1. Introduction

Coffee is one of the most traded agricultural commodities and widely consumed beverage globally, with approximately 25 million farming households producing 80% of the world’s supply [

1]. In the Philippines, coffee consumption averages 2.5 cups daily for 8 out of 10 adults, with 9 out of 10 households keeping coffee in their pantries, indicating a shift towards heavier consumption among Filipinos [

2,

3,

4]. This growing demand is further underscored by the country’s position as the 14th largest coffee producer in the world, making a significant contribution to the global coffee industry [

5]. To enhance production, the Philippine government agencies and private organizations support the coffee industry by identifying coffee as a priority commodity, receiving funding from various national agencies under the High-Value Crops Development Act (RA 7900) to promote its production, processing, marketing, and distribution [

3].

According to the Philippine Statistics Authority [

6], coffee production (green coffee beans) totaled 15.04 thousand metric tons, generating revenues of

$2.33 billion from October to December 2023. Robusta was the most widely produced variety, contributing 11.58 thousand metric tons, or 77% of the country’s total production during this period. The Davao Region ranked as the third-largest coffee producer in the Philippines, with 2.52 thousand metric tons, representing 16.7% of the national output. Additionally, the total coffee plantation area (including all varieties of coffee) from July to December 2023 increased by 0.3% to 111.95 thousand hectares, compared to 111.65 thousand hectares in the same period the previous year [

6]. The Philippine coffee industry is predominantly composed of smallholder farmers, with 95% of farms covering less than 5 hectares [

5]. Davao Oriental Province has 5687 hectares of coffee plantations that produce an average of 1663 metric tons annually, with 4544 farmers actively engaged in coffee cultivation across the region [

7].

Coffee production, like all agricultural sectors, faces significant challenges due to the increasing frequency and intensity of extreme weather events linked to climate change [

8]. These changes threaten the livelihoods of many local coffee growers. To enhance the resilience of these farming communities, targeted interventions are necessary. However, this can only be achieved by thoroughly identifying and assessing their vulnerabilities and adaptive strategies. Additionally, as coffee is both a locally and globally traded commodity, it is crucial to understand the complex networks and activities that impact the local coffee industry. This includes examining the entire value chain—from producers to consumers—and the processes that connect them. A comprehensive value chain analysis can provide valuable insights into these interconnections and help inform effective strategies for supporting coffee growers in the face of climate change [

9].

To harness the full potential of the coffee industry, Davao Oriental has initiated programs aimed at establishing market linkages and creating a distinctive brand for Davao Oriental coffee, similar to the connection between Mt. Apo and Davao del Sur’s coffee. This study aims to comprehensively profile and assess the current production capacities and agricultural practices of smallholder coffee farmers along the buffer zone of Mt. Hamiguitan, Davao Oriental, including the women’s role in the coffee value chain. Additionally, it seeks to identify and evaluate the farmers’ awareness of and adaptation strategies for climate change. A comprehensive assessment of smallholder coffee farmers’ current production capacities—including the various factors influencing production and marketing—is crucial for targeting the right types of technical assistance and market access. Moreover, this profiling will serve as a foundational reference for crafting tailored recommendations and strategies to develop and strengthen the coffee industry in Davao Oriental, enabling it to compete effectively in the local and later in the global market.

This study is significant for several reasons, as it addresses various research gaps and contributes valuable insights to the fields of sustainable agriculture, gender studies, and climate change adaptation. By adopting an interdisciplinary perspective that integrates social, economic, and environmental factors, the research provides a holistic view of sustainability in small-scale coffee farming, effectively bridging gaps between different fields of study. One key contribution of the study is its documentation of sustainable production practices employed by small-scale coffee farmers. This enriches the knowledge base of effective methods that promote environmental sustainability while supporting livelihoods. Additionally, the research assesses the role of farmer-based organizations in promoting sustainable practices, thereby addressing the gaps related to participatory approaches in agricultural research and implementation. The study also examines the economic viability of sustainable farming and its impact on the livelihoods of farming families, particularly women. By exploring the specific roles of women in coffee farming, it sheds light on their contributions, which are often overlooked in traditional agricultural research. This focus helps fill critical gaps in understanding gender dynamics within the context of sustainability. Furthermore, by investigating how small-scale coffee farmers adapt their practices to climate change, the study enhances our understanding of local knowledge and resilience strategies. This addresses a significant gap in the region-specific adaptation practices that are frequently underrepresented in broader climate change literature. Finally, the research provides insights into the challenges and practices of small-scale coffee farmers, particularly women, in the context of sustainability. While the study identifies key areas where support is needed, including the adoption of sustainable practices, it does not fully explore policy implications in depth. However, the findings can inform future initiatives aimed at addressing these gaps and promoting sustainability in the coffee sector, particularly for smallholder farmers in the province.

This study contributes to the existing literature by exploring the intersection of gender, climate resilience, and sustainable farming in small-scale coffee production. It highlights the critical role of women across the coffee value chain, from planting and processing to marketing, and their significant contributions to climate adaptation strategies. By focusing on gender-responsive strategies, the study emphasizes the need for targeted interventions that empower women with training and resources to enhance both climate resilience and sustainability. In doing so, it bridges the gap between gender studies, climate change adaptation, and sustainable agriculture, offering valuable insights into how inclusive practices can strengthen the resilience of smallholder coffee farming in the Philippines.

2. Materials and Methods

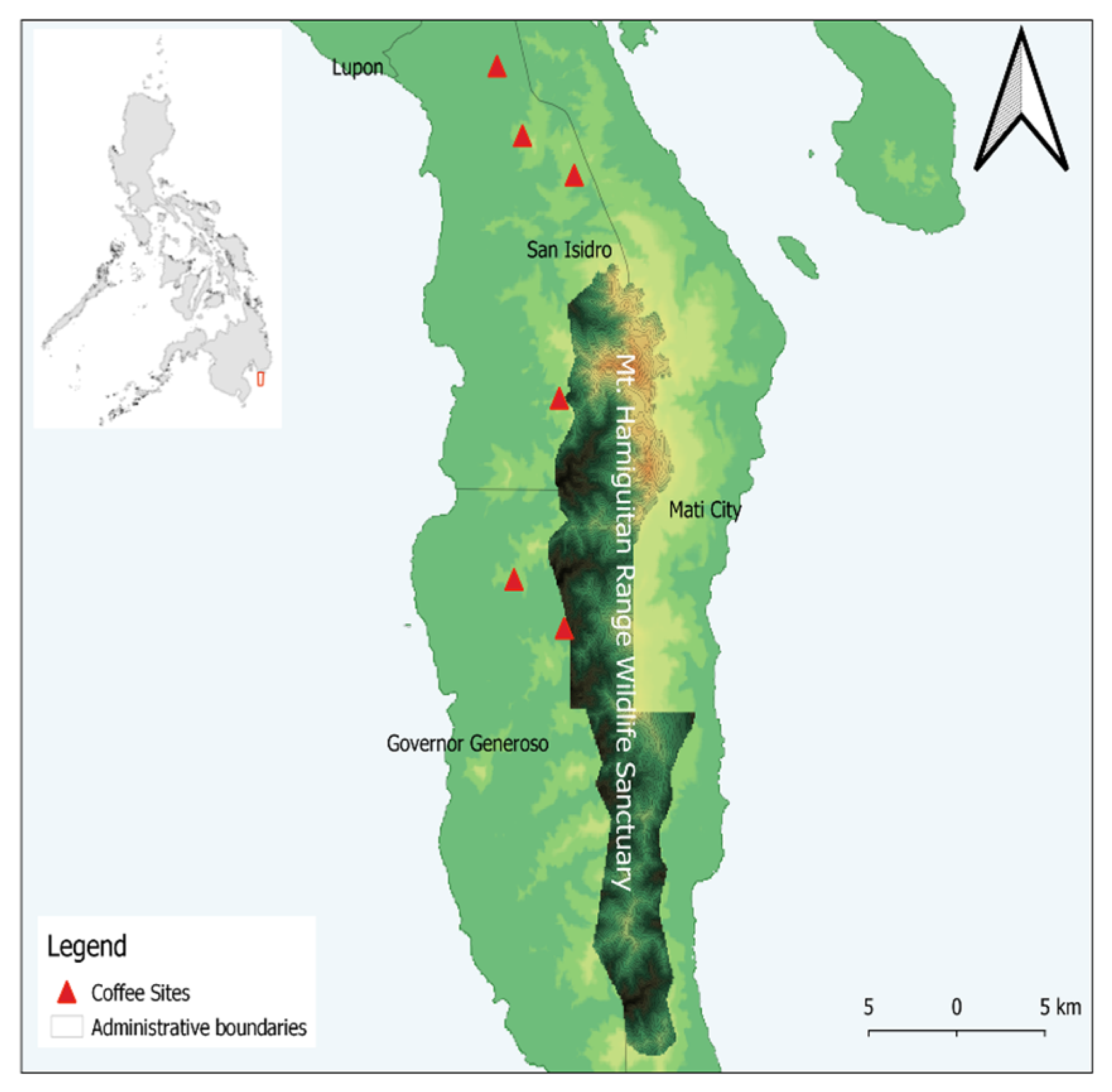

Mt. Hamiguitan spans two municipalities and one city: San Isidro, Governor Generoso, and the City of Mati in Davao Oriental. It encompasses a total area of 16,923 hectares, including a designated buffer zone of 9279 hectares. This study was conducted in two coffee-producing areas within the buffer zone: San Isidro and Governor Generoso. Specifically, the research focused on the barangays of Sto. Rosario and San Miguel in San Isidro, as well as Oregon and Upper Tibanban in Governor Generoso.

