1. Introduction

Indoor air quality (IAQ) is a significant concern for professionals in the chemistry and medicine industries and for ventilation system design. Research indicates that concentrations of organic compounds are substantially higher indoors than outdoors, suggesting that the majority originate from indoor sources [

1]. Individuals typically spend at least 85% of their time indoors, a figure that increased during the COVID-19 pandemic. Acute exposure to polluted indoor air can cause immediate discomfort, while chronic exposure may lead to serious health problems [

2,

3,

4]. Consequently, evaluating indoor pollutant levels in residential environments is essential [

5,

6].

Residential indoor air quality is determined by both indoor activities and the materials used in building construction. Indoor carbonyl sources include building materials, furniture, textiles, carpeting, adhesives, household products, cigarette smoke, cooking emissions, air fresheners, cosmetics, and other consumer goods [

7]. Cooking methods that involve high-fat foods generate higher emissions [

8,

9,

10]. Wall paints, floor finishes, and wood or galvanized steel furniture can emit organic compounds such as formaldehyde, hexanal, acetone, and acetaldehyde [

1]. Cigarette smoke is the primary source of formaldehyde indoors, while PCHPs also contribute substantially to indoor pollution [

11]. These products frequently contain organic solvents, additives, and fragrances that release pollutants. Although vaping is often perceived as safer than smoking, it still negatively affects indoor air quality. E-cigarette or vaping-associated lung injury (EVALI) has emerged as a public health concern, as e-cigarettes emit harmful compounds such as carbonyls from flavoring agents and byproducts of glycol-based solvents [

12].

Excessive inhalation of formaldehyde can cause emphysema, renal failure, and other symptoms, and may ultimately lead to cancer. Formaldehyde is classified as a possible human carcinogen [

13]. Acetaldehyde is also considered a potential carcinogen [

14] and can affect multiple organs, including the nervous system, skin, eyes, and respiratory mucosa [

15]. Inhalation of moderate levels of acetone may result in headaches, light-headedness, confusion, and increased pulse rate [

16]. Frequent use of PCHPs has been linked to lung diseases such as asthma [

17]. Carbonyls are also known to cause odors and sensory irritations, which are key features of sick building syndrome (SBS) and directly influence residents’ perceptions of IAQ [

18]. The presence of carbonyl compounds in residential indoor environments, therefore, represents a potential health risk for occupants.

There are very few studies related to carbonyl measurement in Mexico [

19,

20,

21,

22].

Table 1 presents carbonyl levels in indoor and outdoor environments in MCMA. From the indoor/outdoor ratios (I/O) reported in these studies, it was found that indoor sources are the factors that dominate the dynamics of carbonyl compounds in indoor air.

Regulatory Framework for Carbonyl Compounds

Formaldehyde. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), the lowest formaldehyde concentration that is associated with health effects such as nose and throat irritation after a short-term exposure is 100 μg m

−3 [

23]. A guideline value of 30 μg m

−3 has been proposed for the prevention of irritant effects [

24]. The Umweltbundesant from Germany [

25,

26] and French Agency for Food, Environmental and Occupational Health and Safety [

27,

28] propose limit values for formaldehyde of 50 and 100 μg m

−3, respectively.

Acetaldehyde. The WHO has not published a specific guideline value for acetaldehyde in ambient air. However, the Ministry for the Environment of New Zealand adopted a guideline value of 30 μg m−3, which is considered a reasonably precautionary approach based on the WHO’s upper cancer risk level. Other countries and organizations have also established their own guidelines, e.g., Canada has established a long-term limit of 280 μg m−3 for indoor air. The Environment Protection Agency of the United States (U.S. EPA) has established a reference concentration (RfC) of 9 μg m−3 for continuous inhalation exposure without appreciable noncancer effects, whereas the Agence Nationale de Sécurité Sanitaire (ANSES) in France recommends a limit value of 160 μg m−3 for long-term indoor air exposure.

Acrolein. Currently, the WHO has not published any universal guideline values specifically for acrolein concentrations in indoor environments. Some organizations and research studies have provided reference values and exposure limits to acrolein, but these values are focused on industrial and occupational environments. The Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) have established a permissible exposure limit (PEL) of 250 μg m−3 as an 8 h time-weighted average. The American Conference Governmental Industrial Hygienists (ACGIH) has established a threshold limit value (TLV) of 300 μg m−3 as an 8 h time-weighted average.

Acetone. While the WHO provides indoor air quality guidelines for various pollutants, acetone is typically regulated by occupational standards rather than specific indoor guidelines for the general public. The OSHA has established a PEL of approximately 1000 μg m−3, whereas ACGIH recommends a TLV of 250 ppm.

Propionaldehyde. There are no specific indoor air guidelines for propionaldehyde; typical reference values based on occupational exposure limits range from 400 to 870 μg m−3. These occupational standards are not intended for the general population, and indoor levels should ideally be much lower, especially to protect vulnerable groups.

Butyraldehyde. There are currently no universally recognized indoor air guidelines for butyraldehyde; most standards are based on occupational exposure limits of 400 μg m−3.

During and after the COVID-19 pandemic, lockdowns led people to work from home, resulting in increased exposure to indoor pollutants that could impact health. Marchanda et al. [

29] found that formaldehyde and acetaldehyde were the main carbonyls present in living rooms and bedrooms of residences in France. The higher concentrations of carbonyls detected in these rooms are likely due to the abundance of furniture, decorations, cosmetics, books, and magazines [

30]. Moreover, the concentration of carbonyls in indoor air increases significantly during cooking. Apartment designs in Mexico often lack physical separation between the kitchen, dining room, and living room due to space constraints, allowing carbonyl emissions from the kitchen to impact all three areas.

