1. Introduction

International organizations, particularly the United Nations World Tourism Organization (UNWTO), promote sustainable tourism practices worldwide, providing guidance and support for national initiatives. To assess environmental sustainability, several frameworks are widely used, including the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI), the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), the United Nations Global Compact (UNGC), and environmental management standards such as ISO 14001 [

1]. This focus is increasingly important given that tourism is responsible for roughly 8% of global CO

2 emissions [

2], which has led much of the academic literature to concentrate on green tourism [

2,

3,

4,

5].

In this context sustainability has become a defining measure of organizational legitimacy, the hospitality industry stands at the crossroads of expectation and accountability. Hotel chains are increasingly judged not only by their operational performance—such as carbon reduction, waste management, or local sourcing—but also by the stories they tell about their commitment to sustainability [

6]. These narratives circulate through glossy corporate reports, formal corporate sustainability reports and strategic ESG disclosures, which now function as key instruments for shaping organizational identity and legitimacy [

7].

As sustainability becomes a communicative as much as an operational endeavor, the question is no longer whether hotels act sustainably, but how convincingly and coherently they communicate those actions. The expansion of sustainability discourse across industries has created new tensions between symbolic and substantive practices, between organizational talk and organizational action [

8,

9,

10,

11].

In tourism, where reputation and trust are foundational to value creation, these tensions become visible through the contrast between high-level sustainability claims and the operational realities they purport to describe. Understanding these tensions is essential for assessing how hotel corporations construct legitimacy, authenticity, and responsibility through their own discourse.

In the global hospitality sector, sustainability has evolved from a peripheral concern to a central pillar of corporate strategy and public reputation management [

12,

13]. As tourism destinations face intensifying environmental and social pressures, hotel chains are increasingly expected not only to adopt sustainable practices but also to communicate them credibly and transparently to diverse stakeholders. This growing emphasis on sustainability communication reflects both the sector’s response to climate and social challenges and the expanding expectations of travelers, investors, and communities for ethical and authentic corporate conduct.

Scholarly research on corporate sustainability communication has expanded considerably, establishing communication as both a strategic and legitimizing instrument in corporate sustainability performance [

14,

15]. Within hospitality, prior studies have shown that hotel corporations strategically frame sustainability to reinforce brand legitimacy and consumer trust [

6,

16]. However, research has also revealed persistent imbalances between symbolic and substantive communication practices—where sustainability narratives serve more as instruments of image management than of genuine transformation [

17,

18].

At the same time, work on organizational discourse shows that sustainability communication often privileges themes of efficiency, innovation, and risk mitigation, while underrepresenting social justice, equity, and participatory dimensions [

19,

20,

21]. These tendencies suggest that sustainability in hospitality is constructed discursively within corporate arenas, but the internal coherence of these narratives, particularly the balance between symbolic and substantive elements, remains insufficiently explored.

Previous studies indicate that corporate sustainability reports and declarations often adopt a symbolic character, relying on narratives of eco-efficient growth and security to preserve social legitimacy rather than communicate tangible change [

21,

22]. In crisis contexts, sustainability communication becomes a tool for managing stakeholder expectations, where authenticity and transparency are strategically negotiated through linguistic and rhetorical adaptation [

23].

Similarly, analyses of digital CSR communication show that organizations frequently pursue symbolic legitimacy through online channels, prioritizing reputation-building and stakeholder reassurance while marginalizing social and ethical dimensions of sustainability [

16,

24].

Consequently, the internal coherence of corporate sustainability claims, specifically how symbolic and substantive elements interact within organizational discourse, represents a critical research gap. To date, few studies have systematically examined how organizational authenticity and legitimacy are constructed and negotiated through corporate sustainability discourse itself.

This study investigates the internal coherence, convergence, and differentiation within institutional sustainability communication among international hotel chains. It applies qualitative content analysis to a comprehensive dataset consisting of corporate sustainability declarations and ESG reports published on official websites.

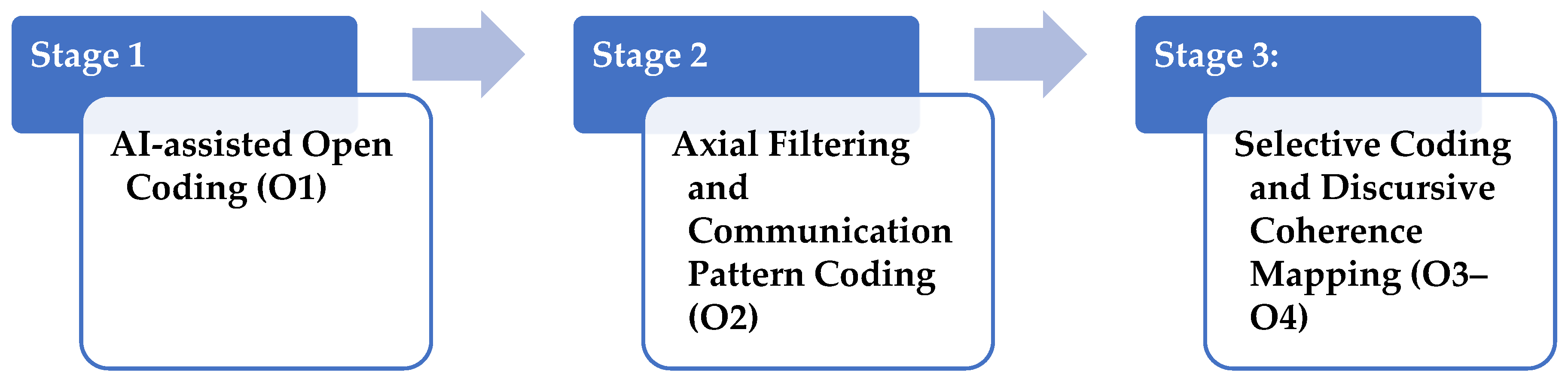

The research pursues four main objectives:

Objective 1 (O1)—To identify the dominant sustainability themes and values expressed in hotels’ corporate declarations.

Objective 2 (O2)—To examine how these themes reflect symbolic and substantive sustainability communication practices.

Objective 3 (O3)—To evaluate the extent to which hotel groups construct sustainability communication that is internally coherent and discursively aligned.

Objective 4 (O4)—To identify emerging patterns and strategies of sustainability communication within the hospitality sector.

By analyzing corporate sustainability discourse, this study proposes a replicable framework for assessing discursive coherence and legitimacy construction in sustainable tourism communication. It contributes to the growing literature on responsible communication, stakeholder legitimacy, and authentic sustainability practices, illustrating how sustainability narratives evolve at the intersection of institutional strategy and organizational identity construction.

The article is organized as follows:

Section 2 presents an extensive review of the relevant literature on sustainability communication and legitimacy formation in the hospitality sector.

Section 3 outlines the qualitative research design, sampling strategy, and analytical framework, detailing the use of content analysis and the four-layer discursive coherence model.

Section 4 reports the empirical findings, including dominant sustainability themes, symbolic versus substantive communication patterns, and coherence assessments across hotel groups.

Section 5 offers a comprehensive discussion of the results, highlighting theoretical and managerial implications. The article concludes by summarizing key contributions, acknowledging limitations, and outlining directions for future research.

4. Results

4.1. Dominant Sustainability Themes Across Corporate Reports

The thematic analysis conducted in ATLAS.ti version 25 revealed a set of recurrent sustainability themes shared across the ten global hotel groups. These themes align closely with the environmental-social-governance (ESG) architecture of corporate sustainability reporting and reflect the core priorities emphasized by hospitality organizations in their public declarations. Across the dataset, ESG Commitments emerged as the most pervasive theme (78 grounded quotations). The hotel groups repeatedly foregrounded the centrality of their ESG frameworks as strategic pillars guiding global operations. For instance, Choice Hotels underscores its “(ESG) commitments across its global network of over 7500 hotels,” while Hyatt articulates a values-driven orientation rooted in its long-standing purpose: “Hyatt’s commitment to caring for the planet, people, and responsible business.” These statements demonstrate an overarching discursive tendency to position ESG as both a normative anchor and a reputational asset.

Environmental concerns were prominently represented across several subthemes, including Energy Efficiency (25 quotations), Environmental Stewardship (23), Water Conservation (21), Responsible Sourcing (18), Renewable Energy (16), and Waste Reduction (15). Energy Efficiency appears as a ubiquitous operational priority across chains, illustrated by references to technological upgrades and performance gains. BWH highlights continuous improvement targets (“Improve energy efficiency”), while Choice notes the “Full migration of IT infrastructure to Amazon Web Services, reducing energy use,” and G6 reports a “16% reduction in electricity use.” These excerpts reflect a consistent emphasis on energy optimization as an emblematic environmental performance indicator.

The theme of Environmental Stewardship underscores a broader ecological orientation. BWH explicitly “recognizes its global footprint and commits to operating responsibly,” whereas Hyatt expands the theme through “biodiversity and destination stewardship,” suggesting an integrative approach that connects operations with place-based environmental obligations.

Water Conservation also emerges as a cross-chain priority, with Marriott repeatedly reporting a “9.3% reduction in water intensity since 2016, supported by low-flow fixtures, smart irrigation, and online conservation resources.” The fact that Marriott’s phrasing recurs identically across documents suggests standardized global reporting structures typical for multinational hotel corporations.

Responsible Sourcing reinforces the environmental-social interface: Hilton reports “responsible sourcing of key commodities” and highlights participation in global governance fora such as COP29 and the World Economic Forum, while Hyatt cites progress in “responsibly sourcing coffee, tea, seafood, animal proteins, and amenities.” This theme reveals a shared sectoral movement toward supply chain due diligence and ethical procurement.

Renewable Energy is also a growing priority, reflected in Wyndham’s “63% renewable electricity at corporate HQ” and Marriott’s rapid expansion of EV charging infrastructure (“7100+ EV chargers across 1800+ properties”). These examples signal an increasing integration of renewable energy into corporate decarbonization pathways.

Finally, Waste Reduction is present in all chains, with strategies ranging from refillable dispensers and reduced plastics to advanced food waste technologies. Choice reports “AI-powered food waste monitoring pilots,” while G6 notes, “No single-use plastics in guest rooms or food service,” marking a shift toward systematic resource circularity.

