The Role of Policymakers and Businesses in Advancing the Forest-Based Bioeconomy: Perceptions, Challenges, and Opportunities

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Survey and Data Collection

- (1)

- Common statements on four forestry aspects (high-quality wood, introduction of non-native tree species, forest tourism, and biodiversity protection)

- (2)

- Strengthening the FBE in Slovenia

- (3)

- PES schemes

- (4)

- Business activity and perceived business potential.

2.2. Data Analysis

3. Results

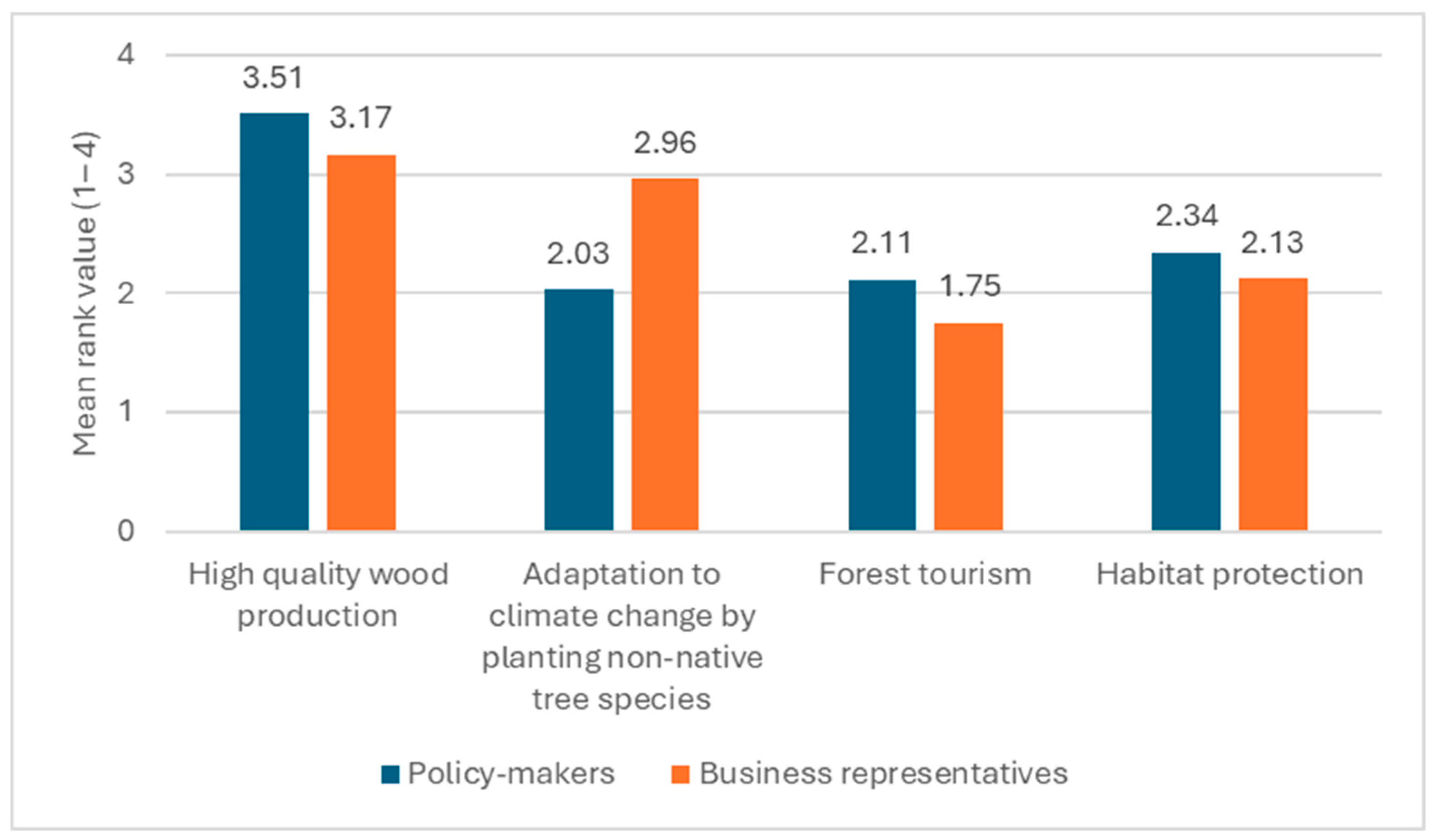

3.1. Common Statements on Four FBE-Related Aspects

3.1.1. High-Quality Wood

3.1.2. Introduction of Non-Native Tree Species

3.1.3. Forest Tourism

3.1.4. Biodiversity Conservation

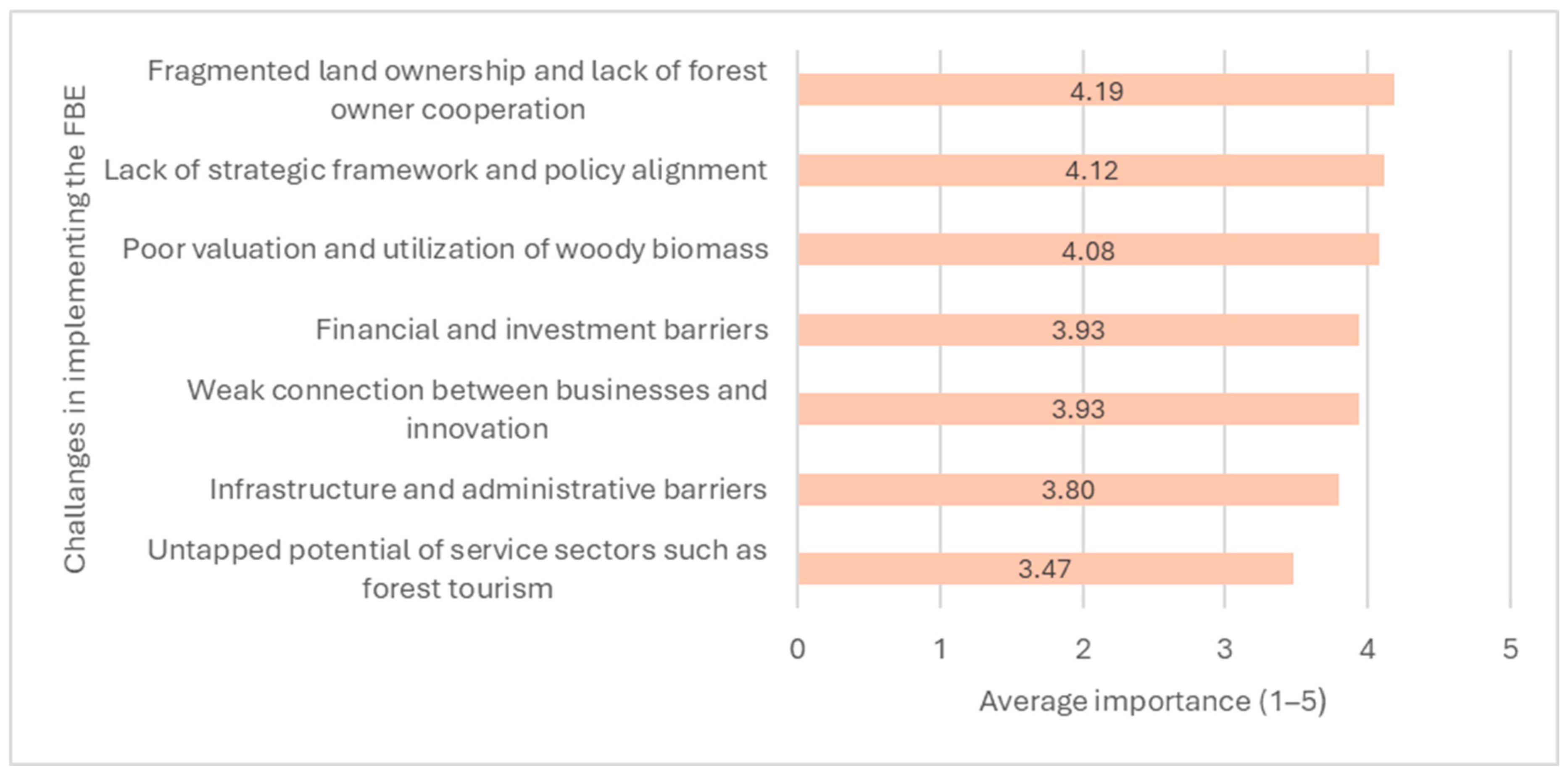

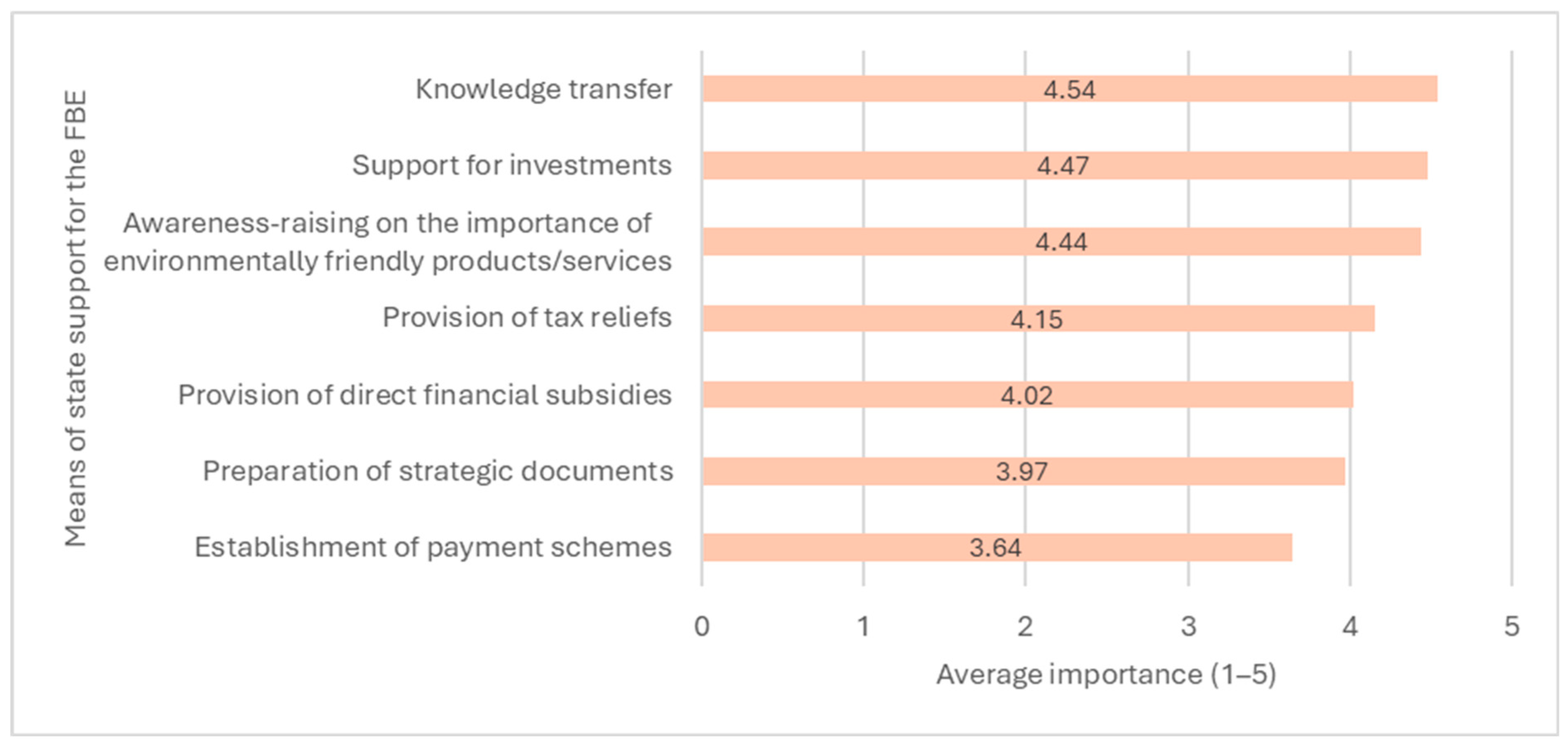

3.2. Strengthening the FBE in Slovenia

3.3. Businesses and the Potential of Their Products/Services

3.4. PES Schemes

3.4.1. PES and Policymakers

3.4.2. PES and Business Representatives

PWP and WPP Sectors

FT Sector

4. Discussion

4.1. Contrasting Positions: Biodiversity Versus the Economic Role of Forests

4.2. Key Challenges and Solutions for the FBE

4.3. PES as a Solution

4.4. Businesses and the FBE

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BE | Bioeconomy |

| FBE | Forest-based bioeconomy |

| PES | Payments for ecosystem services |

| ES | Ecosystem services |

| polFOR | Policymakers from Forestry sector |

| polWOOD | Policymakers from Wood industry sector |

| polENV | Policymakers from Environmental sector |

| polTOUR | Policymakers from Tourism sector |

| PWP | Business representatives from Primary wood production |

| WPP | Business representatives from Wood processing and products |

| FT | Business representatives from Forest tourism sector |

References

- Wolfslehner, B.; Linser, S.; Pülzl, H.; Bastrup-Birk, A.; Camia, A.; Marchetti, M. Forest Bioeconomy—A New Scope for Sustainability Indicators; From Science to Policy 4; European Forest Institute: Joensuu, Finland, 2016; ISBN 978-952-5980-30-1. [Google Scholar]

