Green Credit Policy, ESG Performance, and Corporate Capital Structure—Empirical Evidence from Chinese Listed Companies

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Hypothesis Research

2.1. Green Credit Policy and Enterprise Capital Structure

2.2. ESG Performance and Corporate Capital Structure

3. Research Design

3.1. Sample and Date

3.2. Defnition of Variables

3.2.1. Explained Variables

3.2.2. Explanatory Variables

3.2.3. Control Variables

3.2.4. Moderating Variables

3.3. Model Specifcation

4. Empirical Results and Analysis

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

4.2. Parallel Trend Test

4.3. Benchmark Regression

4.4. Robustness Test

4.4.1. Changing the Observation Window

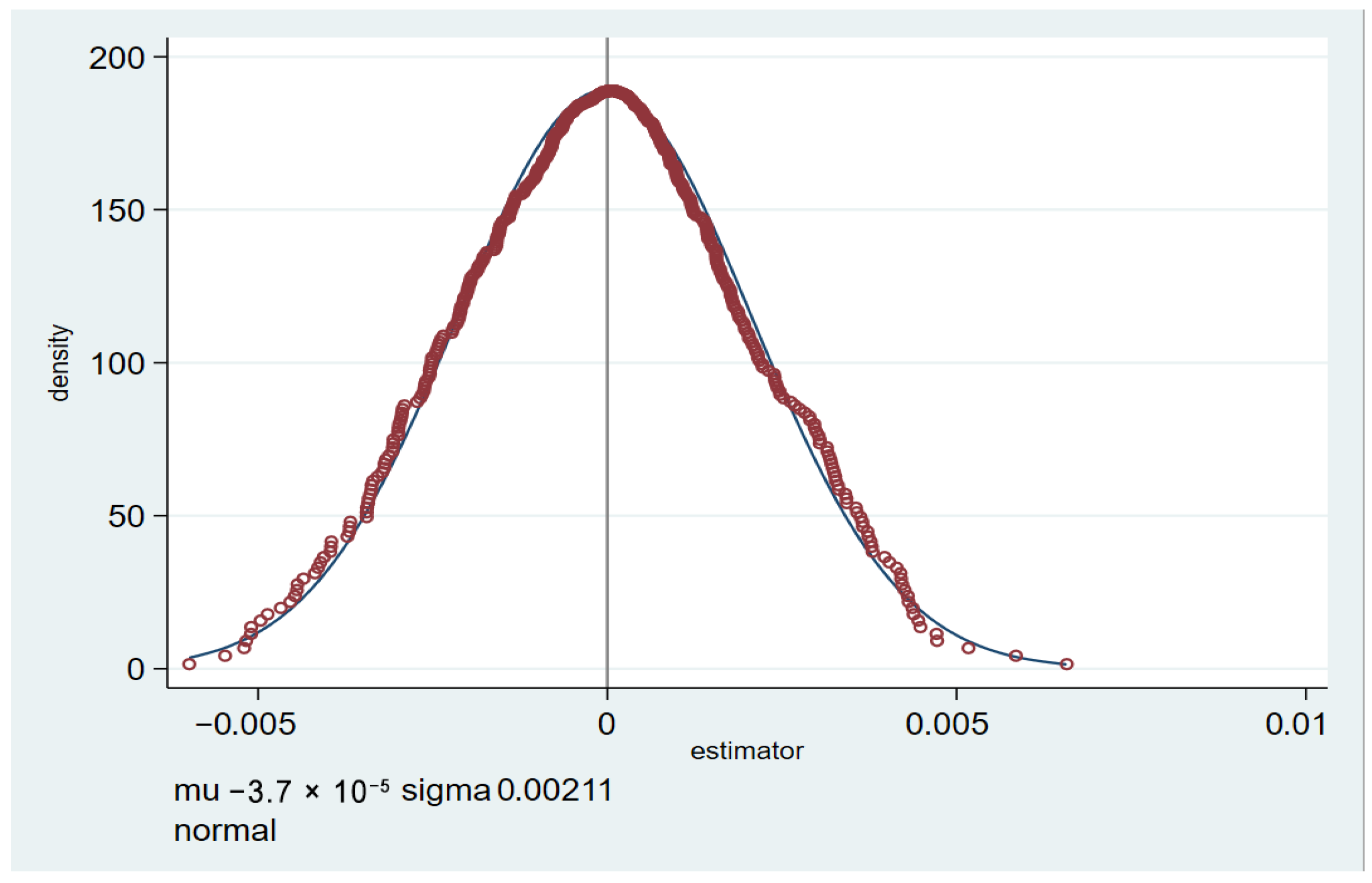

4.4.2. Placebo Test

4.5. Heterogeneity Test

4.5.1. Heterogeneity Analysis of Nature of Ownership

4.5.2. Regional Heterogeneity Analysis

5. Further Discussion

Mediating Effect

6. Conclusions and Recommendations

6.1. Conclusions

6.2. Recommendations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Su, D.; Lian, L. Does Green Credit Policy Affect Corporate Financing and Investment? Evidence from Publicly Listed Firms in Pollution—Intensive Industries. J. Financ. Res. 2018, 462, 123–137. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, H.; Wang, X.; Tan, C. Green Credit Policy, Incremental Bank Loans and Environmental Protection Effect. Account. Res. 2019, 3, 88–95. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Q. Has China’s Green Credit Policy Been Implemented? An Analysis of Loan Scale and Costs Based on “Two Highs and One Surplus” Enterprises. Contemp. Financ. Econ. 2019, 3, 118–129. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.; Ruan, Y.; Tang, Y. Research on the Impact of Green Credit Policies on the Cost of Corporate Debt Financing. Friends Account. 2025, 21, 92–99. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Hu, J. Do Green Credit Policies Inhibit the Investment of Heavy Polluting Enterprises? Shandong Soc. Sci. 2022, 33, 138–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S. The Impact of Corporate ESG Performance on Credit Financing. Master’s Thesis, Fujian Normal University, Fujian, China, 2023. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Xie, M.; Guo, C. Does Firm ESG Performance Influence Bank Credit Decisions? Empirical Evidence from A-share Listed Firms in China. Financ. Econ. Res. 2023, 38, 97–114. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, B. Green Credit, Corporate Social Responsibility Disclosure and Debt Financing Cost: Empirical Study on Heavy Pollution Enterprises Listed in A-share Market from 2011 to 2017. Financ. Theory Pract. 