Comparative Machine Learning-Based Techniques to Provide Regenerative Braking Systems with High Efficiency for Electric Vehicles

Abstract

1. Introduction

- It introduces a comparative framework for multiple ML algorithms—Linear Regression, K-Nearest Neighbors, Decision Tree, and Random Forest—trained on a data set generated from realistic driving profiles and vehicle dynamics.

- It validates the models not only through simulation but also on a hardware test platform under WLTP Class 1 conditions, ensuring real-world applicability.

- It demonstrates that Random Forest achieves superior predictive performance (R2 = 0.97 in simulation and R2 = 0.98 in external validation), highlighting its potential to reduce mechanical braking and enhance energy recovery, paving the way for integration into real-time EV braking control strategies.

- It proposes a dual-output prediction approach for both regenerative and mechanical braking torque, using a feature space tailored for light EVs (speed, acceleration, road grade, vehicle weight, and road condition), which is rarely addressed in prior studies.

- It outlines a conceptual framework for real-time integration of ML-based torque prediction into EV braking control loops, bridging the gap between algorithmic performance and practical implementation.

2. Modeling of an EV

2.1. Vehicle Dynamics

2.2. Regenerative Braking

2.3. Driving Profiles and Cycles

3. Machine Learning Algorithms

3.1. Linear Regression

3.2. KNN Algorithm

3.3. Decision Tree Algorithm

3.4. Random Forest Algorithm

3.5. Performance Evaluation Criteria of the Algorithms

3.5.1. R-SQUARE

3.5.2. MSE

3.5.3. RMSE

3.5.4. MAE

4. Creating a Data Set and Its Training

4.1. Simulation Model

4.2. Descriptions and Data Set Preparation

