Comparison of the Water Absorbability of Rocks and Composite-Cement Stones for Optimal Characterization of Sustainable Building Materials

Abstract

1. Introduction

Background

2. Materials and Methods

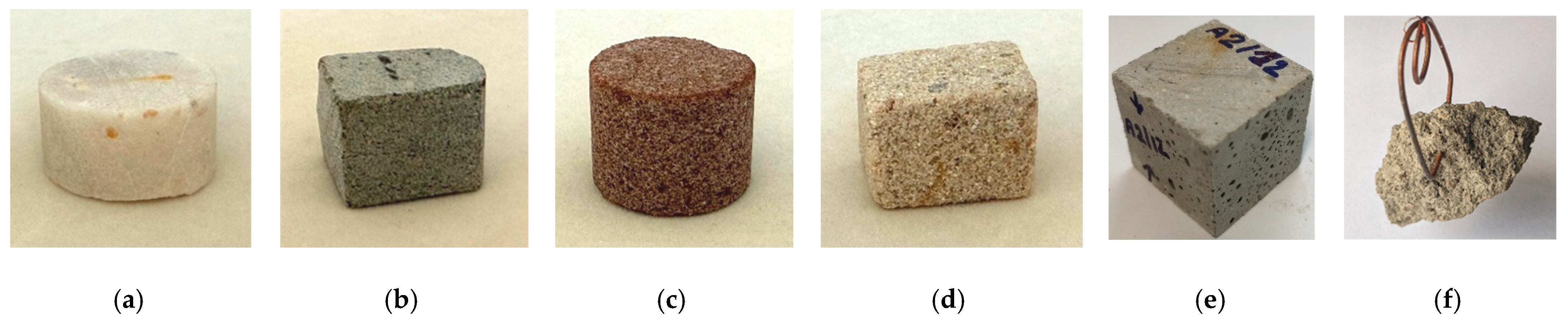

2.1. Samples

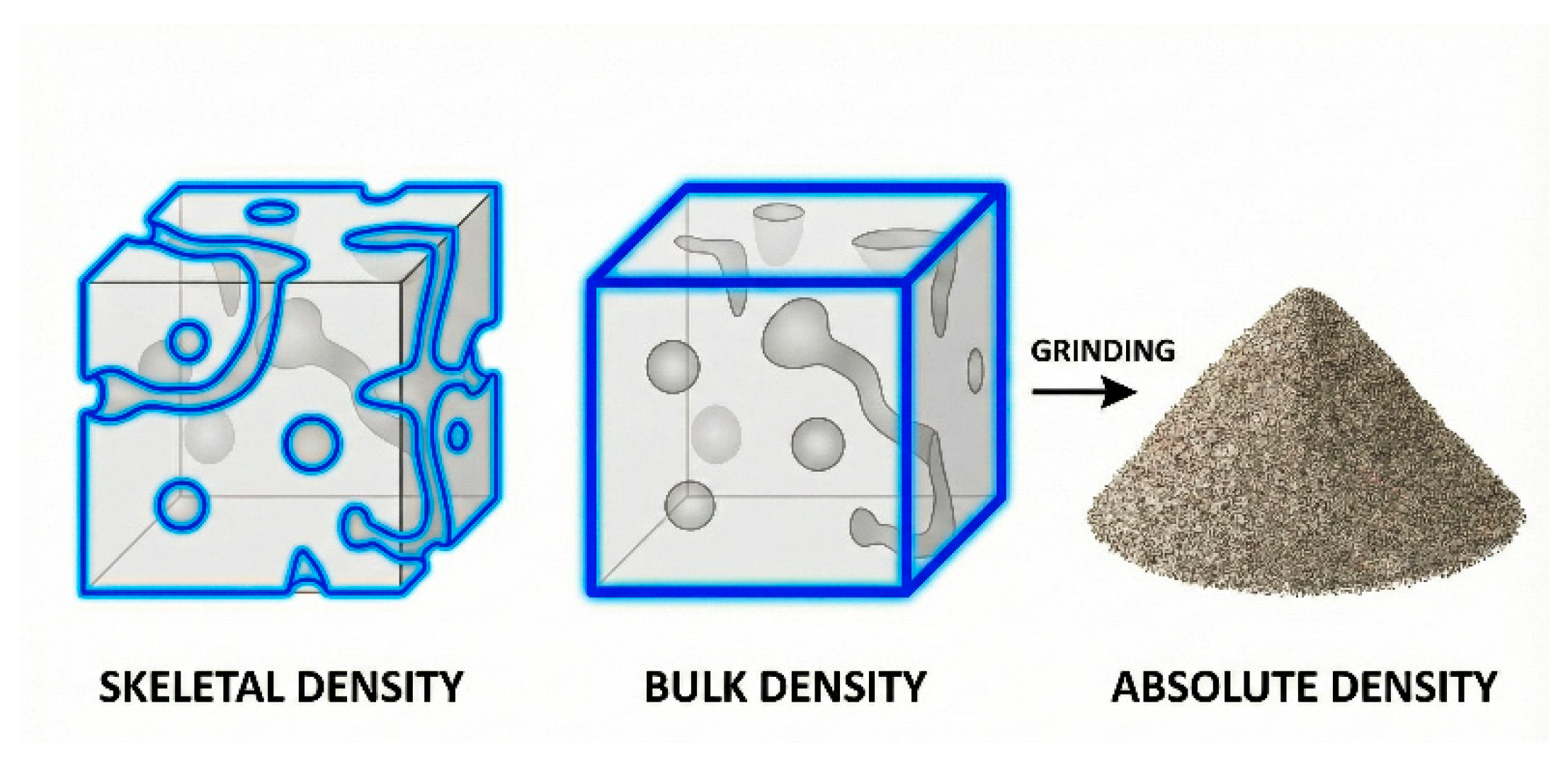

2.2. Hydrostatic Displacement Method

2.2.1. Experimental Setup for Bulk Density Measurement

- −

- Well absorbing the buoyancy liquid (e.g., sandstone, concrete);

- −

- Slightly absorbing the liquid (e.g., limestone, basalt);

- −

- Soluble in the liquid (e.g., salt in water) or materials that disintegrate in the liquid (e.g., clay in water);

- −

- Insoluble or slightly soluble in the liquid (e.g., limestone, marble).