- Hurmekoski, E.; Lovrić, M.; Lovrić, N.; Hetemäki, L.; Winkel, G. Frontiers of the Forest-Based Bioeconomy—A European Delphi Study. For. Policy Econ. 2019, 102, 86–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonsson, R.; Rinaldi, F.; Pilli, R.; Fiorese, G.; Hurmekoski, E.; Cazzaniga, N.; Robert, N.; Camia, A. Boosting the EU Forest-Based Bioeconomy: Market, Climate, and Employment Impacts. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2021, 163, 120478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luhas, J.; Mikkilä, M. Social Sustainability in the Forest-Based Bioeconomy: A Narrative Review. For. Policy Econ. 2025, 177, 103523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EC. A Sustainable Bioeconomy for Europe: Strengthening the Connection Between Economy, Society and the Environment: Updated Bioeconomy Strategy. Available online: https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/edace3e3-e189-11e8-b690-01aa75ed71a1 (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- Lovrić, N.; Lovrić, M.; Mavsar, R. Factors behind Development of Innovations in European Forest-Based Bioeconomy. For. Policy Econ. 2020, 111, 102079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietz, T.; Börner, J.; Förster, J.J.; von Braun, J. Governance of the Bioeconomy: A Global Comparative Study of National Bioeconomy Strategies. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinn, R.; Palátová, P.; Kalábová, M.; Jarský, V. Forest Bioeconomy from the Perspectives of Different EU Countries and Its Potential for Measuring Sustainability. Forests 2023, 14, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvador, R.; Barros, M.V.; Donner, M.; Brito, P.; Halog, A.; De Francisco, A.C. How to Advance Regional Circular Bioeconomy Systems? Identifying Barriers, Challenges, Drivers, and Opportunities. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2022, 32, 248–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barañano, L.; Unamunzaga, O.; Garbisu, N.; Briers, S.; Orfanidou, T.; Schmid, B.; de Arano, I.M.; Araujo, A.; Garbisu, C. Assessment of the Development of Forest-Based Bioeconomy in European Regions. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gawel, E.; Purkus, A.; Pannicke, N.; Hagemann, N. Die Governance Der Bioökonomie—Herausforderungen Einer Nachhaltigkeitstransformation Am Beispiel Der Holzbasierten Bioökonomie in Deutschland. 2016. Available online: http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-47319-9 (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Luhas, J.; Mikkilä, M.; Kylkilahti, E.; Miettinen, J.; Malkamäki, A.; Pätäri, S.; Korhonen, J.; Pekkanen, T.-L.; Tuppura, A.; Lähtinen, K.; et al. Pathways to a Forest-Based Bioeconomy in 2060 within Policy Targets on Climate Change Mitigation and Biodiversity Protection. For. Policy Econ. 2021, 131, 102551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falcone, P.M.; Tani, A.; Tartiu, V.E.; Imbriani, C. Towards a Sustainable Forest-Based Bioeconomy in Italy: Findings from a SWOT Analysis. For. Policy Econ. 2020, 110, 101910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rantala, S.; Swallow, B.; Lähteenmäki-Uutela, A.; Paloniemi, R. Forest Data Governance as a Reflection of Forest Governance: Institutional Change and Endurance in Finland and Canada. Environ. Sci. Policy 2022, 136, 751–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Amato, D.; Bartkowski, B.; Droste, N. Reviewing the Interface of Bioeconomy and Ecosystem Service Research. Ambio 2020, 49, 1878–1896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagy, E.; Rustas, C.B.; Mark-herbert, C. Social Acceptance of Forest-Based Bioeconomy—Swedish Consumers’ Perspectives on a Low Carbon Transition. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7628. [Google Scholar]

- Lovec, M.; Juvančič, L. The Role of Industrial Revival in Untapping the Bioeconomy’s Potential in Central and Eastern Europe. Energies 2021, 14, 8405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- JRC. EU Biomass Supply, Uses, Governance and Regenerative Actions; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2025; ISBN 978-92-68-28281-6. [Google Scholar]

- Lovrić, N.; Krajter Ostoić, S.; Vuletić, D.; Zavodja, M.; Đorđević, I.; Stojanovski, V.; Curman, M. The Future of the Forest-Based Bioeconomy in Selected Southeast European Countries. Futures 2021, 128, 102725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Börner, J.; Baylis, K.; Corbera, E.; Ezzine-de-Blas, D.; Honey-Rosés, J.; Persson, U.M.; Wunder, S. The Effectiveness of Payments for Environmental Services. World Dev. 2017, 96, 359–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auld, G.; Balboa, C.; Bernstein, S.; Cashore, B. The Emergence of Non-State Market-Driven (NSMD) Global Environmental Governance: A Cross-Sectoral Assessment; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2009; ISBN 9780511627170. [Google Scholar]

