From Technological Flexibility to Sustainable Products: The Mediating Role of Environmental Scanning and Circular Economy Principles

Abstract

1. Introduction

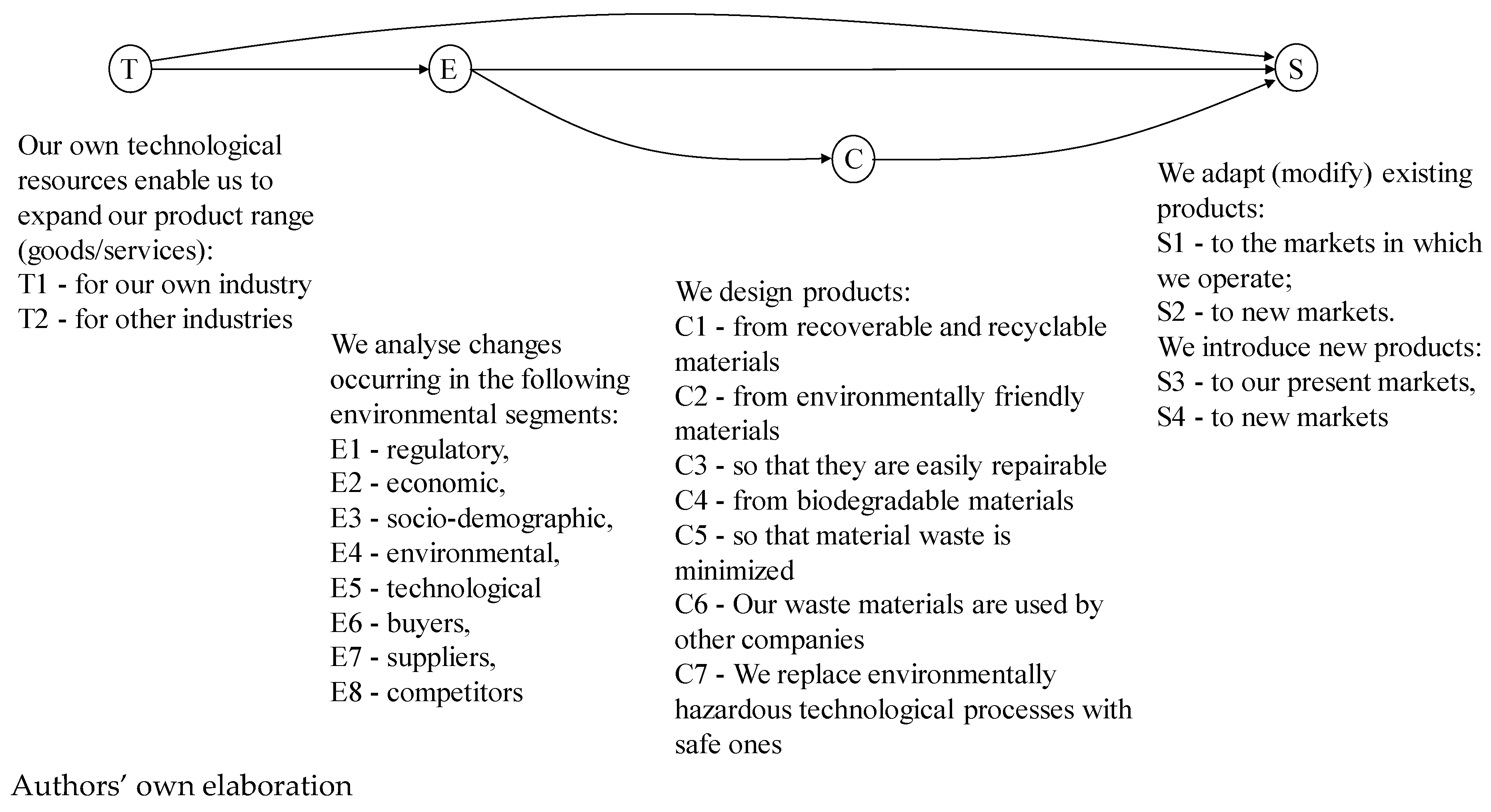

- Many studies treat technological flexibility (T) as an independent factor enabling eco-innovation or circular economy principles (C), assuming a direct positive correlation between T and C [7,8]. Ferasso et al. [9] point out that the moderating role of scanning and analysing changes in the macro environment and industrial environment of a company (E) is often overlooked, and that taking this role into account supports the implementation of measures appropriate for the circular economy principles (C). The T–E–C sequence, therefore, requires clarification.

