Sector Coupling and Flexibility Measures in Distributed Renewable Energy Systems: A Comprehensive Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Scope of the Review

1.2. Outline

2. Distributed Energy Systems

2.1. Concept and Definition of Distributed Energy Systems

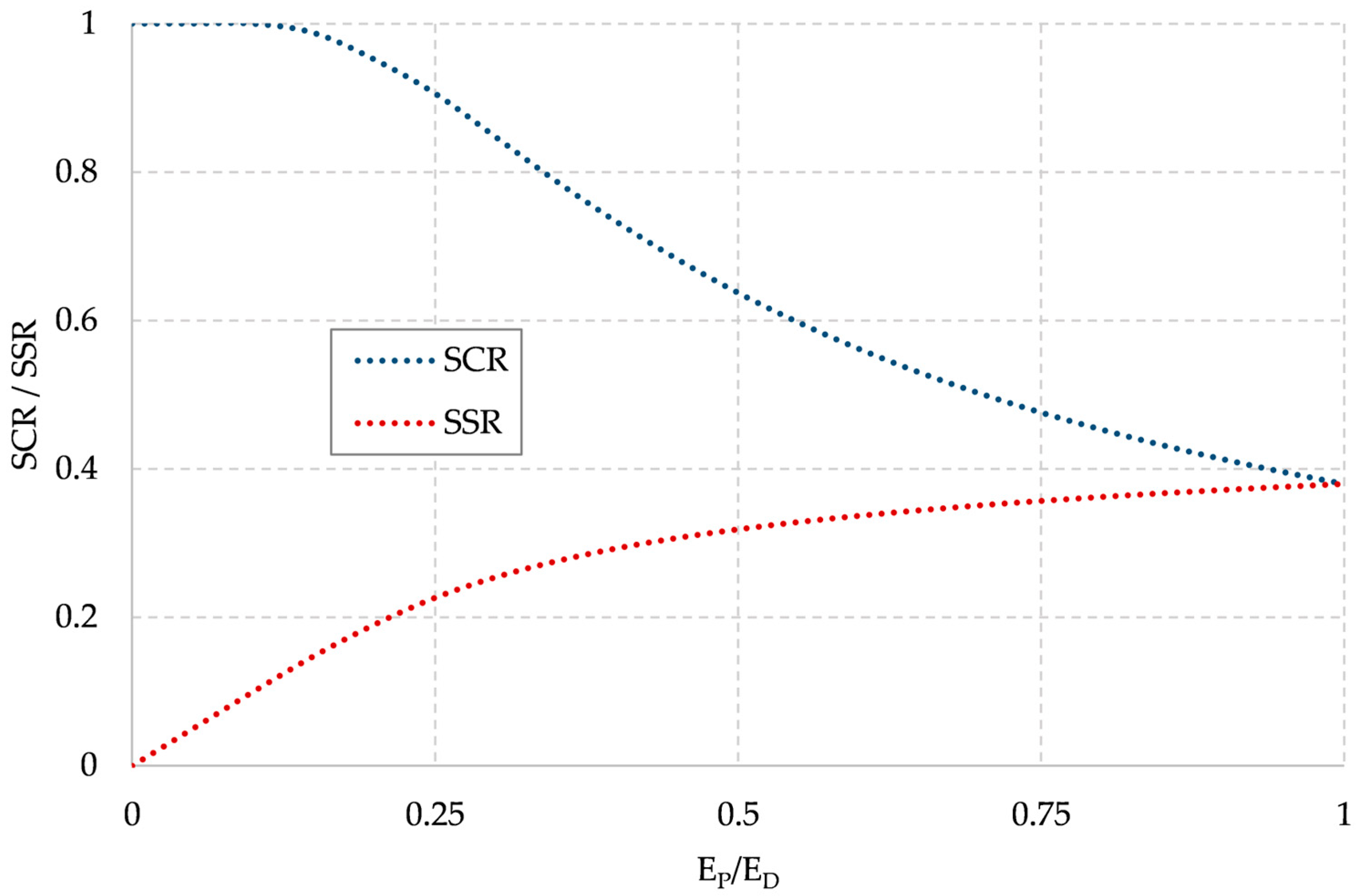

2.2. Energy Self-Consumption as a Necessity for Distributed Energy Systems

3. System Flexibility

- Demand-side flexibility: captures the ability of end-use loads to adjust their consumption patterns when exposed to economic or control signals, while maintaining acceptable levels of service and comfort for final users.

- Storage- and sector-coupling-based flexibility: denotes the capability of storage devices and cross-vector conversion technologies to decouple in time and carrier the balance between supply and demand by temporarily storing energy (in electrical, thermal or chemical form) or shifting it between vectors (e.g., Power-to-Heat, Power-to-X).

- Supply-side flexibility: denotes the capability of controllable generation and conversion units to vary their net power output over time in response to system needs, within their technical operating limits (ramping, minimum load, start-up time, efficiency).

4. Demand-Side Flexibility

- Load shedding: the temporary curtailment of non-critical demand during scarcity events.

- Load shifting: involves moving flexible uses from high-price or congested periods to off-peak hours.

- Load modulation: a short-term up- and down-regulation around a reference profile for balancing and ancillary services.

- On-site generation-driven flexibility: the adaptation of the demand to coincide with local RES generation.

