Sustainability Assessment of Austrian Dairy Farms Using the Tool NEU.rind: Identifying Farm-Specific Benchmarks and Recommendations, Farm Typologies and Trade-Offs

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. LCA Core Module

- Enteric fermentation

- Feed production (on-farm and external sources, i.e., purchased feed)

- Manure handling and application (including internal nutrient flows), fertiliser production, and application

- Energy and material input used for dairy farming

- Milk and growth performance of cows, biological data, animal health

- Infrastructure (milk production-related machinery and buildings on farms)

2.2. Supplementary Key Performance Indicators

- Proportion of High Nature Value Farmland (HNVF) Type 1 by the method according to [43]

- Keeping of endangered livestock species (assessed categories: yes/no; proportion)

- Animal Health Scores for cows and calves using the Q-Check Animal Welfare Assessment, developed by [44]. The Q-Check Animal Welfare Assessment includes indicators for longevity, udder health, metabolic stability, as well as raising losses related to calves culling rates in cows.

- Profit margins of farms according to the Federal Institute of Agricultural Economics, Rural and Mountain Research [45], accounting for direct and indirect inputs, their costs and revenues, also related to the functional unit ‘1 cow per year’ in addition to product, land and farm level.

2.3. Data Demand and Collection

2.4. Description of Study Farms

- Conventional dairy farms in favoured areas: 70 farms

- Conventional alpine dairy farms: 45 farms

- Organic dairy farms in favoured areas: 29 farms

- Organic alpine dairy farms: 26 farms

2.5. Data-Driven Clustering Approach

2.6. Statistical Analysis Methods

3. Results & Discussion

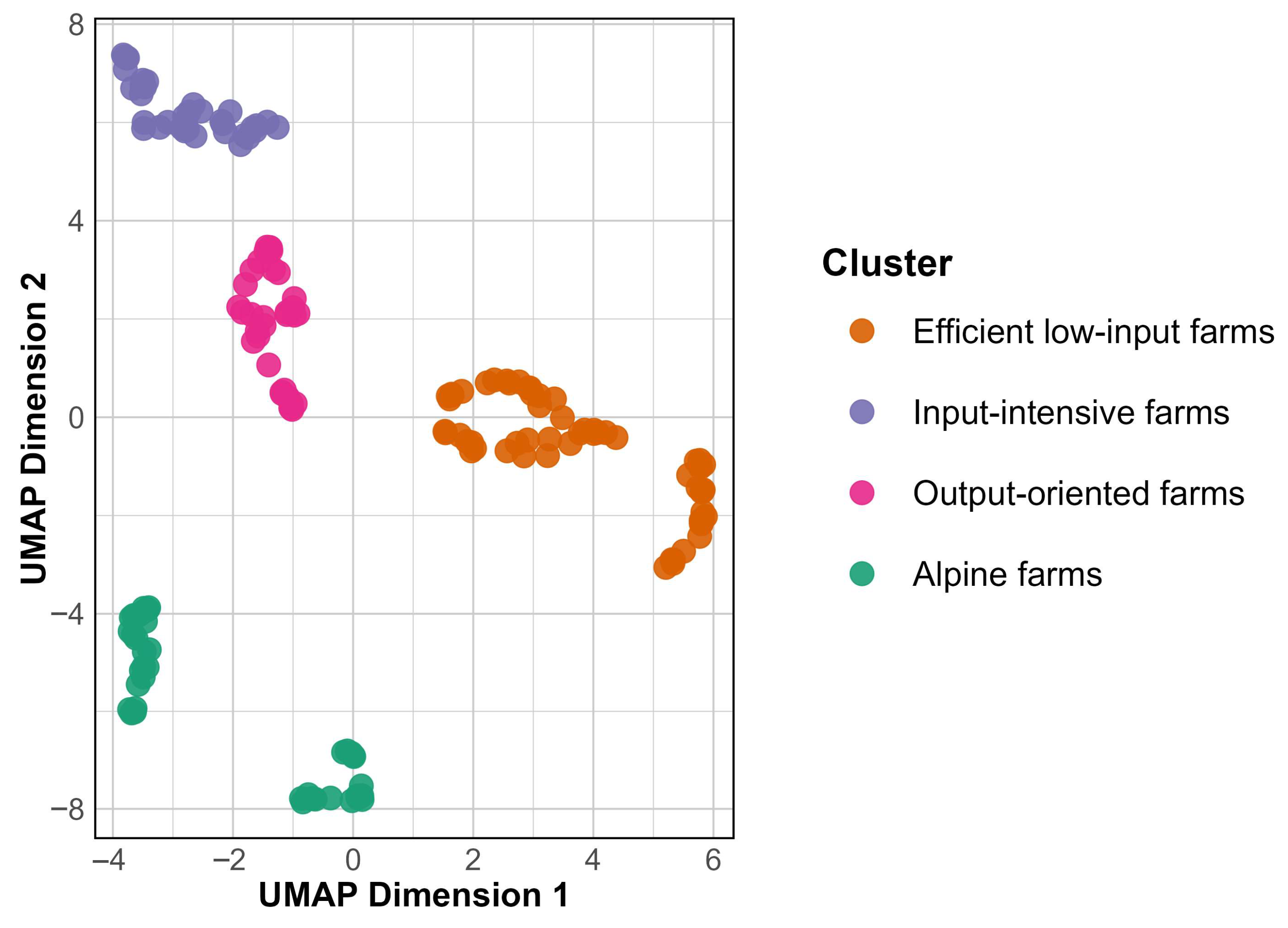

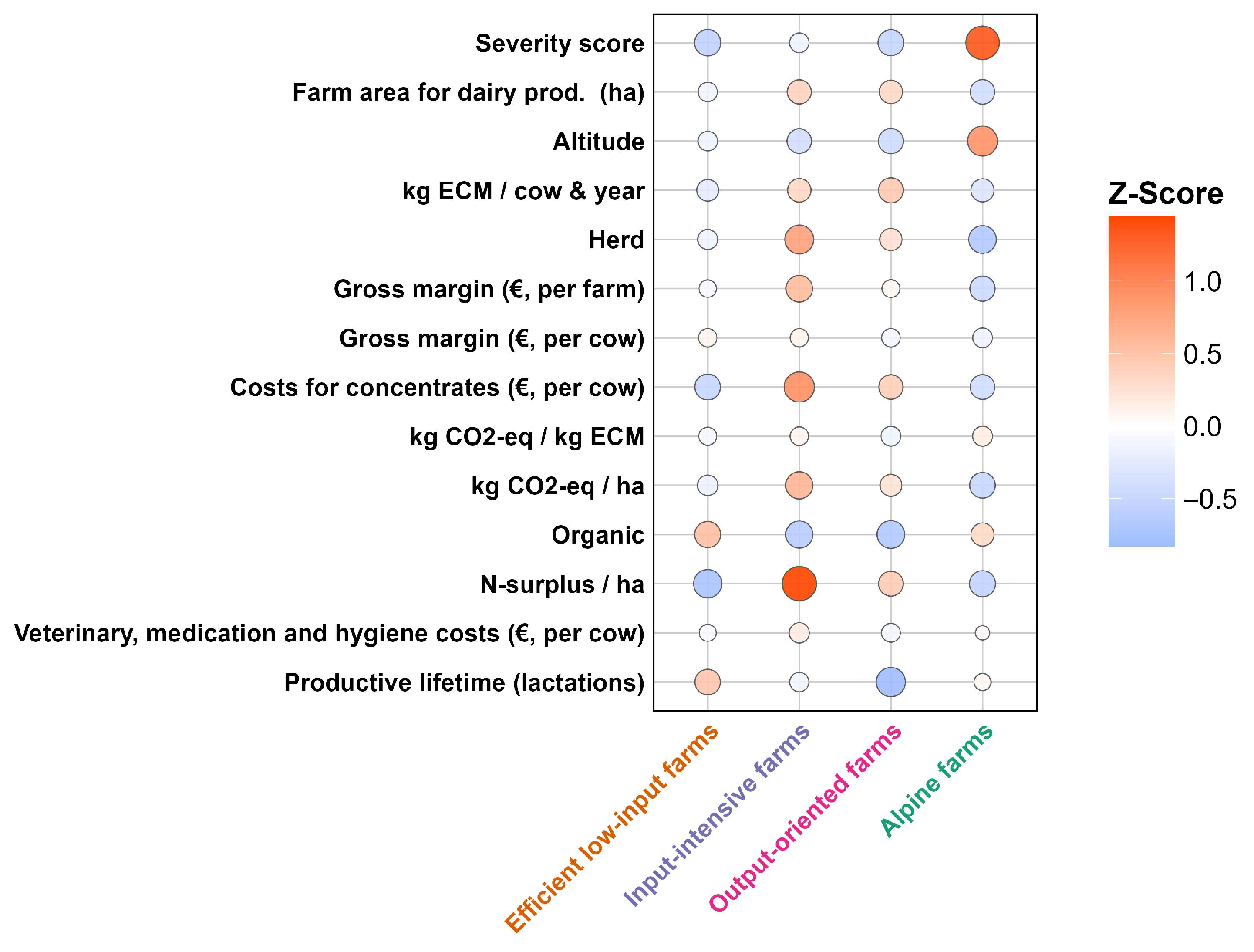

3.1. Dairy Farm Clusters and Their Sustainability Profiles

3.2. Identified Sustainability Trade-Offs

3.3. Strategic Pathways for Sustainable Development

3.3.1. General Improvement Options

3.3.2. Cluster- and Farm-Specific Recommendations for Improvement

3.4. Methodological Reflections

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

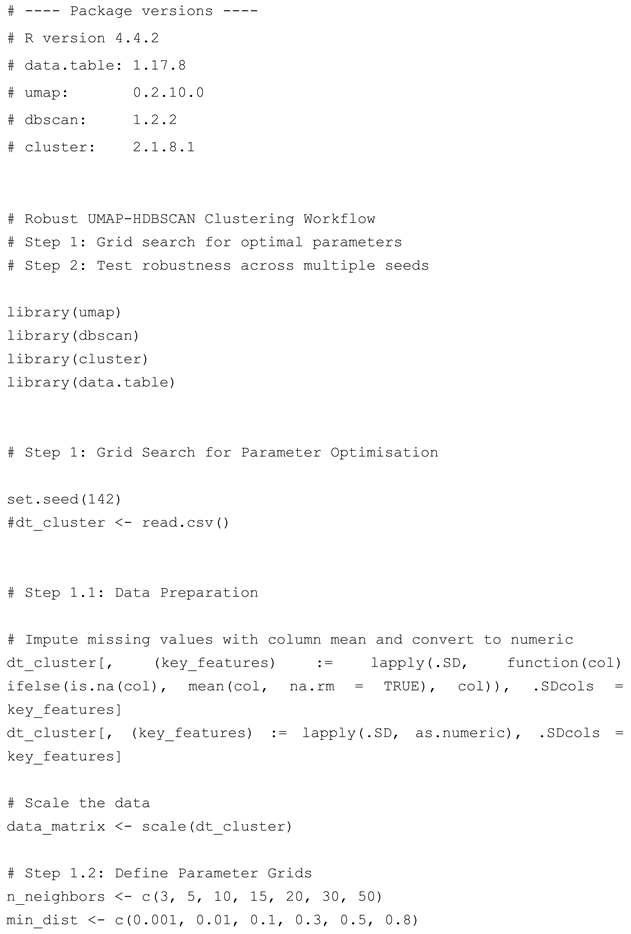

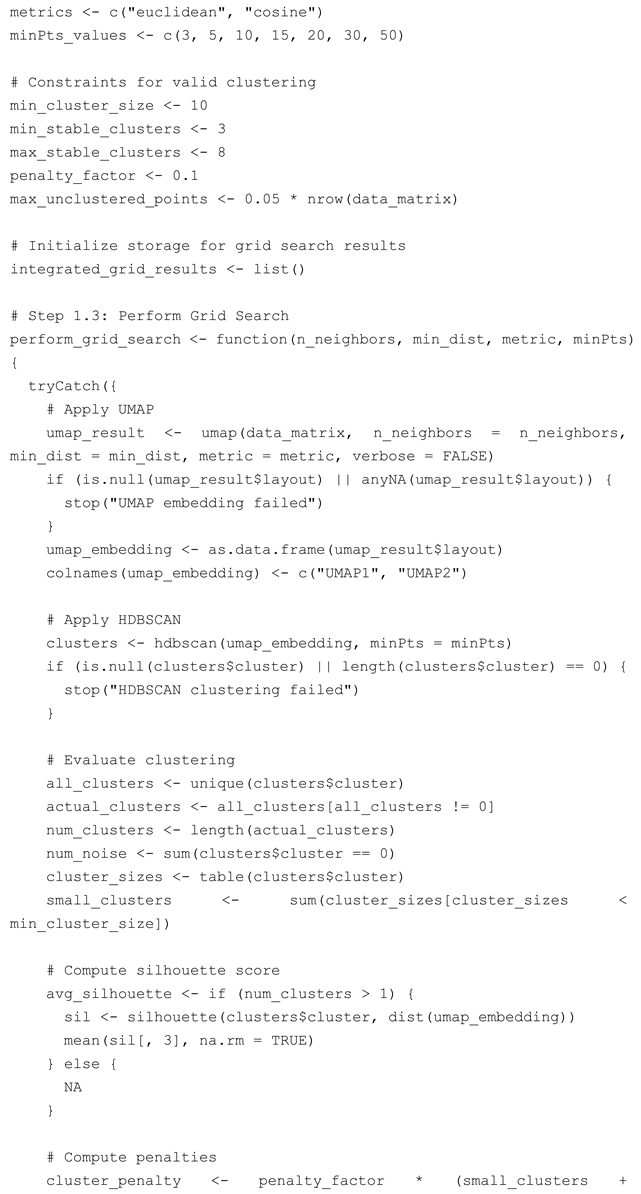

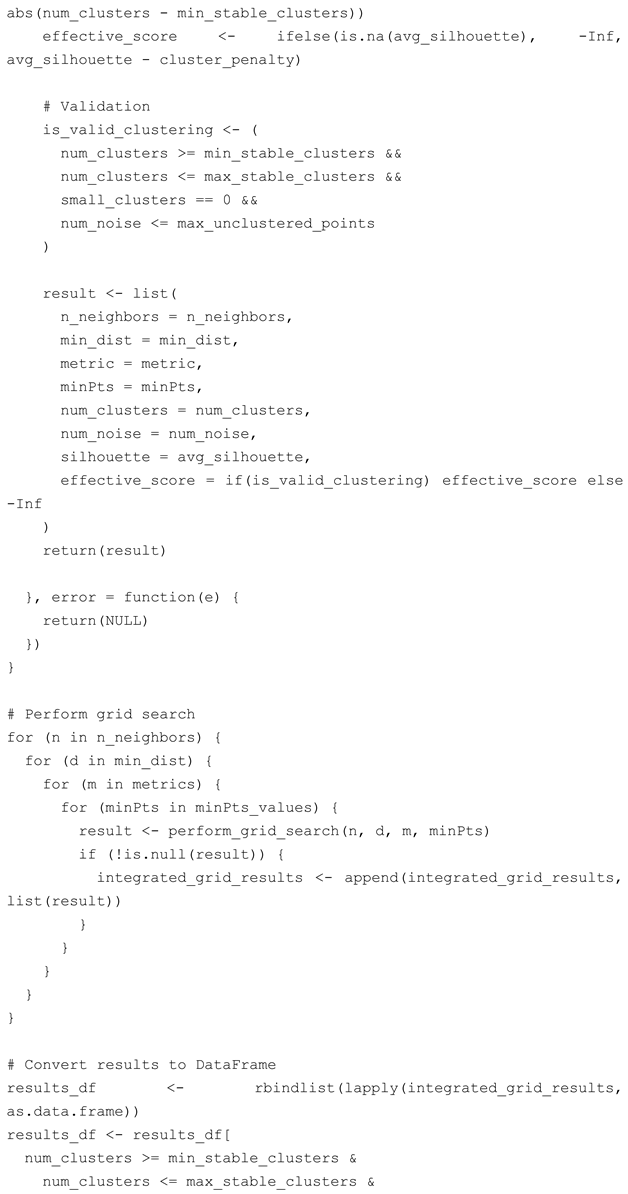

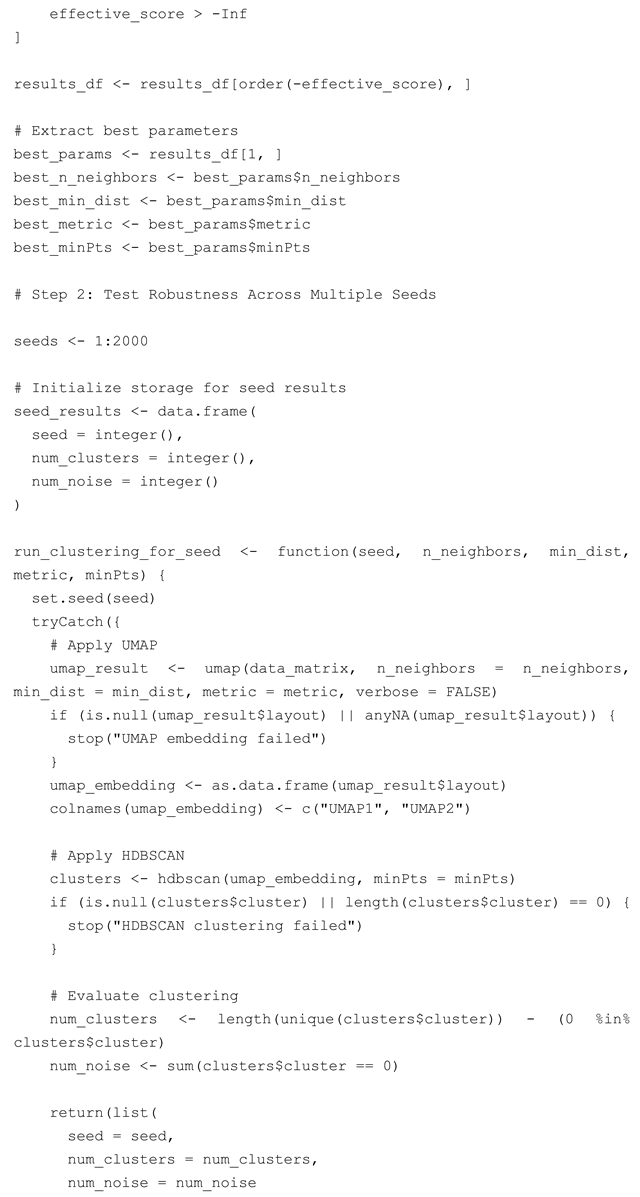

Appendix A. R Code for a Clustering

References

- Cimmino, F.; Catapano, A.; Petrella, L.; Villano, I.; Tudisco, R.; Cavaliere, G. Role of Milk Micronutrients in Human Health. Front. Biosci. (Landmark Ed.) 2023, 28, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weaver, C.M. Role of Dairy Beverages in the Diet. Physiol. Behav. 2010, 100, 63–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singaravadivelan, A.; Sachin, P.B.; Harikumar, S.; Vijayakumar, P.; Vindhya, M.V.; Farhana, F.M.B.; Rameesa, K.K.; Mathew, J. Life Cycle Assessment of Greenhouse Gas Emission from the Dairy Production System—Review. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2023, 55, 320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Misselbrook, T.; del Prado, A.; Chadwick, D. Opportunities for Reducing Environmental Emissions from Foragebased Dairy Farms. Agric. Food Sci. 2013, 22, 93–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglas, C.; Pandey, P. Nitrate and Bacterial Loads in Dairy Cattle Drinking Water and Potential Treatment Options for Pollutants—A Review. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 3017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gislon, G.; Ferrero, F.; Bava, L.; Borreani, G.; Prà, A.D.; Pacchioli, M.T.; Sandrucci, A.; Zucali, M.; Tabacco, E. Forage Systems and Sustainability of Milk Production: Feed Efficiency, Environmental Impacts and Soil Carbon Stocks. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 260, 121012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz De Otálora, X.; Del Prado, A.; Dragoni, F.; Balaine, L.; Pardo, G.; Winiwarter, W.; Sandrucci, A.; Ragaglini, G.; Kabelitz, T.; Kieronczyk, M.; et al. Modelling the Effect of Context-Specific Greenhouse Gas and Nitrogen Emission Mitigation Options in Key European Dairy Farming Systems. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2024, 44, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grassauer, F.; Herndl, M.; Nemecek, T.; Guggenberger, T.; Fritz, C.; Steinwidder, A.; Zollitsch, W. Eco-Efficiency of Farms Considering Multiple Functions of Agriculture: Concept and Results from Austrian Farms. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 297, 126662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grassauer, F.; Herndl, M.; Iten, L.; Gaillard, G. Environmental Assessment of Austrian Organic Dairy Farms With Closed Regional Production Cycles in a Less Favorable Production Area. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2022, 6, 817671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisert, J.; Sahraei, A.; Knob, D.A.; Lambertz, C.; Zollitsch, W.; Hörtenhuber, S.; Kral, I.; Breuer, L.; Gattinger, A. Transforming the Feeding Regime towards Low-Input Increases the Environmental Impact of Organic Milk Production on a Case Study Farm in Central Germany. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2025, 30, 79–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanon, T.; Hörtenhuber, S.; Fichter, G.; Peratoner, G.; Zollitsch, W.; Gatterer, M.; Gauly, M. Effect of Management System and Dietary Seasonal Variability on Environmental Efficiency and Human Net Food Supply of Mountain Dairy Farming Systems. J. Dairy Sci. 2025, 108, 597–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drews, J.; Czycholl, I.; Krieter, J. A Life Cycle Assessment Study of Dairy Farms in Northern Germany—The Development of Environmental Impacts throughout a Decade. Züchtungskunde 2020, 92, 236–256. [Google Scholar]

