4.1. Prediction-Enhanced A-ECMS

The energy management strategy (EMS) is the core of the powertrain system for fuel cell commercial vehicles, directly determining the vehicle’s hydrogen economy and system synergy efficiency [

31]. As reviewed by Khalatbarisoltani et al. [

32], the EMS can significantly improve the hydrogen economy and enhance the system synergy efficiency (e.g., extending component lifespan and reducing powertrain fluctuations) by optimizing the power distribution between the fuel cell and energy storage system, with mainstream technical approaches categorized into the Equivalent Consumption Minimization Strategy (ECMS) and its improved variants, as well as Model Predictive Control (MPC). Firstly, the traditional ECMS achieves instantaneous optimization by equating battery charge-discharge energy to hydrogen consumption via a fixed equivalence factor, yet it struggles to adapt to complex dynamic working conditions—a study by He et al. [

33] on fuel cell buses confirms that under typical urban dynamic scenarios like start–stop and congestion, the traditional ECMS consumes 6.2% more hydrogen than the Adaptive Equivalent Consumption Minimization Strategy (A-ECMS), directly highlighting the limitations of fixed-factor strategies. Secondly, while A-ECMS balances the real-time performance and optimization effect by dynamically adjusting the equivalence factor based on current states such as SOC, it lags in responding to future working conditions due to its sole reliance on current state feedback. Meanwhile, MPC, grounded in the receding horizon optimization concept, solves the optimal control sequence by predicting system behavior within a finite future time domain, offering a high optimization accuracy but facing a heavy computational burden from complex online solving, which makes it hard to meet the millisecond-level real-time control demands of commercial vehicles.

The traditional Adaptive Equivalent Consumption Minimization Strategy (A-ECMS) relies solely on instantaneous state feedback, unable to predict future operational trends or anticipate subsequent changes in working conditions [

34]. This results in suboptimal control decisions and a lag in energy management, ultimately leading to higher hydrogen consumption. To address that issue, this paper proposes an improved Predictive Equivalent Consumption Minimization Strategy (P-ECMS). This strategy retains the core framework of real-time equivalent factor optimization in A-ECMS while incorporating short-term vehicle speed prediction capabilities. By using short-term predicted vehicle speed data to obtain the future short-term operational trend, this trend is then incorporated into the equivalent factor regulation formula to correct the equivalent factor, forming an optimization approach that can not only perceive the current state but also predict future working conditions. This enables decisions to be both responsive and forward-looking. Considering that vehicle speed has a significant impact on power demand and energy consumption, this strategy divides driving scenarios into low-speed, medium-speed, and high-speed intervals. Within each interval, the equivalent factor is adjusted based on changes in short-term predicted vehicle speed, improving the matching degree of energy distribution and subsequent driving conditions. Ultimately, under complex and variable driving conditions, power distribution decisions become more reasonable and adaptable, while also enhancing hydrogen consumption economy and overall system efficiency.

- ➀

SOC Current Integration Update Formula.

The real-time state of the power battery’s SOC is the basis for strategy decision-making, and its update is based on the current integration model, as shown in Equation (18):

In Equation (18), represents the battery charging/discharging current, and denotes the rated battery capacity. This equation provides real-time feedback on SOC changes, serving as the current state basis for subsequent equivalent factor adjustment. The equivalent factor is the core regulatory parameter for power distribution. The traditional Adaptive Equivalent Consumption Minimization Strategy (A-ECMS) only relies on single-dimensional adjustment of SOC deviation, resulting in a lag in response to dynamic changes in operating conditions.

- ➁

Static Segmented Equivalent Factor Formula Based on Vehicle Speed Intervals.

