Sustainable Innovation Through University–Industry Collaboration: Exploring the Quality Determinants of AI Patents

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background and Hypothesis Development

2.1. University–Industry Collaboration (UIC) and the Innovation Ecosystem

2.2. Definition and Significance of Patent Quality and the Patent Quality Index (PQI)

2.3. Structural Factors of University–Industry Collaboration

2.3.1. Collaboration Breadth (Partner Diversity)

2.3.2. Collaboration Depth (Relational Continuity)

2.4. Contextual Factors of University–Industry Collaboration

2.4.1. Technological Cognitive Distance (TCD)

2.4.2. Prior Collaboration Experience (Accumulated Ties)

2.5. Corporate R&D Capability (Moderating Factor)

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Conceptual Research Model

3.2. Variable Definition and Measurement

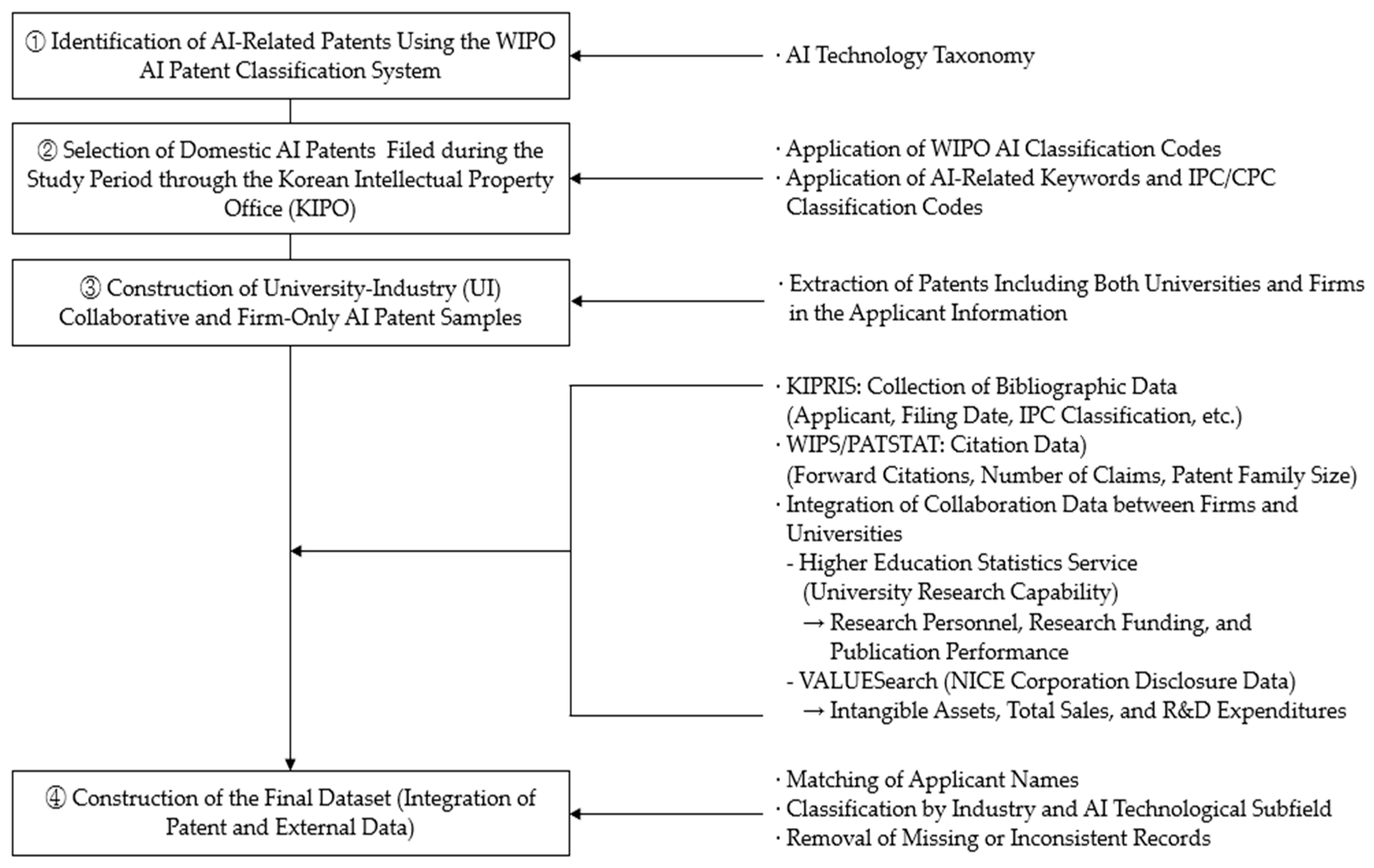

3.3. Data Collection and Sample Construction

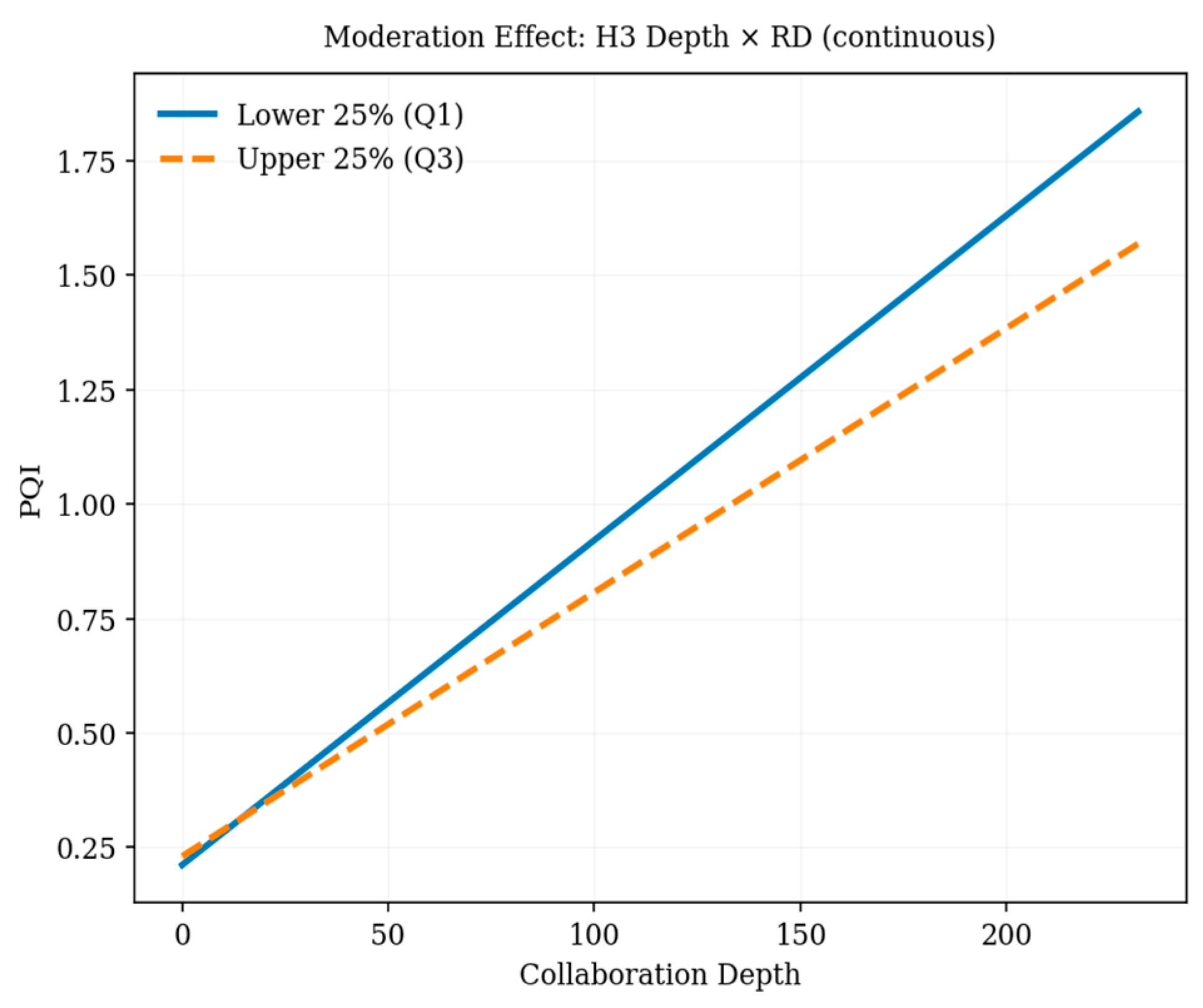

3.4. Analysis Method

3.4.1. Notation

3.4.2. Regression Models

4. Research Results

4.1. Analytical Sample and Descriptive Statistics

4.2. Correlation Analysis and Group Mean Comparison (t-Test)

4.3. Multicollinearity Diagnostics

4.4. Regression Results and Hypothesis Testing

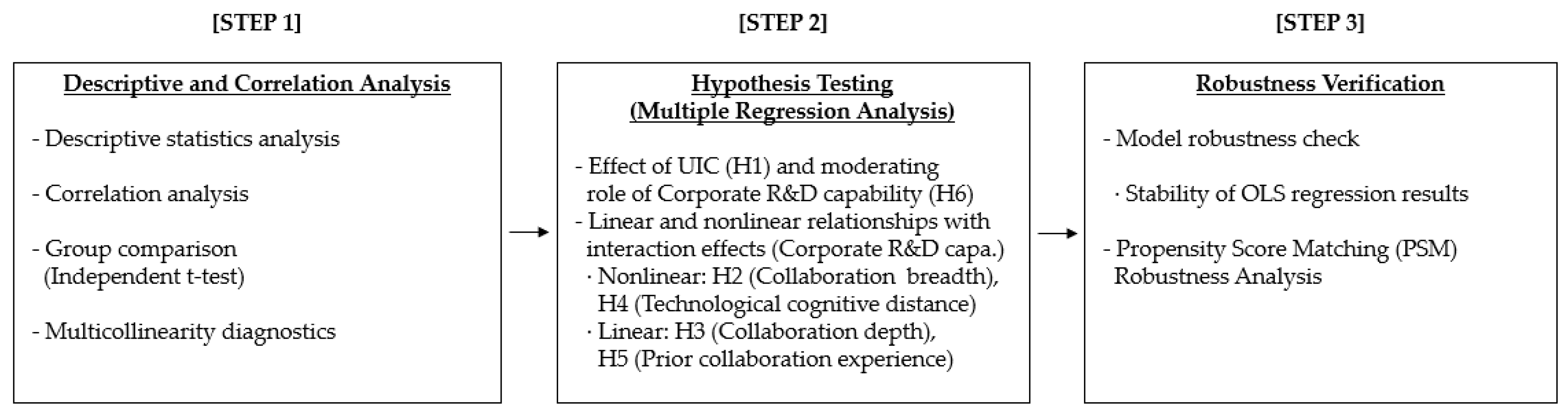

4.4.1. Regression Model 1 (H1, H6)

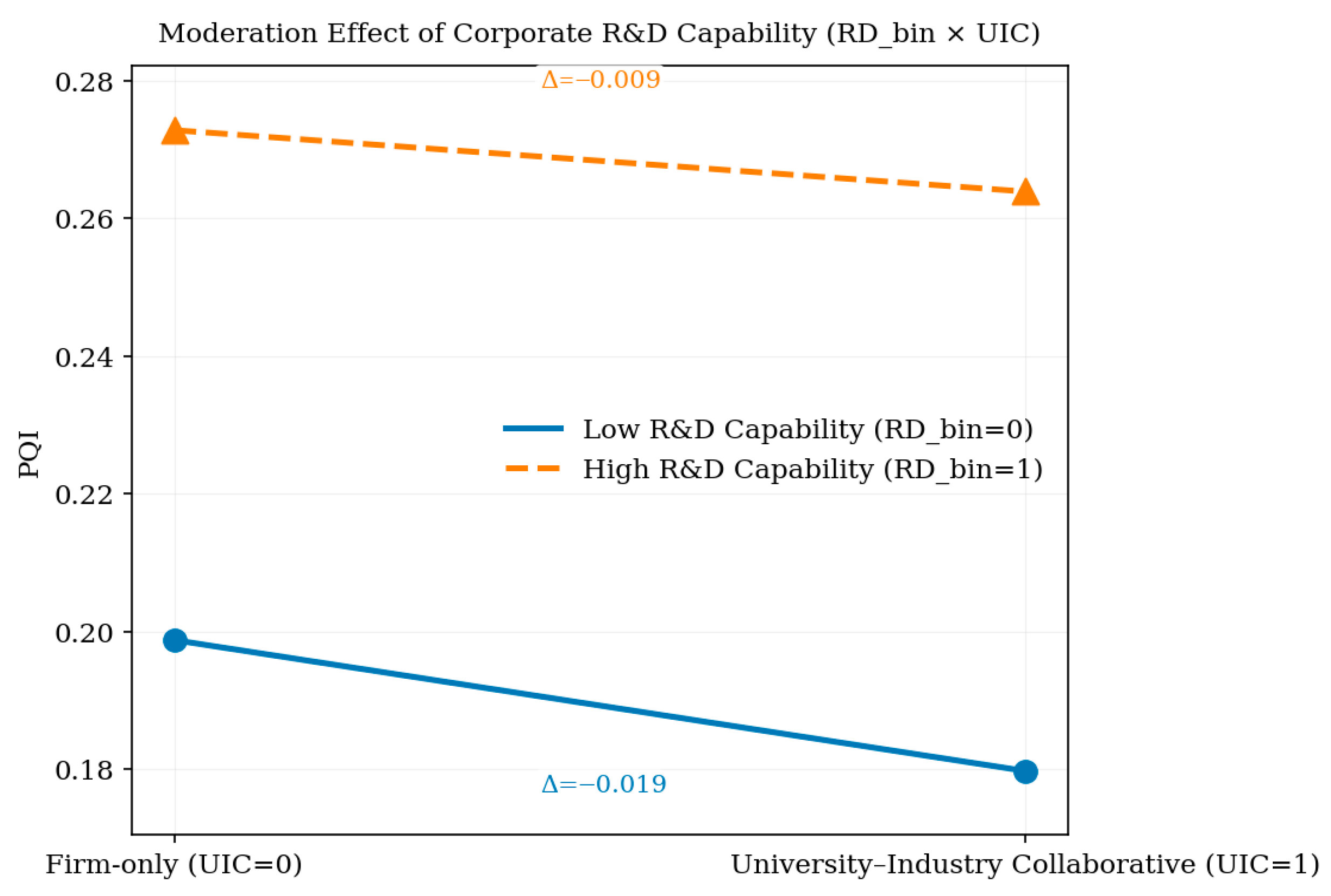

4.4.2. Regression Model 2 (H2–H5)

4.5. Robustness Tests

4.6. Summary of Hypothesis Testing Results

5. Discussion