One-on-one personal interviews with 57 coffee farmer respondents were conducted using a validated semi-structured questionnaire. This questionnaire included a mix of closed and open-ended questions to facilitate comprehensive data collection during the field survey. Farmers were encouraged to discuss their farms, voice their concerns about production challenges, and share their farming strategies. The questionnaire covered various topics, including the farmers’ demographic characteristics, farm profiles, cultural practices, production status, constraints, the extent of their engagement in the coffee value chain, women’s role in the coffee production, and their climate change awareness and adaptation strategies. A purposive sampling design was employed to select study respondents based on the following criteria: (1) At least 1 hectare of cultivated land planted with coffee, with coffee as an intercrop; (2) A minimum of 300 standing coffee trees, which aligns with the local definition of smallholder farms; and (3) A minimum of four years of coffee farming experience. The threshold of 300 coffee trees was chosen based on regional agricultural standards, which categorize farms with this number of trees as smallholder operations. Additionally, a density of 1050 coffee trees per hectare is typical for smallholder farms in the region, balancing optimal spacing for growth and productivity while remaining manageable for small-scale farmers. The selection of farmers was made with guidance from local government units, particularly the municipal agriculture offices (MAOs) of San Isidro and Governor Generoso, ensuring a representative sample from each municipality. The distribution of respondents across the four barangays was not evenly split, with a larger concentration of farmers in certain areas due to the varying scale of coffee production in each area.

Geotagging was employed to obtain the geographical coordinates of coffee plantation areas. These data points were then imported into ArcGIS software (ArcMap 10.3) to create a map visualizing coffee distribution across the selected study sites. The collected data were analyzed using thematic analysis and descriptive statistics.

All respondents provided informed consent for their participation in the research, which was conducted with strict adherence to ethical standards. Participation was both anonymous and voluntary, allowing respondents to withdraw from the study at any time without repercussions. The selection of respondents adhered to the previously mentioned criteria, and only the researcher had access to the research data. The study followed the guidelines outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki regarding research involving human participants, ensuring the integrity and ethical conduct of the research process.

3. Results

3.1. GIS Mapping of Coffee Plantations

Figure 1 presents the GIS mapping of coffee plantation areas located within the buffer zones of Mt. Hamiguitan, marked as red triangles. This map illustrates the spatial distribution of coffee farms in the area, highlighting how they are situated within the varied landscape, which includes differences in elevation, proximity to water sources, and other environmental factors. Proximity to water is critical for coffee crops as it helps maintain consistent soil moisture levels, vital for healthy plant growth, especially during dry spells. Coffee trees are sensitive to water stress, and insufficient moisture can lead to poor growth, reduced flowering, and lower yields. Conversely, excessive water can cause root diseases, making reliable water access essential for optimal coffee production.

In terms of the geographical characteristics of the study areas, the coffee plantations are distributed across both lowland and mid-elevation zones. The elevation ranges from approximately 100 to 800 m above sea level, with the majority of coffee farms located between 200 and 600 m. These areas are characterized by a tropical climate, with distinct wet and dry seasons that influence coffee production.

To further address the concerns of climate change, actual climate data from local weather stations for San Isidro and Governor Generoso were gathered. The temperature data show an average annual temperature of 26–28 °C, while rainfall patterns indicate an average of 2500 to 3000 mm of annual precipitation, concentrated from May to November. These climatic conditions are generally suitable for coffee cultivation, although fluctuations in rainfall and temperature variability could pose future risks to crop productivity. This agroclimatic characterization provides a clearer picture of the climatic and geographical suitability for coffee production. It also highlights the need for targeted adaptation strategies to address potential climate change impacts, ensuring the long-term sustainability of coffee farming in the region.

3.2. Coffee Farmers’ Profile

A summary of the coffee farmers’ profile is shown in

Table 1. Among the 57 coffee farmers interviewed, there were 28 females and 29 males. In terms of educational attainment, 49% of the farmers had completed the elementary level, 44% had completed the high school level, while only 7% had completed the college level. The interviews further revealed that the majority of farmers in the study area were older, with 42% aged over 60 years. Additionally, 28% fell within the 51–60 age range. Only 21.2% were between 41 and 50 years old, while a small minority (8.8%) were aged 40 and below. This age distribution underscores the need for strategies to attract younger individuals to farming in the study area. Most of the farmers interviewed (50.8%) had over 40 years of experience in coffee farming. Additionally, 17.5% possessed 31 to 39 years of experience, while 26.3% had between 21 and 30 years of experience. A small percentage (5.4%) had 20 years or less of coffee farming experience. This distribution highlights the extensive knowledge and expertise present among the majority of farmers in the study area. In terms of farm ownership, 96% of the 57 coffee farmers surveyed were farm owners, while 4% were tenants. Among the male participants, 97% owned their farms, and 3% were tenants. Similarly, 96% of female participants were farm owners, with 4% being tenants.

The majority of farmers (68.4%) had households with 1 to 3 members, while 21% had 4 to 6 members, and only 10.6% had more than 6 members. This distribution indicates that most farming households in the study area are relatively small. As a result, many farmers hire laborers to assist with labor-intensive tasks, such as clearing, weeding, and harvesting. This reliance on hired labor is particularly important for tasks that require additional hands during peak seasons, such as the harvest period. However, processes like drying and selling are typically managed by family members. The cost of hiring labor can be significant, especially during harvest time, when additional workers are needed. The expense of labor varies depending on the task and the prevailing wage rates, which can fluctuate based on the local demand and availability of workers. While hiring labor allows farmers to maintain productivity, it can also increase production costs, which may impact the overall profitability, particularly for smaller-scale farmers with limited financial resources.

