An Ecologically Sustainable Approach to Solid-Phase Microextraction Techniques Using Deep Eutectic Solvents

Abstract

1. Towards an Ecologically Sustainable Approach to Sample Preparation

- direct, automated, miniaturized, and multi-analyte approach,

- minimum sample size and number of samples processed,

- reduction in the consumption of chemical reagents and waste generation,

- reduction in threats and risks,

- increasing work safety and environmental friendliness [6].

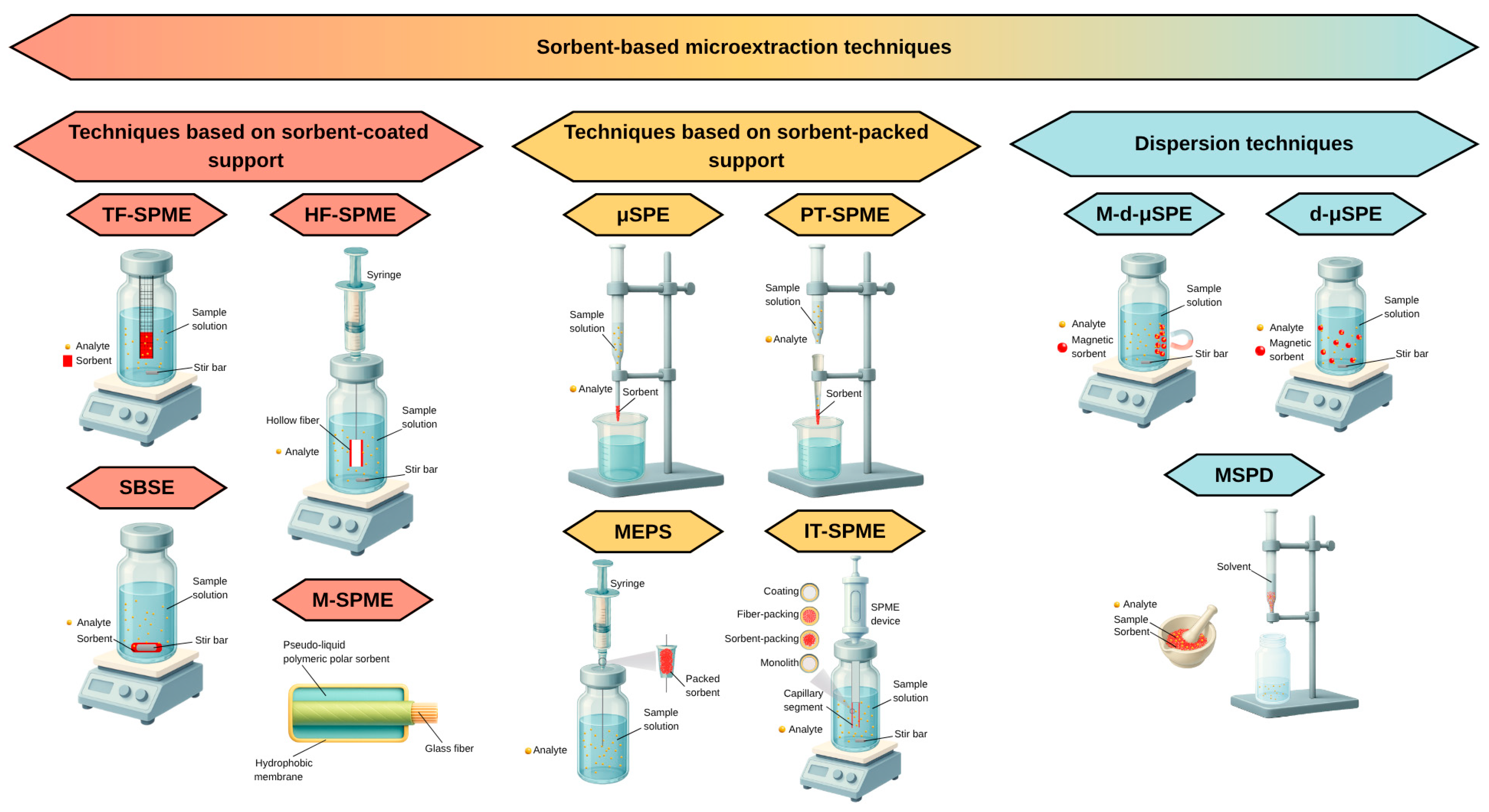

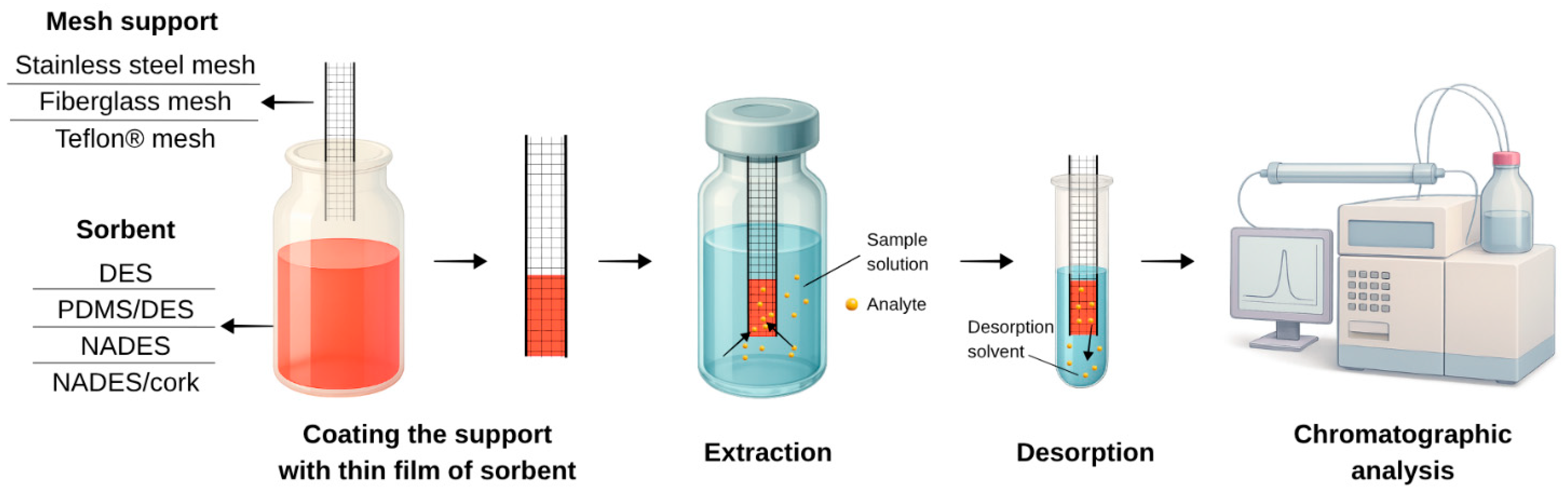

2. Sorbent-Based Microextraction Techniques

- (1)

- techniques based on a support coated sorbent: hollow fiber solid-phase microextraction (HF-SPME), stir bar sorptive extraction (SBSE), thin film solid-phase microextraction (TF-SPME), membrane solid-phase microextraction (M-SPME),

- (2)

- techniques based on a sorbent-packaged support: micro solid-phase extraction (μSPE), pipette tip solid-phase microextraction (PT-SPME), in tube solid-phase microextraction (IT-SPME), microextraction by packed sorbent (MEPS),

- (3)