The equivalent factor is a core regulatory parameter for power distribution. The traditional Adaptive Equivalent Consumption Minimization Strategy (A-ECMS) only relies on single-dimensional adjustment of state-of-charge (SOC) deviation, resulting in a lag when responding to dynamic changes in operating conditions. In the field of fuel cell vehicle (FCV) energy management, Gao et al. [

35] in 2008, for fuel cell buses, divided the intervals of demand power and SOC using fuzzy logic, preset power distribution rules for each interval, and thereby enabled the fuel cell to operate in a high-efficiency region, which effectively reduced the equivalent hydrogen consumption. This rule-based interval regulation strategy, due to its clear logic and ease of engineering, has become a classic early ECMS scheme. By adopting such a method, fixed equivalent factor benchmarks are preset by dividing low-speed, medium-speed, and high-speed intervals to adapt to energy demands at different vehicle speeds and avoid operation in low-efficiency zones. Owing to its clear logic and ease of implementation, it has been widely applied, and based on this, the three-segment formula shown in Equation (19) below is designed:

Here, is a static segmented equivalent factor, while , , and correspond to the segmented values of the equivalent factor in low-, medium-, and high-speed intervals, respectively. By adjusting the coefficient of the initial optimal value of the equivalent factor, differentiated power allocation under different vehicle speeds can be achieved. The initial optimal value of the equivalent factor is derived from the global optimization of dynamic programming. In typical scenarios with gentle operating conditions and no state-of-charge (SOC) constraints, its optimal fixed value is 1.2. Focusing on fuel cell output as the core optimization target, this paper designs three correction coefficients (low, medium, high) for fine-tuning based on to adapt to different vehicle speed requirements.

This strategy exhibits clear static characteristics due to its segmented fixed-value feature: although it can adapt to basic operating conditions through three vehicle speed intervals, it is essentially interval switching of fixed values and cannot achieve continuous dynamic adjustment of the equivalent factor. The core limitation of this segmented step-type regulation is that it struggles to respond to subtle fluctuations in battery SOC and gradual changes in vehicle speed.

Relevant research clearly points out that static segmented strategies lack adaptability to dynamic operating conditions: their fixed-value switching mode tends to cause energy allocation lag under complex operating conditions, which directly leads to a reduced proportion of fuel cell operation in the high-efficiency range, increased efficiency fluctuations, difficulty in maintaining the power battery SOC within the target range, and even the risk of SOC runaway [

36].

Therefore, there is an urgent need to introduce a dynamic adaptive mechanism for improvement.

- ➂

Segmented Multi-Factor Control Strategy.

To achieve the unification of reliability and dynamic adaptability, building on the aforementioned strategy, this paper integrates the static three-segment benchmark with the two-dimensional logic of “SOC deviation + vehicle operation trend” to construct a dynamic equivalent factor model, as shown in Equation (20) below:

In Equation (20),

denotes the fused equivalent factor, where

(“seg” denotes segment) inherits the core structure of the static three-segment configuration. The reference values for each speed segment and the corresponding parameters—

,

,

, and

—are provided in

Table 7 to align with the distinct power demand characteristics across different velocity ranges. Specifically,

and

represent the weight and quantization coefficient for the state-of-charge (SOC) deviation term, while

and

correspond to those for the vehicle operation trend term. The operation trend is quantified by the difference between the predicted vehicle speed

three seconds ahead and the current speed

:

A larger difference indicates a more pronounced trend change, whereas a smaller difference reflects a smoother trend. A small constant ε = 10

−6 is introduced to ensure numerical stability. Within the ECMS framework, a higher λ value increases the fuel cell (FC) output contribution—thereby suppressing battery discharge—while a lower λ shifts more power demand onto the power battery. The proposed model incorporates a two-dimensional correction mechanism that dynamically adjusts λ based on the current speed interval: for the low-speed range

, representative of urban driving with frequent accelerations and decelerations, operational trends exhibit greater fluctuations, and the resulting large overall differences increase the denominator in the trend term, leading to a reduced

and thus greater reliance on the battery for power delivery; for the medium-speed range (40–80 km/h), driving behavior tends to be more stable with smaller speed variations, which reduces the denominator, thereby increasing

and enhancing FC utilization; for the high-speed range (80 ≤ v < 120 km/h), operational trends are consistently smooth with minimal variation, and the baseline

is set higher, so these factors jointly result in the maximum

across all intervals, reducing the power battery’s load and preventing excessive discharge. By integrating reference anchoring with two-dimensional correction, the model transforms the traditionally stepwise equivalent factor into a smoothly adaptive parameter, effectively balancing empirical engineering design with precise adaptation to real-world driving conditions. The specific parameter settings for each segment are detailed in

Table 7.