- Rotz, C.A.; Stout, R.C.; Holly, M.A.; Kleinman, P.J.A. Regional Environmental Assessment of Dairy Farms. J. Dairy Sci. 2020, 103, 3275–3288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Der Werf, H.M.G.; Knudsen, M.T.; Cederberg, C. Towards Better Representation of Organic Agriculture in Life Cycle Assessment. Nat. Sustain. 2020, 3, 419–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Joint Research Centre. Understanding Product Environmental Footprint and Organisation Environmental Footprint Methods; Publications Office: Luxembourg, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Soosten, D.; Meyer, U.; Flachowsky, G.; Dänicke, S. Dairy Cow Health and Greenhouse Gas Emission Intensity. Dairy 2020, 1, 20–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, D.; Hennessy, T.; Moran, B.; Shalloo, L. Relating the Carbon Footprint of Milk from Irish Dairy Farms to Economic Performance. J. Dairy Sci. 2015, 98, 7394–7407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balmford, A.; Amano, T.; Bartlett, H.; Chadwick, D.; Collins, A.; Edwards, D.; Field, R.; Garnsworthy, P.; Green, R.; Smith, P.; et al. Author Correction: The Environmental Costs and Benefits of High-Yield Farming. Nat. Sustain. 2019, 2, 339–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ertl, P.; Klocker, H.; Hörtenhuber, S.; Knaus, W.; Zollitsch, W. The Net Contribution of Dairy Production to Human Food Supply: The Case of Austrian Dairy Farms. Agric. Syst. 2015, 137, 119–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ertl, P.; Knaus, W.; Zollitsch, W. An Approach to Including Protein Quality When Assessing the Net Contribution of Livestock to Human Food Supply. Animal 2016, 10, 1883–1889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steffen, W.; Richardson, K.; Rockstrom, J.; Cornell, S.E.; Fetzer, I.; Bennett, E.M.; Biggs, R.; Carpenter, S.R.; de Vries, W.; de Wit, C.A.; et al. Planetary Boundaries: Guiding Human Development on a Changing Planet. Science 2015, 347, 1259855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, J.; Dalgaard, R. Arla Foods FarmTool V2021—Updates and Adding New Technologies; LCA Consultants: Aarhus, Denmark, 2021; p. 58. Available online: https://lca-net.com/files/FarmTool-v2021_20211221.pdf (accessed on 5 December 2025).

- Bayrische Landesanstalt für Landwirtschaft (LfL) Deckungsbeiträge Und Kalkulationsdaten—Milchkuhhaltung. Available online: https://www.stmelf.bayern.de/idb/milchkuhhaltung.html (accessed on 5 December 2025).

- Vries, d.M.; van Dijk, W.; de Boer, J.A.; de Haan, M.H.A.; Oenema, J.; Verloop, J.; Lagerwerf, L.A. Calculation Rules of the Annual Nutrient Cycling Assessment (ANCA) 2019; Background Information about Farm-Specific Environmental Performance Parameters. Report 1279; Wageningen Livestock Research: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2020; p. 112. Available online: https://edepot.wur.nl/533905 (accessed on 5 December 2025).

- Herron, J.; O’Brien, D.; Jordan, S.; Shalloo, L. AgNav: The New Digital Sustainability Platform for Agriculture in Ireland. 2025. Available online: https://teagasc.ie/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/AgNav-The-new-digital-sustainability-platform-for-agriculture-in-Ireland.pdf (accessed on 5 December 2025).

- Paçarada, R.; Hörtenhuber, S.; Hemme, T.; Wurzinger, M.; Zollitsch, W. Sustainability Assessment Tools for Dairy Supply Chains: A Typology. Sustainability 2024, 16, 4999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meul, M.; Passel, S.; Nevens, F.; Dessein, J.; Rogge, E.; Mulier, A.; Hauwermeiren, A. MOTIFS: A Monitoring Tool for Integrated Farm Sustainability. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2008, 28, 321–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Otalora, X.; del Prado, A.; Dragoni, F.; Estelles, F.; Amon, B. Evaluating Three-Pillar Sustainability Modelling Approaches for Dairy Cattle Production Systems. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruckli, A.K.; Hörtenhuber, S.J.; Ferrari, P.; Guy, J.; Helmerichs, J.; Hoste, R.; Hubbard, C.; Kasperczyk, N.; Leeb, C.; Malak-Rawlikowska, A.; et al. Integrative Sustainability Analysis of European Pig Farms: Development of a Multi-Criteria Assessment Tool. Sustainability 2022, 14, 5988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triste, L.; Marchand, F.; Debruyne, L.; Meul, M.; Lauwers, L. Reflection on the Development Process of a Sustainability Assessment Tool: Learning from a Flemish Case. Ecol. Soc. 2014, 19, art47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siebrecht, N. Sustainable Agriculture and Its Implementation Gap—Overcoming Obstacles to Implementation. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hörtenhuber, S.J.; Steininger, F.; Herndl, M.; Wieser, S.; Linke, K.; Egger-Danner, C. NEU.Rind-Tool—Method Description; Rinderzucht Austria: Vienna, Austria, 2022; Available online: https://www.rinderzucht.at/projekt/neu-rind.html (accessed on 5 December 2025).

- IPCC. Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Stocker, T.F., Qin, D., Plattner, G.-K., Tignor, M., Allen, S.K., Boschung, J., Nauels, A., Xia, Y., Bex, V., Midgley, P.M., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2013; ISBN 978-1-107-05799-1. [Google Scholar]

- Umweltbundesamt. Austria’s National Inventory Report 2023; Umweltbundesamt (Austrian Environment Agency): Vienna, Austria, 2023; p. 833. Available online: https://www.umweltbundesamt.at/fileadmin/site/publikationen/rep0852.pdf (accessed on 5 December 2025).

- International Dairy Federadtion (IDF). The IDF Global Carbon Footprint Standard for the Dairy Sector. Bulletin of the IDF 520(2022; The International Dairy Federation: Brussels, Belgium, 2022. Available online: https://shop.fil-idf.org/products/the-idf-global-carbon-footprint-standard-for-the-dairy-sector (accessed on 5 December 2025).