For this reason, it is interesting to evaluate the possible differences in carbonyl levels by room in residences in Mexico. Since improving IAQ requires understanding the types of pollutants present in indoor air, identifying their sources, estimating their concentrations, and assessing their synergistic effects [

31,

32,

33,

34]; the main objectives of the present study were to (1) quantify the concentrations of six carbonyls in the indoor air of living rooms and bedrooms in three urban residences with different surrounding environments (residential, commercial, and industrial) located in the north, center, and south of the MCMA during the COVID-19 lockdown; and (2) assess the potential health risks due to carbonyls exposure in these residences.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

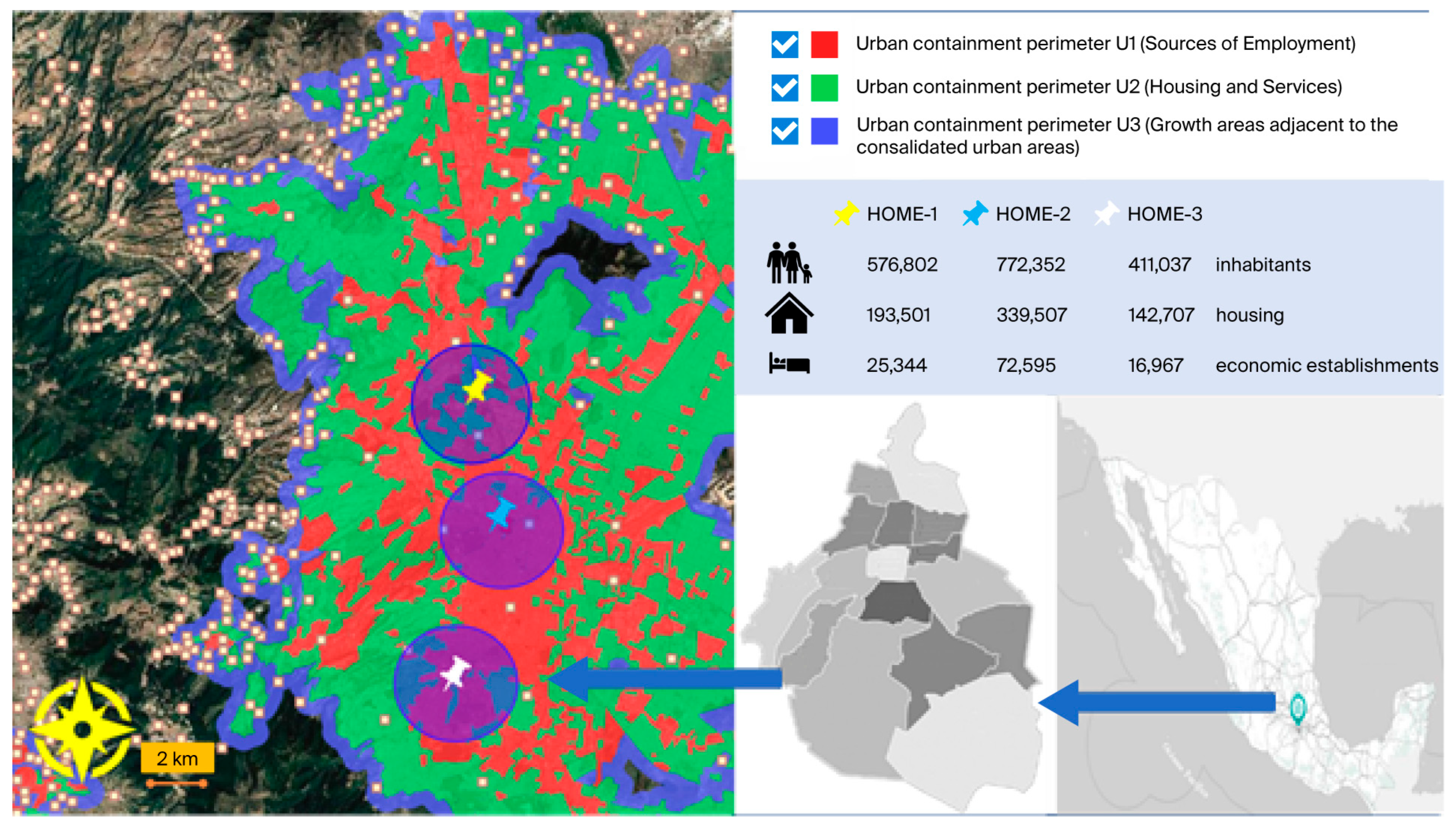

The study area comprises three homes located in the northern, downtown, and southern areas of Mexico City. All homes were two-story buildings, street facing with only one side or front (with one window and the main entrance), approximately 25 years old, and with natural ventilation. The cooking fuel used was propane-butane gas. The location of each sampling site is shown in

Figure 1. Taking into consideration the factors mentioned above, each of the three sampling sites is described below.

Home-1 is located at 19°30′11″ North latitude and 99°11′13″ West longitude. It is surrounded by avenues with intense vehicular traffic in an area characterized by significant industrial and commercial activity, as well as numerous public transport stops. This location serves as a hub where various types of public transportation converge, with several buses departing to different destinations to enhance passenger mobility. Home-1 is situated in the northern part of the MCMA.

Home-2 is located at 19°25′20″ North latitude and 99°09′59″ West longitude. It is located in an area of great commercial and tourist activity with primary roads (metropolitan), residential areas characterized by vertical buildings of varying heights, commercial buildings, and shopping malls, which is reflected in the intense flow of public and private transportation throughout the day. It is located in the downtown area of MCMA.

Home-3 is located at 19°20′01″ North latitude and 99°11′54″ West longitude. It is located near a green space (Viveros park), surrounded by commercial buildings and entertainment areas (museums and urban parks), attracting residents, workers, and tourists with constant activity, and multilane main avenues and roads with heavy traffic. It is located in the southern zone of the MCMA.

We used the geographic information system of the National Institute of Geography, Statistics and Informatics (INEGI) entitled “Space and Data of Mexico” (

https://www.inegi.org.mx/app/mapa/espacioydatos, 21 October 2025) to consult information regarding population data, urban containment perimeters, and economic activities for each of the sampling sites, considering a local scale scope (a radius of 4 km) [

35]). As shown in

Figure 1, the Home-1 site exhibits two types of urban containment perimeters, with the presence of sources of employment (U1, primarily commercial establishments) and housing and services (U2). On the other hand, at the Home-2 site, a dominance of the urban containment perimeter U1 (sources of employment in commercial establishments) can be observed. The Home-3 site also showed U1 and U2 urban containment perimeters, with U1 dominance.

