1. Introduction

Over the past few decades, Peru’s economic structure has undergone a profound transformation, characterized by a sustained increase in the share of primary sectors within the country’s external trade. This shift has led to a growing reliance on mineral exports, whose performance is closely tied to international commodity prices [

1]. Within this framework, the evolution of the terms of trade (hereafter ToT)—that is, the ratio between export and import prices—has emerged as a key driver of the country’s macroeconomic dynamics [

2,

3]. However, this dependence has also deepened the structural vulnerability of non-primary sectors such as manufacturing, which often suffer adverse side effects when revenues from mineral exports trigger currency appreciations or prompt a reallocation of productive resources [

4,

5].

The economic literature has identified this situation as a potential case of Dutch disease—a phenomenon widely documented in resource-rich countries, where export booms in the primary sector ultimately weaken the competitiveness and long-term sustainability of the industrial base [

6,

7]. In the Peruvian context, several studies have begun to explore this hypothesis, suggesting that the gains associated with favorable ToT may have uneven—and sometime adverse—effects on sectors such as manufacturing, by reducing their relative share in gross domestic product and discouraging productive investment in higher value-added industries [

8,

9].

From a historical perspective, the evolution of Peru’s manufacturing sector reveals a clear trend of declining participation within the country’s productive structure. According to data from the Central Reserve Bank of Peru, in 1922, manufacturing GDP represented 13.32% of the economy’s total GDP; this share increased over the following decades, reaching a historical peak of 18.52% in 1971, amid an active industrialization agenda.

However, the reversal has been both steady and deep: by the end of 2023, the manufacturing sector’s share had dropped sharply to 11.65%—its lowest level on record, even below that of 1922 [

10]. While this trajectory may partly reflect global patterns of tertiarization, the Peruvian case is distinctive in that the fall in manufacturing has occurred alongside a renewed expansion of the extractive sector. More recent data (1994–2024) show that the share of metallic mining in GDP rose by 29.96%, while the manufacturing sector experienced a relative decline of 30.12%. Within manufacturing, primary resource-based manufacturing fell by 39.83%, and non-primary manufacturing declined by 25.64%. In parallel, the services sector increased its share by 6.5% over the same period [

10].

This dual movement—decline in industry and rise in extractives—suggests a regressive reallocation of resources, rather than a benign shift toward services. Unlike economies where the rise in the service sector reflects technological upgrading or urbanization, in Peru the fall of manufacturing appears increasingly disconnected from gains in productivity or structural transformation. These asymmetric dynamic raises legitimate concerns about long-term development prospects, given that industry often plays a key role in generating formal employment, diversifying exports, and promoting technological learning. Hence, the “declining relevance” of manufacturing is not merely a descriptive term, but a structural warning sign in the context of an economy still marked by commodity dependence and external vulnerability.

In response to this issue, the present study aims to empirically assess the impact of ToT on the structural sustainability of Peru’s manufacturing sector. To this end, an econometric model is applied, linking the manufacturing GDP index to variations in ToT. The model also includes the following control variables: aggregate GDP, private gross fixed investment and the real exchange rate. The goal is to generate quantitative evidence to support policy strategies that enhance industrial resilience and reduce structural reliance on commodity-driven growth.

Unlike approaches that focus on measuring external competitiveness through indicators such as the Revealed Comparative Advantage (RCA) index or the Herfindahl–Hirschman Index (HHI)—tools commonly used to describe market concentration or export specialization in sectoral trade analyses [

11]—this study adopts a structural perspective aimed at explaining the internal economic effects that ToT may exert on the sustainability of the manufacturing base. Rather than merely characterizing the sector’s relative trade position, this research seeks to evaluate whether fluctuations in ToT negatively affect industrial performance, potentially contributing to a regressive reallocation of resources toward primary sectors such as mining.

This analytical perspective allows us to move beyond trade-based metrics and instead examine the underlying structural vulnerability of the manufacturing sector in a country still navigating a path toward productive diversification. In this context, ToT fluctuations are not treated merely as relative price movements in foreign trade, but as exogenous shocks that may distort internal resource allocation. By inducing capital inflows and currency appreciation, improvements in ToT can inadvertently discourage investment in tradable manufacturing activities, thereby amplifying symptoms typically associated with Dutch disease and undermining the foundations of sustainable economic development [

8,

12].

The value of this study lies in its contribution to sectoral sustainability analysis from a quantitative empirical standpoint, acknowledging that industrial resilience depends not only on internal factors such as productivity or technology, but also on external conditions shaped by the global trade environment [

13,

14]. Understanding the link between ToT and manufacturing performance is essential for designing policies that mitigate regressive effects, enhance competitiveness, and ensure more balanced and sustainable long-term growth. Within this framework, the present research offers a substantive contribution by examining the impact of ToT on the sustainability of Peru’s manufacturing sector—an area still underexplored in contemporary literature.

Unlike traditional studies that focus on aggregate outcomes or primary sectors, this research specifically analyzes how external shocks—such as favorable ToT—can erode the industrial base, aligning with the Dutch disease hypothesis. It employs a robust econometric model, based on updated quarterly data (2012–2024), and includes relevant lags to capture delayed effects without overfitting the specification. Beyond the Peruvian case, the findings may also be informative for emerging economies with similar productive structures, where export booms can trigger processes of silent deindustrialization. For example: countries such as Chile, Colombia, and Indonesia show broadly similar patterns of resource dependence and exposure to recurrent commodity cycles, which, to a certain extent, leave them facing comparable risks of weakening their manufacturing base whenever favorable ToT episodes occur. In such contexts, it becomes particularly relevant for policymakers and international development agencies to grasp how these external dynamics unfold, since doing so can inform the design of cooperation strategies and investment initiatives aimed at strengthening productive diversification while cushioning the impact of external shocks.

In that regard, the Peruvian experience offers not only a concrete case for reflection but also a useful point of comparison for understanding the sustainability challenges that resource-dependent economies confront in their efforts to advance the United Nations’ development agenda. The structural dimension explored here resonates with global goals that call for more inclusive industrialization, broader productive diversification, and more responsible use of natural resources—principles that resonate with Sustainable Development Goals 8, 9, and 12. In this light, the study fills a tangible gap in the Peruvian debate—still largely shaped by conventional interpretations—and, at the same time, provides grounded evidence to reconsider sustainable development strategies in countries where external volatility remains a persistent structural concern. Altogether, the argument put forward here reinforces the view that maintaining a dynamic manufacturing sector is not simply a domestic ambition but a foundation for economic resilience and long-term sustainability.

1.1. Literature Review

Peru’s manufacturing sector faces a series of logistical, economic, and structural challenges that threaten its sustainability in an environment increasingly dependent on primary sectors. From a logistical standpoint, the country experiences bottlenecks related to energy costs, limited infrastructure, and deficiencies in intermodal transport—factors that directly undermine the competitiveness of manufacturing industries [

9]. The global reconfiguration of value chains following the COVID-19 pandemic has further exacerbated these constraints, affecting both the supply of imported inputs and limiting opportunities to export value-added products [

15].

Economically, Peru occupies an ambiguous position in international trade: while sectors such as mining have gained ground thanks to improved ToT, the manufacturing sector has seen its share of GDP decline, reflecting a pattern of regressive re-primarization [

16]. This situation is closely linked to the Dutch disease hypothesis, widely documented in commodity-dependent economies [

4,

5,

17]. According to this framework, resource export booms often lead to real exchange rate appreciation, which tends to crowd out manufacturing production—especially in sectors operating with thinner margins and greater sensitivity to price-based competitiveness [

18].

At the structural level, Peru’s industrial sector continues to struggle with low technological adoption, limited productive diversification, and weak integration into global value chains [

9,

13]. These weaknesses are compounded by the significant concentration of public and private investment in extractive sectors, often at the expense of long-term industrial policies. This lack of strategic vision has left the manufacturing sector exposed to the boom-and-bust cycles of international trade, without adequate internal buffers to absorb external shocks [

19].