- According to classical strategic management theory, scanning changes in the environment (E) for the purposes of shaping product and market strategies (S) is dominated by an economic perspective, focused on seeking competitive advantage, increasing market share and maximising profits [10,11,12]. This is confirmed by more recent studies [13,14,15] and expands on this point of view by indicating that it also supports risk reduction and increases organisational resilience [16,17]. In turn, in the literature on sustainable development and the circular economy, environmental scanning is analysed from a completely different perspective. Its purpose is to identify regulatory requirements, social pressure, pro-environmental innovations and opportunities to reduce the environmental footprint [18]. These two perspectives lead to tension between commercial logic (T–E–S path) and ecological logic (T–E–C–S path) [19]. This phenomenon, identified as “dual business–sustainability tension” [20], requires further study.

- Most contemporary models and studies treat the principles of the circular economy (C) as an executive element of product and market decisions [21,22]. However, there are also works, e.g., [23,24,25], which consider the opposite relationship, suggesting that circular design principles can become the starting point for a new product and market strategy. However, the paradigm that circularity is the outcome, not the origin, of strategic choice still prevails.

- In this article, we aim to at least partially narrow this cognitive gap. To this end, we conduct an empirically based analysis of two cause-and-effect chains:

- Technological flexibility—Environmental scanning—Product-market strategies (T–E–S),

- Technological flexibility—Environmental scanning—circular economy principles—Product-market strategies (T–E–C–S).

2. Literature Review

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Research Design

3.2. Instruments and Data Analysis

- Background information (about the firm and the respondent).

- Does the technological flexibility (T) of your resources enable you to expand the range of products/services you offer? Possible answers: 1—do not enable at all; 2—enable to a very small extent; 3—enable to a moderate extent; 4—enable to a large extent; 5—enable to a very large extent. Cronbach’s alpha = 0.42. This is too low a value and, therefore, each of the two questions, T1 and T2, is treated as a different construct: T1—adaptability of technology within own industry; T2—transformability of technology in different sectors.

- We scan and analyse changes taking place in segments of the environment (E). Possible answers: 1—we do not undertake such actions at all; 2—we undertake such actions to a very small extent; 3—we undertake such actions to a moderate extent; 4—we undertake such actions to a large extent; 5—we undertake such actions to a very large extent. Cronbach’s alpha = 0.82 indicates a very high reliability of the measurement scale.

- We design products in accordance with the principles of the circular economy (C). Possible answers—the same as for scanning changes in the environment. Cronbach’s alpha = 0.78 indicates a very high reliability of the measurement scale.

- We adapt existing products and introduce new ones to the market (S). Possible answers—the same as for scanning changes in the environment. Cronbach’s alpha = 0.83 indicates very high reliability of the measurement scale.

4. Results

- Single-step increase—which means that the median increases once and only by one level, most often from 3.0 to 4.0 when the T rank reaches a value of 4 or 5;

- Saturation curve—when the median increases slowly for ranks 1 to 3 and stabilises at 4.0 for ranks 4 and 5;

- Stepwise increase—when the median increases with the increase in the T rank, but there are cases where the median is the same for two consecutive ranks (e.g., for ranks 2 and 3 it is 3.0) and then increases again to 4.0 or 5.0, as is the case with E6—scanning the buyers segment.

- Modifications to existing products offered by the company in existing markets (variable S1) consist of minimising material waste (grouping variable C5);

- New products that are introduced to existing markets (S3) and new markets (S4) are designed to be more easily repairable (grouping variable C3).

5. Discussion

- Economic segment (E2)—information on costs, inflation, purchasing power;

- Technology segment (E5)—technologies that increase efficiency or shorten time to market;

- Supplier segment (E7)—availability of materials, reliability of supplies;

- Competitor segment (E8)—competitors’ activities, new players, technological advantages.