On the governance front, themes such as Accountability (24 quotations) and Transparency (17) are central. Aimbridge emphasizes “accountability and proactive problem solving,” positioning service excellence as tied to responsible leadership. G6 echoes this direction with “a strengthened focus on accountability, ESG leadership, and community impact.” These patterns reflect the sector’s movement toward more explicit governance claims aligned with stakeholder expectations for verifiable, ethical operations.

Transparency further reinforces this governance orientation, with Choice referring to “public policy transparency” and Hilton highlighting “transparent reporting, global standards compliance, and ethical oversight,” framing sustainability as inseparable from credible governance and compliance structures.

The key social subtheme identified is Diversity (16 quotations). Statements stress inclusion, belonging, and multicultural awareness (“Increase cultural awareness,” “Celebrate diversity,” “Ensure every individual feels valued”). BWH highlights “Promoting diverse viewpoints and collaboration,” reinforcing the increasingly central role of DEI initiatives in shaping organizational culture and guest experience narratives.

4.2. Symbolic vs. Substantive Communication Patterns

Across all ten hotel groups, a total of 171 substantive references and 79 symbolic references were identified. This distribution indicates a ratio of approximately 68% substantive to 32% symbolic communication, suggesting that large hospitality corporations increasingly foreground quantifiable ESG achievements in response to rising demands for transparency. At company level, substantive disclosures were consistently higher (

Table 2).

The cross-company comparison reveals two distinct patterns in how hotel groups mobilize symbolic and substantive sustainability discourse. Economy and midscale brands such as Choice, G6, and Wyndham display the highest frequency of substantive disclosures, a tendency driven primarily by their emphasis on operational ESG performance—particularly energy efficiency, water management, and waste reduction. These groups appear to anchor their sustainability communication in tangible, trackable outcomes, reflecting a pragmatic orientation toward regulatory compliance, cost efficiency, and performance benchmarking.

In contrast, luxury and upper-upscale hotel groups, including Hilton, IHG, and Hyatt, exhibit a more finely balanced combination of symbolic and substantive communication. While they report extensive quantitative indicators, similar to their midscale counterparts, they also embed these disclosures within broader narratives emphasizing organizational values, cultural identity, purpose-driven leadership, and inclusive workplace ideals. This dual strategy suggests a more complex discursive architecture in which measurable ESG achievements are complemented by aspirational claims designed to reinforce brand authenticity and emotional resonance with stakeholders.

Substantive communication across the dataset is characterized by quantifiable achievements, performance indicators, third-party audits, and technology-enabled improvements. These disclosures typically refer to measurable reductions in emissions and resource use, renewable energy deployment, responsible sourcing metrics, or verified operational efficiencies. Representative examples include:

“Full migration of IT infrastructure to Amazon Web Services, reducing energy use.” (Choice).

“Electricity use ↓16%, natural gas ↓24%, water usage ↓11% since 2019.” (G6).

“Hilton exceeded its 2030 goal: 60.6% reduction in landfilled waste since 2008.”

“Progress toward 2030 science-based targets to reduce Scope 1 & 2 emissions by 27.5% and Scope 3 by 53% per sq. meter.” (Hyatt).

“7100+ EV chargers across 1800+ properties; rooftop solar feasibility analysis complete.” (Marriott).

Such disclosures constitute evidence-based reporting, reinforcing perceptions of credibility and operational maturity. They are closely aligned with global frameworks -including Science Based Targets initiative (SBTi), Global Reporting Initiative (GRI), and Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD)—and collectively signal a sector-wide transition toward performance-oriented legitimacy, where concrete achievements take precedence over purely narrative-driven sustainability claims.

In parallel, the analysis identifies a second category of sustainability discourse rooted in symbolic communication, comprising values-oriented statements, emotional storytelling, purpose declarations, and aspirational commitments that lack quantifiable evidence. These statements reinforce organizational ethos and stakeholder relationships but do not document verifiable progress. Examples include:

“Pride in caring for guests; accountability… exceeding expectations at every moment.” (Aimbridge).

“Aimbridge seeks to make a meaningful connection.”

“A workplace rooted in belonging, respect, inclusion, and collaboration.” (Aimbridge).

“Donating through Best Western for a Better World®…” (BWH).

“Opportunities: sustainability-driven consumer preference.” (Choice).

“Sonesta places people at the core of its identity—guests, employees, franchisees.”

4.3. Discursive Coherence Within Corporate Communication

To assess the degree of internal discursive coherence (O3), the analysis examined how sustainability commitments, performance indicators, narrative strategies, and operational practices align within each hotel group’s corporate communication. Using the four-layer coherence model derived from legitimacy theory, organizational discourse, and symbolic-substantive CSR research, the results reveal a structurally consistent communication pattern across the ten companies, though with variations by segment and corporate maturity (

Table 3).