Likewise, the volatility of ToT has proven to be a significant channel through which external shocks are transmitted, affecting macroeconomic stability and industrial planning [

14,

20]. Regional studies have shown that greater exposure to such volatility is associated with declines in industrial investment, rising urban unemployment, and reduced productive diversification [

21,

22].

From an institutional standpoint, numerous studies have emphasized that weak regulatory frameworks and poor coordination of industrial policies hinder effective responses to the negative impacts of ToT on the national productive structure. The lack of effective countercyclical mechanisms to manage volatile trade-related revenues creates a macroeconomic bias in favor of the primary sector, thereby intensifying the onset of deindustrialization [

23]. This situation underscores the need to rethink regulatory and fiscal frameworks from a structural sustainability perspective, one that positions the manufacturing sector as a central pillar of economic development.

Regarding dynamic impacts, scholars such as [

24,

25] argue that sustained growth requires a continuous process of human capital accumulation, innovation, and productive diversification. However, exposure to volatile ToT tends to discourage such long-term investments in sectors like manufacturing, given the high perceived risk [

26,

27]. This phenomenon has also been observed across Latin America, where the primary-export pattern has persisted despite efforts to promote industrialization through import substitution strategies [

28,

29,

30].

Moreover, the link between sustainability and manufacturing has gained increasing attention in recent research, which underscores the importance of building a resilient industrial base capable of withstanding external, climatic, and geopolitical disruptions [

31,

32]. The sustainability of the sector should not be understood solely in environmental terms, but rather as the capacity to maintain a stable productive trajectory—one that fosters employment, technological innovation, and intersectoral linkages [

3,

13].

In this context, it is relevant to apply econometric approaches that allow for an empirical assessment of whether ToT pose a threat to the sustainability of Peru’s manufacturing sector. As suggested by previous studies conducted in China, India, and the United States, long-term analyses of the relationship between ToT and sectoral growth provide concrete evidence of contractionary dynamics that demand urgent attention [

33,

34,

35]. This research aims to contribute to that discussion by incorporating a comprehensive perspective that integrates economic, industrial, and macrostructural dimensions of sustainability.

1.2. Theortical Framework

This section develops the analytical framework that informs the empirical model presented in the following section. Drawing from structuralist and endogenous growth theories, it outlines the mechanisms through which external shocks—particularly those related to terms of trade (ToT)—may affect the structural sustainability of the manufacturing sector in resource-dependent economies. In what follows, we review key theoretical contributions that support the selection of variables and the expected direction of their effects within the empirical model.

Economic theory offers multiple frameworks to understand how external shocks—particularly those related to ToT—affect the structure and performance of productive sectors in developing economies. Since the classical contributions of [

28,

29], scholars have pointed out that the deterioration of ToT exerts regressive effects on the industrial base, reinforcing export dependence on raw materials and weakening the capacity for productive accumulation in higher value-added sectors.

In line with this structuralist tradition, contemporary approaches have emerged that integrate macroeconomic, institutional, and technological variables to explain the vulnerability of certain sectors to external volatility [

2,

36]. Recent literature has also linked these dynamics to phenomena such as Dutch disease, which arises when a ToT boom triggers an appreciation of the real exchange rate and redirects resources from manufacturing to extractive sectors, thereby undermining the long-term sustainability of industrial development [

17,

18].

Authors such as [

8,

37] have argued that industrial competitiveness cannot be analyzed solely in terms of relative prices, but must also incorporate structural indicators such as productivity, intersectoral linkages, and macroeconomic stability. Along the same lines, [

24] emphasized that sustained growth requires the accumulation of both human and physical capital—elements that tend to weaken when public resources are diverted into inefficient subsidies during favorable ToT cycles.

Furthermore, drawing on endogenous growth theory, it has been argued that the impact of ToT on industry depends on the institutional framework, the design of industrial policies, and the degree of integration of the manufacturing sector into global value chains [

25,

38,

39]. This is particularly relevant in countries like Peru, where the industrial sector has shown a declining share of GDP over the past two decades—partly due to its limited resilience to external shocks and the lack of investment in technological infrastructure and innovation [

40,

41].

The relationship between ToT and the sustainability of the manufacturing sector has gained increasing attention in recent empirical literature. Several studies have shown that countries with commodity-export-oriented economies tend to exhibit greater structural vulnerability, especially when export booms fail to translate into sustainable industrialization processes [

14,

26,

42]. In this context, sustainability entails not only economic efficiency, but also productive resilience, export base diversification, and the capacity to generate long-term value added [

3,

32].

The Peruvian case is illustrative of this phenomenon. Recent studies indicate that during periods of improved ToT, the manufacturing sector has not experienced sustained growth and has even lost relative share to primary sectors [

40,

43]. This pattern aligns with the Dutch disease hypothesis, which posits that an improvement in export prices may lead to inefficient resource reallocation, a decline in industrial competitiveness, and structural dependence on low value-added goods [

5,

44].

From a methodological perspective, the use of econometric models allows for a more precise estimation of the marginal impact of ToT on manufacturing GDP, while controlling for other relevant variables such as private investment, the real exchange rate, and global economic growth [

45,

46]. This approach is essential for evaluating not only the direction of the effect, but also its statistical significance and temporal persistence. Accordingly, the model employed in this study accounts for the lagged effect of the real exchange rate—critical variable in the transmission of external cycles to domestic manufacturing GDP.

The literature also indicates that the effects of ToT are neither uniform across countries nor consistent across industrial sub-sectors, as they depend on structural composition, trade openness, and the institutional ability to mitigate external shocks [

22,

23,

47]. Dutch disease, regarded as a structural process, operates through several interconnected mechanisms—typically summarized as the demand, investment, and exchange rate channels. Improvements in ToT tend to raise national income and internal absorption, leading to a reallocation of resources towards non-tradable activities. At the same time, capital flows stimulated by external booms often concentrate in primary or high-return ventures, limiting productive investment in manufacturing. The appreciation of the real exchange rate further amplifies these pressures by making industrial exports more expensive and imports relatively cheaper, eroding competitiveness and reinforcing structural imbalances [

4,

17,

45,

46].

However, the purpose of the present model is not to quantify each of these channels individually, but to isolate the net structural effect of ToT on the performance of the manufacturing sector. For this reason, the econometric specification includes control variables consistent with macroeconomic theory—real GDP, acting as a proxy for domestic demand; private gross fixed investment, representing the investment channel; and the real exchange rate, capturing relative price dynamics. Their inclusion serves to control for indirect influences and to avoid specification bias, rather than to estimate their separate causal impacts. In addition, a COVID-19 dummy variable captures the extraordinary disruption of 2020, allowing for a clearer assessment of how ToT influence manufacturing GDP within the Peruvian context.

2. Methodology

This study aims to empirically analyze the effect of ToT on the sustainability of Peru’s manufacturing sector, assessing whether there is evidence of a potential manifestation of Dutch disease that could compromise long-term industrial growth. To achieve this, a quantitative approach grounded in applied macroeconomic analysis is employed, using quarterly data and an Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) regression model with robust HAC (Newey–West) standard errors. The inclusion of this robustness correction has been necessary due to the presence of an exceptional shock, such as that caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. This methodological refinement is a precautionary measure commonly employed in empirical macroeconomic research. It is suitable for quarterly data and does not modify the estimated coefficients, although it does adjust the p-values, thereby making the statistical inference more reliable.

Although more complex dynamic models are common in macroeconomic literature, the OLS technique remains suitable for studies focused on long-run structural associations and long-run average effects—particularly in settings with limited time-series observations or when parsimony is required. This modeling choice aligns with recent empirical applications of OLS in macroeconomic studies, including analyses of the impact of macro indicators on investment in manufacturing companies in China [

48]; the effects of traditional exports on Peru’s economic growth [

49], and inclusive economic growth and international trade in Peru [

50].