- Halonen, M.; Näyhä, A.; Kuhmonen, I. Regional Sustainability Transition through Forest-Based Bioeconomy? Development Actors’ Perspectives on Related Policies, Power, and Justice. For. Policy Econ. 2022, 142, 102775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Näyhä, A. Transition in the Finnish Forest-Based Sector: Company Perspectives on the Bioeconomy, Circular Economy and Sustainability. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 209, 1294–1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juvančič, L.; Berne, S.; Oven, P.; Osojnik Črnivec, I.G. Strategic Concept Paper for Bioeconomy in Slovenia: From a Patchwork of Good Practices to an Integrated, Sustainable and Robust Bioeconomy System. Open Res. Eur. 2023, 3, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SFS. Poročilo Zavoda Za Gozdove Slovenije o Gozdovih Za Leto 2024; Slovenia Forest Service: Ljubljana, Slovenia, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Verkerk, P.J.; Fitzgerald, J.B.; Datta, P.; Dees, M.; Hengeveld, G.M.; Lindner, M.; Zudin, S. Spatial Distribution of the Potential Forest Biomass Availability in Europe. For. Ecosyst. 2019, 6, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juvančič, L.; Arnič, D.; Berne, S.; Grilc, M.; Hočevar, B.; Humar, M.; Javornik, S.; Kocjan, D.; Kocjančič, T.; Krajnc, N.; et al. Zaključno Poročilo CRP Premostitev Vrzeli v Biogospodarstvu: Od Gozdne in Kmetijske Biomase Do Inovativnih Tehnoloških Rešitev; Biotehniška Fakulteta: Ljubljana, Slovenia, 2021. Available online: https://www.dlib.si/details/URN:NBN:SI:DOC-VYL09N6J (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- EC. EU Biodiversity Strategy for 2030. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=celex%3A52020DC0380 (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- EC. New EU Forest Strategy for 2030. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A52021DC0572 (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- Haines-Young, R.; Potschin, M. Common International Classification of Ecosystem Services (CICES): 2011 Update; Fabis Consulting Ltd.: Nottingham, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Winkler, I.; Medved, M. Spremembe Lastninske Strukture Gozdov Zaradi Denacionalizacije in Njihove Gozdnogospodarske Posledice. Zb. Gozdarstva Lesar. 1994, 44, 215–246. [Google Scholar]

- Pezdevšek Malovrh, Š. Vpliv Institucij in Oblik Povezovanja Lastnikov Gozdov Na Gospodarjenje z Zasebnimi Gozdovi. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Ljubljana, Biotehniška Fakulteta, Ljubljana, Slovenia, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Iveta, N. Ocena Pripravljenosti Zasebnih Lastnikov Gozdov Za Poslovno Sodelovanje Pri Gospodarjenju z Gozdom Na Primeru Revirja Vodice. Master’s Thesis, University of Ljubljana, Biotehniška Fakulteta, Ljubljana, Slovenia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Kumer, P. Vpliv Družbenogeografskih Dejavnikov Na Gospodarjenje z Majhnimi Zasebnimi Gozdnimi Posestmi. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Ljubljana, Biotehniška Fakulteta, Ljubljana, Slovenia, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Plevnik, K.; Pezdevšek Malovrh, Š. Analiza Delovanja Zveze Lastnikov Gozdov Slovenije s Ciljem Njenega Izboljšanja—Ali Obstajajo Možnosti Za Vzpostavitev Novih Poslovnih Modelov Sodelovanja s Člani? Acta Silvae Ligni 2021, 124, 13–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurmekoski, E.; Jonsson, R.; Korhonen, J.; Jänis, J.; Mäkinen, M.; Leskinen, P.; Hetemäki, L. Diversification of the Forest Industries: Role of New Wood-Based Products. Can. J. For. Res. 2018, 48, 1417–1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SPIRIT Slovenija. Lesno Predelovalna Industrija Ponuja Številne Karierne Priložnosti. Available online: https://www.spiritslovenia.si/sporocilo/705 (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- Government of Slovenia. Zakon o Gozdovih. Available online: https://pisrs.si/pregledPredpisa?id=ZAKO270 (accessed on 3 March 2025).

- Redek, T.; Oblak, L.; Humar, M. Analiza Uspešnosti Lesne Industrije v Sloveniji in Dejavnikov, ki Nanjo Vplivajo [Analysis of the Performance of the Wood Industry in Slovenia and the Factors Affecting It]. Les/Wood 2025, 74, 41–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SURS. Ekonomski Računi Za Gozdarstvo Po Proizvodih in Vrednostih, Slovenija, Letno. Available online: https://pxweb.stat.si/SiStatData/pxweb/sl/Data/-/1622730S.px/ (accessed on 17 December 2025).

- Vedel, S.E.; Jacobsen, J.B.; Thorsen, B.J. Forest Owners’ Willingness to Accept Contracts for Ecosystem Service Provision is Sensitive to Additionality. Ecol. Econ. 2015, 113, 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plevnik, K.; Japelj, A. Uncovering the Latent Preferences of Slovenia’s Private Forest Owners in the Context of Enhancing Forest Ecosystem Services through a Hypothetical Scheme. Forests 2023, 14, 2346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezzine-De-Blas, D.; Wunder, S.; Ruiz-Pérez, M.; Del Pilar Moreno-Sanchez, R. Global Patterns in the Implementation of Payments for Environmental Services. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0149847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grilli, G.; Fratini, R.; Marone, E.; Sacchelli, S. A Spatial-Based Tool for the Analysis of Payments for Forest Ecosystem Services Related to Hydrogeological Protection. For. Policy Econ. 2020, 111, 102039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, E.A.; Buckwell, A.; Guidi, C.; Garcia, B.; Rimmer, L.; Cadman, T.; Mackey, B. Capturing Multiple Forest Ecosystem Services for Just Benefit Sharing: The Basket of Benefits Approach. Ecosyst. Serv. 2022, 55, 101421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malkamäki, A.; Korhonen, J.E.; Berghäll, S.; Berg Rustas, C.; Bernö, H.; Carreira, A.; D’Amato, D.; Dobrovolsky, A.; Giertliová, B.; Holmgren, S.; et al. Public Perceptions of Using Forests to Fuel the European Bioeconomy: Findings from Eight University Cities. For. Policy Econ. 2022, 140, 102749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Primmer, E.; Varumo, L.; Krause, T.; Orsi, F.; Geneletti, D.; Brogaard, S.; Aukes, E.; Ciolli, M.; Grossmann, C.; Hernández-Morcillo, M.; et al. Mapping Europe’s Institutional Landscape for Forest Ecosystem Service Provision, Innovations and Governance. Ecosyst. Serv. 2021, 47, 101225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodge, D.; Brukas, V.; Giurca, A. Forests in a Bioeconomy: Bridge, Boundary or Divide? Scand. J. For. Res. 2017, 32, 582–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelli, P.; Haapala, A.; Pykäläinen, J. Services in the Forest-Based Bioeconomy—Analysis of European Strategies. Scand. J. For. Res. 2017, 32, 559–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toppinen, A.; D’Amato, D.; Stern, T. Forest-Based Circular Bioeconomy: Matching Sustainability Challenges and Novel Business Opportunities? For. Policy Econ. 2020, 110, 102041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarský, V.; Dobšinská, Z.; Hrib, M.; Oliva, J.; Sarvašová, Z.; Šálka, J. Restitution of Forest Property in the Czech Republic and Slovakia—Common Beginnings with Different Outcomes? Cent. Eur. For. J. 2018, 64, 195–206. [Google Scholar]

