ESG-SDG Nexus: Assessing How Top Integrated Oil and Gas Companies Align Corporate Sustainability Practices with Global Goals

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. The Inputs–Intentions–Outcomes Framework: Conceptual Foundations

2.2. Theoretical Mechanisms and Boundary Conditions

3. Literature Review

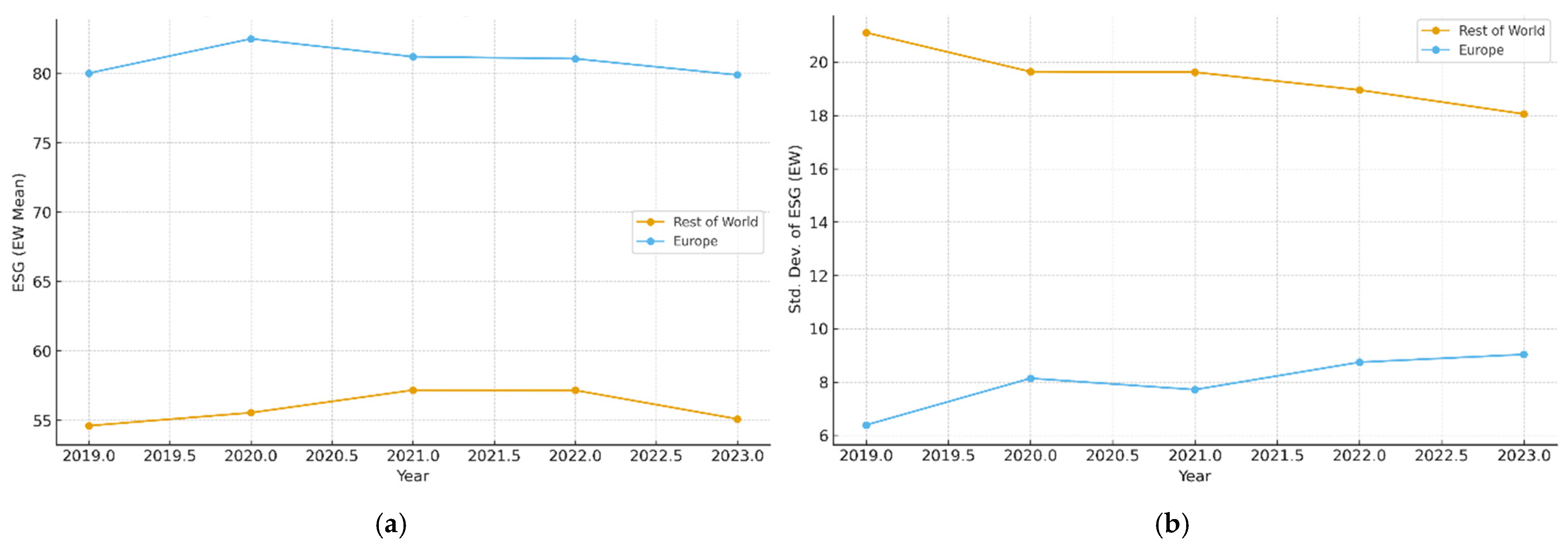

3.1. ESG in the Oil and Gas Sector: Temporal Evolutions and Regional Dynamics

3.2. Pillar Contributions and Interrelationships

3.3. ESG and SDG Commitments: Alignment and Integration

3.4. Environmental Innovation and Green Revenue Monetization

3.5. ESG Strategic Archetypes and Typologies

3.6. National ESG Frameworks and Corporate Governance

3.7. ESG Controversies and ESGC Impact

3.8. Research Gaps and Study Positioning

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Research Design: The Census Approach

4.2. Data and Variables

- ESG Score: An aggregate measure (0–100) based on company-reported metrics across three pillars (environmental, social, governance). According to LSEG methodology, this measures a company’s relative ESG performance based on verifiable reported data.

- ESGC Score: The ESG Score discounted by ESG Controversies. LSEG overlays the ESG Score with controversy data derived from global media sources (lawsuits, spills, strikes). The difference between ESG and ESGC serves as a “controversy penalty”. This captures the extent to which negative incidents undermine firms’ baseline sustainability performance.

- SDG Commitments: A binary count (0–17) of the Sustainable Development Goals the company has publicly committed to in its annual reporting. Accordingly, SDG counts are interpreted as indicators of strategic orientation rather than measures of substantive SDG impact.

- Green Revenues: The percentage of total revenue derived from products and services classified as “green” under the FTSE Russell Green Revenues 2.0 data model. This serves as the outcome variable. We note that analyses involving Green Revenues were conducted on a sample of N = 17, as companies with missing data in the source dataset were excluded.

- Environmental Innovation Score: A subpillar of the environmental score reflecting R&D and product innovation capacity.

- Country HQ ESG Score (as a proxy for sustainability context, 2023).

- Market capitalization and regional dummy (Europe vs. the rest of the world).

4.3. Data Processing

4.4. Analytical Procedures

4.5. Reliability and Ethics

5. Results

5.1. ESG Evolution (2019–2023) and Regional Patterns

5.2. Pillar Contributions and Interrelationships

5.3. ESG and SDG Commitments

- Maximum Intention (17 SDGs): Firms like Shell PLC (ESG 90.23), Eni SpA (ESG 84.10), and Galp Energia (ESG 68.45) committed to all 17 SDGs. These are predominantly European firms.

- Selective Intention: Saudi Aramco (ESG 57.75) committed to 12 SDGs, focusing on economic goals (SDGs 8 and 9) and climate (SDG 13) while omitting others. This reflects a strategic, resource-constrained approach typical of an “Emergent Transitioner”.

- Low Intention: Cenovus Energy (ESG 58.08) committed to only two SDGs in 2023.