Unlike descriptive approaches based on trade concentration indices such as the HHI or RCA [

11], this study adopts an explanatory strategy that isolates the structural impact of ToT on real manufacturing GDP. Rather than examining external competitiveness per se, the objective is to determine whether the relative increase in primary export prices—as reflected in ToT—generates contractionary effects on the industrial sector, as predicted by classical Dutch disease hypotheses [

5,

17,

18,

51,

52].

The model is estimated for the period 2012–2024 using quarterly data, with the dependent variable defined as an index of real GDP for the manufacturing sector, adjusted to 2007 constant prices. The explanatory variables include: the quarterly variation in ToT, aggregate real GDP, and private gross fixed investment—all adjusted to 2007 constant prices. These additional variables are included as macroeconomic controls, not as variables of primary analytical interest, in order to isolate the net ToT–manufacturing GDP relationship. The model also incorporates the real exchange rate, which represents one of the main mechanisms through which external shocks influence the domestic economy. Within the model, aggregate GDP acts as a proxy for domestic demand, based on the macroeconomic identity (production = income = expenditure). In parallel, private gross fixed investment reflects the dynamics of productive capital formation that indirectly influence industrial output and signal how domestic investment reallocates in response to external changes within the Peruvian economy.

To specify the model, the stationarity of the variables was verified using unit root tests. To strengthen the validity of the diagnosis regarding the order of integration, two tests were applied: the Augmented Dickey-Fuller (ADF) test and the Dickey-Fuller test with Generalized Least Squares. This methodological choice reflects a conservative approach, common in macroeconomic time series analysis, and ensures that the results regarding the presence or absence of unit roots do not depend on a single specification.

The results indicated that the series corresponding to the manufacturing GDP index and private gross fixed investment are stationary in levels, while the remaining variables exhibit unit roots and were thus used in first differences to ensure the statistical validity of the model. This verification allowed for the specification of the appropriate functional form of the econometric equation, thereby avoiding the risk of spurious regression.

With regard to the temporal specification of the model, a lag of four quarters is applied to the real exchange rate. This choice is grounded initially in theoretical insights, such as the overshooting hypothesis, which suggests that exchange rate shocks affect the real economy with delay due to nominal rigidities and expectation formation processes [

53]. Likewise, given the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the economy, a dummy variable was incorporated into the model to absorb the shock in 2020, starting from the second quarter when the abrupt economic downturn occurred. As in other studies, this allows the health shock to be isolated and the consistency of the model to be preserved [

54].

Given the structural changes in the Peruvian economy and the evolution of transmission mechanisms, the final lag structure was not determined solely by theoretical priors. Instead, an empirical lag selection process was conducted using iterative regressions with alternative lag configurations. These were evaluated using information criteria such as Akaike Information Criterion (AIC), the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC), and the Hannan–Quinn Criterion (HQIC), alongside diagnostic checks focused on expected coefficient signs, statistical significance, and the adjusted R-squared of the model. This dual approach ensures that the selected lag specifications are both theoretically plausible and empirically robust.

The specification adopted in this study is grounded in both applied empirical research and established theoretical insights concerning the macroeconomic effects of terms of trade—particularly in resource-dependent economies like Peru. The inclusion of control variables such as real GDP, private investment, the real exchange rate, and the COVID-19 dummy follows a control-based strategy intended to prevent specification bias and to isolate the long-term structural effect of ToT on the manufacturing sector [

2,

3,

14,

28,

29,

44,

54,

55].

The choice of the time horizon responds to both technical and structural considerations. First, the selected period is sufficiently long to identify persistent patterns over time, allowing the model to capture medium- and long-term structural effects on manufacturing dynamics. Second, starting in 2012, the Central Reserve Bank of Peru consolidated homogeneous statistical series with a 2007 = 100 base, which ensures methodological consistency in the measurement of the key variables used in the econometric model.

Moreover, the quarterly frequency allows for greater temporal variability and enhances the model’s explanatory power, while reducing the risk of biased estimates caused by seasonality or short-term disturbances. Nonetheless, to further control for such effects, the variables manufacturing GDP, real GDP, and private gross fixed investment were seasonally adjusted using Minitab 21 software through multiplicative decomposition, considering that seasonal variations in manufacturing GDP, real GDP, and private gross fixed investment tend to be proportional to the level of economic activity. This approach is standard in macroeconomic analyses involving variables expressed in indices or real values.

The period under study also covers distinct phases of the economic cycle, including the post-commodity boom slowdown, the contractionary effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, and the subsequent recovery amid inflationary and external pressures. This coverage is particularly relevant for examining how ToT influence the sustainability of the manufacturing sector, taking into account both favorable and adverse scenarios.

In order to ensure the statistical consistency of the econometric model, classical diagnostic tests were applied to verify the fundamental assumptions of Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) estimators. First, the presence of heteroskedasticity was assessed using the Breusch–Pagan test, which evaluates whether the residuals exhibit constant variance. Second, residual autocorrelation up to the fourth order was examined using the LM serial correlation test, which is particularly recommended for quarterly time series, where persistent effects are more likely to occur.

In addition, structural parameter stability was tested using the Harvey–Collier CUSUM test, and the normality of residuals was assessed through a Chi-square-based goodness-of-fit test for normal distribution. The RESET was also included in order to determine the correct functional specification of the regression model. These procedures were applied to evaluate the robustness of the model against structural bias, non-spherical errors, and specification problems [

45,

46]. This methodological approach follows a quantitative, explanatory, and longitudinal perspective aimed at identifying structural patterns that constrain the sustainability of the manufacturing sector in developing economies.

As previously noted, the estimation is performed using Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) with robust HAC (Newey–West) standard errors, a common practice in applied macroeconomic research to enhance the reliability of statistical inference [

56]. This approach is adopted as a preventive refinement rather than as a response to detected misspecification, in line with standard practice when dealing with limited samples or potential volatility caused by extraordinary events.

This technique refines the variance–covariance matrix without altering the estimated coefficients, thus improving the precision of hypothesis testing and confidence intervals. Its flexibility allows it to accommodate diverse patterns of heteroskedasticity or mild serial correlation that may arise in quarterly datasets, particularly under temporary disturbances such as those caused by the COVID-19 shock [

56,

57]. By incorporating this correction, the model gains robustness and interpretative stability, ensuring that the estimated relationships reflect structural rather than transitory effects.

Based on the theoretical and methodological foundations outlined above and the results of the stationarity tests, the following econometric specification is proposed:

where

Mt represents the index of real gross domestic product in the manufacturing sector, adjusted to constant prices (2007 = 100). This is the dependent variable of the model and serves as the main indicator for evaluating the performance of the manufacturing sector. Δ

Tt denotes the quarterly variation in the ToT index (2007 = 100), which measures the relative change between the country’s export and import prices. This variable captures the impact of external shocks on the domestic economy, particularly those associated with trade booms or downturns in international markets. Δ

GDPt corresponds to the quarterly variation in the aggregate real GDP index (2007 = 100) and acts as a general macroeconomic control for the overall business cycle.

PGFIt indicates the level of private gross fixed investment, also expressed in real terms (2007 = 100), and reflects the country’s capacity for productive capital formation.

ΔREt−4 represents the variation in the real exchange rate with a four-quarter lag, included to capture delayed effects of external competitiveness on domestic industry. The inclusion of the variable

DCOVID—a dummy designed to absorb the impact caused by the mandatory lockdown during the coronavirus pandemic in 2020 from the second quarter until the end of the year—is justified to account for the exceptional distortion generated during that period.

εt is the random error term that captures unobserved factors potentially affecting manufacturing performance in each period.

