1. Introduction

The Farm Accountancy Data Network (FADN) was established in 1965 as an instrument of the European Commission’s Directorate-General for Agriculture (EC-DG Agri), designed to monitor trends in farm income across the European Union, and assess the impact of agricultural policies. While maintaining its characteristics and objectives unchanged, FADN has undergone a series of adjustments over time following the evolution of agricultural policies (i) at the beginning of the 90s with the MacSharry Reform, (ii) with the implementation of the Agenda 2000 reform [

1], and (iii) with the introduction of rural development measures. The latest revision follows the launch of the Farm to Fork strategy [

2] and the new Green Deal [

3,

4]. These policy initiatives have led the European Commission to implement a comprehensive reform of FADN and a conversion in Farm Sustainability Data Network (FSDN), aimed at broadening its scope beyond the economic dimensions to include environmental and social sustainability indicators, practically almost excluded from a survey of which the main aim was the determination of farm economic performance and the effect of subsidies. However, albeit to a lesser extent, the richness and long time-series coverage of FADN have enabled researchers to derive robust proxies for environmental pressure (e.g., nutrient surpluses, pesticide and energy intensity, livestock density) and for societal response (e.g., adoption of agri-environmental schemes). Although these applications demonstrate the database’s considerable potential for agro-ecological analysis, they also reveal its structural limitations, particularly in capturing outcome-based environmental impacts and biodiversity-related indicators [

5]. The social dimension is also a weak point of FADN. The survey historically offered only very aggregate social variables (family labour input, age of the holder, legal form), which are insufficient for analyzing key issues such as working conditions, gender equity, occupational health and safety, or intergenerational succession. In general, social sustainability indicators at the farm level are still largely missing from official statistical systems [

6,

7].

The new FSDN, besides representing more than a reform of FADN structure, is a paradigm shift, useful to support the policy evaluation framework of Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) Strategic Plan in 2023–2027 and the future Farm Stewardship approach after 2027. The opportunities provided by the conversion from FADN to FSDN are multiple: (i) the European Commission will have a more comprehensive source of data for the analysis and evaluation of the new CAP impacts; (ii) national governments will dispose of valuable insights for National CAP Strategic Plans and information to tailor measures to the specific needs and sustainability challenges; (iii) research institutions will have the possibility to explore new research fields and modelling; and (iv) farmers could have a more complete advice on environmental aspects and on intensity farming indicators. Furthermore, the revised framework emphasizes the need to improve the interoperability between data systems and the efficient use of already available information, with the goal of minimizing the administrative burden on both farmers and data collectors.

The architecture of the new dataset enhances the analytical potential of the network but also introduces operational and technical challenges: the management of a larger volume of variables, the increase in the number of tests ensuring the quality of data, and the development of effective tools for data validation and control.

In Italy, FADN is managed by the Italian Council for Agricultural Research and Economics—Research Centre for Policies and Bioeconomy (CREA-PB) and also Liaison Agency between Italy and the European Commission. Liaison Agencies are organized differently in the EU Member States and Italy is one of the twelve countries where the role is assigned to a research institute; this means a massive use of FADN data for research purposes and more comprehensive FADN informative content. In Italy and other Member States, the data collection is broader than is required for FADN: the versatility of the Italian FADN structure, stemming from the combination of detailed economic balance sheet results and technical parameters, and the integration with a set of variables not mandatory in the EU regulations, has been instrumental in supporting a wide range of studies with environmental and social objectives. The transition to FSDN represents a challenge but also offers opportunities to enhance the research system with new information.

The objective of this paper is to provide a critical analysis of the transition from FADN to FSDN, evaluating the methodological implications and implementation challenges for the data collection system with reference to the experience of Italy. Specifically, this paper aims to answer the following research questions: (i) How effectively can the final FSDN architecture provide new sustainability indicators required for assessing Green Deal and Farm to Fork objectives? (ii) What are the most important challenges and opportunities for the development of the FSDN in Italy?

The remainder of this paper is structured to address this analysis:

Section 2 describes the research analytical approach;

Section 3 details the legislative process, historical background, and organizational challenges of the FSDN conversion;

Section 4 provides a comprehensive overview of the new data architecture, detailing the specific economic, environmental, and social variables introduced; and

Section 5 discusses the resulting research opportunities and the critical implementation challenges, focusing on key elements such as interoperability, infrastructure, and ensuring farmer participation.

Section 6 reports the conclusions.