The meteorological conditions during the sampling period of March and April 2021 marked the end of winter and the beginning of warming weather. This is a transitional period in which temperatures begin to rise. During this period, the average daily maximum temperatures ranged from 24 °C to 26 °C, with some days exceeding the average by 1 to 1.5 °C. This high atmospheric radiation induces conditions that catalyze the formation of photochemical ozone, with certain carbonyls, such as formaldehyde and acetaldehyde, as ozone precursor species [

21].

Figure 2 shows the winds blowing from the east, north, south, and northeast for Home-1, where higher concentrations of aldehydes were observed, while for Home-2 and Home-3, the prevailing winds were from the north and northeast. Pollutants emitted in the industrial zone are transported by these winds as observed in an analysis of reverse trajectories [

36].

Table 2 presents the average and standard deviation of relative humidity (%), temperature (°C), and wind speed (m s

−1) for each site during the entire sampling period. The meteorological data were collected from three stations belonging to the University National of Mexico (UNAM) (High School Meteorological Station Program PEMBU-UNAM and RUOA).

In

Table 3, some of the main characteristics of the Home-1, Home-2, and Home-3 are presented. It can be observed that Home-2 was the home with the smallest area, with the higher number of residents, and with minor ventilation through windows, whereas, Home-1 was the only house in which a smoker was present during the study.

2.2. Sampling Method and Analysis

In Mexico, the COVID-19 lockdown period had three periods: from March 2020 to March 2021, when isolation was very strict; from March to December 2021, when remote work began; and from January to August 2022, when hybrid work activities prevailed. As a result of this, many companies allowed employees to work from home, increasing the time people spent in the home environments during this period. This study measured carbonyl compound levels in three homes to assess indoor air quality during the second COVID-19 lockdown period, specifically during March and April, 2021.

The sample collection and analysis methods were strictly in accordance with the US EPA Method TO-11A [

5,

37,

38,

39]. Sampling was carried out using a semi-automatic carbonyl sequencer manufacture (TAI Engineering, Mexico City, Mexico) from 8–14 April 2021, focusing on living rooms and bedrooms. Sampling was carried out simultaneously in both living rooms and bedrooms in each home, with 2 measurement points (one point per room per home). In the case of living room-kitchen area, sampling devices were installed just between the living room and the kitchen in the center of the area; whereas, in the bedrooms, samplers were installed in the center of the room. An automatic sampler with a programmable mechanism for 10 h of total sampling time was used for the campaign, and the measurements were carried out in sequential periods of 2 h at a flow of 1 L min

−1. Sampling was carried out from 8:00 h to 18:00 h (in 2 h intervals), a time when the inhabitants of the houses carried out cleaning (from 8:00 to 13:00 h) and cooking activities (In Mexico, regular hours for food preparation are from 8:00 to 18:00 h). Nighttime sampling was not conducted to avoid disturbing residents due to pump noise and the operators entering the rooms. The total number of daily samples for each home was 10 (5 samples in the living room and 5 samples in the bedroom), with a total of 150 samples for each home for the whole study period. The number of occupants varied throughout the day, because the residents generally continued to work at home all day and made intermittent outings to the shop and to meet the needs of the occupants. The kitchens were equipped with stoves and heaters that use LP gas. The pilot lights of both stoves and heaters remained on all day, and food was prepared 3 times a day (morning, afternoon and night). The houses did not have air conditioning, and ventilation was carried out through the regular opening of windows between 10:00 and 14:00 h.

The indoor atmospheric conditions, such as temperature and humidity, were recorded during the sampling period in each home to account for factors affecting indoor comfort. This was done by using a Cole-ParmerTM (Chicago, IL, USA) Traceable device, which allowed us to simultaneously measure temperature and relative humidity. Mercury thermometers were also used to measure temperature.

The equipment was coupled to two GAST brand vacuum pumps which alternated every 2 h by passing a current of air through the solenoid valves by means of their suction. Air samples were collected using 2,4-dinitrophenylhydrazine (DNPH) silica column sampling tubes (Waters, Milford, MA, USA). In addition, in order to eliminate the interference caused by ozone (O

3) during the determinations of aldehydes, we placed a copper coil internally impregnated with potassium iodide solution (KI) at 10%, avoiding the degradation of hydrazone derivatives [

40,

41,

42]. Two laboratory blanks and two field blanks were collected every 2 days for quality assurance. After collection, the sampling tube was sealed and stored at a constant temperature of 4 °C in a refrigerator, and the samples were then analyzed using high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC). The detection wavelength of the ultraviolet absorption detector was set to 360 nm, the C18 reverse phase column (4.6 × 250 mm) was selected for the chromatographic analysis, and the column temperature was set at 30 °C. Details of the mobile phase selection of acetonitrile/water binary solvent system, elution gradient, and elution program are shown in

Table 4. The HPLC standard curves of 15 types of carbonyls were plotted using 8 standard samples with known concentrations ranging from 0.025 to 1.50 μg mL

−1, which fully covered the actual concentration range of carbonyls in the studied environments.

Figure 3 depicts the semi-automatic carbonyl sampling equipment, designed according to EPA Method TO-11A. This equipment uses readily available DNPH-impregnated cartridges, as previously described. This semi-automatic sampling system is an electronic system based on a programmable timer with five independent outputs. This timer controls the solenoids that pass air through the cartridges and activates the power stage to start a vacuum pump. To calibrate the sampler’s systems and ensure sampling quality, each pump was calibrated to guarantee a constant flow rate throughout the sampling period using a rotameter connected to a gasometer with a constant flow rate of 1 L min

−1. Collection efficiency was determined by connecting two cartridges in series under the same sampling conditions described, obtaining values > 95% for all carbonyls analyzed. Details of the analysis method can be found in the literature [

37,

38,

43,

44,

45].