This formulation seeks to capture the short- and medium-term effects of the main external and internal macroeconomic variables on the evolution of manufacturing GDP. The ToT coefficient (β1) is the core parameter of interest, as it quantifies the structural response of the industrial sector to external shocks once the effects of control variables have been netted out. The use of lags for the exchange rate reflects their typically delayed behavior in transmitting effects to industrial activity, while the inclusion of investment and aggregate GDP responds to their key role as conditioning variables for domestic demand and structural dynamics within the manufacturing sector. Finally, based on all the considerations outlined above, the following hypothesis test is proposed:

Hypothesis 1 (H1): (Null Hypothesis): Terms of trade do not negatively affect real manufacturing GDP (β1 ≥ 0), suggesting the absence of Dutch disease in Peru.

Hypothesis 2 (H2): (Alternative Hypothesis): Terms of trade negatively affect real manufacturing GDP (β1 < 0), suggesting the presence of Dutch disease in Peru.

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics and Data Visualization

Before proceeding with the econometric analysis, it is useful to provide a preliminary characterization of the data employed in this study.

Table 1 presents the main descriptive statistics for the seasonally adjusted series of manufacturing GDP (M), aggregate real GDP, and private gross fixed investment (PGFI), together with the non-seasonally adjusted indices of terms of trade (T) and the real exchange rate (RE).

All variables are expressed as indices with base year 2007 = 100, which ensures internal consistency in their temporal dynamics. Each variable comprises 52 quarterly observations covering the period 2012:Q1–2024:Q4. The statistics reported include the mean, standard deviation, minimum and maximum values, the coefficient of variation (C.V.), skewness, and kurtosis, together with the number of observations (N). These measures summarize the central tendency, dispersion, and distributional properties of each series, allowing a concise view of their behavior over the sample period.

The descriptive statistics presented in

Table 1 reveal that all variables exhibit moderate dispersion and well-defined central tendencies across the sample period (2012 Q1–2024 Q4). T and RE display relatively mild variability, consistent with the gradual adjustment patterns typical of external and monetary variables. In contrast, PGFI shows the highest volatility, with a high kurtosis value indicating episodes of sharp fluctuations in capital formation, particularly during the pandemic shock.

The manufacturing GDP (M) series also presents noticeable leptokurtic behavior, reflecting both the contraction in 2020 and the rapid rebound that followed. Meanwhile, aggregate GDP remains comparatively stable, suggesting that the wider economy was less sensitive to short-term external shocks than the manufacturing sector. Overall, the relatively low coefficients of variation indicate a reasonable level of internal consistency across the dataset, while the differing degrees and directions of skewness suggest that the series do not exhibit a uniform pattern of distortion. Taken together, these properties support the reliability of the econometric analysis developed later in this section.

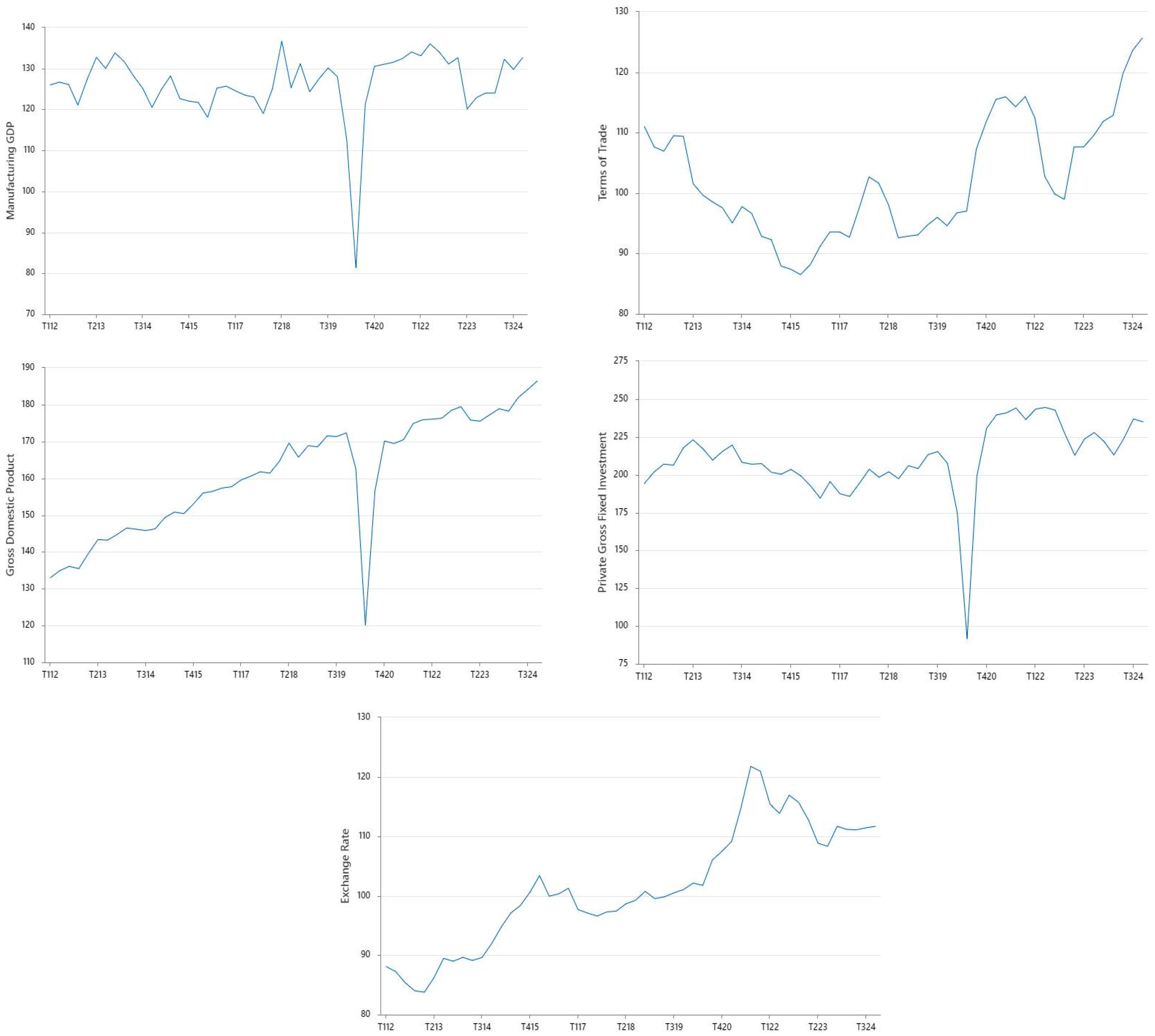

To complement the statistical overview,

Figure 1 illustrates the temporal evolution of the five variables under study. Each series is plotted in index form (2007 = 100), with seasonally adjusted data for M, aggregate GDP and PGFI, and raw indices for T and RE, allowing a visual inspection of their trajectories and short-term fluctuations over the period 2012:Q1–2024:Q4. This graphical representation provides an intuitive sense of co-movement and relative volatility among the variables, laying the groundwork for the discussion that follows on the empirical consistency of their dynamic patterns.

Figure 1 depicts the trajectories of the five variables during the period 2012:Q1–2024: Q4. The manufacturing GDP (M) series exhibits clear cyclical movements, with a sharp contraction in 2020 followed by a rapid rebound and subsequent stabilization, consistent with the post-pandemic recovery of industrial output. The terms of trade (T) display two pronounced upswings—around 2017 and 2024—separated by a temporary fall, reflecting changes in global commodity prices. Aggregate GDP shows a steady upward trend interrupted only by the 2020 downturn, confirming the economy’s gradual long-term expansion. Private gross fixed investment (PGFI) mirrors this behavior but with greater amplitude, evidencing high sensitivity to external and domestic shocks. Finally, the real exchange rate (RE) reveals moderate variability and a tendency to appreciate during the commodity boom years before stabilizing in the post-2022 period.

The heterogeneous dynamics observed across these variables suggest that external and domestic adjustments have not been synchronized, a pattern that justifies the use of HAC (Newey–West) robust standard errors in the regression analysis to account for potential short-term heteroscedasticity or mild serial correlation arising from transitory shocks such as that of 2020.