- Pezdevšek Malovrh, Š.; Laktić, T. Poslovno Povezovanje Lastnikov Gozdov Na Primeru Društva Lastnikov Gozdov Pohorje-Kozjak. Acta Silvae Ligni 2017, 113, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palatova, P. Sharing Economy in the Forestry Sector: Opportunities and Barriers. For. Policy Econ. 2023, 154, 103000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovec, M.; Juvančič, L.; Mešl, M. Družbeni Kontekst Prehoda v Biogospodarstvo: CRP V4-1824, R.1.1; Univerza v Ljubljani: Ljubljana, Slovenia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- National Bioeconomy Strategies in Europe—State of Play July 2025; European Commission’s Knowledge Centre for Bioeconomy: Brussels, Belgium, 2025.

- Arnič, D.; Loizou, E.; Ščap, Š.; Prislan, P.; Juvančič, L. Evaluating Alternative Transformation Pathways of Wood-Based Bioeconomy: Application of an Input–Output Model. Forests 2024, 15, 2084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BIOeast. Ensuring Biomass Supply: A Cornerstone for Europe’s Bioeconomy. Available online: https://bioeast.eu/ensuring-biomass-supply-a-cornerstone-for-europes-bioeconomy/ (accessed on 13 December 2025).

- Uhan, Z.; Dobšinská, Z.; Báliková, K.; Malovrh, Š.P. Policy Change through the Lens of Private Forest Owners’ Business Cooperation: A Case Study of Slovenia and Slovakia. Cent. Eur. For. J. 2025, 71, 307–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnič, D.; Prislan, P.; Juvančič, L. Raba Lesa v Slovenskem Biogospodarstvu. Gozdarski Vestn. 2019, 77, 375–393. [Google Scholar]

- Malovrh, Š.P.; Kurttila, M.; Hujala, T.; Kärkkäinen, L.; Leban, V.; Lindstad, B.H.; Peters, D.M.; Rhodius, R.; Solberg, B.; Wirth, K.; et al. Decision Support Framework for Evaluating the Operational Environment of Forest Bioenergy Production and Use: Case of Four European Countries. J. Environ. Manag. 2016, 180, 68–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brašanac, L.; Čule, N.; Đorđević, I.; Češljar, G.; Mitrović, T.Ć. Possibilities for the Use of Biomass from Forestry with the Aim of Establishing a Circular Bioeconomy in Serbia. Sustain. For. Collect. 2023, 87–88, 183–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nedić, Z.; Ivan, A.; Ivan, J.; Bošković, A.; Cestarić, D.; Biljana, K. From the Wood-Based Community to the Circular, Carbon-Neutral and Sustainable Bioeconomy: Recommendations for the Transition. J. Sustain. Dev. Energy Water Environ. Syst. 2024, 12, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galantari, V.; Panailidou, K. National Results from the Analysis on “High-Level Study of Regional Dynamics”—Czech Republic; BBioNets: Brno, Czech Republic, 2025; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Filipe, S. A Review on Strategies, Policies and Mechanisms Supporting Bioeconomy and Sustainable Development. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Water Energy Food and Sustainability, Leiria, Portugal, 10–12 May 2023; pp. 601–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogner, K. Knowledge Networks in the German Bioeconomy: Network Structure of Publicly Funded R&D Networks. In Hohenheim Discussion Papers in Business, Economics and Social Sciences 03-2019; Universität Hohenheim, Fakultät Wirtschafts und Sozialwissenschaften: Stuttgart, Deutschland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Zilberman, D.; Wesseler, J. Building the Bioeconomy through Innovation, Monitoring and Science-Based Policies. EuroChoices 2023, 22, 21–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grande, M. Public Engagement and Education Can Support the Transition towards Sustainable Bioeconomy. J. Sci. Policy Gov. 2022, 20, 2016–2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firdaus, F. Green Product Purchase Decision: The Role of Environmental Consciousness and Willingness to Pay. J. Apl. Manaj. 2023, 21, 1045–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawal, D.; Aryal, B.R. Consumer Awareness of Green Marketing and Buying Behavior: A Synthesis of Literature. Contemp. Res. Interdiscip. Acad. J. 2024, 7, 51–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surianshah, S. Environmental Awareness and Green Products Consumption Behavior: A Case Study of Sabah State, Malaysia. Biodiversitas 2021, 22, 2685–2692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BIOECO-UP. Bioeconomy in ce Europe: Shared Experiences About the Bioeconomy from Europe! BIOECO-UP. Available online: https://www.bioeasthub.cz/images/doc/bioecoup/BIOECO-UP__brochure_infosheets_EN_240823.pdf (accessed on 12 December 2025).

- BIOECO-UP. High Interest in the Annual BIOEAST Conference—The BIOECO-UP Brochure Was a Success in the Education Thematic Working Group. Available online: https://www.interreg-central.eu/news/high-interest-in-the-annual-bioeast-conference-the-bioeco-up-brochure-was-a-success-in-the-education-working-group/?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 12 December 2025).

- EC. Guidance on the Development of Public and Private Payment Schemes for Forest Ecosystem Services. Available online: https://agriculture.ec.europa.eu/system/files/2023-07/guidance-dev-public-private-payment-schemes-forest_en.pdf (accessed on 5 March 2025).