3.3. Coffee Farmers’ Affiliation and Access to Information

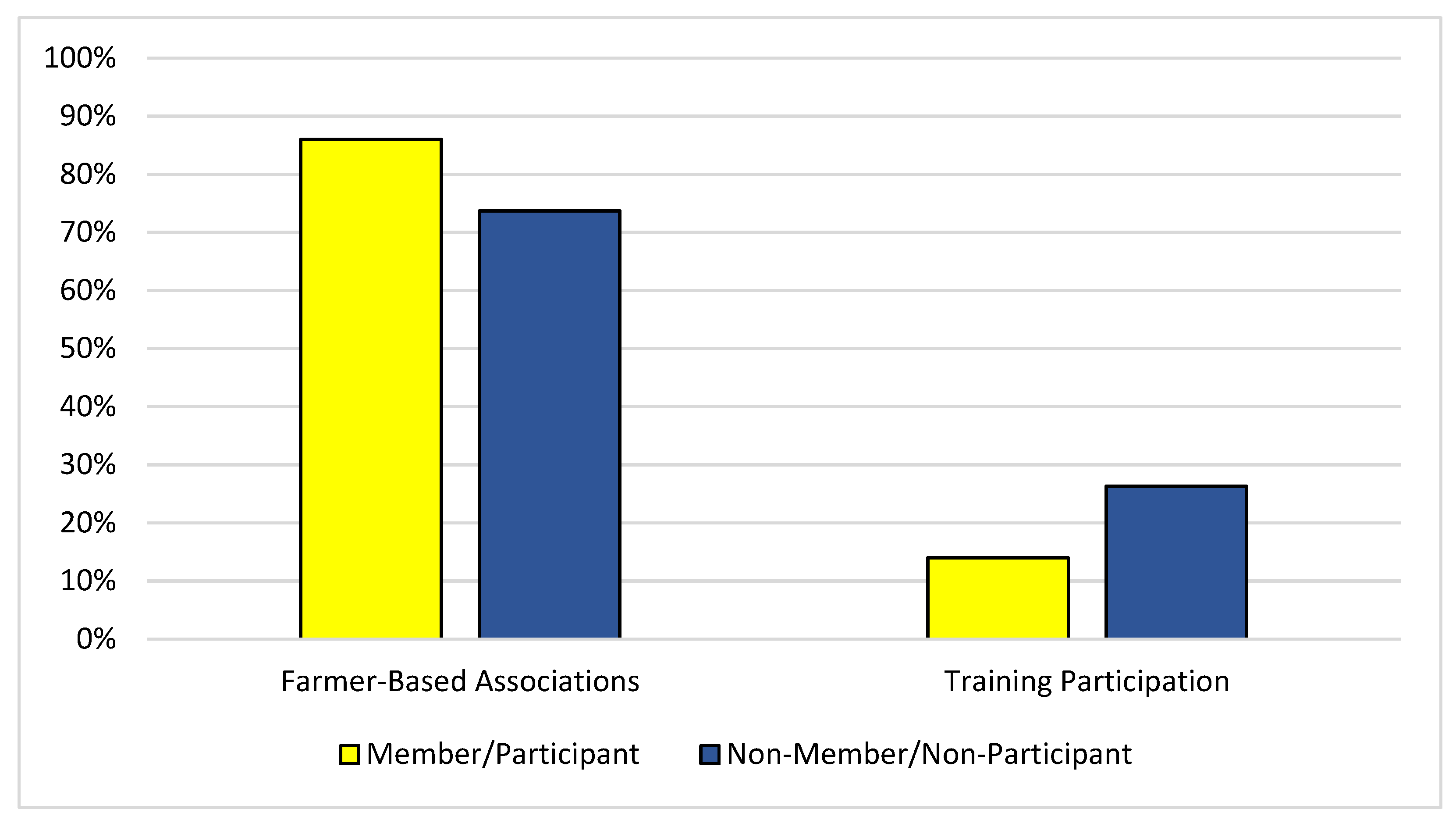

Regarding membership in farmer-based associations, only 26.3% of the farmers were members, while 73.7% were not (

Figure 2). A closer analysis revealed that farmers aged 51 and above were less likely to be members of these associations compared to those aged 40 and below. However, no significant gender-based differences were observed in association membership, with both male and female farmers showing similar participation trends. In terms of training participation, only 14% of the farmers had attended training programs related to sustainable coffee farming, while 86% had not (

Figure 2). There was no significant difference in training attendance between male and female farmers. However, older farmers (aged over 60) were less likely to have participated in training programs compared to younger farmers

3.4. Farmers’ Coffee Production Practices

As Davao Oriental remains one of the country’s leading coconut producers, adopting a diversified cropping system by intercropping cash crops, like coffee, beneath coconut trees can significantly enhance farmers’ incomes. This strategy had been implemented by 97% of the respondents interviewed, while only 3.5% practiced coffee monoculture, as shown in

Figure 3. Additionally, among the farmers interviewed, 62% were aware of the Robusta coffee variety, while the remaining 38% referred to their coffee as “native”.

In addition to coconut, farmers also intercrop coffee with other crops such as banana, vegetables (e.g., tomatoes and peppers), and root crops (e.g., cassava and sweet potato). These alternative crops were chosen for their quick turnover and profitability, providing more immediate cash flow compared to coffee. When asked about the profitability of coffee, farmers reported that coconut and banana were more profitable than coffee. These crops were perceived as more stable and less labor-intensive, requiring fewer resources and maintenance. In contrast, coffee farming was viewed as more labor-intensive, with challenges such as aging trees, declining yields, and pest issues. As a result, coffee did not generate significant income for many farmers, which may explain the limited interest in attending specialized training or improving coffee management practices. Regarding technical knowledge, farmers generally had more experience in managing coconut and banana than in coffee. These crops require less intensive management, and farmers have developed stronger technical expertise in their cultivation over time. In contrast, coffee farming faced challenges such as pests, diseases, and fluctuating market prices, contributing to its lower priority in farmers’ production systems.

Most coffee farms were established in the 1980s, accounting for 35.7% of the total, followed closely by 31% that were established in the 1970s. In the 1990s, 17.5% of the farms were established, while fewer were founded in the 2000s (8.8%) and in 2010 (7%). This distribution reflects a significant concentration of coffee farming activities during the late 20th century.

As shown in

Figure 4, nearly all farmers engaged in clearing (82%) and pruning (93.7%) their coffee trees, with pruning typically occurring once or twice a year. However, only a small percentage of farmers applied fertilizers (15%) and chemical pesticides (12%), and these practices were often conducted concurrently with coconut farming activities. The low application of fertilizers and pesticides in coffee cultivation suggests that coffee management was not a priority for most farmers. This limited application may also be attributed to the lack of sufficient technical training or resources available to the farmers to improve their coffee management practices.

Most farmers intercropped an average of 500 (35.2%) to 600 (31.5%) coffee trees per hectare, as illustrated in

Figure 5. Some farms had planted 750 trees (15.8%) and 860 trees (10.5%) per hectare. Many of these farms were established in the 1970s and 1980s, and the farm owners have struggled to replace or rehabilitate unproductive or damaged trees. In contrast, the coffee plants established in the last 25 years show a higher density, averaging 1050 trees per hectare (7%).

Farmers were asked to report their annual yield per sack of harvested fresh beans, with each sack containing five “taro” and weighing 50 kg. Each taro yields approximately 3 kg of milled coffee beans. To determine the average yield per tree, the total weight of the harvested beans in kilograms was divided by the number of planted trees. Almost half of the respondents (43.8%) reported an average yield of only 0.2 kg of beans per tree, while 22.8% had an average of 0.3 kg per tree. These lower yields are primarily attributed to coffee trees that are over 40 years old and lack consistent cultural management practices. Only 35% of respondents achieved an average yield of 0.75 to 0.80 kg of beans per tree.

3.5. Role of Women in Coffee Production

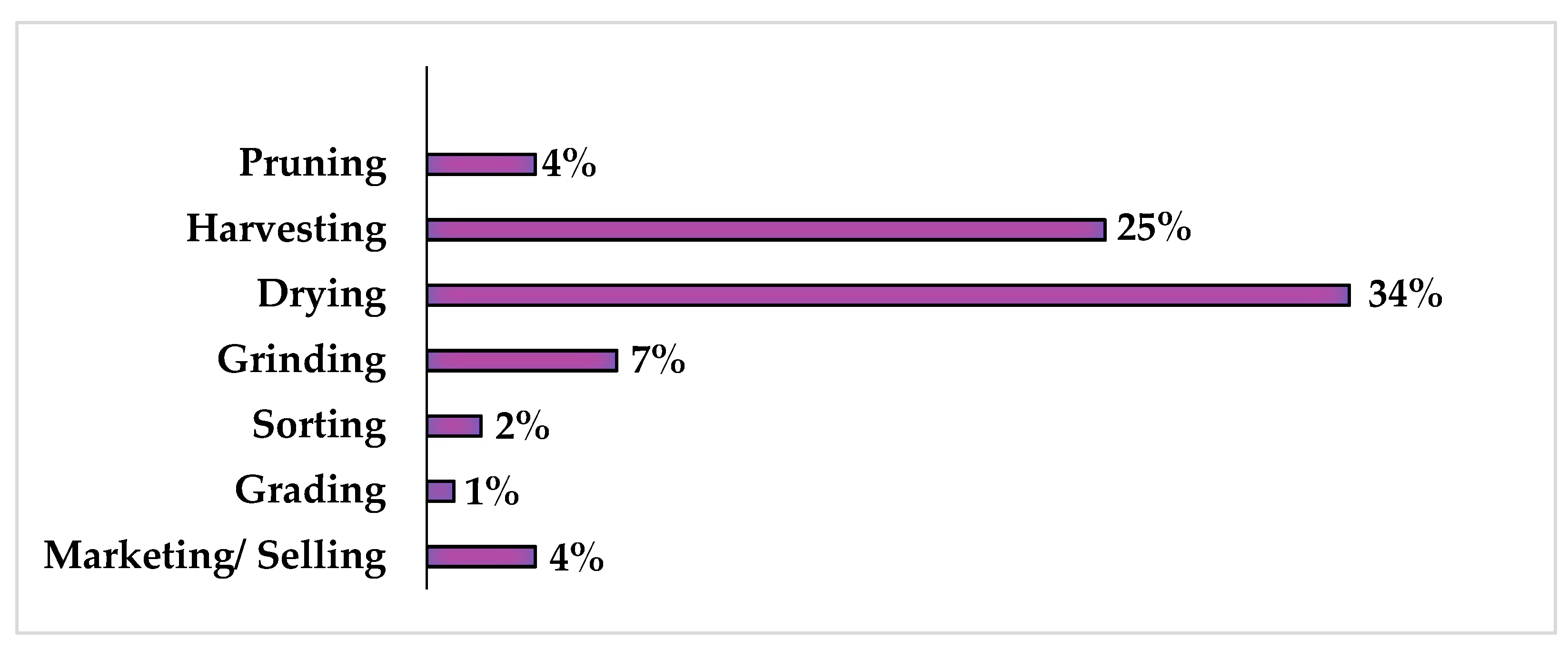

The demographic breakdown of the 57 coffee farmers interviewed reveals a nearly even distribution between genders, with 28 females and 29 males. This balance may reflect broader trends in agricultural communities where both men and women play significant roles in farming activities. As shown in

Figure 6, women play a significant role in coffee production, with the majority involved in drying (34%) and harvesting (25%). Additionally, some women participate in grinding (7%), pruning (4%), marketing or selling (4%), sorting (2%), and grading (1%). This diverse involvement highlights the essential contributions of women in the coffee industry.

