Shear Strength Evaluation of Precast Concrete Beam-Column Joints Considering Key Influencing Parameters

Abstract

1. Introduction

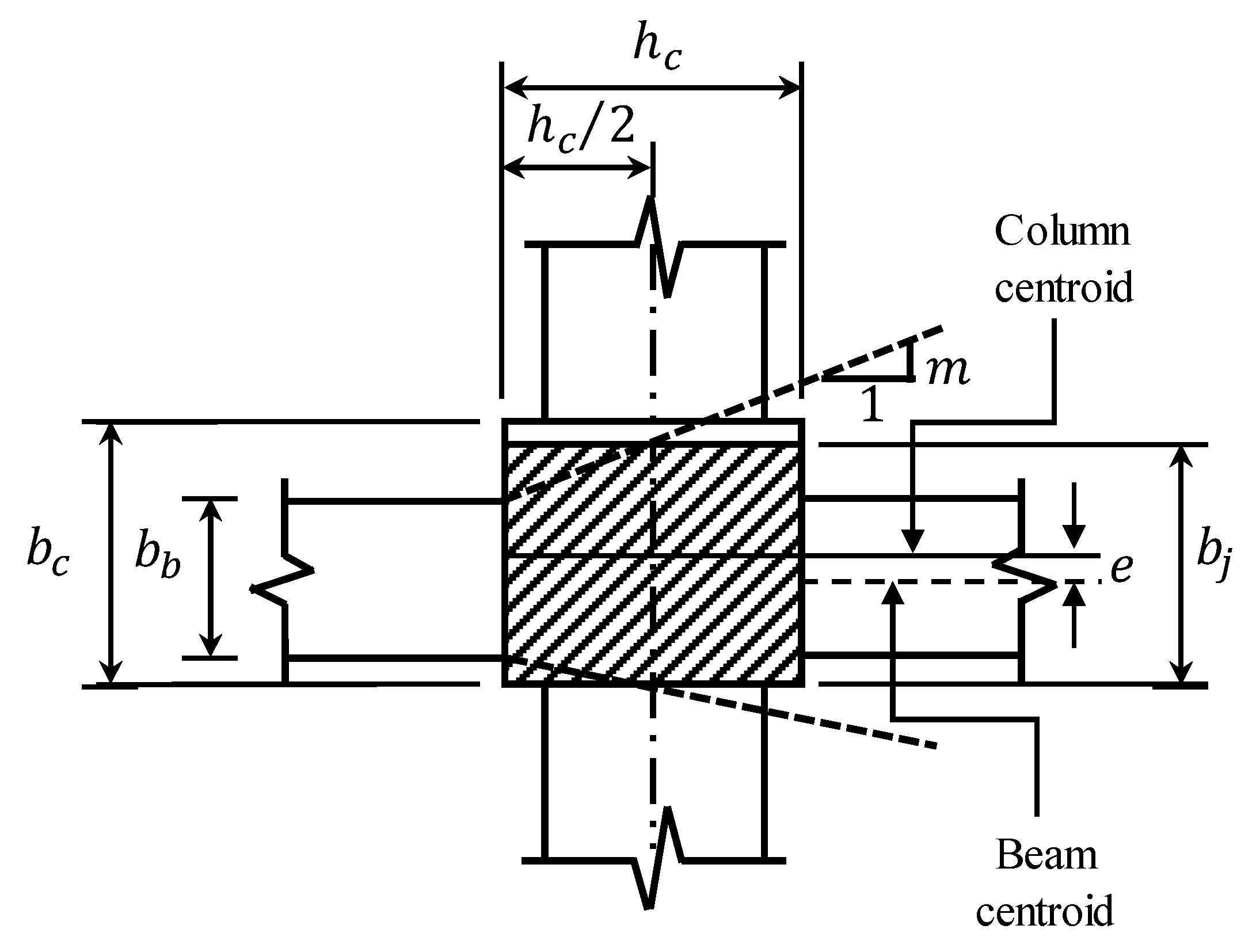

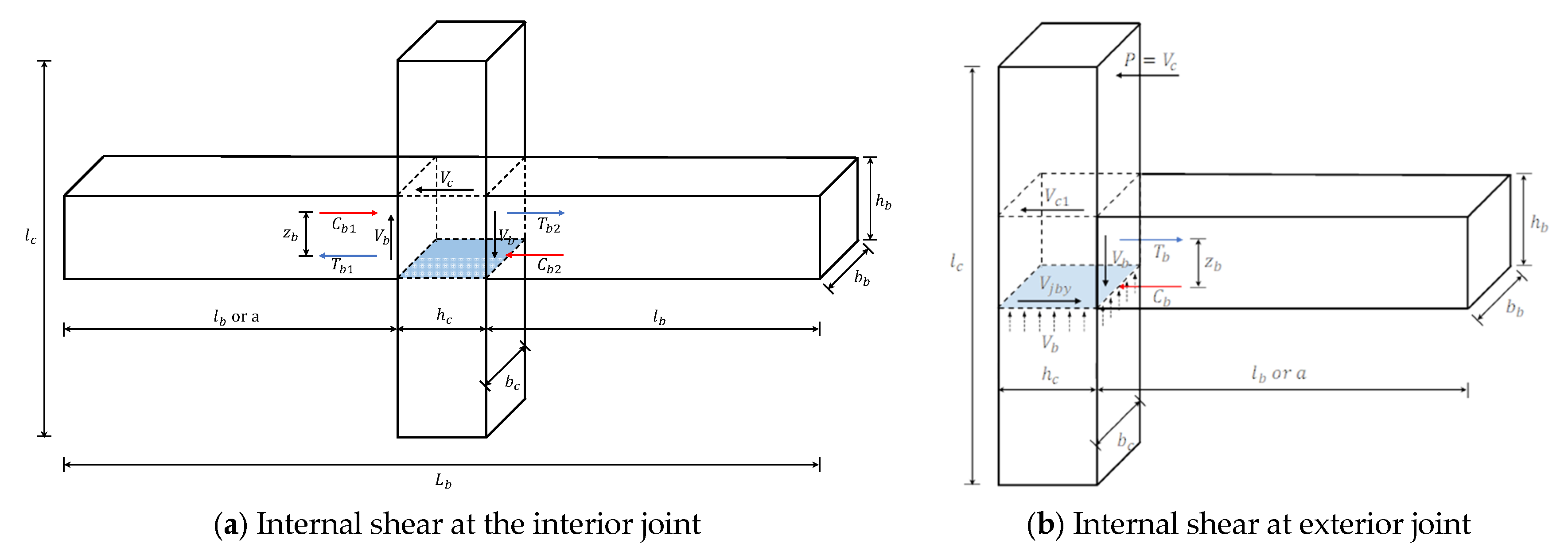

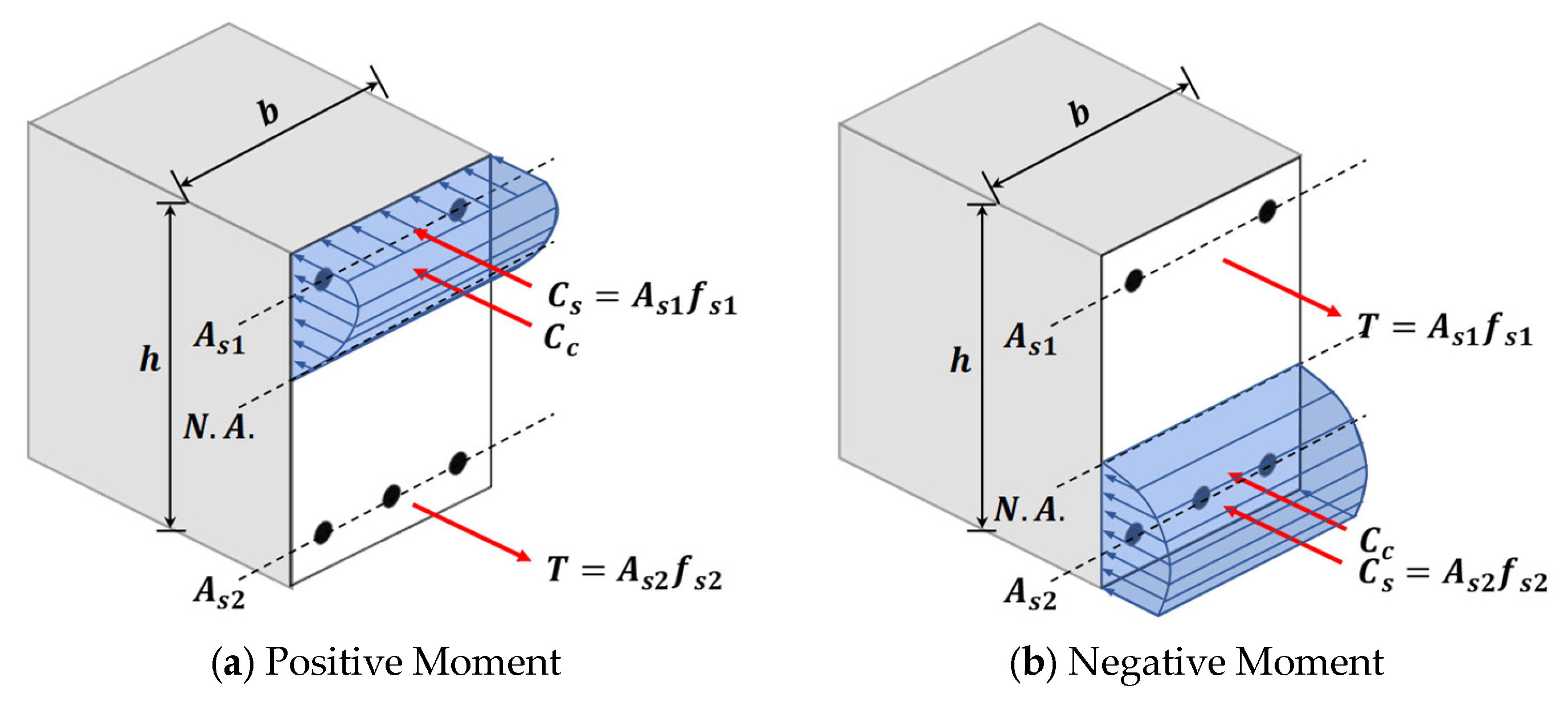

2. Theoretical Background of Joint Shear Strength

2.1. Nominal Shear Strength in the ACI Code

2.2. Shear Friction Mechanism for Connections

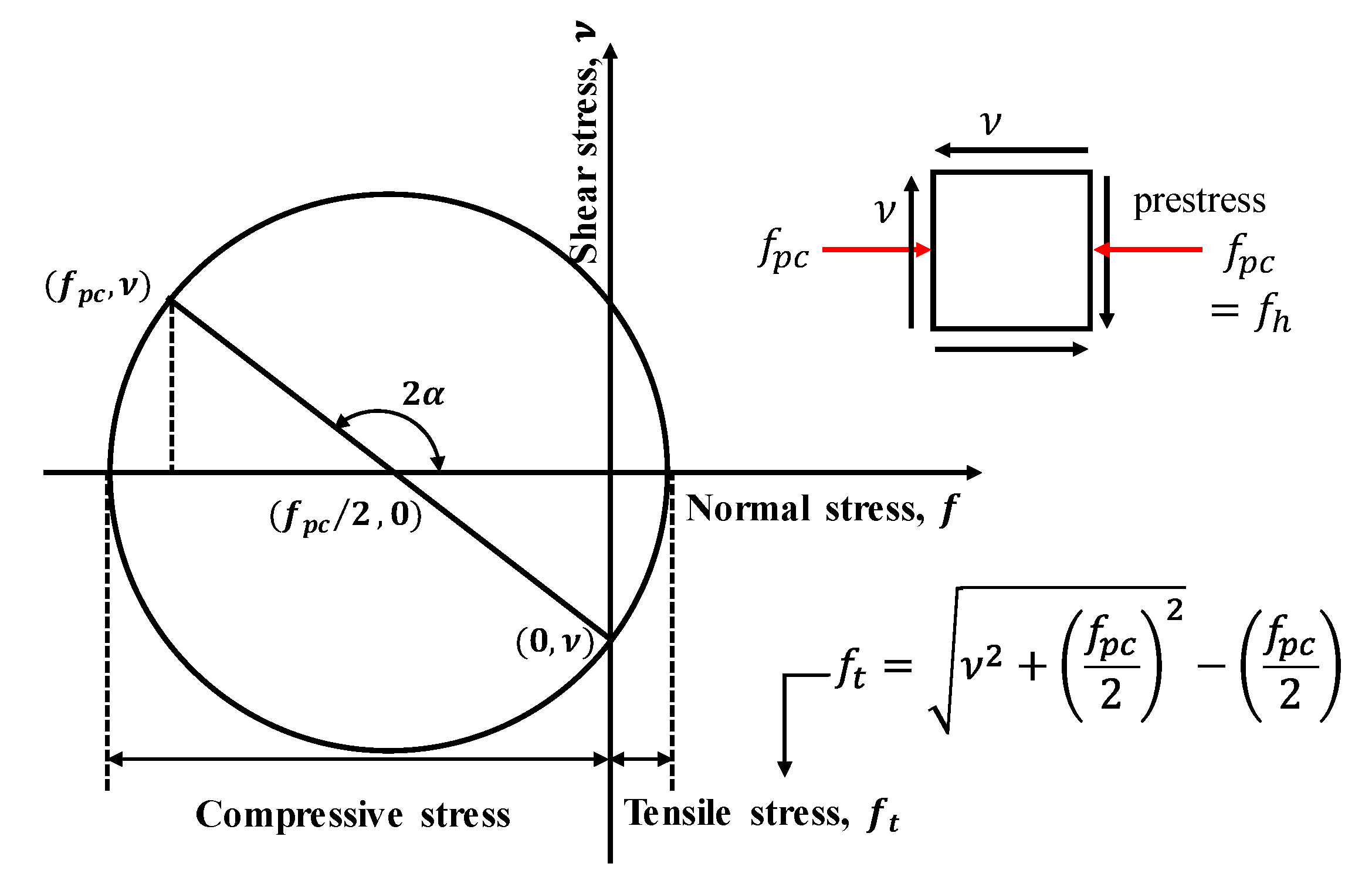

2.3. Influence of Prestressing

2.4. Combined Model for the Shear Strength of PC Beam-Column Joints

3. Experimental Database