- Economic segment (E2)—changes in the costs of primary and secondary raw materials, predicted prices of materials with low environmental impact and the economic effects of designing products with a longer life cycle;

- Socio-demographic segment (E3)—user expectations regarding durability and environmental responsibility [13];

- Environmental segment (E4)—environmental pressures, critical materials, ecological risks [15];

6. Conclusions

- A clear operationalisation of the dual scanning logic and empirical evidence showing which segments of the environment drive the business-oriented T–E–S pathway and which activate the ecological T–E–C–S pathway.

- Identification of only two circular economy principles—C3 (design for repairability) and C5 (waste minimisation)—that meaningfully translate into sustainable product–market strategies. This demonstrates that the transition from T to sustainable products is selective rather than comprehensive.

- Empirical clarification of the conditions under which firms can integrate business and ecological objectives, challenging the dominant assumption that these logics are inherently incompatible.

- Introduction of the concept of engagement thresholds in environmental scanning, explaining why technological flexibility leads to sustainability gains only when scanning intensity reaches specific levels.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Klemke-Pitek, M.; Majchrzak, M. Pro-Ecological Activities and Shaping the Competitive Advantage of Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises in the Aspect of Sustainable Energy Management. Energies 2022, 15, 2192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Communication from the Commission: The European Green Deal, COM(2019) 640 Final; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2019.

- United Nations. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2015.