2.3. Quality Assurance

Quality assurance was maintained by measuring blank samples, method detection limits, and reproducibility. Two field blanks accompanied each sampler lot to the sampling site, were stored in the laboratory during exposure, and later analyzed to assess potential contamination during transport and storage. For each lot, four unexposed samplers (laboratory and field blanks) were analyzed to determine blank values. Method detection limits were set at three times the standard deviation of the blanks, or for compounds with zero blank, three times the standard deviation of the lowest analytical standard concentration. Reproducibility, assessed by coefficients of variation (n = 5–20), ranged from 0.6% for acetaldehyde to 5.8% for acetone. Limits of detection (LOD) and quantification (LOQ) represent the minimum concentrations that can be reliably detected and quantified. LODs for formaldehyde, acetaldehyde, acetone, propionaldehyde, butyraldehyde, and acrolein derivatives were 0.01, 0.01, 0.02, 0.01, 0.01, and 0.03 μg L−1, respectively. Calibration curves ranging from 0.05 to 0.405 μg L−1 were constructed with a mixture of formaldehyde, acetaldehyde, acetone, propionaldehyde, butyraldehyde, and acrolein standards.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

The analysis of results involved the application of statistical methods, descriptive statistics, to observe behavior, trends, patterns, and dispersion. Bivariate correlations were also performed to analyze the relationship between variables and their potential association. Principal component analysis (PCA) and hypothesis testing using XLSTAT v.2016 software [

46] (Denver, CO, USA), were employed to simplify the complexity of the data without losing significant information, thus facilitating its interpretation and analysis.

3. Results and Discussion

Six carbonyl compounds were identified: formaldehyde, acetaldehyde, acrolein, acetone, propionaldehyde, and butyraldehyde.

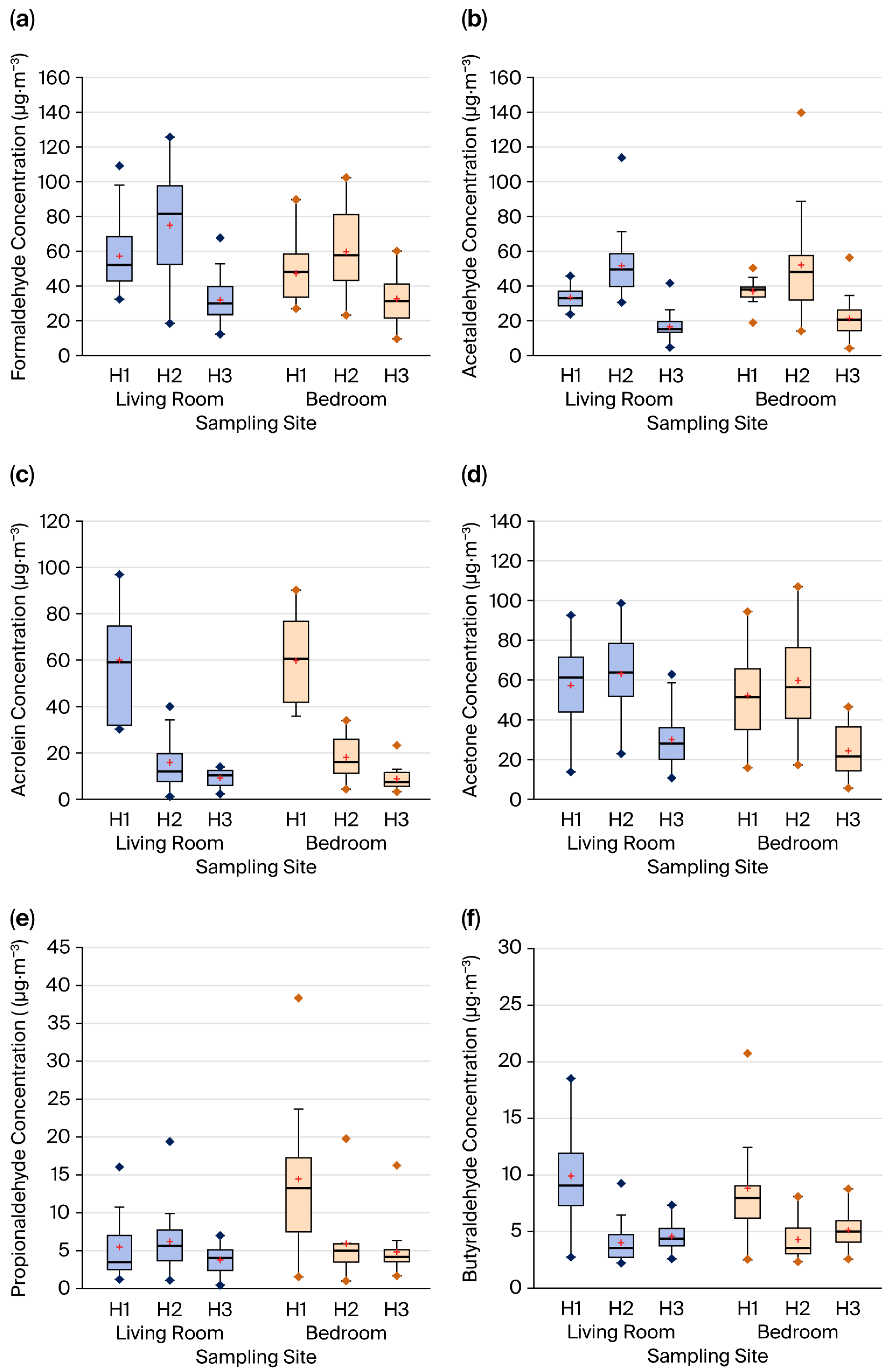

Figure 4 presents the mean, minimum, maximum, and standard deviation values for six detected carbonyls across the three sites. Detecting these compounds is important due to their potential health effects, especially seeing as people spent more time at home during the COVID-19 pandemic. The data showed that the relative abundance of carbonyls in living rooms and bedrooms was as follows: formaldehyde > acetaldehyde > acetone > propionaldehyde > butyraldehyde > acrolein.

Mean and maximum concentrations of formaldehyde and acetaldehyde were higher in Home-2 in both the living room and bedroom. Home-2 (located in the city center) is inhabited by a family of three adults and three children. In this house, formaldehyde levels were higher than acetaldehyde. The occupants used PCHPs continually to clean the house. In addition, they cooked at least four times a day (breakfast, lunch, dinner, and between meals). Outdoor pollution from the garage located outside the house likely contributed to the formaldehyde and acetaldehyde levels observed at this site. Results obtained at this sampling site were similar to those reported in other studies by Runeson-Broberg et al. [

47].