5. Sector-Coupling Strategies and Energy Storage Systems

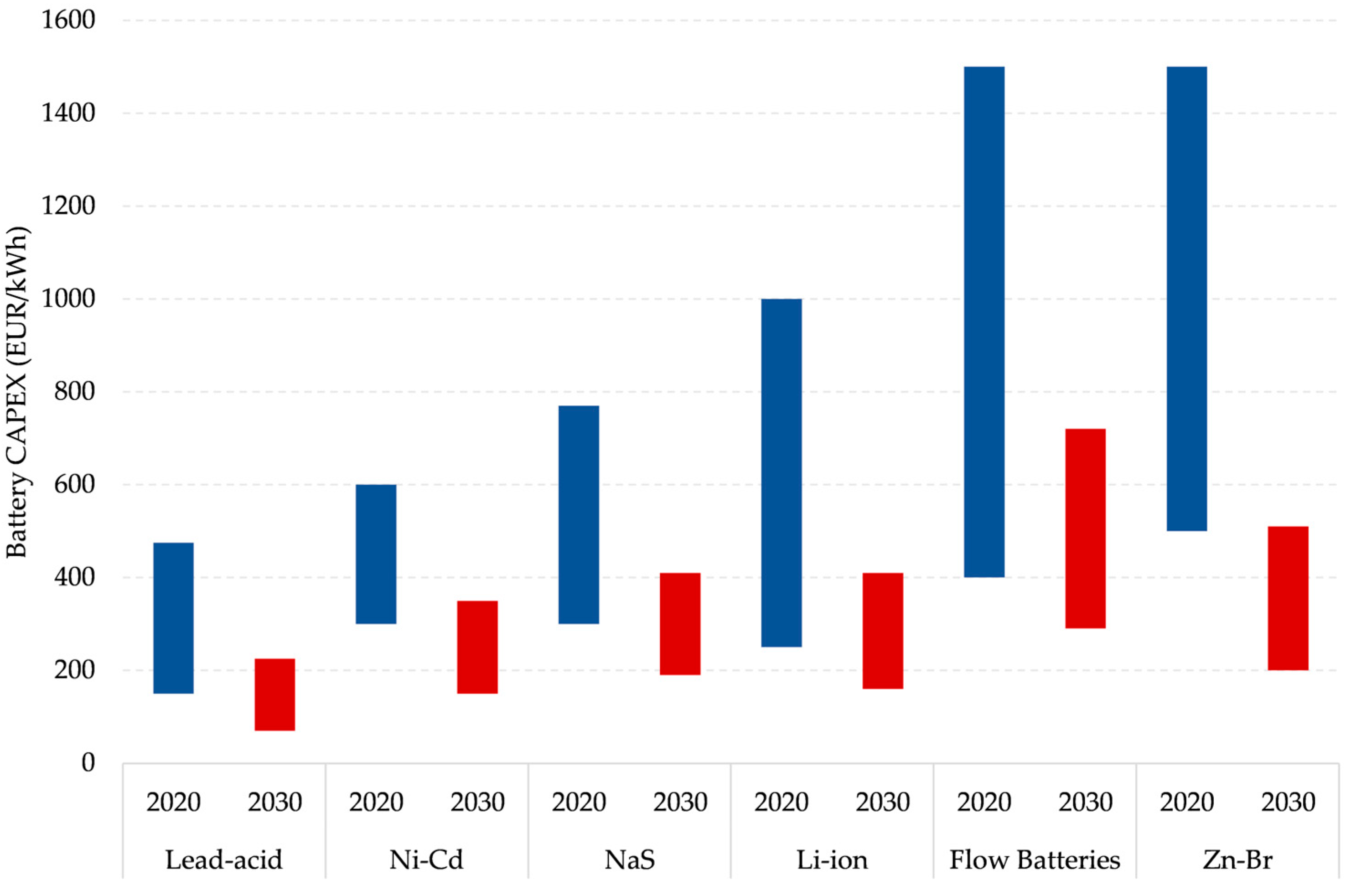

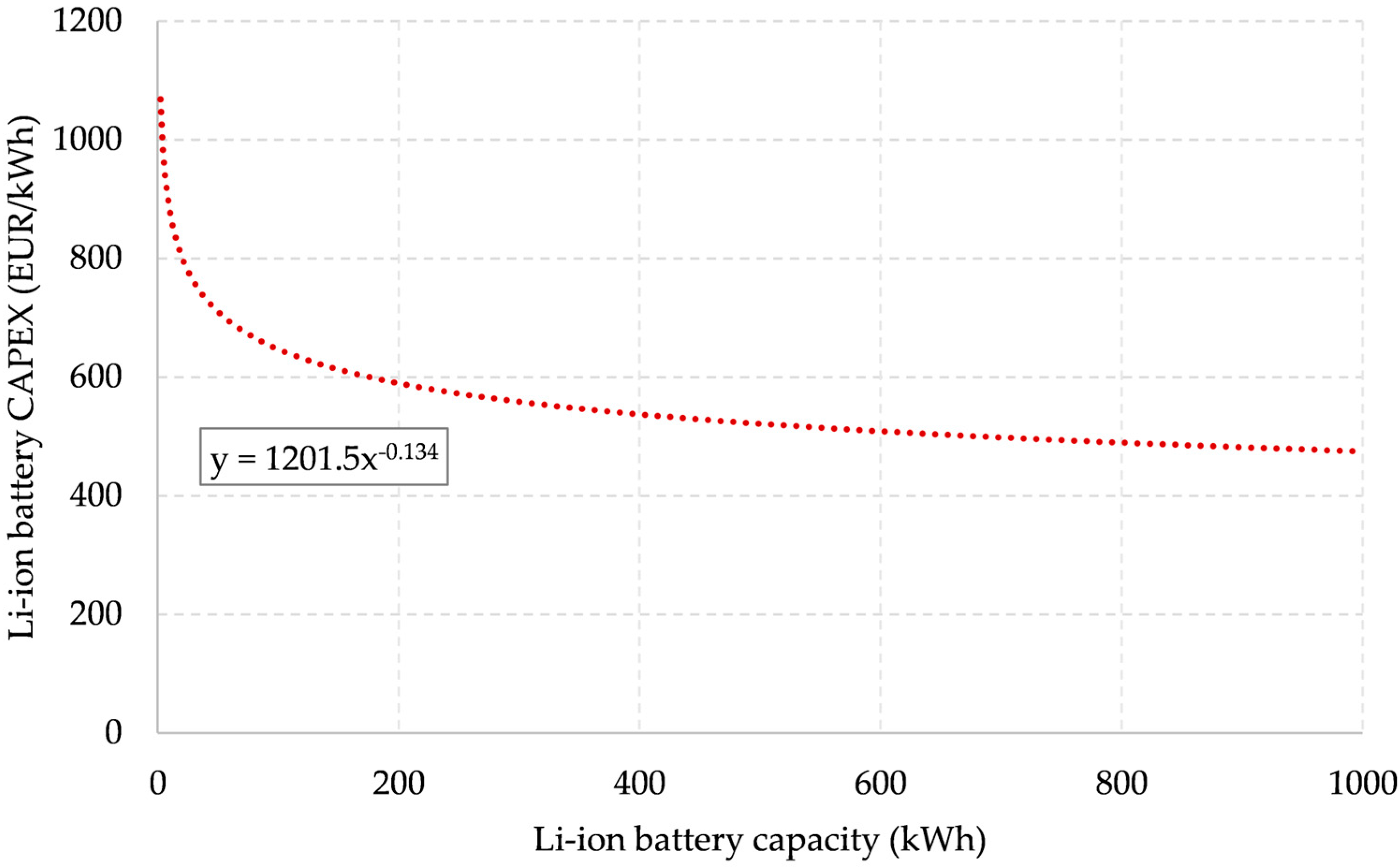

5.1. Electric Batteries

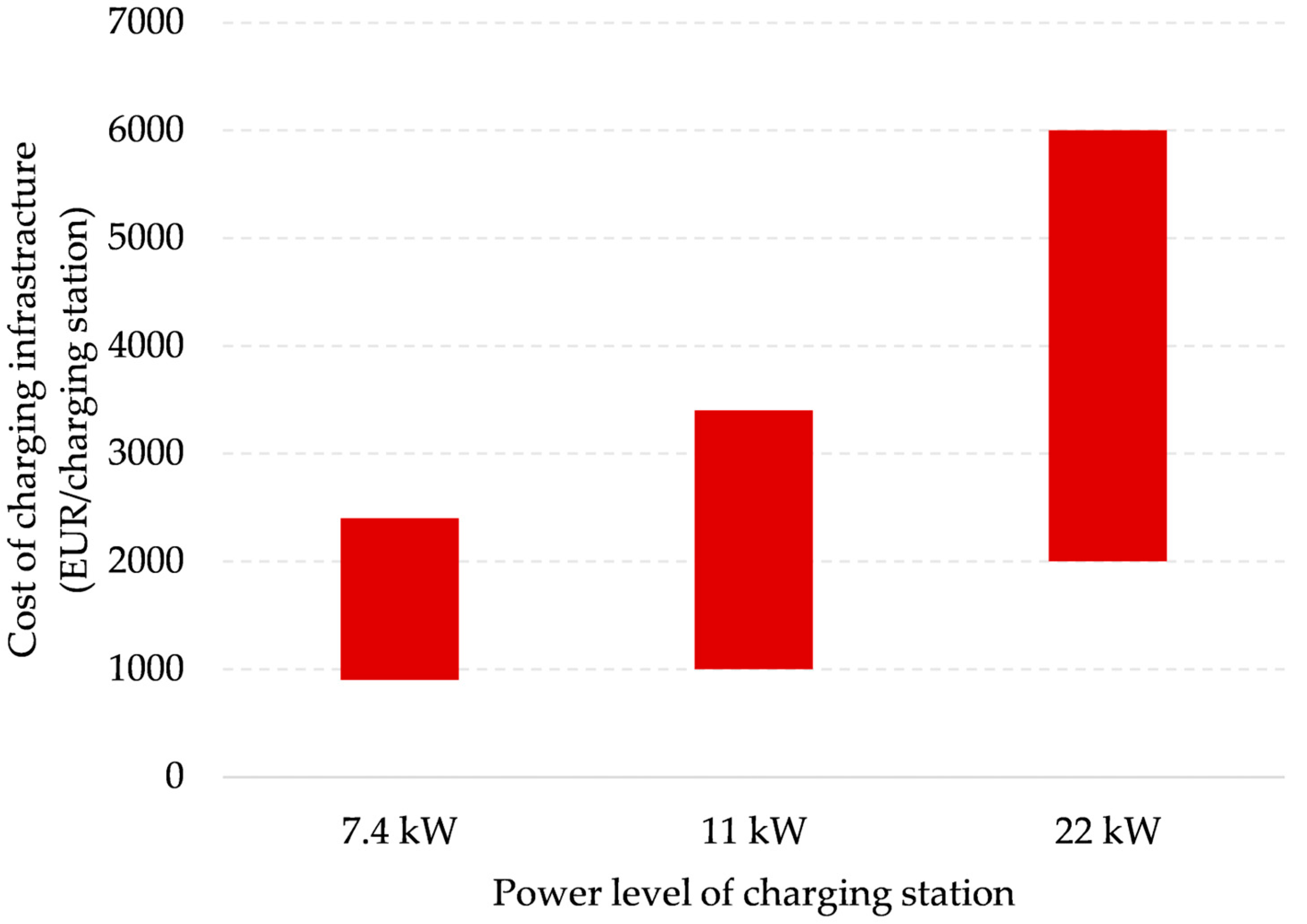

5.2. Power-to-Vehicle

- Uncoordinated charging;

- Smart charging;

- Smart charging and discharging, i.e., bidirectional vehicle-to-grid (V2G).