3.6. Challenges Reported by Coffee Farmers

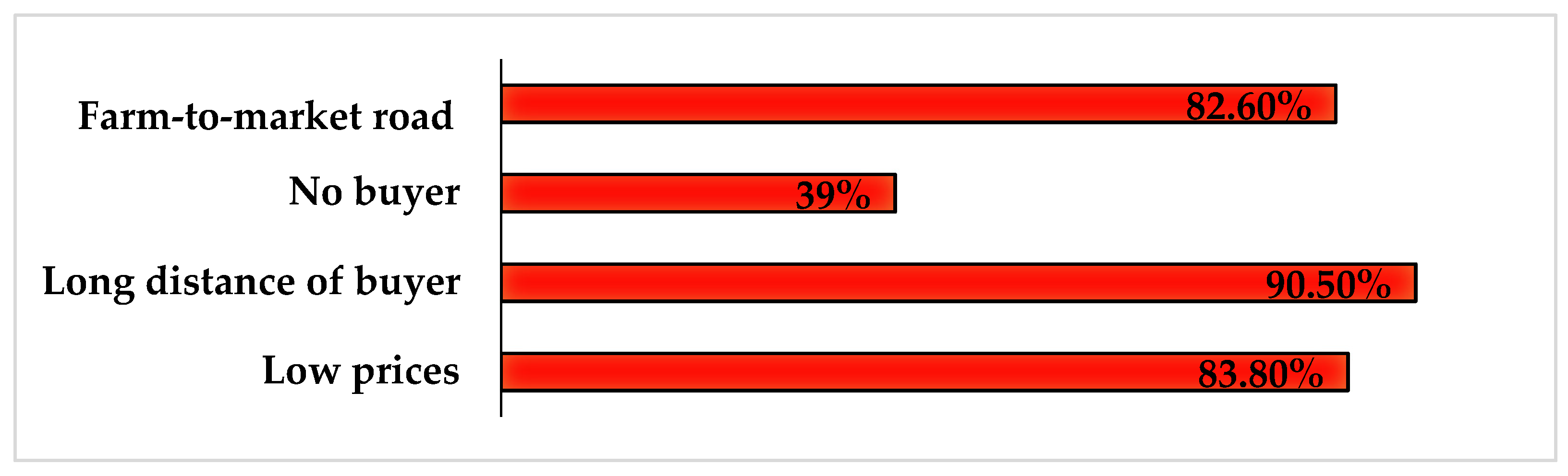

As illustrated in

Figure 7, nearly all farmers (90.5%) faced challenges due to the long distance to buyers for their coffee. Additionally, 82.6% to 83.8% encountered difficulties related to farm-to-market roads and low prices. Furthermore, 39% of farmers reported having no buyers for their coffee.

3.7. Climate Change Awareness and Adaptation Strategies

All respondents recognized that weather patterns are changing, attributing this to climate change, plastic burning, and natural factors. Everyone had heard the term “climate change”, which they defined as sudden shifts in weather, increased temperatures, and prolonged periods of heat followed by rain. This issue is critical for the respondents. To adapt, they intercropped coffee with various crops, including banana, coconut, ipil-ipil, durian, lanzones, rambutan, mangosteen, cacao, cassava, sweet potato, mango, squash, beans, and other vegetables. Some farmers expressed concerns that these additional crops might impact coffee growth and fruiting. Adaptation strategies to mitigate climate change effects included pruning, providing shade with ipil-ipil trees, and using nets.

The impact of climate change on coffee production has been observed in the form of late flowering, reduced yields, crop failures, and an increase in pests and diseases. Farmers identified several symptoms affecting their crops, including wilting leaves, hollow beans, and the dropping of leaves and flowers. Pests, particularly the coffee borer beetle—referred to locally by farmers as “bokbok”—were frequently identified as major constraints to coffee production. Additionally, some farmers noted signs of nutritional deficiencies, particularly in soil quality, which they believed contributed to reduced plant vigor and lower yields.

Despite recognizing these issues, many farmers reported that they do not actively manage them. The primary reasons cited included a lack of access to resources, such as pesticides or fertilizers, limited knowledge on effective pest and disease management techniques, and the high costs associated with implementing management strategies. Moreover, many farmers stated that they rely on traditional practices, which are often insufficient to address the emerging challenges posed by climate change. This highlights the need for more targeted support, training, and resources to help farmers effectively manage pests, diseases, and nutritional deficiencies in the context of a changing climate. Ultimately, climate change negatively affects livelihoods and the coffee industry by lowering both yield and income.

4. Discussion

4.1. GIS Mapping of Coffee Plantations

The mapping of coffee farms provides important insights into the spatial distribution of plantations and their relationship to key environmental factors. It highlights the potential for collaboration among farmers by identifying geographical connections that could facilitate resource sharing and coordinated efforts. Collaborative activities, such as the joint use of equipment, access to shared water sources, and exchanging knowledge on pest and disease management, could enhance both productivity and sustainability. Additionally, farmers could collaborate on training programs and workshops to improve technical skills in sustainable farming practices, climate adaptation, and pest control. By pooling resources and expertise, farmers can better address the challenges posed by climate change, pests, and market fluctuations, fostering long-term resilience and sustainability for the coffee sector in the province.

The spatial analysis of the farms reveals important environmental factors influencing coffee production, including elevation, temperature, humidity, and sunlight. Higher elevations typically offer cooler temperatures that improve coffee quality, while lower elevations support faster growth [

10,

11]. Proximity to water sources is another critical factor, as farms near rivers or streams benefit from natural irrigation and consistent moisture, which are essential for healthy plant growth and yield optimization [

12]. Coffee trees, being sensitive to water stress, require balanced moisture levels to avoid poor growth, reduced flowering, and yield loss as well as root diseases caused by excessive water.

In Davao Oriental, coffee cultivation typically does not require irrigation throughout the year, owing to the province’s tropical climate, characterized by distinct wet and dry seasons. The annual rainfall, averaging 2500–3000 mm, typically provides adequate moisture for coffee cultivation. However, during the dry season or periods of prolonged rainfall variability, coffee plants may face water stress, impacting their growth and productivity. While many farms rely on natural water sources, such as rivers and streams, the absence of organized irrigation infrastructure can create challenges, as access to these resources may be inconsistent. The lack of reliable water management systems in some areas highlights the need for improved irrigation solutions. Implementing localized irrigation systems, such as rainwater harvesting or other sustainable water management practices, could help buffer the effects of dry spells, ensuring a more stable water supply during critical periods. Developing such infrastructure would not only improve water access but also enhance the resilience and stability of coffee production, allowing farmers to better adapt to fluctuating climatic conditions.

The coffee farms are located within lowland and mid-elevation zones, ranging from 100 to 800 m above sea level, with the majority situated between 200 and 600 m. These areas experience a tropical climate with distinct wet and dry seasons, which generally favors coffee cultivation. Local climate data indicate an average annual temperature of 26–28 °C and annual rainfall of 2500–3000 mm, with most precipitation concentrated from May to November. Although these conditions are suitable for coffee, the variability in rainfall and temperature fluctuations, combined with potential climate change impacts, pose future risks to coffee farming.

The inclusion of agroclimatic data, alongside the geographical mapping, provides a more comprehensive understanding of the region’s suitability for coffee production. This analysis reveals the importance of developing and implementing adaptation strategies to mitigate risks such as temperature variability and erratic rainfall. By addressing these challenges, coffee farmers can better safeguard the sustainability of their crops in the face of climate change, ensuring the long-term viability of coffee farming in the region.