- ➃

Dynamic Correction Formula for Fuel Cell Output Proportion.

Based on the aforementioned equivalent factor regulation strategy, this section determines the real-time power output proportion of the fuel cell (FC) using Equations (21) and (22), where this proportion is dynamically adjusted by the equivalent factor. These equations are presented as follows:

Here, denotes the baseline FC power proportion corresponding to the three vehicle speed intervals—low speed , medium speed (40–80 km/h), and high speed (80 ≤ v < 120 km/h)—which can be calculated via Equation (21) using the tabulated parameter data; the constant 0.3 acts as an adjustment coefficient to limit the magnitude of single-step variation in the power distribution ratio, while γ(t) represents the instantaneous proportion of the FC’s contribution to the total power demand at time t. For the dynamic adjustment driven by the equivalent factor: when > s0 (e.g., under low state-of-charge (SOC) conditions), the correction term becomes positive, raising the FC’s output proportion above the baseline to alleviate the discharge burden on the traction battery; conversely, when λfusion < (e.g., during high-speed acceleration), the correction term turns negative, reducing the FC’s power allocation below the baseline—this enables the traction battery to supply a larger portion of the required power, thus preventing the FC from entering the low-efficiency region due to excessive power output.

- ➄

Vehicle’s Total Power Demand.

The total power demand of the vehicle is the sum of driving power and auxiliary system power, which serves as the benchmark for power distribution. As shown in Equation (23) below,

In Equation (23), is the power demand of the driving motor, calculated based on the current vehicle speed and road resistance, and is the power consumption of on-board equipment.

- ➅

Formula for Fuel Cell Power and Hydrogen Consumption Rate.

Fuel cell power is determined by the product of total power demand and output proportion, the corresponding formulas are shown below:

Among the symbols, is the total output power of the fuel cell. The output proportion γ(t) integrates the base proportion of segmented vehicle speed intervals, anchors the empirical distribution benchmark under different operating conditions, and realizes a precise response to battery SOC deviation and the vehicle speed prediction trend through dynamic correction of the two-dimensional adaptive equivalent factor.

- ➆

Calculation of the Equivalent Instantaneous Hydrogen Consumption Rate of the Power Battery.

Due to the relatively complex instantaneous energy flow direction of the power battery—unlike fuel cells that can only output energy rather than input it—coupled with the fact that the net energy from regenerative braking is an external input, it is necessary to make distinctions during the conversion process. Specifically, the conversion methods should be determined based on the source of different energy flows: for example, the process of the fuel cell charging the power battery, the discharge process of the power battery itself, and the process of regenerative braking charging the power battery. Each scenario needs to be considered separately to determine whether it increases or reduces the equivalent hydrogen consumption. By accumulating the equivalent instantaneous hydrogen consumption of the power battery, its total equivalent hydrogen consumption rate can be obtained; adding this result to the direct hydrogen consumption rate yields the total equivalent hydrogen consumption rate of the system, which is suitable for the comprehensive quantitative analysis of energy efficiency. The calculation formulas for the equivalent instantaneous hydrogen consumption rate of the power battery are shown below:

Equation (26) applies to the discharge condition of the power battery, where is the equivalent hydrogen consumption rate during power battery discharge. In Equation (27), is the power for charging the power battery, and is the equivalent hydrogen consumption rate when the fuel cell charges the power battery. Equation (28) corresponds to the scenario where braking power generation charges the battery, with being the motor’s power generation and being the actually recovered instantaneous energy. Here, is the lower heating value of hydrogen, and the efficiency is not a fixed value; it varies according to actual conditions, such as temperature, state of charge, and voltage.

