1. Introduction

The rapid rise in the digital economy is marked by technologies such as the Internet of Things, artificial intelligence, and big data, among others, which are fundamentally reorganizing economic and social mechanisms [

1]. At the same time, efforts toward achieving the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) aim to address environmental degradation, social inequality, and economic instability [

2]. In China, these two transformative forces are occurring with unprecedented scale and speed [

3]. The government actively promotes initiatives such as “Digital China” and “Ecological Civilization,” alongside its commitment to the SDGs. This creates a critical context for investigating the synergies and tensions between digitalization and sustainability [

4]. This research aims to empirically analyze the complex interconnections between the expansion of China’s digital economy and its progress toward achieving the SDGs, with the specific objective of identifying the pathways through which technological advancement can support sustainable outcomes [

5].

A substantial body of literature has established theoretical links between information and communication technology (ICT) and sustainable development [

6]. Seminal works have argued that digitalization can enable sustainability. This is primarily through mechanisms such as dematerialization, enhanced efficiency, and circular economy models [

7]. Recent empirical studies have begun to quantify these relationships. They often find a positive correlation between ICT development and environmental or economic indicators [

8]. For example, research shows that digital tools can optimize energy grids and reduce carbon emissions in smart city contexts. However, a significant gap persists. Much existing scholarship remains siloed, focusing on isolated environmental aspects (like CO

2 emissions) or broad economic gains. This fails to capture the holistic multi-dimensional nature of the 17 SDGs [

9]. Furthermore, causal identification is often insufficient. While many studies find correlations, few establish the robust causal pathways required for effective policy design [

10].

Despite the advances, the existing literature lacks a nuanced nation-specific analysis for a context as unique and influential as China. While some studies have examined China’s digital economy [

11] or its sustainability policies separately, comprehensive analyses that integrally link the two are scarce. The Chinese model, with its distinct state-led approach to technological development and sustainability governance, may yield interconnections that differ significantly from patterns observed in Western economies [

12]. The context-dependent nature of the digitalization–sustainability nexus is frequently overlooked in generalized models, resulting in a critical knowledge gap [

13]. Understanding these dynamics within China is not merely an academic exercise but a necessity, given the country’s profound impact on global digital trends and sustainable development progress.

This research aims to fill these gaps by providing a comprehensive and forward-looking analysis tailored to the Chinese context. We move beyond siloed approaches and construct a robust framework that evaluates the impact of digital economy indicators across the key pillars of eco-economic sustainability: environmental and economic performance. The study’s originality stems from its rigorous econometric design. This approach enables us to address a pivotal question: What specific causal mechanisms (both direct and mediated) link the digital economy to SDG performance, and how do they vary across different governance contexts? This work makes three theoretical contributions. First, it contributes to the discussion on technology and sustainability by testing current theories in a unique state-capitalist context. This may result in a new contextual model. Second, it adds value to the sustainable development community by providing a methodological approach. We apply advanced causal inference techniques to SDG evaluation, helping to transition the field from description to foresight. Lastly, it empirically illuminates the causal mechanisms of green digitalization, employing instrumental variable (IV) techniques to address endogeneity and provide unbiased estimates of the mechanism’s strength and sustainable performance. The applied contributions are also important. The findings will provide Chinese policymakers with a solid evidence base for creating more effective and integrated policies that promote digital innovation and sustainability without unintended side effects.

The structure of this paper is as follows:

Section 2 provides a comprehensive literature review. It synthesizes knowledge on the digital economy, the SDGs, and their intersections.

Section 3 describes the research methods, including the data sources, variable selection, and the predictive modeling techniques used.

Section 4 reports the key findings from our empirical analysis, including causal effects and threshold estimations.

Section 5 discusses these findings and interprets their implications for the existing literature and the Chinese context. Finally,

Section 6 concludes by summarizing the core insights, outlining policy recommendations, and suggesting future research avenues.

4. Findings

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

This study serves three primary purposes. First, it offers a clear overview of the central tendency, dispersion, and range of the key variables across Chinese provinces, highlighting the significant regional disparities in digital economy development, green innovation capacity, and sustainable development performance that are central to the research question(

Table 2). Second, it enables an initial bivariate examination of the relationships posited in the conceptual framework, providing preliminary evidence of potential linkages between the Digital Economy Index, the mediating variable of green innovation, and the dependent variable of the Sustainable Development Index(

Table 3).