5.1. Discussion of Key Findings and Theoretical Implications

5.2. Policy and Managerial Implications

5.2.1. Policy Implications

5.2.2. Managerial Implications

6. Conclusions

6.1. Summary and Academic Contributions

6.2. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Application Year | Autonomous Driving | Computer Vision | Deep Learning | General AI | Intelligent Robotics | Machine Learning | Natural Language Processing | Speech Recognition | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2013 | 140 | 182 | 6 | 664 | 89 | 4 | 20 | 29 | 1134 |

| 2014 | 132 | 149 | 14 | 1182 | 65 | 1 | 23 | 36 | 1602 |

| 2015 | 175 | 115 | 32 | 1621 | 124 | 8 | 20 | 33 | 2128 |

| 2016 | 261 | 197 | 85 | 2086 | 189 | 25 | 35 | 29 | 2907 |

| 2017 | 285 | 177 | 254 | 2291 | 224 | 70 | 66 | 100 | 3467 |

| 2018 | 278 | 273 | 488 | 2843 | 236 | 181 | 84 | 135 | 4518 |

| 2019 | 524 | 390 | 896 | 4146 | 603 | 358 | 147 | 249 | 7313 |

| 2020 | 517 | 499 | 1176 | 7319 | 504 | 415 | 139 | 226 | 10,795 |

| 2021 | 726 | 635 | 1311 | 10,207 | 631 | 499 | 155 | 217 | 14,381 |

| 2022 | 769 | 787 | 1662 | 13,022 | 837 | 539 | 222 | 251 | 18,089 |

| 2023 | 728 | 936 | 1971 | 15,816 | 985 | 584 | 295 | 244 | 21,559 |

| Total | 4535 | 4340 | 7895 | 61,197 | 4487 | 2684 | 1206 | 1549 | 87,893 |

| Application Year | Autonomous Driving | Computer Vision | Deep Learning | General AI | Intelligent Robotics | Machine Learning | Natural Language Processing | Speech Recognition | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2013 | 3 | 15 | 4 | 30 | 3 | 1 | - | - | 56 |