- ➇

Formula for Instantaneous Equivalent Hydrogen Consumption

The strategy takes the minimization of equivalent hydrogen consumption as the optimization objective and uniformly measures the energy consumption of dual power sources through the objective function, as shown in Equation (28) below:

In Equation (29), this formula represents the instantaneous hydrogen consumption rate, which accounts for the instantaneous equivalent hydrogen consumption rate. The equivalent factor at each moment is fixed, so the same coefficient is multiplied regardless of charging or discharging. is the real-time hydrogen consumption rate of the fuel cell, is the equivalent hydrogen consumption rate of the battery, and (t) is the corresponding equivalent factor. With the core objective of minimizing this equivalent hydrogen consumption, it also needs to satisfy hardware constraints such as the fuel cell power range, power change rate, and battery charge–discharge power.

This strategy is based on real-time state perception. Firstly, it collects the current vehicle speed, power battery SOC, and driving power demand, and it inputs them into the SSA-LSTM model to generate the predicted vehicle speed for the next 3 s, providing a forward-looking operating condition basis for energy distribution. Based on the current SOC and predicted vehicle speed, the adaptive equivalent factor integrating two-dimensional characteristics is calculated through Equation (20). This factor not only reflects the regulation demand of SOC deviation on battery charging and discharging but also relates the adaptability of future vehicle speed trends to the high-efficiency interval of the fuel cell. Then, this equivalent factor is substituted into Equation (22) to solve for the fuel cell output power proportion γ(t). Combined with the total power demand of the vehicle, the real-time output power of the fuel cell is determined through Equations (24) and (25), and the power of the power battery is determined according to the energy balance relationship. At the same time, Equation (29) is strictly taken as the core optimization objective, comprehensively calculating the direct hydrogen consumption rate of the fuel cell, the equivalent hydrogen consumption compensation term for power battery charging and discharging, and the hydrogen consumption deduction term for braking recovered energy, so as to minimize the equivalent hydrogen consumption under full operating conditions. After executing the power command, the power battery SOC is updated through the current integral model in Equation (18) and fed back to the next control cycle, forming a complete logical chain of “state perception—predictive foresight—factor calculation—power distribution—hydrogen consumption optimization—SOC closed loop”. This enables all formulas to work synergistically in the strategy, ultimately achieving the economic efficiency and balance of energy management, The entire energy cycle process corresponding to this logical chain is shown in

Figure 7 4.2. Comparison of Simulation Results

Figure 8 shows the SOC (battery state of charge) variation characteristics of the dynamic programming (DP) strategy, the Improved Adaptive Equivalent Consumption Minimization Strategy (P-ECMS), and the basic A-ECMS strategy under two driving cycles. Subfigure (a) corresponds to the C-WTVC (China World Transient Vehicle Cycle, China’s heavy-duty commercial vehicle transient cycle), and Subfigure (b) corresponds to the NREL2VAIL (National Renewable Energy Laboratory 2 Vehicle Advanced Investigation Laboratory, the U.S. National Renewable Energy Laboratory 2-type vehicle advanced research cycle), with a driving distance of 42.5 km. Under both cycles, the DP strategy achieves the best SOC stability, with variances as low as 8.08 × 10

−6 and 1.81 × 10

−6, respectively. The SOC fluctuation of P-ECMS remains within a controllable range, maintaining good battery charge stability in both short-cycle and long-distance operations. In contrast, the basic A-ECMS exhibits relatively more significant SOC fluctuations in the later stage.

These two distinct driving cycles are selected for testing primarily to verify the generalization and adaptability of the strategies. The results show that all three strategies meet the SOC range control requirements. Among them, the DP strategy delivers the best stability performance, while P-ECMS (an improved strategy based on A-ECMS) maintains good SOC stability across different driving scenarios. This fully demonstrates the effectiveness of the improvements made to the A-ECMS strategy.

Figure 9 presents a detailed power distribution diagram for the energy management strategy of a fuel cell commercial vehicle, offering a clear visualization of the dynamic interaction between multiple energy sources. The various curves in the figure correspond to key energy flows, including total power demand, driving demand, net output of the fuel cell, traction battery power, and auxiliary system power. From the perspective of energy supply and demand logic, the total power on the demand side consists of two components: first, the driving demand power required for vehicle operation and overcoming resistance; second, the power needed to sustain on-board electrical equipment. On the supply side, the fuel cell acts as the core energy source (its output power is represented by the blue curve), while the traction battery (green curve) plays a role in peak shaving and valley filling. When total demand exceeds the fuel cell’s output, the traction battery discharges to supplement energy; when the fuel cell produces surplus power, the traction battery receives this excess for charging. The charging status of the traction battery is as shown in

Figure 10.

It should be noted that when the total demand is negative, the system enters a braking and deceleration process. The traction battery limiting its maximum charging power is not merely about restricting the motor’s regenerative capacity; rather, it stems from considerations of balancing braking safety and energy recovery. After all, in engineering practice, it is impossible for the motor to bear all braking torque alone—part of the required braking force must be provided by mechanical braking. Overall, through the dynamic matching of the fuel cell’s net output and the traction battery’s power, the system ensures that their sum remains balanced with the total demand power. This clearly demonstrates the energy collaboration characteristics of the multi-energy system under dynamic operating conditions, as well as the actual impact of the traction battery’s charging and discharging constraints on energy flow.