4.2. Baseline Regression: The Direct Impact of the Digital Economy

A baseline regression analysis is critical to reveal the essence of the relationship under scrutiny in this study: the direct effect of the (DE) on (SD). Although the correlation analysis revealed a positive bivariate relationship, it failed to control for confounding factors or to provide circumstances in which all other factors remain constant. The multivariate regression with a fixed effects model isolates the net influence of the (DEI) on the (SDI), controlling for the major factors, including economic growth, industrial structure, urbanization, and human capital.

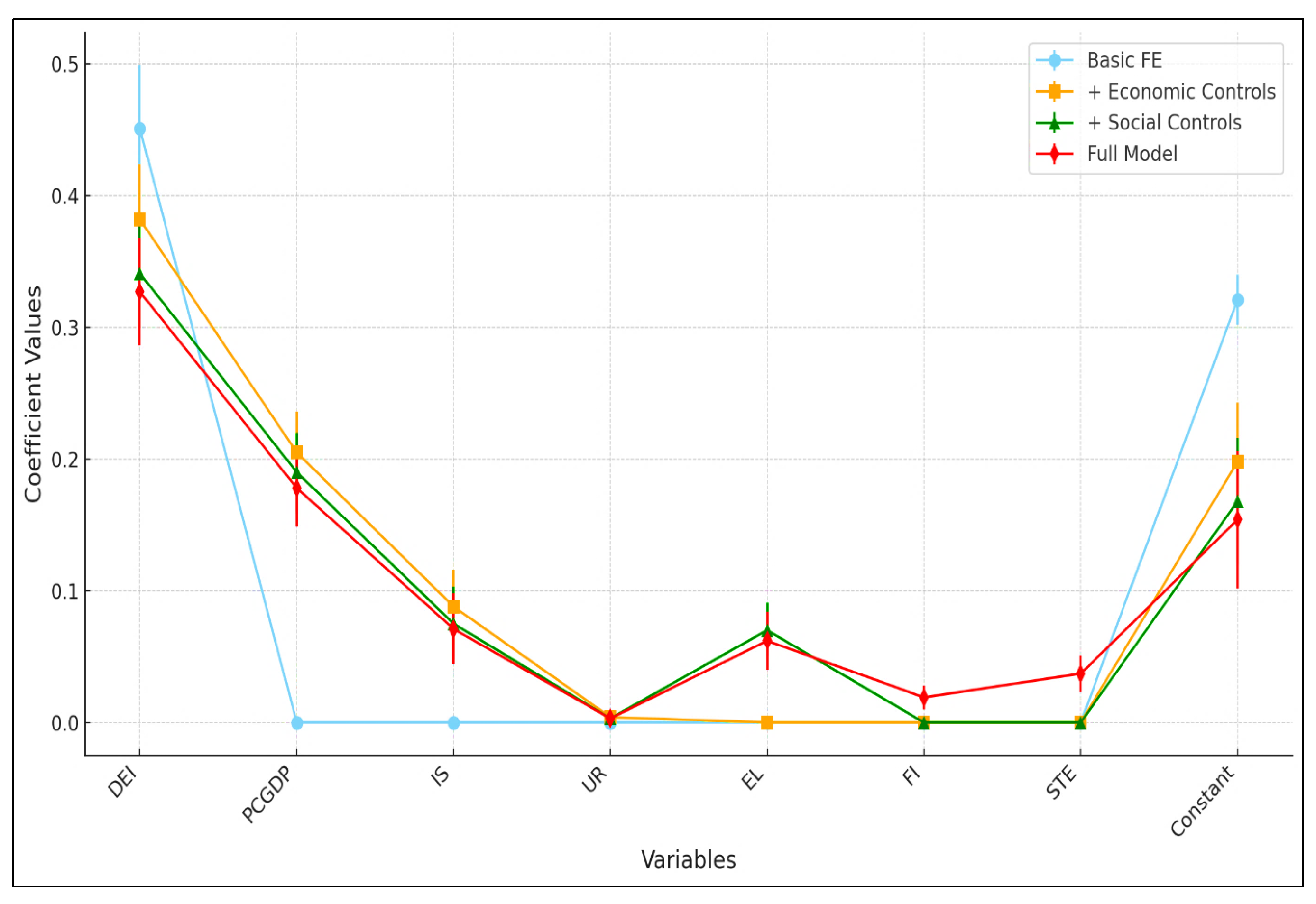

Table 4 shows that the DEI coefficient in Model 1 is 0.451 (

p < 0.01) and drops to 0.382 (

p < 0.01) and 0.327 (

p < 0.01) in Models 2 and 3, respectively, reflecting the expected attenuation of the effect with the addition of comprehensive controls, a tendency toward a constant but weaker correlation with additional variables. The per capita GDP (log), industrial structure, urbanization rate, education level, foreign investment, and scientific and technological expenditure are identified as important variables with positive coefficients, but the largest impact is from the GDP (0.205,