4.2. Coffee Farmers’ Profile

This study reveals an aging farmer population, with many respondents reflecting the average age of Filipino farmers, which is between 57 and 59 years [

13]. Most of the farmers were educated till elementary and high school levels, and very few reached college level. This demographic trend raises concerns about future agricultural productivity and innovation. The small percentage of younger farmers who have higher educational attainment indicates a critical gap in the labor force, posing challenges for the sustainability of coffee farming and the broader agricultural sector. Younger individuals often bring fresh perspectives and a willingness to adopt new technologies, essential for adapting to changing conditions [

14]. To address this issue, strategies to attract and retain younger farmers are vital. Educational opportunities, training programs in modern agricultural techniques, and financial literacy can incentivize youth engagement. Community mentorship programs connecting experienced farmers with younger generations can facilitate knowledge transfer and spark interest in agriculture.

Years of farming experience significantly contribute to agricultural knowledge, typically gained through hands-on work and informal peer exchanges. Research suggests that more experienced farmers are likelier to embrace innovative practices [

15]. The interviews reveal that most farmers have over 40 years of coffee farming experience, providing them with valuable insights into local growing conditions and climate variations. In addition, 17.5% have 31 to 39 years of experience, and 26.3% have 21 to 30 years, indicating a wealth of knowledge among respondents. However, only 5.4% possess 20 years or less of experience, highlighting potential knowledge gaps in future generations. To bridge this gap, mentorship initiatives could connect seasoned farmers with less experienced ones, facilitating the sharing of best practices while integrating modern techniques. Workshops led by experienced farmers could further instill valuable skills in younger farmers, fostering community and continuity in coffee farming. By leveraging the strengths of seasoned practitioners while preparing for future challenges, the agricultural sector can ensure that essential expertise is preserved as older farmers retire.

Household size is often used as a proxy for labor availability, with larger families typically benefiting the farming operations [

16,

17,

18]. More than half of the respondents reported having 1–3 members in their households. With fewer family members, many farmers hired laborers for tasks such as clearing, weeding, and harvesting, while production processes like drying and selling were primarily handled by family members. This distribution indicates that larger families tend to provide a greater labor force, facilitating timely farming operations and alleviating the financial burden of hiring external labor [

19,

20]. The results further suggest that most farming households are small, impacting both family dynamics and farming efficiency. Smaller households may streamline labor roles, but they can also place a heavier burden on the available members, especially for physically demanding work. This prevalence of small households may reflect broader social trends, such as younger generations migrating to urban areas, which could further reduce the available labor for farming. Additionally, smaller households may face economic challenges, limiting their resources for agricultural investments or adaptations to climate change. To address these challenges, exploring cooperative models that allow nearby small households to share labor, resources, and marketing efforts could enhance community ties and productivity. Furthermore, providing access to training programs on efficient farming practices could empower these households to optimize their outputs.

4.3. Coffee Farmers’ Affiliation and Access to Information

In the Philippines, extension services and development support are channeled to farmer’s associations, underscoring the crucial role these organizations play in providing opportunities for farmers to participate in information dissemination and technology promotion from service providers, such as the Department of Agriculture. Only 26.3% of the coffee farmers belong to farmer-based associations, leaving 73.7% unaffiliated. This gap raises concerns about access to resources, support, and collective bargaining power. Membership enhances the adoption of agricultural technologies and facilitates knowledge sharing, which is crucial for productivity and adaptability, especially amid climate change. It serves as a powerful tool to bridge information asymmetry and reduce the cost of seeking new technology information [

21]. Farmers who have successfully utilized a particular technology often share their personal experiences with other farmers. In some cases, knowledgeable farmer households acquire information through peer farmers (family, friends, neighbors) who are mostly members of the same associations, with a small percentage getting information from agricultural extension workers [

22]. Associations also advocate for better prices and infrastructure, but the lack of participation limits farmers’ representation in decisions impacting their livelihoods.

The survey conducted revealed that the number of farmers not participating in organizations outweighed the distribution of active members. Factors contributing to low participation include a lack of awareness, feelings of isolation, and logistical challenges [

23,

24,

25]. To address this, targeted outreach is essential. Workshops and success stories can demonstrate the benefits of joining, while incentives like subsidized training may encourage membership. Increasing participation can improve access to resources, enhance policy representation, and bolster the resilience of coffee farmers, supporting industry sustainability. Training also boosts farmers’ learning and adoption rates [

26]. Notably, 86% of new coffee farmers expressed a need for more training, highlighting a gap in awareness about the available resources, which affects their ability to manage coffee diseases and implement effective practices.

Coffee pests, particularly the coffee borer beetle (CBB), locally known as “bokbok”, are a significant concern for farmers in the study area. CBB is a major pest that burrows into coffee cherries, causing them to deteriorate before harvest, leading to reduced yields and lower-quality beans. Despite the widespread recognition of the pest’s impact, control measures are often limited to basic practices, such as manual removal, pruning, and maintaining farm hygiene. While these methods provide some relief, they are insufficient to fully address the pest problem. More effective pest management strategies, such as the use of chemical pesticides or biological control agents, are not widely adopted due to barriers including the high cost, limited availability, and concerns about environmental impact. Furthermore, many farmers lack the necessary training or technical support to implement integrated pest management (IPM) strategies effectively.

4.4. Farmers’ Coffee Production Practices

The results indicate a strong trend toward diversified cropping systems among coffee farmers in Davao Oriental, with 97% intercropping coffee with coconut trees. This practice maximizes land use and boosts farmers’ incomes by diversifying products, helping mitigate risks from market fluctuations and crop failures [

27,

28,

29,

30]. Intercropping also promotes year-round income and enhances soil health, pest resistance, and resilience to climate change. Conversely, only 3.5% of farmers practice coffee monoculture, raising concerns about vulnerabilities such as pest susceptibility and soil depletion [

31]. Intercropping can enhance pest resistance by promoting biodiversity and creating natural pest control mechanisms [

32]. By growing multiple crops alongside coffee, farmers can reduce the likelihood of pest outbreaks, as pests are often less attracted to diverse plantings than to monocultures. Additionally, certain intercropped plants may serve as repellents or attract beneficial insects that help control pest populations, leading to lower pest damage overall. This contrasts with coffee monoculture, where a lack of plant diversity can make crops more vulnerable to pests and diseases. Consequently, intercropping not only helps reduce pest pressure but also contributes to soil health and overall ecosystem stability, offering a more resilient approach to coffee farming [

32].

The majority’s proactive approach suggests a commitment to sustainable practices. Additionally, 62% of farmers are aware of the Robusta coffee variety, known for its hardiness, while 38% refer to their coffee as “native”, indicating reliance on less optimized traditional varieties. The “native” or traditional varieties typically include local Arabica cultivars that have adapted to the province’s specific agroecological conditions. While these traditional varieties are less optimized for high yields compared to more commercially developed cultivars like Robusta, they are valued for their resilience to local pests and the region’s variable climate. This presents an opportunity for education on the benefits of cultivating Robusta for improved yields and marketability. However, coffee farmers must also explore other coffee varieties that may be more suitable in their farms to promote sustainability [

33].

Over 65% of coffee plantations were established over 40 years ago, indicating that many trees have reached peak productivity and require rehabilitation [

34]. Most farms were established in the 1970s and 1980s, reflecting a surge in coffee as a cash crop driven by favorable market conditions. However, the decline in new farm establishments since the 1990s raises concerns about sustainability and the future of coffee farming, particularly as older farmers retire. Attracting younger generations to coffee farming is essential for reinvigorating the industry with modern practices.

The high percentages of farmers engaged in clearing (82%) and pruning (93.7%) reflect their commitment to maintaining healthy coffee trees, which is crucial for maximizing yield [

35,

36,

37]. However, the low use of fertilizers (15%) and pesticides (12%) raises concerns about crop health and productivity. This limited fertilizer use suggests a reliance on natural soil fertility, which could lead to nutrient deficiencies if not properly managed [

38,

39,

40]. Given the widespread practice of intercropping, farmers may believe that coffee benefits from the fertilization of associated crops, as the diverse plant cover can enhance soil fertility through organic matter and nutrient cycling. Alternatively, it is also possible that farmers are applying little to no fertilizer to any crops, instead relying on natural soil fertility and organic inputs, such as crop residues, compost, or manure. This limited use of fertilizers could be indicative of a preference for low-cost, low-input farming practices. While this approach may work in the short term, it raises concerns about the long-term sustainability of coffee production, as nutrient deficiencies may develop over time, especially in areas with high crop demand or poor soil quality. Without adequate fertilization, soil health could deteriorate, impacting coffee yields and overall productivity. The reliance on natural soil fertility and intercropping as a strategy to maintain soil health requires careful management to ensure that nutrient needs are met for both the coffee crop and any intercropped plants.