3.2. Unit Root Tests and Lag Selection

Prior to estimation, unit root tests were conducted to verify the statistical validity of the series (see

Table A1 in

Appendix A). It was found that for the real manufacturing GDP index (M), both tests strongly reject the null hypothesis of a unit root, with highly significant test statistics (τ-ADF = −2.868;

p < 0.0490 and τ-DF-GLS = −2.904;

p < 0.003), confirming that the series is stationary in levels. This characteristic is crucial, as it ensures the validity of the estimators when the variable is included as the dependent variable in the regression model. In the case of ToT (T in the model), the results of both tests consistently fail to reject the null hypothesis, indicating that the series contains a unit root (τ-ADF = −2.258,

p = 0.4564; τ-DF-GLS = −1.691,

p = 0.581). This suggests that the variable is non-stationary in levels and must be transformed into first differences to avoid specification issues and spurious regression.

Similarly, the real exchange rate (RE) does not show sufficient statistical evidence to reject the non-stationarity hypothesis under either test. Although the ADF test approaches the critical threshold (τ-ADF = −3.311, p = 0.0644), the DF-GLS result confirms the presence of a unit root (τ = −2.115, p = 0.311), validating its treatment as a first-order integrated variable. As for private gross fixed investment (PGFI), both tests yield robust results that allow for rejection of the null hypothesis of a unit root with high significance (τ-ADF = −3.688, p = 0.0230; τ-DF-GLS = −3.225, p = 0.001), leading to the classification of this series as stationary in levels. This supports its direct inclusion in the model without the need for differencing.

As for the real GDP variable (GDP), both tests fail to reject the null hypothesis of a unit root, as indicated by the non-significant test statistics (τ-ADF = −1.188,

p = 0.6820; τ-DF-GLS = 0.114,

p = 0.719). These results consistently classify the series as non-stationary in levels, suggesting the need for first-differencing before its inclusion in the econometric model. This methodological decision reflects the need to prevent potential risks of spurious regression and aligns with recommendations in the specialized literature [

58], which recommend differencing the non-stationary variables to ensure that all series included in the model are I(0).

As previously outlined in the methodological section, the lag structure applied to the real exchange rate (RE) was not arbitrary but the result of an iterative empirical process. This refinement was carried out prior to the estimation of the econometric model and relied on standard information criteria—namely, the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC), the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC), and the Hannan–Quinn Criterion (HQIC)—in conjunction with the adjusted R2 of each specification.

Although this approach relies on the available sample, it is consistent with the methodological framework of ex-post econometric analysis, where empirical fit and theoretical plausibility guide the model’s refinement. The results are summarized in

Table 2 and provide the basis for the lag structure adopted in the estimation presented in

Table 3.

Following the optimal lag structure identified in the previous table, the final regression results are presented below.

3.3. Interpretation of Regression Coefficients

The estimated coefficient for the variation in terms of trade (ΔT) was negative and significant at the 10% level (−0.2980;

p = 0.0786), suggesting that improvements in ToT are associated with a contractionary effect on M. This result is consistent with the Dutch disease hypothesis, reflecting the vulnerability of the manufacturing sector to external shocks (see

Table 3).

In the Peruvian case, where increases in ToT have been consistently driven by mining exports—which accounted for over 58.1% of total exports between 2003 and 2020—empirical evidence indicates that this commodity boom negatively affected the manufacturing sector and clearly exhibited a pattern consistent with Dutch disease [

59]. Earlier studies corroborate this link: between 2004 and 2011, mineral price booms led to a fourfold increase in mining exports, surpassing 60% of total exports, with signs of Dutch disease already observable through structural pressures on tradable sectors [

60]. This diagnostic perspective is echoed by [

17] and further reinforced by Nobel laureate Paul Krugman, who in 2014 publicly stated that Peru exhibits characteristics of Dutch disease due to its reliance on extractive exports.

These findings confirm that the Peruvian ToT boom has been mainly driven by resource-based external dynamics. Recent studies have already warned of the risk of industrial decline in the face of external booms—a common pattern in emerging economies such as Mexico, Chile, and Colombia [

2,

7,

51], where primary export surges have tended to erode industrial sectors. From a sustainability perspective, this finding suggests that growth driven by favorable ToT does not necessarily strengthen the productive base in a structural sense. Without active and coherent industrial policies, the manufacturing sector tends to stagnate, weakening its long-term contribution to development.

The estimated coefficient for the variation in aggregate real GDP (ΔGDP) was positive and highly significant (0.3064;

p = 0.0002), indicating that stronger overall economic growth is associated with an increase in manufacturing GDP. This result confirms the existence of a procyclical relationship between general economic activity and industrial performance. In the Peruvian context—where GDP growth is often driven by external demand for raw materials [

1,

59,

60]—this finding shows that manufacturing still responds to the broader economic cycle, benefiting at least partially from overall economic expansions.

Nonetheless, this dependence also exposes the sector to vulnerabilities stemming from global macroeconomic shocks. While aggregate growth supports the sector, without improvements in productive capacity and technological innovation, this boost may prove transitory. The result also suggests that, without strengthening domestic productive linkages, growth in the manufacturing sector risks becoming overly dependent on external factors. Under such conditions, it is unlikely to consolidate itself as an autonomous pillar of sustainable long-term economic development.

The estimated coefficient for PGFI was positive and highly significant (0.2047; p = 0.0001), indicating that higher levels of private investment translate into increased real manufacturing GDP. This result highlights the central role of investment in expanding the productive capacity of the industrial sector. In the Peruvian economy—where private investment constitutes the main source of capital formation—this direct relationship suggests that investment flows actively contribute to driving manufacturing activity, especially during periods of recovery or economic growth.

However, the sustainability of this momentum depends on the quality of the investment itself. If it is concentrated in extractive sectors or short-term capital, its positive effect on industry may be limited [

60]. This underscores the need for policies that steer investment toward industrial processes with greater value added and technological potential, particularly in economies vulnerable to Dutch disease and low productivity traps [

17,

60]. From a structural perspective, this finding reinforces the notion that strengthening the manufacturing sector requires not only investment, but also an enabling environment that promotes long-term productivity and competitiveness through industrial upgrading, institutional capacity and macroeconomic resilience [

8,

14].

The estimated coefficient for the variation in the real exchange rate lagged four quarters was negative and statistically significant (−0.4101; p = 0.0413), indicating that a depreciation in the real exchange rate observed one year earlier tends to reduce current real manufacturing GDP. This result may be explained by the import-intensive structure of inputs and capital goods in Peru’s manufacturing sector. A depreciation raises the cost of these imported inputs, increasing production costs and negatively affecting industrial activity—particularly in segments with low local integration.

Moreover, the lagged effect—identified through the optimal specification guided by AIC, BIC and HQIC—suggests that the impact of exchange rate fluctuations is not immediate but rather transmitted with delay through investment decisions, inventory replacement, or production planning. In terms of sustainability, this finding reveals a structural vulnerability: the sector’s high external dependence limits its ability to adapt to exchange rate shocks, thereby undermining its productive stability over time.

The estimated coefficient for DCOVID was negative and statistically significant (−7.236; p = 0.0007), indicating that the mandatory lockdown introduced from the second quarter of 2020 until the end of the year had a sharp and contractionary effect on manufacturing GDP. This outcome reflects the magnitude of the disruption generated by the pandemic, which temporarily paralyzed productive activities and constrained industrial recovery in the short term. The inclusion of the COVID-19 dummy slightly moderated the statistical significance of the ToT coefficient; however, the persistence of its negative sign confirms the sensitivity of the manufacturing sector to external shocks, as expected under Dutch disease dynamics.

Finally, the constant term in the model, with a positive and highly significant value of 83.6089 (p = 0.0001), reflects the baseline level of real manufacturing GDP when the explanatory variables are at their mean or neutral values. This result suggests the presence of a stable structural component in the sector’s performance, indicating a residual productive base that endures even without short-term stimuli. Such stability is key to consolidating a resilient productive core capable of sustaining itself over time despite external fluctuations.