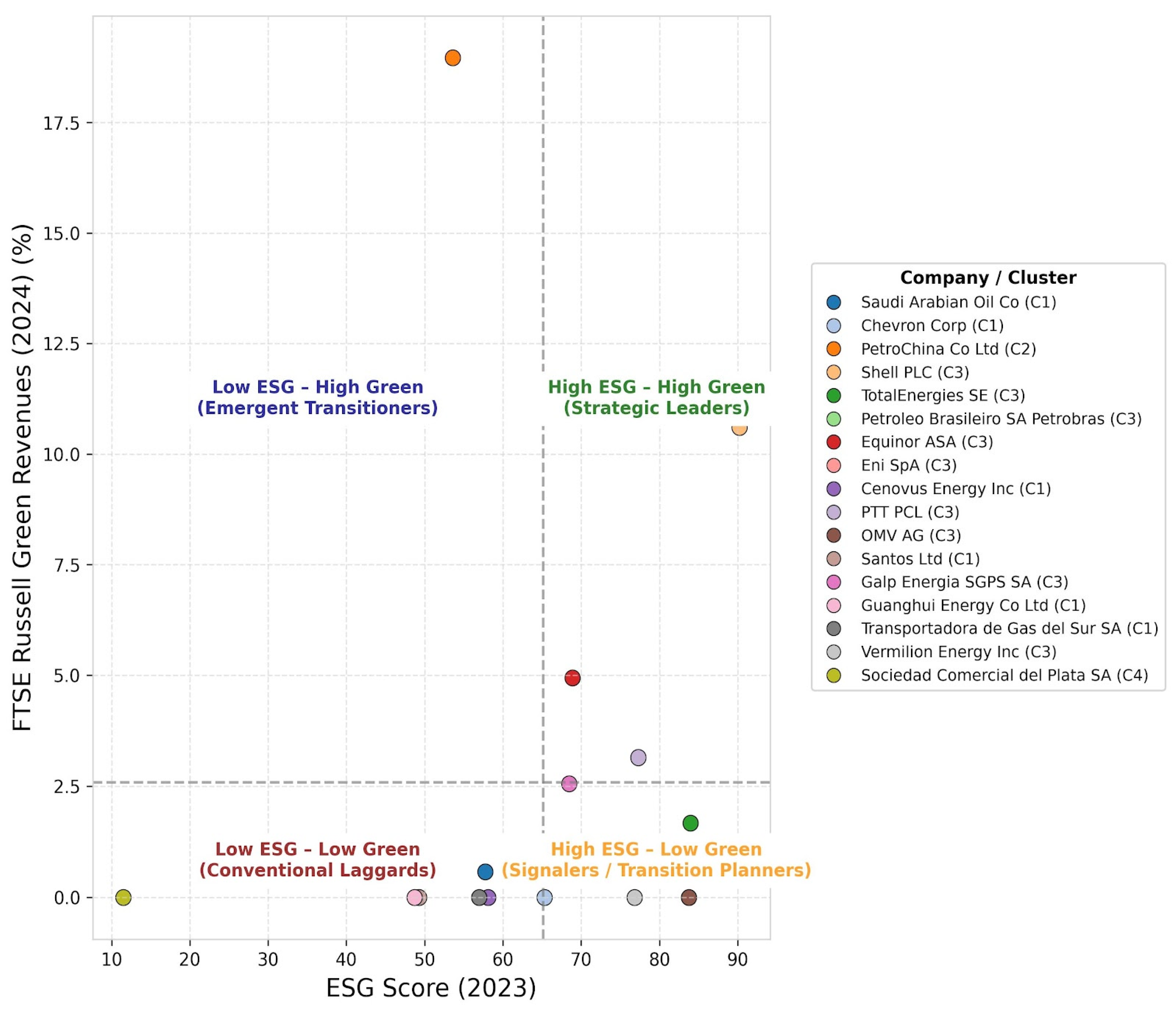

5.4. Environmental Innovation and Green Revenues

5.5. ESG–Green Revenues Archetypes

- High ESG—High Green (Strategic Leaders). Firms in the upper-right quadrant exhibit both strong ESG performance and a high share of Green Revenues. Typically, these are large, European-headquartered companies that have embedded sustainability within core operations. Their performance suggests mature ESG systems that translate directly into marketable green products or services. Examples include companies such as Shell PLC, Equinor ASA, or PTT PLC. Firms in this quadrant exhibit concurrent high ESG Scores and higher Green Revenue shares, suggesting a closer alignment between ESG performance and monetized outcomes.

- High ESG—Low Green (Signalers or Transition Planners). Organizations in the lower-right quadrant maintain strong ESG credentials but have yet to realize substantial Green Revenue outcomes (e.g., OMV AG, TotalEnergies SE, and Vermilion Energy Inc.). Their profile shows that they may be in earlier stages of strategic transition, where sustainability ambition and disclosure outpace the commercial deployment of green products or services.

- Low ESG—High Green (Emergent Transitioners). Companies located in the upper-left quadrant report relatively lower ESG Scores yet achieve comparatively higher Green Revenues. These firms appear to commercialize green technologies or services despite limited ESG disclosure sophistication. Their strategy may prioritize technological innovation over formal ESG frameworks. As such, they represent an under-recognized transition path—achieving tangible sustainability impacts without parallel reporting infrastructure. In this quadrant there is only one company: PetroChina Co Ltd. This unique archetype suggests that “doing green” (revenue) does not always require “reporting green” (ESG Scores). It implies that in some markets (like China), transition is operational rather than informational.

- Low ESG—Low Green (Conventional Laggards). Firms in the bottom-left quadrant underperform on both ESG metrics and Green Revenue generation (e.g., Cernovus Energy Inc. (Calgary, AB, Canada), Guanghui Energy Co Ltd., Santos Ltd., Saudi Arabian Oil Co, and Transportadora de Gas del Sur SA). Their business models remain heavily carbon-intensive, and sustainability reporting is limited or fragmented. This group illustrates the traditional hydrocarbon-centric profile. Persistent controversies and weaker governance systems tend to depress both ESGC and ESG Scores. These firms remain tethered to the traditional extraction model, treating green economy factors primarily as costs to be minimized rather than resources to be leveraged.