In light of these practices, it is crucial to further explore farmers’ perceptions of fertilization, particularly whether they view it as necessary for coffee cultivation or believe that intercropping alone can maintain soil health and productivity. Future studies and outreach programs could focus on educating farmers about balanced fertilization and integrated soil management practices, which could improve both crop yields and sustainability. To enhance sustainability, farmers could benefit from training on soil health management and integrated pest management.

The majority of farmers plant between 500 and 600 coffee trees per hectare, allowing for healthy growth. However, many older farms face challenges in replacing unproductive trees, highlighting the need for proactive management and education on rehabilitation techniques. Conversely, newer farms, averaging 1050 trees per hectare, indicate a shift toward more intensive cultivation and better economic returns. Yield potential is significantly higher at increased tree densities [

41,

42,

43]. This suggests that optimizing tree density in agricultural practices can lead to enhanced productivity, offering valuable insights for farmers aiming to maximize their output while promoting sustainable farming practices. Implementing strategies that focus on higher tree densities could therefore be an effective approach to improving yield in various agricultural systems.

The annual yield data reveal significant challenges, with 43.8% of respondents reporting an average yield of just 0.2 kg per tree, often due to aging trees and inadequate management practices. The Department of Agriculture attributes the ongoing decline in coffee production to several factors, including an increasing number of coffee growers transitioning to other crops, the aging of coffee trees with little to no rejuvenation, and poor farming practices. These practices are often linked to the limited knowledge of appropriate coffee cultivation techniques among farmers, particularly older ones. Additionally, there is a lack of access to certified planting materials and limited availability of credit, further exacerbating the situation [

5]. However, 35% of farmers achieve yields between 0.75 and 0.80 kg per tree, suggesting successful management practices among some. Sharing these best practices could foster knowledge exchange and raise the overall productivity, ultimately impacting farmers’ livelihoods. Enhancing yield through training and improved coffee varieties could significantly stabilize the economic situation for farming households.

4.5. Role of Women in Coffee Production

Women play a vital and multifaceted role in coffee farming in San Isidro and Governor Generoso, Davao Oriental. Their involvement spans the entire coffee production process, from planting to post-harvest activities, including sorting, grading, and marketing. This is consistent with the findings of Imron and Satrya (2019), which show that women share responsibilities throughout coffee production [

44].

In our study, women were identified as key contributors in critical stages such as drying and harvesting. These labor-intensive activities are crucial for maintaining coffee quality, as careful drying conditions preserve flavor profiles and minimize losses due to spoilage or improper processing. Their attention to detail at these stages directly impacts the quality of the final product, highlighting the significant role women play in the success of coffee production. Beyond harvesting and drying, women also participate in other essential tasks, such as grinding, pruning, sorting, and grading. Their involvement in grinding ensures that coffee is prepared for local consumption, which is especially important in rural farming communities. Women also engage in pruning, which helps maintain the health of coffee plants and maximize yields. This task directly contributes to improving the overall productivity and quality of the coffee farm. Additionally, women are heavily involved in sorting and grading, where their expertise ensures that only the best beans are selected for sale. Their attention to detail at these stages not only enhances the reputation of the farm but also contributes to securing higher market prices for coffee. A particularly important aspect of women’s roles is their involvement in marketing, where they interact directly with buyers and traders. Their understanding of local markets and coffee quality enables them to negotiate better prices, which improves the profitability of the farm and strengthens the household and community economic resilience. Women’s ability to manage marketing efforts also plays a significant role in increasing farm income, which is crucial for the long-term sustainability of coffee farming. This multifaceted engagement illustrates women’s adaptability and resourcefulness in the coffee industry [

45]. Their involvement in marketing is particularly important, as effective strategies can boost farmers’ incomes [

46].

Despite often not being formally remunerated for their labor, women gain significant benefits from their participation in coffee farming. Their involvement grants them access to household income, improves their social standing, and enhances their influence in family and community decision-making. In particular, women’s roles in marketing contribute not only to higher incomes for farmers but also to sustainable development at the community level. Women’s extensive contributions to the coffee value chain—from cultivation to post-harvest processes and marketing—highlight their indispensable role in sustaining coffee farming and ensuring its long-term viability. Their expertise and hard work support both the economic and environmental sustainability of coffee farming in the region. To further support and empower women in these critical roles, it is essential to provide targeted training and resources at all stages of coffee production. Doing so will foster gender equity, enhance productivity, and contribute to sustainable development in Davao Oriental.

4.6. Challenges Reported by Coffee Farmers

Farmers identified uncertain prices as a major barrier to sustainable coffee production, alongside poor road conditions and limited transportation options that increase marketing costs. In Governor Generoso, some farmers have switched to other cash crops due to a lack of regular buyers. The results illustrate significant challenges in the coffee supply chain. A large majority (90.5%) of farmers face long distances to buyers, complicating market access and increasing transportation costs, which can lower the income and delay sales. Additionally, 82.6% to 83.8% report difficulties with farm-to-market roads, exacerbating transportation issues and risking post-harvest losses [

47,

48,

49]. The situation is further strained by 39% of farmers lacking buyers for their coffee, threatening their financial stability and discouraging investment in sustainable practices. Addressing these challenges requires improving rural infrastructure, particularly roads, and establishing cooperatives to help farmers negotiate better prices. Initiatives that connect farmers with local and international buyers through digital platforms and provide training in marketing and business skills could also enhance market access and profitability.

4.7. Climate Change Awareness and Adaptation Strategies

The results highlight a significant awareness among respondents regarding the changing weather patterns, which they attribute to climate change and other anthropogenic factors like plastic burning. This collective recognition underscores the urgency of the climate crisis within the farming community, revealing a shared understanding of the challenges they face. The farmers’ definition of climate change—characterized by sudden weather shifts, higher temperatures, and prolonged dry spells—reflects their lived experiences and the direct impact of these changes on their agricultural practices. To adapt to these shifting conditions, the majority of farmers have adopted a diversified cropping strategy, intercropping coffee with a variety of other crops, such as bananas, coconuts, and various fruits and vegetables. This approach not only aims to increase resilience against climate variability but also to enhance income through multiple sources. However, concerns about the potential impact of these additional crops on coffee growth illustrate the complexities of managing a diversified farm. The interplay between crops requires careful consideration of resource allocation, competition for nutrients, and overall ecosystem health. According to Valérie et al. (2024), coffee diversification has been a long-standing practice in the region, well before the current concerns about climate change [

50]. The integration of additional crops into coffee farming provides various benefits, including enhanced biodiversity, improved soil health, and risk mitigation. However, it also introduces complexities in farm management. Farmers must carefully balance resource allocation, manage competition for nutrients, and maintain overall ecosystem health to ensure that diversification does not detract from coffee production. These considerations are particularly important as the introduction of companion crops must complement, rather than hinder, coffee growth. While coffee diversification is not a direct response to climate change, it remains a critical strategy for fostering a sustainable and resilient farming system. By incorporating a diverse range of crops, farmers can maintain farm productivity and ecological balance, ensuring long-term sustainability in coffee farming [

50].

The adaptation strategies employed by the farmers—such as pruning, using ipil-ipil for shade, and employing nets—demonstrate proactive efforts to mitigate the adverse effects of climate change. Pruning can help improve air circulation and light penetration, fostering healthier plants, while providing shade can protect coffee trees from extreme heat [

51,

52,

53]. Using nets can further help shield crops from harsh weather conditions, pests, or diseases. The farmers’ observations of climate change’s effects on coffee production, including late flowering, reduced yields, and increased pest and disease prevalence, provide concrete evidence of the challenges they are encountering [

54,

55]. Symptoms such as wilting leaves, hollow beans, and the dropping of foliage highlight the deteriorating health of coffee plants under stress [

8]. These issues not only threaten the sustainability of coffee farming but also have broader implications for the local economy, as reduced yields directly translate to lower incomes for farmers.

Coffee farmers in Davao Oriental are aware that “bokbok”, or the coffee borer beetle, are the most limiting pests affecting coffee production. While they recognize their impact on yields and plant health, the capacity to control these pests is limited. Most farmers rely on basic control methods, such as manual removal and pruning, but only 12% use chemical pesticides. The low pesticide use is primarily due to the high costs, limited availability, and environmental concerns. Pests and diseases are not controlled not because they are perceived as important but because effective management methods are not accessible. The high costs and inaccessibility of pesticides make it difficult for farmers to address these pests effectively. Climate change further exacerbates pest problems, as rising temperatures and erratic rainfall may expand the range and reproductive cycles of pests like the coffee borer beetle. This could lead to more frequent and severe infestations, reducing yields and threatening the sustainability of coffee production in the region.