Taken together, the persistence of a negative association between ToT improvements and manufacturing GDP points to potential risks regarding the structural sustainability of the sector. The findings reveal that external gains derived from commodity booms have not been translated into sustained industrial consolidation, but rather into cyclical expansions with limited productive diversification.

3.4. Interpretation of Model Fit and Statistical Validity

This section presents the main goodness-of-fit and diagnostic statistics of the estimated econometric model. These indicators facilitate the evaluation of the model’s explanatory power and the validity of its underlying assumptions. As reported in

Table 3, the overall fit is satisfactory, providing statistical support for interpreting the impact of ToT on real manufacturing GDP in Peru.

The mean value of the dependent variable, representing real manufacturing GDP, is 126.3077, while its standard deviation is 8.5284. These figures indicate that the series exhibits moderate dispersion around its mean, suggesting relative stability in manufacturing GDP over the observed period. The standard error of the regression (3.9214) indicates a low level of dispersion in the residuals, which translates into strong predictive power for the model within the period of analysis. Complementarily, the residual sum of squares (630.4925), although more technical in nature, remains within acceptable levels for this type of study, confirming that residuals do not deviate significantly from the mean.

The estimated model exhibits a high degree of fit, as indicated by the R-squared coefficient (0.8115) and its adjusted version (0.7885), suggesting that over 70% of the variability in real manufacturing GDP is explained by ToT and the macroeconomic control variables included in the model. This level of explanatory power is particularly relevant in empirical studies of productive sectors, where dynamics are shaped by both internal and external factors.

The F-statistic (301.5683) and its corresponding p-value (<0.01) indicate that the full set of variables included is statistically significant, reinforcing the robustness of the model for assessing structural relationships in the manufacturing sector. In light of the research objective, this supports the use of the model as an appropriate tool to determine whether ToT represent a systemic risk to the sustainability of the manufacturing sector.

Furthermore, the value of the Durbin–Watson statistic (1.7851) falls within the acceptable range, suggesting the absence of severe autocorrelation in the residuals—an essential condition to ensure estimator efficiency. This is further supported by a low rho value (0.1041), indicating weak serial dependence. A more robust test for autocorrelation (LM up to order 4) is provided later as part of the model’s diagnostic checks. Finally, the information criteria—Akaike (AIC: 267.4088), Schwarz (BIC: 278.5097), and Hannan–Quinn (271.5862)—were used to determine the optimal lag structure for the real exchange rate and the interest rate. The selected model corresponds to the specification with the lowest values across these criteria, confirming its adequacy in terms of both parsimony and overall goodness of fit.

In substantive terms, the consistency of these statistics supports the conclusion that the model provides a solid basis for interpreting the effects of ToT on manufacturing performance. This is a critical point, given that a negative relationship—as estimated in this case—may have profound implications for the sustainability of the manufacturing sector, revealing that external improvements in relative prices can weaken the structural foundations of the national productive apparatus.

To validate the statistical consistency of the estimated econometric model, several diagnostic tests were applied to verify compliance with the classical assumptions of linear regression. Specifically, the analysis evaluated the presence of heteroskedasticity, serial autocorrelation, parameter stability, residual normality, the model specification and potential multicollinearity among explanatory variables (for completeness, see

Table A2 in

Appendix A). The results show that the model does not exhibit any statistically meaningful violations of these assumptions, thereby reinforcing the robustness of the econometric findings reported in this study.

Regarding the heteroskedasticity test (Breusch–Pagan), the p-value obtained (0.6016) indicates that the null hypothesis of homoskedasticity cannot be rejected, suggesting that the variance of the residuals remains constant across observations. This stability in the dispersion of errors adds confidence to the estimation of the coefficients, particularly when assessing the negative impact of ToT on the manufacturing sector. In studies addressing Dutch disease, avoiding estimation bias is critical, as distortions in the residuals could lead to misleading conclusions about the structural effects of export booms.

As for the autocorrelation test (LM up to order 4), the p-value of 0.4866 indicates no evidence of serial correlation in the residuals up to the fourth lag. This implies that the errors are time-independent, which is especially relevant when lagged variables such as the exchange rate or interest rate are included in the model. The absence of autocorrelation strengthens the credibility of the lagged effects identified, allowing for a more accurate analysis of the temporal dynamics that may be associated with delayed deindustrialization processes—one of the mechanisms described in the Dutch disease literature.

Additionally, the parameter stability test (CUSUM–Harvey–Collier) yielded a p-value of 0.8290, showing no significant evidence of structural change in the model’s parameters over the period analyzed. This temporal consistency supports the validity of the negative effect of ToT on manufacturing GDP across time, reinforcing the hypothesis that the observed phenomenon is not merely cyclical, but potentially structural. The persistence of such negative effects can be interpreted as an indication of risk to the long-term sustainability of the industrial sector, particularly when there is no observable capacity to adapt to external booms.

Likewise, the Jarque-Bera test for residual normality yields a χ2(2) statistic with a p-value of 0.6281, supporting the null hypothesis that the errors are normally distributed. This ensures that the statistical inferences made—such as the significance of coefficients and confidence intervals—are valid. Although this result is not directly related to Dutch disease or sustainability, it confirms that the model meets the fundamental assumptions of Ordinary Least Squares (OLS), thereby strengthening the overall robustness of the analysis.

Moreover, the Ramsey RESET for functional specification reports a p-value of 0.6268, indicating that the null hypothesis of correct model specification cannot be rejected. This result confirms that the functional form used in the regression is appropriate and that relevant non-linearities or omitted variables are unlikely to drive the observed relationship between ToT and manufacturing GDP. Ensuring a correctly specified model is essential in this context, as misspecification could mask or distort the structural mechanisms underlying Dutch disease dynamics, particularly in economies vulnerable to external shocks and sectoral imbalances.

Finally, the values of all variance inflation factors (VIFs) fall within low ranges (between 1.164 and 2.000), well below the conventional threshold of 10 typically used to detect severe collinearity. This indicates that there are no multicollinearity problems among the regressors. The absence of redundancy between explanatory variables allows for a clearer identification of the effect of ToT, a key factor in accurately diagnosing potential symptoms of Dutch disease (for completeness, see

Table A3 in

Appendix A). Moreover, having a parsimonious and stable model contributes to a more reliable assessment of long-term risks to the sustainability of the manufacturing sector.

Based on these results, the hypothesis test confirms that ToT exert a negative and statistically significant effect on real manufacturing GDP, thereby providing empirical validation of Dutch disease in the Peruvian context. This finding reveals that the external benefits derived from trade windfalls can structurally weaken the industrial base, undermining its long-term sustainability. Thus, although the model does not explicitly measure whether growth is driven by primary resources, the negative association between ToT and manufacturing GDP—together with historical signs of Dutch disease in Peru and international evidence from resource-dependent economies—suggests that commodity-based growth may pose structural risks and reinforces the rationale for considering industrial policies as part of a strategy to promote long-term structural sustainability.

4. Discussion

The results of the estimated econometric model reveal a negative and statistically significant relationship between ToT and real manufacturing GDP in Peru, offering robust empirical evidence consistent with a Dutch disease configuration. Specifically, the negative sign associated with the ΔT variable suggests that increases in the relative prices of exports—primarily minerals—do not strengthen the manufacturing sector; on the contrary, they contribute to its relative weakening, thereby undermining its long-term structural sustainability [

5,

7]. Although the coefficient attains significance at the 10% level (

p = 0.078), its magnitude and sign remain fully consistent with theoretical expectations and contemporary empirical evidence, confirming that favorable ToT conditions exert contractionary pressures on manufacturing activity [

17,

27,

51].