2019, 40, 47–54. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Dong, Y.; Pan, H. Green Credit Policy, ESG Performance, and Capital Structure Adjustment of Highly- Polluting Firms. Resour. Ind. 2024, 26, 75–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, W. A Probe into the Connotation, Mechanism and Practice of Green Finance. Econ. Surv. 2008, 25, 156–158. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Q.; Wang, L. Can Green Credit Policies Curb the Debt of Heavily Polluting Enterprises? Policy effect evaluation based on counter-factual analysis. Sci. Technol. Ind. 2023, 23, 26–32. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z. Research on the Impact of Green Credit on the Investment and Financing Behaviour of Heavy Pollution Enterprises. Huabei Financ. 2023, 12, 25–43. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Liu, M.; Zhao, S.; Wei, Z. How does enterprise ESG performance affect green investor entry? J. Chongqing Univ. Technol. (Soc. Sci.) 2024, 38, 43–58. [Google Scholar]

- Flammer, C.; Bansal, P. Does a long-term orientation create value? Evidence from a regression discontinuity. Strateg. Manag. J. 2017, 38, 1827–1847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, L.; Xin, J. Investor Concerns, ESG Information Disclosure and Corporate Green Technology Innovation. Econ. Probl. 2024, 6, 115–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faulkender, M.; Flannery, M.J.; Hankins, K.W.; Smith, J.M. Cash flows and leverage adjustments. J. Financ. Econ. 2012, 103, 632–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Zou, F.; Wang, Z. Relationships among profitability, technology innovation capability and capital structure—An empirical analysis based on high-tech firms. Sci. Res. Manag. 2014, 35, 48–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, H. Study on the Implementation of Green Loan Policy and its Effects in China—An Empirical Study Based on Paper, Mining and Power Industries. Collect. Essays Financ. Econ. 2013, 1, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, F. Research on the Impact of Green Credit Policyon the Low-Carbon Transition of Industry—Evidence Based on Industry Provincial Panel. Master’s Thesis, Guangxi University, Nanning, China, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Type | Variables | Symbol | Measurement Methods |

|---|---|---|---|

| Explained variable | Financial leverage | Lev | Total liabilities divided by total assets |