- UNFCCC. Paris Agreement; United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change: Bonn, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Hose, K.; Amaral, A.; Peças, P. Manufacturing Flexibility through Industry 4.0 Technological Concepts—Impact and Assessment. Glob. J. Flex. Syst. Manag. 2023, 24, 271–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega-Gras, J.J.; Bueno-Delgado, M.V.; Puche-Forte, J.F.; Garrido-Lova, J.; Martínez-Fernández, R. Exploring Industry 4.0 Technologies Implementation to Enhance Circularity in Spanish Manufacturing Enterprises. Sustainability 2025, 17, 7648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kannan, D.; Gholipour, P.; Bai, C. Smart Manufacturing as a Strategic Tool to Mitigate Sustainable Manufacturing Challenges: A Case Approach. Ann. Oper. Res. 2023, 331, 543–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alraja, M.N.; Imran, R.; Khashab, B.M.; Shah, M. Technological Innovation, Sustainable Green Practices and SMEs Sustainable Performance in Times of Crisis (COVID-19 pandemic). Inf. Syst. Front. 2022, 24, 1081–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferasso, M.; Beliaeva, T.; Kraus, S.; Clauss, T.; Ribeiro-Soriano, D. Circular economy business models: The state of research and avenues ahead. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2020, 29, 3006–3024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansoff, H.I. Strategies for Diversification. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1957, 35, 113–124. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, M. Towards a Dynamic Theory of Strategy. Strateg. Manag. J. 1991, 12, 95–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, G.; Scholes, K.; Whittington, R. Exploring Corporate Strategy: Text & Cases, 8th ed.; Pearson Education: Harlow, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Knudsen, M.P.; von Zedtwitz, M.; Griffin, A.; Barczak, G. Best Practices in New Product Development and Innovation: Results from PDMA’s 2021 Global Survey. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2023, 40, 257–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirciftci, T.; Belarmino, A. A Cross-Cultural Study of Competitive Intelligence in Revenue Management. J. Revenue Pricing Manag. 2022, 21, 691–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masi, D.; Kumar, V.; Garza-Reyes, J.A.; Godsell, J. Towards a More Circular Economy: Exploring the Awareness, Practices, and Barriers from a Focal Firm Perspective. Prod. Plan. Control 2018, 29, 539–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maluleka, M.; Chummun, B.Z. A Review of Existing Literature on Competitive Intelligence and Insurance Markets. Corp. Gov. Organ. Behav. Rev. 2023, 7, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- YahiaMarzouk, Y.; Jin, J. The Relationship Between Environmental Scanning and Organizational Resilience: Roles of Process Innovation and Environmental Uncertainty. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10, 966474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siekmann, F.; Schlör, H.; Venghaus, S. Linking Sustainability and the Fourth Industrial Revolution: A Monitoring Framework Accounting for Technological Development. Energy Sustain. Soc. 2023, 13, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do Vale, G.; Collin-Lachaud, I.; Lecocq, X. Resolving Paradoxical Tensions during Business Model Innovation for Sustainability in Retailing: The Role of the Ecosystem. J. Retail. 2025; in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Bommel, K. Managing Tensions in Sustainable Business Models: Exploring Instrumental and Integrative Strategies. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 196, 829–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pieroni, M.P.; McAloone, T.; Pigosso, D.A.C. Business Model Innovation for Circular Economy and Sustainability: A Review of Approaches. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 215, 198–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parida, V.; Frishammar, J. Circular Business Models: Where Does Swedish Industry Stand? Swedish Entrepreneurship Forum: Örebro, Sweden, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Jagnow, J.; Stoehr, B.; Bernijazov, R.; Koldewey, C.; Dumitrescu, R. Circular Product Design: A Literature-Based Identification of Challenges from the Perspective of Product Designers. In Proceedings of the Design Society (ICED25), Dallas, TX, USA, 11–14 August 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Aguiar, M.F.; Mesa, J.A.; Jugend, D.; Pinheiro, M.A.P.; Fiorini, P. Circular Product Design: Strategies, Challenges and Relationships with New Product Development. Manag. Environ. Qual. Int. J. 2022, 33, 300–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jugend, D.; Santos, H.H.; Garrido, S.; Mesa, J.A. Circular Product Design Challenges: An Exploratory Study on Critical Barriers. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2024, 33, 4825–4842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trzcielinska, J.; Kaps, R. Impact of Business Environment Perception on Pro-Ecological Activities in Polish Firms. Eur. Res. Stud. J. 2024, 27, 510–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todescato, M.; Braholli, O.; Chaltsev, D.; Di Blasio, I.; Don, D.; Egger, G.; Emig, J.; Pasetti Monizza, G.; Sacco, P.; Siegele, D.; et al. Sustainable Manufacturing through Application of Reconfigurable and Intelligent Systems in Production Processes: A System Perspective. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 22374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Liu, X.; Li, Y. Exploring Dynamic Capability Drivers of Green Innovation at Different Digital Transformation Stages: Evidence from Listed Companies in China. Sustainability 2024, 16, 5666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Yang, B.; Zhu, L. Digital Technology Usage, Strategic Flexibility, and Business Model Innovation. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2023, 194, 122726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajesh, R. Flexible Business Strategies to Enhance Resilience in Supply Chains. J. Manuf. Syst. 2021, 60, 903–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khettabi, I.; Benyoucef, L.; Boutiche, M.A. Sustainable Reconfigurable Manufacturing System Design Using Adapted Multi-Objective Evolutionary-Based Approaches. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2021, 115, 3741–3759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milisavljevic-Syed, J.; Li, J.; Xia, H. Realisation of Responsive and Sustainable Reconfigurable Manufacturing Systems. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2024, 62, 2725–2746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, R.; Napoleone, A.; Andersen, A.L.; Brunoe, T.D.; Nielsen, K. A Systematic Methodology for Changeable and Reconfigurable Manufacturing Systems. J. Manuf. Syst. 2024, 74, 449–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batwara, A.; Sharma, V.; Makkar, M.; Giallanza, A. An Empirical Investigation of Green Product Design and Development Strategies for Eco Industries Using Kano Model and Fuzzy AHP. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahoo, S.; Kumar, A.; Mangla, S.K.; Tiwari, A. Industry 4.0 Adoption and Eco-Product Innovation Capability: Understanding the Role of Supply Chain Integration. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2024, 33, 8798–8814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, G.; Zhang, J.; Wang, S. How Digitalization and Sustainability Promote Digital Green Innovation for Industry 5.0 through Capability Reconfiguration: Strategically Oriented Insights. Systems 2024, 12, 341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Shi, X. Impact of Digital Transformation on Green Production: Evidence from China. Heliyon 2024, 10, e35526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, M.S.; Ma, S.; Wang, Y.; Tian, Q. Impact of Technology-Enabled Product Eco-Innovation: Empirical Evidence from the Chinese Manufacturing Industry. Technovation 2023, 128, 102853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosca, O.; Manunza, A.; Manca, S.; Vivanet, G.; Fornara, F. Digital Technologies for Behavioral Change in Sustainability Domains: A Systematic Mapping Review. Front. Psychol. 2024, 14, 1234349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-García, E.; Martínez-Falco, J.; Marco-Lajara, B.; Manresa-Marhuenda, E. Revolutionizing the Circular Economy through New Technologies: A New Era of Sustainable Progress. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2024, 33, 103509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trzcielinski, S.; Kruszynski, M.; Trzcielinska, J. Shaping the Enterprise’s Strategy; Publishing House of Poznan University of Technology: Poznań, Poland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Vacchi, M.; Siligardi, C.; Cedillo-González, E.I.; Ferrari, A.M.; Settembre-Blundo, D. Industry 4.0 and Smart Data as Enablers of the Circular Economy in Manufacturing: Product Re-Engineering with Circular Eco-Design. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akkad, M.Z.; Šebo, J.; Bányai, T. Investigation of the Industry 4.0 Technologies Adoption Effect on Circular Economy. Sustainability 2022, 14, 12815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sony, M.; Antony, J.; McDermott, O. How Do the Technological Capability and Strategic Flexibility of an Organization Impact Its Successful Implementation of Industry 4.0? A Qualitative Viewpoint. Benchmarking Int. J. 2022, 30, 924–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulze, A.; Townsend, J.D.; Talay, M.B. Completing the Market Orientation Matrix: The Impact of Responsive and Proactive Competitor Orientation on Innovation and Firm Performance. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2022, 103, 198–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ERM International Group. 2023 Sustainability Trends Report; ERM: London, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Song, Y.; Ali, A.; Wang, G.; Wang, W. Environmental Scanning, Cross-Functional Coordination, and the Adoption of Green Strategies: An Information Processing Perspective. Creat. Innov. Manag. 2024, 33, 39–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindgreen, E.R.; Opferkuch, K.; Walker, A.M.; Salomone, R.; Reyes, T.; Raggi, A.; Simboli, A.; Vermeulen, W.; Caeiro, S. Exploring Assessment Practices of Companies Actively Engaged with Circular Economy. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2022, 31, 1414–1438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Vecchio, P.; Mele, G.; Ndou, V.; Secundo, G. Open Innovation and Social Big Data for Sustainability: Evidence from the Tourism Industry. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahn, T.; Pinkse, J. A Paradox Approach to Sustainable Product–Service Systems. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2022, 105, 182–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alosi, A.; Annunziata, E.; Rizzi, F.; Frey, M. Conceptualising Active Management of Paradoxical Tensions in Corporate Sustainability: A Systematic Literature Review. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2023, 32, 3529–3549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, B.N.; Tang, Y.; Chen, E.W.; Li, S.; Luo, D. Corporate Sustainability Paradox Management: A Systematic Review and Future Agenda. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 579272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kotler, P.; Keller, K.L. Marketing Management, 15th ed.; Pearson Education: Harlow, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