5.6. National ESG Frameworks and Corporate Governance

- European cluster: Firms’ HQ in Europe (Avg Country ESG ~80) have an average governance score of 75.76.

- Rest of the world: Firms’ HQ elsewhere (Avg Country ESG ~60) have an average governance score of 65.23.

5.7. Controversies and ESGC Impact

6. Discussion

6.1. ESG Performance Trends

6.2. Pillar Contributions and Interrelationships: Governance as Enabler

6.3. ESG–SDG Alignment

6.4. Innovation as a Transition Mechanism

6.5. ESG–Green Revenues Typologies and Strategic Differentiation

6.6. National ESG Frameworks and Corporate Governance

6.7. Controversies and ESG Credibility

7. Conclusions

7.1. Key Findings and Implications

7.2. Limitations and Directions for Future Research

- The analysis relies on LSEG-reported data, which, while standardized, may not capture unreported sustainability activities or firm-specific methodological nuances. Moreover, results may reflect methodological choices that differ from other ESG ratings, potentially leading to different outcomes.

- The five-year panel (2019–2023) limits the ability to observe longer-term transition trajectories. Future studies could extend the timeframe as Green Revenues and SDG reporting mature. Also, given that the current landscape—with evolving regulatory and market context—may signal an inflection point for corporate sustainability, extended time-series analyses would offer clearer insights.

- The focus on integrated oil and gas firms limits generalizability. Sustainability dynamics can differ not only across energy subsectors but also across unrelated industries, where ESG pillars manifest differently. While these companies play a major role in global energy markets and sustainability disclosure practices, the exclusion of smaller firms and those headquartered in underrepresented regions limit the generalizability of the results.

- Although the study leverages standardized ESG- and SDG-related indicators to ensure comparability, such quantitative measures cannot fully capture the strategic intent or internal decision-making processes underlying sustainability commitments. Future research integrating qualitative analyses (based on sustainability reports or executive interviews) could further differentiate between symbolic alignment and substantive strategic transformation.

- The small clustering sample (N = 17), which yielded only a 2 × 2 matrix (built on ESG Scores and Green Revenues while not comprising SGD breath), may have limited the detection of more granular patterns. As data availability improves (especially in light of the emerging and still-evolving nature of Green Revenue classification and reporting), future research could rely on larger and more diverse samples and apply alternative clustering approaches that incorporate additional dimensions (such as SDG depth or controversy exposure), to identify more detailed and stable sustainability patterns across firms and industries.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Energy Institute. Resources and Data Downloads. Available online: https://www.energyinst.org/statistical-review/resources-and-data-downloads (accessed on 12 November 2025).

- Tieso, I. Topic: Oil and Gas Industry Emissions Worldwide. Available online: https://www.statista.com/topics/10956/oil-and-gas-industry-emissions-worldwide/ (accessed on 12 November 2025).

- BloombergNEF. Energy Transition Investment Trends; BloombergNEF: London, UK, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Dimitriou, D.; Sartzetaki, M.; Karagkouni, A.; Efstratiou, V. Corporate Strategy for Sustainable Development in the Oil and Gas Industry: Drivers, Agility Mechanisms, and SDG Alignment. J. Sustain. Res. 2025, 7, e250061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escrig-Olmedo, E.; Fernández-Izquierdo, M.Á.; Ferrero-Ferrero, I.; Rivera-Lirio, J.M.; Muñoz-Torres, M.J. Rating the Raters: Evaluating How ESG Rating Agencies Integrate Sustainability Principles. Sustainability 2019, 11, 915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; He, Y. The Impact of ESG Performance on Green Technology Innovation: A Moderating Effect Based on Digital Transformation. Sustainability 2025, 17, 3170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taddeo, S.; Agnese, P.; Busato, F. Rethinking the Effect of ESG Practices on Profitability through Cross-Dimensional Substitutability. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 352, 120115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Falco, S.E.; Montera, R.; Leo, S.; Laviola, F.; Vito, P.; Sardanelli, D.; Basile, G.; Nevi, G.; Alaia, R. Trends and Patterns in ESG Research: A Bibliometric Odyssey and Research Agenda. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2024, 31, 3703–3723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Amate, A.; Ramírez-Orellana, A.; Rojo-Ramírez, A.A.; Casado-Belmonte, M.P. Do ESG Controversies Moderate the Relationship between CSR and Corporate Financial Performance in Oil and Gas Firms? Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2023, 10, 749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kathan, M.C.; Utz, S.; Dorfleitner, G.; Eckberg, J.; Chmel, L. What You See Is Not What You Get: ESG Scores and Greenwashing Risk. Finance Res. Lett. 2025, 74, 106710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Zanten, J.A. Measuring Companies’ Environmental and Social Impacts: An Analysis of ESG Ratings and SDG Scores. Organ. Environ. 2025, 3, 403–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lublóy, Á.; Keresztúri, J.L.; Berlinger, E. Quantifying Firm-Level Greenwashing: A Systematic Literature Review. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 373, 123399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Xu, X. Can ESG Rating Reduce Corporate Carbon Emissions?–An Empirical Study from Chinese Listed Companies. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 434, 140226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, H.; Qin, Z.; Li, J. ESG Performance and Corporate Carbon Emission Intensity: Based on Panel Data Analysis of A-Share Listed Companies. Front. Environ. Sci. 2024, 12, 1483237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horobet, A.; Bulai, V.; Rădulescu, M.; Belascu, L.; Dumitrescu, D.G. ESG Actions, Corporate Discourse, and Market Assessment Nexus: Evidence from the Oil and Gas Sector. J. Bus. Econ. Manag. 2024, 25, 153–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez-Orellana, A.; Martínez-Victoria, M.C.; García-Amate, A.; Rojo-Ramírez, A.A. Is the Corporate Financial Strategy in the Oil and Gas Sector Affected by ESG Dimensions? Resour. Policy 2023, 81, 103303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, M.R.; Rolo, A.; Matos, D.; Carvalho, L. The Circular Economy in Corporate Reporting: Text Mining of Energy Companies’ Management Reports. Energies 2023, 16, 5791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arena, M.; Azzone, G.; Ratti, S.; Urbano, V.M.; Vecchio, G. Sustainable Development Goals and Corporate Reporting: An Empirical Investigation of the Oil and Gas Industry. Sustain. Dev. 2023, 31, 12–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J.B.; Arikan, A.M. The Resource-Based View: Origins and Implications. In The Blackwell Handbook of Strategic Management; Blackwell Publishers Ltd.: Oxford, UK, 2005; pp. 123–182. [Google Scholar]