| 2014 | 1 | 7 | 1 | 29 | - | - | 2 | - | 40 |

| 2015 | 2 | 16 | 4 | 54 | 1 | - | 1 | - | 78 |

| 2016 | 7 | 22 | 5 | 51 | 9 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 99 |

| 2017 | 11 | 11 | 15 | 66 | - | 5 | - | 3 | 111 |

| 2018 | 7 | 21 | 50 | 94 | 11 | 7 | 3 | 3 | 196 |

| 2019 | 8 | 16 | 75 | 150 | 11 | 21 | 8 | 4 | 293 |

| 2020 | 13 | 19 | 67 | 187 | 17 | 15 | 7 | 2 | 327 |

| 2021 | 15 | 31 | 108 | 264 | 12 | 24 | 8 | 2 | 464 |

| 2022 | 21 | 31 | 126 | 353 | 12 | 71 | 6 | 5 | 625 |

| 2023 | 18 | 36 | 124 | 361 | 26 | 23 | 4 | 8 | 600 |

| Total | 106 | 225 | 579 | 1639 | 102 | 168 | 41 | 29 | 2889 |

| Application Year | Agriculture/Food | Biotechnology/Medical | Chemicals/Materials | Construction/Infrastructure | Electrical/Electronics | ICT | Machinery/Manufacturing | Services/Finance | Energy/Environment | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2013 | 13 | 53 | 12 | 7 | 298 | 389 | 294 | 43 | 25 | 1134 |

| 2014 | 19 | 72 | 18 | 6 | 548 | 527 | 302 | 57 | 53 | 1602 |

| 2015 | 18 | 99 | 25 | 8 | 731 | 628 | 433 | 119 | 67 | 2128 |

| 2016 | 45 | 122 | 35 | 20 | 975 | 801 | 642 | 169 | 98 | 2907 |

| 2017 | 78 | 196 | 44 | 19 | 922 | 1074 | 720 | 315 | 99 | 3467 |

| 2018 | 89 | 382 | 48 | 24 | 1069 | 1483 | 807 | 519 | 97 | 4518 |

| 2019 | 118 | 514 | 56 | 39 | 1584 | 2362 | 1546 | 987 | 107 | 7313 |

| 2020 | 213 | 923 | 82 | 72 | 2903 | 3213 | 1583 | 1576 | 230 | 10,795 |

| 2021 | 193 | 1278 | 104 | 92 | 3881 | 4218 | 2070 | 2248 | 297 | 14,381 |

| 2022 | 259 | 1627 | 95 | 106 | 4675 | 5216 | 2510 | 3272 | 329 | 18,089 |

| 2023 | 421 | 2067 | 153 | 157 | 5030 | 6597 | 2745 | 3878 | 511 | 21,559 |

| Total | 1466 | 7333 | 672 | 550 | 22,616 | 26,508 | 13,652 | 13,183 | 1913 | 87,893 |

| Application Year | Agriculture/Food | Biotechnology/Medical | Chemicals/Materials | Construction/Infrastructure | Electrical/Electronics | ICT | Machinery/Manufacturing | Services/Finance | Energy/Environment | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2013 | 2 | 8 | 1 | - | 15 | 17 | 11 | 2 | - | 56 |

| 2014 | - | 4 | - | 1 | 11 | 14 | 8 | 2 | - | 40 |

| 2015 | 4 | 12 | - | - | 21 | 28 | 10 | 2 | 1 | 78 |

| 2016 | 5 | 17 | 2 | 1 | 16 | 29 | 28 | 1 | - | 99 |

| 2017 | 5 | 24 | 1 | - | 15 | 31 | 27 | 4 | 4 | 111 |

| 2018 | 1 | 54 | 2 | 1 | 26 | 64 | 31 | 12 | 5 | 196 |

| 2019 | - | 81 | 4 | 3 | 32 | 81 | 48 | 31 | 13 | 293 |

| 2020 | 1 | 91 | 5 | 2 | 37 | 85 | 56 | 34 | 16 | 327 |

| 2021 | 5 | 111 | 7 | 1 | 67 | 128 | 82 | 41 | 22 | 464 |

| 2022 | 4 | 178 | 10 | 1 | 73 | 180 | 112 | 53 | 14 | 625 |

| 2023 | 6 | 169 | 11 | 2 | 78 | 155 | 115 | 53 | 11 | 600 |

| Total | 33 | 749 | 43 | 12 | 391 | 812 | 528 | 235 | 86 | 2889 |

Appendix B

| Variable | B | Std. Error | t | Sig. (p) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 0.301 | 0.040 | 7.460 | 0.000 |

| C(industry_sector) [T. Biotechnology/Medical] | 0.063 | 0.028 | 2.269 | 0.023 |

| C(industry_sector) [T. Chemicals/Materials] | −0.039 | 0.036 | −1.093 | 0.274 |

| C(industry_sector) [T. Construction/Infrastructure] | −0.031 | 0.044 | −0.697 | 0.486 |

| C(industry_sector) [T. Electrical/Electronics] | 0.033 | 0.028 | 1.153 | 0.249 |

| C(industry_sector) [T. ICT] | 0.047 | 0.028 | 1.695 | 0.090 |

| C(industry_sector) [T. Machinery/Manufacturing] | 0.026 | 0.029 | 0.919 | 0.358 |

| C(industry_sector) [T. Services/Finance] | 0.056 | 0.032 | 1.750 | 0.080 |

| C(industry_sector) [T. Energy/Environment] | 0.000 | 0.032 | −0.005 | 0.996 |

| C(ai_subfield) [T. ComputerVision] | −0.028 | 0.022 | −1.264 | 0.206 |

| C(ai_subfield) [T. DeepLearning] | 0.014 | 0.022 | 0.631 | 0.528 |

| C(ai_subfield) [T. GeneralAI] | −0.059 | 0.020 | −3.000 | 0.003 |

| C(ai_subfield) [T. IntelligentRobotics] | −0.054 | 0.024 | −2.210 | 0.027 |

| C(ai_subfield) [T. MachineLearning] | −0.027 | 0.026 | −1.052 | 0.293 |

| C(ai_subfield) [T. NaturalLanguageProcessing] | −0.033 | 0.028 | −1.193 | 0.233 |

| C(ai_subfield) [T. SpeechRecognition] | −0.035 | 0.030 | −1.142 | 0.254 |

| C(application_year) [T.2014] | −0.005 | 0.026 | −0.201 | 0.841 |

| C(application_year) [T.2015] | −0.012 | 0.021 | −0.586 | 0.558 |

| C(application_year) [T.2016] | 0.017 | 0.021 | 0.820 | 0.412 |

| C(application_year) [T.2017] | 0.033 | 0.021 | 1.605 | 0.108 |

| C(application_year) [T.2018] | 0.018 | 0.018 | 0.984 | 0.325 |

| C(application_year) [T.2019] | 0.003 | 0.025 | 0.102 | 0.919 |

| C(application_year) [T.2020] | −0.014 | 0.027 | −0.523 | 0.601 |

| C(application_year) [T.2021] | −0.024 | 0.025 | −0.924 | 0.355 |

| C(application_year) [T.2022] | −0.074 | 0.024 | −3.063 | 0.002 |

| C(application_year) [T.2023] | −0.063 | 0.024 | −2.610 | 0.009 |

| treat_uic | −0.056 | 0.013 | −4.154 | 0.000 |

| firm_RDcap_binary | 0.037 | 0.012 | 3.048 | 0.002 |

| treat_uic:firm_RDcap_binary | 0.037 | 0.017 | 2.252 | 0.024 |

Appendix C

| PQI Specification | UIC (B, Sig.) | Corporate R&D Capability (B, Sig.) | UIC × RD Capability (B, Sig.) | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PQI_minmax (Baseline) | (See Model 1 in Section 4.2) | (See Model 1 in Section 4.2) | (See Model 1 in Section 4.2) | Baseline results |

| Forward citations | –0.030 (p = 0.301) | –0.009 *** (p < 0.001) | 0.001 (p = 0.681) | Direction aligned with baseline; no effect of UIC itself |

| Number of claims | 1.515 *** (p < 0.001) | 0.293 *** (p < 0.001) | - | Stronger technical completeness in UIC patents; pattern consistent |

| Patent-Family Size | –0.435 *** (p < 0.001) | –0.435 *** (p < 0.001) | –0.435 *** (p < 0.001) | RD increases international expansion; UIC shows only a limited effect |