In Home-2, both the average and maximum levels of formaldehyde were the highest. Maximum concentrations found in Home-2 (125.66 and 102.31 μg m−3, for living room and bedroom, respectively) exceed the limit value proposed by the WHO and the guideline values recommended by agencies in Germany and France. The mean levels of formaldehyde found in Home-2 (74.93 ad 59.70 μg m−3 for living room and bedroom, respectively) exceeded the guideline value established by the Umweltbundesant in Germany. In the case of acetaldehyde, the average levels were the highest in Home-2, at 51.20 and 51.73 μg m−3 for the living room and bedroom, respectively. The maximum concentrations were 113.31 and 139.17 μg m−3 for the living room and bedroom, respectively. Considering the regulatory frameworks described in Section “Regulatory Framework for Carbonyl Compounds” (regulatory framework), we can conclude that in Home-2, mean and maximum concentrations exceeded the limit values proposed by New Zealand and the U.S. EPA, and are lower than those established by the Canadian Agency and the ANSES in France.

As can be observed in

Figure 4, levels of formaldehyde and acetaldehyde were higher in Home-1, located in the northern region, than in Home-3, primarily in the living room. This is as expected, since the living rooms contains more furniture and building materials (such as tapestry and laminate, which emit formaldehyde and other carbonyl compounds) than the bedrooms. Additionally, the living room serves as a space where sources such as cigarette smoke, air fresheners, flavorings, and candles are present. In addition, this residence is occupied by three older adults, one of whom frequently used an e-cigarette, spending most of his time in the living room. In Mexico, apartment designs typically lack a physical barrier separating the kitchen from the living and dining rooms. This layout may contribute to higher carbonyl levels in the living room compared to the bedrooms, likely due to emissions from cooking activities in the adjacent kitchen. In Home-1, the average formaldehyde concentrations were 57.86 and 47.28 μg m

−3 in the living room and bedroom, respectively, while the maximum concentrations reached were 109.09 and 89.71 μg m

−3 for the same rooms. The maximum formaldehyde concentration in the living room of Home-1 exceeded the limit value proposed by the World Health Organization and the guideline values recommended by agencies in Germany and France. Mean formaldehyde levels in Home-1 also surpassed the guideline value established by the Umweltbundesamt in Germany. Specifically, average acetaldehyde concentrations in Home-1 were 33.08 and 36.58 μg m

−3 for the living room and bedroom, respectively, with maximum values of 45.25 and 49.93 μg m

−3. These results indicated that both mean and maximum concentrations of acetaldehyde in Home-1 exceeded the limit values proposed by New Zealand and the U.S. EPA, but remained below those established by the Canadian Agency and ANSES in France.

Acrolein concentrations were significantly higher in Home-1 in comparison with Home-2 and Home-3, and were even higher in the living room. Unlike Home-2 and Home-3, one of the occupants of Home-1 smoked an e-cigarette, which is likely associated with the highest levels of this compound found in this house. Acrolein has been reported as one of the main organic compounds associated with e-cigarettes vapors [

48,

49]. Vapors are generated from solutions commonly known as e-liquids or e-juices, which contains solvents, various concentrations of nicotine, water, additives, and flavorings. The most popular solvents in e-liquids are glycerin (commonly of vegetal origin) and propylene glycol. When an electronic cigarette user inhales, it activates heating element that vaporizes the e-liquid. It has been estimated that vaporization temperature may reach up to 350 °C. This temperature is sufficiently high to induce physical changes in e-liquids and chemical reactions between their constituents. Solvents undergo thermal decomposition leading to the formation of potentially toxic compounds such as formaldehyde, acetaldehyde, acrolein, and acetone [

50]. Average concentrations for acrolein in Home-1 were 60.01 and 59.75 μg m

−3 for the living room and bedroom, respectively, whereas maximum concentrations were 96.89 and 90.21 μg m

−3. Clearly, since the sampling sites were residential homes, even maximum acrolein levels found in Home-1 were below the limit values established by OSHA and ACGIH. However, compared to the levels found for the other carbonyl compounds, these values were significantly high. Attention should be paid to these results, since these are potentially toxic compounds, and vaping has recently become popular among young people in Mexico.

Acetone levels were the highest in Home-2 in both rooms. The mean concentration of acetone was 63.02 and 59.72 μg m−3 in the living room and bedroom, respectively; whereas maximum concentrations reached were 98.55 and 106.89 μg m−3, in the same rooms. It is important to note that, in the case of this compound, the levels found in both rooms were comparable. Acetone levels in indoor air can be high because of clean products, paints, adhesives, and solvents that contain acetone. Bedrooms have significantly less ventilation in comparison with other areas of the residences, for example, the living room, whose proximity to the entrance of the houses can result in greater ventilation. However, cosmetics and PCHPs also contain acetone; even the use of electronic equipment can emit small quantities of this compound during their use. Although none of the concentrations of acetone found in this study exceeded the limits established by OSHA and ACGIH, in residential or non-occupational settings, concentrations should be significantly lower to assure safety and comfort.

Propionaldehyde and butyraldehyde had the lowest concentrations. Mean and maximum propionaldehyde levels were higher in the bedroom of Home-1 (14.46 and 38.34 μg m−3, respectively) and in the living room of Home-2 (6.21 and 19.42 μg m−3). In this study, all measured concentrations of propionaldehyde were well below the limits proposed for occupational exposure. Butyraldehyde levels were also the highest in Home-1, with mean concentrations of 9.91 and 8.82 μg m−3 in the living room and bedroom, respectively. Although butyraldehyde concentrations in this study did not exceed the limits established for occupational environments, indoor air quality standards for the general population should be set lower to protect sensitive individuals. Unlike formaldehyde and acetaldehyde, which are readily formed under typical indoor conditions, longer-chain aldehydes such as propionaldehyde and butyraldehyde are less likely to be produced and are more reactive, resulting in lower concentrations indoors; this could explain why propionaldehyde and acetaldehyde levels were the lowest.

Table 5 compares the formaldehyde and acetaldehyde concentrations measured in this study with values reported by other researchers worldwide. For formaldehyde and acetaldehyde in living rooms, as well as acetaldehyde in bedrooms, the concentrations observed were higher than those reported for Helsinki, Strasbourg, Bari, Paris, various European indoor environments, China, Spain, and Rio de Janeiro. Romania was an exception, with higher levels of formaldehyde and acetaldehyde. In contrast, formaldehyde concentrations in bedrooms were similar to those reported for Hangzhou, China, but remained lower than those recorded in Romania in retrofit residential buildings, and higher than most other indoor environments listed in

Table 5.