- Hart, S.L. A Natural-Resource-Based View of the Firm. Acad. Manage. Rev. 1995, 20, 986–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiMaggio, P.J.; Powell, W.W. The Iron Cage Revisited: Institutional Isomorphism and Collective Rationality in Organizational Fields. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1983, 48, 147–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, J.W.; Rowan, B. Institutionalized Organizations: Formal Structure as Myth and Ceremony. Am. J. Sociol. 1977, 83, 340–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spence, M. Job Market Signaling. In Uncertainty in Economics; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1978; pp. 281–306. [Google Scholar]

- Connelly, B.L.; Certo, S.T.; Ireland, R.D.; Reutzel, C.R. Signaling Theory: A Review and Assessment. J. Manag. 2011, 37, 39–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, R.E. Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2010; ISBN 0-521-15174-0. [Google Scholar]

- Donaldson, T.; Preston, L.E. The Stakeholder Theory of the Corporation: Concepts, Evidence, and Implications. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 65–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flammer, C. Corporate Social Responsibility and Shareholder Reaction: The Environmental Awareness of Investors. Acad. Manag. J. 2013, 56, 758–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lins, K.V.; Servaes, H.; Tamayo, A. Social Capital, Trust, and Firm Performance: The Value of Corporate Social Responsibility during the Financial Crisis. J. Finance 2017, 72, 1785–1824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amit, R.; Schoemaker, P.J. Strategic Assets and Organizational Rent. Strateg. Manag. J. 1993, 14, 33–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D.J.; Pisano, G.; Shuen, A. Dynamic Capabilities and Strategic Management. Strateg. Manag. J. 1997, 18, 509–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tashman, P.; Marano, V.; Kostova, T. Walking the Walk or Talking the Talk? Corporate Social Responsibility Decoupling in Emerging Market Multinationals. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2019, 50, 153–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darnall, N.; Ji, H.; Iwata, K.; Arimura, T.H. Do ESG Reporting Guidelines and Verifications Enhance Firms’ Information Disclosure? Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2022, 29, 1214–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heras-Saizarbitoria, I.; Urbieta, L.; Boiral, O. Organizations’ Engagement with Sustainable Development Goals: From Cherry-picking to SDG-washing? Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2022, 29, 316–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nureen, N.; Nuţă, A.C. Envisioning the Invisible: Unleashing the Interplay between Green Supply Chain Management and Green Human Resource Management: An Ability-Motivation-Opportunity Theory Perspective towards Environmental Sustainability. J. Compr. Bus. Adm. Res. 2024, 1, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delmas, M.A.; Toffel, M.W. Organizational Responses to Environmental Demands: Opening the Black Box. Strateg. Manag. J. 2008, 29, 1027–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truong, T.H.; Lin, B.-W.; Lo, C.-H.; Tung, C.-P.; Chao, C.-W. Possible Pathways for Low Carbon Transitions: Investigating the Efforts of Oil Companies in CCUS Technologies. Energy Strategy Rev. 2024, 54, 101421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Waal, J.W.; Thijssens, T. Corporate Involvement in Sustainable Development Goals: Exploring the Territory. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 252, 119625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahn, T.; Pinkse, J.; Preuss, L.; Figge, F. Tensions in Corporate Sustainability: Towards an Integrative Framework. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 127, 297–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marquis, C.; Toffel, M.W.; Zhou, Y. Scrutiny, Norms, and Selective Disclosure: A Global Study of Greenwashing. Organ. Sci. 2016, 27, 483–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, D.L.; Kolk, A. Strategic Responses to Global Climate Change: Conflicting Pressures on Multinationals in the Oil Industry. Bus. Polit. 2002, 4, 275–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundarasen, S.; Rajagopalan, U.; Zyznarska-Dworczak, B. Sustainability Reporting as a Governance Tool for Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs): A Bibliometric and Content Analysis. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gentile, G.; Gupta, J. Orchestrating the Narrative: The Role of Fossil Fuel Companies in Delaying the Energy Transition. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2025, 212, 115359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dongo, D.F.; Relvas, S. Evaluating the Role of the Oil and Gas Industry in Energy Transition in Oil-Producing Countries: A Systematic Literature Review. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2025, 120, 103905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, L.C.; Longo, M.; Mura, M. From Carbon Dependence to Renewables: The European Oil Majors’ Strategies to Face Climate Change. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2023, 32, 1248–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westphal, J.D.; Zajac, E.J. Decoupling Policy from Practice: The Case of Stock Repurchase Programs. Adm. Sci. Q. 2001, 46, 202–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, D.M.; Serafeim, G.; Sikochi, A. Why Is Corporate Virtue in the Eye of the Beholder? The Case of ESG Ratings. Account. Rev. 2022, 97, 147–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, C.; Nyberg, D. An Inconvenient Truth: How Organizations Translate Climate Change into Business as Usual. Acad. Manage. J. 2017, 60, 1633–1661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, A.D.; Tsui, A.S.; Hinings, C.R. Configurational Approaches to Organizational Analysis. Acad. Manage. J. 1993, 36, 1175–1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labella-Fernández, A. Archetypes of Green-Growth Strategies and the Role of Green Human Resource Management in Their Implementation. Sustainability 2021, 13, 836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubio-Andrés, M.; Abril, C. Sustainability Oriented Innovation and Organizational Values: A Cluster Analysis. J. Technol. Transf. 2024, 49, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, J.L. Why Would Corporations Behave in Socially Responsible Ways? An Institutional Theory of Corporate Social Responsibility. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2007, 32, 946–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matten, D.; Moon, J. “Implicit” and “Explicit” CSR: A Conceptual Framework for a Comparative Understanding of Corporate Social Responsibility. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2008, 33, 404–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukács, B.; Molnár, P. Companies’ ESG Performance under Soft and Hard Regulation Environment. Discov. Sustain. 2025, 6, 701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopal, S.; Pitts, J. Regulation and Frameworks: Current and Future Reporting Trends. In The FinTech Revolution: Bridging Geospatial Data Science, AI, and Sustainability; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2025; pp. 183–224. [Google Scholar]