References

- Sylvain, F. OECD Science, Technology and Innovation Outlook 2021: Times of Crisis and Opportunity; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Yoon, J.W.; Oh, S.J. A Study on Artificial Intelligence Innovation Ecosystem in South Korea: A Network Analysis of Industry–University–Government Co-Patents. J. Bus. Res. 2023, 30, 23–45. (In Korean) [Google Scholar]

- Chesbrough, H.W. Open Innovation: The New Imperative for Creating and Profiting from Technology; Harvard Business Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Etzkowitz, H.; Leydesdorff, L. The dynamics of innovation: From National Systems and “Mode 2” to a Triple Helix of university–industry–government relations. Res. Policy 2000, 29, 109–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Cui, H. Impact of university–industry collaborative research with different dimensions on university patent commercialisation. Technol. Anal. Strateg. Manag. 2022, 34, 1235–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baek, S.I.; Lee, H.J.; Kim, H.T. Analysis of Artificial Intelligence’s Technology Innovation and Diffusion Pattern: Focusing on USPTO Patent Data. J. Korea Contents Assoc. 2020, 20, 86–98. (In Korean) [Google Scholar]

- Kwak, H.; Lee, S.W. Competitiveness Analysis for Artificial Intelligence Technology through Patent Analysis. J. Inf. Syst. 2019, 28, 141–158. (In Korean) [Google Scholar]

- Harhoff, D.; Scherer, F.M.; Vopel, K. Citations, family size, opposition and the value of patent rights. Res. Policy 2003, 32, 1343–1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, T.; Leidinger, J. Testing patent value indicators on directly observed patent value—An empirical analysis of Ocean Tomo patent auctions. Res. Policy 2014, 43, 519–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.S.; Qiao, X.; Shin, S.Y.; Kim, G.R.; Oh, S.H. Analysis of Korea’s Artificial Intelligence Competitiveness Based on Patent Data: Focusing on Patent Index and Topic Modeling. Inf. Policy 2022, 29, 43–66. (In Korean) [Google Scholar]

- Henderson, R.; Jaffe, A.B.; Trajtenberg, M. Universities as a source of commercial technology: A detailed analysis of university patenting, 1965–1988. Rev. Econ. Stat. 1998, 80, 119–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belderbos, R.; Cassiman, B.; Faems, D.; Leten, B.; Van Looy, B. Co-ownership of intellectual property: Exploring the value-appropriation and value-creation implications of co-patenting with different partners. Res. Policy 2014, 43, 841–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lechevalier, S.; Ikeda, Y.; Nishimura, J. Investigating collaborative R&D using patent data: The case study of robot technology in Japan. Manag. Decis. Econ. 2011, 32, 305–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Shi, T.T.; Srinivasan, S. The Value of AI Innovations; Working Paper; Harvard Business School: Boston, MA, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, B.K. Patent competitiveness of AI technologies and tech–industry linkages. KERI Insight 2017, 16, 1–32. (In Korean) [Google Scholar]

- Nieto, M.J.; Santamaría, L. The importance of diverse collaborative networks for the novelty of product innovation. Technovation 2007, 27, 367–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perkmann, M.; Walsh, K. University–industry relationships and open innovation: Towards a research agenda. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2007, 9, 259–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundvall, B.-Å. National Systems of Innovation: Towards a Theory of Innovation and Interactive Learning; Pinter: London, UK, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson, R.R. National Innovation Systems: A Comparative Analysis; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Cho, I.G. A study on a multi-dimensional national technological-level evaluation on artificial intelligence technology case. In Proceedings of the Korea Contents Association Conference, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2 November 2018; pp. 89–90. (In Korean). [Google Scholar]

- Gassmann, O.; Enkel, E. Towards a Theory of Open Innovation: Three Core Process Archetypes. In Proceedings of the R&D Management Conference (RADMA) 2004, Lisbon, Portugal, 7–9 July 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Perkmann, M.; Tartari, V.; McKelvey, M.; Autio, E.; Broström, A.; D’Este, P.; Fini, R.; Geuna, A.; Grimaldi, R.; Hughes, A.; et al. Academic engagement and commercialisation: A review of the literature on university–industry relations. Res. Policy 2013, 42, 423–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etzkowitz, H. The Triple Helix: University–Industry–Government Innovation in Action; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Tennenhouse, D. Intel’s open collaborative model of industry–university research. Res. Technol. Manag. 2004, 47, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, I.Y.; Lee, S.J.; Lee, S.Y. An Empirical Study on the Relationship between the Capabilities and Sales Growth of Research-based Spin-off Companies. J. Technol. Innov. 2018, 21, 1445–1473. (In Korean) [Google Scholar]

- Park, S.G.; Kang, T.W. Analysis on growth of research-based spin-off companies in Innopolis. Innov. Cluster Res. 2024, 14, 1–19. (In Korean) [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.M.; Park, T.Y. Effectiveness of the LINC+ program using panel fixed-effects models. J. Educ. Financ. Econ. 2024, 33, 135–158. (In Korean) [Google Scholar]

- Hwang, K.Y.; Sung, E.H. Institutional factors of universities affecting U–I collaboration. Asia–Pac. J. Converg. Res. Exch. 2023, 9, 527–541. (In Korean) [Google Scholar]

- Ankrah, S.; Omar, A.-T. Universities–industry collaboration: A systematic review. Scand. J. Manag. 2015, 31, 387–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.W.; Leydesdorff, L. Longitudinal trends in networks of university–industry–government relations in South Korea: The role of programmatic incentives. Res. Policy 2010, 39, 640–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choe, H.; Lee, D.H. The structure and change of the research collaboration network in Korea (2000–2011): Network analysis of joint patents. Scientometrics 2017, 111, 917–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampat, B.N.; Mowery, D.C.; Ziedonis, A.A. Changes in university patent quality after the Bayh–Dole act: A re-examination. Int. J. Ind. Organ. 2003, 21, 1371–1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanjouw, J.O.; Schankerman, M. Patent quality and research productivity: Measuring innovation with multiple indicators. Econ. J. 2004, 114, 441–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, J.; Kwon, O.J.; Kim, W.J.; Noh, K.R.; Jeong, E.S. Strategic Partners—A Practical Guide to Patent Indicators; Korea Institute of Science and Technology Information (KISTI): Daejeon, Republic of Korea, 2006. (In Korean) [Google Scholar]

- Trajtenberg, M. A penny for your quotes: Patent citations and the value of innovations. RAND J. Econ. 1990, 21, 172–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaffe, A.B. Technological Opportunity and Spillovers of R&D: Evidence from Firms’ Patents, Profits and Market Value; National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Von Wartburg, I.; Teichert, T.; Rost, K. Inventive progress measured by multi-stage patent citation analysis. Res. Policy 2005, 34, 1591–1607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guellec, D.; de La Potterie, B.V.P. The Economics of the European Patent System: IP Policy for Innovation and Competition; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Tsay, M.-Y.; Liu, Z.-W. Analysis of the patent cooperation network in global artificial intelligence technologies based on the assignees. World Patent Inf. 2020, 63, 102000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerner, J. The importance of patent scope: An empirical analysis. RAND J. Econ. 1994, 25, 319–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, I.H.; Park, S.J.; Jung, C.S.; Park, S.K. Technology IP Stats: Analyses of AI Patent Activities; Korea Institute of Intellectual Property: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2023. (In Korean) [Google Scholar]

- Yavuz, M.S.; Çalik, H. AI and ML patent intensity and firm performance: A machine-learning-based lagged analysis. Eur. Res. Manag. Bus. Econ. 2025, 31, 100291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sapsalis, E.; van Pottelsberghe, B.; Veugelers, R. Academic vs. industry patenting: An in-depth analysis of what determines patent value. Res. Policy 2006, 35, 1631–1645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.-H.; Lee, Y.-G. Factors of collaboration affecting the performance of alternative energy patents in South Korea from 2010 to 2017. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briggs, K. Co-owner relationships conducive to high quality joint patents. Res. Policy 2015, 44, 1566–1573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacchiocchi, E.; Montobbio, F. Knowledge diffusion from university and public research: A comparison between US, Japan and Europe using patent citations. J. Technol. Transf. 2009, 34, 169–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joo, S.H. Factors Influencing Technology Commercialization of Korean Universities’ Patents. J. Technol. Innov. 2020, 23, 1183–1201. (In Korean) [Google Scholar]

- Park, S.Y.; Choi, Y.J.; Lee, S.J. Investigating the Characteristics of Academia-Industrial Cooperation-Based Patents for Their Long-Term Use. J. Korea Acad.–Ind. Coop. Soc. 2021, 22, 568–578. (In Korean) [Google Scholar]