3. Solid-Phase Microextraction

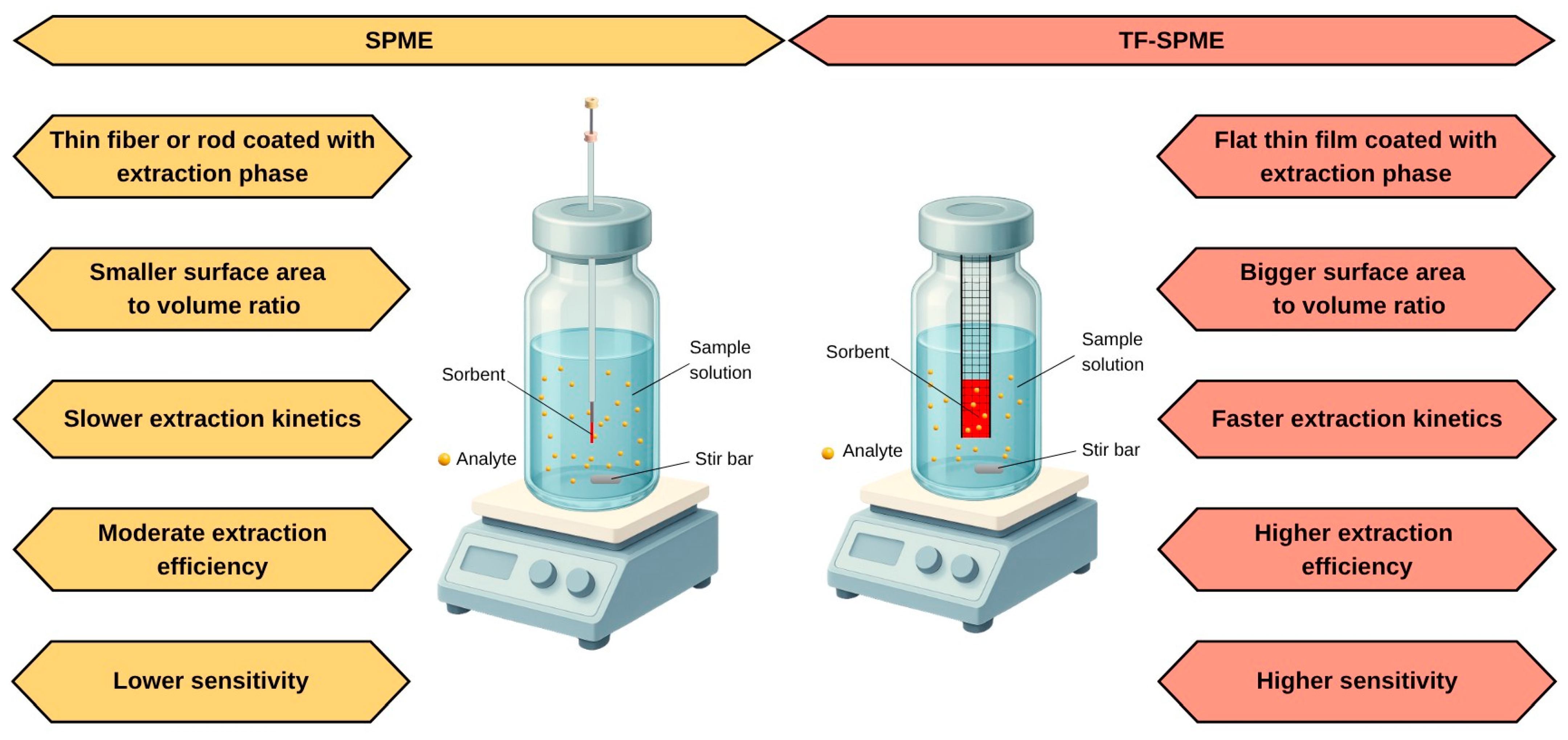

3.1. Geometry of Support in SPME

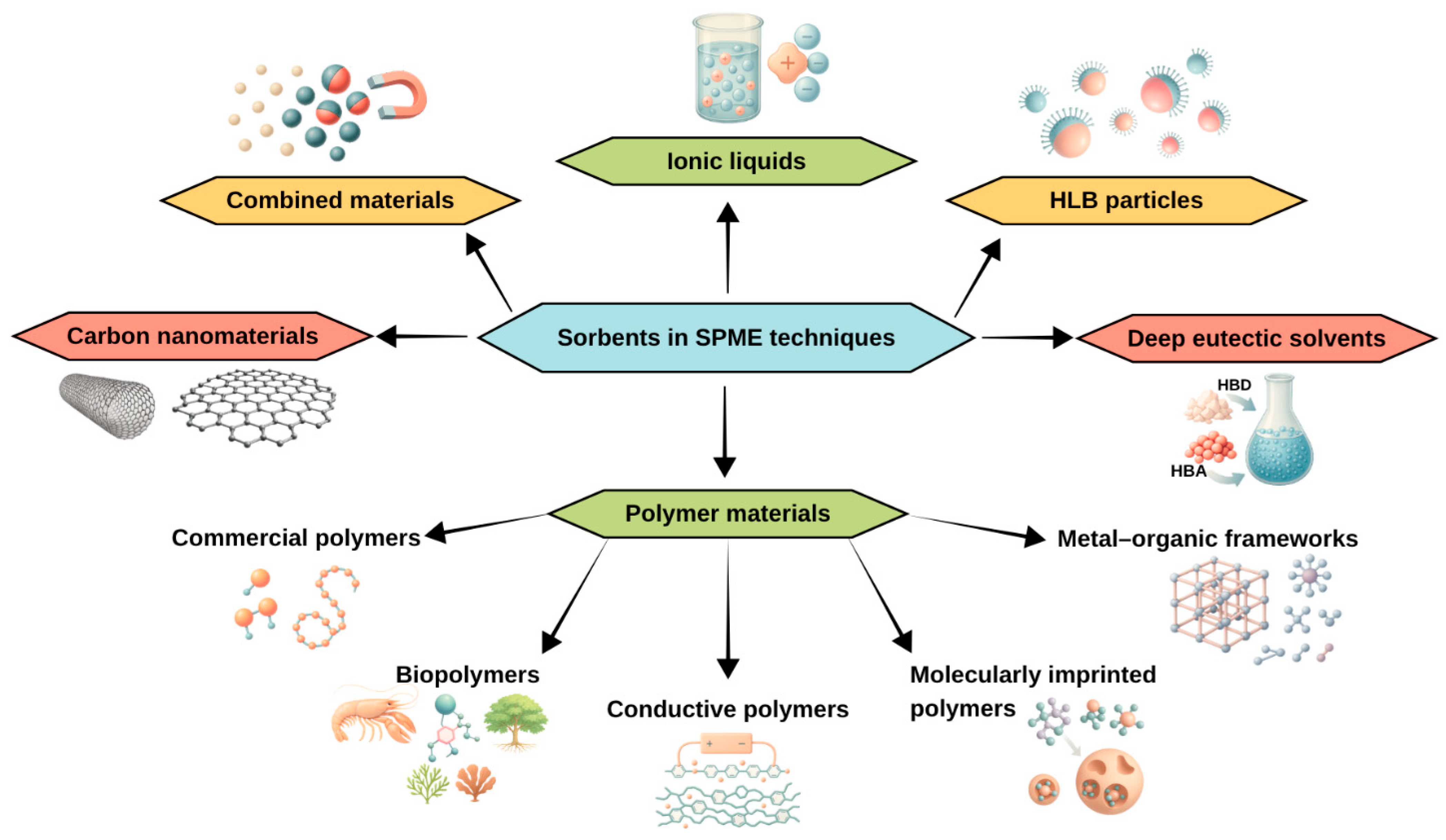

3.2. Development of Sorbents in SPME

- (1)

- Commercial polymers, including polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS), a mixture of polydimethylsiloxane and divinylbenzene (PDMS/DVB), a mixture of polydimethylsiloxane and carboxyl (PDMS/CAR), polyacrylonitrile (PAN) [35].

- (2)

- (3)

- (4)

- (5)

- Molecularly imprinted polymers (MIPs), i.e., biomimetic materials that possess “imprints” of their molecular matrices, due to which they can selectively bind specific analytes. MIPs are formed by polymerizing monomers around a standard molecule, which is then removed, leaving specific voids [42,43,44].

- (6)

- (7)

- (8)

- Hydrophilic-lipophilic balance (HLB) particles, i.e., molecules that include both a water-attracting (hydrophilic) part and a fat-attracting (lipophilic) part [50],

- (9)

- Combined materials: e.g., magnetic nanoparticles with one or more of the materials mentioned above (Figure 3).