3.1. Data Collection Criteria

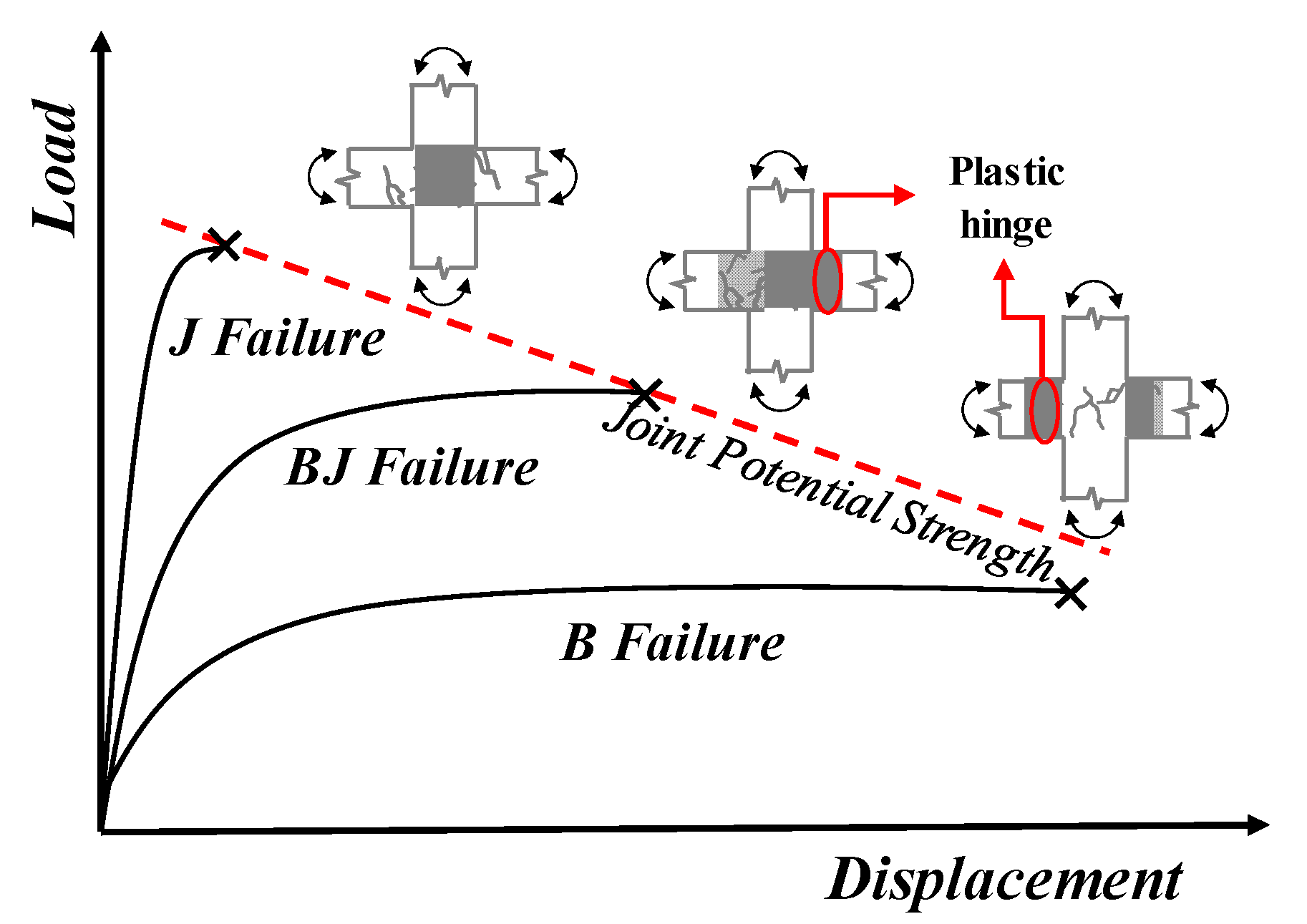

3.2. Classification of the Database

- (1)

- Classification by Prestressing Condition

- (2)

- Classification by Failure Mode

| J Failure | BJ Failure | B Failure | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-Prestressed | 15 | 23 | 24 | 62 |

| Prestressed | 12 | 3 | 10 | 25 |

| Total | 27 | 26 | 34 | 87 |

3.3. Range of Parameters

4. Results and Discussion

- ①

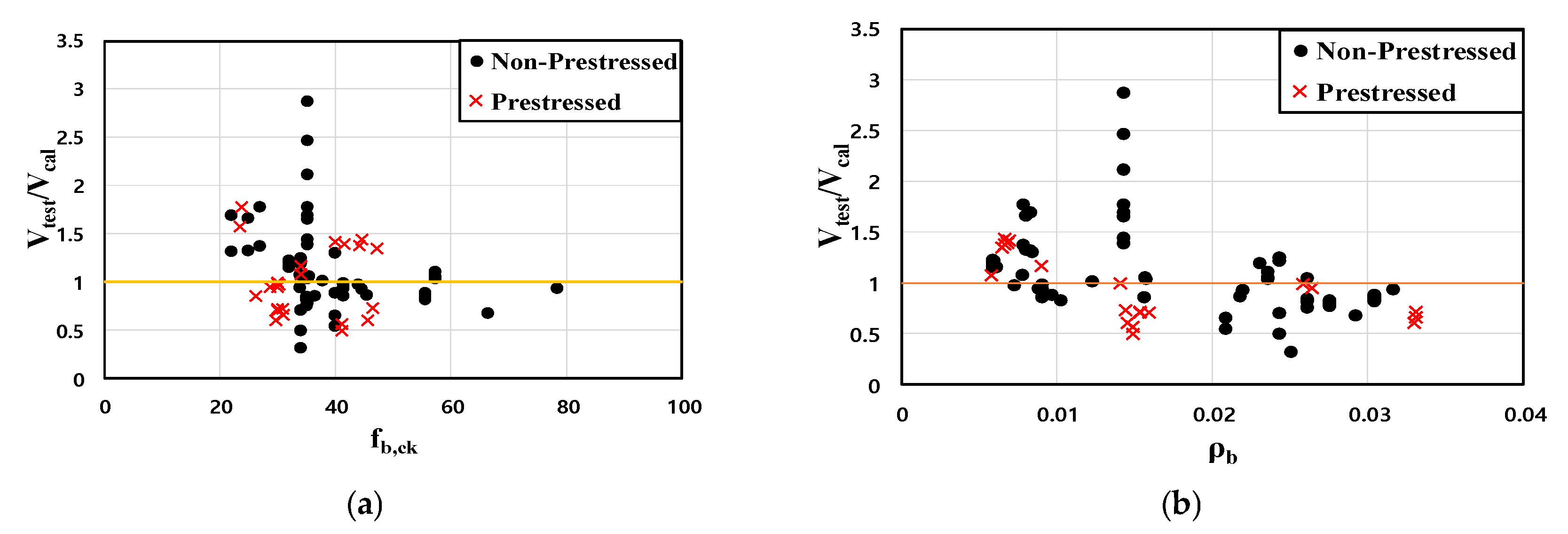

- As shown in Figure 7a, the shear strength was generally evaluated on the safe side (Vtest/Vcal > 1) in the range where the concrete compressive strength (fb,ck) was 40 MPa or less; however, the data dispersion is significantly large.

- ②

- For the reinforcement ratio (ρb), in the low reinforcement ratio range (<1.5% or 0.0015), data points show a very conservative Vtest/Vcal value of 2 or higher, and most fall on the safe side (Vtest/Vcal > 1). Data with reinforcement ratios of 2% or higher tend to show Vtest/Vcal values falling below 1, indicating a potential tendency to somewhat overestimate the shear strength of members with high reinforcement ratios.