- Laursen, K.; Salter, A. Open for innovation: The role of openness in explaining innovation performance among UK manufacturing firms. Strateg. Manag. J. 2006, 27, 131–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulati, R.; Gargiulo, M. Where do interorganizational networks come from? Am. J. Sociol. 1999, 104, 1439–1493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uzzi, B. Social structure and competition in interfirm networks. Adm. Sci. Q. 1997, 42, 37–69. [Google Scholar]

- Dahlander, L.; Gann, D.M. How open is innovation? Res. Policy 2010, 39, 699–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phelps, C.; Heidl, R.; Wadhwa, A. Knowledge, networks, and knowledge networks: A review and research agenda. J. Manag. 2012, 38, 1115–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Zhao, Y.; Feng, J. University–Industry technology transfer: Empirical findings from Chinese industrial firms. Sustainability 2022, 14, 9582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, W.; Dietz, J. R&D cooperation and innovation activities of firms—Evidence for the German manufacturing industry. Res. Policy 2004, 33, 209–223. [Google Scholar]

- Granovetter, M. Economic action and social structure: The problem of embeddedness. Am. J. Sociol. 1985, 91, 481–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulati, R. Does familiarity breed trust? The implications of repeated ties for contractual choice in alliances. Acad. Manag. J. 1995, 38, 85–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruneel, J.; d’Este, P.; Salter, A. Investigating the factors that diminish the barriers to university–industry collaboration. Res. Policy 2010, 39, 858–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nahapiet, J.; Ghoshal, S. Social capital, intellectual capital, and the organizational advantage. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1998, 23, 242–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kale, P.; Singh, H.; Perlmutter, H. Learning and protection of proprietary assets in strategic alliances: Building relational capital. Strateg. Manag. J. 2000, 21, 217–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petruzzelli, A.M. The impact of technological relatedness, prior ties, and geographical distance on university–industry collaborations: A joint-patent analysis. Technovation 2011, 31, 309–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoang, H.; Rothaermel, F.T. The effect of general and partner-specific alliance experience on joint R&D project performance. Acad. Manag. J. 2005, 48, 332–345. [Google Scholar]

- Inoue, H.; Liu, Y.-Y. Revealing the intricate effect of collaboration on innovation. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0121973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagedoorn, J. Sharing intellectual property rights—An exploratory study of joint patenting amongst companies. Ind. Corp. Change 2003, 12, 1035–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dosi, G. Technological paradigms and technological trajectories: A suggested interpretation of the determinants and directions of technical change. Res. Policy 1982, 11, 147–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veugelers, R.; Cassiman, B. R&D cooperation between firms and universities: Some empirical evidence from Belgian manufacturing. Int. J. Ind. Organ. 2005, 23, 355–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bu, F.; Tian, X.; Sun, L.; Zhang, M.; Xu, Y.; Guo, Q. Research on the Impact of University–Industry Collaboration on Green Innovation of Logistics Enterprises in China. Sustainability 2025, 17, 5068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santoro, M.D.; Chakrabarti, A.K. Firm size and technology centrality in industry–university interactions. Res. Policy 2002, 31, 1163–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malerba, F. Sectoral systems of innovation and production. Res. Policy 2002, 31, 247–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nooteboom, B. Interfirm Alliances: International Analysis and Design; Routledge: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Boschma, R. Proximity and innovation: A critical assessment. Reg. Stud. 2005, 39, 61–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilsing, V.; Nooteboom, B.; Vanhaverbeke, W.; Duysters, G.; Van Den Oord, A. Network embeddedness and the exploration of novel technologies: Technological distance, betweenness centrality and density. Res. Policy 2008, 37, 1717–1731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parkhe, A. Strategic alliance structuring: A game theoretic and transaction cost examination of interfirm cooperation. Acad. Manag. J. 1993, 36, 794–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reagans, R.; McEvily, B. Network structure and knowledge transfer: The effects of cohesion and range. Adm. Sci. Q. 2003, 48, 240–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czarnitzki, D.; Glänzel, W.; Hussinger, K. Patent and publication activities of German professors: An empirical assessment of their co-activity. Res. Eval. 2007, 16, 311–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO). WIPO Technology Trends 2023: Artificial Intelligence and Frontier Technologies; WIPO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023; Available online: https://www.wipo.int/tech_trends/en/artificial_intelligence/ (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- Cohen, W.M.; Levinthal, D.A. Absorptive capacity: A new perspective on learning and innovation. Adm. Sci. Q. 1990, 35, 128–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabrizio, K.R. University patenting and the pace of industrial innovation. Ind. Corp. Change 2007, 16, 505–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassiman, B.; Veugelers, R. In search of complementarity in innovation strategy: Internal R&D and external knowledge acquisition. Manag. Sci. 2006, 52, 68–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahra, S.A.; George, G. Absorptive capacity: A review, reconceptualization, and extension. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2002, 27, 185–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Park, S.; Lee, J. Exploring potential R&D collaboration partners using embedding of patent graph. Sustainability 2023, 15, 14724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKinnon, J.G.; White, H. Some heteroskedasticity-consistent covariance matrix estimators with improved finite sample properties. J. Econom. 1985, 29, 305–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bercovitz, J.E.; Feldman, M.P. Fishing upstream: Firm innovation strategy and university research alliances. Res. Policy 2007, 36, 930–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Shen, C.; Lam, F.I. Scientific and technological innovation and cooperation in the Greater Bay Area of China: A case study of university patent applications and transformation. Sustainability 2024, 16, 571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansfield, E. Academic research underlying industrial innovations: Sources, characteristics, and financing. Rev. Econ. Stat. 1995, 77, 55–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novillo-Villegas, S.; Tulcanaza-Prieto, A.B.; Chantera, A.X.; Chimbo, C. Exploring a sustainable pathway towards enhancing national innovation capacity from an empirical analysis. Sustainability 2025, 17, 6922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frietsch, R.; Schmoch, U.; Van Looy, B.; Walsh, J.P.; Devroede, R.; Du Plessis, M.; Jung, T.; Meng, Y.; Neuhäusler, P.; Peeters, B. The Value and Indicator Function of Patents; Commission of Experts for Research and Innovation: Berlin, Germany, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, B.H.; Jaffe, A.B.; Trajtenberg, M. Market Value and Patent Citations: A First Look; National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Bekamiri, H.; Hain, D.S.; Jurowetzki, R. Patentsberta: A deep NLP-based hybrid model for patent distance and classification using augmented SBERT. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2024, 206, 123536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tseng, Y.-H.; Lin, C.-J.; Lin, Y.-I. Text mining techniques for patent analysis. Inf. Process. Manag. 2007, 43, 1216–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenhardt, K.M.; Graebner, M.E. Theory building from cases: Opportunities and challenges. Acad. Manag. J. 2007, 50, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research and Applications, 6th ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer-Krahmer, F.; Schmoch, U. Science-based technologies: University–industry interactions in four fields. Res. Policy 1998, 27, 835–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Este, P.; Perkmann, M. Why do academics engage with industry? The entrepreneurial university and individual motivations. J. Technol. Transf. 2011, 36, 316–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Research Variable | Operational Definition | Measurement Method | References | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent Variables | Patent Quality Index (PQI) | Composite indicator representing the technological originality, economic value, and legal strength of a patent. | Arithmetic mean of normalized (min–max) values of forward citations, family size, and number of claims by year and technology. | [1,8,9] |

| - Forward Citations | Total number of forward citations received by each patent after registration. | Extracted from KIPRIS database up to reference date. | [8,11] | |

| - Patent Family Size | Number of jurisdictions in which the same invention is protected. | Calculated from WIPS/PATSTAT data. | [9,33] | |

| - Number of Claims | Total count of independent and dependent claims in specification. | Extracted from KIPRIS DB. | [33] | |

| Independent Variables | University–Industry Collaboration (UI) | Whether a patent is jointly filed by universities and firms. | Dummy variable (joint = 1; firm-only = 0). | [12,16,55] |

| Collaboration Breadth | Diversity of organizations participating in a patent. | Count of unique applicants (universities, firms, others). | [51,57] | |

| Collaboration Depth | Degree of repeated collaboration with the same partner. | Cumulative joint patent applications between identical pairs. | [51,57] | |

| Technological Cognitive Distance (TCD) | Degree of technological similarity between partners. | 1—cosine similarity (0–1) based on IPC/CPC codes. | [70,71,72] | |

| Prior Collaboration Experience | Cumulative history of prior UI collaborations | Number of joint patents prior to observation year. | [58,61] | |