2. Research Analytical Approach

This study adopts a qualitative-critical desk research design to examine the transition from the Farm Accountancy Data Network (FADN) to the Farm Sustainability Data Network (FSDN). The analysis focuses on the regulatory, methodological, and operational implications of this reform at EU level, with particular attention to the implementation challenges and opportunities in Italy.

The desk-based approach is based on primary and secondary sources, including the following:

Key Regulatory Documents: EU Basic Act, delegated and implementing regulations that establish the final FSDN structure and the list of new variables.

Precursor technical reports: documents and outputs from preparatory projects, including the FLINT (Farm Level Indicators for New Topics in Policy Evaluation) project and the final IPM2/FSDN report, essential for understanding the variable selection process and the final reduction in the dataset.

Internal CREA-PB documentation related to its role as Liaison Agency in the conversion process and in the network’s technical and methodological development.

Sources were selected for their ability to articulate the methodological development of FSDN and the critical challenges identified by EU institutions and Member States. The analysis focuses on evaluating the final regulatory framework against the initial policy ambitions. The methodological approach is guided by the need to verify the extent to which the FSDN architecture succeeds in overcoming historical data gaps in the environmental and social dimensions, aligning with the principles of holistic sustainability. The paper underlines the methodological trade-off between political ambition for a comprehensive impact evaluation and the operational feasibility of data collection at the microeconomic level.

3. The Evolution of FADN and the Conversion into FSDN

The legal basis of FADN is dated 15 June 1965 when the Reg. 79/65/EEC was adopted as a system for collecting accounting data on farm incomes at the microeconomic level. The main aim of FADN was to provide reliable data for the analysis and evaluation of impacts of Common Agricultural Policy (CAP), introduced in 1962. Italy, Germany, France, the Netherlands, Belgium, and Luxembourg were the Member States with a sample of 9250 agricultural holdings. Amendments and adaptation needs (like in the farm selection procedures) led to the Council Regulation 1217/2009. Between 1965 and 2009, the same structural and procedural framework has been maintained. Adjustments in the informative content have been the consequence of the evolution of agricultural policies that raised the need to gather new data and indicators for the impact assessment of the new political framework. At the beginning, the Common Agricultural Policy supported commodity price policies without concerns about the negative effect of intensive farming practices. Problems in the international markets (price distortions due to production-oriented policies) and awareness of the importance of environmental aspects in agriculture, led to the semi decoupled income support and accompanying measures (early retirement, agro-environmental measures and forestry) introduced at the beginning of 90s with the MacSharry Reform. Different agri-environmental schemes have been applied in the European countries and for the first time the farmer was considered as active part of environment and landscape conservation. The sustainability of agriculture was the core of Agenda 2000 Reform that consolidated the changes introduced in the MacSharry Reform in 1992, integrating environmental and structural considerations into the implementation of the policy. Agenda 2000 package for agriculture has been supplemented by a regulation on rural development with new measures to diversify agricultural holdings and promote environmental practices. The need to evaluate the farm’s environmental performance, the evolution of CAP, the development of more environmental-friendly intervention in the rural development policies, the new strategies of the EU agricultural sector (like the EU Green Deal, the Biodiversity Strategy, the Farm to Fork strategy) are the main reasons for the development of new indicators based on all the dimensions of sustainability in a holistic approach.

The process of conversion of FADN into Farm Sustainability Data Network (FSDN) involves all EU Member States and it is the final step of a long process started around 10 years ago with several preparatory documents, events and projects. Among them are the following:

FLINT (Farm Level Indicators for New Topics in Policy Evaluation, 2014–2016) research project involving nine Member States in a feasibility study investigating the addition of a substantial number of new variables on over 1000 farms. Many of the variables tested in this project were ultimately integrated into the FSDN.

Analysis of the different structures of FADN, at the European level [

8], investigating how the 28 Member States carry out the survey in terms of financial and human resources and their good practices (period 2012–2014) and the cost of the transition [

9].

Final report of the IPM2/FSDN (Integrated Pest Management 2/FSDN) pilot project [

10] on the feasibility of the conversion. The analysis has involved Liaison Agencies, surveyors, farmers, giving for the first time an overview of the variables potentially detectable with FSDN, the difficulties in gathering especially new environmental and social variables, and the methods to reduce statistical disturbance. The project identified 16 topics and 68 sub-topics, considered in defining the final structure of the network.

Special Report by the Court of Auditors [

11] audited the European Commission’s use of data and analytical techniques for CAP analysis, finding that, while large amounts of data exist, details on important elements were scarce or missing. The report specifically noted a lack of information on applied environmental practices and income from non-agricultural activities, as well as a deficit in the tools needed to effectively use “big data”.

Officially, the conversion of FADN into FSDN was first discussed in a document [

2] announcing the creation of a new network to collect data suitable to be used for the Farm to Fork strategy and other sustainability goals. Public consultations followed in 2021 [

12], leading to the establishment of three thematic working groups in which Member States’ Liaison Agencies participated. The Expert Group for Horizontal Questions concerning CAP, which included all the Liaison Agencies of the EU Member States, began meeting in spring 2021 to address all the most important issues of the transition:

Strengthening, simplification, and methodological improvements: what is the current set of variables and how to improve the network’s structure and collection methodologies (highly differentiated in the EU Member States);

Improvement of Information Technology (IT) and human resources in terms of significant investments in new digital infrastructure and training of data collectors (high number and complexity of the new variables);

Tools to enhance farmer involvement (incentives);

Interoperability: a key concern of the FSDN scheme, which reinforces the principle of “collect data once and use it many times”;

Role of advisory services in supporting farmers and promoting network participation;

Access to basic data and protection of privacy (secure access for research purposes).

In February 2025, the EU CAP Network together with the EU Commission (DG Agri) organized a workshop in Brussels addressed to FSDN stakeholders and CAP managers and evaluators. Key aspects of the transition, understanding of the new data collection requirements, and good experiences in the Member States have been discussed; FSDN stakeholders include farmers, data collectors and/or advisers, Liaison Agencies in the Member States, and policymakers at the national and EU levels.

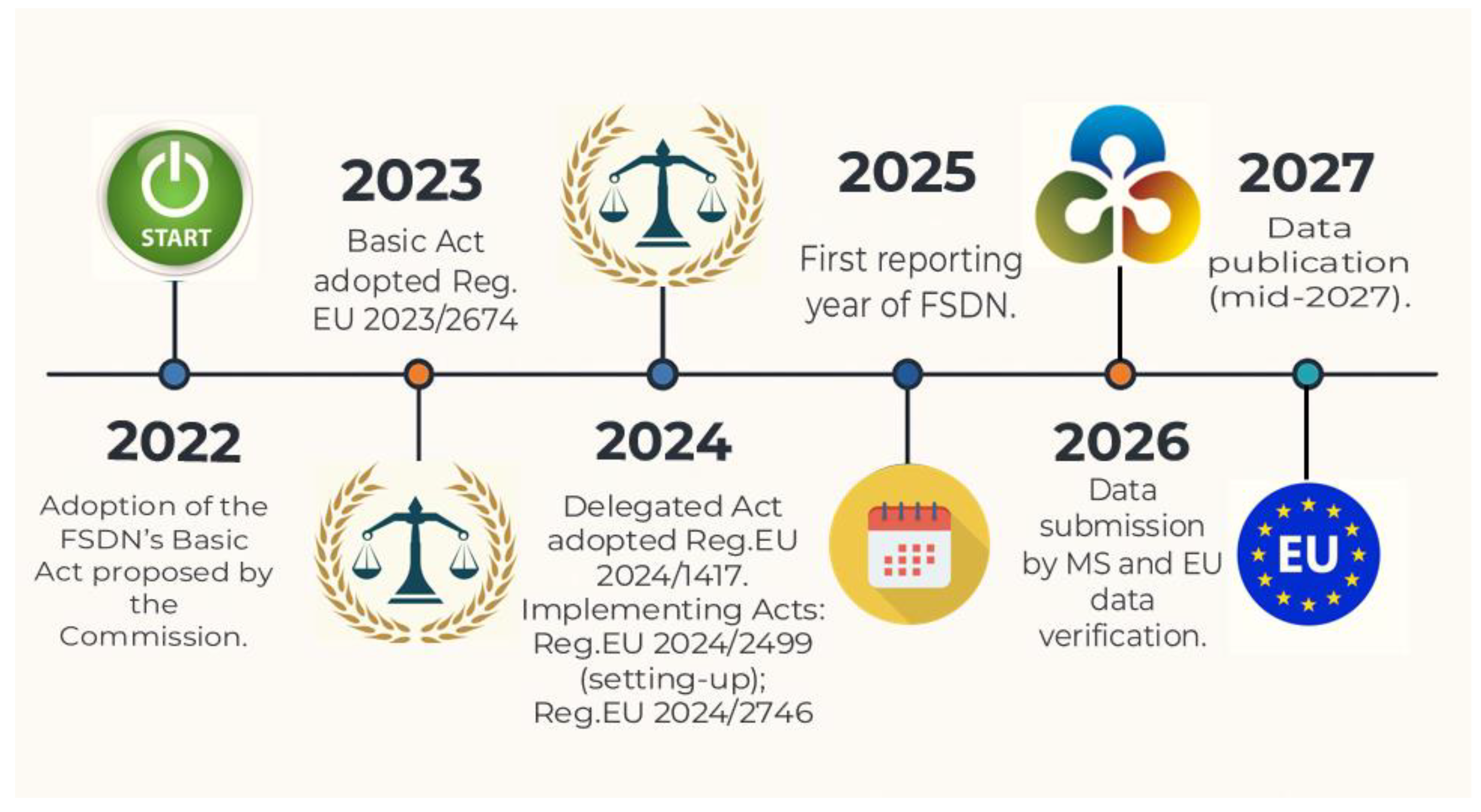

The legislative process starts in 2022 with the proposal of the Basic Act amendment, completed in 2023 with the approval (Regulation EU 2023/2674) and the preparation of the secondary legislation (

Figure 1). All the FSDN Regulations (Delegated and Implementing Regulation) have been approved in 2024. To address the efforts needed by each Member State to meet the requirements of FSDN and complete the transition, a contribution has been made available in the form of a lump sum to cover eligible costs. According to the EU Commission Implementing Regulation 2024/2499, the contribution for the setting-up period provided for Italy is around EUR 5 million.

The official start of the new FSDN data collection is expected in 2026 with the activities referring to the reporting year 2025. Data submission, verification, and publication are expected for 2026–2027.

The FSDN structure is the result of this complex consultation: compared to the first proposals, the number of variables has been considerably reduced due to the difficulties in the development of a more complex survey. In general, the initial ambition has been rescaled (in particular the social variables resulted significantly reduced).

Concerning the Italian case, compared to FADN (11,106 units), the Italian FSDN sample is reduced (9418 units): only Valle d’Aosta, the Autonomous Provinces of Trento and Bolzano, Lazio, and Molise have increased the regional sample size. Differently from other countries, the number of variables collected by the network is higher than those required by the EU: many environmental (nutrient use, soil management, water use, manure use, cultivation practices, level of mechanization, etc.) and social variables (family composition, extra-farm activities, level of education, etc.) have already been collected since 2008. Looking at the results of an investigation on the use of the Italian FADN [

13], one of the main aims seems to be the agri-environmental analysis for national and international projects. This is a very encouraging result that supports the importance of improving the survey, increasing the variables, and the details. The transition to FSDN in Italy seems less complicated than those Member States where only mandatory information is collected and where further efforts will be necessary for the data collection, validation, and data quality check.

4. Tables and New Variables Included in FSDN

The document establishing the transformation of FADN into FSDN is the Basic Act (Reg. EU 2674/2023 of 22 November 2023 amending Council Reg. EU 1217/2009, published in the Official Journal of the European Journal of 29 November 2023, L).

The first substantial novelty is provided by Article 1, stating that FSDN data shall cover the topics listed in Annex I, and is directly linked to the objectives of the new CAP (referred to in Article 5 of Regulation (EU) 2115/2021). Until now, the areas covered by the survey were not specified in a regulation: this annex explains the use of FSDN data for economic, environmental, and social scope. In addition to the economic and accounting aspects already included in FADN, the new variables shall permit the collection of information regarding the relationship between agriculture and environment (like agronomic practices, nutrient utilization and management, GHG emissions, use of antimicrobials, energy consumption, carbon farming, etc.) and some social aspects of farm management (working conditions, generational renewal, etc.).

Another important novelty is introduced by Article 4, which establishes that the Liaison Agencies have the right to access a whole series of related data sources and to use them free of charge (like the integrated management and control system, the vineyard register, the registers required for organic farming, etc.). This article obliges all the Member States to increase interoperability, carrying out all the necessary activities to match existing datasets, adapting the technology and survey methodologies.

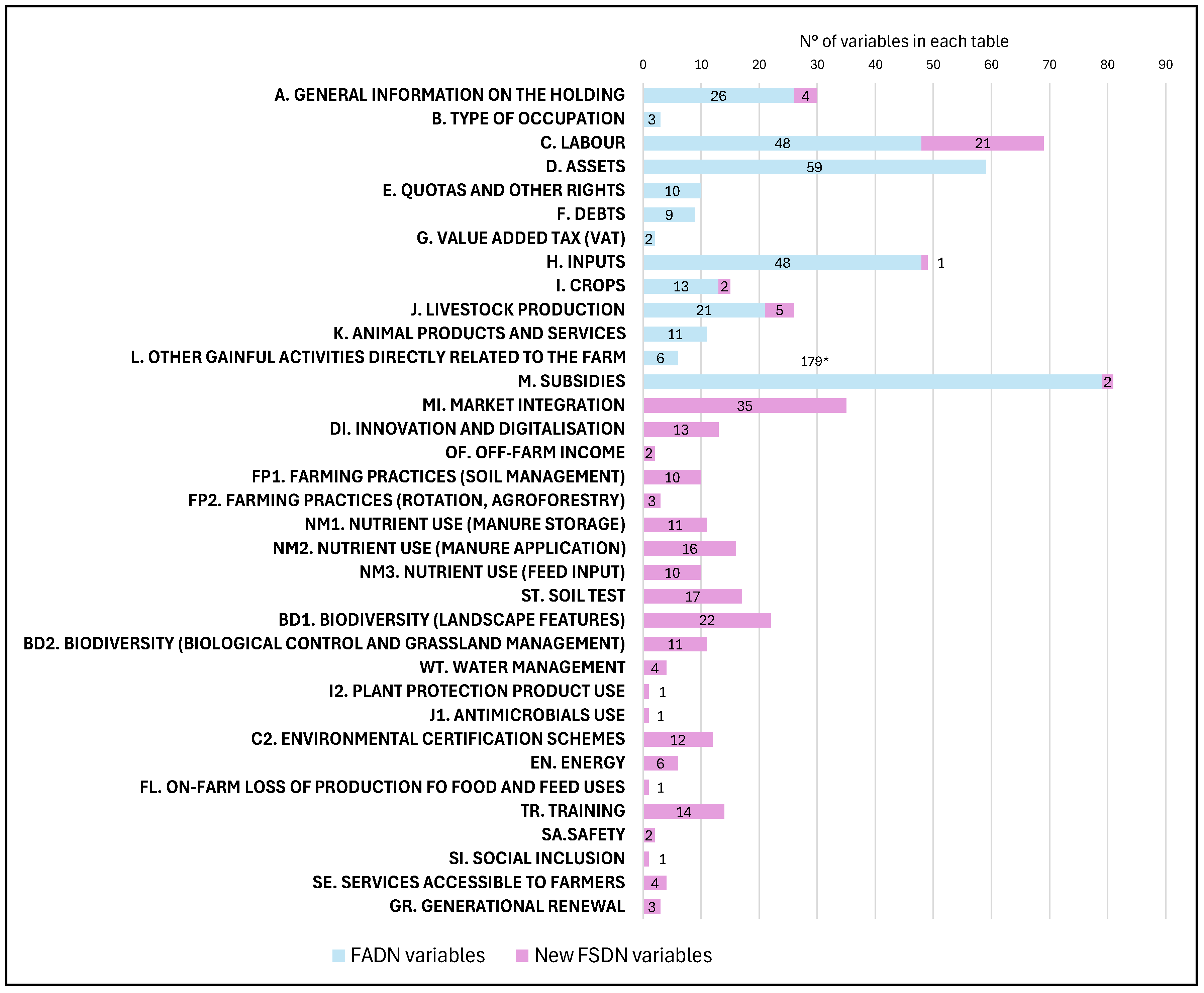

Among the implementing acts, the Reg. EU 2024/2746 of 25 October 2024 is the most important one. It introduces important methodological and operational innovations and, in Annex VIII, illustrates in detail the new tables that will be part of FSDN. In addition to the existing tables (from A to M), 22 new tables will be introduced: 14 environmental, 5 social, and 3 economic (

Figure 2). Of 669 total variables, around 35% represents new information required by FSDN. The regulation establishes a set of data that Member States must provide but also foresees the possibility of exemptions for specific variables. Some tables are optional (like the Table ST or the information on the time of first mowing in the grassland management of Table BD2). These exemptions, indicated in Annex IX, have been granted to certain countries after discussion and negotiations, underlining the gradual (and in some cases, difficult) transition to the new system and recognizing the different data collection capacities among the Member States. The first reporting year for the Tables DI, OF, FP2, NM3, BD2, WT, I2, J1, EN, FL, and TR will be 2027 (with exemption for some Member States that will start the data collection in 2028). The reason is the complexity of data collection and the need to have more time to activate procedures permitting to match the data of already existing databases. Tables I2 and J1 are the most critical: the quantity of plant protection products and antimicrobial used in the reporting year must be provided by active substance and this information is not immediately available or deducted from the documents normally checked in the FADN data gathering. The integration with other databases (like the Farm Register or the Digital Farm Logbook) could be a solution: in several Member States, the quantity of phytosanitary inputs and antimicrobial inputs are already collected, but the estimation of the active substance, although helpful, is complicated.

Important information is collected by Tables NM on manure storage facilities (NM1), manure application techniques (NM2), and feed input (NM3). The reason why the related variables have been added is strictly connected with the emission estimation in the FSDN framework. One of the aims of DG AGRI is the development of a prototype for GHG emission calculations for all the farms included in FSDN. The structure, logic, and assumption used in the emission estimation (based on IPCC approach) are still under discussion with the Member States, in particular, with those who have experienced this kind of model. FADN data has been used for GHG emission estimation at farm level in France [

14], Italy [

15,

16], Lithuania [

17], Greece [

18,

19], Germany [

20], and Poland [

21,

22]. The Italian model follows the IPCC methodology for estimating GHG emissions at farm level (ICAAI model): the carbon footprint is calculated for around 120,000 observations, starting from 2014. Emissions are calculated for the categories of livestock and crop production, fertilizers, energy, and land use change. The model includes only the emissions of the production phase but the more detailed information coming from the Italian FADN makes possible the consideration of specific inputs (like the quantity of energy) otherwise not counted at EU level. Details on the manure management system of solid manure and liquid manure/slurry and on the incorporation of manure will permit the refinement of the model and a more precise estimation of GHG emissions that can be linked with other farm indicators to evaluate emission intensity at farm level.

Biodiversity aspects are collected in Tables BD: BD1 concerns the type of landscape features (terraces, hedgerows, patches, ditches, streams, wetlands, stonewalls, etc.); BD2 is inherent in the biological control (use of microbials, macrobials, semiochemicals) and the grassland management (the area mowed, reseeds, ploughed). This set of variables will permit to analyze the farm agrobiodiversity and, combined with the farming practices (tillage management, soil cover, organic fertilization, application of lime in Table FP1) will give the possibility to highlight the relationship between farm and environmental characteristics [

23]. The collection of specific information regarding farming practices can also feed the analysis on carbon farming: disposing of this data permits the identification of those farming types more oriented towards carbon sequestration. The Italian FADN partially collects this information that has been used in research projects (Life C-Farms) to identify a sample of carbon-oriented farms, their potential in the carbon removals, and the economic sustainability of the certification [

24].

Compared to the first proposal, the social aspects of farming were resized and simplified. Information on training, safety, social inclusion, services accessible to farmers, and generational renewal are the specific tables covering social topics, together with some gender information in the table of labour. Information like the providers of training and advice, the facilities provided by the holder to the workers (in terms of accommodation, meals, transport, etc.), the presence of workers with disabilities, and the spatial accessibility to services (like primary schools, kindergarten, hospitals, etc.) have been deleted in the final version of the regulation. It can therefore be stated that the social area remains not completely covered in FSDN: the major concerns were for the confidential nature of new information and the possibility of having a high number of refuse farms.

5. Opportunities for the Research and Future Challenges of FSDN

The enlargement of the FADN represents an evolution consistent with what has been widely discussed in scientific literature: in recent years, numerous studies have highlighted the need to go beyond a purely economic evaluation of company performance, promoting a holistic approach that considers environmental and social aspects [

25,

26,

27]. Past studies based on the FADN database have proved extremely valuable for informing agricultural policy design and evaluation. However, as the CAP has progressively incorporated ambitious environmental and social objectives, the need for a broader and more balanced evidence base has become evident and necessary. The future of CAP 2028–2034 will strengthen the sustainability and resilience of European farming, with a more targeted approach to key environmental and climate priorities. Climate mitigation and adaptation, soil and water protection, biodiversity, animal welfare, and the growth of organic and low-impact farming systems will be the core of the future CAP and farmers will be compensated for the costs of greener farming methods, agro-ecological models, and new agri-environmental and climate actions (AECA). The transition from FADN to FSDN is one piece of the future framework. All the aspects of sustainability have been interested by the reform.

The economic field of FSDN includes classic aspects of business management, such as assets, investments, debts, and credits, but expands to new areas such as risk management, innovation, and market integration (i.e., different buyers, contract type, price arrangement), providing a more complete picture of information useful for a global analysis of the competitiveness of farms. Economic indicators historically focused on productivity, profitability, and use of production factors, are now increasingly interpreted under the lens of economic resilience and financial sustainability in the long term and also in relation to the related agricultural policy instruments [

27].

The environmental area of FSDN is the core of the reform and it integrates aspects related to the sustainable management of natural resources with issues regarding the environmental impacts of agricultural activities. These dimensions reflect a structural convergence with the principles and strategic objectives of the European Green Deal, fostering evolution towards a more resilient, sustainable agricultural model, capable of preserving natural resources and ensuring food security in the long term. In this regard, research has developed numerous multidimensional frameworks to assess the impact of agriculture on soil, water, air, biodiversity, and climate [

28,

29]. Greenhouse gas emissions, water consumption and energy balance are widely recognized as international parameters for assessing the environmental sustainability of agricultural systems [

30,

31] and constitute the methodological basis for tools for monitoring global environmental goals or assessing the impact of policy instruments, like carbon taxation [

32]. FSDN will collect a broad spectrum of environmental variables to support targeted studies and analysis on agronomic farming practices and their importance in mitigating climate change, improving biodiversity, and ensuring sustainable resource management. Furthermore, the FSDN’s collection of data on the use of plant protection products and antimicrobials offers a direct and invaluable contribution to public health and food safety policies. By cross-referencing this information with national databases, authorities can track the use of these substances and assess their potential impact on human health, aligning with the Farm to Fork strategy.

The FSDN addresses the historical underrepresentation of social data by collecting information on labour conditions, social inclusion, training, and generational renewal. The relevance of these aspects has been underlined in the literature as a necessary condition for the assessment of the systemic sustainability of the farm [

33,

34,

35,

36,

37]: although scaled down compared to the initial ambitions mainly because confidentiality issues, their inclusion therefore represents a significant methodological innovation, but also a challenge in terms of standardization and operationality. In fact, it is widely recognized that social sustainability is based on conceptual constructions that are not always quantifiable through traditional technical methodologies [

38,

39]. One of the most important pieces of information collected in FSDN concerns the generational renewal: an indication is to be given about the year when the current holder took over the farm, if the transmission comes from a family or non-family member, and if there is a plan for the future transmission (to a family or non-family member or for rent). Differently from the EU requirements, the Italian FADN gathers information regarding the farm family members and some analysis underlined the importance to have this data to also identify the attractiveness of certain areas or how different business models impact farm succession.

A key benefit of FSDN’s design is the interoperability mentioned, meaning the capacity to share and use data across different systems. This feature enables integration with other European platforms, generating synergies that significantly strengthen agricultural research. For example, linking farm-level FSDN data with additional sources allows more precise evaluations of CAP, making it possible to connect farm practices with broader environmental trends, including air and water scarcity [

40]. Interoperability also fosters a more holistic perspective on food systems, essential for addressing systemic challenges like climate change and food security. Regarding this, CREA-PB is working to integrate FSDN with the Farm Register and the Digital Farm Logbook (essential tool for the computerized recording of phytosanitary treatments and fertilization practices). The interoperability between FSDN and the National Agricultural Information System (SIAN) is crucial to increase the quality of data, reducing the risk of errors and the administrative burden for data collectors and farmers.

The transition to FSDN presents significant opportunities, but its successful implementation hinges overcoming substantial operational and technical challenges. This reform requires a fundamental overhaul of existing infrastructure, procedures, and human resources. FSDN’s expanded dataset requires more robust systems for data collection, validation, and storage. This demands harmonized data formats and a secure, efficient data exchange architecture should be created. The IT staff of CREA-PB are developing a new software for FSDN (GAIAweb) and planning significant investments in the training and continuous professional development of data operators. These individuals must be equipped with the skills to accurately collect, validate, and manage new, more complex data, ensuring its quality and consistency across the network. Finally, ensuring farmer participation remains a critical challenge. The participation is still voluntary, and there is a critical need to bring farmers on board: the success of the FSDN depends on the willingness of farmers to provide news, often comprising sensitive information. Member States must find effective ways to encourage participation. The incentive plan for Italy is based on the increase in accounting knowledge for farmers (a new scheme of the Financial Statement with new environmental and social indicators like, for example, an estimation of GHG emissions), the improvement in the already existing benchmarking instruments (like the Farm Dashboard available for each farm), and the improvement in advice, taking into consideration the whole dimension of sustainability.