- DEFRA. Payments for Ecosystem Services: A Best Practice Guide. Available online: https://ecosystemsknowledge.net/sites/default/files/wp-content/uploads/pb13932a-pes-bestpractice-annexa-20130522.pdf (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Fripp, E. Payments for Ecosystem Services (PES): A Practical Guide to Assessing the Feasibility of PES Projects; CIFOR: Bogor, Indonesia, 2014; ISBN 9786021504574. [Google Scholar]

- UNDP. Designing a Digital System to Enable Payment for Ecosystem Services (PES) at Scale—Taking a Digital Public Good (DPG) Approach to Enhance Nature and Climate Action; UNDP: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 1–47. [Google Scholar]

- Förster, J.J.; Downsborough, L.; Chomba, M.J. When Policy Hits Practice: Structure, Agency, and Power in South African Water Governance. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2017, 30, 521–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malovrh, Š.P.; Nonić, D.; Glavonjić, P.; Nedeljković, J.; Avdibegović, M.; Krč, J. Private Forest Owner Typologies in Slovenia and Serbia: Targeting Private Forest Owner Groups for Policy Implementation. Small-Scale For. 2015, 14, 423–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ščap, Š.; Stare, D.; Krajnc, N.; Triplat, M. Značilnosti Opravljanja Sečnje in Spravila v Zasebnih Gozdovih v Sloveniji. Acta Silvae Ligni 2021, 125, 25–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SFS. Lastništvo Gozdov. Available online: https://www.zgs.si/gozdovi-slovenije/lastnistvo-gozdov (accessed on 22 May 2025).

- Mavsar, R.; Japelj, A.; Kovač, M. Trade-Offs between Fire Prevention and Provision of Ecosystem Services in Slovenia. For. Policy Econ. 2013, 29, 62–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindstad, B.H.; Pistorius, T.; Ferranti, F.; Dominguez, G.; Gorriz-Mifsud, E.; Kurttila, M.; Leban, V.; Navarro, P.; Peters, D.M.; Pezdevsek Malovrh, S.; et al. Forest-Based Bioenergy Policies in Five European Countries: An Explorative Study of Interactions with National and EU Policies. Biomass Bioenergy 2015, 80, 102–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laktic, T.; Žiberna, A.; Kogovšek, T.; Malovrh, Š.P. Stakeholders’ Social Network in the Participatory Process of Formulation of Natura 2000 Management Programme in Slovenia. Forests 2020, 11, 332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wunder, S. Revisiting the Concept of Payments for Environmental Services. Ecol. Econ. 2015, 117, 234–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barton, D.N.; Benavides, K.; Chacon-Cascante, A.; Le Coq, J.F.; Quiros, M.M.; Porras, I.; Primmer, E.; Ring, I. Payments for Ecosystem Services as a Policy Mix: Demonstrating the Institutional Analysis and Development Framework on Conservation Policy Instruments. Environ. Policy Gov. 2017, 27, 404–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez de Francisco, J.C.; Boelens, R. Payment for Environmental Services: Mobilising an Epistemic Community to Construct Dominant Policy. Environ. Polit. 2015, 24, 481–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costedoat, S.; Koetse, M.; Corbera, E.; Ezzine-de-Blas, D. Cash Only? Unveiling Preferences for a PES Contract through a Choice Experiment in Chiapas, Mexico. Land Use Policy 2016, 58, 302–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sainz-Santamaria, J. Calibrating Payment for Ecosystem Services: A Process-Oriented Policy Design Approach. Policy Des. Pract. 2024, 7, 158–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, N.; Wunder, S. Fresh Tracks in the Forest: Assessing Incipient Payments for Environmental Services Initiatives in Bolivia; CIFOR: Bogor, Indonesia, 2005; ISBN 9793361816. [Google Scholar]

- Wunder, S. Payments for Environmental Services: Some Nuts and Bolts; CIFOR: Bogor, Indonesia, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, B.S. Corporate Payments for Ecosystem Services in Theory and Practice: Links to Economics, Business, and Sustainability. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, J.H.; Presnall, C.K.; López-Hoffman, L.; Nabhan, G.P.; Knight, R.L.; Ruyle, G.B.; Toombs, T.P. Beef and beyond: Paying for Ecosystem Services on Western US Rangelands. Rangelands 2011, 33, 4–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosenius, A.K.; Juutinen, A.; Tyrväinen, L. The Role of State-Owned Commercial Forests and Firm Features in Nature-Based Tourism Business Performance. Silva Fenn. 2020, 54, 10051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, S.; Simpson, M.; Tyrväinen, L.; Sievänen, T.; Pröbstl, U. (Eds.) European Forest Recreation and Tourism: A Handbook, 1st ed.; Taylor & Francis: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Mäntymaa, E.; Juutinen, A.; Tyrväinen, L.; Karhu, J.; Kurttila, M. Participation and Compensation Claims in Voluntary Forest Landscape Conservation: The Case of the Ruka-Kuusamo Tourism Area, Finland. J. For. Econ. 2018, 33, 14–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Yao, Z.; Guo, Z. Willingness to Pay and Preferences for Rural Tourism Attributes among Urban Residents: A Discrete Choice Experiment in China. Econ. Anal. Policy 2023, 77, 460–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, I.D.; Croft, D.B.; Green, R.J. Nature Conservation and Nature-Based Tourism: A Paradox? Environments 2019, 6, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farkic, J.; Isailovic, G.; Taylor, S. Forest Bathing as a Mindful Tourism Practice. Ann. Tour. Res. Empir. Insights 2021, 2, 100028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Näyhä, A. Finnish Forest-Based Companies in Transition to the Circular Bioeconomy—Drivers, Organizational Resources and Innovations. For. Policy Econ. 2020, 110, 101936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, E.; Hoen, H.F.; Nybakk, E. Competitive Advantage for the Forest-Based Sector in the Future Bioeconomy—Research Question Priority. Bioprod. Bus. 2018, 3, 15–28. [Google Scholar]

- Björkdahl, J.; Börjesson, S. Organizational Climate and Capabilities for Innovation: A Study of Nine Forest-Based Nordic Manufacturing Firms. Scand. J. For. Res. 2011, 26, 488–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Brusselen, J.; Mosley, F.; Cramm, M.; Tuomasjukka, D. Companies’ Innovation Approaches and Barriers towards Achieving Their Potential in the Forest-Based Bioeconomy. Scand. J. For. Res. 2025, 40, 303–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacevičiūtė, A.; Razbadauskaitė-Venskė, I. The Role of Green Marketing in Creating a Sustainable Competitive Advantage. Reg. Form. Dev. Stud. 2023, 2, 89–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Strategic Goals of EU Forest-Related Policies | ES (CICES) | Selected FBE-Related Aspects |

|---|---|---|

| Replacing carbon-intensive materials through the production of long-lived wood products | Provisioning | High-quality wood |

| Adaptation to climate change | Regulation & maintenance | Non-native tree species |