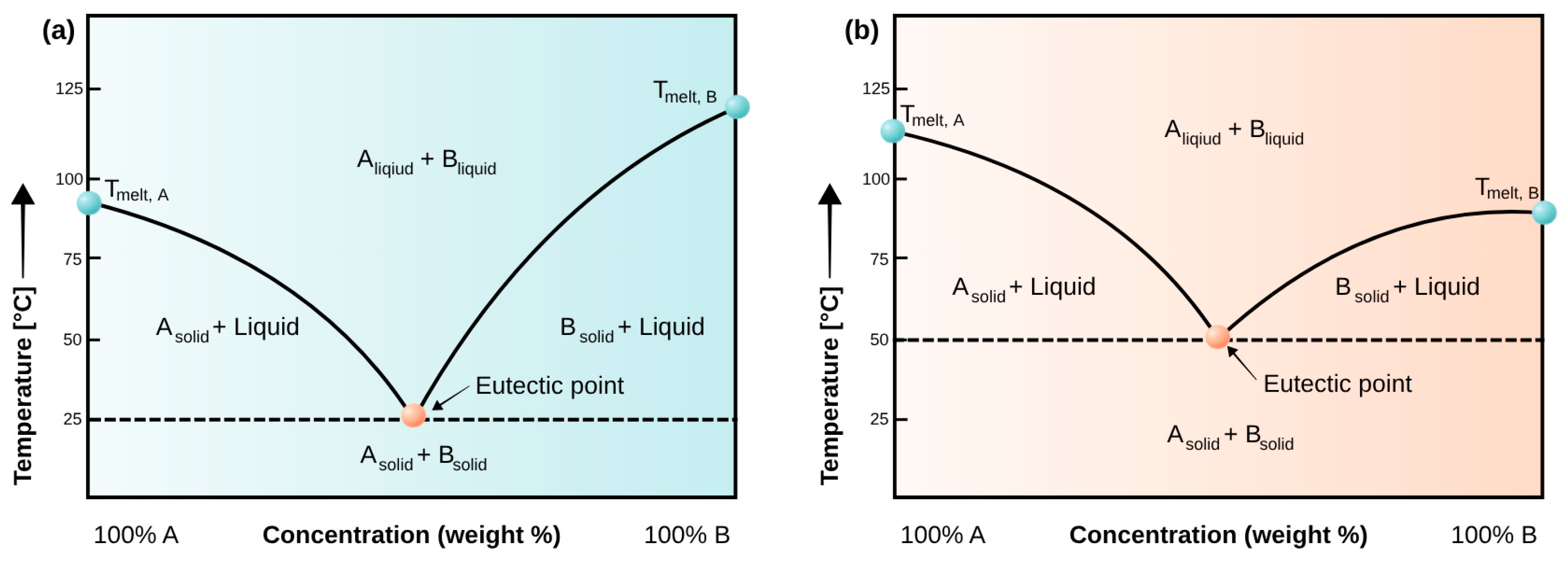

4. Deep Eutectic Solvents—Definition and Properties

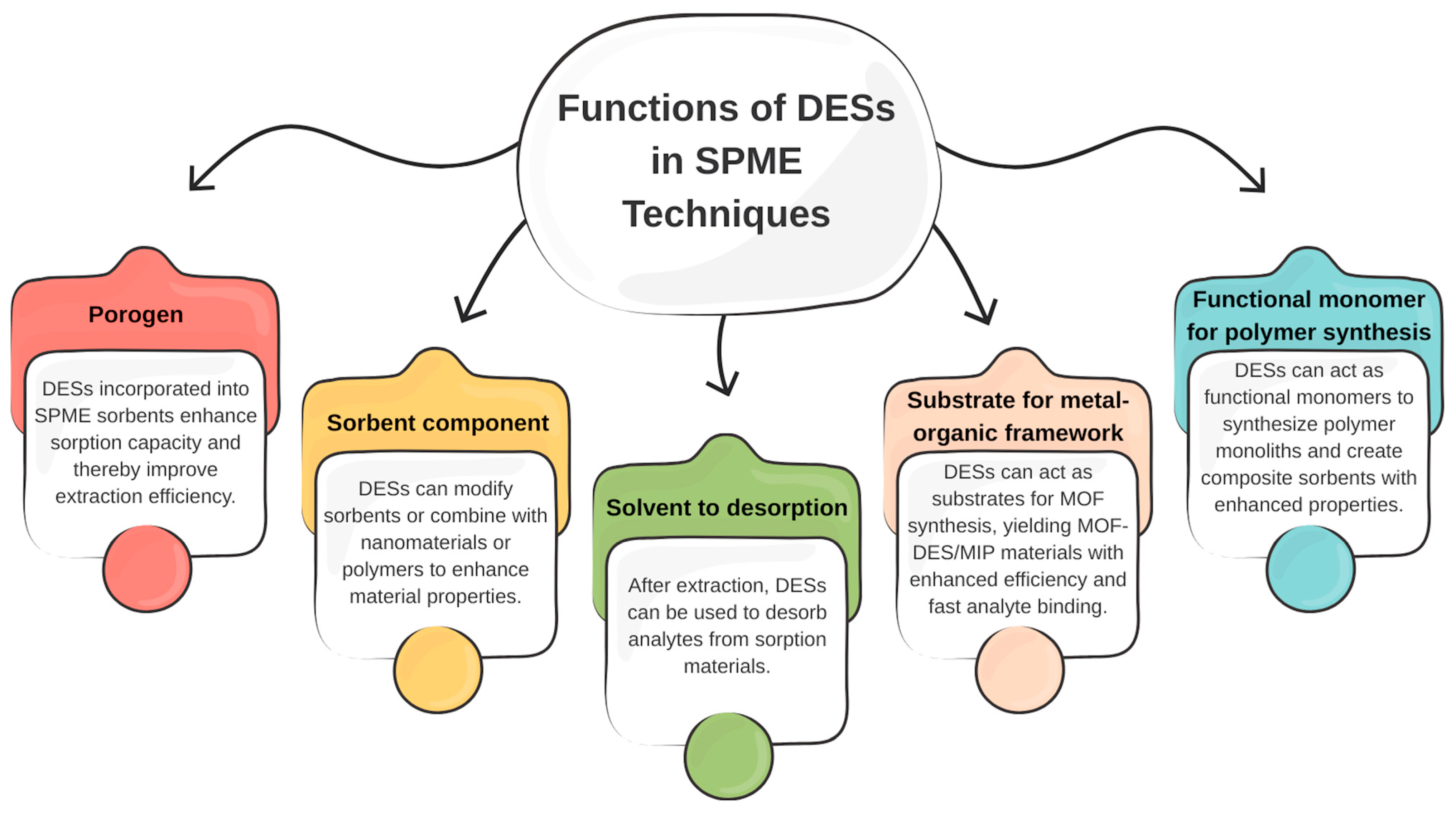

5. Deep Eutectic Solvents in Approaches to SPME Techniques

5.1. DESs as Porogens

5.2. DESs as Functional Monomers

5.3. DESs as Substrate to MOFs

5.4. DESs as Sorbent Components

5.5. DESs as Desorption Media

6. Greenness and Sustainability Metrics

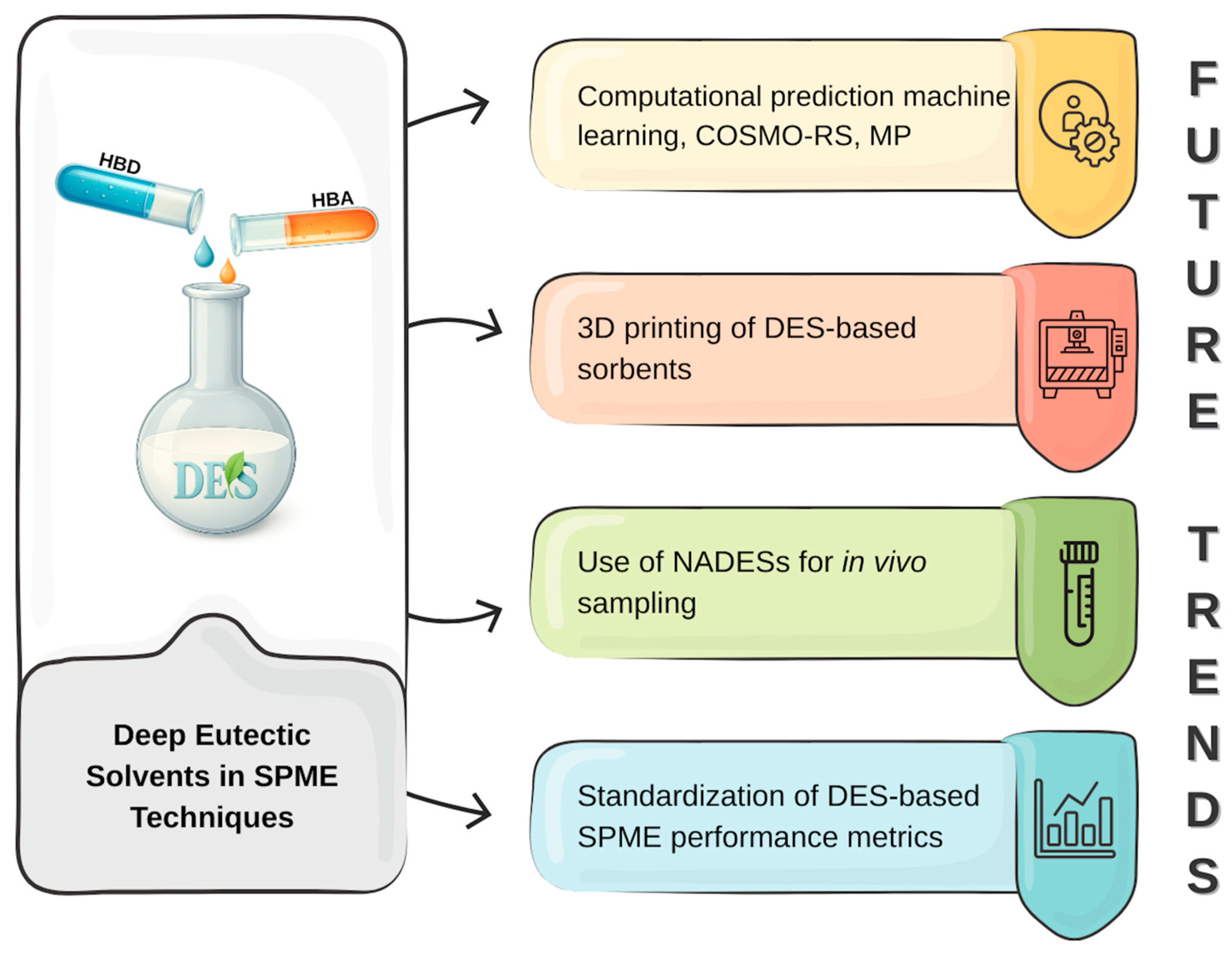

7. Future Trends in the Development of DESs-Based SPME

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| GAC | Green Analytical Chemistry |

| GSP | Green Sample Preparation |

| WAC | White Analytical Chemistry |

| LPME | Liquid phase microextraction |

| SPME | Solid-phase microextraction |

| HF-SPME | Hollow fiber solid-phase microextraction |

| SBSE | Stir bar sorptive extraction |

| TF-SPME | Thin film solid-phase microextraction |

| M-SPME | Membrane solid-phase microextraction |

| μSPE | Micro solid-phase extraction |

| PT-SPME | Pipette tip solid-phase microextraction |

| IT-SPME | In tube solid-phase microextraction |

| MEPS | Microextraction by packed sorbent |

| d-μSPE | Dispersive micro solid-phase extraction |

| M-d-μSPE | Magnetic dispersive micro solid-phase extraction |

| MSPD | Matrix solid-phase dispersion |

| HF-SLPME | Hollow fiber solid–liquid microextraction |

| PDMS | Polydimethylsiloxane |

| DVB | Divinylbenzene |

| CAR | Carboxyl |

| PAN | Polyacrylonitrile |

| PANI | Polyaniline |

| PPV | Polyphenylenevinylene |

| PPy | Polypyrrole |

| PEDOT | Polyethylene dioxythiophene |

| MOFs | Metal–organic frameworks |

| SBUs | Secondary building blocks |

| MIPs | Molecularly imprinted polymers |

| CNMs | Carbon nanomaterials |

| G | Graphene |

| CNTs | Carbon nanotubes |

| IL | Ionic liquids |

| PILs | Polymeric ionic liquids |

| HLB | Hydrophilic-lipophilic balance |

| DESs | Deep eutectic solvents |

| HBD | Hydrogen bond donor |

| HBA | Hydrogen bond acceptor |

| NADESs | Natural deep eutectic solvents |

| ChCl | Choline chloride |

| DLLME | Dispersive liquid–liquid microextraction |

| SDME | Single-drop microextraction |

| HF-LPME | Hollow fiber liquid phase microextraction |

| SMSNs | Star-shaped mesoporous silica nanoparticles |

| PAHs | Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons |

| NSAIDs | Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs |

| CEC | Capillary electrochromatography |

| RSD | Relative standard deviation |

| GC-FID | Gas chromatography with flame ionization detector |

| GC-MS/MS | Gas chromatography with tandem mass spectrometry |

| PCNs | Polychlorinated naphthalenes |

| 3D DES-GA | Three-dimensional deep eutectic solvent modified graphene aerogel |

| GMA | Glycidyl methacrylate |

| EGDMA | Ethylene glycol dimethylacrylate |

| HPLC-MS/MS | High-performance liquid chromatography with tandem mass spectrometry |

| PEEK | Polyether ether ketone |

| HPLC-UV | High-performance liquid chromatography with ultraviolet detection |

| TDES | Ternary deep eutectic solvent |

| 3,4-DHBA | 3,4-dihydroxybenzoic acid |

| HFLMP-SPME | Solid-phase microextraction using hollow fibers with a liquid membrane-protected |

| MMF-SPME | Multiple monolithic fiber solid-phase microextraction |

| CA | Calcium alginate |

| PEG | Polyethylene glycol |

| HMF | 5-hydroxymethylfurfural |

| Complex GAPI | Complex Green Analytical Procedure Index |

| AES | Analytical Eco-Scale |

| GO | Graphene oxide |

| F-AAS | Flame atomic absorption spectrometry |

| EC-IT-SPME | Electrochemically in tube controlled solid-phase microextraction |