- Chrysikopoulos, S.K.; Chountalas, P.T.; Georgakellos, D.A.; Lagodimos, A.G. Decarbonization in the Oil and Gas Sector: The Role of Power Purchase Agreements and Renewable Energy Certificates. Sustainability 2024, 16, 6339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yetunde, A.A.; Augusta, H.I.; Jephta, M.K.; Andrew, E.E. Energy Transition in the Oil and Gas Sector: Business Models for a Sustainable Future. Int. J. Manag. Entrep. Res. 2024, 6, 3180–3208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borges, F.M.; Rampasso, I.S.; Quelhas, O.L.; Leal Filho, W.; Anholon, R. Addressing the UN SDGs in Sustainability Reports: An Analysis of Latin American Oil and Gas Companies. Environ. Chall. 2022, 7, 100515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emma, G.-M.; Jennifer, M.-F. Is SDG Reporting Substantial or Symbolic? An Examination of Controversial and Environmentally Sensitive Industries. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 298, 126781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatri, I.; Kjærland, F. Sustainability Reporting Practices and Environmental Performance amongst Nordic Listed Firms. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 418, 138172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz-Rainey, I.; Griffin, P.A.; Lont, D.H.; Mateo-Márquez, A.J.; Zamora-Ramírez, C. Shareholder Activism on Climate Change: Evolution, Determinants, and Consequences. J. Bus. Ethics 2024, 193, 481–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Linnenluecke, M.; Smith, T. Shareholder Activism, Divestment, and Sustainability. Account. Finance 2025, 65, 1188–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoepner, A.G.; Oikonomou, I.; Sautner, Z.; Starks, L.T.; Zhou, X.Y. ESG Shareholder Engagement and Downside Risk. Rev. Finance 2024, 28, 483–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PricewaterhouseCoopers. PwC’s Global CSRD Survey 2024. Available online: https://www.pwc.com/gx/en/issues/esg/global-csrd-survey.html (accessed on 18 December 2025).

- U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. SEC Votes to End Defense of Climate Disclosure Rules. Available online: https://www.sec.gov/newsroom/press-releases/2025-58 (accessed on 18 December 2025).

- Yucel, M.; Yucel, S. Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) Dynamics in the Energy Sector: Strategic Approaches for Sustainable Development. Energies 2024, 17, 6291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IFRS Foundation. Progress on Corporate Climate-Related Disclosures—2024 Report; IFRS Foundation: London, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Aldhaferi, K. Challenges of Estimating Future Liabilities of Asset Retirement Obligations in Upstream Oil and Gas: A Literature Review. SPE J. 2025, 30, 1449–1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhodhi, G. Double Materiality Assessment, Implications for the Oil and Gas Sector. In Proceedings of the SPE International Health, Safety, Environment and Sustainability Conference and Exhibition, SPE, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 10 September 2024; p. D031S022R002. [Google Scholar]

- Gray, S.J.; Hellman, N.; Ivanova, M.N. Extractive Industries Reporting: A Review of Accounting Challenges and the Research Literature. Abacus 2019, 55, 42–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eccles, R.G.; Klimenko, S. The Investor Revolution. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2019, 97, 106–116. [Google Scholar]

- Frynas, J.G. Corporate Social Responsibility and Societal Governance: Lessons from Transparency in the Oil and Gas Sector. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 93, 163–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du Toit, E. Thirty Years of Sustainability Reporting: Insights, Gaps and an Agenda for Future Research through a Systematic Literature Review. Sustainability 2024, 16, 10750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palacios, L.; Caricati, C.V. Assessing ESG Risks in National Oil Companies; Columbia University CGEP: New York, NY, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Capello, M.A. Mitigating Scope 3 Emissions in Oil and Gas: An Updated Summary. In Proceedings of the Second International Meeting for Applied Geoscience & Energy, Houston, TX, USA, 28 August–1 September 2022; pp. 3321–3325. [Google Scholar]

- Emborg, M.; Olsen, S. Meeting Increasing Demands for Upstream Scope 3 Reporting: A Framework for the Drilling Industry. SPE J. 2024, 29, 5207–5220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Vega, S.; Hoepner, A.G.; Rogelj, J.; Schiemann, F. Abominable Greenhouse Gas Bookkeeping Casts Serious Doubts on Climate Intentions of Oil and Gas Companies. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2305.11906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adibian, M.S.; Homayoun, S.; ArminKia, A.; Salehi, M. A Comparative Analysis of National Energy Performance and Its Impact on ESG Disclosures in US and European Companies. Bus. Strategy Dev. 2025, 8, e70191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherepovitsyn, A.; Rutenko, E. Strategic Planning of Oil and Gas Companies: The Decarbonization Transition. Energies 2022, 15, 6163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lodh, A. Why Energy Firms’ Performance Varied: US vs. Europe. MSCI. Available online: https://www.msci.com/research-and-insights/quick-take/why-energy-firms-performance-varied-us-vs-europe (accessed on 22 November 2025).