- ③

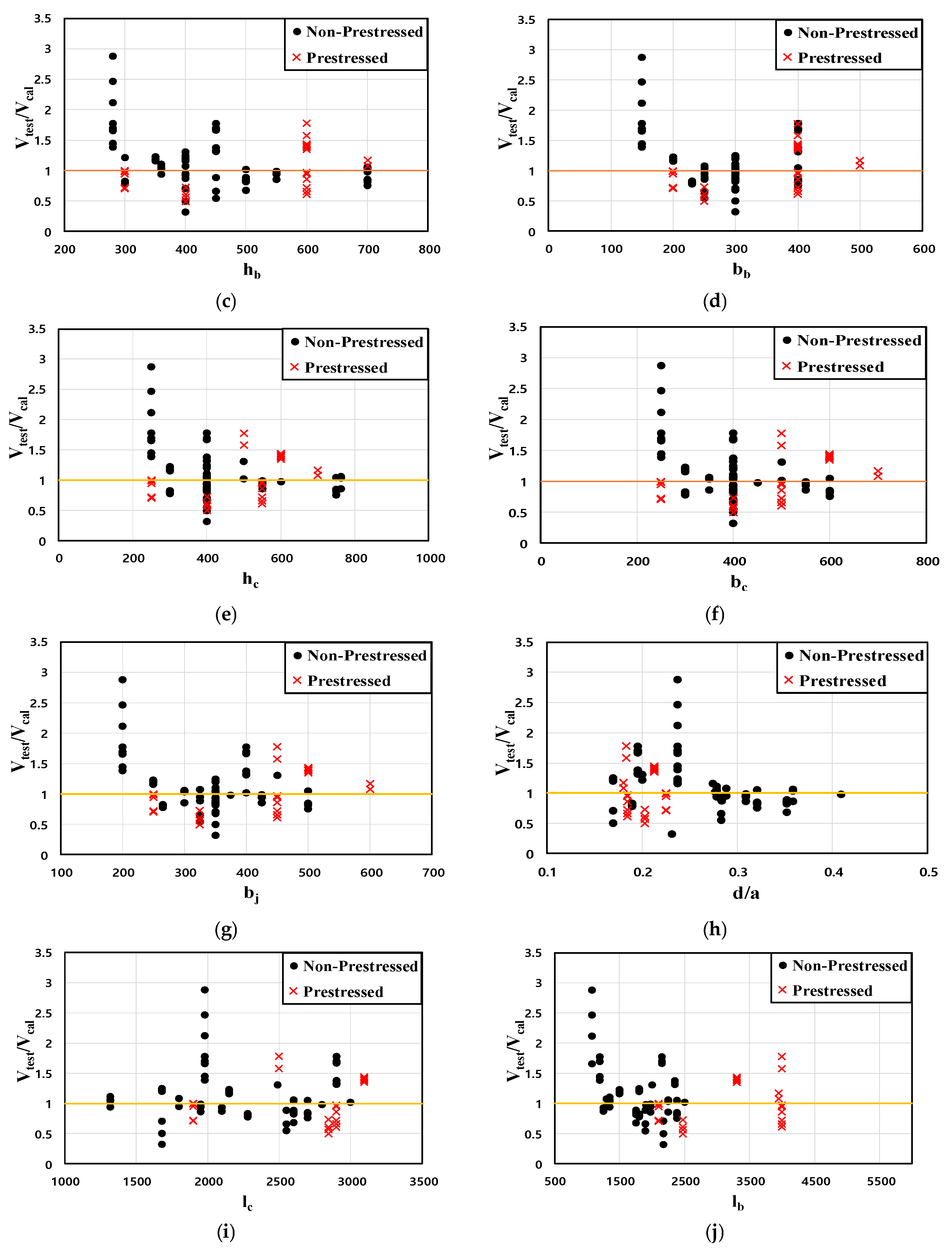

- All variables related to cross-sectional dimensions (bc, hc, bb, hb, bj) show a similar trend. The variables predict a large shear strength compared to experimental values for small cross-sections, indicating a very conservative approach. As the cross-section increases, the safety margin tends to decrease. For columns, test specimens were generally close to square (i.e., and smaller column sizes tended to underestimate the shear strength at the joint. For beams, specimens with hb larger than bb were more common. Unlike columns, no distinct trend emerged for beams; underestimation of shear strength occurred for small beams and for relatively large beams around hb = 600 mm and bb = 400 mm.

- ①

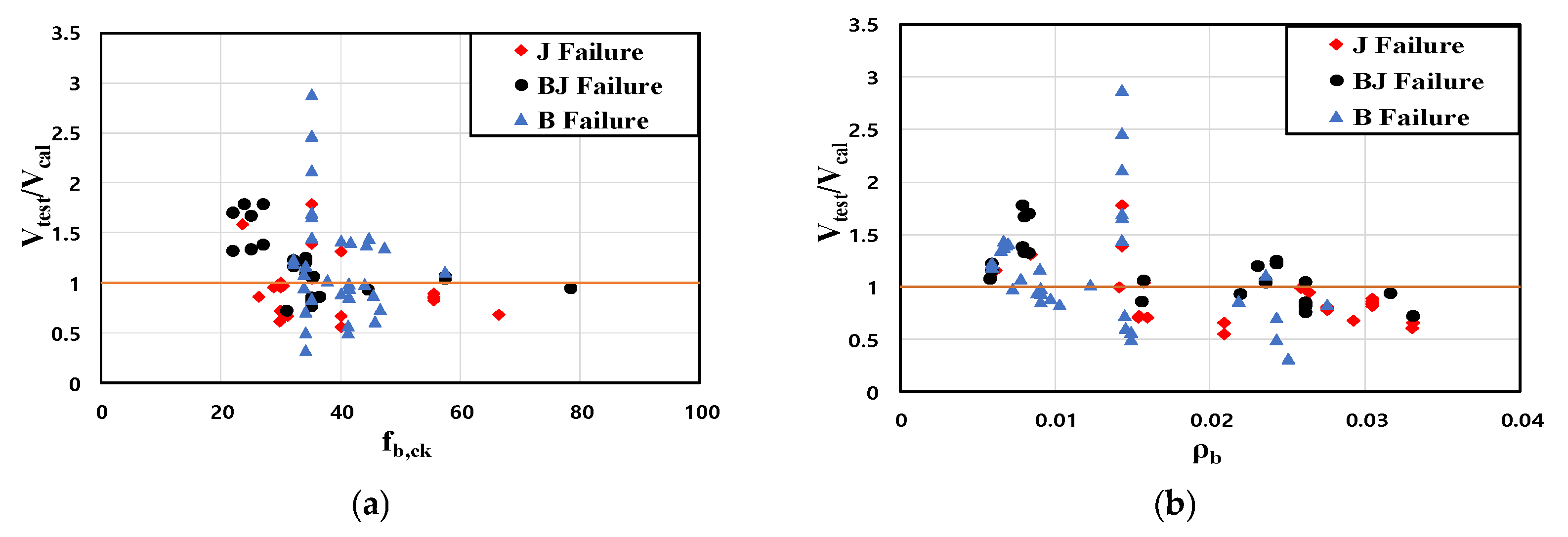

- Analysis of the effect of the beam concrete compressive strength (fb,ck) on failure modes reveals that BJ and B Failure are more prevalent as the concrete compressive strength decreases. This is because lower concrete compressive strength reduces the load-carrying capacity of the beam, resulting in the joint strength primarily determined by Vjby.

- ②

- The classification of failure modes based on the reinforcement ratio (ρb) was not clearly evident. Consequently, the influence of the reinforcement ratio (ρb) on determining the failure mode is judged to be negligible.