| GC-MS | Gas chromatography with mass spectrometry |

| THTDPCl | Trihexyltetradecylphosphonium chloride |

| DcOH | 1-docosanol |

| EDCs | Endocrine disrupting compounds |

| LC-MS/MS | Liquid chromatography with tandem mass spectrometry |

| ComplexMoGAPI | Complex modified Green Analytical Procedure Index |

| BeCl | Betaine chloride |

| EiOH | 1-eicosanol |

| CTA | Cellulose triacetate |

| OPPs | Organophosphorus pesticides |

| ACGO | Agarose-chitosan nanostructures on a graphene oxide |

| EF | Enrichment factor |

| NEMI | National Environmental Methods Index |

| GAPI | Green Analytical Procedure Index |

| AGREE | Analytical GREEnness Metric Approach |

| SPMS | Sample Preparation Metric Sustainability |

| LCA | Life-cycle assessment |

| MD | Molecular dynamics |

| COSMO-RS | Conductor-like Screening Model for Real Solvents |

| ML | Machine learning |

References

- Martínez-Pérez-Cejuela, H.; Gionfriddo, E. Innovative Sample Preparation Strategies for Emerging Pollutants in Environmental Samples. Annu. Rev. Anal. Chem. 2025, 18, 73–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krumplewski, W.; Rykowska, I. New Materials for Thin-Film Solid-Phase Microextraction (TF-SPME) and Their Use for Isolation and Preconcentration of Selected Compounds from Aqueous, Biological and Food Matrices. Molecules 2024, 29, 5025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sajid, M.; Płotka-Wasylka, J. Green Analytical Chemistry Metrics: A Review. Talanta 2022, 238, 123046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López-Lorente, Á.I.; Pena-Pereira, F.; Pedersen-Bjergaard, S.; Zuin, V.G.; Ozkan, S.A.; Psillakis, E. The Ten Principles of Green Sample Preparation. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2022, 148, 116530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, C.M.; Hussain, C.G.; Keçili, R. White Analytical Chemistry Approaches for Analytical and Bioanalytical Techniques: Applications and Challenges. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2023, 159, 116905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saura-Cayuela, M.; Lara-Torres, S.; Pacheco-Fernández, I.; Trujillo-Rodríguez, M.J.; Ayala, J.H.; Pino, V. Green Materials for Greener Food Sample Preparation: A Review. Green Anal. Chem. 2023, 4, 100053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutkowska, M.; Płotka-Wasylka, J.; Sajid, M.; Andruch, V. Liquid–Phase Microextraction: A Review of Reviews. Microchem. J. 2019, 149, 103989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faraji, H. Advancements in Overcoming Challenges in Dispersive Liquid-Liquid Microextraction: An Overview of Advanced Strategies. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2024, 170, 117429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trujillo-Rodríguez, M.J.; Pacheco-Fernández, I.; Taima-Mancera, I.; Díaz, J.H.A.; Pino, V. Evolution and Current Advances in Sorbent-Based Microextraction Configurations. J. Chromatogr. A 2020, 1634, 461670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ntorkou, M.; Zacharis, C.K. Sorbent-Based Microextraction Combined with GC-MS: A Valuable Tool in Bioanalysis. Chemosensors 2025, 13, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbasi, S.; Ammar Haeri, S. Biodegradable Materials and Their Applications in Sample Preparation Techniques–A Review. Microchem. J. 2021, 171, 106831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arthur, C.L.; Pawliszyn, J. Solid Phase Microextraction with Thermal Desorption Using Fused Silica Optical Fibers. Anal. Chem. 1990, 62, 2145–2148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piri-Moghadam, H.; Ahmadi, F.; Pawliszyn, J. A Critical Review of Solid Phase Microextraction for Analysis of Water Samples. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2016, 85, 133–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, X.; Wang, L.; Guo, Y. Recent Developments in Solid-Phase Microextraction Coatings for Environmental and Biological Analysis. Chem. Lett. 2017, 46, 1444–1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Kuang, Y.; Zhou, S.; Gong, X.; Ouyang, G. Latest Improvements and Expanding Applications of Solid-Phase Microextraction. Anal. Chem. 2023, 95, 218–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sajid, M.; Khaled Nazal, M.; Rutkowska, M.; Szczepańska, N.; Namieśnik, J.; Płotka-Wasylka, J. Solid Phase Microextraction: Apparatus, Sorbent Materials, and Application. Crit. Rev. Anal. Chem. 2019, 49, 271–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawliszyn, J. Handbook of Solid Phase Microextraction; Elsevier: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Lord, H.; Zhang, X.; Musteata, F.M.; Vuckovic, D.; Pawliszyn, J. In vivo solid-phase microextraction for monitoring intravenous concentrations of drugs and metabolites. Nat. Protoc. 2011, 6, 896–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tintrop, L.K.; Salemi, A.; Jochmann, M.A.; Engewald, W.R.; Schmidt, T.C. Improving Greenness and Sustainability of Standard Analytical Methods by Microextraction Techniques: A Critical Review. Anal. Chim. Acta 2023, 1271, 341468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cudjoe, E.; Vuckovic, D.; Hein, D.; Pawliszyn, J. Investigation of the Effect of the Extraction Phase Geometry on the Performance of Automated Solid-Phase Microextraction. Anal. Chem. 2009, 81, 4226–4232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruheim, I.; Liu, X.; Pawliszyn, J. Thin-Film Microextraction. Anal. Chem. 2003, 75, 1002–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, R.; Pawliszyn, J. Thin-Film Microextraction Offers Another Geometry for Solid-Phase Microextraction. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2012, 39, 245–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emmons, R.V.; Tajali, R.; Gionfriddo, E. Development, Optimization and Applications of Thin Film Solid Phase Microextraction (TF-SPME) Devices for Thermal Desorption: A Comprehensive Review. Separations 2019, 6, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olcer, Y.A.; Tascon, M.; Eroglu, A.E.; Boyacı, E. Thin Film Microextraction: Towards Faster and More Sensitive Microextraction. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2019, 113, 93–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grandy, J.J.; Boyacı, E.; Pawliszyn, J. Development of a Carbon Mesh Supported Thin Film Microextraction Membrane As a Means to Lower the Detection Limits of Benchtop and Portable GC/MS Instrumentation. Anal. Chem. 2016, 88, 1760–1767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirnaghi, F.S.; Chen, Y.; Sidisky, L.M.; Pawliszyn, J. Optimization of the Coating Procedure for a High-Throughput 96-Blade Solid Phase Microextraction System Coupled with LC–MS/MS for Analysis of Complex Samples. Anal. Chem. 2011, 83, 6018–6025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasiljevic, T.; Gómez-Ríos, G.A.; Li, F.; Liang, P.; Pawliszyn, J. High-throughput quantification of drugs of abuse in biofluids via 96-solid-phase microextraction–transmission mode and direct analysis in real time mass spectrometry. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 2019, 33, 1423–1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grecco, C.F.; de Souza, I.D.; Carvalho Oliveira, I.G.; Costa Queiroz, M.E. In-Tube Solid-Phase Microextraction Directly Coupled to Mass Spectrometric Systems: A Review. Separations 2022, 9, 394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kataoka, H. In-Tube Solid-Phase Microextraction: Current Trends and Future Perspectives. J. Chromatogr. A 2021, 1636, 461787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, W.C.; Song, M.Y.; Zheng, T.L.; Zhang, Z.Q.; Jiang, Y.; Guo, J.L.; Zhang, Y.Z. Development of an hollow fiber solid phase microextraction method for the analysis of unbound fraction of imatinib and N-desmethyl imatinib in human plasma. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2024, 250, 116405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prosen, H. Applications of Hollow-Fiber and Related Microextraction Techniques for the Determination of Pesticides in Environmental and Food Samples—A Mini Review. Separations 2019, 6, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lashgari, M.; Yamini, Y. An Overview of the Most Common Lab-Made Coating Materials in Solid Phase Microextraction. Talanta 2019, 191, 283–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maciel, E.V.S.; de Toffoli, A.L.; Neto, E.S.; Nazario, C.E.D.; Lanças, F.M. New Materials in Sample Preparation: Recent Advances and Future Trends. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2019, 119, 115633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godage, N.H.; Gionfriddo, E. Use of Natural Sorbents as Alternative and Green Extractive Materials: A Critical Review. Anal. Chim. Acta 2020, 1125, 187–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bragg, L.; Qin, Z.; Alaee, M.; Pawliszyn, J. Field Sampling with a Polydimethylsiloxane Thin-Film. J. Chromatogr. Sci. 2006, 44, 317–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werner, J.; Zgoła-Grześkowiak, A.; Grześkowiak, T.; Frankowski, R. Biopolymers-Based Sorbents as a Future Green Direction for Solid Phase (Micro)Extraction Techniques. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2024, 173, 117659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacheco-Fernández, I.; Allgaier-Díaz, D.W.; Mastellone, G.; Cagliero, C.; Díaz, D.D.; Pino, V. Biopolymers in Sorbent-Based Microextraction Methods. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2020, 125, 115839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turazzi, F.C.; Morés, L.; Carasek, E.; Barra, G.M.d.O. Polyaniline-silica Doped with Oxalic Acid as a Novel Extractor Phase in Thin Film Solid-phase Microextraction for Determination of Hormones in Urine. J. Sep. Sci. 2023, 46, 2300280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz-Zanjani, M.O.; Mehdinia, A. Electrochemically Prepared Solid-Phase Microextraction Coatings—A Review. Anal. Chim. Acta 2013, 781, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rocío-Bautista, P.; Pacheco-Fernández, I.; Pasán, J.; Pino, V. Are Metal-Organic Frameworks Able to Provide a New Generation of Solid-Phase Microextraction Coatings?—A Review. Anal. Chim. Acta 2016, 939, 26–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omarova, A.; Bakaikina, N.V.; Muratuly, A.; Kazemian, H.; Baimatova, N. A Review on Preparation Methods and Applications of Metal–Organic Framework-Based Solid-Phase Microextraction Coatings. Microchem. J. 2022, 175, 107147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turiel, E.; Martín-Esteban, A. Molecularly Imprinted Polymers-Based Microextraction Techniques. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2019, 118, 574–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Álvarez, M.; Turiel, E.; Martín-Esteban, A. Recent Advances and Future Trends in Molecularly Imprinted Polymers-based Sample Preparation. J. Sep. Sci. 2023, 46, 2300157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hijazi, H.Y.; Bottaro, C.S. Molecularly Imprinted Polymer Thin-Film as a Micro-Extraction Adsorbent for Selective Determination of Trace Concentrations of Polycyclic Aromatic Sulfur Heterocycles in Seawater. J. Chromatogr. A 2020, 1617, 460824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maciel, E.V.S.; Mejía-Carmona, K.; Jordan-Sinisterra, M.; da Silva, L.F.; Vargas Medina, D.A.; Lanças, F.M. The Current Role of Graphene-Based Nanomaterials in the Sample Preparation Arena. Front. Chem. 2020, 8, 664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Liu, B.; Lu, Q.; Qu, Q. Graphene-Based Materials: Fabrication and Application for Adsorption in Analytical Chemistry. J. Chromatogr. A 2014, 1362, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quintanilla, I.; Perelló, C.; Merlo, F.; Profumo, A.; Fontàs, C.; Anticó, E. Multiwalled Carbon Nanotubes Embedded in a Polymeric Matrix as a New Material for Thin Film Microextraction (TFME) in Organic Pollutant Monitoring. Polymers 2023, 15, 314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patinha, D.J.S.; Silvestre, A.J.D.; Marrucho, I.M. Poly(Ionic Liquids) in Solid Phase Microextraction: Recent Advances and Perspectives. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2019, 98, 101148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, M.; Huang, X.; Chen, L. Recent Development and Applications of Poly (Ionic Liquid)s in Microextraction Techniques. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2019, 112, 123–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grandy, J.J.; Singh, V.; Lashgari, M.; Gauthier, M.; Pawliszyn, J. Development of a Hydrophilic Lipophilic Balanced Thin Film Solid Phase Microextraction Device for Balanced Determination of Volatile Organic Compounds. Anal. Chem. 2018, 90, 14072–14080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbott, A.P.; Capper, G.; Davies, D.L.; Rasheed, R.K.; Tambyrajah, V. Novel Solvent Properties of Choline Chloride/Urea Mixtures. Chem. Commun. 2003, 39, 70–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbott, A.P.; Boothby, D.; Capper, G.; Davies, D.L.; Rasheed, R.K. Deep Eutectic Solvents Formed between Choline Chloride and Carboxylic Acids: Versatile Alternatives to Ionic Liquids. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 126, 9142–9147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vanda, H.; Dai, Y.; Wilson, E.G.; Verpoorte, R.; Choi, Y.H. Green Solvents from Ionic Liquids and Deep Eutectic Solvents to Natural Deep Eutectic Solvents. C. R. Chim. 2018, 21, 628–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, E.L.; Abbott, A.P.; Ryder, K.S. Deep Eutectic Solvents (DESs) and Their Applications. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 11060–11082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, M.A.R.; Pinho, S.P.; Coutinho, J.A.P. Insights into the Nature of Eutectic and Deep Eutectic Mixtures. J. Solut. Chem. 2019, 48, 962–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, B.B.; Spittle, S.; Chen, B.; Poe, D.; Zhang, Y.; Klein, J.M.; Horton, A.; Adhikari, L.; Zelovich, T.; Doherty, B.W.; et al. Deep Eutectic Solvents: A Review of Fundamentals and Applications. Chem. Rev. 2021, 121, 1232–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omar, K.A.; Sadeghi, R. Physicochemical Properties of Deep Eutectic Solvents: A Review. J. Mol. Liq. 2022, 360, 119524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.H.; van Spronsen, J.; Dai, Y.; Verberne, M.; Hollmann, F.; Arends, I.W.C.E.; Witkamp, G.-J.; Verpoorte, R. Are Natural Deep Eutectic Solvents the Missing Link in Understanding Cellular Metabolism and Physiology? Plant Physiol. 2011, 156, 1701–1705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.; van Spronsen, J.; Witkamp, G.-J.; Verpoorte, R.; Choi, Y.H. Natural Deep Eutectic Solvents as New Potential Media for Green Technology. Anal. Chim. Acta 2013, 766, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Craveiro, R.; Aroso, I.; Flammia, V.; Carvalho, T.; Viciosa, M.T.; Dionísio, M.; Barreiros, S.; Reis, R.L.; Duarte, A.R.C.; Paiva, A. Properties and Thermal Behavior of Natural Deep Eutectic Solvents. J. Mol. Liq. 2016, 215, 534–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espino, M.; de los Ángeles Fernández, M.; Gomez, F.J.V.; Silva, M.F. Natural Designer Solvents for Greening Analytical Chemistry. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2016, 76, 126–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andruch, V.; Kalyniukova, A.; Płotka-Wasylka, J.; Jatkowska, N.; Snigur, D.; Zaruba, S.; Płatkiewicz, J.; Zgoła-Grześkowiak, A.; Werner, J. Application of Deep Eutectic Solvents in Analytical Sample Pretreatment (Update 2017–2022). Part A: Liquid Phase Microextraction. Microchem. J. 2023, 189, 108509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werner, J.; Zgoła-Grześkowiak, A.; Płatkiewicz, J.; Płotka-Wasylka, J.; Jatkowska, N.; Kalyniukova, A.; Zaruba, S.; Andruch, V. Deep Eutectic Solvents in Analytical Sample Preconcentration Part B: Solid-Phase (Micro)Extraction. Microchem. J. 2023, 191, 108898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomé, L.I.N.; Baião, V.; da Silva, W.; Brett, C.M.A. Deep Eutectic Solvents for the Production and Application of New Materials. Appl. Mater. Today 2018, 10, 30–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagle, D.V.; Zhao, H.; Baker, G.A. Deep Eutectic Solvents: Sustainable Media for Nanoscale and Functional Materials. Acc. Chem. Res. 2014, 47, 2299–2308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, B.; Zhang, H.; Row, K.H. Application of Deep Eutectic Solvents in the Extraction and Separation of Target Compounds from Various Samples. J. Sep. Sci. 2015, 38, 1053–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carriazo, D.; Serrano, M.C.; Gutiérrez, M.C.; Ferrer, M.L.; del Monte, F. Deep-Eutectic Solvents Playing Multiple Roles in the Synthesis of Polymers and Related Materials. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012, 41, 4996–5014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, X.-J.; Zhang, L.-S.; Song, W.-F.; Huang, Y.-P.; Liu, Z.-S. A Polymer Monolith Incorporating Stellate Mesoporous Silica Nanospheres for Use in Capillary Electrochromatography and Solid Phase Microextraction of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons and Organic Small Molecules. Microchim. Acta 2018, 185, 444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Song, Y.; Xu, J.; Fan, J. A Hydrophobic Deep Eutectic Solvent Mediated Sol-Gel Coating of Solid Phase Microextraction Fiber for Determination of Toluene, Ethylbenzene and o-Xylene in Water Coupled with GC-FID. Talanta 2019, 195, 298–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Han, Y.; Cao, J.; Yan, H. Headspace Solid-Phase-Microextraction Using a Graphene Aerogel for Gas Chromatography–Tandem Mass Spectrometry Quantification of Polychlorinated Naphthalenes in Shrimp. J. Chromatogr. A 2022, 1672, 463012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Wang, Z.; Han, D.; Han, Y.; Yan, H. A Three-Dimensional Hierarchical Porous Graphene Aerogel as a Fiber Coating for Headspace Solid-Phase Microextraction: Enhancing the Enrichment and Detection of Polychlorinated Naphthalenes in Fish. Talanta 2024, 274, 125913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monnier, A.; Díaz-Álvarez, M.; Turiel, E.; Martín-Esteban, A. Evaluation of Deep Eutectic Solvents in the Synthesis of Molecularly Imprinted Fibers for the Solid-Phase Microextraction of Triazines in Soil Samples. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2024, 416, 1337–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Chai, M.-H.; Wei, Z.-H.; Chen, W.-J.; Liu, Z.-S.; Huang, Y.-P. Deep Eutectic Solvents-Based Polymer Monolith Incorporated with Titanium Dioxide Nanotubes for Specific Recognition of Proteins. Anal. Chim. Acta 2020, 1139, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Li, W.; Chen, Z. Solid Phase Microextraction with Poly(Deep Eutectic Solvent) Monolithic Column Online Coupled to HPLC for Determination of Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs. Anal. Chim. Acta 2018, 1018, 111–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, G.; Row, K.H. Selective Extraction of 3,4-Dihydroxybenzoic Acid in Ilex Chinensis Sims by Meticulous Mini-Solid-Phase Microextraction Using Ternary Deep Eutectic Solvent-Based Molecularly Imprinted Polymers. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2018, 410, 7849–7858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mirzajani, R.; Kardani, F.; Ramezani, Z. Fabrication of UMCM-1 Based Monolithic and Hollow Fiber—Metal-Organic Framework Deep Eutectic Solvents/Molecularly Imprinted Polymers and Their Use in Solid Phase Microextraction of Phthalate Esters in Yogurt, Water and Edible Oil by GC-FID. Food Chem. 2020, 314, 126179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kardani, F.; Khezeli, T.; Shariati, S.; Hashemi, M.; Mahdavinia, M.; Jelyani, A.Z.; Rashedinia, M.; Noori, S.M.A.; Karimvand, M.N.; Ramezankhani, R. Application of Novel Metal Organic Framework-Deep Eutectic Solvent/Molecularly Imprinted Polymer Multiple Monolithic Fiber for Solid Phase Microextraction of Amphetamines and Modafinil in Unauthorized Medicinal Supplements with GC-MS. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2024, 242, 116005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kardani, F.; Mirzajani, R.; Tamsilian, Y.; Kiasat, A. The Residual Determination of 39 Antibiotics in Meat and Dairy Products Using Solid-Phase Microextraction Based on Deep Eutectic Solvents@UMCM-1 Metal-Organic Framework /Molecularly Imprinted Polymers with HPLC-UV. Food Chem. Adv. 2023, 2, 100173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asghari, Z.; Sereshti, H.; Soltani, S.; Rashidi Nodeh, H.; Hossein Shojaee AliAbadi, M. Alginate Aerogel Beads Doped with a Polymeric Deep Eutectic Solvent for Green Solid-Phase Microextraction of 5-Hydroxymethylfurfural in Coffee Samples. Microchem. J. 2022, 181, 107729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi, M.; Dadfarnia, S.; Haji Shabani, A.M. Hollow FIbre-Supported Graphene Oxide Nanosheets Modified with a Deep Eutectic Solvent to Be Used for the Solid-Phase Microextraction of Silver Ions. Int. J. Environ. Anal. Chem. 2018, 98, 124–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asiabi, H.; Yamini, Y.; Shamsayei, M.; Mehraban, J.A. A Nanocomposite Prepared from a Polypyrrole Deep Eutectic Solvent and Coated onto the Inner Surface of a Steel Capillary for Electrochemically Controlled Microextraction of Acidic Drugs Such as Losartan. Microchim. Acta 2018, 185, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Ruiz, I.; Lasarte-Aragonés, G.; Lucena, R.; Cárdenas, S. Deep Eutectic Solvent Coated Paper: Sustainable Sorptive Phase for Sample Preparation. J. Chromatogr. A 2023, 1698, 464003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werner, J.; Zgoła-Grześkowiak, A.; Grześkowiak, T. Development of Novel Thin-film Solid-phase Microextraction Materials Based on Deep Eutectic Solvents for Preconcentration of Trace Amounts of Parabens in Surface Waters. J. Sep. Sci. 2022, 45, 1374–1384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werner, J.; Grześkowiak, T.; Zgoła-Grześkowiak, A. A Polydimethylsiloxane/Deep Eutectic Solvent Sol-Gel Thin Film Sorbent and Its Application to Solid-Phase Microextraction of Parabens. Anal. Chim. Acta 2022, 1202, 339666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chabowska, A.; Werner, J.; Zgoła-Grześkowiak, A.; Płatkiewicz, J.; Frankowski, R.; Płotka-Wasylka, J. Development of Thin Film SPME Sorbents Based on Deep Eutectic Solvents and Their Application for Isolation and Preconcentration of Endocrine-Disrupting Compounds Leaching from Diapers to Urine. Microchem. J. 2024, 199, 110023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werner, J.; Mysiak, D. Development of Thin Film Microextraction with Natural Deep Eutectic Solvents as ‘Eutectosorbents’ for Preconcentration of Popular Sweeteners and Preservatives from Functional Beverages and Flavoured Waters. Molecules 2024, 29, 4573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werner, J.; Płatkiewicz, J.; Mysiak, D.; Ławniczak, Ł.; Płotka-Wasylka, J. Natural Deep Eutectic Solvent Mixed with Powdered Cork as a Green Approach for Thin Film SPME and Determination of Selected Ultraviolet Filters in Lake Waters. Green Anal. Chem. 2025, 13, 100256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quintanilla, I.; Fontàs, C.; Anticó, E. Deep Eutectic Solvents Incorporated in a Polymeric Film for Organophosphorus Pesticide Microextraction from Water Samples. Anal. Chim. Acta 2024, 1318, 342940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghani, M.; Jafari, Z.; Raoof, J.B. Porous Agarose/Chitosan/Graphene Oxide Composite Coupled with Deep Eutectic Solvent for Thin Film Microextraction of Chlorophenols. J. Chromatogr. A 2023, 1694, 463899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Werner, J.; Frankowski, R.; Grześkowiak, T.; Zgoła-Grześkowiak, A. Green Sorbents in Sample Preparation Techniques—Naturally Occurring Materials and Biowastes. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2024, 176, 117772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bystrzanowska, M.; Tobiszewski, M. Assessment and design of greener deep eutectic solvents—A multicriteria decision analysis. J. Mol. Liq. 2021, 321, 114878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Environmental Methods Index (NEMI). Available online: https://www.nemi.gov/home/ (accessed on 15 December 2025).