| Moderating Variable | Corporate R&D Capability | Level of R&D capacity of participating firms. | VALUESearch (NICE) data: R&D expenditures, intangible assets, R&D-to-sales ratio. | [79] |

| Control Variables | Industry Sector | Main industrial application domain. | KSIC/WIPO/IPC dummies. | [49] |

| AI Technological Subfield | Specific AI technology category. | Classified using WIPO AI taxonomy. | [1] | |

| University Research Capability | Research infrastructure and performance of university. | Faculty and funding data; derived Z-score. | [12] | |

| Application Year | Year of patent application. | Year dummy (fixed effect). | [12] | |

| Technological Field | Representative IPC Codes | Representative CPC Codes | Remarks and References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Machine Learning | G06N3/08, G06N20/00, G06F15/18, G06N5/02 | G06N3/08, G06N20/00, G06N99/005 | WIPO [76]; Sylvain [1]. Includes G06F15/18 (early but relevant patents since 2010). |

| Deep Learning | G06N3/02, G06N3/04 | G06N3/02, G06N3/0442, G06N3/0464, G06N3/045 | WIPO [76] and recent CPC updates; covers generative AI codes such as autoencoder. |

| Natural Language Processing (NLP) | G06F17/27, G06F17/28 | G06F17/2828, G06F17/30401, G06F17/3043, G06F17/30654, G06F17/30663, G06F17/30666 | Text analysis, machine translation, information retrieval, and knowledge extraction [76]. |

| Speech Recognition and Synthesis | G10L15/00, G10L13/00 | G10L17/00, G10L25/00, G10L99/00 | Primary WIPO codes for AI-based speech and voice technologies [76]. |

| Computer Vision | G06K9/00, G06T7/00, G06T1/20, G06T3/40, G06T9/00 | G06K9/46, G06T3/4046, G06T9/002, G06T2207/20081 | WIPO [76]; includes image recognition, object detection, and video-based AI perception. |

| Autonomous Driving | B60W30/06, B60W30/10, B60W30/12, B60W30/14, B62D15/02, G05D1/00 | B60G2600/1876–1879, B60L2260/32, B60W30/00, B60W10/00 | Vehicle control, navigation, sensor fusion, and autonomous driving systems [76]. |

| Intelligent Robotics | B25J9/00, A61B34/00, G05B13/02 | B25J9/161, G05B2219/33002 | WIPO [76]; includes industrial, service, and medical robots. |

| General AI/Others | G06N, G06T1/40, G06F11/1476 | G06N99/005, Y10S706/00 | WIPO [76]; miscellaneous AI patents classified as “General AI.” |

| Technological Field | Remarks and References |

|---|---|

| General AI | AI, artificial intelligence, “인공지능”, intelligent agent, knowledge base, knowledge system, cognitive computing, inference engine, rule-based reasoning |

| Machine Learning | machine learning, “머신러닝”, ML, supervised learning, unsupervised learning, “지도학습”, “비지도학습”, reinforcement learning, “강화학습”, online learning, transfer learning, classification, clustering, regression |

| Deep Learning | deep learning, “딥러닝”, DL, deep net, neural network, “신경망”, CNN, RNN, DNN, LSTM, ANN, MLP, GAN, autoencoder, transformer, transformer model, transformer encoder, seq2seq, ResNet, GPT, GPT2, GPT3, BERT, BERT model, LM |

| Natural Language Processing (NLP) | natural language processing, “자연어처리”, “자연언어처리”, NLP, LLM, text mining, “텍스트마이닝”, text analytics, document classification, “언어모델”, language model, question answering, named entity recognition, sentiment analysis, “감성분석”, opinion mining, machine translation |

| Computer Vision | computer vision, “컴퓨터비전”, image recognition, “이미지인식”, object detection, “객체탐지”, face recognition, “영상인식”, video analysis |

| Autonomous Driving | autonomous vehicle, autonomous driving, “자율주행”, “자동주행”, self-driving, “무인차량”, path planning, LiDAR |

| Intelligent Robotics | intelligent robot, “지능형로봇”, AI robot, autonomous robot, robot control, “로봇제어”, robot learning |

| Expert Systems | expert system, “전문가시스템”, rule-based reasoning, inference engine |

| Industry Sector | Representative IPC Codes | Description and Scope |

|---|---|---|

| Information and Communication Technology (ICT) | G06 (Computing/Calculation), G11 (Information Storage), H04 (Communication), etc. | Covers the overall ICT field, including software, data processing, communication, and networking technologies. Classified under the Electrical Engineering category in the WIPO taxonomy [76]. Examples include AI algorithms, communication protocols, and data-processing technologies. |

| Biotechnology and Medical (Bio/Healthcare) | A61K/A61P (Pharmaceuticals), C07G/C12N (Biotechnology), etc. | Includes biotechnology and medical technology fields such as pharmaceuticals, biomedical engineering, and healthcare technologies. Examples include new drug development, medical imaging AI, and genetic engineering. Classified under Biotechnology in the WIPO taxonomy [76]. |

| Machinery and Manufacturing | B60/B62 (Automotive/Transportation), F16/F17 (Mechanical Elements), B23 (Machine Tools), etc. | Covers manufacturing and mechanical engineering technologies, including production equipment, automotive mobility, robotics, and industrial machinery. Classified under Mechanical Engineering in the WIPO taxonomy [76]. |

| Electrical and Electronics | H01/H02 (Electric Circuits and Power Systems), H05 (General Electrical Engineering), etc. | Includes electronic and electrical component technologies such as semiconductors, sensors, and control systems. Partially overlaps with ICT-related hardware technologies. Classified under Electrical Engineering in the WIPO taxonomy [76]. |

| Chemicals and Materials | C01–C14 (Chemical Compounds and Processes), C08 (Polymers), C22C (Alloys), etc. | Covers the field of chemical engineering and materials science, including organic chemistry, polymer synthesis, and alloy manufacturing. Classified under Chemistry and Materials Technologies in the WIPO taxonomy [76]. |

| Energy and Environment | Y02 (Climate Change Mitigation Technologies), E21B (Energy Engineering), C02F (Water Treatment), etc. | Includes technologies related to sustainable energy production and environmental management, such as renewable energy, energy storage, and pollution treatment. Classified under Environmental and Energy Technologies in the WIPO taxonomy [76]. |

| Construction and Infrastructure | E01–E04 (Civil Engineering, Soil, Earthwork), B64 (Aviation and Aerospace), etc. | Covers technologies related to construction, infrastructure, transportation, and aerospace engineering. Classified under Construction and Transportation in the WIPO taxonomy [76]. |

| Agriculture and Food | A01 (Agriculture), A23 (Food Technology), etc. | Includes agricultural and food technologies such as smart farming, crop management, and biotechnology for food production. Classified under Food and Agriculture in the WIPO taxonomy [76]. |

| Services and Finance | G06Q (Electronic Commerce/Management), G07 (Checking Devices/Cash Handling), etc. | Covers service and financial technologies, including business management systems, e-commerce, and FinTech innovations such as digital payment automation. Classified under Services and Finance in the WIPO taxonomy [76]. |

| Application Year | Firm-Only Patents | University–Industry Collaborative Patents | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2013 | 1134 | 56 | 1190 |

| 2014 | 1602 | 40 | 1642 |

| 2015 | 2128 | 78 | 2206 |

| 2016 | 2907 | 99 | 3006 |

| 2017 | 3467 | 111 | 3578 |

| 2018 | 4518 | 196 | 4714 |

| 2019 | 7313 | 293 | 7606 |

| 2020 | 10,795 | 327 | 11,122 |

| 2021 | 14,381 | 464 | 14,845 |

| 2022 | 18,089 | 625 | 18,714 |

| 2023 | 21,559 | 600 | 22,159 |

| Total | 87,893 | 2889 | 90,782 |

| Variable | N | Minimum | Maximum | Mean | Std. Deviation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PQI_minmax | 90,782 | 0 | 0.942 | 0.265 | 0.139 |

| Number of claims | 90,782 | 1 | 209 | 11.022 | 6.943 |

| Forward citations | 90,782 | 0 | 50 | 0.474 | 1.353 |

| Patent family size | 90,782 | 1 | 152 | 3.050 | 5.765 |

| Collaboration breadth | 2889 | 2 | 13 | 2.233 | 2.307 |

| Collaboration depth | 2889 | 0 | 232 | 10.557 | 31.038 |

| Prior collaboration experience (firm) | 90,782 | 0 | 658 | 2.734 | 32.198 |

| Prior collaboration experience (university) | 2889 | 0 | 954 | 77.042 | 101.578 |

