The framework of the proposed FSTML is shown in

Figure 1. The model uses the Transformer decoder structure of GPT-2 [

31], retaining the position encoding (PE) layer, multi-head attention (MHA) layer, and feedforward neural network (FFN) in the pre-trained model. Considering that the above three layers contain most of the generalized knowledge learned by the pre-trained large language model, which already includes the ability to learn load data, FSTML chooses to freeze the multi-head attention layer, position encoding layer, and feedforward neural network layer and only allows the residual connection and layer normalization of the Transformer decoder to participate in model training. The network layers marked with “snow” in the figure represent the frozen parameter layers of the pre-trained large language model, while the layers marked with “spark” are the model fine-tuning layers involved in training. Referring to the One-Fits-All model [

27], the framework adopts the frozen pre-trained large language model architecture as a whole, and the corresponding fine-tuning layers are specially designed for the characteristics of load data. The methodological framework consists of three parts: (1) the Frequency-domain Global Learning Module (FGLM), (2) the Temporal-Dimension Learning Module (TDLM), and (3) the Spatial-Dimension Learning Module (SDLM).

3.1. Frequency-Domain Global Learning Module

Normalizing the load data before inputting the model is crucial to improving the model’s prediction performance. Assume that the input multivariate load data is

; the calculation formula for the instance normalization operation is expressed as follows:

where

and

are the mean and variance of the calculated input instances, respectively.

is a very small constant to prevent numerical instability caused by insufficient variance.

In order to prevent the excessive and redundant information of the load data from affecting the model’s prediction performance and to improve the prediction efficiency of the model, this module further uses a patching [

32] operation on the load data after normalization. Specifically, each input (

) is first divided into blocks by sliding, which can be overlapping or non-overlapping, as determined by the sliding step size (

s). Assuming

P represents the length of each block and

N is the number of blocks, the block sequence (

) can be obtained. Given the input sequence length (

L), block length (

P), sliding-window step size (

s), the number of blocks is

. It should be noted that the chunking operation requires padding of the end of the input sequence with

s repetitions of the last value (

). By using chunking, the number of input sequence units can be reduced from

L to approximately

. This means that the memory usage and computational complexity of the attention graph can be reduced by about

times. Therefore, under the constraints of training time and GPU memory, the chunking design can reduce the number of model parameters while retaining the global and local semantic information of the load data, providing a more optimized input structure for the Transformer multi-head attention layer of the pre-trained large language model.

In addition, after obtaining the block representation of the input load data, a simple linear mapping network is used to embed each block to enhance the representation ability of the input data to adapt to the structure of the pre-trained large language model network.

To address the challenge of LLM-based methods often failing to perform well in forecasting load data with a high degree of non-stationarity, we attempt to capture the frequency-domain features hidden within the load data. We attribute the shortcomings in capturing the pattern of load data to the failure of LLMs to fully learn the global features of the load data. In order to capture the global knowledge of load data, the first fine-tuning layer used in FSTML is a frequency-domain global fine-tuning layer (FGFL). This layer converts the load data from the time domain to the frequency domain so that the model can capture the frequency components of the load data, thereby understanding the global characteristics of the data, such as periodicity and trend changes, and generating corresponding embedded representations. First, the time-domain information in each block is converted to the frequency domain using Fast Fourier Transform (FFT). In time-series analysis, Fourier transform is used to identify periodic components in data. Fourier transform decomposes a complex signal into the sum of multiple simple periodic signals. The calculation formula for the Fourier transform of a continuous time signal (

) is expressed as follows:

where

is the complex spectrum of the signal at frequency

f and

j is an imaginary unit. This formula provides a mapping from the time domain to the frequency domain. In time-series analysis, Fourier transform is particularly suitable for analyzing and processing periodic data, such as sales data with obvious seasonal changes or temperature data with obvious day and night changes. By analyzing the frequency spectrum, the main periodic components and their intensities can be clearly identified, which helps to build a more accurate forecasting model.

Since the load data discussed in this work is discrete, discrete Fourier transform (DFT) is used to obtain the frequency-domain representation (

) of the original sequence (

X). The calculation formula is expressed as follows:

where

is the

kth frequency component in the obtained frequency-domain representation (

) and

j represents an imaginary unit. In practice, the module uses Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) with lower time complexity to more efficiently implement the conversion process from the time domain to the frequency domain.