- Gałuszka, A.; Migaszewski, M.; Konieczka, P.; Namieśnik, J. Analytical Eco-Scale for assessing the greenness of analytical procedures. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2012, 37, 61–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Płotka-Wasylka, J. A new tool for the evaluation of the analytical procedure: Green Analytical Procedure Index. Talanta 2018, 181, 204–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Płotka-Wasylka, J.; Wojnowski, W. Complementary green analytical procedure index (ComplexGAPI) and software. Green Chem. 2021, 23, 8657–8665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansour, F.R.; Omer, K.M.; Płotka-Wasylka, J. A total scoring system and software for complex modified GAPI (ComplexMoGAPI) application in the assessment of method greenness. Green Anal. Chem. 2024, 10, 100126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojnowski, W.; Tobiszewski, M.; Pena-Pereira, F.; Psillakis, E. AGREEprep—Analytical greenness metric for sample preparation. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2022, 149, 116553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Martín, R.; Gutiérrez-Serpa, A.; Pino, V.; Sajid, M. A tool to assess analytical sample preparation procedures: Sample preparation metric of sustainability. J. Chromatogr. A 2023, 1707, 464291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caldeira, C.; Abbate, E.; Moretti, C.; Mancini, L.; Sala, S. Safe and sustainable chemicals and materials: A review of sustainability assessment frameworks. Green Chem. 2024, 26, 7456–7477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaib, Q.; Eckelman, M.J.; Yang, Y.; Kyung, D. Are deep eutectic solvents really green?: A life-cycle perspective. Green Chem. 2022, 24, 7924–7930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nejrotti, S.; Antenucci, A.; Pontremoli, C.; Gontrani, L.; Barbero, N.; Carbone, M.; Bonomo, M. Critical Assessment of the Sustainability of Deep Eutectic Solvents: A Case Study on Six Choline Chloride-Based Mixtures. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 47449–47461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shayestehpour, O.; Zahn, S. Efficient Molecular Dynamics Simulations of Deep Eutectic Solvents with First-Principles Accuracy Using Machine Learning Interatomic Potentials. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2023, 19, 8732–8742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahavishnu, G.; Kannaiyan, S.K. Using COSMO-RS in the design of deep eutectic solvents for improving the solubilization of water insoluble drugs. J. Mol. Liq. 2025, 436, 128211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Peng, D.; Alhadid, A.; Minceva, M. Assessment of COSMO-RS for Predicting Liquid–Liquid Equilibrium in Systems Containing Deep Eutectic Solvents. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2024, 63, 11110–11120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Flores, F.J.; Ramírez-Márquez, C.; González-Campos, J.B.; Ponce-Ortega, J.M. Machine Learning for Predicting and Optimizing Physicochemical Properties of Deep Eutectic Solvents: Review and Perspectives. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2025, 64, 3103–3117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Garg, A.; Li, L.; Chatterjee, I.; Lee, B.; Garg, A. Machine learning for deep eutectic solvents: Advances in property prediction and molecular design. J. Mol. Liq. 2025, 437, 128317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, S.A.; Shamsaei, D.; Ocaña-Rios, I.; Anderson, J.L. Batch Scale Production of 3D Printed Extraction Sorbents Using a Low-Cost Modification to a Desktop Printer. Anal. Chem. 2023, 95, 13417–13422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szynkiewicz, D.; Ulenberg, S.; Georgiev, P.; Hejna, A.; Mikolaszek, B.; Bączek, T.; Baron, G.V.; Denayer, J.F.M.; Desmet, G.; Belka, M. Development of a 3D-Printable, Porous, and Chemically Active Material Filled with Silica Particles and its Application to the Fabrication of a Microextraction Device. Anal. Chem. 2023, 95, 11632–11640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Díaz-Álvarez, M.; Turiel, E.; Martín-Esteban, A. Natural deep eutectic solvent-based liquid phase microextraction in a 3D-Printed millifluidic flow cell for the on-line determination of thiabendazole in juice samples. Anal. Chim. Acta 2025, 1339, 343617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ningsun Zhou, S.; Zhang, X.; Ouyang, G.; Es-haghi, A.; Pawliszyn, J. On-Fiber Standardization Technique for Solid-Coated Solid-Phase Microextraction. Anal. Chem. 2007, 79, 1221–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, M.M.; Loong Yiin, C.; Mun Lock, S.S.; Fui Chin, B.L.; Othman, I.; Syuhada binti Ahmad Zauzi, N.; Herng Chan, Y. Natural deep eutectic solvents (NADES) for sustainable extraction of bioactive compounds from medicinal plants: Recent advances, challenges, and future directions. J. Mol. Liq. 2025, 425, 127202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Argüello, P.; Martín-Esteban, A. Ecotoxicological assessment of different choline chloride-based natural deep eutectic solvents: In vitro and in vivo approaches. Environ. Res. 2025, 284, 122202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Extraction Method | Support | Coating Material | DES (HBA:HBD, Molar Ratio) | Approach of DES | Reuse of Material | Analytes | Samples | Detection | EF | RSD [%] | Environmental Metrics | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SPME | Monolithic column | SMSN/BMA/EGDMA/ DES | (ChCl:EG, 1:2) | Porogen | - * | PAHs NSAIDs | Lake waters | CEC | - * | <3.0 | Not reported | [68] |