This finding aligns with [

61], who shows that in resource-abundant contexts, export booms tend to slow down manufacturing growth, in contrast to the expansion observed in the service sector. In Peru’s case, this phenomenon is mainly associated with the sustained mining boom of the past two decades, driven by rising international metal prices, which has led to a reallocation of resources toward extractive activities, to the detriment of industrial production.

This pattern reinforces the early warnings of Krugman, who anticipated a Dutch disease configuration in Peru—marked by natural resource primacy, an appreciated currency, and a weakened manufacturing base [

62]. Supporting this view, empirical evidence shows that during the same period, Peru’s ToT index peaked at an all-time high of 144.21 in 2024, reflecting a substantial increase in foreign earnings [

63]. However, the performance of the manufacturing sector did not follow this upward trend; rather, it was gradually displaced, both due to factor reallocation toward more profitable extractive activities and the relative loss of industrial competitiveness.

This dynamic resembles what [

64] documents in other emerging economies affected by commodity booms, where high resource dependence and limited diversification have been linked to structural vulnerabilities in the manufacturing sector. In the African context, South Africa, Botswana, Namibia, Ghana, and Zambia exhibit a strong reliance on mineral exports—including gold, platinum, diamonds, uranium, and copper—accompanied by persistent signs of manufacturing decline. In parts of Asia, economies such as Mongolia, Indonesia, the Philippines, Papua New Guinea, Kazakhstan, and Timor-Leste depend on commodities ranging from copper, coal, and nickel to oil, gas, and agricultural products, and face comparable risks when resource windfalls are not channeled into productive diversification and technological upgrading. Taken together, this body of evidence underscores significant risks regarding the regressive effects that positive ToT shocks can exert on the structural sustainability of the manufacturing sector, consistent with cross-country evidence reported by [

64] and further supported by [

22,

27,

47,

52]. These patterns highlight the importance of rethinking strategies for productive diversification and technological upgrading as a means of preventing prolonged scenarios of deindustrialization.

This type of phenomenon has been documented across various Latin American countries. In Chile and Argentina, for example, a study highlights how copper-centered export specialization has forced authorities to adopt countercyclical measures to mitigate exchange rate distortions and industrial competitiveness losses [

65,

66]. Similarly, research conducted in Colombia warns that, in the absence of active industrial policies, favorable ToT cycles tend to generate “short-lived gains,” while weakening domestic production linkages [

2].

At the global level, recent studies reinforce this view, showing that ToT volatility not only increases macroeconomic uncertainty but also reduces the allocative efficiency of capital, which negatively affects non-primary sectors [

14,

22]. In this regard, the evidence for Sub-Saharan Africa also suggests that exposure to ToT shocks disproportionately impacts the industrial sector, especially in contexts of weak governance and incipient financial development [

32,

66]. In the Peruvian case, the magnitude and persistence of the negative coefficient despite—the shock-adjusted specification—align with this body of evidence. The significant drop in manufacturing GDP in response to improvements in ToT is not only statistically validated but also theoretically predictable in economies undergoing re-primarization processes [

16].

The interpretation of these results also requires consideration of the role played by the control variables. Private gross fixed investment (PGFI) maintains a positive association with manufacturing GDP, in line with the literature on endogenous growth [

24,

25]. However, the interaction between investment and ToT does not appear to be neutral: when ToT improves, part of that investment is redirected toward extractive sectors or low value-added activities, thereby weakening the manufacturing productive base [

15,

21]. This reallocation may also be reflected in the appreciation of the real exchange rate, a variable that, with a lag, exhibits contractionary effects on the industry by reducing external competitiveness [

18,

27].

The empirical evidence presented is consistent with warnings in the specialized literature: in commodity-exporting countries, external booms do not automatically lead to sustainable growth but may exacerbate structural imbalances if not accompanied by a strategy of productive diversification [

36]. In the Peruvian case, this situation is further aggravated by a rigid pattern of specialization, where manufacturing growth increasingly depends on external components, imported inputs, and high opportunity costs [

9,

19].

Furthermore, the sustainability of the manufacturing sector cannot be understood solely in terms of GDP growth. It also involves the sector’s ability to generate quality employment, foster technological innovation, and maintain a stable share of total GDP—dimensions that are being eroded by the displacement mechanisms associated with ToT [

34,

35]. In this sense, the econometric model does not merely quantify a negative correlation but helps to reveal a structural conflict between extractive rent-seeking and sustainable industrial development. Taken together, the evidence points to a gradual erosion of the country’s manufacturing sector, with potential implications for structural sustainability if the current trajectory persists.

Additionally, the findings are consistent with recent studies warning that positive ToT shocks may generate a “growth trap” in commodity-exporting economies, where windfall revenues tend to concentrate in low-linkage and low-innovation sectors [

31,

67]. In the Peruvian case, the manufacturing sector has not only lost its share of GDP, but also its participation in formal employment and national productive investment, which constitutes a severe risk for medium- and long-term sustainability—particularly in a context of technological transition and rising demand for greener production [

12,

15].

Moreover, comparative experience in emerging economies confirms that the contractionary effects on the industry can be mitigated when macroeconomic buffer policies, the development of productive linkages, and active strategies of industrial upgrading are in place [

2,

32]. However, Latin America continues to face high concentration in low-tech primary exports, which limits its ability to generate quality industrial jobs and sustain long-term manufacturing expansion [

15]. The Peruvian evidence illustrates the importance of articulating trade, fiscal, and industrial policies capable of counteracting this trend.

The econometric model confirms that, in addition to the negative effect of ToT, variables such as private gross fixed investment and the lagged real exchange rate exert a significant influence on the performance of the manufacturing sector. The COVID-19 dummy also plays a relevant role, capturing the severe temporary shock of 2020 while preserving the sign and economic coherence of the ToT coefficient, thereby reinforcing the structural interpretation of the results. Even though the investment is private, its behavior is strongly conditioned by the policy environment: the quality of industrial promotion policies, the structure of the tax regime—which at times exhibits anti-export biases—and the procyclical use of fiscal revenues from external booms. These conditions shape an environment that may either encourage or discourage long-term productive investment, thus affecting the structural sustainability of industrial growth [

23,

36,

47].

The literature has pointed out that Dutch disease is not an inevitable outcome, but rather a likely consequence if effective neutralization mechanisms are not implemented—such as fiscal stabilization funds, managed floating exchange rate regimes, and industrial promotion programs based on sectoral productivity criteria [

14,

35]. Although Peru has maintained macroeconomic stability over recent decades, it still lacks a robust industrial policy framework that would enable the transformation of export rent surpluses into platforms for structural change [

9,

17].

In light of this, the findings highlight the importance of intersectoral economic governance capable of coordinating monetary, exchange rate, technological, and trade policies under a strategic vision of sustainable development. This would involve aligning goals for productive diversification, reduced commodity dependence, and formal employment generation with specific actions to mitigate the risks of external overexposure. In this regard, industrial sustainability guidelines should be consistent with the 2030 Agenda and global demands for energy transition, circular economy, and inclusive innovation [

68].

On the other hand, the econometric technique used in this study was deliberately selected for its ability to provide a clear interpretation of the coefficients, avoiding unnecessary complexities that could obscure the underlying structural relationships. Similar models have recently been used to assess financial sustainability using OLS, in order to maintain analytical clarity and avoid overfitting [

69].

Moreover, within the scope of this discussion, beyond the Peruvian case, the findings are also relevant to other exporting economies with industrial structures vulnerable to external volatility. The empirical results of this study not only validate the hypothesis regarding the negative relationship between ToT and the manufacturing sector, but also align with broader concerns in the literature about the need to reconsider Peru’s model of international integration [

8,

9,

13]. The patterns observed are consistent with scenarios in which limited diversification, innovation, and resilience increase the risk of maintaining a regressive specialization pattern, with potential implications for both economic sustainability and social cohesion [

16,

60,

70].