- ③

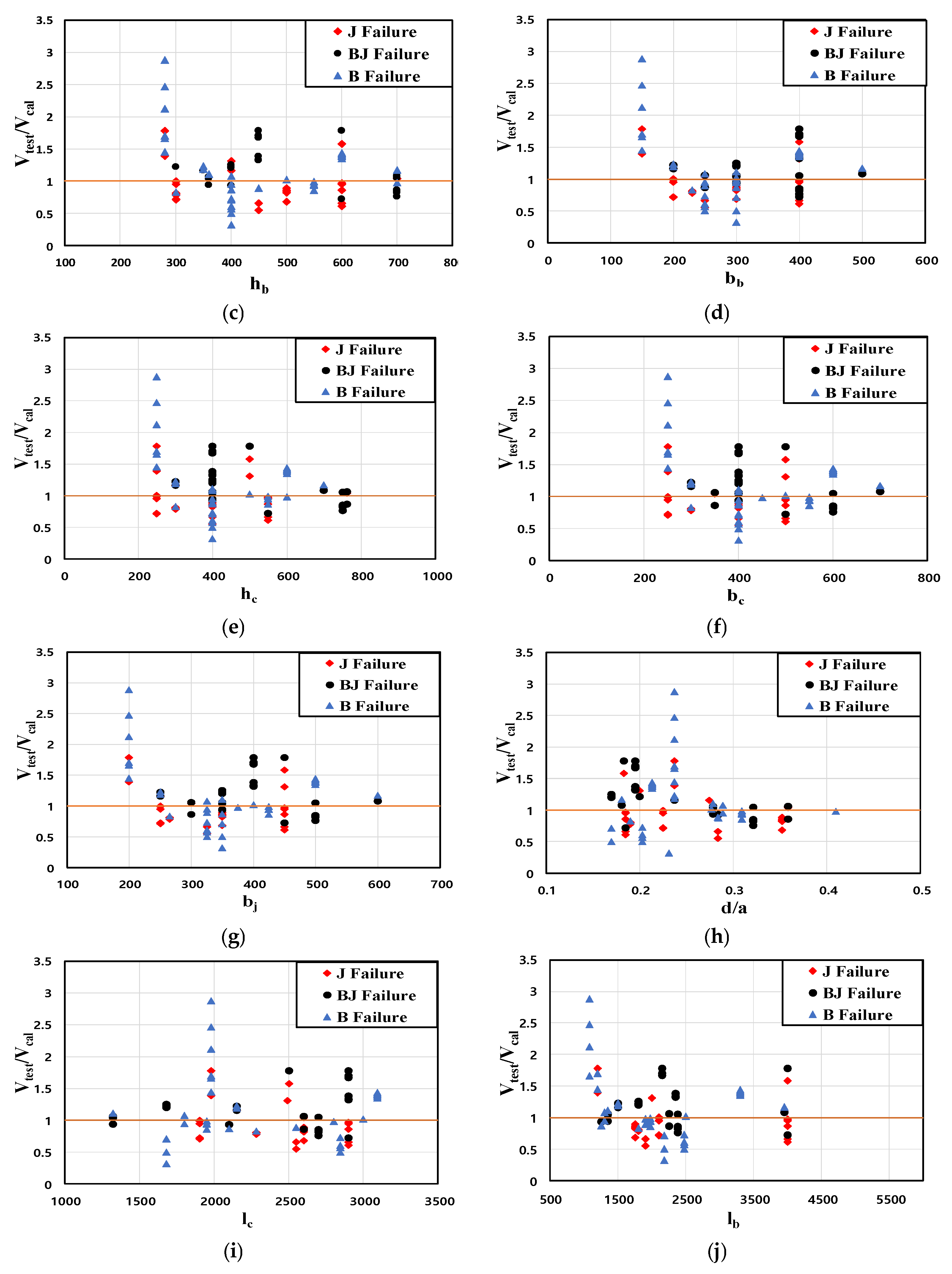

- The classification of failure modes based on variables related to cross-sectional dimensions (bc, hc, bb, hb, bj) was clearly evident. While no distinct trend in failure modes was observed for the cross-sectional elements of the column (bc, hc), the cross-sectional elements of the beam (hb, bb) showed a tendency for greater joint damage as the beam dimensions increased. This trend occurs because, as the beam cross-section decreases, the bending moment (Mb) in the beam cross-section also decreases. Consequently, the shear strength of the beam (Vjby) becomes smaller than the internal shear strength (Vj) at the joint, thereby reducing joint damage.

5. Conclusions

- Analysis of all 87 specimens using the Combined Model showed average Vtest/Vcal values of 1.12 for the Non-Prestressed group and 0.99 for the Prestressed group, demonstrating prediction performance close to actual test values for both groups. Notably, the shear strength evaluation accuracy was superior for specimens with prestressing, indicating that the Combined Model reasonably reflects the joint confinement effect.

- Analysis indicates that the cross-sectional element variable consistently exerts the greatest influence on both shear strength prediction and fracture mode classification. Therefore, incorporating the geometric characteristics of the joint when classifying the failure mode of the joint is deemed reasonable.

- For the reinforcement ratio (ρb), the Vtest/Vcal value tends to fall below 1 when using a high reinforcement ratio. The results indicate a potential for slight overestimation of the shear strength of members with high reinforcement ratios, necessitating caution during design.

- The influence of the cross-sectional properties of the column (bc, hc) and reinforcement ratio (ρb) on the failure mode determination was negligible. However, the study confirmed that as the cross-sectional properties of the beam (hb, bb) increased, the damage at the joint tended to increase. Furthermore, as the damage at the joint increased, the safety factor decreased. The shear strength of members with significant beam damage was evaluated quite conservatively.

- Overall, high accuracy was achieved in predicting shear strength. However, to enable more precise analysis and a safer joint design, supplementary research through additional literature collection is required, along with improvements to the shear strength evaluation model for PC beam-column joints.

- The Combined Model can be used as a supplementary shear strength evaluation method for PC beam–column joints, particularly for prestressed members. Caution is recommended for joints with large beam sections or high reinforcement ratios, where shear strength may be slightly overestimated.

- Future work should expand the experimental database and include cyclic loading effects to improve prediction reliability. In addition, further refinement is needed to support code-oriented application of the model for PC beam–column joint design.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lee, S.; Cha, H. A Study on Plans for Diffusion & Revitalization, and Developing Key Performance Indicator for OSC based PC Structure Apartment Housing. Korean J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2021, 22, 98–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, M.G.; Lee, U.H.; Kim Jin, S. A Study on the Applicability of OSC-Based PC Structure Apartment Housing Project. Archit. Inst. Korea 2023, 43, 614–615. [Google Scholar]

- Kurama, Y.C.; Sritharan, S.; Fleischman, R.B.; Restrepo, J.I.; Henry, R.S.; Cleland, N.M.; Ghosh, S.; Bonelli, P. Seismic-resistant precast concrete structures: State of the art. J. Struct. Eng. 2018, 144, 03118001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.-M. Off-Site Construction In Past, Present, and Future–Focused on case studies in the UK and Korea. Archit. Inst. Korea 2020, 40, 571–574. [Google Scholar]

- Yoo, J.-W.; Lee, J.-S. Structural System, Example and Future Development of Precast Concrete Housing. Archit. Inst. Korea 2020, 64, 39–44. [Google Scholar]

- Shin, D. Performance Defects and their Counter-Measures in Precast Concrete Structures. Mag. Korea Concr. Inst. 1994, 6, 16–22. [Google Scholar]

- Architectural Institute of Korea (AIK). Building Code Requirements for Precast Concrete and Commentary; Architectural Institute of Korea (AIK): Seoul, Republic of Korea, 1992; 137p. [Google Scholar]

- The Chosun Ilbo. South Korea’s Construction Industry Faces Graying Crisis. Available online: https://www.chosun.com/english/industry-en/2025/05/23/RYHHX5CSEFH6DBHAEY7D35J6Y4/ (accessed on 23 May 2025).

- Lee, J.-M. Trends in Revising and Enacting Codes and Standards to Boost Off-Site Construction in Developed Countries-Focusing on BPS 7014 & ICC 1200, 1205. J. Archit. Inst. Korea 2022, 38, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.-Y.; Byun, H.-W. Emulation Evaluation of Precast Concrete Structures. J. Korea Concr. Inst. 2022, 34, 633–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, F.; Deng, M.; Yang, Y. Experimental study on internal precast beam–column ultra-high-performance concrete connection and shear capacity of its joint. J. Build. Eng. 2021, 44, 103204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Zhang, Y.; Li, A.; Yang, T. Experimental study on a new type of precast beam-column joint. J. Build. Eng. 2022, 51, 104252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wada, A.; Sakata, H.; Nakano, K.; Matsuzaki, Y.; Tanabe, K.; Machida, S. Study on Damage Controlled Precast-Prestressed Concrete Structure with P/C Mild-Press-Joint-Part 1: Overview of P/C Mild-Press-Joint Building Construction and its Practical Applications. In Proceedings of the 2nd FIB Congress, Naples, Italy, 5–8 June 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, H.; Wu, J.; Guo, Z. Optimization and experimental study on seismic performance of precast dry-wet hybrid beam-column joint with local prestressing. Structures 2024, 65, 106703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Heo, J.; Lee, M.; Lee, D.; Ju, H. Assessment of beam-column joints in reinforced concrete and precast concrete structures based on CNN. Steel Compos. Struct. 2025, 57, 405–419. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Y.-H.; Kim, M.-S.; Jung, B.-N.; Kim, H.-C.; Kim, K.-S. Experimental Study on Structural Behavior of Joints for Precast Concrete Segment. J. Earthq. Eng. Soc. Korea 2009, 13, 59–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.-K.; Choi, Y.-C.; Choi, C.-S. Hysteretic behavior and seismic resistant capacity of precast concrete beam-to-column connections. J. Earthq. Eng. Soc. Korea 2010, 14, 61–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ACI Committee 318 (ACI 318-25); Building Code Requirements for Structural Concrete and Commentary. American Concrete Institute: Farmington Hills, MI, USA, 2025.

- ACI Committee 352 (ACI 352R-02); Recommendations for Design of Beam-Column Connections in Monolithic Reinforced Concrete Structures. American Concrete Institute: Farmington Hills, MI, USA, 2002.