| Variable | S1 | S2 | S3 | S4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| T1 | 0.31 | 0.34 | 0.31 | 0.30 |

| T2 | 0.17 | 0.27 | 0.17 | 0.18 |

| Variable | E1 | E2 | E3 | E4 | E5 | E6 | E7 | E8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T1 | 0.26 | 0.21 | 0.3120 | 0.26 | 0.29 | 0.30 | 0.35 | 0.29 |

| T2 | 0.18 | 0.16 | 0.29 | 0.18 | 0.18 | 0.09 | 0.22 | 0.15 |

| Grouping Variable | Dependent Variable | Significantly Different Groups | Median Trend by Groups | Rank Giving the Largest Median | Largest Median |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T1 | E2 | 1–4; 1–5 | Single-step increase | 4; 5 | 4.0 |

| E4 | 1–3; 1–4; 1–5; 2–4; 2–5 | Saturation curve | 4; 5 | 4.0 | |

| E5 | 1–4; 1–5; 2–4; 2–5 | Single-step increase | 3; 4; 5 | 4.0 | |

| E6 | 1–3; 1–4; 1–5; 2–5; 3–5 | Stepwise increase | 5 | 5.0 | |

| E7 | 1–3; 1–4; 1–5; 2–4; 2–5; 3–5 | Saturation curve | 3; 4; 5 | 4.0 | |

| E8 | 1–4; 1–5; 2–4; 2–5 | Stepwise increase | 4; 5 | 4.0 | |

| T2 | E3 | 1–4; 1–5; 3–4 | Stepwise increase | 5 | 4.0 |

| E7 | 2–5; 3–5 | Single-step increase | 3; 4; 5 | 4.0 |

| Grouping Variable | Dependent Variable | Significantly Different Groups | Median Trend by Groups | Rank Giving the Largest Median | Largest Median |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E1 | C1 | 2–5 | Single-step increase | 4; 5 | 4.0 |

| C2 | 2–5 | Single-step increase | 4; 5 | 4.0 | |

| C3 | 2–5; 3–5 | Single-step increase | 4; 5 | 4.0 | |

| C4 | 3–5 | Single-step increase | 5 | 4.0 | |

| C7 | 2–5 | Single-step increase | 5 | 3.0 | |

| E2 | C1 | 3–4 | Single-step increase | 4; 5 | 4.0 |

| C2 | 3–4; 3–5 | Single-step increase | 4; 5 | 4.0 | |

| C5 | 2–5; 3–5 | Single-step increase | 4; 5 | 4.0 | |

| E3 | C1 | 1–5; 2–5; 3–5 | Stepwise | 5 | 5.0 |

| C3 | 1–5; 2–5; 3–5 | Flat-then-rising | 5 | 5.0 | |

| C4 | 1–4; 1–5; 2–5; 3–4; 3–5 | Stepwise | 5 | 5.0 | |

| C5 | 2–5; 3–5 | Single-step increase | 4; 5 | 4.0 | |

| C7 | 1–4; 1–5 | Stepwise | 5 | 4.0 | |

| E4 | C2 | 1–4; 1–5; 3–5 | Single-step increase | 4; 5 | 4.0 |

| C3 | 3–5 | Single-step increase | 4; 5 | 4.0 | |

| C4 | 1–5; 2–5; 3–5; 4–5 | Stepwise increase | 5 | 4.0 | |

| C6 | 1–5; 3–5; 4–5 | Single-step increase | 5 | 4.0 | |

| C7 | 1–5 | Stepwise increase | 4; 5 | 3.0 | |

| E5 | C3 | 2–5; 3–5 | Single-step increase | 4; 5 | 4.0 |

| Grouping Variable | Dependent Variable | Significantly Different Groups | Median Trend by Groups | Rank Giving the Largest Median | Largest Median |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E1 | S1 | 1–3; 1–4; 1–5; 2–4; 2–5; 3–4; 3–5 | Single-step increase | 4; 5 | 4.0 |