Next, a linear layer is used to project the obtained frequency-domain representation; then, Inverse Fast Fourier Transform (IFFT) is applied to complete the inverse transformation from the frequency domain to the time domain. This process can be expressed as follows:

where

is the weight matrix of the projection layer. It should be noted that the reason why

uses a double dimension is that the output result after Fourier transformation of the input sequence is in complex form. For each real input point, there is a corresponding complex point (a real part and an imaginary part) in the frequency domain. Therefore, the dimension of the data in the corresponding frequency-domain representation will double, so a corresponding double dimension is used. Afterwards, in order to adapt to the input of the downstream Transformer multi-head attention layer, the output (

) of the inverse fast Fourier transform is further embedded through the linear embedding layer to obtain the final input pre-trained large language model’s global information prompt (

where

D refers to the data input dimension required by the pre-trained multi-head attention layer). After obtaining the global prompt (

), in order to allow the model to adaptively determine the contribution of global information to load prediction, a selective gating mechanism is used to adaptively suppress the global cue to maximize the prediction performance.

3.2. Temporal- and Spatial-Dimension Learning Module

In order to ensure that the model can accurately capture the periodic pattern of a specific dataset, we propose a time-dimension learning module to fine tune the pre-trained large language model. This module mainly consists of two parts: the select gate and the Frequency-domain Temporal Fine-tuning Layer (FTFL). The frequency-domain time-dimension fine-tuning layer uses a complex multi-layer perceptron network to learn the temporal pattern from the frequency-domain representation of the time dimension and outputs the feature representation. The function of the selection gate is to determine the contribution of the feature representation to the model’s prediction.

The frequency-domain time-dimension fine-tuning layer is the core part of the time-dimension learning module, which is specifically used to capture the time dependency of time series. Converting time-series data from the time domain to the frequency domain can effectively capture the global time dependency. The frequency representation can reveal the periodicity and trend characteristics of the time series, which may not be so obvious in the time domain. The fine-tuning layer operates in the frequency domain and uses a multi-layer perceptron (MLP) to learn long-term and short-term patterns in load data in an efficient way. First, the input sequence is converted to a complex form in the frequency domain through a fast Fourier transform, and a sequence consisting of a real part and a sequence consisting of an imaginary part are obtained. Together, these two sequences reveal the periodic amplitude, phase, and other information of the original data, which helps the model learn the complex periodic pattern of the sequence. Afterwards, a complex multilayer perceptron network is specially designed for this complex data. The network analyzes and learns the real and imaginary parts of the frequency representation, then combines the results. The single-layer structure of the frequency-domain complex multilayer perceptron network is shown in

Figure 2. Assume that the complex input of the

th layer of the multilayer perceptron is

; the output of layer

l can be calculated as follows:

where

and

represent the real and imaginary parts of a complex number, respectively;

is the sigmoid activation function;

and

represent the imaginary and real learning weights of the

lth layer network, respectively;

and

indicate the corresponding imaginary bias and real bias, respectively; and

j is the plural symbol. This module can fully learn time-dimension characteristics such as the periodicity and trend of frequency components while maintaining the complex properties. The MLP architecture is highly configurable, allowing us to effectively balance model capacity and the risk of overfitting by adjusting the number of neurons or hidden layers based on the complexity of the problem and the scale of the data. Its forward propagation process is easily parallelizable, ensuring fast training and inference speeds.

After

L layers of the frequency-domain complex multilayer perceptron network, the final output (

) is input to the selection gate. The selection-gate mechanism mainly adaptively selects the feature representation of each fine-tuning-layer output, thereby determining the impact of the fine-tuning layer on the model’s prediction, aiming to optimize the model’s adaptability and performance for different datasets. Specifically, the selection gate dynamically adjusts the activation state or weight of the adapter to achieve flexible adaptation to different datasets. The selection gate uses a learnable scaling sigmoid function as a gating mechanism, and the calculation formula is expressed as follows:

where

is the scaling factor, which affects the steepness of the sigmoid function, thereby determining the sensitivity of the selected gate. In order to intuitively understand the working mechanism of the selection gate, the selection curves corresponding to different scaling factors are visualized in

Figure 3. The advantage of using a gating mechanism is that by selecting the scaling factor (

), the model can adaptively adjust the contributions of different features based on the learned frequency-domain characteristics of load data, thereby achieving more accurate predictions.

During the training phase, the model will adaptively adjust parameters to determine the contributions of all feature representations in to the model’s prediction. At the same time, the setting of the scaling factor () affects the response sensitivity of the selection gate. A larger value makes the gating function more sensitive, thereby achieving fine tuning of the adapter activation state. In general, the introduction of the selection-gate mechanism effectively achieves precise fine tuning of different datasets without significantly increasing the complexity of the model, further improving the generalization ability of the model. Afterwards, the output of the frequency-domain multilayer perceptron will be converted back to the time domain.

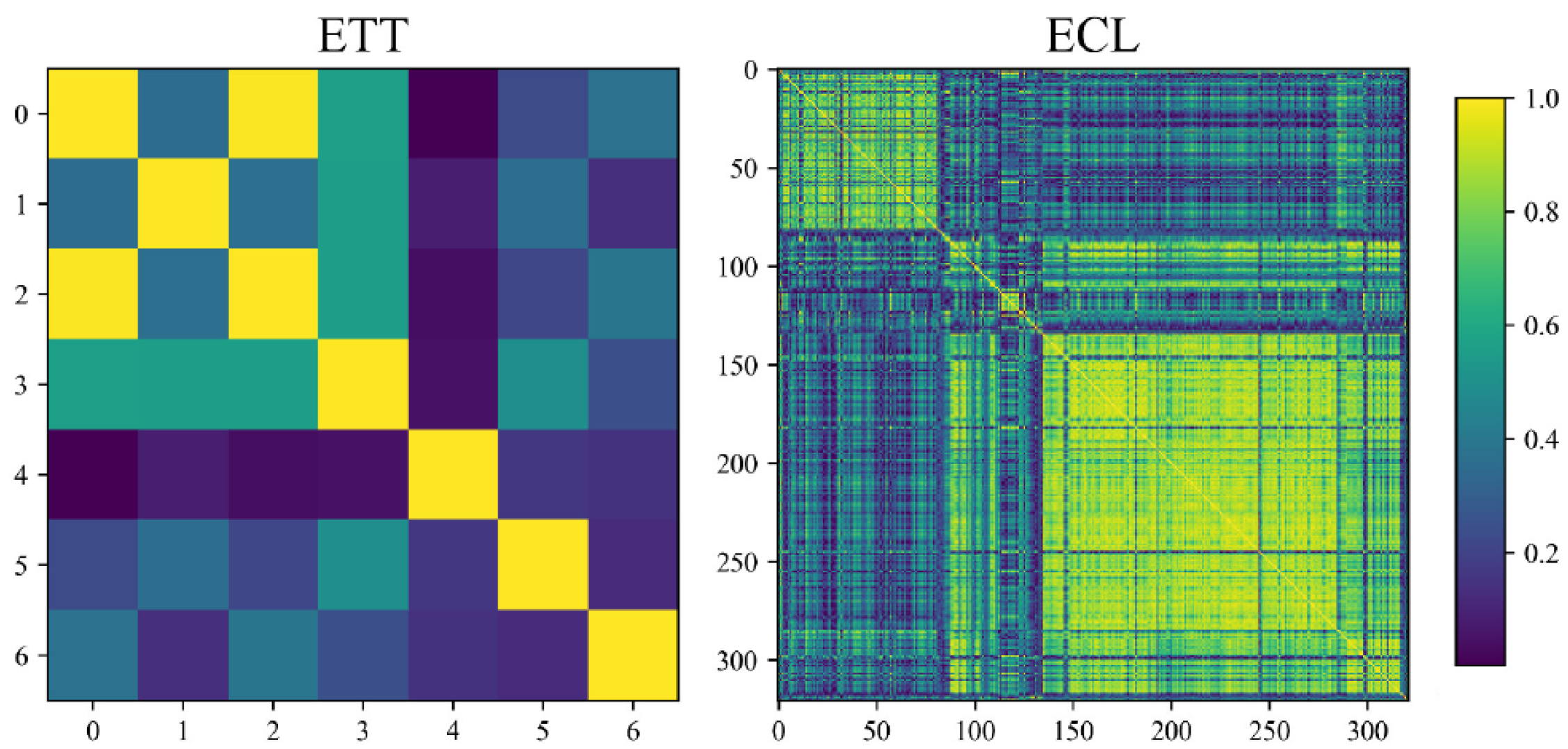

The spatial-dimension learning module is designed to capture cross-sequence dependencies in load data. In multivariate load forecasting, there may be complex interactions between different series, and these interactions are crucial for accurately predicting future values. Traditional load forecasting methods often have limitations in capturing such cross-sequence dependencies, especially when the relationships between the sequences are nonlinear and dynamically changing. The spatial-dimension learning module is designed to overcome these limitations and improve the accuracy of predictions by learning the dependencies between sequences by processing data in the frequency domain.

The structure of the spatial-dimension learning module is consistent with that of the temporal-dimension learning module, and a similar frequency-domain spatial-dimension fine-tuning layer (FSFL) is used to extract relevant features between different variable sequences from the frequency domain. The difference is that the frequency-domain spatial-dimension fine-tuning layer operates along the variable dimension, so the output of the upstream module needs to be reshaped by channel before being input into the spatial-dimension learning module. A selection gate is also used to adaptively select the feature representation of the output of the spatial-dimension fine-tuning layer.

3.3. Load Forecasting Method Based on Frequency-Domain Spatial–Temporal Mixture Learning

The model is designed as an end-to-end structure, which mainly converts the input historical load data into a frequency-domain representation through the frequency-domain transformation module, effectively capturing periodic and non-periodic information. The model adopts the pre-trained large language model structure and inserts a fine-tuning layer specially designed for load data into it. After completing the pre-processing of the input load data, global learning in the frequency domain is first performed to obtain the global frequency-domain feature representation of the load data. After that, two fine-tuning layers are used to extract the time-dimension features and spatial-dimension features of the sequence so as to learn the spatial–temporal pattern of the load data. In addition, the residual connection and layer normalization modules from the pre-trained large language model are retained in the model to enhance the training stability of the network and accelerate convergence.

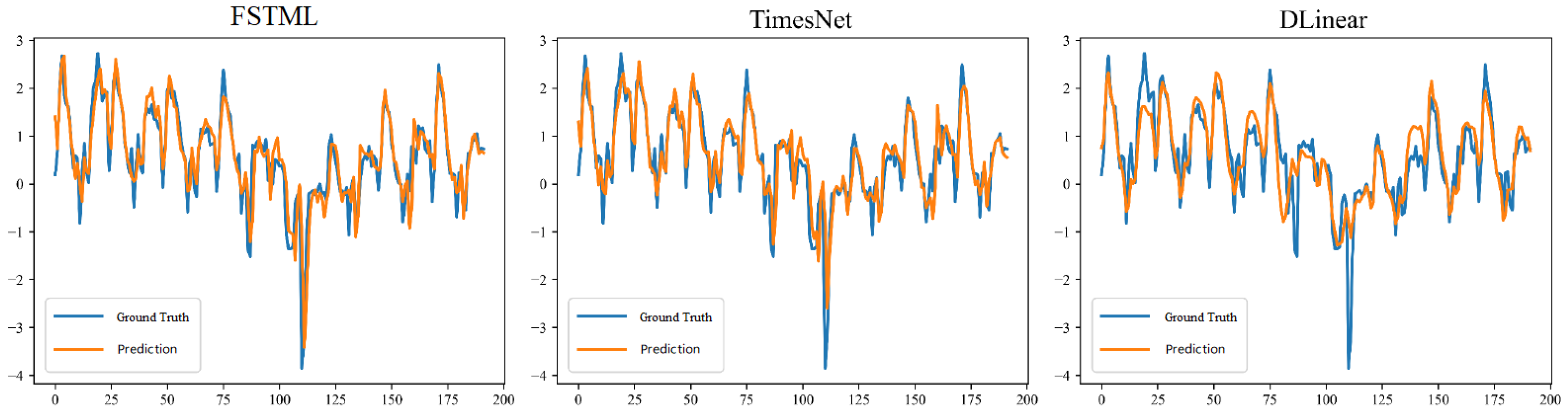

In forecasting process, the data is first preprocessed, which includes two key steps: data cleaning (handling missing values, outliers, etc.) and data normalization (scaling the data to a consistent range). Then, the preprocessed data is fed into the proposed FSTML model. This model takes the input historical data as input, captures periodic patterns and global dependencies in the frequency domain through the frequency-domain global learning module, and extracts local spatial correlations and temporal dynamics through the temporal- and spatial-dimension learning module. Through these two modules, the model learns the latent features of the historical load sequence and generates the final forecasting results.

The loss function of the model uses the mean squared error (MSE) to calculate the error between the predicted sequence and the true sequence. The calculation formula is expressed as follows:

where

is the value of the real sequence and

is the value predicted by the model.