- Ineichen, S.; Schenker, U.; Nemecek, T.; Reidy, B. Allocation of Environmental Burdens in Dairy Systems: Expanding a Biophysical Approach for Application to Larger Meat-to-Milk Ratios. Livest. Sci. 2022, 261, 104955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPCC. 2019 Refinement to the 2006 IPCC Guidelines for National Greenhouse Gas Inventories; IPCC: Kyoto, Japan, 2019. Available online: https://www.ipcc.ch/report/2019-refinement-to-the-2006-ipcc-guidelines-for-national-greenhouse-gas-inventories/ (accessed on 5 December 2025).

- Amon, B.; Hutchings, N.; Dämmgen, U.; Sommer, S.; Webb, J.; Mellios, G.; Juhrich, K. EMEP/EEA Air Pollutant Emission Inventory Guidebook 2023. 2023; p. 64. Available online: https://www.eea.europa.eu/en/analysis/publications/emep-eea-guidebook-2023 (accessed on 5 December 2025).

- Wernet, G.; Bauer, C.; Steubing, B.; Reinhard, J.; Moreno-Ruiz, E.; Weidema, B. The Ecoinvent Database Version 3 (Part I): Overview and Methodology. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2016, 21, 1218–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, A.; Brooks, T.M. Land Use Intensity-Specific Global Characterization Factors to Assess Product Biodiversity Footprints. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2018, 52, 5094–5104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sjaunja, L.O.; Baevre, L.; Junkkarinen, L.; Pedersen, J.; Setälä, J. A Nordic Proposal for an Energy-Corrected Milk Standard. In Proceedings of the 11th Session of the International Committee for Recording and Use of Animal Productivity (ICAR); International Dairy Federation (IDF): Paris, France, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Nemecek, T.; Thoma, G. Allocation between Milk and Meat in Dairy LCA: Critical Discussion of the International Dairy Federation’s Standard Methodology. In Proceedings of the 12th International Conference on Life Cycle Assessment of Food 2020, Berlin, Germany, 13–16 October 2020; DIL: Quakenbrück, Germany, 2020; pp. 86–89. [Google Scholar]

- Bartel, A.; Süßenbacher, E.; Sedy, K. Weiterentwicklung des Agrarumweltindikators “High Nature Value Farmland” für Österreich; Umweltbundesamt (Austrian Environment Agency): Wien, Austria, 2011; p. 90. Available online: https://www.umweltbundesamt.at/fileadmin/site/publikationen/rep0348.pdf (accessed on 5 December 2025).

- Thünen Institute. Q Check: Tierwohl Mit System—Von Der Betrieblichen Eigenkontrolle Zum Nationalen Monitoring. 2021. Available online: https://www.thuenen.de/media/publikationen/project_brief/Project_brief_2021_35.pdf (accessed on 5 December 2025).

- Federal Institute of Agricultural Economics, Rural and Mountain Research IDB—Interaktive Deckungsbeiträge und Kalkulationsdaten 2025. Available online: https://idb.agrarforschung.at/verfahren/konventionell/milchkuhhaltung (accessed on 5 December 2025).

- Bundesministerium für Land- und Forstwirtschaft, Regionen und Wasserwirtschaft (BML) Integrated Administration and Control System (IACS) Data (Integriertes Verwaltungs- und Kontrollsystem, INVEKOS). 2024. Available online: https://www.bmluk.gv.at/themen/landwirtschaft/gemeinsame-agrarpolitik-foerderungen/nationaler-strategieplan/direktzahlungen-ab-2023/invekosinvekosgis.html (accessed on 5 December 2025).

- Slagboom, M.; Kargo, M.; Edwards, D.; Sørensen, A.C.; Thomasen, J.R.; Hjortø, L. Organic Dairy Farmers Put More Emphasis on Production Traits than Conventional Farmers. J. Dairy Sci. 2016, 99, 9845–9856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez, S.; Timler, C.J.; Michalscheck, M.; Paas, W.; Descheemaeker, K.; Tittonell, P.; Andersson, J.A.; Groot, J.C.J. Capturing Farm Diversity with Hypothesis-Based Typologies: An Innovative Methodological Framework for Farming System Typology Development. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0194757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matzhold, C.; Schodl, K.; Klimek, P.; Steininger, F.; Egger-Danner, C. A Key-Feature-Based Clustering Approach to Assess the Impact of Technology Integration on Cow Health in Austrian Dairy Farms. Front. Anim. Sci. 2024, 5, 1421299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campello, R.J.G.B.; Moulavi, D.; Sander, J. Density-Based Clustering Based on Hierarchical Density Estimates. In Advances in Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Pei, J., Tseng, V.S., Cao, L., Motoda, H., Xu, G., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; Volume 7819, pp. 160–172. ISBN 978-3-642-37455-5. [Google Scholar]