6. Conclusions

Since its birth and for 60 years, FADN has been the basis for economic and accounting information, aiming at the analysis of the impacts of European agricultural policy interventions. The evolution of policies and the inclusion of environmental and social elements in the evaluation of global farm sustainability have led to the conversion of FADN into FSDN. The new network will support evidence-based policy decisions, contributing to the future EU benchmarking system and helping farmers in the adoption of more sustainable farming practices as required by the EU strategies. The central component of the EU Green Deal is the Farm to Fork strategy, which has aims related to the creation of a sustainable and healthy food system by transforming the entire food chain from farm to consumer, focusing on reducing pesticides, increasing organic farming, promoting healthy diets and improving animal welfare, and supporting environmentally friendly practices. These initiatives have been crucial in the conversion of FADN to FSDN: the new variables will permit the calculation of new indicators for the future policies’ impact analysis even if, compared to the initial ambition, the final framework result is resized (especially for the social aspects). Due to the difficulties in the implementation of such a complex survey in all the Member States, some initial requests have not been accepted or have become optional. The granularity of the data collection is another important issue: a big part of the new variables refers to the farm, while for specific analysis (like, for example, the effects of certain farming practices), data must be referred at the crop or livestock category level. With this respect, the Italian system offers the great opportunity to have data collected at crop level including the value of the production and the specific costs. The Liaison Agency is working to integrate the system with the Farm Register and the Digital Farm Logbook to strengthen the level of detail.

The multidimensional approach adopted by the new network will also potentially promote greater interoperability between different administrative databases (agriculture, environment, labour, public health), allowing for more robust analyses, based on harmonized and comparable data. Integration with other sources could fill the gap represented by the social dimension of the core FADN that appears inadequate for a deep analysis of social themes. Arguments like the farmer and worker welfare, the services of the area, the interactions with local economy, etc., have been excluded during the negotiation for confidentiality issues and for the difficulties in the validation (often subjective). This approach reinforces the role of the network as an evidence-based tool for the ex-ante and ex-post evaluation of European policies. In Italy, FADN/FSDN data are used by the National Rural Network for the draft of the CAP Strategic Plan, for monitoring and evaluation purposes, and it is an important source of information for the justification of payments of rural development policies.

However, the full implementation of the new network will not be cost-free both for the expansion of the dataset and the complexity of the data collection. The transition will require significant investments in digital infrastructure, in training and updating the operators, in the simplification of administrative procedures, and the shared definition of collection and analysis methodologies, in order to ensure homogeneity in the quality and use of data between Member States. The success of dataset implementation will depend on the ability to make data effectively interoperable, timely, accessible, and functional both for public policy development and for continuous improvement, with a view of evidence-based sustainability issues. Providing data to the scientific community and public research plays an important role in the Italian system and this fosters a more inclusive and shared agricultural governance, in line with the principle of knowledge co-creation supported by the European Commission.

It will be important to encourage farmers to participate. There are many tools to achieve this scope. Incentives for participation could come from improved advice based on the data provided, benchmarking activities, and continuing professional training. Italy has adopted the latter line, following what it has achieved so far in terms of tools made available to farmers: in addition to the delivery of the statutory Financial Statement to those who are part of the survey, there are specific tools for the exclusive use of farmers (farm dashboard) that allow the implementation of benchmarking and monitoring activities for their data.

In conclusion, FSDN represents a historic step towards evidence-based sustainable agriculture in Europe, but its effective analytical potential will only materialize if Member States and the Commission strengthen participation incentives, accelerate harmonization, and secure long-term funding. Until these conditions are met, FSDN should be treated as a powerful but still maturing instrument of which the implementation process remains delicate. Successful implementation will therefore require continuous monitoring of the actual analytical usefulness of the new variables, ideally through structured feedback mechanisms involving the full community of FSDN data users (researchers, policymakers, and advisory services). Any future refinement or further expansion of the dataset will inevitably need to be weighed against the significant financial and organizational costs associated with the transition [

9].

The official launch of the FSDN is expected in 2026 with the collection of data referring to the 2025 accounting year. It is hoped that it will be possible to use the results of the survey to assess the effectiveness of the interventions planned for the CAP 2023–2027 and the achievement of the targets set out in the common monitoring and evaluation framework.

_Li.png)