industry: A Case Study of Jiangxi Province. Sustainability 2026, 18, 469. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010469

Guo X, Liu J, Fu S, Gu J. Research on Influencing Factors of Carbon Emissions in the Regional Construction Industry: A Case Study of Jiangxi Province. Sustainability. 2026; 18(1):469. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010469

Chicago/Turabian StyleGuo, Xiaojian, Jing Liu, Shenqiang Fu, and Jianglin Gu. 2026. "Research on Influencing Factors of Carbon Emissions in the Regional Construction Industry: A Case Study of Jiangxi Province" Sustainability 18, no. 1: 469. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010469

APA StyleGuo, X., Liu, J., Fu, S., & Gu, J. (2026). Research on Influencing Factors of Carbon Emissions in the Regional Construction Industry: A Case Study of Jiangxi Province. Sustainability, 18(1), 469. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010469