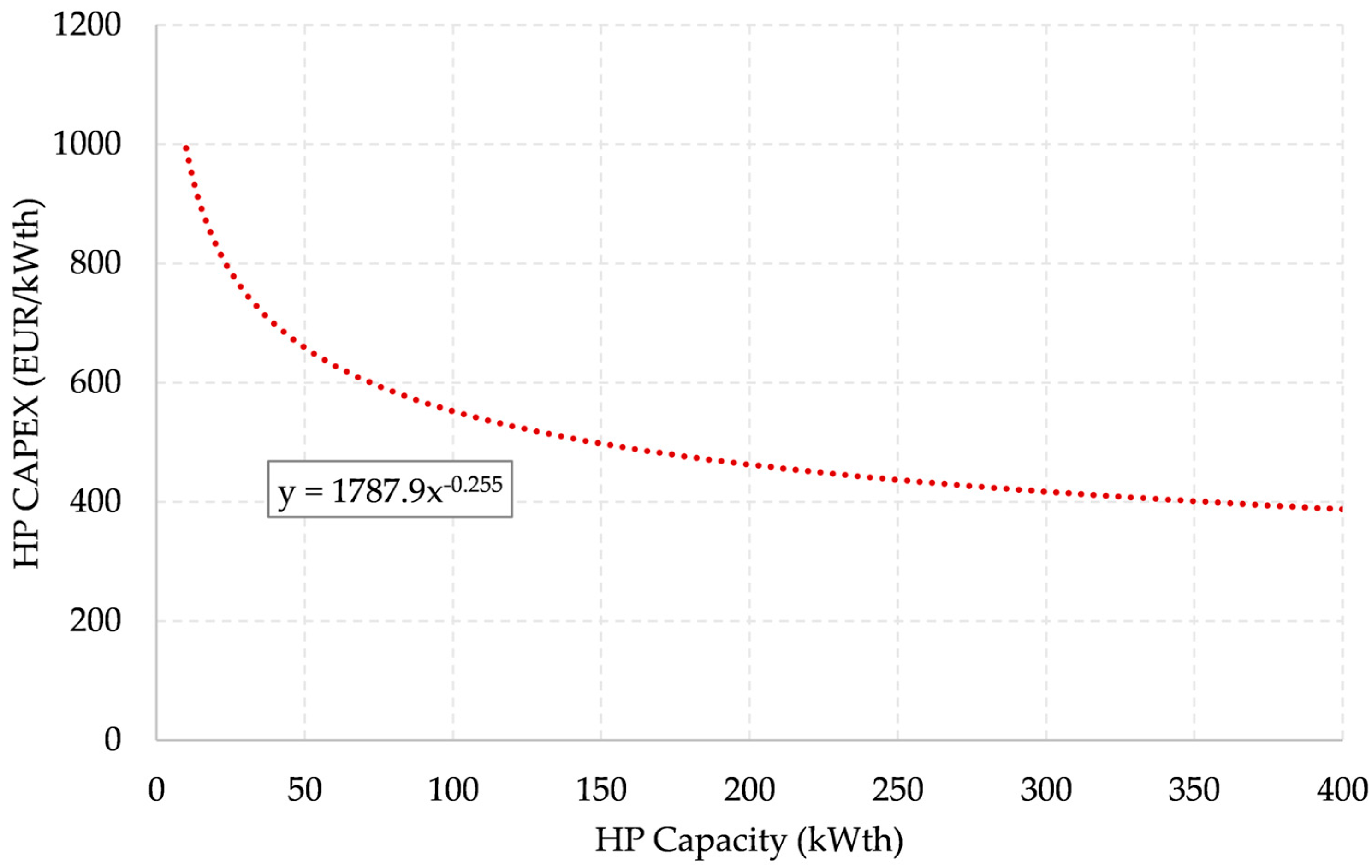

5.3. Power-to-Heat

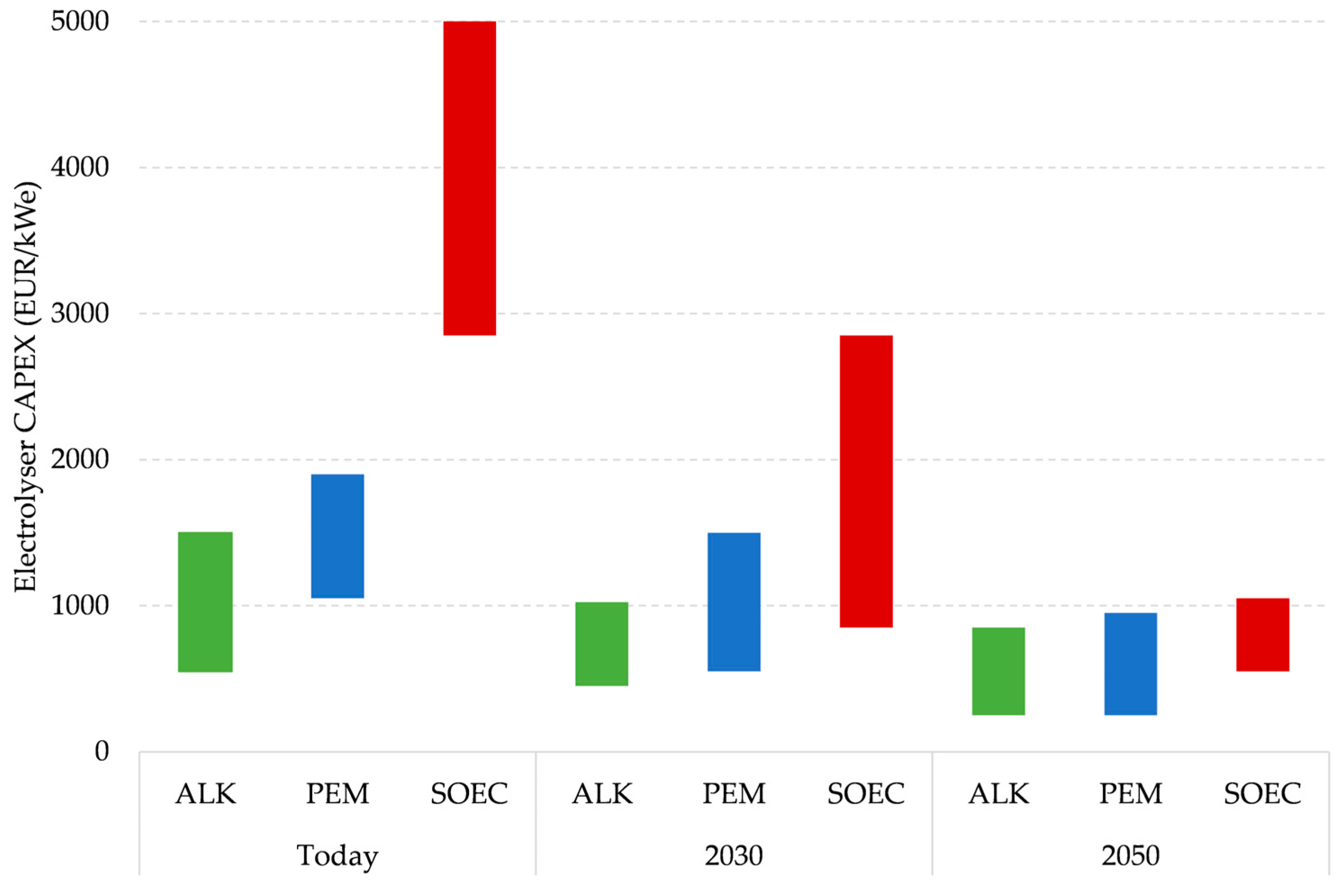

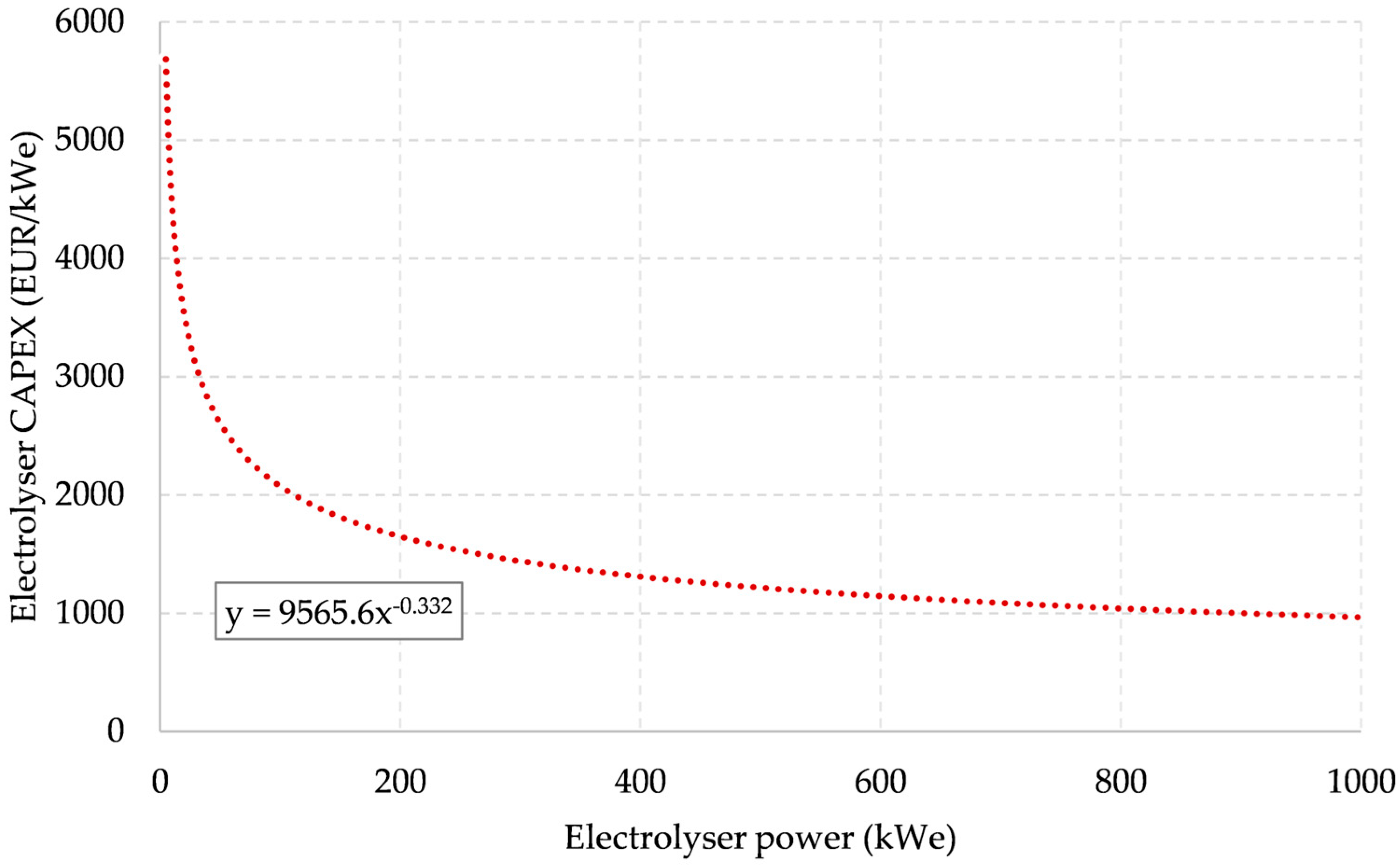

5.4. Power-to-X

6. Supply-Side Flexibility

7. New Energy Markets, Regulation and Blockchain Technology

8. Concluding Remarks and Research Gaps

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 4GDH | Fourth generation district heating |

| AEM | Anion exchange membrane |

| BOS | Balance of system |

| CAPEX | Capital expenditure |

| COP | Coefficient of performance |

| DES | Distributed energy systems |

| DHW | Domestic hot water |

| DME | Dimethyl ether |

| DOD | Depth of discharge |

| DSO | Distribution system operator |

| EES | Electrical energy storage |

| EPC | Engineering, procurement and construction |

| GHG | Greenhouse gas |

| H2 | Hydrogen |

| HP | Heat pump |

| IT | Information technology |

| IoT | Internet of Things |

| LCA | Life cycle assessment |

| LCOE | Levelised cost of electricity |

| LHV | Lower heating value |

| Li-ion | Lithium-ion |

| NA | Not available/not applicable |

| NG | Natural gas |

| Ni-Cd | Nickel–cadmium |

| Ni-MH | Nickel–metal hydride |

| O&M | Operation and maintenance |

| PEM | Proton exchange membrane |

| R&D | Research and development |

| SCR | Self-consumption ratio |

| SOEC | Solid oxide electrolysis cell |

| SSR | Self-sufficiency ratio |

| TES | Thermal energy storage |

| VRB | Vanadium redox battery |

| VRES | Variable renewable energy sources |

| YSZ | Yttria-stabilized zirconia |

| Zn-Br | Zinc–bromine |

References

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability; IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Climate Change 2022: Mitigation of Climate Change; IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Groppi, D.; Pastore, L.M.; Astiaso Garcia, D.; de Santoli, L. Analysing the Influence of Carbon Prices on Users’ Energy Cost and the Positive Impact of Renewable Energy Sources. J. Sustain. Dev. Energy Water Environ. Syst. 2025, 13, 1130582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connolly, D.; Lund, H.; Mathiesen, B.V. Smart Energy Europe: The Technical and Economic Impact of One Potential 100% Renewable Energy Scenario for the European Union. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 60, 1634–1653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuballa, M.L.; Abundo, M.L. A Review of the Development of Smart Grid Technologies. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 59, 710–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lund, H.; Østergaard, P.A.; Connolly, D.; Ridjan, I.; Mathiesen, B.V.; Hvelplund, F.; Thellufsen, J.Z.; Sorknses, P. Energy Storage and Smart Energy Systems. Int. J. Sustain. Energy Plan. Manag. 2016, 11, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastore, L.M.; de Santoli, L. Socio-Economic Implications of Implementing a Carbon-Neutral Energy System: A Green New Deal for Italy. Energy 2025, 322, 135682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lund, H.; Østergaard, P.A.; Connolly, D.; Mathiesen, B.V. Smart Energy and Smart Energy Systems. Energy 2017, 137, 556–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancarella, P. MES (Multi-Energy Systems): An Overview of Concepts and Evaluation Models. Energy 2014, 65, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Yan, J.; Jia, H.; Hatziargyriou, N.; Djilali, N.; Sun, H. Integrated Energy Systems. Appl. Energy 2016, 167, 155–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calise, F.; Cappiello, F.L.; Cimmino, L.; Dentice d’Accadia, M.; Vicidomini, M. Thermo-Economic Analysis and Dynamic Simulation of a Novel Layout of a Renewable Energy Community for an Existing Residential District in Italy. Energy Convers. Manag. 2024, 313, 118582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ackermann, T.; Andersson, G.; Söder, L. Distributed Generation: A Definition. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2001, 57, 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouffard, F.; Kirschen, D.S. Centralised and Distributed Electricity Systems. Energy Policy 2008, 36, 4504–4508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chicco, G.; Mancarella, P. Distributed Multi-Generation: A Comprehensive View. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2009, 13, 535–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Union. EC Directive (EU) 2018/2001 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 11 December 2018 on the Promotion of the Use of Energy from Renewable Sources. Off. J. Eur. Union 2018, L 328, 82–209. [Google Scholar]

- Martinot, E. Grid Integration of Renewable Energy: Flexibility, Innovation, and Experience. Annu. Rev. Env. Resour. 2016, 41, 223–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Climate Change 2014 Mitigation of Climate Change; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2014; ISBN 9781107058217. [Google Scholar]