- Hecquet, J.-B.; Assogbavi, P.-A.; Mattar, J.-L.; Tardet, M.; Brette, Q. Is the Oil and Gas Industry Ready for Climate Challenge? Balancing Core Operations with Energy Transition Initiatives; Sia Partners: Paris, France, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Shokhitbayev, M.; Nair, R. Oil and Gas Sector: Contrasting IOC Low-Carbon Capex Strategies Change Risk Profiles. Scope Ratings. European Rating Agency. Available online: https://scoperatings.com/ratings-and-research/research/EN/175501 (accessed on 22 November 2025).

- Holland, B. Path to Net Zero: European, Canadian Oil and Gas Companies Outpace US Counterparts. Available online: https://www.spglobal.com/commodity-insights/en/news-research/latest-news/electric-power/111323-path-to-net-zero-european-canadian-oil-and-gas-companies-outpace-us-counterparts (accessed on 22 November 2025).

- McKinsey & Company. ESG Ratings; McKinsey & Company: New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Mashayekhi, B.; Asiaei, K.; Rezaee, Z.; Jahangard, A.; Samavat, M.; Homayoun, S. The Relative Importance of ESG Pillars: A Two-step Machine Learning and Analytical Framework. Sustain. Dev. 2024, 32, 5404–5420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Y.; Rosli, R. Exploring Determinants of Environmental, Social, and Governance Scores for Listed Firms: An Organizational Context. J. Gov. Regul. 2024, 13, 207–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, F.; Kölbel, J.F.; Rigobon, R. Aggregate Confusion: The Divergence of ESG Ratings. Rev. Finance 2022, 26, 1315–1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Behind ESG Ratings: Unpacking Sustainability Metrics; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Huy, N.Q.; Duy, D.D.; Tien, N.T.T. Governance in ESG of Oil and Gas Sector. Petrovietnam J. 2024, 6, 88–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grecu, V. The Global Sustainability Index: An Instrument for Assessing the Progress Towards the Sustainable Organization. ACTA Univ. Cibiniensis 2015, 67, 215–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grecu, V.; Nate, S. Managing Sustainability with Eco-Business Intelligence Instruments. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2014, 6, 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grecu, V.; Ciobotea, R.-I.-G.; Florea, A. Software Application for Organizational Sustainability Performance Assessment. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radu, O.-M.; Dragomir, V.D.; Ionescu-Feleagă, L. The Link between Corporate ESG Performance and the UN Sustainable Development Goals. Proc. Int. Conf. Bus. Excell. 2023, 17, 776–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menéndez-Sánchez, J.; Fernández-Gómez, J.; Araujo-de-la-Mata, A. Understanding the Role of Oil and Gas Companies in the Current Sustainability Trends: An Application of the Sustainable Business Model Archetypes. Camb. J. Reg. Econ. Soc. 2025, 18, 57–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurgita, B.; Namita, N. Assessing Corporate SDG Alignment: Identifying Gaps and Opportunities. MSCI. Available online: https://www.msci.com/research-and-insights/paper/assessing-corporate-sdg-alignment-identifying-gaps-and-opportunities (accessed on 22 November 2025).

- United Nations Development Programme. Mapping the Oil and Gas Industry to the SDGs: An Atlas. Available online: https://www.undp.org/publications/mapping-oil-and-gas-industry-sdgs-atlas (accessed on 22 November 2025).

- European Commission. EU Taxonomy for Sustainable Activities-Finance-European Commission. Available online: https://finance.ec.europa.eu/sustainable-finance/tools-and-standards/eu-taxonomy-sustainable-activities_en (accessed on 22 November 2025).

- Wei, W.; Dan, L. Research on the Influence of Enterprise ESG Performance on Green Technology Innovation Performance Under Digital Transformation. Adv. Manag. Intell. Technol. 2025, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, X.; Li, L.; Chen, J.; Luo, T. How Does Digital Technology Innovation Quality Empower Corporate ESG Performance? The Roles of Digital Transformation and Digital Technology Diffusion. Systems 2025, 13, 929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FTSE Russell. FTSE Green Revenues Classification System (Methodology); FTSE Russell: London, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Quaye, E.; Tunaru, D.; Tunaru, R. Green-Adjusted Share Prices: A Comparison between Standard Investors and Investors with Green Preferences. J. Financ. Stab. 2024, 74, 101314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruse, T.; Mohnen, M.; Pope, P.F.; Sato, M. Green Revenues, Profitability and Market Valuation: Evidence from a Global Firm Level Dataset; Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment (LSE): London, UK; Centre for Climate Change Economics and Policy (CCCEP): London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Lewellyn, K.; Muller-Kahle, M. ESG Leaders or Laggards? A Configurational Analysis of ESG Performance. Bus. Soc. 2024, 63, 1149–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şahin, Ö.; Bax, K.; Czado, C.; Paterlini, S. Environmental, Social, Governance Scores and the Missing Pillar—Why Does Missing Information Matter? Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2022, 29, 1782–1798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahi, A.F.; Chowdhury, M.A.F.; Johansson, J.; Blomkvist, M. Nexus between Institutional Quality and Corporate Sustainable Performance: European Evidence. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 382, 135188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, Z.; Bashir, Y.; Ahmed, B.; Rocha, A.; Tan-Hwang Yau, J. Role of Country Governance between Sustainable Development and Firm Value in Emerging Markets. Discov. Sustain. 2025, 6, 261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, H.; Mohd-Rashid, R.; Ooi, C.-A. Corruption at Country and Corporate Levels: Impacts on Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) Performance of Chinese Listed Firms. J. Money Laund. Control 2024, 27, 559–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huq, F.A.; Stevenson, M. Implementing Socially Sustainable Practices in Challenging Institutional Contexts: Building Theory from Seven Developing Country Supplier Cases. J. Bus. Ethics 2020, 161, 415–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilera, R.V.; Jackson, G. The Cross-National Diversity of Corporate Governance: Dimensions and Determinants. Acad. Manage. Rev. 2003, 28, 447–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostova, T.; Roth, K. Adoption of an Organizational Practice by Subsidiaries of Multinational Corporations: Institutional and Relational Effects. Acad. Manage. J. 2002, 45, 215–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, C.; Jiang, H. The Influence of Host Country’s Environmental Regulation on Enterprises’ Risk Preference of Multinational Investment. Front. Environ. Sci. 2021, 9, 667633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Kou, J. Acquirer ESG, Home Country Policy Enforcement, Country Distance, and Cross-Border Mergers and Acquisitions: Evidence from Chinese Firms. J. Compr. Bus. Adm. Res. 2025, 2, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palacios, D.L. The Impact of ESG on National Oil Companies; Columbia University CGEP: New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Mammadov, A.; Roman, P. Evaluation of ESG-Strategies of Oil and Gas Companies. Eur. J. Energy Res. 2025, 5, 15–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aouadi, A.; Marsat, S. Do ESG Controversies Matter for Firm Value? Evidence from International Data. J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 151, 1027–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, M.P.; Lodhia, S. The BP Gulf of Mexico Oil Spill: Exploring the Link between Social and Environmental Disclosures and Reputation Risk Management. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 140, 1287–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilhan, E.; Sautner, Z.; Vilkov, G. Carbon Tail Risk. Rev. Financ. Stud. 2021, 34, 1540–1571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capelle-Blancard, G.; Petit, A. Every Little Helps? ESG News and Stock Market Reaction. J. Bus. Ethics 2019, 157, 543–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serafeim, G.; Yoon, A. Which Corporate ESG News Does the Market React To? Harvard Business School: Boston, MA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- S & P Global. S&P Global ESG Scores: Methodology: Sustainable1–November 2025; S&P Global: New York, NY, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- London Stock Exchange Group Data & Analytics. Environmental, Social and Governance Scores from LSEG: Methodology (ESG Scores Guide) 2024; London Stock Exchange Group Data & Analytics: London, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis, 8th ed.; Cengage: Andover, UK, 2019; ISBN 978-1-4737-5654-0. [Google Scholar]