3.1. Diurnal Variability and Differences Between Rooms and Homes

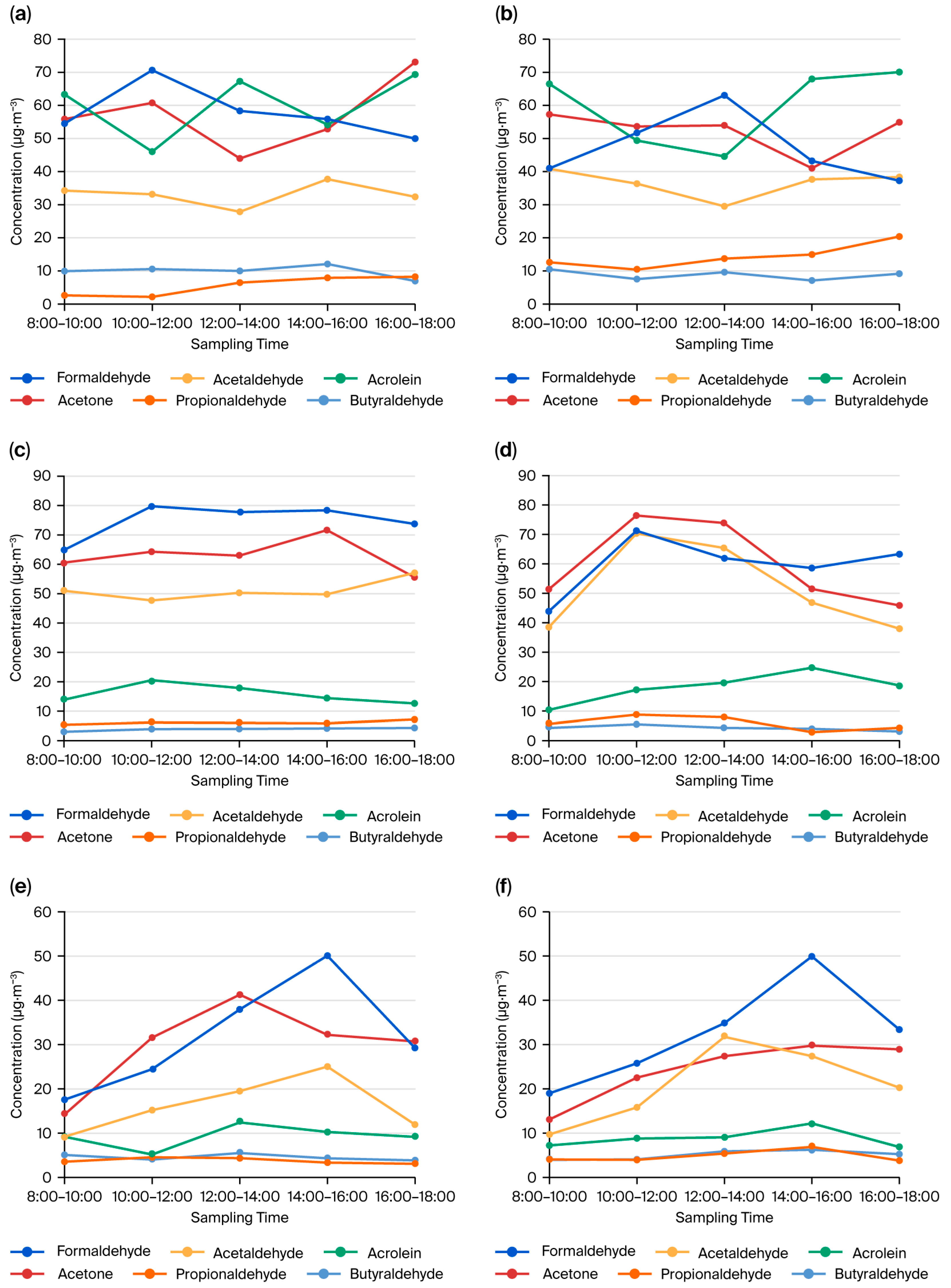

Figure 5 presents the time-series of the averaged concentration over the entire sampling period for each carbonyl compound and for each room type.

Figure S1 of the Supplementary Material shows the diurnal variability of temperature and relative humidity for both March and April for each home. Temperature and relative humidity show minor diurnal variability in bedrooms in comparison with the living rooms.

Figure 5a shows that, in the living room of Home-1, only formaldehyde, acroelin, and acetone exhibited diurnal variability, with peak concentrations at 10:00–12:00 h, 12:00–14:00 h, and 10:00–12:00 h, respectively. In the bedroom (

Figure 5b), these compounds also varied, peaking at 12:00–14:00 h for formaldehyde and acetone, and at 14:00–16:00 h for acrolein. Acetaldehyde, propionaldehyde, and butyraldehyde remained consistent throughout the day in both rooms. Because the data set does not follow a normal distribution, a nonparametric test (Kruskal–Wallis) was used to assess whether the observed differences were statistically significant. Since

p > α (α = 0.05), the null hypothesis (Ho) cannot be rejected. Therefore, the diurnal variability shown in

Figure 5a,b for both the living room and bedroom in Home-1 was not significant.

Figure 5c shows that carbonyls in the living room of Home-2 exhibited distinct diurnal patterns, indicating varied sources. Formaldehyde, acetone, and acrolein peaked at 10:00–12:00 h, 14:00–16:00 h, and 10:00–12:00 h, respectively. Propionaldehyde and butyraldehyde remained stable throughout the day. In the bedroom (

Figure 5d), formaldehyde, acetaldehyde, and acetone followed similar patterns, with higher concentrations from 10:00–12:00 h, suggesting common sources. Acrolein peaked at 14:00–16:00 h, while propionaldehyde and butyraldehyde stayed consistent during the day. As the data set is not normally distributed, we used the Kruskal–Wallis nonparametric test to assess statistical significance. Since

p exceeds α (0.05), we cannot reject the null hypothesis. Thus, the diurnal variability for both the living room and bedroom in Home-2, shown in

Figure 5c,d, was not significant.