- Merei, G.; Moshövel, J.; Magnor, D.; Sauer, D.U. Optimization of Self-Consumption and Techno-Economic Analysis of PV-Battery Systems in Commercial Applications. Appl. Energy 2016, 168, 171–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, L. A Review of Distributed Energy Systems: Technologies, Classification, and Applications. Sustainability 2025, 17, 1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bin Nadeem, T.; Siddiqui, M.; Khalid, M.; Asif, M. Distributed Energy Systems: A Review of Classification, Technologies, Applications, and Policies. Energy Strategy Rev. 2023, 48, 101096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Duan, L.; Liu, Q.; Du, X.; Zhao, C.; Wang, J.; Zheng, N.; Jiao, F.; Wang, L.; Sun, J.; et al. Progress and Prospects of Fundamental Research on Multi-Energy Complementary Distributed Energy System. Sci. China Technol. Sci. 2025, 68, 1900103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thellufsen, J.Z.; Lund, H.; Sorknæs, P.; Nielsen, S.; Chang, M.; Mathiesen, B.V. Beyond Sector Coupling: Utilizing Energy Grids in Sector Coupling to Improve the European Energy Transition. Smart Energy 2023, 12, 100116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, J.; Wang, J.; Ji, C.; Zhou, N. A Review of Regional Distributed Energy System Planning and Design. Int. J. Embed. Syst. 2021, 14, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Ouyang, L.; Xu, Y.; Zeng, R.; Kang, S.; Zhang, G. Current Status of Distributed Energy System in China. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 55, 288–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, F.; Wei, Z.; Zhai, X. A Review on the Integration and Optimization of Distributed Energy Systems. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 162, 112440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Mel, I.; Klymenko, O.V.; Short, M. Balancing Accuracy and Complexity in Optimisation Models of Distributed Energy Systems and Microgrids with Optimal Power Flow: A Review. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2022, 52, 102066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Słyś, D.; Stec, A.; Bednarz, K.; Ogarek, P.; Zeleňáková, M. Managing and Optimizing Hybrid Distributed Energy Systems: A Bibliometric Mapping of Current Knowledge and Strategies. Energies 2025, 18, 2497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Wirth, T.; Gislason, L.; Seidl, R. Distributed Energy Systems on a Neighborhood Scale: Reviewing Drivers of and Barriers to Social Acceptance. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 82, 2618–2628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cano-Martínez, J.; Quijano-López, A.; Fuster-Roig, V. A Scoping Review of Flexibility Markets in the Power Sector: Models, Mechanisms, and Business Perspectives. Energies 2025, 18, 5213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luthander, R.; Widén, J.; Nilsson, D.; Palm, J. Photovoltaic Self-Consumption in Buildings: A Review. Appl. Energy 2015, 142, 80–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallego-Castillo, C.; Heleno, M.; Victoria, M. Self-Consumption for Energy Communities in Spain: A Regional Analysis under the New Legal Framework. Energy Policy 2021, 150, 112144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todeschi, V.; Marocco, P.; Mutani, G.; Lanzini, A.; Santarelli, M. Towards Energy Self-Consumption and Self-Sufficiency in Urban Energy Communities. Int. J. Heat Technol. 2021, 39, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastore, L.M.; Basso, G.L.; Quarta, M.N. Power-to-Gas as an Option for Improving Energy Self-Consumption in Renewable Energy Communities. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2022, 47, 29604–29621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salman, U.T.; Shafiq, S.; Al-Ismail, F.S.; Khalid, M. A Review of Improvements in Power System Flexibility: Implementation, Operation and Economics. Electronics 2022, 11, 581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mladenov, V.; Chobanov, V.; Georgiev, A. Impact of Renewable Energy Sources on Power System Flexibility Requirements. Energies 2021, 14, 2813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahid, M.S.; Osonuga, S.; Twum-Duah, N.K.; Hodencq, S.; Delinchant, B.; Wurtz, F. An Assessment of Energy Flexibility Solutions from the Perspective of Low-Tech. Energies 2023, 16, 3298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo Piano, S.; Smith, S.T. Energy Demand and Its Temporal Flexibility: Approaches, Criticalities and Ways Forward. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 160, 112249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Møller Sneum, D. Barriers to Flexibility in the District Energy-Electricity System Interface—A Taxonomy. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 145, 111007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cochran, J.; Miller, M.; Zinaman, O.; Milligan, M.; Arent, D.; Palmintier, B.; O’Malley, M.; Mueller, S.; Lannoye, E.; Tuohy, A.; et al. Flexibility in 21st Century Power Systems; National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL): Golden, CO, USA, 2014; NREL/TP-6A20-61721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Energy Agency. The Power of Transformation; International Energy Agency (IEA): Paris, France, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Heggarty, T.; Bourmaud, J.Y.; Girard, R.; Kariniotakis, G. Quantifying Power System Flexibility Provision. Appl. Energy 2020, 279, 115852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, S.; Blaume, L.; Nilges, B. Quantifying the Operational Flexibility of Distributed Cross-Sectoral Energy Systems for the Integration of Volatile Renewable Electricity Generation. Energies 2023, 17, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.M.; Dadon, S.H.; He, M.; Giesselmann, M.; Hasan, M.M. An Overview of Power System Flexibility: High Renewable Energy Penetration Scenarios. Energies 2024, 17, 6393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gough, M.; Santos, S.F.; Javadi, M.; Castro, R.; Catalão, J.P.S. Prosumer Flexibility: A Comprehensive State-of-the-Art Review and Scientometric Analysis. Energies 2020, 13, 2710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Wang, Z.; Hong, T.; Piette, M.A. Energy Flexibility of Residential Buildings: A Systematic Review of Characterization and Quantification Methods and Applications. Adv. Appl. Energy 2021, 3, 100054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabot, C.; Villavicencio, M. The Demand-Side Flexibility in Liberalised Power Market: A Review of Current Market Design and Objectives. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2024, 201, 114643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Ettorre, F.; Banaei, M.; Ebrahimy, R.; Pourmousavi, S.A.; Blomgren, E.M.V.; Kowalski, J.; Bohdanowicz, Z.; Łopaciuk-Gonczaryk, B.; Biele, C.; Madsen, H. Exploiting Demand-Side Flexibility: State-of-the-Art, Open Issues and Social Perspective. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 165, 112605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panda, S.; Mohanty, S.; Rout, P.K.; Sahu, B.K.; Bajaj, M.; Zawbaa, H.M.; Kamel, S. Residential Demand Side Management Model, Optimization and Future Perspective: A Review. Energy Rep. 2022, 8, 3727–3766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousa, H.H.H.; Mahmoud, K.; Lehtonen, M. Recent Developments of Demand-side Management towards Flexible DER-rich Power Systems: A Systematic Review. IET Gener. Transm. Distrib. 2024, 18, 2259–2300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, D.Q.; Saavedra, O.R.; Santos-Pereira, K.; Pereira, J.D.F.; Cosme, D.S.; Veras, L.S.; Bento, R.G.; Riboldi, V.B. A Critical Review of Energy Storage Technologies for Microgrids. Energy Syst. 2025, 16, 1063–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, T.; Wang, Z.; Yao, N.; Zhang, M.; Bai, M.; Wang, Z.; Wang, X.; Cai, X.; Ma, Y. Technological Penetration and Carbon-Neutral Evaluation of Rechargeable Battery Systems for Large-Scale Energy Storage. J. Energy Storage 2023, 69, 107917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lund, H.; Andersen, A.N.; Østergaard, P.A.; Mathiesen, B.V.; Connolly, D. From Electricity Smart Grids to Smart Energy Systems—A Market Operation Based Approach and Understanding. Energy 2012, 42, 96–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Cong, T.N.; Yang, W.; Tan, C.; Li, Y.; Ding, Y. Progress in Electrical Energy Storage System: A Critical Review. Prog. Nat. Sci. 2009, 19, 291–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, H.L.; Garde, R.; Fulli, G.; Kling, W.; Lopes, J.P. Characterisation of Electrical Energy Storage Technologies. Energy 2013, 53, 288–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karabelli, D.; Singh, S.; Kiemel, S.; Koller, J.; Konarov, A.; Stubhan, F.; Miehe, R.; Weeber, M.; Bakenov, Z.; Birke, K.P. Sodium-Based Batteries: In Search of the Best Compromise Between Sustainability and Maximization of Electric Performance. Front. Energy Res. 2020, 8, 349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallo, A.B.; Simões-Moreira, J.R.; Costa, H.K.M.; Santos, M.M.; Moutinho dos Santos, E. Energy Storage in the Energy Transition Context: A Technology Review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 65, 800–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zubi, G.; Dufo-López, R.; Carvalho, M.; Pasaoglu, G. The Lithium-Ion Battery: State of the Art and Future Perspectives. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 89, 292–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, O.; Hawkes, A.; Gambhir, A.; Staffell, I. The Future Cost of Electrical Energy Storage Based on Experience Rates. Nat. Energy 2017, 2, 17110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soloveichik, G.L. Battery Technologies for Large-Scale Stationary Energy Storage. Annu. Rev. Chem. Biomol. Eng. 2011, 2, 503–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, C.K.; Bass, O.; Kothapalli, G.; Mahmoud, T.S.; Habibi, D. Overview of Energy Storage Systems in Distribution Networks: Placement, Sizing, Operation, and Power Quality. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 91, 1205–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parra, D.; Swierczynski, M.; Stroe, D.I.; Norman, S.A.; Abdon, A.; Worlitschek, J.; O’Doherty, T.; Rodrigues, L.; Gillott, M.; Zhang, X.; et al. An Interdisciplinary Review of Energy Storage for Communities: Challenges and Perspectives. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 79, 730–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lund, P.D.; Lindgren, J.; Mikkola, J.; Salpakari, J. Review of Energy System Flexibility Measures to Enable High Levels of Variable Renewable Electricity. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 45, 785–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IRENA. Electricity Storage and Renewables: Costs and Markets to 2030; International Renewable Energy Agency: Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 2017; ISBN 978-92-9260-038-9. [Google Scholar]

- Mulder, S.; Klein, S. Techno-Economic Comparison of Electricity Storage Options in a Fully Renewable Energy System. Energies 2024, 17, 1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zsiborács, H.; Hegedűsné Baranyai, N.; Zentkó, L.; Mórocz, A.; Pócs, I.; Máté, K.; Pintér, G. Electricity Market Challenges of Photovoltaic and Energy Storage Technologies in the European Union: Regulatory Challenges and Responses. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 1472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mongird, K.; Viswanathan, V.; Balducci, P.; Alam, J.; Fotedar, V.; Koritarov, V.; Hadjerioua, B. An Evaluation of Energy Storage Cost and Performance Characteristics. Energies 2020, 13, 3307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danish Energy Agency Technology Catalogues | The Danish Energy Agency 2024. Available online: https://ens.dk/en/analyses-and-statistics/technology-catalogues (accessed on 25 September 2025).