- Birkeland, P.W.; Birkeland, H.W. Connections in precast concrete construction. J. Proc. 1966, 63, 345–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parastesh, H.; Hajirasouliha, I.; Ramezani, R. A new ductile moment-resisting connection for precast concrete frames in seismic regions: An experimental investigation. Eng. Struct. 2014, 70, 144–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, D.; Guo, Z.; Xiao, Q.; Zheng, Y. Experimental study of a new beam-to-column connection for precast concrete frames under reversal cyclic loading. Adv. Struct. Eng. 2016, 19, 529–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosoya, H.; Matsumoto, M.; Kanakubo, T.; Yasojima, A. Experimental study on structural performance of precast RC beam-column joints. Archit. Inst. Jpn. 2012, 18, 529–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, S.-S.; Kim, S.-H.; Lee, M.S.; Moon, J.-H. Performance evaluation of semi precast concrete beam-column connections with U-shaped strands. Adv. Struct. Eng. 2014, 17, 1585–1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Q.; Chen, T.; Xie, Z. Seismic experimental study on a precast concrete beam-column connection with grout sleeves. Eng. Struct. 2018, 155, 330–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.-J.; Hong, S.-G.; Lim, W.-Y. Seismic performance of precast concrete beam-column connections using ductile rod. J. Korea Concr. Inst. 2014, 26, 695–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Im, H.-J.; Park, H.-G.; Eom, T.-S.; Kang, S.-M. Earthquake resistance of beam-column connection of precast concrete U-shaped shell construction. J. Korea Concr. Inst. 2010, 22, 741–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masuda, Y.; Sugimoto, N. A study on mechanical behavior of joint-integrated precast beam-column connections (Precast Concrete). Proc. Jpn. Concr. Inst. 2008, 30, 571–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Qin, Y.; Xie, Y.; Yang, C. Seismic performance of a new precast concrete frame joint with a built-in disc spring. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 5334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Wang, S.; Meloni, M.; Feng, J.; Xu, J.; Cai, J. Experimental study on seismic behavior of precast beam-column connections under cyclic loading. Struct. Concr. 2021, 22, 1315–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Zhong, M.; Yang, S.; He, W.; Liu, W. Seismic performance study on novel precast concrete beam-to-beam connection with threaded sleeve. Structures 2024, 64, 106572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.-Y.; Han, X.-L.; Wang, X.; Cui, B.; Huang, G.-X.; Li, Z.-C.; Ji, J. Seismic behavior of precast concrete beam-column subassemblies with joint rebar couplers. Structures 2025, 79, 109553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, W.; Nishiyama, M.; Watanabe, F. Shear strength capacity of prestressed concrete beam-column joint focusing on tendon anchorage location. In Proceedings of the 13th World Conference on Earthquake Engineering, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 1–4 August 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.H.; Choi, S.-H.; Hwang, J.-H.; Jeong, H.; Han, S.-J.; Kim, K.S. Experimental study on lateral behavior of post-tensioned precast beam-column joints. Structures 2021, 33, 841–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamahara, M.; Nishiyama, M.; Okamoto, H.; Watanabe, F. Design for shear of prestressed concrete beam-column joint cores. J. Struct. Eng. 2007, 133, 1520–1530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Zhang, T.; Xu, W.; Du, D.; Zhang, Y. Experimental and numerical investigations on novel post-tensioned precast beam-to-column energy-dissipating connections. Structures 2023, 54, 117–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Restrepo, J.I.; Park, R.; Buchanan, A.H. Tests on connections of earthquake resisting precast reinforced concrete perimeter frames of buildings. PCI J. 1995, 40, 44–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.-S. Structural Behavior and Seismic Performance Evaluation of Precast Concrete Moment Frame Structures According to Beam-Column Joint Details of Thesis. Master’s Thesis, Yonsei University, Seoul, Republic of Korea.

| Author(s) | Specimens | ST | Joint Type | PS | fj,ck (MPa) | fb,ck (MPa) | lc (mm) | lb (mm) | hc (mm) | bc (mm) | hb (mm) | bb (mm) | d/a | ρb | Vj/Vjby | Vtest/Vcal | Failure Mode of the Specimen |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parastesh et al. [21] | BCT2 | PC | Ext | N-PS | 24 | 25 | 2900 | 2150 | 400 | 400 | 450 | 400 | 0.173 | 0.0081 | 2.56 | 1.67 | BJ Failure |

| BCT3 | PC | Ext | N-PS | 25 | 27 | 2900 | 2150 | 400 | 400 | 450 | 400 | 0.173 | 0.0079 | 2.61 | 1.78 | BJ Failure | |

| BCT4 | PC | Ext | N-PS | 23 | 22 | 2900 | 2150 | 400 | 400 | 450 | 400 | 0.173 | 0.0083 | 2.5 | 1.7 | BJ Failure | |

| BC2 | PC | Int | N-PS | 27 | 25 | 2900 | 2150 | 400 | 400 | 450 | 400 | 0.173 | 0.0081 | 2.01 | 1.33 | BJ Failure | |

| BC3 | PC | Int | N-PS | 25 | 27 | 2900 | 2150 | 400 | 400 | 450 | 400 | 0.173 | 0.0079 | 1.93 | 1.38 | BJ Failure | |

| BC4 | PC | Int | N-PS | 28 | 22 | 2900 | 2150 | 400 | 400 | 450 | 400 | 0.173 | 0.0083 | 2.04 | 1.32 | BJ Failure | |

| Guan et al. (2016) [22] | SP1 | PC | Int | N-PS | 34.2 | 41.4 | 1950 | 1700 | 550 | 550 | 550 | 300 | 0.162 | 0.0091 | 3.21 | 0.99 | B Failure |

| SP2 | PC | Int | N-PS | 34.2 | 41.4 | 1950 | 1700 | 550 | 550 | 550 | 300 | 0.162 | 0.0091 | 3.21 | 0.94 | B Failure | |

| SP3 | PC | Int | N-PS | 34.2 | 41.4 | 1950 | 1700 | 550 | 550 | 550 | 300 | 0.162 | 0.0091 | 3.21 | 0.95 | B Failure | |

| SP4 | PC | Int | N-PS | 34.2 | 41.4 | 1950 | 1700 | 550 | 550 | 550 | 300 | 0.162 | 0.0091 | 3.21 | 0.86 | B Failure | |

| Hosoya et al. (2012) [23] | No2 | PC | Int | N-PS | 77.1 | 57.4 | 1320 | 1150 | 400 | 400 | 360 | 300 | 0.227 | 0.0236 | 1.54 | 1.04 | BJ Failure |

| No3 | PC | Int | N-PS | 77.1 | 57.4 | 1320 | 1150 | 400 | 400 | 360 | 300 | 0.227 | 0.0236 | 1.54 | 1.06 | BJ Failure | |

| No4 | PC | Int | N-PS | 77.1 | 57.4 | 1320 | 1150 | 400 | 400 | 360 | 300 | 0.227 | 0.0236 | 1.54 | 1.06 | BJ Failure | |

| No6 | PC | Int | N-PS | 118.8 | 78.4 | 1320 | 1150 | 400 | 400 | 360 | 300 | 0.227 | 0.0317 | 1.39 | 0.94 | BJ Failure | |

| No8 | PC | Int | N-PS | 77.1 | 57.4 | 1320 | 1150 | 400 | 400 | 360 | 300 | 0.227 | 0.0236 | 1.54 | 1.11 | B Failure | |

| Ha et al. (2014) [24] | S3-1 | PC | Int | N-PS | 28.1 | 34.1 | 1680 | 1600 | 400 | 400 | 400 | 300 | 0.124 | 0.0231 | 1.35 | 1.2 | BJ Failure |

| S3-2 | PC | Int | N-PS | 28.1 | 34.1 | 1680 | 1600 | 400 | 400 | 400 | 300 | 0.124 | 0.0244 | 1.35 | 1.25 | BJ Failure | |

| S3-3 | PC | Int | N-PS | 28.1 | 34.1 | 1680 | 1600 | 400 | 400 | 400 | 300 | 0.124 | 0.0244 | 1.35 | 1.22 | BJ Failure | |

| S4-1 | PC | Ext | N-PS | 28.1 | 34.1 | 1680 | 2180 | 400 | 400 | 400 | 300 | 0.124 | 0.0244 | 1.32 | 0.5 | B Failure | |

| S4-2 | PC | Ext | N-PS | 28.1 | 34.1 | 1680 | 2180 | 400 | 400 | 400 | 300 | 0.124 | 0.0244 | 1.32 | 0.71 | B Failure | |

| B4-1 | PC | Ext | N-PS | 28.1 | 34.1 | 1680 | 2180 | 400 | 400 | 400 | 300 | 0.169 | 0.0251 | 0.97 | 0.32 | B Failure | |