- Menard, S.W. Longitudinal Research; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2002; Volume 76, ISBN 0-7619-2209-1. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Economic and Social Affairs-Sustainable Development. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/goals (accessed on 12 November 2025).

- Khaled, R.; Ali, H.; Mohamed, E.K. The Sustainable Development Goals and Corporate Sustainability Performance: Mapping, Extent and Determinants. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 311, 127599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leoni, L. Integrating ESG and Organisational Resilience through System Theory: The ESGOR Matrix. Manag. Decis. 2024, 63, 401–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FTSE Russell. Green Revenues 2.0 Data Model; FTSE Russell: London, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Green, J.; Hadden, J.; Hale, T.; Mahdavi, P. Transition, Hedge, or Resist? Understanding Political and Economic Behavior toward Decarbonization in the Oil and Gas Industry. Rev. Int. Polit. Econ. 2022, 29, 2036–2063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Yang, Y.; Bradshaw, M.; Wang, C.; Blondeel, M. Globalization and Decarbonization: Changing Strategies of Global Oil and Gas Companies. WIREs Clim. Change 2023, 14, e849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaizen Institute. ESG in the Oil & Gas Sector: Trends, Challenges and Opportunities. Available online: https://kaizen.com/th/insights-th/esg-oil-gas-opportunities-challenges/ (accessed on 5 December 2025).

- Adiwardhana, G.; Rahmawati, R.; Khresna, B.S.; Prasetyani, D.; Kurniawati, E.M.; Jayanti, R.D. Impact of Environment, Social, and Governance Pillars on Firm Value in Oil and Gas Sector. Int. J. Energy Econ. Policy 2025, 15, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPIECA. Sustainability Reporting Guidance for the Oil and Gas Industry. Available online: https://www.ipieca.org/resources/sustainability-reporting-guidance (accessed on 23 November 2025).

- European Union. Directive (EU) 2022/2464 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 14 December 2022 Amending Regulation (EU) No 537/2014, Directive 2004/109/EC, Directive 2006/43/EC and Directive 2013/34/EU, as Regards Corporate Sustainability Reporting (Text with EEA Relevance); European Union: Luxembourg, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Rosati, F.; Faria, L.G.D. Business Contribution to the Sustainable Development Agenda: Organizational Factors Related to Early Adoption of SDG Reporting. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2019, 26, 588–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esiri, A.E.; Sofoluwe, O.O.; Ukato, A. Aligning Oil and Gas Industry Practices with Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Int. J. Appl. Res. Soc. Sci. 2024, 6, 1215–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, N.M.; Nguyen, P.A.; Luan, N.V.; Tam, N.M. Impact of Green Innovation on Environmental Performance and Financial Performance. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2023, 26, 17083–17104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harb, R.; Laçin, D.; Subaşı, I.; Erguder, T.H. Denitrifying Anaerobic Methane Oxidation (DAMO) Cultures: Factors Affecting Their Enrichment, Performance and Integration with Anammox Bacteria. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 295, 113070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulanov, V.L. The Need for the Green Economy Factors in Assessing the Development and Growth of Russian Raw Materials Companies. J. Compr. Bus. Adm. Res. 2024, 1, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Su, Y.; Ding, C.J.; Tian, G.G.; Wu, Z. Unveiling the Green Innovation Paradox: Exploring the Impact of Carbon Emission Reduction on Corporate Green Technology Innovation. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2024, 207, 123562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. ESG Ratings and Climate Transition: An Assessment of the Alignment of E Pillar Scores and Metrics; OECD Business and Finance Policy Papers; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2022; Volume 6, pp. 1–44. [Google Scholar]