- McInnes, L.; Healy, J. Accelerated Hierarchical Density Clustering. arXiv 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldini, M.; Da Borso, F.; Rossi, A.; Taverna, M.; Bovolenta, S.; Piasentier, E.; Corazzin, M. Environmental Sustainability Assessment of Dairy Farms Rearing the Italian Simmental Dual-Purpose Breed. Animals 2020, 10, 296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mazzetto, A.M.; Falconer, S.; Edwards, P.J.; Glassey, C.B.; Neal, M.B.; Ledgard, S.F. Effects of Management and Technology Scenarios on the Carbon Footprint of Milk from Pasture-Based Dairy Farm Systems. J. Dairy Sci. 2025, 108, 12407–12420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bava, L.; Sandrucci, A.; Zucali, M.; Guerci, M.; Tamburini, A. How Can Farming Intensification Affect the Environmental Impact of Milk Production? J. Dairy Sci. 2014, 97, 4579–4593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berton, M.; Bittante, G.; Zendri, F.; Ramanzin, M.; Schiavon, S.; Sturaro, E. Environmental Impact and Efficiency of Use of Resources of Different Mountain Dairy Farming Systems. Agric. Syst. 2020, 181, 102806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mennig, P.; Szigeti, Z. Synergies and Trade-Offs between Environmental Impacts and Farm Profitability: The Case of Pasture-Based Dairy Production Systems. J. Agric. Food Res. 2025, 21, 101798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, R.; Kok, A.; Mourits, M.; Hogeveen, H. Effects of Extending Dairy Cow Longevity by Adjusted Reproduction Management Decisions on Partial Net Return and Greenhouse Gas Emissions: A Dynamic Stochastic Herd Simulation Study. J. Dairy Sci. 2024, 107, 6902–6912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grandl, F.; Furger, M.; Kreuzer, M.; Zehetmeier, M. Impact of Longevity on Greenhouse Gas Emissions and Profitability of Individual Dairy Cows Analysed with Different System Boundaries. Animal 2019, 13, 198–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hörtenhuber, S. Wir wirken Langlebigkeit und Tiergesundheit auf die Klima- und Umweltbilanz? In Proceedings of the Rinderzucht Austria Seminar. Nutzungsdauer—Ein traditionelles Konzept mit Zukunft? Rinderzucht Austria: Vienna, Austria, 2025. pp. 61–68. Available online: https://www.rinderzucht.at/downloads/seminarunterlagen.html?file=files/rinderzucht-austria/01-rinderzucht-austria/downloads/rza-seminar/2025-03-06-tagungsband-rinderzucht-austria-seminar-2025-web.pdf (accessed on 5 December 2025).

- Cooper, J.; Reed, E.Y.; Hörtenhuber, S.; Lindenthal, T.; Løes, A.-K.; Mäder, P.; Magid, J.; Oberson, A.; Kolbe, H.; Möller, K. Phosphorus Availability on Many Organically Managed Farms in Europe. Nutr. Cycl. Agroecosystems 2018, 110, 227–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haas, G.; Deittert, C.; Köpke, U. Farm-Gate Nutrient Balance Assessment of Organic Dairy Farms at Different Intensity Levels in Germany. Renew. Agric. Food Syst. 2007, 22, 223–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.; Delgado-Baquerizo, M.; Fanin, N.; Chen, X.; Zhou, Y.; Du, G.; Hu, F.; Jiang, L.; Hu, S.; Liu, M. Nutrient-Induced Acidification Modulates Soil Biodiversity-Function Relationships. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 2858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parmentier, L. “Three-Strip Management”: Introducing a Novel Mowing Method in Perennial Flower Strips and Grass Margins to Increase Habitat Complexity and Attractiveness for Pollinators. J. Pollinat. Ecol. 2023, 34, 267–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buri, P.; Humbert, J.-Y.; Arlettaz, R. Promoting Pollinating Insects in Intensive Agricultural Matrices: Field-Scale Experimental Manipulation of Hay-Meadow Mowing Regimes and Its Effects on Bees. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e85635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguirre-Villegas, H.A.; Besson, C.; Larson, R.A. Modeling Ammonia Emissions from Manure in Conventional, Organic, and Grazing Dairy Systems and Practices to Mitigate Emissions. J. Dairy Sci. 2024, 107, 359–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bang, R.; Samsonstuen, S.; Hansen, B.G.; Guajardo, M.; Møller, H.; Sommerseth, J.K.; Goez, J.C.; Flaten, O. Win-Win or Lose-Win? Economic-Climatic Synergies and Trade-Offs in Dual-Purpose Cattle Systems. Agric. Syst. 2025, 222, 104189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagemann, N.; Gerling, C.; Hölting, L.; Kernecker, M.; Markova-Nenova, N.N.; Wätzold, F.; Wendler, J.; Cord, A.F. Improving Result-Based Schemes for Nature Conservation in Agricultural Landscapes—Challenges and Best Practices from Selected European Countries. Reg. Environ. Change 2025, 25, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zabel, A. Biodiversity-Based Payments on Swiss Alpine Pastures. Land Use Policy 2019, 81, 153–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerci, M.; Knudsen, M.T.; Bava, L.; Zucali, M.; Schönbach, P.; Kristensen, T. Parameters Affecting the Environmental Impact of a Range of Dairy Farming Systems in Denmark, Germany and Italy. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 54, 133–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilfart, A.; Baillet, V.; Balaine, L.; De Otálora, X.D.; Dragoni, F.; Krol, D.J.; Frątczak-Müller, J.; Rychła, A.; Rodriguez, D.G.P.; Breen, J.; et al. DEXi-Dairy: An Ex Post Multicriteria Tool to Assess the Sustainability of Dairy Production Systems in Various European Regions. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2023, 43, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Indicators | Functional Units | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| ‘kg ECM’ 1 | ‘ha Farmland’ 2, ‘Farm’ and ‘Cow’ | ||

| 1a | Global Warming Potential (GWP100) | kg CO2-eq | kg CO2-eq |

| 1b | Methane emissions | kg CH4 | kg CH4 |

| 1c | Di-nitrous oxides emissions | kg N2O | kg N2O |

| 1d | Fossil carbon dioxide emissions | kg CO2 | kg CO2 |

| 2 | Food/protein supply | Human-edible feed conversion efficiency | kg protein (net/gross) |

| 3 | Biodiversity | Potential species losses (feed-dependent) | % HNVF 3 Type 1; endangered livestock breeds (y/n) |

| 4 | Fossil energy demand | MJ | GJ |

| 5 | Ammonia emission and Acidification (SO2-eq) | g NH3, g SO2-eq | kg NH3 |

| 6 | Animal Health Scores | Scores of cows and calves | |

| 7 | Profit margin | € | € |

| Data Group | Data Source | Parameters on… |

|---|---|---|

| Animal Data | Cattle Data Network (RDV) | Animal arrivals and departures, milk yields and milk ingredients, reproduction characteristics, body masses and slaughter performances, health records |