2.2.2. Procedure

2.3. Additional Methods

3. Results

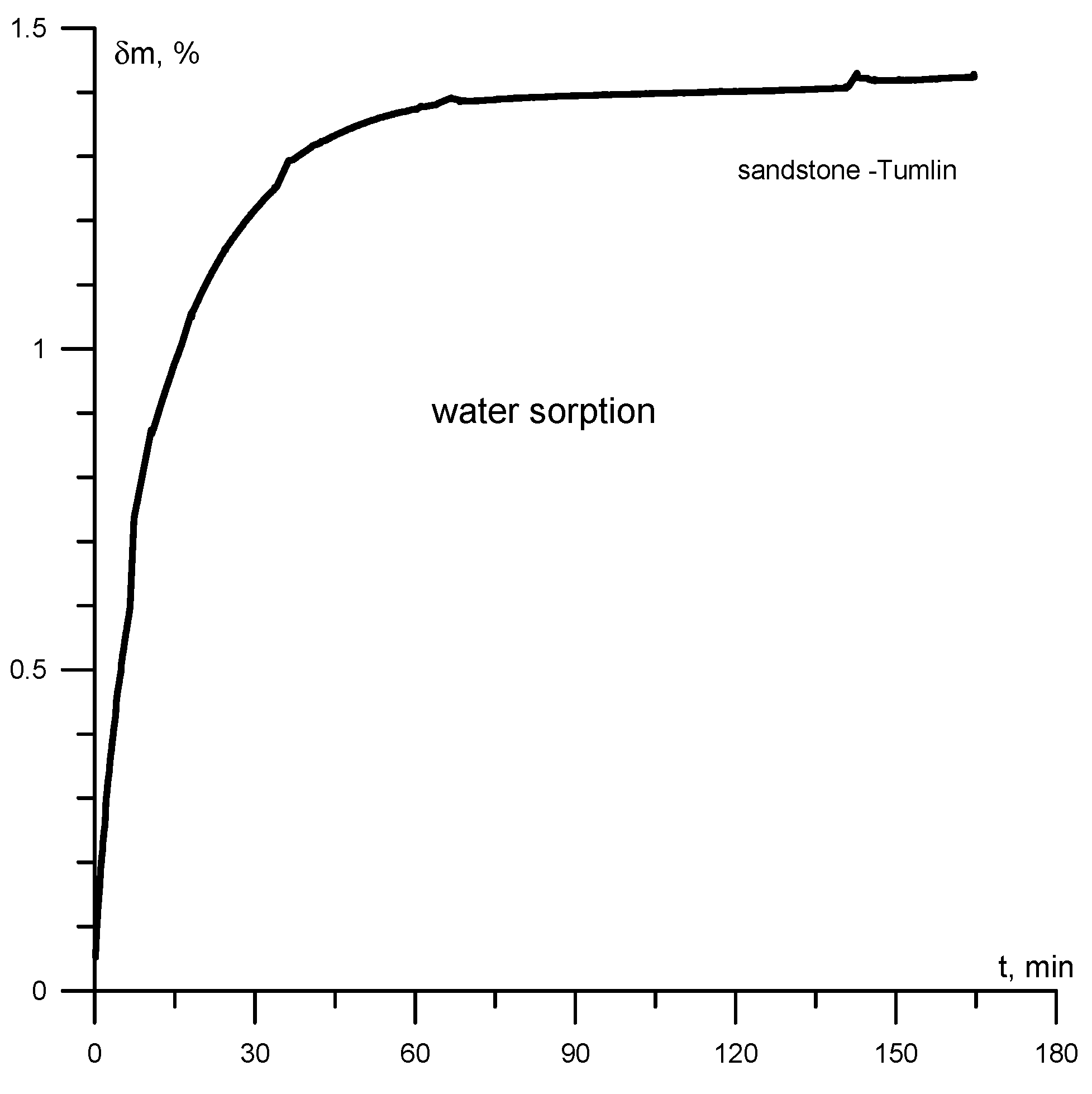

3.1. Water Saturation of Porous Sample Absorbing the Buoyancy Liquid

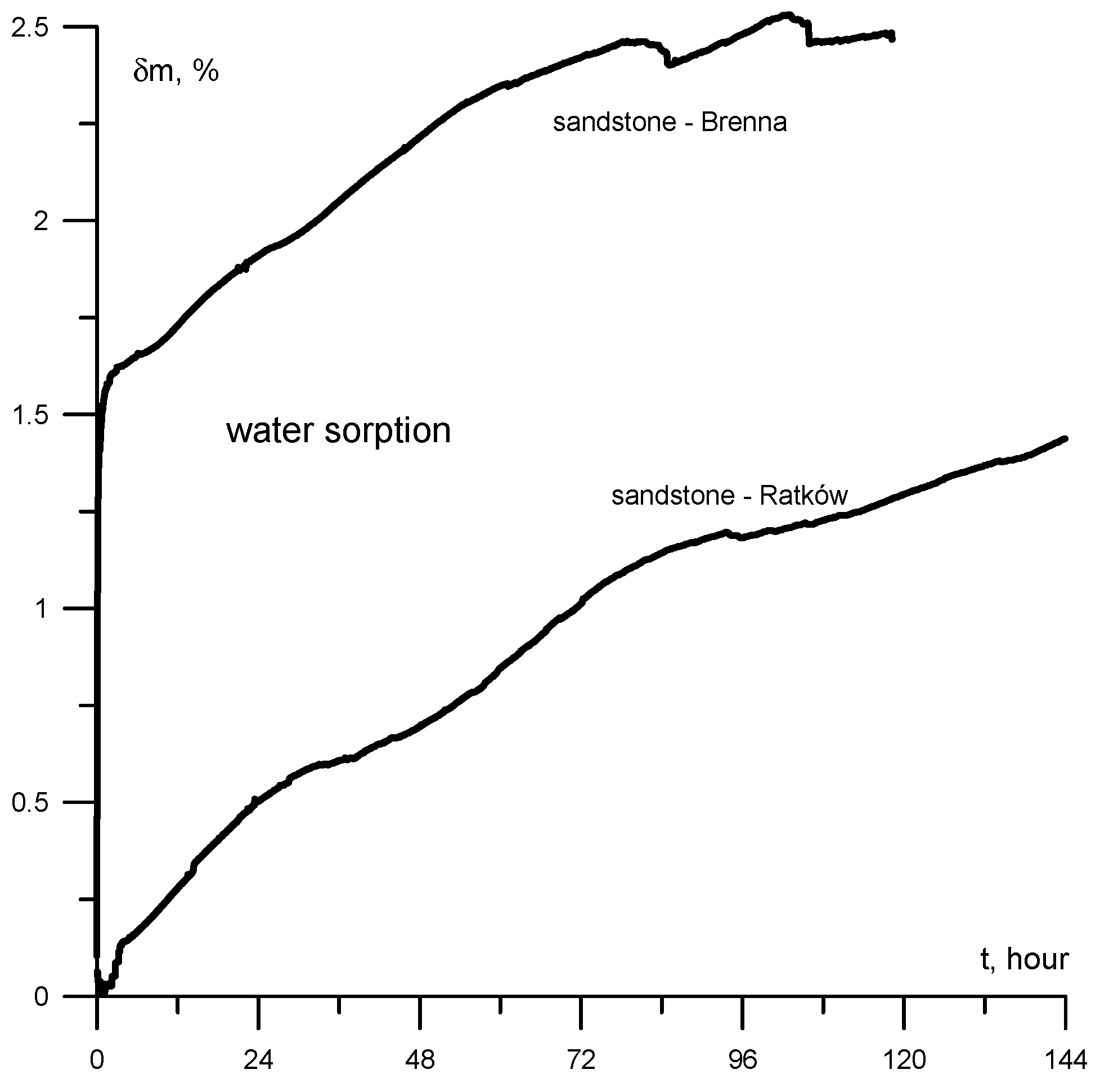

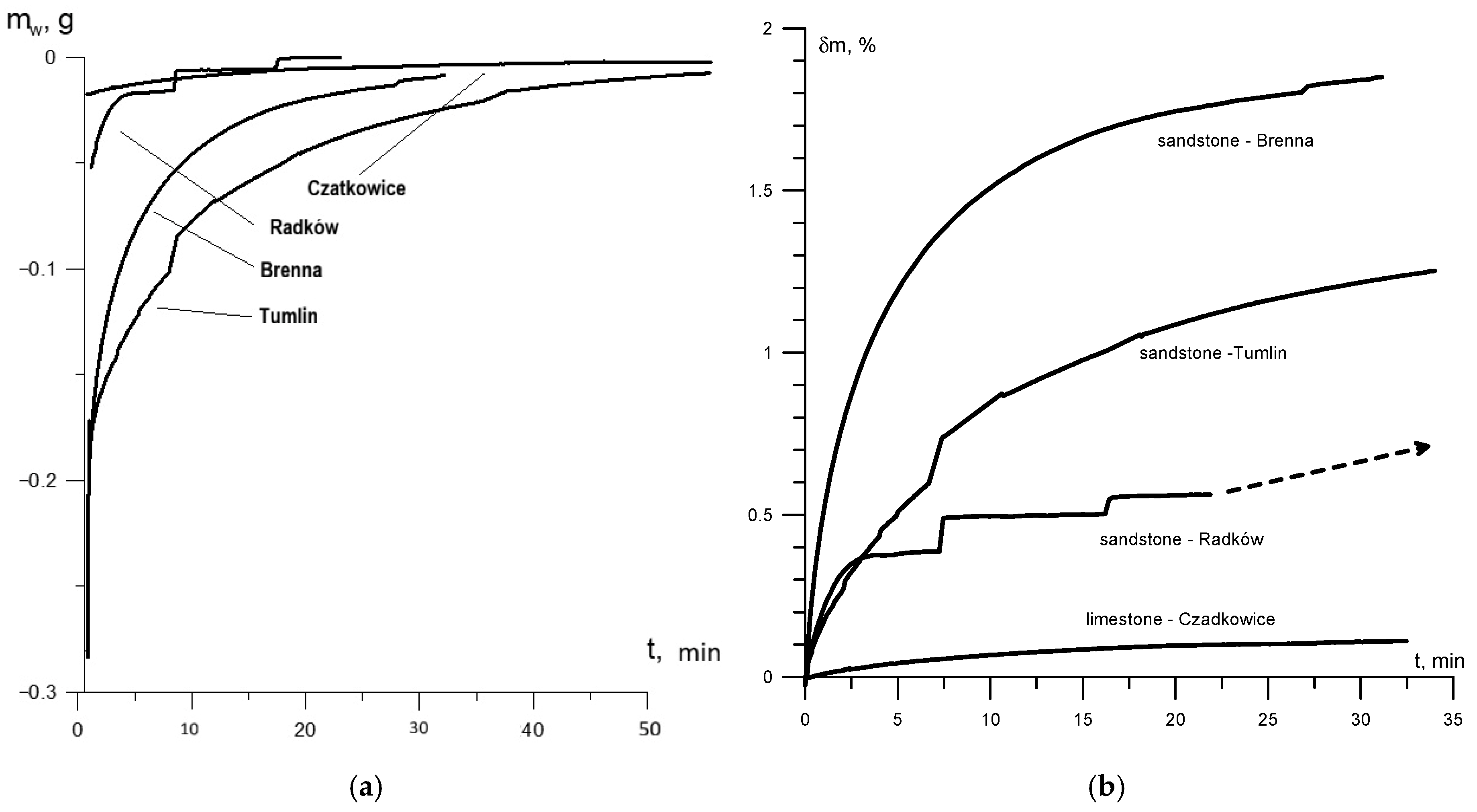

3.2. Studies of Porous Rock Samples

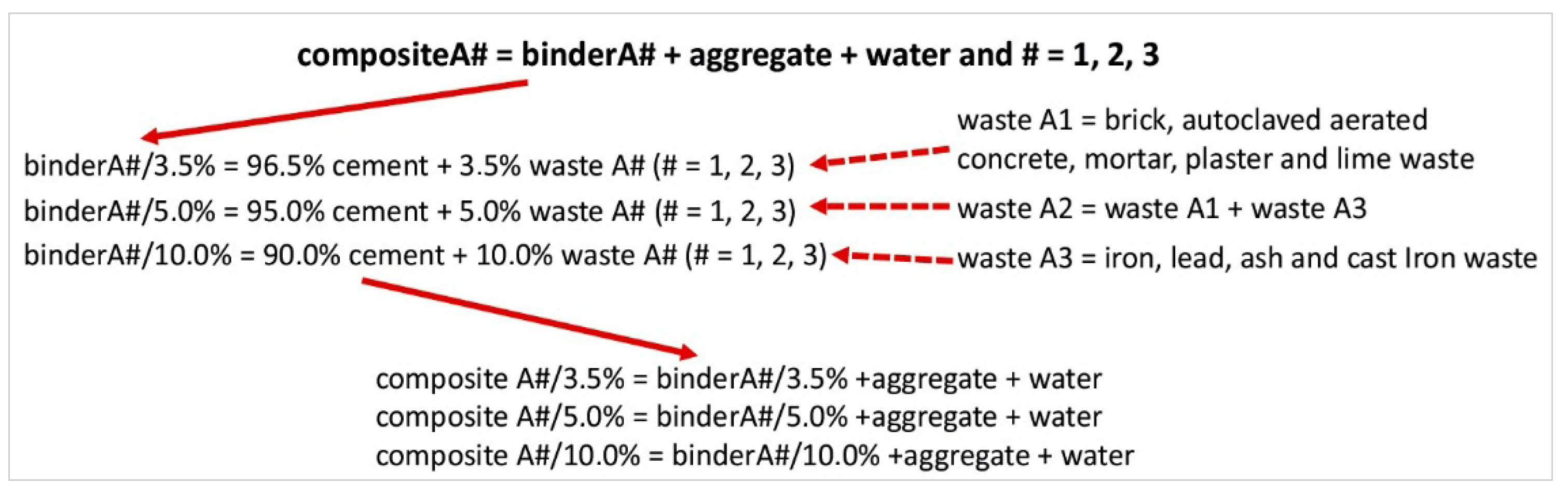

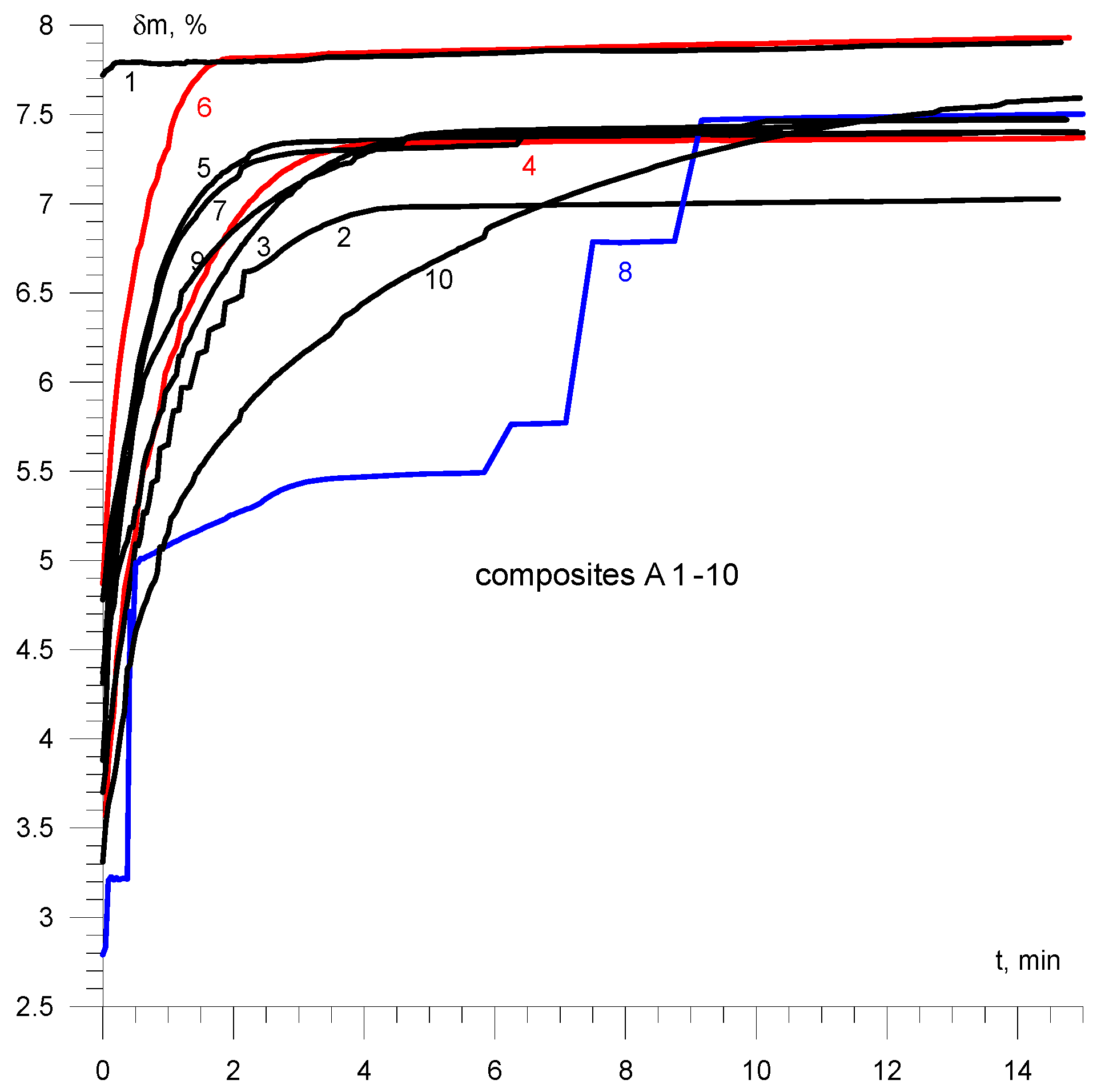

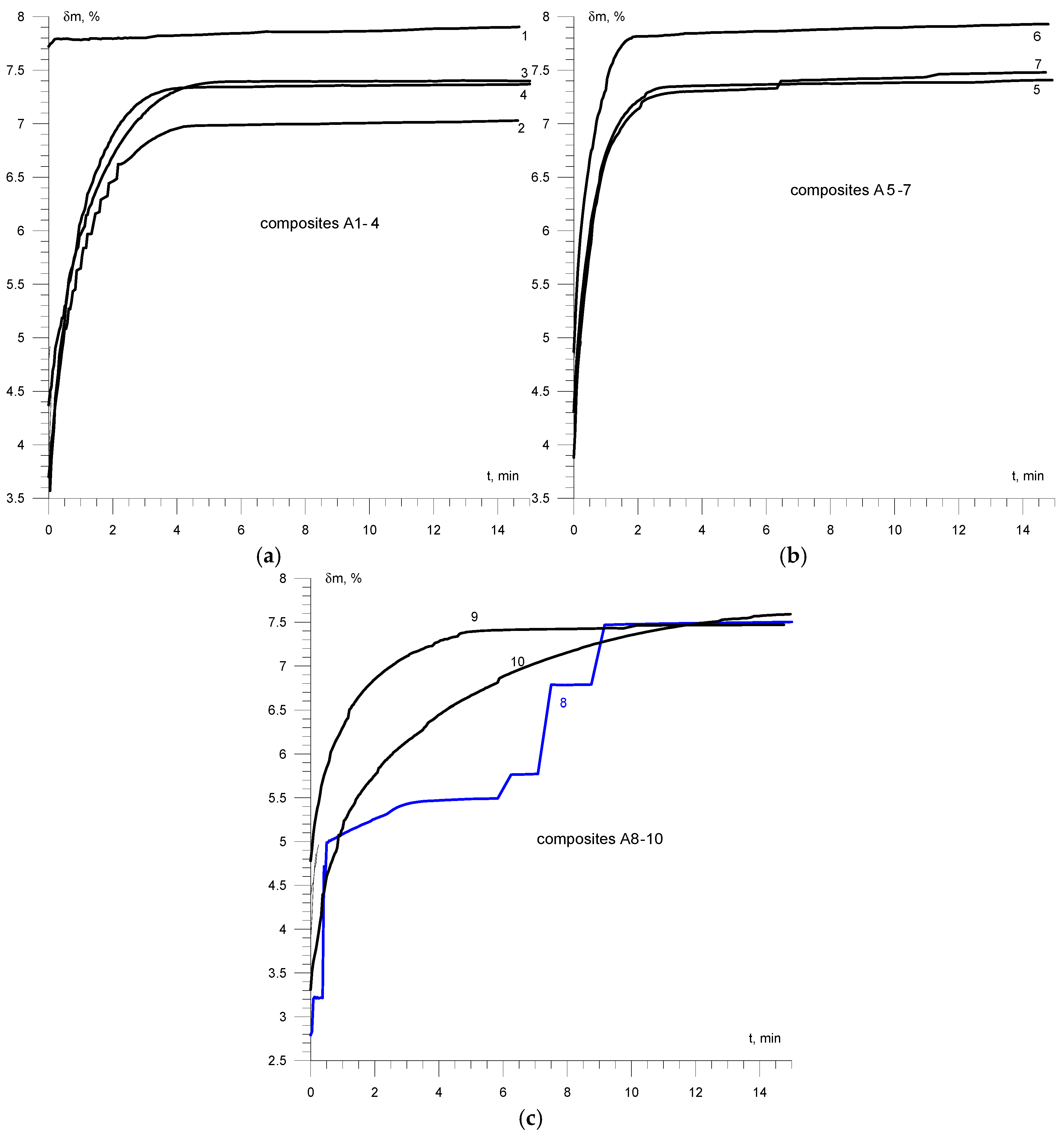

3.3. Porous Samples Absorbing Liquids—Composites

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tang, Z.; Li, W.; Tam, V.W.; Xue, C. Advanced progress in recycling municipal and construction solid wastes for manufacturing sustainable construction materials. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. X 2020, 6, 100036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, A.; Jha, K.N.; Misra, S. Use of aggregates from recycled construction and demolition waste in concrete. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2007, 50, 71–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutka, B.; Rada, S.; Godyń, K.; Moldovan, D.; Chelcea, R.I.; Tram, M. Structural and Textural Characteristics of Municipal Solid Waste Incineration Bottom Ash Subjected to Periodic Seasoning. Sustainability 2024, 16, 9597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Ye, X.; Cui, H. Recycled Materials in Construction: Trends, Status, and Future of Research. Sustainability 2025, 17, 2636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Yang, M.; Chen, Z.; Xie, Z.; Huang, L.; Osman, A.I.; Farghali, M.; Sandanayake, M.; Liu, E.; Ahn, Y.H.; et al. Conversion of waste into sustainable construction materials: A review of recent developments and prospects. Mater. Today Sustain. 2024, 27, 100930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safiuddin, M.; Alengaram, U.J.; Rahman, M.M.; Salam, M.A.; Jumaat, M.Z. Use of recycled concrete aggregate in concrete: A review. J. Civ. Eng. Manag. 2013, 19, 796–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rada, R.; Manea, D.L.; Chelcea, R.; Rada, S. Nanocomposites as Substituent of Cement: Structure and Mechanical Properties. Materials 2023, 16, 2398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tram, M.; Sułkowska, K.; Jarosz, A.; Nowakowski, A. Mechanical Properties of Composite Made from Bottom Ash Fractions of Municipal Waste Incineration Plant Products. Materials 2025, 18, 5302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahammed, M.R.; Mia, M.B.; Raihan, M.A.; Hossain, M.N.; Hossen, M.; Md Hasan, S. An Overview of Conventional Construction Materials And Their Characteristics. N. Am. Acad. Res. 2024, 7, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz-Marqués, A.; Caldevilla, P.; Goldmann, E.; Safuta, M.; Fernández-Raga, M.; Górski, M. Porosity and Permeability in Construction Materials as Key Parameters for Their Durability and Performance: A Review. Buildings 2025, 15, 3422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Zhou, W.; Hu, Q.H.; Xu, H.; Zhang, C. Porosity Measurement of Granular Rock Samples by Modified Bulk Density Analyses with Particle Envelopment. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2021, 133, 105273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mindaugas, A.; Karolis, B.; Dobilaitė, V.; Jucienė, M.; Artūras, S. Towards sustainable construction: Methodology for wood content assessment in buildings. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2025, 23, e05528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiu, E.S.K.; Ha, J.X.X.; Arashpour, M.; Raman, S.N. Hydration mechanism of cement-based composites incorporating ground pond ash: Towards sustainable building and infrastructure solutions. J. Build. Eng. 2025, 112, 113804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Takasu, K.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Z.; Suyama, H. Synergistic effects of mixed biomass fly ashes on cement mortar performance: A strategy for sustainable and low-carbon building materials. J. Build. Eng. 2025, 112, 113691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyebisi, S.; Alomayri, T. Revolutionizing eco-friendly concrete: Unleashing pulverized oyster shell and corncob ash as cement alternatives for sustainable building. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 484, 141776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firoozi, A.A.; Firoozi, A.A.; Oyejobi, D.O.; Avudaiappan, S.; Flores, E.S. Emerging trends in sustainable building materials: Technological innovations, enhanced performance, and future directions. Results Eng. 2024, 24, 103521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmona-Ramirez, J.D.; Bedoya-Henao, C.A.; Cabrera-Poloche, F.D.; Taborda-Llano, I.; Viana-Casas, G.A.; Restrepo-Baena, O.J.; Tobon, J.I. Exploring sustainable construction: A case study on the potential of municipal solid waste incineration ashes as building materials in San Andres island. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2025, 22, e04351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Dalbehera, M.M.; Maiti, S.; Bisht, R.S.; Balam, N.B.; Panigrahi, S.K. Investigation of agro-forestry and construction demolition wastes in alkali-activated fly ash bricks as sustainable building materials. Waste Manag. 2023, 159, 114–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, D.; Meyer, T.K.; Chen, S.; Boateng, K.A.; Pearce, J.M.; You, Z. Evaluation of lab performance of stamp sand and acrylonitrile styrene acrylate waste composites without asphalt as road surface materials. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 338, 127569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, J.; Khalloufi, S.; Martynenko, A.; Van Dalen, G.; Schutyser, M.; Almeida-Rivera, C. Porosity, Bulk Density, and Volume Reduction During Drying: Review of Measurement Methods and Coefficient Determinations. Dry. Technol. 2015, 33, 1681–1699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, S. Simplified Measurement of Density of Irregular Shaped Composites Material Using Archimedes Principle by Mixing Two Fluids Having Different Densities. Int. Res. J. Eng. Technol. 2021, 8, 1005–1009. [Google Scholar]

- Ledwaba, T.; Mbuyisa, B.; Blakey-Milner, B.; Steenkamp, C.; Du Plessis, A. X-Ray Computed Tomography vs Archimedes Method: A Head-to-Head Comparison. In MATEC Web of Conferences; Preez, W., Ed.; EDP Sciences: Les Ulis, France, 2023; Volume 388, p. 08002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohazzab, P. Archimedes’ Principle Revisited. J. Appl. Math. Phys. 2017, 05, 836–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EN 1936:2008; Natural Stone Test Methods Determination of Real Density and Bulk Density, and of Total and Open Porosity. European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 2008.

- EN ISO 10545-3:2018; Ceramic Tiles—Part 3: Determination of Water Absorption, Bulk Porosity, Bulk Relative Density and Bulk Density. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018.

- Abzalov, M.Z. Measuring and Modelling of Dry Bulk Rock Density for Mineral Resource Estimation. Appl. Earth Sci. 2013, 122, 16–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giesche, H. Mercury Porosimetry: A General (Practical) Overview. Part. Part. Syst. Charact. 2006, 23, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serway, R.; Jewett, J. Physics for Scientists and Engineers with Modern Physics; Thomson Higher Education: Belmont, CA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Smithwick, R.W. A Generalized Analysis for Mercury Porosimetry. Powder Technol. 1982, 33, 201–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurkowski, J.; Tram, M.; Dutka, B. Measurement of bulk density using the Archimedes method with an inductive spring balance. Metrol. Meas. Syst. 2025, 32, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Ren, S. (Eds.) Chapter 2—Basic Properties of Building Decorative Materials. In Building Decorative Materials; Woodhead Publishing Series in Civil and Structural Engineering; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2011; pp. 10–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM D570-22; Standard Test Method for Water Absorption of Plastics. American Society for Testing and Materials: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 1995.

- PN-88-B-04481; Grunty Budowlane. Badanie Próbek Gruntu. Badanie Wilgotności OPTYMALNEJ i Maksymalnej Gęstości Objętościowej Szkieletu Gruntowego. Polish Committee for Standardization: Warsaw, Poland, 1988.

- Ulusay, R.; Hudson, J.A. The Complete ISRM Suggested Methods for Rock Characterisation, Testing and Monitoring: 1974–2006; ISRM Turkish National Group: Ankara, Turkey, 2007; pp. 83–98. [Google Scholar]

- Godyń, K.; Dutka, B.; Tram, M. Application of Petrographic and Stereological Analyses to Describe the Pore Space of Rocks as a Standard for the Characterization of Pores in Slags and Ashes Generated after the Combustion of Municipal Waste. Materials 2023, 16, 7706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lech, R. Properties of the limestones and of the product of their thermal dissociation Part I. The limestones. Cem.-Wapno-Beton=Cem. Lime Concr. 2011, 16, 148–160. [Google Scholar]

- Yunlong, J.; Zhengzheng, C.; Zhenhua, L.; Feng, D.; Cunhan, H.; Haixiao, L.; Wenqiang, W.; Minglei, Z. Nonlinear evolution characteristics and seepage mechanical model of fluids in broken rock mass based on the bifurcation theory. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 10982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.; Zhang, W.; Guo, S.; Zhang, X.; Wang, L.; Zhang, J. Study on the energy evolution mechanism and fractal characteristics of coal failure under dynamic loading. ACS Omega 2025, 10, 54710−54719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Quartz | Feldspars | Rock Fragments | Calcite |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Czatkowice Limestone | - | - | - | 96% |

| Tumlin Sandstone | 90.7 | 2.8% | 6.4% | - |

| Brenna Sandstone | 73% | 18.9% | 7.9% | - |

| Radków Sandstone | 89% | 11% | 1% | - |

| Sample/Parameter | Mass [g] | Skeletal Density ρₛ | Mass Increase δm [%] | Bulk Density [g/cm3] | Measured Porosity [%] | Porosity Data [%] | Water Absorption Data [%] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Czatkowice limestone | 12.381 | 2.7238 | 0.020/12.381 = 0.16% | 2.6907 | 1.22 | 0.7 | low |

| Tumlin sandstone | 12.284 | 2.6665 | 0.28/12.284 = 2.3% | 2.4240 | 9.09 | 11.9 | 2.50% |

| Brenna sandstone | 9.64 | 2.6335 | 0.18/9.64 = 1.87% | 2.4660 | 6.36 | 7.5 | 2.53% |

| Radków sandstone | 9.15 | 2.5368 | 0.051/9 = 0.55% | 2.2011 | 13.23 | 15.1 | 4.45% |

| Sample Designation | Waste Type | Waste A Content [%] | Mass [g] | Skeletal Density Accupyc 1340 (Piece) [cm3/g] | Skeletal Density (Powder) [cm3/g] | Bulk Density Geopyc 1360 (Piece) [cm3/g] | Bulk Density Spring Balance (Piece) [cm3/g] | Picnometric Porosity [%] (Piece) | Spring Balance Open Porosity [%] (Piece) | Spring Balance Total Porosity [%] (Powder) | Spring Balance Closed Porosity [%] (Powder) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A1 | ST | 0 | 7.03 | 2.5379 | 2.5772 | 2.003 | 1.9972 | 21.08 | 21.31 | 22.51 | 1.20 |

| A2 | A1 | 3.5 | 7.63 | 2.578 | 2.595 | 1.758 | 2.0114 | 31.81 | 21.98 | 22.49 | 0.51 |

| A3 | 5 | 7.12 | 2.526 | 2.583 | 1.948 | 1.9944 | 22.88 | 21.05 | 22.79 | 1.74 | |

| A4 | 10 | 7.11 | 2.550 | 2.585 | 2.031 | 1.9941 | 20.35 | 21.80 | 22.86 | 1.06 | |

| A5 | A2 | 3.5 | 7.77 | 2.566 | 2.597 | 2.042 | 2.0240 | 20.42 | 21.12 | 22.06 | 0.94 |

| A6 | 5 | 7.16 | 2.531 | 2.595 | 2.032 | 1.9732 | 19.72 | 22.04 | 23.96 | 1.92 | |

| A7 | 10 | 7.05 | 2.615 | 2.627 | 1.808 | 1.9912 | 30.86 | 23.85 | 24.20 | 0.35 | |

| A8 | A3 | 3.5 | 7.49 | 2.594 | 2.594 | 1.967 | 2.0033 | 24.17 | 22.77 | 22.77 | 0.00 |

| A9 | 5 | 7.62 | 2.572 | 2.602 | 1.99 | 2.0155 | 22.63 | 21.64 | 22.54 | 0.90 | |

| A10 | 10 | 7.18 | 2.596 | 2.621 | 1.922 | 2.0652 | 25.96 | 20.45 | 21.21 | 0.76 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Dutka, B.; Nurkowski, J.; Tram, M.; Rada, S. Comparison of the Water Absorbability of Rocks and Composite-Cement Stones for Optimal Characterization of Sustainable Building Materials. Sustainability 2026, 18, 198. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010198

Dutka B, Nurkowski J, Tram M, Rada S. Comparison of the Water Absorbability of Rocks and Composite-Cement Stones for Optimal Characterization of Sustainable Building Materials. Sustainability. 2026; 18(1):198. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010198

Chicago/Turabian StyleDutka, Barbara, Janusz Nurkowski, Maciej Tram, and Simona Rada. 2026. "Comparison of the Water Absorbability of Rocks and Composite-Cement Stones for Optimal Characterization of Sustainable Building Materials" Sustainability 18, no. 1: 198. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010198

APA StyleDutka, B., Nurkowski, J., Tram, M., & Rada, S. (2026). Comparison of the Water Absorbability of Rocks and Composite-Cement Stones for Optimal Characterization of Sustainable Building Materials. Sustainability, 18(1), 198. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010198