Performance coherence is particularly strong in Hilton, Hyatt, IHG, Marriott, and Wyndham. Across the corpus, hotels provide quantifiable achievements that directly substantiate their commitments. Choice, for example, links its energy-efficiency narrative to verified impacts: “35 hotels received third-party sustainability audits, where smart thermostats generated over $33,000 in annual savings and reduced nearly 70 tons of CO2e.” G6 demonstrates a similar alignment, reporting that “electricity use decreased 16%, natural gas 24%, and water usage 11% since 2019”, thereby grounding its sustainability identity in operational efficiency.

Hilton illustrates exemplary coherence by integrating performance into long-term goals, noting that “the company exceeded its 2030 goal with a 60.6% reduction in landfilled waste since 2008.” Hyatt reinforces this relationship with technology-enhanced monitoring, explaining that “KITRO measurement systems deployed in nearly 100 hotels identified 25–35% food-waste reduction potential.” Marriott similarly demonstrates alignment between commitments and outcomes through renewable-energy deployment, reporting “7100+ EV chargers across 1800 properties following a global solar feasibility analysis.”

Narrative coherence is the most prominent coherence dimension across all groups (222 coded instances). Its strength reflects the centrality of brand identity in hospitality and the sector’s long-standing discursive reliance on cultural and service-oriented narratives. Collectively, the patterns confirm that narrative coherence is the most universally applied legitimacy strategy in the sector.

Aimbridge, for instance, consistently constructs its identity around themes of “belonging, shared success, and opportunity,” reinforcing a people-centered cultural narrative across its documents. G6 maintains a coherent storyline through recognition and inclusion, highlighting awards such as “Leaders in Diversity” and its designation as a “Top Veteran-Friendly Company.”

Hilton’s narrative coherence is particularly developed: its CEO repeatedly emphasizes the founding belief that hospitality should “fill the earth with the light and warmth of human connection,” a message reflected across its global workforce and sustainability strategy. Hyatt sustains consistency through its integrated people-planet identity, combining “biodiversity and destination stewardship” with a “strong learning and development culture.” Meanwhile, IHG reinforces a narrative of environmental guardianship through statements such as: “nature protection is integrated into corporate strategy through biodiversity assessments and nature-positive hotel development.”

Marriott anchors its narrative coherence in its enduring corporate values—”Put People First, Pursue Excellence, Embrace Change, Act with Integrity, Serve Our World”—which recur throughout its ESG reporting and provide a stable interpretive frame across all sustainability claims.

Strategic coherence refers to the alignment between sustainability communication and long-term goals, governance systems, reporting frameworks, and external standards [

47,

50]. With 183 coded instances, this dimension is especially strong among Hilton, Hyatt, IHG, and Marriott—groups with historically institutionalized CSR infrastructures.

Choice demonstrates robust strategic alignment by establishing “board committees overseeing ESG integration and alignment with SASB, TCFD, and ISSB standards.” Wyndham reinforces its long-term sustainability narrative through corporate responsibility targets: “2025 goals focused on environmental impact, ethical operations, and people-centered initiatives.” Sonesta structures its ESG strategy through a defined social pillar emphasizing “guest wellbeing, DEI, safety, and community impact.”

Marriott further positions itself as an industry leader by asserting a commitment to “long-term positive impact across the global value chain,” while Hilton’s strategic coherence emerges through cross-cutting governance structures that connect ethics, human rights, climate strategy, and operational standards.

Operational coherence captures the extent to which sustainability commitments translate into concrete practices, routines, and standards within hotels. With 96 coded instances, it is particularly evident in Wyndham, Hilton, Hyatt, IHG, and BWH. The examples demonstrate that operational coherence works as the connective tissue linking narrative and strategy to observable actions, thereby strengthening the overall authenticity of sustainability communication.

Wyndham showcases strong operational alignment through “Wish Day initiatives, local volunteering, and giving programs,” illustrating how community narratives are enacted on the ground. Sonesta provides clear examples of circularity in action through “vendor partnerships for recycling, textile recycling, composting programs, and reusable amenities.”

Marriott demonstrates supply-chain operationalization through industry collaboration in HARP, where “suppliers are screened via EcoVadis and required to meet environmental and social criteria.” IHG operationalizes decarbonization by introducing an “industry-first Low Carbon Pioneers program,” recognizing hotels powered entirely by renewable energy. Hilton integrates sustainability into day-to-day operations, citing that “69% of hotels now include hydration stations, and Digital Key prevented over 103 tons of plastic waste in 2024.” BWH operationalizes waste reduction using “compostable utensils, paper straws, bagasse containers, and recycled-content packaging.”

4.4. Sector-Level Discursive Strategies and Emerging Patterns

Analysis of the sustainability-theme quotations across the ten hotel groups reveals a highly structured, though uneven, sectoral discourse, dominated by a set of recurring thematic clusters. Environmental themes dominate the sector’s discourse, with Food Waste emerging as the single most substantiated category (n = 6).

The word cloud illustrates the dominant lexical patterns associated with the

Food Waste theme across the sustainability reports (

Figure 2). The most salient terms—

food,

waste,

reduction, and

hotels—highlight a sector-wide emphasis on quantifiable reduction efforts and operational interventions. Frequent references to

systems,

tracking,

digital, and

measurement (e.g., Winnow, an AI-powered food-waste tracking system, and KITRO, an automated food-waste measurement and analytics platform) indicate a strong technological framing of food-waste management, while terms such as

donate,

divert,

redistribution, and

organizations reflect multistakeholder partnerships aimed at preventing landfill disposal. The presence of

renewable,

energy,

compost, and

micro-greeneries suggest an integrative narrative linking food-waste mitigation to broader circularity and environmental strategies. Overall, the lexical distribution reinforces the finding that food-waste discourse is positioned as both an operational efficiency measure and a socially responsible practice, consistent with sector-level discursive patterns identified in the analysis.

Considering the hotel groups, Hilton foregrounds large-scale digital interventions, reporting that “Winnow AI systems in 200 hotels save 3.9 million meals annually” while “Green Ramadan expanded to 32 hotels”. Hyatt reinforces the technologically enabled approach through its statement that “KITRO measurement technology in nearly 100 hotels identifies 25–35% food waste reduction potential” and reports a “77% reduction in wasted bread at Hyatt Regency Düsseldorf via digital tracking”. IHG adopts a system-level model through a ‘prevent, donate, divert’ strategy accompanied by partnerships with food redistribution organizations, whereas Sonesta demonstrates localized operational outcomes with a case where one property “diverted 58 tons of food waste and repurchased compost to support micro-greeneries used in hotel kitchens”.

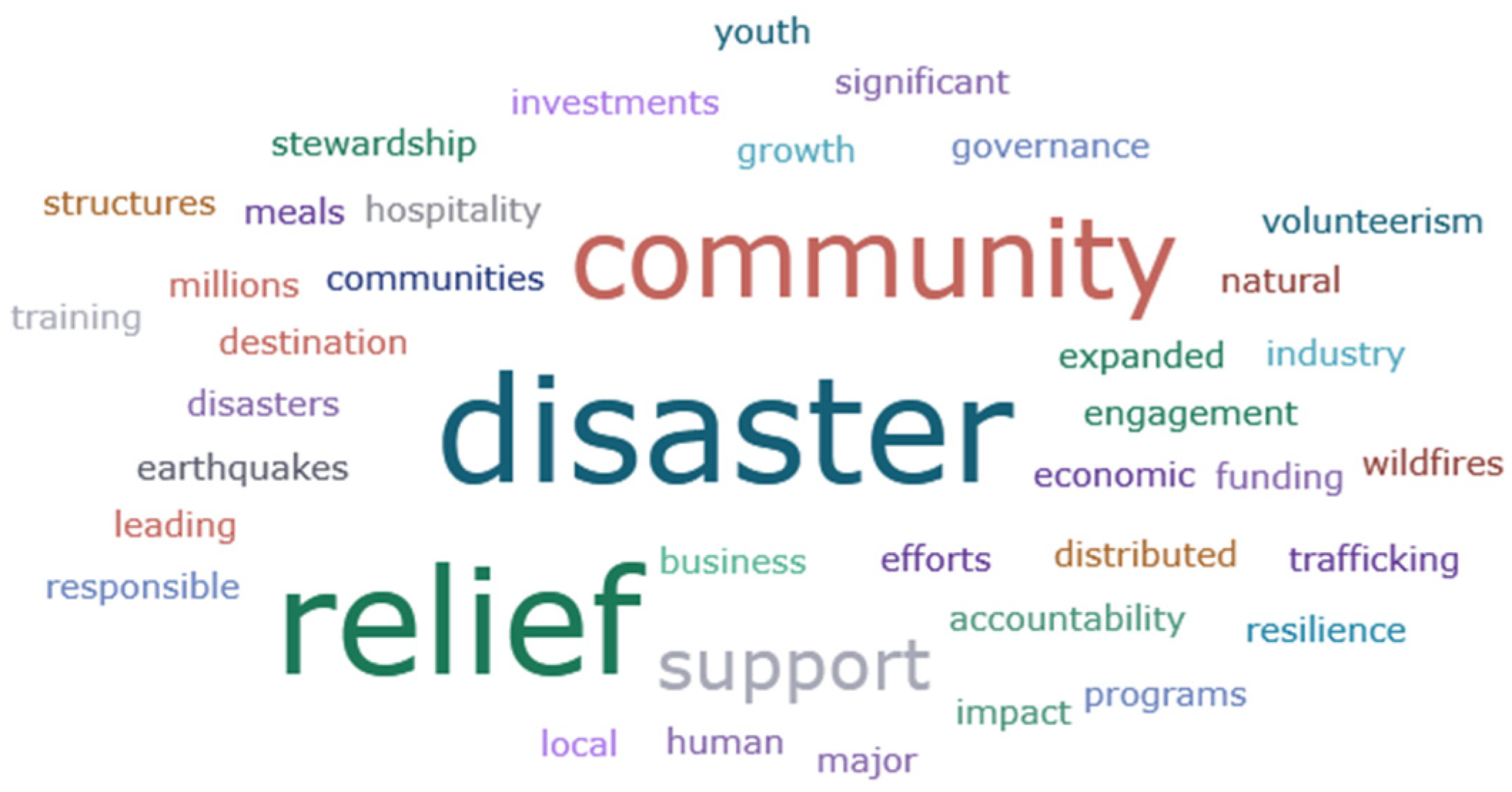

“Disaster Relief” emerges as the second strongest discursive cluster (n = 5), revealing a shared commitment to community resilience across major hotel groups.

The word cloud for the Disaster Relief (

Figure 3) theme highlights a strongly humanitarian and community-focused discourse across hotel sustainability reports. The largest terms, “disaster,” “relief,” “community,” and “support”, indicate that hotel groups consistently position themselves as active contributors to crisis response and community resilience. Supporting terms such as “earthquakes,” “wildfires,” “meals,” “volunteerism,” “funding,” and “resilience” reflect concrete forms of intervention, including large-scale meal distribution, emergency funding, youth-focused recovery programs, and partnerships for humanitarian assistance. Overall, this visualization shows that disaster relief is framed not only as philanthropic engagement but also as part of broader responsible business commitments, reinforcing the sector’s emphasis on social impact, local support structures, and governance-linked accountability.

Hilton repeatedly highlights large-scale social outreach, stating that its community impact includes “millions of meals distributed and major support for natural disasters” through the Hilton Global Foundation, complemented by “disaster relief and community resilience programs”. Hyatt similarly reports “significant disaster relief funding for the Turkey/Syria earthquakes, Typhoon Mawar, and the Maui wildfires”. Marriott integrates disaster relief within a broader human-rights framework, positioning its actions as part of “deep community engagement and transparent governance”. Across these cases, sector discourse integrates emotional framing, humanitarian values, and operational detail -reinforcing disaster relief as a core element of hospitality’s moral positioning.

Themes coded under Responsible Business (n = 5) reveal a highly aligned governance rhetoric across Hilton, Hyatt, and IHG.

The word cloud illustrates how hotel corporations frame “responsible business” as a multidimensional construct centered on business, responsible, and people (

Figure 4). The prominence of terms such as

strategy,

governance,

ethical,

environmental,

global, and

practices shows that companies consistently anchor responsible business in strategic governance structures, ethical conduct, and global operational consistency. Words like

progress,

impact,

report, and

platform emphasize a discourse of accountability, transparency, and continuous improvement, while terms related to

diversity,

community, and

workforce reveal that responsible business is narrated not only as an environmental or governance concern but also as a people-centered commitment. Overall, the lexical pattern indicates a sector-wide strategy that blends ethical governance, environmental stewardship, and human capital development into a cohesive responsible business narrative.

Hilton structures its entire ESG identity around four pillars—People, Hotels, Communities, and Responsible Business—supported by the LightStay data platform and “strong cross-sector partnerships”. Hyatt’s World of Care framework similarly centers responsible business, describing its commitment to “caring for the planet, people, and responsible business”, while reinforcing this through “strong governance, transparent reporting, and secure and ethical operations”. IHG emphasizes board-level accountability, noting that its responsible business governance is led by the Board of Directors and shaped by materiality assessments focused on “ethical practices, cybersecurity, and procurement”.

Financial Support appears as another major theme (n = 5), especially in Hilton, Hyatt, and Marriott.

The word cloud illustrates how hotel corporations articulate financial support within their sustainability discourse, emphasizing “

owned,” “

businesses,” “

suppliers,” “

community,” “

grants,” “

employment,” and “

survivors” (

Figure 5). These terms highlight a dominant focus on equity-oriented financial mechanisms, such as support for

minority-owned and disabled-owned suppliers,

community grants, and

employment programs for vulnerable groups. The prominence of words like “

distributed,” “

awarded,” “

expanded,” and “

supporting” underscores a narrative centered on resource allocation, empowerment, and inclusion, suggesting that financial support is framed not only as economic assistance but as a strategic driver of diversity, social mobility, and resilience across hotel value chains.

Hilton reports that its Team Member Assistance Fund distributed “$1.4 million in 2024”. Hyatt contributes multiple layers of support, from “funding the NRFT Survivor Fund” to awarding “$1 million in multi-year community grants” and expanding accessibility accommodations. Marriott highlights its role in inclusive economic systems, reporting “over $700 million spent with diverse-owned suppliers”.

Similarly, the Employment theme (n = 3) demonstrates sectoral concern for workforce mobility and youth opportunity.

The word cloud highlights the centrality of employment-focused commitments within hotel sustainability discourse (

Figure 6). Terms such as “employment,” “jobs,” “connected,” “company,” “program,” and “resettlement” dominate, reflecting the sector’s emphasis on workforce integration, youth employment pathways (e.g., RiseHY), refugee resettlement, and equality-driven hiring practices. The presence of words like “LGBTQ,” “infrastructure,” “legislation,” and “engages” indicates that employment themes are often embedded within broader social responsibility narratives related to inclusion, policy engagement, and community support. Overall, the cloud shows that employment commitments are framed less through quantitative performance indicators and more through socially oriented language stressing opportunity creation and inclusive growth.

Hyatt’s RiseHY program “connected 5700+ Opportunity Youth to jobs”, while Marriott ties employment engagement to broader advocacy in climate legislation, EV infrastructure, LGBTQ+ equality, and refugee resettlement. These patterns indicate that financial and employment-related discourse functions as a key mechanism for positioning hospitality companies as social stabilizers within their communities.