- Pastore, L.M.; Lo Basso, G.; Livio de Santoli, G.R. Synergies between Power-to-Heat and Power-to-Gas in Renewable Energy Communities. Renew. Energy 2022, 198, 1383–1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.M.; Oni, A.O.; Gemechu, E.; Kumar, A. Assessment of Energy Storage Technologies: A Review. Energy Convers. Manag. 2020, 223, 113295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sgaramella, A.; Pastore, L.M.; Lo Basso, G.; de Santoli, L. A Techno-Economic Analysis of Hydrogen Refuelling and Electric Fast-Charging Stations: Effects on Cost-Competitiveness of Zero-Emission Trucks. Energy 2025, 331, 137066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IRENA. World Energy Transitions Outlook 2022: 1.5 °C Pathway; International Renewable Energy Agency: Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Yong, J.Y.; Ramachandaramurthy, V.K.; Tan, K.M.; Mithulananthan, N. A Review on the State-of-the-Art Technologies of Electric Vehicle, Its Impacts and Prospects. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 49, 365–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, Y.W.; Khaki, B.; Chu, C.; Gadh, R. Electric Vehicle User Behavior Prediction Using Hybrid Kernel Density Estimator. In Proceedings of the 2018 International Conference on Probabilistic Methods Applied to Power Systems, PMAPS 2018—Proceedings, Boise, ID, USA, 24–28 June 2018; Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc.: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Hilton, G.; Kiaee, M.; Bryden, T.; Dimitrov, B.; Cruden, A.; Mortimer, A. A Stochastic Method for Prediction of the Power Demand at High Rate EV Chargers. IEEE Trans. Transp. Electrif. 2018, 4, 744–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buonomano, A.; Calise, F.; Cappiello, F.L.; Palombo, A.; Vicidomini, M. Dynamic Analysis of the Integration of Electric Vehicles in Efficient Buildings Fed by Renewables. Appl. Energy 2019, 245, 31–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorotić, H.; Doračić, B.; Dobravec, V.; Pukšec, T.; Krajačić, G.; Duić, N. Integration of Transport and Energy Sectors in Island Communities with 100% Intermittent Renewable Energy Sources. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2019, 99, 109–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sovacool, B.K.; Kester, J.; Noel, L.; Zarazua de Rubens, G. Actors, Business Models, and Innovation Activity Systems for Vehicle-to-Grid (V2G) Technology: A Comprehensive Review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2020, 131, 109963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Morais, H.; Sousa, T.; Lind, M. Electric Vehicle Fleet Management in Smart Grids: A Review of Services, Optimization and Control Aspects. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 56, 1207–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sevdari, K.; Calearo, L.; Andersen, P.B.; Marinelli, M. Ancillary Services and Electric Vehicles: An Overview from Charging Clusters and Chargers Technology Perspectives. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 167, 112666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heilmann, C.; Friedl, G. Factors Influencing the Economic Success of Grid-to-Vehicle and Vehicle-to-Grid Applications—A Review and Meta-Analysis. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 145, 111115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagaria, S.; van der Kam, M.; Boström, T. Vehicle-to-Grid Impact on Battery Degradation and Estimation of V2G Economic Compensation. Appl. Energy 2025, 377, 124546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mwasilu, F.; Justo, J.J.; Kim, E.K.; Do, T.D.; Jung, J.W. Electric Vehicles and Smart Grid Interaction: A Review on Vehicle to Grid and Renewable Energy Sources Integration. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2014, 34, 501–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astolfi, D.; Vasile, A.; Iuliano, S.; Pasetti, M. Recent Developments on the Incentives for Users’ to Participate in Vehicle-to-Grid Services. Energies 2024, 17, 5484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eltohamy, M.S.; Tawfiq, M.H.; Ahmed, M.M.R.; Alaas, Z.; Mohammed, B.; Ahmed, I.; Youssef, H.; Raouf, A. A Comprehensive Review of Vehicle-to-Grid V2G Technology: Technical, Economic, Regulatory, and Social Perspectives. Energy Convers. Manag. X 2025, 27, 101138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Wahedi, A.; Bicer, Y. Development of an Off-Grid Electrical Vehicle Charging Station Hybridized with Renewables Including Battery Cooling System and Multiple Energy Storage Units. Energy Rep. 2020, 6, 2006–2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanz, L.; Noll, B.; Schmidt, T.S.; Steffen, B. Comparing the Levelized Cost of Electric Vehicle Charging Options in Europe. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 5277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Autorità di Regolazione per Energia Reti e Ambiente (ARERA). Rapporto Finale Della Ricognizione: Mercato e Caratteristiche Dei Dispositivi Di Ricarica per i Veicoli Elettrici; ARERA: Roma, Italy, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Gjorgievski, V.Z.; Markovska, N.; Abazi, A.; Duić, N. The Potential of Power-to-Heat Demand Response to Improve the Flexibility of the Energy System: An Empirical Review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 138, 110489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, J.; Johnstone, C.; Torriti, J.; Leach, M. Discrete Demand Side Control Performance under Dynamic Building Simulation: A Heat Pump Application. Renew. Energy 2012, 39, 85–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, P.; Solé, C.; Castell, A.; Cabeza, L.F. The Use of Phase Change Materials in Domestic Heat Pump and Air-Conditioning Systems for Short Term Storage: A Review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2014, 39, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hesaraki, A.; Holmberg, S.; Haghighat, F. Seasonal Thermal Energy Storage with Heat Pumps and Low Temperatures in Building Projects—A Comparative Review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 43, 1199–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, D.; Madani, H. On Heat Pumps in Smart Grids: A Review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 70, 342–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soltani, M.; Kashkooli, F.M.; Dehghani-Sanij, A.R.; Kazemi, A.R.; Bordbar, N.; Farshchi, M.J.; Elmi, M.; Gharali, K.; Dusseault, M.B. A Comprehensive Study of Geothermal Heating and Cooling Systems. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2019, 44, 793–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloess, A.; Schill, W.P.; Zerrahn, A. Power-to-Heat for Renewable Energy Integration: A Review of Technologies, Modeling Approaches, and Flexibility Potentials. Appl. Energy 2018, 212, 1611–1626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thellufsen, J.Z.; Nielsen, S.; Lund, H. Implementing Cleaner Heating Solutions towards a Future Low-Carbon Scenario in Ireland. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 214, 377–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lund, H.; Werner, S.; Wiltshire, R.; Svendsen, S.; Thorsen, J.E.; Hvelplund, F.; Mathiesen, B.V. 4th Generation District Heating (4GDH). Integrating Smart Thermal Grids into Future Sustainable Energy Systems. Energy 2014, 68, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lund, H.; Østergaard, P.A.; Chang, M.; Werner, S.; Svendsen, S.; Sorknæs, P.; Thorsen, J.E.; Hvelplund, F.; Mortensen, B.O.G.; Mathiesen, B.V.; et al. The Status of 4th Generation District Heating: Research and Results. Energy 2018, 164, 147–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Li, H.; Svendsen, S. Evaluations of Different Domestic Hot Water Preparing Methods with Ultra-Low-Temperature District Heating. Energy 2016, 109, 248–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lund, H. Renewable Heating Strategies and Their Consequences for Storage and Grid Infrastructures Comparing a Smart Grid to a Smart Energy Systems Approach. Energy 2018, 151, 94–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorknæs, P.; Østergaard, P.A.; Thellufsen, J.Z.; Lund, H.; Nielsen, S.; Djørup, S.; Sperling, K. The Benefits of 4th Generation District Heating in a 100% Renewable Energy System. Energy 2020, 213, 119030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calise, F.; Cappiello, F.L.; Cimmino, L.; Cuomo, F.P.; Vicidomini, M. A 5th Generation District Heating Cooling Network Integrated with a Phase Change Material Thermal Energy Storage: A Dynamic Thermoeconomic Analysis. Appl. Energy 2025, 389, 125688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lund, H.; Østergaard, P.A.; Nielsen, T.B.; Werner, S.; Thorsen, J.E.; Gudmundsson, O.; Arabkoohsar, A.; Mathiesen, B.V. Perspectives on Fourth and Fifth Generation District Heating. Energy 2021, 227, 120520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pezzutto, S.; Zambotti, S.; Croce, S.; Zambelli, P.; Garegnani, G.; Scaramuzzino, C.; Pascuas, R.P.; Zubaryeva, A.; Haas, F.; Exner, D.; et al. Hotmaps Project, D2.3 WP2 Report—Open Data Set for the EU28; EURAC Research: Bolzano, Italy, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Lera, S.; Ballester, J.; Martínez-Lera, J. Analysis and Sizing of Thermal Energy Storage in Combined Heating, Cooling and Power Plants for Buildings. Appl. Energy 2013, 106, 127–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, J.D.; Camargo, M.; Commenge, J.M.; Falk, L.; Gil, I.D. Trends in Design of Distributed Energy Systems Using Hydrogen as Energy Vector: A Systematic Literature Review. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2019, 44, 9486–9504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathiesen, B.V.; Lund, H.; Connolly, D.; Wenzel, H.; Ostergaard, P.A.; Möller, B.; Nielsen, S.; Ridjan, I.; KarnOe, P.; Sperling, K.; et al. Smart Energy Systems for Coherent 100% Renewable Energy and Transport Solutions. Appl. Energy 2015, 145, 139–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stančin, H.; Mikulčić, H.; Wang, X.; Duić, N. A Review on Alternative Fuels in Future Energy System. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2020, 128, 109927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ababneh, H.; Hameed, B.H. Electrofuels as Emerging New Green Alternative Fuel: A Review of Recent Literature. Energy Convers. Manag. 2022, 254, 115213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wulf, C.; Zapp, P. Sustainability Assessment of Innovative Energy Technologies—Hydrogen from Wind Power as a Fuel for Mobility Applications. J. Sustain. Dev. Energy Water Environ. Syst. 2021, 9, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apostolou, D.; Enevoldsen, P.; Xydis, G. Supporting Green Urban Mobility—The Case of a Small-Scale Autonomous Hydrogen Refuelling Station. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2019, 44, 9675–9689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alavi, F.; Park Lee, E.; van de Wouw, N.; De Schutter, B.; Lukszo, Z. Fuel Cell Cars in a Microgrid for Synergies between Hydrogen and Electricity Networks. Appl. Energy 2017, 192, 296–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajanovic, A.; Haas, R. Prospects and Impediments for Hydrogen and Fuel Cell Vehicles in the Transport Sector. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2021, 46, 10049–10058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qadrdan, M.; Abeysekera, M.; Chaudry, M.; Wu, J.; Jenkins, N. Role of Power-to-Gas in an Integrated Gas and Electricity System in Great Britain. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2015, 40, 5763–5775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quarton, C.J.; Samsatli, S. Should We Inject Hydrogen into Gas Grids? Practicalities and Whole-System Value Chain Optimisation. Appl. Energy 2020, 275, 115172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calise, F.; Cappiello, F.L.; Cimmino, L.; Cutolo, L.; Vicidomini, M. Thermoeconomic Comparison of Alkaline, Solid Oxide and Anion Exchange Membrane Electrolyzers for Power-to-Gas Applications. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2025, 224, 116115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Götz, M.; Lefebvre, J.; Mörs, F.; McDaniel Koch, A.; Graf, F.; Bajohr, S.; Reimert, R.; Kolb, T. Renewable Power-to-Gas: A Technological and Economic Review. Renew. Energy 2016, 85, 1371–1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulleberg, Ø.; Nakken, T.; Eté, A. The Wind/Hydrogen Demonstration System at Utsira in Norway: Evaluation of System Performance Using Operational Data and Updated Hydrogen Energy System Modeling Tools. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2010, 35, 1841–1852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buttler, A.; Spliethoff, H. Current Status of Water Electrolysis for Energy Storage, Grid Balancing and Sector Coupling via Power-to-Gas and Power-to-Liquids: A Review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 82, 2440–2454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEA. The Future of Hydrogen; IEA: Paris, France, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Carmo, M.; Fritz, D.L.; Mergel, J.; Stolten, D. A Comprehensive Review on PEM Water Electrolysis. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2013, 38, 4901–4934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiva Kumar, S.; Himabindu, V. Hydrogen Production by PEM Water Electrolysis—A Review. Mater. Sci. Energy Technol. 2019, 2, 442–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gahleitner, G. Hydrogen from Renewable Electricity: An International Review of Power-to-Gas Pilot Plants for Stationary Applications. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2013, 38, 2039–2061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, K.; Zhang, D. Recent Progress in Alkaline Water Electrolysis for Hydrogen Production and Applications. Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 2010, 36, 307–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincent, I.; Bessarabov, D. Low Cost Hydrogen Production by Anion Exchange Membrane Electrolysis: A Review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 81, 1690–1704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavel, C.C.; Cecconi, F.; Emiliani, C.; Santiccioli, S.; Scaffidi, A.; Catanorchi, S.; Comotti, M. Highly Efficient Platinum Group Metal Free Based Membrane-Electrode Assembly for Anion Exchange Membrane Water Electrolysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 1378–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laguna-Bercero, M.A. Recent Advances in High Temperature Electrolysis Using Solid Oxide Fuel Cells: A Review. J. Power Sources 2012, 203, 4–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eveloy, V. Hybridization of Solid Oxide Electrolysis-Based Power-to-Methane with Oxyfuel Combustion and Carbon Dioxide Utilization for Energy Storage. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2019, 108, 550–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez, S.Y.; Hotza, D. Current Developments in Reversible Solid Oxide Fuel Cells. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 61, 155–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, O.; Gambhir, A.; Staffell, I.; Hawkes, A.; Nelson, J.; Few, S. Future Cost and Performance of Water Electrolysis: An Expert Elicitation Study. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2017, 42, 30470–30492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamagna, M.; Nastasi, B.; Groppi, D.; Rozain, C.; Manfren, M.; Astiaso Garcia, D. Techno-Economic Assessment of Reversible Solid Oxide Cell Integration to Renewable Energy Systems at Building and District Scale. Energy Convers. Manag. 2021, 235, 113993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, K.; Fang, J.; Ai, X.; Huang, D.; Zhong, Z.; Yang, X.; Wang, L. Comparative Study of Alkaline Water Electrolysis, Proton Exchange Membrane Water Electrolysis and Solid Oxide Electrolysis through Multiphysics Modeling. Appl. Energy 2022, 312, 118788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, M.M.; Al Mesfer, M.K.; Naseem, H.; Danish, M. Hydrogen Production by Water Electrolysis: A Review of Alkaline Water Electrolysis, PEM Water Electrolysis and High Temperature Water Electrolysis. Int. J. Eng. Adv. Technol. 2015, 4, 2249–8958. [Google Scholar]