5. Conclusions

This study underscores the need for targeted interventions to enhance the sustainability of coffee farming in the Mt. Hamiguitan area, particularly in the face of climate change and aging farmers. Key findings highlight the potential of GIS mapping in promoting sustainable practices while preserving ecological integrity. The survey data reveal that over 42% of coffee farmers are over 60 years old, indicating a pressing need for programs aimed at encouraging younger generations to enter the coffee farming sector. It is essential to implement programs that address this demographic shift, with a focus on rejuvenating the aging coffee plantations and promoting generational change within farming families. Furthermore, there is an urgent need for practical training and technical support to optimize cultivation practices, including soil health, pest management, and the balanced use of fertilizers. To address these challenges, strengthening smallholder farmers through the establishment of cooperatives could be an effective strategy. By consolidating production, these cooperatives would improve farmers’ bargaining power and facilitate better market access. Such organizations would enable farmers to negotiate better prices, improve their overall market position, and share resources, ultimately fostering greater economic stability within the sector. In addition, focused education on modern coffee farming practices, such as rehabilitation techniques, pest management, and climate-resilient practices, is crucial for long-term productivity. Both government and private institutions should collaborate to provide extension services, targeting both older and younger farmers. This collaboration would ensure that farmers at all stages of their careers are equipped with the knowledge and tools to improve farm productivity and sustainability.

Women play a vital role in coffee production and should be further supported through gender-responsive policies and tailored resources. Training programs should be inclusive and designed to enhance women’s involvement in all stages of coffee farming, particularly in areas like marketing and post-harvest activities. By empowering women, we can unlock their potential and enhance the overall sustainability of the coffee industry.

Given the increasing challenges posed by climate change, farmers must be supported in adopting sustainable practices, such as water management, shade crop integration, and the use of climate-resilient coffee varieties. Additionally, exploring financial support mechanisms, such as insurance options, would help farmers manage climate risks and reduce vulnerabilities to unpredictable weather patterns. Rejuvenating the aging coffee plantations is another critical area for intervention. Programs that assist farmers with replanting and modernizing their coffee farms will ensure the continued viability of the coffee sector. Addressing the aging of plantations is vital to maintaining productivity and ensuring the future of coffee farming in the region. Finally, adopting global best practices, such as contract farming and vertical integration used in countries like Vietnam, could be beneficial [

56]. These strategies would help small-scale Filipino coffee farmers integrate into global agricultural markets, improve market access, and increase economic opportunities. By addressing these recommendations, stakeholders can significantly improve productivity, attract younger generations to coffee farming, and promote long-term sustainability in the industry. Collaborative efforts involving farmers, government bodies, and agricultural experts will be essential in creating a robust framework that supports the growth and resilience of the coffee sector.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.B.C.; methodology, P.N.-C., H.P.-B., M.O.G.M. and M.B.C.; software, P.N.-C., H.P.-B., M.O.G.M. and M.B.C.; validation, P.N.-C., H.P.-B., M.O.G.M. and M.B.C.; formal analysis, P.N.-C., H.P.-B., M.O.G.M. and M.B.C.; investigation, P.N.-C., H.P.-B., M.O.G.M. and M.B.C.; resources, P.N.-C., H.P.-B., M.O.G.M. and M.B.C.; data curation, P.N.-C., H.P.-B., M.O.G.M. and M.B.C.; writing—original draft preparation, P.N.-C., H.P.-B., M.O.G.M. and M.B.C.; writing—review and editing, P.N.-C., H.P.-B., M.O.G.M. and M.B.C.; visualization, P.N.-C., H.P.-B., M.O.G.M. and M.B.C.; supervision, M.B.C.; project administration, H.P.-B. and M.B.C.; funding acquisition, M.B.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Department of Trade and Industry XI and the Department of Agriculture—Philippine Rural Development Project. The APC was funded by the authors.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to the involvement of non-invasive data collection methods, such as interviews, which did not pose any physical or psychological risks to participants. The research focused on gathering information about coffee farming practices, women’s roles, and climate change adaptation, which are considered low-risk topics. Participants’ identities and responses were kept confidential, ensuring that their privacy is protected throughout the study. Participation in the study was voluntary, and participants could withdraw at any time without any consequences. Lastly, the study aims to provide valuable insights that can enhance sustainability in coffee farming, benefiting the local community and contributing to broader agricultural practices.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

Textual data supporting this study are included within the article.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the funders and the Davao Oriental State University, whose resources made the study possible.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). Coffee. 2023. Available online: https://www.fao.org/markets-and-trade/commodities-overview/beverages/coffee/en (accessed on 31 October 2024).

- Comunicaffe International. The Philippines: A Nation of Coffee Drinkers. 2015. Available online: https://www.comunicaffe.com/the-philippines-a-nation-of-coffee-drinkers/ (accessed on 31 October 2024).

- Laurico, K.R.; Lee, J.Y.; Lee, B.H.; Kim, J.H. Consumers’ valuation of local specialty coffee: The case of Philippines. J. Korean Soc. Int. Agric. 2021, 33, 338–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philippine Coffee Board. Coffee Consumption Rising. 2017. Available online: https://philcoffeeboard.com/coffee-consumption-rising/ (accessed on 31 October 2024).

- Department of Agriculture. Philippine Coffee Industry Roadmap (2021–2025). 2022. Available online: https://pcaf.da.gov.ph/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/Philippine-Coffee-Industry-Roadmap-2021-2025.pdf (accessed on 31 October 2024).

- Philippine Statistics Authority. Major Non-Food and Industrial Crops Quarterly Bulletin, April–June 2023. 2023. Available online: https://psa.gov.ph/content/major-non-food-and-industrial-crops-quarterly-bulletin-april-june-2023-0 (accessed on 31 October 2024).

- Department of Trade and Industry. DTI-DavOr Promotes Coffee Industry Through ‘Pakape Para sa Konsumante’. 2021. Available online: https://www.dti.gov.ph/archives/regional-archives/region-11-news-archives/dti-davor-promotes-coffee-industry/ (accessed on 31 October 2024).

- Faraz, M.; Mereu, V.; Spano, D.; Trabucco, A.; Marras, S.; El Chami, D. A systematic review of analytical and modelling tools to assess climate change impacts and adaptation on coffee agrosystems. Sustainability 2023, 15, 14582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proença, J.F.; Torres, A.C.; Marta, B.; Silva, D.S.; Fuly, G.; Pinto, H.L. Sustainability in the coffee supply chain and purchasing policies: A case study research. Sustainability 2022, 14, 459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hameed, A.; Hussain, S.A.; Suleria, H.A.R. “Coffee Bean-Related” agroecological factors affecting the coffee. In Co-Evolution of Secondary Metabolites; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 641–705. [Google Scholar]

- Getachew, M.; Tolassa, K.; De Frenne, P.; Verheyen, K.; Tack, A.J.; Hylander, K.; Ayalew, B.; Boeckx, P. The relationship between elevation, soil temperatures, soil chemical characteristics, and green coffee bean quality and biochemistry in southwest Ethiopia. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2022, 42, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’haeze, D.; Deckers, J.; Raes, D.; Phong, T.A.; Loi, H.V. Environmental and socio-economic impacts of institutional reforms on the agricultural sector of Vietnam: Land suitability assessment for Robusta coffee in the Dak Gan region. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2005, 105, 59–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asis, M. Sowing Hope: Agriculture as an Alternative to Migration for Young Filipinos. 2020. Available online: https://icmc.net/future-of-work/report/06-philippines/ (accessed on 31 October 2024).