Figure 5e shows that in the living room of Home-3, formaldehyde and acetaldehyde likely share a source, as both peaked at 14:00–16:00 h. Similarly, acetone and acrolein followed the same pattern, with higher concentrations at 12:00–14:00 h. Propionaldehyde and butyraldehyde remained stable throughout the day. In the bedroom of Home-3 (

Figure 5f), most carbonyl compounds, except acetaldehyde, displayed similar diurnal patterns, with higher levels at 14:00–16:00 h, indicating possible common sources. A nonparametric test was applied to determine whether the observed differences were statistically significant. For Home-3,

p-values were less than α (α = 0.05) for formaldehyde, acetaldehyde, and acetone in the living room, as well as for acetaldehyde in the bedroom. Therefore, the alternative hypothesis H

a was accepted, indicating that the diurnal variability observed (

Figure 5e,f) for these carbonyl compounds was statistically significant.

The Mann–Whitney bilateral test assessed significant differences between rooms in each home. Only propionaldehyde in Home-1 showed a significant difference between the living room and bedroom, indicating that different sources may have influenced carbonyl compound levels in these rooms. One e-cigarette user lives in Home-1, and spends most of their time in the living room, which could explain this significance.

The nonparametric Kruskal–Wallis test was applied to assess significant differences between homes for each room type. For living rooms, with the exception of propionaldehyde, all carbonyl compounds exhibited significant differences among the homes studied. This finding suggests that activities and sources varied across the different homes. In bedrooms, all carbonyl compounds demonstrated significant differences between homes, indicating that a range of activities and sources contributed to the observed carbonyl compound levels at each site.

3.2. Correlations and Principal Component Analysis (PCA)

Spearman correlation was used to calculate correlation coefficients. A high correlation coefficient between carbonyls indicates a common emission source for these compounds.

Table 6 and

Table 7 present the correlation coefficients among the various carbonyls measured in the studied homes.

Particularly strong correlations were observed between formaldehyde and acetaldehyde, formaldehyde and acetone, acetaldehyde and acetone, and acrolein and acetone in living rooms, indicating direct contributions from emission sources and diverse household activities, including cooking. A very strong correlation was observed between acrolein and relative humidity and acetone and relative humidity; this could be due to secondary emissions from materials sensitive to humidity. It was also observed that correlations between carbonyl compounds were slightly higher in the living rooms than in the bedrooms, but the number of significant coefficients was lower. This pattern could indicate that, the compounds co-vary in the living room, likely due to common emissions from heterogeneous sources or environmental conditions such as ventilation, temperature, or sunlight incidence, which promote similar formation or degradation processes.

In the bedrooms, strong correlations were observed between acetaldehyde and acetone, acrolein and acetone, and acrolein and propinoaldehyde. Acrolein and relative humidity presented a strong correlation, probably due to the lower amount of ventilation in the bedrooms in comparison with the living room, and emissions from hygroscopic materials. In addition, a greater number of significant correlations between variables was found in the bedrooms, suggesting that sources present in bedrooms could be more stable or homogeneous, such as personal products and diverse materials. A lower ventilation level could promote the accumulation of carbonyl compounds in the bedrooms. In fact, it can be observed in

Figure S1 of the Supplementary Material that both temperature and relative humidity showed a minor diurnal variability in comparison with the living rooms. As a result, the air composition in the living room represents a more variable mixture of primary and secondary emissions from heterogeneous sources, whereas in the bedroom, emissions are more homogeneous, and depend on the particular activities conducted in this space and on the ventilation level.

Prior to statistical analysis, values below LOD were replaced with LOD divided by two. Multiple linear regression analysis was conducted using a stepwise procedure, with variables included at a significance level of p less than 0.05 and excluded at p greater than 0.10.

PCA with Varimax rotation and multiple linear regression analysis was applied to the carbonyl concentration data set to reduce data complexity and identify patterns and relationships among compounds. In the PCA, each factor was associated with potential specific sources. The Varimax rotation maximized the variance of squared normalized factor loadings across variables for each factor, facilitating interpretation [

46]. Two factors accounted for 86.22% of the total variance in the data (

Table 8). Factors 1 and 2 indicated that formaldehyde, acetaldehyde, and acetone were associated with high loadings and reflected anthropogenic sources in Home-1 and Home-2. In contrast, factor 3 was not associated with any indoor source. These findings are consistent with the patterns observed in the time series presented in

Figure 5.

4. Personal Exposure and Cancer and Non-Cancer Risk

While the toxicological risk assessment includes three routes of exposure—inhalation, ingestion, and dermal contact—this study only considered the exposure route of inhalation, since only indoor pollutants were measured in the study sites. The average hourly inhalation rate in indoor environments is 0.63 m3 h−1, increasing to 0.83 m3 h−1 during periods of heavy activity. In the living rooms of three homes, the average exposure dose (PD) for formaldehyde, acetaldehyde, acrolein, acetone, propionaldehyde, and butyraldehyde, based on a residence time of 16 h, was 541.8 mg day−1. The residence time of 16 h was established considering that residents spend 16 h in the common area (living room, dining room and kitchen) and the rest of the day (8 h) in the bedroom. Unfortunately, neither nighttime sampling nor 24 h sampling were carried out to avoid disturbing residents, resulting in an underestimation of reported risk levels in this study. For bedrooms, a residence time of 8 h was used, resulting in an average indoor PD value of 470.8 mg day−1 for the same compounds. The average exposure dose values in these indoor environments exceeded the permissible limits established by organizations such as ACGIH, WHO, and the U.S. EPA.

These results suggest that internal emission sources were primarily responsible for the elevated PD values observed in the studied homes. This finding aligns with both international and domestic research [

61].

4.1. Cancer Risk

The International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) [

62] has classified formaldehyde as a Group 1 carcinogen, indicating that it is carcinogenic to humans, based on limited human evidence and sufficient animal evidence. Acetaldehyde is classified as Group 2B, probably carcinogenic to humans, due to insufficient human evidence but sufficient animal evidence, and is associated with tumor development in the respiratory tract of animals [

62]. Acrolein is classified as Group 2A, possibly carcinogenic to humans [

62]. To evaluate the inhalation risk for residents in the study areas, we estimated the non-cancer risk coefficient (HQ) and the lifetime cancer risk coefficient (LTCR) for exposure to formaldehyde and acetaldehyde at the levels found in this study, following the methodology of U.S. EPA [

63]. Daily exposure (

E) in milligrams per kilogram per day by inhalation is calculated as follows:

C (mg m

−3) represents the concentration of carbonyl compounds.