- Böhm, H.; Zauner, A.; Rosenfeld, D.C.; Tichler, R. Projecting Cost Development for Future Large-Scale Power-to-Gas Implementations by Scaling Effects. Appl. Energy 2020, 264, 114780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proost, J. State-of-the Art CAPEX Data for Water Electrolysers, and Their Impact on Renewable Hydrogen Price Settings. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2019, 44, 4406–4413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UK Deparment of Business Energy & Industrial. Hydrogen Production Costs 2021; UK BEIS: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Loji, K.; Sharma, S.; Loji, N.; Sharma, G.; Bokoro, P.N. Operational Issues of Contemporary Distribution Systems: A Review on Recent and Emerging Concerns. Energies 2023, 16, 1732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salman, C.A.; Li, H.; Li, P.; Yan, J. Improve the Flexibility Provided by Combined Heat and Power Plants (CHPs)—A Review of Potential Technologies. e-Prime—Adv. Electr. Eng. Electron. Energy 2021, 1, 100023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.; Sun, Q.; Chen, L.; Chen, Q.; Zhao, T.; He, K.; Xu, F.; Min, Y.; Wang, S.; Zhou, G. Cogeneration Transition for Energy System Decarbonization: From Basic to Flexible and Complementary Multi-Energy Sources. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2023, 187, 113709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cappiello, F.L.; Erhart, T.G. Modular Cogeneration for Hospitals: A Novel Control Strategy and Optimal Design. Energy Convers. Manag. 2021, 237, 114131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuytten, T.; Claessens, B.; Paredis, K.; Van Bael, J.; Six, D. Flexibility of a Combined Heat and Power System with Thermal Energy Storage for District Heating. Appl. Energy 2013, 104, 583–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rong, A.; Lahdelma, R. Role of Polygeneration in Sustainable Energy System Development Challenges and Opportunities from Optimization Viewpoints. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 53, 363–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murugan, S.; Horák, B. Tri and Polygeneration Systems-A Review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 60, 1032–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maghanki, M.M.; Ghobadian, B.; Najafi, G.; Galogah, R.J. Micro Combined Heat and Power (MCHP) Technologies and Applications. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2013, 28, 510–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, S.; Michaux, G.; Salagnac, P.; Bouvier, J.-L. Micro-Combined Heat and Power Systems (Micro-CHP) Based on Renewable Energy Sources. Energy Convers. Manag. 2017, 154, 262–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastore, L.M.; Lo Basso, G.; de Santoli, L. How National Decarbonisation Scenarios Can Affect Building Refurbishment Strategies. Energy 2023, 283, 128634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montazerinejad, H.; Eicker, U. Recent Development of Heat and Power Generation Using Renewable Fuels: A Comprehensive Review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 165, 112578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calise, F.; Cappiello, F.L.; Cimmino, L.; Dentice d’Accadia, M.; Vicidomini, M. Dynamic Model of a Novel Power-to-Power Trigenerative System Based on Solid-State Hydrogen Storage: Real World Case Study for a Non-Residential User. Energy Convers. Manag. 2025, 342, 120115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arsalis, A. A Comprehensive Review of Fuel Cell-Based Micro-Combined-Heat-and-Power Systems. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2019, 105, 391–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.; Liu, M.; Mei, J.; Li, X.; Grigoriev, S.; Hasanien, H.M.; Tang, X.; Li, R.; Sun, C. Polarization Loss Decomposition-Based Online Health State Estimation for Proton Exchange Membrane Fuel Cells. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 157, 150162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, J.; Meng, X.; Tang, X.; Li, H.; Hasanien, H.; Alharbi, M.; Dong, Z.; Shen, J.; Sun, C.; Fan, F.; et al. An Accurate Parameter Estimation Method of the Voltage Model for Proton Exchange Membrane Fuel Cells. Energies 2024, 17, 2917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahid, Z.; Santarelli, M.; Marocco, P.; Ferrero, D.; Zahid, U. Techno-Economic Feasibility Analysis of Renewable-Fed Power-to-Power (P2P) Systems for Small French Islands. Energy Convers. Manag. 2022, 255, 115368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willems, B.; Zhou, J. The Clean Energy Package and Demand Response: Setting Correct Incentives. Energies 2020, 13, 5672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Li, K.; Xu, H.; Wang, F.; Zhou, Z.; Zhang, Y. Fundamentals and Business Model for Resource Aggregator of Demand Response in Electricity Markets. Energy 2020, 204, 117885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liebensteiner, M.; Haxhimusa, A.; Naumann, F. Subsidized Renewables’ Adverse Effect on Energy Storage and Carbon Pricing as a Potential Remedy. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2023, 171, 112990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blaschke, M.J. Dynamic Pricing of Electricity: Enabling Demand Response in Domestic Households. Energy Policy 2022, 164, 112878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pop, C.; Cioara, T.; Antal, M.; Anghel, I.; Salomie, I.; Bertoncini, M. Blockchain Based Decentralized Management of Demand Response Programs in Smart Energy Grids. Sensors 2018, 18, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andoni, M.; Robu, V.; Flynn, D.; Abram, S.; Geach, D.; Jenkins, D.; McCallum, P.; Peacock, A. Blockchain Technology in the Energy Sector: A Systematic Review of Challenges and Opportunities. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2019, 100, 143–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monrat, A.A.; Schelén, O.; Andersson, K. A Survey of Blockchain from the Perspectives of Applications, Challenges, and Opportunities. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 117134–117151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mengelkamp, E.; Notheisen, B.; Beer, C.; Dauer, D.; Weinhardt, C. A Blockchain-Based Smart Grid: Towards Sustainable Local Energy Markets. Comput. Sci.-Res. Dev. 2018, 33, 207–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esmat, A.; de Vos, M.; Ghiassi-Farrokhfal, Y.; Palensky, P.; Epema, D. A Novel Decentralized Platform for Peer-to-Peer Energy Trading Market with Blockchain Technology. Appl. Energy 2021, 282, 116123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lüth, A.; Zepter, J.M.; Crespo del Granado, P.; Egging, R. Local Electricity Market Designs for Peer-to-Peer Trading: The Role of Battery Flexibility. Appl. Energy 2018, 229, 1233–1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, T.; Soares, T.; Pinson, P.; Moret, F.; Baroche, T.; Sorin, E. Peer-to-Peer and Community-Based Markets: A Comprehensive Review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2019, 104, 367–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casino, F.; Dasaklis, T.K.; Patsakis, C. A Systematic Literature Review of Blockchain-Based Applications: Current Status, Classification and Open Issues. Telemat. Inform. 2019, 36, 55–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahl, A.; Yarime, M.; Tanaka, K.; Sagawa, D. Review of Blockchain-Based Distributed Energy: Implications for Institutional Development. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2019, 107, 200–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorknæs, P.; Lund, H.; Skov, I.R.; Djørup, S.; Skytte, K.; Morthorst, P.E.; Fausto, F. Smart Energy Markets—Future Electricity, Gas and Heating Markets. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2020, 119, 109655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Lead–Acid | Ni-Cd | NaS | Li-Ion | VRB | Zn-Br | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maturity | Mature | Commercial | Commercial | Commercial | Early Commercial | Demonstration |