Finally, the model incorporates robust HAC (Newey–West) standard errors, a standard practice in applied macroeconomics when dealing with quarterly data and periods marked by significant exogenous shocks such as the COVID-19 disruption. This adjustment ensures reliable inference without altering coefficient signs or economic interpretation [

54,

56,

57]. The stability of the parameters and the internal coherence of the results across specifications reinforce confidence in the robustness and structural relevance of the findings.

5. Conclusions, Policy Implications, Future Directions and Final Remarks

5.1. Conclusions

The main contribution of this study lies in establishing an explicit and empirical link between Dutch disease and the structural sustainability of the Peruvian manufacturing sector—addressing both issues in an integrated manner rather than treating them separately or only theoretically. This integration allows for a deeper understanding of the mechanisms through which external shocks translate into regressive dynamics for strategic sectors of the real economy. In addition, this study proposes an explanatory framework to understand how such shocks can undermine the productive resilience of the manufacturing sector in economies dependent on commodity exports, shifting the analytical focus away from the prevailing emphasis on the aggregate effects of ToT or the behavior of primary sectors. By doing so, the study contributes empirical insights relevant to the design of sustainable industrial policies.

This investigation extends beyond merely quantifying the impact of ToT on industrial performance; it offers a structural and critical interpretation of this relationship. Given the signs of a potential Dutch Disease dynamic in Peru, we set out to test the hypothesis that terms of trade exert a negative effect on real manufacturing GDP—a hypothesis that was empirically confirmed by the results obtained. The estimated coefficient for ToT was negative and statistically significant at the 10% level (p = 0.078), which is typical in empirical work based on quarterly macroeconomic data for emerging economies. The sign and economic meaning are fully aligned with theory, indicating that favorable ToT conditions tend to constrain manufacturing performance rather than strengthen it. These results clearly demonstrate—both empirically and conceptually—that the manufacturing sector exhibits consistent signs of Dutch disease, coinciding with the improvement in the ToT during the 2012–2024 period. The estimated econometric model, based on OLS with robust Newey–West standard errors, is structured to prioritize analytical clarity and reliable inference, reflecting a deliberate methodological choice aligned with the objectives of this research and the characteristics of the quarterly dataset. Additionally, aggregate GDP and PGFI showed positive and statistically significant effects on manufacturing activity, while a lagged depreciation of the real exchange rate exerted a negative influence. Moreover, the COVID-19 dummy accounted for the abrupt but transitory shock of 2020. Importantly, even with this adjustment, the ToT coefficient preserved its expected sign, reinforcing the interpretation of a structural rather than episodic effect.

This specification ensures consistent estimation and interpretability, revealing a negative and economically meaningful relationship between ToT and the real manufacturing GDP, with marginal statistical significance, raising serious concerns about the country’s capacity to sustain healthy industrial growth in the context of external booms. The absence of heteroskedasticity, autocorrelation, mis-specification and multicollinearity, together with parameter stability, reinforces the reliability of these results. Taken together, these findings indicate that Dutch disease pressures are emerging within Peru’s industrial structure, posing a tangible risk to the long-term structural sustainability of the manufacturing sector and signaling an erosion of productive resilience rather than a mere sectoral fluctuation. In sum, by addressing this gap in the literature on Dutch disease and sectoral sustainability in the Peruvian context, the findings suggest an urgent need to strategically reorient industrial policy toward a more diversified, inclusive, and innovation-driven growth model, capable of productively absorbing external rents and ensuring the long-term resilience of the manufacturing sector amid persistent global volatility.

5.2. Policy Implications

The evidence obtained in this study suggests several lines of action for economic policy. It is necessary to strengthen countercyclical fiscal mechanisms by enhancing the design and operational capacity of the Fiscal Stabilization Fund (FEF), which—despite its existence—has experienced a significant erosion of resources, declining from USD 5.471 billion in 2019 to USD 3.212 billion by the end of 2024, with a minimum of USD 1.049 million in 2020. This reduction, partly reflecting the fiscal pressures of the pandemic period, underscores the need to expand the FEF’s resource base and to refine its intervention rules to allow for earlier, more flexible, and pre-emptive disbursements. Strengthening these features would enable the FEF to act as a more effective buffer against increasingly frequent and unpredictable terms-of-trade shocks, mitigating their fiscal impact, reducing the need for abrupt expenditure adjustments during downturns, and ensuring greater resilience in an environment of heightened volatility in international markets.

Likewise, selective industrial upgrading should be promoted by directing windfall revenues toward technology adoption, process innovation, and the development of manufacturing segments with higher value added. In parallel, it is important to encourage diversification through credit lines and tax incentives for firms that develop new export products and markets, complemented by public procurement schemes that prioritize domestic industrial inputs. These measures should be integrated into a broader strategy that aligns industrial policy with sustainability goals, including the 2030 Agenda, the energy transition, and the circular economy, thereby ensuring that the manufacturing sector strengthens its resilience to global market volatility. Beyond Peru, the proposed mix of fiscal stabilization, targeted upgrading and diversification incentives is directly applicable to other resource-dependent economies, and can inform programs supported by multilateral institutions and foreign investors.

5.3. Future Directions

This study outlines several avenues for future research. First, it is essential to deepen the analysis by incorporating structural variables such as employment, innovation, and technological change, which were not included at this stage due to limitations in the availability of reliable, high-frequency data for the period analyzed. Second, exploring the role of investment in innovation and technological transformation as a buffer against the adverse effects of external windfalls is a key area of inquiry. Third, future research could explore comprehensive economic policy approaches that go beyond short-term concerns and assess their effectiveness in enabling the construction of a resilient, inclusive manufacturing sector capable of sustaining its contribution to national development—even amid international volatility. In addition, as data availability improves, further research could employ alternative methodologies, such as Structural VAR (SVAR) models, which—unlike a simple VAR—would allow the imposition of theoretically grounded restrictions to identify the distinct impact of ToT shocks on manufacturing performance, while preventing immediate feedback effects from being conflated with the original shock. Future work should extend the analysis to a comparative, cross-country setting to test the external validity of the mechanisms identified here. These factors represent particularly promising lines for future research aimed at deepening the understanding of the mechanisms through which ToT shocks influence the sustainability of industrial structures in resource-dependent economies.

5.4. Final Remarks

The Peruvian experience during recent commodity booms underscores a paradox: improvements in the terms of trade have coincided with a deeper re-primarization of the export structure, exacerbating the structural constraints of industrial segments already limited by long-standing technological and logistical weaknesses. These dynamics, partly driven by real exchange rate appreciation and resource reallocation, have eroded industrial competitiveness—mechanisms that, although not examined in detail here, warrant closer scrutiny in future analyses. Beyond external shocks, the trajectory of the manufacturing sector reflects the weight of domestic policy choices, particularly in shaping private investment incentives and directing resource windfalls toward productive transformation. Weak institutional capacity to translate temporary rents into lasting technological capabilities remains a persistent vulnerability, leaving the sector ill-prepared to respond to global market volatility.

Innovation deficits and the absence of advanced technological infrastructure further limit opportunities for diversification and value addition, restricting the sector’s ability to position itself competitively in higher value segments of international markets. In contrast to economies that have leveraged external rents to foster industrial upgrading, Peru’s manufacturing base continues to operate without a coherent framework for fostering digital transformation, skills development, and research-driven production.

The persistence of fragmented or short-lived industrial policy initiatives has prevented the formation of a robust and resilient productive fabric. Without a strategic, long-term vision that integrates human capital, technological infrastructure, and innovation ecosystems, the sector will remain vulnerable on volatile commodity cycles and exposed to the destabilizing effects of extractive-led growth.

Sustainable industrial expansion in this context requires more than favorable prices for manufactured exports: it demands an integrated approach that links macroeconomic stability with structural upgrading, positions the manufacturing sector as a driver of diversification, and embeds resilience into the broader economic model. Consequently, the Peruvian case serves as a practical template for economies seeking to convert temporary commodity windfalls into durable industrial resilience.