| Corporate R&D capability | 90,782 | −0.223 | 27.505 | 5.317 | 6.542 |

| Technological cognitive distance | 2889 | 0 | 1 | 0.391 | 0.228 |

| University research capability | 2889 | 0.019 | 4.048 | 0.560 | 0.364 |

| Group | Indicator | N | Mean | Std. Deviation | Std. Error Mean | Skewness | Kurtosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Firm-only patents | PQI_minmax | 87,893 | 0.265 | 0.140 | 0.001 | 0.344 | 0.069 |

| UIC patents | PQI_minmax | 2889 | 0.271 | 0.121 | 0.002 | 0.440 | 0.487 |

| Firm-only patents | fwd_minmax | 87,893 | 0.085 | 0.206 | 0.001 | 2.954 | 8.732 |

| UIC patents | fwd_minmax | 2889 | 0.073 | 0.179 | 0.003 | 3.093 | 10.258 |

| Firm-only patents | clm_minmax | 87,893 | 0.227 | 0.165 | 0.001 | 0.863 | 1.014 |

| UIC patents | clm_minmax | 2889 | 0.271 | 0.177 | 0.003 | 0.890 | 0.938 |

| Firm-only patents | fam_minmax | 87,893 | 0.060 | 0.115 | 0.001 | 4.248 | 25.410 |

| UIC patents | fam_minmax | 2889 | 0.052 | 0.121 | 0.002 | 5.721 | 39.917 |

| Variable | PQI_minmax | Collaboration Breadth | Collaboration Depth | Technological Cognitive Distance | Prior Collaboration (Firm) | Prior Collaboration (University) | Corporate R&D Capability | University Research Capability |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PQI_minmax | 1 | 0.060 ** | 0.028 ** | −0.077 ** | 0.044 ** | 0.015 ** | 0.288 ** | 0.157 ** |

| Collaboration breadth | 0.060 ** | 1 | 0.008 | −0.083 ** | 0.044 ** | 0.084 ** | 0.083 ** | 0.184 ** |

| Collaboration depth | 0.028 ** | 0.008 | 1 | −0.348 ** | 0.617 ** | 0.623 ** | 0.109 ** | −0.289 ** |

| Technological cognitive distance | −0.077 ** | −0.083 ** | −0.348 ** | 1 | −0.115 ** | −0.482 ** | −0.290 ** | −0.452 ** |

| Prior collaboration (firm) | 0.044 ** | 0.044 ** | 0.617 ** | −0.115 ** | 1 | 0.472 ** | 0.099 ** | 0.127 ** |

| Prior collaboration (university) | 0.015 ** | 0.084 ** | 0.623 ** | −0.482 ** | 0.472 ** | 1 | 0.042 ** | 0.515 ** |

| Corporate R&D capability | 0.288 ** | 0.083 ** | 0.109 ** | −0.290 ** | 0.099 ** | 0.042 ** | 1 | 0.253 ** |

| University research capability | 0.157 ** | 0.184 ** | −0.289 ** | −0.452 ** | 0.127 ** | 0.515 ** | 0.253 ** | 1 |

| Variable | Firm-Only Mean | UIC Mean | Mean Difference (UIC−Firm) | t | p-Value | Levene F | Levene Sig. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PQI_minmax | 0.265 | 0.271 | 0.006 | 2.742 | 0.006 | 125.537 | 0.001 |

| fwd_minmax | 0.085 | 0.073 | −0.012 | −3.495 | 0.001 | 36.321 | 0.001 |

| clm_minmax | 0.227 | 0.271 | 0.045 | 13.391 | 0.001 | 13.455 | 0.001 |

| fam_minmax | 0.060 | 0.052 | −0.008 | −3.579 | 0.001 | 22.417 | 0.001 |

| (a) | ||

| Variable | Tolerance | VIF |

| (Constant) | 0.215 | 4.656 |

| UI (University–industry collaboration) | 0.891 | 1.123 |

| Corporate R&D capability | 0.846 | 1.182 |

| University research capability | 0.935 | 1.070 |

| (b) | ||

| Variable | Tolerance | VIF |

| (Constant) | 0.068 | 14.700 |

| Collaboration breadth | 0.954 | 1.049 |

| Collaboration depth | 0.370 | 2.703 |

| Technological cognitive distance | 0.699 | 1.431 |

| Prior collaboration (firm) | 0.512 | 1.955 |

| Prior collaboration (university) | 0.426 | 2.350 |

| Corporate R&D capability | 0.376 | 2.661 |

| University research capability | 0.557 | 1.794 |

| Variable | Model 1–1 (UI only) | Model 1–2 (UI + RD_bin) | Model 1–3 (UI + RD_bin + Interaction) |

|---|---|---|---|

| University–industry collaboration (UI) | 0.001 (p = 0.751) | −0.016 *** (p < 0.001) | −0.019 *** (p < 0.001) |

| Corporate R&D capability (RD_bin) | - | 0.074 *** (p < 0.001) | 0.074 *** (p < 0.001) |

| UI × RD_bin (Interaction term) | - | - | 0.010 ** (p = 0.023) |

| University research capability (Control) | - | 0.016 *** (p < 0.001) | 0.015 *** (p < 0.001) |

| Industry sector (Control) | Included | Included | Included |

| AI subfield (Control) | Included | Included | Included |

| Application year (Control) | Included | Included | Included |

| Constant | 0.288 *** (p < 0.001) | 0.288 *** (p < 0.001) | 0.288 *** (p < 0.001) |

| R2/Adj. R2 | 0.093/0.092 | 0.147/0.147 | 0.147/0.147 |

| F-statistic (Significance) | 361.03 (p < 0.001) | 614.77 (p < 0.001) | 594.09 (p < 0.001) |

| Variable | Model 2–1 (H2: Collaboration Breadth) | Model 2–2 (H3: Collaboration Depth) | Model 2–3 (H4: Technological Cognitive Distance) | Model 2–4 (H5: Prior Collaboration Experience) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Collaboration breadth (Breadth_c) | 0.00446 (p = 0.181) | - | - | - |