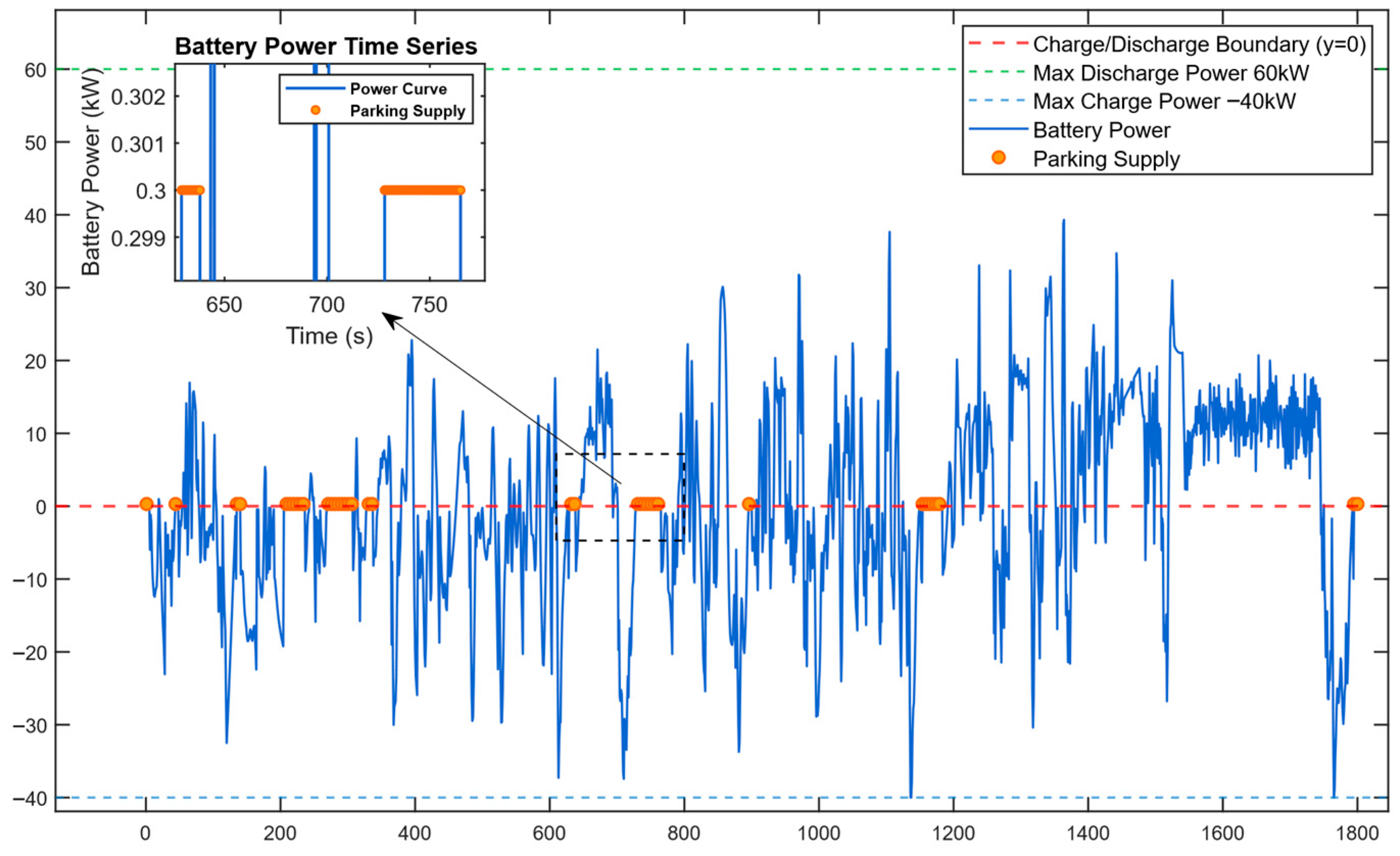

Considering the characteristics of power change rate and fluctuation frequency, in low-power operating conditions—such as when the vehicle is idling at intersections (as illustrated in

Figure 11)—the traction battery is only required to support minor auxiliary loads, including vehicle lighting and air conditioning systems. During such periods, the fuel cell system is deactivated, and the traction battery operates independently to supply the necessary power. This approach not only conforms to the dynamic response capabilities of the battery in handling high-frequency, low-energy micro-power fluctuations—where small-amplitude variations can adequately meet load demands with a negligible impact on battery cycle life—but also prevents the fuel cell from operating in its inefficient low-load region. By exploiting the traction battery’s superior adaptability to low-frequency, low-amplitude, and transient power demands, the proposed strategy enhances overall energy utilization efficiency and effectively reduces equivalent hydrogen consumption. This operational logic clearly illustrates the synergistic advantages inherent in the parallel hybrid architecture: the fuel cell is optimized for stable, continuous power delivery to meet low-frequency, high-energy demands, whereas the traction battery provides agile, responsive support for high-frequency, low-power transients.

Figure 12 illustrates the operation process of the energy management strategy for fuel cell commercial vehicles via five subfigures.

Subfigure (a) shows the vehicle speed variation, which serves as the input condition for the operating cycle; Subfigure (b) demonstrates the power distribution logic, where the total demand power includes the vehicle driving power demand and auxiliary system power demand—as the main energy source, the fuel cell primarily operates in the 15–40 kW efficient range (where its energy efficiency is relatively high), while the power battery supplements or stores energy through “peak shaving and valley filling” to cooperate with the fuel cell in meeting the total demand; Subfigure (c) presents the dynamic changes in the adaptive equivalent factor, whose control logic first divides vehicle speed into three intervals (low, medium, high) with corresponding base values for the fuel cell output proportion (highest at high speed, followed by medium speed, lowest at low speed)—the equivalent factor does not independently regulate power but performs dynamic fine-tuning on the base proportion of the corresponding interval, so it fluctuates but does not rise significantly during the high-speed stage and remains within the preset range to adapt to operating conditions; Subfigure (d) shows that the battery SOC stays stable at medium and low speeds but decreases at high speeds due to the higher power demand and the lack of regenerative braking energy recovery; finally, Subfigure (e) verifies the model’s energy conservation accuracy, with the numerical calculation error in the order of 10−15 kW, indicating that the model strictly complies with energy conservation logic at the theoretical level.

- ➀

Linear Correlation Formula for Fuel Cell Power and Hydrogen Consumption Rate.