Mid-frequency themes such as Sustainable Sourcing, Environmental Management, and Climate Change (n = 3 each) further reinforce a coordinated environmental-social narrative. Hilton frames sustainable sourcing within broader sustainability priorities, while Marriott reports measurable progress such as achieving “24% sustainable seafood (MSC/ASC) and 56% sustainable FF&E products”. Sonesta embeds sourcing within compliance expectations, requiring “environmental management systems, responsible chemical management, and sustainable procurement”. Meanwhile, Wyndham links climate change to a comprehensive environmental strategy including energy efficiency, water conservation, waste diversion, and biodiversity protection.

5. Discussion

The findings of this study reveal a highly structured and strategically curated sustainability discourse across the world’s largest hotel groups, characterized by a marked predominance of substantive communication complemented by selective symbolic elements. This discursive configuration aligns with contemporary scholarship suggesting that corporate sustainability reporting operates as both an evidentiary practice and a mechanism of legitimacy construction [

21,

40]. Across the dataset, hotels overwhelmingly foreground quantifiable ESG achievements—such as emissions-intensity reductions, digital food-waste systems, renewable-energy adoption, third-party audits, and responsible-sourcing metrics—thus reinforcing a sector-wide movement toward performance-oriented legitimacy. At the same time, symbolic communication remains strategically present, particularly among upper-upscale and luxury brands, where values-based narratives, emotional framings, and aspirational commitments play a visible role in shaping corporate identity.

This duality reflects what the literature conceptualizes as a hybrid symbolic—substantive model of sustainability communication [

17,

18]. While symbolic statements rarely mislead, they function as normative anchors that elevate sustainability from a set of operational tasks to a moral horizon guiding organizational purpose. This pattern is consistent with the sector’s emphasis on hospitality as a relational and service—oriented domain, where meaning-making and emotional connection are historically embedded in corporate narratives [

14]. Accordingly, narrative coherence emerges as the most pervasive dimension of discursive alignment, with companies constructing highly consistent identity frames that interweave sustainability with corporate culture, stakeholder care, and long-standing organizational values.

Performance coherence is uneven across the sector. Groups such as Hilton, Hyatt, IHG, Marriott, and Wyndham demonstrate strong alignment between environmental commitments and measurable achievements, often supported by digital monitoring technologies, science-based targets, or third-party verification. These patterns suggest that institutional maturity and operational capacity play a significant role in enabling substantive communication. In contrast, smaller groups or those operating asset-light models exhibit more limited performance alignment, relying more extensively on narrative and strategic coherence to signal responsibility. This differentiation supports the argument that business models shape the balance between symbolic and substantive disclosures, producing structural variations in discursive authenticity [

22].

Sector-level analysis further highlights the emergence of shared thematic clusters that structure sustainability communication across the hospitality industry. The strongest clustering around food waste, disaster relief, responsible business governance, financial support, and employment indicates a convergence toward standardized sustainability priorities, deeply embedded in global ESG expectations. Notably, the lexicon associated with food waste reveals a technologically driven, highly operational discourse emphasizing measurement, monitoring, and reduction systems. Disaster relief, in contrast, reflects a humanitarian register focused on community resilience, volunteerism, and crisis response—an area where symbolic and substantive elements intertwine most visibly. Responsible business governance exhibits a clearly institutionalized tone rooted in ethics, cybersecurity, and board-level oversight, while financial support and employment themes indicate a social-inclusion narrative centered on empowerment, supplier diversity, and opportunity creation.

Overall, the findings demonstrate that the sector’s sustainability discourse operates simultaneously as an accountability mechanism, a strategic identity platform, and a tool for maintaining moral legitimacy. The coexistence of symbolic and substantive elements does not necessarily constitute a legitimacy gap; rather, it reflects a layered communicative architecture where aspiration and evidence co-produce organizational authenticity. This hybrid configuration illustrates the complexity of corporate sustainability communication in contemporary hospitality and underscores the importance of discursive coherence as a criterion for evaluating the credibility and strategic function of ESG reporting.

6. Conclusions

The novelty of this work lies in providing the first comparative, multi-layered discursive analysis of sustainability communication across the world’s largest hotel groups revealing a sector characterized by both thematic convergence and differentiated communicative strategies. Unlike prior studies that focus on single dimensions or isolated cases, this study integrates a four-layer coherence model—performance, operational, narrative, and strategic coherence—to offer a comprehensive explanation of how sustainability meaning is constructed in global hospitality. By applying this model, the analysis shows that hotel corporations construct sustainability discourse through a combination of measurable achievements, identity-driven storytelling, and governance-linked commitments. Substantive communication dominates the corpus, representing approximately 68% of all coded instances, confirming a broad shift toward evidence-based ESG reporting driven by stakeholder expectations for transparency and verifiability.

Yet symbolic discourse remains central, particularly in articulating organizational values, purpose, and social identity. Rather than functioning as greenwashing, symbolic statements serve to contextualize and legitimize substantive achievements within broader narratives of care, community stewardship, and responsible business. The comparison across hotel groups further shows that discursive coherence is not uniformly distributed: performance coherence is strongest in large multinational chains with established sustainability infrastructures, while narrative coherence is universally robust, underscoring the hospitality sector’s communicative dependence on brand identity and relational meaning.

Taken together, these findings illustrate that corporate sustainability communication in hospitality reflects a hybrid symbolic-substantive model that normalizes sustainability as both an operational imperative and a moral expectation. The results contribute empirical clarity to ongoing debates regarding authenticity, legitimacy, and the communicative construction of corporate responsibility, offering a nuanced account of how sustainability narratives evolve within a globalized, highly visible service industry.

6.1. Theoretical Implications

The study advances theoretical debates in corporate sustainability communication, legitimacy theory, and organizational discourse in several important ways.

First, it demonstrates empirically that discursive coherence operates as a multidimensional construct, requiring alignment across narrative, strategic, operational, and performance layers. This represents a novel conceptual contribution. The finding extends current conceptualizations of authenticity by showing that no single layer is sufficient to establish credible sustainability communication; authenticity emerges only through the interaction and reinforcement of multiple discursive dimensions.

Second, the results refine symbolic-substantive theory by illustrating that symbolic discourse does not inherently undermine credibility. Instead, when embedded within coherent performance and operational structures, symbolic elements contribute to the moral and cognitive legitimacy of corporate claims, functioning as interpretive anchors for stakeholders.

Third, the study contributes to sector-level discourse analysis by identifying shared sustainability frames—particularly food waste, disaster relief, and responsible business governance—that shape the communicative landscape of global hospitality. These shared frames suggest that the sector has developed a semi-institutionalized ESG lexicon that stabilizes meaning and reduces uncertainty for stakeholders.

Finally, the study offers a methodological contribution through the integration of AI-assisted coding with interpretive discourse analysis demonstrating how large, multi-document corpora can be systematically analyzed while preserving conceptual depth and qualitative nuance.

6.2. Managerial Implications

The findings offer several practical insights for sustainability and communications managers in global hospitality. First, organizations should prioritize strengthening performance and operational coherence, as these dimensions most directly influence perceptions of credibility. Investments in digital monitoring systems, third-party verification, and transparent disclosure can significantly enhance stakeholder trust.

Second, managers should recognize the strategic value of narrative coherence. Consistent identity framing—linking sustainability to corporate culture, organizational values, and long-term purpose—reinforces internal alignment and external legitimacy. However, narrative statements must be balanced with measurable evidence to avoid perceptions of symbolic overreach. From a green marketing perspective, sustainability narratives increasingly function as brand positioning tools, shaping how organizations differentiate themselves and signal responsibility to consumers. Ensuring alignment between communicated claims and operational performance is therefore critical to maintaining marketing credibility and avoiding perceptions of greenwashing.

Third, the sector-level analysis highlights clear best practices in environmental management, supply-chain responsibility, and community engagement. Companies can leverage these shared patterns to benchmark progress, align with industry norms, and participate in collective sustainability initiatives. Such alignment can also strengthen stakeholder perceptions by signaling conformity with legitimate industry standards, thereby reinforcing trust among investors, regulators, and civil society actors.

Fourth, the prominence of inclusion- and empowerment-related themes indicates that social sustainability communication is becoming increasingly important. Companies should continue developing supplier-diversity programs, youth employment initiatives, and financial-support mechanisms that integrate social value into corporate purpose. These initiatives contribute not only to social impact but also to stakeholder perceptions of authenticity, particularly among employees, local communities, and socially conscious consumers.

Finally, managers should view sustainability communication as an integrated governance function rather than a purely promotional activity. Strengthening board oversight, enhancing transparency, and institutionalizing ESG reporting processes will support both external legitimacy and internal accountability. By approaching sustainability communication strategically rather than instrumentally, organizations can enhance long-term stakeholder confidence and support more credible green marketing practices.

6.3. Limitations

Despite its methodological rigor, this study presents several limitations. First, the analysis focuses exclusively on publicly available corporate documents, which represent curated organizational self-presentations. Such materials cannot reveal internal decision-making dynamics, organizational tensions, or potential discrepancies between reported and enacted practices. Second, while qualitative content analysis provides deep insight into discursive structures, it cannot fully capture stakeholder interpretations or the real-world impact of communicated commitments. Third, the dataset reflects a specific time period; ESG reporting evolves annually, and future disclosures may alter the observed patterns. Finally, although the coding process was rigorous and triangulated, qualitative interpretation inevitably entails subjectivity, particularly when analyzing symbolic expressions.

6.4. Future Research Directions

Future scholarship should complement document-based analysis with interviews, ethnographic data, or participatory methods to explore how sustainability narratives are produced internally and interpreted by employees, guests, investors, and communities. Comparative research across different cultural or regulatory contexts could reveal how national environments shape symbolic and substantive communication. Longitudinal studies would help trace the evolution of discursive coherence over time, particularly as global ESG standards become more stringent. Additionally, integrating computational linguistics with qualitative discourse analysis could provide more granular insights into stylistic, emotional, or rhetorical patterns within sustainability communication. Finally, research might examine how business models—asset-light, franchising, management platforms—shape the discursive architecture of sustainability, potentially revealing new structural determinants of organizational authenticity.