| S2 | 1–4; 1–5; 2–4; 2–5; 3–4; 3–5 | Single-step increase | 4; 5 | 4.0 | |

| S3 | 1–4; 1–5; 2–4; 2–5 | Single-step increase | 4; 5 | 4.0 | |

| S4 | 1–3; 1–4; 1–5; 2–4; 2–5; 3–5 | Stepwise increase | 4; 5 | 4.0 | |

| E2 | S1 | 1–4; 1–5; 2–4; 2–5; 3–4; 3–5 | Single-step increase | 4; 5 | 4.0 |

| S2 | 1–4; 1–5; 2–4; 2–5; 3–5 | Single-step increase | 4; 5 | 4.0 | |

| S3 | 2–4; 2–5; 3–4; 3–5 | Single-step increase | 4; 5 | 4.0 | |

| S4 | 1–4; 1–5; 2–4; 2–5; 3–4; 3–5 | Stepwise increase | 4; 5 | 4.0 | |

| E3 | S1 | 1–4 | Single-step increase | 3; 4; 5 | 4.0 |

| S2 | 1–3; 1–4; 1–5; 2–4; 2–5 | Single-step increase | 3; 4;5 | 4.0 | |

| S4 | 1–4; 1–5; 2–4; 2–5; 3–4 | Single-step increase | 4; 5 | 4.0 | |

| E4 | S1 | 1–3; 1–4; 1–5; 2–5; 3–5 | Single-step increase | 4; 5 | 4.0 |

| S2 | 1–2; 1–3; 1–4; 1–5; 3–5 | Single-step increase | 4; 5 | 4.0 | |

| S3 | 1–4; 1–5; 2–5; 3–5 | Single-step increase | 4; 5 | 4.0 | |

| S4 | 1–4; 1–5; 3–5 | Stepwise increase | 5 | 4.0 | |

| E5 | S1 | 1–5; 2–4; 2–5; 3–4; 3–5; 4–5 | Single-step increase | 4; 5 | 4.0 |

| S2 | 1–4; 1–5; 2–4; 2–5;3–4; 3–5 | Single-step increase | 4;5 | 4.0 | |

| S3 | 1–4; 1–5; 2–4; 2–5; 3–5; 4–5 | Single-step increase | 4; 5 | 4.0 | |

| S4 | 1–4; 1–5; 2–4; 2–5; 3–5 | Stepwise increase | 5 | 4.0 | |

| E6 | S1 | 1–4; 1–5; 2–4; 2–5; 3–4; 3–5; 4–5 | Stepwise increase | 4; 5 | 4.0 |

| S2 | 1–4; 1–5; 2–4; 2–5; 3–4; 3–5; 4–5 | Stepwise increase | 4; 5 | 4.0 | |

| S3 | 1–3; 1–4; 1–5; 3–5 | Stepwise increase | 4; 5 | 4.0 | |

| S4 | 1–4; 1–5; 2–5; 3–5 | Stepwise increase | 5 | 4.0 | |

| E7 | S1 | 1–4; 1–5; 2–4; 2–5; 3–4; 3–5 | Single-step increase | 4; 5 | 4.0 |

| S2 | 1–4; 1–5; 2–4; 2–5; 3–4; 3–5 | Stepwise increase | 4; 5 | 4.0 | |

| S3 | 1–4; 1–5; 2–5; 3–4; 3–5; 4–5 | Single-step increase | 4; 5 | 4.0 | |

| S4 | 1–4; 1–5; 2–4; 2–5; 3–4; 3–5 | Stepwise increase | 4; 5 | 4.0 | |

| E8 | S1 | 1–4; 1–5; 2–4; 2–5; 3–5 | Single-step increase | 4; 5 | 4.0 |

| S2 | 1–3; 1–4;1–5; 2–5; 3–5 | Stepwise increase | 4; 5 | 4.0 | |

| S3 | 1–4; 1–5; 2–4; 2–5; 3–5 | Stepwise increase | 4; 5 | 4.0 | |

| S4 | 1–4; 1–5; 2–5; 3–4; 3–5 | Stepwise increase | 4; 5 | 4.0 |

| Grouping Variable | Dependent Variable | Significantly Different Groups | Median Trend by Groups | Rank Giving the Largest Median | Largest Median |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C3 | S3 | 3–5 | Single-step increase | 4; 5 | 4.0 |

| S4 | 3–4; 3–5 | Single-step increase | 4; 5 | 4.0 | |

| C5 | S1 | 3–4 | Single-step increase | 4; 5 | 4.0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Trzcielińska, J.K.; Trzcieliński, S. From Technological Flexibility to Sustainable Products: The Mediating Role of Environmental Scanning and Circular Economy Principles. Sustainability 2026, 18, 183. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010183

Trzcielińska JK, Trzcieliński S. From Technological Flexibility to Sustainable Products: The Mediating Role of Environmental Scanning and Circular Economy Principles. Sustainability. 2026; 18(1):183. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010183

Chicago/Turabian StyleTrzcielińska, Jowita Krystyna, and Stefan Trzcieliński. 2026. "From Technological Flexibility to Sustainable Products: The Mediating Role of Environmental Scanning and Circular Economy Principles" Sustainability 18, no. 1: 183. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010183

APA StyleTrzcielińska, J. K., & Trzcieliński, S. (2026). From Technological Flexibility to Sustainable Products: The Mediating Role of Environmental Scanning and Circular Economy Principles. Sustainability, 18(1), 183. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010183