As can be seen from

Figure 13, the real-time hydrogen consumption rate

of the fuel cell has a linear correlation with its output power

, and its linear formula is as follows:

In Equation (30), is the FC power-hydrogen consumption slope, with the unit of g/(kW·h), and is the fuel cell idle hydrogen consumption, with the unit of g/h.

Figure 13 shows the distribution of the fuel cell’s operating characteristics. The redder the color of the scattered points, the higher the density of the operating points. Its operating points are mainly concentrated in the 15–40 kW range, which is the high-efficiency zone in the figure, accounting for 63.0%, corresponding to an average power of 22.2 kW and an average hydrogen consumption of 320.2 mg/s. The operating point density is lower in the intervals below 15 kW or above 40 kW, indicating that the adopted energy management strategy enables the fuel cell to operate more in the high-efficiency zone, thereby enhancing its energy utilization efficiency.

As shown in

Figure 14, the DP strategy, a theoretical benchmark, results in high-frequency and large-amplitude oscillations in the fuel cell’s output power, with abrupt large-amplitude power jumps occurring instantaneously. Such aggressive power fluctuations are only feasible under ideal conditions and cannot be realized in practical applications, failing to meet the operational requirements of commercial vehicles. Thus, it can only serve as a theoretical reference for strategy optimization.

The traditional A-ECMS strategy lacks future operating condition prediction capability and relies solely on real-time feedback to adjust the equivalent factor. This causes frequent high-frequency and large-amplitude jumps in the fuel cell’s output power. When the vehicle undergoes abrupt changes in operating states (e.g., sudden acceleration or sharp deceleration), the fuel cell power exhibits immediate sharp rises and drops. Such unstable power output prevents the fuel cell from stably operating in its high-efficiency region, forcing it to operate in the low-efficiency range for longer periods. Consequently, this not only increases hydrogen consumption but also leads to the unsatisfactory control performance of the strategy.

To address the issue of high-frequency and large-amplitude jumps in fuel cell power under traditional strategies, the upper limit of the power change rate is first restricted to prevent sudden large power changes. On this basis, the P-ECMS strategy dynamically adjusts the equivalent factor based on vehicle speed prediction, further making the fuel cell power output more stable and the distribution more in line with changes in working conditions. In actual operation, its power is strongly correlated with vehicle speed, with smooth fluctuations and no random jumps, and can be stably maintained in the efficient working area. Compared with the dense and high-frequency jumps in

Figure 14b, the fuel cell power curve under this strategy (as shown in

Figure 15) fluctuates smoothly, with the fluctuation frequency significantly reduced. Although its hydrogen consumption is slightly higher than that of the DP strategy, due to stable operation in the efficient zone, the equivalent hydrogen consumption is much lower than that of the traditional A-ECMS, with outstanding energy-saving effects and an overall better performance.

Table 8 and

Figure 16 present the equivalent hydrogen consumption and battery state-of-charge (SOC) data for the three strategies under the C-WTVC and NREL2VAIL conditions—all are initialized with an SOC of 0.60, but their performances differ significantly. The traditional A-ECMS exhibits 498.6 g of equivalent hydrogen consumption under C-WTVC, 10.5% higher than that of dynamic programming (DP, 451.2 g); under NREL2VAIL, its consumption reaches 1114.4 g, 13.2% higher than DP’s 984.5 g, alongside the fastest growth rate and the largest final SOC deviation from the initial value.

In contrast, the P-ECMS shows 480.6 g (6.5% higher than DP) under C-WTVC and 1053.3 g (7.0% higher than DP) under NREL2VAIL; its consumption is notably lower than the traditional A-ECMS, with more moderate growth and better final SOC stability. As the ideal optimal reference, DP maintains the lowest consumption across both conditions (final SOC nearly identical to the initial value), and the reasonable consumption gap between P-ECMS and DP, plus P-ECMS’s stable performance across conditions, demonstrates its favorable adaptability.