| Collaboration breadth2 (Breadth_sq) | −0.00037 (p = 0.151) | - | - | - |

| Breadth × RD | −0.00007 (p = 0.775) | - | - | - |

| Breadth2 × RD | 0.00002 (p = 0.460) | - | - | - |

| Collaboration depth (Depth) | - | 0.00709 *** (p < 0.001) | - | - |

| Depth × RD | - | −0.00026 *** (p < 0.001) | - | - |

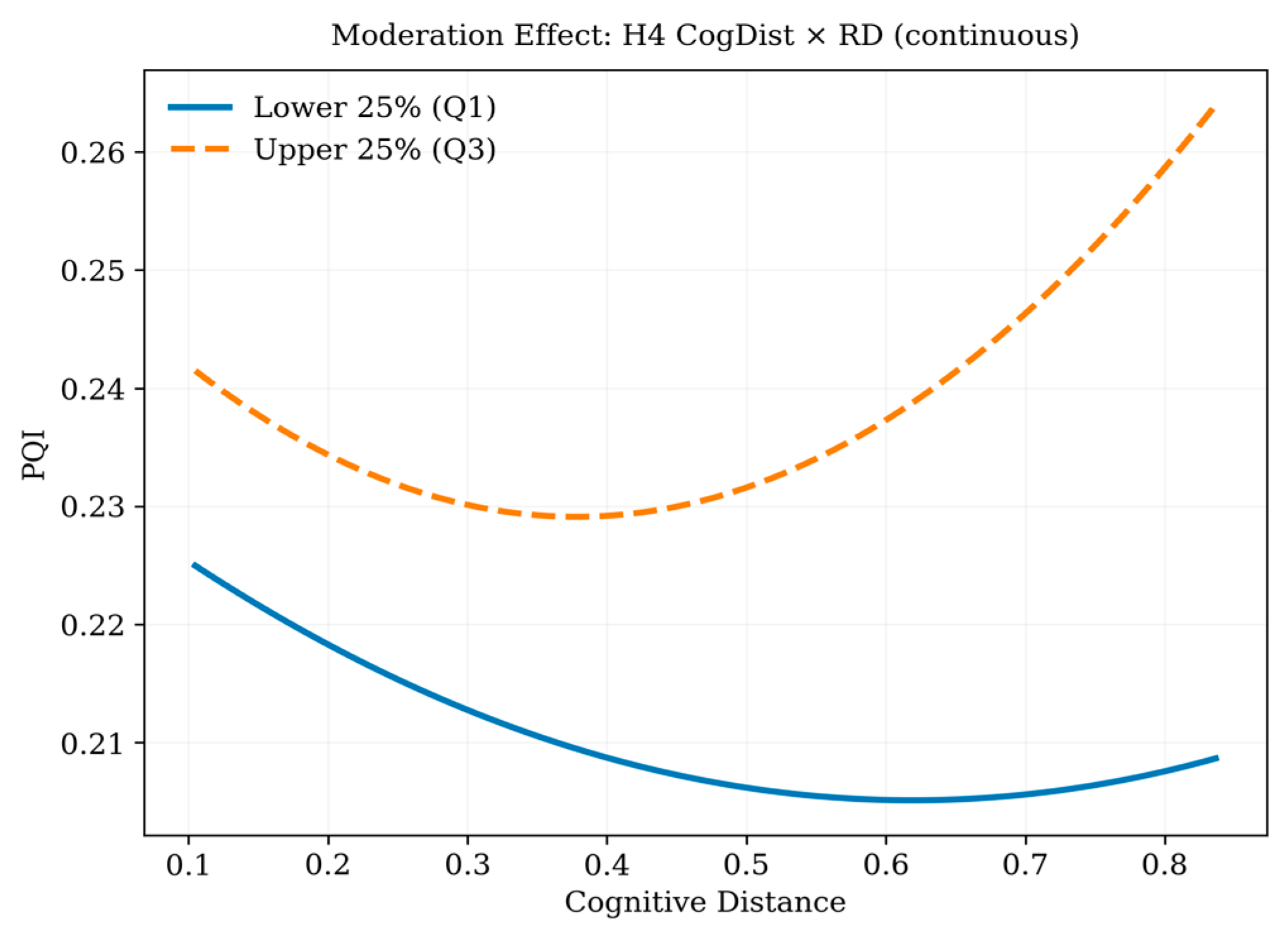

| Technological cognitive distance (CogDist_c) | - | - | −0.09298 ** (p = 0.044) | - |

| Technological cognitive distance2 (CogDist_sq) | - | - | 0.07509 (p = 0.104) | - |

| CogDist × RD | - | - | −0.00646 * (p = 0.099) | - |

| CogDist2 × RD | - | - | 0.01812 *** (p = 0.002) | - |

| Prior collaboration (firm) (Corp ties) | - | - | - | 0.00036 *** (p < 0.001) |

| Prior collaboration (university) (Univ ties) | - | - | - | 0.00012 *** (p < 0.001) |

| Corp ties × RD | - | - | - | −0.00001 *** (p < 0.001) |

| Univ ties × RD | - | - | - | −0.00000 *** (p = 0.002) |

| Corporate R&D capability (RD_cont) | 0.00374 *** (p < 0.001) | 0.00377 *** (p < 0.001) | 0.00377 *** (p < 0.001) | 0.00382 *** (p < 0.001) |

| University research capability (UNI_CAP) | 0.02677 *** (p < 0.001) | 0.02384 *** (p < 0.001) | 0.02584 *** (p < 0.001) | 0.01587 ** (p = 0.047) |

| Constant | 0.21268 *** (p < 0.001) | 0.21601 *** (p < 0.001) | 0.24175 *** (p < 0.001) | 0.24638 *** (p < 0.001) |

| R2/Adj. R2 | 0.189/0.180 | 0.213/0.205 | 0.197/0.188 | 0.237/0.229 |

| F-statistic (Significance) | 25.5 (p < 0.001) | 31.4 (p < 0.001) | 25.8 (p < 0.001) | 34.1 (p < 0.001) |

| (a) | |||||||

| Variable | B | Std. Error | t | Sig. (p) | |||

| University–industry collaboration (UI) | 0.009 | 0.003 | 3.605 | <0.001 *** | |||

| Corporate R&D capability (RD) | 0.004 | 0.000 | 107.699 | <0.001 *** | |||

| UI × RD (Interaction term) | 0.000 | 0.000 | −2.487 | 0.013 ** | |||

| (b) | |||||||

| Variable | B | S.E. | Wald (z2) | Sig. (p) | Exp(B) | ||

| University–industry collaboration (UI) | −0.314 | 0.069 | 20.407 | <0.001 *** | 0.731 | ||

| Corporate R&D capability (RD) | 0.019 | 0.001 | 518.815 | <0.001 *** | 1.019 | ||

| UI × RD (Interaction term) | 0.013 | 0.005 | 6.041 | 0.014 ** | 1.013 | ||

| (c) | |||||||

| Dependent Variable | Variable | B | t | Sig. (p) | Interpretation Summary | ||

| Forward citations | UI | −0.030 | −1.033 | 0.301 | No significant effect of collaboration itself | ||

| RD | −0.009 | −28.528 | <0.001 *** | Higher R&D capability → fewer forward citations ↓ | |||

| UI × RD | 0.001 | 0.412 | 0.681 | No moderating effect | |||

| Number of claims | UI | 1.515 | 11.228 | <0.001 *** | UIC patents contain more claims ↑ | ||

| RD | 0.293 | 156.617 | <0.001 *** | Higher R&D capability → more claims ↑ | |||

| UI × RD | −0.056 | −5.477 | <0.001 *** | R&D capability slightly weakens UIC effect | |||

| Patent family size | UI | −0.435 | −4.806 | <0.001 *** | UIC patents have slightly smaller families ↓ | ||

| RD | 0.060 | 41.798 | <0.001 *** | Higher R&D capability → larger family size ↑ | |||

| UI × RD | −0.034 | −7.583 | <0.001 *** | R&D capability weakens UIC effect | |||

| Hypothesis | Expected Effect | Analytical Model | Key Results | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | UIC patents have significantly higher PQI_minmax than firm-only patents. | Model 1 (Full sample, RD_bin) | UI β = 0.001 (p = 0.751) → Not significant | Rejected (No significant mean effect of collaboration presence) |

| H2 | Collaboration breadth has an inverted U-shaped relationship with PQI_minmax. | Model 2–1 (UIC subsample, RD_cont) | Breadth_c β = 0.00446 (p = 0.181); Breadth_sq β = −0.00037 (p = 0.151) → Both not significant | Rejected (No evidence of inverted U-shape) |

| H3 | Collaboration depth positively affects PQI_minmax. | Model 2–2 (UIC subsample, RD_cont) | Depth β = 0.00709 *** (p < 0.001) positive and significant; Depth × RD_cont β = −0.00026 *** (p < 0.001) negative and significant | Supported (Depth increases PQI_minmax, but effect weakens with higher RD_cont) |

| H4 | Technological cognitive distance has an inverted U-shaped relationship with PQI_minmax. | Model 2–3 (UIC subsample, RD_cont) | CogDist_c β = −0.09298 ** (p = 0.044); CogDist_sq not significant (p = 0.104); CogDist_sq × RD_cont β = 0.01812 *** (p = 0.002) significant | Rejected (Inverted U-shape not supported, but curvilinear moderating effect exists) |

| H5 | Prior collaboration experience increases PQI_minmax. | Model 2–4 (UIC subsample, RD_cont) | Corp ties β = 0.00036 *** (p < 0.001); Univ ties β = 0.00012 *** (p < 0.001) positive and significant; Ties × RD_cont significant negative (p < 0.001–0.002) | Partially supported (* Experience improves PQI_minmax, but effect weakens with higher RD_cont) |

| H6 | The effect of university–industry collaboration is stronger for firms with higher R&D capability. | Model 1–3 (Full sample, RD_bin) | UI × RD_bin β = 0.010 ** (p = 0.023) positive and significant | Supported (Collaboration effect enhanced in high-R&D group) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Choi, D.; Cho, K. Sustainable Innovation Through University–Industry Collaboration: Exploring the Quality Determinants of AI Patents. Sustainability 2026, 18, 333. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010333

Choi D, Cho K. Sustainable Innovation Through University–Industry Collaboration: Exploring the Quality Determinants of AI Patents. Sustainability. 2026; 18(1):333. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010333

Chicago/Turabian StyleChoi, Deungho, and Keuntae Cho. 2026. "Sustainable Innovation Through University–Industry Collaboration: Exploring the Quality Determinants of AI Patents" Sustainability 18, no. 1: 333. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010333

APA StyleChoi, D., & Cho, K. (2026). Sustainable Innovation Through University–Industry Collaboration: Exploring the Quality Determinants of AI Patents. Sustainability, 18(1), 333. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010333