| Explanatory Variable | Double Difference Variables | did | time × treat |

| Time dummy variable | time | 0 before 2012; 1 in 2012 and beyond | |

| Grouping dummy variables | treat | 1 for heavily polluting firms; 0 for non-heavily polluting firms | |

| Control variable | Firm Size | Size | Natural logarithm of total assets |

| Collateral capacity | Far | Fixed Assets divided by Total Assets | |

| Profitability | Roe | Net profit divided by net assets | |

| Growth Opportunities | Growth | (Current year’s total operating income—last year’s total operating income)/last year’s total operating income | |

| Degree of financial distress | Retain | Retained Earnings/Total Assets | |

| Shareholding Concentration | Sharehold | Shareholding of the largest shareholder | |

| Moderating Variables | ESG performance | ESG | ESG evaluation data from CNRDS database |

| Heterogeneity Analysis Variables | Nature of shareholding | Soe | 1 for state-owned enterprises; 0 for non-state-owned enterprises |

| Regional Nature | Region | 0 for Eastern Region; 1 for Central Region; 2 for Western Region |

| Variables | N | Mean | Sd | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lev | 27,967 | 0.464 | 0.201 | 0.0647 | 0.894 |

| ESG | 27,967 | 26.31 | 10.88 | 7.287 | 58.28 |

| Size | 27,967 | 22.45 | 1.342 | 19.84 | 26.40 |

| Far | 27,967 | 0.234 | 0.172 | 0.00180 | 0.725 |

| Roe | 27,967 | 0.0475 | 0.150 | −0.860 | 0.328 |

| Growth | 27,967 | 0.151 | 0.396 | −0.561 | 2.505 |

| Retain | 27,967 | 0.143 | 0.210 | −0.907 | 0.600 |

| Sharehold | 27,967 | 0.343 | 0.149 | 0.0832 | 0.741 |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Lev | Lev | Lev | Lev |

| did | −0.035 *** | −0.035 *** | −0.025 *** | −0.024 *** |

| (0.004) | (0.004) | (0.004) | (0.004) | |

| Size | 0.048 *** | 0.056 *** | ||

| (0.001) | (0.002) | |||

| Far | −0.013 | −0.033 *** | ||

| (0.008) | (0.009) | |||

| Roe | −0.046 *** | −0.073 *** | ||

| (0.007) | (0.007) | |||

| Growth | 0.009 *** | 0.005 *** | ||

| (0.002) | (0.002) | |||

| Retain | −0.226 *** | −0.175 *** | ||

| (0.007) | (0.007) | |||

| Sharehold | 0.001 *** | 0.000 *** | ||

| (0.000) | (0.000) | |||

| _cons | 0.457 *** | 0.454 *** | −0.548 *** | −0.702 *** |

| (0.004) | (0.004) | (0.024) | (0.034) | |

| id | NO | YES | NO | YES |

| year | NO | YES | NO | YES |

| N | 27,967.000 | 27,967.000 | 22,999.000 | 22,999.000 |

| r2_a | −0.066 | 0.021 |

| (1) Lagged by Two Periods | (2) Lagged Three Periods | |

|---|---|---|

| Variables | Lev | Lev |

| L2.did | −0.015 *** | |

| (0.005) | ||

| L3.did | −0.011 ** | |

| (0.005) | ||

| Size | 0.046 *** | 0.043 *** |

| (0.002) | (0.003) | |

| Far | 0.003 | −0.003 |

| (0.014) | (0.016) | |

| Roe | −0.043 *** | −0.037 *** |

| (0.010) | (0.010) | |

| Growth | 0.006 ** | 0.008 *** |

| (0.003) | (0.003) | |

| Retain | −0.175 *** | −0.176 *** |

| (0.010) | (0.011) | |

| Sharehold | 0.001 *** | 0.001 *** |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | |

| _cons | −0.516 *** | −0.459 *** |

| (0.052) | (0.057) | |

| id | YES | YES |

| year | YES | YES |

| N | 10,802.000 | 9354.000 |

| r2_a | 0.002 | −0.015 |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Lev Full Sample | Lev State-Owned Enterprises | Lev Non-State-Owned Enterprises |