IRA denotes the adult inhalation rate, set at 0.83 m

3 h

−1 as specified by the Integrated Risk Information System (IRIS) [

64,

65].

Da refers to the adult exposure duration, which is 16 and 8 h day

−1 for indoor air in the living room and bedroom, respectively.

Bwa indicates the adult body weight, assumed to be 70 kg.

LTCR is calculated using the following equation:

SF refers to the slope factor for inhalation unit risk of air toxics, assuming a linear carcinogenic effect.

Table 9 presents

SF values for measured carbonyls reported by the U.S. EPA.

LTCR values should remain below the recommended limits set by the EPA (1 × 10

−6) and WHO (1 × 10

−5). Exceeding these limits increases the lifetime cancer risk for the exposed population.

Table 10 shows that cancer risk coefficients were higher for formaldehyde than for acetaldehyde. LCTR values for both compounds were consistently higher in living rooms across all homes, likely due to increased exposure time during the pandemic. Both formaldehyde and acetaldehyde had higher LCTR values in Home-2 compared to the other houses. Cancer risk coefficients for April 2021 were slightly lower than those in March 2021. LTCR values for formaldehyde exceeded EPA- and WHO-recommended limits in all homes and rooms, while acetaldehyde exceeded these limits in the living room of Home-2.

These results indicate that furniture, PCHPs, and building materials may pose significant health risks to occupants. The carcinogenic or hazardous potential of other carbonyl compounds cannot be evaluated due to insufficient guidelines and health data. Nevertheless, measuring these compounds remains valuable for identifying potential indoor sources. The collected data may also support the development of indoor air quality regulations in Mexico, where such standards have not yet been established.

4.2. Non-Cancer Risk

The non-cancer risk coefficients (risk of developing cardiovascular and respiratory diseases) were determined as hazard quotients (

HQ):

where

C is the average daily received concentration and

Rfc is the inhalation reference concentration for each carbonyl compound (

Table 11) which were taken from U.S. EPA. According to the WHO and the U.S. EPA, if

HQ > 1.0, it indicates that long-term exposure may result in adverse health effects (cardiovascular and respiratory diseases).

Table 11 shows that non-cancer risk coefficients were higher for formaldehyde than for acetaldehyde. For formaldehyde, except for Home-1 throughout the study and Home-2 in April, hazard quotient (HQ) values were higher in bedrooms. For acetaldehyde, except for Home-1 where the HQ was higher in the living room, most homes had higher HQ values in bedrooms during the study period. Home-1 and Home-2 had higher HQ values than Home-3. In all homes, the non-cancer risk coefficients for both formaldehyde and acetaldehyde exceeded the limits recommended by WHO and the U.S. EPA. These findings indicate a significant non-carcinogenic risk, especially with chronic exposure or among sensitive groups such as children, the elderly, or individuals with respiratory and cardiovascular conditions. The non-carcinogenic risk of other carbonyl compounds cannot be evaluated due to limited guidelines and health data. It is important to note that the reported HQ values may be underestimated, as some non-carcinogenic compounds can still significantly increase overall non-carcinogenic risk.

5. Conclusions

This case study found that carbonyl concentrations and behavior patterns during the lockdown due to the COVID-19 pandemic varied between homes, and were influenced by factors such as ventilation, home characteristics, location, emission sources, and occupant activities. Home-1 and Home-2 had the worst indoor air quality, especially regarding formaldehyde and acetaldehyde levels, which were higher in Home-2, since it was the home with the most residents. However, the levels found for acrolein and propionaldehyde were significant in Home-1, and were associated with the presence of a smoker resident, highlighting the significant contribution of indoor sources such as electronic cigarettes. The maximum formaldehyde (109.09, 125.65 and 67.69 µg m−3 and 89.71, 102.31 and 60.11 µg m−3; for the living rooms and bedrooms in Home-1, Home-2, and Home-3, respectively) and acetaldehyde (45.25, 113.31, and 41.28 µg m−3 and 49.93, 139.17, and 55.95 µg m−3; for the living rooms and bedrooms in Home-1, Home-2, and Home-3, respectively) concentrations exceeded limits set by the WHO, ANSES, the Ministry for the Environment of New Zealand, and the U.S. EPA. In living rooms, carbonyl levels were associated with furniture, building materials, cigarette smoke, air fresheners, aromatizes, candles, and cooking, as kitchens were not separated from living room areas, and LP gas was used throughout the day to cook meals. In bedrooms, primary sources included cosmetics, building materials, furniture, and PCHPs. Acrolein and acetone levels were higher in the home of the e-cigarette user. This is concerning, as vaping has become increasingly popular in Mexico, especially among young people, and there are currently no regulations addressing these sources. The air composition in the living room represents a more variable mixture of primary and secondary emissions from heterogeneous sources, whereas in the bedroom, emissions were more homogeneous, and depended on the particular activities conducted in the space and on ventilation level. While the toxicological risk assessment includes three routes of exposure—inhalation, ingestion and dermal contact—this study only considered the exposure route of inhalation, since only indoor pollutants were measured. LTCR (9.28 × 10−7–4.27 × 10−6 for formaldehyde, and 8.96 × 10−7–1.8 × 10−6 for acetaldehyde) and HQ (3.24–8.62 for formaldehyde, and 1.8–7.39 for acetaldehyde) values exceeded WHO and U.S. EPA recommendations, indicating increased risks of both carcinogenic and non-carcinogenic effects, particularly for vulnerable groups. This risk was higher in the living rooms. Unfortunately, neither nighttime sampling nor 24 h sampling were carried out to avoid disturbing residents, resulting in an underestimation of risk levels. These findings underscore the need to establish indoor air quality regulations in apartment buildings, especially given the lack of ventilation in most Mexican apartments, as well as regulations on e-cigarette and vaping product use in residential settings.