| Promotion of other sectors of the BE and creation of new green jobs | Cultural | Forest tourism |

| Biodiversity conservation | Regulation & maintenance | Biodiversity conservation |

| Stakeholder Group | Sector/Orientation | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Policymakers | n | % | |

| Forestry sector (polFOR) | 10 | 28.6% | |

| Wood industry sector (polWOOD) | 6 | 17.1% | |

| Environmental sector (polENV) | 9 | 25.7% | |

| Forest tourism sector (polTOUR) | 10 | 28.6% | |

| Total | 35 | ||

| Business representatives | n | % | |

| Primary wood production (PWP) | 5 | 20.8% | |

| Wood processing and products (WPP) | 10 | 41.7% | |

| Forest tourism (FT) | 9 | 37.5% | |

| Total | 24 |

| Policymakers | Businesses | Test of Differences | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| STATEMENT | Avg. (Mean) | Avg. (Median) | polFOR | polWOOD | PWP | WPP | K–W Test (p) | Pairwise Differences (Dunn, p.adj) | Cliff’s δ (95% CI) |

| A. Forest tending (thinning) can improve the quality of wood. | 4.4 | 5 | 4.0 | 5.0 | 4.0 | 5.0 | n.s. | / | / |

| B. Wood should be used as much as possible as sustainable wood products with higher added value. | 4.5 | 5 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 4.5 | n.s. | / | / |

| C. Only wood that is not suitable for sustainable wood products should be used for energy production (fuelwood). | 3.9 | 4 | 3.5 | 4.5 | 4.0 | 4.5 | n.s. | / | / |

| D. Wood can equally replace some other carbon-intensive building materials (concrete, PVC, aluminum, steel, etc.). | 4.1 | 4 | 4.0 | 4.0 | 4.0 | 5.0 | ** | PWP < WPP (0.03) | 0.82 (0.44, 0.95) |

| E. The use of wood in construction can reduce greenhouse gas emissions. | 4.6 | 5 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | n.s. | / | / |

| F. Other man-made materials can be more long-lived than wood. | 3.3 | 3 | 3.0 | 3.5 | 4.0 | 3.0 | n.s. | / | / |

| G. The use of man-made materials keeps forests intact. | 2.0 | 2 | 1.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 | n.s. | / | / |

| Policymakers | Businesses | Test of Differences | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| STATEMENT | Avg. (Mean) | Avg. (Median) | polFOR | polWOOD | polENV | PWP | WPP | K–W Test (p) | Pairwise Differences (Dunn, p.adj) | Cliff’s δ (95% CI) |

| A. Spruce is the second most common tree species in our country and should continue to be the one on which the wood processing industry is based in the future. | 2.6 | 3 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 2.0 | 3.0 | 3.0 | ** | polFOR > polENV (0.07) | 0.66 [0.14, 0.89] |

| polWOOD > polENV (0.03) | 0.83 [0.36, 0.97] | |||||||||

| polENV < WPP (0.06) | −0.66 [−0.90, −0.11] | |||||||||

| B. We should plant as many different tree species as possible to increase the resilience of forests to climate change and extreme weather events. | 3.9 | 4 | 4.0 | 3.0 | 4.0 | 4.0 | 4.0 | n.s. | / | |

| C. Some non-native tree species may be more resilient to extreme weather events and pests than native species. | 3.5 | 4 | 4.0 | 5.0 | 2.0 | 4.0 | 3.5 | ** | polWOOD > polENV (0.01) | 0.78 [0.24, 0.95] |

| D. Non-native tree species pose a threat to our forests. | 3.4 | 3 | 3.0 | 2.5 | 4.0 | 3.0 | 3.0 | * | polWOOD < polENV (0.06) | −0.72 [−0.94, −0.07] |

| E. Non-native tree species can significantly increase the timber increment in Slovenian forests. | 3.2 | 3 | 3.0 | 4.0 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 3.0 | n.s. | / | |

| F. Measures to adapt forests to climate change are not necessary because forests are able to adapt to climate change on their own. | 2.3 | 2 | 2.0 | 1.0 | 2.0 | 3.0 | 2.0 | n.s. | / | |

| G. Slovenian forestry faces other more important problems (ownership, economic aspects) than the adaptation of forests to climate change. | 2.1 | 2 | 2.0 | 1.5 | 1.0 | 3.0 | 2.5 | n.s. | / | |

| Policymakers (Medians) | Businesses (Medians) | Test of Differences | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| STATEMENT | Avg. (Mean) | Avg. (Median) | polFOR | polENV | polTOUR | FT | K–W Test (p) | Pairwise Differences (Dunn, p.adj) | Cliff’s δ (95% CI) |

| A. In addition to wood-based forestry, forests provide a number of equally important additional income opportunities, such as forest tourism. | 4.2 | 4.0 | 3.5 | 4.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | *** | polTOUR > polFOR (0.02) | 0.70 [0.23, 0.91] |

| polTOUR > polENV (0.08) | 0.64 [0.14, 0.88] | ||||||||

| B. The only profitable product of the forest is wood. | 1.7 | 1.0 | 2.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | ** | polFOR > polTOUR (0.03) | 0.69 [0.25, 0.89] |

| polFOR > FT (0.03) | −0.32 [−0.71, 0.23] | ||||||||

| C. Forest owners who focus solely on timber production should also recognize the potential of their forests for other service-oriented activities (e.g., tourism). | 3.8 | 4.0 | 4.0 | 4.0 | 4.0 | 4.0 | n.s. | / | |

| D. Tourism in the forest area only means additional management adjustments for the owner. | 2.5 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 3.0 | ** | polTOUR < polFOR (0.03) | −0.67 [−0.88, −0.23] |

| polFOR > polENV (0.11) | 0.61 [0.13, 0.86] | ||||||||

| E. Forest tourism should be developed in close cooperation with forest owners. | 4.4 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 4.0 | 5.0 | n.s. | / | |

| F. Forest tourism may have negative impacts on the condition of natural resources. | 3.4 | 3.0 | 4.0 | 4.0 | 3.0 | 3.0 | * | / | |

| G. Forest tourism may limit recreational space for local people. | 2.4 | 2.0 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 1.5 | 2.0 | * | / | |