| Housing & Manure Management | Cattle Data Network (RDV) and manual entries | Barn systems, type of manure storage, manure removal and treatments, manure application |

| Feeding | Cattle Data Network (RDV) and manual entries | Animal diets, including concentrate amounts and roughage proportions, periods with specific diets |

| Land Management | Integrated Administration and Control System (IACS) | Grassland and crop type areas with their intensity of use, other biodiversity-related farmland |

| Economic Data | Federal Institute of Agricultural Economics, Rural and Mountain Research | Default milk and slaughter cattle prices, costs for replacement animals, costs related to feed or energy carriers, and other farm inputs |

| Parameter/Characteristic | Conventional Dairy Farms in Favoured Areas | Conventional Alpine Dairy Farms | Organic Dairy Farms in Favoured Areas | Organic Alpine Dairy Farms |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Farms (n) | 71 | 45 | 29 | 25 |

| Herd size—cows (n) | 46 ± 20 | 35 ± 19 | 33 ± 20 | 26 ± 13 |

| Average lifetime performance (kg ECM 1 per cow) | 34,749 ± 11,489 | 34,479 ± 14,326 | 35,130 ± 14,966 | 36,695 ± 13,934 |

| Average herd yield | ||||

| (kg ECM per cow and year) | 9239 ± 1497 | 8722 ± 1865 | 7300 ± 1625 | 7229 ± 1728 |

| Average productive lifetime 2 (years) | 3.65 ± 1.24 | 3.52 ± 1.56 | 5.07 ± 2.26 | 4.41 ± 1.94 |

| Proportion of annual time budget on pasture (%) | 2.8 ± 6.5 | 7.5 ± 13.0 | 23.4 ± 21.8 | 23.0 ± 15.7 |

| Imported feed-nitrogen (%) | 31.0 ±10.3 | 31.8 ±13.2 | 15.4 ± 10.6 | 17.1 ±14.2 |

| Characteristic | Alpine Farms | Efficient Low-input Farms | Output- Oriented Farms | Input- Intensive Farms |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of farms (n) | 41 | 60 | 33 | 36 |

| Altitude (m a.s.l.) | 846 ± 253 | 622 ± 154 | 554 ± 203 | 564 ± 118 |

| Gross margin (€) | 3755 ± 1185 | 3923 ± 1157 | 4009 ± 771 | 4277 ± 987 |

| Average lactations 1 (n) | 3.19 ± 0.72 | 3.50 ± 0.86 | 2.53 ± 0.30 | 3.05 ± 0.36 |

| Average productive lifetime 2 (years) | 3.94 ± 1.95 | 4.45 ± 2.08 | 3.12 ± 1.18 | 4.01 ± 0.91 |

| kg ECM/cow & year | 8900 ± 1350 | 8655 ± 1310 | 10,027 ± 1117 | 9819 ± 924 |

| kg CO2/kg ECM – incl. infrastructure | 1.17 ± 0.20 | 1.10 ± 0.17 | 1.09 ± 0.13 | 1.16 ± 0.50 |

| kg CO2/hectare – incl. infrastructure | 11,601 ± 7910 | 13,605 ± 5409 | 16,183 ± 4276 | 18,555 ± 4516 |

| kg CO2/kg ECM – excl. infrastructure | 1.07 ± 0.15 | 1.03 ± 0.14 | 1.04 ± 0.11 | 1.11 ± 0.47 |

| Indicator Pair | Product-Related Unit | Area-Related Unit | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Human-edible feed conversion efficiency vs. protein yield | heFCE | kg protein from milk/ha | <0.001 |

| Acidification potential | kg SO2-eq/kg ECM | kg SO2-eq/ha | <0.001 |

| Global warming potential | kg CO2-eq/kg ECM | kg CO2-eq/ha | <0.01 |

| Gross margin (€) | €/kg ECM | €/kg ECM | <0.001 |

| Fossil energy demand | MJ/kg ECM | MJ/kg ECM | <0.05 |

| Potential species loss vs. HNVF proportion | Pot. species losses/kg ECM | % HNVF/ total farmland (ha) | <0.05 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Hörtenhuber, S.J.; Matzhold, C.; Herndl, M.; Steininger, F.; Linke, K.; Wieser, S.; Egger-Danner, C. Sustainability Assessment of Austrian Dairy Farms Using the Tool NEU.rind: Identifying Farm-Specific Benchmarks and Recommendations, Farm Typologies and Trade-Offs. Sustainability 2026, 18, 303. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010303

Hörtenhuber SJ, Matzhold C, Herndl M, Steininger F, Linke K, Wieser S, Egger-Danner C. Sustainability Assessment of Austrian Dairy Farms Using the Tool NEU.rind: Identifying Farm-Specific Benchmarks and Recommendations, Farm Typologies and Trade-Offs. Sustainability. 2026; 18(1):303. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010303

Chicago/Turabian StyleHörtenhuber, Stefan Josef, Caspar Matzhold, Markus Herndl, Franz Steininger, Kristina Linke, Sebastian Wieser, and Christa Egger-Danner. 2026. "Sustainability Assessment of Austrian Dairy Farms Using the Tool NEU.rind: Identifying Farm-Specific Benchmarks and Recommendations, Farm Typologies and Trade-Offs" Sustainability 18, no. 1: 303. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010303

APA StyleHörtenhuber, S. J., Matzhold, C., Herndl, M., Steininger, F., Linke, K., Wieser, S., & Egger-Danner, C. (2026). Sustainability Assessment of Austrian Dairy Farms Using the Tool NEU.rind: Identifying Farm-Specific Benchmarks and Recommendations, Farm Typologies and Trade-Offs. Sustainability, 18(1), 303. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010303