| Yan et al. (2018) [25] | P1 | PC | Int | N-PS | 39.63 | 32.03 | 2150 | 1350 | 300 | 300 | 400 | 200 | 0.126 | 0.0062 | 2.82 | 1.16 | J Failure |

| P2 | PC | Int | N-PS | 39.63 | 32.03 | 2150 | 1350 | 300 | 300 | 350 | 200 | 0.126 | 0.0059 | 3.07 | 1.16 | BJ Failure | |

| P3 | PC | Int | N-PS | 39.63 | 32.03 | 2150 | 1350 | 300 | 300 | 300 | 200 | 0.126 | 0.006 | 3.28 | 1.22 | BJ Failure | |

| P4 | PC | Int | N-PS | 39.63 | 32.03 | 2150 | 1350 | 300 | 300 | 350 | 200 | 0.126 | 0.0059 | 3.07 | 1.23 | B Failure | |

| P5 | PC | Int | N-PS | 39.63 | 32.03 | 2150 | 1350 | 300 | 300 | 350 | 200 | 0.126 | 0.0059 | 3.07 | 1.19 | B Failure | |

| Lee et al. (2014) [26] | PCBC1 | PC | Int | N-PS | 35.2 | 35.2 | 2600 | 1869 | 762 | 350 | 700 | 250 | 0.118 | 0.0158 | 2.28 | 1.04 | J Failure |

| PCBC2 | PC | Int | N-PS | 35.2 | 35.5 | 2600 | 1869 | 762 | 350 | 700 | 250 | 0.118 | 0.0157 | 2.3 | 1.06 | BJ Failure | |

| PCBC3 | PC | Int | N-PS | 36.5 | 36.5 | 2600 | 1869 | 762 | 350 | 700 | 250 | 0.118 | 0.0157 | 2.33 | 0.86 | BJ Failure | |

| Im et al. (2010) [27] | SP1 | PC | Int | N-PS | 34.9 | 35.1 | 2700 | 2006 | 750 | 600 | 700 | 400 | 0.172 | 0.0262 | 1.15 | 0.84 | BJ Failure |

| SP2 | PC | Int | N-PS | 34.9 | 35.1 | 2700 | 2006 | 750 | 600 | 700 | 400 | 0.172 | 0.0262 | 1.15 | 0.82 | BJ Failure | |

| SP3 | PC | Int | N-PS | 34.9 | 35.1 | 2700 | 2006 | 750 | 600 | 700 | 400 | 0.172 | 0.0262 | 1.15 | 0.85 | BJ Failure | |

| SP4 | PC | Int | N-PS | 34.9 | 35.1 | 2700 | 2006 | 750 | 600 | 700 | 400 | 0.172 | 0.0262 | 1.15 | 0.76 | BJ Failure | |

| SP5 | PC | Int | N-PS | 34.9 | 35.1 | 2700 | 2006 | 750 | 600 | 700 | 400 | 0.172 | 0.0262 | 1.15 | 1.05 | BJ Failure | |

| Masuda and Sugimoto (2008) [28] | LRV1-N | PC | Ext | N-PS | 52.9 | 44.6 | 2100 | 1250 | 400 | 400 | 400 | 300 | 0.204 | 0.022 | 1.45 | 0.93 | BJ Failure |

| LRV2-N | PC | Ext | N-PS | 54.3 | 45.4 | 2100 | 1250 | 400 | 400 | 400 | 300 | 0.204 | 0.0219 | 1.47 | 0.87 | B Failure | |

| Chen et al. (2023) [29] | EPC2 | PC | Ext | N-PS | 35.2 | 35.2 | 1980 | 1075 | 250 | 250 | 280 | 150 | 0.117 | 0.0144 | 2.09 | 1.66 | B Failure |

| EPC4 | PC | Ext | N-PS | 35.2 | 35.2 | 1980 | 1075 | 250 | 250 | 280 | 150 | 0.117 | 0.0144 | 2.09 | 2.47 | B Failure | |

| EPCD2 | PC | Ext | N-PS | 35.2 | 35.2 | 1980 | 1075 | 250 | 250 | 280 | 150 | 0.117 | 0.0144 | 2.09 | 2.12 | B Failure | |

| EPCD4 | PC | Ext | N-PS | 35.2 | 35.2 | 1980 | 1075 | 250 | 250 | 280 | 150 | 0.117 | 0.0144 | 2.09 | 2.88 | B Failure | |

| IPC2 | PC | Int | N-PS | 35.2 | 35.2 | 1980 | 1075 | 250 | 250 | 280 | 150 | 0.117 | 0.0144 | 1.58 | 1.45 | B Failure | |

| IPC4 | PC | Int | N-PS | 35.2 | 35.2 | 1980 | 1075 | 250 | 250 | 280 | 150 | 0.117 | 0.0144 | 1.58 | 1.7 | B Failure | |

| IPCD2 | PC | Int | N-PS | 35.2 | 35.2 | 1980 | 1075 | 250 | 250 | 280 | 150 | 0.117 | 0.0144 | 1.58 | 1.39 | J Failure | |

| IPCD4 | PC | Int | N-PS | 35.2 | 35.2 | 1980 | 1075 | 250 | 250 | 280 | 150 | 0.117 | 0.0144 | 1.58 | 1.78 | J Failure | |

| Zhang et al. (2021) [30] | PJ1 | PC | Int | N-PS | 45.9 | 40 | 2550 | 1700 | 400 | 400 | 450 | 250 | 0.15 | 0.0097 | 2.07 | 0.89 | B Failure |

| PJ2 | PC | Int | N-PS | 45.9 | 40 | 2550 | 1700 | 400 | 400 | 450 | 250 | 0.15 | 0.0209 | 1.09 | 0.66 | J Failure | |

| PJ3 | PC | Int | N-PS | 45.9 | 40 | 2550 | 1700 | 400 | 400 | 450 | 250 | 0.15 | 0.0209 | 1.09 | 0.55 | J Failure | |

| Liu et al. (2024) [31] | PCCT | PC | Ext | N-PS | 33.9 | 33.9 | 1800 | 1300 | 400 | 400 | 400 | 250 | 0.174 | 0.0078 | 3.89 | 1.08 | B Failure |

| PCTO | PC | Ext | N-PS | 33.9 | 33.9 | 1800 | 1300 | 400 | 400 | 400 | 250 | 0.174 | 0.0089 | 3.8 | 0.95 | B Failure | |

| Chen et al. (2025) [32] | PC2 | PC | Int | N-PS | 55.6 | 55.6 | 2600 | 1550 | 400 | 400 | 500 | 300 | 0.204 | 0.0305 | 0.74 | 0.82 | J Failure |

| PC3 | PC | Int | N-PS | 66.4 | 66.4 | 2600 | 1550 | 400 | 400 | 500 | 300 | 0.204 | 0.0293 | 0.81 | 0.68 | J Failure | |

| PC4 | PC | Int | N-PS | 55.6 | 55.6 | 2600 | 1550 | 400 | 400 | 500 | 300 | 0.204 | 0.0305 | 0.74 | 0.84 | J Failure | |

| PC5 | PC | Int | N-PS | 55.6 | 55.6 | 2600 | 1550 | 400 | 400 | 500 | 300 | 0.204 | 0.0305 | 0.74 | 0.89 | J Failure | |

| PC6 | PC | Int | N-PS | 55.6 | 55.6 | 2600 | 1550 | 400 | 400 | 500 | 300 | 0.204 | 0.0305 | 0.74 | 0.86 | J Failure | |

| Yang et al. (2024) [14] | SP-1 | PC | Int | PS | 44.7 | 44.7 | 3095 | 3000 | 600 | 600 | 600 | 400 | 0.139 | 0.0067 | 3.43 | 1.44 | B Failure |

| SP-2 | PC | Int | PS | 40 | 40 | 3095 | 3000 | 600 | 600 | 600 | 400 | 0.139 | 0.007 | 3.46 | 1.42 | B Failure | |

| SP-3 | PC | Int | PS | 47.3 | 47.3 | 3095 | 3000 | 600 | 600 | 600 | 400 | 0.139 | 0.0065 | 3.37 | 1.35 | B Failure | |