| did | −0.024 *** | −0.029 *** | −0.011 |

| (0.004) | (0.005) | (0.008) | |

| Size | 0.056 *** | 0.007 | −0.004 |

| (0.002) | (0.008) | (0.009) | |

| Far | −0.033 *** | −0.074 *** | −0.055 *** |

| (0.009) | (0.006) | (0.009) | |

| Roe | −0.073 *** | 0.055 *** | 0.046 *** |

| (0.007) | (0.002) | (0.002) | |

| Growth | 0.005 *** | −0.054 *** | 0.002 |

| (0.002) | (0.011) | (0.014) | |

| Retain | −0.175 *** | −0.092 *** | −0.044 *** |

| (0.007) | (0.009) | (0.010) | |

| Sharehold | 0.000 *** | 0.005 * | 0.006 ** |

| (0.000) | (0.002) | (0.003) | |

| _cons | −0.702 *** | −0.202 *** | −0.176 *** |

| (0.034) | (0.011) | (0.010) | |

| id | YES | YES | YES |

| year | YES | YES | YES |

| N | 22,999.000 | 11,704.000 | 10,802.000 |

| r2_a | 0.021 | 0.028 | 0.001 |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Eastern | Central | Western |

| did | −0.020 *** | −0.024 *** | −0.020 * |

| (0.005) | (0.008) | (0.011) | |

| treat | 0.015 ** | 0.012 | 0.006 |

| (0.008) | (0.012) | (0.016) | |

| time | −0.070 *** | −0.059 *** | −0.113 *** |

| (0.006) | (0.010) | (0.015) | |

| Size | 0.058 *** | 0.050 *** | 0.058 *** |

| (0.002) | (0.003) | (0.004) | |

| Far | −0.019 | −0.044 ** | −0.042 ** |

| (0.012) | (0.018) | (0.021) | |

| ROE | −0.048 *** | −0.128 *** | −0.094 *** |

| (0.009) | (0.014) | (0.017) | |

| Growth | 0.003 | 0.008 ** | 0.004 |

| (0.002) | (0.004) | (0.005) | |

| Retain | −0.183 *** | −0.177 *** | −0.127 *** |

| (0.009) | (0.015) | (0.018) | |

| Sharehold | 0.032 ** | 0.049 ** | 0.046 |

| (0.013) | (0.022) | (0.028) | |

| _cons | −0.771 *** | −0.553 *** | −0.717 *** |

| (0.044) | (0.070) | (0.091) | |

| id | YES | YES | YES |

| year | YES | YES | YES |

| N | 14,977.000 | 4607.000 | 3321.000 |

| r2_a | 0.018 | 0.040 | −0.000 |

| Chow Test | 43.04 | ||

| p-value | 0.0000 |

| (1) | (2) | |

|---|---|---|

| Variables | Lev | Lev |

| did | −0.024 *** | −0.020 *** |

| (0.004) | (0.004) | |

| ESG | 0.000 *** | |

| (0.000) | ||

| did × ESG | −0.000 * | |

| (0.000) | ||

| Size | 0.056 *** | 0.056 *** |

| (0.002) | (0.002) | |

| Far | −0.033 *** | −0.033 *** |

| (0.009) | (0.009) | |

| ROE | −0.073 *** | −0.073 *** |

| (0.007) | (0.007) | |

| Growth | 0.005 *** | 0.005 *** |

| (0.002) | (0.002) | |

| Retain | −0.175 *** | −0.174 *** |

| (0.007) | (0.007) | |

| Sharehold | 0.000 *** | 0.000 *** |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | |

| _cons | −0.702 *** | −0.690 *** |

| (0.034) | (0.034) | |

| id | YES | YES |

| year | YES | YES |

| N | 22,999.000 | 22,999.000 |

| r2_a | 0.021 | 0.022 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Wang, N.; Wan, Y.; Yang, K. Green Credit Policy, ESG Performance, and Corporate Capital Structure—Empirical Evidence from Chinese Listed Companies. Sustainability 2026, 18, 376. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010376

Wang N, Wan Y, Yang K. Green Credit Policy, ESG Performance, and Corporate Capital Structure—Empirical Evidence from Chinese Listed Companies. Sustainability. 2026; 18(1):376. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010376

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Nan, Yuanyuan Wan, and Kai Yang. 2026. "Green Credit Policy, ESG Performance, and Corporate Capital Structure—Empirical Evidence from Chinese Listed Companies" Sustainability 18, no. 1: 376. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010376

APA StyleWang, N., Wan, Y., & Yang, K. (2026). Green Credit Policy, ESG Performance, and Corporate Capital Structure—Empirical Evidence from Chinese Listed Companies. Sustainability, 18(1), 376. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010376