| Power Capacity (kW) | 1–40,000 | 10–40,000 | 50–50,00 | 10–100,000 | 30–5000 | 50–2000 |

| Storage Capacity (kWh) | 100–100,000 | 0.01–1500 | 1000–100,000 | 0.01–100,000 | 10–10,000 | 50–4000 |

| Efficiency (%) | 70–90% | 60–75% | 70–90% | 85–95% | 60–85% | 60–75% |

| Response time (ms) | 5–10 ms | 1–10 ms | 1 ms | >20 ms | <1 ms | <1 ms |

| Self-discharge rate (%/day) | 0.033–0.3 | 0.067–0.6 | 0.05–20 | 0.1–0.3 | 0.2 | 0.24 |

| Suitable storage duration | min − days | min − days | s − h | min − days | h − months | h − months |

| Lifetime (years) | 5–15 | 10–20 | 10–15 | 5–15 | 5–10 | 5–10 |

| Lifetime (cycles at 80% DOD) | 400–2000 | 2000–3500 | 2500–4500 | 2000–10,000 | 10,000–13,000 | 2000–10,000 |

| Alkaline | PEM | AEM | SOEC | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Electrolyte | Alkaline solution | Solid polymer membrane | Polymeric anion exchange membranes | ZrO2 ceramic doped with Y2O3 |

| Electrical Efficiency (% LHV) | 63–70% | 56–60% | 58–62% | 74–81% |

| Temperature range (°C) | 60–80 | 70–90 | 50–70 | 600–900 |

| Pressure range (bar) | 1–30 | 30–80 | 1–30 | 1–15 |

| H2 purity (%) | 99.9% | 99.999% | 99.99% | 99.99% |

| Lifetime (h) | 100,000 | 30,000–90,000 | NA | 10,000–30,000 |

| Power Capacity | Up to several MW | Up to hundreds of kW | Up to tens of kW | Up to hundreds of kW |

| Load Range (%) | 10–110% | 0–160% | 5–100% | 20–100% |

| Technology maturity | Commercial | Commercial for small scale | R&D | Pre-commercial |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Pastore, L.M. Sector Coupling and Flexibility Measures in Distributed Renewable Energy Systems: A Comprehensive Review. Sustainability 2026, 18, 437. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010437

Pastore LM. Sector Coupling and Flexibility Measures in Distributed Renewable Energy Systems: A Comprehensive Review. Sustainability. 2026; 18(1):437. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010437

Chicago/Turabian StylePastore, Lorenzo Mario. 2026. "Sector Coupling and Flexibility Measures in Distributed Renewable Energy Systems: A Comprehensive Review" Sustainability 18, no. 1: 437. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010437

APA StylePastore, L. M. (2026). Sector Coupling and Flexibility Measures in Distributed Renewable Energy Systems: A Comprehensive Review. Sustainability, 18(1), 437. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010437