4.3. Model Training

5. Training Results

5.1. Findings of the Linear Regression Algorithm

5.2. Findings of the KNN Algorithm

5.3. Findings of Decision Tree Algorithm

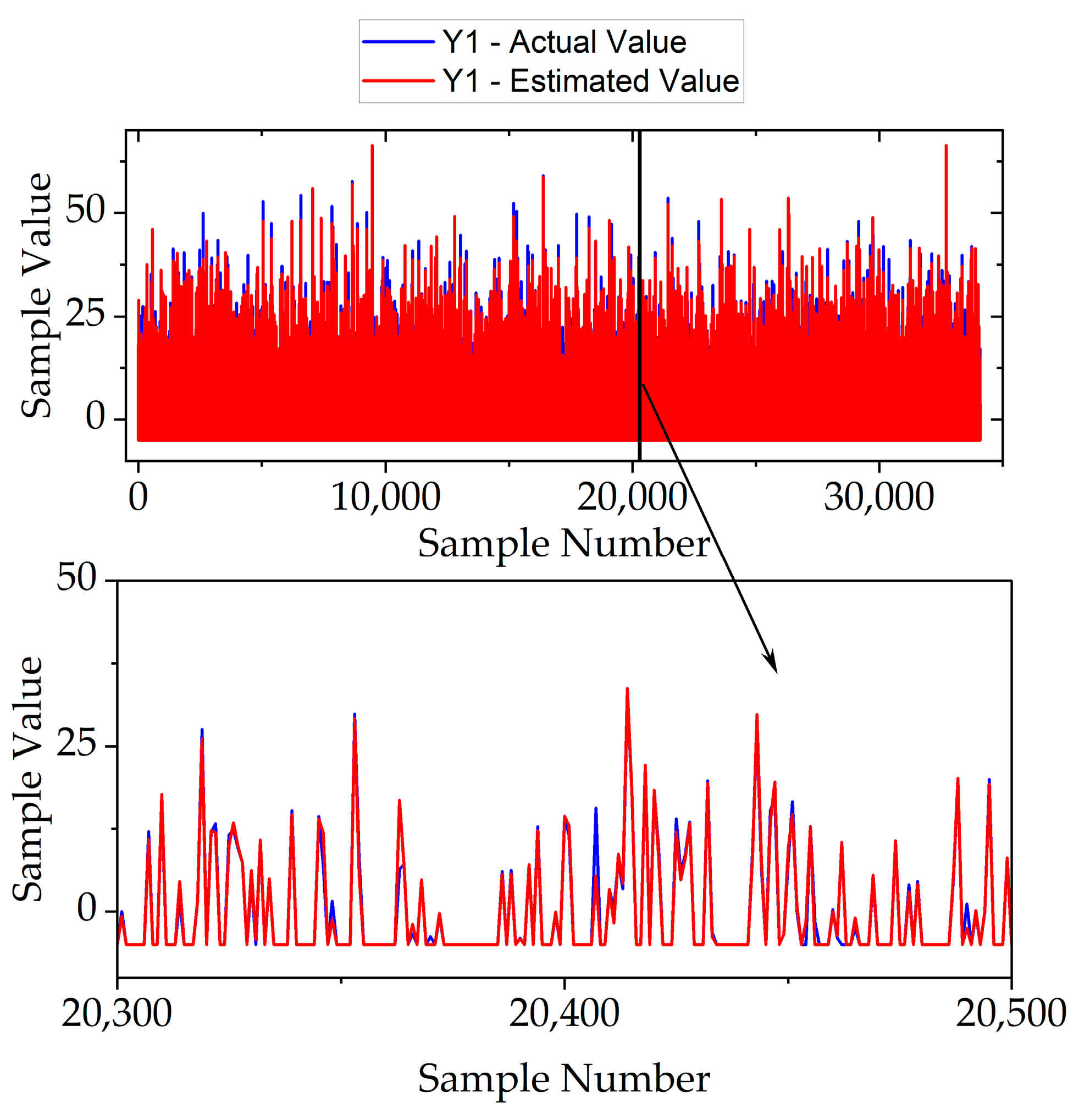

5.4. Findings of Random Forest Algorithm

5.5. Performance Evaluation of the Simulated Algorithms

6. Experimental Study

7. Conclusions

7.1. Contribution to Sustainability

7.2. Future Work

- Exploring advanced algorithms (e.g., SVM, PCA, GMM) for improved predictive accuracy

- HIL/embedded real-time deployment, battery/inverter constraints, SoC/temperature coupling.

- Quantitative validation under varying braking intensities, battery state-of-charge levels, and temperature conditions

- Detailed modeling of battery constraints, inverter dynamics, and motor characteristics

- Integration of hybrid energy storage systems combining batteries and ultra-capacitors

- Real-time implementation of ML-based torque prediction in embedded controllers

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Morgan, J. Electric Vehicles: The Future We Made and the Problem of Unmaking It. Camb. J. Econ. 2020, 44, 953–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, S.; Baral, B.; Shah, M.; Chitrakar, S.; Shrestha, B.P. Measures to Resolve Range Anxiety in Electric Vehicle Users. Int. J. Low-Carbon Technol. 2022, 17, 1186–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szumska, E.M. Regenerative Braking Systems in Electric Vehicles: A Comprehensive Review of Design, Control Strategies, and Efficiency Challenges. Energies 2025, 18, 2422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurgen, R. (Ed.) Electric and Hybrid-Electric Vehicles; SAE International: Warrendale, PA, USA, 2002; pp. 99–105. ISBN 978-0-7680-0833-3. [Google Scholar]

- Ergun, O.; Cayci, N.O.; Dincmen, E.; Istif, I. Optimum Torque Distribution During Regenerative Braking in a Fully Electrical Vehicle via Dynamic Programming. In Proceedings of the 2023 7th International Symposium on Multidisciplinary Studies and Innovative Technologies (ISMSIT), Ankara, Turkiye, 26 October 2023; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, J.; Wang, F.; Feng, J.; Zhao, M.; Fang, R.; Pi, D.; Yin, G. A Hierarchical Control of Independently Driven Electric Vehicles Considering Handling Stability and Energy Conservation. IEEE Trans. Intell. Veh. 2024, 9, 738–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, J.; Feng, J.; Fang, Z.; Lu, Y.; Yin, G.; Mao, X.; Wu, J.; Wang, F. An Energy-Oriented Torque-Vector Control Framework for Distributed Drive Electric Vehicles. IEEE Trans. Transp. Electrif. 2023, 9, 4014–4031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paterson, J.; Ramsay, M. Electric Vehicle Braking by Fuzzy Logic Control. In Proceedings of the Conference Record of the 1993 IEEE Industry Applications Conference Twenty-Eighth IAS Annual Meeting, Toronto, ON, Canada, 2–8 October 1993; Volume 3, pp. 2200–2204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Z.; Ma, X.; Su, R.; Huang, Z.; Zhang, C. Regenerative Braking of Electric Vehicles Based on Fuzzy Control Strategy. Processes 2023, 11, 2985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prakash, Z. Integration of AI and ML in Regenerative Braking for Electric Vehicles: A Review. Front. Artif. Intell. 2025, 8, 1626804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, B.; Zhang, X.; Wang, Y.; Hu, W. Regenerative Braking Control Strategy of Electric Vehicles Based on Braking Stability Requirements. Int. J. Automot. Technol. 2021, 22, 465–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szumska, E.M.; Jurecki, R. The Analysis of Energy Recovered during the Braking of an Electric Vehicle in Different Driving Conditions. Energies 2022, 15, 9369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasanth, B.; Paul, R.; Kaliyaperumal, D.; Kannan, R.; Venkata Pavan Kumar, Y.; Kalyan Chakravarthi, M.; Venkatesan, N. Maximizing Regenerative Braking Energy Harnessing in Electric Vehicles Using Machine Learning Techniques. Electronics 2023, 12, 1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Xiao, W. Research on Braking Intention Recognition Algorithm for Pure Electric Vehicles Based on Adaboost. In Proceedings of the Third International Conference on Electronic Information Engineering and Data Processing (EIEDP 2024), Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 5 July 2024; Jabbar, M.A., Lorenz, P., Eds.; SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2024; p. 233. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Z.; Feng, H.; Meng, Y.; Xu, E.; Wu, Y. Braking Energy Management Strategy for Electric Vehicles Based on Working Condition Prediction. AIP Adv. 2022, 12, 015220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anh, N.T.; Chen, C.-K.; Liu, X. An Efficient Regenerative Braking System for Electric Vehicles Based on a Fuzzy Control Strategy. Vehicles 2024, 6, 1496–1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, M.; Zhang, X. Optimal Regenerative Braking Control Strategy for Electric Vehicles Based on Braking Intention Recognition and Load Estimation. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2024, 73, 3378–3392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, G.; Sudeep, R.; Ashok, B.; Vignesh, R.; Kannan, C.; Kavitha, C.; Alroobaea, R.; Alsafyani, M.; AboRas, K.M.; Emara, A. Intelligent Regenerative Braking Control With Novel Friction Coefficient Estimation Strategy for Improving the Performance Characteristics of Hybrid Electric Vehicle. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 110361–110384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, J.G.; Goodarzi, G.A. Electric Powertrain: Energy Systems, Power Electronics & Drives for Hybrid, Electric and Fuel Cell Vehicles; John Wiley & Sons Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2018; ISBN 9781119063667. [Google Scholar]

- Barlow, T.J.; Latham, S.; Mccrae, I.S.; Boulter, P.G. A Reference Book of Driving Cycles for Use in the Measurement of Road Vehicle Emissions; TRL Published Project Report; TRL: Crowthorne, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Kesler, S.; Boyaci, O.; Tumbek, M. Design and Implementation of a Regenerative Mode Electric Vehicle Test Platform for Engineering Education. Sustainability 2022, 14, 14316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Reference | Algorithms | Driving Cycles | Feature Set | Energy Recovery Impact | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [9] | Fuzzy logic | NEDC, WLTC, FTP, CLTC-P, NYCC | Speed, brake intensity | >15% | Rule-based approach lacks adaptability, no ML comparison |

| [11] | Optimization algorithm | UDDS, NEDC | Brake strength, front/rear distribution, torque limits | >51.9% recovery vs. ADVISOR strategy | Idealized cycle-tracking, limited real-world variability, no experimental validation |

| [13] | ANN, RF, DT | FTP, HWFET, NEDC, WLTP | Speed, acceleration, brake demand, SoC | 59% | No hardware validation, limited driving profiles, single torque focus |

| [14] | AdaBoost | Lab tests across speeds | Acceleration, pedal displacement/force; RF for feature selection | High accuracy for intent regen level selection | Limited data set |

| [15] | Decision Tree (C4.5) + LSTM + PSO | Real-vehicle data, WLTC/CLTC segments | Condition label, braking strength, torque/speed demand | 19.1% recovery, 15.8% energy-use reduction (per 100 km) | Limited classes, complex pipeline, generalization needed |

| [16] | Fuzzy control | NEDC, WLTC, FTP-72/75 | Speed, deceleration, SoC | 13% (WLTC), 16% (NEDC), 30% (FTP) | Controller gains need tuning across vehicles, battery limits not co-optimized |

| [17] | WOA-SVM | ECE R13 | Brake displacement, pedal speed | Braking energy recovery increases by 28.16% to 113.04% on different road conditions | Limited feature set |

| [18] | Fuzzy logic control and adaptive neuro-fuzzy inference system | FTP 75+US06, JCOB+WHVC+CEDC, Artemis Rural and Urban | Brake force, speed, acceleration, tire angular rate | Fuel economy, improvements of about 0.282%, 0.437%, and 0.345% | Limited feature set |

| Proposed Study | LR, KNN, DT, RF | Simulation and hardware (WLTP Class 1) | Speed, acceleration, road grade, vehicle weight, road condition | Demonstrated RF model with R2 = 0.98; potential to reduce mechanical braking | Includes experimental validation, dual torque prediction, real-time applicability assessment |

| NYCC | WLTP Cl-1 | Japan-10 | ECE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Pauses | 18 | 9 | 2 | 3 |

| Pause Time (s) | 210 | 203 | 39 | 64 |

| Distance (km) | 1.9 | 11.42 | 17.44 | 0.99 |

| Average Speed (km/h) | 11.41 | 28.5 | 17.57 | 18.26 |

| Duration (s) | 598 | 1022 | 137 | 195 |

| Maximum Speed (km/h) | 44.58 | 44 | 40 | 50 |

| Maximum Deceleration (m/s2) | −2.64 | −1 | −0.81 | −0.83 |

| Maximum Acceleration (m/s2) | 2.68 | 0.76 | 0.81 | 1.06 |

| Average Acceleration (m/s2) | 0.62 | 0.69 | 0.67 | 0.64 |

| Average Deceleration (m/s2) | −0.61 | −0.78 | −0.65 | −0.75 |

| Input/Outputs | Defined Parameters | |

|---|---|---|

| X1 | Input | Speed (m/s) |

| X2 | Input | Acceleration (m/s2) |

| X3 | Input | Road grade (%) |

| X4 | Input | Vehicle weight (kg) |

| X5 | Input | Road condition (asphalt, mud, soil) |

| Y1 | Output | Motor torque (Nm) |

| Y2 | Output | Mechanical brake torque (Nm) |

| Inputs/Outputs | Data Range |

|---|---|

| Speed | 0 m/s–13.88 m/s |

| Acceleration | −2.637 m/s2–2.682 (m/s2) |

| Road grade | −3%, 0%, 3% |

| Vehicle weight | 150 kg–200 kg |

| Road condition | (Asphalt, Mud, Soil) |

| Motor torque | −5 Nm–30 Nm |

| Mechanical brake torque | −30 Nm–0 Nm |

| Performance Criteria | Calculated Value |

|---|---|

| R2 | 0.67 |

| MSE | 16.54 |

| RMSE | 4.07 |

| MAE | 3.08 |

| Performance Criteria | Calculated Value |

|---|---|

| R2 | 0.86 |

| MSE | 7.15 |

| RMSE | 2.67 |

| MAE | 1.37 |

| Performance Criteria | Calculated Value |

|---|---|

| R2 | 0.96 |

| MSE | 1.94 |

| RMSE | 1.39 |

| MAE | 0.46 |

| Performance Criteria | Calculated Value |

|---|---|

| R2 | 0.97 |

| MSE | 1.39 |

| RMSE | 1.18 |

| MAE | 0.41 |

| Parameters | Values |

|---|---|

| Drag Coefficient (Cd) | 0.3 |

| Rolling Resistance Coefficient (Kr) | 0.012 |

| Front Surface Area of the Vehicle (A) | 1.64 m2 |

| Weight (M) | 200 kg |

| Bulk Density of Air (Ρ) | 1.2 kg/m3 |

| Climbing Angle (Θ) | −3, 0, 3 |

| Gravitational Acceleration (G) | 9.81 m/s2 |

| Performance Criteria | Calculated Value |

|---|---|

| R2 | 0.98 |

| MSE | 0.78 |

| RMSE | 0.88 |

| MAE | 0.27 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Boyaci, O.; Tumbek, M. Comparative Machine Learning-Based Techniques to Provide Regenerative Braking Systems with High Efficiency for Electric Vehicles. Sustainability 2026, 18, 414. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010414

Boyaci O, Tumbek M. Comparative Machine Learning-Based Techniques to Provide Regenerative Braking Systems with High Efficiency for Electric Vehicles. Sustainability. 2026; 18(1):414. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010414

Chicago/Turabian StyleBoyaci, Omer, and Mustafa Tumbek. 2026. "Comparative Machine Learning-Based Techniques to Provide Regenerative Braking Systems with High Efficiency for Electric Vehicles" Sustainability 18, no. 1: 414. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010414

APA StyleBoyaci, O., & Tumbek, M. (2026). Comparative Machine Learning-Based Techniques to Provide Regenerative Braking Systems with High Efficiency for Electric Vehicles. Sustainability, 18(1), 414. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010414