| SP-4 | PC | Int | PS | 41.7 | 41.7 | 3095 | 3000 | 600 | 600 | 600 | 400 | 0.139 | 0.0069 | 3.32 | 1.4 | B Failure | |

| PC-1 | PC | Int | PS | 44.3 | 44.3 | 3095 | 3000 | 600 | 600 | 600 | 400 | 0.139 | 0.0067 | 3.41 | 1.38 | B Failure | |

| Ma et al. (2021) [11] | RUJ-2 | PC | Int | N-PS | 86.48 | 35.2 | 2280 | 1650 | 300 | 300 | 300 | 230 | 0.142 | 0.0103 | 2.55 | 0.83 | B Failure |

| RUJ-3 | PC | Int | N-PS | 86.48 | 35.2 | 2280 | 1650 | 300 | 300 | 300 | 230 | 0.142 | 0.0276 | 1.2 | 0.81 | J Failure | |

| RUJ-4 | PC | Int | N-PS | 86.48 | 35.2 | 2280 | 1650 | 300 | 300 | 300 | 230 | 0.142 | 0.0276 | 1.23 | 0.78 | J Failure | |

| RUJ-5 | PC | Int | N-PS | 86.48 | 35.2 | 2280 | 1650 | 300 | 300 | 300 | 230 | 0.142 | 0.0276 | 1.2 | 0.8 | J Failure | |

| RUJ-6 | PC | Int | N-PS | 86.48 | 35.2 | 2280 | 1650 | 300 | 300 | 300 | 230 | 0.142 | 0.0276 | 1.2 | 0.83 | B Failure | |

| Yue et al. (2004) [33] | KPC1-1 | PC | Ext | PS | 30 | 30 | 1900 | 2100 | 250 | 250 | 300 | 200 | 0.142 | 0.0259 | 0.5 | 0.99 | J Failure |

| KPC1-2 | PC | Ext | PS | 30 | 30 | 1900 | 2100 | 250 | 250 | 300 | 200 | 0.142 | 0.0265 | 0.5 | 0.95 | J Failure | |

| KPC2-1 | PC | Ext | PS | 30 | 30 | 1900 | 2100 | 250 | 250 | 300 | 200 | 0.142 | 0.0154 | 0.45 | 0.72 | J Failure | |

| KPC2-2 | PC | Ext | PS | 30 | 30 | 1900 | 2100 | 250 | 250 | 300 | 200 | 0.142 | 0.016 | 0.46 | 0.71 | J Failure | |

| KPC2-3 | PC | Ext | PS | 30 | 30 | 1900 | 2100 | 250 | 250 | 300 | 200 | 0.142 | 0.0154 | 0.45 | 0.71 | J Failure | |

| KPC3 | PC | Ext | PS | 30 | 30 | 1900 | 2100 | 250 | 250 | 300 | 200 | 0.142 | 0.0142 | 0.43 | 1 | J Failure | |

| Kim et al. (2021) [34] | NMUP | PC | Int | PS | 41.9 | 34.1 | 3545 | 3600 | 700 | 700 | 700 | 500 | 0.125 | 0.0091 | 2.57 | 1.17 | B Failure |

| NMOP | PC | Int | PS | 41.9 | 34.1 | 3545 | 3600 | 700 | 700 | 700 | 500 | 0.125 | 0.0058 | 3.52 | 1.08 | BJ Failure | |

| Hamahara et al. (2007) [35] | A-PC1 | PC | Ext | PS | 23.5 | 23.5 | 2500 | 4000 | 500 | 500 | 600 | 400 | 0.116 | 0.0495 | 0.4 | 1.58 | J Failure |

| A-PC2 | PC | Ext | PS | 23.9 | 23.9 | 2500 | 4000 | 500 | 500 | 600 | 400 | 0.116 | 0.0497 | 0.4 | 1.78 | BJ Failure | |

| B-PC1 | PC | Ext | PS | 26.3 | 26.3 | 2900 | 4000 | 550 | 500 | 600 | 400 | 0.117 | 0.0438 | 0.48 | 0.86 | J Failure | |

| B-PC2 | PC | Ext | PS | 28.8 | 28.8 | 2900 | 4000 | 550 | 500 | 600 | 400 | 0.117 | 0.0446 | 0.49 | 0.95 | J Failure | |

| B-PC3 | PC | Ext | PS | 30.4 | 30.4 | 2900 | 4000 | 550 | 500 | 600 | 400 | 0.117 | 0.0451 | 0.5 | 0.97 | J Failure | |

| C-PC1 | PC | Ext | PS | 29.8 | 29.8 | 2900 | 4000 | 550 | 500 | 600 | 400 | 0.117 | 0.0331 | 0.6 | 0.61 | J Failure | |

| C-PC2 | PC | Ext | PS | 31 | 31 | 2900 | 4000 | 550 | 500 | 600 | 400 | 0.117 | 0.0332 | 0.59 | 0.72 | BJ Failure | |

| C-PC3 | PC | Ext | PS | 31.1 | 31.1 | 2900 | 4000 | 550 | 500 | 600 | 400 | 0.117 | 0.0332 | 0.6 | 0.66 | J Failure | |

| Wang et al. (2023) [36] | PTHC-1 | PC | Ext | PS | 41.22 | 41.22 | 2846 | 2475 | 400 | 400 | 400 | 250 | 0.123 | 0.015 | 1.71 | 0.5 | B Failure |

| PTHC-2 | PC | Ext | PS | 41.22 | 41.22 | 2846 | 2475 | 400 | 400 | 400 | 250 | 0.123 | 0.015 | 1.71 | 0.57 | B Failure | |

| PTHC-3 | PC | Ext | PS | 45.75 | 45.75 | 2846 | 2475 | 400 | 400 | 400 | 250 | 0.123 | 0.0146 | 1.79 | 0.61 | B Failure | |

| PTHC-4 | PC | Ext | PS | 46.55 | 46.55 | 2846 | 2475 | 400 | 400 | 400 | 250 | 0.123 | 0.0145 | 1.81 | 0.73 | B Failure | |

| Zhang et al. (2022) [12] | PJ | PC | Ext | N-PS | 37.8 | 37.8 | 3000 | 2500 | 500 | 500 | 500 | 300 | 0.159 | 0.0123 | 2.11 | 1.02 | B Failure |

| Restrepo et al. (1995) [37] | Unit6 | PC | Int | N-PS | 44 | 44 | 2800 | 1605 | 600 | 450 | 700 | 300 | 0.161 | 0.0073 | 3.29 | 0.98 | B Failure |

| Kim (2020) [38] | PCB | PC | Int | N-PS | 40 | 40 | 2490 | 1750 | 500 | 500 | 400 | 400 | 0.2 | 0.0085 | 2.18 | 1.31 | J Failure |

| fj,ck | fb,ck | hc | bc | hb | bb | bj | ρb | lc | lb | d/a | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Mpa) | (Mpa) | (mm) | (mm) | (mm) | (mm) | (mm) | (mm) | (mm) | |||

| Max | 118.8 | 78.4 | 762 | 700 | 700 | 700 | 600 | 0.0497 | 3545 | 4000 | 0.409 |

| Min | 23 | 22 | 250 | 280 | 280 | 250 | 200 | 0.0058 | 1320 | 1075 | 0.170 |

| Mean | 42.4 | 37.7 | 439.5 | 411.5 | 457.5 | 411.5 | 355.5 | 0.018 | 2363.9 | 2174.7 | 0.245 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Kim, D.; Ju, H. Shear Strength Evaluation of Precast Concrete Beam-Column Joints Considering Key Influencing Parameters. Sustainability 2026, 18, 468. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010468

Kim D, Ju H. Shear Strength Evaluation of Precast Concrete Beam-Column Joints Considering Key Influencing Parameters. Sustainability. 2026; 18(1):468. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010468

Chicago/Turabian StyleKim, Dongho, and Hyunjin Ju. 2026. "Shear Strength Evaluation of Precast Concrete Beam-Column Joints Considering Key Influencing Parameters" Sustainability 18, no. 1: 468. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010468

APA StyleKim, D., & Ju, H. (2026). Shear Strength Evaluation of Precast Concrete Beam-Column Joints Considering Key Influencing Parameters. Sustainability, 18(1), 468. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010468