| SPME | Fiber | Gel-sol PDMS-DES | (EP:MTOACl, 2:1) | Porogen | >60 times | Toluene Ethylbenzene o-Xylene | Waters | GC-FID | 7.6 20.4 17.1 | 6.7 4.5 4.2 | Not reported | [69] |

| SPME | Fiber | GA/NADES | (ChCl:Glu, 1:2) | Porogen | - * | PCNs | Shrimp | GC-MS/MS | 410–1553 | 5.8–20 | Environmentally friendly method | [70] |

| SPME | Fiber | 3D DES-GA | (ChCl:urea, 1:2) | Porogen | ≥160 times | PCNs | Fish | GC-MS/MS | 1225–4652 | 2.4–6.6 | Environmentally friendly sorbent synthesis | [71] |

| SPME | Monolithic fiber | DES/MIP | (FA:menthol, 1:1) | Porogen | 15 times | Herbicides | Soils | HPLC-DAD | - * | - * | Analytical Eco-Scale 71 out of 100 | [72] |

| SPME | Monolithic column | TiO2-poly(GMA-DES-EGDMA) | (ChCl:MAA, 1:2) | Functional monomer for polymer synthesis | 24 times | Proteins | Rat liver | HPLC-MS/MS | 22–28 | 2.2–3.1 | Not reported | [73] |

| IT-SPME | Monolithic column | poly(DES-EGDMA) | (ChCl:IA, 1:1.5) | Functional monomer for polymer synthesis | - * | NSAIDs | Plasma, water | HPLC-UV | 98–103 | 1.9–4.3 | Not reported | [74] |

| mini-SPME | Needle of syringe | TDES-MIP | (ChCl:3,4-DHBA:EG, 1:1:2) | Template and functional monomer in MIPs synthesis | 6 times | 3,4-DHBA | Ilex chinensis Sims | HPLC-UV | - * | <4.2 | Not reported | [75] |

| HFLMP-SPME | Hollow fiber, Monolithic fiber | MOF-DES/MIP | (ChCl:EG, 2:1) | Substrate for MOF | >80 times | Phthalate esters | Yogurt, water, edible oil | GC-FID | 441–446 | 2.6–3.4 | Not reported | [76] |

| MMF-SPME | Monolithic fiber | MOF-DES/MIP | (ChCl:EG, 2:1) | Substrate for MOF | 60 times | Amphetamines Modafinil | Unauthorized medical supplements | GC-MS | 159–163 | 1.0–4.7 | Green extraction solvent | [77] |

| MMF-SPME | Monolithic fiber | MOF-DES/MIP | (ChCl:EG, 2:1) | Substrate for MOF | - * | 35 Antibiotics | Meat, dairy products | HPLC-UV | 162–193 | 2.8–5.6 | Not reported | [78] |

| SPME | Aerogel beads | CA/DES | (ChCl:PEG, 1:1) | Sorbent component | - * | HMF | Coffee | HPLC-UV | - * | 2.5–4.7 | ComplexGAPI Analytical Eco-Scale | [79] |

| HF-SPME | Hollow fiber | GO/DES | (ChCl:thiourea, 1:2) | Sorbent component | - * | Ag(I) | Water, ore, hair | FAAS | 200 | 3.5 | Environmentally friendly method | [80] |

| EC-IT-SPME | Capillary tubes | PPy/DES | (ChCl:urea, 1:2) | Sorbent component | >450 times | Losartan | Water, urine, plasma | HPLC-UV | - * | 2.4–4.6 | Not reported | [81] |

| TF-SPME | paper | DES | (thymol:vanillin, 1:1) | Sorbent | Not reusable | Herbicides | Creek, underground well water | GC-MS | - * | 7.4–14.7 | Green extraction solvent | [82] |

| TF-SPME | Stainless steel mesh | DES | (THTDPCl:DcOH, 1:2) | Sorbent | 3 times | Parabens | Lake water, river water | HPLC-UV | 166–183 | 3.6–6.5 | Environmentally friendly method | [83] |

| TF-SPME | Stainless steel mesh | Sol–gel PDMS/DES | (THTDPCl:DcOH, 1:2) | Sorbent component | 10 times | Parabens | Lake water, river water | HPLC-UV | 174–186 | 2.7–4.5 | Not reported | [84] |

| TF-SPME | Fiberglass mesh | PDMS/DES | (THTDPCl:DcOH, 1:3) | Sorbent component | - * | Parabens, Preservatives | Diapers | LC-MS/MS | - * | 2.5–10.3 | GAPI | [85] |

| TF-SPME | Fiberglass mesh | NADES | (AcChCl:DcOH, 1:3) | Sorbent | 16 times | Sweeteners, Preservatives | Functional beverages, flavored waters | HPLC-UV | 59–64 | 5.7–7.4 | Complex-MoGAPI 84 out of 100 | [86] |

| TF-SPME | Teflon® mesh | NADES/ biowaste cork | (BeCl:EiOH, 1:3) | Sorbent component | 10 times | Lake waters | UV filters | HPLC-UV | - * | 3.6–7.4 | ComplexMoGAPI 85 out of 100 | [87] |

| S-TFME PT-TFME | Suspended film Pipette tip | CTA/DES | (DcA:lidocaine, 2:1) | Sorbent component | 5 times | Organophosphorus pesticides | Water | GC-MS | - * | 3–14 | Environmentally friendly method | [88] |

| TF-SPME | film | ACGO | (ChCl:TEACl, 1:1) | Solvent to desorption | - * | Chlorophenols | Agricultural waste water, honey, tea | GC-MS | 33.4–35.8 | 2.8–5.9 | Not reported | [89] |

| Advantages | Disadvantages | |

|---|---|---|

| DESs in SPME |

|

|

| Other sorbents in SPME |

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Mysiak, D.; Werner, J. An Ecologically Sustainable Approach to Solid-Phase Microextraction Techniques Using Deep Eutectic Solvents. Sustainability 2026, 18, 402. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010402

Mysiak D, Werner J. An Ecologically Sustainable Approach to Solid-Phase Microextraction Techniques Using Deep Eutectic Solvents. Sustainability. 2026; 18(1):402. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010402

Chicago/Turabian StyleMysiak, Daria, and Justyna Werner. 2026. "An Ecologically Sustainable Approach to Solid-Phase Microextraction Techniques Using Deep Eutectic Solvents" Sustainability 18, no. 1: 402. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010402

APA StyleMysiak, D., & Werner, J. (2026). An Ecologically Sustainable Approach to Solid-Phase Microextraction Techniques Using Deep Eutectic Solvents. Sustainability, 18(1), 402. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010402