- Wagner, T.; Compton, R.A. Creating Innovators: The Making of Young People Who Will Change the World, 1st ed.; Simon and Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 1–288. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.; Huang, D.; Ma, Q.; Qi, W.; Li, H. Factors influencing the technology adoption behaviours of litchi farmers in China. Sustainability 2019, 12, 271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eastwood, R.; Lipton, M.; Newell, A. Farm size. Handb. Agric. Econ. 2010, 4, 3323–3397. [Google Scholar]

- Lowder, S.K.; Skoet, J.; Raney, T. The number, size, and distribution of farms, smallholder farms, and family farms worldwide. World Dev. 2016, 87, 16–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, D. Farm size, household size and composition, and women’s contribution to agricultural production: Evidence from Zaire. J. Dev. Stud. 1990, 27, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Launio, C.C.; Luis, J.S.; Angeles, Y.B. Factors influencing adoption of selected peanut protection and production technologies in Northern Luzon, Philippines. Technol. Soc. 2018, 55, 56–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, A.; Shaukat, S.; Tariq, B. Household socio-demographic characteristics and out of pocket educational expenditure in Pakistan. J. Policy Res. 2022, 8, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Feyisa, B.W. Determinants of agricultural technology adoption in Ethiopia: A meta-analysis. Cogent Food Agric. 2020, 6, 1855817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambrecht, I.; Vanlauwe, B.; Merckx, R.; Maertens, M. Understanding the process of agricultural technology adoption: Mineral fertilizer in eastern DR Congo. World Dev. 2014, 59, 132–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ates, H.C.; Terin, M. Farmers’ perceptions of farmer organizations in rural areas. Afr. J. Bus. Manag. 2011, 5, 179. [Google Scholar]

- Miiro, R.F.; Matsiko, F.B.; Mazur, R.E. Training and farmers’ organizations’ performance. J. Agric. Educ. Ext. 2014, 20, 65–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, L.Y.; Sumelius, J. Analysis of the factors of farmers’ participation in the management of cooperatives in Finland. J. Rural Cooper. 2010, 38, 134. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Q.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, F. Exploring mediating factors between agricultural training and farmers’ adoption of drip fertigation system: Evidence from banana farmers in China. Water 2021, 13, 1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barghouti, S.; Kane, S.; Sorby, K.; Mubarik, A. Agricultural diversification for the poor: Guidelines for practitioners (English). In Agriculture and Rural Development Discussion Paper; No. 1; World Bank Group: Washington, DC, USA, 2004; Available online: https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/282611468148152853/pdf/293050REPLACEM00Diversification0Web.pdf (accessed on 31 October 2024).

- Barman, A.; Saha, P.; Patel, S.; Bera, A. Crop diversification an effective strategy for sustainable agriculture development. In Sustainable Crop Production-Recent Advances, 1st ed.; Singh Meena, V., Choudhary, M., Prakash Yadav, R., Kumari Meena, S., Eds.; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2022; pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Chhatre, A.; Devalkar, S.; Seshadri, S. Crop diversification and risk management in Indian agriculture. Decision 2016, 43, 167–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villa, G.; Adenso-Díaz, B.; Lozano, S. An analysis of geographic and product diversification in crop planning strategy. Agric. Syst. 2019, 174, 117–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crews, T.E.; Carton, W.; Olsson, L. Is the future of agriculture perennial? Imperatives and opportunities to reinvent agriculture by shifting from annual monocultures to perennial polycultures. Glob. Sustain. 2018, 1, e11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huss, C.P.; Holmes, K.D.; Blubaugh, C.K. Benefits and risks of intercropping for crop resilience and pest management. J. Econ. Entomol. 2022, 115, 1350–1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ngure, G.M.; Watanabe, K.N. Coffee sustainability: Leveraging collaborative breeding for variety improvement. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2024, 8, 1431849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sengere, R.; Susuke, W.; Allen, B. The Rehabilitation of Coffee Plantations in Papua New Guinea: The Case of Obihaka. 2008. Available online: https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/156649736.pdf (accessed on 31 October 2024).

- Dufour, B.P.; Kerana, I.W.; Ribeyre, F. Effect of coffee tree pruning on berry production and coffee berry borer infestation in the Toba Highlands (North Sumatra). Crop Prot. 2019, 122, 151–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gokavi, N.; Mote, K.; Jayakumar, M.; Raghuramulu, Y.; Surendran, U. The effect of modified pruning and planting systems on growth, yield, labour use efficiency and economics of Arabica coffee. Sci. Hortic. 2021, 276, 109764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somarriba, E.; Quesada, F. Modeling age and yield dynamics in Coffea arabica pruning systems. Agric. Syst. 2022, 201, 103450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrareddy, V.; Kouadio, L.; Mushtaq, S.; Stone, R. Sustainable production of Robusta coffee under a changing climate: A 10-year monitoring of fertilizer management in coffee farms in Vietnam and Indonesia. Agronomy 2019, 9, 499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro-Tanzi, S.; Dietsch, T.; Urena, N.; Vindas, L.; Chandler, M. Analysis of management and site factors to improve the sustainability of smallholder coffee production in Tarrazú, Costa Rica. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2012, 155, 172–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Souza, T.L.; de Oliveira, D.P.; Santos, C.F.; Reis, T.H.P.; Cabral, J.P.C.; da Silva Resende, É.R.; Fernandes, T.L.; de Souza, T.R.; Builes, V.R.; Guelfi, D. Nitrogen fertilizer technologies: Opportunities to improve nutrient use efficiency towards sustainable coffee production systems. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2023, 345, 108317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anim-Kwapong, G.J.; Anim-Kwapong, E.; Oppong, F.K. Evaluation of some robusta coffee (Coffea canephora pierre ex a. Froehner) clones for optimal density planting in Ghana. Afr. J. Agric. Res. 2010, 5, 84–89. [Google Scholar]

- Kiyingi, I.; Gwali, S. Productivity and profitability of robusta coffee agroforestry systems in central Uganda. Uganda J. Agric. Sci. 2012, 13, 85–93. [Google Scholar]

- Sseremba, G.; Kagezi, G.H.; Kobusinge, J.; Musoli, P.; Akodi, D.; Olango, N.; Kucel, P.; Chemutai, J.; Mulindwa, J.; Arinaitwe, G. High Robusta coffee plant density is associated with better yield potential at mixed responses for growth robustness, pests and diseases: Which way for a farmer? Aust. J. Crop Sci. 2021, 15, 494–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imron, D.K.; Satrya, A.R.A. Women and coffee farming: Collective consciousness towards social entrepreneurship in Ulubelu, Lampung. J. Ilmu Sos. Ilmu Polit. 2019, 22, 216–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hailemariam, M. Women participation and decision making on coffee value chain. In Social Science Research Report Series No. 39, 1st ed.; Beyene, S., Ed.; Organisation for Social Science Research in Eastern and Southern Africa: Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2024; pp. 91–116. [Google Scholar]

- Bilfield, A. Coffee, Gender, and Capabilities: A Case Study of Producer and Supply Chain Perspectives on Women in Coffee. Ph.D. Thesis, Tulane University, New Orleans, LA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Chokera, V.N. Challenges Affecting Coffee Marketing by Coffee Firms in Kenya. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Nairobi, Nairobi, Kenya, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Lerner, D.G.; Pereira, H.M.F.; Saes, M.S.M.; Oliveira, G.M.D. When unfair trade is also at home: The economic sustainability of coffee farms. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otieno, H.M.; Alwenge, B.A.; Okumu, O.O. Coffee production challenges and opportunities in Tanzania: The case study of coffee farmers in Iwindi, Msia and Lwati Villages in Mbeya Region. Asian J. Agric. Hortic. Res. 2019, 3, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valérie, P.; Philippe, V.; Clémentine, A. Which diversification trajectories make coffee farming more sustainable? Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2024, 68, 101432. [Google Scholar]

- Ehrenbergerová, L.; Klimková, M.; Cano, Y.G.; Habrová, H.; Lvončík, S.; Volařík, D.; Khum, W.; Němec, P.; Kim, S.; Jelínek, P.; et al. Does shade impact coffee yield, tree trunk, and soil moisture on Coffea canephora plantations in Mondulkiri, Cambodia? Sustainability 2021, 13, 13823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guimarães, R.J.; Borém, F.M.; Shuler, J.; Farah, A.; Peres Romero, J.C. Coffee growing and post-harvest processing. In Coffee: Production, Quality and Chemistry, 1st ed.; Farah, A., Farah, A., Eds.; The Royal Society of Chemistry: London, UK, 2019; pp. 26–88. [Google Scholar]

- Staver, C.; Guharay, F.; Monterroso, D.; Muschler, R.G. Designing pest-suppressive multistrata perennial crop systems: Shade-grown coffee in Central America. Agrofor. Syst. 2001, 53, 151–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, Y.; Reardon-Smith, K.; Mushtaq, S.; Cockfield, G. The impact of climate change and variability on coffee production: A systematic review. Clim. Chang. 2019, 156, 609–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, E.; Antoshak, L.; Brown, P.H. Grounds for collaboration: A model for improving coffee sustainability initiatives. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung Anh, N.; Bokelmann, W.; Thi Thuan, N.; Thi Nga, D.; Van Minh, N. Smallholders’ preferences for different contract farming models: Empirical evidence from sustainable certified coffee production in Vietnam. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |