1. Introduction

Preserving architectural heritage in times of climate crisis, rising construction material costs, and intensified urbanization is becoming an increasingly challenging task for urban policy and spatial planning [

1]. In addition to their historical and cultural value, historic buildings often serve practical functions as public institutions, dwellings, or commercial spaces. Their renovation requires the use of diagnostic methods that take into account both their unique structural character and contemporary requirements for safety, hygiene, and energy efficiency [

2,

3,

4].

Mycological and building surveys are playing an increasingly important role among essential diagnostic procedures. The purpose of such surveys is not only to detect biological hazards, such as fungi and mould, but also to assess the conditions conducive to their growth, including the moisture content of materials and the indoor microclimate [

5,

6]. In Poland, there are no uniform standards regulating the scope and manner of conducting these expert opinions, particularly with regard to historic buildings, resulting in significant differences in the quality of documentation and subsequent design recommendations.

Despite numerous studies on mycological diagnostics and the technical assessment of historic buildings, there is still a lack of research in the literature that clearly and quantitatively presents the economic consequences of errors made in selecting testing locations [

7,

8,

9]. Previous publications have mainly focused on technical, biological, and conservation aspects [

9], while the economic implications of these mistakes—particularly the direct impact of diagnostic errors on modernization costs—are poorly documented [

7]. In this context, the present study is significant as it combines technical analysis with a precise quantification of the financial burdens arising from the inappropriate selection of research sites and incomplete expert opinions.

The innovative aspect of this work lies in the economic quantification of the effects of diagnostic errors, a topic that has been only marginally addressed in existing literature, often in qualitative terms such as “increased costs” or “investment consequences.” This study defines cost increases as the difference between the estimated costs outlined in the tender documentation and the actual costs incurred during implementation, resulting from the discovery of untested or incorrectly assessed structural elements. This measurement encompasses direct labor and material costs, as well as indirect costs, including the need for repeated protective measures or additional laboratory analyses. The lack of a systematic and standardized approach to selecting sites for testing results in key structural elements being overlooked, such as external walls with preserved historic plaster, which are not verified during expert assessments due to the difficulty of exposing them [

5,

10]. As research shows, in the analyzed buildings, as much as 55–74% of significant parts of the building were not covered by research before the start of the investment, which led to the discovery of severe defects during the execution of works and an increase in costs by several dozen percent compared to the original budget [

5].

It is essential to recognize that inconsistent diagnostic standards represent a significant challenge, as highlighted in the recommendations of leading international organizations. The ICOMOS Principles for the Analysis, Conservation and Structural Restoration of Architectural Heritage [

11] emphasize the need for systematic diagnostic procedures, including accurate identification of test locations, careful documentation of degradation patterns, and the prioritization of non-destructive and minimally invasive techniques. Similarly, the RILEM TC 177-MDT recommendations for the in situ assessment of historic masonry [

12] emphasize the need for standardized methodologies in sampling, moisture testing, and material testing, as well as the evaluation of structural integrity. The CIB guidelines on non-destructive testing and building pathology [

13,

14] further stress the importance of unified diagnostic protocols to ensure comparability and reliability of expert assessments. Despite these international frameworks, the lack of binding national regulations in many countries, including Poland, results in considerable variability in diagnostic practice and affects the quality and completeness of technical documentation. Therefore, the present study contributes to the ongoing global discussion on the need to standardize diagnostic procedures and highlights the economic implications associated with inconsistent assessment practices. Although there are voices in the literature calling for the standardization of this type of research [

15], some authors argue that each expert assessment should be tailored to the specific nature of the building, which necessitates extensive experience and collaboration with the conservator of monuments [

16].

Among the legal documents regulating the obligation to carry out such expert assessments, it is worth mentioning, among others, the Regulation of the Minister of Infrastructure of 12 April 2002 [

10], which recommends that a mycological expert assessment be carried out in the event of dampness and biological corrosion being detected before modernization work begins. In addition, in accordance with the provisions of the Construction Law, owners and managers of buildings are required to carry out regular technical inspections, including biological assessments of the condition of walls [

17].

It is also important to note the guidelines of associations such as WTA (Wissenschaftlich-Technische Arbeitsgemeinschaft für Bauwerkserhaltung und Denkmalpflege), which specify the permissible levels of salt content in walls and moisture content in materials [

18]. European standards for microclimate and the protection of organic substances in historic buildings (e.g., EN 15757:2010 [

19] emphasize the monitoring of environmental changes that may affect the growth of fungi and microdamage to structures [

19].

Properly performed mycological and structural analyses of buildings should include an assessment of: visual appearance, wall strength (the capacity of the wall to withstand loads), thermal properties of partitions (the ability of dividing elements to insulate heat), dampness (presence of moisture), salinity (concentration of salts in materials), and corrosion of walls (damage caused by chemical reactions), as well as an assessment of the condition of the entire building and its individual elements [

18]. The scope of the research and research methods are presented in

Table 1.

When diagnosing buildings, the person performing the expert assessment should, based on their knowledge and experience, be able to select the appropriate locations for excavations and, if necessary, choose both destructive and non-destructive laboratory tests, as well as static and strength analysis calculations [

27]. In the case of visible cracks on the walls, it is crucial to assess the foundation conditions of the building, which is typically done through local foundation excavations. In special cases, it may be necessary to have geological and engineering documentation prepared by geologists [

28]. When conducting a building assessment for renovation or modernization, it is crucial to determine the thermal resistance of building partitions. The heat transfer coefficient (Equation (1)) for partitions is specified by the PN-EN ISO 6946:2008 standard [

21]. The calculations are based on the identification of the material of the element, its thickness, and the thermal conductivity coefficient, which enables the calculation of the thermal resistance -R

T (Equation (1)). Requirements are set for buildings where the value of the heat coefficient for a given partition cannot exceed the permissible value specified by the technical conditions, which is presented using the following formulas [

21]:

where

U—heat transfer coefficient [W/(m2·K)];

RT—total thermal resistance [(m2·K)/W];

R—thermal resistance of a layer [(m2·K)/W];

d—thickness of the material layer in the component [m];

λ—design thermal conductivity coefficient of the material [W/(m·K)];

Umax—maximum permissible heat transfer coefficient [W/(m2·K)].

In the context of an expert assessment of a historic building, it is imperative to ascertain the compressive strength of the masonry, which is contingent on the strength of the bricks and mortar. In the extant literature, Gruszczyński and Matysek [

29] posit that, following a comprehensive analysis of the formulae, ‘the compressive strength of bricks is the fundamental parameter for assessing the strength of a wall and has a considerably greater impact than the strength of mortar’ [

30]. The most realistic outcomes of masonry testing are obtained from large-format destructive samples; however, this testing method has a detrimental effect on the stability of building structures, which is why it is rarely performed. Its application is restricted to instances where the demolition of masonry elements in a building is part of a planned structural intervention [

29]. The rationale behind the prevalence of the method of testing core samples to determine the compressive strength of masonry is twofold: its popularity and its accuracy. Samples are obtained through the utilization of a drill equipped with a cylindrical core bit, measuring 150 mm in diameter. This method ensures the retrieval of a vertical joint, along with two horizontal joints situated centrally within the cross-section. The element is then loaded longitudinally in the laboratory, while vertical and horizontal displacements are observed. The compressive strength of masonry, as determined by the test, is expressed as the ratio of the load at failure to the horizontal cross-section of the sample (Equation (4)) [

3]:

where

fc—compressive strength of masonry [MPa];

Fcoll—load at failure [N];

—specimen diameter [mm];

l—specimen length [mm].

To perform a mycological assessment of a building, it is first necessary to identify all sources of moisture [

31]. It is well-documented that some regions of a building are particularly susceptible to fungal growth. Such regions include underground floors, where frequent humidity promotes the growth of fungi. Other areas where fungal growth is common, and places where dirt accumulates. In addition to these areas, roofs and gutters are also susceptible to fungal growth, with the tightness of these structures having a particular impact on the humidity inside the building. Finally, places exposed to water accumulation and leaks, such as kitchens and bathrooms, are also prime candidates for fungal growth [

32]. The primary issue of dampness in historic buildings pertains to wall areas, attributable to deficiencies in insulation to impede capillary action, and to the neglect of gutters and roofs. The compressive strength of bricks and mortar is significantly reduced due to excessive moisture, which has a detrimental effect on the service life of buildings and causes the paint coatings, which are so valuable in historic buildings, to peel off [

33]. The determination of the moisture content of a wall can be achieved through the implementation of either a drying-weight method or a non-destructive method. The drying-weight or gravimetric test involves extracting a sample from the wall using a core drill or a regular drill. The sample is then transferred to the laboratory in an airtight container, where its weight is measured. Following a drying process at 105 °C, the sample’s weight is re-measured. Utilizing this information, the mass moisture content is then calculated using a formula (Equation (5)) [

34]:

where

Um, Wm—mass moisture content [%];

mw—mass of the wet (moist) sample [g];

ms—mass of the dry sample [g].

As illustrated in

Table 2, the range of wall moisture content is presented.

On the other hand, the non-destructive method of testing wall moisture involves using a moisture meter, where pin probes are inserted into the wall to read the moisture measurement from the display. The degree of moisture of the tested element is determined by a colour scale [

33]. It should be noted that testing with an electrical meter is less accurate than the drying-weighing method due to the potential for high salt concentrations, which can result in inaccurate readings. The second significant problem with walls is the settling of salts due to long-term capillary action. To determine the salt concentration in the wall, tests are conducted using suitable chemical agents that detect the presence of sulphates, chlorides, and nitrates in the samples. The degree of harm caused by the salt concentration in the wall is interpreted using the guidelines developed by the WTA in Germany, as presented in

Table 3.

This manuscript aims to demonstrate how errors made during the selection of sites for mycological surveys can lead to increased costs associated with the modernization of historic buildings. A catalogue of diagnostic errors and their economic consequences has been compiled, based on an analysis of three real cases. The article presents the argument that the creation of uniform diagnostic guidelines is imperative, emphasizing that the accurate and responsible performance of mycological and construction expertise is not only a technical obligation but also an economic and cultural one. The research hypothesis is as follows: Errors made during the selection of sites for mycological and technical research have been shown to increase the costs and duration of modernizing historic buildings.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Case Selection

The present study is founded upon a secondary analysis of documentation in the form of completed mycological and structural expert reports prepared for three historic public buildings in Poland. It is noteworthy that all the buildings analyzed were entered in the register of monuments in 2008, and that expert reports were prepared at the stage of tender preparations, prior to the commencement of modernization works.

A case study approach was adopted, with the available technical reports serving as the primary source of data. The expert reports included the following: the identification of structural elements, including foundations, load-bearing walls, ceilings, stairs, roof trusses, and chimneys, is imperative for a comprehensive assessment of the building’s condition. This assessment must encompass the evaluation of damage and degradation, such as biological corrosion, dampness, cracks, and plaster detachment. Furthermore, calculations of the thermal resistance of building partitions are essential for determining the effectiveness of any remedial measures. The mycological testing program encompassed the evaluation of selected locations within the buildings. The assessment comprised visual inspection, determination of salt concentration, core strength testing, thermal resistance testing, load-bearing capacity testing, and moisture calculations.

2.2. Diagnostic Analysis and Cost Evaluation Method

The diagnostic analysis was conducted using a structured three-stage procedure, which included extracting information from the technical reports, comparing corresponding structural elements across the three buildings, and identifying discrepancies between pre-tender diagnostics and additional tests performed during construction. The cost evaluation method was based on estimating the financial impact of omitted diagnostic procedures by comparing preliminary design-stage assumptions with actual construction-stage interventions.

A thorough analysis of the technical reports was conducted to determine the completeness of the diagnostics performed prior to the commencement of the works. The analysis of the available technical reports involved a three-stage process. Firstly, a full content analysis was performed on all expert reports, extracting information on the scope of research, the location of discoveries, measurement results, and conservation recommendations. This process involved manually extracting and organising the data into tabular summaries. Secondly, as the analysed buildings were constructed during the same period (1899–1900) and have similar structural features, such as ceramic brick foundations and walls and wooden or Klein-type ceilings, as well as a comparable level of material degradation, it was possible to directly compare analogous elements in each of the three buildings. As the structure of the documents was similar and the scope of information comparable, no formal data coding was used. Thirdly, the results of the tests conducted during the pre-tender documentation stage were compared with those of the additional tests performed during construction. This made it possible to clearly identify which structural elements had been omitted in the initial diagnosis; their subsequent discovery generated additional modernisation costs.

This analysis also encompassed the investigation of the impact of any deficiencies identified on the course and costs of the modernization. The present study focuses particularly on the relationship between the quality of pre-investment tests and the need to perform additional construction work resulting from unforeseen structural defects.

The methodology adopted facilitated a qualitative and quantitative assessment of the impact of underestimation. To determine the cost of underestimating the research at the design stage in relation to the implementation stage, preliminary estimates were made for elements not included in the original design documentation. Cost estimates were then made using a simplified method based on these preliminary estimates. Next, the potential cost of uncovered items at the design stage was estimated. The prices used for the calculations are market prices published by publishers. The methodology employed enabled a qualitative and quantitative assessment of the impact of underestimating the technical condition of historic buildings on the costs and course of their subsequent modernization.

Moreover, this study acknowledges several limitations that are crucial for maintaining methodological transparency. Firstly, the analysis is based on three case studies situated within a single country. Although the buildings exemplify typical late 19th- and early 20th-century masonry structures commonly found throughout Central and Eastern Europe, the findings cannot be considered statistically generalizable. Instead, they provide insightful illustrations of recurring diagnostic challenges encountered in the renovation of historic buildings. Secondly, case selection followed a purposive sampling strategy, constrained by the availability of complete pre-renovation mycological and technical reports. While this approach is appropriate for exploratory research, it may introduce selection bias, as buildings lacking complete documentation were necessarily excluded from the analysis. Thirdly, this study relies on diagnostic information derived from existing expert assessments. These reports varied in the scope of sampling, test locations, and methodologies employed during the design phase. As a result, the depth of diagnostic data was inconsistent across the three buildings, which affects the comparability of certain parameters. Lastly, the original expert assessments frequently involved limited sampling, resulting in many structural elements being evaluated solely through visual inspection. This limitation hampers the analytical precision of the re-evaluation and underscores a broader challenge in heritage conservation practice: inadequate diagnostic coverage during the early stages of projects. Despite these limitations, the consistent patterns identified across the three cases bolster the analytical relevance of the findings and offer valuable guidance for enhancing diagnostics in similar historic masonry buildings.

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of Buildings and Research

The cubic capacity of the buildings studied ranges from approximately 4800 m3 to over 15,000 m3, and the usable floor space from 732 m2 to 2433.8 m2. All buildings have traditional foundations and foundation walls made of solid ceramic bricks laid with lime mortar. The above-ground structures are also made of ceramic bricks, while the ceilings are wooden beams or Klein-type steel–ceramic. The roofs are truss–clamp structures covered with heat-weldable roofing felt. The window and door frames are entirely wooden and show significant wear and tear.

The analysis took into account both the results of tests conducted during construction works. The results are presented in

Table 4 and

Table 5.

As illustrated in

Table 4, two of the structural elements enumerated in the table, namely cornices and lintels, were not subject to assessment during the design stage. However, these elements were analyzed during the construction stage, owing to their alarming visual condition, as reported by the contractor. The evaluation of building elements during the design stage is influenced by both the chosen inspection site and the type of inspection conducted. This process is subjective and varies based on the individual performing the technical assessment. Consequently, it is not typical for cornices and lintels to be assessed incorrectly while other structural elements of the building are evaluated properly. Consequently, solely these two elements, for which an assessment of their condition was imperative during the construction/renovation stage, were selected for further analysis. During the construction stage, a program of inspection of the window lintels was undertaken. Inspection of the external walls in the vicinity of the elements on the room side revealed numerous cracks. A thorough investigation revealed that the brick window lintels exhibited signs of abrasion, while the mortar between the bricks demonstrated deficiencies in cohesion. Additionally, the solid brick surfaces exhibited signs of fracture, and there were multiple instances of detachment of structural elements (

Figure 1 and

Figure 2). Consequently, diagnostic tests were conducted on the brick walls of extant historic buildings in a specialized laboratory. A total of ten samples were extracted from the designated core drilling locations within the brick walls, employing a 150 mm diameter core drill. It was not possible to obtain full cores at any of the points, as the bricks crumbled due to the condition of the lime-sand mortar joints. The determination of the compressive strength of the mortar was achieved through the implementation of the research method developed by Orłowicz and Tkacz [

35] was utilized.

From the larger cores, mortar discs with a diameter of approximately 50 mm were extracted. The discs were then adhered together using quick-setting mortar to create a test sample [

7]. The samples of brick and mortar were subjected to compression in a strength-testing machine.

The results of re-testing the walls of building No. 1 were as follows: the compressive strength of the bricks in the above-ground walls ranges from 10.9 to 35.5 MPa, while that of the mortar ranges from 0.2 to 2.6 MPa; the compressive strength of the wall ranges from 1.5 to 4.7 MPa. Taking into account a coefficient of 0.8, the characteristic compressive strength of the walls ranges from 1.2 to 3.8 MPa. Therefore, it is concluded that the external walls have very low strength parameters due to the low strength of the lime mortar. The above-mentioned defects led to the decision to construct new lintels using the monolithic reinforced concrete method.

Another structural element that was not properly assessed during the preparatory works was the cornices. During the building’s modernization, after exposing the crown of the walls and removing the flashings, it was discovered that the brick cornice molding around the entire perimeter of the façade was detached from the wall structure. Due to the very poor condition of the delaminating mortar on which the cornice was built and the lack of proper brick bonding, the element lost its support along its entire length in the areas where the bricks were bonded to the wall (

Figure 2), resulting in the spontaneous detachment of fragments of the cornice in some places. And therefore, permission was sought from the conservator of monuments to demolish and reconstruct the cornice.

In consideration of the aforementioned findings, following the analysis, it was determined that the lintels and cornices require reconstruction and repair. A bill of quantities was made for these two elements, and the cost estimation of the modernization was calculated.

A comparative analysis of the three buildings indicates that, despite similarities in materials and construction techniques, their technical conditions differed notably. Building No. 1 exhibited the lowest masonry compressive strength values (1.2–3.8 MPa), primarily due to advanced mortar degradation and persistent wall dampness. Building No. 2 presented slightly higher strength levels (1.5–4.1 MPa), consistent with lower moisture content detected in plinth walls. Building No. 3 showed the least deterioration (1.7–4.5 MPa), attributable to better-performing roof drainage and more effective ventilation, preventing long-term saturation. Although moisture and salt contamination were present in all buildings, the severity and distribution differed, influencing both structural performance and the scope of required conservation measures.

3.2. Costs of Modernization Work

The bill of quantities and costs was calculated for a single edifice. As illustrated in

Table 5, the financial implications of lintel construction during Stage II of the investment process, specifically the execution of works, are outlined.

The total cost of the investment, as presented in

Table 6, amounted to EUR 101,380.40, inclusive of preparatory, dismantling, construction, and finishing works. The most significant proportion of the expenses was incurred, which constitutes approximately 45.5% of the total expenditure. The elevated cost of this item is attributable to the substantial scope of work and the necessity to utilize precise technology to ensure the safety of the structure. The second most significant cost item was the formwork and concreting of lintel beams, which cost an estimated EUR 41,107.68, or approximately 40.5% of the total investment value. The findings indicate that the most significant financial burden is associated with construction and restoration projects, which necessitate substantial material and technological inputs.

A percentage analysis of the costs presented in

Table 6 shows that diamond saw cutting accounted for 45.6% of total expenditures, followed by formwork and concreting (40.5%), and reinforcement preparation (1.5%). Demolition (2.5%) and debris management (0.9%) represented marginal portions of the total. Grouping the costs into categories indicates that reinforcement and new lintel construction represented 86.0% of the investment, demolition-related work 3.4%, and waste disposal 1.0%. The remaining elements were of lesser financial significance, although their combined share was also noteworthy. The reinforcement of existing lintels and formwork structures totaled EUR 4798.80, and the construction of recesses in the walls amounted to EUR 3304.77. The estimated demolition costs of the brick structure were determined to be EUR 2508.44, whereas the installation of thermal insulation was estimated at EUR 1015.46. The total cost of transporting and disposing of rubble was less than EUR 1000, while the preparation and installation of reinforcement amounted to EUR 1541.91. Despite constituting only 14% of the overall expenditure, the presence of these items is indicative of the intricacy of the technological process and the multitude of activities associated with the primary construction works.

Table 6 presents a detailed breakdown of costs related to the demolition and reconstruction of cornices during the construction works.

In the reconstruction of the cornice (as shown in

Table 7), the costs for formwork installation and concreting accounted for 69.3% of the total expenses. Additionally, chemical anchors contributed 8.8% and deep drilling accounted for 5.4%. Although they represented smaller expenses, demolition works (5.8%), debris transport and disposal (1.4%), and auxiliary dismantling tasks (1.2%) were still necessary. When categorized, the costs can be summarized as follows: reconstruction and reinforcement at 83.5%, demolition at 7.2%, and waste management at 1.4%. In consideration of the findings presented in

Table 6, it can be inferred that the aggregate value of the works totaled EUR 202,566.68, inclusive of dismantling, transportation, and restoration services. The majority of the costs were accounted for by works related to formwork installation, concreting, and expansion joints, with a total cost of EUR 140,230.53, representing approximately 69.3% of the total expenditure. This is the prevailing item, arising from the substantial material and technological expenditure of the reconstruction stage.

The second most significant cost component was the drilling of holes with a diameter of 10 mm and a depth of 25 cm, which amounted to EUR 11,124.00 (approximately 5.4% of the total). The installation of chemical anchors was the third most significant cost component, with a total expenditure of EUR 17,847.84 (approximately 8.8%). This finding suggests that preparatory work and securing structural elements also constitute a significant part of the investment budget.

The demolition of the brick structure, using lime and cement-lime mortar, incurred costs amounting to EUR 11,661.78, which is equivalent to approximately. The total costs were found to be 5.8% of the total. It is important to note that the cost of transporting rubble (EUR 2253.16) and fees for its disposal (EUR 646.83) are included in this item. These costs amount to EUR 2899.99, which is approximately 1.4% of the total value.

The auxiliary activities, such as dismantling the formwork (EUR 845.30) and the supporting structure frame (EUR 1658.43), accounted for the smallest share of the costs, totaling approximately 1.2% of the investment value.

In summary, the results obtained clearly indicate that the tests carried out solely at the design stage were insufficient for a comprehensive diagnosis of the technical condition. It was only through the excavations and laboratory analyses conducted during the construction works that the true extent of the damage was revealed, thus enabling a decision to be made regarding the demolition or replacement of specific components. The modernization of components not included in the design and cost documentation resulted in a substantial increase in the project’s costs, amounting to EUR 305,421.35 in net costs. These costs were not foreseen at the tender and cost estimate stage, either by the investor or the tenderer.

To facilitate a comparison of the costs to be borne by the investor at the design documentation stage and during construction, the cost of excavations for lintels and gas pipes was calculated. This amounted to EUR 1474.27 net (

Table 8).

4. Discussion

4.1. Impact of Diagnostic Scope on Renovation Costs

The absence of comprehensive diagnostic tests before initiating the investment resulted in substantial additional expenses, including lintel replacement and cornice restoration. Modernization costs significantly exceeded excavation expenses. For a single facility, the investor incurred additional costs totaling EUR 305,421.35, which represents a significant underestimation in both the initial offer and the investor’s cost estimate. Similar observations have been made by Nowogońska (2020) [

7], who demonstrated that neglecting early renovation actions and diagnostics in heritage buildings leads to progressive degradation and a substantial increase in repair costs over time.

Analysis of the data in

Table 6 indicates that the primary cost driver in lintel installation is the requirement for high-precision operations and specialized equipment. Elevated costs result from both complex technological processes and potential diagnostic errors during the assessment of wall conditions. Incorrect selection of sites for mycological testing may expand the project scope, necessitate additional formwork, reinforcement, or replacement of structural elements, and thereby substantially increase the total investment cost. This finding aligns with the insights of Ksit (2022, 2023) [

36,

37], who noted that moisture and biodeterioration are often overlooked in initial assessments. This oversight can lead to unnecessary secondary structural interventions, which could have been prevented with thorough and targeted testing from the outset.

In contrast, analysis of

Table 7 shows that more than 80 percent of costs are attributed to errors in the preparation and securing of the structure, which necessitate the repetition of complex concrete and reinforcement tasks. Witzany et al. (2016) [

8] examined comparable distributions of cost burdens and emphasized that inaccuracies in assessing the compressive strength and moisture content of historic brick masonry result in unnecessary structural reinforcements and reconstructions.

A comparison of the results in

Table 6 and

Table 7 reveals that the highest costs in both cases are associated with the reconstruction or reinforcement of structural elements, rather than demolition activities. This finding underscores the importance of high-quality diagnostics during the preparatory phase for ensuring economic efficiency throughout the modernization process. An accurate assessment of a building’s technical condition can substantially reduce the risk of additional costs arising from correcting design and construction errors. Proietti et al. (2021) [

9] similarly concluded that moisture-related damage in ancient masonry structures can be reduced through early, multidisciplinary diagnostics that combine chemical, mechanical, and thermographic analyses.

Furthermore, recent work by Carpino et al. (2023) [

6] highlights the importance of representative sampling sites for mycological surveys in accurately identifying biological corrosion “hot spots.” Fungal contamination can lead to unnecessary conservation efforts and increased repair costs if it is not properly understood or identified.

Economically speaking, the results are consistent with findings from international preservation reports, such as PlaceEconomics (2013) [

38], which show that less than 2% of restoration budgets are allocated toward preventive diagnostics. They can, however, drastically cut the total cost of upcoming restoration projects by 30 to 50 percent. Furthermore, the National Park Service (Technical Preservation Services, 2016) [

39] emphasizes that one of the best conservation tactics is to detect moisture and salt damage in masonry early on.

Comparable findings have been reported internationally. Historic England has documented that moisture-related diagnostic omissions are a leading cause of unexpected budget escalation in conservation projects in the UK, particularly when concealed masonry elements are not tested systematically [

40]. An additional international perspective is provided by Puncello and Caprili [

41], who reviewed seismic and structural assessment methods for historic masonry at different scale levels—from material tests to component analysis and global structural evaluation. Their findings emphasise that insufficient diagnostic coverage at the early stages leads to systematic underestimation of deterioration mechanisms and, consequently, to significantly higher rehabilitation costs. This aligns closely with the results of the present study, confirming that multi-scale diagnostics are essential to avoid cost escalation in heritage building modernisation [

41]. A broader climatic perspective is provided by recent European research. Vandemeulebroucke et al. [

42] conducted more than 34,000 hygrothermal simulations across Europe and the Mediterranean, demonstrating that moisture-driven degradation risks vary significantly between regions and are particularly severe in northern climates such as Bodø, Norway, where freeze–thaw cycles and wood decay are projected to increase by 68–81% of cases. The study also showed that simplified or incomplete diagnostic approaches can misrepresent degradation risks by up to 100%, underscoring the need for detailed, parameter-based assessments in historic masonry. These findings strongly align with the results of the present study, reinforcing that insufficient diagnostic coverage leads to systematic underestimation of damage progression in heritage buildings [

42].

From a risk management perspective, inadequate diagnostic coverage represents a significant challenge in the conservation of historic masonry buildings. The likelihood of diagnostic omissions is especially pronounced in heritage structures due to factors such as accessibility constraints, concealed structural components, and often incomplete archival documentation. The financial repercussions of these omissions can be substantial, as undetected deterioration may compromise load-bearing masonry, necessitating extensive reconstruction rather than preventive maintenance. In this context, the financial risk associated with diagnostic gaps can be articulated as follows:

Risk = Probability of Diagnostic Omission × Financial Impact of Corrective Action, where both elements are typically high for historic masonry buildings. Therefore, systematic diagnostics—particularly those relating to moisture content, salt accumulation, and mortar-brick cohesion—are essential for effective risk mitigation. Moreover, the implications of insufficient diagnostics extend beyond financial concerns; they also carry significant sustainability consequences. Unnecessary reconstruction of structural elements leads to increased consumption of raw materials, higher volumes of construction waste, and higher carbon emissions associated with cement production, steel reinforcement, and transportation. By ensuring thorough early diagnostics, we can avoid redundant structural replacements, thereby advancing key sustainability objectives such as resource efficiency, waste minimization, and CO2 reduction within the construction process. In this broader context, comprehensive diagnostics are not only a technical and economic imperative but also a foundational aspect of sustainable heritage management.

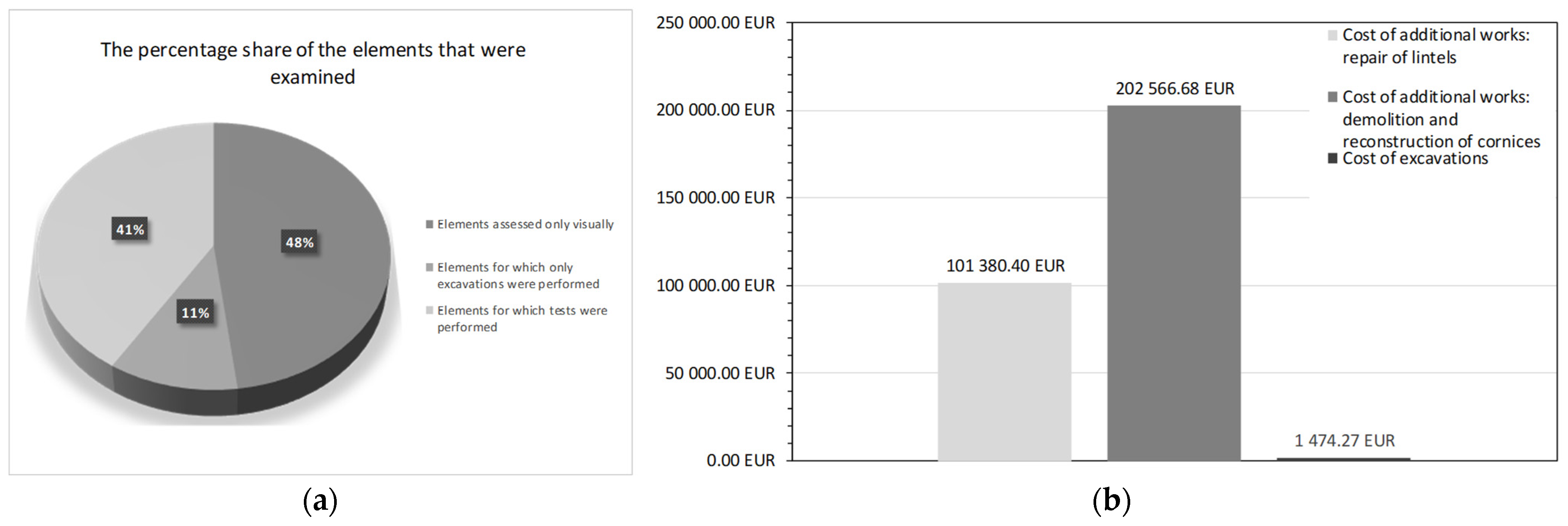

Figure 3 shows the comparison of the breadth of diagnostic tests conducted and their subsequent costs.

The pie chart on the left indicates that 48% of the examined structural elements were assessed solely through visual inspection, 11% were subjected to surface-level testing only, and 41% received a full diagnostic investigation. This means that more than half of all elements were not evaluated using comprehensive diagnostic procedures. In this context, “insufficiently assessed” refers to cases where either no diagnostic tests were performed (missing data) or the tests conducted did not meet the recommended scope defined in WTA and EN 350:2016. Such omissions significantly increase the likelihood of overlooking hidden structural defects. The bar chart on the right depicts the correlation between the breadth of testing and the costs of construction work. The expense for excavations was only EUR 1474.27, while additional works, including the repair of lintels and the reconstruction of cornices, amounted to EUR 101,380.40 and EUR 202,566.68, respectively. The results are consistent with existing research in preventive conservation and underscore the importance of early diagnostics in the physical safeguarding of heritage materials. Besides that, such diagnostics make conservation projects more financially attractive [

37,

43]. Hence, it is appropriate to consider exhaustive preliminary diagnostics not only as a mere technical imperative but also as a profitable investment—economically and culturally—into the ecological conservation of our architectural heritage.

The findings of this study demonstrate a clear causal relationship between diagnostic incompleteness and increased renovation costs. The process begins with the long-term accumulation of moisture in masonry, which gradually weakens the lime-based mortar and reduces the load-bearing capacity of the brickwork. When this degradation remains undetected—due to insufficient sampling or limited test coverage—the structural condition is overestimated at the design stage. As a result, critical defects are only revealed during construction works, at which point corrective interventions (replacement of lintels, reconstruction of cornices, additional reinforcement) must be implemented under time pressure. This reactive approach substantially increases costs, expands the scope of work, and generates avoidable material consumption. The sequence can be summarised as follows: moisture → weakened mortar → underestimated structural damage → construction-stage discovery → additional reinforcement → increased renovation costs.

4.2. Prioritization of Structural Interventions in Historic Buildings

In practical conservation projects, multiple deteriorated elements are often identified simultaneously, including lintels, cornices, balcony slabs, roof–wall junctions, and staircases. Because renovation budgets and construction timelines are usually constrained, a transparent methodology is needed to determine which elements require immediate reconstruction or reinforcement and which can be scheduled for later intervention. This challenge highlights the importance of linking diagnostic findings with prioritization strategies in historic building maintenance (

Table 9).

To address this need, a conceptual prioritization framework is proposed. The framework is based on several criteria:

Structural safety risk, understood as the combined likelihood and consequence of failure;

Deterioration mechanisms, such as moisture penetration, salt crystallization, and biological corrosion;

Exposure and vulnerability, including weathering intensity and accessibility;

Progression potential, meaning the risk of damage spreading or accelerating if left untreated;

Cost–impact ratio, comparing the cost of early diagnostics with the significantly higher expenses associated with late-stage corrective interventions.

These criteria, together, make it possible to rank structural elements according to their urgency and expected impact.

The results of this study directly inform this prioritization approach. The cost ratio between early diagnostics (€1474) and late interventions (€305,421) demonstrates that certain components should always be examined first. Lintels and cornices were repeatedly identified as critical weak points due to their hidden load paths, long-term exposure to moisture, and high risk of sudden detachment. These elements should therefore be placed in the highest priority tier (Tier 1) for early, exhaustive diagnostics. Components with chronic moisture exposure, such as plinths and foundation walls, are classified as Tier 2. Elements with lower structural consequences, including interior partitions and ceilings, are considered Tier 3.

Overall, integrating diagnostic results with a structured prioritization framework enhances the transparency and effectiveness of renovation planning. Such an approach supports practitioners, designers, and building owners in making informed decisions in situations where multiple deteriorated elements coexist and where financial and temporal constraints must be respected.

5. Conclusions

Analysis of the case studies demonstrates that improper selection of mycological and technical analysis sites increases the overall cost of historic building renovation. Data in

Table 5 and

Table 6 show that repeated or extended construction activities, such as cornice reconstruction and lintel installation, generate significant additional expenses. Accurate and consistent diagnostic procedures would have prevented these unnecessary costs.

The most significant expenses were associated with the reconstruction of structural elements, including concreting, reinforcement, and the application of specialized technologies such as diamond saw cutting. While these interventions are technically justified, they are primarily secondary measures necessitated by previous diagnostic errors that failed to identify the full extent of material degradation. Consequently, rectifying these mistakes frequently incurs costs that exceed those of the initial diagnostic phase several times. The research hypothesis is supported by these findings: inaccurate selection of mycological testing sites and incorrect diagnosis of cornice condition significantly increase reconstruction costs, especially for reinforced concrete and assembly work. The findings presented are crucial for the sustainable development of protecting and using historic buildings. Conducting thorough mycological and technical diagnostics establishes a solid foundation for safe modernization and serves as an environmentally effective measure. If test locations are improperly selected, it can lead to increased costs and necessitate demolition, reconstruction, and material interventions. These processes generate significant amounts of construction waste, raise CO2 emissions, and require the consumption of energy and raw materials. On the other hand, a comprehensive evaluation of the technical condition during the tender preparation stage allows for a reduction in the scope of work, extends the durability of existing elements, and minimizes the need for new materials, such as concrete, steel, and insulation. Thus, improving diagnostic standards aligns with environmental goals, promotes the circular economy, and reduces the ecological footprint of modernizing historic buildings. For future research, focusing on the creation of standardized approaches for selecting diagnostic locations and assessing the correlation between diagnostic accuracy and renovation costs would be worthwhile. The conclusions of this research are particularly useful for architects, engineers, conservators, and heritage managers. This is because dependable diagnostics save excess reconstruction, help safeguard historic buildings in a financially optimal manner, and facilitate the sustainable conservation of historic buildings.