| Policymakers (Medians) | Businesses (Medians) | Test of Differences | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| STATEMENT | Avg. (Mean) | Avg. (Median) | polFOR | polENV | polTOUR | FT | PWP | K–W Test (p) | Pairwise Differences (Dunn, p.adj) | Cliff’s δ (95% CI) |

| A. Biodiversity is the basis for a stable ecosystem. | 4.8 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 4.0 | ** | FT > PWP (0.06) | 0.60 [−0.06, 0.89] |

| B. Establishing protected habitats in managed forests helps forests survive over the long term. | 3.9 | 4.0 | 4.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 3.0 | ** | FT > polFOR (0.03) | 0.84 [0.25, 0.97] |

| FT > PWP (0.09) | 0.71 [0.02, 0.94] | |||||||||

| C. Timber from trees with high ecological value (old trees, trees with cavities, nest boxes, etc.) should not be used. | 4.0 | 4.0 | 3.5 | 5.0 | 4.5 | 4.0 | 4.0 | ** | polENV > polFOR (0.02) | 0.79 [0.35, 0.94] |

| polENV > PWP (0.05) | 0.87 [0.50, 0.97] | |||||||||

| D. Slovenia has a sufficient proportion of strictly protected forests (forest reserves). | 3.2 | 3.0 | 4.0 | 1.0 | 2.3 | 2.0 | 4.0 | * | polENV < PWP (0.05) | −0.76 [−0.95, −0.18] |

| E. Biodiversity can be maintained even if forests are logged at the same time. | 4.0 | 4.0 | 5.0 | 4.0 | 4.0 | 4.0 | 4.0 | n.s. | / | |

| F. Policymakers should be aware that different protection regimes that restrict logging may affect the income of forest owners. | 4.1 | 4.0 | 5.0 | 4.0 | 4.0 | 4.0 | 4.0 | *** | polFOR > polENV (0.03) | 0.67 [0.20, 0.89] |

| polFOR > polTOUR (0.02) | 0.80 [0.37, 0.95] | |||||||||

| polFOR > FT (0.03) | 0.67 [0.20, 0.89] | |||||||||

| G. It is correct that the state has the right to restrict forest management to private owners to promote biodiversity conservation. | 3.4 | 4.0 | 2.5 | 5.0 | 4.0 | 4.0 | 2.0 | *** | polENV > polFOR (0.01) | 0.86 [0.51, 0.96] |

| polENV > PWP (0.02) | 0.95 [0.73, 0.99] | |||||||||

| Economic Activity | Perceived Market Potential | |

|---|---|---|

| Mean | Median | |

| Primary wood production (PWP) | 5.0 | 5 |

| Wood processing and products (WPP) | 4.5 | 5 |

| Forest tourism (FT) | 4.0 | 4 |

| Avg. (Mean) | Avg. (Median) | Primary Wood Production (PWP) | Wood Processing and Products (WPP) | Forest Tourism (FT) | Kruskal–Wallis Test (p) | Dunn Test | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adaptability to sustainability trends | 4.17 | 4.00 | 4.00 | 4.00 | 5.00 | * | WPP < FT (p.adj = 0.09) |

| Access to quality wood/forest | 3.83 | 4.00 | 4.00 | 3.00 | 5.00 | ** | WPP < FT (p.adj = 0.01) |

| Link with the local environment | 3.75 | 4.00 | 4.00 | 3.00 | 5.00 | *** | WPP < FT (p.adj = 0.005) |

| More financing options (loans, green public procurement, etc.) | 3.04 | 3.00 | 2.00 | 4.00 | 2.00 | ** | WPP > FT (p.adj = 0.05); WPP > PWP (p.adj = 0.04) |

| Phase | polFOR | polTOUR | polENV | polWOOD |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Design and feasibility | 30.9% | 27.5% | 34.7% | 31.6% |

| Coordination and establishment | 22.2% | 22.5% | 22.2% | 18.4% |

| Realization | 22.2% | 28.8% | 19.4% | 26.3% |

| Monitoring and adjustment | 24.7% | 21.3% | 23.6% | 23.7% |

| Phase | polFOR | polTOUR | polENV | polWOOD | Kruskal–Wallis Test (p) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Design and feasibility | 2.50 | 2.20 | 2.78 | 2.00 | n.s. |

| Coordination and establishment | 1.80 | 1.80 | 1.78 | 1.17 | n.s. |

| Realization | 1.80 | 2.30 | 1.56 | 1.67 | n.s. |

| Monitoring and adjustment | 2.00 | 1.70 | 1.89 | 1.50 | n.s. |

| Form of Financing PES | % |

|---|---|

| Public sources: funds from the Common Agricultural Policy, EU Cohesion and Regional Funds, national/local budgets. | 32.9% |

| Private sources: businesses, the tourism sector (e.g., investing in nature conservation that attracts visitors), donors, private foundations | 27.6% |

| Public–private partnerships | 21.1% |

| User payments: households (paying for the ES they use) or tourists | 18.4% |

| Challenges in the Implementation of PES | % |

|---|---|

| Inactivity of forest owners or lack of interest in their forests | 15.1% |

| Fragmented land ownership | 14.3% |

| Conflicts of interest (state, owners, public, ecological goals) | 14.3% |

| Low payment amounts | 13.4% |

| Lack of a legal framework | 12.6% |

| Low awareness of the existence of PES among potential respondents | 11.8% |

| Short-term financing and lack of long-term secured funding | 10.1% |

| High transaction costs for operating PES | 5.0% |

| Time-consuming and costly collection of data on the state of ES or the effects of schemes | 3.4% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Plevnik, K.; Japelj, A. The Role of Policymakers and Businesses in Advancing the Forest-Based Bioeconomy: Perceptions, Challenges, and Opportunities. Sustainability 2026, 18, 219. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010219

Plevnik K, Japelj A. The Role of Policymakers and Businesses in Advancing the Forest-Based Bioeconomy: Perceptions, Challenges, and Opportunities. Sustainability. 2026; 18(1):219. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010219

Chicago/Turabian StylePlevnik, Kaja, and Anže Japelj. 2026. "The Role of Policymakers and Businesses in Advancing the Forest-Based Bioeconomy: Perceptions, Challenges, and Opportunities" Sustainability 18, no. 1: 219. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010219

APA StylePlevnik, K., & Japelj, A. (2026). The Role of Policymakers and Businesses in Advancing the Forest-Based Bioeconomy: Perceptions, Challenges, and Opportunities. Sustainability, 18(1), 219. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010219