- Treepongkaruna, S.; Au Yong, H.H.; Thomsen, S.; Kyaw, K. Greenwashing, Carbon Emission, and ESG. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2024, 33, 8526–8539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baur, D.G.; Todorova, N. Big Oil in the Transition or Green Paradox? A Capital Market Approach. Energy Econ. 2023, 125, 106837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolk, A.; Levy, D.; Pinkse, J. Corporate Responses in an Emerging Climate Regime: The Institutionalization and Commensuration of Carbon Disclosure. Eur. Account. Rev. 2008, 17, 719–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilera, R.V.; Rupp, D.E.; Williams, C.A.; Ganapathi, J. Putting the S Back in Corporate Social Responsibility: A Multilevel Theory of Social Change in Organizations. Acad. Manage. Rev. 2007, 32, 836–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ioannou, I.; Serafeim, G. What Drives Corporate Social Performance? The Role of Nation-Level Institutions. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2012, 43, 834–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamimi, N.; Sebastianelli, R. Transparency among S&P 500 Companies: An Analysis of ESG Disclosure Scores. Manag. Decis. 2017, 55, 1660–1680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, S.; Ma, T. ESG Controversies and Firm Value: Evidence from A-Share Companies in China. Sustainability 2025, 17, 2750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuortimo, K.; Harkonen, J.; Breznik, K. Exploring Corporate Reputation and Crisis Communication. J. Mark. Anal. 2024, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardiana, P.A. Stakeholder Engagement in Sustainability Reporting: Evidence of Reputation Risk Management in Large Australian Companies. Aust. Account. Rev. 2019, 29, 726–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Year | ESG_EW | ESG_CW | ESGC_EW | ESGC_CW | E_EW | E_CW | S_EW | S_CW | G_EW | G_CW |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2019 | 62.63 | 57.23 | 49.99 | 47.41 | 59.58 | 64.14 | 62.47 | 41.17 | 67.39 | 75.73 |

| 2020 | 64.06 | 59.88 | 52.28 | 51.84 | 61.6 | 63.38 | 64.05 | 46.03 | 67.66 | 79.43 |

| 2021 | 64.76 | 61.74 | 54.49 | 51.47 | 63.87 | 69.73 | 63.71 | 47.19 | 67.94 | 75.98 |

| 2022 | 64.71 | 67.58 | 54.01 | 58.61 | 63.85 | 69.83 | 64.66 | 59.27 | 66.04 | 79.09 |

| 2023 | 62.92 | 63.52 | 50.53 | 52.66 | 61.53 | 68.43 | 62.99 | 53.4 | 64.84 | 74.33 |

| Independent Variable | β (Standardized Coefficient) | Standard Error | t-Statistic | p > |t| |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Social Pillar Score | 0.565 | 0.000048 | 11,700 | <0.001 |

| Environmental Pillar Score | 0.390 | 0.000050 | 7823 | <0.001 |

| Governance Pillar Score | 0.236 | 0.000035 | 6813 | <0.001 |

| Statistic | Value |

|---|---|

| Pearson Correlation (r) (Strength/Direction) | 0.781 |

| OLS Slope Coefficient (b) | 0.297 |

| OLS Intercept (a) | −5.385 |

| Coefficient of Determination (R2) | 0.610 |

| Observations (N) | 19 |

| Statistic | Value |

|---|---|

| Pearson Correlation (r) | 0.099 |

| OLS Slope Coefficient (b) | 0.016 |

| OLS Intercept (a) | 1.897 |

| Coefficient of Determination (R2) | 0.010 |

| Observations (N) | 17 |

| Indicator | Pearson Correlation (r) |

|---|---|

| Emissions Score | 0.282 |

| Resource Use Score | 0.222 |

| ESG Score (Overall) | 0.107 |

| Environmental Innovation Score | 0.099 |

| Company Name | ESG Score 2023 | Green Revenues 2024 (%) | Cluster |

|---|---|---|---|

| Saudi Arabian Oil Co | 57.75 | 0.58 | 1 |

| Transportadora de Gas del Sur SA | 56.95 | 0.00 | 1 |

| Guanghui Energy Co Ltd. | 48.71 | 0.00 | 1 |

| Santos Ltd. | 49.27 | 0.00 | 1 |

| Cenovus Energy Inc. | 58.08 | 0.00 | 1 |

| Sociedad Comercial del Plata SA | 11.52 | 0.00 | 1 |

| PetroChina Co Ltd. | 53.61 | 18.96 | 2 |

| Galp Energia SGPS SA | 68.45 | 2.56 | 3 |

| Equinor ASA | 68.87 | 4.94 | 3 |

| Shell PLC | 90.23 | 10.60 | 3 |

| PTT PCL | 77.29 | 3.15 | 3 |

| OMV AG | 83.73 | 0.00 | 4 |

| Vermilion Energy Inc. | 76.83 | 0.00 | 4 |

| Eni SpA | 84.10 | 0.90 | 4 |

| TotalEnergies SE | 83.97 | 1.67 | 4 |

| Petroleo Brasileiro SA Petrobras | 72.47 | 0.72 | 4 |

| Chevron Corp | 65.28 | 0.00 | 4 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Ogrean, C.; Panta, N.D.; Grecu, V. ESG-SDG Nexus: Assessing How Top Integrated Oil and Gas Companies Align Corporate Sustainability Practices with Global Goals. Sustainability 2026, 18, 332. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010332

Ogrean C, Panta ND, Grecu V. ESG-SDG Nexus: Assessing How Top Integrated Oil and Gas Companies Align Corporate Sustainability Practices with Global Goals. Sustainability. 2026; 18(1):332. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010332

Chicago/Turabian StyleOgrean, Claudia, Nancy Diana Panta, and Valentin Grecu. 2026. "ESG-SDG Nexus: Assessing How Top Integrated Oil and Gas Companies Align Corporate Sustainability Practices with Global Goals" Sustainability 18, no. 1: 332. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010332

APA StyleOgrean, C., Panta, N. D., & Grecu, V. (2026). ESG-SDG Nexus: Assessing How Top Integrated Oil and Gas Companies Align Corporate Sustainability Practices with Global Goals. Sustainability, 18(1), 332. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010332