p < 0.01) and urbanization rate (0.004,

p < 0.01). The R2 values improve to 0.781 in Model 3, compared to 0.685 in Model 1, as additional controls are added. The coefficient of the Digital Economy Index remains 0.327 *, with a Driscoll–Kraay standard error of (0.040) **, which is virtually identical to the clustered-robust value.

The coefficients consistently show a significant positive association; it is crucial to note that these fixed effects estimates may suffer from endogeneity bias (reverse causality or omitted variables) (

Table 5).

Figure 2 displays the coefficients for key variables such as DEI, per capita GDP (PCGDP), and industrial structure (IS), among others. Each model’s coefficient values are represented by lines, while error bars indicate the standard errors for each coefficient.

To better illustrate the regression results of the baseline model with fixed effects and various control variables,

Figure 3 provides a visual summary of these findings.

Table 6 shows that multicollinearity is not a serious concern in the full regression model. Each VIF score is below the standard threshold of 10, as well as the conservative level of 5. Thus, the per capita GDP (log) has the highest VIF at 3.12, followed by the Digital Economy Index at 2.85. The other variables have VIF values between 1.42 for science and technology expenditure (%) and 2.64 for the education level. The overall mean VIF of 2.3 further confirms that the level of multicollinearity is quite acceptable, as the value is well below the critical value of 10 and close to one.

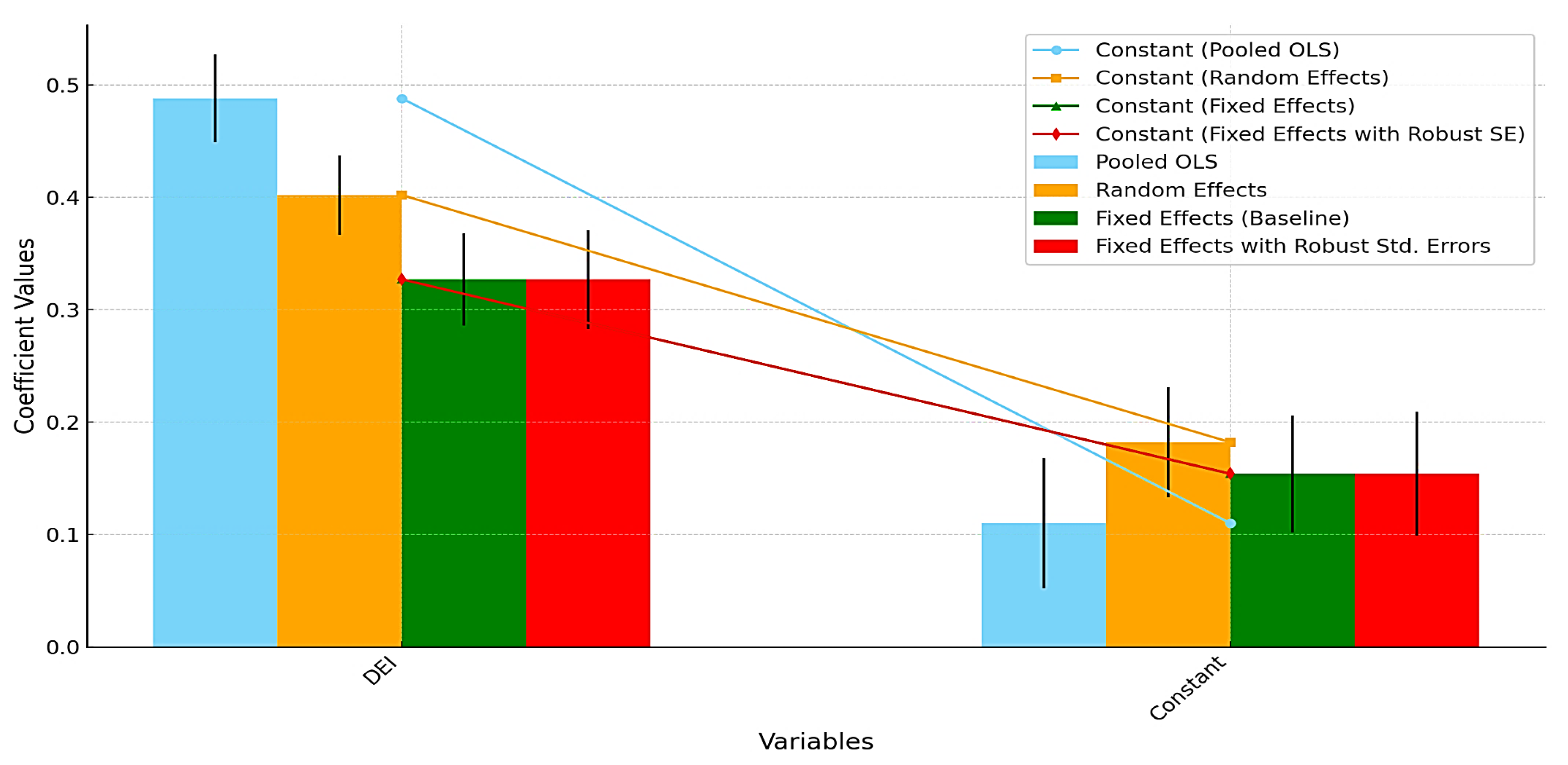

Table 7 shows positive effects across all estimation methods. The effect size decreases as the models become more rigorous. The pooled OLS has the largest effect (0.488,

p < 0.1). Random effects (0.402,

p < 0.1) and fixed effects (0.327,

p < 0.1) show smaller but significant results. The Hausman test (

p = 0.000) strongly rejects the null hypothesis and confirms that the fixed effects are the best option. The 0.327 coefficient in column (4), with robust standard errors, confirms the stability of our baseline. The fixed effects coefficient (0.327) is lower than the OLS and random effects estimates (0.488 and 0.402). This suggests the simpler models suffered from upward bias due to unobserved regional heterogeneity. Still, the FE model may face endogeneity bias, such as reverse causality, where sustainable regions attract digital investment. We treat these results as showing a robust association.

Figure 4 presents the results from several estimation methods for the Digital Economy Index (DEI) in relation to sustainable development. We include four models: pooled OLS, random effects, fixed effects (baseline), and fixed effects with robust standard errors. Bar charts display the coefficients for each model, with error bars showing the standard errors. The constants for each model are shown in line plots, allowing a clear comparison across methods.

4.3. Mediation Effect Analysis: The Role of Green Innovation

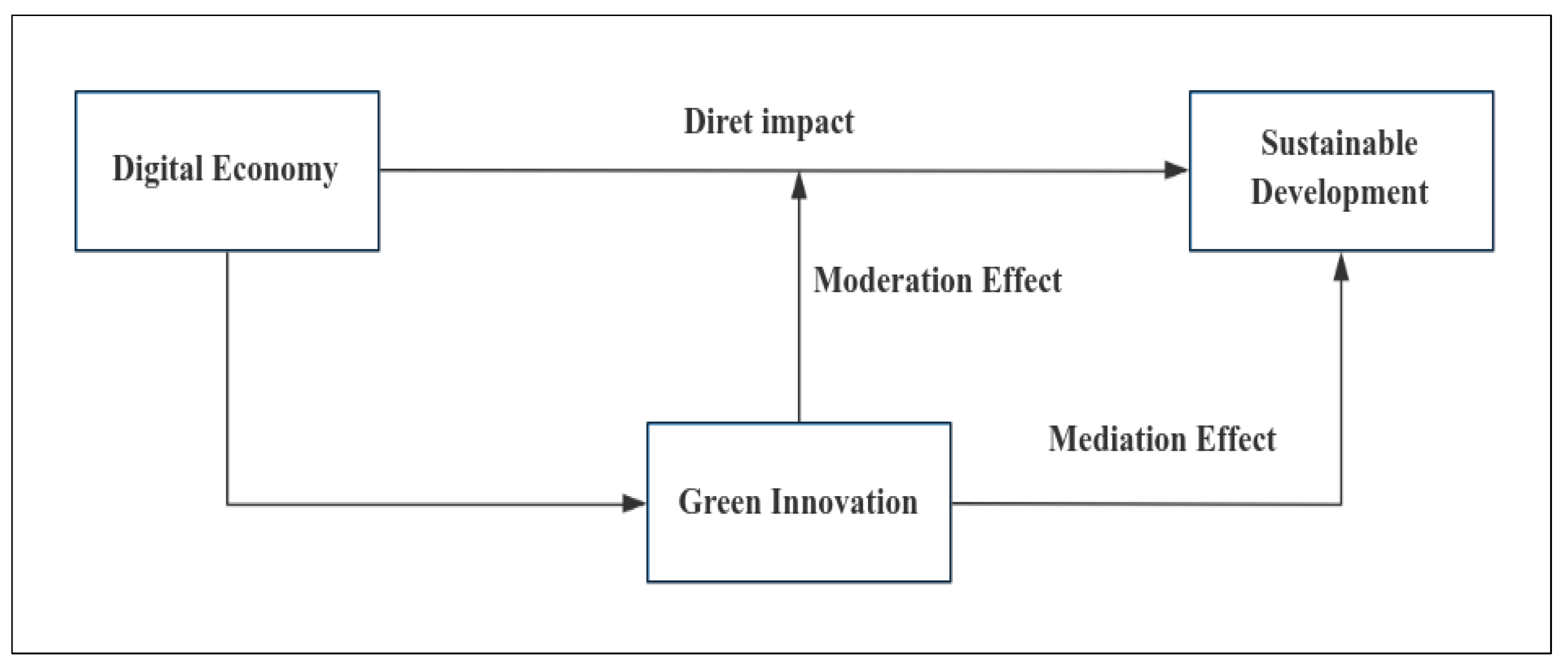

Establishing the direct impact of the digital economy on sustainable development is crucial, but it provides an incomplete picture of the underlying causal mechanisms. This section explores the core theoretical proposition of this study: that green innovation serves as a critical transmission channel, translating digital advancements into tangible sustainability outcomes. The mediation analysis moves beyond the “if” to explore the “how,” testing the hypothesis that the digital economy fosters sustainable development not only directly through efficiency gains and improved governance but also indirectly by stimulating the development and adoption of green technologies.

Table 8 shows that the DEI has a significant total effect on SD of 0.327 (

p < 0.01). Furthermore, the DE strongly predicts green innovation (GI), with a coefficient of 0.458 (

p < 0.01). When both DE and GI are included in the model, DE’s direct effect on SD reduces to 0.271 (

p < 0.01), while GI exhibits a significant positive effect on SD (0.122,

p < 0.01). These results confirm partial mediation. Specifically, the mediation effect is calculated as 0.458 × 0.122 = 0.056, representing approximately 17.1% of the total effect. Throughout all specifications, all control variables maintain the expected signs and significance.

Table 9 shows a statistically significant z-value of 5.091 for the indirect effect, and the narrow 95% confidence interval [0.034, 0.078] confirms a partial mediation pathway. Because these coefficients are obtained from the fixed effects model, they are subjected to endogeneity. The mediation effect of 17.12% shows that the overall influence of DE on SDI is mediated by green innovation. The indirect route (DE→GI→SD) is 0.056 (

p < 0.01), and the direct one is 0.271 (

p < 0.01). The digital economy has a total impact of 0.327 on sustainable development, which validates that the direct or indirect pathways are significant. The direct effect is strong and significant at 0.271 (

p < 0.001), with a total effect of 0.327, which matches the baseline estimate in

Table 7. Green innovation accounts for about 17.12% of the total effect of the digital economy on sustainable development. These results show clear evidence of partial mediation.

4.4. Threshold Effect Analysis: Identifying Nonlinearities

This subsection challenges the above assumption in order to uncover critical nonlinearities and contingent conditions. The threshold analysis moves the discussion from asking if and how the digital economy matters to understanding when and under what conditions its impact is strongest. It tests the hypothesis that the effect of digitalization is not uniform. Instead, it depends on a region’s attainment of certain developmental, regulatory, or institutional thresholds. Identifying these tipping points provides a more nuanced and actionable understanding than a single average effect.

Table 10 reveals significant nonlinear relationships between the digital economy and sustainable development, with local governance capacity emerging as the most statistically robust threshold variable. For environmental regulation intensity, the single-threshold model is statistically significant (F = 28.73,

p = 0.027), with an estimated threshold value of 0.585. In contrast, the double-threshold model fails to achieve significance (

p = 0.215). Similarly, green finance development exhibits a significant single threshold at 0.452 (F = 32.45,

p = 0.013), but no evidence of double thresholds is found (

p = 0.342). Most notably, local governance capacity demonstrates the strongest threshold effect, with a highly significant single-threshold model (F = 45.12,

p = 0.003), confirming that the impact of the digital economy on sustainable development is not linear but rather depends on the quality of regional institutions. This threshold value is estimated at 0.620, and the double-threshold specification remains insignificant (

p = 0.105).

Figure 5 analyzes the impact of the digital economy on sustainable development using both single- and double-threshold models for environmental regulation intensity, green finance, and local governance capacity. The line charts illustrate each threshold estimate, while the spline charts show the corresponding F-statistics.

Table 11 shows a threshold effect, indicating that the impact of the digital economy on sustainable development depends on the quality of local governance. In areas where the governance quality is below the threshold of 0.620 (Regime 1), the Digital Economy Index has a positive and statistically significant effect (coefficient = 0.158,

p < 0.05). When the governance quality exceeds this threshold (Regime 2), the effect becomes much stronger (coefficient = 0.419,

p < 0.01), about 165% higher (2.65 times) than in regions with lower governance quality. This difference highlights that strong institutions greatly increase the sustainability benefits of digitalization.

4.5. Subgroup Analysis: Regional Heterogeneity Between Developed and Underdeveloped Regions

To uncover potential structural disparities in the relationship between the digital economy and sustainability, we conducted a subgroup analysis. We segmented the sample into developed and underdeveloped regions based on the median per capita GDP. This analysis is critical, as it moves beyond national averages to examine whether the impact of digitalization and its transmission mechanisms is uniformly effective across different economic contexts. As a result, the findings yield more targeted and policy-relevant insights.

Table 12 reveals high structural heterogeneity in the relationship between the digital economy and sustainable development. The core finding is that the direct impact of the Digital Economy Index is substantially stronger in developed regions (0.395,

p < 0.01) than in underdeveloped regions (0.218,

p < 0.01). This suggests that the sustainability returns on digital investments are significantly amplified in economically advanced contexts. Similarly, the efficacy of green innovation as a mediating channel is more potent in developed regions (coefficient of 0.145 vs. 0.087). Furthermore, several key enablers, such as a modernized industrial structure, foreign investment, and science and technology expenditure, are involved.

Table 13 shows that the mechanisms of the digital economy’s impact also exhibit significant regional heterogeneity. The mediation effect of green innovation is both larger in magnitude and accounts for a larger proportion of the total effect in developed regions (16.5%) than in underdeveloped regions (12.8%).

This suggests that developed regions are more effective at translating digital advancements into environmentally friendly technological progress. Most strikingly, the nonlinear threshold effect based on governance capacity is only statistically significant in developed regions. These regions surpass the governance threshold by more than (140% or 2.40 times) that of the digital economy (from 0.201 to 0.482).

4.6. Robustness Checks and Endogeneity Tests

The preceding analyses establish a compelling narrative of causation. However, the potential for endogeneity bias, such as reverse causality or omitted variables, threatens the validity of any causal inference. It is plausible that more sustainable regions are better positioned to invest in and adopt digital technologies. An unobserved factor, such as regional innovation culture, may drive both digitalization and sustainability. This subsection rigorously addresses these concerns to fortify the credibility of the core findings. We employed a series of robustness checks, including alternative variable constructions and model specifications, to ensure the validity of our findings. We also used a formal instrumental variable (IV) approach to test whether the identified relationships hold under different methodological and logical assumptions.

Table 14 demonstrates the remarkable stability of our core findings across alternative model specifications and measurement approaches. When employing a principal component analysis-based alternative measure for the Digital Economy Index (correlated at 0.89 with the original), the coefficient remains highly significant at 0.301 (

p < 0.01), closely aligning with our baseline estimate of 0.327. The use of lagged independent variables to address potential reverse causality yields a consistent coefficient of 0.289 (

p < 0.01), while the system GMM estimation designed to account for dynamic panel bias produces a coefficient of 0.312 (

p < 0.01), with supporting statistics confirming instrument validity (AR (2)

p = 0.342, Hansen J

p = 0.215).

Table 15 demonstrates a statistically significant relationship between the DE and SDI. The first stage shows that our instrument (historical internet penetration) strongly predicts digital economy development (coefficient = 0.722,

p < 0.01). The second stage indicates that a one-unit increase in the DEI leads to a 0.395-unit improvement in the SDI (

p < 0.05), while controlling for green innovation and other factors. All diagnostic statistics confirm the instrument’s validity and strength.

5. Discussion

The findings of this study present a robust and nuanced empirical account of the relationship between the digital economy and sustainable development. Our analysis confirms a substantial positive direct effect. This result aligns with a growing body of international evidence [

63,

64], which posits digitalization as a general-purpose technology. It supports the theoretical proposition that digitalization fosters sustainability through enhanced resource efficiency and optimized processes. However, our finding that a supportive socio-economic context, characterized by a higher per capita GDP, an advanced industrial structure, and a skilled workforce, significantly amplifies this relationship adds a critical layer of nuance. This suggests that the benefits of the digital transition are not automatic but contingent upon pre-existing developmental advantages. That factor is sometimes underemphasized in more technologically deterministic literature.

Moving beyond the direct relationship, the mediation analysis provides critical insight into a fundamental mechanism. The significant indirect pathway via green innovation, accounting for 17.12% of the total effect, reveals that the digital economy is a potent catalyst for technological change. This finding provides strong empirical validation for theoretical models proposed by authors such as Shang et al. [

65], who argue that digital platforms are key enablers of eco-innovation. By reducing information costs and facilitating data-driven research and development, digitalization actively steers technological development in a greener direction. The relative magnitude of this mediating effect provides a quantifiable advancement over prior studies that identified the link qualitatively but lacked precise estimation of its contribution within the total causal pathway [

66], thereby solidifying the view of innovation as a central transmission mechanism.

However, there is no uniform linearity. The threshold regression analysis unveils a critical contingency, demonstrating that the potency of the digital economy is heavily dependent on the institutional environment. The identified single threshold, based on local governance capacity, reveals a significant disparity in returns on digital investments. Below a certain threshold of governance quality, the impact of the digital economy on sustainability is positive but subdued. Beyond this tipping point, however, the effect more than doubles and becomes much stronger. This suggests that advanced digital infrastructure and technologies alone are insufficient to unlock their full potential for sustainability. Their effectiveness depends on sound institutions, effective regulation, and capable public administration. These foundations steer digitalization toward societal goals, manage its disruptions, and ensure the benefits are widely distributed.

Our findings both corroborate and refine the existing body of literature on this topic. The significant positive direct effect of the digital economy aligns with the work of authors such as [

67,

68], who also identified digitalization as a key driver of resource efficiency and sustainable growth. The mediation role of green innovation provides empirical validation for the theoretical propositions. Digital technologies act as an enabling platform for eco-innovation. However, our threshold analysis, which shows the critical contingency of governance capacity, introduces a crucial nuance [

69].

The overall SDI built using the EWM weights (see

Appendix A Table A1) places strong emphasis on environmental factors. The high weights given to emissions and energy intensity indicators show that the index can capture the main regional differences in sustainable performance.

6. Conclusions

Based on the empirical analysis, this study concludes that the digital economy is a strong driver of sustainable development in China. The results demonstrate a significant positive relationship, which holds under stringent tests and various models. The research also reveals how digital progress leads to sustainability via green innovation. This demonstrates that digital and green transitions mutually support one another. Policies that boost one can help the other. However, the benefits of digitalization depend on the local institutional environment. Where the governance quality is low, the gains are limited. Once a certain level of institutional capacity is reached, the positive effects increase sharply. This research makes a key theoretical contribution by proving a dual-pathway model. First, green innovation serves as an important link, demonstrating how digital advances contribute to sustainability. This extends beyond simple correlation and supports the Porter Hypothesis, demonstrating that digitalization can stimulate green innovation. Second, determining a clear threshold effect for local governance challenges tech-only views. It demonstrates that digital benefits depend on meeting specific institutional standards, thereby supporting institutional theory.

Limitations and Future Research

This study has several limitations that suggest areas for future research. First, as the findings use regional data from China, their generalizability may be limited. Future studies could test this framework in other national or cross-country settings. Second, while robust, our measures of the digital economy and green innovation would benefit from more granular firm-level data or varied metrics. The key limitation is the inability to identify which specific institutional mechanisms drive the threshold effect of governance capacity. While governance capacity matters, the index used cannot specify elements such as regulatory quality, policy coherence, or civic engagement that unlock the digital economy’s potential. Future research should use qualitative or mixed-methods approaches to clarify which governance levers policymakers should target.